Abstract

Background:

Child abuse pediatricians (CAPs) are often consulted for injuries when child physical abuse is suspected or when the etiology of a serious injury is unclear. CAPs carefully evaluate the reported mechanism of the child’s injury and the medical findings in the context of the child’s family and social setting to identify possible risk and protective factors for child abuse and the need for social services. It is unknown what population risk indicators along with other social cues CAPs record in the social history of the consultation notes when assessing families who are being evaluated for child physical abuse.

Participants and setting:

Thirty-two CAPs representing 28 US child abuse programs.

Methods:

Participants submitted 730 completed cases of inpatient medical consultation notes for three injury types: traumatic brain injury, long bone fracture, and skull fracture in hospitalized children 4 years of age and younger. We defined a priori 12 social cues using known population risk indicators (e.g., single mother) and identified de novo 13 negative (e.g., legal engagement) and ten positive social cues (e.g., competent parenting). Using content analysis, we systematically coded the social history for the social cues.

Results:

We coded 3,543 cues resulting in a median of 7 coded cues per case. One quarter of the cues were population indicators while half of the cues were negative and one quarter positive.

Conclusions:

CAPs choose a wide variety of information, not always related to known population risk indicators, to include in their social histories.

Keywords: Child abuse pediatricians, Child physical abuse, Qualitative analysis, Risk and protective factors, Consultation notes

1. Introduction

Child abuse and neglect is a serious public health problem resulting in both short and long term health impairments and in some cases, death (Corso, Edwards, Fang, & Mercy, 2008; US Department of Health & Human Services, 2018; Felitti et al., 1998; Putnam-Hornstein, 2011; Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, 2012). Whereas early research on child maltreatment concentrated on the individual (either the perpetrator or the child victim), (Kempe, Silverman, Steele, Droegemueller, & Silver, 2013) research conducted over the last three decades shows that multiple risk factors within the child’s environment or social ecology relate to the type, severity and chronicity of abuse that may occur and protective factors may negate or buffer a child from the effects of child abuse (Saul et al., 2014; Stith et al., 2009; Swenson & Chaffin, 2006).

Findings for risk and protective factors are derived from different types of studies which provide distinct levels of evidence. Prospective population-based studies, which provide the strongest evidence for risk factors with the outcome of abuse, have found that the following population risk indicators precede the occurrence of child abuse and neglect: children with special health care needs and children of young age; single mother, re-ordered family and the occurrence of intimate partner violence; isolation, poverty, and unemployment; caretaker psychiatric diagnosis, caretaker substance abuse, young maternal age, and maternal low educational achievement (Kotch, Browne, Dufort, Winsor, & Catellier, 1999; Sidebotham, Heron, & Team, 2006; Spencer et al., 2005). Findings from cross-sectional or retrospective studies are more numerous and provide less robust evidence compared to population-based studies. Although cross-sectional and retrospective studies provide correlation or association with child abuse and neglect, they do not provide evidence on the cause and effect of abuse or other variables that may mediate the cause and effect. Risk factors associated with abuse include a caretaker’s history of child abuse, negative caretaker perceptions of their child, caretaker affect or behavioral problems including substance abuse, caretaker cognitive and affective deficits, housing instability, non-biological caregiver in the home, chaotic or volatile family situations (Douglas & Mohn, 2014; Duffy, Hughes, Asnes, & Leventhal, 2015; Lindberg, Beaty, Juarez-Colunga, Wood, & Runyan, 2015; Miyamoto et al., 2017; Wathen & MacMillan, 2013; Young et al., 2018). Protective factors that increase family strengths and reduce the likelihood of child abuse and neglect include supportive social networks, stable family relationships, nurturing parenting skills, parental employment and adequate housing (Kumpfer & Magalhães, 2018; Saul et al., 2014; Schofield, Lee, & Merrick, 2013; Stith et al., 2009; Swenson & Chaffin, 2006). Although prospective and other studies provide important associations and epidemiological patterns, the studies do not usually include contextual information on the child and parent and family and their larger social ecologies.

Contextual information on the child and family is available in child abuse pediatrician (CAPs) notes. CAPs are consulted for injuries when child physical abuse is suspected or when the etiology of a serious injury is unclear. A recent study showed that over 4000 children are admitted to US hospitals each year for serious physical abuse (Leventhal, Martin, & Gaither, 2012). CAPs critically evaluate the pattern of injury in the context of the reported injury mechanism. During the exam, the CAP elicits elements of the child and families’ social ecology to identify social risk and protective factors as well as unmet social needs. (Christian et al., 2015; Mian, Schryer, Spafford, Joosten, & Lingard, 2009). This information is contained within the social history of the consultation note and may contribute to the CAP’s opinion on the likelihood of abuse based on the comprehensive evaluation.

Thus, the complete CAP consultation note provides contextual information regarding a child and family’s social ecology absent from the literature. The consultation note is shared with other medical personnel as well as others outside of the medical field, including investigative and legal agencies or personnel involved in the case, all of whom have differing information needs, training and understanding of child abuse (Dubowitz, Christian, Hymel, & Kellogg, 2014; Mian et al., 2009). Whereas prospective studies have identified compelling evidence for population risk indicators for child abuse, it is unknown to what extent CAP consultation notes in cases of suspected child physical abuse reflect these social risk factors. Although recent studies have used consensus processes to define key consultation elements for the medical evaluation of child abuse (Burrell, Moffatt, Toy, Nielsen-Parker, & Anderst, 2016; Campbell, Olson, & Keenan, 2015) there is still debate among CAPs regarding what elements of a child and families’ social ecology to include in the social history (Burrell et al., 2016; Campbell et al., 2015; Mian et al., 2009). The goal of this study was to qualitatively examine and describe the types of risk and protective factors recorded by CAPs as part of their comprehensive evaluation of children injured by physical abuse.

2. Methods

2.1. Study context

As part of a larger mixed-method study of risk perception in the medical evaluation of child physical abuse, we collected 730 cases of three types of injuries (traumatic brain injury, long bone fracture, and skull fracture) in hospitalized children 4 years of age and younger referred for CAP evaluation. Cases were solicited from 32 child abuse pediatricians representing 28 child abuse pediatrics programs in the US. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah and by each Institutional Review Board of the participating physicians.

2.2. Participants

Study participants were 32 CAPs who were recruited from two professional physician child maltreatment groups: the Ray E. Helfer Society and the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Child Abuse and Neglect. The participants were primarily female (84%), Non-Hispanic White (81%) and had ten or more years of experience as a CAP (62%). Participants were recruited through notices posted to the listserv of each group. In order to be eligible to participate, CAPs were required to have five years of post-residency practice, be board certified in pediatrics, spend at least 50% of their clinical time evaluating possible child abuse cases including physical abuse, and be at an institution with an Institutional Review Board. To ensure a diverse physician group, minority physicians were over-recruited through snowball sampling as well as the listservs of the professional groups.

2.3. Study design

Participants were asked to cut and paste de-identified completed evaluations of their patients into a web-based interface. Cases were selected by having participants enter information about patients seen on randomly selected days from the previous 6 months. The web-based interface asked participants to enter their evaluation in the order of a standard medical history including the presenting illness, past medical history, review of systems, family history, social history and physical exam. Participants were able to place their entire de-identified evaluation into the web-based system as a single document if they did not use a standard pattern for their evaluations.

2.4. Analysis

Elements of the social history from the consultation notes describing the families’ social ecology were systematically coded as social cues using directed qualitative content analysis. Directed content analysis is a research method used to describe a phenomenon that is incomplete or would benefit from further description and involves using a priori and de novo coding of textual data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Stemler, 2001). The a priori coding for social cues was operationally defined using 12 known population risk indicators identified in prospective cohort studies (Kotch et al., 1995; Sidebotham et al., 2006; Spencer et al., 2005). The risk indicators were grouped into four categories-Family (e.g., single mother), Social (e.g., isolation), Child (e.g., disabled child), and Parental (e.g., young maternal age). Two investigators (initials) independently reviewed a random sample of consultation notes to confirm coding for the population-based risk indicators and to identify additional de novo positive and negative social cues that described the child and family’s social ecology. From this review, the two investigators discussed their coding and developed a codebook that included the name of the code, definition, and example text. Each social cue was coded to only one category. To ensure coding consistency, the first 100 of the 730 cases were coded by the two investigators independently using the codebook and compared for consistency (Richards, 2014). The remaining cases were all coded by one investigator (LMO) and 10% of the cases were randomly selected and reviewed by a second investigator (HTK) to prevent coding drift. Throughout this process, disagreement was resolved through discussion that prompted a review of prior cases and categories to ensure that both investigators agreed to the application of a definitions in all cases.

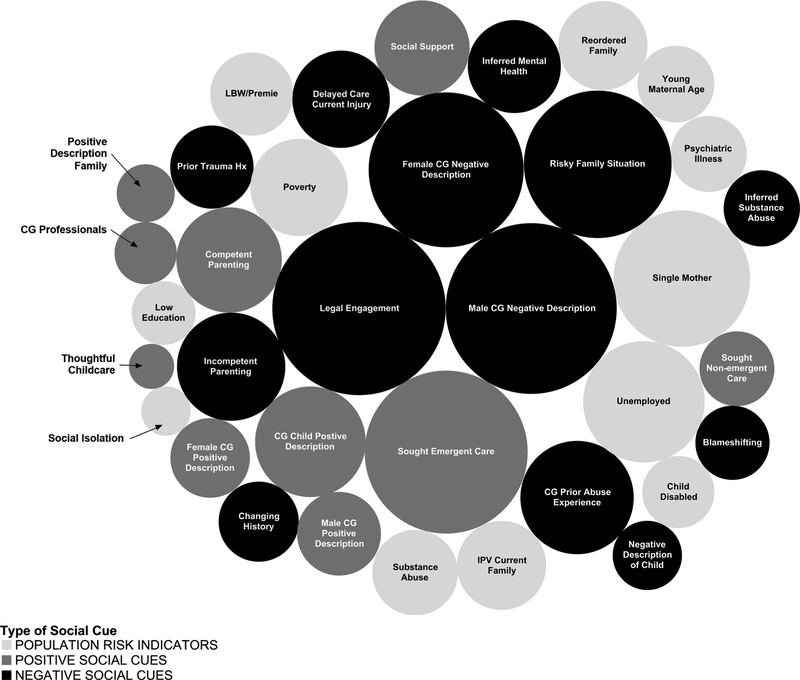

Bubble charts were created to compare the number of coding references for the social cues. A bubble chart is a variation of a scatter plot in which data points are replaced with bubbles and an additional dimension of data is represented in the size of the bubbles (Yau, 2012). NVivo 9 software (QSR International [Americas] Inc., Cambridge MA) was used to facilitate data management, Tableau 8 (Tableau Software [Americas] Inc., Seattle WA) was used to create bubble charts and figures and Microsoft Excel was used for describing the number of coded references.

3. Results

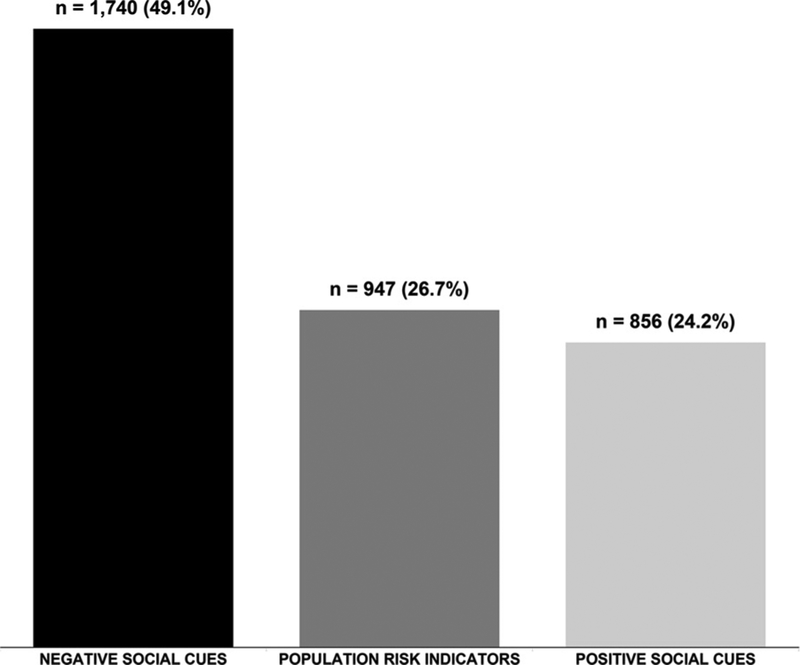

We identified 10 positive and 13 negative de novo social cues from the text of the consultations. In combination with the 12 a priori population risk indicators, this provided a total of 35 social cues. See Appendices A and B for definitions. Using the definitions in Appendices A and B, we coded 3543 social cues from the 730 child abuse cases resulting in a median of 7 coded cues per case (IQR 5,10) with a range of 1–40 coded cues. Fig. 1 shows that almost half of the social cues recorded by CAPs were negative cues (49%), followed by population risk indicators (27%) and positive social cues (24%). Combining the population risk indicators cues (which we considered to be negative social cues) with the negative social cues shows that CAPs recorded three negative social cues for every positive social cue.

Fig. 1.

Social Cues by Type (N = 3543 coding references).

Fig. 2 is a bubble chart comparing how often the CAPs recorded individual social cues. In the figure, each bubble represents an individual social cue and has an area proportional to the number of times the code was recorded by the CAP. In addition, each bubble is labeled with the individual social cue and colored to reflect the type of cue it represents: negative, population risk indicator or positive. The five most recorded cues — legal engagement (n = 295), negative description of the male caregiver (n = 287), sought emergent care (n = 261), negative description of female caregiver (n=236), risky family situation (n=214) — accounted for almost 40% of all written cues and none of the cues are population-based risk indicators. The first time that population risk indicators emerge is in next largest set of five cues which includes the population risk factors of single mother (n = 183) and unemployed (n=145) as well two negative social cues of caregiver prior abuse experience (n = 126) and incompetent parenting (n = 115) and one positive social cue of caregiver’s positive description of the child (n = 120). These 10 cues combined account for over half (56%) of all recorded cues. The remaining 25 cues comprise over 40% of the written cues with the five least recorded cues — low education of mother (n = 40), caregivers are professional (n = 38), positive description of family (n = 33), social isolation (n = 24), and appropriate child care provided (n = 20), representing both population risk indicators and positive cues.

Fig. 2.

Individual Social Cues-Sized by Number (N = 3543 coding references).

Table 1 provides examples of written cues from the CAPs consultation notes for the three most frequently recorded cues by negative, population risk indicator and positive (negative description of male and female caregivers was combined in the table under the negative social cues).

Table 1.

Examples of written cues from CAPs consultation notes for the three most frequently recorded cues by type of cue (Negative, Population Risk Indicator and Positive).

| Type of Social Cue | Examples from Child Abuse Pediatrician Consult Notes |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Negative Social Cue Legal Engagement |

|

| Negative Social Cue Negative Description of Male or Female Caregiver |

|

| Negative Social Cue Risky Family |

|

| Population Risk Indicator Single Mother |

|

| Population Risk Indicator Unemployed |

|

| Population Risk Indicator Poverty |

|

| Positive Social Cue Sought Emergent Care |

|

| Positive Social Cue Care Giver Positive Description of Child |

|

| Competent Parenting |

|

For negative social cues, Table 1 shows that legal engagement included descriptions from prior CPS involvement for the family including unsubstantiated or closed CPS cases to the mother or father’s current or remote past arrest, probation and incarcerations. he written cues for negative description of male or female caregivers varied from caretaker flat affect, possibility of alcohol or drug use or paternity issues and the cues for Risky Family depicted a wide range of living situations that provided details regarding dangerous or chaotic living situations for the child. The other nine negative social cues (data not shown) included descriptions of possible abuse experience at different ages for the caregiver including very young age and living in foster care; incompetent parenting including late or inconsistent bedtimes, no parental supervision; and, implied caretaker substance abuse or mental health issues.

For population risk indicators, category single mother included description of persons living with the mother to the level of involvement of the father and Unemployed focused on current and or looking for employment for both mother and father. Written cues for Poverty often included the words WIC, TANF, food stamps, Medicaid.

Among positive social cues, sought emergent care was the only positive social cue among the top five recorded cues. These written cues described ways that parents sought immediate care for the current injury as well as information related to timing of injury and who was caring for the child. Caregiver Positive Description of Child noted the patients’ pleasant or pleasing temperament often including the words happy and easy going. Written descriptions for Competent Parenting included the responsibilities and activities involved with raising a child from finding a babysitter to taking care of a child’s illness.

4. Discussion

We analyzed consultation notes to qualitatively explore the information about the family’s social ecology that practicing CAPs record when assessing a child for possible physical abuse. We coded over 3000 written social cues demonstrating that CAPS do record a rich social history in their consultation notes that encompass many domains of the child and families’ social ecology. We were interested in the extent that CAPs recorded known population risk indicators when assessing families who were being evaluated for abuse. Half of the written cues were negative social cues; only one quarter of the written social cues were population risk indicators. These findings show that CAPs choose a wide variety of information, not always related to known population risk indicators, to include in their consultation notes.

The CAP’s negative impression of the male and female caregivers combined were the most frequently recorded negative cues. This may be a reflection of the social ecological framework which posits that family is usually the most proximal to the child (Belsky, 1993). CAPs recorded their subjective impressions of whether caregiver reactions to interviews were appropriate, impressions of caregivers’ affect or personality, suggestions of alcohol and drug abuse, and past unconventional work history. Some of the cues included very remote caregiver social histories especially in regard to legal engagement. For example, we found cues related to a caregiver’s history of probation or arrest as a teenager. In a similar vein, unsubstantiated or closed CPS cases were also commonly recorded. The remote historical information conveys an impression of the caregiver’s social ecology that may introduce bias while not reflecting on the child’s current social ecology.

Many negative cues aligned with established child abuse risk factors (Dakil, Sakai, Lin, & Flores, 2011; Duffy et al., 2015; Gjelsvik, Dumont, Nunn, & Rosen, 2014). It is critical to recall, however, that while risk factors increase the likelihood of child abuse, the risk factors are not a direct cause of abuse. Population-based studies of child abuse risk, such as the one by Sidebotham et al. (2006), remind us that while children living in homes struggling with poverty, mental illness, criminal activity or other adverse situations have a significantly increased risk for abuse, a majority of children living with adverse situations will not experience abuse.

We recognize that CAPs may record negative cues without intending to bias a diagnostic evaluation of suspected abuse. CAPS often document social adversities to guide referrals and resources. It should be noted that some of the negative cues could reflect clear needs for families that can help providers target high risk families to reduce the occurrence of child abuse (Giardino, Hanson, Hill, & Leventhal, 2011). For example, CAP references to a caregiver’s expressions of depression may prompt referral for psychological services; information related to inappropriate developmental expectations of the child may prompt referrals to parenting classes or a home visiting nurse; and, information about escalating family violence may require legal intervention to protect the child and/or caregiver (Leventhal, 2000). Paralleling this, CAPs recorded positive cues that documented family strengths including decisions about seeking prompt medical care for the injured child and thoughtful choices about child care, potentially highlighting family strengths to be considered in light of abuse or injury to the child.

Regardless of the intention of the CAP, the wording for the negative and positive cues projected an unpleasant impression of the caregiver or the living situation for the negative cues and a more favorable feeling for the positive cues. For example, the subjective descriptions for “incompetent parenting” may reflect caregivers that are unwilling or unable to care for their child in sharp contrast to “competent parenting” that conveys a family composed of diligent and loving caregivers. How these impressions subsequently contribute to diagnostic decisions related to abuse, to the provision of social services, or to the first impressions of investigative and legal personnel is unclear.

The CAP consultation note, including the social history, is an important part of a complex medical evaluation of a child and their family referred for suspected abuse (Dubowitz, 2011). We found that the wording used by CAPs in their consultation notes varied from open-ended descriptions of families and living situations to very structured assessments that used pre-specified categories of concern. The relative effectiveness of these distinct formats for either medical decision making or communication with community agencies is unknown. However, because the consultation note is a foundational document for multiple agencies involved in the investigation of child abuse cases, concerns that subjective information found in the notes may bias outside readers is reasonable (Dubowitz, 2011). Defining needed elements and standardized documentation in the medical evaluation may provide a framework for the development of evaluation tools to make consultation notes more uniform and less subjective. Recent studies have examined different models of child abuse consultations (Keenan & Campbell, 2015), consensus processes to define key consultation elements for the medical evaluation of child abuse (Burrell et al., 2016; Campbell et al., 2015) and the use of structured information in combination with a peer review process (Lorenz et al., 2018). Recent findings suggest that structured information in cases of suspected child abuse without the social history promotes high agreement in diagnosis (Lorenz et al., 2018) while the addition or modification of social history to a CAP consultation note is capable of changing diagnosis in cases with medical uncertainty (Keenan, Cook, Olson, Bardsley, & Campbell, 2017). It is increasingly clear that the social history included in a CAP consultation can influence medical diagnostic decisions regarding abuse. Further research is warranted to understand how the social history in a CAP consultation note is interpreted by child welfare and law enforcement colleagues involved in the multidisciplinary response to suspected child abuse.

Our study has several limitations. First, although we had consultation notes from a diverse group of CAPs, the sampling of physicians was not random. We recruited from two professional organizations and accepted all interested participants who met the inclusion criteria. While this may have led to some bias, our sample of 32 individual CAPs working at 28 centers is likely broadly representative of academic child abuse pediatrics. Second, the density of social cues varied among the consultation notes and there is the possibility of coding variability. Two research team members conducted the content analysis using agreed upon operational definitions, and we rechecked 10% of the sample, but it is still possible that there was coding drift over time. Third, the child abuse consultation notes are usually written after the CAP has determined their final diagnosis. It is possible that CAPs may include cues selectively to attempt to influence non-medical investigators including CPS and law enforcement. If the CAP feels that abuse did not occur, it is possible that more positive than negative cues are written in the social history. Conversely if a CAP determined that abuse did occur, more negative cues may be included in the social history. Finally, we a priori coded population risk factors as they provide the strongest evidence that the risk preceded the abuse and grouped other positive and negative cues found in the consultation notes. We did not a priori code risks from associational studies, although these studies do contribute evidence to the social context of abuse. These risks were captured in the de novo coding and contribute to the context of the families.

The social history is used to explore the child and families’ social ecology for potential risk factors for abuse, to help understand family dynamics and to make recommendations to both medical and non-medical providers for any needed continuing medical, social and mental health services (Christian et al., 2015; Kellogg, 2005; Mian et al., 2009). We found that CAPs do record detailed social histories as part of their consultation notes that describe the child and families’ social ecology including population risk indicators. The consultation notes we analyzed contained more negative social cues compared to population risk indicators or positive cues for physical abuse. In addition, we found that the notes also contained subjective information that may or may not be necessary for the final evaluation, possibly reflecting the biases of the CAP (Croskerry, 2013) and affecting the interpretation of the findings by outside agencies. While a uniform reporting style and structured checklists show promise in decreasing bias, continued research is warranted to understand how child abuse pediatricians’ approach and document their findings in cases of suspected child abuse.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Child Health and Development [grant 1RO1HD061373].

aa

Appendix A. Definitions for population risk indicators social cues (N = 12 Cues)

| Variable Name | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Child Risk Factors | ||

| Low Birth Weight/Preemie | Requiring hospital stay for infants born less than 36 weeks gestation | “Birth weight was approximately 3 pounds.” |

| Disabled or Behavioral Disorder | Any disabling condition. Includes learning disabilities, speech, hearing or neuro-developmental disability as well as increased medical care for a certain point in the patient’s life. Can include baby born with cleft palate or with hemophilia. | “His diagnoses include Trisomy 13, refractory seizure disorder, infantile spasms, Diabetes Insipidus, hx cleft lip & palate.” |

| Family Risk Factors | ||

| Single Mother | Mother unmarried. Only use if mother is described as single or not married or partnered (See Literature-reordered family if mother is living with boyfriend or step father or married to step father of current patient) | “patient resides with biological mother, half-sister and cousin” |

| Re-Ordered Family | Mother is unmarried and is living with father surrogates including step-father or unrelated male in household-mother with male who is not the biological father. | “Lives with mother and mother’s boyfriend” |

| Intimate Partner Violence-Current Family | Interpersonal violence in current household. | “Mother stated that child’s father was very violent with her, trying to strangle her at least on one occasion” |

| Parental Risk Factors | ||

| Young Maternal Age | < 20 years at child’s birth | “The baby’s mother, XXQ7)” |

| Substance Abuse | Includes current or past historv of documented or known alcohol or other drug abuse (does not include descriptions of possible substance abuse-see Social Cues inferred substance abuse) | “Mother is presently in counseling as related to illicit drug use.” |

| Psychiatric Illness | Includes diagnosed or currently reported illness for biological mother and father. Look for medications listed or diagnosis or the caretaker has the problem now (does not include descriptions such as mother looks depressed or if illness such as PTSD was treated in past and resolved-see Social Cues inferred mental health) | “Father was treated for schizophrenia in past but is not being treated now” |

| Low Educational Achievement | < H.S. diploma or GED for mother | “The baby’s mother quit school in the 11th grade.” |

| Social Risk Factors | ||

| Poverty Unemployment | Any indicator of poverty (includes living situation) Any indicator of unemployment (does not include mother as homemaker) | “Receives cash assistance and food stamps” “Mother and father both presently unemployed” |

| Social Isolation | Indicators of little or no social support | “No family lives nearby” |

Appendix B. Definitions for positive and negative social cues (N = 23 positive and negative social cues)

| Variable Name | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Social Cues | ||

| Caregivers are Professionals | Professional position (white collar profession) or academic situation (beyond high school) is reported. | “Mom graduated from college in 2008 and has been taking classes to be PT.” |

| Caregivers Positive Description of Patient | Caregiver’s positive description of child that the injured child was easy to care for or has a positive temperament. | “She reports him to be a smiling and happy child.” |

| Competent Parenting | Positive indication or impression of parenting abilities. | “Father said when mother arrived at his home 2 hours later, he discussed the events with her and they both reassessed the Patient’s scalp, noting no concerns.” |

| Positive Description of Family | Gives indication that this is a nice family who are aware of one another-goes beyond competent parenting to description of family gets along or was in a good emotional state preceding and during the time the injury occurred. | “The family got ready for church and went to church. No problems occurred at church. When they got home the mother took the patient’s decorative head band off and as she did so she felt a large soft spot on the right side of the head” |

| Positive Description of Female Caregiver | Positive description of the mother, stepmother, or girlfriend, or other female caregiver. | “Mom appeared appropriately concerned and protective throughout my interview with her.” |

| Positive Description of Male Caregiver | Positive description of the father, stepfather, boyfriend, or other male caregiver. | “During the interview, dad was very attentive to him, holding him in his arms.” |

| Social Support Available | Caregivers report physical or emotional comfort from family, friends or community. | “The investigators found the extended family, the parents, the extended family and community to be very cooperative and supportive.” |

| Sought Emergent Care for Current Injury | Caregiver calls or takes child immediately to medical care (ED or pediatrician office); calls 911; for current injury. | “Mom immediately brought BC to an urgent care facility, where he was directed to go to the Outside Hospital.” |

| Sought Non-Emergent Care | Caregivers called pediatrician office or other medical office/facility to care for a non-emergent medical problem in the past. | “Mom discussed it with her PCP, who told her it was likely ‘growing pains’.” |

| Thoughtful Childcare Provided | Family has thought about the needs of their child and reports having suitable childcare. | “The parents have arranged schedules so that they do not need child care, with the mother only working when the father is not working.” |

| Negative Social Cues | ||

| Blameshifting | Caregiver blames others for child’s injury. | “At about 7 p.m. mother called father to state that the baby had a skull fracture and rib fractures, and that these were caused by her two year old son.” |

| Caregiver Delayed Care for Currei Injuries | Caregiver does not immediately or in a timely manner it contact health care facility or private doctor or other medical agency such as EMS for care of injury. | “On the morning of the day of admission the parents called the ER and were instructed to bring the baby in. The baby came in 12 hours later.” |

| Caregiver’s Negative Description of Child | Caregiver’s description describes a bad or unpleasant quality, characteristic or aspect of patient. | “The mother explained that you cannot take anything away from him or he “flips out.” |

| Changing History | Caregiver provides different explanations for same injury. | “After transfer of the patient to The Children’s Hospital, the story changed to the patient was jumping on the bed and fell off, hitting her elbow on the wooden footboard” |

| Caregiver Prior Abuse Experience | Caregiver’s childhood experience with abuse or CPS is indicated or any history of past intimate partner abuse for current caregivers but not current family (see Legal Engagement). | “Both parents had a history of CPS involvement with their families when they were children.” |

| Incompetent Parenting | Negative indication or impression of parenting abilities. | “When asked directly, female caregiver stated that she has allowed Patient and his toddler brother to be alone and unsupervised on other occasions in the bathtub for short periods of time while she (female caregiver) is in other areas of the home.” |

| Inferred Mental Health for Caregivers | Second hand report of mental health issues and illness has not been diagnosed (use psychiatric illness when illness is diagnosed and current). | “Both parents have a history of depression but are not on any medications.” |

| Inferred Substance Abuse for Caregivers | Second hand report of substance abuse issues and substance abuse is not treated or substantiated (use substance abuse when substance abuse is documented). | “Both parents use alcohol on a regular basis and father smokes marijuana as well.” |

| Legal Issues | Description of caregivers (including boyfriend) current or past experience with legal system from prior CPS involvement for current family to caregiver arrest, probation and incarceration. | “There have been several referrals to Children’s Services in regard to the patient and her fractures…” Or “mother recently released from jail for parole violation” |

| Negative Description of Female Caregiver | Description of negative aspects of mother, stepmother, or girlfriend, or other female caregiver. | “Mom has a history of not following up with medical plans following previous emergency department visits and hospitalizations.” |

| Negative Description of Male Caregiver | Description of negative aspects of father, stepfather, boyfriend, or other male caregiver. | “Dad was working a fork lift at dump but got suspended for cursing at manager (he was fired from another job in the past, “because of his attitude”) |

| Prior Trauma for Patient | Family or physician report that patient experienced a prior traumatic injury. | “During that time he had a chest x-ray done which revealed healing rib fractures as well as a healing clavicle fracture.” |

| Risky Family Situation | Indicate a family living situation or interpersonal relationships that involves danger or risk; an environment that is liable to cause hurt or harm to the patient from chaotic living situation to family that is severely impaired and non-adaptive. | “Mother stated that father called her at work on multiple occasions because he was angry about her seeing boyfriend. Mother stated that father’s behavior escalated throughout the day. On father’s last call to mother while she was at work, he stated that he was going to burn the house down with himself and child inside.” |

Footnotes

Partially presented at the National Meeting of the Safe States Alliance and SAVIR, June 2013, Baltimore, MD.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Note

Content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Belsky J (1993). Etiology of child maltreatment: A developmental ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3), 413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell T, Moffatt M, Toy S, Nielsen-Parker M, & Anderst J (2016). Preliminary development of a performance assessment tool for documentation of history taking in child physical abuse. Pediatric Emergency Care, 32(10), 675–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KA, Olson LM, & Keenan HT (2015). Critical elements in the medical evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics, 136(1), 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CW, Crawford-Jakubiak JE, Flaherty EG, Leventhal JM, Lukefahr JL, Sege RD, … Hurley TP. (2015). The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics, 135(5), e1337–e1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso PS, Edwards VJ, Fang X, & Mercy JA (2008). Health-related quality of life among adults who experienced maltreatment during childhood. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 1094–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croskerry P (2013). From mindless to mindful practice—Cognitive bias and clinical decision making. The New England Journal of Medicine, 368(26), 2445–2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakil SR, Sakai C, Lin H, & Flores G (2011). Recidivism in the child protection system: Identifying children at greatest risk of reabuse among those remaining in the home. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(11), 1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas EM, & Mohn BL (2014). Fatal and non-fatal child maltreatment in the US: An analysis of child, caregiver, and service utilization with the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data Set. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(1), 42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H (2011). Child abuse pediatrics: Research, policy and practice. Academic Pediatrics, 11(6), 439–441. 10.1016/j.acap.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Christian CW, Hymel K, & Kellogg ND (2014). Forensic medical evaluations of child maltreatment: A proposed research agenda. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(11), 1734–1746. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JY, Hughes M, Asnes AG, & Leventhal JM (2015). Child maltreatment and risk patterns among participants in a child abuse prevention program. Child Abuse & Neglect, 44, 184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardino AP, Hanson N, Hill KS, & Leventhal JM (2011). Child abuse pediatrics: New specialty, renewed mission. Pediatrics, 128(1), 156–159. 10.1542/peds.2011-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjelsvik A, Dumont DM, Nunn A, & Rosen DL (2014). Adverse childhood events: Incarceration of household members and health-related quality of life in adulthood. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(3), 1169–1182. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualtative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan HT, & Campbell KA (2015). Three models of child abuse consultations: A qualitative study of inpatient child abuse consultation notes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 43, 53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan HT, Cook L, Olson LM, Bardsley T, & Campbell KA (2017). Social intuition and social information physical child abuse evaluation and diagnosis. Pediatrics, 140(5), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg N (2005). American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child, Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics, 116(2), 506–512. 10.1542/peds.2005-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Droegemueller W, & Silver HK (2013). The battered-child syndrome In Krugman RD, & Korbin JE (Eds.). C. Henry Kempe: A 50 year legacy to the field of child abuse and neglect (pp. 23–38). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kotch JB, Browne DC, Dufort V, Winsor J, & Catellier D (1999). Predicting child maltreatment in the first 4 years of life from characteristics assessed in the neonatal period. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23(4), 305–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotch JB, Browne DC, Ringwalt CL, Stewart PW, Ruina E, Holt K, … Jung JW. (1995). Risk of child abuse or neglect in a cohort of low-income children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 19(9), 1115–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, & Magalhães C (2018). Strengthening families program: An evidence-based family intervention for parents of high-risk children and adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 27(3), 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal JM (2000). Thinking clearly about evaluations of suspected child abuse. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 5(1), 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal JM, Martin KD, & Gaither JR (2012). Using US data to estimate the incidence of serious physical abuse in children. Pediatrics, 129(3), 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg DM, Beaty B, Juarez-Colunga E, Wood JN, & Runyan DK (2015). Testing for abuse in children with sentinel injuries. Pediatrics, 136(5), 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz DJ, Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Berger RP, Bertocci G, Herman BE, … Zuckerbraun N. (2018). Classifying injuries in young children as abusive or accidental: reliability and accuracy of an expert panel approach. The Journal of Pediatrics, 198(July), 144–150.e4. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian M, Schryer CF, Spafford MM, Joosten J, & Lingard L (2009). Current practice in physical child abuse forensic reports: A preliminary exploration. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(10), 679–683. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Romano PS, Putnam-Hornstein E, Thurston H, Dharmar M, & Joseph JG (2017). Risk factors for fatal and non-fatal child maltreatment in families previously investigated by CPS: A case-control study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E (2011). Report of maltreatment as a risk factor for injury death: A prospective birth cohort study. Child Maltreatment, 16(3), 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L (2014). Handling qualitative data: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Saul J, Valle LA, Mercy JA, Turner S, Kaufmann R, & Popovic T (2014). CDC grand rounds: Creating a healthier future through prevention of child maltreatment. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(12), 260–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Lee RD, & Merrick MT (2013). Safe, stable, nurturing relationships as a moderator of intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(4), S32–S38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidebotham P, Heron J, & Team AS (2006). Child maltreatment in the “children of the nineties”: A cohort study of risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(5), 497–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer N, Devereux E, Wallace A, Sundrum R, Shenoy M, Bacchus C, … Logan S. (2005). Disabling conditions and registration for child abuse and neglect: A population-based study. Pediatrics, 116(3), 609–613. 10.1542/peds.2004-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemler S (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation: A peer reviewed electronic journal, 7(17), Retrieved from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=2017&n=2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Liu T, Davies LC, Boykin EL, Alder MC, Harris JM, … Dees JEMEG. (2009). Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(1), 13–29. 10.1016/j.avb.2006.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson CC, & Chaffin M (2006). Beyond psychotherapy: Treating abused children by changing their social ecology. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(2), 120–137. 10.1016/j.avb.2005.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services (2018). Administration on children, youth and families, children’s bureau. Child maltreatment 2016. Washington DC; Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment. [Google Scholar]

- Wathen CN, & MacMillan HL (2013). Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: Impacts and interventions. Paediatrics & Child Health, 18(8), 419–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Bentley T, & Johnson MS (2012). A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: New findings from a 30-year follow-up. American Journal of Public Health, 102(6), 1135–1144. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau N (2012). Visualize this!. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Young A, Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Lorenz DJ, Hickey S, Berger SP, … Thompson R. (2018). Are negative/unrealistic parent descriptors of infant attributes associated with physical abuse? Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]