Abstract

The immune-mediated central nervous system (CNS) demyelinating disorder multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common neurological disease in young adults. One important goal of MS research is to identify strategies that will preserve oligodendrocytes (OLs) in MS lesions. During active myelination and remyelination, OLs synthesize large quantities of membrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which may result in ER stress. During ER stress, pancreatic ER kinase (PERK) phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), which activates the integrated stress response (ISR), resulting in a stress-resistant state. Previous studies have shown that PERK activity is increased in OLs within the demyelinating lesions of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a model of MS. Moreover, our laboratory has shown that PERK protects OLs from the adverse effects of interferon-γ, a key mediator of the CNS inflammatory response. Here, we have examined the role of PERK signaling in OLs during development and in response to EAE. We generated OL-specific PERK knockout (OL-PERKko/ko) mice that exhibited a lower level of phosphorylated eIF2α in the CNS, indicating that the ISR is impaired in the OLs of these mice. Unexpectedly, OL-PERKko/ko mice develop normally and show no myelination defects. Nevertheless, EAE is exacerbated in these mice, which is correlated with increased OL loss, demyelination and axonal degeneration. These data indicate that although not needed for developmental myelination, PERK signaling provides protection to OLs against inflammatory demyelination and suggest that the ISR in OLs could be a valuable target for future MS therapeutics.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) (Kuerten and Lehmann 2011). Both MS and its animal model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) are characterized by oligodendrocyte (OL) death, demyelination, and axonal degeneration (Frohman et al., 2006; Trapp and Nave 2008). Although the cause and pathogenesis of MS are poorly understood, recent studies suggest that OL apoptosis can contribute significantly to the development of the disease (Barnett and Prineas 2004; Matute and Perez-Cerda 2005; Mc Guire et al., 2010). In addition, animal studies have shown that the protection of OLs from EAE-induced apoptosis results in the attenuation of demyelination and axonal degeneration in EAE lesions (Hisahara et al., 2000; Mc Guire et al., 2010). Taken together, these data support the concept that OL death can play a critical role in the demyelination present in MS and EAE (Matute and Perez-Cerda 2005; Mc Guire et al., 2010; Ozawa et al., 1994).

OLs synthesize large quantities of membrane proteins and myelin lipids (Pfeiffer et al., 1993), making them sensitive to disruptions of the secretory pathway during active periods of myelination or remyelination, which may trigger the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response (Lin and Popko 2009). Certain human leukodystrophies appear to result from the sensitivity of OLs to disruption of the secretory pathway (Fogli et al., 2004; Southwood et al., 2002). In response to ER stress, pancreatic ER kinase (PERK) phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), which activates the integrated stress response (ISR) (Harding et al., 1999; Harding et al., 2003), resulting in a global reduction of translation and the expression of stress-induced cytoprotective genes in an effort to restore ER homeostasis (Harding et al., 2002; Harding et al., 2000; Ron and Hampton 2004). Phosphorylated eIF2α results in increased translation of mRNA encoding activating transcription factor 4, which stimulates the expression of a number of genes including the transcription factor C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), which in turn induces the expression of growth arrest and DNA damage 34 (GADD34) expression (Harding et al., 2002). GADD34 participates in the dephosphorylation of eIF2α relieving its inhibitory effects on protein translation (Novoa et al., 2003). Nevertheless, cells in which ER stress is not adequately relieved undergo apoptosis, which is at least in part CHOP-dependent (Friedman 1996; Oyadomari et al., 2002; Oyadomari and Mori 2004).

Mice that ectopically express interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), a key mediator of the inflammatory response in EAE and MS, in the CNS and are heterozygous for a loss of function mutation in PERK demonstrate dramatically reduced survival, increased CNS hypomyelination, and enhanced OL loss (Lin et al., 2005). Moreover, PERK activity is increased during EAE, and the protective effects of IFN-γ on mature OLs and myelin during EAE induction are mediated via PERK activation, as PERK-haploinsufficient animals lost the protective effects of IFN-γ (Lin et al., 2007). Together, these data suggest an association of the ISR with the pathogenesis of MS and EAE (Lin and Popko 2009), but the cellular specificity of this response remains unclear.

In the current study, we investigated ISR signaling in OLs during development and in response to EAE. We generated OL-specific PERK-deficient (OL-PERKko/ko) mice, in which OL development and CNS myelination occurred normally, but which experienced an exacerbated EAE disease course, as reflected by increased OL loss, demyelination and axonal degeneration. Our findings indicate a role for the ISR in OL protection in EAE and point toward opportunities for developing therapeutic strategies for MS that are directed at ISR enhancement in these cells.

Materials and Methods

Generation of OL-PERKko/ko mice.

C57BL/6 mice carrying a floxed conditional allele of the Perk gene were previously described (Zhang et al., 2002). C57BL/6 mice that express the Cre recombinase under the transcriptional control of the 2’, 3’ cyclic nucleotide 3’ phosphodiesterase (Cnp) gene (Lappe-Siefke et al., 2003) were kindly provided by Dr. Klaus Nave’s group. Mice homozygous for the floxed Perk allele and heterozygous for the Cnp/Cre allele were bred and then mated to mice homozygous for the floxed Perk allele to generate litters containing both mice homozygous for the floxed Perk allele and heterozygous for the Cnp/Cre allele (OL-PERKko/ko), and control littermates that were homozygous for the floxed PERK allele but lacked the Cnp/Cre allele (PERKflox/flox). LoxP recombination was examined as previously described (Zhang et al., 2002). Briefly, genomic DNA isolated from the indicated tissues was used for genotyping: the PCR primers used were mPERK: 1229F 5’-CATCCCCATCAGCCTGTTTG-3’, mPERK: 568R1 5’-GTCTTACAAAAAGGAGGAAGGTGGAA-3’ and mPERK: 568F 5’-CACTCTGGCTTTCACTCCTCACAG-3’. All animals were housed under pathogen-free conditions and all animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Chicago (IACUC).

EAE immunization.

EAE was induced in the animals as previously described (Iglesias et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2006). Briefly, 6-week-old females received subcutaneous injections of 200 μg of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) 35–55 peptide (Genemed Synthesis Inc. TX) emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), supplemented with 600 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (strain H37Ra; BD Biosciences) in the flank and tail base. The mice also received two 400 ng intraperitoneal injections of pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories, Denver, CO) 24 h and 72 h later in 100 μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Clinical severity scores were recorded daily using a 0–5 point scale (0 = healthy, 1 = flaccid tail, 2 = ataxia and/or paresis of hind limbs, 3 = paralysis of hind limbs and/or paresis of forelimbs, 4 = tetraparalysis, and 5 = moribund or dead). To eliminate any diagnostic bias, mice were scored blindly.

Western blot analysis.

Tissues were removed, rinsed in ice-cold PBS, and then homogenized in cold lysis buffer using a motorized homogenizer as previously described (Lin et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2008). After incubation on ice for 15 min, the extracts were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm twice for 15 min each. Protein concentrations were determined by DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA); protein samples (40 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The blots were incubated with the following primary antibodies: anti-PERK (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF-2α, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-eIF2α (1:50, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-β-actin (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and myelin basic protein (MBP; 1:1000; Covance Emeryville, CA). The blots were then incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000, GE healthcare UK limited, UK) and the signal was revealed by chemiluminescence.

Immunohistochemistry.

Anesthetized mice were perfused through the left cardiac ventricle with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The tissues were removed, postfixed with paraformaldehyde, cryopreserved in 30% sucrose, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, and frozen on dry ice. Frozen sections were cut in a cryostat at a thickness of 10 μm. For immunohistochemistry, the sections were treated with −20°C acetone, blocked with PBS containing 5% goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated overnight with the primary antibody diluted in blocking solution. Antigen retrieval was used for PERK and CC1 double staining. Briefly, sections were boiled in 0.01 M tri-sodium citrate buffer, pH 6, for 10 min followed by cooling at room temperature for 20 min. Section were incubated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidases for 30 min, followed by preincubation with 5% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100 for 2 h at room temperature to block nonspecific binding, and incubated overnight with primary antibody diluted in blocking solution. Appropriate Fluorescein- or enzyme-labeled secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were used for detection. The immunohistochemical detection of PERK (1:50 Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), N-terminal of adenomatous polyposis coli (CC1; 1:50; Calbiochem), aspartoacylase (ASPA; 1:1000; kindly provided by Dr. MA Namboodiri), platelate-derived growth factor alpha (PDGFRα; 1:50; clone APA5, Millipore, Temecula, CA), MBP (1:1000; Covance Emeryville, CA), CD3 (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), CD11b (1:50; clone 5C6, Serotec) and phosphorylated neurofilament-H (SMI 31; 1:1000; Sternberger Monoclonals) was performed and analyzed as previously described (Lin et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2013; Madhavarao et al., 2004; Traka et al., 2010).

Real-time PCR.

Deeply anesthetized mice were perfused with ice-cold PBS. Total RNA from lumbar spinal cord was extracted using Aurum™ Total RNA Mini Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). SYBR Green real-time PCR was performed with iQ SYBER Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) on a Bio-Rad CFX96™ Real-Time PCR detection system as previously described (Lin et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2006).

Toluidine blue staining and electron microscopy analysis.

Mice were anesthetized and perfused with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The lumbar spinal cord tissues were processed, embedded, sectioned, and analyzed as previously described (Saadat et al., 2010). Toluidine blues-tained 1 μm-thick sections of the lumbar spinal cord were assessed for demyelination and the percentage of the demyelinated area was calculated by normalizing the area of demyelinated regions against the total white matter area by using by the NIH ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Electron microscopy (EM) images were used to calculate g-ratios using NIH ImageJ software as previously described. Briefly, five non-overlapping electron microscopy images at X5000 magnification were collected from three OL-PERKko/ko and three PERKflox/flox mice, and g-ratios were calculated for 150 axons per genotype. Images were collected using the Tecnai electron microscope at the University of Chicago Electron Microscope Facility.

Statistics.

The Student’s t-test was used for two-group comparisons. For multiple comparisons, a mixed-effects regression model was used, followed by a Bonferroni test using Stata 12.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Generation of OL-PERKko/ko mice.

The protein kinase PERK consists of an ER luminal stress sensor domain, an ER transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic eIF2α kinase domain. At the onset of ER stress, PERK is activated by autophosphorylation and then phosphorylates eIF2α (Harding et al., 1999). Phosphorylated eIF2α activates the ISR, which results in global reduction of translation and the expression of stress-induced cytoprotective genes in order to restore ER homeostasis in the stressed ER (Harding et al., 2003; Ron and Hampton 2004). Because Perk null mice die from pancreatic and liver insufficiency early in life (Harding et al., 2001), we exploited the Cre/loxP approach to examine the function of PERK specifically in oligodendrocytes (Pfrieger and Slezak 2012). To accomplish this we used mice (PERKflox/flox) carrying a floxed conditional allele of the Perk gene (Zhang et al., 2002) in combination with the Cnp/Cre mouse strain (Lappe-Siefke et al., 2003), which drives Cre recombinase expression in myelinating cells, to generate mice (OL-PERKko/ko) in which loxP recombination and the deletion of Perk from OLs occurs during development. LoxP recombination was clear in brain DNA of OL-PERKko/ko mice (Fig. 1A). Minor LoxP recombination was detected in tail, heart, and lung DNA from these animals, while no recombination was detected in thymus, spleen or kidney DNA of these mice (Fig. 1A). In addition, double immunolabeling analysis of 21-day-old mice showed that lower numbers of OLs (CC1 positive cells) in OL-PERKko/ko mice express PERK compared to PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 1B and C). Moreover, western blot analysis of total brain proteins of 21-day-old mice demonstrated reduced expression of PERK and phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) in the brains of OL-PERKko/ko mice when compared to control PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 1D), the significance of which was confirmed by quantitative analysis (Fig. 1E and F). These data are indicative of reduced PERK signaling in OLs of OL-PERKko/ko mice.

Figure 1. Generation of OL-PERKko/ko mice.

A. Genotyping PCR using genomic DNA of different tissues from OL-PERKko/ko mice, control (PERKflox/flox) mice and wild type mice showed strong LoxP recombination (900 base pair; bp) in the brains and weak LoxP recombination in the tails, hearts, and lungs, while no recombination was detected in thymuses, spleens and kidneys of OL-PERKko/ko mice. Both OL-PERKko/ko mice and PERKflox/flox mice, but not WT mice showed the floxed PERK allele (480 bp) in all the tissues examined. Only WT mice showed the WT allele (350 bp) in all tissues examined. N = 3 animals. B. Immunohistochemical analysis of 21-day-old mouse tissues using antibodies against PERK and CC1, a marker for mature OLs, showed lower numbers of PERK and CC1 double-positive cells in OL-PERKko/ko compared to PERKflox/flox. Scale bar 20 μm. C. Counts of PERK and CC1 positive cells showed lower numbers of double positive cells on OL-PERKko/ko compared to PERKflox/flox mice. N = 3 animals; graph indicates mean ± SD; # #P < 0.00002; **P < 0.0003. D. Western blot analysis of total brain protein extracts isolated from 21-day-old mice demonstrated reduced expression of PERK and p-eIF2α in the OL-PERKko/ko mice when compared to PERKflox/flox controls. E. and F. Quantitative analysis of western blot data showed that the ratio of PERK to β-actin (E) and the ratio of p-eIF2α to total eIF2α (F) were lower in OL-PERKko/ko mice when compared to PERKflox/flox mice. N = 3 animals; graph indicates mean ± SD; *P < 0.04. #P < 0.001. Abbreviations: SC-WM = spinal cord white matter; BS = brain stem.

Inactivation of Perk in OLs is not detrimental to OLs and myelin integrity.

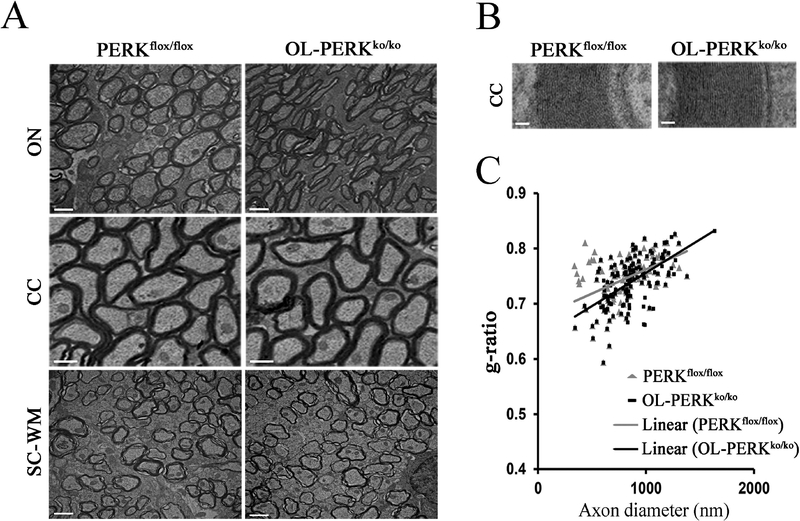

OL-PERKko/ko mice are phenotypically normal and fertile. No differences in OL or OL precursor cell numbers were observed in 21-day-old in OL-PERKko/ko mice as compared to PERKflox/flox mice. Cell numbers were assessed by immunohistochemistry using antibodies against ASPA, a marker for mature OL, and antibodies against PDGFRα, a marker for OL precursor cells (Fig. 2A and B). These data indicate that the deletion of Perk from OLs has no affect on the differentiation or survival of these cells. Furthermore, the expression of MBP was demonstrated to be normal in OL-PERKko/ko mice by both immunohistochemstry and western blot analysis of total brain proteins (Fig. 2C and D). Quantitative analysis of the western blots confirmed there was no significant difference in the ratio of MBP to β-actin between OL-PERKko/ko mice and PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 2E). Electron microscopy (EM) analysis of various regions of the brain and spinal cord of 21-day-old OL-PERKko/ko mice showed no myelin abnormalities in these mice (Fig. 3A and B). In addition, calculation of the mean g-ratio (axon diameter/fiber diameter) of the corpus callosum showed that axons in OL-PERKko/ko mice were myelinated normally in comparison to PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these data indicate that the deletion of Perk from OLs does not affect OL development or myelin synthesis. These mice therefore provide an excellent model for studying the effects of PERK inactivation in OLs during EAE.

Figure 2. Deletion of Perk in OLs had no effect on OL development or myelin synthesis.

A. Immunohistochemical analysis of 21-day-old mouse tissues using antibodies against ASPA, a marker for mature OLs, showed no differences in OL cell numbers between OL-PERKko/ko and PERKflox/flox mice. N = 3 animals; graph indicates mean ± SD. B. Counts of cells stained for PDGFRα, a marker for OL precursor cells (OPCs), showed no differences in OPC numbers between OL-PERKko/ko and PERKflox/flox mice. N = 3 animals; graph indicates mean ± SD. C. and D. Immunohistochemical staining of different CNS areas and western blot analysis of the total brain protein extracts from of 21-day-old mice demonstrated that the expression of myelin basic protein (MBP) is normal in OL-PERKko/ko mice. N = 3; scale bar: C, 20 μm. E. Quantitative analysis of western blot data showed no difference in the ratio of MBP to β-actin between OL-PERKko/ko mice and PERKflox/flox mice. N = 3 animals; graph indicates mean ± SD. Abbreviations: CC = corpus callosum; Cer = cerebellum.

Figure 3. Deletion of Perk in OLs had no effect on the myelin sheath.

A and B. EM analysis of various regions of the brain and spinal cord white matter of 21-day-old OL-PERKko/ko mice showed no myelin abnormalities. N = 3 animals; scale bar: A, 1 μm; B, 50 nm. C. The calculation of corpus callosum g-ratios showed no differences in myelin sheath thickness between OL-PERKko/ko mice and PERKflox/flox mice. N = 3 animals. Abbreviations: ON = optic nerve.

Deletion of Perk in OLs worsens the EAE disease course.

To study the OL-specific effects of the impairment of PERK-dependent signaling in the pathogenesis of EAE, one group of 6-week-old female OL-PERKko/ko mice were immunized with MOG35–55 peptide to induce EAE. A second group of immunized PERKflox/flox mice served as a control. All immunized mice developed a typical EAE clinical phenotype. Nevertheless, the onset was earlier in OL-PERKko/ko mice starting at around post immunization day (PID) 11, while PERKflox/flox mice showed symptoms of the disease beginning around PID14. Additionally, while PERKflox/flox mice followed a typical EAE disease course, reaching a mean maximal clinical score of 2.7, PERKko/ko mice displayed a higher clinical score that reached a mean maximum of 3.7 (Fig. 4A). In addition, we found that deletion of PERK in OLs suppressed the expression of mRNA of CHOP and GADD34 (Figure 4B and C), which are downstream targets of ISR signaling. These results indicate that PERK-dependent signaling is disrupted in OLs of OL-PERKko/ko mice, which has a significant impact on the onset and severity of EAE.

Figure 4. Impairment of the PERK-mediated ISR specifically in OLs exacerbated EAE disease severity.

A. Mean clinical scores were recorded daily from immunized PERKko/ko mice and PERKflox/flox mice: 0 = healthy, 1 = flaccid tail, 2 = ataxia and/or paresis of hindlimbs, 3 = paralysis of hindlimbs and/or paresis of forelimbs, 4 = tetraparalysis, 5 = moribund or death. N = 14 animals. Error bars represent SED, * P <0.05. B. and C. qPCR results showed that the deletion of Perk specifically in OLs suppressed the expression of CHOP and GADD34 in the lumbar spinal cord of the OL-PERKko/ko mice during EAE at PID17. All data presented as mean ± SD; N = 3 animals; *P <0.04, **P <0.02, ***P <0.004, #P <0.0002, ##P <0.0001.

OL-PERKko/ko mice experiencing EAE display an increased loss of OLs without a detectable effect on the inflammatory response.

To investigate the reason for the greater severity of EAE symptoms in immunized OL-PERKko/ko mice, histological analysis was performed on lumbar spinal cord white matter sections from these mice and compared to immunized PERKflox/flox controls; non-immunized mice of both genotypes were also included in the analyses. ASPA immunostaining showed that the number of OLs in the lumbar spinal cord white matter of immunized OL-PERKko/ko mice was low at the onset of clinical symptoms (PID11) and at the peak of disease (PID17) when compared to immunized PERKflox/flox mice or non-immunized mice of both genotypes (Fig. 5A and B). Immunized PERKflox/flox mice showed no difference in the number of OLs at PID11, but showed lower numbers of OLs at PID17 when compared to non-immunized mice of both genotypes (Fig. 5A and B). These data indicate that the deletion of Perk in OLs diminishes the survival of OLs during EAE.

Figure 5. Impairment of the PERK-mediated ISR specifically in OLs exacerbated EAE-induced OL loss without altering T cells infiltration and macrophase/microglia activation.

A. and B. ASPA immunostaining showed that the numbers of OLs were markedly decreased in the lumbar spinal cord white matter of OL-PERKko/ko mice at PID11 and 17. N = 3 animals; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.04, ***P < 0.03, #P < 0.02, ##P < 0.01. Scale bar: B, 20 μm. C and D. CD3 immunostaining showed that the deletion of Perk specifically in OLs did not affect T cell infiltration into the lumbar spinal cord white matter of the OL-PERKko/ko mice at PID11 or 17. N = 3 animals; scale bar: D, 20 μm. E. and F. CD11b immunostaining showed that the deletion of Perk specifically in OLs did not affect macrophages/microglia activation in the lumbar spinal cord white matter of the OL-PERKko/ko mice at PID11 or 17. N = 3 animals; scale bar: E, 20 μm. Abbreviations: No Im. = no immunization; LSC-WM = lumbar spinal cord white matter.

Autoreactive T cells are capable of entering the CNS and inducing EAE (Stromnes and Goverman 2006). We investigated whether the deletion of Perk in OLs disrupted the inflammatory response in the CNS during EAE. Lumbar spinal cord tissue from immunized and non-immunized OL-PERKko/ko and PERKflox/flox mice were fixed and stained for CD3, a T cell marker. We found no expression of CD3 in lumbar spinal cord white matter of non-immunized OL-PERKko/ko and PERKflox/flox mice. We also found that the deletion of Perk in OLs did not significantly alter the number of CD3-positive T cells in the lumbar spinal cord white matter of OL-PERKko/ko mice at the time of early onset of the disease (PID11) or at the peak of the disease (PID17; Fig. 5C and D) when compared to immunized PERKflox/flox mice. Similarly, the number of the CD11b-positive microglia/macrophages was not altered in the OL-PERKko/ko mice at PID11 or PID17 compared with PERKflox/flox mice (Figure 5E and F). Taken together, these observations indicate that the deletion of Perk specifically in OLs has no significant effect on T cell infiltration or microglia/macrophage activation in OL-PERKko/ko mice during EAE and that the increased loss of OLs in OL-PERKko/ko mice is unlikely due to an alteration in the immune response.

Impairment of the ISR in OLs exacerbates EAE-induced demyelination and axonal degeneration.

Multiple studies have shown that demyelination accompanies the loss of OLs in MS and EAE lesions (Dowling et al., 1997; Ozawa et al., 1994). To explore whether impairment of PERK signaling in OLs during EAE alters demyelination, we prepared lumbar spinal cords from immunized OL-PERKko/ko and PERKflox/flox mice at PID17, which is the peak of clinical disease, and examined them for tissue damage. Toluidine-blue staining revealed more severe myelin damage in the lumbar spinal cord of immunized OL-PERKko/ko mice compared to immunized PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 6A). In addition, immunized OL-PERKko/ko mice, but not immunized PERKflox/flox mice, showed demyelination in lateral and dorsal white matter regions of the lumbar spinal cord sections (Fig. 6A). Quantitative analysis of toluidine blue-stained sections showed that the percentage of white matter area in the lumbar spinal cord that was demyelinated in OL-PERKko/ko mice was significantly increased when compared to that of PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 6B). These data demonstrate that the impairment of the ISR in OLs increases the extent of demyelination in OL-PERKko/ko mice at the peak of EAE disease

Figure 6. Impairment of the PERK-mediated ISR specifically in OLs increased EAE-induced demyelination.

A. At PID17, imaging of the toluidine blue–stained sections revealed larger demyelinating lesions in the lumbar spinal cord white matter of OL-PERKko/ko mice as compared to PERKflox/flox mice (arrows). N = 3 animals; scale bar: 20 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of toluidine blue-stained sections showed that a higher percentage of the lumbar spinal cord white matter area was demyelinated in OL-PERKko/ko mice. N = 3 animals; graph indicates mean ± SD; *P < 0.05.

Axonal degeneration within spinal cord lesions of EAE animals has been well characterized (Herz et al., 2010). To determine if the disrupted ISR in OLs had a secondary effect on axonal degeneration we examined axonal integrity in the OL-PERKko/ko mice. Phosphorylated neurofilament-H (SMI31) immunostaining revealed more severe axonal loss in the lumbar spinal cord white matter of OL-PERKko/ko mice when compared to PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, EM analysis showed more severe axonal degeneration in the demyelinating lesions of the of OL-PERKko/ko mice compared to PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 7B). Quantitative EM analysis of the lumbar spinal cord sections showed a significant reduction in the total number of axons present within the demyelinationg lesions of the OL-PERKko/ko mice compared to PERKflox/flox mice (Fig. 7C). Moreover, the OL-PERKko/ko animals showed a significantly increased number of degenerating axons within the same areas (Fig. 7D). These data indicate that the increased loss of OLs in the OL-PERKko/ko mice results in increased axonal degeneration.

Figure 7. Impairment of the PERK-mediated ISR specifically in OLs increased EAE-induced axons degeneration.

A. At PID17, SMI31 immunostaining revealed reduced axonal density within the inflammation areas identified by the presence of CD3-positive T cells in the lumbar spinal cord white matter of the OL-PERKko/ko mice when compared to PERKflox/flox mice. N = 3 animals; scale bar: 20 μm. B. EM analysis showed that a subpopulation of myelinated axons present within the demyelinated areas of lumbar spinal cord white matter of both the OL-PERKko/ko and PERKflox/flox mice contained dark (electron-dense) axoplasmic material, a hallmark of axonal degeneration (stars and arrows). Scale bar: 2 μm. C and D. Quantitative EM analysis of lumbar spinal cord sections showed reduced total number of axons (C) and increased number of degenerating axons (D) within the demyelinating lesions of the ventral white matter in the lumbar spinal cord in the OL-PERKko/ko mice as compared to PERKflox/flox mice. N = 3 animals; graphs indicate means ± SD; #P <0.003; *P <0.03.

Discussion

OLs synthesize large amounts of membrane proteins and myelin lipids (Pfeiffer et al., 1993), making them sensitive to disruptions of the secretory pathway during active periods of myelination, such as development or myelin repair, which may trigger the ER stress response (Lin and Popko 2009). As a consequence of ER stress, PERK phosphorylates eIF2α, which activates the ISR (Harding et al., 1999; Harding et al., 2003), resulting in the global attenuation of protein biosynthesis and the expression of stress-induced cytoprotective genes in order to restore ER homeostasis (Ron and Hampton 2004). It has been shown that the disruption of protein translation in the secretory pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, neurodegenerative disorders, and hypomyelinating diseases (Araki et al., 2003; Bauer et al., 2002; Fogli et al., 2004; Leegwater et al., 2001; Lindholm et al., 2006; Southwood et al., 2002).

PERK has also been shown to play an important role in the normal development and function of a number of cell types, particular those responsible for synthesizing high levels of membrane or secreted proteins (i.e. cells with an active secretory pathway). For example PERK is required for the normal development and proliferation of the insulin secreting beta cells (Zhang et al., 2006) and if PERK is genetically ablated at the adult stage beta cell death and diabetes ensues (Gao et al., 2012). PERK signaling is critical in liver function by controlling the secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1, and its deficiency results in neonatal growth retardation (Li et al., 2003). PERK has been found to be critical for mammary gland development, regulating lipogensis and adipocyte differentiation (Bobrovnikova-Marjon et al., 2008). In addition, it has been shown that PERK is required for normal osteoblast proliferation and maturation during development, and PERK-deficient mice exhibit neonatal osteopenia, resulting in skeletal dysplasias (Wei et al., 2008). Therefore, we speculated that PERK might be required for the normal function of myelinating cells, considering the large demand on their secretory pathway.

To address the function of PERK in OLs, we used a conditional knockout mouse model, in which Perk was deleted in OLs. Unexpectedly, the OL-PERKko/ko mice are phenotypically normal and fertile. Moreover, we found that the deletion of Perk in OLs had no effect on OL development or myelin synthesis, although subtle effects on early stages of the myelination process cannot be ruled out. Surprisingly, these results demonstrate that the PERK signaling pathway does not play an essential role in OLs under normal physiological conditions, which is in contrast with other cell types with a high secretory pathway demand.

In contrast, we have previously shown that the PERK pathway is essential for OL survival during ER stress (Lin et al., 2005). We have also shown that mice that are haploinsufficient for PERK are not protected by IFN-γ during EAE (Lin et al., 2007). Nevertheless, these studies did not elucidate the specific contributions of PERK signaling in individual CNS cell types (OLs, astroctytes, microglia, and neurons) or blood-borne immune cell types (T cells and macrophages) to the development of EAE. OL loss and demyelination are hallmarks of MS and EAE lesions, and OL apoptosis in the absence of a clear immune response has been seen in the lesions of these diseases (Matute and Perez-Cerda 2005; Mc Guire et al., 2010). Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effects of PERK signaling impairment specifically in OLs during EAE.

Since the deletion of Perk in OLs has no effect on OL viability or myelin integrity, we used OL-PERKko/ko mice to assess the effects of the impairment of PERK signaling specifically in OLs during EAE pathogenesis. Although CNP/Cre mice, which are heterozygous for the CNP null mutation, exhibit neurological symptoms that correlate with a CNS inflammatory response, these characteristics are not present until the mice are approximately 19 months of age (Hagemeyer et al., 2012). Therefore, although we used the CNP/Cre mice to inactivate the conditional PERK allele in our model, this should not influence our results since we used the animals at six weeks of age. Using this unique mouse model, we found that OL-PERKko/ko mice displayed an earlier onset of the disease (PID11) and peaked at a higher clinical score than control mice. Interestingly, we also found that when the PERK-mediated ISR was impaired specifically in OLs, OL loss was greatly increased both during disease onset and at the peak of the disease, and demyelination was exacerbated at the peak of disease. Moreover, we did not find any evidence suggesting that the deletion of Perk in OLs significantly altered the degree of the T cell response or macrophages/microglia activation in the CNS of OL-PERKko/ko mice undergoing EAE. Collectively, these results provide direct evidence that the impairment of PERK signaling in OLs makes these cells more susceptible to inflammation, resulting in the exacerbation of demyelination in EAE. The inflammatory response, OL loss and demyelination are all thought to contribute, in both MS and EAE, to axonal degeneration, which has been proposed to be the cause of irreversible neurological disability in MS (Herz et al., 2010; Siffrin et al., 2010; Trapp and Nave 2008). In this study, we examined the effect of the impairment of the ISR in OLs on axonal degeneration during EAE. We found increased axonal loss within the demyelinating lesions in the OL-PERKko/ko mice, providing strong evidence that OLs normally contribute to axonal protection in the presence of CNS inflammation.

In summary, this study demonstrates that PERK signaling is not required by OLs during the active myelination process, despite the high secretory demand on these cells. In addition, our data provides direct evidence that the impairment of PERK signaling in OLs causes these cells to be more susceptible to inflammation, and subsequently results in increased OL loss, demyelination and axonal degeneration in EAE. These data strongly suggest a role for the ISR in protecting OLs against the harmful effects of CNS inflammation in EAE. These results are consistent with our recent study that has shown that enhancing PERK signaling in OLs protects these cells from apoptosis during EAE, maintaining myelin integrity and thereby protecting myelinated axons from degeneration (Lin et al., 2013). Interestingly, there is compelling evidence that components of the ISR are also activated in MS lesions, suggesting that our results are relevant to CNS inflammatory demyelination in humans as well (Cunnea et al., 2011; McMahon et al., 2012; Mhaille et al., 2008; Ni Fhlathartaigh et al., 2013). Collectively, our work suggests that enhancing PERK signaling in OLs might provide an effective therapeutic strategy for treating MS.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS34939), and the Myelin Repair Foundation to BP. We thank Dr. Klaus Nave for providing the CNP/Cre mice, Dr. M.A. Aryan Namboodiri for kindly providing the ASPA antisera, Gloria Wright for help with figure preparations, Dr. Maria Traka for critically reviewing the manuscript, and Dr. Hemamalini Bommiasamy and Karrar Eltayeb for help with immunizing the mice. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Araki E, Oyadomari S, Mori M. 2003. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and diabetes mellitus. Intern Med 42:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MH, Prineas JW. 2004. Relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis: pathology of the newly forming lesion. Ann Neurol 55:458–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J, Bradl M, Klein M, Leisser M, Deckwerth TL, Wekerle H, Lassmann H. 2002. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in PLP-overexpressing transgenic rats: gray matter oligodendrocytes are more vulnerable than white matter oligodendrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61:12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Hatzivassiliou G, Grigoriadou C, Romero M, Cavener DR, Thompson CB, Diehl JA. 2008. PERK-dependent regulation of lipogenesis during mouse mammary gland development and adipocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:16314–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnea P, Mhaille AN, McQuaid S, Farrell M, McMahon J, FitzGerald U. 2011. Expression profiles of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related molecules in demyelinating lesions and multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 17:808–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling P, Husar W, Menonna J, Donnenfeld H, Cook S, Sidhu M. 1997. Cell death and birth in multiple sclerosis brain. J Neurol Sci 149:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogli A, Schiffmann R, Bertini E, Ughetto S, Combes P, Eymard-Pierre E, Kaneski CR, Pineda M, Troncoso M, Uziel G and others 2004. The effect of genotype on the natural history of eIF2B-related leukodystrophies. Neurology 62:1509–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman AD. 1996. GADD153/CHOP, a DNA Damage-inducible Protein, Reduced CAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein Activities and Increased Apoptosis in 32D cl3 Myeloid Cells. Cancer Research 56:3250–3256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. 2006. Multiple sclerosis--the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med 354:942–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Sartori DJ, Li C, Yu Q-C, Kushner JA, Simon MC, Diehl JA. 2012. PERK Is Required in the Adult Pancreas and Is Essential for Maintenance of Glucose Homeostasis. Molecular and Cellular Biology 32:5129–5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemeyer N, Goebbels S, Papiol S, Kästner A, Hofer S, Begemann M, Gerwig UC, Boretius S, Wieser GL, Ronnenberg A and others 2012. A myelin gene causative of a catatonia-depression syndrome upon aging. EMBO Molecular Medicine 4:528–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Calfon M, Urano F, Novoa I, Ron D. 2002. Transcritional and translational control in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 18:575–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Jungries R, Chung P, Plesken H, Sabatini DD, Ron D. 2001. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol Cell 7:1153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Ron D. 2000. Perk Is Essential for Translational Regulation and Cell Survival during the Unfolded Protein Response. Molecular Cell 5:897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. 1999. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 397:271–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, Sadri N, Yun C, Popko B, Paules R and others 2003. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell 11:619–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz J, Zipp F, Siffrin V. 2010. Neurodegeneration in autoimmune CNS inflammation. Exp Neurol 225:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisahara S, Araki T, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Suzuki M, Abe K, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J, Momoi T, Saruta T and others 2000. Targeted expression of baculovirus p35 caspase inhibitor in oligodendrocytes protects mice against autoimmune-mediated demyelination. EMBO J 19:341–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias A, Bauer J, Litzenburger T, Schubart A, Linington C. 2001. T- and B-cell responses to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Glia 36:220–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerten S, Lehmann PV. 2011. The immune pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: lessons learned for multiple sclerosis? J Interferon Cytokine Res 31:907–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappe-Siefke C, Goebbels S, Gravel M, Nicksch E, Lee J, Braun PE, Griffiths IR, Nave K-A. 2003. Disruption of Cnp1 uncouples oligodendroglial functions in axonal support and myelination. Nat Genet 33:366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leegwater PA, Vermeulen G, Konst AA, Naidu S, Mulders J, Visser A, Kersbergen P, Mobach D, Fonds D, van Berkel CG and others 2001. Subunits of the translation initiation factor eIF2B are mutant in leukoencephalopathy with vanishing white matter. Nat Genet 29:383–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Iida K, O’Neil J, Zhang P, Li Sa, Frank A, Gabai A, Zambito F, Liang S-H, Rosen CJ and others 2003. PERK eIF2α Kinase Regulates Neonatal Growth by Controlling the Expression of Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Derived from the Liver. Endocrinology 144:3505–3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Bailey SL, Ho H, Harding HP, Ron D, Miller SD, Popko B. 2007. The integrated stress response prevents demyelination by protecting oligodendrocytes against immune-mediated damage. J Clin Invest 117:448–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Harding HP, Ron D, Popko B. 2005. Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates the response of myelinating oligodendrocytes to the immune cytokine interferon-γ. The Journal of Cell Biology 169:603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Kemper A, Dupree JL, Harding HP, Ron D, Popko B. 2006. Interferon-γ inhibits central nervous system remyelination through a process modulated by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Brain 129:1306–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Kunkler PE, Harding HP, Ron D, Kraig RP, Popko B. 2008. Enhanced integrated stress response promotes myelinating oligodendrocyte survival in response to interferon-gamma. Am J Pathol 173:1508–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Lin Y, Li J, Fenstermaker AG, Way SW, Clayton B, Jamison S, Harding HP, Ron D, Popko B. 2013. Oligodendrocyte-Specific Activation of PERK Signaling Protects Mice against Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci 33:5980–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Popko B. 2009. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disorders of myelinating cells. Nat Neurosci 12:379–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm D, Wootz H, Korhonen L. 2006. ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ 13:385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavarao CN, Moffett JR, Moore RA, Viola RE, Namboodiri MA, Jacobowitz DM. 2004. Immunohistochemical localization of aspartoacylase in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 472:318–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C, Perez-Cerda F. 2005. Multiple sclerosis: novel perspectives on newly forming lesions. Trends Neurosci 28:173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mc Guire C, Volckaert T, Wolke U, Sze M, de Rycke R, Waisman A, Prinz M, Beyaert R, Pasparakis M, van Loo G. 2010. Oligodendrocyte-specific FADD deletion protects mice from autoimmune-mediated demyelination. J Immunol 185:7646–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon JM, McQuaid S, Reynolds R, FitzGerald UF. 2012. Increased expression of ER stress- and hypoxia-associated molecules in grey matter lesions in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 18:1437–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhaille AN, McQuaid S, Windebank A, Cunnea P, McMahon J, Samali A, FitzGerald U. 2008. Increased expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related signaling pathway molecules in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 67:200–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Fhlathartaigh M, McMahon J, Reynolds R, Connolly D, Higgins E, Counihan T, Fitzgerald U. 2013. Calreticulin and other components of endoplasmic reticulum stress in rat and human inflammatory demyelination. Acta neuropathologica communications 1:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Jungreis R, Harding HP, Ron D. 2003. Stress-induced gene expression requires programmed recovery from translational repression. EMBO J 22:1180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S, Araki E, Mori M. 2002. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in pancreatic beta-cells. Apoptosis 7:335–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S, Mori M. 2004. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ 11:381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa K, Suchanek G, Breitschopf H, Bruck W, Budka H, Jellinger K, Lassmann H. 1994. Patterns of oligodendroglia pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain 117 ( Pt 6):1311–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer SE, Warrington AE, Bansal R. 1993. The oligodendrocyte and its many cellular processes. Trends Cell Biol 3:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfrieger FW, Slezak M. 2012. Genetic approaches to study glial cells in the rodent brain. Glia 60:681–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Hampton RY. 2004. Membrane biogenesis and the unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol 167:23–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadat L, Dupree JL, Kilkus J, Han X, Traka M, Proia RL, Dawson G, Popko B. 2010. Absence of oligodendroglial glucosylceramide synthesis does not result in CNS myelin abnormalities or alter the dysmyelinating phenotype of CGT-deficient mice. Glia 58:391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siffrin V, Vogt J, Radbruch H, Nitsch R, Zipp F. 2010. Multiple sclerosis - candidate mechanisms underlying CNS atrophy. Trends Neurosci 33:202–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwood CM, Garbern J, Jiang W, Gow A. 2002. The unfolded protein response modulates disease severity in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Neuron 36:585–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromnes IM, Goverman JM. 2006. Passive induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Nat Protoc 1:1952–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traka M, Arasi K, Avila RL, Podojil JR, Christakos A, Miller SD, Soliven B, Popko B. 2010. A genetic mouse model of adult-onset, pervasive central nervous system demyelination with robust remyelination. Brain 133:3017–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp BD, Nave KA. 2008. Multiple sclerosis: an immune or neurodegenerative disorder? Annu Rev Neurosci 31:247–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Sheng X, Feng D, McGrath B, Cavener DR. 2008. PERK is essential for neonatal skeletal development to regulate osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Physiol 217:693–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, McGrath B, Li Sa, Frank A, Zambito F, Reinert J, Gannon M, Ma K, McNaughton K, Cavener DR. 2002. The PERK Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2α Kinase Is Required for the Development of the Skeletal System, Postnatal Growth, and the Function and Viability of the Pancreas. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22:3864–3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Feng D, Li Y, Iida K, McGrath B, Cavener DR. 2006. PERK EIF2AK3 control of pancreatic β cell differentiation and proliferation is required for postnatal glucose homeostasis. Cell Metabolism 4:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]