Abstract

IMPORTANCE:

Advance care planning improves the receipt of medical care aligned with patients’ values; yet, it remains sub-optimal among diverse patient populations. To mitigate literacy, cultural, and language barriers to advance care planning, we created easy-to-read advance directives and a patient-directed, online advance care planning program called PREPARE in English and Spanish.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the efficacy of PREPARE plus an easy-to-read advance directive to an advance directive alone to increase advance care planning documentation and patient-reported engagement.

DESIGN:

Comparative efficacy randomized trial from February 2014 to November 2017.

SETTING:

Four San Francisco, safety-net, primary-care clinics.

PARTICIPANTS:

English- or Spanish-speaking primary care patients, age ≥55 years, with ≥2 chronic or serious illnesses.

INTERVENTIONS:

Participants were randomized to PREPARE plus an easy-to-read advance directive (PREPARE) or the advance directive alone. There were no clinician/system-level interventions. Staff were blinded for all follow-up measurements.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES:

The primary outcome was new advance care planning documentation (i.e., legal forms and/or documented discussions) at 15 months. Patient-reported outcomes included advance care planning engagement at baseline, 1 week, and 3, 6, and 12-months using validated surveys. We used intention-to-treat, mixed-effects logistic and linear regression, controlling for time, health literacy and baseline advance care planning, clustering by physician, and stratifying by language.

RESULTS:

The mean (SD) age of 986 participants was 63.3 years (± 6.4), 39.7% had limited health literacy, and 45% were Spanish-speaking. No participant characteristic differed between arms; retention was 85.9%. Compared to the advance directive alone, PREPARE resulted in higher advance care planning documentation (adjusted 43% vs. 32%; p<0.001) and higher self-reported increased advance care planning engagement scores (98.1% vs. 89.5%; p<0.001). Results remained significant among English and Spanish-speakers.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE:

The patient-facing PREPARE program and an easy-to-read advance directive, without clinician/system-level interventions, increased advance care planning documentation and patient-reported engagement, with statistically higher gains for PREPARE. These tools may mitigate literacy and language barriers to advance care planning, allow patients to begin planning on their own, and could substantially improve the process for diverse, English- and Spanish-speaking populations.

Clinicaltrials.gov: Per funders’ requests, this trial has 2 NCT numbers: NCT01990235, NCT02072941.

BACKGROUND

Advance care planning (ACP) improves the receipt of medical care aligned with patients’ values and patient satisfaction.1-3 Thus, ACP has recently been approved for reimbursement and recommended as a quality indicator in clinical guidelines.4-6 However, a majority of older adults, even those with serious illness, have not engaged in ACP conversations, and patients’ wishes are often not documented.4,7,8 ACP engagement remains especially low among minorities, patients with limited health literacy and English-proficiency, and is less than 20% among Latinos.9-14 For healthcare systems and clinicians, barriers to ACP include time and resource constraints. For minorities, ACP is complicated by a lack of trust and prior experiences of racism,15 complex legal language in advance directives (AD),16 and differing views on autonomy and decision making.17

To overcome these barriers and to address a lack of literacy-, culturally-, and linguistically-appropriate ACP materials, we created an easy-to-read AD and a patient-directed, interactive, online ACP program called PREPARE (www.prepareforyourcare.org) in English and Spanish.10,18 PREPARE is designed to be used at home, to prepare people for complex medical decision making,19 and incorporates several unique health communication elements. These include: application of user-centered design principles in the co-creation of the program with and for diverse patients and surrogate decision makers; five modular skill-building steps based on social cognitive and behavior change theories that model how to engage in ACP through video stories; narratives and testimonials based on real scenarios to mitigate cultural barriers; video, audio, and closed-captioning in two languages to mitigate literacy, language, and hearing barriers; and encouragement to include family and loved ones.18 The AD has been shown to improve ACP engagement among English- and Spanish-speakers,10 and PREPARE has been shown to improve engagement among English-speaking veterans.20 However, no prior study has compared these interventions among ethnically diverse, English and Spanish-speaking older adults in a safety-net healthcare system. The objective of this trial was to compare the efficacy of PREPARE plus the easy-to-read AD versus the AD alone on ACP documentation in the medical record and patient-reported ACP engagement. We hypothesized that documentation and engagement would increase in both arms and be greater in the PREPARE arm.

METHODS

This is a single-blind, parallel-group, comparative efficacy trial randomized at the patient level. Because of the benefits of ACP,1-3 we chose not to have a placebo group and provided all participants ACP materials. The conceptual framework of PREPARE, based on social cognitive and behavior change theories, and the trial protocol including inclusion/exclusion criteria; as well as the study flow diagram, recruitment procedures, sample size estimates, and validity, reliability, and response options of all outcome measures have been previously published and are included in the Protocol Supplement.18,21 This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board; written informed consent was obtained using a teach-to-goal process in English and Spanish;22 and safety was overseen by a Patient-Clinician Stakeholder Advisory Board and a Data Safety Monitoring Board. Although recruitment of English- and Spanish-speakers was supported by two funders, this was one trial with one protocol.21

Recruitment and Data Collection

Study participants were enrolled from four primary care clinics within the San Francisco Health Network, a public-health delivery system, from February 2014 - November 2017. We obtained a HIPAA waiver to identify individuals who met inclusion/exclusion criteria and had upcoming primary care appointments.21 After receiving clinician approval, we sent recruitment letters written at a 5th grade reading level in English or Spanish. If patients did not opt-out, staff called to assess interest and eligibility.

Participants and Enrollment Criteria

Patients were eligible if they were ≥55 years of age, spoke English or Spanish “well” or “very well,” had ≥2 chronic medical conditions by chart review, ≥2 visits with a primary care provider (i.e., established care), and ≥2 additional outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department visits in the past year (i.e., marker of illness). To standardize timing of the intervention to upcoming primary care visits, participants were enrolled 1-3 weeks prior to an upcoming appointment. Exclusion criteria included: dementia, moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment, blindness, deafness, delirium, psychosis, active drug or alcohol abuse (determined by their clinician, ICD-9 codes, chart review or in-person screening), lack of a phone or inability to answer consent teach-back questions within three attempts.21 Because ACP is a process,19,23 we did not exclude individuals who had previously engaged in ACP.

Randomization, Allocation Concealment, Blinding, Fidelity

Because limited health literacy is associated with lower ACP engagement,10,24 participants were block randomized, in random block sizes of 4, 6, and 8, by adequate versus limited health literacy using a random number generator.21 Clinicians were blinded. Participants could not be blinded but were told during consent there was a “50/50 chance” of getting one of two ACP interventions and the non-assigned intervention was not described. Research staff were blinded for all follow-up assessments. Staff followed standardized scripts, used checklists, and were observed for 10% of interviews to ensure protocol fidelity.21

Interventions

Online PREPARE Program Plus Advance Directive Intervention

In the PREPARE arm, participants were asked to review PREPARE in research offices. Although the 5-steps of PREPARE were designed to be viewed individually (approximately 10 minutes per step),18 to standardize exposure, participants were asked to complete all steps in their entirety. Although all materials are designed to be reviewed on their own at home, we standardized procedures for this trial by asking participants to review the materials on their own in our research offices. Research staff were available to answer questions but did not facilitate viewing. PREPARE includes interactive online values questions that, when answered, generate a unique action plan and “Summary of My Wishes.” This “Summary” was printed and given to participants. PREPARE participants were also asked to review the AD for 5 to 15 minutes. They were provided the AD, the PREPARE “Summary of My Wishes,” and website login to take home. Participants were called 1-3 days prior to their upcoming primary care visit and reminded to talk to their clinician about the PREPARE materials. No clinician or system-level interventions were included in either arm.21

Advance Directive Only Intervention

In the AD-only arm, participants were asked to review the easy-to-read advance directive (AD) in English or Spanish for 5 to 15 minutes in research offices on their own, were provided the AD to take home, and were reminded of their upcoming primary care visit by phone 1 to 3 days beforehand.21

Outcomes

We administered baseline questionnaires in person and follow-up questionnaires in person or by phone. Fluent English- or Spanish-speaking staff asked survey questions while participants could follow along with a written copy. Validity, reliability, and scoring of all measures are included in the published and online study protocol included in the Supplement.21 At baseline, we assessed self-reported participant characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, marital status, and education.21 We also administered validated measures of health literacy, US acculturation, education, finances, religion/spirituality, social support, presence of a possible surrogate decision maker, self-rated health and functional status, desired role in decision-making, prior planning (i.e., burial, wills), internet access in the home, and, for Spanish-speakers, patient-clinician language discordance.21 We determined documentation of ACP legal forms in the medical record at any time prior to enrollment and documented ACP discussions within 5 years of enrollment. In addition, the baseline ACP documentation rate in the 12-months prior to enrollment was determined using a composite of legal forms or documented ACP discussions.20,21

Primary Outcome

Our primary outcome was new ACP documentation in the medical record 15 months after enrollment. We used a composite variable of legal forms (i.e., ADs, Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare, and Physicians Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment) and documented discussions (i.e., oral directives or goals of care noted in the medical record) because both may be used to direct medical care.21 Documented discussions included documentation of oral directives by a physician or clinician notes describing patients’ surrogates or goals for medical care. All chart notes were hand searched. We also assessed forms and discussions separately. All primary outcome data were double-coded by two independent, blinded reviewers as described in the Protocol Supplement.20,21

Secondary Patient-reported Outcomes

The validated ACP Engagement Survey was used to measure engagement in the ACP process over time at baseline, 1-week and 3, 6, and 12-months.25,26 This survey includes Behavior Change scores (e.g., self-efficacy and readiness) assessed on a 5-point Likert scale and a 0-25 item Action score (e.g., reported discussions and documentation of ACP wishes, yes/no).

Feasibility and Safety Outcomes

We measured ease-of-use on a 1 (very hard) to 10 (very easy) point scale. Satisfaction was measured by asking about level of comfort, helpfulness and likeliness of recommending the guide to others using a “not-at-all” to “extremely” 5-point Likert scale.21 To assess potential adverse outcomes, we measured depression and anxiety with the validated Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-8 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 questionnaires.27,28

Sample Size

A sample of 350 in each arm allowed 92% power (two-tailed α of 0.05) to detect a difference in ACP documentation between arms of 15% versus 30%.21 With an expected 15% loss-to-follow-up, our recruitment target was 201 English- and 201 Spanish-speakers per arm (804 total), (Protocol Supplement).21

Statistical Methods

We compared baseline characteristics using unpaired t-tests, Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. We performed intention-to-treat analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) and STATA 15.0 (College Station, TX). All p-values were 2-tailed and set at 0.05 for the primary outcome and Bonferroni adjusted for secondary outcomes (p<0.025). Because of differences in ACP engagement by language,10 and based on stakeholder and granting agency recommendations, we decided, a priori, to also stratify all analyses by English- and Spanish-speakers. For our primary outcome of ACP documentation, we used mixed-effects logistic regression with fixed effects for time (baseline and 15 months), group (PREPARE versus AD-only) and group-by-time interaction. For our secondary outcomes of ACP engagement scores, we used mixed-effects linear regression with fixed effects for time (baseline, 1 week, and 3, 6, and 12-months, with time modeled using dummy variables to allow for non-linearity), group and group-by-time interaction. Mixed effects models enable inclusion of all available data in intention-to-treat analyses while accounting for within-subject correlation over time. Because this was a comparative efficacy trial, we calculated within-group pre-post effect sizes using standard, clinically meaningful thresholds (i.e., 0.20-0.49 small, 0.50-0.79 medium, and ≥0.80 large).29 Per stakeholder request, we conducted post-hoc mixed-effects regression to calculate the percentage of participants with increased Behavior Change or Action scores from baseline (i.e., estimated slope > 0) by study arm. All models were adjusted for the blocking variable of health literacy (adequate or limited) and baseline ACP documentation, and accounted for clustering by physician. P-values were Bonferroni adjusted to <0.017.

We also explored effect modification by adding interaction terms to the group-by-time variable for language (English versus Spanish), health literacy (adequate versus limited), desired role in decision-making (makes own decisions versus doctors decide), age (< 65 years versus ≥65 years), gender (women versus men), race/ethnicity (white versus non-white), health status (good-to-excellent versus fair-to-poor), presence of a potential surrogate decision maker (yes versus no), internet access at home (yes versus no), and, for Spanish-speakers, patient-clinician language discordance (concordant versus discordant); p-values <0.05 were considered significant. Definitions and references for all measures are in the Protocol Supplement. Ease-of-use and satisfaction were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, and depression and anxiety, adjusted for baseline scores, were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Missing Data

There were no missing data for the primary outcome. For secondary outcomes, 93.3% of participants had at least one follow-up interview, and all available data were included in the mixed-effects models.

RESULTS

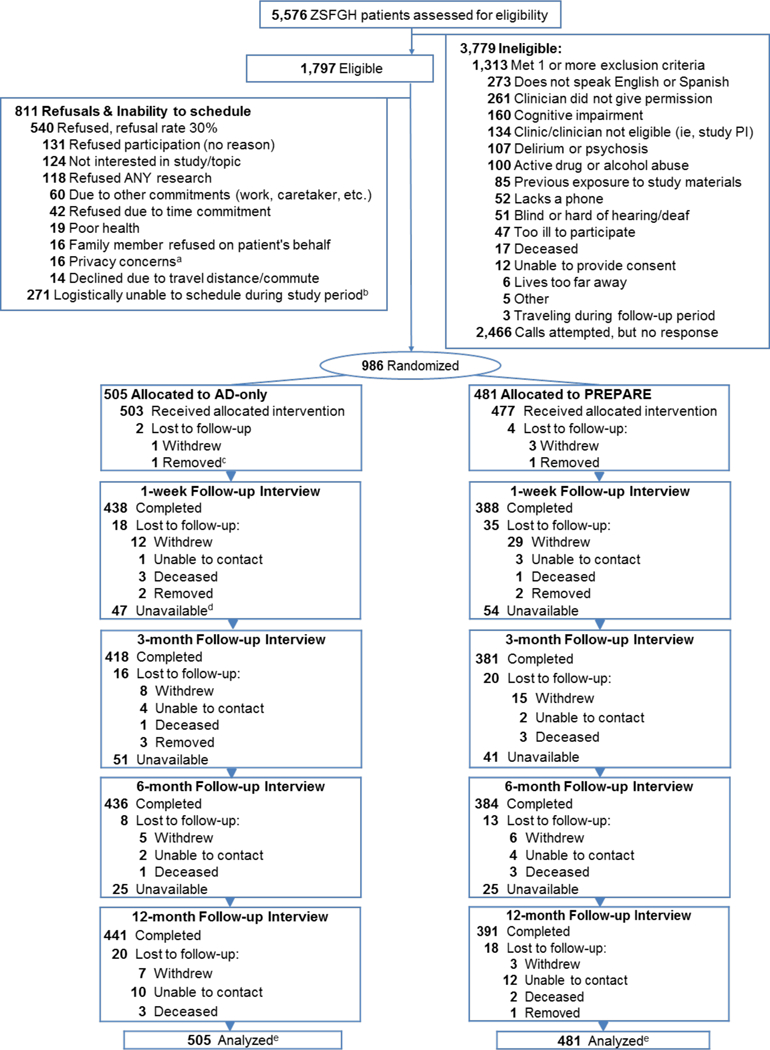

Of 1,797 eligible patients, 986 (54.9%) enrolled; 481 were randomized to PREPARE and 505 to AD-only (Figure 1). The refusal rate was 30%. Those who refused versus enrolled were older, 66.9 (±7.9) versus 63.3 (±6.4) years, p<0.001, but did not otherwise differ. Among enrolled participants, 39.7% had limited health literacy, 51.3% reported fair-to-poor health, 27.3% had any prior ACP documentation, and 10% had ACP documentation during the 12 months prior to intervention (Table 1). Participant characteristics did not differ between arms, except higher prior ACP documentation among Spanish-speakers in the AD-only arm, p=0.04. Twelve-month retention was 85.9% among survivors (Figure 1), and 9% withdrew, 11.6% in PREPARE and 6.5% in the AD-only arm, p=0.04 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). No staff became unblinded.

Figure 1. Consort: Screeninig Enrollment and Follow-up Trial Participants.

aConcerns about privacy of medical information or distrust of the clinic/hospital

bPatient willing to participate, but logistical issues (e.g., work, care taking, travel, illness, etc.) prevented scheduling

C Removed from study for staff safety

dUnavailable participants completed subsequent interviews and were not lost to follow-up

eTotal retention rate of survivors was 85.9%; there were 17 decedents. The AD-only retention rate was 88.7%: there were 8 decedents. The PREPARE arm was 82.8%; there were 9 decedents

Table 1:

Participant Characteristics, n =986

| All Participants n= 986 |

English-speakers n= 541 |

Spanish-speakers n= 445 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Characteristics* | AD-only | PREPARE | AD-only | PREPARE | AD-only | PREPARE |

| n=505 | n=481 | n=279 | n=262 | n=226 | n=219 | |

| Age, mean (SD)† | 63 (6.3) | 63 (6.4) | 62 (5.4) | 63 (6.1) | 64 (7.2) | 64 (6.8) |

| Women, No. (%) | 314 (62.2) | 289 (60.1) | 151 (54.1) | 132 (50.4) | 163 (72.1) | 157 (71.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||

| White, Latino/Hispanic | 248 (49.1) | 251 (52.2) | 24 (8.6) | 35 (13.4) | 224 (99.1) | 216 (98.6) |

| White, non-Latino/Hispanic | 104 (20.6) | 85 (17.7) | 104 (37.3) | 84 (32.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (.5) |

| African American | 92 (18.2) | 86 (17.9) | 92 (33.0) | 86 (32.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 34 (6.7) | 44 (9.1) | 34 (12.2) | 44 (16.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Multi-ethnic/Other | 27 (5.4) | 15 (3.1) | 25 (8.9) | 13 (4.9) | 2 (.9) | 2 (.9) |

| United States Acculturation | ||||||

| Place of Birth, No. (%) | ||||||

| United States | 219 (43.3) | 193 (40.2) | 216 (77.4) | 192 (73.6) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.5) |

| South America | 17 (3.4) | 13 (2.7) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) | 13 (5.7) | 10 (4.6) |

| Central America | 161 (31.9) | 154 (32.1) | 9 (3.2) | 7 (2.7) | 152 (67.3) | 147 (67.1) |

| North American Latino Countries | 63 (12.5) | 67 (14.0) | 5 (1.8) | 6 (2.3) | 58 (25.7) | 61 (27.8) |

| Other | 45 (8.9) | 53 (11.0) | 45 (16.1) | 53 (20.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| If born outside US, years in the US, mean (SD) | 27 (13.3) | 27 (13.3) | 32 (16.5) | 33 (16.5) | 26 (11.9) | 26 (11.7) |

| Education ≤ high school, No. (%) | 287 (56.8) | 289 (60.1) | 102 (36.6) | 102 (38.9) | 185 (81.9) | 187 (85.4) |

| Limited Health Literacy, No. (%) | 202 (40.3) | 185 (39.0) | 60 (21.7) | 56 (21.7) | 142 (63.1) | 129 (59.7) |

| Patient-Clinician Language Discordance: No. (%) | 86 (41.2) | 65 (32.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 86 (41.2) | 65 (32.2) |

| Finances, not enough to make ends meet, No. (%) | 124 (25.0) | 119 (25.1) | 65 (23.8) | 56 (21.5) | 59 (26.5) | 63 (29.4) |

| Financial social standing 1-10 score, mean (SD) | 6.1 (7.7) | 6.0 (6.9) | 6.4 (7.3) | 6.6 (9.1) | 5.8 (8.1) | 5.3 (2.3) |

| Religious, fairly to extremely, No. (%) | 267 (53.4) | 245 (51.6) | 150 (54.6) | 140 (54.3) | 117 (52.0) | 105 (48.4) |

| Spiritual, fairly to extremely, No. (%) | 332 (66.3) | 296 (62.1) | 190 (68.8) | 173 (66.8) | 142 (63.1) | 123 (56.4) |

| Social Support | ||||||

| Measure of Social Support score 11-55, mean (SD) | 38.3 (11.7) | 37.9 (11.8) | 39.8 (10.6) | 38.6 (11.2) | 36.5 (12.7) | 37.0 (12.4) |

| In a married/long term relationship, No. (%) | 179 (35.5) | 166 (34.7) | 98 (35.1) | 80 (30.7) | 81 (35.8) | 86 (39.5) |

| Have adult children, No. (%) | 374 (74.2) | 362 (75.4) | 173 (62.2) | 168 (64.4) | 201 (88.9) | 194 (88.6) |

| Have a potential surrogate, No. (%) | 482 (95.5) | 463 (96.5) | 263 (94.3) | 246 (93.9) | 219 (96.9) | 217 (99.5) |

| Health and Functional Status | ||||||

| Self-Rated Health, fair-to-poor, No. (%) | 249 (49.4) | 255 (53.2) | 122 (43.9) | 128 (49.0) | 127 (56.2) | 127 (58.3) |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Difficulty score 0-16, mean (SD) | 2.7 (3.8) | 2.6 (3.5) | 2.9 (3.9) | 2.8 (3.6) | 2.5 (3.6) | 2.4 (3.4) |

| Activities of Daily Living Difficulty score 0-12, mean (SD) | 1.8 (2.2) | 1.7 (2.1) | 1.8 (2.2) | 1.8 (2.4) | 1.9 (2.2) | 1.6 (1.8) |

| Depression, moderate-to-severe, No. (%)† | 64 (12.7) | 60 (12.5) | 35 (12.5) | 33 (12.6) | 29 (13.0) | 27 (12.3) |

| Anxiety, moderate-to-severe, No. (%)† | 61 (12.1) | 42 (8.7) | 35 (12.5) | 21 (8.0) | 26 (11.5) | 21 (9.6) |

| Desired Role in Decision Making | ||||||

| Low Decision Control Preference (i.e., doctors make all medical decisions), No. (%) | 44 (8.8) | 52 (11.0) | 11 (4.0) | 19 (7.4) | 33 (14.8) | 33 (15.3) |

| Internet Access | ||||||

| Access to the internet in the home, No. (%) | 265 (52.6) | 228 (47.5) | 187 (67.3) | 171 (65.3) | 78 (34.5) | 57 (26.1) |

| Prior planning activities | ||||||

| Completed a will, No. (%) | 57 (11.4) | 71 (14.8) | 37 (13.3) | 51 (19.5) | 20 (8.9) | 20 (9.2) |

| Made funeral arrangements, No. (%) | 118 (23.7) | 114 (23.8) | 62 (22.6) | 60 (23.1) | 56 (25.1) | 54 (24.7) |

| Any Prior ACP documentation*, No. (%) | 148 (29.3) | 121 (25.2) | 84 (30.1) | 77 (29.4) | 64 (28.3)§ | 44 (20.1)§ |

| Legal forms | 89 (17.6) | 79 (16.4) | 45 (16.1) | 50 (19.1) | 44 (19.5) | 29 (13.2) |

| Documented discussions about ACP | 81 (16.0) | 64 (13.3) | 52 (18.6) | 43 (16.4) | 29 (12.8) | 21 (9.6) |

| Baseline ACP documentation rate 12-months before intervention exposure, No. (%) | 58 (11.5) | 41 (8.5) | 36 (12.9) | 28 (10.7) | 22 (9.7) | 13 (5.9) |

All variables are defined including reliability, validity, response options, scoring, and references in the online protocol and the published protocol.21 Results are presented as means with standard deviations (SD) and as numbers (No.) and percent (%).

Depression is measured with the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (scores 0-24) and anxiety is measured with the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder screening measure (scores 0-21). Moderate-to-severe depression or anxiety are defined by scores on both assessments of greater than 10.21

Any Prior ACP documentation includes any prior legal forms (i.e., advance directives, Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare, and Physicians Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment) and documented ACP discussions in the past 5 years (i.e., oral directives or goals of care notes by clinicians)._ENREF_2121

There were no significant between-group differences for any patient characteristic overall and for English- or Spanish-speakers (P<0.05), except for any previous ACP documentation among Spanish-speakers, p =0.04.

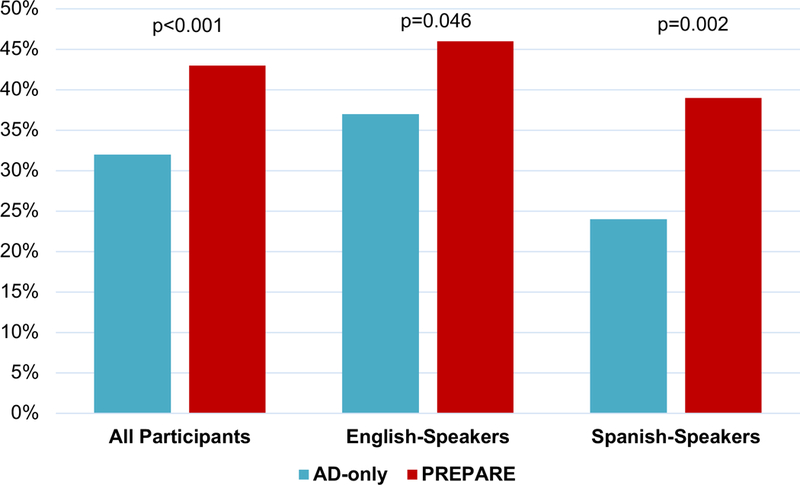

New overall ACP documentation at 15-months was higher in the PREPARE versus AD-only arm; unadjusted 43% versus 33%, p<0.001 and adjusted 43% versus 32%, p<0.001. All differences were significant for English- and Spanish-speakers (Figure 2). When assessed separately, documentation of legal forms was higher in the PREPARE versus AD-only arm (26% versus 13%, p<0.001), but did not differ between arms for documented discussions (31% versus 26%, p=0.10). There were no significant interaction effects of any participant characteristics, including health literacy, desired role in decision making, and patient-clinician language concordance for Spanish-speakers, for ACP documentation (eTable 2).

Figure 2.

New Advance Care Planning Documentation in the Medical Record*

The PREPARE arm included the www.prepareforyourcare.org website plus an easy-to-read advance directive. The AD-only arm included only the easy-to-read advance directive. Statistical significance set at p < 0.05 for this primary outcome.

Number of All Participants: n=986 overall; PREPARE=481 and AD-only=505. Number of English-speakers: n=541 overall; PREPARE=262 and AD-only=279. Number of Spanishspeakers: n=445overall; PREPARE=219 and AD-only=226.

*Documentation was determined by objective electronic medical record chart review by two independent reviewers. All models were adjusted for literacy, baseline ACP documentation, and clustering by physician.

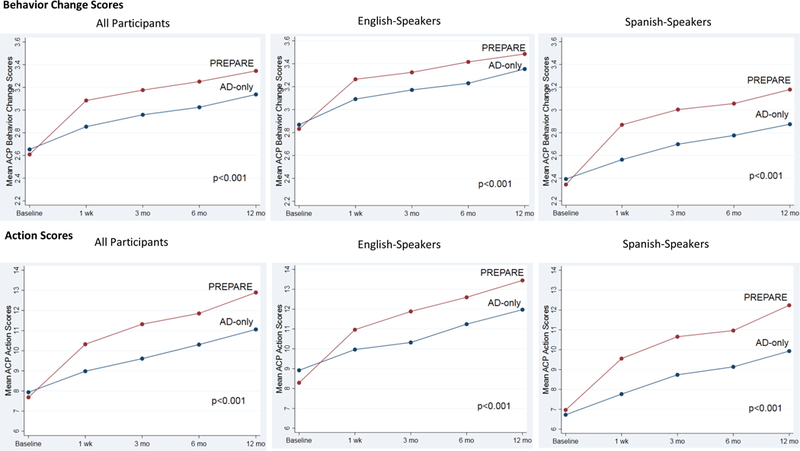

Mean ACP Behavior Change and Action scores increased significantly more in the PREPARE versus AD-only arm overall and for English- and Spanish-speakers, p<0.001 for all time points (Figure 3). Effect sizes were medium-to-large for PREPARE and small-to-medium for the AD-only (eTable 3).29 In the PREPARE arm, 98.1% of participants reported increased ACP Engagement (Behavior Change or Action) scores over time versus 89.5% for the AD-only arm (Table 2). When examined separately, Behavior Change scores (97.5% versus 87.3%) and Action scores (94.8% versus 78.4%), were also higher for PREPARE versus AD-only, all p-values <0.001 (Table 2). Increases were significant for all types of ACP activities as well as for discussion-specific and documentation-specific ACP activities and among English and Spanish-speakers (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Advance Care Planning Engagement Behavior Change and Action Scores Overall and by English and Spanish

AD-only indicates advance directive only arm; PREPARE-AD the patient-centered, advance care planning website plus AD arm. Behavior Change on a 5-point Likert scale. Action scores 0-25. P-values reflect significance for overall group + time interactions using repeated measures, mixed effects linear regression models adjusted for health literacy, baseline ACP documentation, and clustering by physician. Statistical significance set at p < 0.025 to account for multiple comparisons for the two outcomes of Behavior Change and Action Scores. No additional p-value adjustments were made for analyses stratified by language as these were pre-specified. P-values reflect group by time interactions. In addition, all p-values for time were also < 0.001 (i.e., both PREPARE and AD-only increased significantly from baseline).

Table 2:

Percent of Participants with Increased Advance Care Planning Behavior Change and Actions Scores Over Time

| Improvement in Behavior Change and ACP Actions* |

Improvement in ACP Behavior Change only |

Improvement in ACP Actions only |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD-only | PREPARE | p-value | AD-only | PREPARE | p-value | AD-only | PREPARE | p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| All Participants | n=505 | n=481 | n=505 | n=481 | n=505 | n=481 | |||

| All ACP Activities† | 452 (89.5) | 472 (98.1) | <.001 | 441 (87.3) | 469 (97.5) | <.001 | 396 (78.4) | 456 (94.8) | <.001 |

| Documentation | 431 (85.4) | 476 (99.0) | <.001 | 419 (83.0) | 472 (98.1) | <.001 | 237 (46.9) | 422 (87.7) | <.001 |

| Discussions | 453 (89.7) | 474 (98.5) | <.001 | 430 (85.2) | 464 (96.5) | <.001 | 397 (78.6) | 451 (93.8) | <.001 |

| English-speakers | n=279 | n=262 | n=279 | n=262 | n=279 | n=262 | |||

| All ACP Activities | 263 (94.3%) | 259 (98.9%) | .004 | 258 (92.5%) | 257 (98.1%) | .002 | 223 (79.9%) | 250 (95.4%) | <.001 |

| Documentation | 247 (88.5%) | 261 (99.6%) | <.001 | 236 (84.6%) | 258 (98.5%) | <.001 | 166 (59.5%) | 252 (96.2%) | <.001 |

| Discussions | 257 (92.1%) | 258 (98.5%) | <.001 | 249 (89.3%) | 255 (97.3%) | <.001 | 212 (76.0%) | 248 (94.7%) | <.001 |

| Spanish-speakers | n=226 | n=219 | n=226 | n=219 | n=226 | n=219 | |||

| All ACP Activities | 189 (83.6%) | 213 (97.3%) | <.001 | 183 (81.0%) | 212 (96.8%) | <.001 | 173 (76.6%) | 206 (94.1%) | <.001 |

| Documentation | 184 (81.4%) | 215 (98.2%) | <.001 | 183 (81.0%) | 214 (97.7%) | <.001 | 71 (31.4%) | 170 (77.6%) | <.001 |

| Discussions | 196 (86.7%) | 216 (98.6%) | <.001 | 181 (80.1%) | 209 (95.4%) | <.001 | 185 (81.9%) | 203 (92.7%) | <.001 |

The validated Advance Care Planning (ACP) Engagement Survey includes both self-reported Behavior Change and Action Scores. Percentages reflects participants with positive slopes over time, adjusted for health literacy, baseline ACP documentation, and clustering by physician.

“All ACP Activities” is a composite measure of Behavior Change and Action scores. We present slopes for all reported ACP activities as well as ACP documentation-specific and ACP discussion-specific activities. To specifically assess engagement in ACP discussions or documentation, we categorized ACP Engagement Survey items into those related to Discussions (i.e. survey item referred to “ask” or “talk”) and Documentation (i.e. survey item referred to “signing” or “documenting”).

Statistical significance set at p=0.017 to account for multiple comparisons for the three outcomes of improvement in behavior change or action, behavior change only and action only. No additional p-value adjustments were made for analyses stratified by language as these were pre-specified.

Reported ease-of-use and satisfaction were high and did not differ between arms, except PREPARE was perceived as more helpful than the AD-only overall and by English and Spanish-speakers, p<0.001 (eTable 4). No adverse events were reported and adjusted mean depression and anxiety scores at 12-months did not differ between arms overall or for English- or Spanish-speakers (eTable 5).

DISCUSSION

In a diverse cohort of 986 English- and Spanish-speaking older adults in a safety-net setting, with high rates of chronic disease and limited health literacy, both the easy-to-read advance directive and the patient-directed, interactive online PREPARE program significantly increased ACP documentation and patient-reported ACP engagement, with significantly greater gains in the PREPARE arm. This was achieved without additional clinician or system-level interventions. To our knowledge, this is the largest, most culturally diverse trial of patient-facing advance care planning interventions.

These results are important because, historically, studies demonstrate limited ACP engagement among low-income, diverse and Spanish-speaking older adults as well as a dearth of literacy-, culturally-, and linguistically-appropriate patient-facing ACP materials.9,14-16 The observed ACP documentation gains in this trial (43%) and a prior PREPARE trial among veterans (35%),20 are likely the result of a combination of novel health communication components of the patient-directed, interactive, online PREPARE program. These include co-creation with and for diverse populations to mitigate literacy, cultural and language barriers,10,18 theory-based content designed to enhance self-efficacy and readiness, and the use of narratives, testimonials, video stories and modeling of behaviors; strategies demonstrated to help patients make ACP decisions.30 The magnitude of improvement in documentation is clinically meaningful given the known deficiencies in clinician documentation, especially documented discussions.31 The high proportion of patient-reported ACP engagement for both documentation (85%) and discussions (94%) in the PREPARE arm further validates our medical record findings and demonstrates that patients engage in a range of ACP behaviors, such as discussions with surrogates and clinicians, in addition to documentation.19,23,32

Prior studies of patient-directed ACP tools in primary care have been less effective in increasing ACP documentation (5-23%) than coaching or facilitation.7,33,34 The use of trained clinicians or ACP facilitators has shown improvements of 50% or more among English- and Spanish-speaking patients.3,7,33-38 However, many healthcare organizations, especially public and safety-net settings, do not have resources for dedicated, trained ACP facilitators. This study demonstrates that PREPARE and the easy-to-read AD enable many patients to initiate and engage in the ACP process on their own, without the need for trained facilitators. All care plans should be reviewed by a medical provider within the patient’s clinical context. In addition, some individuals will need additional support to engage in ACP. Future research should explore whether PREPARE results in comparable ACP quality to trained facilitators and whether combining PREPARE and the easy-to-read AD with other clinician or system-level interventions results in synergistic gains.

Limitations

Generalizability may be limited as participants were recruited from one integrated public-health delivery system in San Francisco; however, the sample was racially and ethnically diverse. It was not possible to blind participants; however, research staff were blinded for all follow-up assessments. Although limited staff support was provided, the interventions were viewed in research offices, and we do not have information concerning the questions asked of staff. Similarly, study interviews and reminder calls may have been activating. Additional studies are needed to determine whether similar results may be obtained if the materials are viewed at home or without reminder calls; often a regular part of primary care. Alternatively, because PREPARE was compared to an evidenced-based, easy-to-read AD, PREPARE’s real-world effect compared to usual care may have been underestimated. Finally, we did not assess ACP quality nor longitudinal effects on the receipt of medical care aligned with patients’ values or costs. Shorter versions of PREPARE are now available for home use and future longitudinal effectiveness trials are needed and are underway.

Conclusion

The patient-facing, easy-to-read advance directive and the patient-directed, interactive, online PREPARE program, without additional system or clinician interventions, can substantially increase advance care planning documentation and engagement. PREPARE plus an easy-to-read advance directive resulted in higher advance care planning documentation and engagement than the advance directive alone, an effect that remained across English and Spanish-speakers and participants with limited health literacy. This study suggests that PREPARE and the easy-to-read directive are useful and potentially scalable advance care planning interventions for diverse populations. These patient-directed interventions may mitigate literacy, cultural, and language barriers to advance care planning, allow patients to begin planning on their own, and could substantially improve the process for diverse, English- and Spanish-speaking populations.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS:

Question: Can a patient-facing, online program called PREPARE plus an easy-to-read advance directive increase advance care planning documentation and engagement compared to an advance directive alone?

Acknowledgments

Findings: In this randomized trial of 986 English- and Spanish-speaking older adults with chronic illness from four primary care clinics, PREPARE plus an easy-to-read advance directive resulted in higher advance care planning documentation (43% vs. 32%) and engagement (98% vs. 89%) compared to an advance directive alone.

Funding Source: Research reported in this publication was supported through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Aging (NIA) (R01AG045043) and a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (CDR-1306-01500). The statements in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. Development of PREPARE was supported by the S.D. Bechtel Jr. Foundation, the California Healthcare Foundation, and the National Palliative Care Research Center. Dr. Sudore is also funded in part by an NIH, NIA K24AG054415. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, data collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, data collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Additional Contributions: None

Meaning: Patient-facing tools, including PREPARE and an easy-to-read advance directive, enable diverse populations to engage in the advance care planning process without additional clinician/system-level interventions.

Data Sharing:

Investigators may submit proposals for consideration to rebecca.sudore@ucsf.edu for use of de-identified data collected during this trial following publication with no end date, subject to approval by the study team, requesters’ local IRB, and institutional data use agreements.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

References

- 1.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicine, Institute of. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pope TM Legal Briefing: Medicare Coverage of Advance Care Planning. J Clin Ethics. 2015;26(4):361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsaroop SD, Reid MC, Adelman RD Completing an advance directive in the primary care setting: what do we need for success? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, et al. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(9):778–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakauer EL, Crenner C, Fox K Barriers to optimum end-of-life care for minority patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Barnes DE, et al. An advance directive redesigned to meet the literacy level of most adults: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1-3):165–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawley L, Payne R, Bolden J, Payne T, Washington P, Williams S Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2518–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1145–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwak J, Haley WE Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45(5):634–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison KL, Adrion ER, Ritchie CS, Sudore RL, Smith AK Low Completion and Disparities in Advance Care Planning Activities Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1872–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong M, Yi EH, Johnson KJ, Adamek ME Facilitators and Barriers for Advance Care Planning Among Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S.: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castillo LS, Williams BA, Hooper SM, Sabatino CP, Weithorn LA, Sudore RL Lost in translation: the unintended consequences of advance directive law on clinical care. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, et al. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the Control Preferences Scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):688–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sudore RL, Knight SJ, McMahan RD, et al. A novel website to prepare diverse older adults for decision making and advance care planning: a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(4):674–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudore RL, Fried TR Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudore RL, Boscardin J, Feuz MA, McMahan RD, Katen MT, Barnes DE Effect of the PREPARE Website vs an Easy-to-Read Advance Directive on Advance Care Planning Documentation and Engagement Among Veterans: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1102–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sudore RL, Barnes DE, Le GM, et al. Improving advance care planning for English-speaking and Spanish-speaking older adults: study protocol for the PREPARE randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Williams BA, Barnes DE, Lindquist K, Schillinger D Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):867–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821–832.e821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, et al. Health Literacy not Race Predicts End-of-Life Care Preferences. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudore RL, Stewart AL, Knight SJ, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to detect behavior change in multiple advance care planning behaviors. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Barnes DE, et al. Measuring Advance Care Planning: Optimizing the Advance Care Planning Engagement Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(4):669–681 e668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ:: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Jawahri A; Paasche-Orlow MK; Matlock D; Stevenson LW; Lewis EF; Steward G; Semigram M; Chang Y; Parks K; Walker-Corkery ES; Temel JS; Bohossian H; Ooi H; Mann E; Volandes AE. Randomized, Controlled Trial of an Advance Care Planning Video Decision Support Tool for Patients With Advanced Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;134(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker E, McMahan R, Barnes D, Katen M, Lamas D, Sudore R Advance Care Planning Documentation Practices and Accessibility in the Electronic Health Record: Implications for Patient Safety. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Lum HD, et al. Outcomes that Define Successful Advance Care Planning: A Delphi Panel Consensus. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC Tools to Promote Shared Decision Making in Serious Illness: A Systematic Review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1213–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butler M, Ratner E, McCreedy E, Shippee N, Kane RL Decision aids for advance care planning: an overview of the state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammes BJ, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD A comparative, retrospective, observational study of the prevalence, availability, and specificity of advance care plans in a county that implemented an advance care planning microsystem. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1249–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearlman RA, Starks H, Cain KC, Cole WG Improvements in advance care planning in the Veterans Affairs System: results of a multifaceted intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(6):667–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer SM, Cervantes L, Fink RM, Kutner JS Apoyo con Carino: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a Patient Navigator Intervention to Improve Palliative Care Outcomes for Latinos With Serious Illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(4):657–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maldonado LY, Goodson RB, Mulroy MC, Johnson EM, Reilly JM, Homeier DC Wellness in Sickness and Health (The W.I.S.H. Project): Advance Care Planning Preferences and Experiences Among Elderly Latino Patients. Clin Gerontol. 2017:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.