Abstract

Cannabis and tobacco co-use is prevalent, but consensus regarding the reasons for co-use among adults and the degree of interrelatedness between these substances is lacking. Reasons for co-use have been explored with younger users, but little data exists for more experienced users with entrenched patterns of co-use. The goal of this study was to examine characteristics and patterns of cannabis-tobacco co-use among adults in the Southeastern United States (US), where there is a legal landscape of generally restrictive cannabis legislation coupled with more permissive tobacco control compared to other US regions. Participants (N=432) were regular cannabis users recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk. Measures included demographics, patterns of cannabis and tobacco use, and reasons for co-use. Within this sample, 42% were current users of tobacco (n=182). Cannabis-tobacco co-users were older and had more years of cannabis use than cannabis-only users. Among the co-using sub-sample, there was little consistency in the reasons for co-use, suggesting individual differences in the use of both substances. High levels of cannabis-tobacco interrelatedness (i.e., temporally concurrent use) were associated with smoking more cigarettes (tobacco) per day and greater nicotine dependence scores when compared to users with low levels of interrelatedness. Though these results are limited by a small sample size and generalizability issues, there were individual differences in cannabis-tobacco relatedness, which may be of importance when considering treatment strategies for cannabis, tobacco, or both. With additional research, personalized strategies adapted to cannabis-tobacco relatedness profiles among co-users may be warranted as a treatment strategy.

Keywords: cannabis, marijuana, tobacco, nicotine, co-use, polysubstance use

1. Introduction

Cannabis use is increasingly common in the United States (US) (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015). In 2015, data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health showed that 20% of young adults aged 18-25 and 7% of adults aged 26 and older had used cannabis at least once in the past 30 days (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016). Rates of cannabis use and occurrence of cannabis use disorder (CUD) appear to be increasing among adults (Compton, Han, Jones, Blanco, & Hughes, 2016; Hasin et al., 2016), while the perception of harm associated with cannabis use is declining among adolescents and adults (Johnston et al., 2017; Pacek, Mauro, & Martins, 2015). The perception of minimal risk for cannabis has, in part, contributed to the increasing frequency of use (Compton, Han, Jones, Blanco, & Hughes, 2016). While the perception of harm of cannabis use is low, especially when compared to other substances of abuse (e.g., heroin, cocaine), cannabis use is still associated with a number of adverse health outcomes. Cannabis use may lead to the development of CUD, the onset of withdrawal symptoms, impaired driving ability, increased rates of anxiety and depression, and potentially the development of respiratory issues if smoked (Feeney & Kampman, 2016; Volkow, Baler, Compton, & Weiss, 2014). An additional health concern among cannabis users is the prevalent co-use of other substances and their interrelatedness and interdependence, namely tobacco.

The co-use of tobacco and cannabis is a common practice (Agrawal et al., 2008; Agrawal, Budney, & Lynskey, 2012; Agrawal & Lynskey, 2009; Leatherdale, Ahmed, & Kaiserman, 2006; Leatherdale, Hammond, Kaiserman, & Ahmed, 2007; Richter et al., 2004; Tullis, DuPont, Frost-Pineda, & Gold, 2003) and may occur in several forms. For example, co-use has been defined in several recent nationally representative studies from the US as the use of both substances within the past 30 days (Schauer, Berg, Kegler, Donovan, & Windle, 2016; Schauer & Peters, 2018; Schauer, Peters, Rosenberry, & Kim, 2017), but without specifically accounting for the relationship between the two. Additionally, the World Health Organization defines “multiple drug use” as the use of several drugs by the same individual, with emphasis on the simultaneous or sequential nature of use (World Health Organization, 1994). In addition to asynchronous substance use, co-use may also occur in a simultaneous manner (cigar wrappers filled with cannabis ‘blunts’ or cannabis and loose leaf tobacco rolled together in a joint ‘spliff’ or ‘mulled cigarette’), or sequentially (‘chasing’ cannabis with tobacco). For the purposes of the current study, we defined co-use as any use of cannabis and tobacco in the past 30 days, but explored reasons and methods of co-use further among this study sample. Rates of co-use have increased from 2003 through 2012 (Schauer, Berg, Kegler, Donovan, & Windle, 2015) and rates of daily co-use doubled from 2002-2014 in the US (Goodwin et al., 2018). Cannabis-tobacco co-use is also a common phenomenon in Europe and tends to occur more frequently in a simultaneous manner compared to the US (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2017; Hindocha, Freeman, Ferris, Lynskey, & Winstock, 2016). Cigarette smoking is related to higher rates of lifetime and past 30-day cannabis use (Kong, Singh, Camenga, Cavallo, & Krishnan-Sarin, 2013). Congruently, among cannabis users, daily and non-daily tobacco co-use is highly prevalent (40% to 78%, when including blunt users; Pacek et al., 2018; Schauer, Berg, et al., 2016). Several studies have shown that the use of cannabis is associated with increased risk of nicotine dependence and greater levels of nicotine dependence (Agrawal, Lynskey, et al., 2008; Agrawal, Madden, Bucholz, Heath, & Lynskey, 2008; Okoli, Richardson, Ratner, & Johnson, 2008; Wang, Ramo, Lisha, & Cataldo, 2016).

There are a number of associated problems attributed to cannabis-tobacco co-use, including greater prevalence of psychiatric and psychosocial problems (Peters, Schwartz, Wang, O’Grady, & Blanco, 2014; Ramo, Liu, & Prochaska, 2012) and additive health risk due to co-use of both substances (Meier & Hatsukami, 2016). Also, co-users tend to have worse cannabis cessation outcomes compared to former- and non-tobacco users (Gray et al., 2017; McClure, Baker, & Gray, 2014; Moore & Budney, 2001; Peters et al., 2014). This finding raises treatment-related concerns for interventions that are developed for cannabis alone, but are recruiting a co-using sample. With diversity in tobacco and cannabis use patterns, it is important to explore the methods of and reasons for co-use among a population of experienced users in order to improve treatment strategies, which may vary based on the characteristics of the user and their use patterns.

It may also be important to consider regional variations in tobacco-cannabis co-use within the US given that cannabis legislation and tobacco control varies state by state, and sometimes in opposing directions. Recent studies have shown differences in cannabis use patterns among states that have legalized recreational cannabis (Borodovsky, Crosier, Lee, Sargent, & Budney, 2016; Daniulaityte et al., 2015; Lamy et al., 2016). Few states in the Southeastern US have operational medical or recreational cannabis, which makes it unique from other regions of the country with widely accessible cannabis dispensary systems. Regardless, increases in cannabis use and rates of CUD have been found in the Southeastern US from 2001-2002 to 2012-2013 (Hasin et al., 2015). Additionally, tobacco use tends to be more prevalent in the Southeastern US as compared to other areas of the country (Nguyen, Marshall, Brown, & Neff, 2016). Within a recent national cannabis cessation clinical trial, lower rates of tobacco co-use were found in the overall sample (38%; Gray et al., 2017) compared to national averages of co-use (Pacek et al., 2018; Schauer, Berg, et al., 2016), though in that trial (Gray et al., 2017), tobacco co-use rates varied based on study site and geographical location in the US. In the two study sites that fell within the Southeastern region of the US, 50% of cannabis users were also tobacco users, compared to 34% at other sites (McClure et al., 2018). Taken together, the Southeastern region of the US is unique when considering cannabis and tobacco co-use and worthy of focused study.

There is limited consensus on the specific reasons and mechanisms for cannabis-tobacco co-use, though candidate mechanisms have been proposed, including the potential for synergistic drug effects among some co-users (Rabin & George, 2015). The degree of relatedness of cannabis-tobacco co-use is an important area of research and individual differences in relatedness are also important to characterize among this population. We define high interrelatedness of cannabis-tobacco co-use as that which occurs simultaneously or sequentially (i.e., temporally related and occurring within the same use episode), or as one substance having a discernible impact on use of the other. Low interrelatedness refers to cannabis-tobacco use that occurs independently, at different times, and for seemingly different reasons, but within the same individual. Some work on the reasons for co-use has been conducted previously among adolescents and emerging adults (Berg et al., 2018; Ramo, Liu, & Prochaska, 2013; Schauer, Hall, et al., 2016), though the relatedness of tobacco and cannabis may differ for adults who have an extended history of use with both substances. Therefore, the goal of the current study was to collect preliminary data on cannabis-tobacco co-use patterns and relatedness through a cross-sectional survey of adults in the South Atlantic region of the US. This study had the following aims: 1) compare characteristics of cannabis only users with cannabis-tobacco co-users; 2) assess self-reported reasons for co-use of cannabis and tobacco (co-using sample only); and 3) assess the relationship and interrelatedness between use of cannabis and tobacco among the sample. In this study, participants were regular users of cannabis (use on 20 out of the past 30 days) and a sub-sample of participants reported smoking combustible cigarettes in the past 30 days (defined as the co-using sample).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment Source

This study was a cross-sectional, one-time, anonymous survey of cannabis and tobacco use patterns and reasons for use among adults (ages 18 and over). Participants were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online crowdsourcing service and marketplace. MTurk offers potential access to many hard-to-reach clinical populations (i.e., non-treatment seeking cannabis users), though the demographics may not be representative of national samples or clinical populations (Buhrmester, Talaifar, & Gosling, 2018). MTurk has been used previously in other substance use studies to recruit clinical populations (Adkison, O’Connor, Chaiton, & Schwartz, 2015; Peters, Rosenberry, Schauer, O’Grady, & Johnson, 2017; Rass, Pacek, Johnson, & Johnson, 2015; Strickland & Stoops, 2015; 2018). The MTurk population has been found to be demographically younger and to over-represent male and White participants, but is generally ethnically diverse and had similar psychopathology scores compared to a community sample (McCredie & Morey, 2018), though a similar study found a higher rate of endorsing symptoms of depression, higher levels of education (bachelors and above), and lower rates of smoking cigarettes (Walters, Christakis, & Wright, 2018). Demographics of our study sample were numerically (not statistically) compared to Census data from same region of the US to assess the representativeness of our MTurk sample (shown in the Results section).

The study opportunity was presented as a Human Intelligence Task (HIT) to MTurk workers. Recruitment postings asked for any MTurk user who had ever used cannabis or any other drug to complete a screener, and if eligible, complete the full survey (delivered via the Research Electronic Data Capture platform [REDCap]; Harris et al., 2009). Inclusion in this study required residence in a Southern state (as defined by the US census as the South Atlantic region and the East South Central region; Alabama, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia), age of 18 years or older (no upper age limit), and cannabis use on at least 20 of the past 30 days. With the exception of DC and DE, medical or recreational cannabis was either illegal or distribution was not yet operational or was limited to a few medical conditions (FL, MD, and WV) at the time of survey administration (June 2017 through August 2017). Though cannabis legislation varied across the selected states in the Southeastern US, we opted to include all states from these Census regions. Prior to survey administration, we were not able to predict response rates from each state, and had the option to exclude certain states from the analyses, if deemed necessary.

2.2. Procedures

The full questionnaire included 40-70 questions; branching logic differed depending on whether respondents were current or former co-users of tobacco. Current tobacco use was defined any combustible cigarette use in the past 30 days. The entire survey took approximately 20-30 minutes to complete. Compensation for study participation was provided through MTurk. Participants received $1.00 for the completing the full survey, and an additional bonus payment of $1.50 if they correctly answered attention-check questions. The total possible compensation for survey completion was $2.50, which is consistent with other studies (Peters et al., 2017).

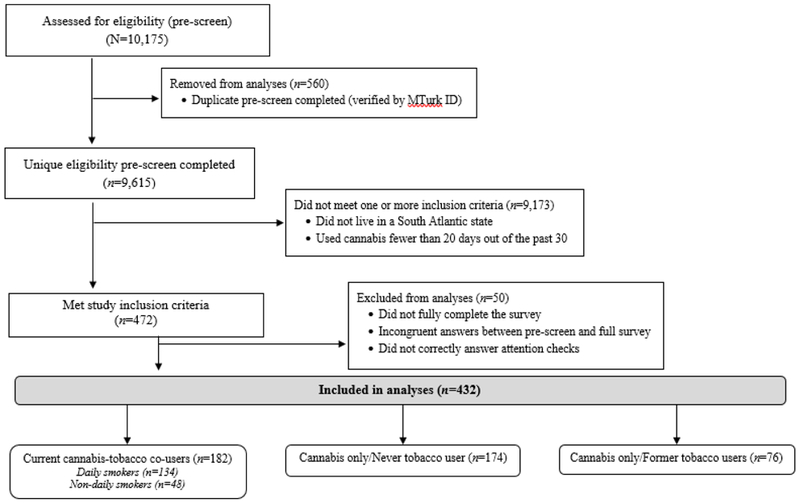

A flow chart of survey respondents is shown in Figure 1. A total of 10,175 MTurk workers completed the eligibility screener (n=560 were determined to be duplicate records and were removed). Of those remaining (n=9,615), 472 (5%) were eligible based on inclusion criteria. Fifty participants were excluded from analyses for not completing the survey, failing attention check questions (e.g., “Please select Agree”), or having incongruent answers between the eligibility pre-screener and full survey, resulting in a final sample of 432 participants, of which 182 (42%) were current cannabis-tobacco co-users.

Figure 1:

Flowchart of Survey Respondents.

2.3. Measures

The full survey included questions on demographics, cannabis use history and current use patterns (quantity, frequency, potency, reasons for use, etc.), and the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R), which is a scale from 0-32 in which a score of 13 or higher was found to be predictive of hazardous/problematic cannabis use (Adamson et al., 2010). Respondents were then asked about their tobacco use status and were classified as current, former, or never smokers. Current (daily and non-daily) smokers were asked about their tobacco use history, current use patterns, previous quit attempts, and completed the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), a scale of 0-10 in which a score of 4 or greater indicates moderate levels nicotine dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991).

Current cannabis-tobacco co-users were also asked about their reasons for co-use of cannabis and tobacco and the interrelatedness of their co-use, e.g, “Tobacco improves my high from marijuana.” The questions were locally developed by the research team and focused on the following topics: behavioral/use patterns of both substances (increasing use of one substance while using the other, mixing together, one immediately follows use of the other), perceived interrelatedness (subjective responses such as improved high, alertness, satisfaction, as well as use for different reasons, separate use), and craving. Twelve co-use questions were asked using a 5-point Likert scale response format. Because these questions were locally developed and had not been previously validated, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to ensure that the items appeared to be measuring one or more related factors. As a result of the EFA, 8 items were retained and a total score of relatedness was computed by summing these items. Scores ranged from 8 to 40 with higher values indicating greater relatedness of cannabis and tobacco co-use for that individual. Further technical details are available in an Appendix.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Differences between cannabis only participants and cannabis-tobacco co-users were compared using Chi-square tests for categorical data and independent samples t-test for continuous data. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0 and SAS Version 9.4 and an alpha level of p<0.05 was used for all statistical analyses. Pearson correlations were conducted between the relatedness measure and demographic, cannabis, and tobacco use characteristics. To explore associations between interrelatedness scores and other relevant variables, a median split was used to divide the sample into high (greater than 23) and low related co-use (less than or equal to 23) for descriptive purposes. Linear regression was also used to examine multivariate associations between demographics, cannabis, and tobacco use characteristics as predictors of the total cannabis-tobacco interrelatedness score.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics, Cannabis, and Tobacco Use Characteristics (Aim #1)

Among this sample (N=432), 134 participants (31.0%) were current daily tobacco users, 48 participants (11.1%) were non-daily current tobacco users, 76 participants (17.6%) were former tobacco users, and 174 participants (40.3%) were never tobacco users. Demographic information for the total sample is shown in Table 1 and is separated by current cannabis-tobacco co-users (daily and non-daily tobacco users) and cannabis only users (former tobacco users included). Overall, the sample was mostly female (60.2%) and White (73.8%). Cannabis-tobacco co-users did not differ from cannabis only users on most demographic characteristics, except that cannabis-tobacco co-users tended to be older (M=34.28; SD=9.76) compared to the cannabis only respondents (M=31.86; SD=10.148); t(430)=−2.44, p=0.015.

Table 1.

Demographics and cannabis use characteristics for the total sample and separated by cannabis-tobacco co-users and cannabis only users.

| Demographics | Total (N=432) | Cannabis- Tobacco Co-users (n=182) |

Cannabis-only users (n=250) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 32.9 (10.25) | 34.3 (9.8) | 31.9 (10.5) | 0.015 |

| Gender n (%) | ||||

| Male | 170 (39.4) | 73 (40.1) | 97 (38.8) | 0.935 |

| Female | 260 (60.2) | 108 (59.3) | 152 (60.8) | |

| Other | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Race n (%) | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 319 (73.8) | 145 (79.7) | 174 (69.6) | 0.125 |

| Black/African American | 71 (16.4) | 22 (12.1) | 49 (19.6) | |

| More than One Race | 26 (6.0) | 7 (3.8) | 19 (7.6) | |

| Unknown/Other | 16 (3.7) | 8 (4.4) | 8 (3.2) | |

| Ethnicity n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 43 (10.0) | 16 (8.8) | 27 (10.8) | 0.491 |

| Marital Status n (%) | ||||

| Married/Domestic Partnership | 184 (42.6) | 82 (45.1) | 102 (40.8) | 0.077 |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 52 (12.0) | 30 (16.5) | 22 (8.8) | |

| Never been married | 196 (45.4) | 70 (38.5) | 126 (50.4) | |

| Employment n (%) | ||||

| Employed Full Time | 228 (52.8) | 106 (58.2) | 122 (48.8) | 0.369 |

| Employed Part Time | 82 (19.0) | 29 (15.9) | 53 (21.2) | |

| Student (with NO outside employment) | 28 (6.5) | 10 (5.5) | 18 (7.2) | |

| Unemployed | 33 (7.6) | 14 (7.7) | 19 (7.6) | |

| Retired/Disability/Childcare | 61 (14.1) | 23 (12.6) | 38 (15.2) | |

| Highest Education n (%) | ||||

| Graduated high school or below | 78 (18.1) | 42 (23.1) | 36 (14.4) | 0.104 |

| Part college | 158 (36.6) | 64 (35.2) | 94 (37.6) | |

| Graduated college (2 or 4 year) | 176 (40.7) | 70 (38.5) | 106 (42.4) | |

| Post-Graduate (any) | 20 (4.7) | 6 (3.3) | 14 (5.6) | |

| Annual Household Income n (%)* | ||||

| $19,999 or less | 89 (20.9) | 38 (21.0) | 51 (20.9) | 0.990 |

| $20,000 - $39,999 | 177 (41.6) | 75 (41.4) | 102 (41.8) | |

| $40,000 - $74,999 | 110 (25.9) | 48 (26.5) | 62 (25.4) | |

| $75,000 or more | 49 (11.5) | 20 (11.0) | 29 (11.9) | |

| Cannabis Use Characteristics M (SD) | ||||

| Age of first cannabis use | 16.5 (4.6) | 16.3 (4.8) | 16.6 (4.5) | 0.508 |

| Age of regular cannabis use | 21.0 (6.7) | 20.5 (6.7) | 21.3 (6.6) | 0.207 |

| Years of regular use | 11.9 (9.6) | 13.8 (9.4) | 10.5 (9.5) | 0.001 |

| Smoke cannabis within 30 min. of waking - n (%) | 213 (49.3) | 90 (49.5) | 123 (49.2) | 0.959 |

| CUDIT-R Total | 12.3 (5.73) | 12.1 (5.6) | 12.5 (5.9) | 0.489 |

| # of days with cannabis use in last month | 27.3 (3.62) | 27.5 (3.5) | 27.2 (3.7) | 0.426 |

| # of cannabis uses per day of use | 4.05 (3.51) | 3.9 (3.2) | 4.2 (3.7) | 0.362 |

| Typical grams cannabis in pipe/bowl** | 0.79 (1.3) | 0.80 (1.6) | 0.78 (1.0) | 0.733 |

Note. CUDIT-R= Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test-Revised

Several participants (n=1 cannabis-tobacco co-user and n=6 cannabis only group) reported that they were unsure of their household income. Analysis based on sample of n=425.

Most common method of cannabis use endorsed. Outliers excluded from mean calculation (outliers were values three standard deviations away from the mean).

While demographics of the sample were not statistically compared with population-level regional estimates of the Southeastern US (South Atlantic and East South Central Divisions of the US), overall numbers are described here. Our sample was 73.8% White and 16.4% Black/African American, which varies from population-level Census data from these states (70.0% White and 24.1% Black) (United States Census Bureau, 2017). Our sample also showed an over-representation of women compared to Census data (60% vs. 51%), those identifying as two or more races (6.0% vs. 2.2%) and identifying as Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity (10.0% vs. 8.4%).

Cannabis use characteristics are also shown in Table 1 and generally did not vary between groups, though the years of regular cannabis use was higher for co-users (M=13.78; SD=9.44) than cannabis only users (M=10.54; SD=9.55); t(430)=−3.50, p=.001. The study sample averaged 27.3 days of cannabis use out of the past 30 (SD=3.62), with the majority (n=235; 54%) reporting daily use of cannabis. Though tables of detailed use methods are not included in this report, among never and former tobacco users, 143 (57.2%) reported using blunts and 27 (10.8%) reported using spliffs (joints mixed with tobacco and cannabis) in the past 30 days.

Tobacco use characteristics for co-users only (n=182) are shown in Table 2. About two-thirds of current smokers (n=115; 63.2%) reported smoking at their current rate for 5 years or longer. Current daily smokers averaged using 13.8 cigarettes a day (SD=6.5) while non-daily smokers averaged smoking 15 of the past 30 days (SD=8.9) on which they smoked 4.5 cigarettes on average (SD=4.7).

Table 2.

Tobacco characteristics among the cannabis-tobacco co-using sample (n=182).

| Tobacco Use Characteristics | N(%) |

|---|---|

| Daily smokers | 134 (31.0) |

| Non-daily smokers | 48 (11.1) |

| Quit attempt in past year (yes) | 97 (53.3) |

| Mean(SD) | |

| Cigarettes/day | 11.3 (7.3) |

| Days smoked out of last 30 days (non-daily smokers; n=48) | 15.0 (8.9) |

| Age of first use | 16.3 (3.8) |

| Age or regular use | 18.4 (4.3) |

| Years smoking at current rate | 5.1 (1.4) |

| # of past quit attempts (life-time) | 4.8 (4.6) |

| FIND Total Score | 3.8 (2.6) |

Note. FTND=Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence

3.2. Reasons for Cannabis and Tobacco Co-Use (Aim #2)

Participant responses to survey items asking about reasons for cannabis-tobacco co-use are shown for all items in Table 3. Questions are ordered by item categories (behavioral/use patterns, perceived relatedness, and craving). Generally, most responses on survey items were evenly distributed across response categories. For example, when asked if craving for cigarettes increased when using cannabis (or when high), the sample was evenly distributed across all five response options, indicating varying levels of substance interrelatedness. Some items yielded agreement among the sample. For example, when asked about the perceived relatedness of their co-use, the majority moderately or strongly agreed to the statement “I like to use marijuana and tobacco for different reasons” (n=130; 71.5%) and that their cannabis and tobacco use are completely separate (n=98; 53.9%). Approximately 26% of participants reported that “most” or “all” of their cigarettes were smoked around times that they were using cannabis or were high. Given the distribution of responses across possible options, factor loading and a total score of interrelatedness was pursued through scale validation to provide a continuous measure of the relationship between cannabis and tobacco among this sample.

Table 3.

Responses for survey items regarding reasons for cannabis-tobacco co-use among current co-users (n=182).

| Cannabis-Tobacco Co-use items | Never | Occasionally | Half the time | Often | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral/Use Patterns | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| I use marijuana and tobacco mixed together (in spliffs or blunts). | 109 (59.9) | 57 (31.3) | 6 (3.3) | 8 (4.4) | 2 (1.1) |

| My tobacco/cigarette use increases when I’m using marijuana or I’m high. | 41 (22.5) | 62 (34.1) | 29 (15.9) | 34 (18.7) | 16 (8.8) |

| I smoke a cigarette right after using marijuana (as a chaser). | 25 (13.7) | 39 (21.4) | 22 (12.1) | 47 (25.8) | 49 (26.9) |

| I smoke a cigarette right before using marijuana. | 59 (32.4) | 66 (36.3) | 29 (15.9) | 21 (11.5) | 7 (3.85) |

| Perceived Relatedness | Strongly disagree |

Moderately disagree |

Neutral/No change |

Moderately agree |

Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco use improves my high from marijuana. | 39 (21.4) | 22 (12.1) | 47 (25.8) | 48 (26.4) | 26 (14.3) |

| Tobacco makes me feel more alert when I’m high. | 54 (29.7) | 31 (17.0) | 50 (27.5) | 32 (17.6) | 15 (8.2) |

| When I am using marijuana, or am high, my pleasure (or satisfaction) from smoking cigarettes is increased. | 19 (10.4) | 24 (13.2) | 43 (23.6) | 61 (33.5) | 35 (19.2) |

| When I am smoking cigarettes, my pleasure (or satisfaction) from using marijuana is increased. | 33 (18.1) | 24 (13.2) | 52 (28.6) | 43 (23.6) | 30 (16.5) |

| I like to use marijuana and tobacco for different reasons. | 13 (7.1) | 6 (3.3) | 33 (18.1) | 68 (37.4) | 62 (34.1) |

| My marijuana and tobacco use are completely separate. | 15 (8.2) | 31 (17.0) | 38 (20.9) | 44 (24.2) | 54 (29.7) |

| Craving | Strongly disagree |

Moderately disagree |

Neutral/No change |

Moderately agree |

Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| When I am using marijuana, or am high, my cravings for cigarettes is greater. | 33 (18.1) | 35 (19.2) | 40 (22.0) | 46 (25.3) | 28 (15.4) |

| When I am smoking cigarettes, my cravings for marijuana is greater. | 62 (34.1) | 41 (22.5) | 49 (26.9) | 14 (7.7) | 16 (8.8) |

3.3. Cannabis and Tobacco Interrelatedness (Aim #3)

Details on construct validation can be found in the Appendix materials. Of the initial 12 items presented in Table 3, two items had low correlations with other items were removed from consideration, while two additional items did not load onto any other factors and were similarly excluded. This resulted in an 8-item scale of cannabis-tobacco relatedness that yielded a total score ranging from 8-40 (indicating low to high substance relatedness). The mean total relatedness score was 23.4 (SD=7.8) with a median score of 23, consistent with a normal distribution.

A median split was used to divide the sample of cannabis-tobacco co-users into high (greater than 23) and low relatedness (less than or equal to 23) for descriptive purposes. High interrelatedness of cannabis-tobacco use was not related to gender, race, marital status, education, income, or types of marijuana products used, though, there was a trend for more spliff use among those with high interrelatedness (Chi-square=3.2, p=0.07). The high cannabis-tobacco interrelatedness group smoked more cigarettes per day (M= 13.2 vs. 9.7; t=−3.29, df=180, p<0.01) and were more nicotine dependent as measured by the FTND (M=4.4 vs. 3.3; t=−2.9, df=180, p<0.01) than the low interrelatedness group. There was no difference between high and low interrelatedness in terms of age of first tobacco use, age of first cannabis use, typical percentage of Δ9-tetrahydrocannnabinol (THC) in cannabis purchases, and CUDIT-R scores.

Bivariate correlations between the interrelatedness measure and other cannabis and tobacco use variables are shown in Table 4. In a multivariate linear regression model, age, gender, racial minority status, ethnicity, marital status, education, employment/student status, income, average number of cannabis use episodes per using day, average cigarettes per day, age of first cannabis use, and age of first cigarette use were examined as predictors of total interrelatedness. Only number of cigarettes per day was predictive of interrelatedness, with individuals who smoked more cigarettes per day reporting greater interrelatedness between their cannabis and tobacco use (b=0.21, p=0.02).

Table 4:

Correlation Coefficients (r) for the total cannabis-tobacco interrelatedness score and related demographic, cannabis, and tobacco measures among the co-using sub-sample (n=182).

| Measure |

Correlation Coefficient

(r) |

|---|---|

| Current Age | −0.08 |

| Age of First Tobacco Use | <0.01 |

| Age of First Cannabis Use | −0.12 |

| FTND Total Score | 0.16* |

| Cigarettes Per Day | 0.21* |

| CUDIT-R Total Score | 0.13 |

| Cannabis Use Episodes Per Using Day | 0.11 |

| Estimated % THC in Typical Cannabis Purchase | 0.13 |

Note. Associations are Pearson correlations.

p<0.05.

FTND= Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, CUDIT-R=Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test – Revised; THC= Δ9-tetrahydrocannnabinol.

4. Discussion

This study assessed a sample of adults across the Southeastern US who were current co-users of cannabis and tobacco regarding their patterns and reasons for co-use. This study found that co-users were generally similar to cannabis-only users, except that co-users tended to be older and had been using cannabis regularly for longer despite no difference in age of first cannabis use. Patterns and reasons for co-use were mostly distributed evenly across response options on the majority of co-use questions. For example, among this sample, more than half of co-users endorsed smoking a cigarette after using cannabis (tobacco serving as a chaser), while 35% of the sample did not report engaging regularly in this behavior. This result may speak to a possible mechanism through which nicotine enhances the effects of cannabis for some, but not all users.

In this sample, rates of simultaneous cannabis-tobacco co-use through spliffs was low (12% overall; 13% in tobacco co-users and 10% in cannabis-only users), suggesting that most co-use patterns conform to dual, but independent use, rather than simultaneous use in the same preparations. However, blunt use was prevalent in the sample (60% overall), even among non-tobacco users (57%), which exposes users to varying levels of nicotine depending on the cigar shell being used (Peters, Schauer, Rosenberry, & Pickworth, 2016). This is an important public health concern, especially when considering blunt use in youth who may not otherwise use tobacco/nicotine products.

Finally, in this sample, higher interrelatedness of cannabis and tobacco was associated with greater nicotine dependence scores and more cigarettes per day. In multivariate models, cigarettes per day significantly predicted higher interrelatedness scores. This preliminary result could be due to more instances of cigarette smoking throughout the day and hence, more opportunities for tobacco and cannabis use to occur close in time. Co-users who are heavier cigarette smokers may cluster more of their cigarettes around cannabis use episodes. Another possibility is that the relatedness of substances is driving more tobacco use through enhanced subjective effects. However, more than half of participants reported that they use cannabis and tobacco for different reasons and that their cannabis and tobacco use are completely separate. These potential individual differences and variability surrounding the relatedness of tobacco and cannabis co-use are important when considering treatment strategies for co-users and are worthy of further investigation. Treatment strategies may even consider personalized or tailored strategies depending on relatedness profiles. If substances are highly interrelated, attempts to decrease one substance may fail if use of the other substance is not addressed. In contrast, if unrelated, an individual who is not ready to quit one substance may still have success quitting or reducing use of the other.

Several potential mechanisms have been proposed to explain cannabis and tobacco co-use (Rabin & George, 2015). For example, while THC and nicotine activate receptors concentrated in different areas of the brain, one study found that adding tobacco to cannabis enhanced the rewarding effects of cannabis (Penetar et al., 2005), though this finding was not supported by a similar study (Haney et al., 2013). Another theory posits that co-use of cannabis and tobacco may serve to mitigate discomfort from withdrawal symptoms of the other substance (Balerio, Aso, Berrendero, Murtra, & Maldonado, 2004; Levin et al., 2010). There is little consensus on the reasons for co-use and the preliminary data from this study suggest that the reasons may vary across individuals, patterns of use, and severity of use.

Other studies have explored reasons for co-use and have validated scales for assessing aspects of co-use among young adults (18-25 year olds) (Berg et al., 2018; Ramo et al., 2013). The interrelatedness construct in this study was operationally similar to the Instrumentality subscale of the recent Reasons for Marijuana-Tobacco Co-Use scale, which captures the synergistic drug effects and enhanced effects resulting from co-use, e.g., “Using tobacco increases my buzz from marijuana,” though none of the sub-scales gather specific details on sequential co-use (Berg et al., 2018). Of the four sub-scales developed in this study, Instrumentality sub-scores held the highest correlations with nicotine dependence. This finding implies that substance interrelatedness of co-use is more predictive of nicotine dependence than other possible factors, such as social context, or experimentation. This may also be true for adults who presumably have passed the experimentation stage, have a longer history with these substances, and have more entrenched patterns of use. The nicotine and marijuana interaction expectancy scale (NAMIE) (Ramo et al., 2013) was also validated among young adults and while sub-scales were also relevant to the questions being asked regarding co-use in the current study, we wanted to capture additional items of potential importance. The goal of the current study was not to validate a new instrument, and future work should be devoted to extending these validated assessments to more experienced users and adult co-users and potentially expanding the constructs that are assessed for co-use.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several noteworthy limitations. First, the recruitment source is a limitation to study findings. While the use of MTurk to recruit study participants has the advantage of anonymity, increasing accessibility, targeting a clinical sample not necessarily engaged in treatment, and gathering data quickly, it also has several disadvantages (Buhrmester et al., 2018). The population recruited from MTurk is a convenience sample and may not represent the clinical population of cannabis-tobacco co-users. For example, there is a higher prevalence of cannabis use and CUD among men compared to women in the US (Hasin et al., 2015), but the current study sample over-represented female cannabis users (60% of the total sample). Additionally, one study found lower rates of cigarette smoking endorsement among MTurk workers when compared to a community sample (Walters et al., 2018), which limits the generalizability of smoking behaviors reported on in this study. While demographics of the sample were not statistically compared with population-level regional estimates, our rates suggest that our sample over- and under-represented some key demographic groups (gender, race, ethnicity representation), which is a limit to the generalizability of study findings. Second, this study analyzed data from a small sample of cannabis-tobacco co-users (n=182), which limits power and the ability to detect meaningful differences between groups, as well as the ability to draw firm conclusions about the reasons for co-use among this sample. As such, results from this study are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and limits to generalizability. Third, cannabis-tobacco co-use rates among cannabis users in the current study did not appear to be as high as national averages suggest, even in the Southeastern US; 42.1% in this study vs. 69-78% nationally (Schauer, Berg, et al., 2016). However, the observed rate in the current study more closely approximates the observed rate in a prior multisite clinical trial for CUD (38%; McClure et al., 2018). It may be the case that those who participate in research studies, even via online recruitment sources, are different from those in the general population (i.e., those who complete household surveys; McClure et al., 2017; Susukida, Crum, Stuart, Ebnesajjad, & Mojtabai, 2016), which may have impacted prevalence rates and the characteristics of the current sample of co-users. Finally, all data in this study were self-reported, which does not allow for the biochemical confirmation of cannabis and tobacco co-use.

4.2. Conclusions

Preliminary data from the current study suggest that cannabis-tobacco co-users may vary in the degree to which their substance use is related. These differences may be relevant to treatment as tailored/personalized strategies could be implemented for tobacco or cannabis cessation (or both) based on levels of interrelatedness. Given that cannabis-tobacco co-use is prevalent in the US (Pacek et al., 2018; Schauer, Berg, et al., 2016) and globally (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2017), it is important to develop interventions for the co-use of both substances, as well as determining which co-users will have more difficulty in achieving cessation from one substance if they are not attempting to quit both. There are few interventions for cannabis-tobacco co-use (Becker, Haug, Sullivan, & Schaub, 2014; Beckham et al., 2018; Hill et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014) and it may be beneficial for future treatment development to take into account the relationship and the relatedness between cannabis and tobacco, which can be better understood by assessing the reasons for co-use within an individual.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Reasons for tobacco-cannabis co-use in adults are not well understood.

Co-users were older and had used cannabis longer, compared to cannabis only users.

Reasons for co-use varied widely across the study sample.

Higher temporally related co-use was associated with more severe tobacco use.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance in study development, survey administration, MTurk expertise, data collection and cleaning: Matthew Carpenter, Justin Strickland, Kelly Dunn, Zachary Rosenberry, Erica Peters, Kennede Duncan, Daniel Onyekwere, Kayla McAvoy, Jade Tuttle, and Breanna Tuck.

Funding

Funding to support this study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN) Southern Consortium Node (UG1 DA 013727). Effort was supported by the following grants: NIDA K01 DA036739 (PI: McClure), NIAAA K23AA025399 (PI: Squeglia), NIDA R01 DA 042114 (PI: Gray) and U01 DA031779 (PI: Gray). Survey administration and data collection was possible through REDCap, which is provided and maintained by the Biomedical Informatics Center (BMIC) grant support at MUSC (NIH/NCATS UL1 TR001450).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

References

- Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, & Sellman JD (2010). An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 110(1–2), 137–143. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Chaiton M, & Schwartz R (2015). Development of measures assessing attitudes toward contraband tobacco among a web-based sample of smokers. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 13(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12971-015-0032-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Budney AJ, & Lynskey MT (2012). The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: A review. Addiction, 107(7), 1221–1233. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, & Lynskey MT (2009). Tobacco and cannabis co-occurrence: Does route of administration matter? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 99(1–3), 240–247. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Pergadia ML, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Martin NG, & Madden PAF (2008). Early cannabis use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence: A twin study. Addiction, 103(11), 1896–1904. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02354.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, & Lynskey MT (2008). Transitions to regular smoking and to nicotine dependence in women using cannabis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95(1–2), 107–114. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balerio GN, Aso E, Berrendero F, Murtra P, & Maldonado R (2004). Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Decrease Somatic and Motivational Manifestations of Nicotine Withdrawal in Mice. European Journal of Neuroscience, 20(10), 2737–2748. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03714.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J, Haug S, Sullivan R, & Schaub MP (2014). Effectiveness of different web-based interventions to prepare co-smokers of cigarettes and cannabis for double cessation: A three-arm randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(12), 1–26. 10.2196/jmir.3246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Adkisson KA, Hertzberg J, Kimbrel NA, Budney AJ, Stephens RS, … Calhoun PS (2018). Mobile contingency management as an adjunctive treatment for co-morbid cannabis use disorder and cigarette smoking. Addictive Behaviors, 79(November 2017), 86–92. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Payne J, Henriksen L, Cavazos-Rehg P, Getachew B, Schauer GL, & Haardörfer R (2018). Reasons for Marijuana and Tobacco Co-use Among Young Adults: A Mixed Methods Scale Development Study. Substance Use and Misuse, 53(3), 357–369. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1327978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky JT, Crosier BS, Lee DC, Sargent JD, & Budney AJ (2016). Smoking, vaping, eating: Is legalization impacting the way people use cannabis? International Journal for Drug Policy, 4(1), 141–147. 10.1038/nmeth.2839.A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester MD, Talaifar S, & Gosling SD (2018). An Evaluation of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, Its Rapid Rise, and Its Effective Use. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 149–154. 10.1177/1745691617706516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2015). Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (HHS Pulication No. SMA 15–4927, NSDUH Series H–50., 64 Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf%5Cnhttp://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. SAMHSA, 170, 51–58. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, & Hughes A (2016). Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002–14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(10), 954–964. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30208-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Nahhas RW, Wijeratne S, Carlson RG, Lamy FR, Martins SS, … Sheth A (2015). “Time for dabs”: Analyzing Twitter data on marijuana concentrates across the U.S. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 155, 307–311. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). (2017). European Drug Report 2017: Trends and Developments. Publication Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2017 10.2810/610791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney KE, & Kampman KM (2016). Adverse effects of marijuana use. The Linacre Quarterly, 83(2), 174–178. 10.1080/00243639.2016.1175707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Pacek LR, Copeland J, Moeller SJ, Dierker L, Weinberger A, … Hasin DS (2018). Trends in daily cannabis use among cigarette smokers: United States, 2002–2014. American Journal of Public Health, 108(1), 137–142. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray KM, Sonne SC, McClure EA, Ghitza UE, Matthews AG, McRae-Clark AL, … Levin FR (2017). A randomized placebo-controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine for cannabis use disorder in adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177(April), 249–257. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Bedi G, Cooper ZD, Glass A, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, & Foltin RW (2013). Predictors of marijuana relapse in the human laboratory: Robust impact of tobacco cigarette smoking status. Biological Psychiatry, 73(3), 242–248. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Kerridge BT, Saha TD, Huang B, Pickering R, Smith SM, … Grant BF (2016). Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, 2012-2013: Findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(6), 588–599. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15070907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, … Grant BF (2015). Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1235–1242. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, & Fagerstrom KO (1991). The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KP, Toto LH, Lukas SE, Weiss RD, Trksak GH, Rodolico JM, & Greenfield SF (2013). Cognitive behavioral therapy and the nicotine transdermal patch for dual nicotine and cannabis dependence: A pilot study. American Journal on Addictions, 22(3), 233–238. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.12007.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindocha C, Freeman TP, Ferris JA, Lynskey MT, & Winstock AR (2016). No smoke without tobacco: A global overview of cannabis and tobacco routes of administration and their association with intention to quit. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7(JUL), 1–9. 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2017). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Retrieved from https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/142406/Overview 2017 FINAL.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, Singh N, Camenga D, Cavallo D, & Krishnan-Sarin S (2013). Menthol cigarette and marijuana use among adolescents. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 15(12), 2094–2099. 10.1093/ntr/ntt102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamy FR, Daniulaityte R, Sheth A, Nahhas RW, Martins SS, Boyer EW, & Carlson RG (2016). “Those edibles hit hard”: Exploration of Twitter data on cannabis edibles in the U.S. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 164, 64–70. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale ST, Ahmed R, & Kaiserman M (2006). Marijuana use by tobacco smokers and nonsmokers: who is smoking what? Cannabis Medical Association Journal, 174(10), 1399 10.1503/cmaj.051614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale ST, Hammond DG, Kaiserman M, & Ahmed R (2007). Marijuana and tobacco use among young adults in Canada: Are they smoking what we think they are smoking? Cancer Causes and Control, 18(4), 391–397. 10.1007/s10552-006-0103-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Budney AJ, Brunette MF, Hughes JR, Etter JF, & Stanger C (2014). Treatment models for targeting tobacco use during treatment for cannabis use disorder: Case series. Addictive Behaviors, 39(8), 1224–1230. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin KH, Copersino ML, Heishman SJ, Liu F, Kelly DL, Boggs DL, & Gorelick DA (2010). Cannabis withdrawal symptoms in non-treatment-seeking adult cannabis smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 111(1–2), 120–127. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, Baker NL, & Gray KM (2014). Cigarette smoking during an N-acetylcysteine-assisted cannabis cessation trial in adolescents. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(4), 285–291. 10.3109/00952990.2013.878718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, Baker NL, Sonne SC, Ghitza UE, Tomko RL, Montgomery L, … Gray KM (2018). Tobacco use during cannabis cessation: Use patterns and impact on abstinence in a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 192(March), 59–66. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, King JS, Wahle A, Matthews AG, Sonne SC, Lofwall MR, … Gray KM (2017). Comparing adult cannabis treatment-seekers enrolled in a clinical trial with national samples of cannabis users in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 176(February), 14–20. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCredie MN, & Morey LC (2018). Who Are the Turkers? A Characterization of MTurk Workers Using the Personality Assessment Inventory. Assessment, 107319111876070 10.1177/1073191118760709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier E, & Hatsukami DK (2016). A review of the additive health risk of cannabis and tobacco co-use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 166, 6–12. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, & Budney AJ (2001). Tobacco smoking in marijuana-dependent outpatients. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(4), 583–596. 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00093-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KH, Marshall L, Brown S, & Neff L (2016). State-Specific Prevalence of Current Cigarette Smoking and Smokeless Tobacco Use Among Adults — United States , 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(39). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoli CTC, Richardson CG, Ratner PA, & Johnson JL (2008). Adolescents’ self-defined tobacco use status, marijuana use, and tobacco dependence. Addictive Behaviors, 33(11), 1491–1499. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek LR, Copeland J, Dierker L, Cunningham CO, Martins SS, & Goodwin RD (2018). Among whom is cigarette smoking declining in the United States? The impact of cannabis use status, 2002–2015. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191(September 2017), 355–360. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek LR, Mauro PM, & Martins SS (2015). Perceived risk of regular cannabis use in the United States from 2002 to 2012: Differences by sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 149, 232–244. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penetar DM, Kouri EM, Gross MM, McCarthy EM, Rhee CK, Peters EN, & Lukas SE (2005). Transdermal nicotine alters some of marihuana’s effects in male and female volunteers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 79(2), 211–223. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Rosenberry ZR, Schauer GL, O’Grady KE, & Johnson PS (2017). Marijuana and tobacco cigarettes: Estimating their behavioral economic relationship using purchasing tasks. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(3), 208–215. 10.1037/pha0000122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Schauer GL, Rosenberry ZR, & Pickworth WB (2016). Does marijuana “blunt” smoking contribute to nicotine exposure?: Preliminary product testing of nicotine content in wrappers of cigars commonly used for blunt smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 168, 119–122. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Schwartz RP, Wang S, O’Grady KE, & Blanco C (2014). Psychiatric, psychosocial, and physical health correlates of co-occurring cannabis use disorders and nicotine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 134(1), 228–234. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin RA, & George TP (2015). A review of co-morbid tobacco and cannabis use disorders: Possible mechanisms to explain high rates of co-use. American Journal on Addictions, 24(2), 105–116. 10.1111/ajad.12186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Liu H, & Prochaska JJ (2012). Tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of their co-use. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(2), 105–121. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Liu H, & Prochaska JJ (2013). Validity and reliability of the nicotine and marijuana interaction expectancy (NAMIE) questionnaire. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131(1–3), 166–170. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rass O, Pacek LR, Johnson PS, & Johnson MW (2015). Characterizing use patterns and perceptions of relative harm in dual users of electronic and tobacco cigarettes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23(6), 494–503. 10.1037/pha0000050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Kaur H, Resnicow K, Nazir N, Mosier MC, & Ahluwalia JS (2004). Cigarette Smoking Among Marijuana Users in the United States Cigarette Smoking Among Marijuana Users in the United States. Substance Abuse, 25(2), 35–43. 10.1300/J465v25n02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, Donovan DM, & Windle M (2016). Differences in tobacco product use among past month adult marijuana users and nonusers: Findings From the 2003–2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 18(3), 281–288. 10.1093/ntr/ntv093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Hall CD, Berg CJ, Donovan DM, Windle M, & Kegler MC (2016). Differences in the relationship of marijuana and tobacco by frequency of use: A qualitative study with adults aged 18–34 years. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(3), 406–414. 10.1037/adb0000172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, & Peters EN (2018). Correlates and trends in youth co-use of marijuana and tobacco in the United States, 2005–2014. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 185(May 2017), 238–244. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Peters EN, Rosenberry Z, & Kim H (2017). Trends in and characteristics of marijuana and menthol cigarette use among current cigarette smokers, 2005–2014. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 20(3), 362–369. 10.1093/ntr/ntw394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, & Stoops WW (2015). Perceptions of research risk and undue influence: Implications for ethics of research conducted with cocaine users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 156, 304–310. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, & Stoops WW (2018). Feasibility, acceptability, and validity of crowdsourcing for collecting longitudinal alcohol use data. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 110(1), 136–153. 10.1002/jeab.445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susukida R, Crum RM, Stuart EA, Ebnesajjad C, & Mojtabai R (2016). Assessing sample representativeness in randomized controlled trials: application to the National Institute of Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network. Addiction, 111(7), 1226–1234. 10.1111/add.13327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullis LM, DuPont R, Frost-Pineda K, & Gold MS (2003). Marijuana and Tobacco: A Major Connection? Journal of Addictive Diseases, 22(3), 79–87. 10.1300/J069v22n03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, & Weiss SRB (2014). Adverse Health Effects of Marijuana Use. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(23), 2219–2227. 10.1056/NEJMra1402309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K, Christakis DA, & Wright DR (2018). Are Mechanical Turk worker samples representative of health status and health behaviors in the U.S.? PLoS ONE, 13(6), 1–10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JB, Ramo DE, Lisha NE, & Cataldo JK (2016). Medical marijuana legalization and cigarette and marijuana co-use in adolescents and adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 166(2016), 32–38. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.