Abstract

Currently, 2.2 million individuals are incarcerated and more than 11 million have been released from U.S. correctional facilities. Individuals with a history of incarceration are more likely to be of racial and ethnic minority populations, poor, and have higher rates of cardiovascular risk factors, especially smoking and hypertension. Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death among individuals incarcerated, and those recently released have a higher risk of being hospitalized and dying of cardiovascular disease compared with the general population, even after accounting for differences in racial identity and socioeconomic status. In this review, we: 1) present information on the cardiovascular health of justice-involved populations, and unique prevention and care conditions in correctional facilities; 2) identify knowledge gaps; and 3) propose promising areas for research to improve the cardiovascular health of this population. An Executive Summary of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop on this topic is available.

Keywords: correctional health care, epidemiology, jails, National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute, prisons, risk factors

CONDENSED ABSTRACT:

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death among the 2.2 million individuals incarcerated in correctional facilities. Those recently released from correctional facilities have a higher risk of being hospitalized and dying of CVD compared with the general population, even after accounting for differences in racial identity and socioeconomic status. This review: 1) presents existing information on the cardiovascular health of justice-involved populations and the unique conditions of prevention and care in correctional facilities; 2) identifies knowledge gaps; and 3) proposes promising areas for research to improve the cardiovascular health of this population.

THE U.S. CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM AND MASS INCARCERATION

The United States leads the world in the number of individuals under correctional supervision (1). Although the causes of mass incarceration are complex, criminal justice policies such as mandatory minimum sentencing and the “war on drugs” catalyzed and sustained high rates of incarceration over the past 3 decades (2). At the end of 2015, almost 2.2 million individuals were in jails (facilities that typically house those who are awaiting adjudication or serving sentences of <1 year) and prisons (which house those who have been sentenced to more than 1 year), and over 4.5 million individuals were under community correctional supervision in probation, parole, and jail diversion programs (3). In 2015, an estimated 10.9 million individuals cycled through jails, and 641,000 individuals were released from state and federal prisons (4,5).

Individuals of racial and ethnic minority groups, and low income status have been disproportionately incarcerated. For instance, when compared with whites, black arrest rates are 2.5 times higher; incarceration rates are 6 and 5 times higher for state prisons and jails, respectively; probation rates are 3 times higher; and parole rates are 5 times higher (6). Using rates of incarceration from 2001, black men have a 1 in 3 lifetime risk of being incarcerated and Latino men have a 1 in 6 lifetime risk of incarceration (7). Although most individuals involved in the criminal justice system are men, women now comprise a larger proportion of the incarcerated population than before. Between 1980 and 2015, the number of incarcerated women increased by more than 700%, rising from a total of 26,378 in 1980 to 111,495 in 2015 (8).

In 1976, the Supreme Court ruled in Estelle v. Gamble (9) that it was “cruel and unusual punishment” not to provide basic health care in correctional facilities, thus establishing provision of health care to incarcerated persons as a constitutional right. Subsequent court rulings further clarified this ruling by requiring prisons and jails to provide “adequate [health] services: services at a level reasonably commensurate with modern medical science and of a quality acceptable within prudent professional standards” (10). Collectively, these court rulings have reinforced the broad meaning of serious medical need or injury to encompass medical care for chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease (CVD). How these rulings are applied in practice influences both the prevention and treatment of CVD, and varies by state and even facility.

Unlike almost all other settings in which health care is delivered, the primary mission of the correctional setting is not medical care or public health, but rather public safety. As such, although provision of health care is usually viewed as required, it is not the priority. Correctional health care in the United States is delivered via 1 of 5 different models. A significant proportion of care is delivered via contract between the correctional administrator and a for-profit health care vendor, with private companies having contracts for approximately one-third of all correctional health care spending (11). These contracts may be for all or some components (e.g., physician services) of health care delivery. Most of the remaining facilities operate health care themselves (i.e., health care staff are government employees). In a small number of facilities, health care is provided through an agreement with a public health authority or a public university. As of 2014, 22 states had privatized correctional health care and 7 were partially privatized (11,12). Health care needs are significantly influenced by the increasingly older age of incarcerated individuals. The number of incarcerated individuals 55 years of age or older has nearly quadrupled in the past 20 years (13). In 2010, 124,400 prisoners were 55 years of age or older.

CVD has been among the top causes of death among jail inmates and state prisoners (14), and is a common cause of death immediately following release from correctional facilities. Published reports suggest that there is an association between having a history of incarceration and cardiovascular risk factors, morbidity, and mortality from CVD (15–17). But drawing inferences regarding the causal effects of incarceration is itself limited by the presence of multiple confounders, including life course and other social factors associated with being incarcerated. The identification of the health effects of incarceration is also rendered complex by large heterogeneity in what it means to be incarcerated, ranging from a brief stay of a few hours or days in jail to life-long sentences in prison. Moreover, different types of incarceration are governed and/or financed by different sectors (i.e., municipal, county, state, federal, or private corporations) (18–21), which presents challenges for health care, research, and policy implementation.

In this review, we will: 1) present the existing research on the cardiovascular health of justice-involved populations, which we define as those currently incarcerated and those with a previous history of incarceration; 2) identify current gaps in knowledge; and 3) propose promising areas for research to improve the cardiovascular health of this population.

CVD RISK AMONG JUSTICE-INVOLVED POPULATIONS

Existing evidence suggest that justice-involved populations have average to high CVD risk compared with community dwellers. Self-reported data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) suggest that state and federal prisoners, and jail inmates have increased rates of CVD risk factors compared with demographically-matched individuals living in the community, especially hypertension and smoking, even after adjusting for known confounders (Table 1) (22). About 1 in 10 state and federal prisoners and jail inmates reported ever being told by a doctor, nurse, or health care provider that they had a heart-related problem (22). Among prisoners with a current heart-related problem, 40% were taking prescription medication, whereas 16% reported receiving other medical treatment. Consistent with findings in the general population, most prison (74%) and jail inmates (62%) were overweight, obese, or morbidly obese. These comparisons, however, should be interpreted with caution. Unlike in the community, health care is constitutionally guaranteed in prison, and thus disease ascertainment may be more effective there. For example, according to a BJS survey conducted in 2011, CVD risk factor screening upon admission is common among state prison systems (Table 2), with some states reporting that they tested all inmates, whereas others tested on the basis of medical history, clinical indication, or some other criteria (23). Thus, risk factor or disease prevalence in the community may be under-ascertained when compared to prison prevalence (“detection bias”).

Table 1.

Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–12 (22)*

| Condition | State/Federal Prisoners % | Jail Inmates % | U.S. Population % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 30.2 | 26.3 | 18.1 |

| Heart-related problems | 9.8 | 10.4 | 2.9 |

| Diabetes | 9.0 | 7.2 | 6.5 |

| Asthma | 14.9 | 20.1 | 10.2 |

| Kidney-related problems | 6.1 | 6.7 | N/A |

| Stroke | 1.8 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| Overweight/obese | 73.6 | 61.6 | N/A |

| Any chronic condition | 43.9 | 44.7 | 31.0 |

On the basis of data from the National Inmate Survey 2011–2012 (NIS-3), a survey of 3,833 randomly-selected state prisoners and 5,494 jail inmates. General population estimates are from a community-based survey, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2009–2012.

N/A = not available.

Table 2.

CVD Screening, Treatment, and Evaluation Services in State Prisons (23)*

| Service Provided | Number of States That Endorsed Providing Service |

|---|---|

| CVD risk factor screening upon admission | |

| Lipids | 30 |

| Blood pressure measurement | 44 |

| Electrocardiogram | 29 |

| All 3 tests | 23 |

| Cardiology specialty referral | |

| On-site | 25 |

| Off-site | 2 |

| Both | 17 |

| Cardiac catheterization, off-site | 44 |

On the basis of data from the National Survey of Prison Health Care (NSPHC) for calendar year 2011 from respondents from all 45 participating states.

CVD = cardiovascular disease.

Constitutionally-protected access to health care for state and federal prisoners and jail inmates may allow early detection and treatment and perhaps better management of CVD risk factors. Even though 80% of incarcerated individuals report seeing a physician at least once (24), there are unique barriers to seeing a health care provider while incarcerated, including patients paying a copay to be seen (25), security concerns, and lack of providers (26). The consistency and quality of CVD care across correctional health care settings varies, and is potentially challenged for a number of reasons (27): 1) funding health care services (i.e., infrastructure, staffing, and equipment) for incarcerated individuals may not be the highest priority for the public, elected officials, and private corporations, and is further limited by government budgets or profit-making; 2) many correctional authorities lack the expertise to properly oversee health care operations under their jurisdiction; and 3) many health care professionals do not view practicing in a jail or prison as a desirable setting; thus, it can be difficult to attract qualified providers (28).

Furthermore, there is no national and limited regional quality control via mandated regulation or oversight. A large portion of quality control in community-based health care is driven by insurers (e.g., Medicaid and Medicare driving the requirement for Joint Commission accreditation of hospitals; private insurers monitoring delivery of ambulatory care). However, no in-prison health care is covered by Medicaid/Medicare, and only an estimated <1% of care (for some pre-trial detainees in jail) is covered by other insurance, so these potential drivers of quality control are missing. Some jails and prisons voluntarily obtain accreditation from national correctional bodies, such as the National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC); however, the majority has not been accredited.

Studies that have clinically measured the presence of CVD risk factors reveal heterogeneity, even within a single state system (29) or within a single institution (30–32), but mostly confirm the findings of self-reported surveys and find that incarcerated individuals have high CVD risk factors. However, 1 study in South Dakota did not find differences in systolic or diastolic blood pressures or body mass index between incarcerated and nonincarcerated women, but did find that those never incarcerated had lower mean total cholesterol compared with women who were incarcerated (33).

In contrast, there are no population-level studies of CVD and its risk factors among individuals who have been released from state and federal prisons or jails. Most national household-based surveys do not include questions on recent incarceration exposure. However, studies from 2 large prospective cohort studies that did include questions related to incarceration history indicate that individuals who have recent contact with the criminal justice system have higher rates of hypertension and uncontrolled blood pressure (15,16). Furthermore, individuals recently released from correctional facilities have a higher risk of hospitalization and, in some studies, an increased risk for mortality due to CVD and its risk factors compared with the general population (17,34). With such limited studies, differences in the impact of incarceration on CVD risk by racial and ethnic background or sex have not been sufficiently explored among the incarcerated or community-dwelling individuals with a history of incarceration. The impact of incarceration on women is particularly difficult to study, given their lower rates of incarceration compared with men.

CURRENT GAPS IN KNOWLEDGE

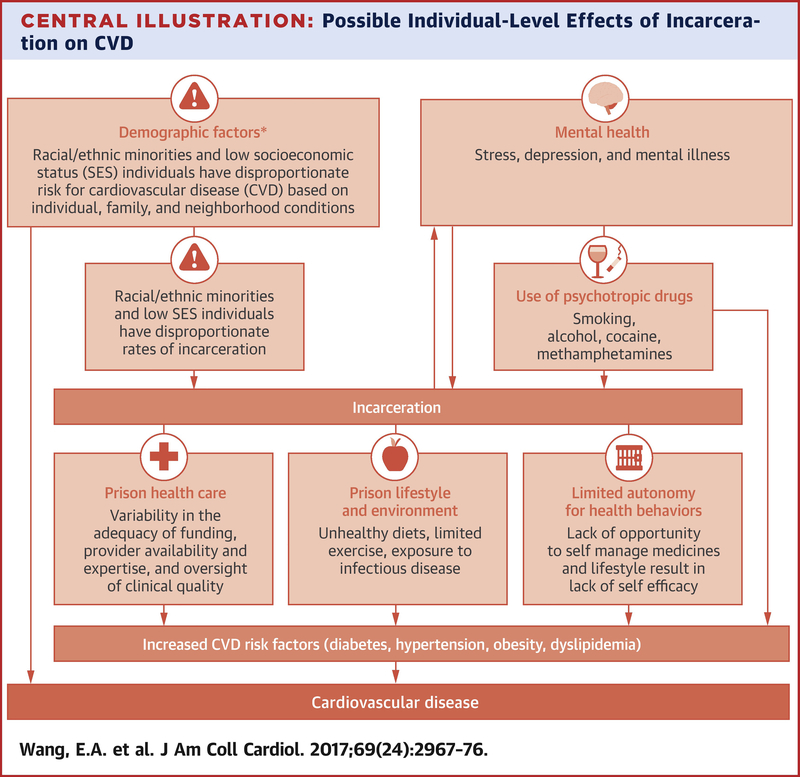

Incarceration can encompass a heterogeneous set of conditions (different security levels and concomitant access to health-related goods and services, solitary confinement, among others). Nonetheless, there are several potential mechanisms that may explain the relationship of incarceration with a high risk of CVD (Central Illustration). One mechanism by which incarceration may be associated with elevated CVD risk is that social groups with high CVD risk (such as populations of lower socioeconomic position or racial/ethnic minorities) are overrepresented in the incarcerated population. In other words, the same life course and social context factors that are associated with being incarcerated are also linked to the presence of many CVD risk factors (35–36). Studies that have explored the association between incarceration and CVD risk factors, and have adjusted for race/ethnicity and socioeconomic background, have found that the association persists, suggesting that incarceration may have an independent effect on CVD risk factors. Having been incarcerated may augment socioeconomic disadvantage, which is independently associated with the development of CVD (37,38). Therefore, it is difficult to isolate the effects of criminal justice involvement on CVD from all of the other socioeconomic circumstances with which it is correlated (39).

Central Illustration. Possible Individual-Level Effects of Incarceration on Cardiovascular Disease.

Incarceration may influence cardiovascular disease through multiple pathways. Socioeconomic position, neighborhood and family conditions, and some comorbid conditions (e.g., substance use) also may influence the likelihood of incarceration, and thus a bidirectional relationship is illustrated. *Sociodemographic and neighborhood factors affect behavioral and psychosocial factors, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality, but their relationships were not depicted for the sake of clarity. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

A second potential mechanism is the experience of incarceration as a stressor, which may affect coping behaviors like smoking, or may act directly through depression or stress-related biological processes involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic-parasympathetic systems, which play an important role in the pathophysiology of CVD (40–42). Although researchers speculate that current and former inmates may have dysregulated stress mechanisms leading to increased risk for poor health outcomes (43,44), no studies have examined the association between incarceration and various markers of stress that have been found to be mediators of disparities in CVD (dysfunction of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, increased catecholamines, blood pressure reactivity (45), or physiological responses to chronic stresses, as measured by allostatic load (46)). Those with a history of incarceration may suffer from stress due to social isolation (47), as incarceration also disrupts romantic unions (48), which has also been linked to higher total mortality, independent of cardiovascular risk factors. Finally, sleep disruption (from noise and security checks) and the general stress of being incarcerated may have deleterious effects on cardiovascular health. Stress may also potentiate the effects of other behavioral risk factors, such as poor diet or smoking, in correctional facilities or following release.

Similarly understudied are the prevention and self-management strategies of individuals currently incarcerated—their diet, physical activity, pharmacological adherence behaviors—and how this is affected by the correctional environment and health care system (49). The availability of certain diets (e.g., diabetic, low-fat, or low-sodium), ability to exercise, and management of their own medications are all largely beyond the control of most incarcerated individuals, and may be a contributor to the development of CVD or CVD-related complications (50–53). In most correctional settings, patients do not manage their own medications: they do not pick up their medications at a pharmacy, and usually do not possess or administer their own medications (50,51). They also do not develop the skills to manage complications of chronic medical conditions, including using a glucometer or sleep apnea machine (49). For example, with rare exceptions (54), correctional authorities do not allow patients to possess sharp metallic devices, such as finger stick lancets to measure blood glucose or syringes to deliver insulin; thus, patients cannot easily learn (or continue) to independently manage their disease. Although there are some facilities and circumstances where patients may keep medications in their possession (“keep on person”), in many instances, they are administered by staff (55,56). The limited opportunity for self-management while incarcerated does little to prepare individuals for often-rigorous self-management requirements post-release.

Although current and former inmates’ health beliefs and attitudes about CVD risk factors and disease have not been well studied, a recent qualitative study among individuals released from prison with CVD risk factors highlights how prisons can either facilitate or prevent self-management of CVD risk factors (49). The study showed that the tradeoff between prisoner security and patient autonomy influences opportunities for self-management, and that prison providers’ multiple roles (correctional and medical) could undermine patient-centered care. A study of older inmates also revealed that being incarcerated can facilitate developing skills in managing one’s CVD risk factors; however, these skills may not be translatable to managing one’s disease in the community (57). Research in minority and vulnerable populations has demonstrated that disparate patient adherence to health-supporting behaviors (exercising, eating a healthy diet, taking medications as directed, avoiding illicit substance abuse) is an important component of disparities in CVD outcomes (58,59).

Other clinical comorbidities among patients with a history of incarceration could contribute to increased cardiovascular risk. Substance use (specifically alcohol, cocaine, and methamphetamine use), a known CVD risk factor, is higher among justice-involved populations compared with the general population (60). Individuals involved in the criminal justice system have increased rates of mental health conditions, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and hepatitis C, which are all independently associated with increased risk for developing CVD (61,62). Notably, patients receiving psychotropic medications (e.g., olanzapine) are at increased risk of developing diabetes and, given the high rates of mental illness among the incarcerated, psychotropic medicine use is more common than in the general population. No studies have explored the extent to which these comorbidities or medications explain the increased CVD morbidity and mortality observed in the justice-involved population.

Finally, few studies have explored how institutional or government policies affect CVD risk factor management following release. Individuals being released from correctional facilities face a variety of barriers to health care upon their return to communities. Discharge planning does not fall under the constitutional guarantee for health care, nor does health care post-release. The post-release experience may be associated with changes in CVD risk due to socioeconomic disadvantage resulting from systemic barriers due to having a criminal record. Formerly incarcerated individuals frequently return to the community without financial resources, housing, employment, or family support, which challenges meeting their basic needs, yet are confronted with the competing demands of managing their health problems, obtaining health care, and keeping up with medications or appointments (63). Additionally, many individuals convicted of drug felonies are prohibited from accessing safety net services, including food stamps, public housing, or federal grants for education upon release from prison (64).

Patients with diabetes, hypertension, or CVD are often released without medications or a follow-up appointment in the community (47). Even when provided with prescriptions for medications or appointments upon release, many do not obtain them due to costs. In 1 study, from 2000, before the passing of the Affordable Care Act, 90% of individuals released from jail were uninsured or lacked financial resources to pay for their medical care (65). Recently-released inmates are less likely to have a primary care physician and disproportionately use the emergency department for health care compared with the general population. Health insurance benefits, particularly Medicaid, may be terminated or suspended when a person is incarcerated, and a delay in reinstatement upon release often results in a coverage gap, resulting in delayed medical care (66–68). These gaps in resources and care upon re-entry to the community potentially increase one’s vulnerability to increased CVD risk and poor disease management

PROMISING AREAS FOR RESEARCH TO IMPROVE THE CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH OF THIS POPULATION

Given the enormity of the population of individuals with a history of incarceration and the disproportionate incarceration of individuals of racial and ethnic minorities, a critical goal of research remains understanding the CVD burden in incarcerated populations, and how the experience of incarceration and release from correctional facilities affects CVD risk. The exclusion of currently-incarcerated people from household-based sample surveys, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the National Health Interview Survey, prevents understanding of the health of individuals who have criminal justice involvement. A recent workshop at the National Heart Lung Blood Institute (69) identified a number of important strategies for understanding the epidemiology of cardiovascular risk in this population (Table 3). Gathering longitudinal data regarding the prevalence of CVD and risk factors in people exposed to the criminal justice system (e.g., prison, jail, probation, parole, among others), or including incarcerated populations in community-based surveys and interventions, would improve our understanding of the magnitude and etiology of CVD in populations exposed to the criminal justice system. Given the high rates of incarceration in socially disadvantaged groups and racial/ethnic minorities, understanding the magnitude and drivers of CVD risk in this population is critical to understanding health disparities in CVD.

Table 3.

Research Opportunities on CVD Among the Justice-Involved Population

| Research Opportunities | Potential Strategies |

|---|---|

| Understand CVD burden in incarcerated populations, how incarceration affects CVD risk, and how missing the incarcerated population affects research on health disparities. | • Gather longitudinal data regarding prevalence of CVD and risk factors in people exposed to the CJ system (e.g., prison, jail, probation, parole, and so on) in a manner that is identical or similar to how information is collected for other national surveys of health for noninstitutionalized populations (e.g., NHANES) by: 1) building on existing surveys conducted through the BJS, focusing on incarcerated and released prisoners with CVD risk factors; 2) adding survey questions on incarceration history and intensity to existing and future national health survey and epidemiological studies; 3) including incarcerated populations in community-based surveys and interventions (which currently exclude incarcerated populations); 4) developing compatible surveys between the CJ system and general population; 5) establishing new prospective epidemiological studies to understand the magnitude and etiology of CVD in populations exposed to the CJ system (e.g., prison, jail, probation, parole, and so on); 6) incorporating health information technology and common standards in data collection to allow data-sharing for research purposes and for providing continuous care; and 7) studying the impact of incarceration on the health of family members, particularly women, who are bearing most of the responsibility for health care. |

| Investigate the challenges to CVD prevention, diagnosis, and intervention in incarcerated and recently released populations, and develop effective models of CVD prevention, diagnosis, and treatment tailored for incarcerated and released populations. | • Understand the barriers to conducting research in the CJ population, while continuing to ensure that this vulnerable population is adequately protected by: 1) investigating challenges at CJ system and clinical provider levels to improve health service; and 2) engaging stakeholders, including inmates, staff, and administrators of the CJ system and leveraging existing federal investment to build infrastructure (training, resources, network) and share best practices in research; 3) developing resources and networks to facilitate the interaction of CVD investigators with the CJ system; and 4) developing training program for CVD investigators to learn the CJ health care and health data management system. |

| • Develop a research program to evaluate the effect of community-based CVD prevention and reduction strategies on cardiovascular health of incarcerated and recently-released populations, including evaluation of short- and long-term effects, and continuity of care across the transition; and stimulate CVD research with economic measurements (e.g., cost-effectiveness) and public safety aspects in the incarcerated population to demonstrate potential benefits of CVD prevention/intervention for the CJ system. | |

| Understand how transition from CJ system to community affects CVD risk and health disparities, and develop strategies to provide continuous care for the recentlyreleased population. | • Understand the impact of discontinuation of care or change in care model on CVD risk and prevalence, health disparity, and health status of family members. |

| • Identify barriers to transition care and care models that facilitate the transition | |

| • Develop strategic partners (including Housing and Urban Development, Department of Labor, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and so on) to provide social support that may enhance/facilitate care transition. | |

| • Understand how prevention and intervention while incarcerated influence long-term cardiovascular health. |

BJS = Bureau of Justice Statistics; CJ = criminal justice; CVD = cardiovascular disease; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Secondly, the experiences of individuals who are incarcerated and are released from correctional facilities presents unique challenges to the management of cardiovascular risk factors and disease. Therefore, we must develop effective models of CVD prevention, diagnosis, and treatment tailored for incarcerated and released populations. There have been limited numbers of CVD interventions that target state prisoners, and none that we are aware of in jails. In addition, few if any studies have explored the impact of corrections-based interventions on community CVD outcomes. WISEWOMAN (Well-Integrated Screening and Evaluation for Women Across the Nation) was developed by the Centers for Disease Control to address the screening (e.g., overweight or obesity, blood pressure, and cholesterol) and lifestyle intervention needs (e.g., exercise and nutrition education) of middle-aged women who are financially disadvantaged and lack access to health care (33,70). The intervention was adapted for the prison population in South Dakota, where attendance at lifestyle intervention sessions was found to be significantly higher among incarcerated participants than among nonincarcerated participants, but participant follow-up rates were poor, preventing determination of the intervention’s efficacy (33). The National Institute of Nursing Research also funded a bio-behavioral cardiovascular intervention in Kentucky State prisons, which evaluated the impact of health education and an aerobic exercise program on participant exercise tolerance and self-reported health risk assessment, exercise, diet, social support, stress, and tobacco use (29); final results have not yet been published. Future studies should use experimental design to evaluate interventions and prevention strategies that prevent cardiovascular risk factors and disease in correctional settings, including both jails and prisons. Furthermore, there is a need to test strategies to improve communication, coordination, and transitions in care across incarceration settings and upon release, and to measure the impact of these interventions following release from correctional facilities.

Although high-quality research is lacking among justice-involved populations, it is important to note the historical reasons for this. The abuse of inmates in service to research, especially testing of new pharmacological therapies, is well documented, and led, in the 1970s, to significant restrictions in research that includes correctional populations (39). But the prevalence of incarceration and its disproportionate concentration among disadvantaged groups suggests that research that aims to estimate CVD prevalence and etiology and prevent CVD is critical to achieving health equity. In 2003, the Institute of Medicine released a report on the ethics of conducting research on prisoners and proposed changes to current federal regulations, recommending that clinical studies presenting minimal risk and recruiting participants in the community should no longer be required to obtain additional certification from the federal Office of Human Research Protections (71). The loosening of this regulation would facilitate epidemiological studies and clinical research trials of minimal risk to proceed with added regulations.

CONCLUSIONS

Individuals with a history of incarceration have many known risk factors for CVD, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, comorbidities (HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and drug addiction), and stress, in addition to incarceration-specific factors, such as exposure to the prison environment, that may increase the risk of CVD. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of CVD in the incarcerated population are complex, and improvement of cardiovascular health requires individual behavioral modification, as well as correctional health care system changes. A research program that evaluates the effect of CVD prevention and reduction strategies on cardiovascular health of incarcerated and recently-released populations should include evaluation of short-term and long-term effects and continuity of care across the transition from correctional facility to release.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the following additional working group participants for their time and expertise: Mensah, NHLBI; Passman, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; Maruschak, Statistician, Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), Department of Justice (DOJ); Wiley, National Institute on Drug Abuse; Juliano-Bult, National Institute of Mental Health; Alvidrez, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Tabor, NIMHD; Jones, National Institute of Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Salive, National Institutes on Aging; Srinivasan, National Cancer Institute; Carson, Statistician, BJS, DOJ; Khaldun, Baltimore City Health Department; Taxman, George Mason University.

DISCLOSURES: Support for the Working Group was provided by the Division of Cardiovascular Sciences, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. Sorlie, Redmond, and Chen, and Ms. Iturriaga and Ms. Shero are employees of the NIH. Dr. Redmond is a board member of the nonprofit organization Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform, from which she receives no financial support. Dr. Redmond participated in the workshop as an employee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and contributed to this article as an employee of the NHLBI. Dr. Diez Roux served as the Chair of this workshop and received support from 2P60MD002249. Dr. Wang received salary support from the NHLBI (K23 HL103720). Dr. Pettit was supported by the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin, which is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24HD042849), and receives support from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- BJS

Bureau of Justice Statistics

- CJ

criminal justice

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER: Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHLBI or the NIH.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walmsley R World Prison Population List. Eleventh edition. London UK: Institute for Criminal Policy Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pettit B Invisible Men Mass: Incarceration and the Myth of Black Progress. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaeble D, Glaze LE. Correctional populations in the United States, 2015. 2016. Department of Justice Report NCJ 250374. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5870. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 4.Minton TD, Zeng Z. Jail inmates in 2015. 2016. Department of Justice Report NCJ 250394. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5872. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 5.Carson EA, Anderson E. Prisoners in 2015. 2016. Department of Justice Report NCJ 250229. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5871. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 6.Hartney C, Vuong L. Created Equal: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the US Criminal Justice System. Oakland, CA: National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 2009. Available at: http://www.nccdglobal.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdf/created-equal.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonczar TP. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974–2001. 2003. Department of Justice Report NCJ 197976. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/piusp01.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 8.The Sentencing Project. Incarcerated Women and Girls. 2015. Available at: http://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Incarcerated-Women-and-Girls.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 9.Estelle v Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976).

- 10.United States v DeCologero, 829 F2d 39 (First Cir 1987).

- 11.Isaacs C Treatment Industrial Complex: How For-Profit Prison Corporations are Undermining Efforts to Treat and Rehabilitate Prisoners for Corporate Gain. Philadelphia, PA: American Friends Service Committee; 2014. Available at: https://www.afsc.org/sites/afsc.civicactions.net/files/documents/TIC_report_online.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen RA. Privately run health care in prisons: an industry and health impacts analysis [master’s thesis]. Austin, TX: University of Texas at Austin; 2014. Available at: https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/26560. Accessed April 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carson EA. Prisoners in 2014. 2015. U.S. Department of Justice Report NCJ 248955. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p14.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 14.Noonan M, Rohloff H, Ginder S. Mortality in Local Jails and State Prisons, 2000–2013 - Statistical Tables. 2015. U.S. Department of Justice Report NCJ 248756. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mljsp0013st.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 15.Howell BA, Long JB, Edelman EJ, et al. Incarceration history and uncontrolled blood pressure in a multi-site cohort. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang E, Pletcher M, Lin F, et al. Incarceration, incident hypertension, and access to healthcare: findings from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:687–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang EA, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. A high risk of hospitalization following release from correctional facilities in Medicare beneficiaries: A retrospective matched cohort study, 2002 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1621–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Who’s Who in Jail Management, Fifth edition. Hagerstown, MD: American Jail Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stephan JJ. Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2005. 2008. U.S. Department of Justice Report NCJ 222182. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/csfcf05.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 20.Immigration Detention: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen Management and Oversight of Detainee Medical Care. 2016. Government Accountability Office Report GAO-16–231. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-231. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 21.Wagner P, Rabuy B. Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2016. Prison Policy Initiative. Available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2016.html. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 22.Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M, Unangst J. Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–12. 2015. U.S. Department of Justice Report NCJ 248491. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 23.Chari KA, Simon AE, DeFrances CJ, Maruschak L. National Survey of Prison Health Care: Selected Findings. Natl Health Stat Report 2016;(96):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, et al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health 2009;99:666–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ollove M No Escaping Medical Copayments, Even in Prison. Stateline. Pew Charitable Trusts; July 22, 2015. Available at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2015/07/22/no-escaping-medical-copayments-even-inprison. Accessed April 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Managing Prison Health Care Spending. Pew Charitable Trusts, MacArthur Foundation. 2013. Available at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2014/pctcorrectionshealthcarebrief050814pdf.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 27.Anno BJ. Correctional Health Care: Guidelines for the Management of an Adequate Delivery System. Chicago, IL: National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hale JF, Haley HL, Jones JL, Brennan A, Brewer A. Academic-correctional health partnerships: preparing the correctional health workforce for the changing landscape-focus group research results. J Correct Health Care 2015;21:70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moser DK. Testing a Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Intervention in the Kentucky State Prison System. Paper presented at: Ninth Annual Academic and Health Policy Conference on Correctional Health; March 16–18, 2016; Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baillargeon J, Black SA, Pulvino J, Dunn K. The disease profile of Texas prison inmates. Ann Epidemiol 2000;10:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gates ML, Bradford RK. The impact of incarceration on obesity: are prisoners with chronic diseases becoming overweight and obese during their confinement? J Obes 2015;2015:532468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kauffman RM, Ferketich AK, Murray DM, Bellair PE, Wewers ME. Measuring tobacco use in a prison population. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:582–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khavjou OA, Clarke J, Hofeldt RM, et al. A captive audience: bringing the WISEWOMAN program to South Dakota prisoners. Womens Health Issues 2007;17:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison--a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med 2007;356:157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iguchi MY, Bell J, Ramchand RN, Fain T. How criminal system racial disparities may translate into health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2005;16(4 Suppl B):48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freudenberg N, Moseley J, Labriola M, Daniels J, Murrill C. Comparison of health and social characteristics of people leaving New York City jails by age, gender, and race/ethnicity: implications for public health interventions. Public Health Rep 2007;122:733–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fiscella K, Tancredi D. Socioeconomic status and coronary heart disease risk prediction. JAMA 2008;300:2666–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollack CE, Slaughter ME, Griffin BA, Dubowitz T, Bird CE. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and coronary heart disease risk prediction in a nationally representative sample. Public Health 2012;126:827–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang EA, Wildeman C. Studying health disparities by including incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. JAMA 2011;305:1708–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA 2007;298:1685–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annu Rev Public Health 2005;26:469–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chi JS, Kloner RA. Stress and myocardial infarction. Heart 2003;89:475–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Massoglia M Incarceration as exposure: the prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses. J Health Soc Behav 2008;49:56–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Massoglia M Incarceration, health, and racial disparities in health. Law Soc Rev 2008;42:275–306. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matthews KA, Zhu S, Tucker DC, Whooley MA. Blood pressure reactivity to psychological stress and coronary calcification in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Hypertension 2006;47:391–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabbah W, Watt RG, Sheiham A, Tsakos G. Effects of allostatic load on the social gradient in ischaemic heart disease and periodontal disease: evidence from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mallik-Kane K, Visher CA. Health and Prisoner Reentry: How Physical, Mental, and Substance Abuse Conditions Shape the Process of Reintegration. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2008. Available at: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/31491/411617-Health-and-Prisoner-Reentry.PDF. Accessed April 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wildeman C, Muller C. Mass Imprisonment and Inequality in Health and Family Life. Annu Rev Law Soc Scie 2012;8:11–30. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas EH, Wang EA, Curry LA, Chen PG. Patients’ experiences managing cardiovascular disease and risk factors in prison. Health Justice 2016;4:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eisenberg B, Thomas V. Legal Rights of Prisoners and Detainees with Diabetes: An Introduction and Guide for Attorneys and Advocates. Alexandria, VA: American Diabetes Association; Available at: http://main.diabetes.org/dorg/living-with-diabetes/correctmats-lawyers/legal-rights-of-prisoners-detainees-with-diabetes-intro-guide.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santo A, Iaboni L. What’s in a Prison Meal?. The Marshall Project. July 7, 2015. Available at: https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/07/07/what-s-in-a-prison-meal#.4aa0Lw4lO. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 52.Palmer B Do Prisoners Really Spend All Their Time Lifting Weights? Slate. May 24, 2011. Available at: http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/explainer/2011/05/do_prisoners_really_spend_all_their_time_lifting_weights.html. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 53.Leddy MA, Schulkin J, Power ML. Consequences of high incarceration rate and high obesity prevalence on the prison system. J Correct Health Care 2009;15:318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hunter Buskey RN, Mathieson K, Leafman JS, Feinglos MN. The effect of blood glucose self-monitoring among inmates with diabetes. J Correct Health Care 2015;21:343–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schoenly L Risky Business: Pre-Pour Meds in Jails and Prisons. CorrectionalNurse.net. Available at: http://correctionalnurse.net/risky-business-pre-pour-meds-in-jails-and-prisons/. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 56.Pignolet J Jail policy on prescription meds can leave care gaps. The Spokesman-Review. July 21, 2013. Available at: http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2013/jul/21/jails-policy-on-prescription-medication-can-leave/. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 57.Loeb SJ, Steffensmeier D, Myco PM. In their own words: older male prisoners’ health beliefs and concerns for the future. Geriatr Nurs 2007;28:319–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Redmond N, Baer HJ, Hicks LS. Health behaviors and racial disparity in blood pressure control in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension 2011;57:383–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu K, Ruth KJ, Flack JM, et al. Blood pressure in young blacks and whites: relevance of obesity and lifestyle factors in determining differences: the CARDIA Study. Circulation 1996;93:60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Committee on Causes and Consequences of High Rates of Incarceration; Committee on Law and Justice; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; National Research Council, Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Health and Incarceration: A Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:614–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Butt AA, Xiaoqiang W, Budoff M, Leaf D, Kuller LH, Justice AC. Hepatitis C virus infection and the risk of coronary disease. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, et al. “From the prison door right to the sidewalk, everything went downhill,” a qualitative study of the health experiences of recently released inmates. Int J Law Psychiatry 2011;34:249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The Sentencing Project. A Lifetime of Punishment: The Impact of the Felony Drug Ban on Welfare Benefits. The Sentencing Project: Washington, DC; 2013. Available at: http://sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/A-Lifetime-of-Punishment.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Conklin TJ, Lincoln T, Tuthill RW. Self-reported health and prior health behaviors of newly admitted correctional inmates. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1939–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wakeman SE, McKinney ME, Rich JD. Filling the gap: the importance of Medicaid continuity for former inmates. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:860–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosen DL, Dumont DM, Cislo AM, Brockmann BW, Traver A, Rich JD. Medicaid Policies and Practices in US State Prison Systems. Am J Public Health 2014;104:418–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Birnbaum N, Lavoie M, Redmond N, Wildeman C, Wang EA. Termination of Medicaid policies and implications for the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop: “Cardiovascular Diseases in the Inmate and Released Prison Population”. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/research/reports/nhlbi-workshop-cardiovascular-diseases-inmate-and-released-prison-population. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- 70.Will JC, Loo RK. The WISEWOMAN program: reflection and forecast. Prev Chronic Dis 2008;5(2):A56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Institute of Medicine Committee on Ethical Considerations to DHHS Regulations for the Protection of Prisioners Involved in Research, Board on Health Sciences Policy; Gostin LO, Vanchieri C, Pope A, editors. Ethical Considerations for Research Involving Prisoners. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]