Abstract

Advances in fluorescence microscopy enable monitoring larger brain areas in-vivo with finer time resolution. The resulting data rates require reproducible analysis pipelines that are reliable, fully automated, and scalable to datasets generated over the course of months. We present CaImAn, an open-source library for calcium imaging data analysis. CaImAn provides automatic and scalable methods to address problems common to pre-processing, including motion correction, neural activity identification, and registration across different sessions of data collection. It does this while requiring minimal user intervention, with good scalability on computers ranging from laptops to high-performance computing clusters. CaImAn is suitable for two-photon and one-photon imaging, and also enables real-time analysis on streaming data. To benchmark the performance of CaImAn we collected and combined a corpus of manual annotations from multiple labelers on nine mouse two-photon datasets. We demonstrate that CaImAn achieves near-human performance in detecting locations of active neurons.

Research organism: Mouse, Zebrafish

eLife digest

The human brain contains billions of cells called neurons that rapidly carry information from one part of the brain to another. Progress in medical research and healthcare is hindered by the difficulty in understanding precisely which neurons are active at any given time. New brain imaging techniques and genetic tools allow researchers to track the activity of thousands of neurons in living animals over many months. However, these experiments produce large volumes of data that researchers currently have to analyze manually, which can take a long time and generate irreproducible results.

There is a need to develop new computational tools to analyze such data. The new tools should be able to operate on standard computers rather than just specialist equipment as this would limit the use of the solutions to particularly well-funded research teams. Ideally, the tools should also be able to operate in real-time as several experimental and therapeutic scenarios, like the control of robotic limbs, require this. To address this need, Giovannucci et al. developed a new software package called CaImAn to analyze brain images on a large scale.

Firstly, the team developed algorithms that are suitable to analyze large sets of data on laptops and other standard computing equipment. These algorithms were then adapted to operate online in real-time. To test how well the new software performs against manual analysis by human researchers, Giovannucci et al. asked several trained human annotators to identify active neurons that were round or donut-shaped in several sets of imaging data from mouse brains. Each set of data was independently analyzed by three or four researchers who then discussed any neurons they disagreed on to generate a ‘consensus annotation’. Giovannucci et al. then used CaImAn to analyze the same sets of data and compared the results to the consensus annotations. This demonstrated that CaImAn is nearly as good as human researchers at identifying active neurons in brain images.

CaImAn provides a quicker method to analyze large sets of brain imaging data and is currently used by over a hundred laboratories across the world. The software is open source, meaning that it is freely-available and that users are encouraged to customize it and collaborate with other users to develop it further.

Introduction

Understanding the function of neural circuits is contingent on the ability to accurately record and modulate the activity of large neural populations. Optical methods based on the fluorescence activity of genetically encoded calcium binding indicators (Chen et al., 2013) have become a standard tool for this task, due to their ability to monitor in vivo targeted neural populations from many different brain areas over extended periods of time (weeks or months). Advances in microscopy techniques facilitate imaging larger brain areas with finer time resolution, producing an ever-increasing amount of data. A typical resonant scanning two-photon microscope produces data at a rate greater than 50 GB/Hr (calculation performed on a 512 512 Field of View imaged at 30 Hz producing an unsigned 16-bit integer for each measurement), a number that can be significantly higher (up to more than 1TB/Hour) with other custom recording technologies (Sofroniew et al., 2016; Ahrens et al., 2013; Flusberg et al., 2008; Cai et al., 2016; Prevedel et al., 2014; Grosenick et al., 2017; Bouchard et al., 2015).

This increasing availability and volume of calcium imaging data calls for automated analysis methods and reproducible pipelines to extract the relevant information from the recorded movies, that is the locations of neurons in the imaged Field of View (FOV) and their activity in terms of raw fluorescence and/or neural activity (spikes). The typical steps arising in the processing pipelines are the following (Figure 1a): (i) Motion correction, where the FOV at each data frame (image or volume) is registered against a template to correct for motion artifacts due to the finite scanning rate and existing brain motion, (ii) source extraction where the different active and possibly overlapping sources are extracted and their signals are demixed from each other and from the background neuropil signals (Figure 1b), and (iii) activity deconvolution, where the neural activity of each identified source is deconvolved from the dynamics of the calcium indicator.

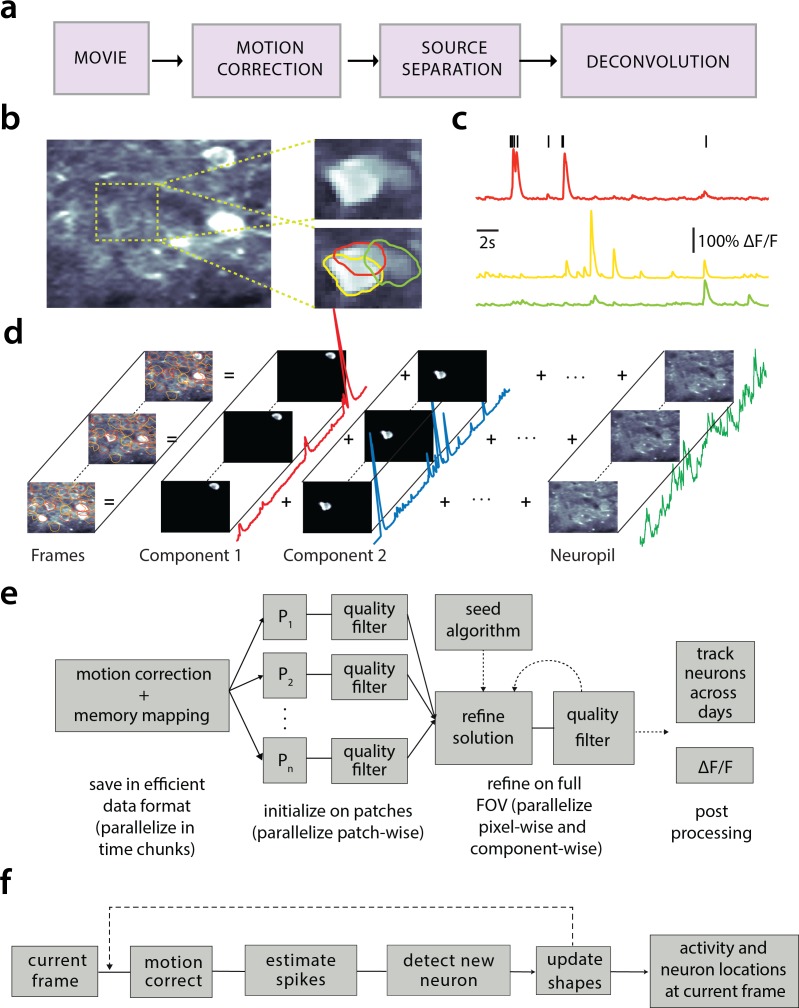

Figure 1. Processing pipeline of CaImAn for calcium imaging data.

(a) The typical pre-processing steps include (i) correction for motion artifacts, (ii) extraction of the spatial footprints and fluorescence traces of the imaged components, and (iii) deconvolution of the neural activity from the fluorescence traces. (b) Time average of 2000 frames from a two-photon microscopy dataset (left) and magnified illustration of three overlapping neurons (right), as detected by the CNMF algorithm. (c) Denoised temporal components of the three neurons in (b) as extracted by CNMF and matched by color (in relative fluorescence change, ). (d) Intuitive depiction of CNMF. The algorithm represents the movie as the sum of spatially localized rank-one spatio-temporal components capturing neurons and processes, plus additional non-sparse low-rank terms for the background fluorescence and neuropil activity. (e) Flow-chart of the CaImAn batch processing pipeline. From left to right: Motion correction and generation of a memory efficient data format. Initial estimate of somatic locations in parallel over FOV patches using CNMF. Refinement and merging of extracted components via seeded CNMF. Removal of low quality components. Final domain dependent processing stages. (f) Flow-chart of the CaImAn online algorithm. After a brief mini-batch initialization phase, each frame is processed in a streaming fashion as it becomes available. From left to right: Correction for motion artifacts. Estimation of activity from existing neurons, identification and incorporation of new neurons. The spatial footprints of inferred neurons are also updated periodically (dashed lines).

Related work

Source extraction

Some source extraction methods attempt the detection of neurons in static images using supervised or unsupervised learning methods. Examples of unsupervised methods on summary images include graph-cut approaches applied to the correlation image (Kaifosh et al., 2014; Spaen et al., 2017), and dictionary learning (Pachitariu et al., 2013). Supervised learning methods based on boosting (Valmianski et al., 2010), or, more recently, deep neural networks have also been applied to the problem of neuron detection (Apthorpe et al., 2016; Klibisz et al., 2017). While these methods can be efficient in detecting the locations of neurons, they cannot infer the underlying activity nor do they readily offer ways to deal with the spatial overlap of different components.

To extract temporal traces jointly with the spatial footprints of the components one can use methods that directly represent the full spatio-temporal data using matrix factorization approaches for example independent component analysis (ICA) (Mukamel et al., 2009), constrained nonnegative matrix factorization (CNMF) (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016) (and its adaptation to one-photon data (Zhou et al., 2018)), clustering based approaches (Pachitariu et al., 2017), dictionary learning (Petersen et al., 2017), or active contour models (Reynolds et al., 2017). Such spatio-temporal methods are unsupervised, and focus on detecting active neurons by considering the spatio-temporal activity of a component as a contiguous set of pixels within the FOV that are correlated in time. While such methods tend to offer a direct decomposition of the data in a set of sources with activity traces in an unsupervised way, in principle they require processing of the full dataset, and thus are quickly rendered intractable. Possible approaches to deal with the data size include distributed processing in High Performance Computing (HPC) clusters (Freeman et al., 2014), spatio-temporal decimation (Friedrich et al., 2017a), and dimensionality reduction (Pachitariu et al., 2017). Recently, Giovannucci et al., 2017 prototyped an online algorithm (OnACID), by adapting matrix factorization setups (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016; Mairal et al., 2010), to operate on calcium imaging streaming data and thus natively deal with large data rates. For a full review see (Pnevmatikakis, 2018).

Deconvolution

For the problem of predicting spikes from fluorescence traces, both supervised and unsupervised methods have been explored. Supervised methods rely on the use of labeled data to train or fit biophysical or neural network models (Theis et al., 2016), although semi-supervised that jointly learn a generative model for fluorescence traces have also been proposed (Speiser et al., 2017). Unsupervised methods can be either deterministic, such as sparse non-negative deconvolution (Vogelstein et al., 2010; Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016) that give a single estimate of the deconvolved neural activity, or probabilistic, that aim to also characterize the uncertainty around these estimates (e.g., (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2013; Deneux et al., 2016)). A recent community benchmarking effort (Berens et al., 2017) characterizes the similarities and differences of various available methods.

CaImAn

Here we present CaImAn, an open source pipeline for the analysis of both two-photon and one-photon calcium imaging data. CaImAn includes algorithms for both offline analysis (CaImAn batch) where all the data is processed at once at the end of each experiment, and online analysis on streaming data (CaImAn online). Moreover, CaImAn requires very moderate computing infrastructure (e.g., a personal laptop or workstation), thus providing automated, efficient, and reproducible large-scale analysis on commodity hardware.

Contributions

Our contributions can be roughly grouped in three different directions:

Methods: CaImAn batch improves on the scalability of the source extraction problem by employing a MapReduce framework for parallel processing and memory mapping which allows the analysis of datasets larger than would fit in RAM on most computer systems. It also improves on the qualitative performance by introducing automated routines for component evaluation and classification, better handling of neuropil contamination, and better initialization methods. While these benefits are here presented in the context of the widely used CNMF algorithm of Pnevmatikakis et al. (2016), they are in principle applicable to any matrix factorization approach.

CaImAn online improves and extends the OnACID prototype algorithm (Giovannucci et al., 2017) by introducing, among other advances, new initialization methods and a convolutional neural network (CNN) based approach for detecting new neurons on streaming data. Our analysis on in vivo two-photon and light-sheet imaging datasets shows that CaImAn online approaches human-level performance and enables novel types of closed-loop experiments. Apart from these significant algorithmic improvements CaImAn includes several useful analysis tools such as, a MapReduce and memory-mapping compatible implementation of the CNMF-E algorithm for one-photon microendoscopic data (Zhou et al., 2018), a novel efficient algorithm for registration of components across multiple days, and routines for segmentation of structural (static) channel information which can be used for component seeding.

Software: CaImAn is a complete open source software suite implemented primarily in Python, and is already widely used by, and has received contributions from, its community. It contains efficient implementations of the standard analysis pipeline steps (motion correction - source extraction - deconvolution - registration across different sessions), as well as numerous other features. Much of the functionality is also available in a separate MATLAB implementation.

Data: We benchmark the performance of CaImAn against a previously unreleased corpus of manually annotated data. The corpus consists of 9 mouse in vivo two-photon datasets. Each dataset is manually annotated by 3–4 independent labelers that were instructed to select active neurons in a principled and consistent way. In a subsequent stage, the annotations were combined to create a ‘consensus’ annotation, that is used to benchmark CaImAn, to train supervised learning based classifiers, and to quantify the limits of human performance. The manual annotations are released to the community, providing a valuable tool for benchmarking and training purposes.

Paper organization

The paper is organized as follows: We first give a brief presentation of the analysis methods and features provided by CaImAn. In the Results section we benchmark CaImAn batch and CaImAn online against a corpus of manually annotated data. We apply CaImAn online to a zebrafish whole brain lightsheet imaging recording, and demonstrate how such large datasets can be processed efficiently in real time. We also present applications of CaImAn batch to one-photon data, as well as examples of component registration across multiple days. We conclude by discussing the utility of our tools, the relationship between CaImAn batch and CaImAn online and outline future directions. Detailed descriptions of the introduced methods are presented in Materials and methods.

Methods

Before presenting the new analysis features introduced with this work, we overview the analysis pipeline that CaImAn uses and builds upon.

Overview of analysis pipeline

The standard analysis pipeline for calcium imaging data used in CaImAn is depicted in Figure 1a. The data is first processed to remove motion artifacts. Subsequently the active components (neurons and background) are extracted as individual pairs of a spatial footprint that describes the shape of each component projected to the imaged FOV, and a temporal trace that captures its fluorescence activity (Figure 1b–d). Finally, the neural activity of each fluorescence trace is deconvolved from the dynamics of the calcium indicator. These operations can be challenging because of limited axial resolution of 2-photon microscopy (or the much larger integration volume in one-photon imaging). This results in spatially overlapping fluorescence from different sources and neuropil activity. Before presenting the new features of CaImAn in more detail, we briefly review how it incorporates existing tools in the pipeline.

Motion correction

CaImAn uses the NoRMCorre algorithm (Pnevmatikakis and Giovannucci, 2017) that corrects non-rigid motion artifacts by estimating motion vectors with subpixel resolution over a set of overlapping patches within the FOV. These estimates are used to infer a smooth motion field within the FOV for each frame. For two-photon imaging data this approach is directly applicable, whereas for one-photon micro-endoscopic data the motion is estimated on high pass spatially filtered data, a necessary operation to remove the smooth background signal and create enhanced spatial landmarks. The inferred motion fields are then applied to the original data frames.

Source extraction

Source extraction is performed using the constrained non-negative matrix factorization (CNMF) framework of Pnevmatikakis et al. (2016) which can extract components with overlapping spatial footprints (Figure 1b). After motion correction the spatio-temporal activity of each source can be expressed as a rank one matrix given by the outer product of two components: a component in space that describes the spatial footprint (location and shape) of each source, and a component in time that describes the activity trace of the source (Figure 1c). The data can be described by the sum of all the resulting rank one matrices together with an appropriate term for the background and neuropil signal and a noise term (Figure 1d). For two-photon data the neuropil signal can be modeled as a low rank matrix (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016). For microendoscopic data the larger integration volume leads to more complex background contamination (Zhou et al., 2018). Therefore, a more descriptive model is required (see Materials and methods (Mathemathical model of the CNMF framework) for a mathematical description). CaImAn batch embeds these approaches into a general algorithmic framework that enables scalable automated processing with improved results versus the original CNMF and other popular algorithms, in terms of quality and processing speed.

Deconvolution

Neural activity deconvolution is performed using sparse non-negative deconvolution (Vogelstein et al., 2010; Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016) and implemented using the near-online OASIS algorithm (Friedrich et al., 2017b). The algorithm is competitive to the state of the art according to recent benchmarking studies (Berens et al., 2017). Prior to deconvolution, the traces are detrended to remove non-stationary effects, for example photo-bleaching.

Online processing

The three processing steps described above can be implemented in an online fashion using the OnACID algorithm (Giovannucci et al., 2017). The method extends the online dictionary learning framework presented in Mairal et al. (2010) for source extraction, by introducing spatial constraints, adding the capability of finding new components as they appear and also incorporating the steps of motion correction and deconvolution (Figure 1e). CaImAn extends and improves the OnACID prototype algorithm by introducing a number of algorithmic features and a CNN based component detection approach, leading to a major performance improvement.

We now present the new methods introduced by CaImAn. More details are given in Materials and methods and pseudocode descriptions of the main routines are given in the Appendix.

Batch processing of large scale datasets on standalone machines

The batch processing pipeline mentioned above represents a computational bottleneck. For instance, a naive first step might be to load in-memory the full dataset; this approach is non-scalable as datasets typically exceed available RAM (and extra memory is required by any analysis pipeline). To limit memory usage, as well as computation time, CaImAn batch relies on a MapReduce approach (Dean and Ghemawat, 2008). Unlike previous work (Freeman et al., 2014), CaImAn batch assumes minimal computational infrastructure (down to a standard laptop computer), is not tied to a particular parallel computation framework, and is compatible with HPC scheduling systems like SLURM (Yoo et al., 2003).

Naive implementations of motion correction algorithms need to either load in memory the full dataset or are constrained to process one frame at a time, therefore preventing parallelization. Motion correction is parallelized in CaImAn batch without significant memory overhead by processing temporal chunks of movie data on different CPUs. First, each chunk is registered with its own template and a new template is formed by the registered data of each chunk. CaImAn batch then broadcasts to each CPU a meta-template, obtained as the median between all templates, which is used to align all the frames in each chunk. Each process writes in parallel to the target file containing motion-corrected data, which is stored as a memory mapped array. This allows arithmetic operations to be performed against data stored on the hard drive with minimal memory use, and data slices to be indexed and accessed without loading the full file in memory. More details are given in Materials and methods (Memory mapping).

Similarly, the source extraction problem, especially in the case of detecting cell bodies, is inherently local with a neuron typically appearing in a neighborhood within a small radius from its center of mass (Figure 2a). Exploiting this locality, CaImAn batch splits the FOV into a set of spatially overlapping patches which enables the parallelization of the CNMF (or any other) algorithm to extract the corresponding set of local spatial and temporal components. The user specifies the size of the patch, the amount of overlap between neighboring patches and the initialization parameters for each patch (number of components and rank background for CNMF, average size of each neuron, stopping criteria for CNMF-E). Subsequently the patches are processed in parallel by the CNMF/CNMF-E algorithm to extract the components and neuropil signals from each patch.

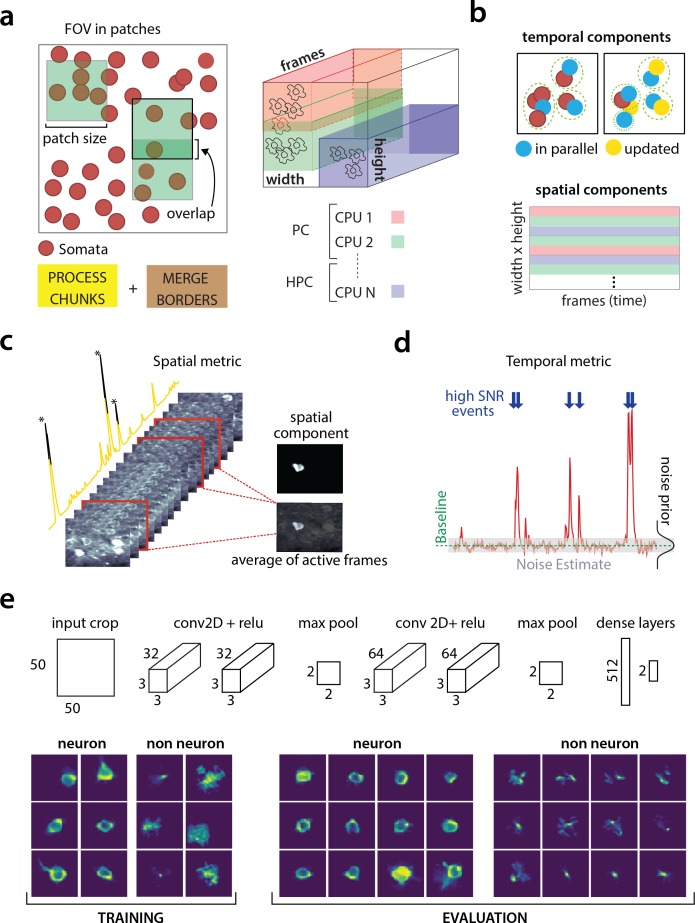

Figure 2. Parallelized processing and component quality assessment for CaImAn batch.

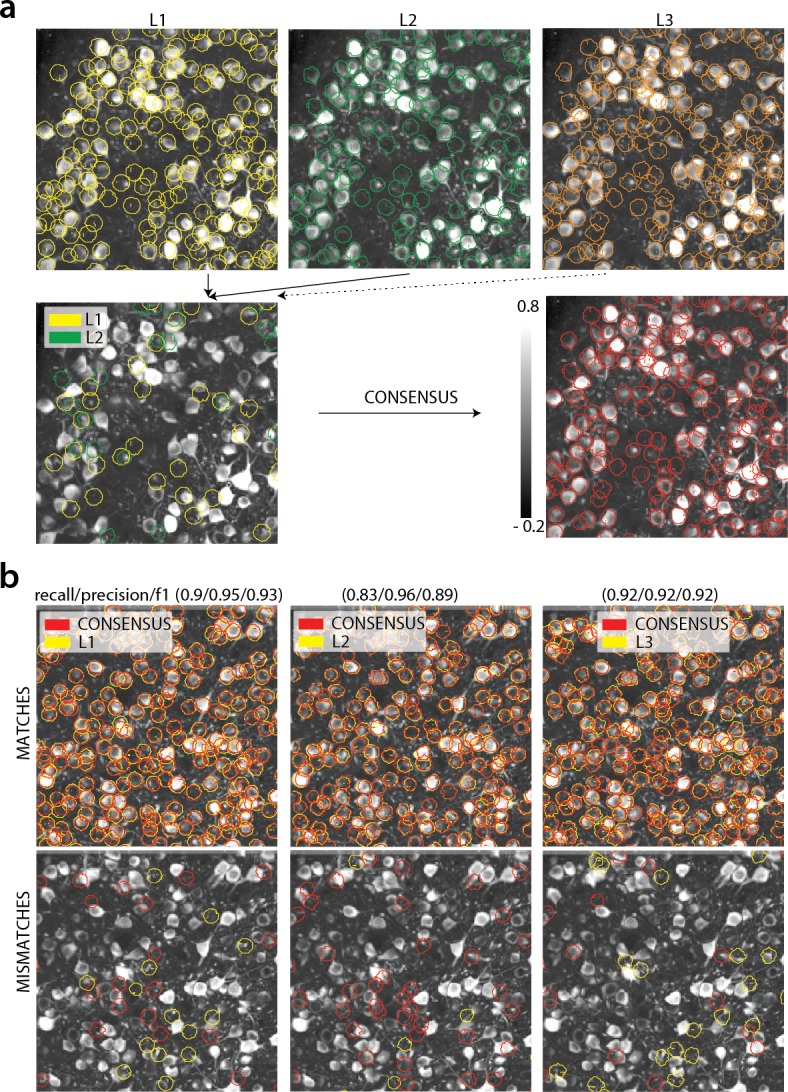

(a) Illustration of the parallelization approach used by CaImAn batch for source extraction. The data movie is partitioned into overlapping sub-tensors, each of which is processed in an embarrassingly parallel fashion using CNMF, either on local cores or across several machines in a HPC. The results are then combined. (b) Refinement after combining the results can also be parallelized both in space and in time. Temporal traces of spatially non-overlapping components can be updated in parallel (top) and the contribution of the spatial footprints for each pixel can be computed in parallel (bottom). Parallelization in combination with memory mapping enable large scale processing with moderate computing infrastructure. (c) Quality assessment in space: The spatial footprint of each real component is correlated with the data averaged over time, after removal of all other activity. (d) Quality assessment in time: A high SNR is typically maintained over the course of a calcium transient. (e) CNN based assessment. Top: A 4-layer CNN based classifier is used to classify the spatial footprint of each component into neurons or not, see Materials and methods (Classification through CNNs) for a description. Bottom: Positive and negative examples for the CNN classifier, during training (left) and evaluation (right) phase. The CNN classifier can accurately classify shapes and generalizes across datasets from different brain areas.

Apart from harnessing memory and computational benefits due to parallelization, processing in patches intrinsically equalizes dynamic range and enables CaImAn batch to detect neurons across the whole FOV, a feature absent in the original CNMF, where areas with high absolute fluorescence variation tend to be favored. This results in better source extraction performance. After all the patches have been processed, the results are embedded within the FOV (Figure 2a), and the overlapping regions between neighboring patches are processed so that components corresponding to the same neuron are merged. The process is summarized in algorithmic format in Algorithm 1 and more details are given in Materials and methods (Combining results from different patches).

Initialization methods

Due to the non-convex nature of the objective function for matrix factorization, the choice of the initialization method can severely impact the final results. CaImAn batch provides an extension of the GreedyROI method used in Pnevmatikakis et al. (2016), that detects neurons based on localized spatiotemporal activity. CaImAn batch can also be seeded with binary masks that are obtained from different sources, for example through manual annotation or segmentation of structural channel (SeededInitialization, Algorithm 3). More details are given in Materials and methods (Initialization strategies).

Automated component evaluation and classification

A common limitation of matrix factorization algorithms is that the number of components that the algorithm seeks during its initialization must be pre-determined by the user. For example, Pnevmatikakis et al. (2016) suggest detecting a large number of components which are then ordered according to their size and activity pattern, with the user deciding on a cut-off threshold. When processing large datasets in patches the target number of components is passed on to every patch implicitly assuming a uniform density of (active) neurons within the entire FOV. This assumption does not hold in the general case and can produce many spurious components. CaImAn introduces tests, based on unsupervised and supervised learning, to assess the quality of the detected components and eliminate possible false positives. These tests are based on the observation that active components are bound to have a distinct localized spatio-temporal signature within the FOV. In CaImAn batch, these tests are initially applied after the processing of each patch is completed, and additionally as a post-processing step after the results from the patches have been merged and refined, whereas in CaImAn online they are used to screen new candidate components. We briefly present these tests below and refer to Materials and methods (Details of quality assessment tests) for more details:

Spatial footprint consistency: To test whether a detected component is spurious, we correlate the spatial footprint of this component with the average frame of the data, taken over the intervals when the component, with no other overlapping component, was active (Figure 2c). The component is rejected if the correlation coefficient is below a certain threshold (e.g., ).

Trace SNR: For each component we computed the peak SNR of its temporal trace averaged over the duration of a typical transient (Figure 2d). The component is rejected if the computed SNR is below a certain threshold (e.g., ).

CNN based classification: We also trained a 4-layer convolutional neural network (CNN) to classify spatial footprints into true or false components (Figure 2e), where a true component here corresponds to a spatial footprint that resembles the soma of a neuron. The classifier, which we call batch classifier, was trained on a small corpus of manually annotated datasets (full description given in section Benchmarking against consensus annotation) and exhibited similar high classification performance on test samples from different datasets.

While CaImAn uses the CNMF algorithm, the tests described above can be applied to results obtained from any source extraction algorithm, highlighting the modularity of our tools.

Online analysis with CaImAn online

CaImAn supports online analysis on streaming data building on the core of the prototype algorithm of Giovannucci et al., 2017, and extending it in terms of qualitative performance and computational efficiency:

Initialization: Apart from initializing CaImAn online with CaImAn batch on a small time interval, CaImAn online can also be initialized in a bare form over an even smaller time interval, where only the background components are estimated and all the components are determined during the online analysis. This process, named BareInitialization, can be achieved by running the CNMF algorithm (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016) over the small interval to estimate the background components and possibly a small number of components. The SeededInitialization of Algorithm 3 can also be used.

Deconvolution: Instead of a separate step after demixing as in Giovannucci et al., 2017, deconvolution here can be performed simultaneously with the demixing online, leading to more stable traces especially in cases of low-SNR, as also observed in Pnevmatikakis et al. (2016). Online deconvolution can also be performed for models that assume second order calcium dynamics, bringing the full power of Friedrich et al., 2017b to processing of streaming data.

Epochs: CaImAn online supports multiple passes over the data, a process that can detect early activity of neurons that were not picked up during the initial pass, as well as smooth the activity of components that were detected at late stages during the first epoch.

New component detection using a CNN: To search for new components in a streaming setup, OnACID keeps a buffer of the residual frames, computed by subtracting the activity of already found components and background signals. Candidate components are determined by looking for points of maximum energy in this residual signal, after some smoothing and dynamic range equalization. For each such point identified, a candidate shape and trace are constructed using a rank-1 NMF in a local neighborhood around this point. In its original formulation (Giovannucci et al., 2017), the shape of the component was evaluated using the space correlation test described above. Here, we use a CNN classifier approach that tests candidate components by examining their spatial footprint as obtained by the average of the residual buffer across time. This online classifier (different from the batch classifier for quality assessment described above), is trained to be strict, minimizing the number of false positive components that enter the online processing pipeline. It can test multiple components in parallel, and it achieves better performance with no hyper-parameter tuning compared to the previous approach. More details on the architecture and training procedure are given in Materials and methods (Classification through CNNs). The identification of candidate components is further improved by performing spatial high pass filtering on the average residual buffer to enhance its contrast. The new process for detecting neurons is described in Algorithm 4 and 5. See Videos 1 and 2 on a detailed graphic description of the new component detection step.

Distributed update of spatial footprints: A time limiting step in OnACID (Giovannucci et al., 2017) is the periodic update of all spatial footprints at given frames. This constraint is lifted with aImAn online that distributes the update of spatial footprints among all frames ensuring a similar processing speed for each frame. See Materials and methods (Distributed shape update) for more details.

Component registration across multiple sessions

CaImAn provides a method to register components from the same FOV across different sessions. The method uses an intersection over union metric to calculate the distance between different cells in different sessions and solves a linear assignment problem to perform the registration in a fully automated way (RegisterPair, Algorithm 7). To register the components between more than two sessions (RegisterMulti, Algorithm 8), we order the sessions chronologically and register the components of the current session against the union of components of all the past sessions aligned to the current FOV. This allows for the tracking of components across multiple sessions without the need of pairwise registration between each pair of sessions. More details as well as discussion of other methods (Sheintuch et al., 2017) are given in Materials and methods (Component registration).

Benchmarking against manual annotations

To quantitatively evaluate CaImAn we benchmarked its results against manual annotations.

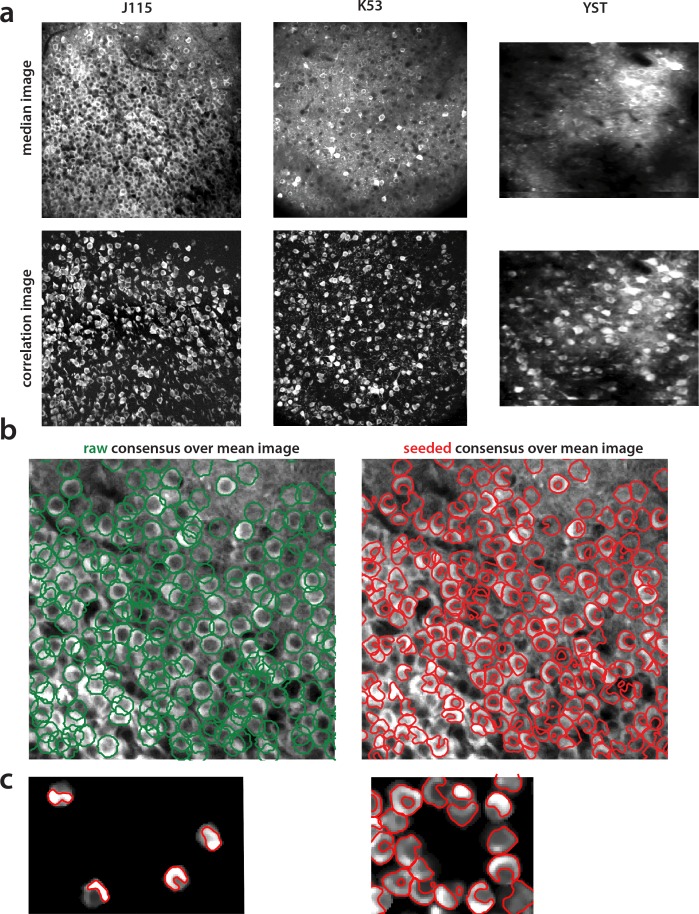

Creating consensus labels through manual annotation

We collected manual annotations from multiple independent labelers who were instructed to find round or donut shaped (since proteins expressing the calcium indicator are confined outside the cell nuclei, neurons will appear as ring shapes, with a dark disk in the center) active neurons on nine two-photon in vivo mouse brain datasets. To distinguish between active and inactive neurons, the annotators were given the max-correlation image for each dataset (the value of the correlation image for each pixel represent the average correlation (across time) between the pixel and its neighbors (Smith and Häusser, 2010). This summarization can enhance active neurons and suppress neuropil for two photon datasets (Figure 3—figure supplement 1a). See Materials and methods (Collection of manual annotations) for more information). In addition, the annotators were given a temporally decimated background subtracted movie of each dataset. The datasets were collected at various labs and from various brain areas (hippocampus, visual cortex, parietal cortex) using several GCaMP variants. A summary of the features of all the annotated datasets is given in Table 2.

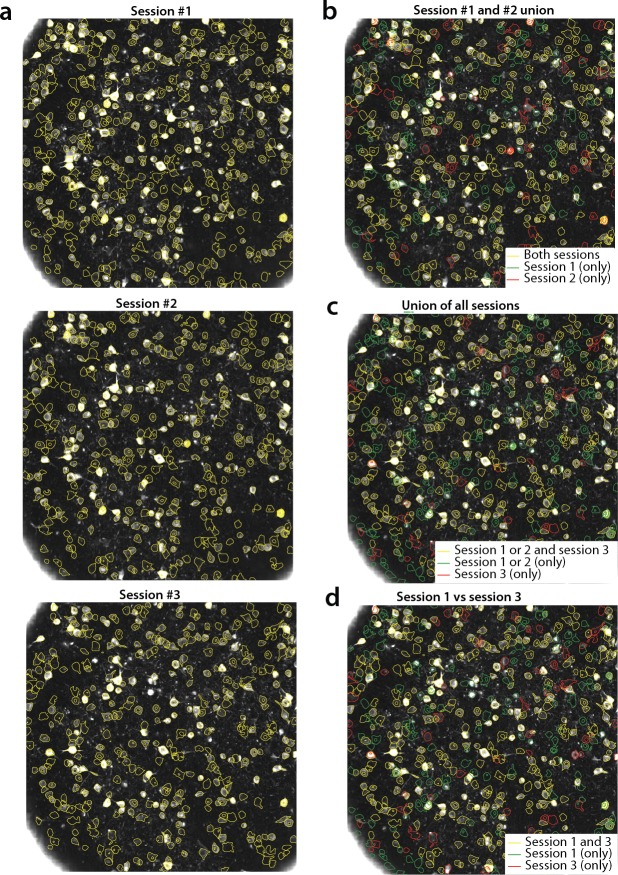

To address human variability in manual annotation each dataset was labeled by 3 or 4 independent labelers, and the final consensus annotation dataset was created by having the different labelers reaching a consensus over their disagreements (Figure 3a). The consensus annotation was taken as ‘ground truth’ for the purpose of benchmarking CaImAn and each individual labeler (Figure 3b). More details are given in Materials and methods (Collection of manual annotations). We believe that the current database, which is publicly available at https://users.flatironinstitute.org/~neuro/caiman_paper, presents an improvement over the existing Neurofinder database (http://neurofinder.codeneuro.org/) in several aspects:

Figure 3. Consensus annotation generation.

(a) Top: Individual manual annotations on the dataset K53 (only part of the FOV is shown) for labelers L1 (left), L2 (middle), L3(right). Contour plots are plotted against the max-correlation image of the dataset. Bottom: Disagreements between L1 and L2 (left), and consensus labels (right). In this example, consensus considerably reduced the number of initially selected neurons. (b) Matches (top) and mismatches (bottom) between each individual labeler and consensus annotation. Red contours on the mismatches panels denote false negative contours, that is components in the consensus not selected by the corresponding labeler, whereas yellow contours indicate false positive contours. Performance of each labeler is given in terms of precision/recall and score and indicates an unexpected level of variability between individual labelers.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Construction of components obtained from consensus annotation.

Consistency: The datasets are annotated using exactly the same procedure (see Materials and methods), and in all datasets the goal is to detect only active cells. In contrast, the annotation of the various Neurofinder datasets is performed either manually or automatically by segmenting an image of a static (structural) indicator. Even though structural indicators could be used for ground truth extraction, the segmentation of such images is not a straightforward problem in the case of dense expression, and the stochastic expression of indicators can lead to mismatches between functional and structural indicators.

Uncertainty quantification: By employing more than one human labeler we discovered a surprising level of disagreement between different annotators (see Table 1, Figure 3b for details). This result indicates that individual annotations can be unreliable for benchmarking purposes and that unreproducible scientific results might ensue. The combination of the various annotations leads to more reliable set of labels and also quantifies the limits of human performance.

Table 1. Results of each labeler, CaImAn batch and CaImAn online algorithms against consensus annotation.

Results are given in the form , and empty entries correspond to datasets not manually annotated by the specific labeler. The number of frames for each dataset, as well as the number of neurons that each labeler and algorithm found are also given. In italics the datasets used to train the CNN classifiers.

| Name # of frames |

L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | CaImAn batch | CaImAn online |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N.01.01

1825 |

0.80 241(0.95, 0.69) | 0.89 287(0.96, 0.83) | 0.78 386(0.73, 0.84) | 0.75 289(0.80, 0.70) | 0.76 317(0.76, 0.77) | 0.75 298(0.81, 0.70) |

|

N.03.00.t

2250 |

X | 0.90 188(0.88, 0.92) | 0.85 215(0.78, 0.93) | 0.78 206(0.73, 0.83) | 0.78 154(0.76, 0.80) | 0.74 150(0.79, 0.70) |

|

N.00.00

2936 |

X | 0.92 425(0.93, 0.91) | 0.83 402(0.86, 0.80) | 0.87 358(0.96, 0.80) | 0.72 366(0.79, 0.67) | 0.69 259(0.87, 0.58) |

| YST 3000 |

0.78 431(0.76, 0.81) | 0.90 465(0.85, 0.97) | 0.82 505(0.75, 0.92) | 0.79 285(0.96, 0.67) | 0.77 332(0.85, 0.70) | 0.77 330(0.84, 0.70) |

| N.04.00.t 3000 |

X | 0.69 471(0.54, 0.97) | 0.75 411(0.61, 0.97) | 0.87 326(0.78, 0.98) | 0.69 218(0.69, 0.70) | 0.7 260(0.68, 0.72) |

| N.02.00 8000 |

0.89 430(0.86, 0.93) | 0.87 382(0.88, 0.85) | 0.84 332(0.92, 0.77) | 0.82 278(1.00, 0.70) | 0.78 351(0.78, 0.78) | 0.78 334(0.85, 0.73) |

| J123 41000 |

X | 0.83 241(0.73, 0.96) | 0.90 181(0.91, 0.90) | 0.91 177(0.92, 0.89) | 0.73 157(0.88, 0.63) | 0.82 172(0.85, 0.80) |

| J115 90000 |

0.85 708(0.96, 0.76) | 0.93 869(0.94, 0.91) | 0.94 880(0.95, 0.93) | 0.83 635(1.00, 0.71) | 0.78 738(0.87, 0.71) | 0.79 1091(0.71, 0.89) |

| K53 116043 |

0.89 795(0.96, 0.83) | 0.92 928(0.92, 0.92) | 0.93 875(0.95, 0.91) | 0.83 664(1.00, 0.72) | 0.76 809(0.80, 0.72) | 0.81 1025(0.77, 0.87) |

| mean ± std | 0.84±0.05(0.9±0.08, 0.8±0.08) | 0.87±0.07(0.85±0.13, 0.92±0.05) | 0.85±0.06(0.83±0.11, 0.88±0.06) | 0.83±0.09(0.91±0.1, 0.78±0.1) | 0.754±0.03(0.8±0.06, 0.72±0.05) | 0.762±0.05(0.82±0.06, 0.73±0.1) |

Comparing CaImAn against manual annotations

To compare CaImAn against the consensus annotation, the manual annotations were used as binary masks to construct the consensus spatial and temporal components, using the SeededInitialization procedure (Algorithm 3) of CaImAn batch. This step is necessary to adapt the manual annotations to the shapes of the actual spatial footprints of each neuron in the FOV (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), as manual annotations primarily produced elliptical shapes. The set of spatial footprints obtained from CaImAn is registered against the set of consensus spatial footprints (derived as described above) using our component registration algorithm RegisterPair (Algorithm 7). Performance is then quantified using a precision/recall framework similar to other studies (Apthorpe et al., 2016; Giovannucci et al., 2017).

Software

CaImAn is developed by and for the community. Python open source code for the above-described methods is available at https://github.com/flatironinstitute/CaImAn (Giovannucci et al., 2018; copy archived at https://github.com/elifesciences-publications/CaImAn). The repository contains documentation, several demos, and Jupyter notebook tutorials, as well as visualization tools, and a message/discussion board. The code, which is compatible with Python 3, uses several open-source libraries, such as OpenCV (Bradski, 2000), scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al., 2011), and scikit-image (van der Walt et al., 2014). Most routines are also available in MATLAB at https://github.com/flatironinstitute/CaImAn-MATLAB (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2018; copy archived at https://github.com/elifesciences-publications/CaImAn-MATLAB). We provide tips for efficient data analysis at https://github.com/flatironinstitute/CaImAn/wiki/CaImAn-Tips. All the annotated datasets together with the individual and consensus annotation are available at https://users.flatironinstitute.org/~neuro/caiman_paper. All the material is also available from the Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/record/1659149/export/hx#.XC_Rms9Ki9t

Results

Manual annotations show a high degree of variability

We compared the performance of each human annotator against a consensus annotation. The performance was quantified with a precision/recall framework and the results of the performance of each individual labeler against the consensus annotation for each dataset is given in Table 1. The range of human performance in terms of score was 0.69–0.94. All annotators performed similarly on average (0.84 0.05, 0.87 0.07, 0.85 0.06, 0.83 0.08). We also ensured that the performance of labelers was stable across time (i.e. their learning curve plateaued, data not shown). As shown in Table 1 (see also Figure 4b) the score was never 1, and in most cases it was less or equal to 0.9, demonstrating significant variability between annotators. Figure 3 (bottom) shows an example of matches and mismatches between individual labelers and consensus annotation for dataset K53, where the level of agreement was relatively high. The high degree of variability between human responses indicates the challenging nature of the source extraction problem and raises reproducibility concerns in studies relying heavily on manual ROI selection.

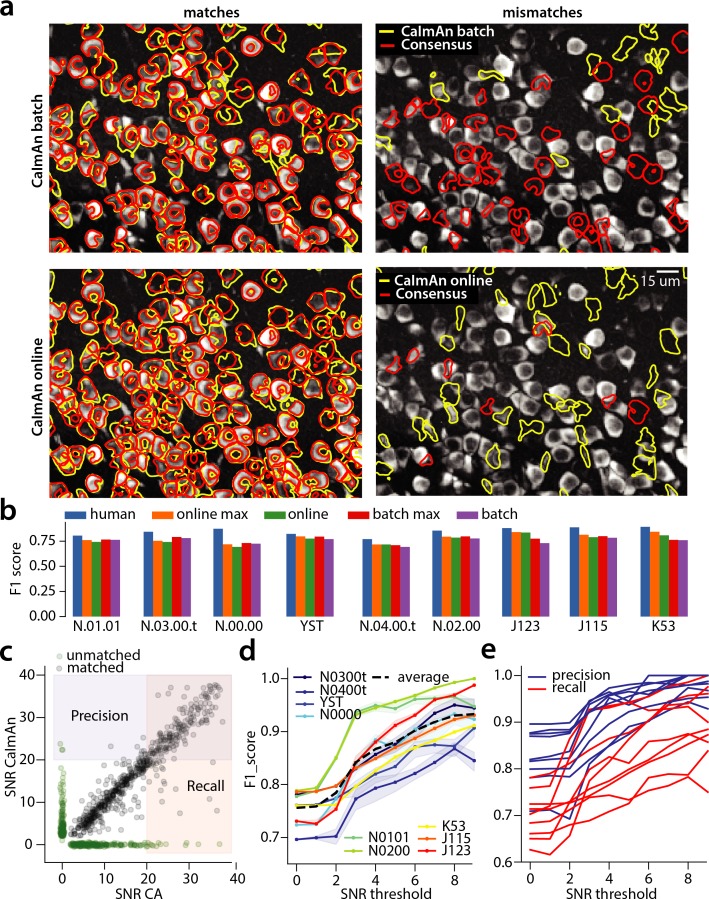

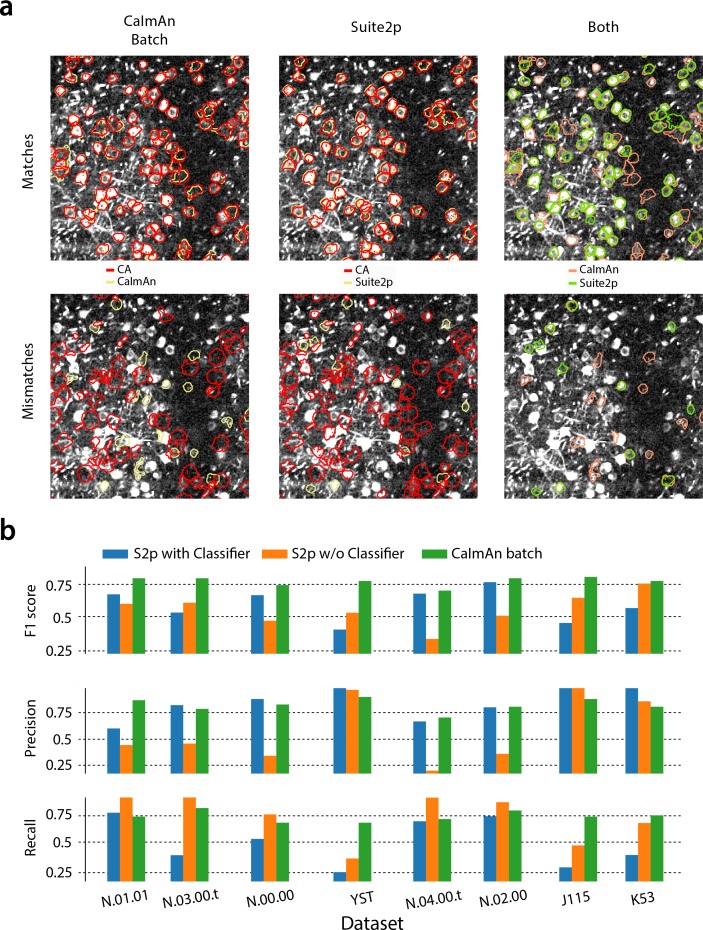

Figure 4. Evaluation of CaImAn performance against manually annotated data.

(a) Comparison of CaImAn batch (top) and CaImAn online (bottom) when benchmarked against consensus annotation for dataset K53. For a portion of the FOV, correlation image overlaid with matches (left panels, red: consensus, yellow: CaImAn) and mismatches (right panels, red: false negatives, yellow: false positives). (b) Performance of CaImAn batch, and CaImAn online vs average human performance (blue). For each algorithm the results with both the same parameters for each dataset and with the optimized per dataset parameters are shown. CaImAn batch and CaImAn online reach near-human accuracy for neuron detection. Complete results with precision and recall for each dataset are given in Table 1. (c–e) Performance of CaImAn batch increases with peak SNR. (c) Example of scatter plot between SNRs of matched traces between CaImAn batch and consensus annotation for dataset K53. False negative/positive pairs are plotted in green along the x- and y-axes respectively, perturbed as a point cloud to illustrate the density. Most false positive/negative predictions occur at low SNR values. Shaded areas represent thresholds above which components are considered for matching (blue for CaImAn batch and red for consensus selected components) (d) score and upper/lower bounds of CaImAn batch for all datasets as a function of various peak SNR thresholds. Performance of CaImAn batch increases significantly for neurons with high peak SNR traces (see text for definition of metrics and the bounds). (e) Precision and recall of CaImAn batch as a function of peak SNR for all datasets. The same trend is observed for both precision and recall.

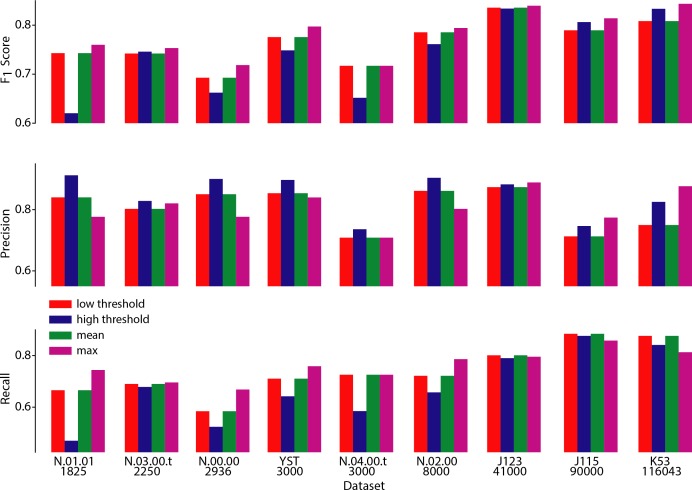

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Performance of CaImAn online over different choices of parameters.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. CaImAn batch outperforms the Suite2p algorithm in all datasets when benchmarked against the consensus annotation.

This process may have generated slightly biased results in favor of each individual annotator as the consensus annotation is always a subset of the union of the individual annotations. We also used an alternative cross-validation approach, where the labels of each annotator were compared with the combined results of the remaining annotators. The combination was constructed using a majority vote when a dataset was labeled from 4 annotators, or an intersection of selections when a dataset was labeled by 3. The results (see Table 3 in Materials and methods) indicate an even higher level of disagreement between the annotators with lower average score 0.82 0.06 (mean STD) and range of values . More details are given in Materials and methods (Cross-Validation analysis of manual annotations).

CaImAn batch and CaImAn online detect neurons with near-human accuracy

We first benchmarked CaImAn batch and CaImAn online against consensus annotation for the task of identifying neurons locations and their spatial footprints, using the same precision recall framework (Table 1). Figure 4a shows an example dataset (K53) along with neuron-wise matches and mismatches between CaImAn batch vs consensus annotation (top) and CaImAn online vs consensus annotation (bottom).

The results indicate a similar performance between CaImAn batch and CaImAn online; CaImAn batch has scores in the range 0.69–0.78 and average performance 0.75 0.03 (mean STD). On the other hand CaImAn online had scores in the range 0.70–0.82 and average performance 0.76 0.05. While the two algorithms performed similarly on average, CaImAn online tends to perform better for longer datasets (e.g., datasets J115, J123, K53 that all have more than 40000 frames; see also Table 2 for characteristics of the various datasets). CaImAn batch operates on the entire dataset at once, representing each spatial footprint with a constant in time vector. In contrast, CaImAn online operates at a local level looking at a short window over time to detect new components, while adaptively changing their spatial footprint based on new data. This enables CaImAn online to adapt to slow non-stationarities that can appear in long experiments.

Table 2. Properties of manually annotated datasets.

For each dataset the duration, imaging rate and calcium indicator are given, as well as the number of active neurons selected after consensus between the manual annotators.

| Name | Area brain | Lab | Rate (Hz) | Size (TXY) | Indicator | Labelers | Neurons CA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF.01.01 | Visual Cortex | Hausser | 7 | 1825 × 512 × 512 | GCaMP6s | 4 | 333 |

| NF.03.00.t | Hippocampus | Losonczy | 7 | 2250 × 498 × 467 | GCaMP6f | 3 | 178 |

| NF.00.00 | Cortex | Svoboda | 7 | 2936 × 512 × 512 | GCaMP6s | 3 | 425 |

| YST | Visual Cortex | Yuste | 10 | 3000 × 200 × 256 | GCaMP3 | 4 | 405 |

| NF.04.00.t | Cortex | Harvey | 7 | 3000 × 512 × 512 | GCaMP6s | 3 | 257 |

| NF.02.00 | Cortex | Svoboda | 30 | 8000 × 512 × 512 | GCaMP6s | 4 | 394 |

| J123 | Hippocampus | Tank | 30 | 41000 × 458 × 477 | GCaMP5 | 3 | 183 |

| J115 | Hippocampus | Tank | 30 | 90000 × 463 × 472 | GCaMP5 | 4 | 891 |

| K53 | Parietal Cortex | Tank | 30 | 116043 × 512 × 512 | GCaMP6f | 4 | 920 |

CaImAn approaches but is in most cases below the accuracy levels of human annotators (Figure 4b). We attribute this to two primary factors: First, CNMF detects active components regardless of their shape, and can detect non-somatic structures with significant transients. While non-somatic components can be filtered out to some extent using the CNN classifier, their existence degrades performance compared to the manual annotations that consist only of neurons. Second, to demonstrate the generality and ease of use of our tools, the results presented here are obtained by running CaImAn batch and CaImAn online with exactly the same parameters for each dataset (see Materials and methods (Implementation details)): fine-tuning to each individual dataset can significantly increase performance (Figure 4b).

To test the later point we measured the performance of CaImAn online on the nine datasets, as a function of 3 parameters: (i) the trace SNR threshold for testing the traces of candidate components, (ii) the CNN threshold for testing the shapes of candidate components, and (iii) the number of candidate components to be tested at each frame (more details can be found in Materials and methods (Implementation details for CaImAn online)). By choosing a parameter combination that maximizes the value for each dataset, the performance generally increases across the datasets with scores in the range 0.72–0.85 and average performance (see Figure 4 (orange) and Figure 4—figure supplement 1 (magenta)). This analysis also shows that in general a strategy of testing a large number of components per timestep but with stricter criteria, achieves better results than testing fewer components with looser criteria (at the expense of increased computational cost). The results also indicate different strategies for parameter choice depending on the length of a dataset: Lower threshold values and/or larger number of candidate components (Figure 4—figure supplement 1 (red)), lead to better values for shorter datasets, but can decrease precision and overall performance for longer datasets. The opposite also holds for higher threshold values and/or smaller number of candidate components (Figure 4—figure supplement 1 (blue)), where CaImAn online for shorter datasets can suffer from lower recall values, whereas in longer datasets CaImAn online can add neurons over a longer period of time while maintaining high precision values and thus achieve better performance. A similar grid search was also performed for the CaImAn batch algorithm where four parameters of the component evaluation step (space correlation, trace SNR, min/max CNN thresholds) were optimized individually to filter out false positives. This procedure led to scores in in the range 0.71–0.81 and average performance (Figure 4 (red)).

We also compared the performance of CaImAn against Suite2p (Pachitariu et al., 2017), another popular calcium imaging data analysis package. By using a small grid search around some default parameters of Suite2p we extracted the set of parameters that worked better in the eight datasets where the algorithm converged (in the dataset J123 Suite2p did not converge). CaImAn outperformed Suite2p in all datasets with the latter obtaining scores in the range 0.41–0.75, with average performance . More details about the comparison are shown in Figure 4—figure supplement 2 and Materials and methods (Comparison with Suite2p).

Neurons with higher SNR transients are detected more accurately

For the parameters that yielded on average the best results (see Table 1), both CaImAn batch and CaImAn online exhibited higher precision than recall ( vs for CaImAn batch, and vs for CaImAn online, respectively). This can be partially explained by the component evaluation steps at the end of patch processing (Figure 1e) for CaImAn batch (and the end of each frame for CaImAn online) which aim to filter out false positive components, thus increasing precision while leaving recall intact (or in fact lowering it in case where true positive components are filtered out). To better understand this behavior, we analyzed the CaImAn batch performance as a function of the SNR of the inferred and consensus traces (Figure 4c–e). The SNR measure of a trace corresponds to the peak-SNR averaged over the length of a typical trace (see Materials and methods (Detecting fluorescence traces with high SNR)). An example is shown in Figure 4c where the scatter plot of SNR between matched consensus and inferred traces is shown (false negative/positive components are shown along the x- and y- axis, respectively). To evaluate the performance we computed a precision metric as the fraction of inferred components above a certain SNR threshold that are matched with a consensus component (Figure 4c, shaded blue). Similarly we computed a recall metric as the fraction of consensus components above a SNR threshold that are detected by CaImAn batch (Figure 4c, shaded red), and an score as the harmonic mean of the two (Figure 4d). The results indicate that the performance significantly improves as a function of the SNR for all datasets considered, improving on average from 0.73 when all neurons are considered to 0.92 when only neurons with traces having SNR are considered (Figure 4d). This increase in the score resulted increase in both the precision and the recall as a function of the SNR (Figure 4e)(these precision and recall metrics are computed on different sets of neurons, and therefore strictly speaking one cannot combine them to form an score. However, they can be bound from above by being evaluated on the set of matched and non-matched components where at least one trace is above the threshold (union of blue and pink zones in Figure 4c) or below by considering only matched and non-matched components where both consensus and inferred traces have SNR above the threshold (intersection of blue and pink zones in Figure 4c). In practice these bounds were very tight for all but one dataset (Figure 4d). More details can be found in Materials and methods (Performance quantification as a function of SNR)). A similar trend is also observed for CaImAn online (data not shown).

CaImAn reproduces the consensus traces with high fidelity

Testing the quality of the inferred traces is more challenging due to the unavailability of ground truth data in the context of large scale in vivo recordings. As mentioned above, we defined as ‘ground truth’ the traces obtained by running the CNMF algorithm seeded with the binary masks obtained by consensus annotation procedure. After spatial alignment with the results of CaImAn , the matched traces were compared both for CaImAn batch and for CaImAn online. Figure 5a, shows an example of 5 of these traces for the dataset K53, showing very similar behavior of the traces in these three different cases.

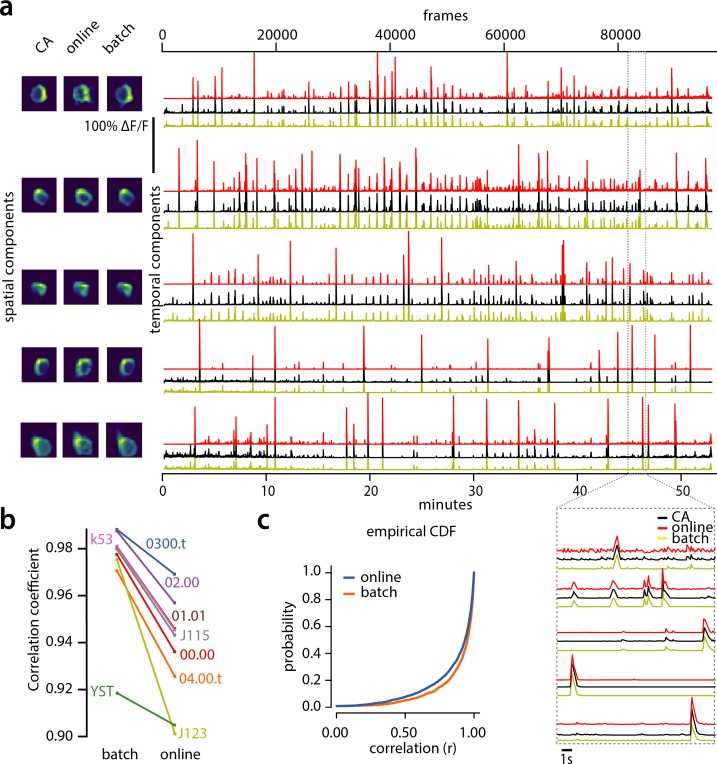

Figure 5. Evaluation of CaImAn extracted traces against traces derived from consensus annotation.

(a) Examples of shapes (left) and traces (right) are shown for five matched components extracted from dataset K53 for consensus annotation (CA, black), CaImAn batch (yellow) and CaImAn online (red) algorithms. The dashed gray portion of the traces is also shown magnified (bottom-right). Consensus spatial footprints and traces were obtained by seeding CaImAn with the consensus binary masks. The traces extracted from both versions of CaImAn match closely the consensus traces. (b) Slope graph for the average correlation coefficient for matches between consensus and CaImAn batch, and between consensus and CaImAn online. Batch processing produces traces that match more closely the traces extracted from the consensus labels. (c) Empirical cumulative distribution functions of correlation coefficients aggregated over all the tested datasets. Both distributions exhibit a sharp derivative close to 1 (last bin), with the batch approach giving better results.

To quantify the similarity we computed the correlation coefficients of the traces (consensus vs CaImAn batch, and consensus vs CaImAn online) for all the nine datasets (Figure 5b–c). Results indicated that for all but one dataset (Figure 5b) CaImAn batch reproduced the traces with higher fidelity, and in all cases the mean correlation coefficients was higher than 0.9, and the empirical histogram of correlation coefficients peaked at the maximum bin 0.99–1 (Figure 5c). The results indicate that the batch approach extracts traces closer to the consensus traces. This can be attributed to a number of reasons: By processing all the time points simultaneously, the batch approach can smooth the trace estimation over the entire time interval as opposed to the online approach where at each timestep only the information up to that point is considered. Moreover, CaImAn online might not detect a neuron until it becomes strongly active. This neuron’s activity before detection is unknown and has a default value of zero, resulting in a lower correlation coefficient. While this can be ameliorated to a great extent with additional passes over the data, the results indicate the trade-offs inherent between online and batch algorithms.

Online analysis of a whole brain zebrafish dataset

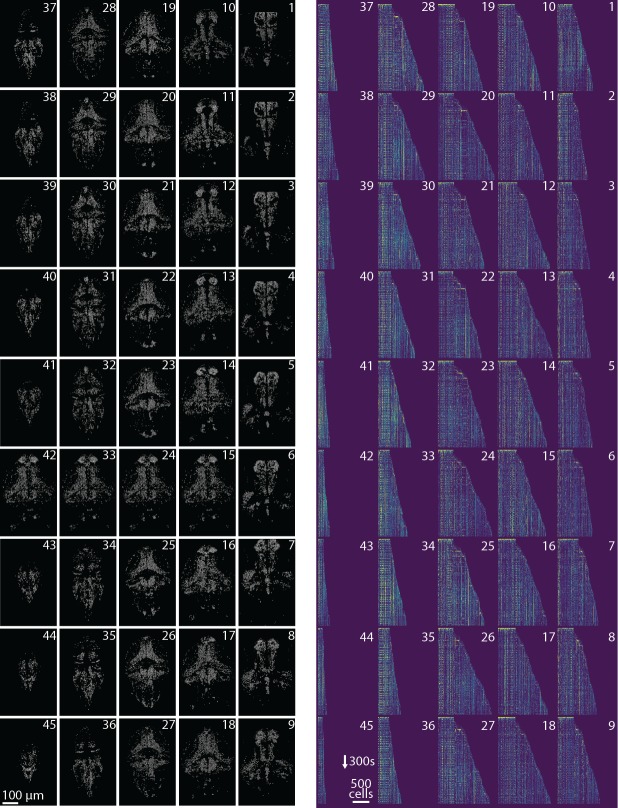

We tested CaImAn online with a 380 GB whole brain dataset of larval zebrafish (Danio rerio) acquired with a light-sheet microscope (Kawashima et al., 2016). The imaged transgenic fish (Tg(elavl3:H2B-GCaMP6f)jf7) expressed the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f in almost all neuronal nuclei. Data from 45 planes (FOV 820 × 410 m, spaced at 5.5 m intervals along the dorso-ventral axis) was collected at 1 Hz for 30 min (for details about preparation, equipment and experiment refer to Kawashima et al. (2016)). With the goal of simulating real-time analysis of the data, we run all the 45 planes in parallel on a computing cluster with nine nodes (each node is equipped with 24 CPUs and 128–256 GB RAM, Linux CentoOS). Data was not stored locally in each machine but directly accessed from a network drive.

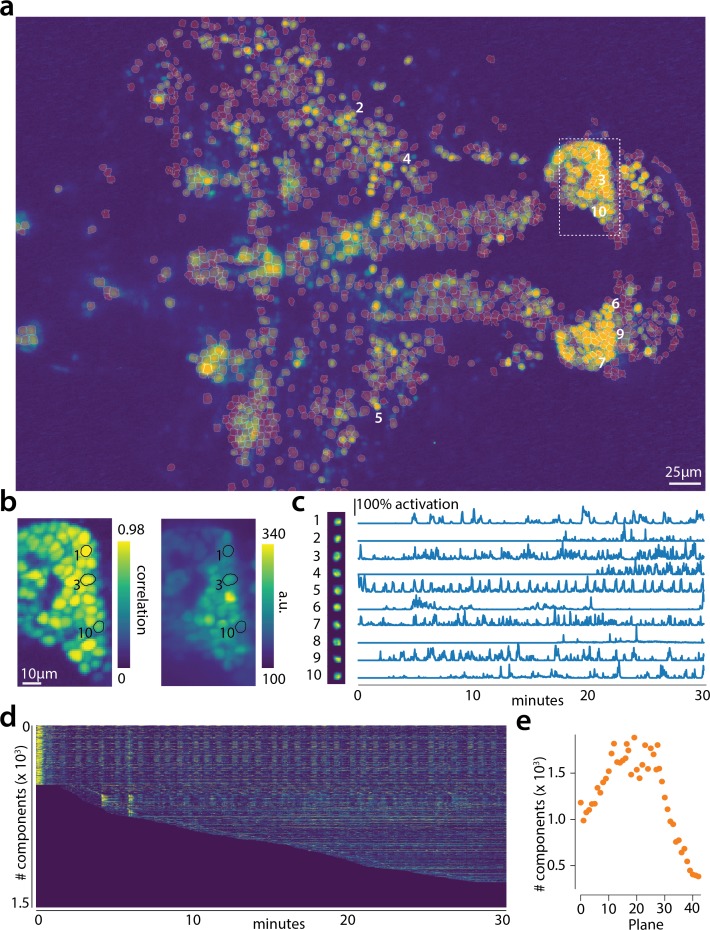

The algorithm was initialized with CaImAn batch run on 200 initial frames and looking for 500 components. The small number of frames (1885) and the large FOV size ( pixels) for this dataset motivated this choice of increased number of components during initialization. In Figure 6 we report the results of the analysis for plane number 11 of 45. For plane 11, CaImAn online found 1524 neurons after processing 1685 frames. Since no ground truth was available for this dataset, it was only possible to evaluate the performance of this algorithm by visual inspection. CaImAn online identified all the neurons with a clear footprint in the underlying correlation image (higher SNR, Figure 6a) and missed a small number of the fainter ones (low SNR). By visual inspection of the components the authors could find very few false positives. Given that the parameters were not tuned and that the classifier was not trained on zebrafish neurons, we hypothesize that the algorithm is biased towards a high precision result. Spatial components displayed the expected morphological features of neurons (Figure 6b–c). Considering all the planes (Figure 6e and Figure 6—figure supplement 1) CaImAn online was able to identify in a single pass of the data a total of 66108 neurons. See Video 1 for a summary across all planes. The analysis was performed in 21 min, with the first three minutes spent in initialization, and the remaining 18 in processing the data in streaming mode (and in parallel for each plane). This demonstrates the ability of CaImAn online to process large amounts of data in real-time (see also Figure 8 for a discussion of computational performance).

Figure 6. Online analysis of a 30 min long whole brain recording of the zebrafish brain.

(a) Correlation image overlaid with the spatial components (in red) found by the algorithm (portion of plane 11 out of 45 planes in total). (b) Correlation image (left) and mean image (right) for the dashed region in panel (a) with superimposed the contours of the neurons marked in (a). (c) Spatial (left) and temporal (right) components associated to the ten example neurons marked in panel (a). (d) Temporal traces for all the neurons found in the FOV in (a); the initialization on the first 200 frames contained 500 neurons (present since time 0). (e) Number of neurons found per plane (See also Figure 6—figure supplement 1 for a summary of the results from all planes).

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. Spatial and temporal components for all planes.

Figure 6—video 1. Results of CaImAn online initialized by CaImAn batch on a whole brain zebrafish dataset.

Video 1. Depiction of CaImAn online on a small patch of in vivo cortex data.

Top left: Raw data. Bottom left: Footprints of identified components. Top right: Mean residual buffer and proposed regions for new components (in white squares). Enclosings of accepted regions are shown in magenta. Several regions are proposed multiple times before getting accepted. This is due to the strict behavior of the classifier to ensure a low number of false positives. Bottom right: Reconstructed activity.

Video 2. Depiction of CaImAn online on a single plane of mesoscope data courtesy of E. Froudarakis, J. Reimers and A. Tolias (Baylor College of Medicine).

Top left: Raw data. Top right: Inferred activity (without neuropil). Bottom left: Mean residual buffer and accepted regions for new components (magenta squares). Bottom right: Reconstructed activity.

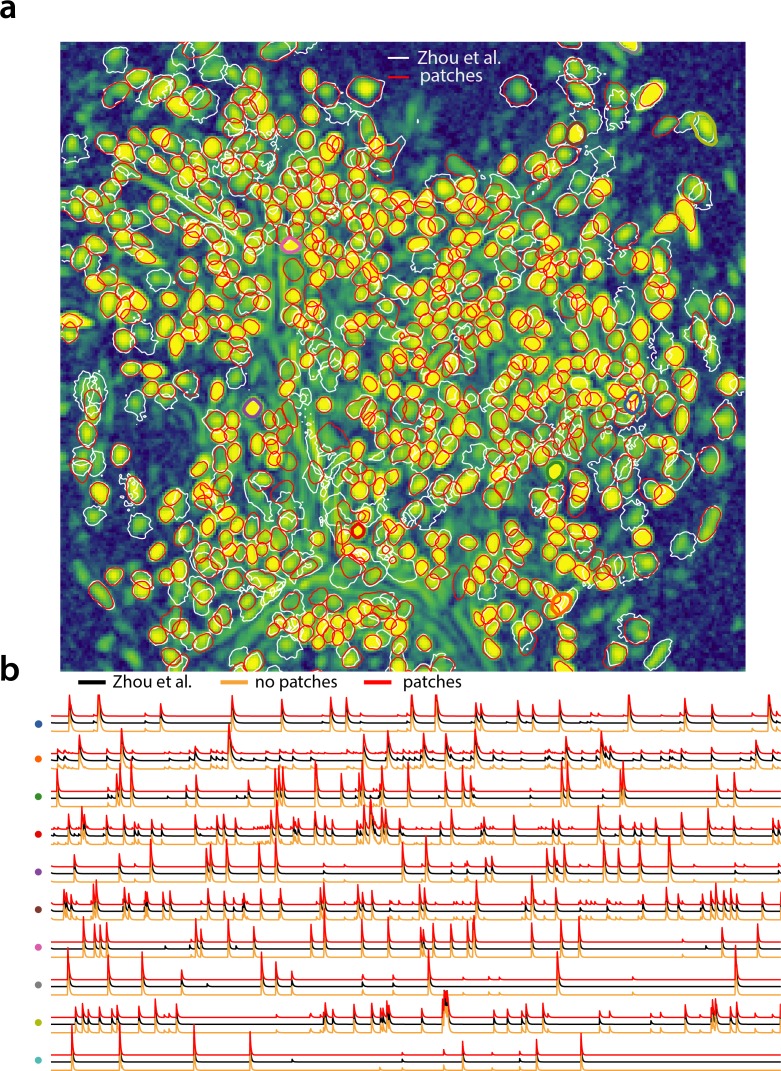

Analyzing 1p microendoscopic data using CaImAn

We tested the CNMF-E implementation of CaImAn batch on in vivo microendosopic data from mouse dorsal striatum, with neurons expressing GCaMP6f. 6000 frames were acquired at 30 frames per second while the mouse was freely moving in an open field arena (for further details refer to Zhou et al., 2018). In Figure 7 we report the results of the analysis using CaImAn batch with patches and compare to the results of the MATLAB implementation of Zhou et al. (2018). Both implementations detect similar components (Figure 7a) with an -score of 0.89. 573 neurons were found in common by both implementations. 106 and 31 additional components were detected by Zhou et al. (2018) and CaImAn batch respectively. The median correlation between the temporal traces of neurons detected by both implementations was 0.86. Similar results were also obtained by running CaImAn batch without patches. Ten example temporal traces are plotted in Figure 7b.

Figure 7. Analyzing microendoscopic 1 p data with the CNMF-E algorithm using CaImAn batch .

(a) Contour plots of all neurons detected by the CNMF-E (white) implementation of Zhou et al. (2018) and CaImAn batch (red) using patches. Colors match the example traces shown in (b), which illustrate the temporal components of 10 example neurons detected by both implementations CaImAn batch . reproduces with reasonable fidelity the results of Zhou et al. (2018).

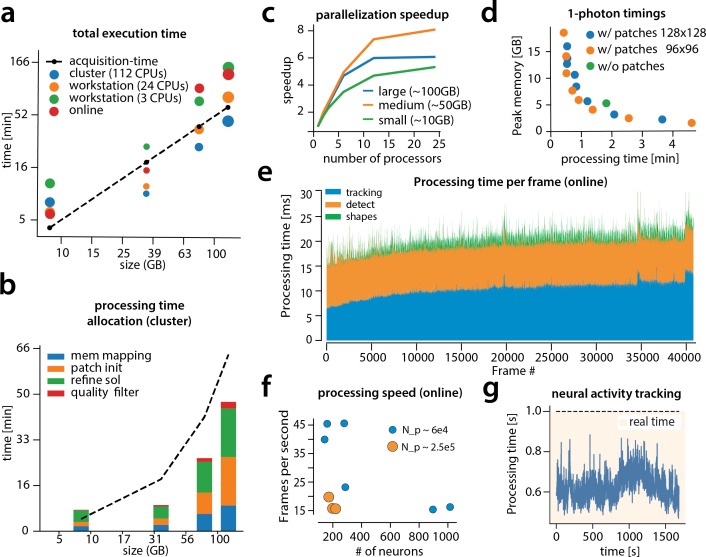

Computational performance of CaImAn

We examined the performance of CaImAn in terms of processing time for the various analyzed datasets presented above (Figure 8). The processing time discussed here excludes motion correction, which is highly efficient and primarily depends on the level of the FOV discretization for non-rigid motion correction (Pnevmatikakis and Giovannucci, 2017). For CaImAn batch , each dataset was analyzed using three different computing architectures: (i) a single laptop (MacBook Pro) with 8 CPUs (Intel Core i7) and 16 GB of RAM (blue in Figure 8a), (ii) a linux-based workstation (CentOS) with 24 CPUs (Intel Xeon CPU E5-263 v3 at 3.40 GHz) and 128 GB of RAM (magenta), and (iii) a linux-based HPC cluster (CentOS) where 112 CPUs (Intel Xeon Gold 6148 at 2.40 GHz, four nodes, 28 CPUs each) were allocated for the processing task (yellow). Figure 8a shows the processing of CaImAn batch as a function of dataset size on the four longest datasets, whose size exceeded 8 GB, on log-log plot.

Figure 8. Time performance of CaImAn batch and CaImAn online for four of the analyzed datasets (small, medium, large and very large).

(a) Log-log plot of total processing time as a function of data size for CaImAn batch two-photon datasets using different processing infrastructures: (i) a desktop with three allocated CPUs (green), (ii) a desktop with 24 CPUs allocated (orange), and (iii) a HPC where 112 CPUs are allocated (blue). The results indicate a near linear scaling of the processing time with the size of dataset, with additional dependence on the number of found neurons (size of each point). Large datasets ( GB) can be seamlessly processed with moderately sized desktops or laptops, but access to a HPC enables processing with speeds faster than the acquisition time (considered 30 Hz for a 512512 FOV here). However, for smaller datasets the advantages of adopting a cluster vanishes, because of the inherent overhead. The results of CaImAn online using the laptop, using the ‘strict’ parameter setting (Figure 4—figure supplement 1), are also plotted in red indicating near real-time processing speed. (b) Break down of processing time for CaImAn batch (excluding motion correction). Processing with CNMF in patches and refinement takes most of the time for CaImAn batch. (c) Computational gains for CaImAn batch due to parallelization for three datasets with different sizes. The parallelization gains are computed by using the same 24 CPU workstation and utilizing a different number of CPUs for each run. The different parts of the algorithm exhibit the same qualitative characteristics (data not shown). (d) Cost analysis of CNMF-E implementation for processing a 6000 frames long 1p dataset. Processing in patches in parallel induces a time/memory tradeoff and can lead to speed gains (patch size in legend). (e) Computational cost per frame for analyzing dataset J123 with CaImAn onlne. Tracking existing activity and detecting new neurons are the most expensive steps, whereas udpating spatial footprints can be efficiently distributed among all frames. (f) Processing speed of CaImAn onlne for all annotated datasets. Overall speed depends on the number of detected neurons and the size of the FOV ( stands for number of pixels). Spatial downsampling can speed up processing. (g) Cost of neural activity online tracking for the whole brain zebrafish dataset (maximum time over all planes per volume). Tracking can be done in real-time using parallel processing.

Results show that, as expected, employing more processing power results in faster processing. CaImAn batch on a HPC cluster processes data faster than acquisition time (Figure 8a) even for very large datasets. Processing of an hour long dataset was feasible within 3 hr on a single laptop, even though the size of the dataset is several times the available RAM. Here, acquisition time is computed based on the assumption of imaging a FOV discretized over a grid at a 30 Hz rate (a typical two-photon imaging setup with resonant scanning microscopes). Dataset size is computed by representing each measurement using single precision arithmetic, which is the minimum precision required for standard algebraic processing. These assumptions lead to a data rate of 105 GB/hr. In general performance scales linearly with the number of frames (and hence, the size of the dataset), but we also observe a dependency on the number of components, which during the solution refinement step can be quadratic. This is expected from the properties of the matrix factorization approach as also noted by past studies (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016). The majority of the time (Figure 8b) required for CaImAn batch processing is taken by CNMF algorithmic processing either during the initialization in patches (orange bar) or during merging and refining the results of the individual patches (green bar).

To study the effects of parallelization we ran CaImAn batch several times on the same hardware (linux-based workstation with 24CPUs), limiting the runs to different numbers of CPUs each time (Figure 8c). In all cases we saw significant performance gains from parallel processing, with the gains being similar for all stages of processing (patch processing, refinement, and quality testing, data not shown). We saw the most effective scaling with our 50 G dataset (J123). For the largest datasets (J115, GB), the speedup reaches a plateau due to limited available RAM, suggesting that more RAM can lead to better scaling. For small datasets ( GB) the speedup factor is limited by increased communications overhead (indicative of weak scaling in the language of high performance computing).

The cost of processing 1p data in CaImAn batch using the CNMF-E algorithm (Zhou et al., 2018) is shown (Figure 8d) for our workstation-class hardware. Splitting in patches and processing in parallel can lead to computational gains at the expense of increased memory usage. This is because the CNMF-E introduces a background term that has the size of the dataset and needs to be loaded and updated in memory in two copies. This leads to processing times that are slower compared to the standard processing of 2 p datasets, and higher memory requirements. However ( 8 c), memory usage can be controlled enabling scalable inference at the expense of slower processing speeds.

Figure 8a also shows the performance of CaImAn online (red markers). Because of the low memory requirements of the streaming algorithm, this performance only mildly depends on the computing infrastructure, allowing for near real-time processing speeds on a standard laptop (Figure 8a). As discussed in Giovannucci et al., 2017 processing time of CaImAn online depends primarily on (i) the computational cost of tracking the temporal activity of discovered neurons, (ii) the cost of detecting and incorporating new neurons, and (iii) the cost of periodic updates of spatial footprints. Figure 8e shows the cost of each of these steps for each frame, for one epoch of processing of the dataset J123. Distributing the spatial footprint update more uniformly among all frames removes the computational bottleneck appearing in Giovannucci et al., 2017, where all the footprints where updated periodically at the same frame. The cost of detecting and incorporating new components remains approximately constant across time, and is dependent on the number of candidate components at each timestep. In this example five candidate components were used per frame resulting in a relatively low cost (7 ms per frame). A higher number of candidate components can lead to higher recall in shorter datasets but at a computational cost. This step can benefit by the use of a GPU for running the online CNN on the footprints of the candidate components. Finally, as noted in Giovannucci et al., 2017, the cost of tracking components can be kept low, and increases mildly over time as more components are found by the algorithm (the analysis here excludes the cost of motion correction, because the files where motion corrected before hand to ensure that manual annotations and the algorithms where operating on the same FOV. This cost depends on whether rigid or pw-rigid motion correction is being used. Rigid motion correction taking on average 3–5 ms per frame for a pixel FOV, whereas pw-rigid motion correction with patch size pixel is typically 3–4 times slower).

Figure 8f shows the overall processing speed (in frames per second) for CaImAn online for the nine annotated datasets. Apart from the number of neurons, the processing speed also depends on the size of the imaged FOV and the use of spatial downsampling. Datasets with smaller FOV (e.g., YST) or datasets where spatial downsampling is used can achieve higher processing speeds for the same amount of neurons (blue dots in Figure 8f) as opposed to datasets where no spatial downsampling is used (orange dots in Figure 8f). In most cases, spatial downsampling can be used to increase processing speed without significantly affecting the quality of the results, an observation consistent with previous studies (Friedrich et al., 2017a).

In Figure 8g the cost per frame is plotted for the analysis of the whole brain zebrafish recording. The lower imaging rate (1 Hz) allows for tracing of neural activity with computational costs significantly lower than the 1 s between volume imaging time (Figure 8e), even in the presence of a large number of components (typically more than 1000 per plane, Figure 6) and the significantly larger FOV ( pixels).

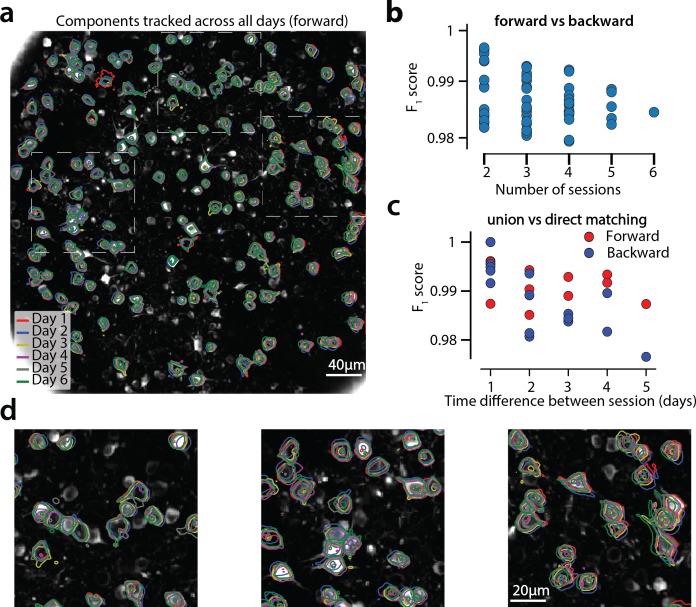

CaImAn successfully tracks neurons across multiple days

Figure 9 shows an example of tracking neurons across six different sessions corresponding to six different days of mouse cortex in vivo data using our multi-day registration algorithm RegisterMulti (see Materials and methods, Algorithm 8). 453, 393, 375, 378, 376, and 373 active components were found in the six sessions, respectively. Our tracking method detected a total of 686 distinct active components. Of these, 172, 108, 70, 92, 82, and 162 appeared in exactly 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and all six sessions respectively. Contour plots of the 162 components that appeared in all sessions are shown in Figure 9a, and parts of the FOV are highlighted in Figure 9d showing that components can be tracked in the presence of non-rigid deformations of the FOV between the different sessions.

Figure 9. Components registered across six different sessions (days).

(a) Contour plots of neurons that were detected to be active in all six imaging sessions overlaid on the correlation image of the sixth imaging session. Each color corresponds to a different session. (b) Stability of multiday registration method. Comparisons of forward and backward registrations in terms of scores for all possible subsets of sessions. The comparisons agree to a very high level, indicating the stability of the proposed approach. (c) Comparison (in terms of score) of pair-wise alignments using readouts from the union vs direct alignment. The comparison is performed for both the forward and the backwards alignment. For all pairs of sessions the alignment using the proposed method gives very similar results compared to direct pairwise alignment. (d) Magnified version of the tracked neurons corresponding to the squares marked in panel (a). Neurons in different parts of the FOV exhibit different shift patterns over the course of multiple days, but can nevertheless be tracked accurately by the proposed multiday registration method.

Figure 9—figure supplement 1. Tracking neurons across days; step-by-step description of multi session registration.

To test the stability of RegisterMulti for each subset of sessions, we repeated the same procedure running backwards in time starting from day 6 and ending at day 1, a process that also generated a total of 686 distinct active components. We identified the components present in at least a given subset of sessions when using the forward pass, and separately when using the backwards pass, and compared them against each other (Figure 9b) for all possible subsets. Results indicate a very high level of agreement between the two approaches with many of the disagreements arising near the boundaries (data not shown). Disagreements near the boundaries can arise because the forward pass aligns the union with the FOV of the last session, whereas the backwards pass with the FOV of the first session, potentially leading to loss of information near the boundaries.

A step by step demonstration of the tracking algorithm for the first three sessions is shown in Figure 9—figure supplement 1. Our approach allows for the comparison of two non-consecutive sessions through the union of components without the need of a direct pairwise registration (Figure 9—figure supplement 1f), where it is shown that registering sessions 1 and 3 directly and through the union leads to nearly identical results. Figure 9c compares the registrations for all pairs of sessions using the forward (red) or the backward (blue) approach, with the direct pairwise registrations. Again, the results indicate a very high level of agreement, indicating the stability and effectiveness of the proposed approach.

A different approach for multiple day registration was recently proposed by Sheintuch et al. (2017) (CellReg). While a direct comparison of the two methods is not feasible in the absence of ground truth, we tested our method against the same publicly available datasets from the Allen Brain Observatory visual coding database. (http://observatory.brain-map.org/visualcoding). Similarly to Sheintuch et al. (2017) the same experiment performed over the course of different days produced very different populations of active neurons. To measure performance of RegisterPair for pairwise registration, we computed the transitivity index proposed in Sheintuch et al. (2017). The transitivity property requires that if cell 'a’ from session one matches with cell 'b’ from session 2, and cell 'b’ from session two matches with cell 'c’ from session 3, then cell 'a’ from session one should match with cell 'c’ from session 3 when sessions 1 and 3 are registered directly. For all ten tested datasets the transitivity index was very high, with values ranging from 0.976 to 1 (, data not shown). A discussion between the similarities and differences of the two methods is given in Materials and methods.

Discussion

Reproducible and scalable analysis for the 99%

Significant advances in the reporting fidelity of fluorescent indicators, and the ability to simultaneously record and modulate neurons granted by progress in optical technology, have made calcium imaging one of the two most prominent experimental methods in systems neuroscience alongside electrophysiology recordings. Increasing adoption has led to an unprecedented wealth of imaging data which poses significant analysis challenges. CaImAn is designed to provide the experimentalist with a complete suite of tools for analyzing this data in a formal, scalable, and reproducible way. The goal of this paper is to present the features of CaImAn and examine its performance in detail. CaImAn embeds existing methods for preprocessing calcium imaging data into a MapReduce framework and augments them with supervised learning algorithms and validation metrics. It builds on the CNMF algorithm of Pnevmatikakis et al. (2016) for source extraction and deconvolution, extending it along the lines of (i) reproducibility and performance improvement, by automating quality assessment through the use of unsupervised and supervised learning algorithms for component detection and classification, and (ii) scalability, by enabling fast large scale processing with standard computing infrastructure (e.g., a commodity laptop or workstation). Scalability is achieved by either using a MapReduce batch approach, which employs parallel processing of spatially overlapping, memory mapped, data patches; or by integrating the online processing framework of Giovannucci et al., 2017 within our pipeline. Apart from computational gains both approaches also result in improved performance. Towards our goal of providing a single package for dealing with standard problems arising in analysis of imaging data, CaImAn also includes an implementation of the CNMF-E algorithm of Zhou et al. (2018) for the analysis of microendoscopic data, as well as a novel method for registering analysis results across multiple days.

Towards surpassing human neuron detection performance

To evaluate the performance of CaImAn batch and CaImAn online, we used a number of distinct labelers to generate a corpus of nine annotated two-photon imaging datasets. The results indicated a surprising level of disagreement between individual labelers, highlighting both the difficulty of the problem, and the non-reproducibility of the laborious task of human annotation. CaImAn reached near-human performance with respect to this consensus annotation, by using the same parameters for all the datasets without dataset dependent parameter tweaking. Such tweaking can include setting the SNR threshold based on the noise level of the recording, the complexity of the neuropil signal based on the level of background activity, or specialized treatment around the boundaries of the FOV to compensate for eventual imaging artifacts, and as shown can significantly improve the results on individual datasets. As demonstrated in our results, optimal parameter setting for CaImAn online can also depend on the length of the experiment with stricter parameters being more suitable for longer datasets. We plan to investigate parameter schemes that increase in strictness over the course of an experiment.