Abstract

Scientific advances in healthcare have been disproportionately distributed across social strata. Disease burden is also disproportionately distributed, with marginalized groups having the highest risk of poor health outcomes. Social determinants are thought to influence healthcare delivery and the management of chronic diseases among marginalized groups, but the current conceptualization of social determinants lacks a critical focus on the experiences of people within their environment. The purpose of this article is to integrate the literature on marginalization and situate the concept in the framework of social determinants of health. We demonstrate that social position links marginalization and social determinants of health. This perspective provides a critical lens to assess the societal power dynamics that influence the construction of the socio-environmental factors affecting health. Linking marginalization with social determinants of health can improve our understanding of the inequities in health care delivery and the disparities in chronic disease burden among vulnerable groups.

Advances in research have significantly improved the prevention and treatment of diseases; however, these advances have been disproportionately distributed across social strata (Havranek et al., 2015). Persons in vulnerable social class, race, lower socioeconomic status, and other minority groups have the highest burden of chronic diseases (Havranek et al., 2015). For instance, non-Hispanic blacks have the highest rate of cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality in the United States (Mensah, Mokdad, Ford, Greenlund, & Croft, 2005).

Unfortunately, outcomes of chronic diseases are not only a function of the healthcare received during illness, but societal factors such as social services, employment, education and basic needs also affect health in important ways (Bamberg, Chiswell, & Toumbourou, 2011). These social determinants of health (SDH) are inequitably distributed across gender, class, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic and minority groups and may be linked to the disproportionate burden of chronic diseases in vulnerable groups (Heidenreich, Trogdon, & Khavjou, 2011). Individuals who suffer these disparities and inequities have been referred to as marginalized (Meleis & Im, 1999; Venkatapuram, Bell, & Marmot, 2010). Marginalization was defined by Hall et al. in 1994 as “the process through which persons are peripheralized based on their identities, associations, experiences, and environment” (Hall, Stevens, & Meleis, 1994, p. 25).

To achieve a significant improvement in overall health, we need to understand how SDH affect health, specifically, disparities in chronic disease burden (Bamberg et al., 2011). The task of clarifying this relationship can be facilitated by considering the process of marginalization within the framework of SDH. The purpose of this article is to review and integrate the literature surrounding marginalization to situate the concept in the framework of social determinants of health. This will allow for better understanding and exploration of the relationship between SDH and the disparities/inequity in chronic disease burden among disparate population groups.

We first present a brief review of SDH and marginalization, followed by the methods used in this integrative review. We present our findings in three sections. First, we provide three themes that reflect how marginalization has been used in research over the last 28 years. Then in the last two sections, we present our conceptualization of the link between SDH and marginalization and provide implications for future research and practice. We conclude this paper with global implications and identify limitations to our review.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

The World Health Organization (WHO), 2010) defines SDH as “the circumstances in which people are born, live, work and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness” (2010). Based on this definition, the WHO recommends three areas of action in addressing SDH: (1) improve the circumstances that determine people’s daily lives, (2) identify and address the structural drivers (the social and economic forces such as the inequitable distribution of power, money and resources surrounding vulnerability of those conditions and (3) identify measures and frameworks to develop and expand scholarship around the SDH while raising awareness of the inequitable distribution of social and healthcare services. This agenda presents an urgent need to understand the health of vulnerable populations in the context of their situation and daily lives.

Additionally, the Healthy People initiative was created to improve health outcomes by addressing healthcare issues that result from social and physical environment (WHO, 2010). The key domains of SDH identified by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Healthy People 2020 are economics, education, social and community context of living, neighborhoods and the built environment and their relationship to health. These domains reflect the fact that health outcomes are impacted by both the experience of individuals in their environment and the environment’s effects on the individuals (Havranek et al., 2015). Hence, integrating marginalization and SDH, two interconnected concepts, can highlight the relationship between them and aid in developing interventions to address the effects of this reciprocal relationship and the inequity that exists in the distribution of health promoting services across social strata.

MARGINALIZATION

Marginalization was proposed as a nursing theory by Hall and colleagues in 1994 (Meleis & Im, 1999). The primary theorists identified seven properties of marginalization: Intermediacy, Differentiation, Power, Secrecy, Reflectiveness, Voice, and Liminality (Hall et al., 1994; Mohammed, 2006). After this introduction, the theory underwent a period of metamorphosis because of social events and influences that required it to be revisited by Hall multiple times. In 1999 marginalization was expanded to incorporate a global perspective and seven additional properties were proposed: Exteriority, Constraint, Eurocentrism, Economics, Seduction, Testimonies, and Hope (Hall, 1999). After the expansion, marginalization became rooted in the nursing profession. By the end of the 1990s, it had been used in the study of various populations including older black Americans (Brown & Tedrick, 1993; Hall, 1999), student nurses (Andersson, 1995; Brown & Tedrick, 1993), and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (Andersson, 1995; Ware, 1999). From the early 2000s to 2018, marginalization was applied to a broader range of patients by different research teams who used multiple variants of the definition proposed by Hall and colleagues. These patient populations included chronically ill adolescents, homeless persons, drug users, and women (Bethune-Davies, McWilliam, & Berman, 2006; Coumans & Spreen, 2003; Coumans, Knibbe, & van de Mheen, 2006; DiNapoli & Murphy, 2002; Dodgson & Struthers, 2005; Gyarmathy & Neaigus, 2011; Koci, McFarlane, Nava, Gilroy, & Maddoux, 2012; Salmon, Browne, & Pederson, 2010; Sampson, Dasgupta, & Ross, 2014; Van Der Poel & Van De Mheen, 2006; Ware, 1999; Wilson & Neville, 2008).

METHODS

We conducted an integrative review using the methods described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005). An integrative review allows for the inclusion of both experimental and nonexperimental studies, thus creating a comprehensive review that enhances the understanding of complex phenomena (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The literature search, conducted in consultation with a medical librarian, included the search for peer reviewed articles published in English and indexed in CINAHL, PubMed, Embase, Psychinfo and sociological abstracts. The search strategy used was (marginalisa* OR marginaliza*) AND (“vulnerable population” OR “Socioeconomic Factors” OR “Healthcare Disparities” OR “Health Status Disparities” OR “Health Disparities” OR “Social Marginalization”). We modified our search strategy for sociological abstracts because of the volume of literature retrieved. Here, we used ab((‘marginaliz*’ OR ‘marginalis*’) AND (‘vulnerable population’ OR ‘socioeconomic’ OR ‘health disparity’ OR ‘social exclusion’) ) OR ti((‘marginaliz*’ OR ‘marginalis*’) AND (‘vulnerable population’ OR ‘socioeconomic’ OR ‘health disparity’ OR ‘social exclusion’) ) OR su((‘marginaliz*’ OR ‘marginalis*’) AND (‘vulnerable population’ OR ‘socioeconomic’ OR ‘health disparity’ OR ‘social exclusion’) ) as our search strategy. We first considered articles from 1990 through 2018, but given the volume of literature, we limited our search to articles from 2007 to 2018.

A total of 1,781 articles was retrieved, of which 172 were duplicates. Only those articles with “marginal”, marginality”, “marginalized/marginalised”, or “marginalization/marginalisation” in their title (N=249) were chosen for abstract review, yielding 154 articles. Because of our interest in the process of marginalization and its consequences, we chose from these 154 articles only those that provided an operational or a conceptual definition for marginalization. In this manner, 33 articles published between 2007 and 2018 were selected for inclusion in our review. Articles were summarized in a table of evidence to display the definitions provided for marginalization. These definitions were examined for similarities and differences.

Intersectionality theory served as the guiding theory for the review of definitions of marginalization. As argued by Crenshaw (1989), intersectionality theory posits that multiple marginalities are mutually inclusive and must be conceptualized together. Subsequently, Collins and colleagues defined intersectionality as a “critical insight that race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, ability and age operate not as unitary, mutually exclusive entities, but as reciprocally constructing phenomena that in turn shape complex social inequalities” (Collins, McFadden, Rocco, & Mathis, 2015, p. 2). This reciprocity occurs because the intersectional effects of multiple vulnerabilities are greater than the sum of those individual vulnerabilities (Crenshaw, 1989). Guided by this critical feminists’ perspective, three themes were developed that reflect marginalization as an insidious process through which vulnerable populations cluster at the intersections of multiple poor SDH.

FINDINGS

The definitions of marginalization used across the period under study reflect three themes that illustrate marginalization as a process through which certain population groups experience multiple social determinants concurrently. Thus, limiting their access to health promoting resources, while increasing their risk for poor health. These three themes include; 1) Creation of Margins, 2) Living between cultures, and 3) Creation of Vulnerabilities. [See the supplemental material for a synthesized table of evidence summarizing these themes]. The three themes are discussed below.

CREATION OF MARGINS

Central to the concept of marginalization is the creation of margins or boundaries (Hall et al., 1994; Mohammed, 2006). Margins serve as barriers and connections between an individual and the environment (Koci et al., 2012). Understanding the process of marginalization requires the exploration of the factors that create, define, maintain and enforce those margins (Vasas, 2005; Wilson & Neville, 2008). The earliest conceptual definition of marginalization referred to the “process through which persons are peripheralized based on their identities, associations, experiences and environment”(Hall et al., 1994, p.25). This definition illustrates marginalization as a process and identifies factors that push certain people to the periphery of society (Burman & McKay, 2007; Goodman, 2007; Hall & Carlson, 2016; Wilson & Neville, 2008). This process of being pushed to the periphery creates barriers to mainstream society. For instance, marginalization may refer to a systematic process where persons are pushed away from economic, sociopolitical and cultural participation (Sharma, 2014). Implicit in this phenomenon is power and dominance over others, the ability of a select group to exert sociopolitical, economic and psychological control over others (Meleis & Im, 1999). For instance, psychosocial and behavioral interactions within a community depend on one’s position in society in relation to the dominant culture. That is, individuals who are excluded from meaningful and equitable distribution of resources in society have less power and voice (Benner & Wang, 2015; Grineski, 2009). This interaction is influenced by disparities in income, occupation, education, race, gender role norms, and residential location (Havranek et al., 2015). These factors facilitate the creation of margins and result in social stratification, which renders the “out-group” as less powerful, inconsequential and excluded from mainstream resources (Hall et al., 1994; Hall, 1999; Mohammed, 2006).

Margins create the physical, emotional and psychological boundaries experienced by people during their interactions in society (Koci et al., 2012). For example, in an abusive relationship, the abuser exerts psychological control over the abused. This control creates both an emotional and a psychological barrier to the outside world. Like the physical and imaginary boundary that exists between the abuser and the abused, the boundary between the rich and the poor, developed and impoverished communities, the oppressor and the oppressed serves to deprive the vulnerable group from full access to mainstream resources. Boundary maintenance and its enforcement divides political and socioeconomic resources unevenly, and facilitates the disproportionate distribution of improvements in healthcare services across gender, race, sexual orientation, culture and geographic regions (Salmon et al., 2010; Sampson et al., 2014).

LIVING BETWEEN CULTURES

Living between cultures is another theme that links marginalization to SDH. While the boundary or margin serves as a partition between the dominant and the peripheralized group, incomplete integration into either group results in life between cultures. Incomplete integration creates the situation where an individual or a group relinquishes characteristics of the parent culture to connect with the dominant society, yet fails to do so (Debrosse, de la Sablonniere, & Rossignac-Milon, 2015; Llamas & Morgan Consoli, 2012; Muñoz-Laboy et al., 2017). For example, a mixed raced person may be discriminated against because he or she is not an exact fit with either of his/her parents’ race. The result is life on the periphery of society, on the verge of social exclusion (Bhugra, Leff, Mallett, Morgan, & Zhao, 2010). This lack of complete acceptance into neither the dominant nor the vulnerable group can result in the intersection of multiple vulnerabilities: a state often characterized by economic disadvantage and discrimination (Strom, Thoresen, Wentzel-Larsen, Sagatun, & Dyb, 2014). The individual exists at the fringes of inclusion and exclusion (Aamland, Werner, & Malterud, 2013). At this position, the individual lacks access to the privileges allowed to members of neither the mainstream society nor “out-group” (Gutierrez, Franco, Gilmore Powell, Peterson, & Reid, 2009). Persons existing between cultures also experience intragroup marginality – a variant of marginalization, which refers to the perceived interpersonal distancing exhibited by members of the heritage when acculturated individuals exhibit characteristics of the dominant culture (Cano, Castillo, Castro, de Dios, & Roncancio, 2014; Castillo, Conoley, Brossart, & Quiros, 2007; Llamas & Morgan Consoli, 2012).

The condition of living between cultures is evident in the way of life of most immigrants, migrant farm workers, mixed race couples and other vulnerable groups. These individuals cluster in residential areas notable for limited employment and educational opportunities as well as affordable healthcare services (Havranek et al., 2015). Not only are these individuals faced with the stark reality of thriving in a low-resourced community, but they also experience both a physical and a psychological struggle for survival along the intersections of multiple vulnerabilities. For instance, vulnerable populations who exist at these intersections may struggle with a constant need to choose between routine health checks and paying monthly rent or refilling medications and nutritious foods. These struggles make it difficult for vulnerable groups to adjust to the mainstream society.

CREATION OF VULNERABILITIES

The cumulative effect of both the creation of margins and living between cultures is the creation of vulnerabilities. Vulnerability refers to a state of being exposed to and unprotected from health damaging environment (Hall et al., 1994; Mohammed, 2006). Vulnerability captures the complex interaction between the sociopolitical, economic, structural, cultural and interpersonal circumstances that pose both physiological and/or psychological threat to an individual (Gutierrez et al., 2009; Krohn, Schmidt, Lizotte, & Baldwin, 2011).

Marginalization is associated with social exclusion of undesirable individuals (Kealy & Ogrodniczuk, 2010). Thus, relegating a select group to a powerless position that restricts survivability (Adamshick, 2010). Marginalization is also associated with structural and social inequality (Cleary, Horsfall, & Escott, 2014; Díaz-Venegas, 2014; Krohn et al., 2011; Sampson et al., 2014) which increase the risk of poor health outcomes. That is marginalization also refers to a process through which persons are impacted differentially by structural and social inequity (Gerlach, 2015). Social inequality results in intentional rejection with demotion to a powerless position in society: which severely restricts survivability (Albrecht, Devlieger, & Van Hove, 2009; Betts & Hinsz, 2013; Gerlach, 2015; Lynam & Cowley, 2007; Priebe et al., 2012; Stevens, Hall, & Meleis, 1992). This act of rejection is perpetuated through ideologies such as racism, classism, colonialism, and constrictive gender role norms perpetuated through mechanisms such as implicit bias, bullying, stigmatization (Van Den Tillaart, Kurtz, & Cash, 2009), scapegoating, residential segregation, mass incarceration, inequity in pay rates, disparities in unemployment rates, and lack of access to affordable healthcare services (Betts & Hinsz, 2013; Eliassen, Melhus, Hansen, & Broderstad, 2013). Thus, resulting in the restriction of participation in the use of social and health care services (Lous, Friis, Vinding, & Fonager, 2012; Priebe et al., 2012; Sanders & Munford, 2007). The cumulative outcome of these conditions is increased economic burden that results in increased vulnerability among the marginalized group. That is, the victims of marginalization are deprived of health promoting SDH such as social support and access to care (Caserta, Pirttila-Backman, & Punamaki, 2016).

Marginalization leads to a social, economic, physical, psychological, and physiological deterioration that eventually results in poor health outcome. For instance, Ware identified four processes in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (Eliassen et al., 2013; Ware, 1999). First, role constriction decreases the ability of chronically ill persons to fulfill their social function. Secondly, de-legitimization or disconfirming of the experience of being ill occurs. Impoverishment follows when expenses increase and income decrease. These processes then cause social isolation of the chronically ill individual (Eliassen et al., 2013; Ware, 1999). Similarly, through socioeconomic deprivation and the disproportionate distribution of access to healthcare services, marginalization sets into motion a systemic condition of deterioration among vulnerable individuals suffering from a chronic disease.

Marginalization is particularly problematic in conditions requiring lifestyle change. For example, a newly diagnosed cancer patient who loses his/her health insurance may spend his/her life savings on treatments. Cancer treatments may require that the patient adopt new lifestyle habits so that he or she may optimally benefit from treatments. These situations are often socially challenging (e.g. severe fatigue that limits the ability to work, dietary restrictions that may have moderate to severe physiological consequences and loss of hair in female cancer patients that may affect their self-confidence). While the individual’s expenses increase, income decreases, and both the treatment and its side effects cause a change in lifestyle. This lifestyle change pushes the individual further to a position in society with higher restrictive access to needed resources. This change in access causes increased health care needs with a decline in accessibility and affordability of basic needs (e.g. food, water and affordable housing), in addition to healthcare services. This process may progress into a systemic cascade of deterioration with increased health care burden and poor health outcome.

THE LINK BETWEEN SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH AND MARGINALIZATION

Exploring the properties of marginalization (e.g. intermediacy, differentiation and exteriority) reveals health implications as well as social ramifications that are defined by the magnitude of a person’s marginality. The factors that determine this magnitude are the principal components of SDH. While the process of marginalization pushes a person to a specific social position, SDH focuses on the built and social environment and the resources available to prevent or fight disease. These resources (e.g. education, income and quality of residential environment) in conjunction with gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity are factors that intersect to define an individual’s health. Therefore, we contend that social position serves as the link between marginalization and SDH.

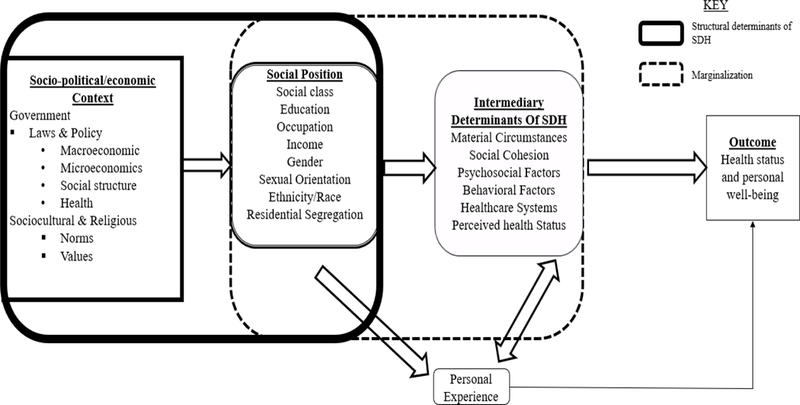

We conceptualize social position as the central concept of both SDH and Marginalization (see Figure 1). It is the position to which persons are relegated based on their experiences, identity and environment. Because resources at this social position are disproportionately distributed, they result in differential life conditions that lead to differential health outcomes among population groups. The themes (i.e., Creation of Margins, living between cultures and Creation of Vulnerabilities) discussed above highlight this link between SDH and marginalization. Not only do these themes focus on the systemic processes implicit at a specific social position that determines health, but they also focus on the disparities that exist in the environment and the inequities that determine the distribution of health promoting resources.

Figure 1: Conceptual model of the link between social determinants of health and marginalization.

illustrates social position as the relationship between social determinants of health (SDH) and marginalization. Socio-political, economic, cultural and religious influences accentuate the marginalization of certain individuals. Once marginalized, an individual exists at a position in society with limited access to affordable resources that limits survivability.

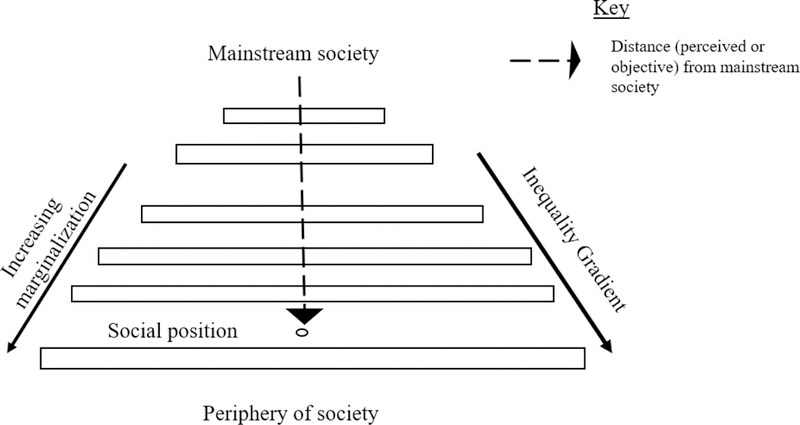

During marginalization, there is an increase in both the perceived and objective distance to resources such that there is differential access to, and inequity in education, employment, housing and affordable healthcare services (see Figure 2). For instance, an ethno-epidemiologic study that examined social, structural and environmental factors that influence periods of injection cessation among marginalized youth who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada found that access to harm reduction youth-focused services, provision of housing and social support were important factors that influenced injection cessation (Boyed et al, 2017). A participant in this study reported his residential location in Vancouver’s inner-city drug scene limited his ability to escape the drug scene. Marginalized individuals also experience differential treatment based on gender, sexual orientation, race and social class. This treatment creates differences in intermediary determinants that shapes an individual’s health status and personal well-being. This phenomenon results in different firsthand experiences and inequity in available resources, which eventually result in increased risk for poor health outcome among the marginalized. As marginalization increases, perceived and objective distance to resources increases as well, thus, increasing the inequity in health promoting SDH. This inequity in health promoting SDH limits the marginalized individual’s choices to resources that facilitates the management of chronic illness.

Figure 2: Conceptual framework of social position in relation to mainstream society.

Disparities and inequity in health promoting resources increase with increased perceived and objective distance from mainstream society.

The current conceptualization of SDH lacks a critical focus on the personal experience that results from an individual’s interaction with society and the environment. When marginalization is situated within the framework of SDH, as shown in Figure 1, it allows us to critically appraise the firsthand experiences of vulnerable populations. This critical perspective identifies intermediary determinants of SDH as a component of marginalization and highlights personal experience as an outcome of the intersectional effect of the components of social position and the individual’s interaction with the environment. For instance, in a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators in treating drug use among Israeli mothers, Gueta (2017) found that factors such as motherhood, immigration, poverty and lack of support intersect with participants’ identity as drug users to limit their use of social services despite their awareness for the need for the services (Gueta, 2017). Thus, this model allows us to critically examine the power dynamics implicit to SDH that are involved in the construction of social structures, social position and how those dynamics create conditions of marginality.

Marginalization situated within the framework of SDH also invokes the concept of health disparities and inequity in access to resources. It reveals the relationship between societal powers, social inequity and health disparity. By drawing into focus the concept of disparities and equity, we can identify terms such as social exclusion as synonymous with marginalization, and ostracism, and rejection and loneliness as consequences of marginalization. Individuals who are pushed aside – marginalized or socially excluded – are in a position with limited protection and have the highest risk of poor health outcomes. Hence, marginalization may result in poor self-esteem, lack of self-efficacy, stigmatization and homelessness.

Marginalization conceptualized within the framework of SDH does not only allow us to focus on the vulnerabilities of individuals; but it also expands our critical lens to include their resilience. For instance, a critical appraisal of the properties of marginalization (e.g. exteriority) allows us to assess person-specific factors for targeted interventions. By the application of this framework as shown in Figure 1, we bring into focus the personal needs, values, priorities, and the factors that are significant in the daily lives of marginalized individuals. It allows us to explore their experiences to identify how they cope with stress, adapt to social change and the operational mechanisms underlying their relationships.

Meleis (personal communication, 2015), one of the primary theorists of marginalization, describes how world events and laws determine which populations will be marginalized. For example, in the U.S., after the terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001, laws such as immigration reform and the implementation of certain social policies served to marginalize certain groups of people. This resulted in the labeling of certain populations as “others” and caused some to cluster at certain areas in society with poor SDH. For instance, populations such as the homeless, black men, immigrants, refugees, the unemployed, abused women, and the chronically ill are marginalized; hence, they experience limited access to health care services, education and other basic needs (Havranek et al., 2015; Meleis & Im, 1999; Venkatapuram et al., 2010). This reality is exemplified in the high prevalence of chronic drug use, lack of affordable housing, and extreme poverty among this group.

Lastly, human interactions within the environment (social and built environment) set the individual on a path towards systemic physiologic and social deterioration that lead to poor health outcomes. This process of deterioration results from a “pattern of disparate risk of social categorization that makes marginalization a major health concern” (Hall & Carlson, 2016, p.202). Therefore, by adapting and expanding Hall’s definition of marginalization to include SDH, we contend that marginalization is a process through which persons are pushed to a position in society where both their perceived and objective distance to basic resources; including healthcare and social services, employment, quality education, food and water lead to an increased risk for poor health outcome. For instance, a 43-year-old African-American single mother of two school age children, who works for minimum wage and suffers from chronic heart failure (HF) is marginalized. Not only is she concerned about her lack of resources required to adhere to her HF plan of care, but she is also burdened by her rent, utility bills, and her inability to provide for her children while managing her chronic disease. Implicit to this individual’s marginality is poverty and lack of available, accessible, and affordable healthcare plan, housing, food, social support and resources to satisfy the basic needs of her family. These vulnerabilities affect the self-efficacy required for self-care not only among HF patients, but all patients suffering from a chronic illness. While marginalization is an insidious process that may occur in a wide variety of groups, the conditions in a person’s environment that determine the choices available (limited or excess opportunities) define the illness experience.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE & FUTURE RESEARCH

Marginalization conceptualized in the context of SDH has multiple implications for research and practice. Disparities in marginality among individuals partly explain differences in health and the quality of life among Americans (Havranek et al., 2015). For instance, evidence suggest that both the experience and the perception of marginalization are linked to poor health through stress, anxiety, depression, occupational injuries and limited access to healthcare services (Fleming, Villa-Torres, Taboada, Richards, & Barrington, 2017). Therefore, the reduction of health disparities to promote health equity requires researchers and clinicians to conceptualize patient vulnerabilities in the framework of their personal needs and daily realities. Thus, the proposed definition situates marginalization in the framework of SDH and offers a lens through which vulnerable persons and groups can be studied. It allows both clinicians and researchers to conceptualize the proximal causes of their patients’ disease process, which promotes respectful interactions that account for each person’s reality. The novelty of this perspective lies in the fact that, viewing persons and health from the standpoint of margins highlights the interface between the person and the environment and aids in developing targeted interventions that go beyond hospital walls. Debatably, hospitals have become a controlled experimental system where the conditions under which patients are treated are nothing like the real world. Hence, discharge plans created without considering the person’s environmental and social circumstances often fail to produce the expected outcome.

Placing marginalization in the framework of SDH allows researchers to expand their critical lens of inquiry to observe how persons interact with their environment. This perspective highlights the individual’s resilience, personal agency, family support and the unique ways through which marginalized individuals navigate and adapt to their environment. The identification of these properties through which marginalized persons thrive provides opportunities for targeted interventions. For instance, a pregnant mother diagnosed with HIV, started on antiretroviral therapy and supported by her family may suffer a feeling of stigmatization because of her disease. Yet, this mother experiences a buffering effect from her family and support group, so she may not internalize this aspect of marginalization, thereby, lessening the impact. The family and social support of this individual must be central in the development of her discharge plan of care. It is imperative that researchers and clinicians identify these protective factors to be used as targets for intervention.

Conceptualizing SDH from the standpoint of margins also highlights the structural forces that influence marginalization. It explains why underdeveloped neighborhoods with residents who are extremely underserved and impoverished can exist next to developed ones. This critical lens explains the structural and social forces that cause disparities in health outcomes among neighborhoods and identifies these factors for targeted interventions through policy; hence, shifting the blame away from vulnerable groups and individuals.

GLOBAL IMPLICATIONS OF MARGINALIZATION

The proposed framework (Figure 1) also has global implications. It charges us to dispel the myth that marginalized “third world” nations need to be “saved” by developed Western Nations. Rather, it admonishes us to join in the development of their human resources and infrastructure for total liberation. This framework challenges the status quo where “inquiry and interventions” move only through hierarchical power; hence, reduces marginalized nations into entities that need help and development without recognizing both their natural and human resources (Hall et al., 1994; Mohammed, 2006). We recognize that dichotomies such as “first world” and “third world” countries may help illustrate certain health patterns and how to respond to outbreaks; yet, they also prevent us from recognizing the socio-political forces that constructed those dichotomies (Meleis & Im, 1999), forces such as the legacy of the slave trade and eurocentrism.

Furthermore, integrating marginalization into the perspective of SDH charges us to transcend marginalization in our research and practice. To transcend marginalization is to create novel interventions with a consideration for developing countries. It also charges developing nations to not only recognize the changes occurring in their populations but also the sociocultural and environmental factors that affect health. These challenges require the development of sustainable interventions to meet global healthcare needs. For instance, the predominant disease burden of many countries is shifting from communicable to chronic diseases (Doku, 2017). It is imperative that stakeholders such as the WHO, local governments, health care providers and researchers invest in understanding the influence of marginalization on chronic disease patterns within countries experiencing these shifts in disease burdens. In this manner, country-specific interventions that are culturally sensitive can be developed.

LIMITATIONS

The selection of the articles used in this review introduces a limitation because, although the approach for selection and inclusion is methodologically appropriate, we recognize that, it does not correct for publication bias. Therefore, certain studies that might have been of immense importance to the review may have been missed. As seen in this article, we also recognize that marginalization is a dynamic phenomenon. Therefore, this proposed conceptual framework and definition of marginalization is not considered absolute. The definition is expected to initiate dialogue within the nursing profession and perhaps change the paradigm of care, particularly during the transition of patients from hospitals to homes in marginalized communities. Our hope is that this article adds a voice to the movement raising awareness on the effects of social and environmental factors on chronic diseases among marginalized individuals.

CONCLUSION

In sum, marginalization in nursing has been referred to as an abstract process through which people and groups have limited access to power, social and political resources and are subjected to differential treatments because of their position in society (Vasas, 2005). The results of our review show evidently that marginalization can result from laws enacted by government and enforced through policies at the local level. Marginalization can also result from the sociocultural interaction between groups that hold the power to determine right from wrong and those who do not. It may also result from the interaction between privileged and impoverished groups. We believe that the description presented here illustrates that marginalization is not an abstract idea. It is a phenomenon that is as concrete as the way of life of a migrant farm worker in southern Georgia who lives in a dilapidated trailer park, lacks employee sick time benefits, and suffers a constant fear of immigration officers due to racism and prejudice. To conceptualize marginalization as an abstract idea is to ignore the concrete socioeconomic and political power strictures that determine the conditions in which people live. It is only by recognizing the reality of these forces, the mechanism through which they are perpetuated and their effects on vulnerable populations that interventions can be targeted to improve health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

The primary author is funded by a T32 from the National institute of nursing research under award number T32NR009356 through the NewCourtland Center for Transitions and Health.

Contributor Information

Foster Osei Baah, NewCourtland Center for Transitions & Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Anne M. Teitelman, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Barbara Riegel, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- Aamland A, Werner EL, & Malterud K (2013). Sickness absence, marginality, and medically unexplained physical symptoms: A focus-group study of patients’ experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 31(2), 95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamshick PZ (2010). The lived experience of girl-to-girl aggression in marginalized girls. Qualitative Health Research, 20(4), 541–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ, & Van Hove G (2009). Living on the margin: Disabled iranians in belgian society. Disability & Society, 24(3), 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson EP (1995). Marginality: Concept or reality in nursing education? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 21(1), 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg JH, Chiswell M, & Toumbourou JW (2011). Use of the program explication method to explore the benefits of a service for homeless and marginalized young people. Public Health Nursing, 28(2), 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Wang Y (2015). Adolescent substance use: The role of demographic marginalization and socioemotional distress. Developmental Psychology, 51(8), 1086–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethune-Davies P, McWilliam CL, & Berman H (2006). Living with the health and social inequities of a disability: A critical feminist study. Health Care for Women International, 27(3), 204–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts KR, & Hinsz VB (2013). Group marginalization: Extending research on interpersonal rejection to small groups. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(4), 355–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D, Leff J, Mallett R, Morgan C, & Zhao J (2010). The culture and identity schedule a measure of cultural affiliation: Acculturation, marginalization and schizophrenia. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 56(5), 540–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MB, & Tedrick T (1993). Outdoor leisure involvements of black older Americans: An exploration of ethnicity and marginality. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 17(3), 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Burman ME, & McKay S (2007). Marginalization of girl mothers during reintegration from armed groups in Sierra Leone. International Nursing Review, 54(4), 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Castillo LG, Castro Y, de Dios MA, & Roncancio AM (2014). Acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among Mexican and Mexican American students in the U.S.: Examining associations with cultural incongruity and intragroup marginalization. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, 36(2), 136–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta TA, Pirttilä-Backman AM, & Punamāki RL (2016). Stigma, marginalization and psychosocial well-being of orphans in Rwanda: Exploring the mediation role of social support. AIDS Care, 28(6), 736–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Conoley CW, Brossart DF, & Quiros AE (2007). Construction and validation of the intragroup marginalization inventory. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(3), 232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Horsfall J, & Escott P (2014). Marginalization and associated concepts and processes in relation to mental health/illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(3), 224–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JC, McFadden C, Rocco TS, & Mathis MK (2015). The problem of transgender marginalization and exclusion: Critical actions for human resource development. Human Resource Development Review, 14(2), 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Coumans M, Knibbe RA, & van de Mheen D (2006). Street-level effects of local drug policy on marginalization and hardening: An ethnographic study among chronic drug users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 38(2), 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumans M, & Spreen M (2003). Drug use and the role of homelessness in the process of marginalization. Substance Use & Misuse, 38(3–6), 311–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), art 8. Retrieved from https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf [Google Scholar]

- Debrosse R, de la Sablonniere R, & Rossignac-Milon M (2015). Marginal and happy? The need for uniqueness predicts the adjustment of marginal immigrants. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54(4), 748–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Venegas C (2014). Identifying the confounders of marginalization and mortality in Mexico, 2003–2007. Social Indicators Research, 118(2), 851–875. [Google Scholar]

- DiNapoli PP, & Murphy D (2002). The marginalization of chronically ill adolescents. Nursing Clinics of North America, 37(3), 565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson JE, & Struthers R (2005). Indigenous women’s voices: Marginalization and health. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 16(4), 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doku D (2017). Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet, 390(10100), 1151–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliassen BM, Melhus M, Hansen KL, & Broderstad AR (2013). Marginalisation and cardiovascular disease among rural Sami in northern Norway: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 13, 522–2458-13–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming PJ, Villa-Torres L, Taboada A, Richards C, & Barrington C (2017). Marginalisation, discrimination and the health of Latino immigrant day labourers in a central North Carolina community. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 527–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach AJ (2015). Sharpening our critical edge: Occupational therapy in the context of marginalized populations. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy/Revue Canadienne D’Ergotherapie, 82(4), 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S (2007). Piercing the veil: The marginalization of midwives in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 65(3), 610–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grineski SE (2009). Marginalization and health: Children’s asthma on the Texas-Mexico border. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 29(5/6), 287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gueta K (2017). A qualitative study of barriers and facilitators in treating drug use among israeli mothers: An intersectional perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 187, 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez MA, Franco LM, Gilmore Powell K, Peterson NA, & Reid RJ (2009). Psychometric properties of the acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans -- II: Exploring dimensions of marginality among a diverse Latino population. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31(3), 340–356. [Google Scholar]

- Gyarmathy VA, & Neaigus A (2011). The association between social marginalisation and the injecting of alcohol amongst IDUs in Budapest, Hungary. International Journal of Drug Policy, 22(5), 393–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JM, & Carlson K (2016). Marginalization: A revisitation with integration of scholarship on globalization, intersectionality, privilege, microaggressions, and implicit biases. Advances in Nursing Science, 39(3), 200–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JM (1999). Marginalization revisited: Critical, postmodern, and liberation perspectives. Advances in Nursing Science, 22(2), 88–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JM, Stevens PE, & Meleis AI (1994). Marginalization: A guiding concept for valuing diversity in nursing knowledge development. Advances in Nursing Science, 16(4), 23–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, . . . Council Epidemiology Prevention. (2015). Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation, 132(9), 873–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich P, Trogdon J, & Khavjou M (2011). AHA policy statement: Forecasting the future of cardiovasular disease in the United States. Circulation, 123, 933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kealy D, & Ogrodniczuk JS (2010). Marginalization of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 16(3), 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koci AF, McFarlane J, Nava A, Gilroy H, & Maddoux J (2012). Informing practice regarding marginalization: The application of the koci marginality index. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(12), 858–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn MD, Schmidt NM, Lizotte AJ, & Baldwin JM (2011). The impact of multiple marginality on gang membership and delinquent behavior for Hispanic, African American, and white male adolescents. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 27(1), 18–42. [Google Scholar]

- Llamas JD, & Morgan Consoli M (2012). The importance of familia for Latina/o college students: Examining the role of familial support in intragroup marginalization. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(4), 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lous J, Friis K, Vinding AL, & Fonager K (2012). Social marginalization reduces use of ENT physicians in primary care. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 76(3), 370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam MJ, & Cowley S (2007). Understanding marginalization as a social determinant of health. Critical Public Health, 17(2), 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Meleis AI, & Im E (1999). Transcending marginalization in knowledge development. Nursing Inquiry, 6(2), 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, & Croft JB (2005). State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation, 111(10), 1233–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed SA (2006). (Re)examining health disparities: Critical social theory in pediatric nursing. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 11(1), 68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Laboy M, Martínez O, Guilamo-Ramos V, Draine J, Garg K, Levine E, & Ripkin A (2017). Influences of economic, social and cultural marginalization on the association between alcohol use and sexual risk among formerly incarcerated Latino men. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 19(5), 1073–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S, Matanov A, Schor R, Strassmayr C, Barros H, Barry MM, . . . Gaddini A (2012). Good practice in mental health care for socially marginalised groups in Europe: A qualitative study of expert views in 14 countries. BMC Public Health, 12, 248–2458-12–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon A, Browne AJ, & Pederson A (2010). ‘Now we call it research’: Participatory health research involving marginalized women who use drugs. Nursing Inquiry, 17(4), 336–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson L, Dasgupta K, & Ross NA (2014). The association between socio-demographic marginalization and plasma glucose levels at diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Diabetic Medicine, 31(12), 1563–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J, & Munford R (2007). Speaking from the margins: Implications for education and practice of young women’s experiences of marginalisation. Social Work Education, 26(2), 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M (2014). Developing an integrated curriculum on the health of marginalized populations: Successes, challenges, and next steps. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(2), 663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens PE, Hall JM, & Meleis AI (1992). Examining vulnerability of women clerical workers from five ethnic/racial groups. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 14(6), 754–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom IF, Thoresen S, Wentzel-Larsen T, Sagatun A, & Dyb G (2014). A prospective study of the potential moderating role of social support in preventing marginalization among individuals exposed to bullying and abuse in junior high school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(10), 1642–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Tillaart S, Kurtz D, & Cash P (2009). Powerlessness, marginalized identity, and silencing of health concerns: Voiced realities of women living with a mental health diagnosis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 18(3), 153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Poel A, & Van De Mheen D (2006). Young people using crack and the process of marginalization. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 13(1), 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Vasas EB (2005). Examining the margins: A concept analysis of marginalization. Advances in Nursing Science, 28(3), 194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatapuram S, Bell R, & Marmot M (2010). The right to sutures: Social epidemiology, human rights, and social justice. Health and Human Rights, 12(2), 3–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC (1999). Toward a model of social course in chronic illness: The example of chronic fatigue syndrome. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 23(3), 303–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, & Knafl K (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, & Neville S (2008). Nursing their way not our way: Working with vulnerable and marginalised populations. Contemporary Nurse, 27(2), 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health Retrieved from http://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.