Abstract

Background:

Childhood risk factors are associated with elevated inflammatory biomarkers in adulthood, but it is unknown whether these risk factors are associated with increased adult levels of the chronic inflammation marker soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR).

We aimed to test the hypothesis that childhood exposure to risk factors for adult disease is associated with elevated suPAR in adulthood and to compare suPAR with the oft-reported inflammatory biomarker C-reactive protein (CRP).

Methods:

Prospective study of a population-representative 1972–73 birth cohort; the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study observed participants to age 38 years.

Main childhood predictors were poor health, socioeconomic disadvantage, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), low IQ, and poor self-control. Main adult outcomes were adulthood inflammation measured as suPAR and high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP).

Results:

Participants with available plasma samples at age-38 were included (N=837, 50.5% male). suPAR (mean 2.40 ng/mL; SD 0.91) was positively correlated with hsCRP (r 0.15, p<.001).

After controlling for sex, BMI, and smoking, children who experienced more ACEs, lower IQ, or had poorer self-control showed elevated adult suPAR.

When the five childhood risks were aggregated into a Cumulative Childhood Risk index, and controlling for sex, BMI, and smoking, Cumulative Childhood Risk was associated with higher suPAR (b 0.10; SE 0.03; p=.002). Cumulative Childhood Risk predicted elevated suPAR, after controlling for hsCRP (b 0.18; SE 0.03; p<.001).

Conclusions:

Exposure to more childhood risk factors was associated with higher suPAR levels, independent of CRP. suPAR is a useful addition to studies connecting childhood risk to adult inflammatory burden.

Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences, self-control, inflammation, physical health, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

A major public-health challenge is to extend healthspan (i.e., the years lived free of disease and disability) in the context of an expanding aging population (Burch et al., 2014; Harper, 2014). Because of evidence that the basic foundations for lifelong health are constructed in the early years of life (Power, Kuh, & Morton, 2013), efforts to extend healthspan are no longer confined to gerontology but also need to involve expertise from health professionals specializing in childhood and adolescence (Moffitt, Belsky, Danese, Poulton, & Caspi, 2017). Life-course research has drawn attention to several childhood risk factors that may compromise lifelong health (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011), among them poor health, socioeconomic disadvantage (Power et al., 2013), adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (Felitti et al., 1998), low IQ (Calvin et al., 2011, 2017), and poor self-control (Moffitt et al., 2011).

Markers of inflammation have played an important role in this research on the developmental origins of adult disease. In particular, given their predictive value for age-related disease and mortality, markers of inflammation have been used as intermediate endpoints for studies of early-life risk factors’ effects on adult health (Danese & Baldwin, 2017; Danese & McEwen, 2012). In addition, evidence that immune response is dysregulated in many psychiatric disorders—including depression, schizophrenia and autism—is prompting new hypotheses about the etiology of psychiatric disorders as well as motivating research into the possibility that psychiatric diseases might respond to anti-inflammatory medications (Friedrich, 2014). C-reactive protein (CRP) has been commonly used as the global measure of systemic inflammation both in clinical practice and in life-course research (Ridker, 2003); however, CRP is quite sensitive to short-term influences, e.g., small acute infections. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) is a newer biomarker of inflammation that likely captures different aspects of systemic inflammation than CRP (Desmedt et al., 2017), although CRP and suPAR are positively correlated (Lyngbæk et al., 2013).

suPAR is the soluble form of uPAR, a membrane-bound receptor that is expressed on immune and endothelial cells and involved in several cellular processes, including adhesion, differentiation, proliferation, and migration (Blasi & Carmeliet, 2002). Immune and pro-inflammatory conditions increase the expression and cleavage of uPAR (Dekkers et al., 2000; Ostrowski et al., 2005). The resulting suPAR is a stable circulating molecule with intrinsic chemotactic properties (Resnati et al., 2002), and the level of suPAR is thought to reflect the overall immune activity of an individual (Desmedt et al., 2017). suPAR levels are elevated across a wide range of diseases (Rasmussen et al., 2016), including cardiovascular disease (Persson et al., 2014), type 2 diabetes (Guthoff et al., 2017), cancer (Tarpgaard et al., 2015), renal disease (Hayek et al., 2015), and infections (Donadello et al., 2014). In addition, suPAR predicts mortality, both in the general population and in patient populations (Eugen-Olsen et al., 2010; Rasmussen et al., 2016). However, to date suPAR has not been incorporated into studies of early-life origins of poor late-life health, and it is relatively unknown in pediatric medical practice or research.

We investigated the childhood developmental origins of elevated chronic inflammation by analyzing suPAR in adulthood in a population-representative birth cohort that gathered multiple prospective measures of childhood risk. We had three broad goals. First, we investigated how suPAR relates to other concurrent health measures in adulthood. Second, we studied how childhood risk factors are related to elevated suPAR in adulthood. Third, as CRP and suPAR may reflect different aspects of inflammation, we also compared the two biomarkers, and tested a combination of the two in relation to childhood risks.

METHODS

Study design and population

Participants are members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal investigation of health and behavior in a representative birth cohort. Participants (N=1,037; 91% of eligible births; 52% male) were all individuals born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand (NZ), who were eligible based on residence in the province and who participated in the first assessment at age 3 years. The cohort represents the full range of socioeconomic status (SES) in the general population of NZ’s South Island and matches the NZ National Health and Nutrition Survey on key adult health indicators (e.g., body mass index (BMI), smoking, GP visits). Participants are primarily white; fewer than 7% self-identify as having partial non-Caucasian ancestry, matching South Island demographics (Poulton, Moffitt, & Silva, 2015). Assessments were carried out at birth and ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, and the most recent data collection was completed in December 2012 at age 38 years, when 95% (N=961) of the 1,007 participants still alive took part. At each assessment, each participant is brought to the research unit for a full day of interviews and examinations. Laboratory work was performed through June 2017. Blood from participants of Maori ancestry was not transported to Duke University for cultural reasons, and plasma samples were not available for participants who did not provide blood or due to phlebotomy or defrost cycle problems. The final study population comprised 837 participants. Living Study members who did not have suPAR data in adulthood did not differ from those who did have available suPAR data in terms of their childhood socioeconomic status (t=.65, p=.52), number of Adverse Childhood Experiences (t=1.58, p=.11), IQ (t=1.66, p=.10), or self-control (t=.94, p=.35), but they did have poorer childhood health (t=2.00, p=.05). The Otago Ethics Committee approved each phase of the study and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Inflammatory biomarkers and white blood cell count

Venepuncture at age-38 was performed between 4.15–4.45 pm for all participants.

Plasma suPAR (ng/mL) was analyzed with the suPARnostic AUTO Flex ELISA (ViroGates A/S, Birkerød, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP, mg/L) was measured on a Modular P analyzer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) using a particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay.

In addition, we assayed two additional markers of inflammation. Plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6, pg/mL) was measured on a Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA) SpectraMax plus 384 plate reader using R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) Quantikine High sensitivity ELISA kit HS600B according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma fibrinogen (g/L) was measured on a Sysmex CA-1500 or CS2100i using a fully automated cap piercing coagulation analyzer (Mahberg, Germany).

White blood cells (WBCs), including total WBCs, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils, were measured by flow-cytometry using a semiconductor laser to produce forward and lateral scattered light. All WBC types were reported as x109/L.

Clinical characteristics

BMI (kg/m2), body temperature (°F), and use of anti-inflammatory medication (including statins, respiratory or systemic steroids, prophylactic aspirin, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory, anti-gout, or anti-rheumatic drugs) were recorded at age-38.

Week of menstrual cycle (days since last period began) was registered for female participants.

Smoking was reported at age-38, grouping the participants into four groups: non-smoker, smoking <10 cigarettes/day, 10–19 cigarettes/day, or ≥20 cigarettes/day.

Childhood risk factors and adult health correlates

Childhood risk factors, including poor health, socioeconomic disadvantage, ACEs, low IQ, and poor self-control, are described in Table 1. These risk factors have been reported in previous publications. In addition, we also report about health and functional correlates of inflammation at age-38, including self-reported health, an index of Biological Age, an index of facial aging, and telomere length (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of study measures

| Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Childhood measures | |

| Childhood health | Childhood health was measured from a panel of biomarkers and clinical ratings taken at assessments from birth to age 11 years (Belsky, Caspi, Israel, et al., 2015), including motor development (at ages 3, 5, 7, and 9 years), overall health (at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 years; rated by two Unit staff members based on review of birth records and assessment dossiers including clinical assessments and reports of infections, diseases, injuries, hospitalizations, and other health problems collected from children’s mothers during standardized interviews), body mass index (at ages 5, 7, 9, and 11 years), tricep and subscapular skinfold thicknesses (at ages 7 and 9 years), and, finally, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC; at ages 9 and 11 years). To calculate the childhood health measure, assessments were standardized to have mean = 0 and SD = 1 within age- and sex-specific groups. Cross-age scores for each measure were then computed by averaging standardized scores across measurement ages. The final childhood health score was calculated by taking the natural log of the average score across all measures, resulting in a normally distributed childhood health index. High scores indicate poor health. |

| Childhood socioeconomic status | The socioeconomic statuses of cohort members’ families were measured using a 6-point scale that assessed parents’ occupational statuses, defined based on average income and educational levels derived from the New Zealand Census. The highest occupational status of either parent was averaged across the childhood assessments (Poulton et al., 2002). |

|

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) |

The measured ACEs correspond to the 10 subcategories of childhood adversity introduced by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (“,Center for Disease Control and Prevention,” n.d.;

Felitti et al., 1998). Three types of abuse (emotional, physical, sexual), five types of household challenges (household partner violence, household substance abuse, mental illness in household, loss of a parent (parental death, separation, or divorce), incarceration of a family member), and two types of neglect (emotional, physical). Prospective ACE counts were generated from archival Dunedin Study records collected at biennial assessments from ages 3 to 15 years, as previously described (Reuben et al., 2016). The records included the following: social service contacts; structured notes from assessment staff who interviewed Study children and their parents; structured notes from pediatricians and psychometricians who observed mother-child interactions at the research unit; structured notes from nurses who recorded conditions witnessed at home visits; and notes of concern from teachers who were surveyed about the Study children’s behavior and performance. Separately, parental criminality was surveyed via postal questionnaire to the parents. |

| Childhood IQ | Middle-childhood intelligence was measured as previously described (Moffitt et al., 2011) using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised (Wechsler, 1974). The participants’ total scores were averaged over the three assessment points to represent intelligence in middle-to-late childhood. |

|

Childhood low self-control |

Children’s self-control during their first decade of life was measured using a multi-occasion/multi-informant strategy and was reported as a composite measure of overall self-control, as previously described (Moffitt et al., 2011). The composite measure of self-control includes observational ratings of children’s lack of control; parent and teacher reports of impulsive aggression; parent, teacher, and self-reports of hyperactivity; lack of persistence; inattention; and impulsivity. Furthermore, at ages 3 and 5 years, the children’s lack of control in cognitive and motor tasks was rated by examiners blinded to the children’s behavioral history. At ages 5, 7, 9, and 11 years, parents and teachers completed the Rutter Child Scale (RCS), which included items indexing impulsive aggression and hyperactivity. At ages 9 and 11 years, the RCS was supplemented with additional questions about the children’s lack of persistence, inattention, and impulsivity. At age 11 years, the children were interviewed by a psychiatrist and reported about their symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity. The 9 measures of self-control were standardized and averaged into a single composite score (M=0, SD=1). |

| Adulthood measures | |

| Self-reported health | Self-reported health was measured at age 38 years using a 5-point scale to rate the question: ‘In general, would you say your health is?’ The five options were ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’, or ‘poor’. |

| Biological Age | The cross-sectional index of Biological Age (Levine, 2013) is an algorithm for estimating “rate of senescence” based on 10 biomarkers developed with parameters from the NHANESIII dataset using the Klemera-Doubal method (Klemera & Doubal, 2006). The 10 biomarkers in the algorithm are: albumin, alkaline phosphatase, blood pressure (systolic), C-reactive protein, creatinine, cytomegalovirus IgG, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol, and urea nitrogen. As previously described in the Dunedin Study, Biological Age at the age-38 assessment ranged from 28.65 to 61.97 years (M=38.29, SD=3.22) (Belsky, Caspi, Houts, et al., 2015). |

| Facial aging | Facial aging was based on two measurements of perceived age based on facial photographs as previously described (Belsky, Caspi, Houts, et al., 2015). First, Age Range was assessed by an independent panel of 4 raters, who were presented with standardized (non-smiling) facial photographs of participants and were kept blind to their actual age. Raters used a Likert scale to categorize each study member into a 5-year age range (i.e., from 20–24 years old up to 65–70 years old). Scores for each study member were averaged across all raters (α=0.71). Second, Relative Age was assessed by a different panel of raters, who were told that all photos were of people aged 38 years old. Raters then used a 7-item Likert scale to assign a “relative age” to each study member (1=“young looking”, 7=“old looking”). Scores for each study member were averaged across all raters (α=0.72). The measure of perceived age at 38 years, facial age, was derived by standardizing and averaging Age Range and Relative Age scores. |

| Telomere length | Leukocyte DNA was extracted from blood using standard procedures (Bowtell, 1987; Jeanpierre, 1987). DNA was stored at −80°C until assayed to prevent degradation of the samples. All DNA samples were assayed for leukocyte telomere length at the same time, using a validated quantitative PCR method (Cawthon, 2002), as previously described (Shalev et al., 2014), which determines mean telomere length across all chromosomes for all cells sampled. The method involves two quantitative PCRs for each subject, one for a single-copy gene and the other in the telomeric repeat region. All DNA samples were run in triplicate for telomere and single-copy reactions, i.e., six reactions per study member. |

Cumulative Childhood Risk index

Cumulative Childhood Risk represents a count of the 5 risk factors, where 1 point was given for being in the quartile associated with highest risk for each of the five childhood risk factors investigated: poor childhood health, low childhood socioeconomic status, more adverse childhood experiences, low IQ, and low self-control.

Statistical analysis

We calculated Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients to test the associations between hsCRP or suPAR with clinical characteristics, other inflammatory biomarkers (IL-6, fibrinogen), and WBC counts.

hsCRP was not normally distributed and was log-transformed for further analyses, as commonly done in the literature (The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, 2012).

The association between childhood risk factors and hsCRP and suPAR and between hsCRP and suPAR and adult health outcomes was tested using Ordinary Least Squares regression, using continuous measures of hsCRP and suPAR. Multivariable regression analyses were adjusted for the covariates sex, BMI, and smoking, as these are the most common adjustments in research on inflammation. We report standardized regression coefficients (b) with standard errors (SEs).

To analyze the effect of childhood risk factors on adult-combined CRP and suPAR, we created four groups of individuals characterized by: i) low CRP and low suPAR (N=546, 66%), ii) high CRP and low suPAR (N=119, 14%), iii) low CRP and high suPAR (N=118, 14%), and iv) high CRP and high suPAR (N=47, 6%). For CRP, we used the established clinical cut-off of 3 mg/L to identify persons with high CRP; thus, the label ‘high CRP’ indicates hsCRP>3 mg/L (N=166, 20%). A clinical cut-off for suPAR has not yet been established, so to identify participants with high suPAR, we chose a cut-off corresponding to a similar percentage as for ‘high CRP’; thus, ‘high suPAR’ indicates suPAR>2.89 ng/mL (N=168, 20.1%). The association between childhood risk factors and the inflammation groups was tested using multinomial logistic regression. We report odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

A p<.05 was a priori designated statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS Enterprise Guide 7.11 (SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

Correlations of hsCRP and suPAR with clinical characteristics, inflammatory biomarkers, and white blood cells

Distributions of hsCRP and suPAR in the Dunedin cohort are shown in Figure S1.

High hsCRP and high suPAR were both significantly correlated with female sex, high BMI, and smoking. Of note, hsCRP was more strongly correlated with BMI than was suPAR, while suPAR was more strongly correlated with smoking than was hsCRP (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sex-adjusted correlates of hsCRP and suPAR at age 38 years in the Dunedin study

| Mean (SD) or N (%) |

hsCRPa | suPAR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | rb | p | N | rb | p | |||

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||||

| Sex (Female) | 414 (49.5%) | 830 | −0.11 | .002 | 837 | −0.16 | <.001 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 (5.3) | 828 | 0.45 | <.001 | 828 | 0.07 | .04 | ||

| Smoking | 173 (20.7%) | 829 | 0.07 | .04 | 836 | 0.36 | <.001 | ||

| Body temperature (°F) | 97.6 (0.7) | 830 | 0.09 | .01 | 837 | −0.02 | .52 | ||

| Week of menstrual cyclec | 2.64 (1.08) | 352 | 0.10 | .05 | 352 | 0.04 | .43 | ||

| Anti-inflammatory medication | 254 (30.4%) | 829 | 0.10 | .006 | 836 | 0.002 | .94 | ||

| Inflammatory biomarkers | |||||||||

| hsCRPa (mg/L) | 2.39 (3.83) | 830 | 0.15 | <.001 | |||||

| suPAR (ng/mL) | 2.40 (0.91) | 830 | 0.15 | <.001 | |||||

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.72 (0.57) | 819 | 0.61 | <.001 | 819 | 0.19 | <.001 | ||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 1.55 (1.61) | 790 | 0.44 | <.001 | 790 | 0.08 | .02 | ||

| White blood cell count | |||||||||

| White blood cells (x109/L) | 7.90 (1.80) | 827 | 0.22 | <.001 | 827 | 0.22 | <.001 | ||

| Neutrophils (x109/L) | 4.52 (1.39) | 827 | 0.22 | <.001 | 827 | 0.16 | <.001 | ||

| Lymphocytes (x109/L) | 2.47 (0.66) | 827 | 0.09 | .01 | 827 | 0.18 | <.001 | ||

| Monocytes (x109/L) | 0.66 (0.19) | 827 | 0.18 | <.001 | 827 | 0.18 | <.001 | ||

| Eosinophils (x109/L) | 0.22 (0.15) | 827 | 0.01 | .76 | 827 | 0.05 | .17 | ||

| Basophils (x109/L) | 0.02 (0.04) | 827 | −0.10 | .006 | 827 | 0.04 | .29 | ||

Log-transformed hsCRP (natural logarithm);

Pearson’s and Spearmans’s correlation coefficients for continuous and categorical variables, respectively;

Days since last menstrual period began; BMI, body mass index; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; SD, standard deviation; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor.

High hsCRP and high suPAR were significantly but weakly correlated with each other (r=0.15) and both were correlated with elevated fibrinogen, IL-6, and WBC counts (Table 2).

Associations of hsCRP and suPAR with health outcomes at age 38 years

At age-38, high hsCRP and high suPAR were both associated with poor self-reported health and older Biological Age (Table 3). High suPAR was also significantly associated with older facial age. After controlling for sex and risk factors for poor adult health (i.e., BMI and smoking), high hsCRP remained significantly associated with older Biological Age, while high suPAR remained significantly associated with older Biological Age and older facial age (Table 3). When further controlling for hsCRP, suPAR still remained significantly associated with older Biological Age (b 0.09; SE 0.04; p=.009) and older facial age (b 0.16; SE 0.04; p<.001). Neither hsCRP nor suPAR were significantly associated with telomere length.

Table 3.

Associations of hsCRP and suPAR with health outcomes at age 38 years in the Dunedin study

| hsCRPa | suPAR | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedb | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |||||||||

| Health outcomes | N | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | |||

| Self-reported health | 827 | −0.16 (0.03) | <.001 | −0.04 (0.04) | .28 | −0.16 (0.03) | <.001 | −0.07 (0.04) | .06 | |||

| Biological Agec | 827 | 0.33 (0.03) | <.001 | 0.19 (0.04) | <.001 | 0.18 (0.03) | <.001 | 0.11 (0.04) | .004 | |||

| Facial aging | 827 | 0.05 (0.03) | .13 | 0.01 (0.04) | .88 | 0.23 (0.03) | <.001 | 0.16 (0.04) | <.001 | |||

| Telomere length | 811 | −0.02 (0.03) | .66 | −0.01 (0.04) | .73 | −0.04 (0.04) | .24 | −0.04 (0.04) | .29 | |||

Log-transformed hsCRP (natural logarithm);

Adjusted for sex, body mass index, and smoking;

The cross-sectional index of Biological Age at age-38 was calculated using the Klemera-Doubal equation for the following ten biomarkers (see Table 1): albumin, alkaline phosphatase, blood pressure (systolic), CRP, creatinine, cytomegalovirus IgG, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol, and urea nitrogen. Thus, hsCRP is part of this measure; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; SE, standard error; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor

Childhood risk factors predict hsCRP and suPAR levels in adulthood

Children in poorer health, from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, or with lower IQ had elevated hsCRP levels later in life, at age-38 (Table 4). Similarly, children in poorer health, from disadvantaged backgrounds, with more Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), lower IQ, or poorer self-control had elevated age-38 suPAR levels (Table 4). (Details about the correlations between the components of ACEs and hsCRP or suPAR are presented in Table S1). After controlling for sex, BMI, and smoking, children who experienced more ACEs, had lower IQ, or poorer self-control still showed evidence of elevated age-38 suPAR, while none of the associations between childhood risk factors and age-38 hsCRP survived adjustment for the covariates sex, BMI, and smoking (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations of childhood risk factors with hsCRP and suPAR at age 38 years in the Dunedin study

| hsCRPa | suPARb | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedc | Unadjusted | Adjustedc | |||||||||

| Childhood risk factors | N | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | |||

| Poor health | 786 | 0.11 (0.04) | .002 | −0.03 (0.03) | .44 | 0.08 (0.03) | .03 | 0.05 (0.03) | .16 | |||

| Socio-economic status | 823 | −0.11 (0.03) | .002 | −0.02 (0.03) | .57 | −0.12 (0.03) | <.001 | −0.04 (0.03) | .23 | |||

| ACEs | 827 | 0.04 (0.03) | .25 | −0.03 (0.03) | .42 | 0.20 (0.03) | <.001 | 0.10 (0.03) | .003 | |||

| IQ | 807 | −0.11 (0.03) | .002 | −0.01 (0.03) | .71 | −0.18 (0.03) | <.001 | −0.08 (0.03) | .01 | |||

| Poor self-control | 827 | 0.06 (0.03) | .08 | 0.03 (0.03) | .37 | 0.12 (0.03) | <.001 | 0.07 (0.03) | .05 | |||

| Cumulative Childhood Riskd,e | 826 | 0.09 (0.03) | .007 | −0.01 (0.03) | .67 | 0.20 (0.03) | <.001 | 0.10 (0.03) | .002 | |||

Log-transformed hsCRP (natural logarithm);

Results for untransformed and log-transformed suPAR are shown in Table S2;

Adjusted for sex, body mass index, and smoking;

Cumulative Childhood Risk represents a count of the 5 risk factors, where 1 point was given for being in the quartile associated with highest risk for each of the five childhood risk factors investigated: poor childhood health, low childhood socioeconomic status, more adverse childhood experiences, low IQ, and low self-control;

Historically, the epidemiological literature has also focused on measures associated with blood thickness and clotting, most often using the biomarker fibrinogen. We therefore repeated analyses reported here for Cumulative Childhood Risk, but also using fibrinogen in Table S3; ACE, adverse childhood experiences (prospective); hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IQ, intelligence quotient; SE, standard error; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor.

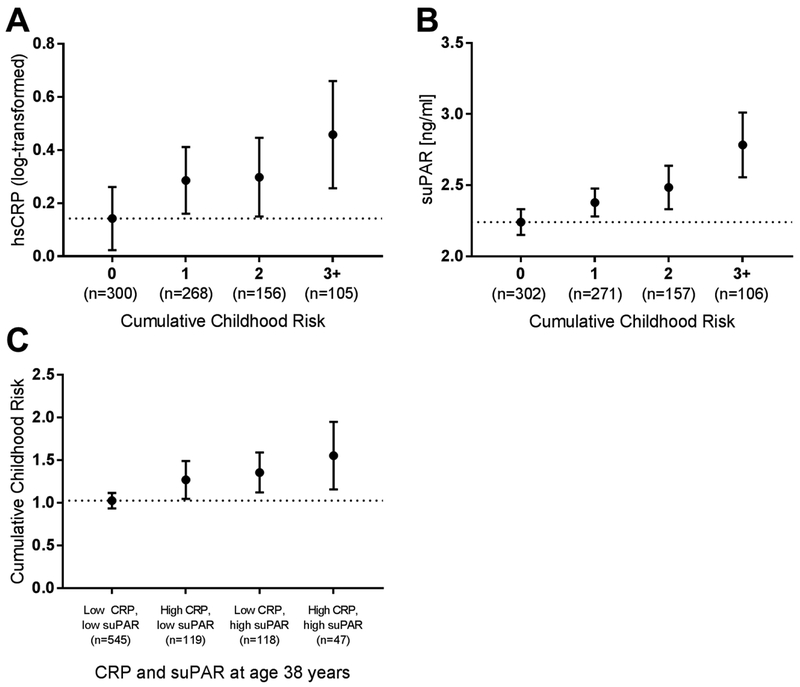

We aggregated the five childhood risk factors into a single Cumulative Childhood Risk index. Mean hsCRP and suPAR levels were plotted against the Cumulative Childhood Risk index (Figure 1A and 1B, respectively). Cumulative Childhood Risk was significantly related to both inflammatory biomarkers, although only the association with suPAR survived controls for sex, BMI, and smoking (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Relationship between hsCRP, suPAR, and Cumulative Childhood Risk in the Dunedin study. Mean (95%CI) age-38 (A) log-transformed hsCRP and (B) suPAR plotted against Cumulative Childhood Risk Index. (C) Mean (95%CI) Cumulative Childhood Risk Index scores of individuals stratified by high CRP (hsCRP>3 mg/L) and high suPAR (>2.89 ng/mL) levels. Dotted line: mean of reference group.

We further investigated whether the associations between childhood risk factors and elevated suPAR levels were independent of elevated hsCRP. After controlling for hsCRP, children who grew up in socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds (b −0.09; SE 0.03; p=.006), who experienced more ACEs (b 0.20; SE 0.03; p<.001), had lower IQs (b −0.17; SE 0.03; p<.001), or poorer self-control (b 0.11; SE 0.03; p=.002) had elevated age-38 suPAR levels. Poor childhood health was not associated with elevated suPAR when controlling for hsCRP (b 0.05; SE 0.03; p=.18). Finally, Cumulative Childhood Risk was a significant, independent predictor of elevated suPAR, even when controlling for hsCRP (b 0.18; SE 0.03; p<.001).

Predicting combined hsCRP and suPAR in adulthood

Using information about both hsCRP and suPAR to characterize inflammation in adulthood, we studied four groups of individuals: those with low levels of hsCRP and suPAR, elevated hsCRP only, elevated suPAR only, and elevated levels of both inflammatory biomarkers (Figure 1C). Children with high Cumulative Childhood Risk indices were significantly more likely to have elevated levels of both hsCRP and suPAR in adulthood (OR,1.38; 95% CI, 1.10–1.73). In addition, Cumulative Childhood Risk predicted elevated suPAR even in the absence of elevated hsCRP (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.02–1.41); in contrast, Cumulative Childhood Risk was less strongly linked to elevated hsCRP in the absence of elevated suPAR (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.97–1.35). (Table S4 presents the results for the Cumulative Childhood Risk index as well as for each of its 5 constituent risk factors; see also Figure S2.)

DISCUSSION

In this four-decade longitudinal study of a birth cohort, we tested the potential utility of using a new biomarker, suPAR, to understand the role of inflammation in the context of the developmental origins of health and disease. Three findings stand out about the measurement, prediction, and potential uses of this inflammatory biomarker.

First, consistent with prior reports that suPAR predicts disease and mortality (Eugen-Olsen et al., 2010), we observed that elevated suPAR, like hsCRP, is associated with poor health at midlife, as reflected in cohort members’ self-awareness of their own physical well-being, accelerated biological aging, and even their facial appearance. This suggests that suPAR captures health-relevant information about the burden of systemic inflammation in the body, even in early midlife and in a relatively healthy birth cohort.

Second, children exposed to known risk factors for disease and early mortality, including poor health, socioeconomic disadvantage, more ACEs, low IQ, or poor self-control, had elevated suPAR levels as adults. The association between childhood risk factors and suPAR remained after controlling for key risk factors for poor adult health, including BMI and smoking. Prospective assessment of childhood risk factors ensured that there was no ascertainment bias or recall bias. Our finding that these childhood risk factors contribute to elevated adulthood inflammation is consistent with previous findings (Baumeister, Akhtar, Ciufolini, Pariante, & Mondelli, 2015; Slopen et al., 2015), including in this cohort (Danese, Pariante, Caspi, Taylor, & Poulton, 2007), using other inflammatory biomarkers, most notably hsCRP but also IL-6, fibrinogen, and tumor necrosis factor-α. Of interest, the associations between childhood risks and adult suPAR levels were less affected by adjustments for covariates than were associations between childhood risks and hsCRP, possibly because suPAR is less sensitive to acute circumstances and may better reflect chronic inflammation.

Third, suPAR levels appear to add information about health implications of childhood risks above and beyond hsCRP, as childhood risk factors, excepting childhood health, remained significantly associated with adult suPAR when controlling for hsCRP levels. In addition, we observed the strongest associations between childhood risk and adulthood inflammation when combining information about both high hsCRP and high suPAR, suggesting that hsCRP and suPAR, and maybe other inflammatory biomarkers, should be used together when estimating inflammatory burden that may be linked to childhood risks.

These findings suggest that suPAR may be a useful tool in conceptualizing and measuring the early-life origins of inflammatory processes in disease and aging (Danese & Baldwin, 2017). As a biochemical analyte, suPAR is a very stable protein that can be easily measured in fresh or frozen plasma or serum samples and does not vary greatly in terms of pre- and post-sampling procedures (food intake, time of day, etc.) (Andersen, Eugen-Olsen, Kofoed, Iversen, & Haugaard, 2008). Clinical studies have found suPAR to be associated with incidence and prevalence of disease and with disease severity and prognosis. This applies to acute as well as chronic diseases and infectious as well as non-communicable diseases, including clinical conditions investigated in children (Schaefer et al., 2017; Şirinoğlu et al., 2017; Wittenhagen et al., 2011; Wrotek, Jackowska, & Pawlik, 2015). suPAR appears to reflect the health status or inflammatory burden of an individual, and chronic multimorbid patients have higher suPAR levels than patients with fewer chronic diseases (Rasmussen et al., 2016), while healthy people have low suPAR levels (Haupt et al., 2014). In the general population, suPAR has been found to increase with age and unhealthy lifestyle, with smoking and morbid obesity being major drivers of increased suPAR levels (Haupt et al., 2014). Of note, one study showed favorable lifestyle changes are reflected in reduced suPAR levels (Eugen-Olsen, Ladelund, & Sørensen, 2016), suggesting that suPAR may provide an outcome measure for studies of potential “reversibility” of chronic inflammation resulting from early-life risk exposures.

Previous research has suggested that hsCRP and suPAR reflect different aspects of inflammation (Lyngbæk et al., 2013); while hsCRP is an acute-phase reactant associated with acute and metabolic inflammation, suPAR seems to be a marker of chronic rather than acute inflammation. In line with this, we found that hsCRP and suPAR were only weakly positively correlated with each other, and although both were correlated with other measures of inflammation, including WBCs, fibrinogen, and IL-6, suPAR showed a weaker correlation with fibrinogen and IL-6. In addition, hsCRP was positively correlated with clinical factors that could influence acute inflammation, such as body temperature, menstruation, and use of anti-inflammatory medication, while suPAR was not associated with these.

The present study has limitations. First, we studied a single New Zealand birth cohort that lacked ethnic minority representation. Replications are needed in diverse populations. Second, suPAR was only measured once, at age-38. Since blood for the assay was not biobanked during childhood, we were unable to investigate changes in suPAR levels from childhood to midlife. Longitudinal studies of suPAR are needed. Third, although the distributional properties of suPAR are appealing for research purposes, the optimal threshold for its use as diagnostic biomarker has not yet been estimated. Fourth, the detected effect sizes were modest for both suPAR and hsCRP, although this is to be expected in a general population of generally healthy persons at midlife. Moreover, once we turned to examine cumulative risk, the effect sizes increased considerably, underscoring the conceptual and practical importance of evaluating multiple risk factor exposures rather than any single exposure (Evans, Li, & Whipple, 2013). Fifth, we were able to identify risk factors associated with elevated suPAR levels, but due to the observational study design, we cannot rule out non-causal alternative explanations of these associations. It would be informative to incorporate suPAR into randomized clinical trials of interventions intended to reduce effects of childhood risk factors (Moffitt, 2013). Finally, it should be noted that the relation between suPAR and hsCRP may be different in clinical populations with specific diseases than in a relatively healthy population like the present.

CONCLUSION

The findings suggest several implications. First, the results strengthen the theory that adult inflammation has origins in childhood (Danese & Baldwin, 2017). Second, future life-course research about inflammation could add suPAR as an adjunct to hsCRP, as a new measure that may reflect additional long-term inflammatory processes. It is noteworthy that childhood risk factors were prominent in the group of participants with low hsCRP and high suPAR—a group that would inadvertently have been assigned to the low inflammation group if suPAR had not been measured. Moreover, the combination of hsCRP and suPAR may strengthen etiological research about the origins of adult inflammation. Third, the results provide further impetus to add measurements of inflammatory phenotypes into research programs aimed at understanding the origins of adult disease and improving lifelong health.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Dunedin Study members, unit research staff, and study founder Phil Silva, PhD, University of Otago. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is supported by the New Zealand Health Research Council and New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE). This research received support from US National Institute of Aging grant R01AG032282, UK Medical Research Council grant MR/P005918/1, and the Jacobs Foundation. L.J.H.R. is supported by a PhD scholarship from the Lundbeck Foundation (grant no. R180–2014-3360).

Abbreviations:

- ACE

adverse childhood experience

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- hsCRP

high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- IQ

intelligence quotient

- NZ

New Zealand

- OR

odds ratio

- SD

standard deviation

- SE

standard error

- SES

socioeconomic status

- suPAR

soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor

- WBC

white blood cell

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: L.J.H.R. has received funding for travel from ViroGates A/S, Denmark, the company that produces the suPARnostic assays. J.E-O. is a named inventor on patents on suPAR as a prognostic biomarker. The patents are owned by Copenhagen University Hospital Amager and Hvidovre, Denmark, and licensed to ViroGates A/S. J.E-O. is a co-founder, shareholder, and CSO of ViroGates A/S. All other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest relating to this research.

REFERENCES

- Andersen O, Eugen-Olsen J, Kofoed K, Iversen J, & Haugaard SB (2008). Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor is a Marker of Dysmetabolism in HIV-Infected Patients Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Journal of Medical Virology, 80, 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister D, Akhtar R, Ciufolini S, Pariante C, & Mondelli V (2015). Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Molecular Psychiatry, 21, 642–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky DW, Caspi A, Houts R, Cohen HJ, Corcoran DL, Danese A, … Moffitt TE (2015). Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A, 112, E4104–E4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky DW, Caspi A, Israel S, Blumenthal JA, Poulton R, & Moffitt TE (2015). Cardiorespiratory fitness and cognitive function in midlife: Neuroprotection or neuroselection? Annals of Neurology, 77, 607–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi F, & Carmeliet P (2002). uPAR: a versatile signalling orchestrator. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 3, 932–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowtell DDL (1987). Rapid isolation of eukaryotic DNA. Analytical Biochemistry, 162, 463–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch JB, Augustine AD, Frieden LA, Hadley E, Howcroft TK, Johnson R, … Wise BC (2014). Advances in geroscience: Impact on healthspan and chronic disease. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 69, 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin CM, Batty GD, Der G, Brett CE, Taylor A, Pattie A, … Deary IJ (2017). Childhood intelligence in relation to major causes of death in 68 year follow-up: prospective population study. Bmj, 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin CM, Deary IJ, Fenton C, Roberts BA, Der G, Leckenby N, & Batty GD (2011). Intelligence in youth and all-cause-mortality: Systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40, 626–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon RM (2002). Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Research, 30, e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/about.html

- Danese A, & Baldwin J (2017). Hidden Wounds? Inflammatory Links Between Childhood Trauma and Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Psychol, (68), 517–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, & McEwen BS (2012). Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiology and Behavior, 106, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, & Poulton R (2007). Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 1319–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers PE, ten Hove T, te Velde a a, van Deventer SJ., & van Der Poll T (2000). Upregulation of monocyte urokinase plasminogen activator receptor during human endotoxemia. Infection and Immunity, 68, 2156–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmedt S, Desmedt V, Delanghe JR, Speeckaert R, & Speeckaert MM (2017). The intriguing role of soluble urokinase receptor in inflammatory diseases. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 54, 117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadello K, Scolletta S, Taccone FS, Covajes C, Santonocito C, Cortes DO, … Vincent J-L (2014). Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor as a prognostic biomarker in critically ill patients. Journal of Critical Care, 29, 144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugen-Olsen J, Ladelund S, & Sørensen LT (2016). Plasma suPAR is lowered by smoking cessation: A randomized controlled study. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 46, 305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugen-Olsen J, Andersen O, Linneberg A, Ladelund S, Hansen TW, Langkilde A, … Haugaard SB (2010). Circulating soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor predicts cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and mortality in the general population. Journal of Internal Medicine, 268, 296–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Li D, & Whipple SS (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139, 1342–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz a M., Edwards V, … Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich MJ (2014). Research on psychiatric disorders targets inflammation. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 312, 474–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthoff M, Wagner R, Randrianarisoa E, Hatziagelaki E, Peter A, Häring H-U, … Heyne N (2017). Soluble urokinase receptor (suPAR) predicts microalbuminuria in patients at risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Scientific Reports, 7, 40627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper S (2014). Economic and social implications of aging societies. Science, 346, 587–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt TH, Kallemose T, Ladelund S, Rasmussen LJH, Thorball CW, Andersen O, … Eugen-Olsen J (2014). Risk Factors Associated with Serum Levels of the Inflammatory Biomarker Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor in a General Population. Biomarker Insights, 9, 91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayek SS, Sever S, Ko Y-A, Trachtman H, Awad M, Wadhwani S, … Reiser J (2015). Soluble Urokinase Receptor and Chronic Kidney Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 373, 1916–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanpierre M (1987). A rapid method for the purification of DNA from blood. Nucleic Acids Research, 15, 9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemera P, & Doubal S (2006). A new approach to the concept and computation of biological age. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 127, 240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine ME (2013). Modeling the rate of senescence: Can estimated biological age predict mortality more accurately than chronological age? Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68, 667–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyngbæk S, Sehestedt T, Marott JL, Hansen TW, Olsen MH, Andersen O, … Jeppesen J (2013). CRP and suPAR are differently related to anthropometry and subclinical organ damage. International Journal of Cardiology, 167, 781–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, & Parker KJ (2011). Psychological Stress in Childhood and Susceptibility to the Chronic Diseases of Aging: Moving Towards a Model of Behavioral and Biological Mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 959–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (2013). Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: Clinical intervention science and stress-biology research join forces. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 1619–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Belsky DW, Danese A, Poulton R, & Caspi A (2017). The Longitudinal Study of Aging in Human Young Adults: Knowledge Gaps and Research Agenda. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 72, 210–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, … Caspi A (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108, 2693–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski SR, Piironen T, Høyer-Hansen G, Gerstoft J, Pedersen BK, & Ullum H (2005). Reduced release of intact and cleaved urokinase receptor in stimulated whole-blood cultures from human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected patients. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology, 61, 347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson M, Ostling G, Smith G, Hamrefors V, Melander O, Hedblad B, & Engström G (2014). Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor: A Risk Factor for Carotid Plaque, Stroke, and Coronary Artery Disease. Stroke, 45, 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne BJ, Thomson WM, Taylor A, Sears MR, & Moffitt TE (2002). Association between children’s experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health, 360, 1640–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulton R, Moffitt TE, & Silva PA (2015). The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study: overview of the first 40 years, with an eye to the future. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50, 679–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Kuh D, & Morton S (2013). From developmental origins of adult disease to life course research on adult disease and aging: insights from birth cohort studies. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 7–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen LJH, Ladelund S, Haupt TH, Ellekilde G, Poulsen JH, Iversen K, … Andersen O (2016). Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) in acute care: a strong marker of disease presence and severity, readmission and mortality. A retrospective cohort study. Emergency Medicine Journal, 33, 769–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnati M, Pallavicini I, Wang JM, Oppenheim J, Serhan CN, Romano M, & Blasi F (2002). The fibrinolytic receptor for urokinase activates the G protein-coupled chemotactic receptor FPRL1/LXA4R, 99, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Belsky DW, Harrington H, Schroeder F, … Danese A (2016). Lest we forget: comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 57, 1103–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM (2003). Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation, 107, 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer F, Trachtman H, Wühl E, Kirchner M, Hayek SS, Anarat A, … Reiser J (2017). Association of Serum Soluble Urokinase Receptor Levels With Progression of Kidney Disease in Children. JAMA Pediatrics, e172914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev I, Moffitt TE, Braithwaite AW, Danese A, Fleming NI, Goldman-Mellor S, … Caspi A (2014). Internalizing disorders and leukocyte telomere erosion: a prospective study of depression, generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 19, 1163–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şirinoğlu M, Soysal A, Karaaslan A, Kepenekli Kadayifci E, Yalındağ-Öztürk N, Cinel İ, …Bakır M (2017). The diagnostic value of soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) compared to C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) in children with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy, 23, 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Loucks EB, Appleton AA, Kawachi I, Kubzansky LD, Non AL, … Gilman SE (2015). Early origins of inflammation: An examination of prenatal and childhood social adversity in a prospective cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 51, 403–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorio C, Mafficini A, Furlan F, Barbi S, Bonora A, Brocco G, … Scarpa A (2011). Elevated urinary levels of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma identify a clinically high-risk group. BMC Cancer, 11, 448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpgaard LS, Christensen IJ, Høyer-Hansen G, Lund IK, Guren TK, Glimelius B, … Brünner N (2015). Intact and cleaved plasma soluble urokinase receptor in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with oxaliplatin with or without cetuximab. International Journal of Cancer 137, 2470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. (2012). C-Reactive Protein, Fibrinogen, and Cardiovascular Disease Prediction. New England Journal of Medicine , 367, 1310–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1974). Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Revised. Psychological Corporation, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- Wittenhagen P, Andersen JB, Hansen A, Lindholm L, Rønne F, Theil J, … Eugen-Olsen J. (2011). Plasma soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor in children with urinary tract infection. Biomarker Insights, 6, 79–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrotek A, Jackowska T, & Pawlik K (2015). Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor: an indicator of pneumonia severity in children. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 835, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.