Abstract

Background:

Employer-sponsored health insurance, particularly for retirees with limited incomes, plays a major funding role in Canadian health care, including prescription drugs and dental services. We aimed to investigate the changes in retiree health insurance availability over time.

Methods:

We performed a secondary analysis of data from the 2005 and 2013–2014 cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey using multivariate logistic regression to study changes in retiree coverage availability over time in Ontario. We estimated the adjusted odds ratios of having employer coverage for likely retirees (people over age 65 yr who reported not working and those over age 75 yr), adjusting for a number of potential confounders. Sensitivity analysis was also performed for coverage of different treatments separately.

Results:

The response rate was 76% for the 2005 cycle and 66% for 2013–2014 for the entire survey. The characteristics of respondents in the 2 survey cycles were similar, except respondents in 2013–2014 were wealthier. In our adjusted model, respondents in 2013–2014 had lower odds of reporting retiree coverage than respondents in 2005 (adjusted odds ratio 0.87; 95% confidence interval 0.77–0.99). This represents an absolute reduction in the probability of receiving retiree coverage of up to 3.4%.

Interpretation:

Our analysis suggests that the rate of retiree health insurance has declined for Canadians with similar characteristics over the past decade. As we know insurance coverage has a strong association with use of treatments such as prescription drugs and dental care, this decline may result in decreased access to treatment and is an issue that warrants further investigation.

In contrast to the coverage offered in other countries with universal health care systems, universal coverage is provided only for physician and hospital services in Canada.1 Pharmaceuticals and services such as dental care and vision care are paid through a mix of public and private insurance and out-of-pocket payments.1 Approximately 60% of Canadians hold private insurance for prescription drugs, which is mostly provided by employers to their employees and, in some cases, their retirees.2 Other health services are not insured publicly except for certain populations, and the availability of private insurance for these services is unclear.3,4

The availability of employer-sponsored private health insurance is an important determinant of access to these other types of health care. Older people in particular have been found in various studies to be sensitive to reductions in costs offered through private health insurance.5–7 For example, Allin and colleagues found a further reduction of a few dollars through private insurance on copayments of up to $6.11 under Ontario’s public drug program appeared to incentivize seniors to use certain types of medications.5 The higher out-of-pocket costs faced by those without such insurance can present a significant barrier to accessing treatment, potentially resulting in poorer health outcomes.3,6,8–12 Retirees, who may receive employer coverage as part of a retirement package, may be particularly vulnerable to loss of coverage and increased out-of-pocket costs as they may have limited income flexibility.5,13 Thus, it is important to observe any prevailing trends in the coverage of Canadian retirees.

From 1988 to 2015, private health insurance expenditures increased from $193 to $1059 per capita in Canada.14 This increase in costs is being passed onto employers who provide coverage. What remains unclear is how Canadian employers are responding to these changes. Analyses from the United States have found that in response to increasing premiums, steps were taken to limit both the availability and scope of employer coverage.14,15 For example, between 1996 and 2000, the proportion of retirees aged 65 to 69 years who had retiree coverage decreased from 46% to 39%.15 Surveys of employers in Ontario assessing coverage for current and retired employees confirm that employers are becoming less generous.16 Although other data also suggest that Canadian employer coverage is becoming less generous,17 we have limited information on the changes in coverage and the number of people affected, if any. Therefore, we used data from 2 large surveys to investigate the change between 2005 and 2014 in the availability of employer coverage for retirees.

Methods

Study context

Public drug coverage schemes for seniors vary widely across provinces. Some provinces (e.g., Ontario, Alberta and the Maritime provinces) have adopted an age-based approach where individuals over the age of 65 years are automatically offered special coverage; other provinces (e.g., British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Manitoba) have adopted an income-based approach.18,19 All of these coverage schemes have annual deductibles — that is, out-of-pocket payments for prescription costs before the start of coverage — and copayments/coinsurance after coverage starts.18,19 Any of these out-of-pocket costs may be reduced by the availability of private insurance, which is most commonly obtained through employers and may include family members as beneficiaries.18 Only about 10% of all private insurance policies are taken out independently.20 Allin and colleagues estimated that among Ontario residents over the age of 65 years without an independent private insurance policy, 27% received private insurance for prescriptions from their current or previous employer in 2005.5 Other treatments, such as dental care and vision care, are not covered for seniors in any province except for people with very low incomes.3,4 These are funded almost exclusively through private insurance and out-of-pocket payments.3,4

Survey data and study design

This study used data from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), an ongoing cross-sectional survey conducted by Statistics Canada. The survey sample is derived from a multistage stratified cluster sampling design and is intended to be representative of approximately 97% of the population aged 12 years and older, with steps taken to account for non-response to produce accurate national and regional estimates. Additional information on the sampling and interviewing methods is published elsewhere.21–23 Validation steps include comparison of data year to year and by geographical region, as well as external validation by provincial and federal partners to ensure data accuracy.21 Before 2005, the survey was conducted every 2 years over a 1-year period. Since then, the survey has been conducted annually and the results have been released as 2-year cycles to cover the same number of respondents as cycles released before this change.

Study samples

We used data from the 2005 and 2013–2014 survey cycles. Our study sample was restricted to respondents who resided in Ontario at the time of interview, as it was the only province in which the optional module on health insurance was asked in more than 1 cycle. To capture retirees, we included respondents if they were 75 years of age or older, or if they were aged 65 to 75 years and responded that they had not worked at a job or business at any time in the past 12 months. We excluded people who had immigrated to Canada fewer than 10 years ago to limit the number of people who arrived in Canada after retirement as their inclusion would have inflated the number of people who may potentially have retiree coverage from a Canadian employer. We also excluded those who did not provide valid responses to the questions on employer coverage, job status or immigration status.

Variables for analysis

Our key variable of interest was whether the person reported having retiree health insurance. This was constructed from self-reported coverage in 4 areas: prescription medications, dental care, eyeglasses and private/semiprivate hospital rooms. We flagged people as having retiree coverage if they reported employer-sponsored insurance for any of these areas. Our explanatory variable was a binary variable denoting survey cycle (2005 or 2013–2014). Our analysis included a range of potential confounders for the relationship between year and employer coverage among retirees, including age, sex, marital status, urban/rural residence, household income, highest education level within the household, self-reported health status and number of reported chronic illnesses (including self-reported asthma, arthritis, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, heart disease, previous stroke, bowel disease and mood disorder). The sociodemographic factors were chosen as they are known to influence the likelihood of having employer-sponsored coverage. We chose to control for household income and education within the household as coverage may be available through a spouse. We chose to control for marital status for the same reason. Please refer to Appendix 1 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/1/E15/suppl/DC1) for the survey questions.

Statistical analysis

We modelled the association between survey cycle and reporting having retiree health insurance using a logistic regression model.24 On the basis of the results, we also calculated predicted probabilities given individual characteristics and population estimates from 2014.25 Population estimates and their variances for all statistical analyses were calculated by applying probability and bootstrap weights provided by Statistics Canada.21 The probability weights from the individual survey cycles were adjusted using the pooled approach to produce a single data set to be analyzed.26 It was feasible to combine survey cycles using this approach because the questions from which the variables for analysis were derived, survey coverage, and mode of collection had not changed.26

Sensitivity analysis

We also performed 2 sensitivity analyses on our logistic regression model. First, we analyzed using reported household incomes instead of income quintiles. We also analyzed the association between survey cycle and each insurance type individually (i.e., insurance for prescription medications, eyeglasses, private/semiprivate hospital rooms and dental care).

Ethics approval

This study is covered under the publicly available data clause (item 7.10.3) of the University of British Columbia’s Policy no. 89: Research Involving Human Participants, which exempts research involving the use of publicly available data protected by law from requiring study-specific ethics approval.27

Results

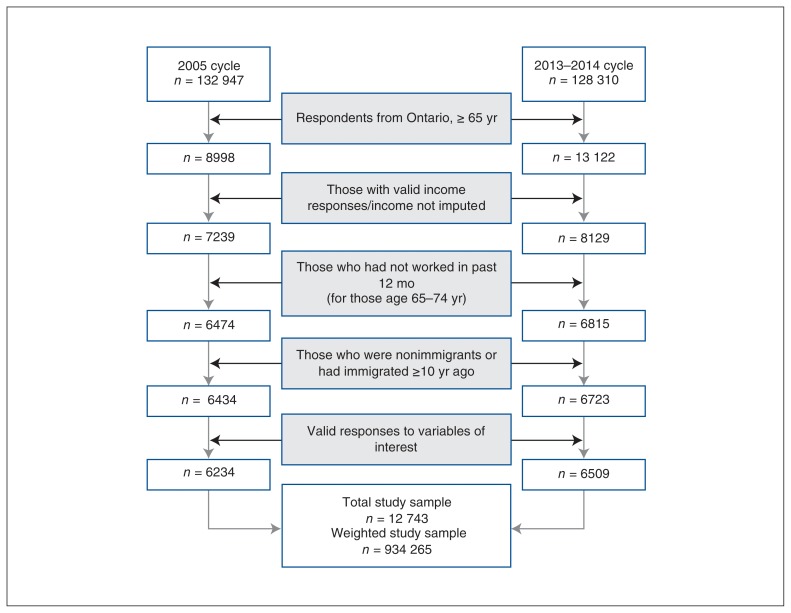

The response rates were 76% for the 2005 cycle and 66% for 2013–2014 for the entire survey.22,23 Our final cohort included 6234 respondents from 2005 and 6509 from 2013–2014, with 51.3% of the final weighted sample in 2005 and 48.7% in 2013–2014 (see Figure 1 for derivation). As shown in Table 1, respondents in 2013–2014 had slightly higher education levels and better self-reported health status. However, the number of reported chronic diseases was similar in the 2 cohorts. Notably, respondents in 2013–2014 were comparatively wealthier than the earlier cohort: the percentage of respondents in the lowest quintile of household incomes dropped from 35.2% in 2005 to 25.2% in 2013–2014. The cohorts from the 2 survey cycles were similar in other respects (Table 1). About one-third of respondents reported having retiree health insurance in both cycles: 32.6% and 33.1% in the 2005 cycle and 2013–2014 cycles, respectively.

Figure 1:

Derivation of study sample from cycle 3.1 (2005 cycle) and the 2013–2014 cycle of the Canadian Community Health Survey, including exclusions because of missing/invalid responses.

Table 1:

Characteristics of study sample, investigating the relationship between availability of retiree health insurance and survey year using data from the combined cycle 3.1 (2005) and the 2013–2014 cycle of the Canadian Community Health Survey

| Characteristic | Total study sample | Study sample by survey year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 2005 (cycle 3.1) | 2013–2014 cycle | |||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Weighted frequency | Percentage ± SE | Weighted frequency | Percentage ± SE | Weighted frequency | Percentage ± SE | |

| Total study sample | 934 265 | 100 | 479 192 | 51.3 ± 0.7 | 455 072 | 48.7 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Insurance availability | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| No employer health insurance | 627 455 | 67.2 ± 0.7 | 323 043 | 67.9 ± 0.6 | 304 412 | 66.9 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Has employer health insurance | 306 810 | 32.8 ± 0.7 | 156 150 | 32.6 ± 0.5 | 150 660 | 33.1 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Has prescription coverage | 257 584 | 27.6 ± 0.6 | 129 195 | 27.0 ± 0.4 | 128 388 | 28.2 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Has dental coverage | 236 215 | 25.3 ± 0.6 | 119 371 | 24.9 ± 0.4 | 116 844 | 25.7 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Has eyeglasses coverage | 233 992 | 23.0 ± 0.6 | 117 961 | 24.6 ± 0.4 | 116 031 | 25.5 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Has hospital room coverage | 247 031 | 26.4 ± 0.6 | 133 887 | 27.9 ± 0.5 | 113 143 | 24.9 ± 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Age, yr | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 65–69 | 258 626 | 27.7 ± 0.7 | 128 429 | 26.8 ± 0.5 | 130 187 | 28.6 ± 0.6 |

|

| ||||||

| 70–74 | 231 253 | 24.8 ± 0.6 | 122 302 | 25.5 ± 0.4 | 108 951 | 23.9 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| 75–79 | 218 646 | 23.4 ± 0.6 | 114 066 | 23.8 ± 0.4 | 104 579 | 23.0 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 80 | 225 740 | 24.2 ± 0.6 | 114 386 | 23.9 ± 0.5 | 111 354 | 24.5 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Male | 420 238 | 45.0 ± 0.7 | 207 369 | 43.3 ± 0.6 | 212 869 | 46.8 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Female | 514 026 | 55.0 ± 0.7 | 271 823 | 56.7 ± 0.6 | 242 203 | 53.2 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Urban/rural dwelling | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Rural | 153 579 | 16.4 ± 0.4 | 68 660 | 14.3 ± 0.3 | 84 919 | 18.7 ± 0.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Urban | 780 686 | 83.6 ± 0.4 | 410 533 | 85.7 ± 0.7 | 370 153 | 81.3 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Total household income — provincial quintile | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Quintile 1 | 283 233 | 30.3 ± 0.7 | 168 447 | 35.2 ± 0.5 | 114 786 | 25.2 ± 0.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Quintile 2 | 250 340 | 26.8 ± 0.6 | 131 512 | 27.4 ± 0.5 | 118 828 | 26.1 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Quintile 3 | 186 714 | 20.0 ± 0.6 | 86 534 | 18.1 ± 0.4 | 100 180 | 22.0 ± 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Quintile 4 | 138 111 | 14.8 ± 0.5 | 60 824 | 12.7 ± 0.4 | 77 287 | 17.0 ± 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Quintile 5 | 75 866 | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 31 875 | 6.7 ± 0.3 | 43 991 | 9.7 ± 0.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Highest level of education within household | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Did not complete secondary | 204 336 | 21.9 ± 0.5 | 118 025 | 24.6 ± 0.4 | 86 312 | 19.0 ± 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Secondary graduate | 160 176 | 17.1 ± 0.6 | 74 614 | 15.6 ± 0.3 | 85 562 | 18.8 ± 0.6 |

|

| ||||||

| At least some postsecondary | 569 752 | 61.0 ± 0.7 | 286 553 | 59.8 ± 0.7 | 283 199 | 62.2 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| No. of chronic illnesses | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| None | 169 573 | 18.2 ± 0.6 | 88 705 | 18.5 ± 0.4 | 80 868 | 17.8 ± 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| 1 or 2 | 547 896 | 58.6 ± 0.7 | 285 002 | 59.5 ± 0.6 | 262 895 | 57.8 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| 3 or 4 | 192 687 | 20.6 ± 0.6 | 94 151 | 19.6 ± 0.4 | 98 536 | 21.7 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 5 | 24 108 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 11 335 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 12 774 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Single/never married | 41 097 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 20 871 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 20 226 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Common-law | 21 913 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 6364 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 15 550 | 3.4 ± 0.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Married | 558 578 | 59.8 ± 0.7 | 290 260 | 60.6 ± 0.7 | 268 317 | 59.0 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 312 677 | 33.5 ± 0.7 | 161 697 | 33.7 ± 0.5 | 150 980 | 33.2 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Self-reported health status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Excellent | 120 993 | 13.0 ± 0.5 | 55 032 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 65 961 | 14.5 ± 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Very good | 278 512 | 29.8 ± 0.6 | 139 569 | 29.1 ± 0.5 | 139 942 | 30.5 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Good | 305 299 | 32.7 ± 0.7 | 158 345 | 33.0 ± 0.5 | 146 954 | 32.3 ± 0.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Fair | 162 263 | 17.4 ± 0.5 | 89 677 | 18.7 ± 0.4 | 72 586 | 16.0 ± 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Poor | 67199 | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 36 570 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 30 629 | 6.7 ± 0.3 |

Note: SE = standard error

In our prespecified multivariate model, the adjusted odds ratio estimate of receiving retiree health insurance in 2013–14 was 0.87 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.77–0.99) compared with 2005 (Table 2). This represents a 13% decrease in the odds of a retiree receiving coverage. While we found that several other variables were statistically associated with having coverage (Table 2), the decrease in the odds ratio estimates after adjusting for confounding is almost solely attributable to household income. People earning in the second quintile had 2.71 times the odds of receiving coverage compared with people in the first quintile (i.e., those who were poorer) in the adjusted analysis. Those earning in the fourth quintile had the highest odds of having retiree coverage. In other words, despite an increase in the relative income of retirees between the survey waves, there was not a corresponding increase in the availability of retiree coverage.

Table 2:

Results from logistic regression: the association between survey year (reference 2005 cycle) and availability of retiree health insurance (yes/no)

| Variable | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Survey year | ||

| 2005 cycle (cycle 3.1) | 1 | 1 |

| 2013–2014 cycle | 1.02 (0.91–1.15) | 0.87 (0.77–0.99) |

| Age, yr | ||

| 65–69 | 1 | 1 |

| 70–74 | 0.87 (0.74–1.02) | 0.87 (0.74–1.02) |

| 75–79 | 0.76 (0.65–0.89) | 0.80 (0.67–0.94) |

| ≥ 80 | 0.72 (0.60–0.85) | 0.84 (0.70–1.00) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.23 (1.09–1.38) | 1.01 (0.89–1.15) |

| Urban/rural dwelling | ||

| Rural | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 1.36 (1.18–1.56) |

| Total household income — provincial quintile | ||

| Quintile 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Quintile 2 | 2.88 (2.41–3.44) | 2.70 (2.26–3.25) |

| Quintile 3 | 4.36 (3.65–5.20) | 4.01 (3.31–4.86) |

| Quintile 4 | 5.73 (4.65–7.07) | 5.20 (4.18–6.48) |

| Quintile 5 | 4.99 (3.91–6.37) | 4.46 (3.45–5.76) |

| Highest level of education within household | ||

| Did not complete secondary | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary graduate | 1.69 (1.42–2.02) | 1.31 (1.08–1.58) |

| At least some postsecondary | 1.98 (1.72–2.29) | 1.13 (0.96–1.32) |

| Number of chronic illness(es) | ||

| None | 1 | 1 |

| 1 or 2 | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) |

| 3 or 4 | 0.86 (0.72–1.03) | 1.18 (0.96–1.45) |

| ≥ 5 | 0.49 (0.34–0.69) | 0.73 (0.49–1.10) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single/never married | 1 | 1 |

| Common-law | 1.82 (1.09–3.03) | 1.42 (0.83–2.43) |

| Married | 1.79 (1.38–2.32) | 1.58 (1.19–2.10) |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 0.89 (0.68–1.16) | 1.04 (0.78–1.39) |

| Self-reported health status | ||

| Excellent | 1 | 1 |

| Very good | 0.88 (0.74–1.05) | 0.93 (0.77–1.12) |

| Good | 0.77 (0.64–0.93) | 0.89 (0.74–1.08) |

| Fair | 0.61 (0.50–0.74) | 0.81 (0.65–1.01) |

| Poor | 0.48 (0.37–0.62) | 0.71 (0.54–0.93) |

Note: CI = confidence interval.

Using estimates from the multivariate logistic regression, we found that the absolute decrease in predicted probability of receiving retiree health insurance from 2005 to 2013–2014 ranged from 0.6% to 3.4% depending on personal characteristics (Table 3). From 2014 population estimates from Statistics Canada of people over the age of 65 years and given that approximately 16% of respondents over 65 years of age were excluded from our sample as they were still working, we estimate that approximately 11 000 to 62 000 Ontario residents were not receiving retiree health insurance.25 In both study years, the segment of the population with the lowest predicted probability of receiving retiree coverage was older people, with lower levels of education and income in the household. In contrast, the population with the highest predicted probability of receiving coverage was people with higher levels of education, with a household income in the fourth quintile.

Table 3:

Predicted probability of receiving retiree health insurance in 2005 and 2013–2014, derived from estimates of logistic regression

| Characteristics | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2013–2014 | Absolute change | Relative change | |

| Age 65–69 yr, married, urban dwelling, 1 or 2 chronic illnesses, second income quintile, at least some postsecondary education, very good health | ||||

| Male | 52.61 | 49.26 | −3.35 | −6.37 |

| Female | 52.35 | 49 | −3.35 | −6.40 |

| Age 65–69 yr, married, urban dwelling, 1 or 2 chronic illnesses, fourth income quintile, some postsecondary education, very good health | ||||

| Male | 59.02 | 55.74 | −3.28 | −5.55 |

| Female | 58.77 | 55.48 | −3.28 | −5.59 |

| Age 65–69 yr, married, urban dwelling, 1or 2 chronic illnesses, second income quintile, some postsecondary education, very good health | ||||

| Male | 42.84 | 39.6 | −3.25 | −7.58 |

| Female | 42.59 | 39.35 | −3.24 | −7.61 |

| Age 65–69 yr, married, urban dwelling, 1 or 2 chronic illnesses, first income quintile, some postsecondary education, very good health | ||||

| Male | 21.68 | 19.49 | −2.19 | −10.10 |

| Female | 21.5 | 19.33 | −2.18 | −10.12 |

| Age 70–74 yr, widowed, urban dwelling, 1 or 2 chronic illnesses, first income quintile, secondary school graduate, very good health | ||||

| Male | 14.39 | 12.81 | −1.57 | −10.94 |

| Female | 14.26 | 12.7 | −1.56 | −10.96 |

| Age 75–79 yr, widowed, rural dwelling, 1 or 2 chronic illnesses, first income quintile, secondary school graduate, very good health | ||||

| Male | 11.03 | 9.78 | −1.25 | −11.32 |

| Female | 10.92 | 9.68 | −1.24 | −11.33 |

| Age ≥ 80 yr, never married, rural dwelling, ≥ 5 chronic illnesses, first income quintile, did not complete secondary school, poor health | ||||

| Male | 5.02 | 4.42 | −0.60 | −12.00 |

| Female | 4.97 | 4.38 | −0.60 | −12.00 |

Sensitivity analysis

We chose to use income quintiles to better compare the odds of having retiree coverage over time between groups on the basis of relative incomes. However, we performed a sensitivity analysis using reported household incomes, categorized in $20 000 increments up to $80 000 and more. The adjusted odds ratio using this revised income variable was very similar to the results presented above (adjusted odds ratio 0.86, 95% CI 0.74–0.98). We also analyzed each insurance type individually to ensure that 1 type did not bias our original estimate using our aggregated variable. These analyses yielded odds ratio point estimates similar to our original estimate, but with wider confidence intervals (data not shown).

Interpretation

Employer-sponsored health insurance remains an important mechanism through which many Canadians, including retirees, access important forms of health care. We found that the adjusted rates of employer coverage for retirees declined over time. These findings suggest that, much like in the United States,15,28 the odds of a retired employee receiving coverage have decreased for comparable populations over the past decade in Ontario. From population estimates, up to 62 000 Ontario residents over the age of 65 years were potentially affected by this trend. The public health implications of this finding may be important, as Canadians often rely on private insurance provided by employers to afford health treatments that are not publicly covered.3,5,6

The results of this study explain some of the observations in prior research. Out-of-pocket health-related expenses from 1998 to 2009 increased substantially, with premiums for private health insurance (including employer coverage) being prominent expenses.29 Additionally, a growing proportion of Canadian households are spending more than 10% of their income on health expenses.29 Our results also corroborate previous industry surveys conducted in the province, which found that many employers had plans to reduce the coverage they provide.16 As private insurance helps offset the out-of-pocket costs for treatments,3,5,6 the decrease in coverage availability observed in our study may be linked to evidence of increased expenditures by Canadian households to obtain items such as dental services and prescription drugs.29 Taken together, current evidence suggests that private insurance plans, most of which are employer sponsored, are becoming more expensive for Canadians and provide less extensive coverage, with coverage availability also being negatively affected. Additionally, if the changes observed in our study are occuring in other provinces, they may affect access to medicines to an even greater degree than in Ontario, as Ontario seniors receive generous public subsidies for prescription drugs under the Ontario Drug Benefits program.30

As previously discussed, much of our finding is attributable to changes in the household income structure of retirees. Indeed, in examining the makeup of our cohort in the 2 time periods, respondents in 2013–2014 reported income that put them in a higher quintile (relative to the entire province) than those in 2005. It has been found previously that private insurance availability (through an employer or otherwise) is associated with one’s income.5,8,9,31 Thus, with more people reporting higher household incomes, it may appear that retiree coverage availability was maintained between 2005 and 2013–2014. However, as the adjusted analysis showed, the odds of having retiree health insurance in fact decreased over this period, after taking into account income and other confounders.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, the data are derived from 2 cross-sectional surveys and may be subject to recall bias. However, it seems unlikely that knowledge about employer coverage would have been different among the 2 cohorts. Second, we were not able to assess historical employment status and it is possible that respondents did not have retiree coverage because they were not employed previously. Owing to the survey structure, we also had to assume that people over the age of 75 years were not employed at the time of the survey. Lastly, we were only able to examine the association between receiving coverage and time by using 2 survey cycles. The results may oversimplify how retiree coverage has changed over time, especially given prior research that observed extensive use of cost-controlling mechanisms among private insurance plans generally (e.g., increased premiums, cost-sharing and deductibles).17 However, given that discontinuing coverage is the most severe form of cost control, we feel these results provide a potentially important body of preliminary evidence that warrants further investigation. Future studies should investigate the proportion of retirees experiencing increased policy premiums or increased cost-sharing for treatments.17

Conclusion

The decrease in retiree health insurance availability is a potential public health issue, as cost-related nonadherence to medically necessary treatments may subsequently increase adverse health outcomes and health resource utilization. While older Canadians currently have among the lowest rates of problems with drug affordability in Canada,32 this might change if coverage availability declines. Further, as costs continue to rise, the decline in the availability of benefits may accelerate. This potential burden on the public system may provide impetus for policy-makers to further study other important employer health insurance trends in Canada such that appropriate policy action may be taken to maintain access to essential treatments in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This analysis was funded by a Foundation Scheme Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-148412, principal investigator: Michael Law). Dr. Law received salary support through a Canada Research Chair in Access to Medicines and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Mieke Koehoorn for her contribution to this research.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Michael Law has consulted for Health Canada and the Hospital Employees’ Union and acted as an expert witness for the Attorney General of Canada. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Fiona Chan developed the research question and the empirical approach, analyzed the data and drafted all material related to the employer health insurance analysis. Michael Law, Kimberlyn McGrail and Sumit Majumdar provided guidance throughout the research process. They contributed substantially to the conception and design of the analysis and the interpretation of the data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/1/E15/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Law MR, Kratzer J, Dhalla IA. The increasing inefficiency of private health insurance in Canada. CMAJ. 2014;186:E470–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allin S, Hurley J. Inequity in publicly funded physician care: What is the role of private prescription drug insurance? Health Econ. 2009;18:1218–32. doi: 10.1002/hec.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quiñonez C, Figueiredo R. Sorry doctor, I can’t afford the root canal, I have a job: Canadian dental care policy and the working poor. Can J Public Health. 2010;101:481–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03403968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ngo G, Trope G, Buys Y, et al. Significant disparities in eyeglass insurance coverage in Canada. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018;53:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allin S, Law MR, Laporte A. How does complementary private prescription drug insurance coverage affect seniors’ use of publicly funded medications? Health Policy. 2013;110:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kratzer J, Cheng L, Allin S, et al. The impact of private insurance coverage on prescription drug use in Ontario, Canada. Healthc Policy. 2015;10:62–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devlin RA, Sarma S, Zhang Q. The role of supplemental coverage in a universal health insurance system: some Canadian evidence. Health Policy. 2011;100:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramraj C, Sadeghi L, Lawrence HP, et al. Is accessing dental care becoming more difficult? Evidence from Canada’s middle-income population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locker D, Maggirias J, Quiñonez C. Income, dental insurance coverage, and financial barriers to dental care among Canadian adults. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:327–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dormuth CR, Maclure M, Glynn RJ, et al. Emergency hospital admissions after income-based deductibles and prescription copayments in older users of inhaled medications. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1038–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley J, et al. Adverse events associated with prescription drug cost-sharing among poor and elderly persons. JAMA. 2001;285:421–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman DP, Joyce G, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298:61–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bull D. The end of retiree benefits? Benefits Canada. 2015. Oct 27,

- 14.National health expenditure trends, 1975 to 2017. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2017. [accessed 2018 Apr 26]. Available: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/nhex2017-trends-report-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuart B, Singhal PK, Fahlman C, et al. Employer-sponsored health insurance and prescription drug coverage for new retirees: dramatic declines in five years. Health Aff (Project Hope) 2003;(Suppl Web):W3-334–41. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West D. Cost trends in health benefits for Ontario businesses: analysis for discussion. Toronto: Mercer (Canada); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kratzer J, McGrail KM, Strumpf E, et al. Cost-control mechanisms in Canadian private drug plans. Healthc Policy. 2013;9:35–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan SG, Daw JR, Law MR. Rethinking pharmacare in Canada. Toronto: CD Howe Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan SG, Daw JR. Canadian pharmacare: looking back, looking forward. Healthc Policy. 2012;8:14–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian life and health insurance facts 2017. Ottawa: Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association; 2017. [accessed 2018 Jan 23]. Available: http://clhia.uberflip.com/i/878840-canadian-life-and-health-insurance-facts-2017/17? [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Definitions, data sources and methods. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2016. [accessed 2016 Oct 14]. Available: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) Cycle 3.1 (2005): public use microdata file (PUMF) user guide. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) annual component: user guide 2014 and 2013–2014 microdata files. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vittinghoff E, Glidden D, Shiboski S, et al. Regression methods in biostatistics. 2nd ed. New York: Springer New York; 2012. Logistic regression; pp. 139–202. [Google Scholar]

- 25.CANSIM - 051-0001 — Estimates of population, by age group and sex for July 1, Canada, provinces and territories CANSIM (database) Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2016. [accessed 2017 Aug 9]. Available: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a47. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas S, Wannell B. Combining cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey. Health Rep. 2009;20:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Policy #89: Research involving human participants. Vancouver: The University of British Columbia Board of Governors; 2016. [accessed 2016 Oct 18]. Available: http://universitycounsel.ubc.ca/files/2012/06/policy89.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchmueller TC, Monheit AC. Employer-sponsored health insurance and the promise of health insurance reform. Inquiry. 2009;46:187–202. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_46.02.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Law MR, Daw JR, Cheng L, et al. Growth in private payments for health care by Canadian households. Health Policy. 2013;110:141–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Get coverage for prescription drugs. Government of Ontario; [accessed 2017 Aug 15]. Available: www.ontario.ca/page/get-coverage-prescription-drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dewa CS, Hoch J, Steele L. Prescription drug benefits and Canada’s uninsured. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2005;28:496–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Law MR, Cheng L, Kolhatkar A, et al. The consequences of patient charges for prescription drugs in Canada: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. 2018;6:E63–70. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20180008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.