Abstract

Background

Flow-diverter stents (FDSs) have revolutionised the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. However, associated dual antiplatelet treatment is mandatory. We investigated the biocompatibility of three proprietary antithrombogenic coatings applied to FDSs.

Methods

After Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval, four domestic juvenile female dogs (weight 19.9 ± 0.9 kg, mean ± standard deviation) were commenced on three different oral antiplatelet regimes: no medication (n = 1), acetylsalicylic acid (n = 2), and acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel (n = 1). Four p64 FDSs were randomly implanted into the subclavian, common carotid, and external carotid arteries of each dog, including both uncoated p64 stents and p64 stents coated with three different antithrombogenic hydrophilic coating (HPC). Angiography and histological examinations were performed. Wilcoxon/Kruskal-Wallis and ANOVA were used with p value < 0.05 considered as significant.

Results

Minimal inflammatory cell infiltration and no device-associated granulomatous cell inflammation were observed. No significant difference in adventitial inflammation (p = 0.522) or neointimal/medial inflammation (p = 0.384) between coated and uncoated stents as well as between the different stent groups regarding endothelial cell loss, surface fibrin/platelet deposition, medial smooth muscle cell loss, or adventitial fibrosis were found. Acute self-limiting thrombus formed on 6/16 implants (37.5%), and all of the thrombi were noted on devices implanted in the common or external carotid artery irrespective of the surface coating. Two of 12 p64 HPC-coated stents (16.7%) and 1/4 uncoated p64 stents (25%) showed severe or complete stenosis at delayed angiography.

Conclusions

In these preliminary in vivo experiments, HPC-coated p64 FDSs appeared to be biocompatible, without acute inflammation.

Keywords: Biocompatible materials, Disease models (animal), Intracranial aneurysm, Materials testing, Stents

Key points

The hydrophilic coating (HPC) can be applied to p64 flow-diverter stents.

The HPCs do not cause acute inflammation in the vessel wall.

Hydrophilic coated p64 flow-diverter stents appear to be biocompatible in initial in vivo tests.

Background

The introduction flow-diverter stents (FDSs) to the arena of interventional neuroradiology represented one of the most important breakthroughs for the specialty in recent times. These devices allowed not only the treatment of intracranial aneurysms but also the reconstruction of the parent vessel. Similarly, these devices are also being used in the peripheral circulation [1].

Although the exact mechanism of action of FDSs is unknown, it is believed they have a biphasic mechanism. Initially, the FDS redirects flow away from the aneurysm and promotes intra-aneurysmal stasis and thrombosis, which stabilises the aneurysm; subsequently, neointimal growth along the FDS struts remodels the vessel wall and completes the exclusion of the aneurysm from the circulation [2]. A wide variety of FDSs exists with newer devices entering the marketplace designed to target specific problems. One issue that is yet to be conclusively resolved is the need for antiplatelet medication when FDSs are implanted. This necessary medication is not without inherent risks. Similarly, there is hesitancy among the neuroradiological and neurosurgical community regarding antiplatelet medication in the presence of acute subarachnoid haemorrhage. Therefore, an optimised FDS would not require antiplatelet medication.

Various stent coatings have been extensively tested for stents used in the peripheral and cardiac circulation since the early 2000s [3–7] with pre-clinical studies published throughout the preceding decade [8–14]. Recently, the pipeline embolisation device Shield (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) has entered the market. This device, the first FDS with a thromboresistant coating, has a 3-nm-thick covalently bound phosphorylcholine surface modification. Phosphorylcholine is a major component of the outer membrane of erythrocytes and has demonstrated efficacy in resisting platelet adhesion as well as intimal hyperplasia [15–17]. Although there is limited clinical information available regarding the clinical results of this new technology [18–20], it is imperative to continue the development of antithrombogenic coatings that would minimise or completely negate the requirement for antiplatelet medications.

We have recently shown that the hydrophilic coatings (HPCs) have antithrombogenic properties when tested in vitro [21], but there is little known about the in vivo biocompatibility of these coatings. We sought to determine the acute therapeutic efficacy and biocompatibility of three different hydrophilic coatings. We present the results of in vivo testing of three different proprietary HPCs (type 1, 2, and 3). We assessed the biocompatibility of uncoated and coated p64 FDSs (Phenox, Bochum, Germany) without antiplatelet medication, single antiplatelet medication (acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)), and dual antiplatelet medication (DAPT) (ASA and clopidogrel).

Methods

Animal experiments and premedication

After Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval, four domestic male dogs, of similar age, were commenced on three different oral antiplatelet medication regimes. One dog did not receive antiplatelet medication, two dogs received only ASA 1.5 mg/kg/day, and one dog received DAPT (ASA 1.5 mg/kg/day and clopidogrel 1.5 mg/kg/day). The medication was commenced 72 h prior to the planned intervention and continued for the duration of the study. The canine model was chosen as the supra-aortic vessels have an appropriate diameter for clinically available stents and flow diverters. Furthermore, in common with humans, dogs lack spontaneous endothelialisation and have a variable-enhanced coagulability that would allow a suitable assessment of the different FDSs and antiplatelet regimes. The canine model has been used previously to investigate the treatment of aneurysms with FDSs [22–25].

Flow-diverter implant procedure

All procedures were performed with the animals under general anaesthesia with acepromazine (0.2 mg/kg, intramuscularly), Telazol (5 mg/kg, intravenously), and maintenance with 2% isoflurane. The right common femoral artery was surgically exposed and a 6-Fr introducer sheath inserted. Using a 5-Fr vertebral catheter and standard 0.035-in. guidewire, angiography of the common carotid arteries (CCAs), external carotid arteries (ECAs), and subclavian arteries (SAs) was performed. After full heparinisation and activated clotting time 2–2.5 times the normal value, a 0.027-in. Marksman microcatheter (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) or Excelsior XT 27 (Stryker, Kalamazoo, USA) with 0.014-in. microwire was used to access the supra-aortic vessels.

Flow-diverter stent characteristics

The p64 is a braided flow-diverting stent composed of 64 nickel-titanium (NiTi, nitinol) wires. Two platinum wires wrapped around the shaft assist in radio-opacity. The 64 wires are grouped into 8 bundles proximally, with each bundle consisting of 8 wires. A radio-opaque marker is attached to the end of each bundle. The porosity of the device is 51–60%.

Surface HPCs

The initial results of in vitro testing of the HPCs were recently published [21]. In brief, it has been demonstrated that the coatings could be applied to both nitinol plates and nitinol wires that were subsequently used to construct p64 and p48 flow-diverter stents. The thickness of the surface coatings is from 10 to 20 nm as determined by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy analysis. The thin nature of the coatings has no influence on the surface texture of the nitinol wires used to construct the flow-diverter stents [21]. In vitro testing showed a significant reduction in the adherence of immunofluorescent CD61-positive platelets when incubated with whole blood from healthy volunteers compared to uncoated stents. Scanning electron microscopy also demonstrated minimal adherent platelets on the coated flow diverters compared to a thick layer of adherent platelets on uncoated stents [21]. To summarise, the main differences among HPC-1, HPC-2, and HPC-3 are the following: HPC-1 is a well-known polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based coating, HPC-2 is a newly developed glycan-based multilayer polymer coating, and HPC-3 is a polyphosphazene nanocoating.

Implant location

A total of 16 p64 flow-diverter stents were implanted in 4 animals with 4 stents implanted into each animal. In each animal, an uncoated p64 and 1 each of the HPC-1 p64, HPC-2 p64, and HPC-3 p64 FDSs were randomly assigned and implanted into segments of the ECA, CCA, or SA. Two implants were placed in the SAs, and 2 implants placed in the CCAs or ECAs. The devices were deployed under fluoroscopic guidance. The mean diameter of the CCA was 3.7 ± 0.23 mm (mean ± standard deviation, the ECA 3.52 ± 0.45 mm, and the SA 3.79 ± 0.36 mm). The implant locations and medications are summarised in Table 1. Control angiography was performed following implantation of the FDS and 45–60 min after the FDS implantation.

Table 1.

Test matrix of the canine models presenting the medication regimens and the locations of each stent

| Animal number | Medication | Right CCA/ECA | Left CCA /ECA | Right SA | Left SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | p64 HPC-1 | p64 uncoated | p64 HPC-2 | p64 HPC 3 |

| 2 | ASA | p64 HPC-1 | p64 uncoated | p64 HPC-2 | p64 HPC 3 |

| 3 | ASA | p64 HPC-2 | p64 HPC-1 | p64 HPC-3 | p64 uncoated |

| 4 | ASA + clopidogrel | p64 HPC-2 | p64 HPC-1 | p64 HPC-3 | p64 uncoated |

ASA acetylsalicylic acid, CCA common carotid artery, ECA external carotid artery, SA subclavian artery

Follow-up imaging

Sonographic imaging was performed to assess vessel patency on days 7, 14, and 24 after the procedure. Angiography was performed on day 28 after the procedure via the contralateral common femoral artery. Stents were graded as patent (no stenosis), with minimal stenosis (1–29% lumen diameter reduction), with moderate stenosis (30–49% lumen diameter reduction), with severe stenosis (50–99% lumen diameter reduction), and occluded (100% lumen diameter reduction). All angiographic studies were analysed by a single reader (AS) with over 15 years of experience in cerebral angiography.

Harvest and gross imaging

Euthanasia was performed by intravenous sodium pentobarbital overdose (100 mg/kg) at 28 days whilst the animals were under anaesthesia with isoflurane and following the final angiographic images. The arterial segments with the implanted FDS were surgically removed and fixed in 10% formaldehyde. All specimens were photographed and radiographed using a LX-60 cabinet radiography system (Faxitron, Arizona, USA).

Histopathology preparation

After gross imaging, the excised arterial segments were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and embedded in Spurr’s epoxy resin. After polymerisation, the transverse section from the proximal, middle, and distal ends of the FDS were taken and the cross sections adhered to plastic slides and prepared to a thickness of 32–88 μm (Exakt, Oklahoma City, USA). The slides were then polished and stained with haematoxylin and eosin stain.

Histological and morphological assessment

Morphometric analysis was performed on each segment by an independent, experienced (> 15 years) histopathologist (RV) using digital planimetry with a calibrated camera. For each prepared section, a morphometric analysis was performed and included the luminal area of the vessel, the area of the internal and external elastic laminae (IEL and EEL, respectively), and the neointimal thickness that was calculated as the distance from the IEL to the luminal border. Semiquantitative data including surface platelet/fibrin deposition; injury; medial smooth muscle loss; neointimal, medial, and adventitial inflammatory cell invasion; and medial plus adventitial haemorrhage were recorded (Table 2). Histopathological analysis was conducted by an independent pathologist (RV) blinded to the coatings.

Table 2.

Description of semiquantitative histology scores

| 0 (none) | 1 (minimal) | 2 (mild) | 3 (moderate) | 4 (severe) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelium | |||||

| Endothelial loss | None | < 25% of the circumference | 25–50% of the circumference | 51–75% of the circumference | > 75% of the circumference |

| Tissue matrix | |||||

| Surface (fibrin/platelet deposition) | None | Minimal, focal | Mild, multifocal | Moderate, regionally diffuse | Severe, marked diffuse, or total luminal occlusion |

| Inflammation | |||||

| Intima/media | None | < 20 inflammatory cells/HPF in < 25% of area | 21–100 inflammatory cells/HPF in 25–50% of area | 101–150 inflammatory cells/HPF > 51–75% of area | > 150 inflammatory cells/HPF > 75% of area |

| Adventitia | None | < 25% of area | 25–50% of area | > 51–75% of area | > 75% of area |

| Haemorrhage | |||||

| Media | None | Focal, occasional | Multifocal and regional | Regionally diffuse | 100% red blood cells |

| Adventitia | None | Focal, occasional | Multifocal and regional | Regionally diffuse | 100% red blood cells |

| Medial cell loss | |||||

| Medial smooth muscle loss (depth) | None | < 25% of medial thickness | 25–50% of medial thickness | 51–75% of medial thickness | > 75% of medial thickness |

| Medial smooth muscle loss (circumference) | None | < 25% of circumference | 25–50% of circumference | 51–75% of circumference | > 75% of circumference |

| Adventitial fibrosis | |||||

| Adventitial fibrosis | None | < 25% of the area | 25–50% of the area | 51–75% of the area | > 75% of the area |

| Medial injury/rupture | |||||

| Medial injury | None | Partial disruption involving the medial wall (focal disruption of the internal elastic lamina) | Complete medial disruption with containment (intact external elastic lamina) | Complete disruption of the arterial wall involving the media | Complete disruption of the arterial wall involving the media |

HPF high-power field

The slides were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and all sections were examined by light microscopy. Inflammatory cells were counted per area score as follows: 0/none (no inflammatory cells), 1/minimal (< 20 inflammatory cells per high power field in < 25% of area), 2/mild (21–100 inflammatory cells per high power field in 25–50% of area, 3/moderate (101–150 inflammatory cells per high power field in 51–75% of area, and 4/severe (> 150 inflammatory cells per high power field in > 75% of area).

Additionally, the media area (EEL area minus IEL area), neointimal area (IEL minus luminal area), and percent luminal stenosis (1 minus [luminal area/IEL area] × 100) were also calculated.

Biocompatibility, for the purpose of this study, was defined as a non-significant difference in the degree of inflammation between the uncoated p64 stents and the HPC-coated p64 stents.

Statistical analysis

For morphometric measurements, ANOVA was used for unpaired comparisons to calculate the significance of differences between the cumulative frequency distribution of coating groups. Semiquantitative (ordinal) data (including surface platelet/fibrin deposition, injury, medial smooth muscle cell loss, neointimal/medial and adventitial inflammation, medial and adventitial haemorrhage, and fibrin) were compared using the non-parametric Wilcoxon/Kruskal-Wallis (rank sums) test (Table 2). A p value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 16 devices were implanted in 4 animals. There was no morbidity or mortality during the intervention or after the procedure (mortality and overall morbidity 0%). None of the dogs demonstrated any new neurological symptoms during the follow-up period (neurological morbidity 0%).

Intra-operative angiography results

No antiplatelet medication

Two p64 FDSs (one uncoated and one HPC-1) were implanted in the CCA/ECA of animals that did not receive any antiplatelet medication. Transient small thrombi were seen on both of these devices during the implantation procedure; however, in both cases, the thrombus did not progress to complete occlusion of the vessel on the angiography performed at the end of the procedure. There were no thrombi seen on the HPC-2 p64 and HPC-3 p64 implants in the SAs.

Single antiplatelet and dual antiplatelet medication

In the two animals given ASA only, four FDSs were implanted in the CCA/ECA (animal 2, HPC-1 p64 stent and uncoated p64 stent; animal 3, HPC-1 p64 stent and HPC-2 p64 stent). Transient small thrombi were seen on all the implants in the CCA/ECA. There were no thrombi seen on the FDSs implanted in the SAs (animal 2, HPC-2 p64 stent and HPC-3 p64 stent; animal 3, HPC-3 p64 stent and uncoated p64 stents) (Figs. 1, 2, 3). There was no evidence of thrombus formation on any of the FDSs implanted in the animal receiving DAPT.

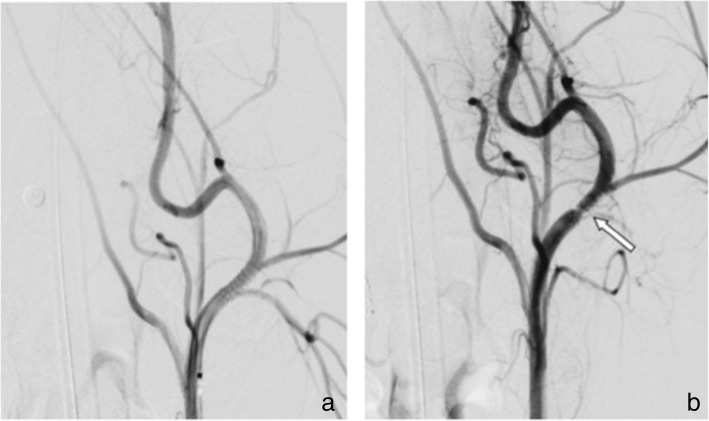

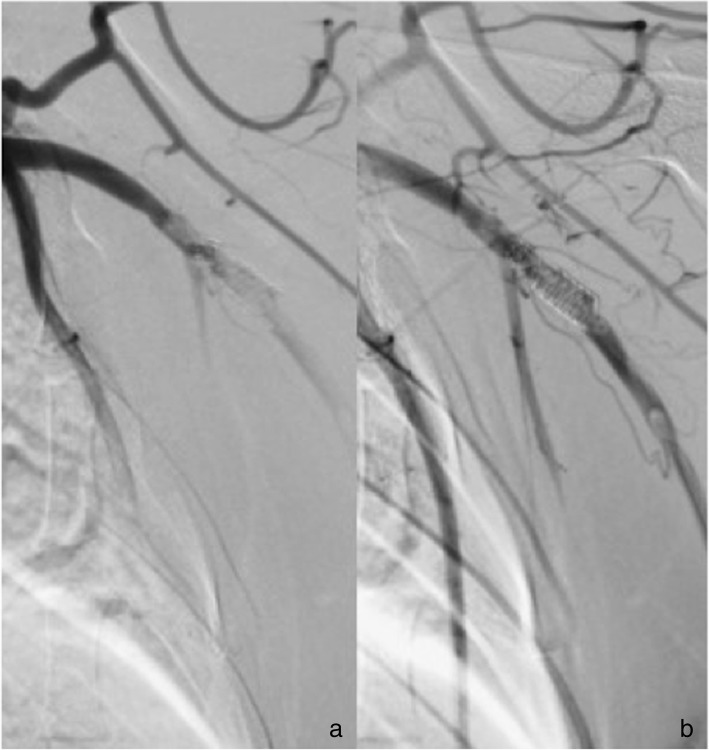

Fig. 1.

Subtracted angiographic series of the left external carotid artery of subject number 2 (treated with ASA only), implanted with an uncoated p64 device. a The FDS immediately after its implantation. b The formation of multiple thrombus in the acute phase (white arrow), 30 min after implantation

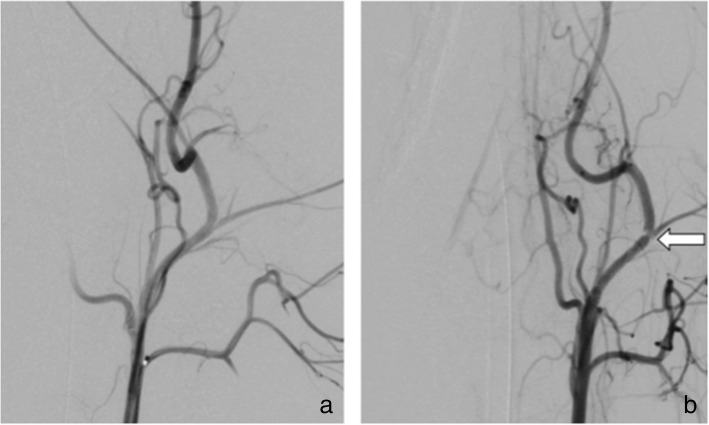

Fig. 2.

Subtracted angiographic series of the left external carotid artery of subject number 3 (treated with ASA only), implanted with an HPC-1 coated p64 device. a The FDS immediately after implantation. b The FDS 22 min after implantation, with a partial, acute in-stent thrombosis (white arrow)

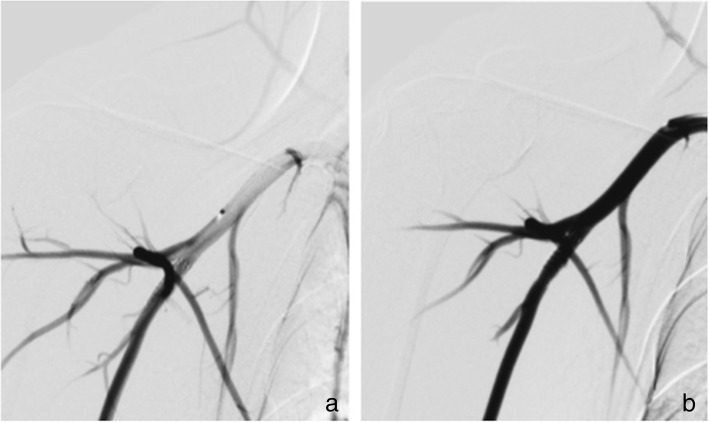

Fig. 3.

Subtracted angiographic series of the right subclavian artery of subject number 2 (treated with ASA only), implanted with an HPC-2 coated p64 device. a The FDS immediately after implantation, b 12 min thereafter. After the waiting test, the implant was free from thrombus

Overall acute self-limiting thrombus was seen to form on 6/16 (37.5%) of the implants, and all of the thrombi were noted on the FDSs implanted in the CCA/ECA irrespective of the surface coating.

Delayed angiography outcome

Angiography was performed in all animals on day 28 post-procedure.

No antiplatelet medication

A small thrombus was noted on the HPC-1 p64stents that had been implanted in the right CCA/ECA. There were no thrombi seen on the other FDSs.

Single antiplatelet and dual antiplatelet medication

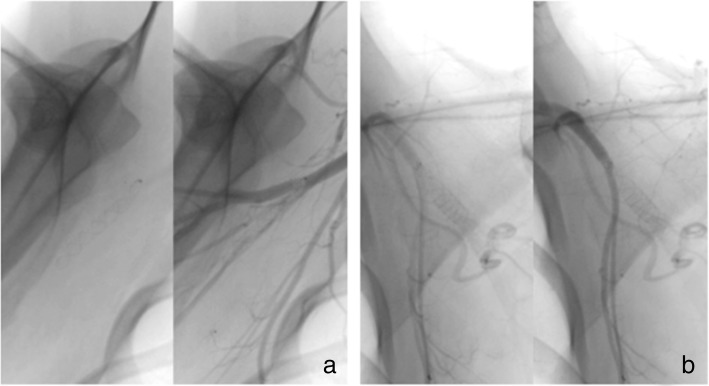

In animal 2 (treated with ASA only), both the FDSs in the CCA/ECA were patent. The HPC-2 p64 stent in the right SA was completely occluded, and the HPC-3 p64 stent in the left SA was near-completely occluded on angiography. In animal 3 (treated with ASA only), the uncoated p64 stent in the left SA was near-completely occluded on angiography (Figs. 4 and 5). One device showed minimal (1–29%) stenosis, two devices showed severe (50–99%) stenosis, and one device showed complete stenosis on angiography performed at day 28. The cases of severe and complete stenosis were seen in animals treated with ASA only. There were no thrombi seen on any of the implanted FDSs in animal 4 (treated with DAPT).

Fig. 4.

Unsubtracted angiographic series of the right subclavian artery (a) and left subclavian artery (b) of subject number 2 (treated with ASA only), implanted with HPC-2 and HPC-3 coated p64 devices, respectively, at day 28 (final angiographic control). a The right FDS almost occluded by an extensive in-stent thrombosis. b Complete occlusion of the left-sided device

Fig. 5.

Unsubtracted angiographic series of the left subclavian artery of subject number 3 (treated with ASA only), implanted with an uncoated p64 stent, at day 28 (final angiographic control). It shows the occlusion of the stent lumen by moderate in-stent thrombosis (a) with subsequent impairment of the distal arterial flow (b)

The results of the end-procedural and delayed post-procedural angiography are summarised in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Summary of the end-procedural angiography results

| Animal number | Medication | Right CCA/ECA | Left CCA/ECA | Right SA | Left SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | p64 HPC-1 transient small thrombus | p64 uncoated, transient, small thrombus | p64 HPC-2, patent | p64 HPC-3, patent |

| 2 | ASA | p64 HPC-1, transient small thrombus | p64 uncoated, transient small thrombus | p64 HPC 2, patent | p64 HPC-3, patent |

| 3 | ASA | p64 HPC-2, small clot | p64 HPC-1, small clot | p64 HPC-3, patent | p64 uncoated, patent |

| 4 | ASA + clopidogrel | p64 HPC-2, patent | p64 HPC-1, patent | p64 HPC-, patent | p64 uncoated, patent |

ASA acetylsalicylic acid, CCA common carotid artery, ECA external carotid artery, SA subclavian artery

Table 4.

Summary of the delayed post-procedural (day 28) angiography results

| Animal number | Medication | Right CCA/ECA | Left CCA/ECA | Right SA | Left SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | p64 HPC-1, minimal stenosis | p64 uncoated, patent | p64 HPC-2, patent | p64 HPC-3, patent |

| 2 | ASA | p64 HPC-1, patent | p64 uncoated, patent | p64 HPC-2, severe stenosis | p64 HPC-3, complete stenosis |

| 3 | ASA | p64 HPC-2, patent | p64 HPC-1, patent | p64 HPC-3, patent | p64 uncoated, severe stenosis |

| 4 | ASA + clopidogrel | p64 HPC-2, patent | p64 HPC-1, patent | p64 HPC-3, patent | p64 uncoated, patent |

ASA acetylsalicylic acid, CCA common carotid artery, ECA external carotid artery, SA subclavian artery

Gross and radiographic evaluation

Mild dilatation of the arterial wall was noted correlating with the position of the implanted FDSs. There were no grossly visible perforations, lacerations, or erosions of the arterial wall although small areas of haemorrhagic discolouration were noted and thought to be due to the resection procedure (Figs. 6 and 7).

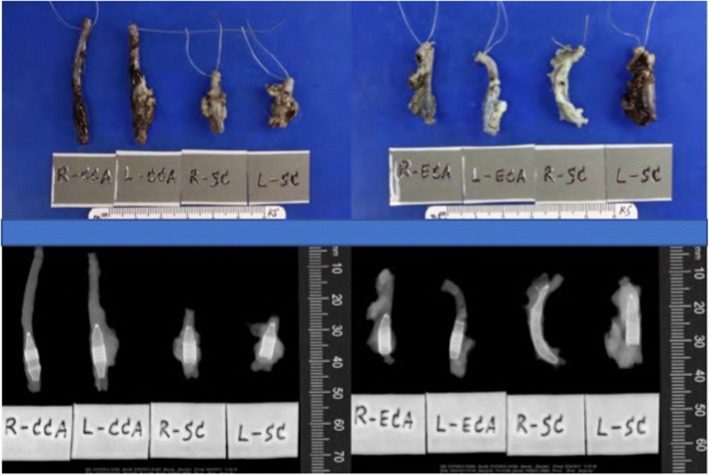

Fig. 6.

Macroscopic and radiographic analysis of the explanted vessel segments of subjects number 1 and 2

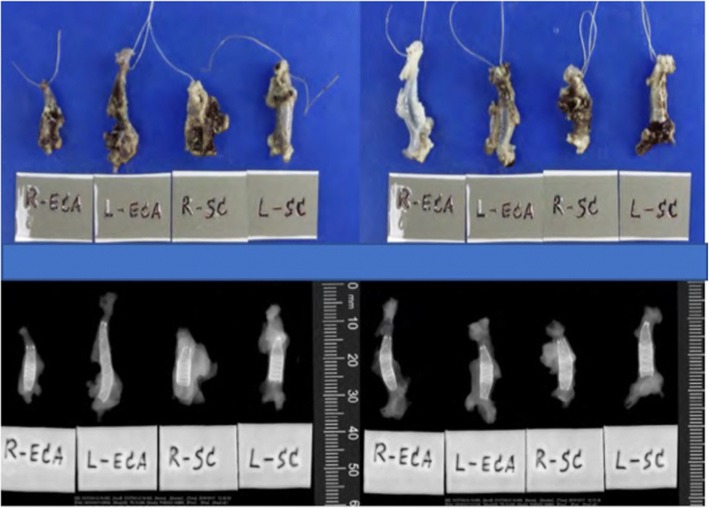

Fig. 7.

Macroscopic and radiographic analysis of the explanted vessel segments of subjects number 3 and 4

Radiography of the FDSs demonstrated them to be generally well opposed to the vessel wall. One of the proximal markers on the HPC-2 p64 FDS implanted in the right SA of animal 2 was deflected into a bifurcation branch (Fig. 6).

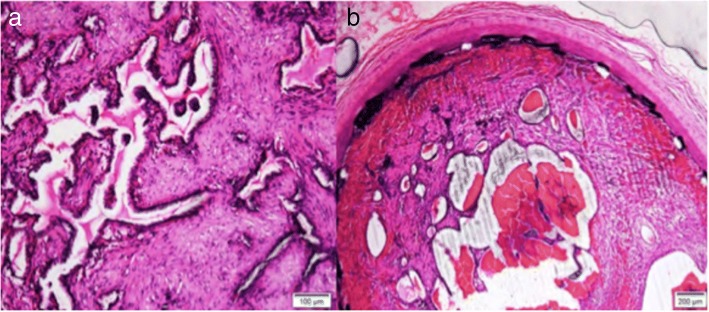

Histopathological and morphological analysis

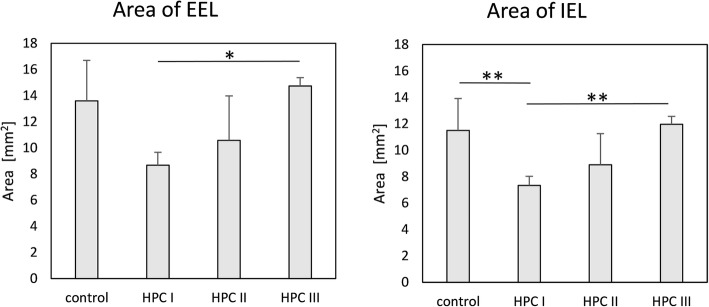

All FDSs showed good apposition to the arterial wall and virtually complete neointimal coverage along the FDS strands. There was minimal inflammatory cell infiltration seen with no device-associated granulomatous cell inflammation (Fig. 8). Near-complete endothelialisation was noted for the patent FDSs (13/16 implants, 81.3%). Neointimal growth was noted in the patent FDS segments. Morphologically, there was a significant difference in the cross-sectional EEL area between the HPC-3 p64 and HPC-1 p64 (8.67 ± 0.99 mm2 versus 14.74 ± 0.64 mm2, p = 0.013) and the IEL area between the uncoated p64 and the HPC-3 p64 as compared to the HPC-1 p64 (11.96 ± 0.61 mm2, 11.49 ± 2.43 mm2 versus 7.34 ± 0.69 mm2, p = 0.009) (Fig. 9). The results are summarised in Table 5.

Fig. 8.

Sections from explanted HPC-2-coated device from subject number 2 show luminal occlusion with re-canalised organising (mid-segment) to organised (proximal and distal sections) thrombus (a). Chronic inflammatory cells infiltration around the mesh wires are visible (b). Haematoxylin and eosin stain, × 100 magnification

Fig. 9.

Histomorphometric measurements (mean ± standard deviations) of the external elastic lamina area (left) and the internal elastic lamina area (right). Asterisks denote statistical significance using ANOVA: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Table 5.

Morphological measurements scoring

| Coating group | EEL area (mm2) | IEL area (mm2) | Lumen area (mm2) | Neointimal area (mm2) | Medial area (mm2) | Stenosis (%) | Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncoated (n = 4) | 13.59 ± 3.10 | 11.49 ± 2.43 | 7.24 ± 4.98 | 4.24 ± 4.46 | 2.11 ± 0.78 | 36.40 ± 36.54 | 0.20 ± 0.17 |

| HPC-1 (n = 4) | 8.67 ± 0.99 | 7.34 ± 0.69 | 6.03 ± 0.64 | 1.30 ± 0.24 | 1.34 ± 0.50 | 18.58 ± 2.42 | 0.11 ± 0.03 |

| HPC-2 (n = 4) | 10.57 ± 3.40 | 8.89 ± 2.37 | 5.68 ± 4.09 | 3.22 ± 2.15 | 1.67 ± 1.29 | 41.39 ± 39.47 | 0.14 ± 0.06 |

| HPC-3 (n = 4) | 14.74 ± 0.64 | 11.9 6 ± 0.61 | 7.69 ± 4.00 | 4.27 ± 3.97 | 2.78 ± 0.21 | 37.06 ± 33.07 | 0.28 ± 0.27 |

| p value | 0.013 (HPC-1 versus HPC-3) | 0.009 (HPC-1 versus HPC-3 + uncoated) | 0.862 | 0.531 | 0.124 | 0.754 | 0.564 |

Data are mean ± standard deviation

EEL external elastic lamina, IEL internal elastic lamina

Histologically, there was no significant difference between the different stent groups regarding endothelial cell loss, surface fibrin/platelet deposition, medial smooth muscle cell loss, adventitial inflammation, or adventitial fibrosis. The results are summarised in Table 6.

Table 6.

Histological scoring means, standard deviations, and Wilcoxon/Kruskal-Wallis results

| Coating group | Endothelial cell loss | Surface fibrin | Neointimal/medial | Medial smooth muscle cell loss | Medial | Adventitial | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Platelets score | Fibrin score | Inflammation score | Depth | Circumference | Injury score | Inflammation score | Fibrosis score | |

| Uncoated (n = 4) | 0.08 ± 0.17 | 0.58 ± 1.17 | 0.83 ± 1.67 | 2.50 ± 1.04 | 0.25 ± 0.50 | 0.58 ± 1.17 | 0.42 ± 0.42 | 0.92 ± 1.26 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| HPC-1 (n = 4) | 0.17 ± 0.33 | 0.50 ± 0.58 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.75 ± 0.74 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.25 ± 0.32 | 0.25 ± 0.32 | 1.50 ± 1.82 |

| HPC-2 (n = 4) | 0.50 ± 0.64 | 0.58 ± 0.69 | 0.33 ± 0.67 | 2.25 ± 0.57 | 0.50 ± 0.43 | 0.83 ± 1.23 | 0.50 ± 0.43 | 0.42 ± 0.63 | 1.50 ± 1.91 |

| HPC-3 (n = 4) | 0.25 ± 0.50 | 0.83 ± 1.26 | 0.92 ± 1.83 | 1.58 ± 0.96 | 0.42 ± 0.32 | 1.33 ± 1.22 | 0.58 ± 0.17 | 1.17 ± 0.88 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| p value | 0.731 | 0.963 | 0.762 | 0.384 | 0.183 | 0.144 | 0.514 | 0.522 | 0.181 |

Discussion

The results of this initial in vivo study demonstrate no significant difference in the inflammatory response between the three different stent coatings compared to the uncoated p64 FDSs. There was no evidence of a severe inflammatory reaction or hypersensitivity reaction to either the HPC-1, HPC-2, or HPC-3 coatings which suggests that all three coatings have a similar biocompatibility to the uncoated nitinol p64 FDS. Similarly, the coatings did not elicit a fibrotic reaction within the adventitia. Although there was no significant difference in the endothelialisation between the different coatings, the HPC-1 p64 had the lowest neointimal area suggesting that endothelialisation on this coating may be impaired relative to the other stent coatings and the uncoated p64.

Kadirvel et al. [2] have previously shown that endothelialisation of implanted FDSs is important for reconstructing the parent vessel and ultimately excluding the treated aneurysm from the circulation. In this regard, a failure of endothelialisation could ultimately lead to a failure to occlude the treated aneurysms. This finding has previously been reported for fusiform aneurysms treated with FDSs [26], and inadequate neoendothelialisation has been suggested as the underlying cause for the failure of FDSs to complete occlude some aneurysms [27].

Therefore, the lack of endothelialisation seen on the surface of the HPC-1 p64 FDSs raises concerns regarding the potential use of this coating on FDSs. Conversely, the HPC-3 FDS had a similar neointimal area compared to the uncoated p64 FDSs (4.27 ± 3.97 mm2 versus 4.24 ± 4.46 mm2) which would suggest that neointimal growth on HPC-3 coated stents is similar to that on uncoated p64 stents.

In general terms, the initial event that leads to neointima formation is that of local thrombus formation, adjacent to the stent struts. Gradually, there is an invasion of cellular components such as macrophages and α-actin-negative spindle-shaped cells accompanied by the deposition of extracellular matrix components. This eventually differentiates into a fibrocellular lesion containing α-actin-positive smooth muscle cells. Therefore, mural thrombus with a subsequent macrophage infiltration after stenting may be crucial in recruiting smooth muscle cells from the arterial wall. Platelet adherence and aggregation promote the healing process through the release of growth factors and cytokines.

These observations strongly suggest that mural thrombosis with macrophage infiltration at the earliest stage after stenting may be crucial in recruiting smooth muscle cells from the arterial wall. Indeed, platelet adherence and aggregation promote the subsequent healing process through the release of growth factors [28–30]. Interestingly, the HPC-3 p64 FDS showed a non-significantly higher surface platelet/fibrin score, and it is possible that the HPC-3 coating allows enough platelet adhesion to promote initiation of the neointima formation but insufficient platelet adhesion to cause stent thrombosis. In the recent work of Matsuda et al., [31] the pipeline embolisation device Shield showed a greater stent coverage ratio, defined as the number of struts covered with neointima/total stent struts, compared to the pipeline embolisation device Flex (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) which is a similar device but without the phosphorylcholine coating. Similarly, the authors noted that the endothelial growth on the pipeline embolisation device Shield was faster than on the pipeline embolisation device Flex, and the authors suggest that this could be due to an effect of the coating. This is of interest since not only may this device reduce the risk of acute thrombogenic complications but it may also shorten the time that patients require antiplatelet medications. Although we have not conducted a similar experiment to date, it is possible that a similar effect could be seen with the HPC-3 coating and further experiments are ongoing.

We recognise that this study has limitations, and the translation of its conclusions into clinical practice needs to be carefully considered. The follow-up period of the study was just 1 month, and therefore, the medium- and long-term effect of the device coatings is not known. Similarly, FDSs are used to treat aneurysms, and in the current experiments, aneurysms were not created so any impact of the stent coating on aneurysm occlusion is unknown. Furthermore, a limited number of subjects were used, and larger cohorts would be necessary to prove the effect of the different coatings. The large number of variables and small sample size represent another major limitation of the study.

In conclusion, HPC surface-modified p64 FDSs are biocompatible in this animal study with no evidence of severe systemic allergic reaction, local inflammatory reaction, or significant fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

Availability of data and materials

There is no further data available to share at this time.

Funding

This study was funded by Phenox GmbH (Bochum, Germany; grant number 68.242,56 USD): animal lab and animals (Jacobs Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA) 39.998,77 USD; Histopathology (CVPath Institute, Gaithersburg, MD, USA): 16.718,00 USD; consulting and travel: 1.173,22 EUR + 3.500,00 EUR + 97,76 EUR + 4.914,56 EUR = 9.685,54 EUR (= 11.525,79 USD).

Abbreviations

- ASA

Acetylsalicylic acid

- CCA

Common carotid artery

- DAPT

Dual antiplatelet medication

- ECA

External carotid artery

- EEL

External elastic lamina

- FDS

Flow-diverter stent

- HPC

Hydrophilic coating

- IEL

Internal elastic lamina

- SA

Subclavian artery

Authors’ contributions

RMM contributed to the data collection and manuscript preparation and review. PB contributed to the data collection and manuscript preparation, editing, and review. TL-H contributed to the manuscript editing and review. CB, AS, PL, RH, and HM contributed to the manuscript editing and review. HH is the study guarantor and contributed to the manuscript editing and review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval was gained (Jacobs Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA). Consent to participate: not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RMM has a proctoring agreement with Phenox until 2017. PB has a consulting and proctoring agreement with Phenox. TL-H and CB are employees of Phenox. AS declares that he has no competing interests. PL is a consultant of Phenox. RH and HM are CEOs of Phenox. HH is a co-founder and shareholder of Phenox.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Rosa Martínez Moreno and P. Bhogal are joint first authors.

References

- 1.Mauri G, Sconfienza LM, Casilli F, Massaro S, Inglese L (2013) Cardiatis multilayer stent for endovascular treatment of peripheral and visceral aneurysms: where do we stand? J Endovasc Ther 20:575–577 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Kadirvel R, Ding YH, Dai D, Rezek I, Lewis DA, Kallmes DF (2014) Cellular mechanisms of aneurysm occlusion after treatment with a flow diverter. Radiology 270:394–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Sheiban I, Carrieri L, Catuzzo B, et al. Drug-eluting stent: the emerging technique for the prevention of restenosis. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2002;50:443–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sousa JE, Costa MA, Abizaid A, et al. Lack of neointimal proliferation after implantation of sirolimus-coated stents in human coronary arteries: a quantitative coronary angiography and three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2001;103:192–195. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sousa JE, Costa MA, Abizaid AC, et al. Sustained suppression of neointimal proliferation by sirolimus-eluting stents: one-year angiographic and intravascular ultrasound follow-up. Circulation. 2001;104:2007–2011. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.098056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sousa JE, Costa MA, Sousa AG et al (2003) Two-year angiographic and intravascular ultrasound follow-up after implantation of sirolimus-eluting stents in human coronary arteries. Circulation 107:381–383 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Sousa JE, Costa MA, Abizaid A, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stent for the treatment of in-stent restenosis: a quantitative coronary angiography and three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2003;107:24–27. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000047063.22006.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozaki Y, Violaris AG, Serruys PW. New stent technologies. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1996;39:129–140. doi: 10.1016/S0033-0620(96)80022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Violaris AG, Ozaki Y, Serruys PW. Endovascular stents: a ‘break through technology’, future challenges. Int J Card Imaging. 1997;13:3–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1005703106724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whelan DM, van Beusekom HM, van der Giessen WJ. Mechanisms of drug loading and release kinetics. Semin Interv Cardiol. 1998;3:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincoff AM, Furst JG, Ellis SG, Tuch RJ, Topol EJ (1997) Sustained local delivery of dexamethasone by a novel intravascular eluting stent to prevent restenosis in the porcine coronary injury model. J Am Coll Cardiol 29:808–816 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Park SH, Lincoff AM. Anti-inflammatory stent coatings: dexamethasone and related compounds. Semin Interv Cardiol. 1998;3:191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gershlick AH (1998) Local delivery of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors using drug eluting stents. Semin Interv Cardiol 3:185–190 [PubMed]

- 14.Aggarwal RK, Ireland DC, Azrin MA, Ezekowitz MD, de Bono DP, Gershlick AH (1996) Antithrombotic potential of polymer-coated stents eluting platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antibody. Circulation 94:3311–3317 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Chen C, Lumsden AB, Ofenloch JC et al (1997) Phosphorylcholine coating of ePTFE grafts reduces neointimal hyperplasia in canine model. Ann Vasc Surg 11:74–79 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Chen C, Ofenloch JC, Yianni YP, Hanson SR, Lumsden AB (1998) Phosphorylcholine coating of ePTFE reduces platelet deposition and neointimal hyperplasia in arteriovenous grafts. J Surg Res 77:119–125 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Campbell EJ, O’Byrne V, Stratford PW, et al. Biocompatible surfaces using methacryloylphosphorylcholine laurylmethacrylate copolymer. ASAIO J. 1994;40:M853–M857. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199407000-00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanel RA, Aguilar-Salinas P, Brasiliense LB, Sauvageau E (2017) First US experience with pipeline flex with shield technology using aspirin as antiplatelet monotherapy. BMJ Case Rep. J Neurointerv Surg. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:bcr-2017-219406. 10.1136/bcr-2017-219406. Accessed 8 Jan 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Orlov K, Kislitsin D, Strelnikov N, et al. Experience using pipeline embolization device with Shield Technology in a patient lacking a full postoperative dual antiplatelet therapy regimen. Interv Neuroradiol. 2018;24:270–273. doi: 10.1177/1591019917753824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Galdámez M, Lamin SM, Lagios KG et al (2017) Periprocedural outcomes and early safety with the use of the Pipeline Flex Embolization Device with Shield Technology for unruptured intracranial aneurysms: preliminary results from a prospective clinical study. J Neurointerv Surg 9:772–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Lenz-Habijan T, Bhogal P, Peters M, et al. Hydrophilic stent coating inhibits platelet adhesion on stent surfaces: initial results in vitro. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:1779–1785. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-2036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darsaut TE, Bing F, Salazkin I, Gevry G, Raymond J (2012) Flow diverters failing to occlude experimental bifurcation or curved sidewall aneurysms: an in vivo study in canines. J Neurosurg 117:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Darsaut TE, Bing F, Makoyeva A, Gevry G, Salazkin I, Raymond J (2014) Flow diversion of giant curved sidewall and bifurcation experimental aneurysms with very-low-porosity devices. World Neurosurg 82:1120–1126 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Darsaut TE, Bing F, Salazkin I, Gevry G, Raymond J (2012) Flow diverters can occlude aneurysms and preserve arterial branches: a new experimental model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 33:2004–2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Fahed R, Gentric JC, Salazkin I, Gevry G, Raymond J, Darsaut TE (2017) Flow diversion of bifurcation aneurysms is more effective when the jailed branch is occluded: an experimental study in a novel canine model. J Neurointerv Surg 9:311–315 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Szikora I, Turányi E, Marosfoi M. Evolution of flow-diverter endothelialization and thrombus organization in giant fusiform aneurysms after flow diversion: a histopathologic study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:1716–1720. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai D, Ding YH, Kelly M, Kadirvel R, Kallmes D (2016) Histopathological findings following pipeline embolization in a human cerebral aneurysm at the basilar tip. Interv Neuroradiol 22:153–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Grainger DJ, Wakefield L, Bethell HW, Farndale RW, Metcalfe JC (1995) Release and activation of platelet latent TGF-beta in blood clots during dissolution with plasmin. Nat Med 1:932–937 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Deuel TF. Polypeptide growth factors: roles in normal and abnormal cell growth. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1987;3:443–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.03.110187.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Assoian RK, Sporn MB. Type beta transforming growth factor in human platelets: release during platelet degranulation and action on vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1217–1223. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.4.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuda Y, Jang DK, Chung J, Wainwright JM, Lopes D (2018) Preliminary outcomes of single antiplatelet therapy for surface-modified flow diverters in an animal model: analysis of neointimal development and thrombus formation using OCT. J Neurointerv Surg 11:74–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There is no further data available to share at this time.