Abstract

Since the implementation of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), rates of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) mortality, morbidity, and newly acquired infections have decreased dramatically. In fact, HIV-1-infected individuals under effective suppressive cART approach normal life span and quality of life. However, long-term therapy is required because the virus establish a reversible state of latency in memory CD4+ T cells. Two principle strategies, namely “shock and kill” approach and “block and lock” approach, are currently being investigated for the eradication of these HIV-1 latent reservoirs. Actually, both of these contrasting approaches are based on the use of small-molecule compounds to achieve the cure for HIV-1. In this review, we discuss the recent progress that has been made in designing and developing small-molecule compounds for both strategies.

Keywords: HIV latency, HIV cure, “shock and kill”, “block and lock”, latency-reversing agents, latency-promoting agents

The Current State of the HIV Type 1 Pandemic

HIV type 1 (HIV-1) is the predominant causative agent for AIDS. Transmission of the virus is mediated through exchange of certain bodily fluids (i.e., blood, semen, vaginal or rectal fluids, breast milk) through sexual contact, needle sharing, or from mother to child.1 The spread of HIV-1 has led to one of the most devastating pandemic. In fact, the AIDS pandemic has claimed the lives of 35 million people since the first cases were described in the 1980s.2 Even today, the number of individuals living with HIV-1 is estimated at 36.7 million, which makes for a global prevalence closely approaching 1%. In 2016, 2.1 million people newly acquired HIV-1 and 1.1 million passed away as result of their infection.3 These statistics clearly emphasize that this disease remains a devastating global burden.

Fortunately, the implementation of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in the late 1990s has significantly improved outcome for HIV-1 patients. For instance, in higher income countries where these drugs are more readily accessible, the life span for treated patients is approaching that of the general population.4 Furthermore, global cART implementation has led to an overall decrease in mortality and morbidity for the HIV-infected population.5 The strategy of this successful therapy relies on simultaneously targeting different steps in the viral life cycle of the virus and has since become the standard of care for all HIV-infected patients and has been supported by all international guidelines since 2015.5

cART and Its Limitations

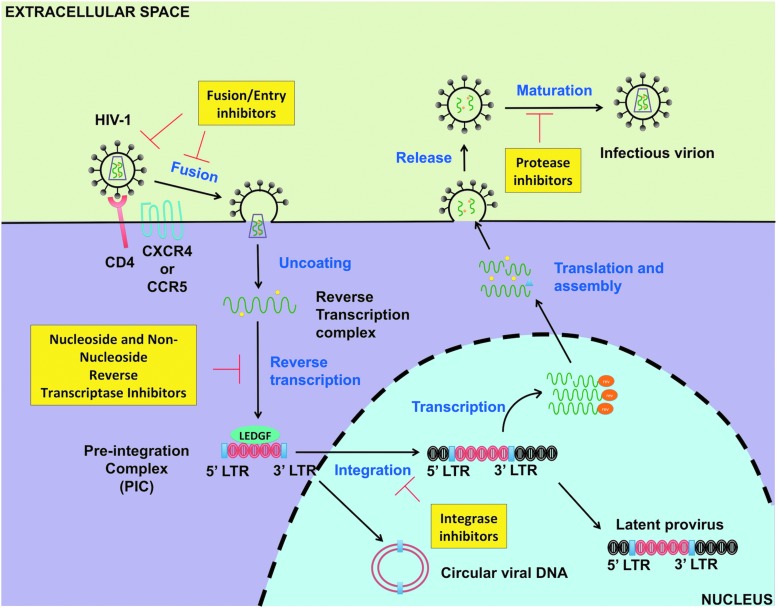

After the identification of HIV-1 in the 1980s, enormous time and effort have been put in understanding its life cycle and developing HIV-1 therapeutics. By far the most successful approach in curbing the progression of the disease in HIV-infected individuals has been the advent and implementation of cART. This regimen is based on a combination of three or more HIV-1 antiretroviral targeting different steps of active viral replication (Fig. 1). Specifically, five major classes exist: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, integrase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, and fusion/entry inhibitors6 (Fig. 1). Furthermore, within each of these classes, several clinically approved drugs have been developed.6

FIG. 1.

HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy and its targets. cART is the standard of care for all HIV-1 patients. It comprises a combination of three or more antiretroviral drugs belonging to five major classes. Specifically, these major classes are: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, integrase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, and fusion/entry inhibitors as shown in yellow rectangles. Of note, at the moment there is no clinically approved antiretroviral drugs targeting HIV-1 transcription or latency. cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; HIV-1, HIV type 1.

The reasoning behind the administration of three or more drugs stemmed from the emergence of resistance strains that were rapidly developing in patients receiving monotherapy in the early 1990s.7 In addition, several clinical trials comparing monotherapy versus combination therapy showed that cART was much more efficient at slowing AIDS progression, improving CD4+ T cell count, decreasing plasma viral load, and conferring greater survival for HIV-infected patients.7–11 In fact, this strategy has allowed for the suppression of viremia below clinical detection limits (< 20 copies/mL) for many patients, which is the standard for “aviremic” patient status. Nonetheless, despite this major progress in HIV-1 therapeutics, HIV-1 remains an incurable disease.

One of the major remaining challenges is associated with the inefficacy of cART to completely clear patients from the virus. Consequently, HIV-1 infection is nowadays considered more of a chronic infection, which is also associated with a chronic inflammatory state. Therefore, although patients are living longer and healthier lives, they are facing increasing burden from non-AIDS-related illnesses.5 Specifically, virally suppressed patients are facing higher incidence and mortality from complications such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndromes (e.g., obesity, type 2 diabetes), and non-HIV-1-related cancers.5

Such causality is thought to be associated with cART usage in addition to the chronic inflammation and immune dysfunction seen in cART-treated patients. Moreover, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) remain a major complication for infected individuals. Of note, the overall prevalence of patients suffering from cognitive impairment has remained the same. However, milder forms, such as asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment and mild neurocognitive disorder, now predominate in contrast to the most severe form (HIV-associated dementia) as opposed to the pre-cART era.5

Perhaps an even more concerning limitation of cART is that interruption of therapy unequivocally leads to the reemergence of a detectable viral load in patients within a few weeks.12 Interestingly, this observation remains true whether patients have been virally suppressed for a long time or under an intensified cART regimen.12,13 In addition, cART patients exhibit a low-level residual viremia, only detectable by sensitive assays, that is also refractory to cART intensification.14,15

Most of the current evidence suggest that both the viral rebound and residual viremia are the result of the establishment of latent proviruses in activated CD4+ T cells that revert back to the resting state early during acute infection. These latent proviruses are defined as stably integrated HIV-1 DNA genomes that are transcriptionally silent but capable of producing infectious virions de novo upon stimulation. Alternatively, ongoing low-level viral replication has also been proposed to explain viral rebound and residual viremia from CD4+ T cells and potentially other viral reservoirs.16–20

However, further investigation of latently infected CD4+ T cells has shown that the memory subsets of CD4+ T cells contain the majority of the latent proviruses.21,22 Interestingly, these cells are considered to be long-lived, self-replenishing, and refractory to cART; in fact, they are believed to be the major hurdle impeding a cure for HIV-1 because of the aforementioned properties.23–25 Therefore, to circumvent the limitations of cART and find a cure, a clear understanding of the viral reservoirs and the mechanisms involved in HIV-1 latency maintenance is warranted.

HIV Viral Reservoirs and Sites of Persistence

Resting memory CD4+ T cells

The most well-characterized HIV-1 viral reservoir in cART-treated patients are resting CD4+ T cells specifically in the memory subsets.21,23,26,27 These cells have been proposed to be directly susceptible to HIV-1 infection before becoming viral reservoirs, although this occurs inefficiently.28 Therefore, the majority of HIV-infected CD4+ T cell reservoirs are believed to be established early during acute infection after reversion to a resting state.29,30 Specifically, activated CD4+ T cells, which are the preferential cellular host for HIV-1, become infected with the virus and can revert back to a resting state if they survive the virus' cytopathic effects or the HIV-specific immune response. These resting CD4+ T cells acquire a long-live phenotype predominantly through differentiation into the central memory CD4+ T cell subset (TCM), transitional memory CD4+ T cell subset (TTM) and less commonly in effector memory T cell subset (TEM).21

These cells harbor a stably integrated HIV-1 provirus that becomes transcriptionally silent but is capable of producing infectious virions de novo if the memory CD4+ T cells are stimulated through antigen recognition or other activation stimuli. This is referred to as a true “latent” state, which is a definition also extended to any anatomic sites where reservoirs reside and can potentially reactivate from latency.31,32 Furthermore, HIV-1 latency is a contributor of the virus' ability to escape from both the immune system or antiviral effects of cART. In addition, HIV-1 latency provides a mechanism by which reseeding of viral reservoirs can occur during short burst of viral reactivation such as in “blips.”33

Interestingly, earlier characterization of the CD4+ T cell reservoir showed that it occurred at a low frequency (1 in 106 CD4+ T cells) and that 70 years of cART treatment would be necessary to completely eradicate the virus in cART patients because of the long-live nature of memory CD4+ T cells.24,25,34 However, the barrier to eradication became even more complex when another study showed that the reservoir size was 60-folds greater in resting CD4+ T cells than originally predicted.35 Specifically, it was shown that reactivation of latent provirus can be quite stochastic because only a portion of intact replication competent provirus can be induced with one or sequential administration of maximal stimulating agents.35 In other words, even in the presence of strong stimulators, an intact provirus could or could not reactivate and the processes that control this phenomenon are still under investigation.

Lastly, stem cell memory CD4+ T (TSCM) cells are another subset of long-live T cell that have recently been shown to harbor latent provirus. They constitute another important challenge to HIV-1 cure as these cells have extremely long life span, are resistant to apoptosis, and possess self-renewal capabilities.22

Other viral reservoirs or sites of viral persistence?

Other T cell subsets

In addition to TCM, TTTM, TEM, and TSCM subsets, other viral reservoirs have been proposed. For instance, T follicular helper T (TFH) cells isolated from aviremic cART-treated patients showed that these cells continuously expressed viral RNA transcripts. However, the very fact that TFH express viral RNA does not classify them as “true” latent reservoirs in comparison with TSCM or TCM subsets. Rather, these cells might be a source of viral persistence and may be implicated in low-level viral replication in aviremic cART-treated patients.36 Similarly, there is evidence showing that gut-associated CD4+ T cells and those found in lymphatic tissues of cART-treated patients might also aid in viral persistence through the mechanism of low-level ongoing viral replication.20

Lastly, naive CD4+ T cells (TN) is another cell type that should not be neglected as potential latent reservoirs. Chomont et al. showed that resting naive CD4+ T cells only represented a small fraction of the latent pool compared with resting memory CD4+ T cells.21 In fact, latency is established ∼10 times less in TN compared with memory CD4+ T cells.37,38 However, recent investigations have provided enough evidence to show that naive CD4+ T cells can establish latency both in primary models of HIV-1 latency and also naturally occurring in patients under cART therapy.38–40 Interestingly, Tsunetsugu-Yokota et al. pointed out that latent provirus in TN might be refractory to compounds being used in the “shock and kill” (discussed in “Shock and kill” section) HIV-1 cure strategy, which underlines their importance as a potential major barrier to a cure and the necessity to better understand the mechanism of latency in this T cell subset as well.39

Myeloid lineage

Cells from the myeloid lineage have also been implicated as reservoirs for HIV-1 as they are also susceptible to HIV-1 infection.41 For instance, infected monocytes have been recovered from the blood of patients even after prolonged suppressive cART therapy.42 However, these cells are short-lived and cART is very effective at controlling viral activity in the blood. Thus, their status as a latently infected cell with an inducible provirus is still not clear.41,43 However, monocytes have been suggested to be capable of supporting ongoing viral replication in cART patients and their subsequent migration and differentiation into tissue-specific macrophages may allow viral dissemination in the presence of cART rather than being a latent source for the virus.41,44

Another myeloid-derived cell that is highly permissive to HIV-1 infection is the macrophage.45 Similar to monocytes, the evidence for macrophage as a latent reservoir is still unclear.41 However, one possible mechanism for latency in macrophages is termed “preintegration” latency, which is when the reverse-transcribed viral DNA circularizes during acute replication and persists within the nucleus for integration at a later point. This is suggested because of the ability of macrophages to sustain nonintegrated viral DNA for a long time and their resistance to HIV-associated viral cytopathic effects.46–48 However, definite evidence for this form of latency occurring in patients on cART is still lacking.41

In addition, macrophages can harbor viruses in vesicle-like compartments called virus-containing compartments, which provide a protective niche for the virus to persist.49 Furthermore, studies have shown that in the primary model of monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM), viruses can be transmitted to uninfected CD4+ T cells through virological synapses (VS) potentially occuring both in acute infection or during cART-driven suppression. Nevertheless, there are insufficient data at this moment to confirm that this happens in vivo.50

In contrast, further investigations in the MDM model suggest that macrophages indeed could in theory possess the ability to go into latency and be sensitive to reactivation.51 In addition, a recent study has also shown that HIV-1 can persist in tissue macrophages and lead to viral rebound after cART interruption in a humanized myeloid-only mouse model, thus demonstrating that macrophages can potentially act as latent reservoirs.52 Finally, dendritic cells are another myeloid-derived cell type susceptible to HIV-1 infection. However, research implicating them as latent reservoirs remains very scarce although they have been proposed to play a role in the establishment of latency in resting nonproliferating memory CD4+ T cells.53

Taken together, the current data so far point to myeloid lineage cells as potential but not clearly define HIV-1 latency reservoirs in comparison with the well-established resting memory CD4+ T cells. However, these cells may help the virus to persist through different mechanisms such as ongoing viral replication, preintegration latency, and transmission through VS. Therefore, any HIV-1 cure strategy approach should consider evaluation of HIV-1 therapeutics in these distinct potential sites for viral persistence.

Hematopoietic progenitor cells

Multipotent CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) is another cell type undergoing investigation to determine if it constitutes a latent reservoir for HIV-1. These cells are located in the bone marrow and possess both self-renewing and extensive long-lived capabilities. In addition, they are known to express the entry/fusion receptors allowing for HIV-1 infection permissibility.54 Thus, they would present an ideal cellular niche for latency establishment.

Intriguingly, they have been proposed to be the potential source of the residual viremia seen in cART-treated patients based on their clonal expansion potential and longevity properties.54 Furthermore, studies by Carter et al. have shown that these cells indeed can be acutely infected by HIV-1 and harbor latent provirus susceptible to reactivation both in vitro and in animal studies.55,56 Nonetheless, two follow-up studies did not find HPCs to be contributors of the latent pool in HIV-positive, cART-treated, aviremic patients. In fact, CD34+ HPCs isolated from bone marrow aspirate from these patients did not harbor stably integrated viral DNA.57,58 Thus, the contribution and importance of HPCs as viral latent reservoirs still remain controversial and will probably warrant further investigation.

Central nervous system

Many cell types in the brain are susceptible to HIV-1 infection. Namely, perivascular macrophages, microglia, and astrocytes cells have all been demonstrated to be susceptible. In addition, integrated HIV-1 DNA has been isolated in these cells postmortem in HIV-infected subjects especially in astrocytes and microglia.59,60 However, the enigma that remains is if the virus is truly capable of establishing a reversible state of latency in the central nervous system (CNS) that can lead to de novo viral production.

For instance, astrocytes can harbor integrated viral DNA and alternate between a transcriptionally active and inactive state.61 However, there is limited evidence to show that astrocytes can produce infectious virions after reactivation; therefore, they cannot yet be considered viral latent reservoir.62 In the case of microglia cells, the evidence for them as latent reservoirs has mostly been conducted in cell line models and definite evidence in humans have not been demonstrated partly because of the difficulty of obtaining human brain-infected cells and the ethical associated considerations.62 However, Marban et al. provides a much more extensive review of the CNS as reservoir site and they argue that HIV-1 cure therapeutics strategies should not neglect the CNS as it may be an important site for viral persistence.62

“Blurred lines” of cell state influencing HIV-1 latency

Recent advances in our ability to detect viral transcription and translation have started to redefine long-held ideas about which cell “state” can harbor an active versus silent HIV-1 provirus. For instance, recent work by Chavez et al. have demonstrated that resting CD4+ T cells, classically considered to only favor latency, can also support productive viral infection and active HIV-1 transcription in vitro.63 In fact, this has also been suggested to occur in vivo as HIV-1 viral transcripts were detected in both resting and activated CD4+ T cells in HIV-infected individuals on cART.64

Furthermore, Pace and colleagues showed that in addition to viral transcription occurring in resting CD4+ T cells viral translation especially of the gag protein can occur.65 A follow-up study by the same group demonstrated that resting T cells that lost their CD4 expression were more likely to have active HIV-1 transcription and express gag, defining a resting CD4−/CD8− T cell compartment as another viral source of persistence.66 Actually, in vivo corroboration of the existence of such a compartment has been described even in the context of cART treatment.64 Moreover, the application of single cell analysis technology has shown that active transcription generally persists also in freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from cART-treated, aviremic patients and that these actively transcribing cells may be implicated in HIV-1 rebound viremia after treatment interruption.67,68

In contrast, there is also evidence that activated CD4+ T cells, which are usually thought to support active transcription as opposed to latency, can harbor a provirus that is silenced despite their activated state. Specifically, Chavez et al. illustrated in vitro that activated CD4+ T cells can establish latent HIV-1 infection without necessarily returning to the resting state.63

Consequently, on the one hand there is growing evidence that both the resting state and the activated state of T cells can harbor latent HIV-1 provirus; on the other hand, both resting and activated cells can support active transcription. These relatively new concepts are important considerations for evaluating and elaborating comprehensive cure strategies for HIV-1 going forward.

Mechanisms of HIV-1 Latency

Despite the potential of activated CD4+ T as potential carriers of latent provirus, most of the evidence still points to the latency establishment in resting memory CD4+ T cells as the major barrier to an HIV-1 cure.31,32 Not surprisingly, the major concern for HIV-1 scientists has been to elucidate the biological processes involved in latency maintenance following its establishment in resting memory CD4+ T cells. Although we still lack a complete understanding of the latter processes, several mechanisms have been proposed and provided insights on how to develop therapeutic approaches for a cure.

Regulation at the chromatin level

Host cellular DNA is organized into chromatin. Of note, chromatin can rearrange itself to regulate several biological nuclear processes such as DNA repair, replication, or transcription.69 For instance, chromatin can assume a more relaxed state called euchromatin that then allows transcription factors access to host genes thus promoting their expression. Alternatively, chromatin can also become more compact, a structure termed heterochromatin, during cell division or to repress gene expression.69 This dynamic range seen in the structure of chromatin is primarily associated with its organization into nucleosomes (nuc), which are the structural units of chromatin.

Specifically, a nucleosome comprises 150 base pair (bp) left-handed DNA helix that wraps around an octomer complex composed most commonly of the following four histone proteins, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Internucleosome regions are typically spaced by 80 bp associated with linker histone H1.70 Of interest, nucleosome stability, which is influenced by chromatin remodelers (e.g., switch/sucrose non-fermentable [SWI/SNF] complex, facilities chromating transcription [FACT] complex) and post-translational modifications of histones (e.g., acetylation, methylation, or phosphorylation), regulates the compaction or relaxation state of chromatin.70–72 As HIV-1 integrates into the host chromatin, viral gene expression from proviral DNA is therefore also susceptible to chromatin regulation involving the location of the integrated viral genome and the epigenetic modifications occuring at the proviral site, with the latter heavily implicated in the maintenance of HIV-1 latency.73,74

Histone acetylation

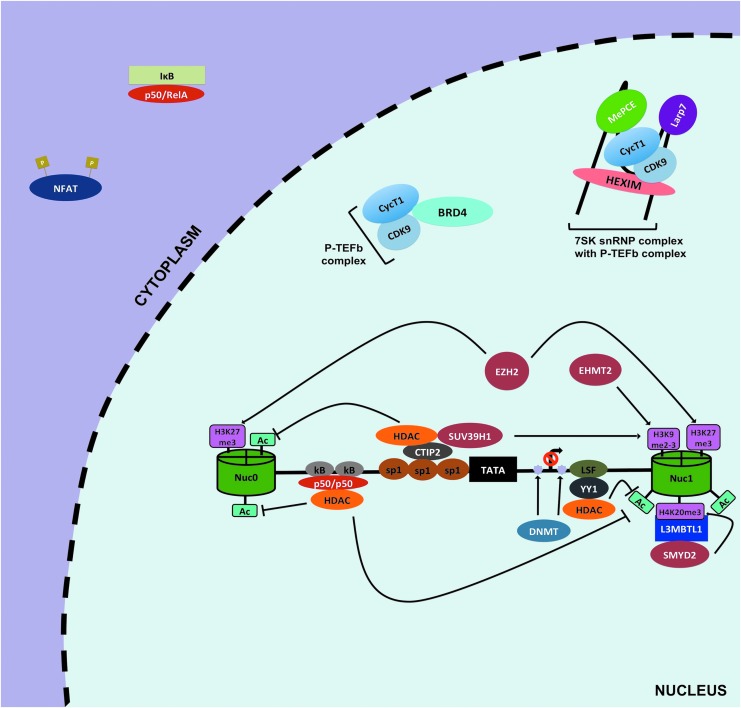

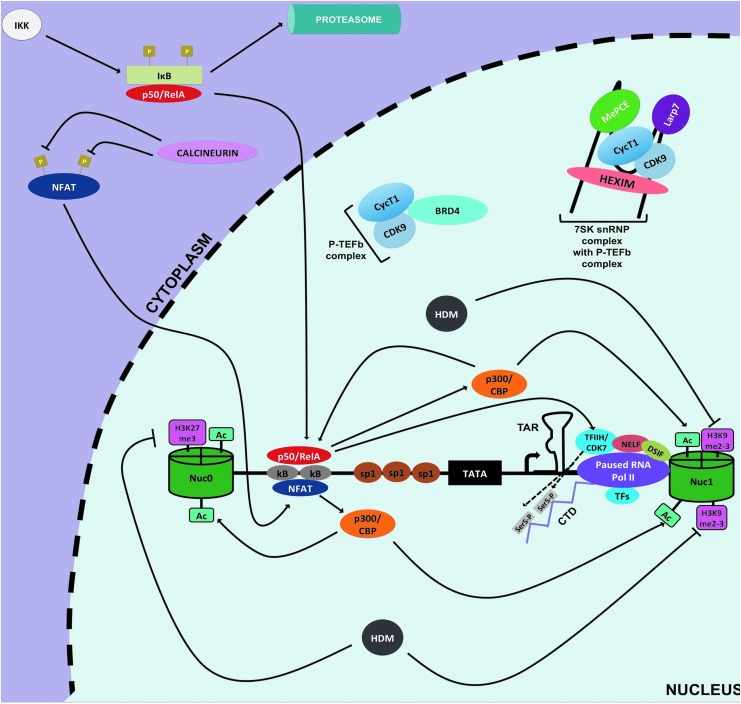

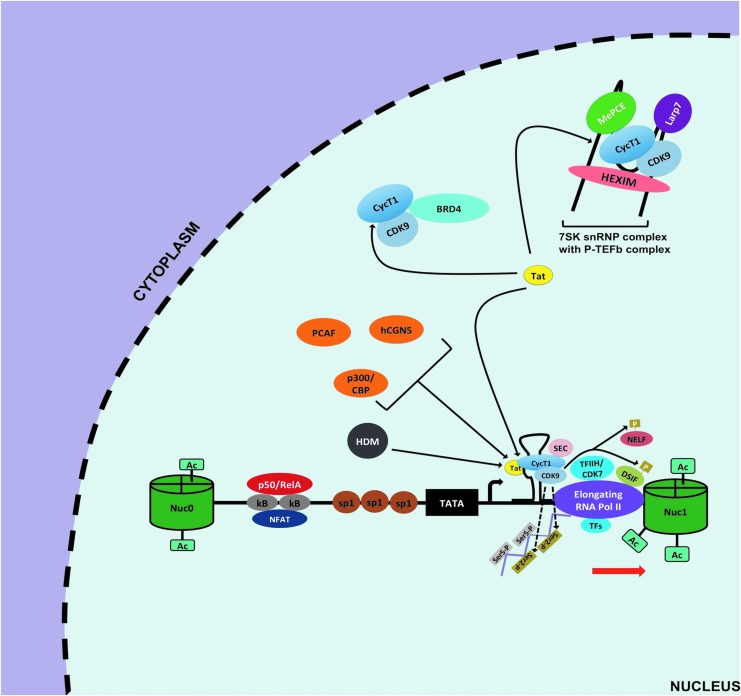

The HIV-1 promoter region, also known as 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR), is characterized by the presence of two nucleosomes, nuc-0 and nuc-1, interspaced by a nucleosome-free region regardless of the site of integration75 (Fig. 2). These nucleosomes like all host nucleosomes are susceptible to epigenetic changes. However, studies have focused on nuc-1 because it is considerably remodeled in the context of HIV-1 transcription. Moreover, nuc-1 is located at the junction where RNA polymerase II (Pol II) pauses before undergoing successful Tat-mediated transcriptional elongation76 (Figs. 3 and 4).

FIG. 2.

Silencing of HIV-1 transcription at 5′ LTR. The HIV-1 5′ LTR comprises two nucleosomes, nuc-0 and nuc-1 (green cylinders), and an interspaced nucleosome free region containing trasncription factor binding sites for HIV-1 transcription regulation (horizontal black in between two cylinders). During latency, proper HIV-1 gene expression is impeded by several mechanisms. First, repressive host transcription factors such as inactive NF-κB (p50/p50), LSF, YY1, or CTIP2 are recruited at the 5′ LTR, and in turn recruit HDACs (shown in orange) and/or HMTs (shown in burgundy) to modify nuc-0 and nuc-1 at 5′ LTR. Typically, HDACs leads to deacetylation of nuc-0 and nuc-1, whereas HMTs methylate specific sites on these nucleosomes (shown in pink rectangles). These modifications result in a less accessible LTR region, thereby effectively preventing proper viral transcription. Furthermore, DNA methylation of CpG at LTR by DNMT is thought to play a role in HIV-1 silencing (violet stars). Another mechanism that contributes to latency is the cytoplasmic sequestration of active NF-κB and NFAT. Finally, the sequestration of active P-TEFb by inhibitory complex 7SK snRNP or BRD4 also highly contributes to HIV-1 latency. 7SK snRNP, 7SK small nuclear ribonucleoprotein; BRD4, bromodomain-containing protein 4; CTIP2, COUP transcription factor 2; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; HDACs, histone deacetylase transferases; HMTs, histone methyltransferases; nuc, nucleosome; LSF, Late SV40 factor; LTR, long terminal repeat; P-TEFb, positive elongation factor b; YY1, Ying Yang 1.

FIG. 3.

Initiation of HIV-1 transcription at the 5′ LTR. After stimulation of CD4+ T cells, HIV-1 transcription can be initiated owing to recruitment of active of NF-κB (p50/RelA) and active NFAT to the κB sites of the 5′ LTR via IKK-mediated IκB proteosomal degradation and calcineurin-mediated dephosporylation, respectively. These host factors induce transcription in part by recruiting HAT, p300/CBP, to acetylate (Ac) histones at the 5′ LTR that increases chromatin accessibility enabling recruitment of RNA Pol II and CD7/TFIIH. Possibly, HDMs are also involved by removing repressive methylation marks (pink rectangles). CD7/TFIIH phosphorylates serine 5 (light grey rectangles) of the CTD tail of RNA Pol II to promote HIV-1 transcription initiation. However, shortly after initiation RNA Pol II pauses and transcription is halted because of inhibitory effects of DSIF and NELF, hypophosphorylation of RNA Pol II, and low availability of P-TEFb (CycT1/CDK9). CBP, CREB-binding protein; CTD, C-terminus domain; DSIF, DRB sensitivity inducing factor; IκB, inhibitor of κB; IKK, κB kinase; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; HDMs, histone methyltransferases; NELF, negative elongation factor.

FIG. 4.

Elongation of HIV-1 transcription at the 5′ LTR. To relieve pausing of RNA pol II at the LTR, the viral transactivator Tat is required owing to its ability to efficiently recruit the P-TEFb complex to the 5′ LTR. First, Tat can outcompete BRD4 for the available active P-TEFb in the nucleus. Second, Tat interacts with the P-TEFb repressive complex 7SK snRNP to allow the release and activation of more P-TEFb. This Tat-mediated increase in availability of active P-TEFb then culminates in increase of P-TEFb recruitment at the 5′ LTR to form the Tat/TAR/P-TEFb complex. The CDK9 component of P-TEFb mediates phosphorylation of serine 2 (ser 2, gold rectangles) of CTD tail of RNA Pol II and phosphorylation of NELF and DSIF. In addition, other host factors are also recruited and form what is called the super elongation complex that augments Pol II processivity, transcriptional efficiency, and prevent its back tracking to promote HIV-1 transcriptional elongation. Furthermore, activities of HATs p300/CBP, hCGN5, PCAF, and HDMs are also important for Tat-mediated HIV-1 transcriptional elongation. TAR, transactivator response element.

In that regard, deacetylation at this site by histone deacetylase transferases (HDACs) leads to repression of viral gene expression, whereas hyperacetylation of this nucleosome mediated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), such as p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP), leads to productive and efficient HIV-1 transcription (Figs. 2 and 3). In line with this concept, HDACs seem to be heavily recruited at the 5′ LTR in both latently infected cell lines and primary CD4+ T cell models of HIV-1 latency. For instance, COUP transcription factor 2 (CTIP2), Ying Yang 1 (YY1), Late SV40 factor (LSF), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) p50/p50, and C-promoter binding factor-1 (CBF-1) are among several host factors that bind their cognate sites at the nucleosome-free region and recruit HDACs to hypoacetylate nuc-1 to favor the maintenance of HIV-1 latency77–82 (Fig. 2).

Histone methylation

Maintenance of HIV-1 latency has also been linked to a second epigenetic modification: the histone methylation at the nuc-1 site. Although the consequences of methylation on general transcriptional activity varies depending on the site (lysine[K] vs. arginine [R]) and the pattern of methylation (mono-, di-, or trimethylation), certain tendencies have been associated with HIV-1 transcription.83

Specifically, di or trimethylation of H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2-3) and trimethylation of H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) have been demonstrated to be enriched at the promoter region of latently infected cells.79,80,84,85 Histone methyltransferases (HMTs), such as euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2 and suppressor of variation 3–9 homolog 1 (SUV39H1), mediate H3K9m2-3, whereas enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) trimethylates H3K27 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, a new methylation site was recently described by Ott's laboratory; monomethylation of H4 lysine 20 (H4K20me) was found to be enriched at the 5′ LTR of latent cells86 (Fig. 2). In addition, depletion or pharmacological targeting of the methyltransferase (SMY2D/L3MBTL1) mediating this reaction led to the reversal of HIV-1 latency.86

Taken together, the intricate balance between histone acetylation and methylation is emerging as critical in regulating the activity status of the 5′ LTR in latent cells. During activation, nuc-1 tends to be acetylated at lysine sites, whereas methylation is impeded (Fig. 3). Conversely, during latency, HDACs are heavily recruited at the silenced 5′ LTR by numerous factors to deacetylate histones. In addition, HMTs are also recruited to mono, di-, or trimethylate-preferred sites, to reinforce the state of latency79 (Fig. 2).

DNA methylation

In addition to epigenetic changes associated with histones, DNA methylation has also been implicated in HIV-1 latency in resting CD4+ T cells. In fact, two separate studies have shown that DNA methylation at two CpG islands flanking the transcriptional start site of 5′ LTR contributes to HIV-1 latency87,88 (Fig. 2). However, a follow-up study showed that not all aviremic patients display heavily methylated 5′ LTR in their reservoir pool.89 In fact, there seems to be a lack of LTR methylation in CD4+ T cells isolated from aviremic patients, although LTR methylation density could correlate with increased time on cART therapy.89,90 In other words, patients with long history of suppressive cART treatment accumulate more methylated CpG overtime.90

Thus, at this time the current evidence for DNA methylation playing a role in HIV-1 latency is not yet conclusive and needs to be further validated. One reason for the difficulty in drawing a definitive conclusion on the effect of DNA methylation is the potential confounding effects of unintegrated viral DNA in analyzing methylation of integrated viral DNA. Therefore, it would be of value if future studies provide information on how methylation affects both viral DNA species and their subsequent respective effects on HIV-1 latency.

Transcription interference

In addition to chromatin regulation, transcriptional interference (TI) is also thought to be an important contributor to maintenance of HIV-1 latency.91 This is principally because of the preference of the provirus to integrate in the introns of actively transcribed genes.92 TI can occur in two different ways that depend on the orientation of the provirus with respect to the host gene it is integrated in.

First, both the HIV-1 genome and the host gene can have the same orientation. In this scenario, an elongating RNA Pol II transcribing the host gene could displace important transcription factors or the preinitiation complex at the 5′ LTR, thereby effectively enforcing promoter silencing. This is referred to as promoter occlusion.93 In contrast, when the provirus is oriented in the opposite direction as the host gene, the opposing elongating RNA Pol II can collide and abrogate viral and/or host transcription.94 Of note, potent activation of the HIV-1 LTR seems to be sufficient to effectively nullify the effects of TI regardless of provirus orientation.93,94

Sequestration of transcriptional factors

Proper HIV-1 transcription and/or reactivation from latency require recruitment of several host factors at the 5′ LTR, such as AP-1, SP1, NFAT, and NF-κB.74 Of note, the active form of NF-κB (p50/RelA) is considered to be crucial for proper HIV-1 transcription particularly for the initiation step (Fig. 3). However, in resting CD4+ T cells p50/RelA is sequestered away from the nucleus because of its tight binding by inhibitor of κB (IκB); furthermore, the inactive form of NF-κB (p50/p50) occupies the κB binding site and represses gene expression in part by recruitment of HDACs78,95 (Fig. 2). This indeed creates a cellular environment conducive to repression of HIV-1 gene expression in latent memory CD4+ T cells. Nonetheless, when cells become activated IκB kinase (IKK) mediates the phosphorylation of IκB that causes degradation and subsequent release of p50/RelA.

This active form of NF-κB translocates into the nucleus and displaces p50/p50 at κB binding site96 (Fig. 3). Next, p50/RelA allows for NF-κB driven transcription through recruitment of HATs, such as p300/CBP, which acetylate nucleosomes at the LTR. Furthermore, p50/RelA promotes kinase-mediated phosphorylation of serine 5 and serine 2 of the C-terminus domain of RNA Pol II by recruiting CDK7/TFHII and CDK9 of positive elongation factor b (P-TEFb) complexes, respectively (Fig. 3). The phosphorylation by CDK7/TFHII contributes to initiation of transcription and Pol II promoter clearance, whereas the phosphorylation by CDK9/P-TEFb aids in transcription elongation although the viral transactivator Tat is more efficient at recruiting the P-TEFb complex at the LTR and dramatically enhances HIV-1 transcriptional elongation97,98 (Fig. 4).

In addition to NF-κB, another key cellular factor for HIV-1 transcription is NFAT. Similar to NF-κB, NFAT is sequestered within the cytoplasm (Fig. 2). When cells become activated, NFAT is dephosphorylated by the action of Ca+2-induced calcineurin phosphatase.99 NFAT can then translocate into the nucleus and can also bind to the κB sites of the LTR to induce active transcription, possibly through recruitment of p300/CBP100–102 (Fig. 3).

Consequently, active HIV-1 gene expression depends on the switch between inactive and active forms of NF-κB or NFAT and their cognate bindings at the κB sites of the LTR. The importance of these host factors in maintaining latency has warranted investigation of multiple drugs targeting the associated pathways in an attempt to cure HIV (see “Mechanisms of HIV-1 Latency” section).

Sequestration of P-TEFb

Another major mechanism for maintaining HIV-1 latency is the low efficiency at which the tripartite Tat/transactivator response element (TAR)/P-TEFb complex forms in resting CD4+ T cells, thereby effectively blocking HIV-1 transcriptional elongation. In latent reservoirs, Tat levels can influence the latency state of a provirus; however, the scarcity of active P-TEFb also accounts for the low to nonexistent HIV-1 gene expression in latent reservoirs.103,104 For instance, in the nucleus the 7SK small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex (7 SK snRNP) (containing hexamethylene bisacetamide inducible 1 [HEXIM], 5′ methylphosphate-capping enzyme [MePCE], La-related protein [LARP7], and 7SK small nuclear RNA) binds to active P-TEFb complex and can successfully prevent its recruitment at the HIV-1 LTR105–107 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, P-TEFb releasing agents have been shown to effectively disrupt this interaction and promote HIV-1 reactivation.104,108

Moreover, resting CD4+ T cells, as well as monocytes and macrophages, have low levels of P-TEFb component, cyclin T1 (cycT1), especially in the context of established HIV-1 latency.109–111 Finally, bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) is a host factor that can recruit P-TEFb to the 5′ LTR and can lead to basal HIV-1 transcriptional elongation.112 However, BRD4 can also recruit P-TEFb to the promoters of other host genes to drive their expression instead in response to diverse stimuli.113 Thus, BRD4 is not an HIV-specific cofactor for HIV-1 transcription and can even decrease the level of active P-TEFb at the LTR and act as a Tat competitor for the local binding of P-TEFb.114

Overall, the P-TEFb complex is an essential elongation factor that is tightly regulated in resting CD4+ T cells and its low abundance makes it a significant contributor to proviral silencing and an important drug target.

Therapeutics Strategies for an HIV-1 Cure

The accumulated knowledge on HIV-1 latency has fostered hope that one day the daunting task of curing HIV-1 will be possible. In fact, the application of this knowledge has led to the cure of one HIV-1-infected patient to date, Mr. Timothy Ray Brown, also known as the “Berlin patient.”

In brief, the strategy involved treating his acute myeloid leukemia by several rounds of radiation and more importantly replacing his bone marrow with donor bone marrow that was defective for the CCR5 receptor in immune cells. This regimen effectively protected this patient from being reinfected and assisted in clearing the virus from his body, likely by eliminating the persistent viral reservoirs.115 Presently, Mr. Brown does not have a detectable level of viremia and is no longer under cART therapy. This success story at least shows in part that HIV-1 can be cured, although a regimen such as in this case is too invasive and expensive to become a standard of care for all HIV-infected patients. Thus, other avenues are being studied especially using small-molecule chemical compounds, which generally falls within two main categories: the “shock and kill” or “block and lock” approaches (Figs. 5A and 6A).

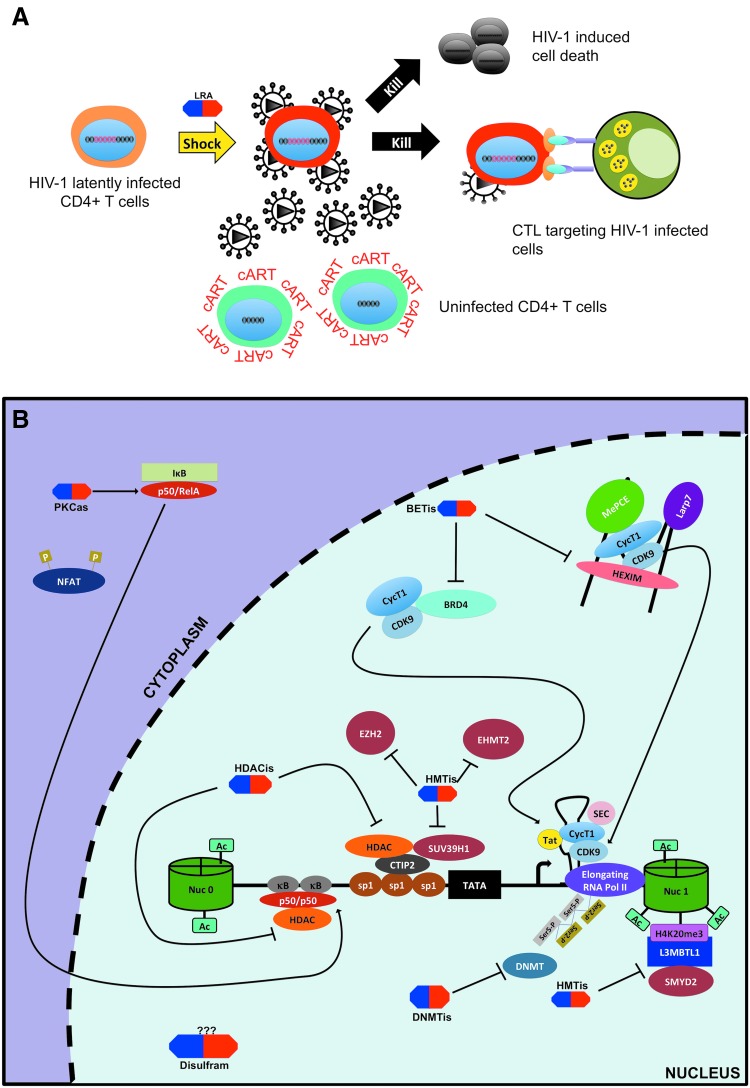

FIG. 5.

Latency-reversing agents of the “shock and kill” approach. (A) The “shock and kill” approach consists of using small compounds known as LRAs (shown above in blue and red) to activate latent provirus in cART-treated patients to facilitate reservoirs clearance by viral cytopathic effects or HIV-specific cytotoxic T cell response in in conjunction with cART to protect uninfected cell from de novo infection. (B) Multiple classes of LRAs have been described: (1) HDAC inhibitors (HDACis) target HDACs to increase histone acetylation at 5′ LTR; (2) HMTis inhibit HMTs and lead to decreased methylation; (3) protein kinase C agonists (PKCas) utilize the PKC pathway to lead to NF-κB-dependent HIV-1 transcription; (4) bromodomain extra-terminal motif inhibitors that block the interaction between BRD4 and P-TEFb or induce P-TEFb release from 7SK snRNP to increase its recruitment at the 5′ LTR. Other LRAs include dilsufram (possibly acting via Akt/IP3 pathway), DNMTis, and cytokines such as IL7, TNFα, IL15 and TLR agonist 3,4 and 7 (not shown). DNMTis, DNMT inhibitors; HMTis, HMT inhibitors; IL, interleukin; LRAs, latency-reversing agents; TNFα, tumor necrosis alpha.

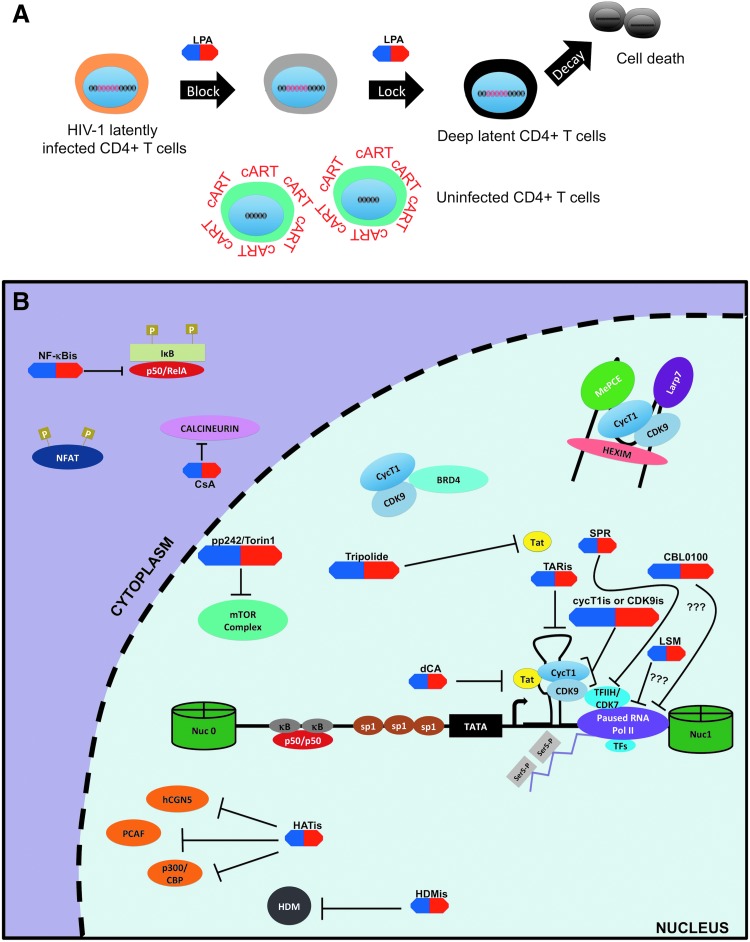

FIG. 6.

Latency-promoting agents of the “block and lock” approach. (A) The “block and lock” strategy aims to permanently silence latent provirus in viral reservoirs using LPAs (shown in blue and red). Specifically, inhibitors of HIV-1 transcription in conjunction with cART would be used to “block” occasional reactivation of HIV-1 proviruses so that integrated proviruses are “lock” in a deep and permanent latency. Such treatment is expected to facilitate the decay of HIV-1 reservoir and lead to a “functional” cure. (B) HIV-1 transcriptional inhibitors can be broadly classified into two groups: inhibitors that target viral components (Tat/TAR) and those that target host factors. For example, both dCA and tripolide fall within the former and target Tat protein. TAR inhibitors (TARis) are also being investigated as potential LPAs. On the contrary, most other HIV-1 transcriptional inhibitors target host factors such as NF-κB (NF-κBis), NFAT (CsA), P-TEFb complex (CycT1 and/or CDK9 inhibitors), mTOR complex (p242, Torin 1), and TFIIH (SPR). Recently, LSM and CBL0100 have also been described as HIV-1 transcription inhibitors. CsA, cyclosporine A; dCA, dehydrocorticostatin; LPAs, latency promoting agents; LSM, levosimendan; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; SPR, spironolactone.

“Shock and kill”

The “shock and kill” is one of the proposed approaches for targeting latent reservoirs in hopes to cure HIV-1. It is based on the concept of purposely inducing reactivation of latent reservoirs in cART-treated patients by using stimulatory agents including but not limited to cytokines and small molecules. Furthermore, in that context the renewed viral gene expression and translation would theoritically lead to the death of reactivated cells through viral cytopathic effects and/or the recognition and clearance of these reservoirs by the immune system for complete eradication of the HIV-1 viruses. This approach is also referred to as “sterilizing” cure.32 This would be carried out in association with cART to protect uninfected cells from infection through newly produced virus (Fig. 5A).

Earlier studies dating back in the late 1990s were among the first to attempt such a strategy by using interleukin 2 (IL2) treatment in combination with cART +/− anti-CD3 antibody to eradicate latently infected cells.116,117 Although viral reservoirs were reduced using this approach, in the end severe drug toxicity was observed especially in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody.117 These initial attempts used biomolecules causing global T cell activation, which can lead to a cytokine storm and cause severe side effects to patients.117 Consequently, if the “shock and kill” was to become a successful approach, efforts had to be made to specifically target HIV-1 reactivation without causing major global T cell activation. Based on that premise, development and testing of such chemical compounds, commonly termed latency-reversing agent (LRAs), became a great focus of HIV-1 cure research. The most promising LRA classes are discussed hereunder and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary Table of Different Latency-Reversing Agents

| Compound/class of compounds | Mechanism of action | Latency models tested in | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDACis (e.g., vornistat, romidepsin, panobinostat) |

Inhibit HDACs | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells, clinical trials |

NCT01933594, NCT01319383, NCT02092116, NCT01680094, NCT0136506576,118–121 |

| HMTis (e.g., BIX-01294, GSK-343, AZ391) | Inhibit HMTs | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells |

85,86,126 |

| DNMTis (e.g., 5-aza-CdR) | Inhibit DNMTs | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells |

87,88,127 |

| PKCas (e.g., prostratin, bryostratin-1, ingenol-B) | Promote NF-κB-mediated transcription of HIV-1, increase active P-TEFb levels and its release form 7SKsnRNP | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells, SIV-macaque model |

104,128–136 |

| BETis (e.g., JQ1, I-BET, UMB136) | Block the interaction of BRD4 with P-TEFb and release active P-TEFb from 7SKsnRNP, other mechanism proposed as well |

Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells |

137–141 |

| Disulfram | Unclear but may involve the Akt/PTEN pathway |

Primary models, patient-derived cells, clinical trials | NCT01286259132,142–144 |

| HMBA | Promotes recruitement of active P-TEFb at 5′ LTR |

Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells |

108,136 |

| Benzotriazoles | Block the proper turnover of STAT5 |

Primary models, patient-derived cells | 145 |

BETis, bromodomain extra-terminal motif inhibitors; DNMTis, DNA methylation inhibitors; HDACis, histone deacetylase transferase inhibitors; HMBA, hexamethylbisacetamide; HMTis, histone methyltransferase inhibitors; NCT, national clinical trial; PKCas, protein kinase C agonists; SIV, simian immunodeficiency virus.

Histone deacetylase inhibitors

An extensively studied group of LRAs is the histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) (Fig. 5B). As mentioned earlier, acetylation status of nucleosomes at the LTR heavily impacts the latency state of viral reservoirs. In fact, Van Lint et al. were the first group to show that hyperacetylation of histones at 5′ LTR region as a result of inhibition of HDACs leads to active transcription and reactivation in several HIV-1 latency cell lines.76 Further work by Lehrman et al. demonstrated that addition of an HDACi, valproic acid (VPA), to an intensified cART regimen led to a significant increase in clearance of latently infected cells in three of four patients.118

Unfortunately, follow-up studies did not support the effectiveness of VPA at reducing the latent reservoirs.119–121 More recently, other HDACis, such as vornistat, romidepsin, or panobinostat, have been investigated in clinical trials for their ability to clear latent reservoirs.122–125 Results indicated that these new HDACis are able to induce and maintain the sustained reversal of HIV-1 transcription in aviremic patients. Nonetheless, they still fail to reduce the total pool of HIV-1 latent reservoirs.

Histone and DNA methylation inhibitors

Methylation of histones at the LTR region is considered a target for the “shock and kill” approach as well (Fig. 5B). Three methylation sites have been shown to be associated with latency so far: H3K9me2-3, H3K27me3, and H420me. HMT inhibitors (HMTis) targeting these sites, BIX-01294, GSK-343/EPZ-6438 and AZ391 inhibit the respective enzymes mediating these reactions (SUV39H, EZH2 and SMYD2), and have been tested in several latency models of HIV-1 and in resting CD4+ T cells isolated from cART-treated aviremic patients.85,86,126 However, none of these LRAs have been further evaluated in clinical trials for HIV-1 eradication perhaps because of safety concerns.126

On the other hand, DNA methylation inhibitors (DNMTis), such as 5′-aza-2′ deoxycytidine (aza-CdR), have also shown the capacity to induce HIV-1 viral gene expression in cell line models. However, only limited reactivation was observed when DNMTis were used in aviremic patient derived cells.87,88,127 Consequently, their further application for the “shock and kill” remains to be further evaluated, considering that the role of DNA methylation in HIV-1 latency is still debated.

Protein kinase C agonists

Another class of well-studied LRA is the protein kinase C agonists (PKCas), such as bryostatin-1, prostratin, or ingenol-B.104,128–130 These compounds promote translocation of active NF-κB into the nucleus to induce HIV-1 transcription, thereby reversing the latent state (Fig. 5B). For instance, Williams et al. showed that after treatment with the prototypical PKCa, prostratin, NF-κB is translocated into the nucleus, and occupies its binding site on the 5′ LTR of Jurkat-derived T cell latency cell lines to induce HIV-1 reactivation.128 In addition, certain PKCas (ingenol B and bryostratin-1) may also help facilitate production P-TEFb and its release of from the inhibitory complex 7SKsnRNP.104,130,131

Studies in several primary CD4+ T cell models of HIV-1 latency and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-macaque model have corroborated the potential of certain PKCas as potent LRAs, such as bryostratin-1.132,133 Moreover, these LRAs could supplement cART in the context of the “shock and kill” approach to protect uninfected cells—as they also inhibit acute viral replication through the downregulation of the CD4 receptor.129,134 Interestingly, PKCas also synergize with other classes of LRAs, such as HDACis (romidepsin), to induce potent reactivation of latent HIV-1.104,135 However, PKCa alone only negligibly reactivates HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells isolated from cART-suppressed aviremic patients.104,135,136 This suggests that combination of LRAs would be more beneficial for the “shock and kill” approach.

Bromodomain extra-terminal motif inhibitors

P-TEFb is an essential host factor for proper HIV-1 elongation and reactivation. Unsurprisingly, compounds that increase the availability of active P-TEFb at the HIV-1 promoter are investigated as LRAs, including the relatively newer ones—the bromodomain extra-terminal motif inhibitors (BETis) (e.g., JQ1, I-BET, I-BET 151, and UMB136). Their mechanism of action lies in their ability to block the interaction of cellular host BRD4 with P-TEFb and enhance the release of P-TEFb from the 7SKsnRNP inhibitory complex, although other mechanisms have also been proposed137–141 (Fig. 5B). Consequently, Tat can efficiently recruit P-TEFb and the associated super elongation complex to the HIV-1 promoter and induce reactivation (Fig. 5).

A few recent studies showed that use of PKCa with BETi in pair is among the most efficacious LRA combinations to reactivate latent HIV-1 in PBMCs or resting CD4+ T cells isolated from cART-suppressed aviremic patients.135,141 Nonetheless, this combinatorial effect needs to be further evaluated in clinical trials.

Other LRAs

In addition to the previously well-defined classes of LRAs, other agents are also capable of reactivating latent proviruses. For example, disulfiram, a drug used to treat alcohol dependence was found to moderately reactivate HIV-1 from latency in vitro and in a clinical trial possibly acting through the Akt/PTEN signaling pathway.142–144 Hexamethylbisacetamide is another compound described by Choudhary et al., which caused HIV-1 reactivation through recruitment of active P-TEFb at the 5′ LTR in an Sp1-dependent manner.108

Recently, Bosque et al. have identified a novel target for the “shock and kill” approach. Specifically, the study showed that benzotriazole derivatives, which are small-molecule compounds preventing the sumolyation of phosphorylated STAT5, were able to induce HIV-1 reactivation in a primary CD4+ T cell model and in cells isolated from aviremic patients.145 This suggests that STAT5 pathway is a suitable future target for developing new LRAs. Finally, certain cytokines [e.g., IL7, IL15, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)] and TLR agonists are also being investigated clinically as potential LRAs.146–148

“Shock and kill” roadblocks

Despite being a promising and appealing cure approach, the “shock and kill” still faces several roadblocks. First, it has become increasingly evident that elimination of HIV-1 reservoirs through LRA-mediated reactivation alone may not be sufficient. In fact, Siliciano's group showed in a primary CD4+ T cell model of HIV-1 latency that viral reservoirs in T cells do not die from viral cytopathic effects or cell killing through the cytotoxic CD8+ T cell (CTL) response.149 Furthermore, these observations were corroborated in clinical trials where no single LRA showed the ability to substantially decrease the latent reservoirs.123,146

One strategy to remediate this is the development of immunotherapy to optimize the recognition and killing of reservoir cells. It includes the use of therapeutic vaccines to enhance HIV-1-specific CTL response,150–152 the broadly neutralizing antibodies,153 the dual-affinity retargeting antibodies that not only bind to HIV-1 viral envelop antigen but also activate the CTL response,154 and immune modulators, such as anti-PD1 or anti-CTL4 antibodies, to relieve the immune dysfunction and exhaustion found in cART-treated patients due to chronic inflammation.155 Combinations of LRAs with such immune-based approach are being investigated clinically to evaluate their curative potential.146

Alternatively, it has also been proposed that sensitizing of viral reservoirs toward the apoptosis pathway could help promote cell death of HIV-infected cells after reactivation.156 For instance, Cummins et al. demonstrated that chemical antagonism of antiapoptotic host factor Bcl2 of resting CD4+ T cell isolated from cART-treated aviremic patients leads to the reduction in the number of latently infected cells ex vivo.157 However, this relatively new concept of “prime, shock, and kill” is at its infancy, and targeting the apoptotic pathways might prove to be too toxic for patients in the clinic setting.

Another major concern for the “shock and kill” is the inability of LRAs to effectively reactivate all replication-competent proviruses in patients. Indeed, Ho et al. demonstrated that not all replication-competent proviruses are reactivated despite maximal stimulation of resting T cells isolated from patients.35 Even sequential stimulations were unable to reactivate all intact replication-competent proviruses either, underlying the limitation of the “shock and kill” approach. This is especially concerning as even the most effective LRAs or LRA combinations do not surpass the HIV-1 reactivation potency of global T cell stimulators, such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and anti-CD3/CD8 antibodies.35,104 These studies imply that even given in combination or in sequence LRAs may fail to eradicate viral reservoirs in the clinical setting.

In addition, Darcis et al. proposed that HIV-1 latency is a dynamic process where the involved molecular mechanisms may change over time and negate the effects of previously effective LRAs,32 thus further complicating the potential success of the “shock and kill” approach. Finally, caution should be taken in designing combination of LRAs for therapeutic application. Recent work by Walker-Sperling et al. showed that use of certain LRA combinations can result in undesired side effects. For example, they found that the combination of romidepsin (HDACi) and bryostatin-1 (PKCa) impairs the ability of HIV-1-specific CTL to recognize and kill HIV-reactivated cells.158 This undoubtedly adds another layer of complexity to the “shock and kill” approach.

“Block and lock”

Given the obstacles that the “shock and kill” approach is facing, attention is being given to an alternative approach called “block and lock.” In sharp contrast to the “shock and kill” approach, the “block and lock” approach is based on using latency-promoting agents (LPAs) targeting HIV-1 transcription to create a deep state (i.e., irreversible state) of latency in the viral reservoirs thereby preventing them from reactivation and thus potentially preventing replenishment of the latent pool32 (Fig. 6A). Ideally, for this strategy to work these agents would need to accomplish three principal tasks.

First, LPAs would need to target residual viral transcription still existing in cART-treated aviremic patients to enforce viral latency.68 Second, their anti-HIV-1 effects would need to be efficient at suppressing the events of viral reactivation such as “blips.”32 Finally, they would need to suppress low-level ongoing viral replication especially at the sites or tissues where cART penetrance is low such as the gut and lymphoid tissues.19,159 The last two would be crucial as these mechanisms are thought to be involved in the reseeding and maintenance of the HIV-1 latent reservoirs.33

Ultimately, the desired outcome of this strategy is a “functional” cure that could be achieved through the speculated accelerated decay rate of viral reservoirs as reservoir replenishment and reactivation would be effectively abrogated.160 Specifically, a “functional” cure is defined as the condition in which despite the presence of HIV-1 proviral genomes a patient is able to cease all antiretroviral therapies with no viral rebound, decline of CD4+ T cells count, or progression toward AIDS. In addition, such a patient should also exhibit enhanced immune function and no risk for HIV-1 transmission.161 However, to establish this deep state of latency in reservoirs, inhibitors specifically targeting HIV-1 transcription are necessary. Consequently, we will explore the current state of HIV-1 transcriptional inhibitors and examine their potential as LPAs hereunder (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Potential Latency-Promoting Agents

| Compound/class of compounds | Mechanism of action | Latency models tested in | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TARis (e.g., WMN5, HM13) | Interfere with proper Tat/TAR interaction by binding to TAR RNA | Cell lines, HIV-1 mouse model | 162,163 |

| dCA | Interferes with proper Tat/TAR interaction by binding to TAR-binding domain of Tat, epigenetically repress the 5′ LTR, inhibits Tat-mediated neurotoxicity | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells, HIV-1 mouse model | 161,175–177 |

| Trilopide | Promotes proteasomal degradation of Tat | No formal testing in latency models, show suppression of Tat-mediated LTR activity in nonlatent cells, inhibits acute HIV-1 replication, clinical trial ongoing to assess aptitude to decrease reservoirs size in treatment-naive HIV-positive patients | NCT02219672174 |

| CDK9is (e.g., CR8#13, F07#13, IM) | Inhibit CDK9 kinase activity, disrupts proper Tat/CDK9 interaction | Limited evidence in cell lines, inhibition of acute HIV-1 replication in PBMCs and in an HIV-1 mouse model | 180–182 |

| CycT1is (e.g., C3) | Disrupt proper Tat/cyclinT1 interaction | Limited evidence in cell lines only | 183 |

| HATis (e.g., curcumin, LTK14) | Inhibit HAT | No evidence in latency models, some evidence for inhibition of acute HIV-1 replication in vitro | 184,186 |

| HDMis (e.g., LSD1) | Inhibit HDMs | Cell lines, primary models | 188 |

| NFATis (e.g., CsA, FK506) | Inhibit NFAT-mediated HIV-1 transcription | No evidence in latency models, some evidence of inhibition of acute HIV-1 replication in vitro | 101,189–191 |

| NF-κBis (e.g., IKK inhibitors, 17-AAG, AUY922, GV1001) | Inhibit different steps of NF-κB pathway to suppress HIV-1 transcription, indirect inhibition of NF-κB through targeting of HSP90 chaperone | Limited evidence in cell lines only | 195–198 |

| mTORis (e.g., pp242, Torin1) | Inhibit mTOR signaling | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells | 199 |

| Spironolactone | Possibly through degradation of XPB component of TIIFH negatively affecting Tat-mediated LTR transcription | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells | 203,204 |

| Levosimendan | Possibly involving the Akt/PIK3 pathway but mechanism is still under investigation | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells | 204 |

| CBL0100 | Potentially suppress HIV-1 elongation but mechanism is still under investigation | Cell lines, primary models, patient-derived cells | 208 |

CBL0100, curaxin 100; CDK9is, CDK9 inhibitors; CsA, cyclosporine A; CycT1is, Cyclin T1 inhibitors; dCA, dehydrocorticostatin; HATis, HAT inhibitors; HDMis, histone demethylase inhibitors; IM, indirubin-3′-monoxime; LSD1, lysine-specific demethylase 1; mTORis, mTOR inhibitors; NFATis, NFAT inhibitors; NF-κBis, NF-κB inhibitors; TARis, TAR inhibitors; XPB, xeroderma pigmentosum group B.

Targeting Tat/transactivator response element

The efficiency of HIV-1 transcription significantly depends on the proper formation and interaction of the Tat/TAR/P-TEFb complex. Unsurprisingly, the quest of finding suitable and effective LPAs has focused on disrupting these interactions.

TAR inhibitors

TAR is a stem-loop RNA structure formed at the beginning of all HIV-1 viral transcripts. It acts principally as a docking site for Tat through a bulge substructure. This interaction is mediated in part by the arginine-rich motif (ARM) of the Tat protein allowing for favorable binding to the negatively charged TAR RNA.107 Thus, the interface of this interaction has been the predominant target for developing transcription inhibitors and/or LPAs (Fig. 6B). For instance, WMN5 is a quinolone-based compound that specifically binds to the bulge of TAR and effectively disrupts Tat/TAR association and suppresses Tat-mediated LTR transcription.142

Follow-up studies have focused on improving this lead compound. However, although many of the generated quinolone derivatives, such as HM13, were shown to inhibit HIV-1 transcriptional activity in latency cell lines and in one in vivo mouse model, they have not been evaluated ex vivo using HIV-1 latent reservoirs isolated from cART-treated aviremic patients.163–166 Additionally, the solubility and toxicity of these compounds also need to be improved.161 Other potential reagents targeting TAR RNA are actively being investigated through screening-based methods and further validation of promising hits is ongoing.167,168 In addition, the crystal structure of tripartite Tat/TAR/P-TEFb complex of equine infectious anemia virus can give further insights for other targetable sites of TAR.169

Tat inhibitors

The viral transactivator Tat is another important component of the Tat/TAR/P-TEFb complex. Furthermore, Tat is thought to have neurotoxic properties and a contributor to HAND in cART patients probably because of its ability to induce release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines after crossing the blood–brain barrier.170 Therefore, a safe, potent, and specific Tat inhibitor (Tati) would possibly have a two-fold effect for HIV-infected individuals. First, such compound would severely impair HIV-1 transcriptional elongation, thereby favoring the deep latent state of HIV-1 proviruses. Second, Tatis could also help alleviate neuroinflammation and concomitantly improve cognition skills in cART-treated aviremic patients.

To date, only one Tati, dehydrocorticostatin (dCA), has elicited the promise in fulfilling both criteria compared with the other proposed Tatis160,171–174 (Fig. 6B). Indeed, Mousseau et al. showed that dCA binds to the ARM of Tat to abrogate Tat-TAR interaction.175 Use of dCA leads to not only the inhibition of viral replication in HIV-1 acutely infected cells but also the suppression of viral transcription in HIV-1 chronically and latently infected cells.160,175 Moreover, in the studies using an ex vivo resting CD4+ T cell model of HIV-1 latency, dCA in combination with cART was able to suppress viral load in three of five subjects to <1 copy/mL at 25 days after drug removal.176 In contrast, viral production after drug removal resumed in the cells pretreated with only cART in all subjects.

Further investigation showed that dCA might also epigenetically modulate the nuc-1 at the 5′ LTR to further silence HIV-1 transcription.176 In addition, dCA was shown to reverse the release of inflammatory cytokines such TNFα or IL1β in vitro in an astrocyte cell line and reduce Tat-mediated addictive behaviors in a Tat transgenic mouse model.177 Thus, dCA is an attractive compound for clinical investigation in the context of the “block and lock” strategy.

Nonetheless, it is noteworthy to mention that in vivo testing of cART combined with dCA in a humanized mouse model only delayed viral rebound by one additional week compared with cART after treatment interruption. Thus, although dCA in combination with cART can provide added benefit, it seems that simply adding dCA to cART would not lead to the desired “functional” cure. Therefore, development of other LPAs is still warranted. In that regard, triptolide, a compound isolated from the Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii, was found to reduce HIV-1 replication at the transcriptional level by causing proteosome-mediated Tat degradation.174 This compound is already in a clinical trial to assess its potential beneficial effect in conjunction with cART at reducing latent reservoirs establishment in acutely infected treatment naive patients (NCT02219672).

Targeting P-TEFb complex

P-TEFb is an important component of the tripartite complex because it efficiently induces HIV-1 transcriptional elongation. Therefore, P-TEFb is also a potential candidate for LPA development. Moreover, because it is a host cellular factor, viral escape mutants are less likely to arise compared with viral proteins such as Tat. However, caution needs to be taken in the design of such reagents as P-TEFb is also involved in the transcription of host genes, and the P-TEFb inhibitors lacking specificity to target HIV-1 transcription may lead to undesired toxicity.

CDK9 inhibitors

Inhibiting CDK9 activity solely for HIV-1 transcription is a difficult task. However, novel derivatives of earlier generation of CDK9 inhibitors, particularly those targeting CDK9's adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding site, such as roscovitine or flavoripol, were modified to be more specific for CDK9 activity, especially for inhibition of HIV-1 transcription161 (Fig. 6). For example, CR8#13 is a third-generation CDK9 nucleoside analogue that inhibits Tat-mediated transcription. It also has improved toxicity profile, inhibits acute HIV-1 replication in PBMCs, and suppresses HIV-1 reactivation from one latent T cell line with better overall efficacy as compared with the older compounds (roscovitine or flavoripol).178

Moreover, recently Németh et al. have generated novel series of ATP nucleoside analogues that have even greater specificity for CDK9 with low toxicity profile.179 However, follow-up studies in ex vivo and in vivo models are needed to truly classify these agents as LPAs. This is warranted as these compounds are targeting enzymatic activities without permanent blockade of the provirus into a deep latency ; therefore, one can imagine that treatment removal may not have long lasting inhibitory effects.

It is noteworthy to mention that two other CDK9 inhibitors, indirubin-3′-monoxime (IM) and F07#13, were shown to suppress acute viral replication in HIV-infected humanized mouse models.180,181 Interestingly, IM is a derivative of the Chinese antileukemia compound, Indirubin, that was found to suppress viral replication of HIV-1 drug-resistant strains both in PBMCs and in humanized mouse model.180,182 Moreover, limited testing in the U1/HIV-1 latency cell line suggests a potential for blocking HIV-1 reactivation.

In addition, F07#13 was discovered by the Kashanchi's Lab, based on high-throughput screening of small molecules mimicking Tat peptides to abrogate the interaction between cyclins and CDKs. Similar to IM, this compound was tested in one latency cell line, acutely infected PBMCs, and humanized mouse model.181 These compounds are effective to control viral load and inhibit HIV-1 transcription. Thus, further evaluation of these compounds in ex vivo or in vivo models of HIV-1 latency should be considered to further evaluate them as LPA.

Cyclin T1 inhibitors

cycT1 is the other component of P-TEFb that could be targeted to inhibit HIV-1 transcription161 (Fig. 6B). One of the promising compounds of this class was discovered by in silico screening of small molecules that bind to the cycT1/Tat/TAR interaction interface. After optimization, the C3 compound was demonstrated to prevent the binding of Tat to cycT1 and specifically inhibited Tat-mediated transcription. In addition, use of C3 compound leads to both suppression of acute viral replication and HIV-1 reactivation from latency cell lines with minimal cytoxicity.183 This compound is certainly another promising LPA in need of further characterization both in the ex vivo or in vivo models of HIV-1 latency.

Targeting other host factors

In addition to P-TEFb, HIV-1 transcription depends on other important host cellular factors. Among them, HATs, histone demethylases (HDMs), NFAT, and NF-κB were shown to be viable targets to inhibit HIV-1 transcription (Fig. 5B).

HAT inhibitors and HDM inhibitors

In addition to histone modifications for proper control of HIV-1 transcription, HATs can also modulate key transcription factors, such as NF-κB, and the viral transactivator Tat to promote HIV-1 transcription. For instance, both NF-κB and Tat transcriptional activities are greatly enhanced because of their acetylation by p300/CBP74,184 (Figs. 3 and 4). Thus, p300/CBP HAT inhibitors (HATis) could be considered for blocking HIV-1 transcription (Fig. 7B). A few of these compounds, specifically curcumin or garcinol-derivative LTK14, were shown to suppress HIV-1 replication, however their toxicity may hinder their future application as LPAs.185,186 Similarly, two other potential targetable HATs are p300/CBP-associated factors (PCAFs) and histone acetyl transferases (hGCN5), as both are important for proper Tat functions. However, HATis targeting these two factors would potentially face toxicity issue similar to p300/CBP inhibitors.187

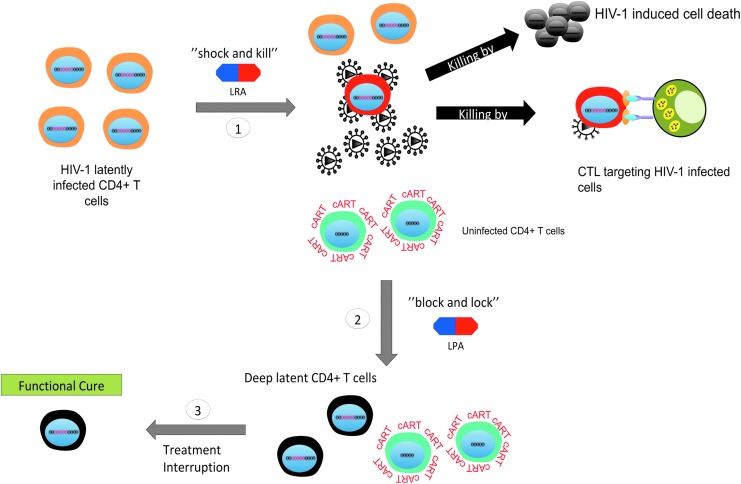

FIG. 7.

Schematic of the proposed “two-step” approach. Given the diversity of mechanisms that control HIV-1 latency and the probable variable response in the efficacy of LPAs or LRA in different patients, perhaps a better strategy for a cure would be to combine both the “shock and kill” and “block and lock” strategy: (1) theoretically, the “shock and kill” could be used first to eliminate the more inducible latent reservoirs; (2) next, the “block and lock” strategy could follow to permanently silence the remaining reservoirs and further reduce the reservoir size; (3) finally, following the sequential application of these combined therapies, a functional cure could potentially be achieved after treatment interruption.

Finally, histone demethylase inhibitors (HDMis) could also be considered to inhibit HIV-1 transcription as HDMs typically act in concert with HATs to promote gene expression including HIV-183 (Fig. 3). For example, the lysine-specific demethylase 1 can methylate Tat protein to promote HIV-1 transcriptional elongation, and inhibition of this HDM using monoamine oxidase inhibitors has led to suppression of HIV-1 reactivation in the J-LAT A2 cells as well as a primary CD4+ T cell model of latency.188 However, there were no follow-up studies of these compounds in term of their effects in aviremic patient samples, possibly because of the limited specificity of these inhibitors.

Overall, HATis and HDMis specific to inhibit HIV-1 transcription may provide other avenues for LPA development. Nevertheless, caution must be taken as these types of compounds usually are notably toxic and lack of specificity.

NFAT inhibitors

Cyclosporine A (CsA) and FK506 are two immunosuppressive agents that function via NFAT inhibition but also were shown to have anti-HIV activity since the early 1990s.189 In fact, both drugs inhibited NFAT-mediated LTR-driven HIV-1 transcription in primary CD4+ T cells probably through blocking NFAT translocation into the nucleus101 (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, CsA may also suppress HIV-1 replication and infectivity through other mechanisms unrelated to its NFAT inhibition.190 However, in clinical trials CsA was used in conjunction with cART mostly as an immune-modulatory agent to dampen the immune activation during the HIV-1 acute infection rather than to suppress HIV-1 transcription and reactivation in the context of a functional cure.191–194 Furthermore, CsA has displayed low toxicity in humans; therefore, evaluation of its potential as an LPA would be feasible in the clinical setting.

NF-κB inhibitors

Similar to NFAT, NF-κB has been considered as a target for HIV-1 transcriptional inhibition195,196 (Fig. 6B). Victoriano and Okamoto extensively reviewed the NF-κB inhibitors that suppress HIV-1 transcription.196 In brief, the NF-κB inhibitors can be grouped into 5 major categories based on the step(s) of NF-κB activation: (1) IKK inhibitors that prevent phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB; (2) inhibitors of p50/RelA nuclear translocation; (3) competitive binders for the κB DNA-binding site; (4) antioxidant inhibitors that dampen oxidative stress induced by NF-κB; and (5) inhibitors of PKC, the latter being an upstream signaling pathway of NF-κB activation.196

More recently, another class of compounds indirectly targeting the NF-κB pathway has been described as anti-HIV drugs and potential LPAs.197,198 Specifically, HSP90 inhibitors, 17-AAG and AUY922, were found to potently suppress HIV-1 reactivation in J-LAT-A2 cells. Further mechanistic studies unraveled that these compounds abrogated the association of HSP90 to IKK, impeding IKK-mediated degradation of IκB and subsequent translocation of NF-κB into nucleus.197 Similarly, GV1001, a peptide targeting HSP90, also elicited potent inhibition of HIV-1 transcription and suppression of PMA-induced HIV-1 reactivation in vitro in an HSP90-dependent manner. GV1001's antiviral activity was also shown to act through the inhibition of NF-κB-dependent transcription.198

Very likely, these recently described agents could be further evaluated as LPAs for the “block and lock” approach, especially GV001. In fact, GV1001 has already been tested in clinical trials for anticancer therapy and was well tolerated.198 Thus, GV1001 could be investigated clinically as an LPA soon.

Other inhibitors

In addition to the above conventional targets of HIV-1 transcription, efforts have been made to identify novel HIV-1 transcriptional inhibitors from compound screening and/or the updated understanding of HIV-1 latency. These newer candidates of LPAs are discussed hereunder.

Mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitors

Besnard et al. recently conducted a whole-genome short hairpin RNA screen to identify novel cellular proteins that either promote or inhibit the reversal of HIV-1 latency.199 This study identified and validated the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine/threonine kinase involved in cellular growth and metabolism, as a negative regulator of HIV-1 latency. Furthermore, lead mTOR inhibitors (mTORis), pp242 and Torin 1, were evaluated for their ability to suppress HIV-1 reactivation in several models of HIV-1 latency including ex vivo resting CD4+ T cells isolated from aviremic patients. Both pp242 and Torin 1 significantly repress HIV-1 reactivation in all tested latency models, which likely act through both Tat-dependent and Tat-independent blockade of HIV-1 transcription199 (Fig. 6B).

Consequently, these compounds could potentially help to control both basal and Tat-mediated transcription in cART-treated patients. However, caution must be taken with the inhibition of the mTOR pathway as it is at the center of many important biological processes, including protein synthesis, autophagy, and cell proliferation and survival.200,201

Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs: spironolactone and levosimendan

Spironolactone (SPR) is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug used in the clinic principally as an antagonist of the minerocorticoid hormone aldosterone for the treatment of many different ailments, including fluid retention, hypertension, heart failure, and hyperaldosteronism.202 Recently, it has also been shown that SPR inhibits acute HIV-1 infection in Jurkat and primary CD4+ T cells independent of its anti-aldosterone effects but likely through the degradation of xeroderma pigmentosum group B, the helicase component of the TFIIH transcription complex.203 Unexpectedly, SPR targets Tat-mediated transcription rather than basal LTR transcription. However, no evaluation was made for its potential to block HIV-1 reactivation in this study.

Interestingly, the studies in our laboratory, aiming to identify novel LPAs through the screening of FDA-approved compounds, confirmed that SPR is capable of blocking HIV-1 reactivation in CD4+ T cells isolated from cART-treated aviremic patients, although with moderate cytotoxicity204 (Fig. 6B). Our screening also identified levosimendan (LSM), an inotropic calcium sensitizer, as another potential HIV-1 transcriptional inhibitor that suppresses HIV-1 reactivation ex vivo (Fig. 6B). Clinically, LSM is used for the treatment of acutely decompensated heart failure and has several proposed mechanisms of actions, such as increase of calcium sensitivity, inhibition of phosphodiesterase, or activation of AKT/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PIK3) pathway.205–207

We did observe that PI3K inhibitors could overcome LSM's suppressive activity and restore HIV-1 transcription in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that the Akt/PIK3 pathway is likely involved.204 However, the specific mechanism for LSM mediated inhibition of HIV-1 transcription and reactivation still needs to be further elucidated. Overall, both SPR and LSM are capable of potently blocking HIV-1 reactivation and inhibiting acute HIV-1 replication. As they are both FDA-approved drugs, further evaluation of their antiretroviral activities in the clinical setting shall be considered.

Curaxin CBL0100

Finally, we have also recently described another potential novel LPA, curaxin 100 (CBL0100)208 (Fig. 6B). This compound belongs to a class of antitumor drugs, known as curaxins, which were identified from the structure-activity relationship screening of the 9-aminocridine derivatives, quinacrine (antimalarial drug) and carbazole-like molecules.209,210 Specifically, curaxins bind to chromatin DNA and causes trapping of the FACT complex onto chromatin (also known as “c-trapping”), which in turn results in an increase of p53 activity and concomitant decrease of NF-κB-mediated transcription.209,211 The FACT complex acts as an ATP-independent chromatin remodeler and is involved in productive RNA Pol II-mediated elongation. FACT can disassemble and reassemble nucleosomes to allow the passage of RNA Pol II and maintain the integrity of genome.72

Interestingly, FACT has also been recently described as a host factor involved in both HIV-1 integration and HIV-1 latency.212–214 In our recent study, we found that CBL0100 inhibits HIV-1 transcription, independent of the NF-κB site at the HIV-1 promoter, and causes the derecruitment of RNA Pol II and FACT at the LTR region208 (Fig. 6B). CBL0100 also potently blocks HIV-1 reactivation in PBMCs isolated from cART-treated aviremic patients with minimal cytotoxicity. CBL0137, another member of the curaxin class, is currently being evaluated as an anticancer drug in the clinical investigation.215 Thus, studies of curaxins as anti-HIV therapeutics can be explored in the clinical setting in the future as well.

Perspective