Abstract

Background

Whether enhanced prehospital volume therapy leads to outcome improvements in severely injured patients with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains controversial. The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of prehospital volume therapy on the clinical course of severely injured patients with severe TBI.

Methods

Data for 122,672 patients from TraumaRegister DGU® (TR-DGU) was analyzed. Inclusion criteria were defined as follows: Injury Severety Score (ISS) ≥ 16, primary admission, age ≥ 16 years, Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) head ≥3, administration of at least one unit of packed red blood cells (pRBCs), and available volume and blood pressure data. Stratification based on the following matched-pair criteria was performed: group 1: prehospital volumes of 0-1000 ml; group 2: prehospital volumes of ≥1501 ml; AIS head (3, 4, 5 + 6 and higher than for other body regions); age (16-54, 55-69, ≥ 70 years); gender; prehospital intubation (yes/no); emergency treatment time +/− 30 min.; rescue resources (rescue helicopter, emergency ambulance); blood pressure (20-60, 61-90, ≥ 91 mmHg); year of accident (2002-2005, 2006-2009, 2010-2012); AIS thorax, abdomen, and extremities plus pelvis.

Results

A total of 169 patients per group fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Increasing volume administration was associated with reduced coagulation capability and reduced hemoglobin (Hb) levels (prothrombin ratio: group 1: 68%, group 2: 63.7%; p ≤ 0.04; Hb: group 1: 11.2 mg/dl, group 2: 10.2 mg/dl; p ≤ 0.001). It was not possible to show a significant reduction in the mortality rate with increasing volumes (group 1: 45.6, group 2: 45.6; p = 1).

Conclusions

The data presented in this study demonstrates that prehospital volume administration of more than 1500 ml does not improve severely injured patients with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Keywords: Trauma; Prehospital replacement volume; Severe traumatic brain injury; Trauma registry; Hemorrhagic shock, emergency medicine

Background

For severely injured patients, the objective of prehospital volume therapy is to control bleeding and the resulting hemorrhagic shock. In such patients, uncontrollable bleeding following trauma is still considered the most common preventable cause of death [1–4]. The immediate effects of bleeding and shock may result in direct and indirect sequelae in surviving patients. For example, 20% of patients develop multi-organ failure during hospitalization, and 20% experience episodes of sepsis. Multi-organ failure and septic conditions, in addition to thromboembolic complications, increase mortality after severe trauma significantly [5]. Hence, hemorrhagic shock and its consequences represent the second most common cause of death, with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) being the number one cause of death [6]. It is difficult to treat patients with severe TBIs in a prehospital setting. Currently, two therapy options for severe traumatic brain injuries are available: Placing the patient in a 30° semi-recumbent position and providing volume therapy.

The options for prehospital treatment of hemorrhagic shock are limited. In addition to stopping the bleeding, i.e., hemostasis of externally visible bleeding via compression (in accordance with the Advanced Trauma Life Support [ATLS®] guidelines), administering volume therapy is of significant importance [7]. In recent literature, the excessive non-indicated use of volume substitution in patients with severe trauma has been discussed controversially. In the late 1990s, Bickell showed that rapid transfer and modest volume therapy (accepting permissive hypotension) was useful for managing patients with penetrating trauma [8–10]. Restricted volume therapy increasingly appears to be useful for patients with blunt trauma and hemorrhagic shock [11–15]. Several publications from our group have demonstrated that extensive volume therapy is associated with an increase in mortality, even in children [16–19]. These studies showed that the coagulation status of the patients was impaired. The authors concluded that this situation may be attributed to a “dilutive effect” of excessive volume therapy.

The studies mentioned thus far almost exclusively refer to patient populations without severe TBIs. Prehospital therapy of severe TBI and hemorrhagic shock remains controversial. However, it is postulated that enhanced prehospital volume therapy should be administered in patients with severe TBI. The objective of this procedure is to minimize cerebral hypotension due to hypovolemia and subsequent cerebral hypoxia, which is associated with worse outcomes [20, 21]. However, non-indicated prehospital volume therapy leads to dilution coagulopathy [22], which in turn could also lead to worse outcomes due to the persisiting hemorrhage. A retrospective multivariate regression analysis of our working group demonstrated that the prehospital volume must be considered as independent risk factor with regard to mortality, which also applies to patients with concomitant traumatic brain injury, particularly in cases with increasing volume administration. However, this effect was less pronounced compared to patients without concomitant traumatic brain injury [23]. In recent literature, severe prehospital hemorrhage is associated with increased emergency treatment times [16]. This may lead to delayed surgery and poorer outcomes [24].

A search of the current literature raises the question whether the volume and number of substitutions in patients with severe TBI have consequences for hemorrhagic shock during the post-traumatic course. Thus, we hypothesized that enhanced prehospital volume replacement has a positive impact on the outcome of patients with severe TBI and hemorrhagic shock.

Methods

The TraumaRegister DGU® of the German Trauma Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie, DGU) was founded in 1993. The aim of this multi-center database was to provide anonymous and standardized documentation of severely injured patients.

The data is collected prospectively in the following four consecutive time phases from the site of the accident until discharge from the hospital: A) Prehospital phase; B) Emergency room and initial surgery; C) Intensive care unit; and D) Discharge. The documentation includes detailed information on demographics, injury pattern, co-morbidities, pre- and in-hospital management, progression in the intensive care unit, and relevant laboratory findings including data on transfusion and the outcome of each individual patient. The inclusion criterion is hospital admission via the emergency room with subsequent ICU or hospital arrival with vital signs and death before admission to the ICU. The infrastructure for documentation, data management, and data analysis is provided by the Academy for Trauma Surgery (AUC - Akademie der Unfallchirurgie GmbH), a company that is affiliated with the German Trauma Society. The scientific leadership is provided by the Committee on Emergency Medicine, Intensive Care and Trauma Management (Sektion NIS) of the German Trauma Society. The participating hospitals submit their data anonymously into a central database via a web-based application. The scientific data analysis is approved according to a peer review procedure established by Sektion NIS. The participating hospitals (90%) are primarily located in Germany; however, an increasing number of hospitals from other countries (such as Austria, Belgium, China, Finland, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Switzerland, The Netherlands, and the United Arab Emirates) also contribute data. Currently, the data for approximately 25,000 patients from more than 600 hospitals have been entered into the database annually. Participation in the TraumaRegister DGU® is voluntary. For hospitals associated with the TraumaNetzwerk DGU®, however, the entry of at least one basic data set is obligatory for reasons of quality assurance.

The present study is consistent with the publication guidelines of the TraumaRegister DGU® (TR-DGU) and is registered under the TR-DGU project ID M 2013-042.

The following patients are qualified for matching:

Only patients from Germany and Austria were included in this study to minimize variations related to the use of different rescue systems; all of the patients were attended by a physician before hospital admission.

Primary admission to the hospital (no transfers)

Injury Severity Score (ISS) ≥16

Age ≥ 16 years

Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) head ≥3

Infusion of at least one unit of packed red blood cells (pRBCs)

Data available for prehospital administered fluid volume, hemoglobin concentration on hospital admission, and blood pressure at the accident site

and at the time of hospital admission

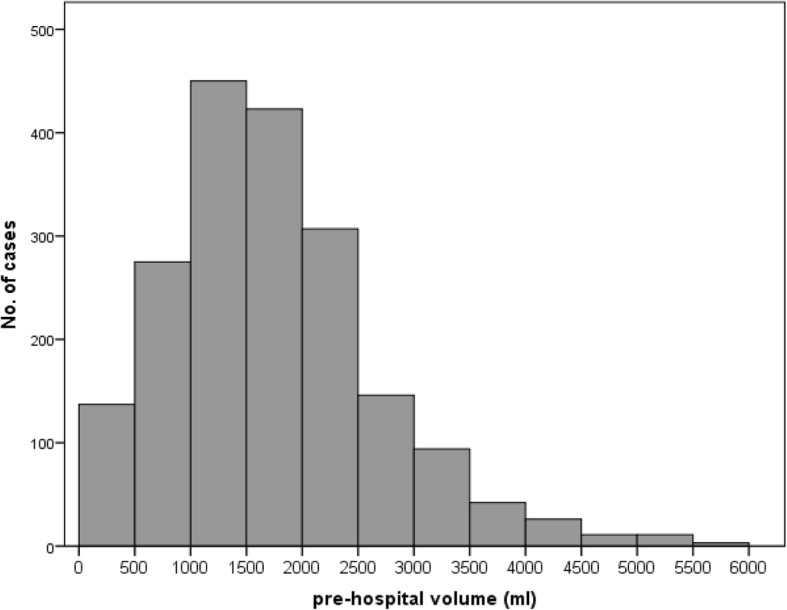

According to the prehospital administered fluid volume (crystalloids plus colloids), patients with severe TBI were divided into a “low-volume” (≤1000 ml) and a “high-volume” (≥1501 ml) group. This classification was chosen according to the mean value of all patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mean value of prehospital volume of all severely injured patients with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). 1352 patients met the inclusion criteria. Based on matching criteria, 169 of these patients in each group underwent further analysis

To evaluate the effect of prehospital volume administration in patients with severe TBI, the patients with high- and low-volume fluid replacement were matched according to the following criteria:

AIS head 3, 4 and 5 inclusive 6

Pattern of injury for the following three body regions: thorax, abdomen, and extremities, including the pelvis, where the matching criteria were AIS severity ≥3 points or < 3 points; the AIS head score had to be greater than that in the other body regions

To account for treatment changes that may have been established over the years, the date of injury was divided into three groups: (1) 2002-2005, (2) 2006-2009, (3) 2010-2012.

Systolic blood pressure at the accident site had to be at least 20 mmHg and was subdivided into three groups with the following values: (1) 20-60 mmHg, (2) 61-90 mmHg and (3) ≥91 mmHg.

Age categories were divided into three subgroups: (1) 16-54 years, (2) 55-69 years and (3) ≥70 years.

Intubation (yes/no)

Method of rescue transport (air vs. ground transport);

Time from injury to hospital ±30 min (differences in the time from injury to hospital admission in matched patients did not exceed 10 min)

Gender (male/female).

By applying very narrow inclusion criteria, it was intended that as many factors as possible influencing the administered volume (e.g. severity of head injury, initially measured blood pressure at the accident site, etc.) should be exactly identical in order to allow the clinical outcome to be investigated with high precision, i.e. in a statistically and clinically relevant manner. The related drastic reduction of the patient sample size was deliberately accepted.

Criteria of the definition of sepsis and single organ failure (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score; SOFA) were described elsewhere [25, 26]. Due to the fact, that the SOFA score is implemented by the TR-DGU® involved hospitals as total value in registry, no conclusions can be drawn to the individually applied treatments and interventions. Criteria of multi-organ failure (MOF) and coagulation status (international normalized ratio; INR) were described in detail previously [17]. The Revised Injury Severity Classification (RISC) [27] was performed to assess the ISS within the groups.

Statistics

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®, version 17, Chicago, IL, USA). Incidences are presented as the number of cases and percentages, and continuous variables are presented as mean values with standard deviations (SD). Differences between the two matched groups were evaluated using the chi-square test in cases of categorical variables and the t-test in cases of continuous variables. In cases of obvious deviations from normality, continuous variables were tested using a non-parametric rank test (Kruskal-Wallis). A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Three hundred thirty eight patients met the inclusion criteria. There were no significant differences between any of the parameters that were used as matching criteria (e.g. AIS head; Table 1), ensuring the applicability of the statistical analysis. Furthermore, the resulting ISS – based on the AIS – did not show any significant differences (low volume, 41.4; high volume, 42.3; p = 0.37). This also applies to the GCS (Glasgow Coma Scale) (low volume, 6.6; high volume, 5.8; p = 0.11). The injury causes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data for severely injured patients with severe TBI treated before hospitalization with low- or high-volume fluid replacement therapy (169 patients per group)

| Patient characteristics | Values for low- and high-volume groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low volume (0-1000 ml) |

High volume (≥1501 ml) |

Group mean (all patients) |

p-values | |

| Patients (n) | 169 | 169 | 338 | |

| Age, years | ||||

| 16-54 (%) | 76.9 | 76.9 | 76.9 | 1 |

| 55-69 (%) | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 1 |

| ≥ 70 (%) | 14.8 | 14.8 | 14.8 | 1 |

| Male (%) | 82.2 | 82.2 | 82.2 | 0.99 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale ≤ 8 (%) | 70.1 | 78.0 | 74.1 | 0.10 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 6.6 ± 4.2 | 5.8 ± 3.8 | 6.2 ± 4.0 | 0.11 |

| Injury Severity Score | 41.4 ± 13.7 | 42.3 ± 13.6 | 41.8 ± 13.6 | 0.37 |

| New Injury Severity Score | 51.1 ± 14.8 | 51.9 ± 14.4 | 51.5 ± 14.6 | 0.64 |

| Blunt trauma (%) | 97.6 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 0.99 |

| Cause of injury: | ||||

| Traffic accident, automobile (%) | 33.1 | 36.8 | 34.9 | 0.16 |

| Traffic accident, motorbike (%) | 13.6 | 15.3 | 14.5 | 0.16 |

| Traffic accident, bicycle (%) | 6.5 | 9.2 | 7.8 | 0.16 |

| Traffic accident, pedestrian (%) | 15.4 | 16.0 | 15.7 | 0.16 |

| Fall ≥ 3 m (%) | 20.1 | 16.0 | 18.1 | 0.16 |

| Fall < 3 m (%) | 7.1 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 0.16 |

| Other accidents (%) | 4.1 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 0.16 |

| Traffic accident (%) | 69.8 | 77.9 | 73.8 | 0.10 |

| AIS head: | ||||

| 3 (%) | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1 |

| 4 (%) | 18.3 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 1 |

| 5 (%) | 71.6 | 71.0 | 71.3 | 0.99 |

| 6 (%) | 8.9 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 0.99 |

| AIS thorax ≥ 2 (%) | 74.0 | 74.0 | 74.0 | 1 |

| AIS abdomen ≥ 2 (%) | 14.8 | 14.8 | 14.8 | 1 |

| AIS extremities, including pelvis ≥ 2 (%) | 72.2 | 72.2 | 72.2 | 1 |

Values are the mean, standard deviation (SD) or % of the group. AIS Abbreviated Injury Scale, TBI Traumatic Brain Injury

Prehospital and emergency department treatment

Due to the study design, significantly less prehospital volume was administered in group 1 compared to group 2 (Table 2). Similarly, a combination of crystalloid and colloidal or hyperoncotic infusions was given more often with increasing prehospital volume. Prehospital blood pressure values did not show significant differences between groups. Even on arrival in the hospital, systolic blood pressures did not show significant differences between groups (Table 2). Moreover, all other vital parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate) did not show significant differences between groups 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Group-specific patient data for fluid administration at the accident site, in the emergency department, and during initial surgical treatment

| Patient characteristics | Values for low- and high-volume groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-volume (0-1000 ml) |

High-volume (≥1501 ml) |

Group mean (all patients) |

p-values | |

| Fluid volume replaced prehospital (ml; MV, SD) | 808 ± 293.5 | 2098 ± 818 | 1453 ± 891 | ≤0.001 |

| Percentage of crystalloid volume replacement solution (ml; MV, SD) |

607 ± 307 | 1370 ± 803 | 991 ± 718 | ≤0.001 |

| Percentage of colloidal volume replacement solution (ml; MV, SD) |

186 ± 263 | 633 ± 477 | 411 ± 446 | ≤0.001 |

| Percentage of hyperoncotic solutions (ml; MV, SD) | 24 ± 92 | 95 ± 231 | 60 ± 180 | ≤0.001 |

| Fluid volume replaced in the emergency department (ml; MV, SD) | 3536 ± 2615 | 3116 ± 2232 | 3321 ± 2445 | 0.12 |

| Total prehospital time (minutes; MV, SD) | 66 ± 22 | 68 ± 21 | 67 ± 22 | 0.35 |

| Emergency room time (minutes; MV, SD) | 64 ± 36 | 72 ± 51 | 68 ± 44 | 0.24 |

| BP at accident site (mmHg; MV, SD) | 121 ± 30 | 116 ± 26 | 118 ± 28 | 0.09 |

| BP at admission to hospital (mm Hg; MV, SD) | 118 ± 34 | 113 ± 29 | 115 ± 312 | 0.22 |

| BP at accident site | ||||

| 20-60 mmHG (%) | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1 |

| 61-90 mmHg (%) | 14.8 | 14.8 | 14.8 | 1 |

| ≥ 91 mmHg (%) | 82.8 | 82.8 | 82.8 | 1 |

| Respiratory rate at the accident site (MV, SD) | 13 ± 5 | 15 | 14 | 0.19 |

| Heart rate at accident site (sec; MV, SD) | 96 ± 25 | 99 ± 24 | 97 | 0.35 |

| Heart rate at admission to hospital (sec; MV, SD) | 93 ± 24 | 95 ± 23 | 94 ± 24 | 0.52 |

| Hb at admission to hospital (g/dl; MV, SD) | 11.2 ± 2.7 | 10.2 ± 2.6 | 10.7 ± 2.7 | ≤0.001 |

| Prothrombin ratio (%) in hospital | 68 ± 25.5 | 63.7 ± 23.3 | 65.8 ± 24.5 | 0.04 |

| INR (MV, SD) | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.01 |

| Platelet count/nl at admission to hospital (MV, SD) | 191,727 ± 77,362 | 177,982 ± 70,564 | 184,681 ± 74,141 | 0.06 |

| Prothrombin time in hospital (sec; MV, SD) | 42.8 ± 33.7 | 47.6 ± 32.5 | 45.2 ± 33.1 | 0.06 |

| Base excess in hospital (mmol/l; MV, SD) | −4.9 ± 6.2 | −4.2 ± 5.6 | −4.5 ± 5.9 | 0.83 |

| Units of pRBCs in hospital (MV, SD) | 5.3 ± 5.2 | 6.1 ± 5.3 | 5.7 ± 5.3 | 0.07 |

| Massive transfusions ≥ 10 units of pRBCs (%) in hospital |

13.6 | 19.5 | 16.6 | 0.1 |

| Units of fresh-frozen plasma in hospital (MV, SD) | 3.4 ± 5.2 | 4.6 ± 6.1 | 3.9 ± 5.7 | ≤0.05 |

| Prehospital use of catecholamines (%) | 12.9 | 20.5 | 16.7 | 0.09 |

| Prehospital chest tube (%) | 4.1 | 9.6 | 6.8 | 0.07 |

| Prehospital CPR (%) | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 1 |

| Prehospital sedation (%) | 89.1 | 93.8 | 91.5 | 0.21 |

| Prehospital intubation (%) | 93.5 | 93.5 | 93.5 | 1 |

| Intubation in hospital (%) | 94.0 | 95.2 | 94.6 | 0.82 |

| Multislice CT (%) | 74 | 72.8 | 73.4 | 0.9 |

Values are the mean, standard deviation (SD) or % of the group. BP blood pressure, Hb hemoglobin, INR International Normalized Ratio, pRBCs packed red blood cells, CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation

All laboratory parameters (hemoglobin concentration, base excess, and coagulation values) were measured throughout the treatment in the emergency department. With the exception of prothrombin time and thrombocyte blood count, all coagulation parameters, and the Hb value were significantly reduced in group 2 (Hb: low volume, 11.2 g/dl; high volume, 10.2 g/dl; p ≤ 0.001, prothrombin ratio: low volume, 68.0%; high volume, 63.7%; p = 0.04, Table 2). There was a tendency, although not significant, of transfusing more pRBCs in the second group (low volume, 5.3 units; high volume, 6.1 units; p = 0.07). Also, the amount of mass transfusions was increased in group 2, but this was neither significant (low volume, 13.6%; high volume, 19.5%; p = 0.1). Furthermore, significantly more fresh-frozen plasma was transfused in group 2 (low volume, 3.4 units; high volume, 4.6 units; p ≤ 0.05, Table 2).

Patients in the second group did receive more prehospital volume therapy as well as prehospital measures, such as chest tube insertion, which was neither significant. The amount of cardiopulmonary resuscitations was not significant (Table 2).

Clinical course and outcome

None of the groups showed significantly higher numbers of emergency surgery (including craniotomy) (low volume, 6.2%; high volume, 6.8%; p = 1, Table 3). There was no difference regarding the length of stay in intensive care units (ICUs) and during the entire hospitalisation, respectively. The same situation was observed with regard to the number of days of intubation in the ICU. There were no significant differences regarding the rates for sepsis, organ failure (including failure of the central nervous system), and multi-organ failure, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical course and outcome of patients with severe TBI receiving low- or high-volume prehospital fluid replacement therapy after trauma

| Patient characteristics | Values for low- and high-volume groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-volume (0-1000 ml) |

High-volume (≥1501 ml) |

Group mean (all patients) |

p-values | |

| Emergency surgery (%) | 6.2 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 1 |

| Days in the intensive care unit (MV, SD) | 16.2 ± 16.3 | 14.5 ± 14.4 | 15.3 ± 15.4 | 0.4 |

| Days intubated (MV, SD) | 11.9 ± 14.4 | 11.4 ± 12.3 | 11.6 ± 13.4 | 0.97 |

| Organ failure (%) | 77.1 | 83.8 | 80.5 | 0.21 |

| Multi-organ failure (%) | 61.1 | 67.7 | 64.4 | 0.3 |

| Sepsis (%) | 13.5 | 9.3 | 11.5 | 0.33 |

| RISC prognosis (MV, SD) | 44.6 ± 30 | 49.8 ± 29.6 | 47.2 ± 30.3 | 0.1 |

| Died in hospital (%) | 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 1 |

| Died within the first 24 h (%) | 23.1 | 24.9 | 24 | 0.8 |

| Days of hospitalization (MV, SD) | 25.1 ± 33.9 | 23.5 ± 31.1 | 24.3 ± 32.5 | 0.46 |

| Glasgow Outcome Scale | ||||

| dead (%) | 46.1 | 47.0 | 46.5 | 0.7 |

| apallic (%) | 9 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 0.7 |

| strongly handicapped (%) | 17.4 | 22.6 | 19.9 | 0.7 |

| mildly handicapped (%) | 17.4 | 12.8 | 15.1 | 0.7 |

| recovered well (%) | 10.2 | 9.8 | 10 | 0.7 |

Values are the mean, standard deviation (SD) or % of the group. RISC Revised Injury Severity Classification, TBI Traumatic Brain Injury

There were no significant differences regarding the mortality probability (based on the RISC prognosis) (low volume: 44.6; high volume: 49.8; p = 0.1, Table 3) and in terms of actual mortality (low volume: 45.6; high volume: 45.6; p = 1) between the two groups. Furthermore, RISC prognosis was based on values that were collected in hospital, including the prothrombin ratio, hemoglobin concentration, and administered pRBCs (27). These values have directly been influenced by the administered prehospital volume.

Moreover, the analysis of the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) did not show any significant differences (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated no positive impact on outcome using enhanced prehospital volume therapy in bleeding patients with severe TBI. Neither mortality nor length of stay (both inhospital and ICU) differed between the two volume groups (low- and high-volume groups).

In these patients enhanced prehospital volume therapy resulted in impaired coagulation and reduced hemoglobin levels. The significantly increased administration of fresh-frozen plasma in this study also confirmed the reduced coagulation capability after enhanced prehospital volume therapy. This relationship has also been supported in studies conducted by Turner and Trunkey as well as by Geeraedts assessing blunt trauma patients without severe TBI [28–32]. The reduced coagulation capability must be rated as critical, particularly in patients after severe TBI, because bleeding is maintained and worse outcomes have been described [33].

The prevention of a second hit following primary trauma events remains the objective of prehospital therapy. As initially mentioned, the primary damage of the central nervous system cannot beimproved. Only preventive measures, such as wearing a helmet during skiing, may have a positive impact in this respect [34]. The administration of prehospital volume therapy in the most severely injured bleeding patients with severe TBI continues to be a treatment option. According to the current literature, abandoning prehospital volume therapy, as concluded by Haut et al., cannot be demanded without reservation [35]. These authors postulated that the routine use of prehospital volume replacement must be avoided because of increased mortality. As a limitation, it must be noted that the emergency system in the study by Haut differs from that in our study. Although the ISS was split into 4 groups, no organ-specific matching (e.g., using the AIS) was performed. Furthermore, the difference in mortality was only 0.3%. The maintenance of cerebral perfusion, even by means of prehospital volume administration, still represents a valid demand [36]. Regarding a complete abandonment of volume administration, valid data is not available. A prospective randomised study would be desirable, but is very difficult to conduct, due the heterogeneity of patients and due to ethical concerns. In our opinion, it would not be acceptable that one group does receive volume therapy for maintaining CPP while another group does not.

Based on our results, the maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure can be achieved with less prehospital volume. Systemic blood pressure values were not significantly different between the two groups, indicating that the enhanced volume administration did not increase cerebral perfusion pressure but resulted in an avoidable reduction of coagulation capability. As demonstrated in previous studies of our working group and in the current literature, a restrained volume administration appears to be sufficient to achieve the blood pressure effects. A similar result was reported by Dutton et al.. These authors demonstrated that the bolus administration of volume may result in receptor-triggered blood pressure elevations [37].

Questioning the volume difference between the two groups is comprehensively discussed by our previous work [17]. In sum, a retrospective statistical analysis is not intended for investigating the physician’s individual decision at the scene. This also applies to prehospital emergency treatment time. When taking into account that delayed definitive treatment in a trauma centre may impact patient outcome significantly (golden hour of shock), the emergency treatment time of more than 60 min seems to be too high [23]. Albeit, the current average in the TraumaRegister DGU® is 65 min [http://www.traumaregister-dgu.de/de/service/downloads.html]. For this reason, emergency treatment time was a matching criterion in order to establish statistical comparability.

The results of our study are supported by the current literature. In a subgroup analysis (with regard to TBI) of a prospective multi-center study, Turner et al. showed that the enhanced volume administration did not lead to positive effects [28]. Tan et al. adapted this result in their review and noted that no large-scale study exists in current literature [36]. However, they concluded that a sufficient volume must be administered to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure. Our study supports this conclusion, particularly the abandonment of volume therapy is not justified based on the current literature.

Another remarkable result of our study is that reduced volume therapy did not lead to a worse outcome in severely injured patients with severe TBI. Neither the mortality rates nor the GOS outcome (Glasgow Outcome Scale) improved in patients with higher volumes. The occurrence of multi-organ failure and organ failure, respectively, tended to differ, although this difference was not significant. Studies conducted by our working group have already demonstrated this effect in severely injured patients without severe TBI.

Interestingly, the RISC score confirmed the influence of fluid volume on mortality because this score was directly influenced by the administered prehospital volume, e.g., using the measurements of the prothrombin ratio, hemoglobin concentration or transfusion of pRCBs.

It must also be noted that some trauma patients may be transferred from other hospitals (which may not be trauma centres) as a secondary measure, i.e. after initial, potentially life-saving interventions. This population was intentionally excluded, because such interventions may influence the outcome and as such the total findings of this analysis. Moreover, the TraumaRegister DGU® does not provide prehospital information on other than primarily admitted patients.

Limitations

As we have described the underlying limitations regarding coagulation analysis, the criteria of matched-pair analysis, and the disadvantage of retrospective analysis previously [17], we would like to add here, that the TR-DGU® only enrolls patients who are admitted alive to the hospital. No statements can be made with regard to patients who died at the accident site or during transport to the hospital. To a certain degree, this criterion represents a type of selection.

The systolic blood pressure measured at the accident site may also be influenced by active bleeding and, thus, cause increased prehospital volume administration. Systolic blood pressure values are usually referring to the initially measured blood pressure at the accident site, prior to interventional measures such as volume administration. In order to minimize that potential bias, we defined very narrow matching criteria in our study design. For example, total injury severity – based on ISS and NISS – has been identical. Even associated injuries have been exactly identical from a statistical point of view (e.g. AIS abdomen, thorax). Despite these strictly defined criteria, it cannot be ruled out that patients suffering from increased bleeding after initial blood pressure measurement were in one group or another. This cannot be conclusively clarified based on anonymised data in a retrospective study, but when considering the size of the population, a certain balance can be expected.

Conclusions

The present study does not support aggressive volume replacement after trauma and bleeding in patients with severe TBI. There were no improvements of outcome or mortality due to increased prehospital volume administration. On the contrary, coagulation was worsened.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to the IFOM Institute and Prof. Rolf Lefering for their outstanding support. The authors also thank the members of the Committee on Emergency Medicine, Intensive Care and Trauma Management of the German Trauma Society (Sektion NIS) for their long-standing and intense involvement in the TraumaRegister DGU®.

Funding

No funding.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ACCP-SCCM

American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine

- AIS

Abbreviated Injury Scale

- ATLS

Advanced Trauma Life Support®

- AUC

Academy for Trauma Surgery

- BE

Base Excess

- BP

Blood pressure

- CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- DGU

German Association for Trauma Surgery

- FFP

Fresh-Frozen Plasma

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- GOS

Glasgow Outcome Scale

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- INR

International Normalized Ratio

- ISS

Injury Severity Score

- MOF

Multiple organ failure

- MV

Mean Value

- NIS

Committee on Emergency Medicine, Intensive Care and Trauma Management

- pRBC

Packed red blood cells

- PTT

Prothrombin time

- RISC

Revised Injury Severity Classification

- RR

Respiratory rate

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- SPSS®

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- TBI

Traumatic Brain Injury

Authors’ contributions

BH, SL and HCP conceived the presented idea. RL, MH, PJ and TM developed the theoretical formalism, performed the analytic calculations and performed the numerical simulations. BH and RL verified the analytical methods. SL encouraged BH to investigate the method part and supervised the findings of this part. BH and HCP supervised the project with help from FH and CS. BH, FH, PJ, TM, CS and MH contributed to the interpretation of the results. FH and CS designed the figures. BH and PJ took the lead in writing the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received the full approval in written form by the ethics committee of the University of Duisburg-Essen (internal number: 16-6922-BO).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bjoern Hussmann, Phone: 0049 (0) 201 43441101, Email: bjoern.hussmann@krupp-krankenhaus.de.

Carsten Schoeneberg, Email: carsten.schoeneberg@krupp-krankenhaus.de.

Pascal Jungbluth, Email: pascal.jungbluth@med.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Matthias Heuer, Email: chirurgie@st-elisabeth-hospital.de.

Rolf Lefering, Email: rolf.lefering@uni-wh.de.

Teresa Maek, Email: teresa.maek@krupp-krankenhaus.de.

Frank Hildebrand, Email: fhildebrand@ukaachen.de.

Sven Lendemans, Email: sven.lendemans@krupp-krankenhaus.de.

Hans-Christoph Pape, Email: hans-christoph.pape@usz.ch.

References

- 1.Hess JR, Brohi K, Dutton RP, Hauser CJ, Holcomb JB, Kluger Y, et al. The coagulopathy of trauma: a review of mechanisms. J Trauma. 2008;65(4):748–754. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181877a9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teixeira PG, Inaba K, Hadjizacharia P, Brown C, Salim A, Rhee P, Browder T, Noguchi TT, Demetriades D. Preventable or potentially preventable mortality at a mature trauma center. J Trauma. 2007;63(6):1338–1346. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815078ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruen RL, Jurkovich GJ, McIntyre LK, Foy HM, Maier RV. Patterns of errors contributing to trauma mortality: lessons learned from 2,594 deaths. Ann Surg. 2006;244(3):371–380. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234655.83517.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Søreide K, Krüger AJ, Vårdal AL, Ellingsen CL, Søreide E, Lossius HM. Epidemiology and contemporary patterns of trauma deaths: changing place, similar pace, older face. World J Surg. 2007;31(11):2092–2103. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lendemans S, Kreuzfelder E, Waydhas C, Nast-Kolb D, Flohé S. Clinical course and prognostic significance of immunological and functional parameters after severe trauma. Unfallchirurg. 2004;107(3):203–210. doi: 10.1007/s00113-004-0729-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, Moser KS, Brennan R, Read RA, et al. Epidemiology of trauma deaths: a reassessment. J Trauma. 1995;38:185–193. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199502000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma . ATLS student course manual. 9. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bickell WH, Stern S. Fluid replacement for hypotensive injury victims: how, when and what risks? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 1998;11(2):177–180. doi: 10.1097/00001503-199804000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bickell WH, Barrett SM, Romine-Jenkins M, Hull SS, Jr, Kinasewitz GT. Resuscitation of canine hemorrhagic hypotension with large-volume isotonic crystalloid: impact on lung water, venous admixture, and systemic arterial oxygen saturation. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bickell WH. Are victims of injury sometimes victimized by attempts at fluid resuscitation? Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curry N, Davis PW. What’s new in resuscitation strategies for the patient with multiple trauma? Injury. 2012;43(7):1021–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geeraedts LM, Jr, Pothof LA, Caldwell E, de Lange-de Klerk ES, D'Amours SK. Prehospital fluid resuscitation in hypotensive trauma patients: do we need a tailored approach? Injury. 2015;46(1):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albreiki M, Voegeli D. Permissive hypotensive resuscitation in adult patients with traumatic haemorrhagic shock: a systematic review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44(2):191–202. doi: 10.1007/s00068-017-0862-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dula DJ, Wood GC, Rejmer AR, Starr M, Leicht M. Use of prehospital fluids in hypotensive blunt trauma patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6(4):417–420. doi: 10.1080/10903120290938058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talving P, Palstedt J, Riddez L. Prehospital management and fluid resuscitation in hypotensive trauma patients admitted to Karolinska University hospital in Stockholm. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2005;20(4):228–234. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00002582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussmann B, Taeger G, Lefering R, Waydhas C, Nast-Kolb D, Ruchholtz S, et al.; TraumaRegister der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie. Lethality and outcome in multiple injured patients after severe abdominal and pelvic trauma: influence of preclinical volume replacement - an analysis of 604 patients from the trauma registry of the DGU. Unfallchirurg 2011;114(8):705-712. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Hussmann B, Lefering R, Waydhas C, Touma A, Kauther MD, Ruchholtz S, et al.; Trauma Registry of the German Society for Trauma Surgery. Does increased prehospital replacement volume lead to a poor clinical course and an increased mortality? A matched-pair analysis of 1896 patients of the trauma registry of the German Society for Trauma Surgery who were managed by an emergency doctor at the accident site. Injury 2013;44(5):611-617. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Huβmann B, Lefering R, Taeger G, Waydhas C, Ruchholtz S, Sven Lendemans and the DGU Trauma Registry Influence of prehospital fluid resuscitation on patients with multiple injuries in hemorrhagic shock in patients from the DGU trauma registry. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4(4):465–471. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.86630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussmann B, Lefering R, Kauther MD, Ruchholtz S, Moldzio P, Lendemans S, TraumaRegister DGU® Influence of prehospital volume replacement on outcome in polytraumatized children. Crit Care. 2012;16:201. doi: 10.1186/cc11809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagoda A, John Bruns J. Prehospital management of traumatic brain injury. In: Leon-Carrion J, Wild KRH, Zitney GA, editors. Brain injury treatment: theories and practices. 1. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prabhakar H, Sandhu K, Bhagat H, Durga P, Chawla R. Current concepts of optimal cerebral perfusion pressure in traumatic brain injury. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30(3):318–327. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.137260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen EF, Deakin CD, Vilke GM, Lippert FK. Prehospital care and trauma systems. In: Wilson WC, Grande CM, Hoyt DB, editors. Trauma: emergency resuscitation perioperative Anaesthesia surgical management. 1. New York: Informa Health Care; 2007. pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussmann B, Heuer M, Lefering R, Touma A, Schoeneberg C, Keitel J, Lendemans S. Prehospital volume therapy as an independent risk factor after trauma. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:354367. doi: 10.1155/2015/354367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartings JA, Vidgeon S, Strong AJ, Zacko C, Vagal A, Andaluz N, et al., Co-Operative Studies on Brain Injury Depolarizations. Surgical management of traumatic brain injury: a comparative-effectiveness study of 2 centers. J Neurosurg 2014;120(2):434-446. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on Sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lefering R. Development and validation of the revised injury severity classification (RISC) score for severely injured patients. Europ J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2009;35:437–447. doi: 10.1007/s00068-009-9122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner J, Nicholl J, Webber L, Cox H, Dixon S, Yates D. A randomized controlled trial of prehospital intravenous fluid replacement therapy in serious trauma. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4:1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trunkey DD. Prehospital fluid resuscitation of the trauma patient. An analysis and review. Emerg Med Serv. 2001;30:93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geeraedts LM, Jr, Kaasjager HA, van Vugt AB, Frölke JP. Exsanguination in trauma: a review of diagnostics and treatment options. Injury. 2009;40:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soudry E, Stein M. Prehospital management of uncontrolled bleeding in trauma patients: nearing the light at the end of the tunnel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6(8):485–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pepe PE, Mosesso VN, Falk JL. Prehospital fluid resuscitation of the patient with major trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6(1):81–91. doi: 10.1080/10903120290938887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Oliveira Manoel AL, Neto AC, Veigas PV, Rizoli S. Traumatic brain injury associated coagulopathy. Neurocrit Care. 2015;22(1):34–44. doi: 10.1007/s12028-014-0026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sulheim S, Holme I, Ekeland A, Bahr R. Helmet use and risk of head injuries in alpine skiers and snowboarders. JAMA. 2006;295(8):919–924. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.8.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haut ER, Kalish BT, Cotton BA, Efron DT, Haider AH, Stevens KA, et al. Prehospital intravenous fluid administration is associated with higher mortality in trauma patients: a National Trauma Data Bank analysis. Ann Surg. 2011;253:371–377. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318207c24f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan PG, Cincotta M, Clavisi O, Bragge P, Wasiak J, Pattuwage L, et al. Review article: prehospital fluid management in traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2011;23(6):665–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dutton RP, Mackenzie CF, Scalea TM. Hypotensive resuscitation during active hemorrhage: impact on in-hospital mortality. J Trauma. 2002;52(6):1141–1146. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200206000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.