Abstract

Context:

Pyogenic meningitis is often a devastating condition which is diagnosed by analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained by lumbar puncture (LP). CSF thus obtained can get contaminated with peripheral blood leucocytes during LP which renders it unusable for cytological analysis. Leucocyte esterase strips are available for identifying leucocyte esterase activity in urine and other body fluids which suggest inflammation. We conducted this experiment to see whether the leucocyte esterase strip can differentiate between neutrophils invited at the inflammatory site and circulating neutrophils in CSF.

Aim:

To compare the diagnostic ability of the leucocyte esterase test between pyogenic meningitis and CSF contaminated with circulating neutrophils.

Setting and Design:

Prospective analytical study conducted in a tertiary care hospital.

Materials and Methods:

The CSF samples of pyogenic meningitis patients were analyzed for leucocyte esterase activity. The other group was normal CSF which was deliberately contaminated with buffy coat preparation, and leukocyte esterase activity was determined.

Statistical Analysis:

Diagnostic ability of a test in terms of sensitivity and specificity.

Results:

Overall sensitivity of the dipsticks in diagnosing pyogenic meningitis is 81% and specificity is 99%. When compared with experimentally contaminated CSF sample, a reading of 2+ on the strip had a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 100% for pyogenic meningitis.

Conclusion:

Leucocyte esterase strip is specific for pyogenic meningitis (activated neutrophils), and hence can differentiate from CSF contaminated with blood.

Keywords: Blood contamination, cerebrospinal fluid, leucocyte esterase, pyogenic meningitis

INTRODUCTION

Pyogenic meningitis is a life-threatening central nervous system infection with a high mortality and disability rate.[1] Raised polymorph count in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is diagnostic of pyogenic meningitis in symptomatic patients.[2] However, CSF pleocytosis may not be pronounced in immune-suppressed patients.[3,4]

CSF is a clear and transparent fluid containing less than five white blood cells (WBCs) per cubic millimeter. The presence of more than five polymorphs indicates acute inflammation.[5] With progression of the disease or with treatment, polymorphs will be gradually replaced by lymphocytes. At this stage, differentiating from viral or tubercular meningitis will be a challenge.[6,7]

CSF is procured for analysis by lumbar puncture (LP). It is an invasive and often blind procedure resulting in contamination with peripheral blood due to micro trauma.[8,9] Under such circumstances, circulating neutrophils may interfere with the interpretation of differential cell counting due to inability to differentiate the true inflammatory polymorphs of meningitis with circulating neutrophils. Obtaining WBC-to-red-blood-cell (RBC) ratio has been in vogue as an attempt to interpret CSF contaminated with blood.[10,11] However, this has not resolved the diagnostic dilemma in cytological analysis of CSF.

Cytochemical test to detect the leucocyte esterase activity of the neutrophils in the urine is used in the diagnosis of urinary tract infection.[12,13] Several authors have successfully used commercially available leucocyte esterase strip for identifying polymorphs in CSF.[14,15] The same has been shown to be useful in indicating infection in other body fluids such as ascetic, synovial, and amniotic fluid as well.[16,17,18]

However, the question of whether this test can reliably differentiate between circulating neutrophils and inflammatory polymorphs in CSF remains unanswered. Strip's ability to differentiate between these two would nearly settle the challenge of interpreting blood-contaminated CSF in pyogenic meningitis.

We primarily aimed to determine the diagnostic ability of leucocyte esterase strip in blood-contaminated CSF in pyogenic meningitis. We also set out to determine the overall diagnostic ability of leucocyte esterase strip in pyogenic meningitis.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study subjects

All the patients admitted to our hospital with a presumptive diagnosis of pyogenic meningitis and had undergone LP for CSF analysis formed our study subjects. Insufficient samples, samples standing for more than 1 h before reaching the laboratory, and samples with clinical suspicion of malignancy were excluded from the study.

Study design

This is a prospective analytical study conducted in a tertiary healthcare setup between March and August 2017.

Sample collection and preparation

All the CSF samples with a presumptive clinical diagnosis of meningitis were received with regular identification formalities and processed within half an hour of receipt as per the laboratory protocol. The commercially available leucocyte esterase dipstick contains cetates which get converted into phenols due to the action of leucocyte esterase. Phenols are detected using appropriate color indicators. The dipstick also serves as a semi-quantitative test as the intensity of the color increases with an increase in the concentration of leucocyte esterase.

A drop of CSF thus obtained was dropped on the leucocyte esterase strip (UroColor 10; Standard Diagnostic Inc., Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) and the color change noted. Following this, the pathologist performed the cell count using Neubauer counting chamber using standard technique. The sample was spun in the cytospin, and cell concentrate was used for cytological analysis. Samples with blood tinge on naked eye examination or an RBC count of more than 500 cells/mm3 on microscopy were classified as blood-contaminated samples. These samples were not used for comparison as it was not possible to interpret.[10] Instead, we experimentally contaminated normal CSF with blood and proceeded.

Experimental contamination of CSF

Unspun CSF samples which were analyzed and found to be normal (no meningitis) were pooled and stored in the refrigerator. The stored normal CSF was distributed into 12 test tubes with a volume of 0.5 mL in each. These tubes were now grouped into four sets with three tubes in each set. Each set was named from A to D.

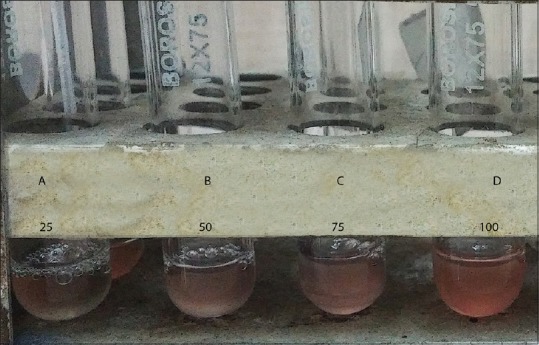

Two milliliter of buffy coat layer of the blood was obtained from the blood bank which was used for contaminating the normal CSF. Using micropipette, 25 μL of buffy coat layer was added to each test tube in set A, 50 μL to each tube in set B, 75 μL into each tube in set C, and 100 μL into each tube in set D [Figure 1]. Polymorph count was done on all these tubes with Neubauer chamber using standard technique.

Figure 1.

Experimental contamination of CSF with buffy coat

Ethics

Institutional ethical board approved this study.

Statistical analysis

Based on a pilot study of 20 cases, in which the sensitivity and specificity of the leucocyte esterase strip were 80% and 85%, respectively, and 26% of the sample suggested meningitis, we needed 188 samples. We calculated for a precision of 10% for specificity. The demographic details were collected using laboratory information system of the hospital. All the relevant data were entered in the case report form prepared using Microsoft Excel 2016. Continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range depending on the distribution. The diagnostic ability of the test was reported as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values. We also calculated likelihood ratios.

RESULTS

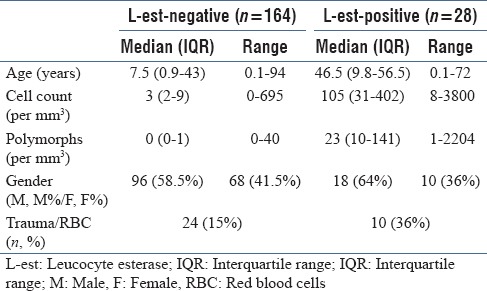

We studied a total of 192 samples, of which 34 were traumatic. In all, 164 tested negative (strip-negative) for leucocyte esterase, of which 24 were traumatic. Out of 28 samples which tested positive (strip-positive), 10 were traumatic. About 27% patients in the strip-negative group and 14% in strip-positive group were below 1 year of age. Table 1 depicts the baseline data.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

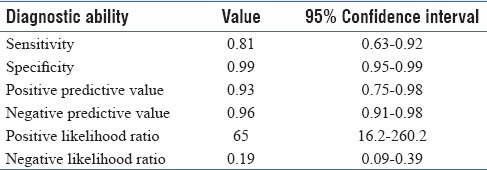

There were 32 patients diagnosed as pyogenic meningitis based on CSF polymorph count of more than five. The diagnostic ability of the leucocyte esterase strip in diagnosing meningitis is depicted in Table 2. When the traumatic (blood contaminated during LP) CSF alone was grouped and analyzed, the leucocyte esterase strip had a sensitivity of 90% [95% confidence interval (CI) 54%–99%), specificity of 79% (95% CI 57%–92%), positive predictive value of 64% (95% CI 35%–86%), and negative predictive value of 95% (95% CI 73%–99%).

Table 2.

Overall diagnostic ability of the leucocyte esterase strip

Experimentally contaminated CSF had polymorph count ranging from 32 to 2016 cells/mm3. Sets A, B, C, and D had a mean (standard deviation) polymorph count of 50 (16), 336 (83), 576 (0), and 1488 (463), respectively. All these samples resulted in a very faint color change not exceeding 1+ on the manufacturer's color scale.

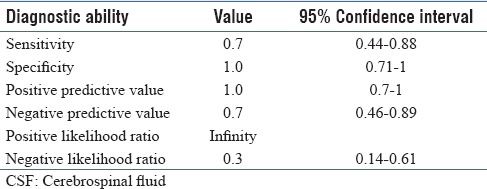

There were 18 samples which were nontraumatic and strip-positive. Except for one, all other samples had a polymorph count of more than five. We compared this group with experimentally contaminated CSF group which contained circulating neutrophils and did not have the disease. In view of our earlier observation that experimentally contaminated group may show a faint color change, we analyzed the results with an upscaled cut-off at least 2+ to be considered as strip-positive. With this, specificity and positive predictive value of the leucocyte esterase strip increased to 100%. The detailed diagnostic ability parameters are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Diagnostic ability of leucocyte esterase strip in CSF contaminated with blood (strip reading >1+)

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic meningitis should be diagnosed and treated as soon as possible. Leucocyte esterase strip test has shown a reasonable sensitivity and high specificity in diagnosing pyogenic meningitis.

The overall diagnostic ability of the leucocyte esterase strip seen in our study is like several previous reports.[14,15] This supports the argument encouraging the use of leucocyte esterase strip in addition to other cytological analysis of CSF in suspected pyogenic meningitis. Our study also shows that when used on CSF contaminated with blood, the specificity remains high. The lower sensitivity in this sample is due to difficulty in interpreting traumatic CSF.

Blood contamination of CSF is reported in up to 40% of the samples.[10] The presence of intracranial bleed can further complicate the picture due to the presence of blood in CSF. The diagnostic challenges in differentiating traumatic contamination and intracranial bleed are addressed by the technique of collecting CSF in multiple tubes and noting the clearance of CSF at the end.[18] However, this is neither full-proof nor it is easy to obtain larger volume of CSF in many patients. Hence, using the same technique in pyogenic meningitis is practically difficult.

Having the CSF contaminated with blood when we need to have certainty in diagnosis like pyogenic meningitis would be frustrating as the risky and invasive procedure is rendered uninterpretable. A reliable test that can be used even in blood-contaminated CSF samples is invaluable for management of pyogenic meningitis. Leucocyte esterase test which has been extensively used in bedside detection of urinary tract infection has shown promise in bacterial peritonitis and meningitis as well.[14,15,17,19,20] Behavior of this test in blood-contaminated samples has not been studied.

We compared a clean sample with inflammatory polymorphs (infection) and blood-contaminated sample with circulating neutrophils (representing traumatic contamination without infection) to study the diagnostic ability of leucocyte esterase test. As there could be weak positivity due to leucocyte esterase present in circulating neutrophils, we took a stronger reaction (2+ and above) to categorize strip positivity. Analysis showed the specificity of the strip positivity to be 100% albeit with a lowered sensitivity. This is understandable as we have disregarded faint color change (1+) to diagnose the presence of infection. This has a significant clinical implication as one can be sure of the presence of meningeal infection if the strip shows stronger positive reaction irrespective of blood contamination. The currently existing method to make sense of CSF picture in case of blood contamination is with WBC correction for RBC count.[5,8,10,11] This is very much dependent on the correction factor one would choose. To give an example, if a blood-contaminated CSF is analyzed and it shows 30,000 RBCs and 64 WBCs, depending on the correction factor chosen, for example, 300, 500, or 700, the same WBC count in blood-contaminated CSF can be interpreted as no infection, inconclusive, or infection. This error proneness can be devastating for a given patient. Hence, using test like leucocyte esterase strip which is both objective and specific is highly desirable in CSF analysis.

We noted that the proportion of small children and neonates was higher in the leucocyte esterase strip-negative group. This is because the signs of meningitis are nonspecific in small children and neonates. This necessitates the pediatricians to have high index of suspicion and perform LPs more often.

For neonates and young children, age-specific CSF cell counts have been published earlier.[8,9,21] An important issue is with the cytological criteria for diagnosis of pyogenic meningitis in newborns. It is interesting to note that all these studies have obtained samples from children who had some symptoms suspicious of neuroinfection and later recovered without progressing clinically to frank meningitis. The question that remain unanswered in all these studies is how many of these neonates had very early stage of meningitis and recovered with first few doses of appropriate antibiotics? Hence, the question of normal cell count in CSF of neonates remains unsettled. We found an interesting study by Martín-Ancel et al.[22] where the CSF was obtained from normal neonates of mothers who had serodiagnosis of toxoplasmosis as per their protocol. These neonates were completely asymptomatic and did not receive any treatment. We strongly believe this to be most representative sample of normal CSF in neonates. The cell counts in this study did not differ from the adult values, and hence we have considered polymorphs of more than five in CSF of neonates to be indicative of neuroinfection.

CONCLUSION

Strong reaction (2+ and above) on leucocyte esterase strip is highly specific for diagnosing pyogenic meningitis even in blood-contaminated CSF samples.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Debnath DJ, Wanjpe A, Kakrani V, Singru S. Epidemiological study of acute bacterial meningitis in admitted children below twelve years of age in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Pune, India. Med J DY Patil Univ. 2012;5:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conly JM, Ronald AR. Cerebrospinal fluid as a diagnostic body fluid. Am J Med. 1983;75:102–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishbein DB, Palmer DL, Porter KM, Reed WP. Bacterial meningitis in the absence of CSF pleocytosis. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:1369–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao SP, Schmalzer E, Kaufman M, Brown AK. Meningitis in patients with sickle cell anemia: Normocellular CSF at diagnosis. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1983;5:101–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouwer MC, Thwaites GE, Tunkel AR, Van de BeekD. Dilemmas in the diagnosis of acute community-acquired bacterial meningitis. Lancet. 2012;380:1684–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blazer S, Berant M, Alon U. Effect of antibiotic treatment on cerebrospinal fluid. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983;80:386–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/80.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonadio WA, Smith D. Cerebrospinal fluid changes after 48 hours of effective therapy for Hemophilus influenzae type B meningitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:426–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazor SS, McNulty JE, Roosevelt GE. Interpretation of traumatic lumbar punctures: Who can go home? Pediatrics. 2003;111:525–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kestenbaum LA, Ebberson J, Zorc JJ, Hodinka RL, Shah SS. Defining cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell count reference values in neonates and young infants. Pediatrics. 2010;125:257–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg RG, Smith PB, Cotton CM, Moody MA, Clark RH, Benjamin DK., Jr Traumatic lumbar punctures in neonates: Test performance of the cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell count. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:1047–51. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31817e519b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonadio WA, Smith DS, Goddard S, Burroughs J, Khaja G. Distinguishing cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in children with bacterial meningitis and traumatic lumbar puncture. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:251–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lejeune B, Baron R, Guillois B, Mayeux D. Evaluation of a screening test for detecting urinary tract infection in newborns and infants. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:1029–30. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.12.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw KN, McGowan KL, Gorelick MH, Schwartz SJ. Screening for urinary tract infection in infants in the emergency department: Which test is best? Pediatrics. 1998;101:1–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bortcosh W, Siedner M, Carroll RW. Utility of the urine reagent strip leucocyte esterase assay for the diagnosis of meningitis in resource-limited settings: Meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:1072–80. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLozier JS, Auerbach PS. The leukocyte esterase test for detection of cerebrospinal fluid leukocytosis and bacterial meningitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:1191–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanbiervliet G, Rakotoarisoa C, Filippi J, Guérin O, Calle G, Hastier P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid urine-screening test (Multistix8SG) in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1257–60. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braga LL, Souza MH, Barbosa AM, Furtado FM, Campelo PA, Araújo Filho AH. Diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients in northeastern Brazil by use of rapid urine-screening test. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006;124:141–4. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802006000300006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omar M, Ettinger M, Reichling M, Petri M, Lichtinghagen R, Guenther D, et al. Preliminary results of a new test for rapid diagnosis of septic arthritis with use of leucocyte esterase and glucose reagent strips. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:2032–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edlow JA, Caplan LR. Avoiding pitfalls in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:29–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001063420106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bachur R, Harper MB. Reliability of the urinalysis for predicting urinary tract infections in young febrile children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:60–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed A, Hickey SM, Ehrett S, Trujillo M, Brito F, Goto C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid values in the term neonate. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:298–303. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199604000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martín-Ancel A, García-Alix A, Salas S, Del Castillo F, Cabañas F, Quero J. Cerebrospinal fluid leucocyte counts in healthy neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:357–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.082826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]