Abstract

Background/main objectives:

No effective strategy exists to treat the well-recognized, devastating impact of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which is the brain degeneration likely caused by repeated head trauma. The goals of this project were (1) to study the effects of single and recurrent TBI (rTBI) on Drosophila melanogaster’s (a) life span, (b) response to sedatives, and (c) behavioral responses to light and gravity and (2) to determine whether therapeutic hypothermia can mitigate the deleterious effects of TBI.

Methods:

Five experimental groups were created: (1) control, (2) single TBI or concussion; (3) concussion + hypothermia, (4) rTBI, and (5) rTBI + hypothermia. A “high-impact trauma” (HIT) device was built, which used a spring-based mechanism to propel flies against the wall of a vial, causing mechanical damage to the brain. Hypothermia groups were cooled to 15°C for 3 minutes. Group differences were analyzed with chi-square tests for the categorical variables and with ANOVA tests for the continuous variables.

Results:

Survival curve analysis showed that rTBI can decrease Drosophila lifespan and hypothermia diminished this impact. Average sedation time for control vs concussion vs concussion + hypothermia was 78 vs 52 vs 61 seconds (P < .0001). Similarly, rTBI vs rTBI/hypothermia groups took 43 vs 59 seconds (P < .0001). Concussed flies preferred dark environments compared with control flies (risk ratio 3.3, P < .01) while flies who were concussed and cooled had a risk ratio of 2.7 (P < .01). Flies with rTBI were almost 4 times likely to prefer the dark environment but only 3 times as likely if they were cooled, compared with controls. Geotaxis was significantly affected by rTBI only and yet less so if rTBI flies were cooled.

Conclusions:

Hypothermia successfully mitigated many deleterious effects of single TBI and rTBI in Drosophila and may represent a promising breakthrough in the treatment of human TBI.

Keywords: Recurrent TBI, hypothermia, concussion, Drosophila melanogaster

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major public health concern and a leading international cause of morbidity and mortality.1 In the United States, approximately 1.6 million to 3.8 million sports-related TBIs occur on a yearly basis.2 The prevalence of TBI among returning military service members ranges from 15.2% to 22.8%, affecting as many as 320 000 troops.3 Concussion is the most common form of acute TBI in high-impact sports and military settings and is frequently referred to as mild TBI (mTBI). Acute concussion does not usually cause any identifiable abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized tomography (CT) scans and is diagnosed based on symptoms such as headache, dizziness, cognitive dysfunction, mood, and sleep problems. About 80% to 90% of concussions usually resolve in 7 to 10 days, but the recovery time for young children is longer.2

It is now recognized that recurrent episodes of even mTBI in contact sports can lead to neurodegenerative changes and culminate into a devastating condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). This condition is characterized by loss of balance, slower movements, tremors, and behavioral disturbances including mood swings, aggression, and even suicide.4 A study of deceased football players found the presence of CTE in 87% of the sample.5 Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is characterized by brain atrophy, extensive tau-immunoreactive neurofibrillary tangles, astrocytic tangles, spindle-shaped neurites throughout the brain, and marked accumulation of tau-immunoreactive astrocytes.6 A recent study reported that even hits to the brain not severe enough to cause a concussion can lead to pathologic changes in the brain associated with CTE.7 Despite the well-recognized, devastating impact of TBI, no effective strategy exists to treat such disorders or to decrease the risk of long-term neurologic consequences.

One factor that has been shown to worsen the effects of TBI is hyperthermia or increased body temperature.8 Early fever is common after human TBI and is associated with more severe clinical presentation and with the presence of diffuse axonal injury, cerebral edema, and inflammation.9 Hyperthermia increases metabolic expenditure, glutamate release, and inflammatory activity that may further exacerbate neuronal damage.10 If hyperthermia is known to exacerbate the consequences of TBI, could there be a therapeutic role for mild hypothermia to mitigate some of those effects? Theoretically, hypothermia should mitigate the toxic effects of trauma which include excitotoxicity, free radical-induced alterations, inflammatory events, and disruption of the blood-brain barrier.11 Hypothermia has been shown to inhibit apoptotic cell death after TBI by modulation of secondary cellular mediators, as well as decrease inflammatory mediators and also diminish glutamate uptake by neurons thereby attenuating excitotoxicity.11 Studies have been conducted to determine the utility of hypothermia in severe TBI patients, but they possess conflicting results.12 However, this question has not been formally studied in any of the groups at high risk for recurrent TBI (rTBI), which can lead to CTE.

The main purpose of this project was to create an animal model of single TBI and rTBI, using Drosophila melanogaster, and determine whether therapeutic hypothermia (or body cooling) can successfully mitigate the negative short- and long-term effects of TBI on the organism. This study used a “high-impact trauma” (HIT) device to inflict TBI on the flies using a previously described protocol.13 Just as other human neurodegenerative disorders, TBI has been modeled in Drosophila and it was found that fundamental characteristics of human TBI also occur in flies.13,14 The fly and human brain have similar structural and molecular features and the fly cuticle, like the human cranium, is relatively inflexible and protects the fly brain from environmental insults. Furthermore, using flies has already provided novel insights into neurodegeneration, memory, and sleep, all of which are also affected in human TBI.15–17

If temperature control could improve mTBI outcomes or lessen the likelihood of CTE from rTBI, then it is crucial that we study this intervention systematically, and using an animal model would be a first step in this major initiative. Drosophila, being ectotherms, cannot endogenously regulate body temperature and essentially take on the temperature of their environments as long as this is physiologically permissible.18 Prior research has shown that hypothermia or cooling Drosophila to 17°C has a protective effect on brain potassium homeostasis during repetitive anoxia.19 Cold temperature has also been shown to improve mobility and survival in Drosophila models of autosomal-dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia.20

In this study, we hypothesized that (1) single TBI or concussion and rTBI will lead to a measurable negative impact on Drosophila melanogaster’s (a) life span, (b) response to sedatives, and (c) behavioral responses to light and gravity and (2) therapeutic hypothermia will mitigate the deleterious effects of single TBI and rTBI.

Hypothermia is a well-established intervention for certain types of hypoxic-ischemic injury in humans. If therapeutic hypothermia can successfully mitigate the deleterious effects of single TBI and rTBI in an animal model, then this could have tremendous implications for the treatment of human TBI as well.

Methods and Materials

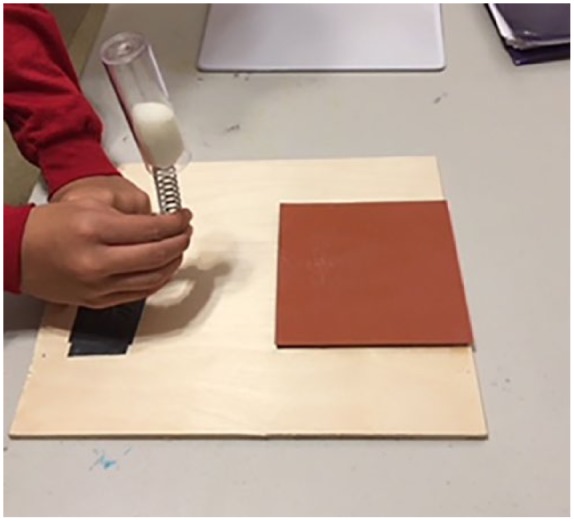

Flies were obtained from Carolina Biological Company (wild-type, Oregon R strain Drosophila). Flies were maintained on formula 4-24® Instant Drosophila Blue Medium, also obtained from Carolina Biological, at 25°C unless otherwise stated. As previously developed by Katzenberger and colleagues, a fly model of TBI was created by inflicting mechanical injury on flies using rapid acceleration and deceleration forces.13 This produces outcomes that are similar to those of closed head TBI in humans.13 A HIT device was constructed, consisting of a metal spring clamped at one end to a wooden board with the free end positioned over a polyurethane pad (Figure 1). When the spring is deflected and released, the vial contacts the pad and the flies contact the vial and rebound, providing a model of TBI. The degree of injury can be adjusted by changing the extent of the deflection or by varying the number of strikes.

Figure 1.

The HIT device was used to inflict TBI in the flies. The image shows the HIT deflected to 90° before a strike. HIT indicates high-impact trauma; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Katzenberger and colleagues showed that deflection of the spring to 90° resulted in an impact velocity of ∼3.0 m/s (6.7 miles/h) and an average force of 2.5 N. Those flies subjected to a single strike with the spring deflected to 90° became temporarily incapacitated and fell to the bottom of the vial; however, there was no obvious external damage to the head, body, or appendages. During the first minute after a strike, 8.8% ± 3.8% of flies were incapacitated, but most of these flies recovered locomotor activity within 5 minutes, as measured by climbing ability. Although mobility was reduced, it gradually returned over a 2-day period. The immediate loss of motor ability, followed by ataxia and gradual recovery of mobility were reminiscent of concussion in humans and consistent with the idea that the HIT device inflicts brain injury in flies.13 We observed a very similar response to single TBI in our experiment.

Traumatic injury and hypothermia

A deflection angle of 90° was used to simulate a concussion. To model rTBI (which possibly leads to CTE), a total of 4 hits were applied over a 48-hour period, with hits on a given day being 10 hours apart. Moderate hypothermia in human trials was considered to be between 32°C and 34.5°C, which is approximately 1° to 5° lower than normal human body temperature. Therefore, our goal was to change the fly’s environmental temperature to 5° to 6° below its baseline. Hypothermia was induced for 3 minutes, in a refrigerator, at temperature of 16°C similar to prior experiments testing hypothermia effects on Drosophila. In the rTBI cohorts, flies were immediately cooled after each individual hit.

A 1-day recovery period was allowed after concussion or rTBI, prior to starting the behavioral assays. The Katzenberger model of TBI showed that primary injuries cause death within 24 hours only if the injuries exceed a specific threshold. In addition, death from primary injuries was complete after 24 hours because the percent survival at 24 hours was not substantially different from the percent survival at 48 hours. Our experiment involved 5 experimental groups and 3 types of outcomes were measured (Table 1).

Table 1.

Experimental design.

| Experimental groups | Outcomes |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviation: rTBI, recurrent traumatic brain injury.

Longevity

Twenty to 30 adult flies were placed in each of 3 vials, per condition. Flies were transferred to new vials every 3 days to avoid including their offspring in the longevity count. Flies were counted daily and number of dead flies, number of living flies, and the percentage of surviving flies were recorded.

Response to sedative

Approximately 20 to 30 flies were placed in a vial and time (in seconds) for each fly to be fully sedated after exposure to FlyNap (anesthetic) was noted. Three vials were used for each condition studied. Full sedation was assumed when all movement of wings and appendages ceased.

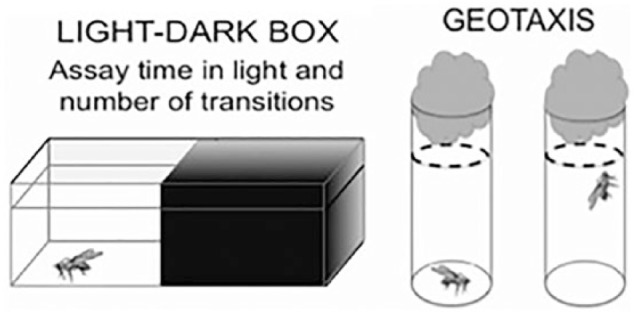

Behavioral assays—phototaxis and negative geotaxis

We used the behavioral assays previously established and described (Figure 2).21 Negative geotaxis is defined as the motion in response to the force of gravity. Flies placed in a vial were given 10 seconds to demonstrate negative geotaxis by migrating upward to a line 2 inches below the vial lid. Number of flies above the demarcated line, at 10 seconds, was recorded.

Figure 2.

The light-dark assay counts the number of flies in light and dark segments of the box, after TBI. Geotaxis assay involves tapping flies to bottom of the vial and counting how many flies reach the dashed line in 10 seconds. TBI indicates traumatic brain injury.21

Phototaxis represents the fly’s natural affinity to migrate toward light. Concussed flies are theoretically expected to deviate from this normal reflexive behavior and avoid light. A light-dark box was created using a plastic container covered with clear plastic wrap punctured with holes for adequate ventilation. Half of the box was covered with opaque black material and the other half remained open to light. Flies were released into the light-dark box and percentage of flies in each section at the end of 10 minutes was noted. Both response to sedative as well as the behavioral assays required the use of an iPhone video to record position and behavior of flies, corresponding to the needs of the assay.

For the longevity outcome, data were tabulated and graphed on survival curves using Microsoft Excel. Mean time for sedation was calculated, as well as standard errors. In addition, group differences were analyzed using the ANOVA single factor analysis tool, in google sheets. For the phototaxis and negative geotaxis assays, chi-square statistical tests were used. Risk ratio (RR) or relative risk is the ratio of the probability of an outcome for an exposed group to the probability of an outcome for the unexposed group. The relative risks to control were calculated using a chi-square test. The MedCalc software was used for this calculation. Together with risk difference and odds ratio, RR measures the association between the exposure and the outcome.

Both male and female flies were used for each assay, and experiments were not conducted on samples of either sex alone.

Results

A successful animal model of concussion and rTBI was created using Drosophila melanogaster and the HIT device.

Longevity

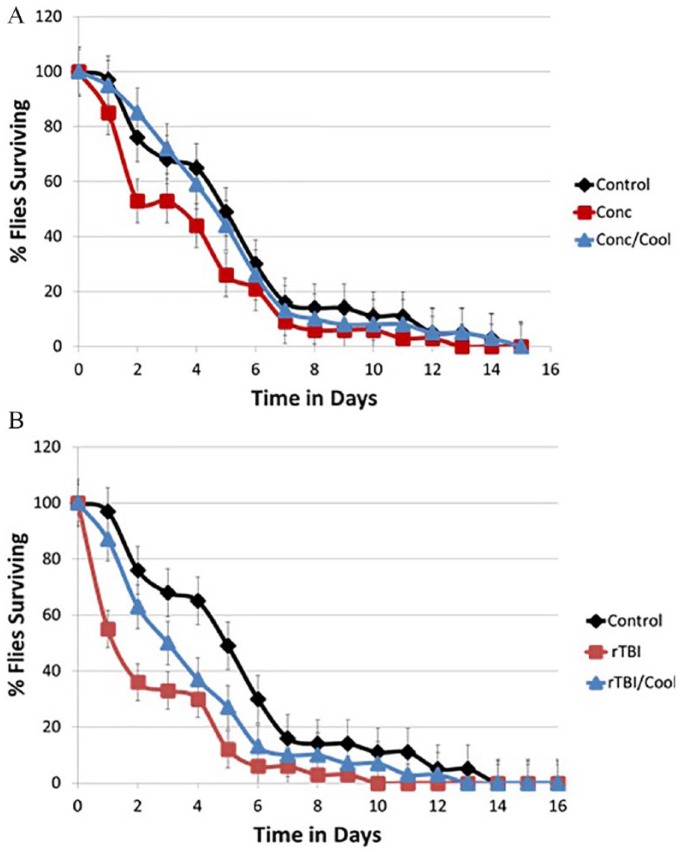

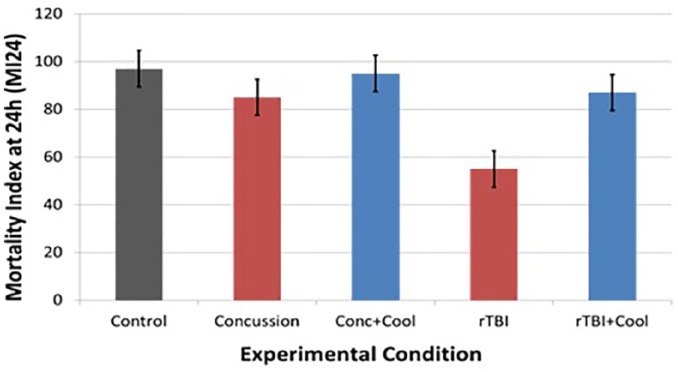

Survival curve analysis showed that rTBI decreased Drosophila lifespan, and hypothermia could successfully mitigate this impact (Figure 3B). The effect on lifespan was not as pronounced for mild TBI or concussion (see Figure 3A). Mortality Index at 24 hours (MI24) was calculated as the percentage of flies that survived 24 hours after injury. Figure 4 shows that concussion did not cause any appreciable decrease in the MI24, while rTBI did significantly decrease the mortality index.

Figure 3.

(A) The percent surviving flies, after a single TBI, is graphed vs time. Only flies that survived 24 hours after treatment were included in the analysis. (B) The percent surviving flies, after a recurrent TBI, is graphed vs time. Only flies that survived 24 hours after treatment were included in the analysis. TBI indicates traumatic brain injury.

Figure 4.

The percentage of flies that were surviving at 24 hours after injury or MI24 is demonstrated for all 5 experimental groups. The TBI groups are shown in red and the TBI + cooling groups are depicted in blue. Figure 4 shows that concussion did not cause any appreciable decrease in the MI24, while rTBI did significantly decrease the mortality index. MI24 indicates Mortality Index at 24 hours; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

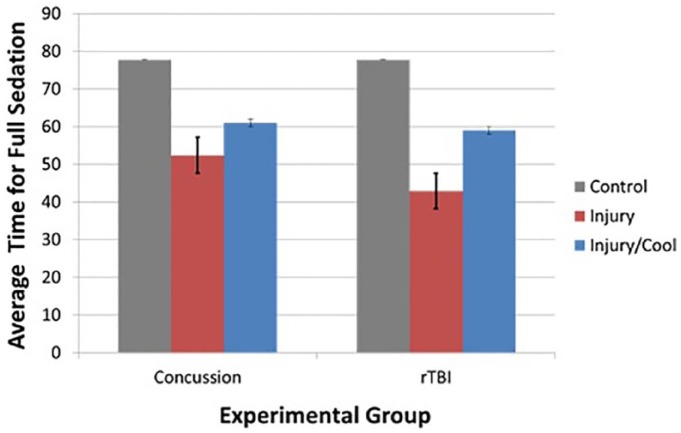

Time to sedate

Average time to sedate for control vs concussion vs concussed hypothermia was 78, 52, and 61 seconds, respectively (P < .0001). Similarly, the CTE vs CTE/hypothermia groups took 43 and 59 seconds (P < .0001) (Figure 5). However, a post hoc Tukey test showed that among the concussed flies, there was no significant difference between the concussion and concussed hypothermia groups (P = .193).

Figure 5.

Time taken for complete sedation after single and recurrent TBI is significantly less than in controls. Hypothermia mitigates this effect in both single and rTBI groups. rTBI indicates recurrent traumatic brain injury; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

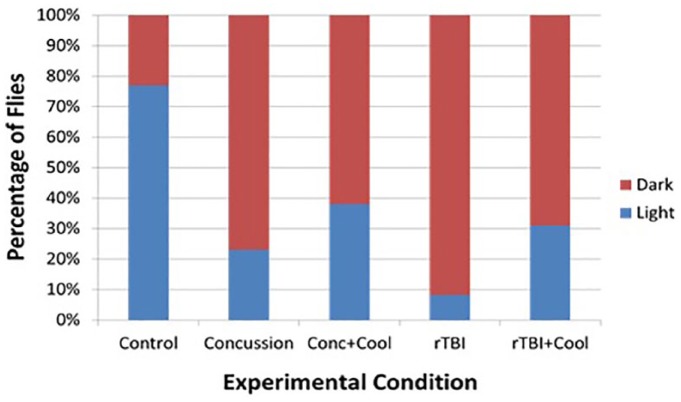

Phototaxis and geotaxis assays

Concussed flies preferred dark environments compared with control flies with a RR of 3.3 (P < .01), while flies who were concussed and cooled had a RR of 2.0 (P < .01). Flies with rTBI were almost 4 times likely (RR 3.83; P < .01) to prefer the dark environment but only about 3 times as likely (RR 2.93; P < .05) if they were cooled (Table 2). Figure 6 demonstrates the percentage of flies that prefer a dark vs light environment, and among both TBI groups, most flies prefer a dark environment. When these groups receive therapeutic hypothermia soon after their injury, more individuals can retain their normal affinity for light.

Table 2.

Proportion of flies with light avoidance reaction in light/dark box.

| Type of injury | n/total (%) | Relative risk to control (95% CI) | P | Relative risk to hypothermia (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None/control | 4/17 | 1.00 | NA | NA | NA |

| Concussion | 20/26 | 3.27 (1.35-7.90) | .008 | 1.230 (0.84-1.79) | .270 |

| Concussion + hypothermia | 15/24 | 2.65 (1.07-6.60) | .030 | ||

| rTBI | 28/31 | 3.83 (1.62-9.11) | .002 | 1.395 (1.06-1.85) | .016 |

| rTBI + hypothermia | 22/32 | 2.93 (1.20-7.10) | .018 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; rTBI, recurrent traumatic brain injury.

Figure 6.

This figure demonstrates the percentage of flies that prefer a dark vs light environment, and among both TBI groups, most flies prefer a dark environment. When these groups receive therapeutic hypothermia soon after their injury, more individuals can retain their normal affinity for light. TBI indicates traumatic brain injury.

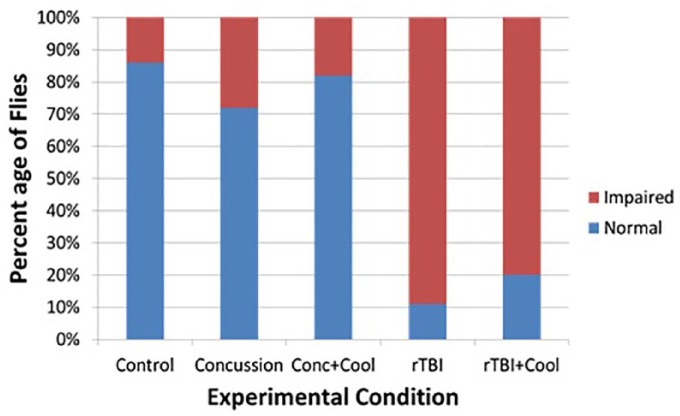

Geotaxis was not significantly impaired by concussion, but it was negatively affected by rTBI (RR 6.4, P < .01) and yet less so if rTBI flies were cooled (RR 5.8, P < .01) (Table 3). Figure 7 indicates the percentage of flies with impaired geotaxis for the various groups and we see that rTBI, but not concussion, caused a greater percentage of flies to have impaired geotaxis compared with the controls.

Table 3.

Proportion of flies with impaired geotaxis by type of injury.

| Type of injury | n/total (%) | Relative risk to control | P | Relative risk to hypothermia | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None/control | 5/31 | 1.00 | NA | NA | NA |

| Concussion | 11/40 | 1.98 | .16 | 1.38 | .39 |

| Concussion + hypothermia | 10/54 | 1.44 | .46 | ||

| rTBI | 53/60 | 6.36 | P < .0001 | 1.09 | .32 |

| rTBI + hypothermia | 36/44 | 5.83 | P < .0001 |

Abbreviation: rTBI, recurrent traumatic brain injury.

Figure 7.

Indicated above is the percentage of flies with impaired geotaxis for the various groups. We can see that rTBI, but not concussion, caused a greater percentage of flies to have impaired geotaxis compared with the controls. Hypothermia caused minimal improvement in this impairment.

Discussion

The main purpose of this project was to create an animal model of TBI (both single and recurrent) using Drosophila melanogaster and determine whether therapeutic hypothermia (or body cooling) can successfully mitigate the deleterious short- and long-term effects of TBI on the organism. This study, like prior research models, highlights the feasibility of using Drosophila to model traumatic brain injuries.13,14 The hypotheses presented here were partially confirmed. Recurrent TBI negatively affected lifespan, time to sedate, phototaxis, and geotaxis. Concussion negatively influenced time to sedate and phototaxis only. Remarkably, therapeutic hypothermia significantly reduced the deleterious effects of rTBI on lifespan, of concussion and rTBI on time to complete sedation, and rTBI on phototaxis. Positive effects of hypothermia were likely due to its ability to decrease inflammation, excitotoxicity, and cell death.11

Traumatic brain injury and lifespan

Concussed flies showed a trend toward shorter lifespan, but this did not persist across the length of the study. A subpopulation of flies experienced more than a mild TBI. Despite well-described neurologic manifestations, CTE is diagnosed with certainty only by neuropathological examination of brain tissue. Thus, no human studies have formally examined its impact on lifespan. In this project, rTBI decreased the median lifespan of flies by 77% and in comparison, by only 42%, when therapeutic hypothermia was applied after each hit. This work demonstrates, for the first time, that hypothermia can be a potential treatment for rTBI and may thereby prevent progression to CTE.

Traumatic brain injury and time to sedate

Not only rTBI but also concussion caused a significant decline in time required to sedate Drosophila. Thus, even a single TBI can dampen the brain’s arousal and alerting mechanisms such that it succumbs to anesthetics much more readily. Hypothermia successfully mitigated this effect among both concussed and rTBI flies.

Traumatic brain injury and reflex behaviors

Light sensitivity is a well-established symptom of concussion and both TBI groups avoided light. Hypothermia successfully mitigated this light aversion to some degree in the rTBI flies, but did not reach statistical significance in the concussed organisms perhaps due to a smaller sample size in the latter. Negative geotaxis is a validated behavioral assay and shown to be impaired among flies with neurodegenerative processes such as Alzheimer and Parkinson disease, as well as flies with CTE.14,22 This project confirmed these findings and also demonstrated a modest reduction in impaired geotaxis among the rTBI flies who had received therapeutic hypothermia after each hit. Concussed flies did not demonstrate altered geotaxis. Negative geotaxis represents the fly’s innate escape response and is likely a primitive and well-preserved reflex mediated by deeper brain structures, which are not affected by a single TBI alone.

Hypothermia can exert its beneficial effect after TBI through several different mechanisms including inhibition of apoptotic cell death, modulation of the inflammatory response that occurs after TBI, anti-oxidative stress, blockade of excitotoxic mechanisms, and attenuation of blood-brain-barrier permeability.11 Hypothermia is well-established as an intervention in certain types of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic injury.23 Future research is essential to elucidate the role hypothermia may play in single and recurrent human TBI and specifically regarding its timing, intensity, and duration.

Strengths and limitations

These findings are extremely exciting and demonstrate, for the first time, that we can use hypothermia to mitigate the devastating consequences of concussion and rTBI. This pilot study used relatively small numbers of flies. The study did not include an evaluation of neuropathologic correlations and therefore we could not definitively establish the presence of CTE in our rTBI flies. Future work should analyze the corresponding neuropathological changes associated with these phenotypic effects, so that we can better elucidate the neural mechanisms of TBI and the pathways by which hypothermia protects the brain from consequences of TBI. Also, the effect of hypothermia on flies without TBI is unknown and must be evaluated in future studies.

In Drosophila melanogaster, hypothermia can successfully mitigate many deleterious effects of concussion and rTBI measured by longevity, response to sedative, phototaxis, and geotaxis. Thus, hypothermia may represent a promising breakthrough in the treatment of human TBI as well. Future studies in larger animal models as well as humans are imperative so that we may stay ahead of the hit.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: SL- conception, design, acquisition of data, drafting article and critically revising article. JJ- design, supervising acquisition of data, critically revising article. AH- critically revising article, help with data analyses. JC- conception and critically revising article.

ORCID iD: Shan Lateef  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8821-481X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8821-481X

References

- 1. Johnson WD, Griswold WP. Traumatic brain injury: a global challenge. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:949–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Langois A, Rutland B, Wald M. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McKee AC, Robinson M. Military-related traumatic brain injury and neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:242–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ling H, Hardy J, Zetterberg H. Neurological consequences of traumatic brain injuries in sports. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2015;66:114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mez J, Daneshvar H, Kiernan T, et al. Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of American football. JAMA. 2017;318:360–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:709–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tagge C, Fisher A, Minaeva O, et al. Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model. Brain. 2018;141:422–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mrozek S, Vardon F, Geeraerts T. Brain temperature: physiology and pathophysiology after brain injury. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:989487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cairns CJ, Andrews PJ. Management of hyperthermia in traumatic brain injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8:106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thompson HJ, Tkacs NC, Saatman KE, Raghupathi R, McIntosh TK. Hyperthermia following traumatic brain injury: a critical evaluation. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;12:163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ma H, Sinha B, Pandya RS, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia as a neuroprotective strategy in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and traumatic brain injury. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:1282–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shaefi S, Mittel A, Hyam J, et al. Hypothermia for severe traumatic brain injury in adults: recent lessons from randomized controlled trials. Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Katzenberger R, Loewen C, Wassermann D, Petersen AJ, Ganetzky B, Wassarman DA. A Drosophila model of closed head traumatic brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4152–4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barekat A, Gonzalez A, Mauntz E, et al. Using Drosophila as an integrated model to study mild repetitive traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lessing D, Bonini NM. Maintaining the brain: insight into human neurodegeneration from Drosophila melanogaster mutants. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kahsai L, Zars T. Learning and memory in Drosophila: behavior, genetics, and neural systems. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;99:139–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bushey D, Cirelli C. From genetics to structure to function: exploring sleep in Drosophila. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;99:213–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dillon ME, Wang G, Garrity PA, Huey RB. Review: thermal preference in Drosophila. J Therm Biol. 2009;34:109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodriguez EC, Robertson RM. Protective effect of hypothermia on brain potassium homeostasis during repetitive anoxia in Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 2012;215:4157–4165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baxter SL, Allard DE, Crowl C, Sherwood NT. Cold temperature improves mobility and survival in Drosophila models of autosomal-dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia (AD-HSP). Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:1005–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neckameyer W, Bhatt P. Drosophila: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology. Dahmann C, ed. 2016. Vol 1478 New York, NY: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ali O, Escala W, Ruan K, Zhai G. Assaying locomotor, learning, and memory deficits in Drosophila models of neurodegeneration. J Vis Exp. 2011;11:2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1574–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]