Abstract

Objectives:

This cross-sectional study described how school-age children with cancer represent their symptoms and their associated characteristics using draw-and-tell interviews.

Participants and Setting:

Twenty-seven children 6 to 12 years of age (mean 9.16 years; SD 1.9) receiving treatment for cancer at the Cancer Transplant Center of a tertiary pediatric hospital in the Intermountain West of the United States.

Methodologic Approach:

Children participated in draw-and-tell interviews while completing drawings depicting days that they felt well and days that they felt sick. Children’s drawings and accompanying explanations were analyzed qualitatively.

Findings:

Children’s drawings related both symptoms and the strategies children use to self-manage their symptoms. Nausea, fatigue, pain, and sadness were the most frequently reported symptoms. Strategies to manage symptoms most often included physical care strategies and psychosocial care strategies.

Implications for Nursing:

Children with cancer are able to relate detailed descriptions of their symptoms and symptom self-management strategies when presented with developmentally sensitive approaches. Children’s drawings also provided important insights into the context of their symptom experiences and the consequences of symptoms on their day-to-day lives. Nurses and other healthcare team members are well-positioned to integrate arts-based approaches to symptom assessment and to support children in implementing their preferred strategies to alleviate symptoms.

Introduction and Background

Over 10,000 children less than 15 years of age are diagnosed with cancer in the United States each year (American Cancer Society, 2016). These children are developmentally diverse – ranging from pre-verbal infants to young adolescents with the capacity to think abstractly. Children’s developmental abilities also influence the manner in which they articulate and respond to their symptoms (Linder, 2008). Although children as young as four years of age are recognized as being capable of providing self-report about their symptoms, resources to support children in relating their symptom experiences are limited.

Elementary school-age children, those 6 to 12 years of age, are developing the ability to represent events mentally and symbolically. Maturing reasoning abilities allow children to form relationships between things and ideas as well as to think through actions and anticipated consequences (Rodgers, 2011). School-age children tend to rely on internal, sensory cues for recalling and communication, including reports of health- and illness-related information. The majority of resources for eliciting children’s self-report, including self-report of symptoms, are based on adult versions of tools that rely on external, verbal cues. Additionally, these self-report tools provide limited opportunity to explore children’s perspectives of the context in which type are experiencing symptoms and the meanings they attach to their symptoms. Alternative approaches to obtain an understanding of children’s experiences to inform clinical interventions are needed.

Symptoms in Children with Cancer

Challenges in understanding children’s symptom experiences are evident in both qualitative and quantitative studies. Many of these studies have included relatively small sample sizes of both children and adolescents, limiting the opportunity to delineate experiences and perspectives of younger children from those of adolescents.

Qualitative interviews have allowed children as young as four years of age to relate their cancer experiences (Woodgate & Degner 2003). Children frequently described the presence of multiple symptoms as, “I feel really weird,” or, “I feel sore and hurting,” (Woodgate, 2008). Such descriptions, which align with children’s developmental abilities, may be difficult for health care providers, and even parents, to interpret. Younger children also related frustration with multiple quantitative rating scales. Allowing children to relate their symptoms within the larger experience of cancer facilitated greater understanding of the meaning children attached to their symptoms (Woodgate, Degner, & Yanofsky, 2003).

Quantitative studies involving self-report scales also limit a full understanding of the child’s experience, particularly that of children less than ten years of age. While validated tools for assessing fatigue (Hockenberry et al., 2003; Hinds et al., 2010), nausea (Dupuis, Taddio, Kerr, Kelly, & MacKeigan, 2006), and pain (von Baeyer, 2006) are available for children as young as seven years of age, multi-symptom assessment scales are limited.

The 9-item Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) 7–12 (Collins et al., 2002) has facilitated the recruitment of younger children. Children and adolescents using this scale, however, report fewer symptoms (Linder, Al-Qaaydeh, & Donaldson. 2017; Walker, Gedaly-Duff, Miaskowski, & Nail, 2010) than those using more extensive multi-symptom scales (Baggott, et al., 2010; Miller, Jacob, & Hockenberry, 2011; Williams et al., 2012). Regardless of the scale used, however, the most frequently reported symptoms included nausea, fatigue, pain, and changes in appetite. Of note, Linder, Al-Qaaydeh, and Donaldson found that nearly one third of participants reported a response to the item, “Did anything else make you feel bad or sick?” on at least one occasion during a 3-day data collection period. Responses were varied and included psychosocial aspects of hospitalization, the hospital environment, physical symptoms, and aspects of physical care and treatment. These “other” symptoms were among the top 5 most severe and most distressing symptoms, highlighting the importance of providing developmentally meaningful mechanisms for children to communicate aspects of the symptom experience that are of priority to them.

Symptom Self-Management

Self-management is a dynamic, iterative process by which individuals with chronic illness integrate strategies that allow them to cope with their illness and its symptoms in the context of their day-to-day lives (Miller, Lasiter, Ellis, & Buelow, 2015). Self-management requires individuals to evaluate their health status and then implement interventions. The changing nature of children’s symptoms further adds to the challenge of self-management. Coping, a related aspect of illness and symptom experiences, emphasizes internal management, including both thoughts and behaviors individuals use to respond to stressors (Audulv, Packer, Hutchinson, Roger, & Kephart, 2016).

Symptom self-management strategies reported by children themselves include sleep, both for rest and to provide a mental reprieve, and taking medicine (Woodgate & Degner, 2003). School-age children reported more frequent use of active coping strategies, including distraction, emotional regulation, and problem solving rather than passive strategies to manage chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (Rodgers, et al., 2012). Active strategies were also perceived as more effective. In contrast, passive strategies, such as avoidant or emotion-focused strategies may support coping with medical procedures (Aldridge & Roesch, 2007). More research is needed to understand the context in which children use specific strategies as well as long term outcomes.

Arts-Based Approaches

Arts-based approaches, including drawing, provide an alternative to traditional paper-and-pencil-based tools and support recall of information in a developmentally meaningful manner (Driessnack & Furukawa, 2012). Drawing-based approaches with children have been widely used in research and clinical settings by psychology and child life professionals (Gross & Hayne, 1998; Malchiodi, 1998). Drawing supports not only children’s description of the experience, but also their larger interpretation and explanation of the context in which the experience is occurring. Children with sickle cell disease and asthma have used drawings to communicate their symptoms (Gabriels, Wamboldt, McCormick, Adams, & McTaggart, 2000; Stefanatou & Bowler, 1997). Children’s drawings have also demonstrated sensitivity to change over time in relating headache symptoms (Stafstrom, Goldenholz, & Dulli, 2005). More recently, drawing-based approaches have been used with children with cancer to explore existential challenges during treatment (Woodgate, West, & Tailor, 2014) and to reduce anxiety during hospitalization (Altay, Kilicarslan-Toruner, & Sari, 2017).

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to describe how school-age children with cancer perceive and represent their symptoms and their associated characteristics using an arts-based approach, draw-and-tell interviews. The study was grounded in a developmental science framework that recognizes a continuous interaction of multiple aspects of the individual’s development e.g. biologic, physiologic, behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and perceptual in the context of his or her environment (Magnussun, 2000; Miles & Holditch-Davis, 2003). As the study proceeded, the study team found that many children not only related their symptoms but also depicted the strategies they used to manage their symptoms. This paper presents both a description of symptoms and symptom self-management strategies as reported by school-age children receiving treatment for cancer using draw-and-tell interviews, an arts-based approach to understanding the children’s experiences (Driessnack, 2006).

Methods

Design

This cross-sectional, exploratory, descriptive study used participatory methods guided by the contextual inquiry phase of the cooperative inquiry process (Druin, 1999). Results of this study are part of a larger study that is engaging school-age children with cancer and pediatric oncology healthcare providers in the co-design of a mobile technology-based resource for symptom assessment. The cooperative inquiry process engages users as participants in the design process. The first phase of the cooperative inquiry process is contextual inquiry, which is grounded in field research and supports active participation of research participants throughout the study process. This phase also emphasizes the role of the research team in observing and analyzing participants’ responses and patterns of activity.

Sample and Setting

Participants were recruited from the inpatient oncology unit and ambulatory oncology clinic which are part of the Cancer Transplant Center of a tertiary free-standing children’s hospital in the Intermountain West of the United States. Eligible children were between 6 to 12 years of age and receiving treatment for cancer. Children receiving treatment for either a primary diagnosis of cancer or relapsed/refractory disease were eligible. Children were required to speak and understand English and be physically and cognitively capable of completing study-related activities. Children with major cognitive developmental disabilities were excluded. Because the study was exploratory in its scope, children were heterogeneous with regards to diagnosis and stage of treatment.

Procedure

Recruitment and enrollment.

Institutional review board approval was granted. Participants were recruited between March 2015 and January 2016. Eligible patients and families were initially approached by an oncology team member to elicit interest in the study. A research team member then met with families to explain study procedures. Written parental permission was obtained for all participants. Children 7–12 years of age provided written assent; children 6 years of age provided verbal assent.

Demographic and clinical data.

Research team members reviewed the medical record of enrolled participants to identify demographic and clinical data to describe the study sample.

Draw-and-tell interviews.

The draw-and-tell interview is a developmentally sensitive approach to data collection (Driessnack, 2006). This approach emphasizes not just the drawing, but what the child says about the drawing. By drawing first and then relating their accompanying explanations, this process fosters children’s recall and communication of their experiences which supports a greater understanding of the child’s associated interpretation and meaning, including the context of the experience, that can not be obtained from interviews or traditional quantitative measures (Butler, Gross, & Hayne, 1995; Gross, Hayne, & Drury, 2008).

Participants participated in draw-and-tell interviews during the course of a scheduled ambulatory clinic visit or inpatient admission. Children received a packet of art supplies including a sketch tablet, crayons, colored pencils, markers, pencils, and stickers which they kept at the conclusion of the interview. Parents were allowed to remain with the child during the interviews. Parents’ presence did not interfere with study-related activities.

Participants provided pictures of themselves to relate days that they were feeling well as well as days when they were feeling sick. As they completed their pictures, research team members used a semi-structured interview guide to facilitate participant’s explanation of their pictures and to record detailed notes of the interview. Participants were first asked to explain each picture. Specific attention was given to commonly reported symptoms based on published literature while allowing participants to relate other symptoms that were of priority to them. Research team members also asked follow up clarifying questions based on participants’ responses to validate understanding of the child’s response and to clarify the meaning of the language a child used in describing a given symptom or feeling associated with that symptom. For example, one participant was able to further articulate that the expression that his “tummy feels sick” could relate to either pain or nausea; whereas other children were not able to further describe expressions of “stomach ache.”

With the exception of one participant, children completed study-related activities without difficulty during the course of a routinely scheduled ambulatory clinic visit or afternoon of a scheduled inpatient admission. Because of progressive tiredness during the course of the clinic visit, one participant provided only brief explanations of her drawings.

Data Management

Demographic and clinical data were entered electronically using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at the University of Utah (Harris et al., 2009). Data were then exported into SPSS for analysis. Qualitative data were organized into Excel and SPSS files to support descriptive summaries and content analysis procedures.

Analysis Procedures

Demographic and clinical data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Symptoms and self-management strategies also summarized descriptively. Independent samples t-tests explored differences in the number of reported symptoms and self-management strategies based on gender as well as younger (6–8 years) vs. older (9–12 years) children.

Qualitative content analysis procedures were used to organize symptoms and self-management strategies into common categories and themes (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Participants’ drawings as well as the accompanying interview notes were reviewed independently by at least two research team members to identify symptoms and symptom self-management strategies reported by each child. Pictures depicting days when children were feeling well as well as those depicting days when children were feeling sick were reviewed. Team members then met together to resolve discrepancies. Symptoms and self-management strategies that were depicted in participants’ drawings as well as those that the children related as part of their responses in addition to their drawings were included.

A coding scheme was developed to organize reported symptoms into categories using both participants’ expressions and associated explanations of their symptoms. For example, the expression “feeling tired” was categorized as “fatigue;” and “feeling queasy” was categorized as “nausea.” Categories were then organized into subthemes and then themes. This analytic process was also applied to participants’ self-management strategies. Participants’ drawings and accompanying explanations were further examined with regards to the context in which symptoms were occurring and the impact of symptoms on their day-to-day lives.

Results

Participants

Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The study sample included 27 children (52% male) receiving treatment for cancer. Participants were a mean of 9.16 years of age (SD=1.9; range 6.33 – 12.83 years) and were a median of 9 months from their initial diagnosis of cancer (range 1–93 months). The accrual rate for the study was 90% with three children declining to participate. Reasons for non-participation included “don’t feel like it” and “really don’t want to.”

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics

| Gender | n | % | |

| Male | 14 | 52% | |

| Female | 13 | 48% | |

| Age Group | |||

| Younger children (6–8 years) | 14 | 52% | |

| Older children (9–12 years) | 13 | 48% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White/non-Hispanic | 25 | 93% | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 | 4% | |

| Black/African American | 1 | 4% | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 15 | 57% | |

| Other acute leukemia | 1 | 4% | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 | 4% | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 | 4% | |

| Brain tumor | 2 | 7% | |

| Sarcoma | 5 | 19% | |

| Other solid tumor | 2 | 7% | |

| Disease stage | |||

| Primary disease | 26 | 96% | |

| Recurrent disease | 1 | 4% |

Symptoms

Table 2 summarizes symptoms reported by children through their drawings and accompanying explanations. This table also presents the reported frequencies of each symptom category and their organization of into subthemes.

Table 2.

Symptoms

| N=27 Children | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Physical Symptoms | ||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | ||

| Nausea | 15 | 56 |

| Stomach ache | 9 | 33 |

| Vomiting | 6 | 22 |

| General illness symptoms | ||

| Fatigue | 11 | 41 |

| Feeling “sick” / “yucky” | 7 | 26 |

| ”Eyes look tired” | 2 | 7 |

| Coughing | 1 | 4 |

| Fever | 1 | 4 |

| Runny nose | 1 | 4 |

| Pain-related symptoms | ||

| Pain | 8 | 30 |

| Headaches | 5 | 19 |

| Appetite/Eating-related symptoms | ||

| Not feeling like eating | 4 | 15 |

| Changes in taste | 2 | 7 |

| Appetite changes | 1 | 4 |

| Sleep-related symptoms | ||

| Sleeping more/need to take naps | 2 | 7 |

| Difficulty sleeping | 1 | 4 |

| Feeling sleepy/drowsy | 1 | 4 |

| Neuromuscular symptoms | ||

| Difficulty with balance | 1 | 4 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 4 |

| Numbness in feet | 1 | 4 |

| Weakness in one part of the body | 1 | 4 |

| Skin symptoms | ||

| Itching | 2 | 7 |

| Bruising | 1 | 4 |

| Scabbing on head | 1 | 4 |

| Sensory symptoms | ||

| Eye tearing/drainage | 1 | 4 |

| Hearing loss | 1 | 4 |

| Psychosocial Symptoms | ||

| Emotions | ||

| Sadness | 22 | 81 |

| Frustration/irritability/anger | 3 | 11 |

| Feeling scared | 2 | 7 |

| Mood changes (from steroids) | 2 | 7 |

| Embarrassment | 1 | 4 |

| Grief | 1 | 4 |

| Uncertainty | 1 | 4 |

| Sense of Isolation | ||

| Being away from family | 2 | 7 |

| Stuck in room | 1 | 4 |

| Self-esteem changes | ||

| Getting behind in school | 1 | 4 |

| Sense of feeling small | 1 | 4 |

Participants related a total of 26 different physical symptoms and 11 different psychosocial symptoms. Three children also related challenges with taking oral medications. Participants related a median of 4 symptoms (range 2–11). This included a median of 3 physical symptoms (range 1–7) and 1 psychosocial symptom (range 0–4). Independent samples t-tests did not identify differences in the total number of symptoms reported based on gender (t=−.73; p=.47). Likewise, the total number of symptoms reported by younger children (6–8 years) did not differ from the number reported by older children (9–12 years) (t=−.73; p=.47). The number of physical and psychosocial symptoms also did not differ based on gender or age group. Although all children included symptoms on their drawings depicting days that they were feeling sick, two girls included symptoms on their drawings of days they were feeling well.

Among physical symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, specifically nausea and “stomach ache” predominated followed by general illness symptoms, specifically fatigue and “feeling yucky.” Pain-related symptoms were reported by 12 children. Of note, the experience of headaches (n=5) was distinguished from other sources of pain. Appetite-related symptoms (n=7) and sleep-related symptoms (n=4) were also among the most common physical symptoms.

Emotions predominated as psychosocial symptoms with sadness (n=22) being most frequently depicted. Children’s pictures also depicted a sense of isolation (n=3) and self-esteem changes (n=2).

Symptom Self-Management Strategies

Twenty-two children (55% male; 50% younger children) related 21 different strategies (Table 3) that they used to manage their symptoms. These children related a median of three symptom self-management strategies (range 1–6). The number of reported strategies did not differ based on gender (t=−.33; p=.75) or age group (t=−.45; p=.66). All children described symptom self-management strategies related strategies specific to days when they were not feeling well; however, six children (four girls and two boys) also related symptom self-management strategies on the picture depicting when they were feeling well.

Table 3.

Symptom Self-Management Strategies

| N=22 Children Reporting Self-Management Strategies | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Theme: Physical Care Strategies | ||

| Subtheme: Energy/Activity Management | ||

| Lying down/resting | 11 | 50 |

| Sleeping | 3 | 14 |

| Moving/taking walks | 1 | 5 |

| Subtheme: Personal Comfort Strategies | ||

| Use of blankets | 6 | 27 |

| Food/Drink Item | 4 | 18 |

| Baths/showers | 2 | 9 |

| Use of pillows | 2 | 9 |

| Positioning for comfort | 1 | 5 |

| Subtheme: Positioning Near Resources | ||

| Emesis bag close | 2 | 9 |

| Being close to bathroom | 1 | 5 |

| Sleeping in new area | 1 | 5 |

| Theme: Psychosocial Care Strategies | ||

| Subtheme: Distractions | ||

| Arts/crafts | 4 | 18 |

| Reading (or being read to) | 2 | 9 |

| Games | 1 | 5 |

| Subtheme: Personalizing/Normalizing | ||

| Arranging hospital room like home | 3 | 14 |

| Stuffed animals | 3 | 14 |

| Wearing hat/scarf | 1 | 5 |

| Subtheme: Interpersonal/Relational Strategies | ||

| Support person | 4 | 18 |

| Being alone | 2 | 9 |

| Theme: Medication Related | ||

| Medicines | 4 | 18 |

| Personal strategy for taking meds | 2 | 9 |

Children’s symptom self-management strategies were further organized into six subthemes and three themes. Themes included physical care strategies, psychosocial care strategies, and medication-related strategies. Physical care strategies predominated with efforts to manage their energy balance (n=15) and personal comfort strategies (n=15) most often depicted. Lying down and resting was the most frequently reported strategy overall (n=11). The most frequently depicted psychosocial care strategies included children’s use of distractions (n=7) and their efforts to personalize and normalize their situation (n=7). Medication related strategies included not only taking a given medication to help relieve a symptom (n=4) but also children’s specific strategies for taking their medications (n=2).

Depiction of Symptoms and Symptom Self-Management Strategies

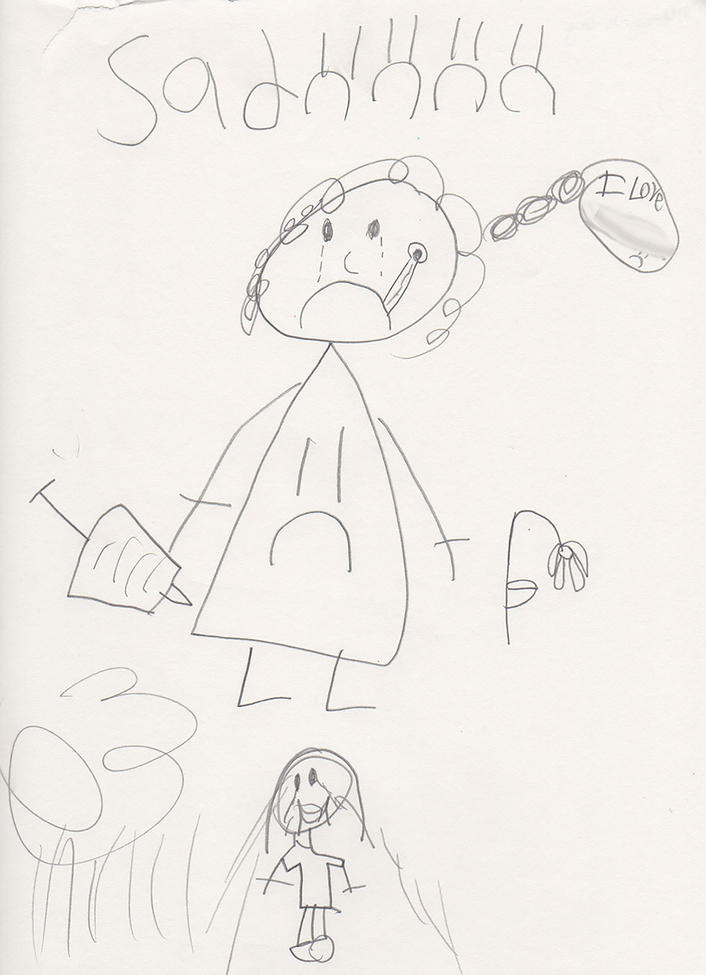

Children’s drawings illustrated the complexity of the symptom experience and the experience of multiple physical and psychosocial symptoms. Their drawings also illustrated the common, yet very personal, experiences of children receiving treatment for cancer. A 7-year-old girl with leukemia illustrated the experience of stomach ache, fevers, and procedural pain associated with asparaginase injections. Her profound sadness at separation from her younger sister as well as the grief in response to a friend’s death from leukemia also affected the flowers in her environment (Figure 1)

Figure 1:

7-year-old girl who is sad because she is separated from her sister and is grieving a friend who died of leukemia. This child is also running a fever, has a “sick tummy,” and is experiencing pain from an injection.

Children frequently depicted their symptoms and the strategies they used to manage their symptoms in the context of how symptoms impacted their day-to-day lives. Even if children did not name a specific self-management strategy, their drawings of days when they were feeling sick frequently depicted themselves as lying down or reclining, feeling sad, and not being able go engage in their usual activities. A 7-year-old boy with leukemia related, “feeling sad because I’m not at home, feeling sick, have to take pills, lots of pills,” and being … “stuck in my room for days,” about his symptom experience associated with getting methotrexate in the inpatient setting. On days when he feels sick, an 8-year-old boy with leukemia related feeling “sad and droopy” and “[I] don’t like it.” He related having “no energy,” feeling “tired,” and that his “head hurts” which cause him to “stay in bed” or “lie down on the couch with a blanket.” Other children depicted the need to position themselves near a bathroom or to keep an emesis bag within reach.

Some children depicted how their self-management strategies helped them engage in normalizing activities or even to prevent symptoms. An 8-year-old girl with a liver tumor depicted how support from a hospital volunteer helped her manage the consequences of her cisplatin-induced hearing loss (Figure 2). On days when Hospital Bingo was broadcast over the hospital’s closed circuit television system, the volunteer would come to her room to repeat the words that had been spoken. He also would call in jokes (an activity that is part of Hospital Bingo) on her behalf so that she could fully participate as any other child in the hospital.

Figure 2:

8-year-old girl who has experienced cisplatin-induced hearing loss. A hospital volunteer comes to play Hospital Bingo with her to relate what is being said through the closed circuit TV and to call in her jokes.

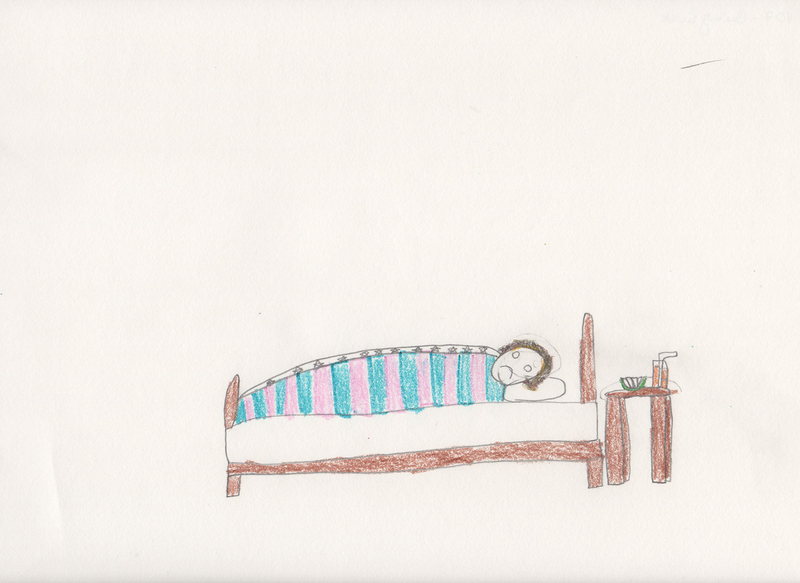

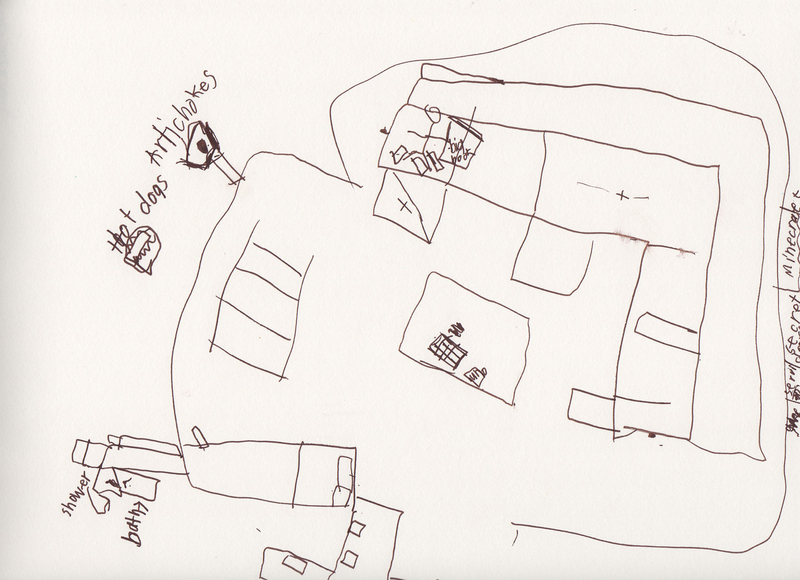

Many children very deliberate and detailed in drawing and describing their symptom self-management strategies. A 7-year-old girl with leukemia’s picture included the two blankets she placed over herself when lying in bed as well as the bowl of crackers on her nightstand and the glass of apple juice with a straw in it to help manage her nausea and not feeling like eating (Figure 3). A 7-year-old boy with Wilms tumor was very detailed in depicting the multiple glasses of water he needed in order to take his syringe of “sulfa/trim” (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) and the nausea he experienced when taking this medication. (Figure 4). A 10-year-old boy with leukemia depicted himself in his family room, which was laid out much like a map with different self-management strategies accessible to him. These included a “big book” that has a lot of things he can think about when he is sad, propping his hurting leg on pillows while reclining on the couch, the accessibility of favorite games on the coffee table, and a shower to help him feel better. He added that he likes steamed artichokes and hotdogs but that “sometimes I don’t like to eat if my stomach feels sick,” (Figure 5).

Figure 3:

7-year-old girl who has two specific blankets placed over her as she rests in bed because she feels queasy and doesn’t want to eat. She has a bowl of crackers and a glass of apple juice with a straw in it within reach.

Figure 4:

7-year-old boy who feels like he is “gonna puke” when he has to take his “sulfa/trim” (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim). His mother is standing by. The syringe with the medication and a glass of water are on the table.

Figure 5:

10-year-old boy who is resting on the couch at home with his leg propped up with pillows for comfort. He is reading a “big book” to keep his mind off feeling sick. Some games that serve as a distraction are on the coffee table. Showers and baths also help him feel better. His favorite comfort foods are hot dogs and artichokes.

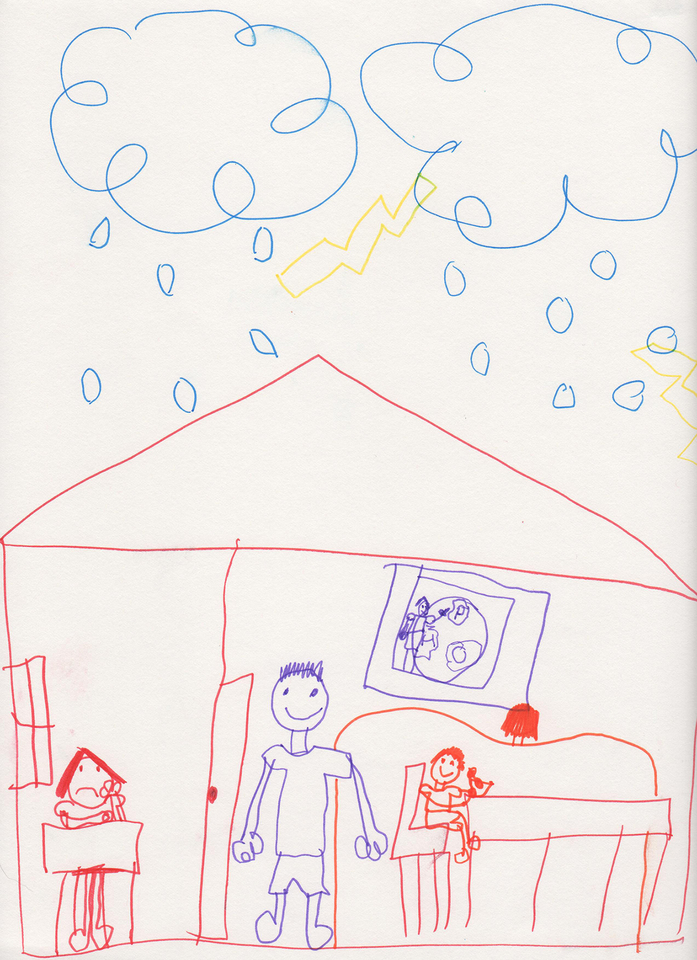

Some children’s depictions of their symptom experiences reflected the consequences on others, including family members. An 8-year-old girl with leukemia depicted her mother as the gatekeeper of information (Figure 6). She depicted herself as separate from her family, waiting for her mother to obtain information to relay information to her about what to expect for the day.

Figure 6:

8-year-old girl experiencing uncertainty in relation to the day. She is separate from her family who are in another room. Her mother is watching the weather to determine what the day will be like.

Children’s responses also related preferences for rating symptom severity and the meaning attached to their ratings. For example, an 8-year-old girl with a liver tumor related her frustration with numeric ratings and preferred that she be allowed to “just say low, medium, or high.” For her, “low” meant to allow her to be left alone, whereas, “medium” or “high” meant that she needed an intervention. In contrast, a 10-year-old boy with osteosarcoma preferred a numeric rating scale with the capacity to personalize the scale to accommodate decimal points.

Discussion

Results of this study demonstrate the role of a developmentally sensitive arts-based approach – the draw-and-tell interview – to support children in relating rich personal data about their symptoms and symptom self-management strategies. When symptoms are approached solely as side effects, children often provide minimal description (Woodgate, 2003). Using drawings allowed children’s symptom experiences to be approached as multidimensional experiences. This child-centric approach allowed a greater understanding of children’s perspectives and the context in which they experienced and managed their symptoms.

Both younger and older children of both genders were able to articulate symptoms. Children’s depictions of their symptoms included not just the symptoms themselves, but also the larger context in which children experienced them, including the strategies they used to manage their symptoms and the consequences of symptoms on their day-to-day lives. Anecdotally, several parents reported learning insights into their child’s experiences by listening to the draw-and-tell interviews.

Similar to previous studies including school-age children, the most frequently reported symptoms were nausea, fatigue, pain, and sadness (Baggott, et al., 2010; Linder, Al-Qaaydeh, & Donaldson, 2017; Miller, Jacob, & Hockenberry, 2011; Walker et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2012). This study also highlighted the importance of the capacity to assess for other less-frequently occurring symptoms that may be of greater importance to the child, such as hearing loss, that are not included on many multi-symptom assessment scales (Collins et al., 2000; Collins et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2012). Study results also emphasize ongoing symptom assessment challenges with some children using terms such as “stomach ache,” and feeling “sick” or “yucky” to describe symptoms which can limit clinicians’ ability to discern individual symptoms (Woodgate, 2008).

Participants’ pictures and accompanying explanations provided insight into different aspects of commonly reported symptoms. For example, sleep-related symptoms included sleeping more during the day, difficulty sleeping at night, and increased sleepiness/drowsiness. Appetite and eating-related symptoms included a sense of not feeling like eating, changes in taste, and changes in appetite.

This study also emphasized the strategies that children initiate to manage their symptoms. Participants’ symptom self-management strategies emerged within their drawings and accompanying explanations without prompts to relate them. Although symptom self-management strategies were most frequently depicted on days when the child was feeling sick, children also related strategies they used on days when they were feeling well both to prevent symptoms and to cope with the consequences of chronic symptoms. Symptom self-management strategies not only promoted children’s comfort but also supported them in being able to engage in desired activities, such as participating in Hospital Bingo.

Developmental similarities across age groups were also noted in children’s self-management strategies. Similar to adolescents and young adults (AYAs) receiving chemotherapy, children reported both physical care and psychosocial care strategies (Linder et al., 2017) to manage their symptoms. Children most frequently related lying down and resting as a symptom management strategy, often with personal blankets or pillows arranged in a specific manner. Distractions, likewise, were related by both children and AYAs. Although medications were reported less frequently by children compared with AYAs, the importance of medications, as well as children’s individual strategies for taking medications should be recognized.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include a small cross-sectional, heterogeneous sample with limited racial and ethnic diversity from a single institution. Because the emphasis of the study was children’s depiction of their symptoms, they were not prompted to relate their symptom self-management strategies. Other children may have provided information about their self-management strategies if prompted to do so. This study also did not seek to identify strategies in response to specific symptoms. Additionally, this study did not assess children’s symptoms at a given point in time, but asked them to recall their perspectives of days when they were feeling well and days when they were feeling sick.

Directions for Future Research

The scope of symptoms illustrated through children’s drawings highlights limitations of existing resources for young children (e.g. short lists of common symptoms) to fully capture children’s symptom experiences. Areas for future research include the development and validation of child-centric resources that will support a more complete report from the child’s perspective. Incorporating arts-based approaches to complement traditional self-report measures may further support a richer, child-centric understanding of the child’s experience.

Additional research is needed to explore the self-management strategies children use in response to specific symptoms and their perceived effectiveness of these strategies. Research comparing similarities and differences among symptom self-management strategies used by individuals with cancer across the lifespan is also needed. Results of this study provide initial guidance for intervention-based studies that incorporate children’s preferred symptom self-management strategies.

Implications for Nursing

Results of this study demonstrate the importance of using child-centric approaches to support children in relating rich personal data about their symptoms and symptom self-management strategies. Children as young as six years of age were able to relate their symptoms and self-management strategies and to illustrate the impact of their symptoms on their day-to-day lives. Incorporating arts-based approaches within the healthcare system may augment existing approaches to symptom assessment and may support a more comprehensive understanding of the child’s perspective, particularly with regards to less frequently reported symptoms. The addition of arts-based approaches to complement traditional measures may further serve to enhance nurse-patient communication, resulting in more personalized symptom management.

Study results also emphasize the ongoing significance of nausea and fatigue and the need for effective strategies to alleviate these symptoms. Although the evidence base for effective symptom management strategies for children is limited, nurses need to be aware of children’s capacity to implement personalized symptom self-management strategies, many of which can be easily implemented in the clinical care setting. Integrating children’s preferred self-management strategies into the plan of care has the potential to result in more effective symptom management. Nurses can also support children’s symptom self-management by suggesting strategies that have been endorsed by other children.

Conclusion

Children’s symptoms and the strategies they use to self-manage their symptoms reflect both common, shared experiences as well as ones that are distinct and individual. Arts-based approaches can support nurses in gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the child’s symptoms by supporting the child’s ability to recall experiences and their associated meaning on his or her day-to-day life. Children also are able to identify and implement meaningful symptom self-management strategies that can be incorporated in the child’s plan of care.

Knowledge Translation:

Arts-based techniques support children’s recall and depiction of symptoms.

Currently available resources for symptom assessment in young children are unlikely to fully capture their symptom experiences.

Children as young as six years of age are able to identify and initiate symptom self-management strategies.

Funding acknowledgment:

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research: 1K23NR014874-01 The research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Lauri A. Linder, Associate Professor, University of Utah College of Nursing and Clinical Nurse Specialist, Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT.

Heather Bratton, University of Utah College of Nursing, Salt Lake City, UT.

Anna Nguyen, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT.

Kori Parker, University of Utah Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT.

Sarah Wawrzynski, PhD Student, University of Utah College of Nursing and Staff Nurse, Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT.

References

- Aldridge AA, & Roesch SC (2007). Coping and adjustment in children with cancer: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30, 115–129. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9087-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altay N, Kilicarslan-Toruner E, & Sari C (2017) The effect of drawing and writing technique on the anxiety level of children undergoing cancer treatment. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 28, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society (2016). Cancer facts & figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Audulv A, Packer T, Hutchinson S, Roger KS, & Kephart G (2016). Coping, adapting, or self-managing – what is the difference? A concept review based on the neurological literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72, 2629–2643. doi: 10.1111/jan.13037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggott C, Dodd M, Kennedy C, Marina N, Matthay KK, Cooper BA, & Miaskowski C (2010). Changes in children’s reports of symptom occurrence and severity during a course of myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 27, 307–315. doi: 10.1177/1043454210377619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler S, Gross J, Hayne H, (1995). The effect of drawing on memory performance in young children. Developmental Psychology, 31, 597–608. [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, Byrnes ME, Dunkel IJ, Lapin J, Nadel T, Thaler HT, … Portenoy RK, (2000). The measurement of symptoms in children with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 19, 363–377. doi: S0885-3924(00)00127-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, Devine TD, Dick GS, Johnson EA, Kilham HA, Pinkerton CR, … Portenoy RK, (2002). The measurement of symptoms in young children with cancer: The validation of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale in children aged 7–12. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 23, 10–16. doi: S088539240100375X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessnack M (2006). Draw-and-tell conversations with children about fear. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 1414–1435. doi: 10.1177/1049732306294127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessnack M, Furukawa R (2012). Arts-based data collection techniques used in child research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 17, 3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.17446155.2011.00304.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druin A (1999). Cooperative inquiry: Developing new technologies for children with children. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems: the CHI is the limit (pp. 592–599). Association for Computing Machinery; Accessed at: http://hcil2.cs.umd.edu/trs/99-14/99-14.html [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis LL, Taddio A, Kerr EN, Kelly A, & MacKeigan L (2006). Development and validation of the pediatric nausea assessment tool for use in children receiving antineoplastic agents. Pharmacotherapy, 26, 1221–1231. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.9.1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, & Kyngäs H (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, & Hayne H (1998). Drawing facilitates children’s verbal reports of emotionally laden events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 4, 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Hayne H, & Drury T (2008). Drawing facilitates children’s reports of factual and narrative information: Implications for educational contexts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 953–971. doi: 10.1002/acp.1518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42, 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds PS, Yang J, Gattuso JS, Hockenberry M, Jones H, Zupanec S, … Srivastava DK, (2010). Psychometric and Clinical Assessment of the 10-item Reduced Version of the Fatigue Scale –Child Instrument. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 39, 572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenberry MJ, Hinds PS, Barrera P, Bryant R, Adams-McNeill J, Hooke C, …, Manteuffel B (2003). Three instruments to assess fatigue in children with cancer: the child, parent and staff perspectives. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 25, 319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00680-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder LA (2008). Developmental diversity in symptom research involving children and adolescents with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 23, 296–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder LA, Al-Qaaydeh S, & Donaldson G (2017). Symptom characteristics among hospitalized children and adolescents with cancer. Cancer Nursing, epub ahead of print January 20, 2017. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder LA, Erickson JM, Stegenga K, Macpherson CF, Wawrzynski S, Wilson C, Ameringer S (2017). Symptom self-management strategies reported by adolescents and young adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Journal of Supportive Care in Cancer epub ahead of print July 17, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3811-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnussun D (2000). The individual as the organizing principle In L. R. Bergman, R. B. Cairns, L. G. Nillson, & L. Nystedt (Eds.), Developmental science and the holistic approach (pp.33–47). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi CA (1998). Understanding children’s drawings. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MS, & Holditch-Davis D (2003). Enhancing nursing research with children and families using a developmental perspective In Miles MS & Holditch-Davis D (Eds.), Annual review of nursing research (pp. 1–22). New York: Springer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Jacob E, & Hockenberry MJ (2011). Nausea, pain, fatigue, and multiple symptoms in hospitalized children with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38, E382–E393. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E382-E393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Lasiter S, Ellis RB, Buelow JM (2015). Chronic disease self-management: A hybrid concept analysis. Nursing Outlook, 63, 154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers CC (2011). Health promotion of the school-age child and family In M. J. Hockenberry & D. Wilson (Eds.), Wong’s Nursing care of infants and children 9th ed. (pp. 645–683). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers C, Norville R, Taylor O, Poon C, Hesselgrave J, Gregurich MA, & Hockenberry MJ (2012). Children’s coping strategies for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, 202–209. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.202-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE, Goldenholz SR, & Dulli DA (2005). Serial headache drawings by children with migraine: correlation with clinical headache status. Journal of Child Neurology, 20, 809–813. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200100501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanatou A, & Bowler D (1997). Depiction of pain in the self-drawings of children with sickle cell disease. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 23, 135–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Baeyer CL (2006). Children’s self-reports of pain intensity: Scale selection, limitations and interpretation. Pain Research and Management, 11, 157–162. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AJ, Gedaly-Duff V, Miaskowski C, & Nail L (2010). Differences in symptom occurrence, frequency, intensity, and distress in adolescents prior to and one week after the administration of chemotherapy. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 27, 259–265. doi: 10.1177/1043454210365150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PD, Williams AR, Kelly KP, Dobos C, Gieseking A, Connor R, … Del Favero D. (2012). A symptom checklist for children with cancer: The Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist-Children. Cancer Nursing, 35, 89–98. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31821a51f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL (2008). Feeling states: A new approach to understand how children and adolescents with cancer experience symptoms. Cancer Nursing, 31, 229–238. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL, & Degner LF (2003). Expectations and beliefs about children’s cancer symptoms: Perspectives of children with cancer and their families. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30, 479–491. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.479-491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL, Degner LF, & Yanofsky R (2003). A different perspective to approaching cancer symptoms in children. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 26, 800–817. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00285-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL, West CH, & Tailor K (2014). Existential anxiety and growth: An exploration of computerized drawings and perspectives of children and adolescents with cancer. Cancer Nursing, 37, 146–159. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31829ded29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]