Abstract

Introduction:

It has been almost fifty years since the Towne strain was used by Plotkin and collaborators as the first vaccine candidate for cytomegalovirus (CMV). While that approach showed partial efficacy, there have been a multitude of challenges to improve on the promise of a CMV vaccine. Efforts have been dichotomized into a therapeutic vaccine for patients with CMV-infected allografts, either stem cells or solid organ, and a prophylactic vaccine for congenital infection.

Areas Covered:

This review will evaluate research prospects for a therapeutic vaccine for transplant recipients that recognizes CMV utilizing primarily T cell responses. Similarly, we will provide an extensive discussion on attempts to develop a vaccine to prevent the manifestations of congenital infection, based on eliciting a humoral anti-CMV protective response. The review will also describe newer developments that have upended the efforts towards such a vaccine through the discovery of a second pathway of CMV infection that utilizes an alternative receptor for entry using a series of antigens that have been determined to be important for prevention of infection.

Expert Commentary:

There is a concerted effort to unify separate therapeutic and prophylactic vaccine strategies into a single delivery agent that would be effective for both transplant-related and congenital infection.

Keywords: antivirals, cytomegalovirus, ganciclovir, immune response, letermovir, solid organ transplant, congenital infection, stem cell transplant, subunit vaccine, viral vector

1. Introduction

Vaccines against infectious pathogens have a long history of development as many were discovered in monumental efforts to address public health concerns. Examples include the Salk and Sabin vaccines against polio virus, the rubella vaccine, the mumps vaccine, the measles vaccine, and more recently the hepatitis B vaccine and the human papilloma virus vaccine. As is well known, there are childhood vaccinations against a myriad of bacterial and viral pathogens that have prevented countless deaths and abated suffering of children as well as adults. The road to each of these vaccines has been difficult, and those triumphs and disappointments have been detailed in other reviews. In the realm of herpesviruses, there have been more disappointments than triumphs, with only one virus, namely varicella zoster virus, the etiological agent for shingles for which any vaccine (Varivax, Zostervax, and Singrix) has been licensed by regulatory authorities worldwide. Yet, morbidity due to these pathogens is substantial, and, like the HIV vaccine attempts, the noteworthy failures in this field, including unsuccessful attempts in developing vaccines against herpes simplex virus and the topic of this review, cytomegalovirus offer a challenge.

Since the early days of the discovery of cytomegalovirus as a human pathogen and its involvement in a variety of pathogenic disease processes, there has been a steady effort in developing both a prophylactic and a therapeutic vaccine formulation. Since CMV has risen to be a scourge for transplant recipients and HIV/AIDS patients, as well as congenitally infected neonates, various alternative strategies have been developed to overcome the morbidity and in rarer cases, mortality resulting from end-organ disease (EOD) caused by CMV infection. These alternatives include primarily the various antivirals and their successful applications which have been detailed in multiple reviews. In this review, we will focus on describing efforts in a variety of disease settings to develop one or more CMV vaccine formulations that will be beneficial for either immunosuppressed adults or as a prophylactic for mothers of child-bearing age to prevent congenital infection. The field has exploded with intense research in a variety of areas and so we have endeavored to be as inclusive as possible with citations, but there are inevitable lapses in which not all contributions for development of a particular vaccine approach and its background setting were completely referenced for all contributors. We apologize for this in advance and hope there is an understanding that we endeavored to be as comprehensive as possible. We anticipate that one or more licensed vaccines will become available in the next five to ten years and we hope this review provides insight and guidance for the realization of a long-sought strategy to control or prevent CMV infection.

2. Prophylaxis for cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection prevention

CMV infection (viremia but no evidence of EOD) and disease can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in recipients of transplantation; solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell (HCT). This section will discuss the recent advances in prevention and control of CMV infection in the context of allogeneic HCT. (See Supplementary documents for “List of Terms,” prepared for the reader’s benefit.)

2.1. Historical perspective

Early after the introduction of allogeneic HCT, the importance of CMV was realized in causing disease, especially interstitial pneumonitis that carried very high mortality [1]. The quest for development of a prophylactic approach that would be safe and effective had remained elusive until recently [2] due to the toxicities associated with the currently available CMV antiviral agents, namely ganciclovir (marrow suppression)[3], foscarnet and cidofovir (both cause renal toxicity). That had led to the approach of pre-emptive therapy (PET) with ganciclovir or foscarnet to minimize risk of treatment in a broader population of allogeneic HCT patients. PET is dependent on the identification of viremia (currently polymerase chain reaction – PCR, is the standard of care) which in turn significantly depends on the sensitivity of the CMV assay used. This limits establishing a universal CMV viral load that could be used to initiate PET. World health organization (WHO) has made recommendations to use international units per ml (IU/ml) however that has not eliminated the issue of the varying sensitivity of the different assays[4].

PET assisted early detection of CMV infection has resulted in the reduction of CMV disease burden, however, there continues to be a significant clinical and financial burden associated with infection[5,6]. Teira et al showed that R+/D- and R+/D+ had the highest rates of CMV infection and that CMV infection is associated with excess non-relapse mortality (NRM) compared to no reactivation[7]. In contrast to some studies that demonstrated reduced rate of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) relapse with CMV infection[8,9], a study by Teira et al confirmed that there is no benefit of CMV infection on prevention of relapse of disease in patients transplanted for AML. Meanwhile, Green et al showed that any level of viremia is associated with excess mortality and prompt PET positively impacted patient survival[10]. High incidence of infection has also been observed with Campath that is used for treatment of certain hematologic malignancies and as an adjunct with pre-transplant conditioning regimens [11]. Thus in the context of the available literature, the question is whether any degree of CMV infection is harmful, and how quickly should steps to prevent infection be instituted?[12]

2.2. Prophylaxis

Various groups have studied prophylaxis with different regimens of existing antivirals. In a randomized study, ganciclovir (GCV) compared to placebo was very effective in preventing CMV infection, however it resulted in higher mortality in the GCV group related to neutropenia and secondary infections[3]. The group at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center reported a significant reduction in CMV infection (not disease) with an intensive prophylaxis regimen using GCV from day −8 to day −2 of cord blood originated HCT and high dose valacyclovir post HCT[13]. The same group recently reported a modified intensity regimen, where the GCV component was dropped and similar CMV related outcomes were observed[14]. In addition, the group from MD Anderson Cancer Center showed a reduction in CMV infection in the first 100 days post-haploidentical HCT using a hybrid approach of valganciclovir pre-HCT followed by valacyclovir post HCT[15]. Besides the hybrid use of GCV and acyclovir, there have been 3 phase III clinical trials using newer, safer drugs that included maribavir, brincidofovir and most recently, letermovir.

2.3. New generation antivirals

Maribavir, an inhibitor of CMV UL97 mediated phosphorylation that blocks the egress of CMV virions from the nucleus, failed to meet its primary study endpoint[16], and it is postulated that the failure was a result of the study design and use of a lower dose of 100 mg twice daily as opposed to 400 mg, 800 mg, or 1200 mg twice a day in two phase 2 studies. [17]. One of the major concerns with this agent is the low barrier to development of resistance and a distortion of the sense of taste (dysguesia). Brincidofovir, a lipid conjugate of cidofovir and 3-hexadecyloxy-1-propanol, is an orally bioavailable and a non-nephrotoxic agent that has activity against a variety of DNA viruses. Although, it showed promise in a phase II trial by significantly reducing CMV related events compared to placebo[18], a phase III randomized clinical trial failed to show that benefit[19]. Major toxicity involved the gastrointestinal tract with diarrhea and abdominal cramps with a higher incidence of GVHD.

Letermovir, a 3, 4-dihydro-quinazoline-4-yl-acetic acid derivative, inhibits the viral “terminase” complex that is comprised of UL56/UL89. The terminase complex aids in the packaging of the CMV virion in the cytoplasm, and by inhibiting the cleavage of concatemeric DNA, letermovir prevents the development and release of infectious virions[20]. The most recent significant development has been the FDA approval of letermovir for prophylaxis to prevent CMV infection based on the results of a multi-center phase III clinical trial in CMV seropositive recipients of allogeneic HCT[21].

In this pivotal trial, letermovir was superior to placebo in the prevention of clinically significant CMV infections (defined as CMV infection that required PET). Patients were treated with letermovir 480 mg once daily (or 240 mg once daily in those who were also taking cyclosporine, CSA) and prophylactic treatment had to initiate anytime between day 0 and day 28 and continued through day 100 post HCT (negative test for CMV infection by PCR at screening was requisite for enrollment). The primary endpoint was clinically significant CMV infection at week 24 in patients who had undetectable viral load at randomization, and was 37.5% in letermovir group vs. 60.6% in the placebo group with p<0.001. The key secondary end point included clinically significant CMV infection at week 14 and letermovir was superior to placebo (19.1% vs. 50%, p<0.001). There was an increase in clinically significant CMV infection in the letermovir group beyond week 18, related to risks for CMV infection; GVHD and use of corticosteroids. Another key secondary endpoint was all-cause mortality at week 24, which was significantly lower in the letermovir group (10.2% vs 15.9%, p<0.03), although the significance was not maintained at week 48 post HCT. The benefit of letermovir prophylaxis was noted across all HCT types, although the benefit was more pronounced in high risk HCT recipients as defined in the study.

Letermovir was well tolerated with no apparent myelosuppression or nephrotoxicity compared to placebo. Most importantly, it had no negative impact on engraftment which is a major concern post-HCT. Although the side effect profile was comparable between letermovir and placebo, higher rates of nausea, vomiting and peripheral edema occurred with letermovir (not statistically significant). In addition, CMV breakthrough infection occurred in one patient on letermovir, who developed a UL56 V236M mutation. Mutations in the UL56 terminase subunit confer resistance to letermovir[22], although there is no documented cross resistance to GCV, foscarnet or cidofovir.

The field of CMV management is changing at a rapid pace with letermovir poised to be a major game changer by making safe and an effective prophylaxis a reality. It will most likely reduce the burden of CMV infection in the first 100 days & up to week 24 post HCT (when used per FDA indication). However, it is evident from the phase III trial that there is a significant burden of CMV infection upon stopping the prophylaxis due to continued presence of the risk factors for CMV infection[21]. To counter that, strategies to identify patients who are at continued risk for CMV infection will be needed and perhaps employ methods to improve the immunologic status towards CMV such as with vaccination or consideration of risk-adapted prophylaxis with letermovir similar to the antifungal prophylaxis given to patients with GVHD.

3. CMV vaccines in the transplant setting

3.1. Overview

CMV poses important challenges and is the cause of substantial morbidity and infrequent mortality in individuals with compromised immune function, including transplant recipients [7,23]. In recent years, substantial improvements have been achieved in CMV diagnosis, prevention, and treatment to minimize its negative impact on allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT) and solid organ transplant (SOT) outcomes [24]. Despite significant advances in its diagnosis and therapy, CMV remains one of the most common complications affecting patient survival among HCT and SOT recipients, through a multitude of direct and indirect effects [21,25]. The unmet medical need to reduce the burden of CMV morbidity in the vulnerable population of transplant patients remains high.

Harnessing the extensive immune response to CMV, which is commonly mounted in healthy CMV seropositive patients has been the focus of major investigations and clinical trials for more than 40 years [26]. A variety of experimental vaccine approaches to stimulate the host immune response to CMV have been evaluated and many are in various stages of research, though no vaccine strategy to prevent or treat CMV infection or disease has yet been licensed [27]. The property of CMV to establish life-long latency in myeloid cells, and the propensity to re-infect its host despite pre-existing natural immunity are among the multiple CMV immune evasion strategies which makes the development of a vaccine challenging [28,29].

Conduct of clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of CMV subunit vaccines in protecting transplant recipients is relatively recent; nonetheless it already represents a vibrant field of therapeutic investigation. While attenuated viruses were the first strategy investigated in SOT patients [30,31], subunit vaccines have advanced the furthest. Results achieved in the last decade with such vaccine platforms were encouraging, as reported in a Phase II randomized placebo-controlled trials in kidney and liver transplant recipients in 2011 [32], and for the first time in the HCT setting in 2012 [33]. Subsequently, the interest in developing an effective CMV vaccine for transplant patients gained momentum, and funding from both the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the pharmaceutical industry has led to additional ongoing or completed clinical trials (summarized in Table 1) [27]. A CMV vaccine for transplant patients is not yet available for routine clinical use, though some of the vaccine candidates hold great promise and could be licensed in the near future.

Table 1.

Clinical trials of subunit CMV vaccines in the transplant setting

| Vaccine name | Type of vaccine/adjuvant | Targeted response | Trial Sponsor | Transplant setting | Trial Phase | Reference | NCT in clinicaltrials.gov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gB/MF59 | Recombinant gB protein/MF59 (Novartis) | Antibodies to gB | Chiron/Sanofi Pasteur | SOT Recipients: adults | II randomized placebo controlled | Griffiths et al, 2011 | 00299260 |

| ASP0013 | gB and pp65 plasmids/CRL1005 benzalkonium | Antibodies to gB, T cells to pp65 | Vical/Astellas | HCT Recipients: adults | II randomized placebo controlled | Kharfan-Dabaja et al, 2012 | 00285259 |

| ASP0013 | gB and pp65 plasmids/CRL1005 benzalkonium | Antibodies to gB, T cells to pp65 | Vical/Astellas | HCT Recipients: adults | III randomized placebo controlled | n.a. | 01877655 |

| ASP0013 | gB and pp65 plasmids/CRL1005 benzalkonium | Antibodies to gB, T cells to pp65 | Vical/Astellas | SOT Recipients: adults | II randomized placebo controlled | n.a. | 01974206 |

| PepVax | HLA A*0201-restricted pp65495–503 CD8 epitope/PF03512676 (Pfizer) | T cells to pp65495–503 | City of Hope/NIH | HCT Recipients: adults | Ib randomized open label | Nakamura et al, 2016 | 01588015 |

| PepVax | HLA A*0201-restricted pp65495–503 CD8 epitope/PF03512676 (Pfizer) | T cells to pp65495–503 | City of Hope/NIH | HCT Recipients: adults | II randomized placebo controlled | n.a. | 02396134 |

| Triplex | recombinant MVA encoding pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | T cells to pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | City of Hope/Helocyte and NIH | HCT Recipients: adults | II randomized placebo controlled | n.a. | 02506933 |

| Triplex | recombinant MVA encoding pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | T cells to pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | City of Hope/City of Hope | HCT Recipients: children | I/II randomized | n.a. | 03354728 |

| Triplex | recombinant MVA encoding pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | T cells to pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | City of Hope/Helocyte | SOT Recipients: adults | II randomized placebo controlled | n.a. | n.a. |

| Triplex | recombinant MVA encoding pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | T cells to pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | City of Hope/City of Hope | HCT Healthy donors: adults | II randomized open label | n.a. | 03560752 |

| Triplex | recombinant MVA encoding pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | T cells to pp65, IE1-exon4, IE2-exon5 | City of Hope/NIH pending | Haploindentical HCT Recipients: adults | II randomized placebo controlled | n.a. | 03438344 |

NCT= National Clinical Trial identifier number; n.a.= not yet available

3.2. Inducing immunity in an immunocompromised host

The unique and major challenge for a successful CMV vaccine in transplant recipients is inducing immunity in an immunocompromised host. In transplant patients immunosuppression is a dynamic process that is influenced by many variable such as the dose, duration and type of immunosuppressive agents, innate and adaptive host immune defects, age, and underlying comorbidities. Interestingly, the compromised immune system of both SOT and HCT recipients is generally able to mount an adaptive immune response to CMV, despite effective immunosuppression to limit allograft rejection [34–36]. In this scenario, the goal of a protective CMV vaccine is to enhance the magnitude and the functionality of the nascent immune response in transplant recipients to limit and/or protect from CMV reactivation, viremia spreading and EOD [7,23].

There is still a critical lack of knowledge that is an obstacle to the formulation and the development of an effective CMV vaccine for immunocompromised patients. In particular, the correlates of protective immunity in different clinical settings are poorly understood. Previous studies attempted to establish CMV-specific T cell levels in peripheral blood, which are associated with protection from CMV-related complications or overall survival in HCT patients [37,38]. Gratama et al. used iTAg MHC Tetramers (Beckman Coulter) to enumerate CMV-specific CD8 T cells by flow cytometry and found that delayed recovery of CMV-specific T cells (< 7 cells/μL in all blood samples during the first 65 days after HCT) was a significant risk factor for CMV-related complications; these HCT patients were more likely to develop recurrent or persistent CMV infection than patients showing rapid recovery [37]. Zhou et al. evaluated functions of CMV-specific T cells and found that D-/R+ HCTs are associated with delayed recovery of multi-cytokine producing T cells and with increased anti-viral drug usage [38]. Although T cell immunity is believed to play a pivotal role for viral containment, encouraging results have been obtained in SOT patients with vaccines that stimulate neutralizing antibodies, thus more studies are needed to establish the combined importance and role of T cells and antibodies for protective immunity in transplant recipients [32,33,39–41].

3.3. CMV vaccines under clinical investigation

In the next paragraphs, the current status of subunit CMV vaccines for transplant is presented with an emphasis on recently completed and ongoing clinical trials (Table 1).

gB/MF59

Several clinical studies in healthy adults, adolescents and children have used a recombinant glycoprotein B (gB) vaccine formulated with the MF59-adjuvant from Novartis. [42,43]. The recombinant gB from the CMV Towne strain was developed in the 1990s by Chiron, then in 2000 the rights were obtained by Aventis Pasteur (now Sanofi Pasteur) [42]. gB is expressed in the CMV viral envelope, constitutes the core fusion protein in viral entry and is required for the infection of all susceptible cell types, including fibroblasts and epithelial/endothelial cells. gB is also involved in cell-to-cell spreading and is essential for CMV replication [44]. Antibodies to gB are usually present in CMV-seropositive individuals, and are capable of virus neutralization. In 2009, the gB/MF59 vaccine was reported to provide 50% protection to seronegative women of childbearing age from primary CMV infection [42]. The same gB/MF59 vaccine and the same 3-dose schedule were used in a Phase II double-blind study (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT00299260), in adults awaiting kidney or liver transplantation. These patients were given pre-emptive treatment as standard of care, instead of the more common universal prophylaxis [45]. The administration of the gB/MF59 vaccine significantly increased gB antibody titers in both seronegative and seropositive patients, reduced the duration of viremia and antiviral use. Moreover, the duration of post-SOT viremia was inversely correlated to the magnitude of the gB antibody response. However, the number of D+/R- patients in the highest-risk group was small, and the differences with placebo were insignificant. The major effect of the vaccine was on new infections acquired from the donor. Thus, the authors propose that antibodies induced by the gB/MF59 vaccine could bind to the virus in the donated organ, hence preventing CMV transmission to the recipient [32].

A Phase III study in a larger cohort and including patients who receive universal prophylaxis was not initiated to confirm the encouraging results published in 2011 [32]. Among the reasons that may have contributed to the stalling of this project is the critical discovery that the pentameric complex gH/gL/UL128–131 of CMV is the primary target for potent viral neutralization [39,40,46]. Hence, the immune response to the pentameric complex has been extensively studied (see Section 4), particularly its humoral component, which may be evaluated soon in the transplant setting [27,47].

ASP0013

ASP0113 is a bivalent DNA vaccine containing two plasmids that encode gB and CMV tegument phosphoprotein 65 (pp65), adjuvanted with poloxamer CRL1005 and benzalkonium chloride. It was developed by Vical Corporation (as TransVax) and is currently under license to Astellas Immunotherapy [33,48]. The vaccine was designed to target both the humoral immune response, through the gB plasmid (derived from the AD169 CMV strain), and the cellular immune response, through the pp65 plasmid. It aimed to boost pre-existing immunity in CMV-seropositive HCT recipients through therapeutic vaccination. The pp65 tegument protein is among the most frequently recognized CMV antigens in CMV seropositive healthy adults [49]. Importantly, recovery of pp65 CD8 T cells during the first 65 days post-HCT is associated with protection from CMV related complications [37]. Therefore, exploiting native immune responses by therapeutic vaccination during the periods of greatest risk post-HCT could lead to CMV infection control. However, vaccine driven responses may be challenging to elicit, since the recipient’s immune system remains impaired for the first months post-HCT.

After being successfully tested for safety in healthy adults [48], ASP0113 was the first vaccine to be evaluated in a randomized, placebo-controlled Phase II study, in HCT recipients (NCT00285259). It was safely administered early post-HCT, but failed to show significant reduction in CMV viremia requiring antiviral therapy, and significant increases in pp65 and gB immune responses, using protocol specific analyses. In contrast, time-to-first episode of viremia was longer, and rates of CMV viremia were lower in the ASP0113 vaccinated recipients [33]. These findings paved the way for a multicenter placebo-controlled Phase II study in SOT (NCT01974206) and Phase III study in HCT recipients (NCT01877655). In the Phase II trial, a total of 150 patients were randomized, of which 146 received at least one dose of study drug and had at least one post-dose viral load assessment by a central laboratory. Unfortunately, it was reported that there was no difference in the incidence of CMV viremia between ASP0113- and placebo-treated patients through one year post first study drug injection [50]. Results for the Phase III in HCT recipients have not yet been published. In January 2018, on the Astellas website (https://www.astellas.com/en/search?keys=asp0113) it was communicated that the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase III study which enrolled a total of 514 CMV seropositive HCT patients did not meet its primary or secondary endpoints. The results did not demonstrate a significant improvement in overall survival and reduction in CMV EOD.

These disappointing results from the ASP0013 candidate may be due to the type of vaccine technology used. DNA vaccines have evolved greatly since their invention, and many strategies and adjuvant formulation have been developed to increase their potency. Nonetheless, they are not yet a competitive alternative to conventional protein or carbohydrate based human vaccines. Safety concerns were an initial barrier; however the Achilles’ heel of DNA vaccines remains their poor immunogenicity, and no DNA vaccine for human use has yet been approved by the FDA [51].

PepVax

PepVax is a chimeric peptide vaccine composed of a cytotoxic HLA-A*0201-restricted CD8 T cell epitope from pp65 protein (pp65495–503) fused with the P2 peptide T helper epitope of tetanus toxin. It is formulated with the adjuvant PF03512676 from Pfizer, a Toll-like receptor 9 agonist, which augments cellular immunity. PepVax development and production was sponsored by NIH [41]. The abundant tegument pp65 protein, a major T cell target in CMV-exposed individuals, is a principal target for HLA class I–restricted CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) [49,52,53]. Importantly, reconstitution of CMV pp65-specific CD8 CTL post-HCT correlates with protection from CMV and improved outcome of CMV disease [54]. Studies in HCT recipients have indicated that the response directed towards the immunodominant pp65495–503 T cell epitope is involved in CMV viremia protection early post-HCT [37,55]. Using HLA-restricted CD8 T cell epitopes to develop a non-infectious subunit CMV vaccine can eliminate the safety concerns for HCT recipients of live-attenuated CMV or recombinant live viral vaccines, while avoiding the many CMV-encoded proteins involved in immune-evasion [56].

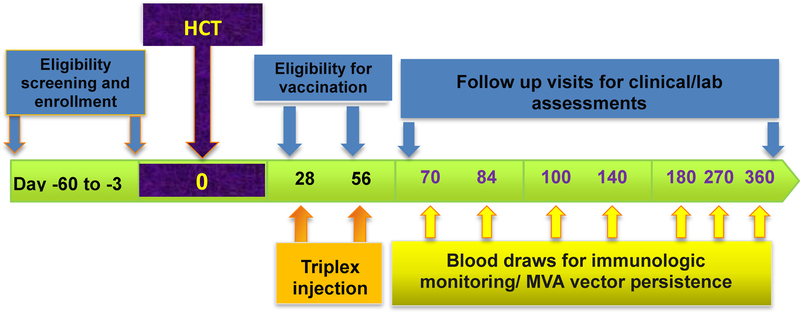

An acceptable safety profile and vaccine-driven expansion of pp65495–503 specific T cells in healthy adults when used with PF03512676 supported further assessment in patients undergoing HCT in a randomized Phase Ib trial (NCT01588015) [41,56]. The PepVax vaccine aimed to expand pp65495–503 specific T cells during the first 100 days post-HCT to protect CMV seropositive patients who are at the highest risk to develop uncontrolled viremia and disease early after transplant [7]. In the study, 36 eligible patients were randomized to either PepVax (n=18) or observation (n=18) arm. Two PepVax vaccine injections were administered on days 28 and 56 post-HCT, with the intent of eliciting a protective immune response preceding CMV reactivation, in the PepVax immunized recipients. The vaccine was safe and well tolerated, and significant immunological and clinical outcomes were observed. PepVax was the first CMV vaccine that achieved three major outcomes in CMV seropositive HCT patients: a significant rise in pp65-specific CD8 T cell levels during the critical 100 days post-HCT (Figure 1), reduced incidence of CMV reactivation and usage of antivirals, and increased relapse free survival [41]. Of interest, PepVax results confirmed previous findings suggesting that humoral immunity is not required for CMV viremia control post-HCT [57]. A larger placebo-controlled, multi-center Phase IIb trial (NCT02396134) enrolling 96 patients has been started to confirm the encouraging results obtained in the Phase Ib trial.

Figure 1.

Immune profiles of PepVax vaccine responders. In the plots, the number of CD8+ T cells specific for the pp65495–503 epitope contained in the PepVax vaccine is reported in the y-axes. Measurements were performed using pp65495–503 pentamers as detailed in [41]. The x-axes show post-HCT time points, in which patient blood draws were evaluated. Arrows indicate PepVax injections. The upper panel reports unique patient number (UPN 14), who received an MRD HCT from a CMV seropositive donor, the lower panel shows UPN 36, who received an MRD HCT from a CMV seronegative donor.

Triplex

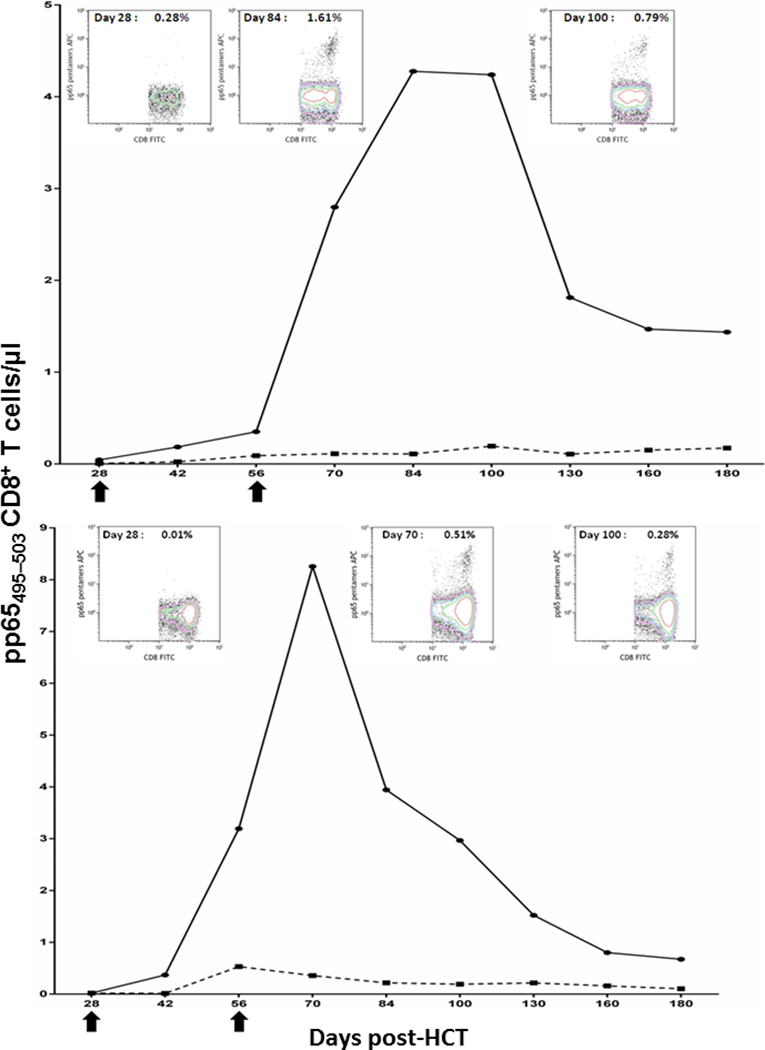

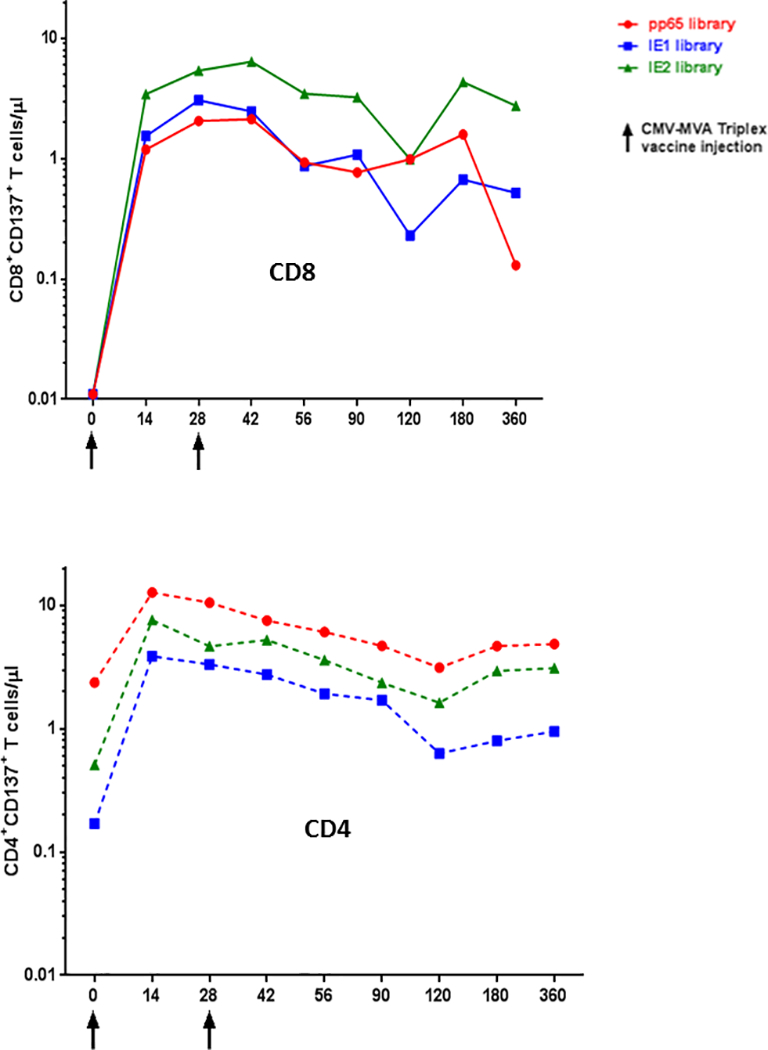

Triplex is a modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA)–based vaccine encoding 3 full-length CMV antigens: pp65, IE1-exon4, and IE2-exon5 [58]. These antigens are highly recognized in the majority of CMV-seropositive healthy subjects and transplant patients, and their role in protective immunity in transplant has been described [49,59–63]. MVA is one of the most advanced and most promising viral vectors for vaccine development and clinical investigation, because of its excellent safety profile and property of inducing potent immune responses against recombinant antigens [64]. A recent study further demonstrated that in HCT recipients MVA was safe and immunogenic[65]. Triplex has been investigated in a Phase Ib dose-escalation study in healthy volunteers, and was found to be highly tolerable and immunogenic. This vaccine induced robust and durable expansion of CD4 and CD8 T cells specific for each immuno-dominant CMV protein both in CMV seropositive and seronegative individuals (Figures 2 and 3) [58]. Based on these encouraging safety and immunogenicity results, a series of clinical trials in different transplant settings have been already or are about to be started.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal CMV specific T cell responses after Triplex vaccination. In the plots, the number of CD3+ CD8+ T cells (upper plot) or CD3+ CD4+ T cells (lower plots) specific for 3 peptide libraries encompassing the pp65, IE1 or IE2 CMV proteins are reported in the y-axes. Measurements were performed by measuring the CD137 surface marker of recent functional activation as detailed in [58]. The figure shows the longitudinal immune response of CMV seropositive UPN 24 healthy study volunteer, who received 2 Triplex injections (at the time indicated on the x-axes) and was followed for 1 year, as per protocol. Triplex vaccine encodes for full length pp65, IE1 and IE2 CMV proteins.

Figure 3.

Polychromatic flow cytometry in a Triplex vaccinee. The dot plots show the Triplex induced expansion of pp65 specific CD3+ CD8+ T cells in UPN 14, a CMV seronegative healthy adult who received 2 Triplex vaccine injections on day 0 and 28. For each indicated day, the percentages (upper right quadrant) of CD3+ CD8+ CD137+ T cells after stimulation with either a pp65 peptide library (right plots) or media as control are shown. Details of the assay and flow cytometry gating strategy are reported in [58].

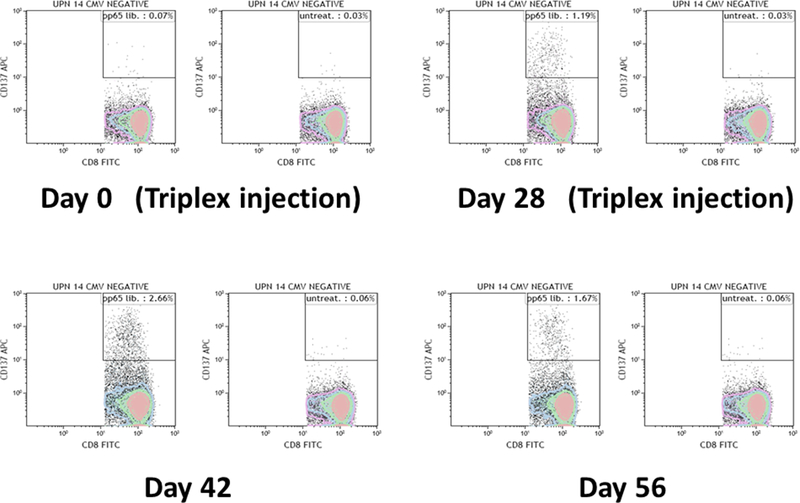

In December 2015, a multi-center, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled Phase II study of Triplex in 102 CMV-seropositive HCT recipients with matched related donor (MRD) or matched unrelated donor (MUD, NCT02506933) was initiated. The Phase II trial is currently closed to accrual with patient follow up to be completed in the fall of 2018. No safety issues were reported in the ongoing trial, in which 2 vaccine injections were administered on days 28 and 56 post-HCT. Triplex vaccine schedule (Figure 4) followed the PepVax study, which provided proof-of-concept that HCT recipients can mount an immune response to vaccine early post-HCT [38,41,66]. The primary study endpoint will be assessed by comparing the rate of CMV reactivation through Day 100 between vaccine and placebo arm. Other study related endpoints will be evaluated such as CMV-specific T cell response, duration of viremia, time on antivirals, graft versus host disease and relapse-free survival.

Figure 4.

Scheme of Triplex Phase II trial in HCT recipients. The figure shows the flow chart of the trial, including timing of eligibility assessments, enrollment and transplant, and lab and follow up procedures as per study protocol.

3.4. Clinical Trials in Development or Recently Activated

A Phase I/II trial to evaluate the optimal dose and the protective effect of Triplex vaccine in pediatric patients has been recently started as a single site study at City of Hope (NCT03354728). Pediatric HCT patients reactivate CMV at a similar rate as in adult HCT, however many standard antivirals have intolerable toxicity for pediatric patients, or have been insufficiently evaluated [67]. Therapeutic vaccination with Triplex is a particularly appealing strategy in pediatric HCT patients because children have relatively rapid immune reconstitution post-HCT, likely because they have an intact thymus that promotes T cell proliferation [7,68–70]. The multisite trial will enroll 12 patients in the Phase I portion to investigate the optimal dose of Triplex in pediatric patients, and 61 patients in the Phase II portion to determine whether Triplex reduces the frequency of CMV events, when compared to historical data.

A small Phase II pilot trial to evaluate the safety and feasibility of vaccinating HCT donors with the Triplex vaccine has been activated at City of Hope (NCT03560752). The trial aims to boost levels of CMV-specific T cells prior to apheresis for HCT. The hypothesis is that the in vivo primed CMV-specific T cells will expand and remain active when infused into CMV seropositive recipients [71,72]. Future studies may examine if Triplex vaccination of HCT recipients, in combination with donor vaccination, can further boost levels of CMV-specific T cells received from their donors and generate CMV protective immunity.

Despite the use of antiviral prophylactic and preemptive treatments, CMV-related infection represents one of the main causes of morbidity after haploidentical HCT (haploHCT) for hematological malignancy [73]. Haploidentical HCT-donors have been increasingly used when no conventional MRD or MUD can be identified [74]. However, the incidence of CMV reactivation is very high in haploHCT reaching rates of >75% [73,75], at least partly due to profound immunosuppression associated with post-transplant cyclophosphamide. Consequently, these patients require an urgent solution to prevent CMV infectious complications. Triplex will be used in a recently activated Phase II randomized placebo controlled trial, as a vaccine to restore antiviral immunity in CMV seropositive recipients receiving haploHCT (NCT03438344).

4. Congenital cytomegalovirus prophylactic vaccines

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is the leading cause of congenital infection worldwide, with infection rates ranging from 0.5–0.7% in the US and Europe and up to 1–2% in developing countries such as Brazil and India [76–78]. Recent estimates based on birth rates show that approximately 20,000–35,000 infants in the US and Brazil are born with congenital infection, while in India more than 250,000 newborns are affected by congenital HCMV (cCMV) infection annually [79]. The majority of those children affected by cCMV infection will not show any clinical findings at birth, but 10% to 15% will have a clinically apparent or symptomatic infection [80]. Congenital HCMV infection symptoms range from rash and jaundice to major neurological abnormalities such as microcephaly, seizure, and cerebral palsy. Of those children that are asymptomatic at birth, congenital disease may develop during later life. cCMV is the main infectious cause of sensorineural hearing loss, which is found in about 50% of symptomatic and 10–15% of asymptomatic cCMV infected children [81]. Transplacental transmission of HCMV can occur as a consequence of primary infection, reactivation or superinfection, but the likelihood of transmission is higher in primary infected women (1–2%) than in non-primary infected women (30–40%) [82].

4.1. Congenital CMV vaccine: rationale

The development of a vaccine to prevent cCMV infection would be aided by the knowledge of the immune correlates of protection. However, the precise immune responses that prevent or control HCMV infection in the mother or the developing fetus, or that interfere with intrauterine virus transmission at the fetal-maternal interface remain unknown [83]. Preconceptional maternal immunity provides only imperfect protection against congenital HCMV infection as a consequence of virus reactivation from latency or superinfection with a different HCMV strain [84], although it can significantly reduce the risk of virus transmission to the developing fetus [85]. Under this premise, it can be hypothesized that a vaccine capable of being equivalent or superseding the immunity given by natural infection may provide substantial protection against cCMV infection. Despite the ill-defined immune correlates of protection, it is thought that an effective cCMV vaccine candidate will need to stimulate both humoral and cell immune responses. Antibodies are known to be important to prevent or limit virus acquisition and spread through their effector functions (neutralization, complement dependent cytotoxicity, antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity, antibody-mediated opsonization and phagocytosis) while T cells may be essential to contain and clear the infection once CMV infection has occurred at mucosal membranes and to support B cell responses [86–88]. Another important characteristic to consider in conceptualizing a cCMV vaccine is the ability to induce cross-protective immune responses able to prevent the infection or limit the spread of heterogenous CMV strains. A large number of CMV strains circulate in the human population and can mutate quickly even within a single host [89,90].

4.2. Live-attenuated and replication-defective vaccines

The first attempts to develop a cCMV vaccine were based on the use of live-attenuated strains such as AD169 [91] and Towne [92]. These strains have been extensively passaged in vitro using fibroblasts during which they experienced many genome alterations including the partial loss of the UL/b’ genome region, which contains genes for host cell tropism and immune evasion. These genome alterations rendered AD169 and Towne defective in their in vivo infectivity as proven by the lack of viral latency when Towne was used to immunize immunosuppressed solid organ transplant recipients [93]. Towne was shown to partially protect HCMV seronegative adults against challenge with the non-attenuated, low-passage HCMV strain Toledo, but the Towne-vaccinated individuals were significantly less protected against Toledo challenge than HCMV-seropositive individuals [94]. Moreover, Towne failed to provide protection in HCMV seronegative women of childbearing age whose children went to daycare [92]. Based on these observations, it has been hypothesized that the extensive passaging in vitro may have rendered the Towne strain too attenuated to generate robust protective immunity [95,96].

4.3. Towne/Toledo chimeric viruses

As an attempt to improve the immunogenicity provided by Towne, four Towne/Toledo genome chimeras have been generated by substituting portions of the Toledo strain UL/b’ region with those of the Towne strain [97]. When tested in phase I clinical trials, the Towne/Toledo chimeras were attenuated relative to Toledo [98], showed acceptable safety profiles, and stimulated immune responses similar to those conferred by Towne [99]. Due to a point mutation in the Towne UL130 gene and a mutation in Toledo UL128, the chimeras failed to express the envelope pentamer complex (PC) composed of gH, gL, UL128, UL130 and UL131A [99], which, as described below, has been recognized as a major target of NAb responses.

4.4. V160: repaired AD169 CMV strain

More recently, a conditionally replication-defective derivative of HCMV strain AD169 has been developed by Merck, Sharpe and Dohme (Rahway, NJ). This replication-defective modified AD169 strain, named V160, which contains a repaired UL131A gene locus, expresses all relevant HCMV antigens including the PC, whereby its conditional replication deficiency is based on the addition of a synthetic compound [100]. V160 was proven to be tolerable and immunogenic in healthy adults and conferred humoral and cell-mediated immune responses that were comparable to baseline levels measured in seropositive subjects [101]. Although the vaccine is advancing to a phase 2b clinical trial in healthy seronegative women with direct exposure to young children (NCT03486834), a major challenge in advancing V160 beyond phase II is the need to use human epithelial cells (EC) for its production [102,103].

4.5. Recombinant gB protein vaccines

The finding that the preponderance of the neutralizing activity in serum of convalescent individuals specifically targets gB when based on measurements using fibroblasts [104] encouraged the field to focus on this envelope glycoprotein as a subunit vaccine component. Recombinant gB combined with MF59 adjuvant has been extensively tested in clinical trials including seronegative [105,106] and seropositive adults [107], toddlers [108] and transplant recipients [32]. Overall, the gB/MF59 vaccine demonstrated an acceptable safety profile and stimulated low titer neutralizing antibodies and high titer gB-specific binding antibodies which, however, declined rapidly after 6 months [106,109,110]. When gB/MF59 was tested in a randomized, placebo-controlled and double-blind trial in seronegative women within 1 year of giving birth, it demonstrated 50% efficacy on the basis of infection rates per 100 person-years over the 42-month trial period, with the highest protective effect observed in the first 12–15 months [111]. In this trial, non-neutralizing antibody functions, including virion phagocytosis were later found to be elevated in the vaccinees in comparison to chronically HCMV-infected individuals.[110] Similar results were observed in a recent randomized multicenter trial in adolescent girls in which gB/MF59 reached slightly lower efficacy rates (43%) [43]. However, the efficacy rates provided by gB/MF59 in the multicenter trial did not reach statistical significance. Consequently, as a result of the lowered efficacy in the multi-center trial, gB/MF59 has not advanced to a pivotal trial for consideration of licensure.

4.6. The Pentamer Complex

In recent years HCMV vaccine research has refocused to include the envelope PC due to the recognition that it is required for HCMV entry into epithelial cells (EC), endothelial cells, and monocytes/macrophages, all cell types of critical importance for HCMV natural history [112–114]. Compared to NAb targeting other envelope glycoproteins such as gB or gH/gL, NAb targeting linear and conformational epitopes of the PC are extremely potent in blocking in vitro HCMV infection of EC, endothelial cells, and monocyte/macrophages [115–117]. Of note, EC-specific NAb response have been shown to be significantly lower in gB/MF59 and Towne vaccinees than in HCMV seropositive individuals [118], suggesting that the lack of PC-specific NAb might have contributed to the low efficacy of these vaccine candidates in clinical trials. Studies in mice and rhesus macaques using a Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) virus as vaccine platform to deliver the five PC subunits showed that the PC subunits are sufficient to induce extremely high titer NAb preventing EC infection with heterologous HCMV strains. Moreover, these studies have shown that the PC, besides being able to stimulate EC-specific NAb responses, can also stimulate NAb responses that interfere with FB infection due to the capacity of the PC to elicit NAb that target epitopes of gH. [39]. In addition, differently from gB-specific antibodies, the majority of PC-specific antibodies have neutralizing activity [46], and they constitute the preponderance of the anti-CMV neutralizing response in CMV hyperimmune globulin [119]. Finally, a delayed antibody response to the PC has been correlated with HCMV transmission to the fetus [120]. As of today, the immunogenicity of the PC as a vaccine component has been extensively investigated in pre-clinical studies using different vaccine platforms [39,46,121–125], yet it has not been evaluated in clinical trials.

4.7. Next generation cCMV vaccines

Given the likely requirement for a cCMV vaccine to stimulate both humoral and cell-mediated immunity, the ideal vaccine candidate should (1) express the main antibody targets (PC and gB) to induce binding and cross-protecting neutralizing antibodies to prevent HCMV infection of most cell types; (2) express the main cellular immunity targets (pp65, IE1, IE2) to promote the killing of infected cells; (3) have an excellent safety profile; and (4) use a platform that allows easy scale-up for bulk production. Besides the live-attenuated vaccine approach [100], only a few vaccine strategies appear to allow efficient synchronous delivery and/or expression of multiple antigens. Amongst these MVA is a suitable vaccine candidate given the large capacity for foreign genes, the excellent safety profile demonstrated by its long history as a vaccine for smallpox vaccination, its potent immunogenicity to stimulate antigen-specific humoral and cellular immune responses, and its thermo-stability and ease of scalability for commercial production [64,126–128]. Dense bodies are also under investigation as an HCMV vaccine, although they do not seem to allow induction of high titer EC-specific NAb [129]. Viral-like particles are another attractive platform that can be developed to incorporate both glycoproteins and T cell targets, but the only one developed so far is based solely on gB [130]. Other platforms that are currently under development but that would require a multi-component vaccine to incorporate both antibody and T cell targets are DNA vaccines [131], RNA vaccines [125], and vectored vaccines (replication-defective lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus vectors [132], adenoviral vectors [133], canarypox vectors [134,135], vesicular stomatitis virus vectors [136]). Over 50 years of HCMV vaccine research, including extensive animal models and clinical studies, gives us hope that a cCMV vaccine is one step closer to realization.

5. Novel uses of CMV vaccines

The immune system and methods for modulation of immunity influences areas of medicine in ways other than prevention of infectious disease. Several sections of this Review cover the use of vaccines in transplant recipients and prevention of infection of healthy adults and children, but in the future vaccines will be applied to effect areas of medicine in their role as modulators of immunity. In this section, we discuss how vaccines can be used in novel ways as adjuncts in antiviral prophylaxis, in activation and maintenance of cellular therapies, and to reverse autoimmune diseases.

5.1. Use of vaccines in support of early termination of antiviral therapy

Currently, in the setting of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), prophylactic antivirals are used routinely to reduce the reactivation of certain herpesviruses, e.g., use of acyclovir for herpes simplex virus (HSV) or varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and ganciclovir or letermovir for cytomegalovirus (CMV). But antiviral prophylaxis has a negative effect on immunity post-HCT, since without adequate exposure to these viruses, there is inadequate immune reconstitution. Then, when short-term prophylaxis is stopped, virus often reactivates. As a result, patients are kept on the antiviral medications for extended periods [137]. However, the availability of a VZV vaccine, allows sequential first use of antiviral acyclovir for 6–12 months or more, and then, at 24 months, vaccination against VZV is conducted, if the patient is not receiving immunosuppression for GVHD and ceased receiving IVIG supplements [138]. The current use of letermovir (see Section 1) for prevention of CMV represents another clinical situation in which the use of a CMV vaccine, if available, could be introduced to minimize the use of this relatively expensive antiviral. It is possible that a vaccine for hepatitis C virus, if available, could have a similar use in shortening the antiviral therapy of this virus and minimize cost.

5.2. Use of vaccines in support of cellular therapies

There is considerable interest in the use of CAR T cells in management of cancer, and effectiveness of treatment is a function of cell proliferation post-infusion [139]. The inability of CAR T cells to proliferate post-infusion and the loss of circulating CAR T cells are both important risk factors for subsequent relapse of disease [139]. Virus-specific central memory T cells are long-lived, and by use of virus specific T cells to manufacture CAR T cells, the CAR T cells could be responsive to endogenous viral signals for proliferation and activation. This concept was first tested in vitro and shown to be feasible using either EBV-specific T cells [140] or influenza-specific T cells [141]. The first example of this in a clinical trial used EBV-specific CTL engineered to express a CAR targeting diasialoganglioside (GD2) for neuroblastoma cells [142]. The clinical trial [NCAT00085930] showed that EBV-specific GD2 CARs persisted in higher numbers and for a longer time than conventional GD2 CAR T cells after administration to EBV seropositive patients with neuroblastoma. In addition, these EBV/GD2 bispecific CARs maintained cytotoxic function for both EBV- and GD2-target cells [142], and when the EBV-CAR T cells persisted beyond 6 weeks, there was a superior clinical outcome [143]. To test this further, CAR T cells targeting HER2 were made from T cells expanded during exposure to CMV, EBV, and adenovirus antigens [144]. In a phase I dose-escalation study [NCT01109095], these multivalent virus-specific T cells (VST) administered to patients with HER2-positive glioblastoma showed persistence in peripheral blood for up to 12 months, but there was no expansion [145]. Finally, VST/CAR T cells targeting CD19 were made in allogeneic cells and administered to patients who had relapsed with a CD19+ leukemia after undergoing allogeneic transplantation [146]. In this trial (NCT00840853), cells persisted for only a median of 8 weeks, with transient anti-tumor activity seen in several patients. However, in those with intercurrent EBV or adenovirus infection, the CAR T cells showed increases in blood levels. This suggests that stimulation of the virus:tumor bispecific CAR T cells with viral antigens might be necessary for a clinical effect.

To test whether a viral vaccine could be used with CMV:CD19 bispecific CAR T cells (biCAR), a proof of concept model was studied in CD19+ tumor-bearing NSG mice which received the CMV:CD19 biCARs with or without a CMV vaccine. Using CMV peptide vs influenza peptide loaded autologous antigen presenting cells, the CMV vaccine enhanced CAR T cell therapy was more effective in killing tumor than were the CMV:CD19 biCARs used alone or with the influenza vaccine [147]. More recently, Tanaka et al. have demonstrated in vitro that VZV peptide stimulation rescues cytotoxic function in VZV:GD2 biCARs, rendered dysfunctional by repeated in vitro exposure to tumor [148]. A dendritic cell (DC) vaccine using CMV peptides has been used safely to boost CMV-specific T cells given to patients after allogeneic HCT [149]. It will need to be shown in clinical trials that vaccine-assisted biCARs will have better persistence and improved anti-tumor effect, but this approach deserves to be evaluated.

The concept need not be limited to cancer immunotherapy. With HIV, a limiting step in immunotherapy is the absence of viral antigens during antiretroviral therapy, and without the stimulatory effect of HIV antigens, the T cells do not persist. The use of a vaccine could be essential to effectiveness of any T cell strategy for HIV. Similar to the bispecific strategy that combines VST cells with CAR specificities, we have proposed that CMV:HIV biCAR could be combined with a CMV vaccine so that blood levels of the CAR T cells could be maintained during the aviremic period of anti-retroviral therapy. Alternatively, a CMV vaccine could be used strategically to activate CAR T cells prior to an analytic therapy interruption (ATI) during which the immune attack on the HIV reservoir, now displaying viral antigen, would, in theory, be accomplished.

5.2. Use of vaccines in autoimmune disease

The reduction or elimination of immunologic autoreactivity without compromising general protective immune function could be curative for diseases ranging from rheumatoid arthritis, to chronic neurologic disease, to diabetes. Modulation of immunity by use of novel vaccines is feasible (see review [150]. For example, Tsai et al. have vaccinated mice at risk for diabetes with MHC-insulin peptide nanoparticles and prevented or treated type 1 diabetes [151]. The mechanism of action appears to involve the expansion of regulatory T cells which suppress auto-antigen presenting cells. Similar antigen-specific immune modulation has been demonstrated using a dendritic cell (DC) vaccine in which DCs are made tolerogenic by treatment with vitamin D3 and dexamethasone and loaded with autoantigen [152]. Clinical studies are currently evaluating this novel approach for use of therapeutic vaccines.

6. Animal Models and CMV: Vaccine Implications

While an abundance of information can be extrapolated from in vitro analyses of CMV pathophysiology, it is challenging to provide compelling evidence based on animal models to study what occurs during natural infection. Animal models can serve as valuable tools for performing in vivo observational analyses of potential disease therapies and understanding pathogenesis. Depending upon what aspect of CMV pathogenesis is to be examined, choosing an appropriate animal model that best represents what occurs during infection with CMV or how an infected animal responds to CMV therapies is critical. One major limitation to finding an optimal animal model is that CMV is highly species-specific; therefore the study of HCMV can only be indirectly performed in small animal models. Furthermore, there is extensive sequence diversity in species-specific strains of CMV. CMV has undergone extensive adaptation to its host, thus leading to host specificity. CMV strains that are currently being evaluated in their cognate animal models are mouse CMV (MCMV), rat CMV (RCMV), rhesus macaque CMV (RhCMV), and guinea pig CMV (GPCMV). Chimpanzee CMV (CCMV) and the chimpanzee have not been widely used as a model due to the fact that it is a protected species, therefore will not be further discussed. Since most animal CMVs have been sequenced, important homologs that encode genes related to viral replication and subsequent infection in their respective animal hosts have been studied [153–157]. Aside from species specificity, choosing which animal model best represents the various pathologies of each disease caused by HCMV has been an obstacle for therapeutic/observational studies. Commonly used animal models will be briefly discussed, each with their unique contribution to understanding CMV infection and/or potential for exploring vaccines or therapeutic formulations, including limitations that may arise from studying a severely host-restricted pathogen.

6.1. Murine models and MCMV

The relatively low cost of mice colonies in comparison to other animal models and the availability of multiple humanized mouse models has made the use of mice and MCMV attractive for in vivo studies that have otherwise been restricted to in vitro human cell investigations[158,159]. HCMV and MCMV genomic sequences are distinct [154] although functionally homologous in terms of gene expression, cell tropism, and pathogenesis [160,161].

6.2. Immediate Early Antigen Vaccines

One of the first examples in which an antigen was dissected for its influence on protective immunity against a virus comes from MCMV infection of BALB/c mice. Using a time tested approach of construction of a vaccinia virus (vv) expressing the murine IE1 antigen, it was shown that CTL specific for the IE1 (pp89 antigen) could be elicited by vv infection of BALB/c mice. Subsequently, the vv vaccine was shown to protect mice against a lethal challenge dose of MCMV, an important result in the history of demonstrating that CTL function can be protective against lethal virus challenge[162]. Furthemore, a vv that expressed the nonamer T cell epitope determined from the IE1 immediate early protein (pp89) delivered by a vv was shown to protect against a lethal MCMV infection. This result demonstrates that a minimal cytotoxic epitope of nine amino acids is sufficient to elicit CTL that will protect against a lethal viral infection[163]. Similarly, the peptide epitope emulsified in the human-compatible adjuvant Montanide ISA 720 was also capable of protecting BALB/c mice against a lethal MCMV infection[164]. Early studies regarding adaptive immunity and acute MCMV infection revealed a large subset of CTL precursors targeting infected cells producing viral non-structural, immediate early (IE) antigens [165]. Characterizing the immune response to IE proteins in acute infection clarified the immunodominant role of an MCMV viral antigen that is a non-structural protein. MCMV virus-specific CD8+ CTL, particularly ones that were specific for IE antigens, were found to control and protect congenic mouse strains from infection [166]. MHC class I-restricted antigenic peptide from the IE non-structural protein was predicted as a peptide containing HFMPT motif as part of the antigenic core for CTL IE1 (pp89) clones [167]. This was the first predicted and described MCMV epitope that was identified via truncation analysis from a compilation of known peptides in addition to the use of prediction algorithms, which formally proved that CD8+ CTL could protect a BALB/c mouse from lethal MCMV challenge.

6.3. MCMV antigens as vaccines that provide protective immunity

In parallel to vaccine studies in humans, there was an effort to evaluate MCMV homologs of HCMV tegument proteins to provide protection against viral challenge, along with IE1-pp89. A strategy that has been championed by many in the vaccine field was an investigation of DNA vaccines and coding antigens to be evaluated as protective by generating T cell response. In a report that evaluated multiple tegument non-structural antigens, M84 (HCMV-pp65 homolog) was found to be protective in combination with IE1-pp89 using a BALB/c congenic mouse model[168]. Interestingly, protection was haplotype specific, as spleen titers were reduced in BALB/c mice, whereas C3H/HeN mice showed no improvement in protective response or reduction in spleen titer. Further refinements were found that enabled long term and durable protection against subsequent viral challenge. In fact, the subunit vaccine was superior than MCMV in conferring protective immunity. One may interpret this result that the bona fide MCMV has encoded immune evasion genes that inhibit protective immunity as has been shown in HCMV, which may be the underlying reason why once infected, there is no current approach to eliminating persistent virus. In addition, the propensity of HCMV to superinfect when there is already established immunity may be the consequence of immune invasion that interferes with establishing durable immunity which may be a lesser problem when using a subunit vaccine [169]. Susbsequently, it was found that to enable the highest level of protection, additional genes were necessary to add to the vaccine, which is detailed in the report. However, protection was incomplete unless a form of the virus itself (referred to as formalin-inactivated MCMV, or FI-MCMV) was also administered, which indicated that a solely subunit strategy was unlikely to succeed and that unknown additional immune responses were required for maximal protection against viral challenge[170]. To simplify the regimen, a preparation of three key expression plasmids (IE1, M84, and gB) was used as a prime, followed by FI-MCMV boost which elicited high levels of T cell and humoral responses including virus neutralizing antibodies. In this case, both a systemic and mucosal intranasal challenge was suppressed by this immune combination [171]. However, the need for FI-MCMV limits the universal applicability as the translational value of utilizing the pathogen as vaccine is less desirable that using a less toxic subunit vaccine such as a DNA, or MVA (see Section 2) vaccine.

6.4. Immune evasion and protective immunity against MCMV challenge

The complication to obtain protective host immune responses to CMV has been the large-scale immune evasion gene set that likely enables lifelong persistence of the virus and attenuation of immunity. These concepts have been reviewed by multiple authors[172,173]. One striking example was demonstrated using the M45 antigen and identifying an immunodominant epitope for C57BL/6 mice[174]. In this case, a deletion of an immune evasion protein (M152/gp40) restored M45-specific T cells and protection against MCMV challenge. In light of those results, and alternative approach was described in which additional homologs of HCMV proteins which were not subject to inhibition of presentation by immunoevasion proteins was uncovered[175]. The essential proteins M54 (DNA polymerase) or M105 (helicase) were found to be protective against viral challenge in combination with IE1-pp89. A more recent comprehensive strategy examining multiple MCMV viral proteins was undertaken and the discovery made that there was evidence of immune response to 27 open reading frames while 18 of those proteins had H-2b restricted epitopes that could form the basis of a vaccine strategy. These studies highlight the complexity of vaccination approaches for CMV in a highly refined animal model that has relevance to HCMV studies. Whether the immune profile and vaccine targeting of MCMV relates to HCMV is still not fully understood, as profound differences in the structure and function of genes in both species-specific strains complicates direct comparisons of human and mouse correlates of protection[176].

6.5. Rat Models

The rat model has been useful in studying vascular disease and solid organ transplant rejection resulting from RCMV infection [177]. An H2O2-inactivated RCMV strain was investigated, resulting in a time-to-rejection delay of cardiac allograft; however the timing of the vaccine was important in terms of providing protection to the allograft recipient [178]. This vaccine evoked a protective response by preventing transplant vascular sclerosis brought on by RCMV infection and extended graft survival to control levels; however, it was not reported to prevent the virus from reactivation. Another study reported the successful infection of rats with HCMV strain AD169 supernatant by injection into the peritoneum after liver transplantation and immunosuppression by cyclosporine [179]. Taken together, based on years of research conducted using the MCMV model, this model has provided valuable insight regarding immune response to viral infection.

6.6. Development of a Guinea Pig Model for Design of Congenital CMV Vaccines

GPCMV has limited homology to the HCMV DNA genome, but has other similarities that facilitate the use of the guinea pig as an important animal model, especially in conjunction with infection by the salivary gland-isolated GPCMV [153,180–187]. Recently, the complete genome of cell-culture attenuated GPCMV has been published [188], further verifying the presence of immunodominant and neutralizing epitopes found in HCMV, especially the homologs of UL128-UL131[186], in addition to glycoproteins gH, gL, gB, and tegument protein pp65. There are several advantages in utilizing the guinea pig as a congenital CMV model: 1) the relatively long gestation periods (up to 70 days) [189]; 2) guinea pig placental architecture has been well studied [190,191]; 3) the structure of the guinea pig placenta is similar to that of humans, containing a hemomonochorial placenta with a fetal/maternal transport barrier similar to that of the human placenta [190,192,193]; 4) guinea pigs are easily bred and handled; 5) GPCMV crosses the placenta, infecting guinea pig pups—arguably unlike any known mouse model [194], and thus; 6) guinea pig pups have similar EOD to humans [195–197].

There has been interest in applying a GPCMV model to compare immunogenicity, pregnancy outcome, and congenital viral infection following pre-pregnancy immunization. A recent study examining vaccinated and control dams challenged with salivary gland-adapted GPCMV at midgestation with a modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA)-vectored vaccine expressing either gB or concomitantly with an MVA expressing a pp65 homolog, GP83, showed that vaccination with MVA expressing both GP83 and gB does not diminish pup mortality nor increase protection of pups against congenital GPCMV [198]. Taken together, the guinea pig model is valuable in recapitulation of vertical transmission of GPCMV from dams, thereby resulting in pathogenesis of congenitally CMV infected pups as is observed in humans.

GPCMV also encodes HCMV homologs of immediate early genes IE1/IE2 [199], pp65 and gB [200,201]; these viral antigens have been suggested as vaccine candidates against congenital CMV infection. As previously mentioned, and similar to RhCMV, GPCMV also encodes homologs to the subunits of the HCMV pentameric complex gH (gp75), gL (gp115), UL128 (gp129), UL130 (gp131), and UL131 (gp133) that are essential for epithelial tropism [202–204]. As has been observed for HCMV entry into epithelial cells [117,205], disruption of pentameric complex formation prevents GPCMV entry into epithelial cells [203,206]. While a pentameric complex-based vaccine is promising [39,47,207], as has been shown in the rhesus macaque model [116,208], pre-existing immunity is important to protect the fetus [202,209].

6.7. Pathophysiology of CMV Infection Using the RhCMV: Rhesus Macaque Model

Rhesus macaques are an attractive model to study the process of congenital infection because they share similar placental structure to humans [193,210]. The model is also invaluable to study pathogenesis, and host immune responses to RhCMV[210–213]. However, due to high cost and low availability of CMV-negative animals, this model is less feasible for evaluating prophylaxis than smaller animal models [214]. Despite this, the development of a model for congenital CMV in rhesus macaques has been pursued. There is a presumption from clinical studies that maternal immunity reduces the incidence of infection in newborns and perhaps decreases the severity of sequelae in the infected infant [215,216]. Based on the genomic similarities between HCMV and RhCMV, in addition to the placental similarities between rhesus macaques and humans [193,210], this model is a valuable option for the study of congenital HCMV. However, experimentally causing congenital infection within a monkey colony is difficult; intrauterine and intracranial fetal inoculation in the rhesus macaque model is the current form of recapitulating HCMV congenital infection, which includes infant viral shedding [217], and pathologies observed in humans [218]. While these studies have elucidated and paralleled ways in which CMV affects the developing fetus [218], there has yet to be a model that can more accurately illustrate vertical transmission of CMV via natural infection. Nevertheless, rhesus macaque immunobiology and RhCMV pathogenesis can serve as a platform for testing new vaccine strategies. For example, RhCMV has a homologous HCMV UL128–131 locus that is necessary for infection of epithelial and `endothelial cells [210,218]. In HCMV, this locus encodes three protein subunits that form a pentamer combined with gH and gL [219–221]. This five-subunit pentameric complex elicits potent neutralizing antibodies which block entry into epithelial and endothelial cells [40,116,124,208]. Vaccination with a viral vaccine vector expressing the pentameric complex has shown that pre-existing immunity can help protect the fetus from vertical transmission as well as protect newborns in the rhesus model [216]. In summary, utilizing both a rhesus macaque and guinea pig model to study congenital infection could aid in determining the best approach for developing a superior therapeutic or vaccine against congenital CMV.

7. Expert Commentary: Rationale and Challenges of a CMV vaccine

Based on the 2001 cost-benefit assessment by the Institute of Medicine for high priority vaccine targets [222], an ideal HCMV vaccine candidate should protect against HCMV infection and disease in both pregnant women and transplant recipients. Because protection against HCMV infection in these target populations is thought to be mediated by different immune responses [27,223], a “universal” HCMV vaccine candidate may need to stimulate multi-functional immune responses that cover both arms of adaptive immunity. While the role of CD8+ T cells to immunodominant antigens such as phosphoprotein 65 (pp65) and immediate-early 1/2 proteins (IE1/2) in controlling HCMV reactivation in transplant recipients is well-known [29], more recent findings with gB/MF59 indicate a critical role of gB-specific antibodies in protecting against HCMV viremia [32]. This protection afforded by anti-gB antibodies appears to be primarily mediated by humoral responses that target the gB antigenic domain 2 (AD2) [224], but does not seem to depend on neutralizing antibodies (NAb) or antibodies mediating antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [109]. Because the gB AD2 is generally considered of low immunogenicity during natural HCMV infection, it is suggested that the enhancement of gB AD2 immunogenicity could improve protection against HCMV viremia [225]. Although much has to be learned about HCMV immune correlates of protection in transplant recipients [226], it seems that HCMV infection and disease in this target population may be optimally controlled by the stimulation of pp65 and IE1/2-specific T cell responses as well as gB-specific antibodies. Additional strategies that may benefit transplant recipients involves combining a vaccine post-letermovir prophylaxis since there is an acknowledgement that the protection afforded by the antiviral wanes after cessation of dosing. Various approaches and combinations can be considered as an adjunct to improve the period of protection against CMV infection in the transplant population.

Despite advances in the understanding of the immune responses that prevent cCMV infection [88], the precise immunological correlates involved in the protection against cCMV infection remain unclear. Similar to the prevention of HCMV infection in transplant recipients, effective prevention of cCMV infection may depend on the stimulation of both humoral and cellular immunity. Potent NAb responses, NAb targeting the PC, and pp65-specific CD4+ T cells have been implicated with reduced risk of intrauterine HCMV transmission following primary maternal infection [120,227–229]. In addition, hyperimmune globulin treatment during primary maternal HCMV infection has been shown to be beneficial to prevent or reduce cCMV infection and disease [230], although this remains controversial [231]. These clinical findings are further bolstered by studies using surrogate animal models, most notably the guinea pig model of transplacental virus transmission and the more recently developed non-human primate (NHP) rhesus macaque model of cCMV infection [212,232]. Passive immunization and vaccine studies using these surrogate models have shown that hyperimmune globulin preparations, antibodies specific for gB or gH/gL, and CD4+ T cells play a role in preventing intrauterine virus transmission and fetal demise [216,233–235]. In addition, the NHP studies indicated an inverse correlation between the reduction of maternal virus load and the prevention of transplacental virus transmission [216], suggesting that the control of maternal viremia may be one mechanism that contributes to prevention of cCMV infection. Notably, while neutralizing antibodies are generally thought to be a primary immune component in preventing HCMV infection, recent findings suggest that the protection afforded by gB/MF59 against primary infection of postpartum women was primarily mediated by other antibody effector functions such as ADCC or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) or virolysis [111]. These findings in sum suggest that vaccine-mediated protection against congenital HCMV infection involves induction of multi-functional antibody response that target different envelope glycoproteins as well as CD4+ T cell responses.

Major challenges in developing a prophylactic HCMV vaccine candidate to prevent congenital infection include the conundrum of imperfect protection against cCMV infection by naturally acquired immunity, as cCMV infection can occur following primary maternal infection, as well as following non-primary maternal infection as a consequence of re-infection or virus reactivation [236,237]. In fact, most cases of cCMV are a consequence of non-primary maternal infection, in particular in populations with high HCMV seroprevalence [238]. Because of the imperfect protection by natural HCMV immunity, it is suggested that a vaccine candidate capable of eliciting immune responses that resemble those induced during natural infection will likely not significantly alter the outcome of cCMV infection [237]. However, naturally acquired HCMV immunity has been shown to reduce the risk of cCMV infection in future pregnancies by 69% [85]. In addition, while cCMV infection as a consequence of primary maternal infection is estimated to occur with a frequency of 30–40%, cCMV infection as a result of non-primary maternal infection is estimated to occur with a frequency of only 1–2% [78]. Furthermore, cCMV infection following non-primary maternal infection is thought to have less severe neurological disease outcomes than cCMV infection as a result of primary maternal infection [88,238]. Thus, although imperfect, the protection afforded by pre-existing HCMV immunity against cCMV infection and disease appears to be substantial. Under this premise, it can be hypothesized that incidence of cCMV infection and the severity of cCMV disease can be significantly reduced by a vaccine candidate capable of stimulating robust humoral and cellular HCMV immune responses.

Considering that most cases of cCMV infection occur as a consequence of non-primary maternal infection, HCMV seropositive or seronegative women should be considered for vaccination. Vaccination of HCMV seropositive women may boost or broaden immune responses induced during natural infection, thereby reducing the risk of congenital infection and disease upon re-infection or virus reactivation. As stated in the 2001 monograph, the optimal choice for vaccine candidate to prevent congenital infection is a mother of childbearing years prior to pregnancy as well as adolescents up to the age of 12 who are in a daycare or group setting such as is typical of school-age children. The purpose of controlling infection in adolescents is because they shed virus, causing horizontal spread, thereby infecting other susceptible children who may then act as transmitters to their seronegative mother with consequences for an in utero developing fetus. The more conventional approach of vaccinating a woman of childbearing years prior to pregnancy involves risk of blame for compromising a developing fetus because of side effects of the vaccination. In this context it should be emphasized that subunit vaccines based on purified protein or non-CMV viral vectors such as MVA have the potential to elicit antigen-specific immune responses that are quantitatively or qualitatively different from those induced by HCMV during natural infection. Such a subunit vaccine candidate may potentially provide protection in HCMV seronegative and seropositive individuals that exceeds the protection level afforded by naturally acquired HCMV immunity.

8. Five Year View