Abstract

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors may have therapeutic utility in multiple neurological and psychiatric disorders, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Here, we identify BRD4, a BET bromodomain reader of acetyl-lysine histones, as an essential component involved in potentiated expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and memory following HDAC inhibition. In in vitro studies, we reveal that pharmacological inhibition of BRD4 reversed the increase in BDNF mRNA induced by the class I/IIb HDAC inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA). Knock-down of HDAC2 and HDAC3, but not other HDACs, increased BDNF mRNA expression, whereas knock-down of BRD4 blocked these effects. Using dCas9-BRD4, locus-specific targeting of BRD4 to the BDNF promoter increased BDNF mRNA. In additional studies, RGFP966, a pharmacological inhibitor of HDAC3, elevated BDNF expression and BRD4 binding to the BDNF promoter, effects that were abrogated by JQ1 (an inhibitor of BRD4). Examining known epigenetic targets of BRD4 and HDAC3, we show that H4K5ac and H4K8ac modifications and H4K5ac enrichment at the BDNF promoter were elevated following RGFP966 treatment. In electrophysiological studies, JQ1 reversed RGFP966-induced enhancement of LTP in hippocampal slice preparations. Last, in behavioral studies, RGFP966 increased subthreshold novel object recognition memory and cocaine place preference in male C57BL/6 mice, effects that were reversed by cotreatment with JQ1. Together, these data reveal that BRD4 plays a key role in HDAC3 inhibitor-induced potentiation of BDNF expression, neuroplasticity, and memory.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Some histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors are known to have neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing properties, but the underlying mechanisms have yet to be fully elucidated. In the current study, we reveal that BRD4, an epigenetic reader of histone acetylation marks, is necessary for enhancing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and improved memory following HDAC inhibition. Therefore, by identifying novel epigenetic regulators of BDNF expression, these data may lead to new therapeutic targets for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords: BDNF, BET, BRD4, bromodomain, HDAC3, JQ1

Introduction

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a key mediator of multiple facets of brain function, including neurodevelopment, synaptic structure, neurotransmitter release, and learning and memory (Hofer and Barde, 1988; Falkenberg et al., 1992; Poo, 2001; Tyler and Pozzo-Miller, 2001; Yamada et al., 2002; Koppel and Timmusk, 2013; Harward et al., 2016). The BDNF gene locus includes nine distinct promoter regions that regulate expression of ∼20 transcripts, all of which contain a 3′-coding exon (IX) that yields the BDNF protein (Liu et al., 2006; Aid et al., 2007; Pruunsild et al., 2007). Differential expression of BDNF mRNA variants determines the spatial and temporal localization and activity of BDNF (Lauterborn et al., 1996; Nanda and Mack, 1998), which influences neuroplasticity and cognitive performance (Sakata et al., 2013). Despite the long-established link between impaired expression of BDNF and the pathogenesis of multiple neurological and psychiatric disorders, mechanisms that control BDNF expression are not completely understood. Therefore, to identify new therapeutic avenues for disease treatment, a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory factors that enhance BDNF expression is needed.

Preclinical and clinical evidence indicate that environmental factors such as stress, pharmacological agents, and exercise alter BDNF expression via epigenetic mechanisms (Karpova, 2014). On the N-terminal tail of each histone subunit, multiple sites exist for potential posttranslational modifications that include but are not limited to acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination (Borrelli et al., 2008). For example, on a histone tail, acetyl groups are erased by histone deacetylases (HDACs), added by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), and read by bromodomain proteins. In recent years, nonselective HDAC inhibitors (HDACis) such as valproic acid, sodium butyrate, trichostatin A, and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) have been shown to have neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing properties and these beneficial effects are mediated in part by increasing BDNF expression (Guan et al., 2009; Intlekofer et al., 2013; Koppel and Timmusk, 2013; Croce et al., 2014; Fukuchi et al., 2015). However, the regulation of BDNF by specific HDAC isoforms and the contribution of other epigenetic modifiers to HDACi-mediated expression of BDNF remain unclear.

Previously, we found that inhibition of bromodomain containing protein 4 (BRD4), a member of the bromodomain and extraterminal domain (BET) family of acetyl-lysine reader proteins, reduced BDNF mRNA and protein expression and reward-related learning (Sartor et al., 2015). Because HDAC inhibition is known to increase histone acetylation at the BDNF promoter (Bredy et al., 2007; Koppel and Timmusk, 2013) and because BET proteins are readers of histone acetylation (Filippakopoulos et al., 2010), we hypothesized that BET proteins are involved in the increased BDNF expression and memory following HDAC inhibition. Using molecular, pharmacological, electrophysiological, and behavioral techniques, we show that BRD4 plays a key role in the enhancement of BDNF expression, neuroplasticity, and memory following HDAC3 inhibition.

Materials and Methods

Drugs.

For in vitro studies, class I/IIb HDAC inhibitor SAHA (Tocris Bioscience), HDAC3-specific inhibitor RGFP966 (Cayman Chemical), or BET inhibitor JQ1 (James Bradner laboratory at Dana-Farber), was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and administered at 0.1% v/v. In in vivo studies, JQ1 or RGFP966 was dissolved in 10% DMSO and 10% Tween 80 (v/v) and then diluted with PBS; 10 mg/kg RGFP966 and/or 25 mg/kg JQ1 was administered intraperitoneally at a volume of 0.08–0.1 ml. Vehicle was delivered at the same volume as the JQ1/RGFP966 solution. Cocaine HCl (National Institutes of Health's National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program) was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline and administered by an intraperitoneal injection.

Animals.

Male C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks old; Charles River Laboratories) and Fisher 344 rats (∼12–16 weeks old; Taconic) were grouped housed under a regular 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle and had ad libitum access to food and water. For primary neuron experiments, a pregnant female rat (Sprague Dawley; Charles River Laboratories) carrying embryonic day 18 (E18) embryos was single housed with ad libitum access to food and water. Animals were housed in a humidity- and temperature-controlled; AAALAC-accredited, animal facility. Electrophysiological studies with male Fisher 344 rats (∼3 months old) were conducted at the University of Florida and all other animal studies were performed at the University of Miami's Miller School of Medicine. All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee before experimentation and conducted according to guidelines established by the U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Cell culture.

HEK-293 cell lines (ATCC) were maintained in Advanced Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% Primocin. SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% Primocin. In a 6-well plate, ∼400,000 cells were plated and treated 24 h later with DMSO (vehicle), SAHA (1 μm), RGFP966 (10 μm), JQ1 (1 μm), or a combination of SAHA (1 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm) or RGFP966 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm) for 15 min, 1 h, 4 h, 24 h, or 48 h. Primary rat hippocampal neurons were collected at E18–E19, plated on a poly-d-lysine- and laminin-coated plate, and maintained in NbActiv4 media (BrainBits) as described previously (Al-Ali et al., 2016). At 6 d in vitro (DIV), ∼200,000 primary hippocampal neurons were treated for 48 h with DMSO, RGFP966 (10 μm), or RGFP966 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm). The doses for all experiments were chosen based on our previous unpublished data showing that the selected concentrations were not toxic to cells at the time points measured. Cells were harvested for RNA and/or protein analysis as described below.

Neural stem cells (NSCs) were isolated from human fetal brain and cultured as described previously (Magistri et al., 2015, 2016a). In short, brain tissue was dissociated into single cells and then seeded in 75 mm tissue culture flasks with neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, 21103049) supplemented with EGF (20 ng/ml; Invitrogen, PHG0311), FGF (10 ng/ml; Invitrogen, PHG6015), B27 (Thermo Scientific, 12587010), Glutamax (Invitrogen, 35050061), and heparin (2 μg/ml) (Calbiochem, 375095). Following 7–10 d in culture, NSCs formed free-floating neurospheres. To differentiate into neurons, cultured neurospheres were disaggregated into single cells using StemPro Accutase cell dissociation reagent (Invitrogen, A1110501). Approximately 70,000 cells were plated in each well of 8-well glass chamber slides (Sigma-Aldrich, PEZGS0816) coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, P5899-5MG) and laminin (Sigma-Aldrich, L2020-1MG). The differentiation medium consisted of DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, 11320033) supplemented with N2 (1%) (Invitrogen, 17502048), MEM nonessential amino acids (1%) (Invitrogen, 11140050), and heparin (2 μg/μl; Calbiochem, 375095) and containing B-27 (Thermo Scientific, 12587010), antibiotic–antimycotic (Invitrogen, 15240062), Retinoic Acid (1 mm; Sigma-Aldrich, R2625), GDNF (10 μg/μl; PeproTech, 450-10), BDNF (10 μg/μl; PeproTech, 450-02), and l-ascorbic acid (10 μg/μl; Sigma-Aldrich, A92902-25G). After 5 d in culture, differentiated cells were then treated for 24 h with DMSO, RGFP966 (10 μm), or RGFP966 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm). Following treatment, immunostaining was performed as described below.

RNA interference.

In HEK-293 and SH-SY5Y cells, the depletion of HDAC and BRD4 expression was achieved by transient transfection of control siRNA (Qiagen, SI03650318), HDAC1-siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich, SASI_Hs01_00079968), HDAC2-siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich, SASI_Hs01_00142115), HDAC3-siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich, SASI_Hs01_00136351), HDAC6-siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich, SASI_Hs01_00048982), HDAC8-siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich, SASI_Hs01_00103586), HDAC10-siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich, SASI_Hs01_00150512), or BRD4-siRNA (Ambion, siBRD4-s23901) at 20 nm for 48 h using lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Knock-down was assessed by qRT-PCR.

CRISPR-dCas9.

To generate stable cell lines that express dCas9-BRD4, ∼200,000 HEK-293 cells per well were seeded in a 6-well plate in DMEM + 10% FBS medium with no antibiotic. After 24 h, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000CD (Life Technologies) in Opti-MEM and 3 μg of the dCas9-BRD4 plasmid (VectorBuilder, VB170323–1070scm). In this plasmid, dCas9 was conjugated to BRD4 (aa 1–722). This amino acid sequence was previously shown to be necessary for BRD4-mediated gene regulation and did not induce toxicity when expressed in cells (Rahman et al., 2011). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing the selection antibiotic blasticidin (1:200 concentration). Individual colonies were transferred to a 24-well plate and cells were validated for dCas9 expression using qRT-PCR. Following selection, cells were maintained in medium containing 1:500 of blasticidin. Next, stable cell lines expressing dCas9-BRD4 were transfected with gRNAs (3 pooled gRNAs for each target, 18 pmol) targeting promoters of hBDNF exon I (GGGCAACTAGTGGCTCGCCTTGG, CTCGAGAGCTCGGCTTACACAGG, AACTCAGCCGC TCGAGAGCTCGG), hBDNF exon IV (TCATATGACAGCGCACGTCAAGG, TATTAGAAGAGTTCCGTTCCAGG, AACCCTTTTAATAACGAACCAGG), hBDNF exon IX (CTGCATTCTGACCTATTGACTGG, GCAACCTACCTCCAGTCAATAGG, CATTCTGAC CTATTGACTGGAGG) or a scrambled control gRNA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific, TrueGuide A35506). gRNAs were designed using Broad Institute website (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gpp/public/analysis-tools/sgrna-design) and sequences selected had scores >95% to ensure low off-target effects. As an additional control, HEK-293 cells without dCas9-BRD4 were treated with the same gRNAs for hBDNF exon I, hBDNF exon IV, or hBDNF exon IX. Additional cells were treated with only transfection reagents (blank). After 36 h of treatment, cells were harvested and RNAs isolated for subsequent analysis by qRT-PCR.

ChIP.

In a 10 cm dish, ∼5 million SH-SY5Y cells were treated for 4 h with DMSO, RGFP966 (10 μm), or RGFP966 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm). Our prior experiments determined that this time point was the earliest to induce a robust increase in BDNF mRNA expression following RGFP966 treatment. Proteins were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, quenched with 1.25 m glycine, and then washed 3 times in cold PBS. Chromatin was subsequently sheared using Covaris S-series sonicator (3 cycles of 55 s on, 10 s off at the setting of 10% duty cycle, intensity of 5, 200 cycles, acoustic power 18 W at a temperature of 5°C). Samples were sonicated to a size of 200–500 base pairs as confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and stored at −80°C until ready for further analysis. ChIP dilution buffer was added to each sample (1 million cells per ChIP) and 2% of each sample was saved as input. The remaining sample was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 20 μl of magnetic Protein G Dynabeads (Thermo Scientific, 10004D) to quench nonspecific binding. Next, samples were placed on a magnet to remove beads, and incubated overnight (∼16 h) at 4°C on rotation with 5 μg of ChIP-validated rabbit anti-BRD4 (Active Motif, 39909, lot 13912002), anti-H4K5ac (Active Motif, 61489, lot 30113001), or rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, 2729S, lot 6) antibody conjugated to magnetic beads. Samples were washed with 700 μl of low-salt (twice), high-salt, LiCl, and TE (twice) buffers as described previously (Sartor et al., 2015). Cross-links were reversed by incubating the samples for 3 h at 65°C shaking at 1400 rpm. Proteinase K (40 μg; Roche Diagnostics) was added to each sample and incubated at 42°C for 1.5 h. DNA from each sample was extracted using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following ChIP primers were used: BDNF PI: forward, 5′-TCACGACCTCATCGGCTGGA-3′; reverse, 5′-GACGACTAACCTCGCTGTTT, BDNF PIV forward, 5′-CTGGTAATTCGTGCACTAGAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CACGAGAGGGCTCCACGG T-3′, BDNF PIX forward, 5′-CACTTGCAGTTGTTGCTTA-3′; reverse, 5′-GGCTTCAAGTTCTCCTTCTTCCCA-3′. Percentage of input was calculated for the ChIP and IgG samples and then the fold enrichment was calculated as a ratio of the ChIP to IgG.

qRT-PCR.

In cell culture experiments, the medium was aspirated and 1 ml of TRIzol was added to each well. For in vivo experiments, the mouse hippocampus was collected 2 h after intraperitoneal vehicle, RGFP966, and RGFP966 + JQ1 injections and tissue was homogenized in 1 ml of TRIzol. RNEasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) was used for RNA extraction according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Scientific). Using validated TaqMan primer probes for BDNF (Thermo Scientific, Hs03298540_m1, Rn02531967_s1, or Mm04230607_s1), HDAC1 (Hs02621185_s1), HDAC2 (Hs00231032_m1), HDAC3 (Hs00187320_m1), HDAC6 (Hs00997427_m1), HDAC8 (Hs00954353_g1), and HDAC10 (Hs00368899_m1), cDNA was run in triplicate and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method with β-actin (Hs01060665_g, Rn00667869_m1, or Mm02619580_g1) or GAPDH (Hs02786624_g1, Rn01775763_g1, or Mm99999915_g1) as a normalization control. The housekeeping gene selected for normalization was unchanged between treatments. Cas9 was measured using a custom TaqMan primer/probe (Integrated DNA Technologies, 5′-CCACCACCAGCACAGAATAG-3′ 5′-CCCAAGAGGAACAGCGATAAG-3′, 56-FAM ATCGCCAGA ZEN AAGAAGGACTGGGAC 3IABkFQ). SYBR green (Thermo Scientific) qRT-PCR was performed to measure specific BDNF transcripts with the following validated primers: BDNF exon I (forward, 5′-AACAAGACACATTACCTTCCAGCAT-3′; reverse, 5′-CTCTTCTCACCTGGTGGAACATT-3′), BDNF exon II (forward, 5′-TGGTATACTGGGTTAACTTTGGGAAA-3′; reverse, 5′-CACTCTTCTCACCTGGTGGAACTT-3′) and BDNF exon IV (forward, 5′-GCTGCCTTGATGTTTACTTTGA-3′; reverse, 5′-GCAACCGAAGTATGAAATAACC-3′) (Kairisalo et al., 2009; Koppel and Timmusk, 2013).

Histone extractions.

Core histones were purified from HEK-293 or SH-SY5Y using a Histone Purification Mini Kit (Active Motif, 40026) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, ∼5 million cells were grown in 10 cm dish and, after 4 h of treatment with DMSO, RGFP966 (10 μm), or RGFP966 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm), medium was discarded and cells were washed twice with PBS and then collected in ice-cold extraction buffer. Following treatment with equilibration buffer, the remaining crude histone extract was passed through the column, washed three times, and eluted. Histones were precipitated overnight with 4% perchloric acid and then centrifuged and washed with 4% perchloric acid and acetone. Purified histones were resuspended in water and quantified according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then, 10 μg of histone was loaded into a precast 4–20% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) for electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Following transfer, the membrane was incubated in Ponceau S solution to visualize total histones. Total histones were imaged using FluorChem E (ProteinSimple) and quantified as a loading control for H3ac, H4K5ac, and H4K8ac Western blots as described below.

Western blots.

For nonhistone samples, cells were lysed using mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER, Thermo Scientific) with HALT proteinase inhibitor mixture (Thermo Scientific). Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) kit (Thermo Scientific) and 30 μg of total protein was loaded into precast 4–20% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) for electrophoresis. Protein samples were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked for 30 min in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 5% BSA (Bio-Rad). Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer with anti-acetyl-tubulin (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 5334), H4K5ac (1:1000; Active Motif, 61523), H4K8ac (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 2594) or anti-acetyl-lysine (1:1000; Millipore, AB3879). After three washes in TBS, membranes were incubated in their respective HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 7074) in blocking buffer. Acetyl-tubulin was normalized to GAPDH (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 2118S). Blots for histone marks were normalized to total histone. Densitometry of protein bands at the appropriate molecular weight were measured using ImageJ.

BDNF ELISA.

In a 12-well plate, ∼300,000 rat primary hippocampal neurons (DIV 6) were treated with DMSO (vehicle), RGFP966 (10 μm), or RGFP966 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm) for 48 h. Cells were collected, pelleted, and lysed with M-PER supplemented with HALT proteinase inhibitors. BDNF proteins were measured with the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific, ERBDNF). BDNF was normalized to the total protein concentration of each sample using a BCA kit (Thermo Scientific).

Immunocytochemistry.

Differentiated neural stem cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min. After washing two times with PBS, cells were incubated for 1 h in buffer containing 2% Triton X-100, 20% goat serum, NaCl (150 mm), Tris base (50 mm), BSA (1%), l-lysine (100 mm), and sodium azide (0.04%), pH 7.4. Next, cells were incubated with primary antibodies, anti-β-tubulin III (1:200) (Thermo Scientific, MA1–118X) and H4K5ac (1:500; Active Motif, 61523) overnight at 4°C. After two washes with PBS, cells were incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500; Invitrogen, R37117) and Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; Invitrogen, A-11001). After two washes with PBS, cells were incubated in a mounting medium containing DAPI (Thermo Scientific, S36964). Using a LSM 710 confocal microscope equipped with ZEN 2010 B SP1 software (Zeiss), images were collected with a 20× objective using identical acquisition exposure time conditions. At least two different fields within each sample were imaged and averaged. Fiji image analysis software (ImageJ 1.51u) was used to quantify fluorescent intensity by an experimenter blinded to the treatment conditions.

Electrophysiology.

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and rapidly decapitated. Brains were removed and hippocampal slices prepared as described previously (Bodhinathan et al., 2010; Kumar, 2010; Kumar and Foster, 2013, 2014; Kumar et al., 2018). Briefly, dissected hippocampi were sectioned parallel to the alvear fibers (∼400 μm) using a tissue chopper and immediately transferred to a holding chamber with continuous perfusion of artificial CSF (aCSF) containing the following: NaCl (124 mm), KCl (2 mm), KH2PO4 (1.25 mm), MgSO4(2 mm), CaCl2 (2 mm), NaHCO3 (26 mm), and glucose (10 mm). To ensure physiological pH (7.4) and oxygenation of aCSF, slices were maintained at 30°C with bubbling (95% O2, 5% CO2). For electrophysiological recordings, slices were transferred to a temperature-controlled (30°C) interface chamber inside a Faraday cage and infused with oxygenated aCSF with vehicle (DMSO), RGFP966 (10 μm), or RGFP966 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm). Following the 60 min recovery and drug incubation period, extracellular postsynaptic field potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded within the stratum radiatum using a glass micropipette filled with aCSF flanked (∼1 mm) by 2 stimulating electrodes (1–3 MΩ). This configuration allows for independent pathways that are used to monitor slice health (control path) and synaptic modification (test path). To monitor synaptic transmission in each pathway during a 10 min baseline period and for 60 min following induction of LTP, a single biphasic stimulus pulse (100 μs) was applied in an alternating manner to induce field potentials at a frequency of 0.033 Hz. LTP was induced in the test path by high-frequency stimulation (HFS: 2 episodes of 100 pulses at 100 Hz with a 1 s inter-episode latency). The LTP induction protocol was based on previous studies indicating impaired induction of LTP in BDNF mutant mice (Korte et al., 1995; Patterson et al., 1996). Changes in synaptic transmission properties were assessed by computing the maximum slope of the descending fEPSP waveform (in millivolts per millisecond). The percentage change in response rates was computed by normalizing values at 55–60 min following induction of LTP to baseline levels.

Novel object recognition (NOR).

For the NOR test, we adapted the subthreshold NOR protocol as described previously (Stefanko et al., 2009; Malvaez et al., 2013). On days 1–3, mice were allowed to freely explore an open-field chamber without any objects for 5 min per day. On day 4, mice were exposed to 2 identical objects for 3 min. The 3 min exposure has been shown to be a subthreshold training, whereas in longer training (e.g., 10 min exposure), the mouse can sufficiently discriminate novel from familiar object on test day. Immediately following the 3 min exposure to two identical objects, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of vehicle, RGFP966 (10 mg/kg), or RGFP966 (10 mg/kg) + JQ1 (25 mg/kg) and were placed back in their home cage. The next day, mice were tested in a 5 min retention trial with one familiar object and one novel object. The location of the objects (a stack of Legos or a 100 ml glass beaker) were counterbalanced for left and right position in each treatment group. Objects and open field were thoroughly cleaned with 70% ethanol after each trial. Total time spent investigating and facing each object within 1.5 cm was recorded and analyzed by Ethovision tracking software (Noldus). A discrimination index defined as [(novel object investigation time minus familiar object investigation time)/(total investigation time of both objects) * 100] was calculated and reported in the Results section. Locomotor behavior was also recorded for 30 min in an open field following vehicle and RGFP966 (10 mg/kg, i.p.) + JQ1 (25 mg/kg, i.p.) administration.

Conditioned place preference (CPP).

The CPP apparatus consisted of two compartments with distinct visual (black vs black/white striped walls) and tactile (bars vs grid floors) cues. The compartments were separated by a divider with a small door that could be opened or closed. In a pretest acclimation session, mice were allowed to freely explore both compartments for 15 min via an opening in the partition. The time spent on each side of the CPP chamber was recorded via EthoVision tracking software. Groups were organized such that mean baseline pretest scores were not different between treatments. A subthreshold cocaine conditioning protocol was used in which mice received a single 30 min conditioning session. During conditioning one side of the chamber was paired with a saline injection and the other side was paired with a cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) injection. The conditioning sessions were 4 h apart with the saline conditioning occurring in the morning and cocaine conditioning occurring in the afternoon. Immediately following cocaine conditioning, mice received an injection of vehicle, RGFP966 (10 mg/kg), or RGFP966 (10 mg/kg) + JQ1 (25 mg/kg) and were then placed back in their home cage. The next day, mice received a drug-free CPP test where they had free access to each side of the chamber.

Data analysis.

GraphPad Prism 7.0 software was used for graph preparation and statistical analyses, and figures were formatted using Adobe Illustrator CC. Mean values from behavioral studies, densitometric data from Western blots, and Rq values from qRT-PCR experiments were compared between groups using ANOVA or Student's t test. When a significant F-value was obtained, comparisons were performed by post hoc analysis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and the level of significance was set to p < 0.05.

Results

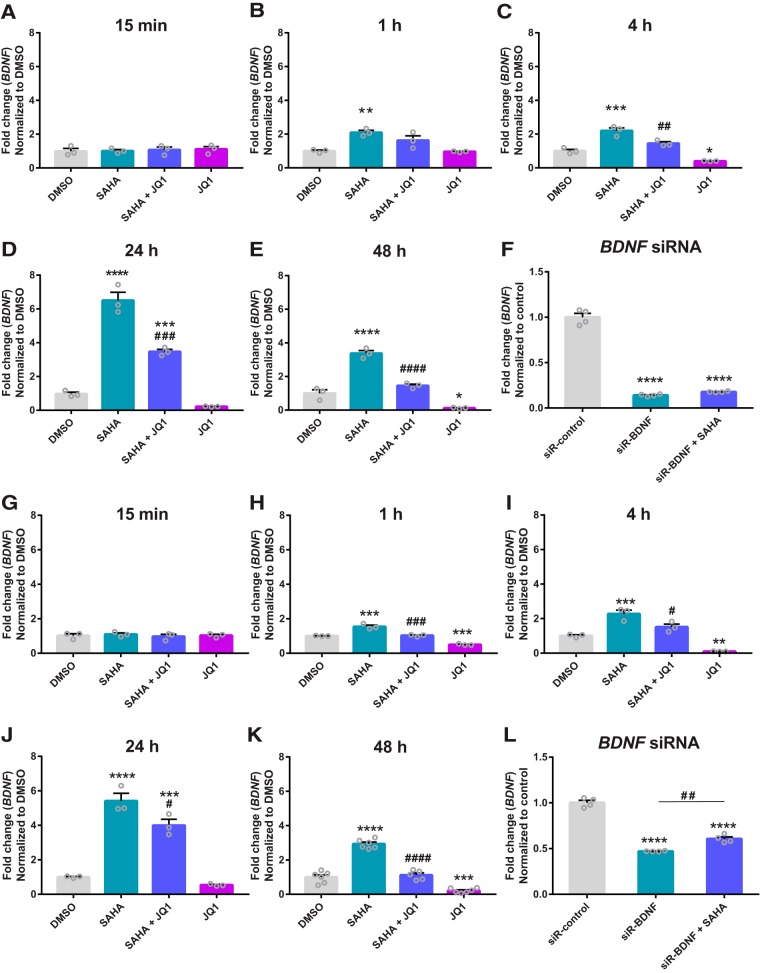

Elevated expression of BDNF mRNA by SAHA is attenuated by JQ1 in a time-dependent manner

To determine whether BET proteins are necessary for increased BDNF mRNA expression following HDAC inhibition, HEK-293 and SH-SY5Y cells were treated with DMSO (vehicle), SAHA (1 μm), JQ1 (1 μm), or a combination of SAHA (1 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm) for 15 min, 1 h, 4 h, 24 h, or 48 h. The class I/IIb HDAC inhibitor SAHA, a clinically approved medication, was chosen because of its previously established role as an enhancer of memory and BDNF expression (Guan et al., 2009; Koppel and Timmusk, 2013). SAHA robustly increased BDNF mRNA expression following 1, 4, 24, and 48 h of treatment, but not following 15 min treatment in both HEK-293 cells (Fig. 1A–E) and SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1G–K) (one-way ANOVA in HEK-293 cells: F(3,8) = 0.14, p = 0.9 at 15 min; F(3,8) = 12.78, p = 0.002 at 1 h; F(3,8) = 46.8, p < 0.0001 at 4 h; F(3,8) = 121.9, p < 0.0001 at 24 h; F(3,8) = 90.9, p < 0.0001 at 48 h; one-way ANOVA in SH-SY5Y cells: F(3,8) = 0.28, p = 0.8 at 15 min; F(3,8) = 72.4, p < 0.0001 at 1 h; F(3,8) = 43.8, p < 0.0001 at 4 h; F(3,8) = 69.6, p < 0.0001 at 24 h; F(3,19) = 117.3, p < 0.0001 at 48 h). Interestingly, the BET inhibitor JQ1 attenuated SAHA-induced increases in BDNF mRNA following 4 h or longer treatment in HEK-293 cells and 1 h or longer treatment in SH-SY5Y cells (p < 0.05 for SAHA vs SAHA + JQ1 via post hoc analysis). JQ1 alone reduced BDNF mRNA expression compared with DMSO beginning at 4 h in HEK-293 cells and 1 h in SH-SY5Y cells (p < 0.05 for DMSO vs JQ1 via post hoc analysis). As a control, HEK-293 cells (Fig. 1F) and SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1L) were treated with BDNF siRNA (siR-BDNF), BDNF siRNA (siR-BDNF) + SAHA (1 μm), or scrambled control siRNA (siR-control) and, as expected, BDNF siRNA attenuated BDNF mRNA expression following SAHA treatment (one-way ANOVA: F(2,9) = 404.9, p < 0.0001 in HEK-293 cells; F(2,9) = 210.8, p < 0.0001 in SH-SY5Y cells).

Figure 1.

JQ1 blocks SAHA-induced enhancement of BDNF mRNA expression. A–E, BDNF mRNA expression in HEK-293 cells that were treated with DMSO (vehicle), SAHA (1 μm), JQ1 (1 μm), or a combination of SAHA (1 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm) for 15 min, 1 h, 4 h, 24 h, or 48 h. F, BDNF mRNA expression in HEK-293 cell following 48 h treatment with control siRNA (siR-control), BDNF siRNA (siR-BDNF), or a combination of SAHA + BDNF siRNA. G–K, BDNF mRNA expression in SH-SY5Y cells that were treated with DMSO (vehicle), SAHA (1 μm), JQ1 (1 μm), or a combination of SAHA (1 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm) for 15 min, 1 h, 4 h, 24 h, or 48 h. L, BDNF mRNA expression in SH-SY5Y cells following 48 h treatment with control siRNA (siR-control), BDNF siRNA (siR-BDNF), or a combination of SAHA + BDNF siRNA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 compared with DMSO or siR-control via Tukey's post hoc analysis, #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001; ####p < 0.0001 compared with SAHA or siR-control via post hoc analysis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3–6.

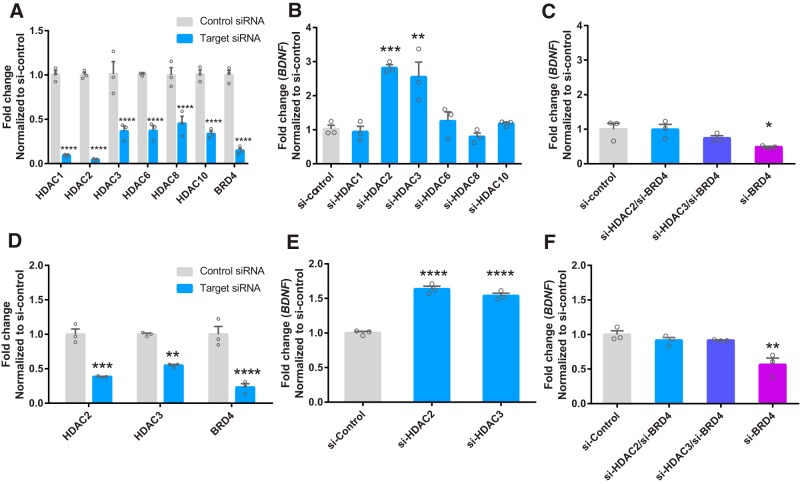

Increased BDNF by siRNA-mediated knock-down of HDAC2 and HDAC3 is blocked by BRD4 knock-down

Because SAHA is a class I (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC8) and IIb (HDAC6 and HDAC10) inhibitor, we next sought to identify which of these HDACs regulate BDNF mRNA expression. HEK-293 cells were treated for 48 h with siRNAs for class I/IIb HDACs or scrambled control siRNA and knock-down was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2A, two-way ANOVA main effect for treatment: F(1,28) = 562.6; p < 0.001; main effect for gene: F(6,28) = 3.744, p = 0.007; interaction: F(6,28) = 3.605, p = 0.009). In Figure 2B, BDNF mRNA expression was increased by HDAC2 and HDAC3 siRNA treatment, but not by other HDAC siRNAs tested (F(6,14) = 14.5, p < 0.0001). Because we have previously shown that BRD4 is necessary for BDNF mRNA expression (Sartor et al., 2015), we next sought to determine whether BRD4 knock-down would block the increase in BDNF caused by HDAC2/3 knock-down. In Figure 2C, BRD4 siRNA attenuated the increase in BDNF mRNA mediated by HDAC2 or HDAC3 siRNA in HEK-293 cells, and BRD4-siRNA alone significantly decreased BDNF expression compared with control (F(3,8) = 4.2, p = 0.046). In SH-SY5Y cells, HDAC2 and HDAC3 knock-down (Fig. 2D) increased BDNF mRNA (Fig. 2E, F(2,6) = 101, p < 0.0001) and BRD4-siRNA reversed these effects (Fig. 2F) (Fig. 2F, F(3,8) = 11.0, p = 0.003), which is consistent with the results that we observed in HEK-293 cells.

Figure 2.

BRD4 is necessary for the increase in BDNF mRNA following knock-down of HDAC2 and HDAC3. A, siRNA-mediated knock-down of class I/IIb HDACs and BRD4 (48 h) in HEK293 cells. B, BDNF mRNA expression following knock-down of class I/IIb HDACs in HEK-293 cells. C, Expression of BDNF mRNA following siRNA-mediated knock-down of HDAC2/BRD4, HDAC3/BRD4, or BRD4 in HEK-293 cells. D, siRNA-mediated knock-down of HDAC2, HDAC3, and BRD4 (48 h) in SH-SY5Y cells. E, BDNF mRNA expression following HDAC2, HDAC3 knock-down compared with control siRNA in SH-SY5Y cells. F, Expression of BDNF mRNA following siRNA-mediated knock-down of HDAC2/BRD4, HDAC3/BRD4, or BRD4 in SH-SY5Y cells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 indicates a significant difference compared with si-control via Bonferroni's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3.

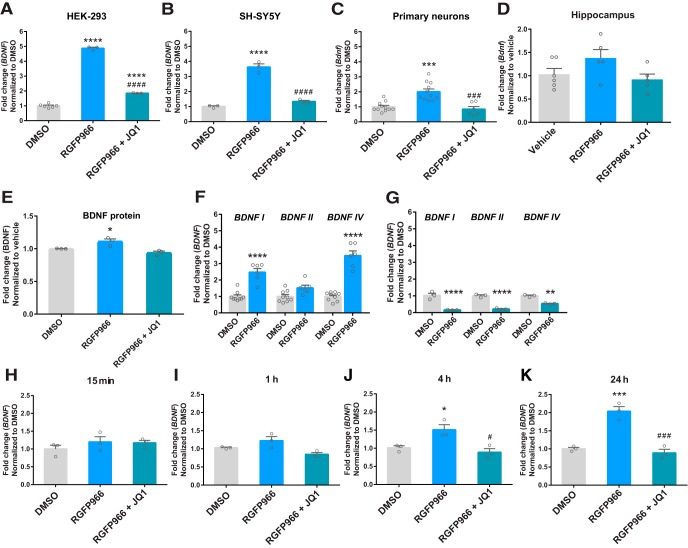

RGFP966-mediated increases in BDNF expression is blocked by JQ1

Because HDAC2-specific inhibitors are not commercially available, we next focused on pharmacological inhibition of HDAC3. Previous studies have shown that the HDAC3-specific inhibitor RGFP966 facilitates memory consolidation and encoding (McQuown et al., 2011; Bieszczad et al., 2015), but its ability to regulate BDNF expression is unclear. Here, we found that RGFP966 increases BDNF mRNA in HEK-293 cells (Fig. 3A), SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 3B), and hippocampal primary neurons (Fig. 3C), effects that were attenuated by cotreatment with JQ1 (HEK-293 cells: F(2,9) = 1235, p < 0.0001; SH-SY5Y cells: F(2,6) = 113.6, p < 0.0001; primary neurons: F(2,25) = 17.1, p < 0.0001). A small but significant increase in BDNF protein was also found in hippocampal primary neurons following 48 h of treatment with RGFP966 (F(2,6) = 11.42, p = 0.009, Fig. 3E) and JQ1 attenuated this effect. In mice, acute systemic administration of RGFP966 lead to a 38% increase in hippocampal Bdnf expression, but this effect was not statistically significant (F(2,13) = 2.7, p = 0.10, Fig. 3D). Next, we measured specific Bdnf transcripts in hippocampal primary neurons following treatment with RGFP966 (Fig. 3F) or JQ1 (Fig. 3G). We chose to measure transcripts containing Bdnf exons I, II, and IV because of their established role in different types of learning and memory (Kumar et al., 2005; Bredy et al., 2007; Lubin et al., 2008; Schmidt et al., 2012). RGFP966 treatment significantly increased expression of Bdnf I and IV transcripts (two-way ANOVA: main effect for treatment F(1,39) = 133.4, p < 0.0001; main effect for gene F(2,39) = 19.25, p < 0.0001; interaction F(2,39) = 19.25, p < 0.0001), whereas JQ1 reduced Bdnf I, II, and IV transcripts (two-way ANOVA: main effect for treatment F(1,12) = 195.6, p < 0.0001; main effect for gene F(2,12) = 4.923, p = 0.03; interaction F(2,12) = 5.644, p = 0.02). In time-dependent experiments (Fig. 3H–K), RGFP966 increased BDNF mRNA expression in SH-SY5Y cells at 4 and 24 h following treatment and JQ1 attenuated RGFP966-mediated increases in BDNF at 4 and 24 h of treatment (F(2,6) = 0.9, p = 0.45 at 15 min; F(2,6) = 7.1, p = 0.03 at 1 h; F(2,6) = 9.9, p = 0.01 at 4 h; F(2,6) = 41.1, p = 0.0003 at 24 h).

Figure 3.

RGFP966-induced potentiation of BDNF mRNA expression is blocked by JQ1. BDNF mRNA expression levels in HEK293 cells (A), SH-SY5Y cells (B), and primary neurons (C), mouse hippocampus (D), and BDNF protein in primary neurons (E) following vehicle, RGFP966, or RGFP966 + JQ1 treatment. F, G, Exon-specific BDNF transcript expression in primary neurons following RGFP966 (F) or JQ1 (G) treatments (48 h). H–K, Time-dependent BDNF mRNA expression in SH-SY5Y cells treated with DMSO (vehicle), RGFP966 (10 μm), or a combination of RGFP966 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm) for 15 min, 1 h, 4 h, or 24 h. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 indicates a significant difference from DMSO via Tukey's post hoc test. #p < 0.05; ###p < 0.001; ####p < 0.0001 indicates a significant difference from RGFP966 via Tukey's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

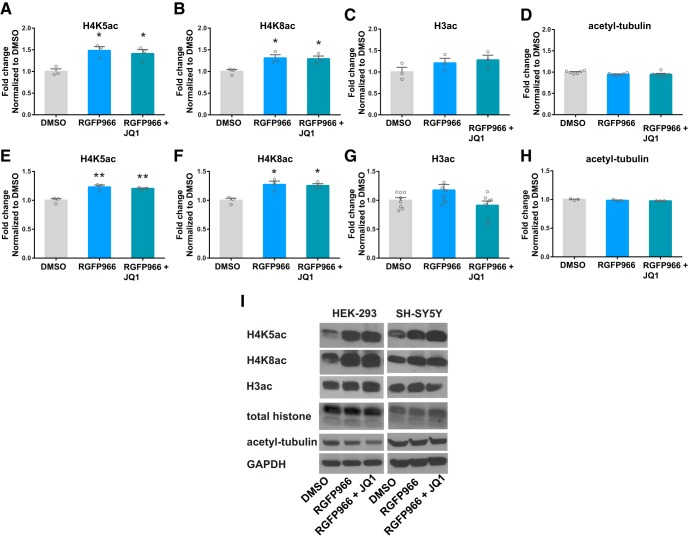

H4K5ac and H4K8ac are increased by RGFP966

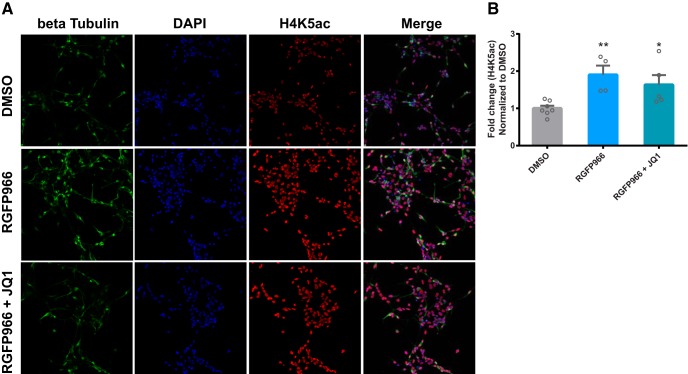

To determine whether histone acetyl-lysine modifications are altered by RGFP966 and JQ1 treatment, histone proteins were purified and H3ac, H4K5ac, and H4K8ac were measured (Fig. 4). These marks were chosen because they have been shown to be targets of HDAC3 and/or BRD4 (Bhaskara et al., 2010; McQuown et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012; Rogge et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014). Both H4K5ac (Fig. 4A,E,I) and H4K8ac (Fig. 4B,F,I) were significantly increased by RGFP966 and RGFP966 + JQ1 in both cell lines (HEK-293 cells: F(2,6) = 9.6, p = 0.01 for H4K5ac; F(2,6) = 7.5, p = 0.02 for H4K8ac; SH-SY5Y cells: F(2,6) = 21.8, p = 0.002 for H4K5ac; F(2,6) = 11.2, p = 0.009 for H4K8ac). However, H3 acetylation (Fig. 4C,G,I) and acetylated tubulin (Fig. 4D,H,I) were unchanged by RGFP966 and RGFP966 + JQ1 (HEK-293 cells: F(2,6) = 1.7, p = 0.3 for H3ac; F(2,15) = 3.3, p = 0.06 for acetyl-tubulin; SH-SY5Y cells: F(2,20) = 3.1, p = 0.07 for H3ac; F(2,6) = 3.2, p = 0.1 for acetyl-tubulin), indicating that RGFP966 does not alter all types of acetyl-lysine modifications. Consistent with the results in SH-SY5Y and HEK-293 cells, H4K5ac was also found to be elevated in differentiated human neural stem cells following RGFP966 and RGFP966 + JQ1 treatment (Fig. 5A,B) (F(2,13) = 6.7, p = 0.01).

Figure 4.

Effects of RGFP966 on histone modifications. A–D, RGFP966 treatment (10 μm, 4 h) increased H4K5ac and H4K8ac, but not total H3ac and acetyl-tubulin, in HEK293 cells. H4K5ac and H4K8ac modifications remained elevated following RGFP966 + JQ1 treatment. E–H, Similar to HEK-293 cells, RGFP966 treatment (10 μm, 4 h) elevated H4K5ac and H4K8ac, but not total H3ac and acetyl-tubulin in SH-SY5Y cells. I, Representative blot images of H4K5ac, H4K8ac, H3ac, total histone, acetyl-tubulin, and GAPDH in HEK-293 and SH-SY5Y following treatments with DMSO, RGFP966, and RGFP966 + JQ1. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 indicates a significant difference from DMSO via Bonferroni's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3–6.

Figure 5.

RGFP966 increases H4K5ac in neurons differentiated from human neural stem cells. A, Representative immunofluorescence staining of β tubulin, DAPI and H4K5ac following treatment with DMSO, RGFP966, or RGFP966 + JQ1 in differentiated human neurons. B, Quantification of fluorescent intensity of H4K5ac following treatment with DMSO, RGFP966, or RGFP966 + JQ1. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 indicates a significant difference from DMSO via Bonferroni's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 4–7.

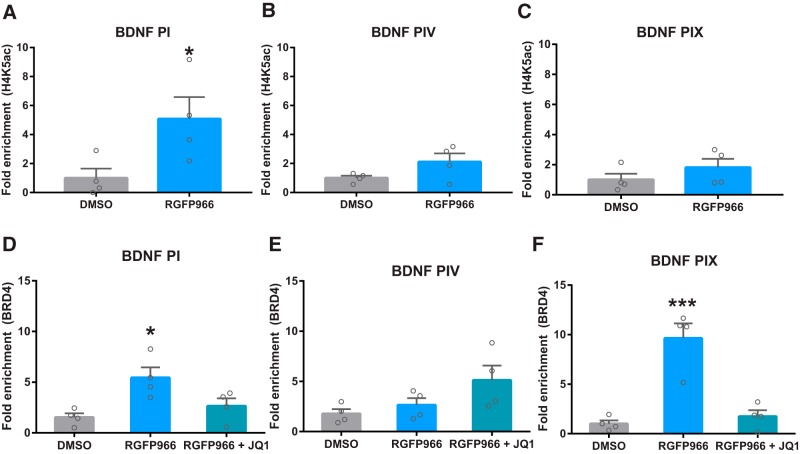

RGFP966 increases H4K5ac and BRD4 binding at the BDNF promoter

In ChIP-qRT-PCR experiments, RGFP966 increased H4K5 acetylation at the promoter of BDNF exon I (t6 = 2.5, p = 0.048), but not promoters of BDNF exon IV and IX (p > 0.05) in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 6A–C). In BRD4-ChIP experiments (Fig. 6D–F), RGFP966 increased binding of BRD4 to the promoters of BDNF exon I (F(2,9) = 6.8, p = 0.02) and IX (F(2,9) = 24.9, p = 0.0002) but not IV (F(2,9) = 3.2, p = 0.09). RGFP966-induced increases BRD4 enrichment at the BDNF I and IX promoters were blocked by cotreatment with JQ1 (p > 0.05 for DMSO vs RGFP966 + JQ1 in post hoc analysis).

Figure 6.

H4K5ac and BRD4 enrichment at the BDNF promoter following RGFP966 treatment. A–C, RGFP966 elevated H4K5ac at BDNF promoter I (A), but not promoters IV (B) and IX (C). D–F, BRD4 binding at the BDNF promoter I (D) and IX (F), but not IV (E), was increased by RGFP966. The increase in BRD4 binding to BDNF promoters I and IX was blocked by cotreatment with JQ1. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 indicates a significant difference from DMSO Bonferroni's post hoc test or Student's t test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 4.

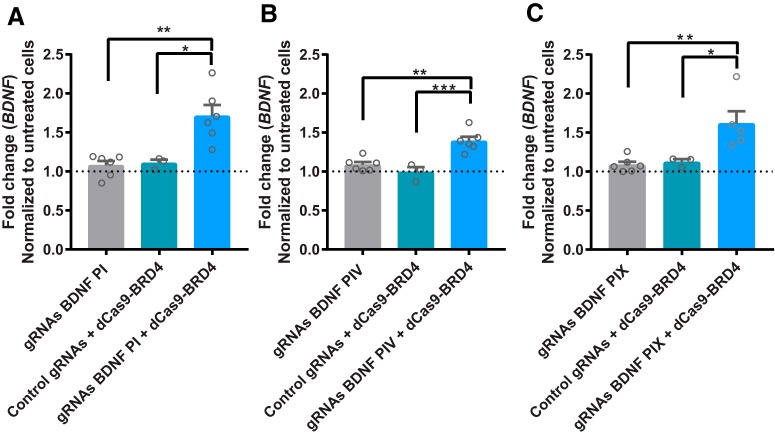

Locus-specific targeting of BRD4 to BDNF promoters increases BDNF mRNA expression

To determine whether binding of BRD4 to the promoter regions of BDNF in the absence of HDAC3i was sufficient to increase BDNF mRNA expression, cells were selected to stably express dCas9 conjugated to BRD4 (dCas9-BRD4). Cells were then treated with gRNAs that targeted BDNF promoter I, IV, or IX (Fig. 7). Compared with cells treated with a control gRNAs, BDNF mRNA was elevated in dCas9-BRD4 cells treated with BDNF gRNAs for promoters I, IV, or IX (promoter I: F(3,14) = 11.3, p = 0.0005; promoter IV: F(3,14) = 15.2, p = 0.0001; promoter IX: F(3,13) = 8.5, p = 0.001). However, treatment with only gRNAs for promoters I, IV, or IX did not alter BDNF mRNA expression compared with untreated cells or cells treated with control gRNAs + dCas9-BRD4 (p > 0.05 for gRNAs vs blank and for gRNAs vs control gRNAs + dCas9-BRD4). Therefore, these data indicate that BRD4 binding to BDNF promoters increases BDNF mRNA (∼1.5-fold increase), but to a lesser degree compared with cells treated with RGFP966 in prior experiments (∼3- to 4-fold increase in Fig. 3).

Figure 7.

Locus-specific targeting of BRD4 to the BDNF promoter. A–C, BDNF mRNA expression cells treated with gRNAs for BDNF promoters I, IV, or IX (gray bars); cells expressing dCas9-BRD4 treated with scrambled control gRNA (green bars); or cells expressing dCas-BRD4 treated with gRNAs for BDNF promoters I, IV, or IX (blue bars). Horizontal dotted line indicates baseline expression in untreated cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 indicates a significant difference compared with gRNA only or control gRNAs + dCas9-BRD4 via Tukey's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3–6.

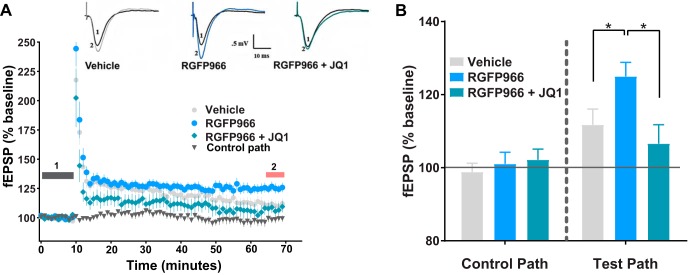

JQ1 attenuates RGFP966-induced enhanced LTP in rat hippocampal slices

Inhibition of HDAC3 by RGFP996 was previously shown to enhance LTP in hippocampal slices (Franklin et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2015). Here, we sought to determine whether BRD4 is required for the repressive effects of HDAC3 on LTP. To this end, fEPSPs were recorded in the stratum radiatum of rat hippocampal slices and LTP was induced by HFS (2 episodes of 100 pulses of 100 Hz). The percent change in fEPSP responses was computed 55–60 min after HFS relative to a 10 min baseline period in two pathways, a control pathway without HFS and a test pathway in which LTP was induced by HFS (Fig. 8A). We found that RGFP966 enhanced HFS-induced LTP compared with vehicle and that this enhancement was abolished by JQ1 (Fig. 8B, F(2,23) = 4.6, p = 0.02).

Figure 8.

JQ1 attenuates RGFP966-mediated enhancement of LTP. A, Time course of changes in the fEPSPs 10 min before and 60 min after HFS to induce LTP for slices exposed to vehicle (DMSO, gray circle, n = 9) or RGFP996 (10 μm, blue circle, n = 9), or RGFP996 (10 μm) + JQ1 (1 μm, green diamond, n = 8) and a control pathway; all other control pathways were stable (data not shown for clarity). Examples of EPSP traces illustrating LTP for the three different conditions at the indicated time points during baseline recording (1, black trace) and 60 min following induction of LTP (2, gray-vehicle, blue-RGFP966, green-RGFP966 + JQ1). B, Bar diagram showing the average magnitude of LTP during the last 5 min of recording [red bar in (2)]. *p < 0.05 via Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 8–9.

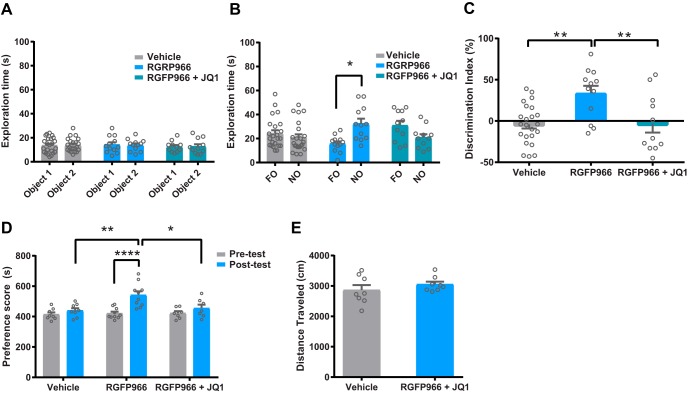

Enhancement of memory by RGFP966 is blocked by JQ1

To further investigate whether BET proteins are required for HDAC3-mediated memory enhancement, we interrogated rodent memory performance using two behavioral paradigms, subthreshold NOR and subthreshold CPP. During NOR training, no significant difference in exploration time was observed between groups (Fig. 9A, p > 0.05 via two-way ANOVA). During the test, however, time exploring the novel object (Fig. 9B) and discrimination index (Fig. 9C) were significantly increased by RGFP966 and these effects were blocked by cotreatment with JQ1 (two-way ANOVA for exploration time during testing: interaction effect F(2,86) = 8.464, p = 0.0004, but no group or object effect; one-way ANOVA for discrimination index: F(2,43) = 7.53, p = 0.0016). To determine whether similar effects by RGFP966 could be observed in subthreshold reward-related learning, mice received an injection of vehicle, RGFP966, or RGFP966 + JQ1 following a single cocaine pairing in the CPP procedure. Consistent with NOR results, RGFP966 enhanced subthreshold reward-context associated learning compared with vehicle and JQ1 blocked RGFP966-mediated increases in subthreshold cocaine CPP (Fig. 9D; two-way ANOVA: treatment effect F(2,44) = 5.458, p = 0.0076; group effect F(1,44) = 16.15, p = 0.0002; interaction effect F(2,44) = 4.752, p = 0.0135). There was no difference between groups in time spent in the cocaine-paired during CPP pretest. Previous reports have shown that RGFP966 and JQ1 alone do not alter locomotor behavior (Bowers et al., 2015; Korb et al., 2015; Sartor et al., 2015; Suelves et al., 2017). Compared with vehicle, we also found that locomotor behavior (distance traveled) was not significantly altered following RGFP966 + JQ1 treatment (Fig. 9E, t(14) = 1.02, p = 0.33).

Figure 9.

RGFP966-induced enhancement of memory is reversed by JQ1. A, Object exploration times during the 3 min subthreshold NOR training. B, Exploration times of the familiar object (FO) and novel object (NO) during the NOR test. C, Discrimination index values for vehicle-treated (n = 23), RGFP966-treated (n = 12), and RGFP966 + JQ1-treated (n = 11) groups. D, Time spent in the cocaine-paired side of the CPP chamber during pretest (gray) and posttest (blue) in vehicle-treated (n = 8), RGFP966-treated (n = 10), and RGFP966 + JQ1-treated (n = 7) groups. E, Locomotor activity (distance traveled) in mice treated with vehicle (n = 8) or RGFP966 + JQ1 (n = 8). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0. < 0.0001 via Tukey's post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Discussion

Enhanced expression of BDNF is a potential mediator of the therapeutic effects of HDAC inhibitors in animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders, but the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. Here, we revealed that the BET bromodomain reader protein BRD4 plays an important role in facilitating BDNF expression and neuroplasticity following HDAC inhibition. Specifically, we found that of the HDACs inhibited by SAHA, HDAC2 and HDAC3 are important negative regulators of BDNF expression because knock-down of HDAC2 or HDAC3 increased BDNF mRNA levels. The increased expression of BDNF by SAHA and HDAC2/HDAC3 siRNAs was blocked by the BET inhibitor JQ1 and BRD4 siRNA, respectively. In additional experiments using RGFP966, we revealed that pharmacological inhibition of HDAC3 elevated BDNF expression and binding of BRD4 to the BDNF promoter, an effect that was blocked by JQ1. Using gRNA-directed binding of dCas9-BRD4 to BDNF promoters, we revealed that BRD4 was sufficient to increase BDNF expression, but to a lesser degree than RGFP966. Examining histone modifications, RGFP966 increased H4K5ac and H4K8ac levels (both targets of BRD4) in cells and H4K5ac at the BDNF I promoter, but H3ac and acetylated tubulin were unchanged. Finally, JQ1 blocked RGFP966-induced enhancement of LTP in hippocampal slices and subthreshold memories in mice. Together, these data identify BRD4 as an essential factor for the potentiation of BDNF expression, neuroplasticity, and memory following HDAC3 inhibition.

In the current studies, we showed that HDAC2 and HDAC3 inhibition enhanced BDNF expression. Previous studies have also implicated these HDACs as important regulators of neuroplasticity and learning and memory (Mahgoub and Monteggia, 2014; Ganai et al., 2016). For example, HDAC3, the most highly expressed class I HDAC in the brain (Broide et al., 2007), has been shown to be a negative regulator or multiple types of memory, as evidenced by the enhancement of NOR (McQuown et al., 2011; Malvaez et al., 2013; Janczura et al., 2018), contextual fear conditioning (Kwapis et al., 2017), extinction of cocaine CPP (Malvaez et al., 2013; Rogge et al., 2013; Alaghband et al., 2017), auditory memory encoding (Bieszczad et al., 2015), and instrumental learning (Malvaez et al., 2018) by HDAC3 inhibition. Similarly, mice lacking HDAC2 show enhanced extinction of fear conditioning, conditioned taste aversion, and an improvement in attentional set-shifting task (Morris et al., 2013). Inhibition of HDAC1, a member of the class I HDACs that is predominantly expressed in glia and neuronal progenitor cells (Broide et al., 2007; MacDonald and Roskams, 2008), did not alter BDNF expression in the current studies, nor did HDAC1 blockade alter memory consolidation in previous studies (Guan et al., 2009; Morris et al., 2013). Furthermore, multiple studies have shown that nonselective class I HDAC inhibitors increase BDNF expression and learning and memory and some of these effects are mediated by HDAC2 and HDAC3 (Lattal et al., 2007; Vecsey et al., 2007; Bredy and Barad, 2008; Guan et al., 2009; Stefanko et al., 2009; Malvaez et al., 2013; Rumbaugh et al., 2015; Sleiman et al., 2016). For example, β-hydroxybutyrate, a ketone body and HDACi produced by the liver following prolonged exercise, increased BDNF expression in the mouse hippocampus by preventing HDAC2 and HDAC3 binding to the promoter of BDNF I (Sleiman et al., 2016). In physiological studies, class I- or HDAC3-specific inhibition increased LTP, mEPSC frequency, and synapse formations (Rumbaugh et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2015; Krishna et al., 2016), mechanisms that are mediated, at least in part, by BDNF (Tyler and Pozzo-Miller, 2001; Bekinschtein et al., 2008).

Epigenetic reader of acetyl-lysine histones, particularly BET bromodomain proteins, have recently emerged as important factors involved in preclinical models of substance use disorder (Sartor et al., 2015; Egervari et al., 2017), seizures (Korb et al., 2015), autism (Sullivan et al., 2015), Alzheimer's disease (Magistri et al., 2016b; Benito et al., 2017), and fragile X syndrome (Korb et al., 2017). In the current and/or previous studies, BET inhibitors or BRD4-siRNA have been shown to decrease BDNF mRNA and protein in vitro and in vivo (Sartor et al., 2015; Zeier et al., 2015). Interestingly, a potential positive feedback system may exist between BRD4 and BDNF because a recent report showed that BDNF protein via TrkB signaling increases the expression and activation of BRD4 (Korb et al., 2015). Therefore, BRD4 appears to be a positive regulator of BDNF and a downstream epigenetic target of BDNF-TrkB signaling.

Revealing additional mechanisms involved in BRD4-mediated regulation of BDNF following HDAC3 inhibition, we showed that RGFP966 increases H4K5ac and H4K8ac levels in cells and BRD4 and H4K5ac enrichment at the BDNF I promoter. In previous studies, tri-acetylated H4 (H4K5/8/12) strongly promoted BRD4 binding in vitro (Dey et al., 2003; Filippakopoulos et al., 2012) and, at the genomic level, H4K5ac and H4K8ac were associated with 50% of the binding sites of BRD4 in CD4+ T cells (Zhang et al., 2012). Both H4K5ac and H4K8ac are increased in the hippocampus during memory consolidation (McQuown et al., 2011; Gräff et al., 2012; Malvaez et al., 2013), increased by RGFP966, and deacetylated by HDAC3 (Bhaskara et al., 2010; Rogge et al., 2013). Other in vivo studies have found that new learning decreases HDAC3 and increases H4K8ac at the BDNF I promoter (Intlekofer et al., 2013; Malvaez et al., 2018) and upregulation of hippocampal BDNF is essential for HDACi-induced enhancement of learning and memory (Intlekofer et al., 2013). Although JQ1 reduced and RGFP966 increased BDNF IV transcript expression, our ChIP results did not detect a significant enrichment of BRD4 or H4K5ac at the BDNF IV promoter following RGFP966 treatment. Therefore, it is possible that BRD4 regulates BDNF IV at a genomic location not examined in these experiments or that other BET proteins not examined (e.g., BRD2 or BRD3) regulate BDNF IV following RGFP966 treatment. Also, H4K8ac was not examined in the current ChIP experiments, but previous experiments have found that RGFP966 increases H4K8ac at the promoters of other genes involved in learning and memory (Malvaez et al., 2013; Rogge et al., 2013). Therefore, although HDAC3 and BRD4 appear to regulate the expression of multiple BDNF transcripts, overlapping mechanisms may exist at H4 acetylation sites on the BDNF I promoter.

Although we identified roles for BRD4 and HDAC3 in BDNF expression, the epigenetic regulation of BDNF is not limited to these proteins. For instance, inhibition of HDAC4 and HDAC5 causes an increase in BDNF expression (Koppel and Timmusk, 2013) and binding of HDAC5 to the BDNF exon IV promoter in the mouse hippocampus is associated with learned helplessness behavior and a reduction in BDNF expression (Su et al., 2016). However, there is some evidence indicating that HDAC4 and HDAC5 require interaction with HDAC3 for their HDAC activity (Fischle et al., 2002). The histone methyltransferase G9a regulates BDNF expression in the mouse brain following cocaine (Covington et al., 2011) or nicotine exposure (Chase and Sharma, 2013) and MeCP2, a DNA methytransferase, modulates BDNF expression following neuronal activity (Zhou et al., 2006). Based on these data, combinatorial epigenetic processes occurring at both histones and DNA are needed to regulate BDNF expression.

It is important to note that, although the current experiments focused on BDNF, many genes involved in LTP and learning and memory are known to be altered by RGFP966 and JQ1. For example, RGFP966 enhances the expression of Nr4a2 and Gria1, whereas JQ1 decreases Nr4a2 and Gria1 expression (Korb et al., 2015; Rumbaugh et al., 2015). Both Nr4a2 and Gria1 play a role in LTP (Bridi et al., 2017), cocaine CPP (Rogge et al., 2013; Chandra et al., 2015), and NOR (McNulty et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2016). Examples of other neuroplasticity-related genes that are changed by RGFP966 and/or JQ1 include Fos, Arc, Nr4a1, Egr2, Npas4, and Junb (Malvaez et al., 2013; Korb et al., 2015; Rumbaugh et al., 2015; Sartor et al., 2015; He et al., 2018). Therefore, multiple mechanisms likely contribute to RGFP966-induced enhancement of LTP and memory.

In the current studies, some experiments were conducted using HEK-293 and SH-SY5Y cells, which may not fully recapitulate the molecular mechanisms occurring in brain tissue. However, we and others have observed similar changes in BDNF and histone modifications following BRD4 and/or HDAC (HDAC class I and HDAC3-specific) manipulations across multiple in vitro and in vivo systems (Koppel and Timmusk, 2013; Rumbaugh et al., 2015; Sartor et al., 2015; Zeier et al., 2015). For example, in other reports, SAHA increased BDNF mRNA similarly in HEK-293 cells compared with primary neurons (Koppel and Timmusk, 2013); RGFP966 elevated BDNF mRNA by ∼70% in mouse hippocampus (see Rumbaugh et al., 2015, supplementary table) and BET inhibitors decreased BDNF expression in multiple cell lines, motor neurons, and mouse brain (Sartor et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2015; Zeier et al., 2015). Additionally, H4K5ac and H4K8ac, binding sites of BRD4, have previously been implicated in multiple forms of learning and memory and are deacetylated by HDAC3 (Bhaskara et al., 2010; Gräff et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013). These previous data, along with our current results, indicate that regulation of BDNF by HDAC3 and BRD4 is likely a conserved mechanism across multiple cell types.

In summary, we identified a novel interplay between epigenetic readers and erasers that is necessary for BDNF expression and neuroplasticity. Because anomalous expression of BDNF continues to be linked to several neurological and psychiatric disorders, understanding the multifaceted components involved in BDNF expression is imperative for future therapeutic advances. Expanding on the potential therapeutic opportunities, our results shed light on two distinct, druggable targets that are capable of increasing or decreasing BDNF expression depending on the treatment demand. Future studies examining the relationship among histone readers, writers, and erasers within the brain and at other genomic loci involved in neuroplasticity may enhance our understanding of how epigenetic mechanisms contribute to brain health and disease.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (Grants K99R00DA040744, R41DA042650, R01AA02378, R21DA035592, R37036800, R01037984, R01052258, and R01049711). The cocaine used in these studies was obtained from the National Institutes of Health's National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program. We thank Joseph Wasserman for his assistance in this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Aid T, Kazantseva A, Piirsoo M, Palm K, Timmusk T (2007) Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J Neurosci Res 85:525–535. 10.1002/jnr.21139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaghband Y, Kwapis JL, López AJ, White AO, Aimiuwu OV, Al-Kachak A, Bodinayake KK, Oparaugo NC, Dang R, Astarabadi M, Matheos DP, Wood MA (2017) Distinct roles for the deacetylase domain of HDAC3 in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex in the formation and extinction of memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem 145:94–104. 10.1016/j.nlm.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ali H, Lemmon VP, Bixby JL (2016) Phenotypic screening of small-molecule inhibitors: implications for therapeutic discovery and drug target development in traumatic brain injury. Methods Mol Biol 1462:677–688. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3816-2_37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Katche C, Slipczuk L, Rossato JI, Goldin A, Izquierdo I, Medina JH (2008) BDNF is essential to promote persistence of long-term memory storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:2711–2716. 10.1073/pnas.0711863105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito E, Ramachandran B, Schroeder H, Schmidt G, Urbanke H, Burkhardt S, Capece V, Dean C, Fischer A (2017) The BET/BRD inhibitor JQ1 improves brain plasticity in WT and APP mice. Transl Psychiatry 7:e1239. 10.1038/tp.2017.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskara S, Knutson SK, Jiang G, Chandrasekharan MB, Wilson AJ, Zheng S, Yenamandra A, Locke K, Yuan JL, Bonine-Summers AR, Wells CE, Kaiser JF, Washington MK, Zhao Z, Wagner FF, Sun ZW, Xia F, Holson EB, Khabele D, Hiebert SW (2010) Hdac3 is essential for the maintenance of chromatin structure and genome stability. Cancer Cell 18:436–447. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieszczad KM, Bechay K, Rusche JR, Jacques V, Kudugunti S, Miao W, Weinberger NM, McGaugh JL, Wood MA (2015) Histone deacetylase inhibition via RGFP966 releases the brakes on sensory cortical plasticity and the specificity of memory formation. J Neurosci 35:13124–13132. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0914-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodhinathan K, Kumar A, Foster TC (2010) Intracellular redox state alters NMDA receptor response during aging through Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurosci 30:1914–1924. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5485-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli E, Nestler EJ, Allis CD, Sassone-Corsi P (2008) Decoding the epigenetic language of neuronal plasticity. Neuron 60:961–974. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers ME, Xia B, Carreiro S, Ressler KJ (2015) The class I HDAC inhibitor RGFP963 enhances consolidation of cued fear extinction. Learn Mem 22:225–231. 10.1101/lm.036699.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredy TW, Barad M (2008) The histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid enhances acquisition, extinction, and reconsolidation of conditioned fear. Learn Mem 15:39–45. 10.1101/lm.801108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredy TW, Wu H, Crego C, Zellhoefer J, Sun YE, Barad M (2007) Histone modifications around individual BDNF gene promoters in prefrontal cortex are associated with extinction of conditioned fear. Learn Mem 14:268–276. 10.1101/lm.500907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridi MS, Hawk JD, Chatterjee S, Safe S, Abel T (2017) Pharmacological activators of the NR4A nuclear receptors enhance LTP in a CREB/CBP-dependent manner. Neuropsychopharmacology 42:1243–1253. 10.1038/npp.2016.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broide RS, Redwine JM, Aftahi N, Young W, Bloom FE, Winrow CJ (2007) Distribution of histone deacetylases 1–11 in the rat brain. J Mol Neurosci 31:47–58. 10.1007/BF02686117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra R, Francis TC, Konkalmatt P, Amgalan A, Gancarz AM, Dietz DM, Lobo MK (2015) Opposing role for Egr3 in nucleus accumbens cell subtypes in cocaine action. J Neurosci 35:7927–7937. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0548-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase KA, Sharma RP (2013) Nicotine induces chromatin remodelling through decreases in the methyltransferases GLP, G9a, Setdb1 and levels of H3K9me2. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16:1129–1138. 10.1017/S1461145712001101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE 3rd, Maze I, Sun H, Bomze HM, DeMaio KD, Wu EY, Dietz DM, Lobo MK, Ghose S, Mouzon E, Neve RL, Tamminga CA, Nestler EJ (2011) A role for repressive histone methylation in cocaine-induced vulnerability to stress. Neuron 71:656–670. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce N, Mathé AA, Gelfo F, Caltagirone C, Bernardini S, Angelucci F (2014) Effects of lithium and valproic acid on BDNF protein and gene expression in an in vitro human neuron-like model of degeneration. J Psychopharmacol 28:964–972. 10.1177/0269881114529379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey A, Chitsaz F, Abbasi A, Misteli T, Ozato K (2003) The double bromodomain protein Brd4 binds to acetylated chromatin during interphase and mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:8758–8763. 10.1073/pnas.1433065100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egervari G, Landry J, Callens J, Fullard JF, Roussos P, Keller E, Hurd YL (2017) Striatal H3K27 acetylation linked to glutamatergic gene dysregulation in human heroin abusers holds promise as therapeutic target. Biol Psychiatry 81:585–594. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenberg T, Mohammed AK, Henriksson B, Persson H, Winblad B, Lindefors N (1992) Increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in rat hippocampus is associated with improved spatial memory and enriched environment. Neurosci Lett 138:153–156. 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90494-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I, Philpott M, Munro S, McKeown MR, Wang Y, Christie AL, West N, Cameron MJ, Schwartz B, Heightman TD, La Thangue N, French CA, Wiest O, Kung AL, Knapp S, Bradner JE (2010) Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 468:1067–1073. 10.1038/nature09504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P, Picaud S, Mangos M, Keates T, Lambert JP, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Felletar I, Volkmer R, Müller S, Pawson T, Gingras AC, Arrowsmith CH, Knapp S (2012) Histone recognition and large-scale structural analysis of the human bromodomain family. Cell 149:214–231. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Dequiedt F, Hendzel MJ, Guenther MG, Lazar MA, Voelter W, Verdin E (2002) Enzymatic activity associated with class II HDACs is dependent on a multiprotein complex containing HDAC3 and SMRT/N-CoR. Mol Cell 9:45–57. 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00429-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AV, Rusche JR, McMahon LL (2014) Increased long-term potentiation at medial-perforant path-dentate granule cell synapses induced by selective inhibition of histone deacetylase 3 requires fragile X mental retardation protein. Neurobiol Learn Mem 114:193–197. 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi M, Nakashima F, Tabuchi A, Shimotori M, Tatsumi S, Okuno H, Bito H, Tsuda M (2015) Class I histone deacetylase-mediated repression of the proximal promoter of the activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein gene regulates its response to brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Biol Chem 290:6825–6836. 10.1074/jbc.M114.617258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganai SA, Ramadoss M, Mahadevan V (2016) Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors- emerging roles in neuronal memory, learning, synaptic plasticity and neural regeneration. Curr Neuropharmacol 14:55–71. 10.2174/1570159X13666151021111609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gräff J, Woldemichael BT, Berchtold D, Dewarrat G, Mansuy IM (2012) Dynamic histone marks in the hippocampus and cortex facilitate memory consolidation. Nat Commun 3:991. 10.1038/ncomms1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan JS, Haggarty SJ, Giacometti E, Dannenberg JH, Joseph N, Gao J, Nieland TJ, Zhou Y, Wang X, Mazitschek R, Bradner JE, DePinho RA, Jaenisch R, Tsai LH (2009) HDAC2 negatively regulates memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Nature 459:55–60. 10.1038/nature07925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harward SC, Hedrick NG, Hall CE, Parra-Bueno P, Milner TA, Pan E, Laviv T, Hempstead BL, Yasuda R, McNamara JO (2016) Autocrine BDNF-TrkB signalling within a single dendritic spine. Nature 538:99–103. 10.1038/nature19766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Zhang L, Queme LF, Liu X, Lu A, Waclaw RR, Dong X, Zhou W, Kidd G, Yoon SO, Buonanno A, Rubin JB, Xin M, Nave KA, Trapp BD, Jankowski MP, Lu QR (2018) A histone deacetylase 3-dependent pathway delimits peripheral myelin growth and functional regeneration. Nat Med 24:338–351. 10.1038/nm.4483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MM, Barde YA (1988) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevents neuronal death in vivo. Nature 331:261–262. 10.1038/331261a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Lu X, Liu R, Ai N, Cao Z, Li Y, Liu J, Yu B, Liu K, Wang H, Zhou C, Wang Y, Han A, Ding F, Chen R (2014) Histone cross-talk connects protein phosphatase 1alpha (PP1alpha) and histone deacetylase (HDAC) pathways to regulate the functional transition of bromodomain-containing 4 (BRD4) for inducible gene expression. J Biol Chem 289:23154–23167. 10.1074/jbc.M114.570812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intlekofer KA, Berchtold NC, Malvaez M, Carlos AJ, McQuown SC, Cunningham MJ, Wood MA, Cotman CW (2013) Exercise and sodium butyrate transform a subthreshold learning event into long-term memory via a brain-derived neurotrophic factor-dependent mechanism. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:2027–2034. 10.1038/npp.2013.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janczura KJ, Volmar CH, Sartor GC, Rao SJ, Ricciardi NR, Lambert G, Brothers SP, Wahlestedt C (2018) Inhibition of HDAC3 reverses Alzheimer's disease-related pathologies in vitro and in the 3xTg-AD mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E11148–E11157. 10.1073/pnas.1805436115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Kairisalo M, Korhonen L, Sepp M, Pruunsild P, Kukkonen JP, Kivinen J, Timmusk T, Blomgren K, Lindholm D (2009) NF-kappaB-dependent regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in hippocampal neurons by X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein. Eur J Neurosci 30:958–966. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpova NN. (2014) Role of BDNF epigenetics in activity-dependent neuronal plasticity. Neuropharmacology 76:709–718. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JI, Jeon SG, Kim KA, Kim YJ, Song EJ, Choi J, Ahn KJ, Kim CJ, Chung HY, Moon M, Chung H (2016) The pharmacological stimulation of Nurr1 improves cognitive functions via enhancement of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Stem Cell Res 17:534–543. 10.1016/j.scr.2016.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppel I, Timmusk T (2013) Differential regulation of bdnf expression in cortical neurons by class-selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. Neuropharmacology 75:106–115. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korb E, Herre M, Zucker-Scharff I, Darnell RB, Allis CD (2015) BET protein Brd4 activates transcription in neurons and BET inhibitor Jq1 blocks memory in mice. Nat Neurosci 18:1464–1473. 10.1038/nn.4095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korb E, Herre M, Zucker-Scharff I, Gresack J, Allis CD, Darnell RB (2017) Excess translation of epigenetic regulators contributes to fragile X syndrome and is alleviated by Brd4 inhibition. Cell 170:1209–1223.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte M, Carroll P, Wolf E, Brem G, Thoenen H, Bonhoeffer T (1995) Hippocampal long-term potentiation is impaired in mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:8856–8860. 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna K, Behnisch T, Sajikumar S (2016) Inhibition of histone deacetylase 3 restores amyloid-beta oligomer-induced plasticity deficit in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Alzheimers Dis 51:783–791. 10.3233/JAD-150838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A. (2010) Carbachol-induced long-term synaptic depression is enhanced during senescence at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses. J Neurophysiol 104:607–616. 10.1152/jn.00278.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Foster TC (2013) Linking redox regulation of NMDAR synaptic function to cognitive decline during aging. J Neurosci 33:15710–15715. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2176-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Foster TC (2014) Interaction of DHPG-LTD and synaptic-LTD at senescent CA3-CA1 hippocampal synapses. Hippocampus 24:466–475. 10.1002/hipo.22240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Choi KH, Renthal W, Tsankova NM, Theobald DE, Truong HT, Russo SJ, Laplant Q, Sasaki TS, Whistler KN, Neve RL, Self DW, Nestler EJ (2005) Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron 48:303–314. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Rani A, Scheinert RB, Ormerod BK, Foster TC (2018) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, indomethacin improves spatial memory and NMDA receptor function in aged animals. Neurobiol Aging 70:184–193. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapis JL, Alaghband Y, López AJ, White AO, Campbell RR, Dang RT, Rhee D, Tran AV, Carl AE, Matheos DP, Wood MA (2017) Context and auditory fear are differentially regulated by HDAC3 activity in the lateral and basal subnuclei of the amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology 42:1284–1294. 10.1038/npp.2016.274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal KM, Barrett RM, Wood MA (2007) Systemic or intrahippocampal delivery of histone deacetylase inhibitors facilitates fear extinction. Behav Neurosci 121:1125–1131. 10.1037/0735-7044.121.5.1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterborn JC, Rivera S, Stinis CT, Hayes VY, Isackson PJ, Gall CM (1996) Differential effects of protein synthesis inhibition on the activity-dependent expression of BDNF transcripts: evidence for immediate-early gene responses from specific promoters. J Neurosci 16:7428–7436. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07428.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QR, Lu L, Zhu XG, Gong JP, Shaham Y, Uhl GR (2006) Rodent BDNF genes, novel promoters, novel splice variants, and regulation by cocaine. Brain Res 1067:1–12. 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin FD, Roth TL, Sweatt JD (2008) Epigenetic regulation of BDNF gene transcription in the consolidation of fear memory. J Neurosci 28:10576–10586. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1786-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JL, Roskams AJ (2008) Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 are expressed at distinct stages of neuro-glial development. Dev Dyn 237:2256–2267. 10.1002/dvdy.21626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistri M, Velmeshev D, Makhmutova M, Faghihi MA (2015) Transcriptomics profiling of Alzheimer's disease reveal neurovascular defects, altered amyloid-beta homeostasis, and deregulated expression of long noncoding RNAs. J Alzheimers Dis 48:647–665. 10.3233/JAD-150398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistri M, Khoury N, Mazza EM, Velmeshev D, Lee JK, Bicciato S, Tsoulfas P, Faghihi MA (2016a) A comparative transcriptomic analysis of astrocytes differentiation from human neural progenitor cells. Eur J Neurosci 44:2858–2870. 10.1111/ejn.13382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistri M, Velmeshev D, Makhmutova M, Patel P, Sartor GC, Volmar CH, Wahlestedt C, Faghihi MA (2016b) The BET-bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 reduces inflammation and tau phosphorylation at Ser396 in the brain of the 3xTg model of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 13:985–995. 10.2174/1567205013666160427101832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahgoub M, Monteggia LM (2014) A role for histone deacetylases in the cellular and behavioral mechanisms underlying learning and memory. Learn Mem 21:564–568. 10.1101/lm.036012.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvaez M, McQuown SC, Rogge GA, Astarabadi M, Jacques V, Carreiro S, Rusche JR, Wood MA (2013) HDAC3-selective inhibitor enhances extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior in a persistent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:2647–2652. 10.1073/pnas.1213364110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvaez M, Greenfield VY, Matheos DP, Angelillis NA, Murphy MD, Kennedy PJ, Wood MA, Wassum KM (2018) Habits are negatively regulated by histone deacetylase 3 in the dorsal striatum. Biol Psychiatry 84:383–392. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty SE, Barrett RM, Vogel-Ciernia A, Malvaez M, Hernandez N, Davatolhagh MF, Matheos DP, Schiffman A, Wood MA (2012) Differential roles for Nr4a1 and Nr4a2 in object location vs. object recognition long-term memory. Learn Mem 19:588–592. 10.1101/lm.026385.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuown SC, Barrett RM, Matheos DP, Post RJ, Rogge GA, Alenghat T, Mullican SE, Jones S, Rusche JR, Lazar MA, Wood MA (2011) HDAC3 is a critical negative regulator of long-term memory formation. J Neurosci 31:764–774. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5052-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MJ, Mahgoub M, Na ES, Pranav H, Monteggia LM (2013) Loss of histone deacetylase 2 improves working memory and accelerates extinction learning. J Neurosci 33:6401–6411. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1001-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda S, Mack KJ (1998) Multiple promoters direct stimulus and temporal specific expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the somatosensory cortex. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 62:216–219. 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00242-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CS, Rehrauer H, Mansuy IM (2013) Genome-wide analysis of H4K5 acetylation associated with fear memory in mice. BMC Genomics 14:539. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson SL, Abel T, Deuel TA, Martin KC, Rose JC, Kandel ER (1996) Recombinant BDNF rescues deficits in basal synaptic transmission and hippocampal LTP in BDNF knockout mice. Neuron 16:1137–1145. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80140-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poo MM. (2001) Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Rev Neurosci 2:24–32. 10.1038/35049004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruunsild P, Kazantseva A, Aid T, Palm K, Timmusk T (2007) Dissecting the human BDNF locus: bidirectional transcription, complex splicing, and multiple promoters. Genomics 90:397–406. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, Sowa ME, Ottinger M, Smith JA, Shi Y, Harper JW, Howley PM (2011) The Brd4 extraterminal domain confers transcription activation independent of pTEFb by recruiting multiple proteins, including NSD3. Mol Cell Biol 31:2641–2652. 10.1128/MCB.01341-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogge GA, Singh H, Dang R, Wood MA (2013) HDAC3 is a negative regulator of cocaine-context-associated memory formation. J Neurosci 33:6623–6632. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4472-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaugh G, Sillivan SE, Ozkan ED, Rojas CS, Hubbs CR, Aceti M, Kilgore M, Kudugunti S, Puthanveettil SV, Sweatt JD, Rusche J, Miller CA (2015) Pharmacological selectivity within class I histone deacetylases predicts effects on synaptic function and memory rescue. Neuropsychopharmacology 40:2307–2316. 10.1038/npp.2015.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata K, Martinowich K, Woo NH, Schloesser RJ, Jimenez DV, Ji Y, Shen L, Lu B (2013) Role of activity-dependent BDNF expression in hippocampal-prefrontal cortical regulation of behavioral perseverance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:15103–15108. 10.1073/pnas.1222872110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor GC, Powell SK, Brothers SP, Wahlestedt C (2015) Epigenetic readers of lysine acetylation regulate cocaine-induced plasticity. J Neurosci 35:15062–15072. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0826-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HD, Sangrey GR, Darnell SB, Schassburger RL, Cha JH, Pierce RC, Sadri-Vakili G (2012) Increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression in the ventral tegmental area during cocaine abstinence is associated with increased histone acetylation at BDNF exon I-containing promoters. J Neurochem 120:202–209. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07571.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Shetty MS, Arumugam TV, Sajikumar S (2015) Histone deacetylase 3 inhibition re-establishes synaptic tagging and capture in aging through the activation of nuclear factor kappa B. Sci Rep 5:16616. 10.1038/srep16616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleiman SF, Henry J, Al-Haddad R, El Hayek L, Abou Haidar E, Stringer T, Ulja D, Karuppagounder SS, Holson EB, Ratan RR, Ninan I, Chao MV (2016) Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body beta-hydroxybutyrate. Elife 5:e15092. 10.7554/eLife.15092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanko DP, Barrett RM, Ly AR, Reolon GK, Wood MA (2009) Modulation of long-term memory for object recognition via HDAC inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:9447–9452. 10.1073/pnas.0903964106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su CL, Su CW, Hsiao YH, Gean PW (2016) Epigenetic regulation of BDNF in the learned helplessness-induced animal model of depression. J Psychiatr Res 76:101–110. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suelves N, Kirkham-McCarthy L, Lahue RS, Ginés S (2017) A selective inhibitor of histone deacetylase 3 prevents cognitive deficits and suppresses striatal CAG repeat expansions in Huntington's disease mice. Sci Rep 7:6082. 10.1038/s41598-017-05125-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JM, Badimon A, Schaefer U, Ayata P, Gray J, Chung CW, von Schimmelmann M, Zhang F, Garton N, Smithers N, Lewis H, Tarakhovsky A, Prinjha RK, Schaefer A (2015) Autism-like syndrome is induced by pharmacological suppression of BET proteins in young mice. J Exp Med 212:1771–1781. 10.1084/jem.20151271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler WJ, Pozzo-Miller LD (2001) BDNF enhances quantal neurotransmitter release and increases the number of docked vesicles at the active zones of hippocampal excitatory synapses. J Neurosci 21:4249–4258. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04249.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]