Abstract

Osteoporosis is a prevalent bone metabolic disease, mainly caused by excessive bone resorption (by osteoclasts) over bone formation (by osteoblasts). Identifying the key transcription factors and understanding the regulatory network influencing osteoclastogenesis will be helpful to explore the potential biological mechanism for osteoporosis. In our study, peripheral blood monocyte (PBM) was used as a cell model for bone mineral density (BMD) research. PBMs serve as progenitors of osteoclasts and produce important cytokines for osteoclastogenesis. In our study, via exon arrays, gene expression profiles of PBMs were analyzed between high versus low hip BMD groups. Transcription factors for differentially expressed genes were then predicted based on the enrichment analysis. We found that 591 genes were differentially expressed between the two BMD groups (nominally significant, raw p value < 0.05). For high BMD subjects, 482 genes were up-regulated and 109 genes were down-regulated. We then found 29 potential transcription factors for up-regulated genes and nine transcription factors for down-regulated genes. Among these transcription factors, HMGA1 and NFKB2 were differentially expressed between high versus low BMD groups. In addition, their regulation types with their target genes were consistent with the information from public databases. Our findings of key transcription factors and their target genes for osteoporosis were further validated by GWAS analysis. Overall, we predicted important transcription factors for osteoporosis. We were also able to infer the regulatory mechanism that exists between transcription factors and target genes in bone metabolism.

Keywords: Bone mineral density, Gene expression, Transcription factors

Introduction

Osteoporosis is the most prevalent metabolic bone disease, characterized by a decrease in bone mineral density (BMD). A key pathophysiological mechanism of this disease is the excessive bone resorption (by osteoclasts) over bone formation (by osteoblasts).

To investigate the transcriptome features relevant to the risk of osteoporosis, peripheral blood monocyte (PBM) is selected as a cell model in our study [1] with the following reasons. First, as a progenitor of osteoclast, PBMs are able to differentiate into osteoclasts [2–5]. Notably, PBMs are the sole source of osteoclast precursors for adult peripheral skeleton [6]. Second, PBMs can secrete various cytokines that are important for osteoclast differentiation, activation, and apoptosis [7–10]. Third, PBMs constitute 3 ~ 8% of human leukocytes in the blood and can be easily harvested with a high degree of purity that is important for transcriptome studies.

Transcription factors (TFs) are proteins involved in the process of transcription from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. Accumulating evidence suggests that TFs play significant roles in mediating osteoclast differentiation, survival, and resorption activity [11]. For example, transcription factor PU.1 is essential for the differentiation of osteoclast precursors [12]. PU.1 expression level increased with the osteoclastogenesis induced by either 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 or dexamethasone. The development of osteoclasts was arrested in PU.1-deficient mice [12]. c-Jun is a TF activated by RANKL. If the c-Jun is blocked, the RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation will be significantly inhibited in vitro [13]. A study also showed that nuclear factor kappa B (NFKB) knocked-out mice developed osteopetrosis because of a defect in osteoclast differentiation [14]. Further investigation on the regulation network of TFs and their target genes in PBMs may provide novel therapeutic strategies for osteoporosis caused by abnormal osteoclast differentiation and function.

In our current study, we used exon-array data from 73 Caucasian females. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were detected between high versus low BMD groups. We also screened the potential TFs regulating DEGs. Then, gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis was performed for target DEGs to predict the function of TFs in osteoporosis. In addition, we highlighted the TF and its target gene if they were both differentially expressed between high versus low BMD groups. These pairs of TF and target gene were further validated using the largest osteoporosis GWAS meta-analysis dataset from the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis Consortium (GEFOS).

Materials and Methods

Subjects’ Characteristics and Sample Preparation

Seventy-three unrelated Caucasian females with extremely high versus low hip BMD were recruited in this study [15]. (High BMD group: ZBMD > + 0.84, n = 42 vs. Low BMD group: ZBMD< − 0.52, n = 31). Via strict exclusion criteria, individuals with diseases that might affect bone metabolism were excluded. The hip BMD (g/cm2) of each subject was measured using a Hologic dual-energy X-ray absorptiometer (DXA) scanner (Hologic Corp., Waltham, MA). The Z score was defined as the number of standard deviations a subject’s BMD differed from the mean BMD of their age-, gender-, and ethnicity-matched population. It represented the location of a subject in the BMD value distribution in our study population. Here, high versus low BMD is defined as belonging to top versus bottom 30% of BMD values in our population. The detailed characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 1 and Ref. [15].

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of subjects for monocyte microarray analyses

| Menopausal status | High BMD |

Low BMD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age | Hip BMD Z score | N | Age | Hip BMD Z score | |

| Premenopausal | 16 | 51.0 (1.8) | 1.54 (0.52) | 15 | 50.0 (2.0) | − 0.93 (0.36) |

| Postmenopausal | 26 | 54.0 (1.8) | 1.28 (0.46) | 16 | 52.6 (2.5) | − 1.17 (0.60) |

| Total | 42 | 52.9 (2.3) | 1.38 (0.49) | 31 | 51.4 (2.6) | − 1.05 (0.51) |

Age and hip BMD Z score are shown as mean (standard deviation)

Sixty milliliter of peripheral blood was obtained from each subject and PBMs were immediately isolated using monocyte-negative isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec Inc, Auburn, CA) following the manufacturer’s recommendation. Then, total RNA from PBMs was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) and mRNA expression levels were determined by the GeneChip Human Exon 1.0 ST Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The raw microarray data for this cohort have been submitted to Gene Expression Omni-bus (GEO) under the accession number GSE56814.

Differentially Expressed Genes Detection

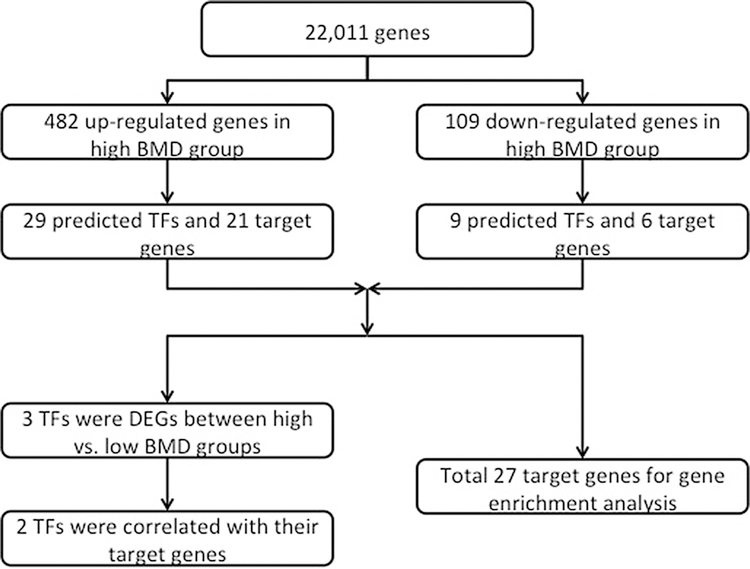

The pipeline of this study is shown in Fig. 1. For the microarray data analysis, the Affy package in R was used to import and process all raw CEL files. Then, the robust multiarray average method [16] was applied to normalize the array signals [17] and differential expression analysis was performed using Student’s t-test through the Bioconductor’s linear models for microarray data (LIMMA) package [18, 19]. If multiple probe IDs were mapped to the same gene symbol, the probe ID with the lowest p value among these probe IDs was selected to represent the gene. Because the sample size was limited (although still among the largest of such studies in the field), the adjusted p values were deemed to be too large after multiple testing control. We used raw p value < 0.05 as threshold for nominally significant differential expression.

Fig. 1.

The pipeline of transcription factor analysis

Potential Transcription Factors Detection

TFactS [20] (http://www.tfacts.org/) was used to predict TFs for DEGs generated from microarray data. TFactS contains a comprehensive TF database. It integrates the TF regulatory data from curated TRED [21], TRRD [22], PAZAR [23], and NFIregulomeDB [24] databases, and the regulation type (‘up’ or ‘down’) was based on the original publications. The up- and down-regulated DEGs were uploaded and screened separately. For each TF, if at least one of its annotated target genes is included in the DEG lists, we compare its annotated target genes with the DEG lists and use Fisher’s test to estimate the enrichment of the DEGs for this TF. The threshold for the significance of predicted TF was false discovery rate control (FDRc) < 0.05 [25].

Gene Enrichment Analysis for TFs Target Genes

To analyze the potential pathways that TFs regulated in osteoporosis, we loaded all DEGs regulated by the predicted TFs into the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID). The function of TFs was then predicted by analyzing their target genes on gene ontology (GO) terms and enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. The threshold for significant enrichment was FDR < 0.05.

Correlation Between TFs and Their Target Genes

If the TF and its target genes were both included in the DEGs list, we considered this TF to be more important for osteoporosis because expression level change of this TF may affect BMD variation directly. Pearson correlation was performed between differentially expressed TF and its target genes. The threshold for significant association was nominal p values < 0.05.

GWAS Data Validation

To investigate if the key candidate TFs and their target genes were associated with BMD in larger human populations, we also leveraged the results from the meta-analysis for the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis (GEFOS) Consortium (GEFOS-seq, meta-analysis results were downloaded from http://www.gefos.org/). It is the largest meta-analysis based on next-generation sequencing technologies and associated imputation to date for BMD study, including nine sub-cohorts and 32,965 Caucasians in the discovery cohort, both males and females [26]. We first selected the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) which were located in the candidate TFs or their target genes regions. The SNPs in the region from 5-kb upstream to 5-kb downstream of each gene were assigned to the gene. Then, we obtained the meta-analysis p values of those SNPs for forearm BMD (FA BMD), lumbar spine BMD (LS BMD), and femoral neck BMD (FN BMD) traits in women. The most significant SNP for a given gene was chosen as a gene-level p value. The threshold for significant association between genes and BMD traits was nominal p values < 0.05.

Results

DEGs Detection

In total, 22,011 genes (core set genes) were detected through microarray data processing. 591 genes were considered as differentially expressed genes (nominally significant, raw p value < 0.05) between high versus low BMD groups. In high BMD group, 482 genes were up-regulated and 109 genes were down-regulated.

Potential TFs Detection

Twenty-nine TFs were predicted to regulate the genes in up-regulated DEGs with FDRc < 0.05. Table 2 summarizes the regulatory network including 49 interactions between 29 predicted TFs and 21 target genes in up-regulated DEGs. Several genes were regulated by multiple TFs. For down-regulated DEGs, the regulatory network consisted of 11 interactions between nine predicted TFs and six target genes (Table 3).

Table 2.

Regulation type between predicted transcription factors and target genes in up-regulated DEGs

| Gene name | Transcription factor | Regulation type | FDRc |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCAP | AR | Up | 1.21E−02 |

| PGC | AR | Up | 1.21E−02 |

| NFKBIA | CTNNB1 | Down | 2.58E−02 |

| NR4A1 | CTNNB1 | Up | 2.58E−02 |

| IL8 | CTNNB1 | Up | 2.58E−02 |

| BIK | CTNNB1 | Up | 2.58E−02 |

| DKK1 | CTNNB1 | Up | 2.58E−02 |

| CCNB2 | FOXO1 | Down | 4.09E−02 |

| CNR1 | FOXO1 | Down | 4.09E−02 |

| IL8 | FOXO1 | Down | 4.09E−02 |

| DKK1 | FOXO1 | Up | 4.09E−02 |

| IL8 | FOXO3 | Down | 3.64E−02 |

| DKK1 | FOXO3 | Up | 3.64E−02 |

| RASSF8 | GLI1 | Up | 2.88E−02 |

| JUNB | GLI2 | Down | 3.94E−02 |

| JUNB | HBP1 | Up | 1.67E−02 |

| NR4A1 | HIF1A | Up | 2.12E−02 |

| CCNB2 | HMGA1 | Up | 3.03E−03 |

| CCNB2 | HMGA2 | Up | 1.52E−03 |

| IL8 | IRF9 | Down | 4.39E−02 |

| SMAD7 | JUN | Up | 1.97E−02 |

| IL8 | JUN | Up | 1.97E−02 |

| RPS18 | MYC | Up | 2.42E−02 |

| PPIF | MYC | Up | 2.42E−02 |

| HMGN2 | MYC | Up | 2.42E−02 |

| IL8 | NFKB2 | Up | 4.55E−03 |

| RELB | NOTCH1 | Up | 9.09E−03 |

| NFKB2 | NOTCH1 | Up | 9.09E−03 |

| RELB | RBPJ | Up | 1.06E−02 |

| NFKB2 | RBPJ | Up | 1.06E−02 |

| NFKBIA | RBPJ | Up | 1.06E−02 |

| IL8 | RELA | Up | 7.58E−03 |

| MMP3 | RELA | Up | 7.58E−03 |

| SMAD7 | SMAD2 | Up | 1.82E−02 |

| SMAD7 | SMAD3 | Up | 3.49E−02 |

| SMAD7 | SMAD4 | Up | 2.73E−02 |

| PIM1 | SP1 | Up | 1.36E−02 |

| CETP | SP1 | Up | 1.36E−02 |

| SMAD7 | SP1 | Up | 1.36E−02 |

| NFKBIA | SP1 | Up | 1.36E−02 |

| CETP | SREBF1 | Up | 3.18E−02 |

| CETP | SREBF2 | Up | 6.06E−03 |

| IL8 | STAT1 | Down | 5.00E−02 |

| IL8 | STAT2 | Down | 4.24E−02 |

| RNF149 | STAT3 | Up | 3.33E−02 |

| DKK1 | TCF7L2 | Up | 1.52E−02 |

| IL8 | TCF7L2 | Up | 1.52E−02 |

| DKK1 | TP53 | Up | 3.79E−02 |

| CETP | YY1 | Up | 3.03E−02 |

Table 3.

Regulation type between predicted transcription factors and target genes in down-regulated DEGs

| Gene name | Transcription factor | Regulation type | FDRc |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOP1 | E2F1 | Up | 1.36E−02 |

| HBP1 | FOXO3 | Up | 6.06E−03 |

| GATM | GLI1 | Down | 3.94E−02 |

| ABCA1 | GLI2 | Down | 1.21E−02 |

| PPAT | MYC | Up | 1.52E−02 |

| ABCA1 | NR1H2 | Up | 3.03E−03 |

| ABCG1 | NR1H2 | Up | 3.03E−03 |

| ABCG1 | NR1H3 | Up | 1.52E−03 |

| ABCA1 | NR1H3 | Up | 1.52E−03 |

| ABCA1 | SP3 | Down | 3.79E−02 |

| ABCA1 | SREBF2 | Down | 3.64E−02 |

Gene Enrichment Analysis

Table 4 shows the results of GO term analysis for 27 target genes. Prediction terms with a FDR < 0.05 were selected and ranked by FDR. The most significant terms were GO:0010745 ~ negative regulation of macrophage derived foam cell differentiation (biological process aspect) and GO:0015485 ~ cholesterol binding (molecular function aspect). As expected, genes were also significantly enriched in terms related to regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter (biological process aspect). To analyze the pathway affected by predicted TFs, we performed a kegg pathway analysis for target genes (Table 4). hsa04380: Osteoclast differentiation, hsa04064:NF-kappa B signaling pathway, and hsa04668:TNF signaling pathway were found to be the three most enriched pathways.

Table 4.

Gene enrichment analysis for target genes of predicted transcription factors

| Category | Term | Count | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0010745 ~ negative regulation of macrophage-derived foam cell differentiation | 4 | 9.81E−07 |

| GOTERM_MF | GO:0015485 ~ cholesterol binding | 4 | 2.87E−05 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0055091 ~ phospholipid homeostasis | 3 | 9.45E−05 |

| GOTERM_MF | GO:0005548 ~ phospholipid transporter activity | 3 | 9.57E−05 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0008203 ~ cholesterol metabolic process | 4 | 1.63E−04 |

| GOTERM_MF | GO:0017127 ~ cholesterol transporter activity | 3 | 2.22E−04 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0043691 ~ reverse cholesterol transport | 3 | 3.98E−04 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0042157 ~ lipoprotein metabolic process | 3 | 1.78E−03 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0034097 ~ response to cytokine | 3 | 3.30E−03 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0042632 ~ cholesterol homeostasis | 3 | 4.93E−03 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0045944 ~ positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 6 | 1.42E−02 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0045944 ~ positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 6 | 1.42E−02 |

| GOTERM_BP | GO:0000122 ~ negative regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 5 | 2.17E−02 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04380: Osteoclast differentiation | 4 | 3.11E−03 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04064: NF-kappa B signaling pathway | 3 | 1.57E−02 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04668: TNF signaling pathway | 3 | 2.22E−02 |

Important Candidate TFs Selection

To further explore the TFs directly associated with BMD variation, we screened the predicted TFs in DEGs list and detected three differentially expressed TFs: HMG-box transcription factor 1 (HBP1), high mobility group AT-hook 1 (HMGA1), and nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 2 (NFKB2). Then, Pearson correlation was conducted to examine the relationship between these three TFs and their target genes. JUNB (jun B proto-oncogene) was not associated with HBP1 (r = − 0.201, p = 0.088) and the relationship was different from the known regulation type in the datasets (“up”). For the other two TFs, cyclin B2 (CCNB2) and HMGA1 were associated with each other (r = 0.441, p < 0.001). Interleukin 8 (IL8) was associated with NFKB2 (r = 0.401, p < 0.001). Moreover, they were positively associated with their target genes, consistent with the known regulation type in the datasets (“up”).

Validation by GWAS Studies

Table 5 showed the results for GEFOS-seq meta-analysis approach and gene-level p values for FA BMD, FN BMD, and LS BMD, represented by the most significant SNP/ marker in the gene. We used nominal p value < 0.05 as criteria for significance. HMGA1 was associated with FA BMD, FN BMD, and LS BMD, whereas its target gene CCNB2 was not. NFKB2 and IL8 were associated with FA BMD. We also tested our most significant predicted TF, HMGA2. HMGA2 was associated with FA BMD, FN BMD, and LS BMD.

Table 5.

Validation in GEFOS-seq dataset

| Gene | SNP ID | Effect allele | Other allele | Effect allele frequency |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association with forearm BMD | |||||

| HMGA1 | rs75195065 | G | A | 0.006 | 1.37E−02 |

| CCNB2 | rs142078254 | C | A | 0.005 | 5.25E−02 |

| NFKB2 | rs36226954 | C | T | 0.023 | 3.39E−02 |

| IL8 | rs2227543 | T | C | 0.369 | 1.60E−02 |

| Association with lumbar spine BMD | |||||

| HMGA1 | rs4713761 | A | T | 0.044 | 3.53E−02 |

| CCNB2 | rs188208891 | A | T | 0.000 | 1.27E−01 |

| NFKB2 | rs1572532 | T | C | 0.995 | 1.37E−01 |

| IL8 | rs142715747 | T | C | 0.005 | 4.66E−01 |

| Association with femoral neck BMD | |||||

| HMGA1 | rs4713761 | A | T | 0.044 | 9.66E−03 |

| CCNB2 | rs28383510 | C | G | 0.014 | 1.03E−01 |

| NFKB2 | rs3740418 | G | C | 0.321 | 4.82E−01 |

| IL8 | rs1126647 | T | A | 0.364 | 7.86E−02 |

Discussion

In this study, we screened the DEGs in PBMs between high versus low hip BMD via Human Affymetrix Exon 1.0 ST Array. Since the transcription process of genes was regulated by TFs, we used DEGs as candidate target genes to detect potential TFs that might affect skeletal metabolism. Gene enrichment and pathway analysis were conducted to further investigate the roles of TFs in osteoclastogenesis and bone density regulation process. Finally, we selected the TFs included in DEGs as the candidate TFs directly affecting BMD variation. We found that two TFs, HMGA1 and NFKB2, were significantly associated with their target genes and regulation types were consistent with evidenced information from the dataset. To validate the importance of key predicted TFs and their target genes for BMD, we screened the SNPs located in these TFs or genes in the largest GWAS database (GEFOS-seq) for bone study.

Transcription factors have been reported to be associated with bone development and related diseases [27]. In our study, we took the advantage of the TFactS [20] tool to predict the candidate TFs. As a comprehensive database, it contains TFs and their target genes information from four TF datasets and public articles. Using Fisher’s exact test, we calculated the enrichment of target genes in DEGs for each TFs and found the key TFs for osteoporosis. A total of 33 unique TFs were found to be potentially involved in the regulatory network for BMD variation. Many of these TFs were also found in previous bone-related studies. For example, High Mobility Group AT-Hook 2 (HMGA2), the most significant TFs predicted in our study, was also suggested to be associated with BMD in a genotyping study [28]. And in our validation study, we also found that this TF was associated FA BMD, FN BMD, and LS BMD in the largest GWAS database for bone study (data not shown here). Via conditional gene deletion cells, Smad family was indicated to be important for osteoclast differentiation [29]. In the animal model, SMAD4 conditional knockout mice showed significantly reduced bone mass and elevated osteoclast formation relative to controls [29]. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family, predicted in our study, was another well-known TF group modulating osteoclast differentiation [30, 31].

To find the biological mechanism for candidate TFs affecting BMD variation, we performed the pathway analysis for target genes. The most significant GO term was “negative regulation of macrophage derived foam cell differentiation” (Table 4). Macrophage is another cell type differentiated from PBMs besides osteoclasts [32]. This suggested that our predicted TFs might modulate the differentiation process of PBMs. A similar result was also found by performing a KEGG pathway analysis. The target genes were most enriched in “Osteoclast differentiation” pathway (Table 4). It is demonstrated that candidate TFs might affect osteoclastogenesis in vivo.

TFs regulate gene expression via a complex set of mechanisms, including structure change and amount change. Therefore, we focused on the pair of TF and target gene both contained in the DEGs list. We found three pairs in DEGs list and two of them have the same regulation type as the known TF databases of TFactS including TRED, TRRD, PAZAR, and NFIregulomeDB. In the three pairs, JUNB and HBP1 were not associated with each other in our results. For the other two TFs, Yao et al. demonstrated that the NFKB2 (p100) played as a negative regulator of osteoclastogenesis [33]. The mice with deletion of both NFKB1 and NFKB2 had severe osteopetrosis [14]. The other TF, HMGA1, was reported as a novel osteoclast-related gene in a proteomic analysis study using quantitative mass spectrometry strategy [34]. A large number of HMGA1 target genes were found to be associated with osteoclastogenesis [35]. However, the currently existing bone-related studies are still lacking regarding both of these TFs. So, we screened these two TFs and their target genes in GEFOS-seq database for SNP analysis. HMGA1, NFKB2, IL8 were associated with at least one BMD trait (Table 5).

There were several limitations of this study. First, PBMs are not equal to osteoclasts. Our findings could show the potential mechanism of osteoporosis, but direct validation is needed. Second, the cell and RNA samples were not left in this study. So, we could not conduct functional experiment to fully illustrate our findings in the regulation of BMD.

In summary, through a gene expression array analysis, we predicted 34 unique TFs which might be important for osteoporosis. Through GO term and pathway analyses, the main process that these TFs were involved in was suggested to be the differentiation from PBMs to osteoclasts. Two predicted TFs, HMGA1 and NFKB2, were differentially expressed (nominally) between high versus low BMD subjects and showed the same regulation type with their target genes as the known information from public databases. These findings may provide novel insights into the regulatory network of bone-related metabolism.

Acknowledgements

The investigators of this work were partially supported by grants from the NIH (AR069055, U19 AG055373, R01 MH104680, R01AR059781, and P20GM109036), and the Edward G. Schlieder Endowment as well as the Drs. W. C. Tsai and P. T. Kung Professorship in Biostatistics from Tulane University.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest Yu Zhou, Wei Zhu, Lan Zhang, Yong Zeng, Chao Xu, Qing Tian, and Hong-Wen Deng declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent All the research methods employed in this study were conducted in accordance with the rules and guidelines of the Institutional Review Boards of University of Missouri Kansas City and Tulane University. The Institutional Review Boards of University of Missouri Kansas City and Tulane University approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion in this study.

References

- 1.Zhou Y, Deng HW, Shen H (2015) Circulating monocytes: an appropriate model for bone-related study. Osteoporos Int 26(11):2561–2572. 10.1007/s00198-015-3250-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujikawa Y, Quinn JM, Sabokbar A, McGee JO, Athanasou NA (1996) The human osteoclast precursor circulates in the monocyte fraction. Endocrinology 137(9):4058–4060. 10.1210/endo.137.9.8756585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higuchi S, Tabata N, Tajima M, Ito M, Tsurudome M, Sudo A, Uchida A, Ito Y (1998) Induction of human osteoclast-like cells by treatment of blood monocytes with anti-fusion regulatory protein-1/CD98 monoclonal antibodies. J Bone Miner Res 13(1):44–49. 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matayoshi A, Brown C, DiPersio JF, Haug J, Abu-Amer Y, Liapis H, Kuestner R, Pacifici R (1996) Human blood-mobilized hematopoietic precursors differentiate into osteoclasts in the absence of stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93(20):10785–10790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purton LE, Lee MY, Torok-Storb B (1996) Normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells mobilized with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor have increased osteoclastogenic potential compared to nonmobilized blood. Blood 87(5):1802–1808 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Custer RPAF (1932) Studies of the structure and function of bone marrow:variations in cellularity in various bones with advancing years of life and their relative response to stimuli. J Lab Clin Med 17:960–962 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horton MA, Spragg JH, Bodary SC, Helfrich MH (1994) Recognition of cryptic sites in human and mouse laminins by rat osteoclasts is mediated by beta 3 and beta 1 integrins. Bone 15(6):639–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parfitt AM (1994) Osteonal and hemi-osteonal remodeling: the spatial and temporal framework for signal traffic in adult human bone. J Cell Biochem 55(3):273–286. 10.1002/jcb.240550303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parfitt AM (1998) Osteoclast precursors as leukocytes: importance of the area code. Bone 23(6):491–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zambonin Zallone A, Teti A, Primavera MV (1984) Monocytes from circulating blood fuse in vitro with purified osteoclasts in primary culture. J Cell Sci 66:335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jimi E, Akiyama S, Tsurukai T, Okahashi N, Kobayashi K, Udagawa N, Nishihara T, Takahashi N, Suda T (1999) Osteoclast differentiation factor acts as a multifunctional regulator in murine osteoclast differentiation and function. J Immunol 163(1):434–442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tondravi MM, McKercher SR, Anderson K, Erdmann JM, Quiroz M, Maki R, Teitelbaum SL (1997) Osteopetrosis in mice lacking haematopoietic transcription factor PU.1. Nature 386:81 10.1038/386081a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda F, Nishimura R, Matsubara T, Tanaka S, Inoue J, Reddy SV, Hata K, Yamashita K, Hiraga T, Watanabe T, Kukita T, Yoshioka K, Rao A, Yoneda T (2004) Critical roles of c-Jun signaling in regulation of NFAT family and RANKL-regulated osteoclast differentiation. J Clin Invest 114(4):475–484. 10.1172/JCI19657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iotsova V, Caamano J, Loy J, Yang Y, Lewin A, Bravo R (1997) Osteopetrosis in mice lacking NF-kappaB1 and NF-kappaB2. Nat Med 3(11):1285–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu YZ, Zhou Y, Zhang L, Li J, Tian Q, Zhang JG, Deng HW (2015) Attenuated monocyte apoptosis, a new mechanism for osteoporosis suggested by a transcriptome-wide expression study of monocytes. PLoS ONE 10(2):e0116792 10.1371/journal.pone.0116792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP (2003) Summaries of affymetrix genechip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res 31(4):e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA (2010) A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics 26(19):2363–2367. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendziorski C, Irizarry RA, Chen KS, Haag JD, Gould MN (2005) On the utility of pooling biological samples in microarray experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(12):4252–4257. 10.1073/pnas.0500607102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smyth GK (2005) Limma: linear models for microarray data. In: Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and bioconductor Springer, New York, pp 397–420 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Essaghir A, Toffalini F, Knoops L, Kallin A, van Helden J, Demoulin JB (2010) Transcription factor regulation can be accurately predicted from the presence of target gene signatures in microarray gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res 38(11):e120 10.1093/nar/gkq149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao F, Xuan Z, Liu L, Zhang MQ (2005) TRED: a transcriptional regulatory element database and a platform for in silico gene regulation studies. Nucleic Acids Res 33:D103–D107. 10.1093/nar/gki004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kel AE, Kolchanov NA, Kel OV, Romashchenko AG, Anan’ko EA, Ignat’eva EV, Merkulova TI, Podkolodnaia OA, Stepanenko IL, Kochetov AV, Kolpakov FA, Podkolodnyi NL, Naumochkin AA (1997) TRRD: a database of transcription regulatory regions in eukaryotic genes. Mol Biol (Mosk) 31(4):626–636 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Portales-Casamar E, Kirov S, Lim J, Lithwick S, Swanson MI, Ticoll A, Snoddy J, Wasserman WW (2007) PAZAR: a framework for collection and dissemination of cis-regulatory sequence annotation. Genome Biol 8(10):R207 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gronostajski RM, Guaneri J, Lee DH, Gallo SM (2011) The NFI-Regulome Database: a tool for annotation and analysis of control regions of genes regulated by Nuclear Factor I transcription factors. J Clin Bioinform 1(1):4 10.1186/2043-9113-1-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol) 57(1):289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng HF, Forgetta V, Hsu YH, Estrada K, Rosello-Diez A, Leo PJ, Dahia CL, Park-Min KH, Tobias JH, Kooperberg C, Kleinman A, Styrkarsdottir U, Liu CT, Uggla C, Evans DS, Nielson CM, Walter K, Pettersson-Kymmer U, McCarthy S, Eriksson J, Kwan T, Jhamai M, Trajanoska K, Memari Y, Min J, Huang J, Danecek P, Wilmot B, Li R, Chou WC, Mokry LE, Moayyeri A, Claussnitzer M, Cheng CH, Cheung W, Medina-Gomez C, Ge B, Chen SH, Choi K, Oei L, Fraser J, Kraaij R, Hibbs MA, Gregson CL, Paquette D, Hofman A, Wibom C, Tranah GJ, Marshall M, Gardiner BB, Cremin K, Auer P, Hsu L, Ring S, Tung JY, Thorleifsson G, Enneman AW, van Schoor NM, de Groot LC, van der Velde N, Melin B, Kemp JP, Christiansen C, Sayers A, Zhou Y, Calderari S, van Rooij J, Carlson C, Peters U, Berlivet S, Dostie J, Uitterlinden AG, Williams SR, Farber C, Grinberg D, LaCroix AZ, Haessler J, Chasman DI, Giulianini F, Rose LM, Ridker PM, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV, Center JR, Nogues X, Garcia-Giralt N, Launer LL, Gudnason V, Mellstrom D, Vandenput L, Amin N, van Duijn CM, Karlsson MK, Ljunggren O, Svensson O, Hallmans G, Rousseau F, Giroux S, Bussiere J, Arp PP, Koromani F, Prince RL, Lewis JR, Langdahl BL, Hermann AP, Jensen JE, Kaptoge S, Khaw KT, Reeve J, Formosa MM, Xuereb-Anastasi A, Akesson K, McGuigan FE, Garg G, Olmos JM, Zarrabeitia MT, Riancho JA, Ralston SH, Alonso N, Jiang X, Goltzman D, Pastinen T, Grundberg E, Gauguier D, Orwoll ES, Karasik D, Davey-Smith G, Consortium A, Smith AV, Siggeirsdottir K, Harris TB, Zillikens MC, van Meurs JB, Thorsteinsdottir U, Maurano MT, Timpson NJ, Soranzo N, Durbin R, Wilson SG, Ntzani EE, Brown MA, Stefansson K, Hinds DA, Spector T, Cupples LA, Ohlsson C, Greenwood CM, Consortium UK, Jackson RD, Rowe DW, Loomis CA, Evans DM, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Joyner AL, Duncan EL, Kiel DP, Rivadeneira F, Richards JB (2015) Whole-genome sequencing identifies EN1 as a determinant of bone density and fracture. Nature 526(7571):112–117. 10.1038/nature14878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X, Karsenty G (2002) Transcription factors in bone: developmental and pathological aspects. Trends Mol Med 8(7):340–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuipers A, Zhang Y, Cauley JA, Nestlerode CS, Chu Y, Bunker CH, Patrick AL, Wheeler VW, Hoffman AR, Orwoll ES, Zmuda JM (2009) Association of a high mobility group gene (HMGA2) variant with bone mineral density. Bone 45(2):295–300. 10.1016/j.bone.2009.04.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morita M, Yoshida S, Iwasaki R, Yasui T, Sato Y, Kobayashi T, Watanabe R, Oike T, Miyamoto K, Takami M, Ozato K, Deng CX, Aburatani H, Tanaka S, Yoshimura A, Toyama Y, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, Kawana H, Nakagawa T, Miyamoto T (2016) Smad4 is required to inhibit osteoclastogenesis and maintain bone mass. Sci Rep 6:35221 10.1038/srep35221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha H, Lee JH, Kim HN, Kwak HB, Kim HM, Lee SE, Rhee JH, Kim HH, Lee ZH (2008) Stimulation by TLR5 modulates osteoclast differentiation through STAT1/IFN-beta. J Immunol 180(3):1382–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Hu H, Jin J, Ohashi E, Greeley N, Li H, Sun S-c, Watowich S (2012) Crosstalk between STAT3 and RANK signaling pathways during osteoclastogenesis (174.7). J Immunol 188(1 Supplement):174. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross R (1999) Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340(2):115–126. 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao Z, Xing L, Boyce BF (2009) NF-kappaB p100 limits TNF-induced bone resorption in mice by a TRAF3-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest 119(10):3024–3034. 10.1172/JCI38716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Itou T, Maldonado N, Yamada I, Goettsch C, Matsumoto J, Aikawa M, Singh S, Aikawa E (2014) Cystathionine gamma-lyase accelerates osteoclast differentiation: identification of a novel regulator of osteoclastogenesis by proteomic analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34(3):626–634. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumter TF, Xian L, Huso T, Koo M, Chang YT, Almasri TN, Chia L, Inglis C, Reid D, Resar LM (2016) The high mobility group A1 (HMGA1) transcriptome in cancer and development. Curr Mol Med 16(4):353–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]