Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is often the result of mutations that block drug activity; however, bacteria also evade antibiotics by transiently expressing genes such as multidrug efflux pumps. A crucial question is whether transient resistance can promote permanent genetic changes. Previous studies have established that antibiotic treatment can select tolerant cells that then mutate to achieve permanent resistance. Whether these mutations result from antibiotic stress or preexist within the population is unclear. To address this question, we focused on the multidrug pump AcrAB-TolC. Using time-lapse microscopy, we found that cells with higher acrAB expression have lower expression of the DNA mismatch repair gene mutS, lower growth rates, and higher mutation frequencies. Thus, transient antibiotic resistance from elevated acrAB expression can promote spontaneous mutations within single cells.

Antibiotic resistance is a major public health problem and is primarily the result of genetic changes that allow microorganisms to overcome the effects of antimicrobial drugs (1). However, genetic changes are not the only way that bacteria can tolerate antibiotics. Transient resistance mechanisms allow cells to temporarily resist drug treatment (2), playing a critical role in recalcitrant and recurrent infections (3). Examples include bacterial persistence, where cells temporarily enter a dormant state to block drug activity (4), and expression of efflux pumps to export antibiotics (5–7). We asked whether transient antibiotic resistance can lead to permanent antibiotic resistance by providing a window of opportunity in which cells can mutate. A recent study showed that bacterial persistence precedes resistance. In this state, tolerant cells can subsequently acquire mutations conferring resistance (8). Additionally, antibiotics often induce stress response mechanisms, which can lead to mutations. For instance, the low-fidelity, mutation-prone polymerasesPol II, Pol IV, and Pol V are induced during the SOS response to DNA damage (9). A question remains whether differences in mutation frequency predate antibiotic treatment or whether they are induced by the stress.

We focused on transient resistance arising from heterogeneity in expression of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump found in many pathogens (6, 7, 10). The pump recognizes and exports β-lactam, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolone antibiotics, among others (11), by using the inner membrane protein AcrB, which works together with the periplasmic linker AcrA and the outer membrane channel TolC (10, 12). acrA and acrB are commonly arranged together on an operon, whereas tolC is expressed elsewhere in the genome.

Recent reports have highlighted the importance of cell-to-cell variability in pump expression (6, 7). For example, in Escherichia coli, AcrAB-TolC pumps partition heterogeneously, with pumps accumulating at the old pole, resulting in increased resistance levels in the subset of cells with higher efflux pump expression (7). We asked whether cell-to-cell heterogeneity in pump expression results in differences in the spontaneous mutation rate in addition to its known role in producing single-cell differences in transient antibiotic resistance.

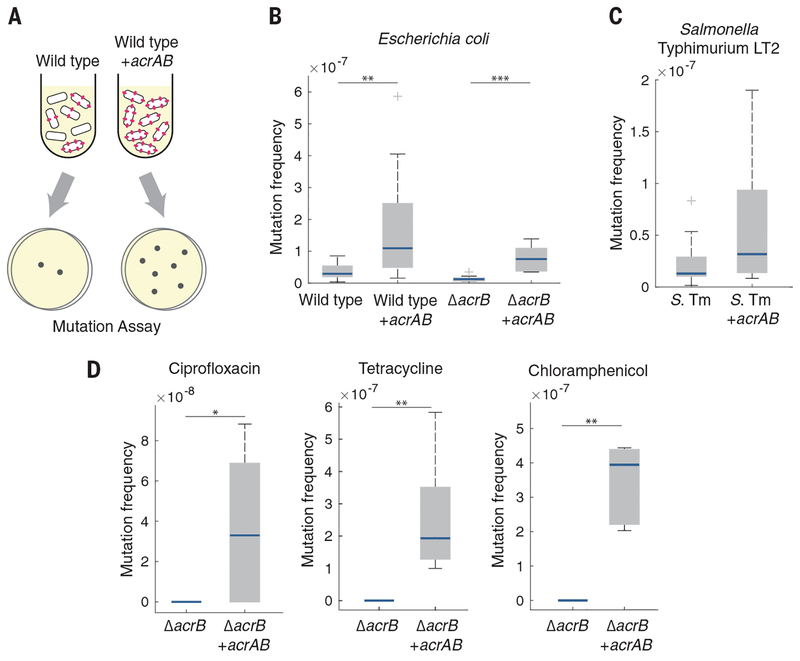

We first calculated the spontaneous mutation frequency in E. coli strains with and without efflux pumps. To identify mutations not induced by stress, we performed these measurements in the absence of antibiotics. We plated mid–exponential phase cultures on LB agar with and without rifampicin and calculated the mutation frequency by dividing the number of colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter on rifampicin plates by the number of CFU per milliliter on LB plates (Fig. 1A) (13).

Fig. 1. Overexpression of AcrAB increases the spontaneous mutation frequency.

(A) Schematic showing an increase in spontaneous mutations in cells with higher efflux pump expression. (B) Rifampicin mutation frequency in E. coli wild-type and ΔacrB strains with and without acrAB overexpression. n ≥ 8 biological replicates. (C) Rifampicin mutation frequency in S. Typhimurium (S. Tm) LT2. n ≥ 12 biological replicates. (D) Ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol mutation frequencies in E. coli ΔacrB. n ≥ 5 biological replicates. The ΔacrB strain in (D) did not produce any mutants in the presence of any of the antibiotics; mutants were observed for all antibiotics in the acrAB overexpression strain. For (B) to (D), blue bars show the median values, gray boxes indicate the interquartile range, and whiskers show the maximum and minimum values. Box plot raw data are shown in fig. S9A. Strains without acrAB overexpression contained an equivalent plasmid expressing cfp in place of acrAB. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01;***P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

We first compared wild-type E. coli strains with and without overexpression of the acrAB operon. Although AcrA and AcrB function together with TolC, overexpression of the acrAB operon alone is sufficient to increase resistance (14, 15). We found that the wild-type strain had a significantly lower mutation frequency than the strain overexpressing acrAB (Fig. 1B). These mutation frequencies correspond to mutation rates of 1.06 × 10−8 and 2.84 × 10−8 mutations per generation in the wild-type and acrAB strains, respectively (table S1), providing resistance without incurring a major fitness cost (16). Deleting acrB, which inactivates the entire efflux pump (14), also significantly decreased the mutation frequency relative to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 1B). Complementing the ΔacrB strain with a plasmid containing the acrAB operon restored and further increased the mutation frequency over that of the wild type. Using sequencing, we confirmed that the resistance originated from mutations within the rpoB gene, which is a known target for rifampicin (17) (table S2). Taken together, these results suggest that elevated expression of the AcrAB efflux pump, which plays a critical role in transient resistance, can also increase the frequency of spontaneous mutations.

We asked whether our findings could be generalized to other bacterial species by focusing on the pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (10). We introduced a plasmid overexpressing acrAB into S. Typhimurium and again observed an increase in the spontaneous mutation frequency (Fig. 1C).

We also measured mutation frequencies in E. coli ΔacrB with and without acrAB overexpression by using ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol. In each case, we used antibiotic concentrations that exceeded the minimum inhibitory concentration for the strain with acrAB overexpression to ensure that we were measuring the mutation frequency and not differences due to drug efflux (15, 18) (fig. S1). Consistent with our results in rifampicin, overexpression of acrAB significantly increased the mutation frequency in all three antibiotics relative to those of the strains lacking the pumps (Fig. 1D).

To test whether the differences in mutation frequency are due to pump activity, we generated a catalytically compromised mutant expressing acrB with a Phe610→Ala (F610A) mutation (19). In contrast to bacteria with functional AcrB, the ΔacrB strain complemented with a plasmid containing acrAB F610A had no change in the mutation frequency relative to the ΔacrB strain (fig. S2), suggesting that pump activity is critical for the mutation rate differences.

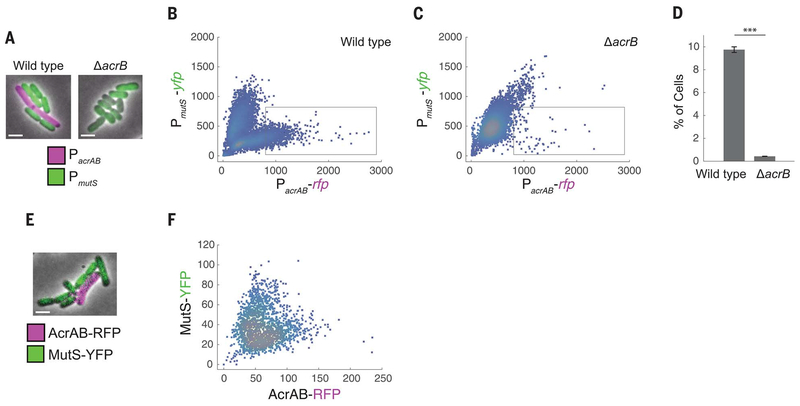

MutS is involved in DNA mismatch repair, which is a crucial step in preventing mutations. MutS deficiency leads to a hypermutable phenotype (20). Recent studies have revealed heterogeneity in the expression of DNA repair enzymes between single cells, highlighting the importance of single-cell–level effects in the emergence of resistance (21–23). To study the link between acrAB and mutS expression, we constructed a double-color plasmid to report expression simultaneously from the acrAB and mutS promoters. We fused the acrAB promoter to the gene for red fluorescent protein (RFP) (yielding PacrAB-rfp)

and the mutS promoter to the gene for yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) (yielding PmutS-yfp). Using fluorescence microscopy, we observed cell-to-cell variation in both reporters, with cells expressing either PacrAB-rfp or PmutS-yfp but not both (Fig. 2, A and B). This indicates that cells with higher efflux pump expression, which are more antibiotic resistant (7), also have less mismatch repair, making them more mutation prone (21).

Fig. 2. Inverse relationship between acrAB expression and mutS expression in single cells.

(A) Fluorescence microscopy images of E. coli wild-type and ΔacrB strains containing the double-color reporter PacrAB-rfp + PmutS-yfp. Scale bars, 2 μm. (B and C) RFP fluorescence reflecting acrAB promoter activity versus YFP fluorescence reflecting mutS promoter activity in (B) wild-type and (C) ΔacrB strains. Each dot corresponds to one cell. The gray box indicates the region of interest used for (D). (D) Percentages of the cell populations that fall within the region-of-interest box. Error bars, ± SEM. ***P < 0.001, two-sample t test. (E) Wild-type E. coli containing translational fusion PacrAB-acrAB-rfp + PmutS-mutS-yfp. (F) AcrAB-RFP versus MutS-YFP. All fluorescence data were obtained after background subtraction to remove autofluorescence. Values in (B), (C), and (F) are expressed in arbitrary units.

To check whether this effect is due to AcrAB, we introduced the double-color reporter into the ΔacrB strain. This decreased the population of cells with high PacrAB and low PmutS expression (Fig. 2, A, C, and D) and potentially indicates positive feedback between AcrAB and its promoter. Complementing the ΔacrB strain with a plasmid containing acrAB restored cells with higher levels of PacrAB and lower levels of PmutS expression (fig. S3). To rule out spurious plasmid effects as the cause of the inverse relationship, we also tested double-color reporters in which we replaced the PacrAB and PmutS promoters each with a constitutive promoter and no longer observed the reciprocal relationship between the two colors (fig. S4).

Transcriptional fusions between promoters and reporters give an indirect measurement of protein levels; therefore, we next sought to verify our findings by using translational fusions of AcrAB and MutS with fluorescent reporters. We observed a similar relationship between AcrAB-RFP and MutS-YFP, with a subset of cells containing higher levels of AcrAB efflux pumps and lower MutS expression (Fig. 2, E and F).

When we overexpressed acrAB in a ΔmutS strain, we observed no significant difference in the spontaneous mutation frequency between the strains with and without acrAB overexpression (fig. S5). Because MutS is involved in mutation repair, the overall mutation rate is higher in the ΔmutS strain than in wild-type cells (24). The similar mutation frequencies observed with and without acrAB overexpression may be due to the role of MutS as an effector in the AcrAB-dependent mutation increase, or alternatively, the strong mutator phenotype may simply mask any differences.

The AcrAB pump provides transient antibiotic resistance but can be costly to express. Overexpression alters membrane fluidity, slows growth, and can cause cells to pump out essential metabolites (10, 25). Thus, there is a trade-off between pump expression and fitness (25). It is well known that mutation rates are dependent on growth rates in E. coli, and mutS expression is repressed in nutritionally stressed cells (26–28). We found that the total number of CFU per milliliter decreased when acrAB was overexpressed (fig. S6). Using time-lapse microscopy, we grew wild-type cells containing the double-color transcriptional reporter (PacrAB-rfp and PmutS-yfp) on agarose pads. Single cells with high PacrAB and low PmutS expression grew more slowly than those with low PacrAB and high PmutS expression (Fig. 3A and movie S1). We quantified PacrAB and PmutS expression and growth rates across many growing microcolonies (n = 3213 cells) and again observed an inverse relationship between PacrAB expression and PmutS expression (Fig. 3B). Overlaying the growth rate onto these data, we found that the slowest-growing cells were those with high PacrAB and low PmutS expression (Fig. 3, B to D). Measurements with the AcrAB-RFP and MutS-YFP translational fusion strain also showed slower growth in this subpopulation of cells (fig. S7 and movie S2).

Fig. 3. Reduced growth rate in single cells with high PacrAB and low PmutS expression.

(A) Time-lapse microscopy images of wild-type cells expressing PacrAB-rfp + PmutS-yfp. Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) PacrAB-rfp expression versus PmutS-yfp expression in the wild-type strain. The purple dots correspond to cells whose growth rate falls in the bottom 10% of those measured. (C) PacrAB-rfp expression and (D) PmutS-yfp expression versus the growth rate in the wild-type strain. (E) ΔacrB cells expressing PacrAB-rfp and PmutS-yfp. (F) PacrAB-rfp expression versus PmutS-yfp expression in ΔacrB cells. (G) PacrAB-rfp expression and (H) PmutS-yfp expression versus the growth rate in the ΔacrB strain. Red lines in (C), (D), (G), and (H) plot the mean fluorescence of cells binned across growth rate in increments of 0.004 min−1, where each bin has a minimum of 15 cells. Error bars, ± SEM. Negative growth rates arise when the automated cell identification process identifies a cell in a subsequent frame as having a smaller number of pixels; however, this is an infrequent event (~2% of cells). Values in (B) to (D) and (F) to (H) are expressed in arbitrary units.

Growth rate–dependent effects disappeared in a ΔacrB background, with cells growing at similar rates across all levels of PacrAB expression (Fig. 3E and movie S3). Quantification across microcolonies confirmed this finding, and growth rates were roughly constant, regardless of PacrAB or PmutS expression (Fig. 3, F to H). Together, these results demonstrate that acrAB expression affects single-cell growth rates and that cell-to-cell differences in pump expression result in a subpopulation of cells with high PacrAB expression, low PmutS expression, and a low growth rate.

The AcrAB efflux pump is regulated by the transcription factor MarA (29). Mutations in marA and its regulator marR frequently arise in clinical isolates and antibiotic resistance studies (30, 31). In addition, MarA expression is heterogeneous and dynamic within isogenic single cells, and its stochastic expression is associated with elevated transient resistance (5, 32). Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting, we found that cells with higher marA expression were more mutation prone than those with low marA expression and that this effect was due predominantly to the AcrAB pump (fig. S8 and supplementary text).

These results demonstrate a link between transient resistance and heterogeneity in spontaneous mutation frequencies. Our findings indicate that the AcrAB efflux pump, which plays a known role in multidrug resistance, can also affect the initial stages of the evolution of permanent antibiotic resistance. Our results suggest that heterogeneity in AcrAB is correlated with expression of the mismatch repair enzyme MutS in individual cells and that elevated levels of acrAB expression decrease the growth rate. In our work, this role for AcrAB was shown in the absence of antibiotic stress, so these differences in mutation frequency are not induced by antibiotic treatment.

Even modest increases in the mutation rate can drive the evolution of resistance under selective pressure. For instance, weak mutator phenotypes have been shown to play a critical role in the evolution of resistance to ciprofloxacin in E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus (16, 33). Achieving resistance to clinical levels of antibiotics is often a multistep process, requiring several mutational events. As an example, acrAB-related genes, including the regulators acrR, marR, soxR, and marA, appeared frequently in a microbial evolution and growth arena (MEGA)–plate study in which E. coli evolved resistance to trimethoprim (30).

Our findings open the door for further studies of the molecular mechanism by which AcrAB affects mutation frequency. Mutation rates have been shown to depend on the cell growth rate and population density (26, 27). Given the link between pump expression and growth, it is likely that other growth-related phenomena are influenced by single-cell–level differences in pump expression. Efflux pumps may contribute to increases in the mutation rate by influencing growth alone or by exporting compounds involved in cell-to-cell interactions and the methyl cycle (13). Multidrug efflux pumps and DNA repair enzymes are widespread (20, 34, 35). Understanding the initial evolutionary trajectory of resistant strains may suggest strategies for treating infections, such as combination therapies involving antibiotics and efflux pump inhibitors (36).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Del-Rio at the University of Vermont and B. Tilton at the Boston University Flow Cytometry Facilities for assistance. F. Stirling and P. Silver kindly provided the Salmonella strain. We thank J. Collins, N. Emery, A. Gutierrez, S. Jain, A. Khalil, J.-B. Lugagne, N. Rossi, T. Wang, and W. Wong for helpful discussions and manuscript critiques.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01AI102922 and R21AI137843.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: Data have been archived at Dryad (37).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Alekshun MN, Levy SB, Cell 128, 1037–1050 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin BR, Rozen DE, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 4, 556–562 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulcahy LR, Burns JL, Lory S, Lewis K, J. Bacteriol 192, 6191–6199 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S, Science 305, 1622–1625 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Meouche I, Siu Y, Dunlop MJ, Sci. Rep 6, 19538 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pu Y et al. , Mol. Cell 62, 284–294 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergmiller T et al. , Science 356, 311–315 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levin-Reisman I et al. , Science 355, 826–830 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Mamun AA et al. , Science 338, 1344–1348 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li XZ, Plésiat P, Nikaido H, Clin. Microbiol. Rev 28, 337–418 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hobbs EC, Yin X, Paul BJ, Astarita JL, Storz G, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109, 16696–16701 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tikhonova EB, Zgurskaya HI, J. Biol. Chem 279, 32116–32124 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krašovec R et al. , Nat. Commun 5, 3742 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langevin AM, Dunlop MJ, J. Bacteriol 200, e00525–17 (2017).29038251 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicoloff H, Perreten V, Levy SB, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1293–1303 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orlén H, Hughes D, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 50, 3454–3456 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds MG, Genetics 156, 1471–1481 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oethinger M, Kern WV, Jellen-Ritter AS, McMurry LM,Levy SB, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 44, 10–13 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohnert JA et al. , J. Bacteriol 190, 8225–8229 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denamur E, Matic I, Mol. Microbiol 60, 820–827 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uphoff S et al. , Science 351, 1094–1097 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robert L et al. , Science 359, 1283–1286 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uphoff S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, E6516–E6525 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu TH, Marinus MG, J. Bacteriol 176, 5393–5400 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood KB, Cluzel P, BMC Syst. Biol 6, 48 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krašovec R et al. , PLOS Biol 15, e2002731 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimura I, Kurokawa M, Liu L, Ying BW, mBio 8, e00676–17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng G, Tsui HC, Winkler ME, J. Bacteriol 178, 2388–2396 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbosa TM, Levy SB, J. Bacteriol 182, 3467–3474 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baym M et al. , Science 353, 1147–1151 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maneewannakul K, Levy SB, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 40, 1695–1698 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi NA, Dunlop MJ, PLOS Comput. Biol 13, e1005310 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S, Wang Y, Shen J, Wu Y, Wu C, FEMS Microbiol. Lett 341, 13–17 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh P, Yamane K, Mech. Ageing Dev 129, 391–407 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gottesman MM, Pastan IH, Natl J. Cancer Inst 107, djv222 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams KN et al. , Cell 145, 39–53 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Meouche I, Dunlop MJ, Data for: Heterogeneity in efflux pump expression predisposes antibiotic-resistant cells to mutation, Dryad; (2018); 10.5061/dryad.n1h9d0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.