ABSTRACT

The spindle assembly checkpoint prevents chromosome mis-segregation during mitosis by delaying sister chromatid separation. Several F-box protein members play critical roles in maintaining genome stability and regulating cell cycle progress via ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. Here, we showed that Fbxo6 critically regulated spindle checkpoint and chromosome segregation. Fbxo6 was phosphorylated during mitosis. Overexpression of Fbxo6 lead to faster exit from nocodazole-induced mitosis arrest through premature sister chromatid separation. Moreover, we found substantially more binuclear and multilobed nuclei cells accompanied with impaired cell viability in Fbxo6-overexpressed HeLa cells. Mechanistically, Fbxo6 interacted with spindle checkpoint proteins including Mad2 and BubR1 leading to the premature exit from mitosis. Overall, we revealed a novel role of Fbxo6 in regulating spindle checkpoint, which may shed light on the regulation of genome instability of cancer cells.

KEYWORDS: Mitosis, F-box protein, Fbxo6, spindle checkpoint, Mad2, BubR1

Introduction

Cell cycle progression including cellular growth, genomic replication, and division of genetic material is tightly controlled by Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) to prevent misregulation that often causes birth defects or tumorigenesis [1,2]. Cdks are activated upon the binding of cyclin subunits [3]. The periodic synthesis and proteolysis of cyclins ensure an oscillation in Cdk activity among phases in cell cycles, which is necessary for transition between phases of cell cycle [4]. Abundance of cyclins are precisely regulated by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis [5,6].

E3 ubiquitin ligases mediate the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzymes to the substrates in the three-enzyme cascade [7,8]. The E3 ubiquitin ligases are classified into the single-subunit RING-finger type, the multi-subunit RING-finger type, and the HECT-domain type [9]. The SCF (Skp1–Cullin1–F-box protein) complex is a member of the multi-subunit RING-finger type with clearly defined structure and functions [10]. The Cullin1 subunit interacts at the N terminus with the Skp1 (S-phase-kinase-associated protein-1) subunit, which binds to F-box proteins (FBPs) that dictate the substrate specificity of the ubiquitin ligase [11–13].

FBPs superfamily includes 70 members [14], several of which played critical roles in cell cycle control, such as Fbxw1 (Beta-TrcP) [15], Fbxw5 [16], Fbxw7 [17], Fbxl1 (Skp2) [18], Fbxl2 [19], Fbxo4 [20], Fbxo5 [21] and Fbxo31 [22]. However, the function of FBPs during mitosis remains unclear. It was reported that Fbxo6-dependent Chk1 degradation contributes to S phase checkpoint termination, and the a defect in this mechanism might increase tumor cell resistance to certain anticancer drugs [23]. In our previous studies, we systematically identified the Fbxo6-interacting glycoproteins by utilizing protein purification combined with LC/MS [24]. In this study, using an unbiased screening, we found that Fbxo6 was phosphorylated in mitosis. Overexpressing Fbxo6 significantly induced premature cell division and bypass of spindle checkpoint. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that Fbxo6 interacted with the spindle checkpoint protein BubR1 via its FBA domain. Our results provide insight that overexpression of Fbxo6 may contribute to the genome instability of cancer cells.

Results

Fbxo6 is phosphorylated during mitosis

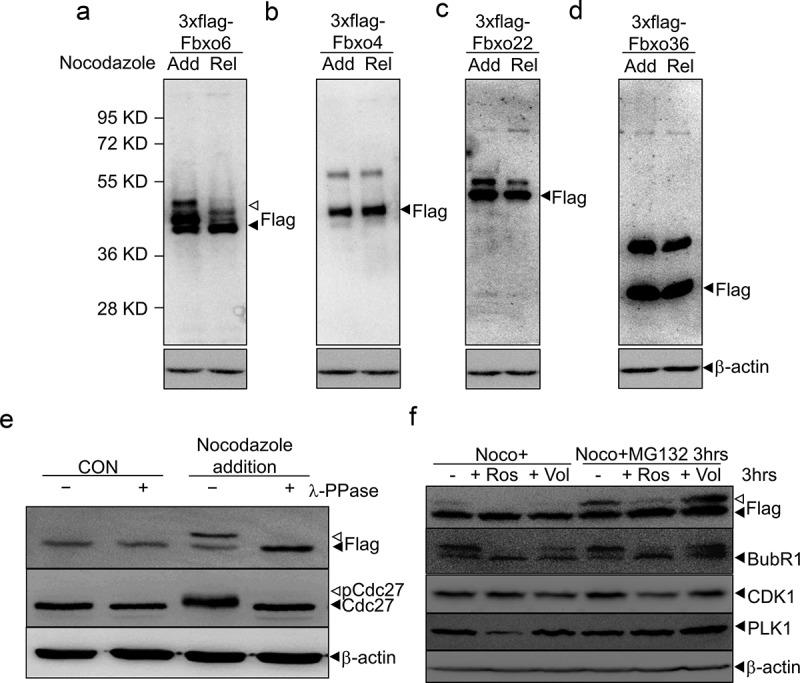

To identify the FBPs related with mitosis, we transfected several FBPs into HEK293 cells, treated cells with nocodazole to synchronize cells to mitosis, and removed nocodazole to release cells from mitosis. We observed a band of higher molecular weight than Fbxo6 (35 kD) upon the addition of nocodazole, and this extra band disappeared when cells were released from nocodazole (Figure 1(a)). Intriguingly, we did not detect the extra band in other FBPs, such as Fbxo4, Fbxo22 or Fxbo36 when cells were treated with nocodazole (Figure 1(b–d)). These results indicate that Fbxo6 protein may be modified during mitosis.

Figure 1.

Fbxo6 is phosphorylated during mitosis. (a-d) HEK293 cells were transfected with flag-tagged Fbxo6 (a), Fbxo4 (b), Fbxo22 (c) or Fbxo36 (d) for 24 hours, respectively. Then the cells were treated with nocodazole (200 ng/ml) for 16 hours (Add for addition) and released for 8 hours (Rel for release). The cells were collected and equal amounts of cell lysates were blotted for anti-flag antibody. (e) HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells were treated with or without nocodazole (200 ng/ml) for 16 hours. Cell lysates were collected in the presence or absence of lambda protein phosphatase (λ-ppase) and the indicated proteins were examined by western blot. (f) HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells were treated with nocodazole (200 ng/ml) for 16 hours, and then with or without MG132 (20 μM) for another 3 hours. At the meantime, cells were treated with Roscovitine (20 μM) or Volasertib (50 nM) for 3 hours as well, and the indicated proteins were examined by western blot.

To examine whether the extra band of Fbxo6s that migrated slower in SDS-PAGE was due to phosphorylation of Fbxo6, we established a stable line overexpressing flag-Fbxo6 (HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cell line). We then synchronized HeLaflag-Fbxo6 and incubated cellular extracts with lambda phosphatase (λ-PPase) (+) or mock (–). As expected, nocodazole treatment induced phosphorylation of Cdc27, which was removed by the addition of λ-PPase. Similarly, the extra band of Fbxo6 induced by nocodazole was removed by the incubation with λ-PPase (Figure 1(e)) [25]. These results indicate that Fbxo6 was phosphorylated in mitosis.

To explore the kinase that phosphorylates Fbxo6 during mitosis, we tested PLK1 and CDK1, the master regulators of mitosis [26]. After arresting HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells at mitosis with nocodazole, we treated cells with Roscovitine (CDK1 inhibitor) [27] or Volasertib (PLK1 inhibitor) [28]. To avoid CDK1 and PLK1 inhibitors treatment-induced cell exited from mitosis, we treated cells with MG132, a widely used proteasome inhibitors. We found after 3 hours of Roscovitine or Volasertib treatment in mitosis, the phosphorylated Fbxo6 band disappeared. With MG132 addition, only Roscovitine treatment removed the phosphorylated Fbxo6 band (Figure 1(f)). These results showed that Fbxo6 was phosphorylated by CDK1 in mitosis.

Phosphorylation of Fbxo6 is dynamically regulated in cell cycle

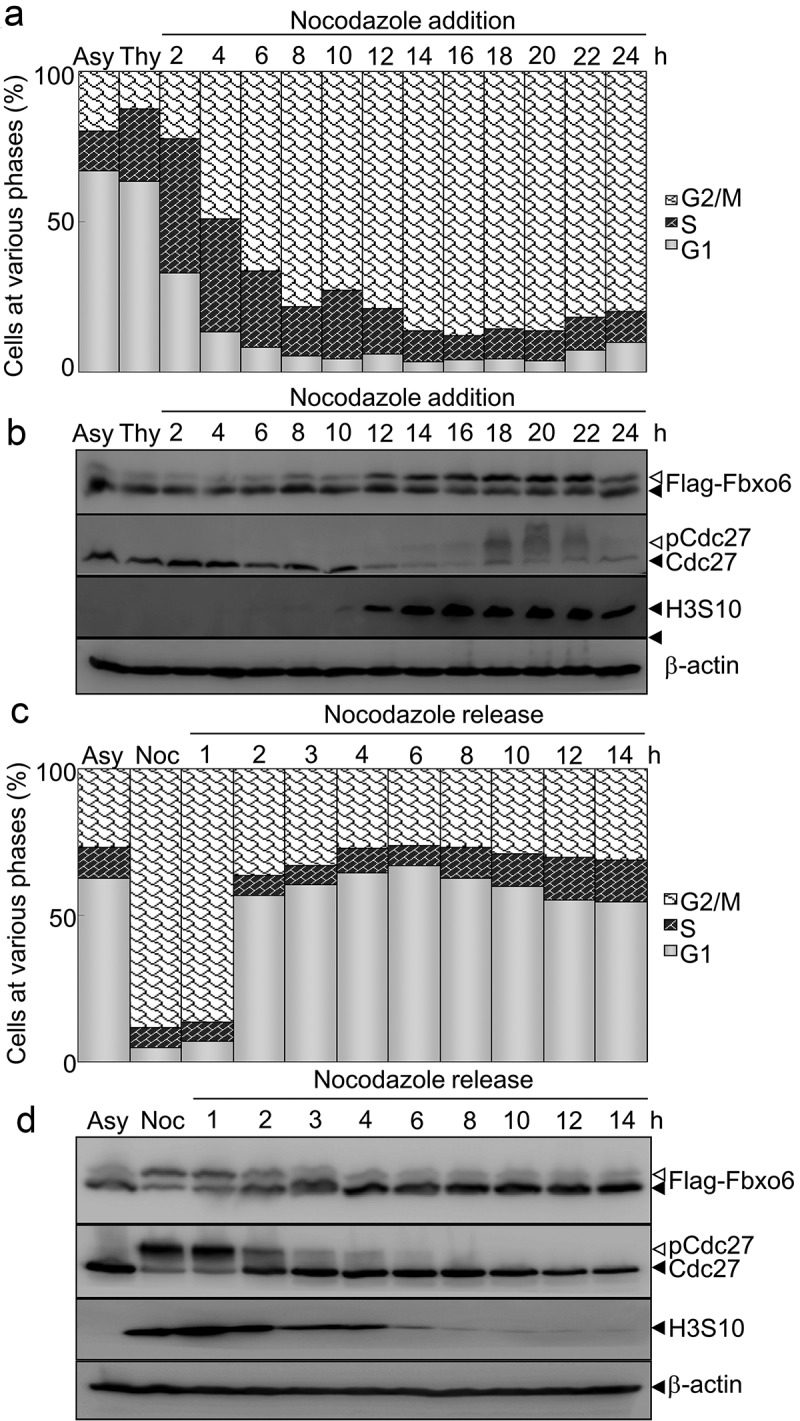

To examine whether the phosphorylation of Fbxo6 is dynamically regulated in cell cycle, we measured expression of Fbxo6 in different phases of cell cycle by arresting HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells at G1/S phase with thymidine, followed with releasing into nocodazole containing medium (Figure 2(a)). In a time-dependent manner, nocodazole increased Fbxo6 phosphorylation (Figure 2(b)). We also found the similar results in endogenous Fbxo6 in A549 cells (Figure S1). In line with these observations, we detected declined Fbxo6 phosphorylation when cells were released from mitosis (Figure 2(c–d)).

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of Fbxo6 is dynamically changing in cell cycle. (a) HeLa cells stably transfected with flag-Fbxo6 (HeLaflag-Fbxo6) were treated with thymidine (Thy) (2.5 mM) for 24 hours followed by nocodazole (200 ng/ml) treatment for the various times as indicated. DNA content of the treated cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (Asy for asynchronized HeLaflag-Fbxo6cells). (b)The indicated proteins were examined by western blot. (c) HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells were treated with nocodazole (Noc, 200 ng/ml) for 16 hours and then released for the various times as indicated. DNA content of the treated cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (d) The indicated proteins were examined by western blot.

Overexpression of Fbxo6 induces premature sister-chromatid separation without affecting proliferation of HeLa cells

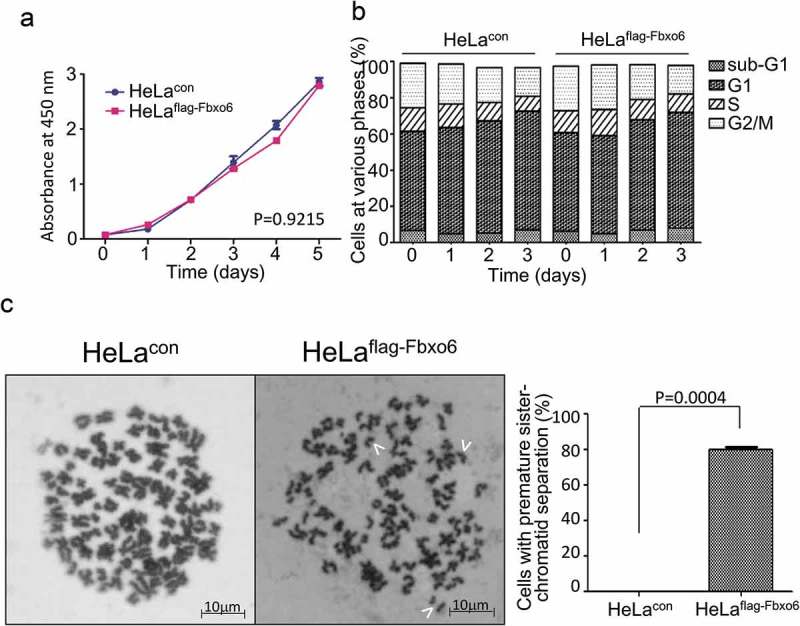

Next, we investigated the function of Fbxo6 by comparing proliferation of HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells to HeLacon with CCK-8 assay. Fbox6 overexpression did not change proliferation, viability or cell cycle distribution of HeLa cells (P = 0.9215) (Figure 3(b)).

Figure 3.

Overexpression of Fbxo6 induces premature sister-chromatid separation. (a) The proliferation rate of HeLacon and HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells for 5 days were analyzed by CCK8 assay. (b) DNA content of HeLacon and HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells for 3 days was analyzed by flow cytometry. (c) HeLacon and HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells were treated with nocodazole (200 ng/ml) for 16 hours. Mitotic chromosome spreads were prepared and stained by Wright-Giemsa dye. Arrows indicate prematurely separated sister chromatids. Representative images were shown. The percentages of cells with premature sister-chromatid separation were analyzed. P = 0.0004 vs, control group.

Since Fbxo6 was involved in DNA damage response [23], we next explored whether Fbxo6 regulates genomic stability by comparing mitotic chromosome spreads of HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells to HeLacon cells. As shown in Figure 3(c), Fbxo6 overexpression in HeLa cells induces premature sister-chromatid separation. Significantly, compared with HeLacon cells, nearly 80% Helaflag-Fbxo6cells showed single sister-chromatid.

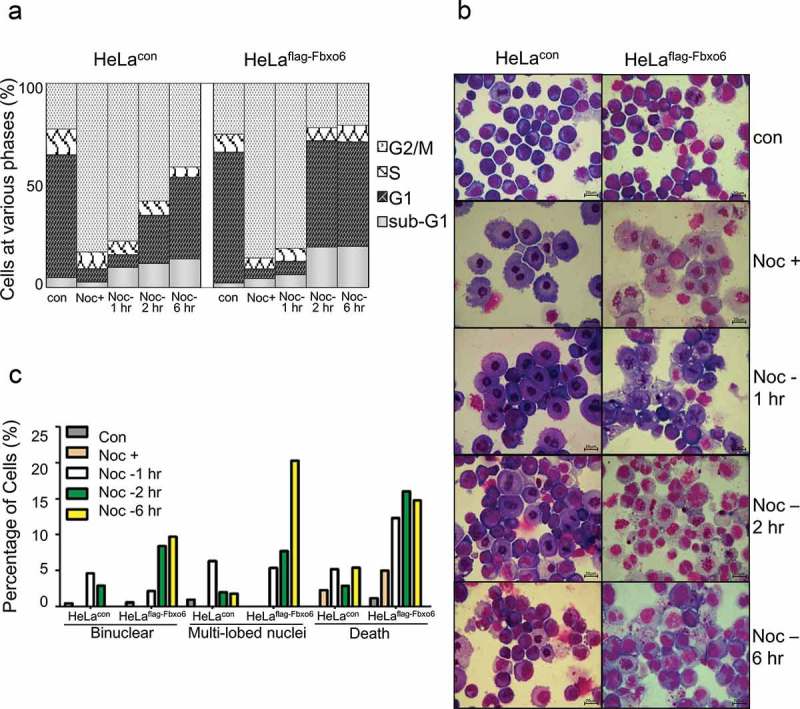

Overexpression of Fbxo6 accelerates the exit from mitosis after release from nocodazole treatment

Since sister-chromatid separation is a hallmark of late stage of mitosis, we hypothesized that Fbxo6 was implicated in mitosis exit. To test this possibility, we synchronized HeLaflag-Fbxo6 or HeLacon cells at mitosis by nocodazole for 16 hours and then released cells from mitosis for 1, 2 or 6 hours (Figure 4(a)). Interestingly, our FACS analysis showed that the population of HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells in G2/M phase greatly decreased after nocodazole withdrawal. This effect is probably due to a faster mitosis exit. Moreover, HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells showed an increased percentage of apoptotic population starting from 2 hours after nocodazole release, as evidenced by increased sub-G1 contents (Figure 4(a)), suggesting exacerbated cell death HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells during or after mitosis exit. To investigate the changes in nucleus of cells with Fbxo6 overexpression in mitosis, we analyzed HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells arrested at or released from mitosis by Wright-Giemsa staining (Figure 4(b–c)). Six hours after nocodazole release, HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells showed morphologically defected cells including binuclear cells (10%), multi-lobed nuclei cells (21%) and dead cells (15%). In contrast, all these defected cell populations were below 5% in HeLacon cells. Taken together, these data suggest that Fbxo6 accelerated mitosis exit.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of Fbxo6 accelerates the exit from mitosis in nocodazole-released cells. HeLacon and HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells were treated with nocodazole (200 ng/ml) and then released for the various times as indicated. (a) DNA content of the treated cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (b) Cells treated in (a) were stained by Wright-Giemsa dye. Representative images were shown. (c) Percentages of cells with binuclear and multi-lobed nuclei, as well as dead cells were counted from cells treated in (a).

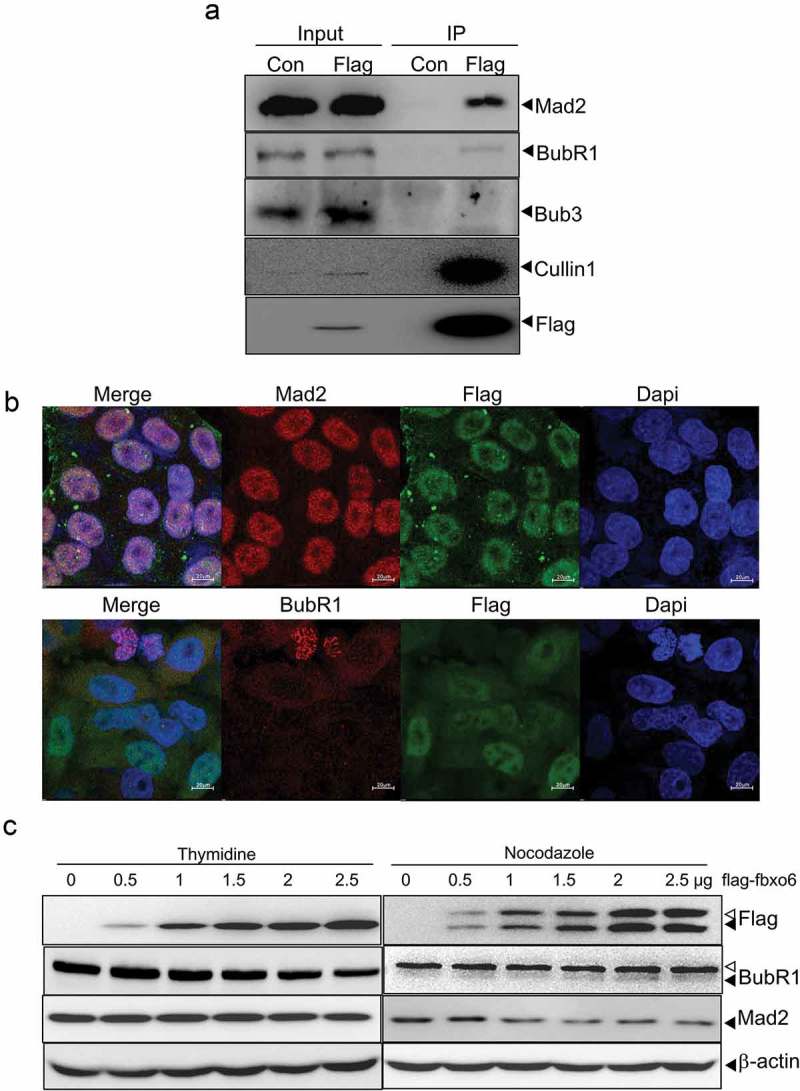

Fbxo6 interacts with spindle check point proteins BubR1 and Mad2

The spindle checkpoint prevents chromosome mis-segregation by delaying sister chromatid separation until all chromosomes achieve bipolar attachment to the mitotic spindle [29]. We hypothesize that spindle checkpoint bypass contributed to the premature exit of mitosis caused by Fbxo6. To investigate if Fbxo6 regulates spindle checkpoint, we first tested whether Fbxo6 interacts with spindle checkpoint components. We effectively pulled down Cullin1, a molecular scaffold of SCF complex, in HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells but not in HeLacon cells (Figure 5(a)). We further examined several spindle checkpoint components in the elutes co-immunoprecipitated with flag-Fbxo6. Only BubR1 and Mad2 but not Bub3 were efficiently pulled down with flag-Fbxo6. The data was confirmed by immunofluorescent staining showing that Fbxo6 co-localized with Mad2 and BubR1 (Figure 5(b)). In A549 cells, we also detected the co-localization of endogenous Fbxo6 with Mad2 or BubR1 (Figure S2).

Figure 5.

Fbxo6 interacts with spindle check point proteins. (a) Lysates from HeLacon and HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells stably expressing flag-con or flag-Fbxo6 were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel. Bound proteins were eluted with FLAG peptide and subjected to Western blot with BubR1, Mad2, Bub3, Cullin1 and flag antibodies. (b) HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells were stained with Mad2 or BubR1 (Red), Fbxo6 (Green) and Dapi (Blue). (c) HeLa cells were transfected with flag-Fbxo6 at different dosages, and also arrested by thymidine (2.5 mM) at G1/S phase or by nocodazole (200 ng/ml) at G2/M phase. The indicated proteins were examined by western blot.

Since FBPs govern substrate recognition of ubiquitin ligase, we hypothesized that Fbxo6 affected the stability of Mad2 and BubR1 via interacting with them. To test whether Fbxo6 reduces the protein level of Mad2 or BubR1, we performed western blot in HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells transfected with increasing dosages of flag-Fbxo6 and arrest cells with thymidine or nocodazole. We found that BubR1 protein decreased at G1/S phase, and Mad2 protein decreased at G2/M phase with the increasing expression of Fbxo6. These data indicate that Fbxo6 inhibited the expression of BubR1 and Mad2 at different phases of cell cycle (Figure 5(c)).

Discussion

Other than regulating the stability of Chk1 during DNA damage checkpoint recovery [23], the functions of Fbxo6 are largely unknown. In this study, we demonstrated, for the first time, that the phosphorylation of Fbxo6 fluctuated in cell cycle, both in endogenous form or exogenously expressed. Network of protein phosphorylation including CDKs or histones dynamically controls cell cycle transitions [30–32]. We showed that Fbxo6 was phosphorylated by CDKs, especially by CDK1 which plays an important role in mitosis [33]. Moreover, overexpression of Fbxo6 accelerates the exit of mitosis by interacting with spindle checkpoint proteins such as BubR1 and Mad2.

Unexpectedly, overexpression of Fbxo6 has minor effort on either the morphology or cell cycle distribution of asynchronous HeLa cells. It is likely that in asynchronous cells, the effect of Fbxo6 in mitosis was subtle and below detection without activation of spindle checkpoint. Intriguingly, data from nocodazole-treated HeLa cells overexpressing Fbxo6 revealed that Fbxo6 was able to induce premature sister-chromatid separation and accelerate the exit from mitosis. These data suggest that Fbxo6 plays a role in the critical event at late stage of mitosis. When released from nocodazole, HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells sped up mitosis exit, and showed more defective cells with abnormal karyotypes like binuclear and multilobe nuclear, indicating the disruption of chromosome separation. Besides, more cell death was observed in HeLaflag-Fbxo6 cells, which reflects more severe mitotic catastrophe. Faithful chromosome segregation requires that each chromatid pair achieves bipolar attachment to the mitotic spindle before segregation [34,35]. Failure to attach to the spindle correctly before anaphase onset results in unequal chromosome segregation, which may lead to cell death or disease afterwards [36,37]. Taken together, these data suggest that Fbxo6 is involved in the regulation of spindle checkpoint activation.

Chromosome segregation is initiated by the activation of an E3 ubiquitin ligase APC and its cofactor Cdc20 [38]. The spindle checkpoint is a surveillance mechanism that delays anaphase onset by delaying the activation of APC/Cdc20, until all chromosomes are correctly attached in a bipolar fashion to the mitotic spindle [39]. The core spindle checkpoint proteins such as Mad1, Bub1, Bub3 and BubR1, are usually recruited to unattached kinetochores, and facilitate the binding of Mad2 and BubR1 to Cdc20, thereby inhibiting the activity of APC/Cdc20 [40,41]. Our data showed that Fbxo6 interacted with both Mad2 and BubR1 but not with Bub3, suggesting a direct role of Fbxo6 in regulating spindle checkpoint. Moreover, we found that Fbxo6 decreased BubR1 and Mad2 at different phases of cell cycle, which adds complexity of the mechanism by which Fbxo6 regulated spindle checkpoint. We previously demonstrated that Fbxo6 interacted with multiple glycosylated proteins via its F box associated (FBA) domain [24]. Additionally, Fbxo6 was involved in the ERAD pathway by targeting unfolded glycoproteins for destruction [42]. Interestingly, we found that Fbxo6 interacted with BubR1 mainly through its F-box domain and FBA domain (Figure S3). It is likely that the E3 ligase activity of Fbxo6 was involved in regulating spindle checkpoint. Moreover, glycosylation, especially O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine was implicated in cell cycle regulation [43]. Interfering the O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine protein modification leds to severe defects in mitotic progression and cytokinesis [44]. Thus, we inferred that BubR1 or Mad2 might be glycoproteins. We provide the novel insight that Fbxo6 may disturb the spindle checkpoint activation through interacting with glycosylated BubR1 or Mad2, which warrant further investigation.

Aneuploidy is a hallmark of aggressive tumors and often arises from errors during chromosome segregation [37]. It has been previously reported that Fbxo6 can promote the growth and proliferation of certain cancer cells [45]. Our results suggest that overexpression of Fbxo6 may contribute to tumorigenesis via disrupting the chromosome segregation.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that Fbxo6 is a novel regulator of mitosis by controlling chromosome separation via interacting with the spindle checkpoint proteins Mad2 and BubR1. Our study sheds light on the mechanisms of cell cycle regulation and provides novel potential target for cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell treatment

HeLa and A549 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FBS, Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) at 37°C with 5% CO2. For morphological observations, cells were transferred onto slides with cytospin (Shandon, Runcorn, UK), stained with Wright-Giemsa dye (BASO Diagnostic Inc., Shanghai, China), and examined under a light microscope (Olympus BX-51, Olympus Optical, Japan). Lambda Protein Phosphatase was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and processed according to the datasheet.

Plasmids

Fbxo6, Fbxo4, Fbxo22 and Fbxo36 were amplified from HEK293T cells by PCR and cloned into the pBabe-3 × Flag retroviral vector. All cDNAs were completely sequenced. Fbxo6 full length (FL), Fbxo6 N-terminal (N), Fbxo6 C-terminal (C) or F-box associated domain of Fbxo6 (FBA) were constructed as described in reference25.

Flow cytometry analysis (FACS)

To analyze cellular DNA content by flow cytometry, 1 × 106 cells were collected, rinsed and fixed overnight with 75% cold ethanol at −20°C. Cells were then treated with 100 μg/ml RNase A in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) and stained with 25 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) using CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences). Ten thousand cells were acquired and analyzed for the DNA content.

Western blot

Cells were treated with nocodazole (200 ng/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) or thymidine (2.5 mM, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for various periods of time. Cells were harvested and lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM DTT, 2% w/v SDS, 10% glycerol). Protein extracts were equally loaded on a 6–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, electrophoresed, and blotted on to Immobilon-NC membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in PBS, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse antibodies against Flag M2 (Sigma-Aldrich), cyclin B1 (Abcam, UK), Fbxo6, Cdc27, Cullin1 (Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-Histone H3 (Ser10) (Upstate Biotechnology Inc, Lake placid, NY) or with rabbit antibodies against Mad2 (Bethyl Laboratories Inc, Montgomery, TX), and BubR1 (Novus, Littleton, CO), Bub3 (Santa Cruz, CA), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). Specific signals were detected by chemiluminescence (Cell Signaling). The same blots were re-probed with anti-β-actin antibody (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) as loading control.

Co-immunoprecipitation

HeLa cells were stably transfected with pBabe-3 × Flag-con, Fbxo6 FL/N/C/FBA or co-transfected with HA-BubR1. Cells were collected and lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P40, Roche complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail) for 20 min with gentle rocking at 4°C. Lysates were cleared using centrifugation (13000 rpm, 10 min), the supernatant was filtered through 0.45 μm spin filters (Millipore) to further remove cell debris, and the resulting material was subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with 25 μL of anti-FLAG M2 affinity resin (Sigma) or HA agarose beads(Sigma) overnight at 4°C with gentle inversion. Resin containing immune complexes was washed with 1 mL ice cold lysis buffer 8 times. Proteins were eluted with 2 × SDS.

Chromosome spreads

To obtain mitotic chromosome spreads, cells were treated with nocodazole (200 ng/mL) for 16 hours. Rounded-up cells were collected and suspended in a fixative solution (glacial acetic acid/methanol in a ratio of 1:3) prior to spreading onto slides, Slides with cell spread were stained with Wright-Giemsa dye.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China [No.2017YFA0505200]; National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) [NO.2015CB910403]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [81570118, 81570112, 31401185, 81773018]; Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality [15401901800]; Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission [13YZ028].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Aguilera A, García-Muse T.. Causes of genome instability. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47:1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Draviam VM, Xie S, Sorger PK.. Chromosome segregation and genomic stability. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14(2):120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Malumbres M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014;15(6):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Satyanarayana A, Kaldis P. Mammalian cell-cycle regulation: several Cdks, numerous cyclins and diverse compensatory mechanisms. Oncogene. 2009;28(33):2925–2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tyers M, Jorgensen P. Proteolysis and the cell cycle: with this RING I do thee destroy. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10(1):54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Murray A. Cyclin ubiquitination: the destructive end of mitosis. Cell. 1995;81(2):149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chernorudskiy AL, Gainullin MR. Ubiquitin system: direct effects join the signaling. Sci Signal. 2013;6(280):pe22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yamao F. Ubiquitin system: selectivity and timing of protein destruction. J Biochem. 1999;125(2):223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ardley HC, Robinson PA. E3 ubiquitin ligases. Essays Biochem. 2005;41:15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Craig KL, Tyers M. The F-box: a new motif for ubiquitin dependent proteolysis in cell cycle regulation and signal transduction. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1999;72(3):299–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kipreos ET, Pagano M. The F-box protein family. Genome Biol. 2000;1(5):REVIEWS3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bai C, Sen P, Hofmann K, et al. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell. 1996;86(2):263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Orlicky S, Tang X, Willems A, et al. Structural basis for phosphodependent substrate selection and orientation by the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2003;112(2):243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang Z, Liu P, Inuzuka H, et al. Roles of F-box proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(4):233–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Frescas D, Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(6):438–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pagan J, Pagano M. FBXW5 controls centrosome number. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(8):888–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bailey ML, Singh T, Mero P, et al. Dependence of human colorectal cells lacking the FBW7 tumor suppressor on the spindle assembly checkpoint. Genetics. 2015;201(3):885–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kitagawa K, Kitagawa M. The SCF-type E3 ubiquitin ligases as cancer targets. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2016;16(2):119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chen BB, Glasser JR, Coon TA, et al. Fbxl2 is a ubiquitin E3 ligase subunit that triggers mitotic arrest. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(20):3487–3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lin DI, Barbash O, Kumar KG, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin D1 by the SCF(FBX4-alphaB crystallin) complex. Mol Cell. 2006;24(3):355–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Vaidyanathan S, Cato K, Tang L, et al. In vivo overexpression of Emi1 promotes chromosome instability and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2016;35(41):5446–5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Santra MK, Wajapeyee N, Green MR. F-box protein Fbxo31 mediates cyclin D1 degradation to induce G1 arrest after DNA damage. Nature. 2009;459(7247):722–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang YW, Brognard J, Coughlin C, et al. The F box protein Fbx6 regulates Chk1 stability and cellular sensitivity to replication stress. Mol Cell. 2009;35(4):442–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liu B, Zheng Y, Wang TD, et al. Proteomic identification of common SCF ubiquitin ligase Fbxo6-interacting glycoproteins in three kinds of cells. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(3):1773–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang L, Fujita T, Wu G, et al. Phosphorylation of the anaphase-promoting complex/Cdc27 is involved in TGF-beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(12):10041–10050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Li Z, Zhang X. Kinases involved in both autophagy and mitosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(9):1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jorda R, Paruch K, Krystof V. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors inspired by roscovitine: purine bioisosteres. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(20):2974–2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Van BJ, Lardon F, Deschoolmeester V, et al. Spotlight on volasertib: preclinical and clinical evaluation of a promising Plk1 inhibitor. Med Res Rev. 2016;36(4):749–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yao Y, Dai W. Mitotic checkpoint control and chromatin remodeling. Front Biosci. 2012;17:976–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fisher D, Krasinska L, Coudreuse D, et al. Phosphorylation network dynamics in the control of cell cycle transitions. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(20):4703–4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Suryadinata R, Sadowski M, Sarcevic B. Control of cell cycle progression by phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) substrates. Biosci Rep. 2010;30(4):243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhang B, Dong Q, Su H, et al. Histone phosphorylation: its role during cell cycle and centromere identity in plants. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2014;143(1–3):144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Adhikari D, Liu K, Shen Y. Cdk1 drives meiosis and mitosis through two different mechanisms. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(15):2763–2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].de Medina-Redondo M, Meraldi P. The spindle assembly checkpoint: clock or domino? Results Probl Cell Differ. 2011;53:75–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Silva P, Barbosa J, Nascimento AV, et al. Monitoring the fidelity of mitotic chromosome segregation by the spindle assembly checkpoint. Cell Prolif. 2011;44(5):391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gordon DJ, Resio B, Pellman D. Causes and consequences of aneuploidy in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(3):189–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Santaguida S, Amon A. Short- and long-term effects of chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(8):473–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Manchado E, Eguren M, Malumbres M. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C): cell-cycle-dependent and -independent functions. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38(Pt1):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kim S, Yu H. Mutual regulation between the spindle checkpoint and APC/C. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22(6):551–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Logarinho E, Bousbaa H. Kinetochore-microtubule interactions “in check” by Bub1, Bub3 and BubR1: the dual task of attaching and signalling. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(12):1763–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Musacchio A, Hardwick KG. The spindle checkpoint: structural insights into dynamic signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(10):731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yoshida Y, Tokunaga F, Chiba T, et al. Fbs2 is a new member of the E3 ubiquitin ligase family that recognizes sugar chains. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(44):43877–43884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sampathkumar SG, Jones MB, Meledeo MA, et al. Targeting glycosylation pathways and the cell cycle: sugar-dependent activivy of butyrate-carbohydrate cancer prodrugs. Chem Biol. 2006;13(12):1265–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Slawson C, Zachara NE, Vosseller K, et al. Perturbations in O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine protein modification cause severe defects in mitotic progression and cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(38):32944–32956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhang L, Hou Y, Wang M, et al. study on the functions of ubiquitin metabolic system related gene FBG2 in gastric cancer cell line. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.