ABSTRACT

Metastatic melanoma is a significant clinical problem with a 5-year survival rate of only 15–20%. Recent approval of new immunotherapies and targeted inhibitors have provided much needed options for these patients, in some cases promoting dramatic disease regressions. In particular, antibody-based therapies that block the PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitory pathway have achieved an increased overall response rate in metastatic melanoma, yet durable response rates are reported only around 15%. To improve the overall and durable response rates for advanced-stage melanoma, combined targeted and immune-based therapies are under investigation. Here, we investigated how the natural products called schweinfurthins, which have selective anti-proliferative activity against many cancer types, impact anti-(α)PD-1-mediated immunotherapy of murine melanomas. Two different compounds efficiently reduced the growth of human and murine melanoma cells in vitro and induced plasma membrane surface localization of the ER-resident protein calreticulin in B16.F10 melanoma cells, an indicator of immunogenic cell death. In addition, both compounds improved αPD-1-mediated immunotherapy of established tumors in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice either by delaying tumor progression or resulting in complete tumor regression. Improved immunotherapy was accomplished following only a 5-day course of schweinfurthin, which was associated with initial tumor regression even in the absence of αPD-1. Schweinfurthin-induced tumor regression required an intact immune system as tumors were unaffected in NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice. These results indicate that schweinfurthins improve αPD-1 therapy, leading to enhanced and durable anti-tumor immunity and support the translation of this novel approach to further improve response rates for metastatic melanoma.

KEYWORDS: Schweinfurthin, PD-1, melanoma, mice, immunotherapy

Introduction

Immunotherapy is rapidly being adopted as first or second line therapy for the treatment of cancer. In particular, therapies targeting the programmed death 1 (PD-1) checkpoint inhibitor pathway have shown impressive results in a number of cancers, including metastatic melanoma, leading to FDA approval of antibody-based therapies specific for PD-1 or its ligand PD-L1.1-3 The PD-1:PD-L1 interaction inhibits T cell survival and function, leading to reduced T cell function, eventual T cell exhaustion, and a poorer anti-tumor response.4 PD-1/PD-L1-specific antibodies block the interaction between PD-1 on the surface of T cells with PD-L1 on the surface of a tumor or antigen presenting cell, restoring T cell function. In malignant melanoma, the success of αPD-1 therapy is associated with the presence of intratumoral CD8+ T cells5 and an IFNγ gene signature.6 Thus, approaches that lead to recruitment of tumor-specific T cells into the tumor microenvironment may improve checkpoint inhibitor therapy.7,8

Despite this important advance in melanoma therapy, the durable response rate following αPD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy remains at only 15–20%.9,10 One strategy under investigation to improve the overall and durable response rates toward immunotherapy is combination with existing and novel drugs.11 Currently, ongoing clinical trials are examining the effects of αPD-1 in combination with anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated molecule-4 (αCTLA-4; ipilimumab), chemotherapy, radiation and αVEGF therapies to treat various types of cancer.11 For metastatic melanoma, combination αPD-1 and αCTLA-4 regimens were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) based on data showing that Nivolumab synergized with Ipilimumab, particularly among patients with PD-L1 negative tumors, resulting in a greater benefit compared to either monotherapy.12,13 Our recent work demonstrates a survival benefit among metastatic melanoma patients treated with immunotherapy who were also prescribed pan β-blockers,14 a mechanism that can improve checkpoint blockade therapy in pre-clinical models.14,15 Pre-clinical studies performed in clinically relevant melanoma models support the idea that combining αPD-1-based immune therapy with targeted therapies, such as mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, can improve the overall response rate.16,17 Based on this evidence, we sought to find possible synergy between αPD-1 and a novel cancer therapeutic agent.

We have previously studied the potential cancer therapeutic activity of a family of natural products and synthetic derivatives known as the schweinfurthins. Schweinfurthin compounds were isolated from tropical plants of genus Macaranga,18-20 and were investigated by the National Cancer Institute (NCI),21 our group, and others for anticancer activity. Early reports from the NCI as well as from our program indicated that these compounds show selective activity against specific tumor types as established within the NCI’s 60 human cancer cell line panel.22-29 Cell lines derived from glioblastoma, renal cancer, and melanoma are highly susceptible to schweinfurthins, while cells derived from lung and ovarian cancers are typically resistant. This type of activity, with little or no overlap with the pattern displayed by known agents, indicates a novel mechanism.30 Schwienfurthins impact cholesterol metabolism through their effects on the mevalonate pathway31, which supplies isoprenoid intermediates for the synthesis of cholesterol. Since targeting the mevalonate pathway can influence the immune response,32,33 we hypothesized that schweinfurthins may improve existing immunotherapies used to treat cancer. In this report, we evaluated the ability of schweinfurthins to improve immunotherapy in a murine melanoma tumor model that is resistant to αPD-1 monotherapy.

Results

TTI-3114 and TTI-4242 reduce human melanoma cell line proliferation in vitro

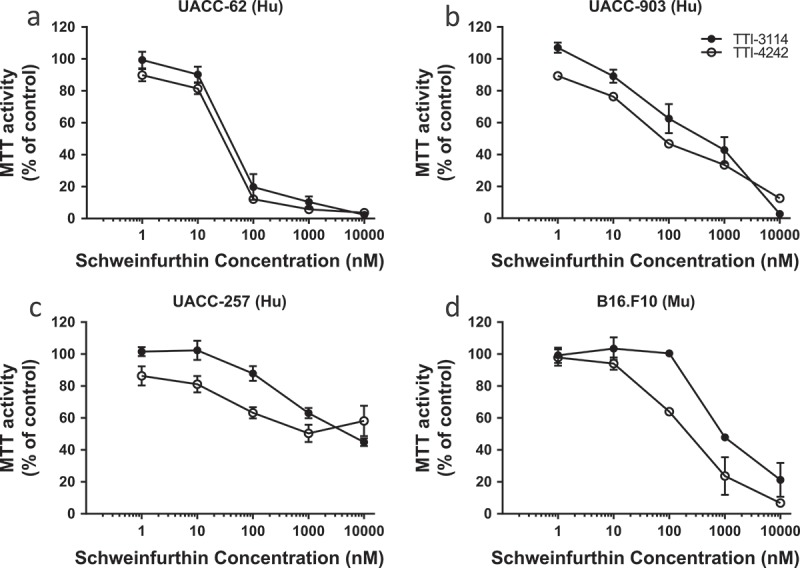

In order to test the activity of the schweinfurthins in melanoma we used a group of three human melanoma cell lines: UACC-62, UACC-903 and UACC-257. All three cell lines express the BRAF V600E mutation. Two of these lines are included in the NCI 60 cell panel, one of which (UACC-62) showed susceptibility to TTI-4242, and one of which (UACC-257) was resistant.34 We have recently published the activity of TTI-3114 in a rat model of chondrosarcoma which has served as our therapeutic lead compound.35 TTI-4242 was chosen as a model of second generation schweinfurthin analogs designed to improve the solubility and other drug-like properties of the series.34,36 These two compounds, TTI-4242 and TTI-3114, show highly correlated anticancer phenotypes in the NCI 60 cell line screen suggesting that they exert their anticancer effects through a similar mechanism. When measuring mitochondrial activity as a sign of proliferation, we saw the same pattern; both TTI-4242 and the compound TTI-3114 (Methylschweinfurthin G) showed strong activity against the UACC-62 line (EC50 = 10–100 nM, Figure 1(a)), weaker activity against the cell line UACC-903 (EC50 = 100–1000 nM, Figure 1(b)) and the weakest activity against the cell line UACC-257 (EC50 = 1000–10,000 nM, Figure 1(c)).

Figure 1.

Schweinfurthins reduce viability of human and murine melanoma cells in vitro. Human melanoma cell lines UACC-62 (a), UACC-903 (b), and UACC-257 (c) and murine melanoma cell line B16.F10 (d) were treated with varying concentrations of the schweinfurthin analogs TTI-3114 and TTI-4242 for 48 hours. The viability of cells was measured by MTT assay. Data represent mean ± SEM.

We also tested these two compounds against the aggressive murine melanoma cell line B16.F10 in vitro (Figure 1(d)). In this model, TTI-4242 demonstrated activity with an EC50 in the 100–1000 nM range comparable to that in the UACC-903 cell line, while TTI-3114 showed less efficacy.

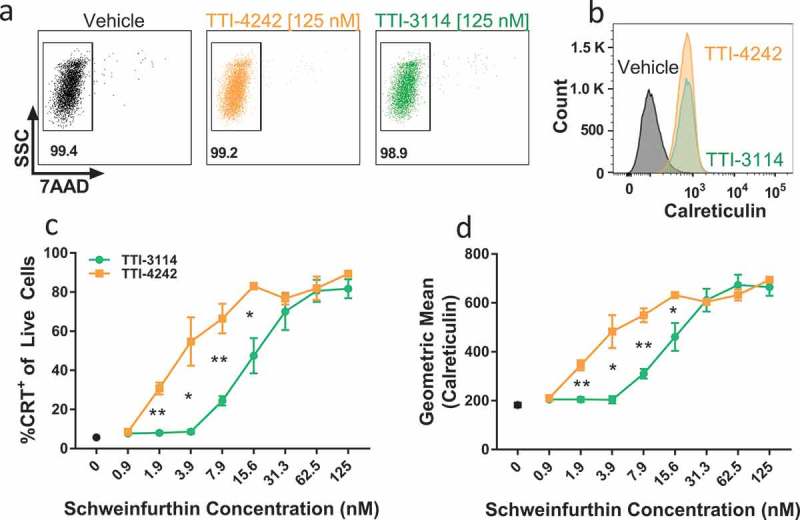

TTI compounds induce calreticulin surface expression in murine melanoma cells in vitro, indicative of immunogenic tumor cell death

The induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD) in tumor cells is associated with the generation of protective anti-tumor immunity, a process associated with activation of antigen presenting cells that subsequently trigger tumor-reactive T cells.37 Multiple chemotherapeutic drugs as well as ionizing radiation have been shown to induce ICD, promoting protective anti-tumor activity (reviewed in38). Some of the hallmarks of ICD are localization of the endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein calreticulin to the plasma membrane, which serves as an “eat me” signal for phagocytes,39 release of ATP, which triggers cell chemotaxis and release of the high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1), a proinflammatory trigger.37 We evaluated the dose response of calreticulin surface expression on B16.F10 melanoma cells, derived from C57BL/6 mice, to the schweinfurthin analogs TTI-4242 and TTI-3114. After 24 hours of treatment, a high proportion of cells remained viable (Figure 2(a)) but both compounds robustly induced surface calreticulin within the viable cell population (Figure 2(b–d)). Both the percentage of cells expressing calreticulin (Figure 2(c)) and the level of calreticulin expression (Figure 2(d)) increased in a dose-dependent manner. TTI-3114 induced surface calreticulin expression at concentrations above 8 nM while TTI-4242 maintained this effect down to 2 nM (Figure 2(d)). We also found that B16.F10 cells treated with TTI-3114 displayed a dose-dependent decrease in intracellular ATP with a corresponding increase in extracellular ATP (Supplementary Figure 1), indicative of ATP release. These results indicated that schweinfurthin analogs induced multiple characteristics consistent with the induction of ICD, raising the possibility that schweinfurthins may synergize with immunotherapy for melanoma in vivo.

Figure 2.

Schweinfurthins induce expression of surface calreticulin. B16.F10 cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of TTI-4242, TTI-3114 or DMSO control for 24 hours. Surface calretuculin was measured by flow cytometry. (a) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing cell viability as measured by 7AAD staining from samples treated with 125 nM schweinfurthin or vehicle control. Numbers represent the percentage of live cells from single cell gate. (b) Representative flow cytometry histograms from samples treated with 125 nM schweinfurthin or vehicle control. (c-d) Points represent 3 replicate concentrations ± SEM. Black dot represents calreticulin surface staining on cells treated only with vehicle. The results are representative of two independent experiments. Significant differences between TTI-3114 and TTI-4242 were determined by Student’s t test and are shown for values that are * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

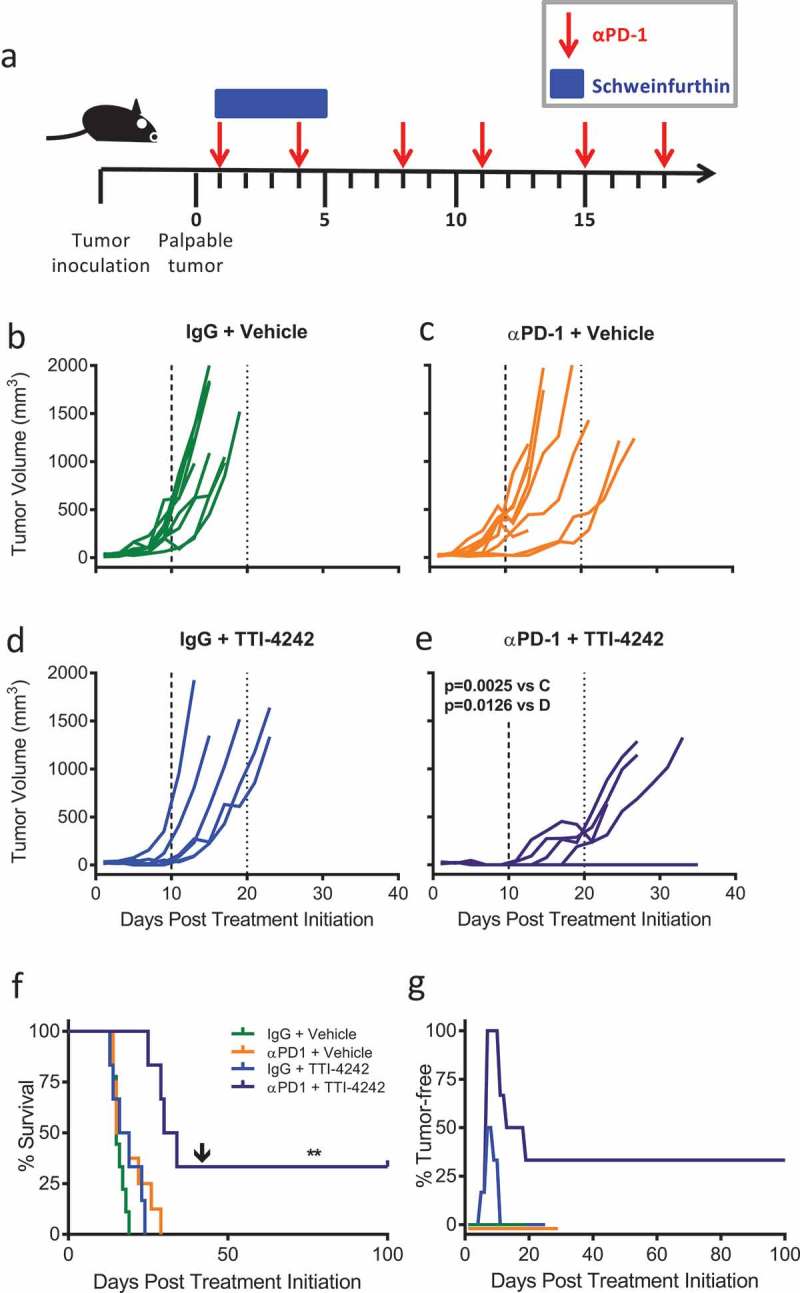

TTI-4242 administration improves αPD-1 therapy by delaying melanoma progression and inducing durable anti-tumor immunity

We tested how schweinfurthin compound TTI-4242 impacted the efficacy of clinically relevant αPD-1 immunotherapy. C57BL/6 mice were implanted with B16.F10 cells subcutaneously. Once tumors became palpable, mice were randomized into four treatment groups: (1) control IgG + Vehicle, (2) αPD-1 + Vehicle, (3) IgG + TTI-4242, and (4) αPD-1 + TTI-4242. Control IgG or αPD-1 antibody were administered twice a week for a total of 6 treatments and TTI-4242 or vehicle control was administered for the first five days (Figure 3(a)). We observed that tumor growth in control treated mice (Figure 3(b)) was not significantly impacted by either αPD-1 alone (Figure 3(c)) or TTI-4242 alone (Figure 3(d)). However, when αPD-1 and TTI-4242 were provided in a combined therapeutic regimen (Figure 3(e)), tumor growth was significantly delayed compared to αPD-1 alone (Figure 3(c)) and TTI-4242 alone (Figure 3(d)). In addition, mice receiving dual αPD-1 and TTI-4242 lived significantly longer than mice in all other treatment groups (Figure 3(f)). We also observed that 50% and 100% of tumors in the TTI-4242 alone and αPD-1 + TTI-4242 groups, respectively, showed initial tumor regression during the period of TTI-4242 administration (Figure 3(g)). After 42 days, 33.3% (N = 2) of mice in the combined therapy group remained tumor-free and receipt of a second, larger dose of 5 × 105 B16.F10 tumor cells did not result in new tumor growth for at least an additional 60 days (Figure 3(f–g)). Taken together, these findings suggest that combined αPD-1 and TTI-4242 provides a greater anti-tumor response than either treatment alone, in some cases leading to complete and durable tumor regression and protective immunity to re-challenge.

Figure 3.

TTI-4242 improves tumor control in mice treated with αPD-1 therapy. (a) Experimental scheme; B16.F10 tumor-bearing mice received 200μg αPD-1 twice a week for three weeks and/or schweinfurthin (30 mg/kg TTI-4242) for five consecutive days. Control mice received 200μg rat IgG or an equivalent volume of vehicle. Once tumors became palpable (~ 20mm3), mice were treated with (b) IgG and vehicle, (c) αPD-1 and vehicle, (d) IgG and TTI-4242, (e) αPD-1 and TTI-4242. Days 10 and 20 are indicated with long- and short-dashed lines. N = 6–9/group; p values determined by mixed linear models and shown for pairwise comparisons to αPD-1 + TTI-4242. (f) Kaplan-meier survival analysis. Arrow indicates the day of challenge (day 42). N = 6–9/group; p values determined by log rank test; pairwise comparisons between αPD-1 + TTI-4242 and all other groups: ** p < 0.01. (g) The percentage of mice tumor-free (no palpable or visually apparent tumor) in each treatment group. The experiment was terminated at 100 days post treatment initiation at which point all surviving mice were tumor free.

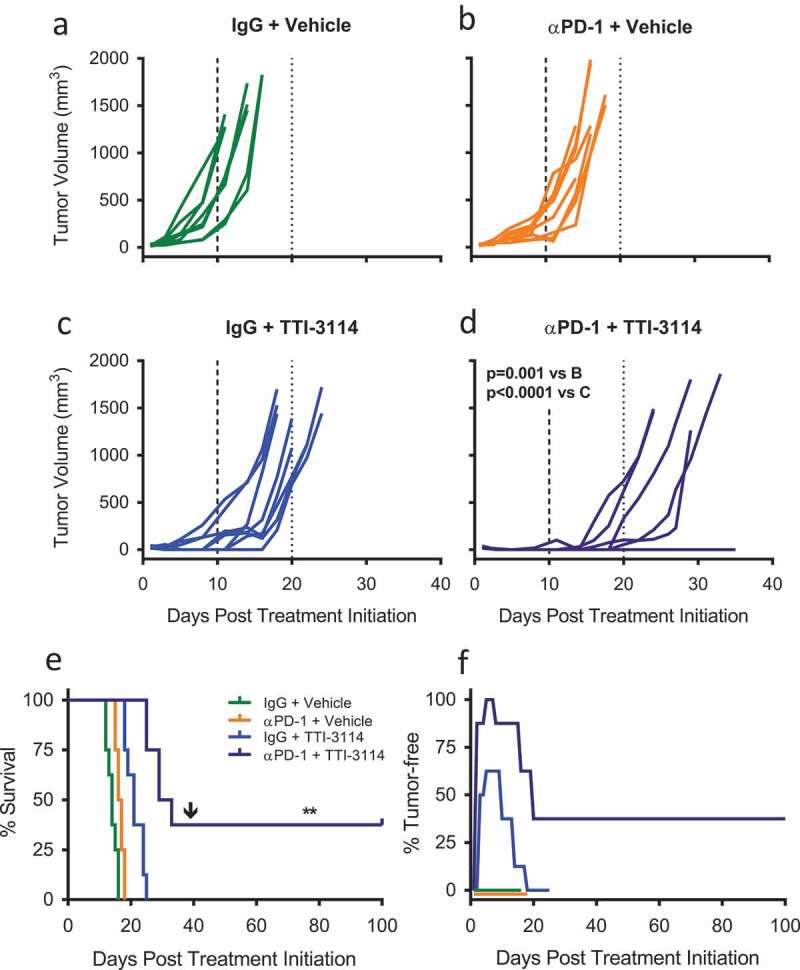

TTI-3114 administration induces initial tumor regression and durable tumor control with αPD-1 therapy

To extend our in vivo results beyond a single schweinfurthin compound, we tested the efficacy of TTI-3114 with αPD-1 therapy of B16.F10 tumors since this compound showed a similar, albeit less potent effect on cell proliferation and calreticulin surface expression in vitro (Figure 1). We used the same experimental design depicted in Figure 3(a) to treat B16.F10 tumor-bearing mice with αPD-1 in combination with TTI-3114. Tumor growth in control treated mice (Figure 4(a)) was similar to that of mice treated with either αPD-1 (Figure 4(b)) or TTI-3114 (Figure 4(c)). Dual αPD-1 + TTI-3114 (Figure 4(d)) significantly delayed tumor growth compared to either monotherapy. This combination therapy also significantly extended survival compared to all other treatment groups (Figure 4(e)). Similar to the results with TTI-4242, 60% and 100% of mice that received TTI-3114 alone or in combination with αPD-1, respectively, showed initial tumor regression (Figure 4(f)) and 37.5% (N = 3) of mice that received combination therapy remained tumor free, even following challenge with a second dose of B16.F10 cells (Figure 4(e–f)).

Figure 4.

TTI-3114 in combination with αPD-1 delays tumor growth. Mice were treated according to the schedule in Figure 3(a) using TTI-3114 (20 mg/kg). Once tumors became palpable (~ 20mm3), mice were treated with (a) IgG and vehicle, (b) αPD-1 and vehicle, (c) IgG and TTI-4242, (d) αPD-1 and TTI-4242. Days 10 and 20 are indicated with long- and short-dashed lines. N = 6–9/group; p values determined by mixed linear models and shown for pairwise comparisons to αPD-1 + TTI-3114. (e) Kaplan-meier survival analysis. Arrow indicates the day of challenge (day 39). N = 6–9/group; p values determined by log rank test; pairwise comparisons between αPD-1 + TTI-4242 and all other groups: ** p < 0.01. (f) The percentage of mice tumor-free (no palpable or visually apparent tumor) in each treatment group. The experiment was terminated at 100 days post treatment initiation at which point all surviving mice were tumor free.

In order to determine if the immune system plays a role in the initial TTI-3114-driven tumor regression, we tested the efficacy of TTI-3114 against B16.F10 tumors in immune compromised NSG mice which lack functional B, T and NK cells among other immune deficiencies.40,41 There was no effect of TTI-3114 on the survival of B16.F10 tumor-bearing NSG mice (Supplementary Figure 2A) nor were any tumor regressions observed (Supplementary Figure 2B). These findings suggest that TTI-3114-induced melanoma regression is immune-mediated.

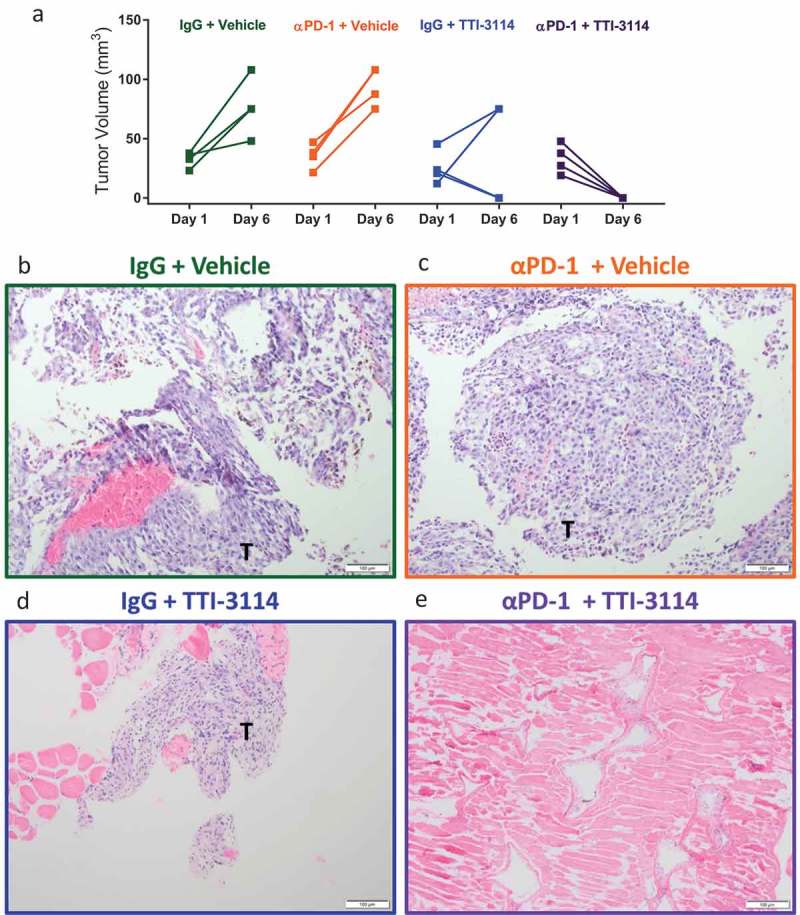

Tumor regression observed in αPD-1 + TTI-3114 treated mice is accompanied by complete histological regression

We next determined the extent of histological tumor regression in mice treated with TTI-3114. Tumor-bearing mice were treated for five days according to the schedule in Figure 3(a). We measured palpable tumors on the first day of treatment and on day 6 when tumors or tissue underlying the area where the tumors had regressed were collected. H&E stained tissue sections were prepared for evaluation by a board-certified dermatopathologist. Consistent with data in Figures 3 and 4, tumors progressed in vehicle treated mice, while tumors became undetectable by day 6 in 50% (2/4) and 100% (4/4) of mice that received IgG + TTI-3114 and αPD-1 + TTI-3114, respectively (Figure 5(a)). All mice treated with vehicle, with or without αPD-1, had visible tumor upon histological analysis (Figure 5(b,c) and Supplementary Figure 3A, B). Of the four mice treated with IgG + TTI-3114, three mice had detectable tumors by H&E staining (Figure 5(d)) while no tumor cells were observed in one mouse. Evaluation at higher magnification revealed that tumors from mice treated with Vehicle (Supplementary Figure 3A) or αPD-1 + Vehicle (Supplementary Figure 3B) consisted of sheets of atypical melanocytes while areas of tumor from mice treated with IgG + TTI-3114 were less dense, with less melanin and pleomorphism and contained lymphocytic infiltrate (Supplementary Figure 3C, D). 50% of mice (2/4) treated with αPD-1 + TTI-3114 had no detectable tumors by H&E staining (Figure 5(e)), while the remaining mice had areas of residual necrotic tumor tissue with infiltrating lymphocytes (Supplementary Figure 3E, F). Thus 5 days of treatment with TTI-3114 alone induced tumor regression associated with lymphocytic inflamation but residual tumor cells remained that quickly recurred. The addition of αPD-1, however, promoted a more effective histological regression. Taken together, we found that a short duration of treatment with TTI-3114 improved αPD-1 immunotherapy against an aggressive murine melanoma and resulted in histologically complete responses in a subset of mice.

Figure 5.

TTI-3114 promotes histological regression of B16.F10 tumors. Mice were treated as described in Figure 3(a). (a) Tumor size was determined at days 1 and 6 of treatment. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (b-e) Representative images from H&E stained sections of formalin fixed tumors (b-d) or a regressed lesion (e) are shown. (b, c) Tumors from mice treated with vehicle, with or without αPD-1, show sheets of pleomorphic melanocytes characteristic for melanoma. (d) Representative image of residual tumor from a mouse treated with TTI-3114 alone. (e) Representative image of mice treated with αPD-1 + TTI-3114 having no detectable tumor. Magnification 10x, scale bar represents 100 μm, T = tumor.

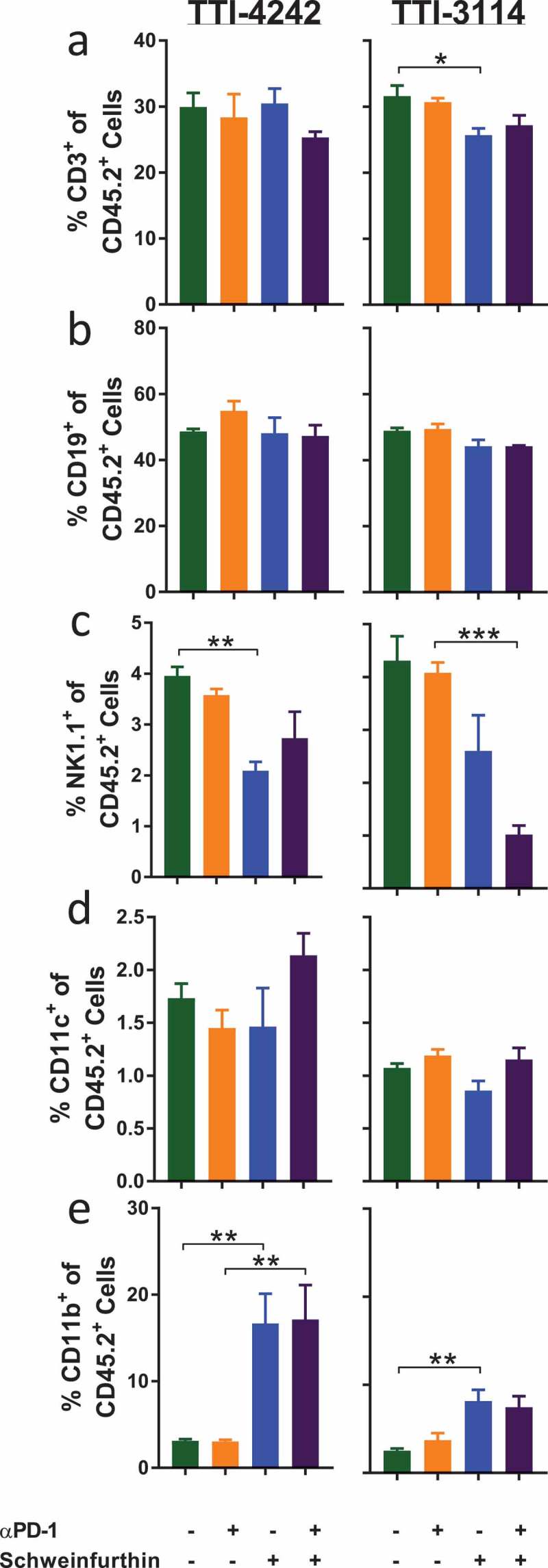

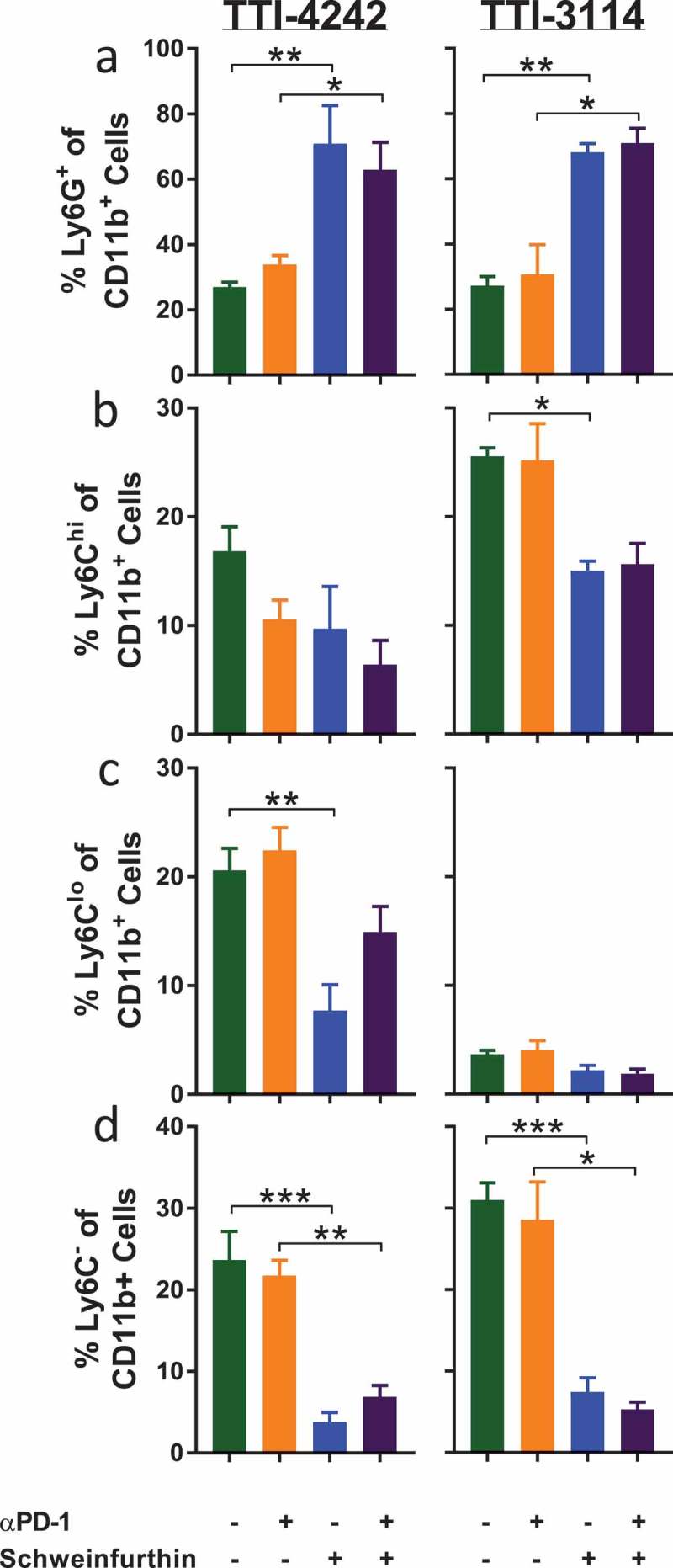

Schweinfurthins skew the systemic immune cell profile of B16.F10 tumor-bearing mice

We evaluated how short-duration treatment with schweinfurthins impacted the composition of immune cells in the spleen of tumor-bearing mice as a measure of the systemic effects of treatment. To capture the effects of schweinfurthin administration at a time when tumors initially regressed, we evaluated immune cell subsets in the spleen at 24 hours after the fifth day of consecutive treatment using multicolor flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 4). Since most tumors had completely regressed at this time point in mice that received schweinfurthins, we were unable to compare the immune profile within the tumors themselves. We examined the major subsets of cells including T cells, B cells, NK cells, and myeloid cells. We did not find any consistent changes in the frequencies of total CD3+ T cells (Figure 6(a)) or CD19+ B cells (Figure 6(b)) or among the subsets of CD4+ (Supplementary Figure 5A) or CD8+ (Supplementary Figure 5B) T cells between the treatment groups. However, we did observe a decrease in the fraction of NK1.1+ cells (Figure 6(c)). The frequency of CD11c+ cells appeared unaffected by either schweinfurthin tested (Figure 6(d)). We consistently observed an increase in the proportion of CD11b+ myeloid cells following administration of schweinfurthin (Figure 6(e)). Although this difference was most prominent with TTI-4242, treatment with TTI-3114 showed a trending, albeit less significant, increase in CD11b+ cells. Within the CD11b+ subset, we observed a significant and consistent increase in Ly6G+ cells in mice treated with either schweinfurthin (Figure 7(a)). Further, while no consistent effect was detected for Ly6Chi (Figure 7(b)) or Ly6Clo (Figure 7(c)) cells, the Ly6G−Ly6C− subset of CD11b+ cells was dramatically decreased with treatment by either TTI-4242 or TTI-3114 (Figure 7(d)). These results indicate that systemic administration of schweinfurthin induces changes within the cellular composition of the spleen, primarily altering the frequencies of CD11b+ cell subsets. Despite some differential effects by the two analogs on spleen composition, both provided a similar anti-tumor effect.

Figure 6.

Schweinfurthins skew splenic immune cell subsets. Mice were treated for 5 days according to the schedule in Figure 3(a). On day 6, spleens were harvested and processed for flow cytometry analysis. Samples were gated on CD45+ 7AAD− cells to show percentage of (a) CD3+, (b) CD19+ and (c) NK1.1+CD3− (d) CD11c+ cells and (e) CD11b+ cells. Data represent mean ± SEM; N = 3–5/group; p values determined by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 7.

Schweinfurthins skew splenic myeloid cell subsets. Cells from Figure 6 were further gated on CD45+ 7AAD− CD11b+ cells to show percentage of (a) Ly6G+, (b) Ly6G−Ly6Chi, (c) Ly6G−Ly6Clo and (d) Ly6G−Ly6C− cells. Data represent mean ± SEM; N = 3–5/group; p values determined by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Discussion

Tumor immunotherapy using αPD-1/PD-L1 antibodies has become the standard treatment for metastatic melanoma due to its ability to induce clinical regression of disease.1,2 However, only a small subset of these patients experience durable complete responses (upper bound of ~20%).9,10 As it is difficult to identify patients that will achieve this therapeutic benefit, approaches that expand the clinical efficacy of αPD-1 therapy to additional patients are urgently needed. Immune related adverse events (irAEs) also represent a hurdle to effective treatment of patients with αPD-1 targeted therapies. irAEs range from mild to fatal, although the rate of high grade irAEs is uniformly ~20% across cancer types.42 Combination treatments that additively, or synergistically, improve αPD-1 therapy would be beneficial in two major ways; by increasing the proportion of patients who benefit and by reducing the incidence of irAEs, potentially by shortening the course of therapy. Currently, combinations of αPD-1 with targeted therapies, radiation, as well as some drugs that induce ICD such as doxorubicin and oxaliplatin are being explored in this context.11

Here we demonstrate that schweinfurthins induce transient tumor regression in a murine model of melanoma but can combine effectively with αPD-1 immunotherapy to promote durable complete tumor regressions. This anti-tumor response to the combined treatment with αPD-1 was quite robust and consistent, inducing a complete and durable response in > 30% of mice. This is a highly significant result given that αPD-1 monotherapy has no benefit in the B16.F10 model. In addition, two schweinfurthin analogs, TTI-4242 and TTI-3114, had a similar impact on tumor progression in this model, indicating that the outcome is a class effect.

Schweinfurthins are known to modulate several aspects of cholesterol metabolism,31 but their anti-tumor properties are only partially defined. While lovastatin directly inhibits the first enzyme of cholesterol synthesis, β-Hydroxy β-methylglutaryl-conenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, schweinfurthins indirectly reduce the synthesis of cholesterol while also increasing cholesterol export.43 Others have provided evidence that the schweinfurthins promote cholesterol export by modulating oxysterol signaling and perturbing the trans-Golgi network.44,45 We have demonstrated that schweinfurthins induce tumor cells to behave as if they have a surfeit of cholesterol, even when this critical metabolite is limiting.31 Treatment of glioblastoma cells with 3-deoxyschweinfurthin B led to reduction in HMG-CoA reductase but also promoted increased cholesterol efflux and reduced cholesterol import. Thus, schweinfurthins have a broader impact on cholesterol regulatory mechanisms than some of the more well-characterized cholesterol inhibitors.

There are several possible ways that schweinfurthins could enhance the efficacy of αPD-1 therapy including induction of ICD, elimination of regulatory cells or direct targeting of effector immune cells. Our results suggest that schweinfurthins could trigger anti-tumor immunity through the induction of ICD, potentially by disrupting the Golgi apparatus. Recently, the amino acid derivative LTX-401 was found to target the Golgi apparatus causing extensive structural disturbances accompanied by activation of ICD.46 Likewise, schweinfurthins, including schweinfurthin G (closely related to TTI-3114), also disrupt the trans-Golgi network,45 providing a possible link to the induction of ICD. Additionally, Zoledronate, an inhibitor of the mevalonate pathway enzyme farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, was shown to sensitize multidrug resistant human cancer cells to the effects of doxorubicin-induced ICD which was otherwise repressed.47,48 Similar to what we observed here with schweinfurthin treatment, ICD induced by cancer chemotherapeutics is known to stimulate CD8+ T cell driven anti-tumor immunity which can sensitize tumors to checkpoint inhibitor therapy.49-51

It is also plausible that schweinfurthins modify the accumulation or activity of regulatory cells as has been demonstrated with other classes of cholesterol modulating drugs.52,53 One such drug, liver-X nuclear receptor beta (LXRβ) agonist RGX-104, which lowers cholesterol levels by inhibiting transcription of key genes of cholesterol biosynthesis (eg, HMG-CoA reductase), reduced myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC) in both tumor-bearing mice and cancer patients.54 This study also showed that RGX-104 in combination with αPD-1 elicits a greater anti-tumor effect than αPD-1 alone in vivo, but the agonist had no direct activity on T cells in vitro.54 Our data indicate that schweinfurthins induce a significant shift in myeloid cell subsets. The observed increase in splenic CD11b+ cells in schweinfurthin treated mice could be explained by recruitment of myeloid cells from the circulation. Recruitment of Ly6G+ cells most likely accounts for this increase, while Ly6C−Ly6G− cells were most significantly decreased. This finding suggests that schweinfurthins may promote a systemic inflammatory response leading to recruitment of CD11b+Ly6G+cells. Whether these cells have immune potentiating effects or negative regulatory effects remains to be determined. For example, increased numbers of MDSCs (CD11b+Gr-1+) cells in the circulation are directly related to B16.F10 recurrence following surgical resection.55 We were unable to evaluate myeloid cell accumulation within the tumors at the 6-day time point since tumors had already regressed, but we may find differences in immune cell composition at earlier times following treatment or following treatment of larger tumors.

Our observations alternatively may be explained by direct effects of schweinfurthins on effector immune cells, including T cells. The mevalonate pathway plays an important role in regulating T cell function,56,57 making cholesterol modulating strategies potential inhibitors or enhancers of T cell driven anti-tumor immunity. Pre-clinical studies in murine melanoma models show that disruption of cholesterol storage mechanisms by inhibition of the enzyme acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 (ACAT1) enhances CD8+ T-cell activity.58 Another study demonstrated that treatment of Tc9 cells with β-cyclodextrin to lower cholesterol was essential for maintaining IL-9 production, T cell persistence and antitumor effects following adoptive T cell therapy.59 This study defined that IL-9 production was inhibited by cholesterol-induced LXR activation. Our data did not reveal acute changes in splenic T cell frequencies of schweinfurthin treated mice, although we cannot rule out potential modulation of T cell function. In addition, the inability of schweinfurthins to induce initial tumor regression in NSG mice demonstrates a requirement for an intact immune system.

Our results in NSG mice contrast with those from a previous study showing that LM1 chondrosarcomas regress in immunodeficient Nu/Nu mice following treatment with only TTI-3114.35 Importantly, the IC50 for TTI-3114 inhibition of LM1 cells in vitro is 35 nM while that for B16.F10 cells is about 1 μM (Figure 1(d)). Thus, an effective in vivo dose is not likely to be safely achieved to directly kill B16.F10 cells but is achievable for targeting LM1 cells. Importantly, our current results indicate that tumor cells with low sensitivity to schweinfurthins, such as B16.F10, can still be effectively targeted in immune competent mice as demonstrated by initial tumor regression. Further triggering of the immune response by αPD-1 was able to achieve durable tumor regressions, despite this dose limitation.

A likely explanation for the tumor recurrence observed in the absence of αPD-1 is that the tumors were not completely eliminated by the short 5-day course of schweinfurthin administration alone as suggested by our histopathological observations. A longer course of schweinfurthin therapy could potentially delay the time to tumor recurrence or increase the proportion of mice that achieve initial tumor regression. Likewise, extended administration of schweinfurthin in combination with αPD-1 could further increase the proportion of mice completely protected from tumor recurrence. Taken together, we have identified schweinfurthin compounds with potent anti-tumor activity that, when combined with αPD-1 immunotherapy can induce long-lived regression of established murine melanoma. Our observations encourage further evaluation of schweinfurthin compounds into the clinic, particularly TTI-3114 and TTI-4242, in combination with αPD-1 therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

UACC-62, UACC-903, and UACC-257 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, Utah) and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. UACC-62 and UACC-903 cells were obtained from the NCI-Frederick Cancer DCTD Tumor/Cell Line Repository. UACC-903 cells were a generous gift from Dr. Jeffrey Trent (Research Director and President, Translational Genomics Research Institute, Phoenix, AZ). The murine melanoma B16.F10 cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CRL 6475).

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a cell density of 3,000 (B16.F10), 5,000 (UACC-62/UACC-903) or 8,000 (UACC-257) cells per well in RPMI media with 10% FBS. The following day, media was replaced with phenol red-free RPMI containing 10% FBS and indicated concentrations of TTI-3114 and TTI-4242. Vehicle treatment consisted of 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After 44 hours of incubation, 10 ul of 5 mg/mL MTT salt (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added. Plates were incubated for an additional four hours before addition of stop solution (80% Isopropanol, 0.1 M HCl, 10% Triton X-100) to halt reduction of the MTT salt. Following overnight incubation at 37°C, the optical density of each well was measured at 570 nm and 690 nm (reference wavelength) using a SpectraMax i3x Multi-Mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Reduced values (A570-A690) are presented as percent of control.

In vitro evaluation of calreticulin expression

B16.F10 melanoma cells were seeded at 1.5–2.0 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates in RPMI-1640 medium containing standard supplements and 10% FBS and incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. Compounds solubilized in DMSO were added at the indicated concentrations and incubated for a further 24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. Control wells were treated with similar dilutions of vehicle. Cells were trypsinized and washed with FACS buffer (2%FBS + 0.1% NaN3 in PBS) and seeded at 1–2 × 105 per well in 96-well round-bottom plates. Cells were stained with rabbit anti-calreticulin polyclonal antibody (1:100, Abcam ab2907) in FACS buffer for 30 minutes at 4°C. Following two washes, cells were labeled with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500, Thermo Fisher A11070) in FACS buffer for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed twice and labeled with 7-aminoactinomysin D (7AAD; 0.25μg, BD Pharmingen 51-68981E) in order to exclude non-viable cells. All samples were immediately run on a BD LSR Fortessa flow cytometer and the data analyzed using FlowJo software.

Measurement of ATP release

Intra and extracellular release of ATP was measured using a CellTiter Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) according to manufacturer instructions. Briefly, 1 × 104 B16.F10 cells were plated in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS in white opaque 96-well tissue culture plates and cultured overnight to allow cells to adhere. TTI-3114 was diluted in media and cells were treated in duplicate. After 36 hours of treatment, culture media was collected from each well for evaluation of extracellular ATP. 100 μl of CellTiter Glo® reagent was added to each well containing cells or combined with 100 μl of collected culture media and rocked for 10 minutes to determine intracellular and extracellular ATP concentrations, respectively. Luminescence was determined using a BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader. A standard curve was generated using increasing concentrations of ATP (Sigma) and values were extrapolated using Gen5 software.

Treatment of mice and in vivo tumor growth analysis

All studies with animals were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines under a protocol approved by the Penn State College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice were bred in house and used between the ages of 6–12 weeks. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory at 6–8 weeks of age, maintained in a HEPA-filtered ventilated rack system and used within 2 weeks of receipt. Mice were housed 5 or less per cage, fed and watered ad libitum, and maintained in a 12-hour light/dark cycle. NSG mice were provided acidified water. Groups of mice were inoculated with 1 × 105 freshly cultured B16.F10 tumor cells subcutaneously in the left flank. Mice were monitored for the development of tumors and when palpable were randomized into groups. Mice received αPD-1 (clone RMP1-14; BioXCell or Leinco Technologies, Inc.) or control rat IgG (Sigma) at 200 ug/day intraperitoneally in a volume of 200ul PBS twice per week for 3 weeks. Mice received daily i.p. injections of TTI-4242 at 30 mg/kg or TTI-3114 at 20 mg/kg or vehicle only for 5 consecutive days in a total volume of 100uL. Vehicle for in vivo delivery of the schweinfurthin compounds consisted of a ternary mixture of excipients [PEG-400 (35%), propylene glycol (35%), and pluronic F68 (0.1%) by weight] in water. The excipients used are generally regarded as safe by the United States Food and Drug Administration for use in drug formulations. Tumors were measured with digital calipers and the tumor volume calculated as (length x width2)/2. Mice were euthanized when the tumor volume exceeded 1500 mm3, developed ascites or necrosis or when mice became lethargic. Where indicated, mice that exhibited complete tumor regressions were re-challenged subcutaneously in the left flank with 5 × 105 freshly cultured B16.F10 tumor cells and tumor development monitored.

Immune cell analysis

The spleens from B16.F10 treated mice were dissected into RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and maintained on ice. Spleens were processed as previously described.60 Briefly, spleens were passed through a wire mesh to form a single cell suspension. Aliquots of ~ 2 x 106 cells were stained with commercially available antibodies prior to analysis on a LSRII or LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) in the Penn State Cancer Institute Flow Cytometry Shared Resource. Samples were stained with 7AAD prior to analysis to eliminate dead cells. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (v10.4, FlowJo, LLC). Antibodies used include: CD45.2-BV480 (clone 104), CD4-APC-Cy7 (clone RM4-5), CD8-BV786 (clone 53–9.7), NK1.1-BV421 (clone PK136), CD3-PE (clone 145-2C11), CD11c-BV786 (clone HL3), CD19-APC (clone 1D3) and CD11b-PECy7 (clone M1/70), F4/80-BV711 (clone T45-2342), Ly6C-APC-Cy7 (clone AL-21), Ly6G-FITC (clone1A8). Antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences, BioLegend, eBioscience or Tonbo Biosciences. Live cells were gated on the CD45.2+/7AAD− population and a detailed gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Figure 4. The gating strategy for myeloid cells was based on Rose et al.61

Histology

Mice were euthanized and tumors were dissected from the mice (where applicable). In mice with full tumor regression, tissue underlying where the tumor had been growing was collected. This surrounding tissue was visually inspected for pigmentation prior to formalin fixation and paraffin embedding. Briefly, excised tissue was immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 24 hours followed by transfer into 70% ethanol for at least 24 hours. Tissue was embedded in paraffin, and 6 μm sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in the Penn State College of Medicine Comparative Medicine histology core lab. Stained sections were evaluated by a board certified dermatopathologist who was blinded to the sample identification. Images were collected on an Olympus BX51 Microscope using cellSense standard software.

Statistics

Differences in tumor growth curves were evaluated by linear mixed models for longitudinal analysis and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were evaluated by log rank test. Student’s t tests were used to determine the differences between treatments for in vitro studies involving two treatment groups. When four treatment groups were compared for flow cytometry studies one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test were used. p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism (version 7) or SAS (version 9.4) software.

Funding Statement

This project was supported, in part, by funds from the Penn State Cancer Institute, the Rose Dunlap Endowment and the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco CURE Funds (SAP #4100072562). The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. KMK was supported by National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health T32 CA060395.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Penn State Cancer Institute Flow Cytometry Shared Resource and the Penn State College of Medicine Comparative Medicine histology core lab for expert assistance. We also thank Terpenoid Therapeutics Inc. for supplying the schweinfurthin compounds used in these studies.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

RJH and JDN are founders, stockholders, and officers of the company Terpenoid Therapeutics Incorporated. They hold intellectual property rights to compounds being developed for treatment of human disease by the company, including schweinfurthin analogs TTI-3114 and TTI-4242. No other authors have a conflict of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- 1.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694 PMID:22658128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, Wolchok JD, Hersey P, Joseph RW, Weber JS, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133 PMID:23724846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, Kluger HM, Carvajal RD, Sharfman WH, Brahmer JR, Lawrence DP, Atkins MB, Powderly JD, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1020–1030. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0105 PMID:24590637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araki K, Youngblood B, Ahmed R.. Programmed cell death 1-directed immunotherapy for enhancing T-cell function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quan Biol. 2014. doi: 10.1101/sqb.78.019869 PMID:24415643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJ, Robert L, Chmielowski B, Spasic M, Henry G, Ciobanu V, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954 PMID:25428505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, Murphy E, Loboda A, Kaufman DR, Albright A, Cheng JD, Kang SP, Shankaran V, et al. IFN-gamma-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:2930–2940. doi: 10.1172/JCI91190 PMID:28650338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribas A, Dummer R, Puzanov I, VanderWalde A, Andtbacka RHI, Michielin O, Olszanski AJ, Malvehy J, Cebon J, Fernandez E, et al. Oncolytic virotherapy promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and improves anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;170:1109–19e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027 PMID:28886381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woo SR, Fuertes MB, Corrales L, Spranger S, Furdyna MJ, Leung MY, Duggan R, Wang Y, Barber GN, Fitzgerald KA, et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of immunogenic tumors. Immunity. 2014;41:830–842. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.017 PMID:25517615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert C, Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, Wolchok JD, Joshua AM, Hwu WJ, Weber JS, Gangadhar TC, Joseph RW, et al. Durable complete response after discontinuation of pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1668–1674. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.6270 PMID:29283791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu-Monette ZY, Zhang M, Li J, Young KH. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: have we found the key to unleash the antitumor immune response? Front Immunol. 2017;8:1597. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01597 PMID:29255458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang J, Shalabi A, Hubbard-Lucey VM. Comprehensive analysis of the clinical immuno-oncology landscape. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:84–91. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx755 PMID:29228097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Schadendorf D, Dummer R, Smylie M, Rutkowski P, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030 PMID:26027431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Wagstaff J, Schadendorf D, Ferrucci PF, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684 PMID:28889792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokolus KM, Zhang Y, Sivik JM, Schmeck C, Zhu J, Repasky EA, Drabick JJ, Schell TD.Beta blocker use correlates with better overall survival in metastatic melanoma patients and improves the efficacy of immunotherapies in mice. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1405205. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1405205 PMID:29399407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bucsek MJ, Qiao G, MacDonald CR, Giridharan T, Evans L, Niedzwecki B, Liu H, Kokolus KM, Eng JW, Messmer MN, et al. beta-adrenergic signaling in mice housed at standard temperatures suppresses an effector phenotype in CD8(+) T cells and undermines checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Cancer Res. 2017;77:5639–5651. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0546 PMID:28819022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deken MA, Gadiot J, Jordanova ES, Lacroix R, van Gool M, Kroon P, Pineda C, Geukes Foppen MH, Scolyer R, Song JY, et al. Targeting the MAPK and PI3K pathways in combination with PD1 blockade in melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1238557. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1238557 PMID:28123875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu-Lieskovan S, Mok S, Homet Moreno B, Tsoi J, Robert L, Goedert L, Pinheiro EM, Koya RC, Graeber TG, Comin-Anduix B, et al. Improved antitumor activity of immunotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors in BRAF(V600E) melanoma. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:279ra41. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4691 PMID:25787767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beutler JA, Jato J, Cragg GM, Boyd MR, Schweinfurthin D. a cytotoxic stilbene from Macaranga schweinfurthii. Nat Prod Lett. 2000;14:399–404. doi: 10.1021/np980208m PMID:9868152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beutler JA, Shoemaker RH, Johnson T, Boyd MR. Cytotoxic geranyl stilbenes from Macaranga schweinfurthii. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:1509–1512. PMID:10.1021/np980208m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoder BJ, Cao SG, Norris A, Miller JS, Ratovoson F, Razafitsalama J, Andriantsiferana R, Rasamison VE, Kingston DGI. Antiproliferative prenylated stilbenes and flavonoids from Macaranga alnifolia from the Madagascar rainforest. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:342–346. doi: 10.1021/np060484y PMID:17326683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turbyville TJ, Gursel DB, Tuskan RG, Walrath JC, Lipschultz CA, Lockett SJ, Wiemer DF, Beutler JA, Reilly KM. Schweinfurthin A selectively inhibits proliferation and rho signaling in glioma and neurofibromatosis type 1 tumor cells in a NF1-GRD-dependent manner. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1234–1243. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-09-0834 PMID:20442305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulrich NC, Kodet JG, Mente NR, Kuder CH, Beutler JA, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Structural analogues of schweinfurthin F: probing the steric, electronic, and hydrophobic properties of the D-ring substructure. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:1676–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.063 PMID:20116262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulrich NC, Kuder CH, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Biologically active biotin derivatives of schweinfurthin F. Biorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:6716–6720. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.143 PMID:20869871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mente NR, Wiemer AJ, Neighbors JD, Beutler JA, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Total synthesis of (R,R,R)– and (S,S,S)–schweinfurthin F: differences of bioactivity in the enantiomeric series. Biorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:911–915. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.096 PMID:17236766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neighbors JD, Beutler JA, Wiemer DF. Synthesis of nonracemic 3-deoxyschweinfurthin B. J Org Chem. 2005;70:925–931. doi: 10.1021/jo048444r PMID:15675850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neighbors JD, Buller MJ, Boss KD, Wiemer DF. A concise synthesis of pawhuskin A. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1949–1952. doi: 10.1021/np800351c PMID: 18922035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuder CH, Neighbors JD, Hohl R, Wiemer DF. Synthesis and biological activity of a fluorescent schweinfurthin analogue. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.04.071 PMID:19464190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neighbors JD, Mente NR, Boss KD, Zehnder DW, Wiemer DF. Synthesis of the schweinfurthin hexahydroxanthene core through Shi epoxidation. Tetrahedron Letters. 2008;49:516–519. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.11.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neighbors JD, Salnikova MS, Beutler JA, Wiemer DF. Synthesis and structure–activity studies of schweinfurthin B analogs: evidence for the importance of a D-ring hydrogen bond donor in expression of differential cytotoxicity. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:1771–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.025 PMID:16290161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paull KD, Shoemaker RH, Hodes L, Monks A, Scudiero DA, Rubinstein L, Plowman J, Boyd MR. Display and analysis of patterns of differential activity of drugs against human-tumor cell-lines: development of mean graph and compare algorithm. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1088–1092. PMID:2738938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuder CH, Weivoda MM, Zhang Y, Zhu J, Neighbors JD, Wiemer DF, Hohl RJ. 3-deoxyschweinfurthin B lowers cholesterol levels by decreasing synthesis and increasing export in cultured cancer cell lines. Lipids. 2015:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11745-015-4083-z PMID:26494560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bietz A, Zhu HY, Xue MM, Xu CQ. Cholesterol metabolism in T cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01664 PMID:29230226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gruenbacher G, Thurnher M. Mevalonate metabolism in immuno-oncology. Front Immunol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01714 PMID:29250078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kodet JG, Beutler JA, Wiemer DF. Synthesis and structure activity relationships of schweinfurthin indoles. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:2542–2552. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.02.043 PMID:24656801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevens JW, Meyerholz DK, Neighbors JD, Morcuende JA. 5ʹ-methylschweinfurthin G reduces chondrosarcoma tumor growth. J Orthop Res. 2017. doi: 10.1002/jor.23753 PMID:28960476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kodet JG, Wiemer DF. Synthesis of indole analogues of the natural schweinfurthins. J Org Chem. 2013;78:9291–9302. doi: 10.1021/jo4014244 PMID:24004185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galluzzi L, Buque A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:97–111. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.107 PMID:27748397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:51–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100008 PMID:23157435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gardai SJ, McPhillips KA, Frasch SC, Janssen WJ, Starefeldt A, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Bratton DL, Oldenborg PA, Michalak M, Henson PM. Cell-surface calreticulin initiates clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of LRP on the phagocyte. Cell. 2005;123:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.032 PMID:16239148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, Gott B, Chen X, Chaleff S, Kotb M, Gillies SD, King M, Mangada J, et al. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:6477–6489. PMID:15879151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verma MK, Clemens J, Burzenski L, Sampson SB, Brehm MA, Greiner DL, Shultz LD. A novel hemolytic complement-sufficient NSG mouse model supports studies of complement-mediated antitumor activity in vivo. J Immunol Methods. 2017;446:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.03.021 PMID:28390927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weber JS, Postow M, Lao CD, Schadendorf D. Management of adverse events following treatment with anti-programmed death-1 agents. Oncologist. 2016;21:1230–1240. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0055 PMID:27401894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holstein SA, Kuder CH, Tong H, Hohl RJ. Pleiotropic effects of a schweinfurthin on isoprenoid homeostasis. Lipids. 2011;46:907–921. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3572-y PMID:21633866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burgett AWG, Poulsen TB, Wangkanont K, Anderson DR, Kikuchi C, Shimada K, Okubo S, Fortner KC, Mimaki Y, Kuroda M, et al. Natural products reveal cancer cell dependence on oxysterol-binding proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:639–647. doi: 10.1038/nhembio.625 PMID:21822274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bao X, Zheng W, Sugi NH, Agarwala Kl, Xu Q, Wang Z, Tendyke K, Lee W, Parent L, Wei L, et al. Small molecule schweinfurthins selectively inhibit cancer cell proliferation and mTOR/AKT signaling by interfering with trans-Golgi-network trafficking. Can Biol Ther. 2015;16:1–13. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1019184 PMID:25729885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou H, Sauvat A, Gomes-da-Silva LC, Durand S, Forveille S, Iribarren K, Yamazaki T, Souquere S, Bezu L, Muller K, et al. The oncolytic compound LTX-401 targets the Golgi apparatus. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:2031–2041. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.86 PMID:27588704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riganti C, Castella B, Kopecka J, Campia I, Coscia M, Pescarmona G, Bosia A, Ghigo D, Massaia M. Zoledronic acid restores doxorubicin chemosensitivity and immunogenic cell death in multidrug-resistant human cancer cells. Plos One. 2013;8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060975 PMID:23593363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 48.Riganti C, Massaia M. Inhibition of the mevalonate pathway to override chemoresistance and promote the immunogenic demise of cancer cells Killing two birds with one stone. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2. doi: 10.4161/onci.25770 PMID:24327936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galluzzi L, Buque A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunological effects of conventional chemotherapy and targeted anticancer agents. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:690–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.012 PMID:26678337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfirschke C, Engblom C, Rickelt S, Cortez-Retamozo V, Garris C, Pucci F, Yamazaki T, Poirier-Colame V, Newton A, Redouane Y, et al. Immunogenic chemotherapy sensitizes tumors to checkpoint blockade therapy. Immunity. 2016;44:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.024 PMID:26872698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dosset M, Vargas TR, Lagrange A, Boidot R, Vegran F, Roussey A, Chalmin F, Dondaine L, Paul C, Marie-Joseph EL, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: an adaptive immune resistance mechanism to immunogenic chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1433981. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1433981 PMID:29872568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lei A, Yang Q, Li X, Chen H, Shi M, Xiao Q, Cao Y, He Y, Zhou J. Atorvastatin promotes the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and attenuates murine colitis. Immunology. 2016;149:432–446. doi: 10.1111/imm.12662 PMID:27548304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zamanian-Daryoush M, Lindner DJ, DiDonato JA, Wagner M, Buffa J, Rayman P, Parks JS, Westerterp M, Tall AR, Hazen SL. Myeloid-specific genetic ablation of ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA1 is protective against cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:71965–71980. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18666 PMID:29069761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tavazoie MF, Pollack I, Tanqueco R, Ostendorf BN, Reis BS, Gonsalves FC, Kurth I, Andreu-Agullo C, Derbyshire ML, Posada J, et al. LXR/ApoE activation restricts innate immune suppression in cancer. Cell. 2018;172:825–40e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.026 PMID:29336888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka T, Fujita M, Hasegawa H, Arimoto A, Nishi M, Fukuoka E, Sugita Y, Matsuda T, Sumi Y, Suzuki S, et al.Frequency of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the peripheral blood reflects the status of tumor recurrence. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:3863–3869. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11766 PMID:28668887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanaka T, Fujita M, Hasegawa H, Arimoto A, Nishi M, Fukuoka E, Sugita Y, Matsuda T, Sumi Y, Suzuki S, et al. HMG-CoA reductase promotes protein prenylation and therefore is indispensible for T-cell survival. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2824. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.221 PMID:28542128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thurnher M, Gruenbacher G. T lymphocyte regulation by mevalonate metabolism. Sci Signal. 2015;8:re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005970 PMID:25829448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang W, Bai Y, Xiong Y, Zhang J, Chen S, Zheng X, Meng X, Li L, Wang J, Xu C, et al. Potentiating the antitumour response of CD8(+) T cells by modulating cholesterol metabolism. Nature. 2016;531:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature17412 PMID:26982734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma X, Bi E, Huang C, Lu Y, Xue G, Guo X, Wang A, Yang M, Qian J, Dong C, et al. Cholesterol negatively regulates IL-9-producing CD8(+) T cell differentiation and antitumor activity. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1555–1569. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171576 PMID:29743292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schell TD, Mylin LM, Georgoff I, Teresky AK, Levine AJ, Tevethia SS. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope immunodominance in the control of choroid plexus tumors in simian virus 40 large T antigen transgenic mice. J Virol. 1999;73:5981–5993. PMID:10364350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rose S, Misharin A, Perlman H. A novel Ly6C/Ly6G-based strategy to analyze the mouse splenic myeloid compartment. Cytometry A. 2012;81:343–350. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22012 PMID:22213571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.