Abstract

Background and Aims

Salt has been shown to affect Cd translocation and accumulation in plants but the associated mechanisms are unclear. This study examined the effects of salt type and concentration on Cd uptake, translocation and accumulation in Carpobrotus rossii.

Methods

Plants were grown in nutrient solution with the same Cd concentration or Cd2+ activity in the presence of 25 mm NaNO3, 12.5 mm Na2SO4 or 25 mm NaCl for ≤10 d. Plant growth and Cd uptake were measured and the accumulation of peptides and organic acids, and Cd speciation in plant tissues were analysed.

Key Results

Salt addition decreased shoot Cd accumulation by >50 % due to decreased root-to-shoot translocation, irrespective of salt type. Synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy revealed that, after 10 d, 61–94 % Cd was bound to S-containing ligands (Cd–S) in both roots and shoots, but its speciation was not affected by salt. In contrast, Cd in the xylem sap was present either as free Cd2+ or complexes with carboxyl groups (Cd–OH). When plants were exposed to Cd for ≤24 h, 70 % of the Cd in the roots was present as Cd–OH rather than Cd–S. However, NaCl addition decreased the proportion of Cd–OH in the roots within 24 h by forming Cd–Cl complexes and increasing the proportion of Cd–S. This increase in Cd–S complexes by salt was not due to changes in glutathione and phytochelatin synthesis.

Conclusions

Salt addition decreased shoot Cd accumulation by decreasing Cd root-to-shoot translocation due to the rapid formation of Cd–S complexes (low mobility) within the root, without changing the concentrations of glutathione and phytochelatins.

Keywords: Cd uptake, organic acids, phytochelatins, phytoextraction, sodium salt, synchrotron, XANES

INTRODUCTION

Cadmium (Cd) is one of the most environmentally toxic pollutants. It can accumulate in plant tissues to levels that are harmful in the diets of animals and humans without being toxic to the plant itself. This Cd enters the environment mainly through the application of a range of compounds, including sewage sludge as a soil amendment, wastes from incinerators and other industrial activities and phosphate fertilizers (Nicholson et al., 1994). Among the various approaches to remediation, phytoextraction using plants to remove Cd from contaminated soils is environmentally friendly and cost-efficient (Mahar et al., 2016).

In some areas, high levels of salinity are another important environmental stress. An estimated 20–50 % of all irrigated lands worldwide are affected by excess salt, with NaCl being the salt of greatest interest (Pitman and Läuchli, 2002). High concentrations of bioavailable Cd are associated with high levels of soluble salts in coastal or semi-arid areas because of mining or urbanization (US Environmental Protection Agency, 2000; Panta et al., 2014; Lutts and Lefèvre, 2015). In these saline soils, most glycophyte Cd-hyperaccumulating species are not suited for growth (Ghnaya et al., 2007; Lutts and Lefèvre, 2015). As a result, the influence of NaCl on Cd accumulation in plants, particularly in halophytes, is of increasing interest (Lutts and Lefèvre, 2015). It has been reported that the presence of NaCl in Cd-containing solutions improves the growth of halophytes but decreases the Cd concentration in the plant tissues (Ghnaya et al., 2007; Lefèvre et al., 2009; Chai et al., 2013; Wali et al., 2015). This decrease in tissue Cd concentration may be due to a dilution effect, with NaCl alleviating the Cd-induced growth reduction (Ghnaya et al., 2007; Wali et al., 2015). NaCl may also decrease root Cd uptake via the decreased activity of Cd2+ in solutions associated with the formation of CdCln2-n complexes (Smolders and McLaughlin, 1996). However, these previous studies are in contrast with others showing that the effect of NaCl on Cd accumulation is concentration-dependent. For example, NaCl increased the concentration of Cd in tissues of the halophyte Spartina alterniflora at 1 mm Cd but decreased the Cd concentration at 3 mm Cd (Chai et al., 2013). Furthermore, both NaCl and KCl decreased the concentration of Cd in the leaves of Atriplex halimus but NaNO3 increased it (Lefèvre et al., 2009). Thus, the apparent discrepancies between previous studies suggest that the effect of salt on Cd accumulation in plants differs not only between plant species but also between salt types.

Carpobrotus rossii, a halophytic succulent plant species, has been shown to have potential for phytoextraction of Cd in soils with high salinity (Zhang et al., 2016). Our previous study has shown that the addition of NaCl to Cd-containing solutions significantly reduced Cd accumulation in shoot tissues, particularly by decreasing Cd translocation from the root to the shoot even when the activity of Cd2+ in nutrient solution was maintained constant (Cheng et al., 2018). These observations for C. rossii differ from those reported previously for Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum nigrum and Beta vulgaris, where NaCl increased Cd concentrations in both shoots and roots (Smolders and McLaughlin, 1996; Xu et al., 2010). Regardless, the mechanism whereby NaCl reduces the translocation of Cd to the shoots in C. rossii remains unclear.

The chemical speciation of Cd plays an important role in influencing its mobility within plant tissues. To moderate Cd2+ concentrations in the symplast, free Cd2+ can be regulated by binding to phytochelatins (PCs) and glutathione (GSH), with Cd having a high affinity for thiol groups (Clemens et al., 2002; Clemens, 2006). These Cd–S complexes can be subsequently transported into vacuoles and potentially transformed to inactive forms for storage. In addition, some free Cd2+ ions in the cytosol can be anti-ported into the vacuole and then weakly bound to simple organic acids (Clemens, 2006). Our previous study (Cheng et al., 2016) showed that most of the Cd in both the roots and shoots of C. rossii was bound to thiol groups, but these Cd–S complexes were not involved in the root-to-shoot translocation. Rather, the Cd in the xylem sap was present either as free Cd2+ ions or complexed with carboxyl groups. Thus, it is possible that NaCl alters Cd speciation within the plant tissues, with high levels of NaCl known to alter the composition of plant cells and the concentration of inorganic and organic compounds in plant tissues (Munns and Tester, 2008). For example, using a sequential extraction procedure, Wali et al. (2015) found that NaCl changed the chemical form of Cd in the tissues of Sesuvium portulacastrum by increasing the proportion of Cd bound to pectates, proteins and chloride, with a concomitant increase in Cd tolerance and translocation. However, the sequential extraction can cause experimental artefacts in regard to Cd speciation. In this regard, synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) is potentially useful as it allows the in situ analysis of metal speciation in hydrated plant tissues. To the best of our knowledge, no study has provided direct (in situ) analyses of changes in Cd speciation in plants under the dual stress of Cd and salinity, which is needed to understand the detoxification and accumulation of Cd in halophytic plant species.

This study examined the effect of salt type and concentration on Cd uptake, translocation and accumulation in C. rossii. Specifically, it examined whether changes in Cd concentrations were associated with concomitant changes in Cd speciation within these tissues. We hypothesized that (1) the addition of NaNO3 and Na2SO4, like NaCl, would decrease tissue Cd concentrations; and (2) the decrease in Cd accumulation in shoots by salts would be associated with changes in the levels of physiologically relevant ligands with a concomitant change in Cd speciation within the plant tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant growth

Plants of Carpobrotus rossii were grown in a controlled glasshouse with a 14-h photoperiod at 18–25 °C and 45–65 % relative humidity in Victoria, Australia (Cheng et al., 2018). Uniform cuttings (two nodes each cutting) were cut from mother plants and washed with tap water. Then, the cuttings were transplanted to 5 L of continuously aerated solution containing the following nutrients (µm): MgSO4, 200; KH2PO4, 10; K2SO4, 600; Ca(NO3)2, 600; FeNaEDTA, 20; H3BO3, 5; MnSO4, 1; CuSO4, 0.2; Na2MoO4, 0.03; ZnSO4, 1. The plants were grown in a controlled-environment growth room with day/night temperatures of 20/18 °C and 50 % relative humidity. A 14-h photoperiod with a light intensity of 400 µmol m−2 s−1 was supplied. The solutions were maintained at pH ~6.0 with 1 m KOH and were renewed every 6 d. After rooting and acclimation for 2 weeks, rooted cuttings of similar size were weighed and transferred to new pots (four cuttings per pot) containing the treatment solutions described for Experiments 1 and 2 (Cheng et al., 2018). Four additional cuttings were washed with deionized water, oven-dried (80 °C), and weighed to determine their initial weight.

Experiment 1

This experiment aimed to examine the effect of salt type on the uptake, translocation and speciation of Cd in plants after exposure for 10 d. It consisted of four salt treatments (control, 25 mm NaNO3, 12.5 mm Na2SO4 and 25 mm NaCl) and three Cd concentrations (Supplementary Data Table S1). The three Cd levels used were (1) 0 µm (control); (2) a constant Cd concentration of 15 µm (Cd2+ activity varied from 3.2 to 10.9 µm depending upon the salt concentration); and (3) a constant Cd2+ activity of 10.9 µm (total Cd concentration varied from 15 to 50 µm depending upon the salt type) (Supplementary Data Table S1). The concentration of NaCl (25 mm) was selected because this concentration had no impact on plant growth but significantly decreased Cd accumulation in C. rossii in our previous experiment (Cheng et al., 2018). The corresponding concentrations of NaNO3 (25 mm) and Na2SO4 (12.5 mm) were chosen such that the concentration of Na remained constant. Each treatment was replicated three times and arranged randomly. The speciation of Cd in the nutrient solutions (Supplementary Data Table S1) was calculated using the GEOCHEM-EZ program with the default log K values for Cd (Supplementary Data Table S2) (Shaff et al., 2010). Following their initial growth in basal solutions, plants were grown in the treatment solutions for a further 10 d. Solution pH was buffered with 2 mm MES [2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulphonic acid] and maintained at 6.0 with 1 m KOH. The nutrient solutions had the same composition as the basal nutrient solution. The only exception was that KOH, not K2SO4, was added as K in the treatment solutions (final K concentration 1210 µm). The solutions were aerated continuously and renewed every 3 d.

After 10 d of growth of the plants in the treatment solutions, xylem sap was collected as described by Cheng et al. (2016). Then, plants were separated into leaves, stems and roots, and fresh weight was recorded. The roots were divided into three parts. The first two parts were immersed in ice-cold 20 mm Ca(NO3)2 for 15 min, washed with deionized water and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Then, the first subsample was stored at −80 °C for later analysis of Cd speciation using synchrotron-based XAS, while the second subsample was freeze-dried for analyses of peptides and organic acids. The third subsample was immersed in 20 mm Na2-EDTA for 15 min, washed with deionized water, weighed, and oven-dried (80 °C) for chemical analysis. Similarly, after washing with deionized water, shoots were divided into three parts. The relative growth rate (RGR) was calculated according to the equation

where W1 and W2 were the weights of dry matter at the beginning and end of the treatment period, and (t2 − t1) was the treatment duration (Hunt, 1990).

Experiment 2

This experiment studied the effects of NaCl on Cd uptake and translocation within 24 h. It consisted of three treatments and three replicates, with all three treatments having 10.9 µm calculated Cd2+ activity. The three treatments were (1) 15 µm Cd with no added salt; (2) 50 µm Cd with 25 mm NaCl [Cd + low salt (LS)]; and (3) 85 µm Cd with 50 mm NaCl [Cd + high salt (HS)] (Supplementary Data Table S1). The cuttings were prepared as for Experiment 1 and then grown in the same controlled-environment growth room, with samples collected after 6, 12 and 24 h of treatment. Plant sample preparation followed the same procedure as outlined for Experiment 1. The Cd concentrations in shoot tissues were too low to permit later analysis using synchrotron-based XAS.

Analyses of Cd concentration in plant tissues

Oven-dried tissue samples from Experiments 1 and 2 were digested using concentrated HNO3 in a microwave digester (Multiwave 3000, Anton Paar) after being ground. Elemental concentrations in the digestion solutions and xylem sap (0.5 mL mixed with 2.5 mL of 5 % HNO3) were determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Perkin Elmer Optima 8000, MA, USA).

Cadmium speciation by XAS

The speciation of Cd in the plant tissues was examined in situ on the XAS beamline of the Australian Synchrotron (Victoria, Australia). Details of this beamline, as used for the analysis of Cd in plant tissues, have been provided previously (Cheng et al., 2016). For Experiment 1, the spectra of the plant tissues were only collected for the various treatments where the Cd2+ activity was maintained constant [i.e. treatment (T) 9 to T11; Supplementary Data Table S1]. For Experiment 2, spectra of the root tissues were collected from all three treatments. The frozen plant tissues (1–2 g) were ground with a pestle in an agate mortar filled with liquid nitrogen. The xylem sap was collected from plants and transferred to the Australian Synchrotron immediately before analysis. Both X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra were collected using a 100-element solid-state Ge detector, with the beam size adjusted to ~2.5 mm × 0.2 mm. We had previously assessed beam damage in hydrated plant samples in this beamline, with no damage evident under the current experimental conditions using the cryostat (Cheng et al., 2016).

The XANES and EXAFS spectra were also collected from Cd-containing standard compounds. Our previous study showed that the spectra of compounds with S-containing ligands (such as Cd-GSH and Cd-PC) were difficult to separate using this approach (Cheng et al., 2016). In addition, the spectra of compounds where the Cd was complexed with various carboxyl groups (e.g. Cd-organic acids and Cd-polygalacturonate) were also similar to each other and visually indistinguishable from that of aqueous Cd(NO3)2 (Cheng et al., 2016). Thus, in the present study we only prepared four Cd-containing standard compounds. The three aqueous standards were (1) 1 mm Cd(NO3)2; (2) 1 mm Cd(NO3)2 with 5 mm GSH; and (3) 1 mm Cd(NO3)2 with 100 mm NaCl. Hereafter, the spectra for Cd complexed with GSH are referred to as ‘Cd–S’ (compounds with S-containing ligands) and those for aqueous Cd(NO3)2 are referred to as ‘Cd–OH’ (Cd either complexed with various carboxyl groups or present as the free aqueous Cd2+ ion). Standards were prepared using 10 mm stock solutions of Cd(NO3)2 together with 50 mm GSH or 1 m NaCl. Solution standards were then mixed with 30 % glycerol, and pH [other than 1 mm Cd(NO3)2] was adjusted to ~ pH 6 using 0.1 m NaOH. The results using GEOCHEM-EZ modelling indicated that 99 % of Cd was Cd2+ in the Cd(NO3)2 standard and 81.4 % with Cl− in the Cd-NaCl standard. No constant was available in GEOCHEM-EZ for GSH. A solid standard of Cd3(PO4)2 was also analysed after being diluted to 100 mg Cd kg−1 using cellulose.

For all XANES and EXAFS analyses, spectra were energy-normalized using the reference energy of the Cd foil, and duplicate spectra for each sample were merged using Athena (version 0.9.22) (Ravel and Newville, 2005). Linear combination fitting (LCF) was performed for the XANES data using Athena and the fitting energy range was –30 to +100 eV relative to the Cd K edge.

Analyses of peptides and organic acids in plant tissues

Four peptides [GSH, phytochelatin 2 (PC2), phytochelatin 3 (PC3) and phytochelatin 4 (PC4)] and three organic acids (citrate, malate and succinate) in plant materials were extracted and analysed using high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (Agilent 6460 Triple Quadrupole LC/MS) (Cheng et al., 2018).

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance was performed to examine for significance (P ≤ 0.05) of treatment differences using GenStat v. 11 (VSN International).

RESULTS

Experiment 1

Plant growth

After 10 d of treatment, all plants visually appeared to be healthy, other than plants in the solutions containing 15 μm Cd in the absence of added salt (T5), which were visibly smaller (Table 1). In solutions without Cd, neither Na2SO4 nor NaCl influenced plant biomass or RGR, but the addition of NaNO3 increased shoot biomass by 11 % (P < 0.05) compared with the control (T1). In comparison, the addition of 15 μm Cd (T5) in the absence of added salt decreased shoot biomass by 46 %, root biomass by 68 % and RGR by 57 % compared with the control. However, salt addition to these Cd-containing solutions markedly alleviated the Cd-induced growth reduction, with RGR increasing by 56–88 % (Table 1). The magnitude of this growth improvement was similar for all three salts (NaNO3, Na2SO4 and NaCl).

Table 1.

Dry weights of shoots and roots and relative plant growth rate of Carpobrotus rossii grown in different treatments for 10 d. Means with the same letter do not differ significantly (Duncan’s test, P < 0.05) (Experiment 1)

| Treatment | Dry weight (g plant−1) | Relative growth rate (mg g−1 d−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Salt | Cd (µm) | Cd2+ activity (μm) | Roots | Shoots | |

| T1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 a | 1.81 b | 94.2 ab |

| T2 | 25 mm NaNO3 | 0 | 0 | 0.26 a | 2.07 a | 105.1 a |

| T3 | 12.5 mm Na2SO4 | 0 | 0 | 0.24 a | 1.75 b | 98.0 ab |

| T4 | 25 mm NaCl | 0 | 0 | 0.24 a | 1.90 ab | 87.3 b |

| T5 | 0 | 15 | 10.9 | 0.08 d | 0.97 d | 39.8 e |

| T6 | 25 mm NaNO3 | 15 | 7.4 | 0.14 cd | 1.26 c | 74.9 c |

| T7 | 12.5 mm Na2SO4 | 15 | 3.9 | 0.22 ab | 1.04 cd | 73.3 c |

| T8 | 25 mm NaCl | 15 | 3.2 | 0.17 bc | 1.09 cd | 74.4 c |

| T9 | 25 mm NaNO3 | 22 | 10.9 | 0.10 cd | 1.12 cd | 67.7 cd |

| T10 | 12.5 mm Na2SO4 | 42 | 10.9 | 0.11 cd | 1.02 cd | 62.1 d |

| T11 | 25 mm NaCl | 50 | 10.9 | 0.13 cd | 1.10 cd | 67.3 cd |

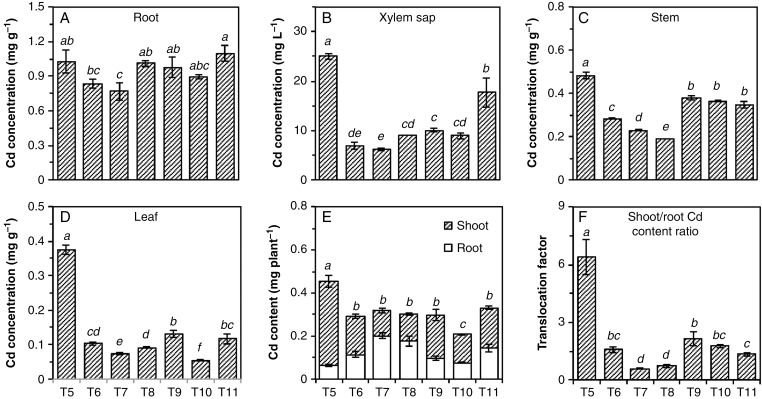

Cadmium concentration and content in plants.

The concentrations of Cd in tissues of plants growing without added Cd (T1–T4) were under the detection limit (<0.03 μg g−1) and are not shown. For the remaining treatments, concentrations of Cd were highest in the root (0.79–1.1 mg g−1), followed by the stem (0.19–0.50 mg g−1), leaf (0.06–0.38 mg g−1) and xylem sap (6–25 mg L−1) (Fig. 1A–D).

Fig. 1.

Concentrations of Cd in roots (A), xylem sap (B), stems (C) and leaves (D), total Cd content (E) and Cd translocation factor (F) of Carpobrotus rossii grown in different treatments for 10 d. T5, 15 μm Cd; T6, 15 μm Cd + 25 mm NaNO3; T7, 15 μm Cd + 12.5 mm Na2SO4; T8, 15 μm Cd + 25 mm NaCl; T9, 22 μm Cd + 25 mm NaNO3; T10, 42 μm Cd + 12.5 mm Na2SO4; T11, 50 μm Cd + 25 mm NaCl. Error bars represent ± s.e.m. of three replicates. Means with a common letter did not differ significantly (Duncan’s test, P < 0.05) (Experiment 1).

The addition of salt did not impact upon the concentration of Cd in the root tissues, with concentrations in all salt-containing treatments (T6–T11) being similar to that in the salt-free treatment (T5) (Fig. 1A). The only exception was the Na2SO4 treatment at 15 μm Cd (T7), where the root Cd concentration was 25 % lower than in the salt-free treatment. Despite the concentration in the roots being similar irrespective of treatment, the addition of salts decreased the concentration of Cd in xylem sap by 65–75 % at 15 µm Cd (T6–T8, Fig. 1B). Accordingly, tissue Cd concentrations in these treatments (T6–T8) were 40–60 % lower in stems and 70–80 % lower in leaves compared with the salt-free treatment (T5) (Fig. 1C, D). Next, we compared treatments where the calculated Cd2+ activity was maintained constant in order to determine whether the decrease in shoot Cd concentrations could be attributed simply to an increase in ionic strength and a concomitant decrease in Cd2+ activity. However, similar trends were also observed when plants were grown in treatments with the same Cd2+ activity (T9–T11), although the extent of the salt effect was smaller. Specifically, the addition of NaNO3, Na2SO4 and NaCl decreased the Cd concentration in the xylem sap by 60, 64 and 30 % and in the leaf tissues by 65, 85 and 69 %, respectively, compared with the salt-free treatment (T5).

The addition of NaNO3, Na2SO4 or NaCl with 15 μm Cd (T6–T8) decreased Cd accumulation in shoots by 55, 70 and 68 % compared with solutions with Cd alone (T5) (Fig. 1E). Similarly, when plants were grown in solutions at a constant Cd2+ activity (T9–T11), the addition of NaNO3, Na2SO4 and NaCl decreased shoot Cd accumulation by 48, 66 and 52 %, respectively. In contrast, salt addition actually increased Cd accumulation in the roots. Accordingly, all three salts significantly decreased the Cd translocation factor (the ratio of Cd content in the shoots and the roots) by 66–91 %, the magnitude of this decrease being greater for Na2SO4 and NaCl than for NaNO3 (Fig. 1F). This marked decrease in the translocation factor was observed regardless of whether Cd was maintained at the same concentration (T6–T8) or the same calculated Cd2+ activity (T9–T11).

Cadmium speciation in plant tissues using XAS.

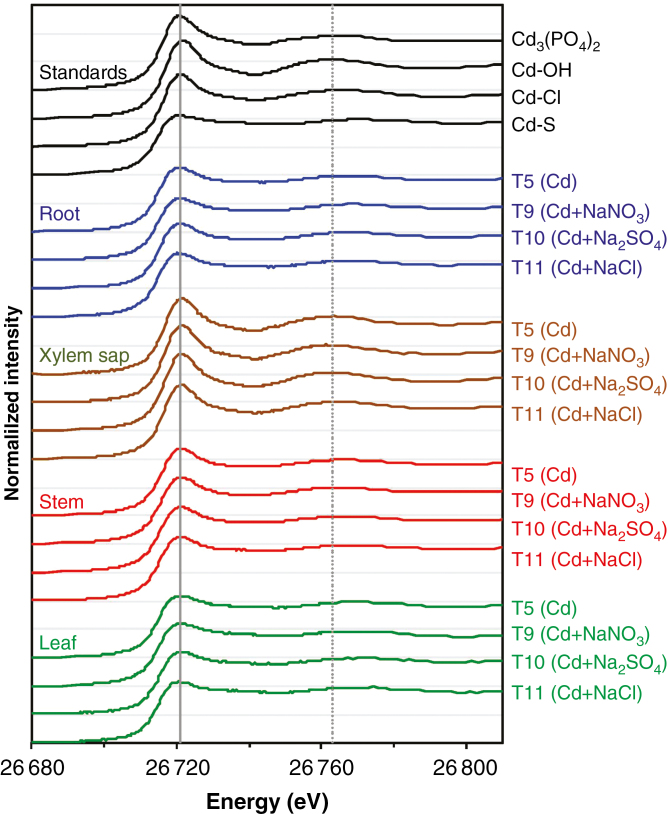

We examined the XANES spectra for the standard compounds. Clear differences could be seen between the spectra of Cd3(PO4)2, Cd–OH, Cd–Cl and Cd–S, especially for Cd–S. Specifically, the various standard compounds could be identified based on (1) slight shifts in the energy corresponding to the white line peak, being 26 720.8 eV for Cd–S, 26 720.9 eV for Cd3(PO4)2, 26 721.1 eV for Cd–Cl and 26 721.5 eV for Cd–OH; (2) differences in the magnitude of this white-line peak; and (3) shifts in a spectral feature being at 26 762 eV for Cd–OH, 26 765 eV for Cd3(PO4)2, 26 768 eV for Cd–Cl and 26 769 eV for Cd–S (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Normalized Cd-edge XANES spectra of the Cd standards and various tissues of Carpobrotus rossii grown for 10 d in solutions with the same Cd2+ activity (10.9 µm). T5, 15 μm Cd; T9, 22 μm Cd + 25 mm NaNO3; T10, 42 μm Cd + 12.5 mm Na2SO4; T11, 50 μm Cd + 25 mm NaCl. The horizontal grey lines represent a value of 1 for each of the normalized spectra, while the vertical grey lines represent the white-line peak at 26 721.5 eV (solid line) and the spectral feature at 26 762 eV (dotted line) for the Cd–OH standard (Experiment 1).

We then compared the XANES spectra of the root and shoot tissues, and examined whether salt type affected Cd speciation in these tissues. As expected (Cheng et al., 2016), the spectra for both root and shoot tissues were comparatively featureless (flat) and visually similar to that of Cd–S, with the spectral feature being at 26 769 eV (corresponding to Cd–S) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data Fig. S1a). Furthermore, these spectra were visually similar irrespective of salt type, indicating that salt type did not alter Cd speciation within these tissues. Indeed, LCF predicted that the majority (62–94 %) of Cd in the roots, stems and leaves was associated with S-containing ligands, the proportion of Cd–S being higher in leaf tissues (83–94 %) than in roots (70–84 %) and in stems (62–79 %) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predicted speciation of Cd in various tissues of Carpobrotus rossii grown for 10 d in solutions with the same Cd2+ activity (10.9 µm), as calculated using linear combination fitting of the K-edge XANES spectra (Experiment 1)

| Treatment | R factor | Cd–OH (%) | Cd–S (%) | Cd–Cl (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Salt | Cd (µm) | ||||

| Root | ||||||

| T5 | 0 | 15 | 0.001316 | 23.2 (0.9) | 76.8 (2.7) | – |

| T9 | 25 mm NaNO3 | 22 | 0.001027 | 15.7 (0.8) | 84.3 (2.5) | – |

| T10 | 12.5 mm Na2SO4 | 42 | 0.000943 | 29.8 (0.8) | 70.2 (2.6) | – |

| T11 | 25 mm NaCl | 50 | 0.001235 | 19.2 (0.9) | 80.8 (2.8) | – |

| Xylem sap | ||||||

| T5 | 0 | 15 | 0.000357 | 89.3 (1.1) | 10.7 (1.8) | – |

| T9 | 25 mm NaNO3 | 22 | 0.000816 | 93.6 (3.3) | 6.4 (0.8) | – |

| T10 | 12.5 mm Na2SO4 | 42 | 0.000335 | 91.9 (5.2) | 8.1 (0.5) | – |

| T11 | 25 mm NaCl | 50 | 0.000101 | 24.9 (3.4) | – | 75.1 (0.7) |

| Stem | ||||||

| T5 | 0 | 15 | 0.000418 | 38.1 (0.5) | 61.9 (1.4) | – |

| T9 | 25 mm NaNO3 | 22 | 0.000585 | 38.8 (3.3) | 61.2 (0.6) | – |

| T10 | 12.5 mm Na2SO4 | 42 | 0.000369 | 30.2 (0.5) | 69.8 (2.1) | – |

| T11 | 25 mm NaCl | 50 | 0.000490 | 21.4 (0.6) | 78.6 (2.0) | – |

| Leaf | ||||||

| T5 | 0 | 15 | 0.000384 | 11.7 (0.5) | 88.3 (2.1) | – |

| T9 | 25 mm NaNO3 | 22 | 0.000927 | 11.8 (1.2) | 88.2 (0.8) | – |

| T10 | 12.5 mm Na2SO4 | 42 | 0.001401 | 17.3 (1.4) | 82.7 (1.0) | – |

| T11 | 25 mm NaCl | 50 | 0.000748 | 5.7 (0.7) | 94.3 (1.0) | – |

Values in parentheses show percentage variation in calculated values.

Goodness of fit is indicated by the R factor [= Σi (experiment – fit)2⁄Σi (experimental)2] where the sums are over the data points in the fitting region.

In comparison, the spectra of the xylem sap clearly differed, being similar to that of Cd–OH with a spectral feature at 26 763 eV (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data Fig. S1b). The only exception to this was the xylem sap for the NaCl treatment (T11), where the white-line peak was at 26 721 eV and the spectral feature was at 26 766 eV (corresponding to Cd–Cl) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data Fig. S2). This difference was also observed for the EXAFS spectra, with the spectrum of the xylem sap from the NaCl-treated plants (T11) being similar to that of the Cd–Cl standard (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). Furthermore, LCF subsequently predicted that Cd–OH was the dominant form (89–94 %) in the xylem sap of all treatments except for plants grown in solutions with NaCl, where the majority of Cd was present as Cd–Cl (Table 2).

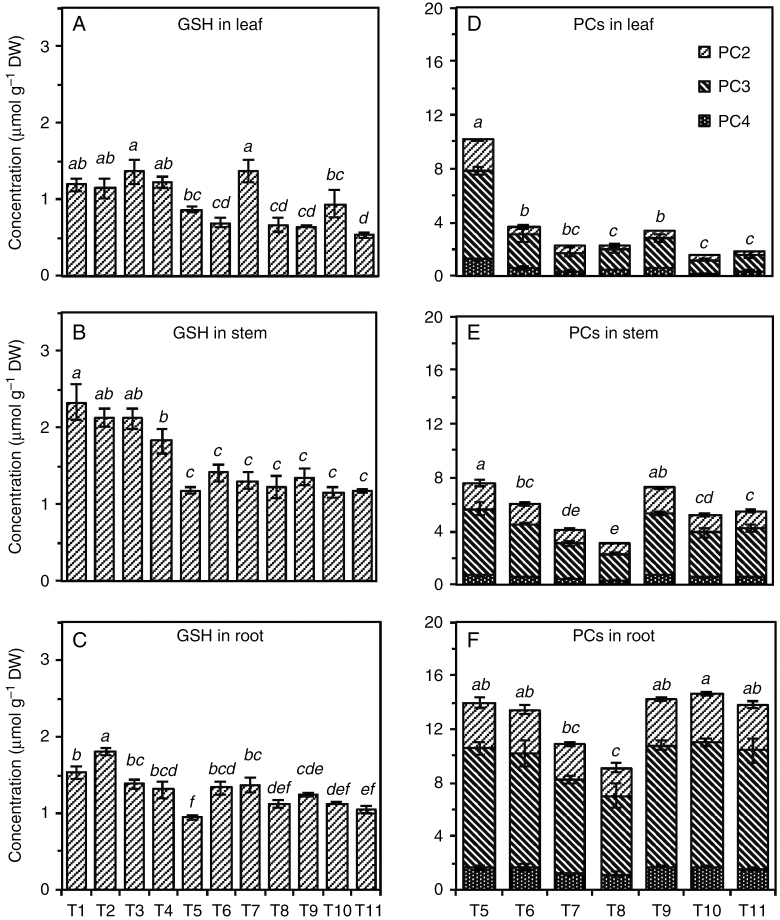

Concentrations of GSH, PCs and organic acids in plant tissues

Compared with the control (T1), the addition of salts in the absence of Cd did not affect the concentration of GSH in plant tissues (Fig. 3A–C). However, the addition of Cd in the absence of salt decreased GSH concentrations in stems and roots by 49 % (P < 0.05) and tended to decrease GSH in the leaf (P = 0.08). The addition of salts to Cd-containing solutions had little effect on the GSH concentrations in the tissues, except for the Na2SO4 treatment at 15 μm Cd (T7), compared with the treatment with Cd alone (T5).

Fig. 3.

Concentrations of GSH (A–C) and PCs (D–F) in leaves (A, D), stems (B, E), and roots (C, F) of Carpobrotus rossii grown in different treatments for 10 d. T1, control; T2, 25 mm NaNO3; T3, 12.5 mm Na2SO4; T4, 25 mm NaCl; T5, 15 μm Cd; T6, 15 μm Cd + 25 mm NaNO3; T7, 15 μm Cd + 12.5 mm Na2SO4; T8, 15 μm Cd + 25 mm NaCl; T9, 22 μm Cd + 25 mm NaNO3; T10, 42 μm Cd + 12.5 mm Na2SO4; T11, 50 μm Cd + 25 mm NaCl. Error bars represent ± s.e.m. of three replicates. Means with the same letter did not differ significantly (Duncan’s test, P < 0.05) (Experiment 1). DW, dry weight.

The concentrations of PCs in the plants grown without Cd were below the detection limit (<0.18, 0.13 and 0.10 nmol g−1 dry weight for PC2, PC3 and PC4, respectively) and are therefore not presented. For the remaining treatments (T5–T11), PC3 was the dominant PC in all tissues, and the three PCs showed a similar pattern in response to salt and Cd additions (Fig. 3D–F). Compared with the treatment with Cd alone (T5), the addition of salt significantly decreased the concentration of PCs in aerial tissues, especially in the leaf (T6–T11), but did not affect the concentrations of PCs in roots except for the 25 mm NaCl and 15 μm Cd treatment (T8), irrespective of salt type and solution Cd2+ activity.

Overall, in the absence of Cd, Na2SO4-treated plants had higher concentrations of organic acids compared with the control (T1), but NaCl-treated plants had lower concentrations (Supplementary Data Fig. S5). Exposure to Cd decreased the concentrations of organic acids in aerial tissues, especially in stems, but had little effect on the concentration in roots. Compared with the Cd-alone treatment (T5), salt addition to Cd-containing solutions significantly increased the levels of organic acids in shoots, with the strongest effect observed for Na2SO4. In contrast, the concentration of organic acids in roots was increased by the addition of NaNO3 and Na2SO4 but not NaCl.

Experiment 2

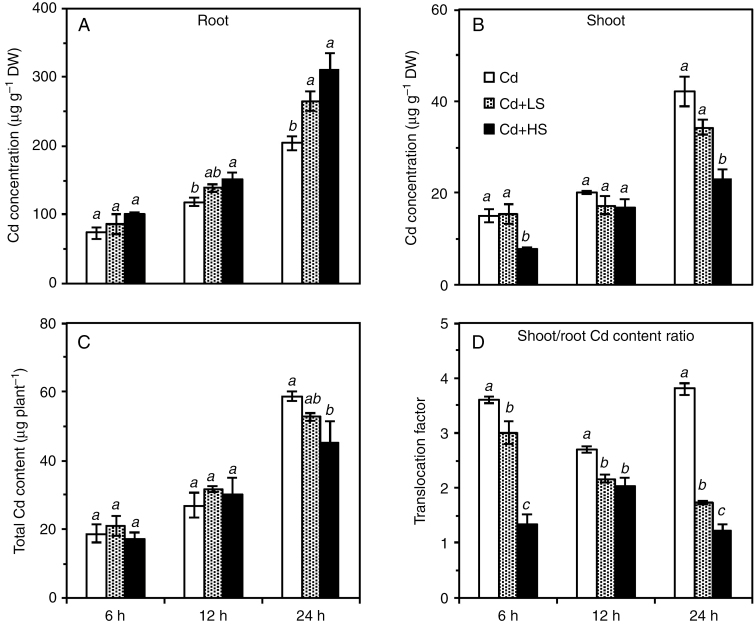

Cadmium concentration and content in plants.

At the same calculated Cd2+ activity in solution (10.9 µm), the addition of 25 mm NaCl increased root tissue Cd concentrations by 23 % after 24 h of exposure, while the addition of 50 mm NaCl increased root tissue Cd concentrations by 27 % after 12 h of exposure and by 52 % after 24 h (Fig. 4A). However, the opposite trend was observed regarding the concentration of Cd in the shoots; the addition of 25 mm NaCl decreased the concentration of Cd in shoot tissues by 19 % after 24 h of exposure (P > 0.05). Moreover, the addition of 50 mm NaCl significantly decreased the shoot Cd concentration by 47 % after 6 h of exposure and by 45 % after 24 h of exposure (Fig. 4B). However, the addition of NaCl had little impact on Cd accumulation in whole plants, with the exception of the 50 mm NaCl treatment, where Cd accumulation was 23 % lower after 24 h of exposure (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Concentrations of Cd in roots (A) and shoots (B), total Cd content (C), and translocation factor (D) of Carpobrotus rossii grown in solutions with the same Cd2+ activity (10.9 µm) for 6, 12 and 24 h. Cd, 15 μm Cd; Cd + LS (low salt), 50 μm Cd + 25 mm NaCl; Cd + HS (high salt), 85 μm Cd + 50 mm NaCl. Error bars represent ± s.e.m. of three replicates. Means with the same letter did not differ significantly at each harvest time (Duncan’s test, P < 0.05) (Experiment 2). DW, dry weight.

As observed for Experiment 1, the addition of NaCl to solutions with constant Cd2+ activity significantly decreased the Cd translocation factor by 17–63, 20–25 and 54–148 % after exposure for 6, 12 and 24 h, respectively, 50 mm NaCl having a greater effect than 25 mm NaCl (Fig. 4D).

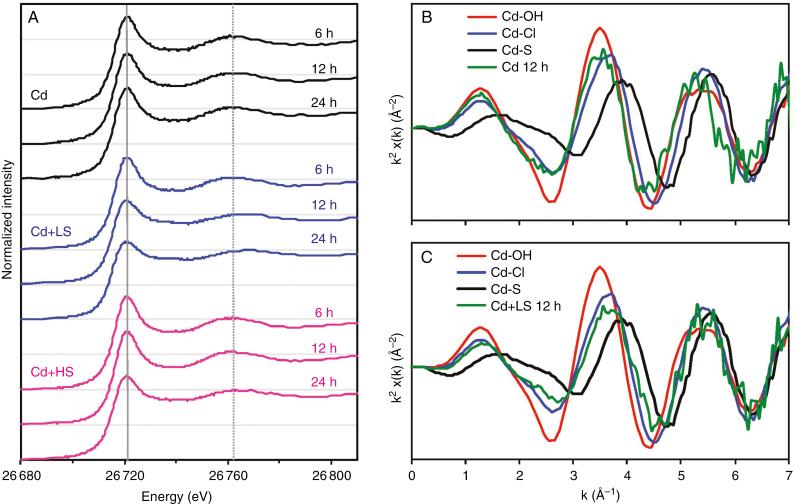

Cadmium speciation in plant tissues using XAS.

The XANES spectra of the root tissues grown in solutions containing Cd alone were similar for all three periods (6, 12 and 24 h), but differed substantially from the spectra of roots exposed to Cd for 10 d (Figs 2 and 5A). Indeed, the spectra of those roots exposed to Cd for ≤24 h were visually similar to that of the Cd–OH standard, with the spectral feature being at ca. 26 763 eV.

Fig. 5.

Normalized Cd-edge XANES spectra of the roots of Carpobrotus rossii grown in solutions with the same Cd2+ activity (10.9 µm) for 6, 12 and 24 h (A), and k2-weighted EXAFS spectra of standards plus roots of plants exposed to Cd (b) and Cd + LS (B) after 12 h. Cd, 15 μm Cd; Cd + LS (low salt), 50 μm Cd + 25 mm NaCl; Cd + HS (high salt), 85 μm Cd + 50 mm NaCl. The horizontal grey lines represent a value of 1 for each of the normalized spectra, while the vertical grey lines represent white-line peak at 26 721.5 eV (solid line) and the spectral feature at 26 762 eV (dotted line) for Cd–OH standard (Experiment 2).

The effect of NaCl addition on Cd speciation in roots was then examined within 24 h. After 6 h, the spectra for the roots were visually similar regardless of NaCl treatment, being similar to the Cd–OH standard (Fig. 5A, Supplementary data Fig. S4a). However, these spectra for the root tissues grown in NaCl-containing solutions appeared to differ over time, with increasing exposure time (≤24 h) decreasing the magnitude of the white-peak line together with a shift in the feature from ~26 760 to 26 770 eV (Fig. 5A). After 12 h, the magnitude of the white-peak line was lower in the roots of plants treated with 25 mm NaCl than in other plants, with a shift in the feature from ~26 763 eV (corresponding to Cd–OH) to 26 768 eV (corresponding to Cd–Cl) (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Data Fig. S4b). In a similar manner, after 24 h the addition of NaCl changed the spectra of the root tissues at both 25 and 50 mm (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Data Fig. S4c). For the spectra of NaCl-treated roots, the magnitude of the white-peak line was lower together with a shift in the feature from ~26 760 to 26 770 eV. Thus, it appeared that the addition of NaCl for 12 or 24 h resulted in a shift in speciation from Cd–OH to Cd–Cl. This was also in accordance with the EXAFS spectra, with an apparent shift from the peak at k = 3.5 Å−1 to 3.7 Å−1 following the addition of 25 mm NaCl for 12 h (Fig. 5B, C).

We also used LCF to predict the speciation of the Cd in the roots, with 70 % of Cd present as Cd–OH in the roots of plants grown in the absence of added salt for ≤24 h. In contrast, upon the addition of 25 mm NaCl the proportion of Cd–OH decreased due to the increased formation of Cd–S. Indeed, the amount of Cd predicted to be present as Cd–S increased from 28 % after 6 h to 61 % after 24 h (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predicted speciation of Cd in the roots of Carpobrotus rossii grown for ≤24 h in solutions with the same Cd2+ activity (10.9 µm), as calculated using linear combination fitting of the K-edge XANES spectra (Experiment 2)

| Treatment | R factor | Cd–OH (%) | Cd–S (%) | Cd–Cl (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | NaCl (mm) | Cd (µm) | ||||

| Cd | ||||||

| 6 h | 0 | 15 | 0.002689 | 71.7 (6.2) | 28.3 (1.4) | – |

| 12 h | 0 | 15 | 0.001856 | 69.5 (6.6) | 30.5 (1.2) | – |

| 24 h | 0 | 15 | 0.002303 | 70.1 (1.3) | 29.9 (2.0) | – |

| Cd + LS | ||||||

| 6 h | 25 | 50 | 0.002436 | 72.2 (1.3) | 27.8 (4.0) | – |

| 12 h | 25 | 50 | 0.000526 | – | 36.4 (3.5) | 63.6 (0.9) |

| 24 h | 25 | 50 | 0.004027 | – | 61.4 (2.5) | 38.6 (9.8) |

| Cd + HS | ||||||

| 6 h | 50 | 85 | 0.003031 | 78.0 (1.5) | 22.0 (4.5) | – |

| 12 h | 50 | 85 | 0.002435 | 82.8 (1.3) | 17.2 (2.3) | – |

| 24 h | 50 | 85 | 0.001513 | – | 35.2 (5.5) | 64.8 (1.6) |

Values in parentheses represent the percentage variation in calculated values.

Goodness of fit is indicated by the R factor [= Σi (experiment – fit)2⁄Σi (experimental)2], where the sums are over the data points in the fitting region.

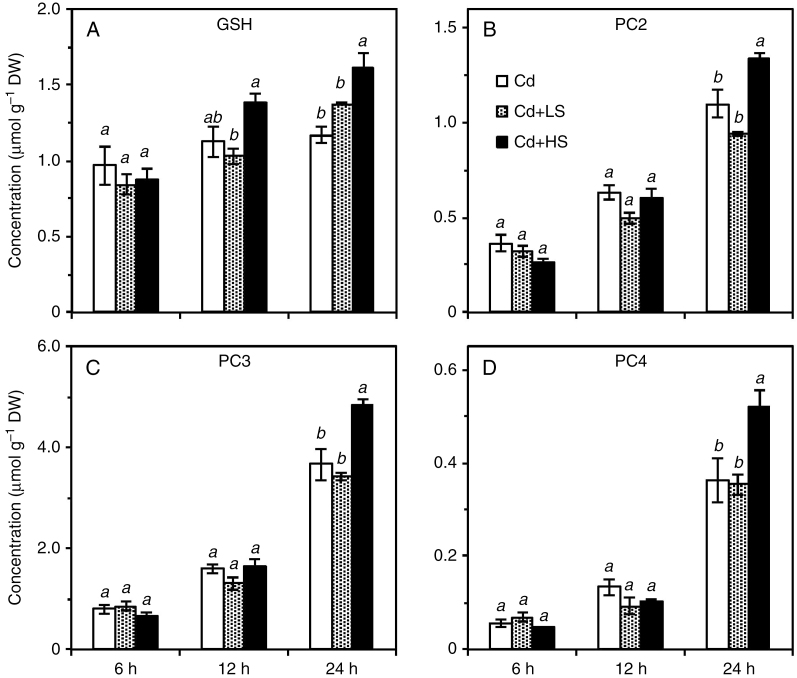

Concentrations of GSH, PCs and organic acids in plant tissues.

The GSH concentrations in the roots of NaCl-treated plants increased by 70 % within 24 h of exposure, while the concentration in the roots exposed to the Cd-alone treatment did not change significantly (Fig. 6A). In contrast, increasing the exposure time, especially after 12 h, increased the concentrations of PCs in roots, the magnitude of increase being similar for all roots (Fig. 6B, D). Moreover, the addition of NaCl did not affect the concentration of GSH or PCs in roots at any exposure time. The only exception was that, after 24 h of exposure to Cd, 50 mm NaCl increased the concentrations of GSH, PC2, PC3 and PC4 in the roots by 28, 32, 37 and 45 %, respectively. In comparison, the concentration of organic acids in root tissues decreased slightly with exposure time, especially after 24 h of exposure (Supplementary Data Fig. S6). Unlike the effect on peptides, NaCl addition did not affect the concentration of organic acids in root tissues within 12 h, but decreased the concentration by 15–35 % after 24 h of exposure.

Fig. 6.

Concentrations of GSH (A), PC2 (B), PC3 (C) and PC4 (D) in roots of Carpobrotus rossii grown in solutions with the same Cd2+ activity (10.9 µm) for 6, 12 and 24 h. Cd, 15 μm Cd; Cd + LS (low salt), 50 μm Cd + 25 mm NaCl; Cd + HS (high salt), 85 μm Cd + 50 mm NaCl. Error bars represent ± s.e.m. of three replicates. Means with the same letter did not differ significantly at each harvest time (Duncan’s test, P < 0.05) (Experiment 2). DW, dry weight.

DISCUSSION

Salinity decreased Cd accumulation in plant shoots

In all Cd-containing solutions, the addition of any of the three salts (NaCl, Na2SO4 and NaNO3) improved plant growth and decreased shoot Cd concentration after 10 d of growth, irrespective of whether the Cd concentration or the Cd2+ activity was maintained constant (Table 1; Fig. 1). However, this decreased Cd concentration in shoots of C. rossii was not caused by a dilution effect. Rather, the amount of Cd accumulated in both the shoot and the whole plant was significantly lower in salt-treated plants (Fig. 1), this being consistent with our previous observation in this same plant species for NaCl. However, this differs from previous observations in the halophyte A. halimus, in which NaCl decreased but NaNO3 increased leaf-tissue Cd concentrations (Lefèvre et al., 2009). Although these authors did not discuss possible reasons for this increase in Cd concentration upon exposure to NaNO3, it is clear that the addition of NaNO3 (but not NaCl or KCl) greatly decreased shoot dry weight and water content (Lefèvre et al., 2009). Thus, the increased Cd concentration in leaf tissues of A. halimus caused by NaNO3 (Lefèvre et al., 2009) might be related to toxicity under dual stresses of NaNO3 and Cd. In comparison, in our present study all three salts similarly alleviated the deleterious effect of Cd on plant growth. It is unclear whether the decreased Cd accumulation in C. rossii by salts was the consequence of decreased Cd uptake by roots and/or Cd translocation from roots to shoots.

Interestingly, salt addition did not alter the Cd content of the whole plant but decreased the translocation factor markedly after 6 or 12 h (Fig. 4), confirming that salt addition reduced Cd translocation from root to shoot comparatively rapidly without influencing Cd uptake. Similar observations that NaCl decreased Cd root-to-shoot translocation in Nicotiana tabacum and the halophyte Kosteletzkya virginica have also been reported (Han et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013), although NaCl was proposed to enhance Cd translocation in plants through the formation of CdCl+, which is of increased mobility within plants (Clarke et al., 2002; Ozkutlu et al., 2007; Wali et al., 2015).

Salinity decreased translocation of Cd

To understand whether this salt-induced decrease in Cd root-to-shoot translocation was due to a change in Cd speciation within the plant, we examined the effect of salts on Cd speciation using synchrotron-based XAS and the concentrations of physiologically relevant ligands. Most of the Cd was associated with S-containing ligands in both roots and shoots after 10 d of exposure to Cd, which is consistent with previous findings (Cheng et al., 2016). Determination of the peptides showed that thiols from PCs, particularly PC3, contributed up to 98 % of total thiol groups (sum of GSH and PCs) in these tissues, confirming the important role of PCs in Cd accumulation and complexation. However, the addition of Na salts did not alter Cd speciation in either the shoots or the roots when examined after 10 d of exposure (Fig. 2; Table 2), although the salts greatly decreased the concentrations of PCs but increased organic acids in plants (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data Fig. S5). In our study, the molar ratio of PC-SH to Cd was >4 in all roots and shoots irrespective of salt addition, which greatly exceeds the expected values of 2–4 for the Cd–PC complexes (Salt et al., 1997; Rauser, 1999; Vázquez et al., 2006). Furthermore, the molar ratio of COOH to Cd was greater than 7:1, indicating that all the relevant ligands were oversaturated in the tissues of C. rossii and not all of them were bound to Cd in vivo (Salt et al., 1995, 1997).

The finding that Cd translocated as Cd–OH in xylem sap was consistent with a previous study (Cheng et al., 2016). However, an interesting exception was that the Cd in the xylem sap of NaCl-treated plants was present as Cd–Cl rather than as Cd–OH, as observed for the other treatments (Supplementary Data Fig. S2; Table 2). Presumably, this formation of Cd–Cl in the xylem sap of NaCl-treated plants is due to the elevated concentration of Cl in these plants. Regardless, it seemed that Cd speciation within the plant tissues after 10 d of exposure could not explain the earlier observations that salts altered the tissue concentrations of Cd.

We then considered tissue Cd speciation in plants grown in solutions for ≤24 h. Interestingly, in the roots of these plants grown with Cd alone, Cd speciation changed depending on the duration of Cd exposure. For plants exposed to Cd for only 24 h (Experiment 2), most of the Cd in the root was as Cd–OH rather than Cd–S, whilst most of the Cd in plants was associated with S-containing ligands after 10 d of exposure (Experiment 1). Similar observations were reported previously for 5-d-old seedlings of Brassica juncea, with 65 % of Cd associated with O after 6 h of exposure but with 60 % associated with S after exposure to Cd for 48 h (Salt et al., 1997). These findings suggest that O-containing ligands (such as the pectin of the cell wall or simple organic acids) play an important role in the detoxification of Cd during the initial stages when the production of PCs is limited or when levels of exposure to Cd are lower (Wagner, 1993). However, similar to B. juncea, with increasing exposure time and with increased Cd accumulation the chelation of Cd with S-containing compounds becomes the dominant detoxification mechanism in C. rossii.

Unlike the effect of salt on roots exposed to Cd for 10 d, NaCl addition altered Cd speciation in the roots of plants receiving these shorter-term treatments (≤24 h). It was evident that increasing the exposure time from 6 to 24 h increased the proportion of Cd–S in the roots from 27.8 to 61.4 % at 25 mm NaCl and from 22.0 to 35.2 % at 50 mm NaCl, with the proportion being constant during the period in the roots exposed to Cd alone (Fig. 5A; Table 3). It is not clear why the conversion from Cd–OH to Cd–S was slower in solutions containing 50 mm NaCl. However, it is possible that the proportion of Cd associated with the cell wall was higher in the roots at 50 mm than at 25 mm NaCl. Meychik et al. (2005) observed that the concentrations of polygalacturonic acid groups in cell walls was higher for plants of the halophyte Suaeda altissima grown at 250 mm NaCl than those grown at 0.3 mm NaCl. Similarly, Mariem et al. (2014) found that the halophyte Sesuvium portulacastrum grown at 200 mm NaCl contained proportionally more Cd bound to the cell walls than plants grown at 0.09 mm NaCl. However, in our study it was not possible to distinguish between the free Cd2+ ion, Cd associated with the cell wall and Cd complexed with organic acids.

It was hypothesized that the increasing formation of Cd–S in plant roots over 24 h was due to increased synthesis of PCs, since salinity may increase antioxidant defence, particularly for halophytes, and thus increase GSH concentration within a short time (Xu et al., 2010; Lutts and Lefèvre, 2015). However, NaCl addition did not increase the concentration of GSH or PCs in roots (except for 50 mm after 24 h), although the magnitude of the increase in GSH concentration with time in the NaCl-treated roots was greater (Fig. 6). This differs from the observation that salt increased the concentrations of both GSH and PCs in A. thaliana (Xu et al., 2010). The lack of NaCl effects on the concentrations of PCs might be due to the high efficiency of PC synthesis in C. rossii exposed to Cd for a short time. It was evident that the concentration of thiols from PCs in the roots was 3-fold higher than the concentration of GSH after 6 h and increased 12-fold after 24 h, regardless of NaCl treatment, suggesting that GSH was not the limiting factor for the synthesis of PCs in plant tissues. Considering the tissue Cd concentrations, the molar ratio of PC-SH to Cd was smaller in the roots of NaCl-treated plants (T3–T7) than in those of plants treated with Cd alone (T5–T8) after 24 h of exposure. This could not explain the higher proportion of Cd–S complexes in the roots of NaCl-treated plants. Therefore, the present results imply that the increased Cd–S complexes by salt in C. rossii did not result from an increased accumulation of GSH or PCs.

It is unknown why NaCl addition increased the proportion of Cd–S in the roots after 24 h, which requires further study. One possibility is that the Na+ in plant roots receiving NaCl might compete for the cation/H+ antiporter with Cd2+ to move across the tonoplast and/or change the electrochemical potential difference for H+, which energizes the pumping of Cd2+ and Na+ into the vacuole (Jones and Gorham, 2002; Flowers and Colmer, 2008; Munns and Tester, 2008). To maintain the low level of Cd2+ in the cytoplast, more Cd2+ shifted to bind with S-containing groups in the cytoplast, and was then transported to the vacuole and stored as inactive Cd complexes with high-molecular-weight compounds (Clemens et al., 2002; Clemens, 2006).

Given that the complexes of Cd–S are not transported from roots to shoots via the xylem (Table 2), the decreased Cd root-to-shoot translocation and shoot accumulation in NaCl-treated plants could be attributed to the increased Cd retention in roots in the form of Cd–S within 24 h after Cd treatment. In addition, the decreased Cd translocation by salt could also be partly attributed to other causes, such as the distribution of Cd inside root cells (Clemens, 2006; Mariem et al., 2014), expression of the Cd transporter AtHMA4, which mediated the xylem loading of Cd and/or activity of the Cd2+/2H+ antiporters that transported the free Cd2+ ions into the vacuole (Clemens, 2006; Xu et al., 2010), or changes in leaf transpiration (Liu et al., 2010), but these hypotheses require to be further tested.

Cd–Cl complexes formed within plant tissues

In the roots of plants treated with NaCl for ≤24 h, up to two-thirds of the Cd was present as Cd–Cl (Fig. 5, Supplementary Data Fig. S4; Table 3). To our knowledge, this study provides the first direct evidence for the presence of Cd–Cl complexes within plant tissues. Other studies have shown that the formation of Cd–Cl complexes within the bulk nutrient solution increases the concentrations of Cd in plant tissues when the Cd2+ activity was maintained in bulk solutions (Smolders and McLaughlin, 1996; Xu et al., 2010). Regardless, from the results of our present study it remains unknown whether these Cd–Cl complexes were taken up by the plant from the bulk nutrient solution or whether they formed in planta. We contend that the Cd–Cl complexes were more likely formed in planta rather than being taken up directly by roots. Firstly, if the roots had taken up Cd–Cl complexes directly, NaCl-treated plants would be expected to have higher Cd accumulation since the solutions had the same Cd2+ activity (10.9 µm) but at least 3-fold higher total Cd concentration (15 µm compared with 50 and 85 µm; Table 1) (Smolders and McLaughlin, 1996). Secondly, high proportions of Cd–Cl complexes were only found in root tissues after 12 h of exposure, the majority of the root Cd being present as Cd–OH after 6 h of exposure. Thus, the substantial shift in Cd speciation from Cd–OH (6 h) to Cd–Cl (12 and 24 h) in NaCl-treated plants was more likely to be the consequence of the subsequent accumulation of Cl within the plant tissues (particularly the vacuoles) rather than the direct uptake of Cd–Cl complexes.

Regardless, the question remains, why did Cd–Cl complexes form in the shorter term but Cd–S complexes form in the longer term? We propose that, for plants exposed to Cd for ≤24 h, the comparatively rapid accumulation of Cl within the plant tissues results in the formation of Cd–Cl complexes. However, in the longer term (10 d), Cd–S complexes form due to their higher stability constants. Indeed, Cd has similar stability constants for malate (1.3–2.4), succinate (1.0–2.8) and Cl (1.3–2.8), but higher stability constants for citrate (1.0–4.5) and thiol groups (7.0–12) (Martell and Smith, 1974).

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide direct analyses of Cd speciation and relevant ligands in plants under the dual stress of Cd and salinity. We found that salt addition decreased Cd translocation in C. rossii by forming Cd–Cl complexes and increasing the proportion of Cd–S in root tissues within 24 h. However, the increased Cd–S complexes were not due to the increased synthesis of GSH or PCs in plant tissues. Further work should focus on the mechanisms of the increased Cd–S complexes in salt-treated plants, which could provide important information for improving phytoremediation efficiency and decreasing Cd intake by food crops in Cd-contaminated saline soils.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Table S1: composition of nutrient solutions used for Experiments 1 and 2. Table S2: reaction constants used in GEOCHEM-EZ to calculate the interactions between various ligands and Cd in nutrient solutions. Figure S1: normalized Cd-edge XANES spectra of various tissues of Carpobrotus rossii grown in different treatments for 10 d. Figure S2: normalized Cd-edge XANES spectra of Cd standards and xylem sap of Carpobrotus rossii grown in different treatments for 10 d. Figure S3: k2-weighted EXAFS spectra of Cd standards and the xylem sap of Carpobrotus rossii grown for 10 d. Figure S4: normalized Cd-edge XANES spectra of the roots of Carpobrotus rossii grown in solutions for 24 h. Figure S5: concentrations of organic acids in various tissues of Carpobrotus rossii grown in different treatments for 10 d. Figure S6: concentrations of organic acids in roots of Carpobrotus rossii grown in solutions for 24 h.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was undertaken on the XAS beamline at the Australian Synchrotron (AS162/XAS/10855), Victoria, Australia. We thank Drs Peter Kappen and Bernt Johannessen (Australian Synchrotron) for their advice on the use of the XAS, Professor Peng Wang for valuable suggestions regarding the experimental design, Mr James O’Sullivan for helping with the XAS analyses, and Dr Zhiqian Liu for assistance with the LC–MS. Funding from the Australian Research Council for a Future Fellowship for P.M.K. (FT120100277) is acknowledged.

LITERATURE CITED

- Chai MW, Shi FC, Li RL, Liu FC, Qiu GY, Liu LM. 2013. Effect of NaCl on growth and Cd accumulation of halophyte Spartina alterniflora under CdCl2 stress. South African Journal of Botany 85: 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng MM, Wang P, Kopittke PM, Wang A, Sale PWG, Tang CX. 2016. Cadmium accumulation is enhanced by ammonium compared to nitrate in two hyperaccumulators, without affecting speciation. Journal of Experimental Botany 67: 5041–5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng MM, Wang A, Liu ZQ, Gendall AR, Rochfort S, Tang CX. 2018. Sodium chloride decreases cadmium accumulation and changes the response of metabolites to cadmium stress in halophyte Carpobrotus rossii. Annals of Botany. doi.org/ 10.1093/aob/mcy077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JM, Norvell WA, Clarke FR, Buckley WT. 2002. Concentration of cadmium and other elements in the grain of near-isogenic durum lines. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 82: 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S. 2006. Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie 88: 1707–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S, Palmgren MG, Kramer U. 2002. A long way ahead: understanding and engineering plant metal accumulation. Trends in Plant Science 7: 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers TJ, Colmer TD. 2008. Salinity tolerance in halophytes. New Phytologist 179: 945–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghnaya T, Slama I, Messedi D, Grignon C, Ghorbel MH, Abdelly C. 2007. Cd-induced growth reduction in the halophyte Sesuvium portulacastrum is significantly improved by NaCl. Journal of Plant Research 120: 309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han RM, Lefèvre I, Ruan CJ, Qin P, Lutts S. 2012. NaCl differently interferes with Cd and Zn toxicities in the wetland halophyte species Kosteletzkya virginica (L.) Presl. Plant Growth Regulation 68: 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R. 1990. Basic growth analysis: plant growth analysis for beginners. London: Unwin Hyman. [Google Scholar]

- Jones GW, Gorham J. 2002. Intra-and inter-cellular compartmentation of ions. In: L.uchli A, Lüttge U, eds. Salinity: environment-plants-molecules. Springer, Dordrecht 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lefèvre I, Marchal G, Meerts P, Corréal E, Lutts S. 2009. Chloride salinity reduces cadmium accumulation by the Mediterranean halophyte species Atriplex halimus L. Environmental and Experimental Botany 65: 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Peng K, Wang A, Lian C, Shen Z. 2010. Cadmium accumulation and distribution in populations of Phytolacca americana L. and the role of transpiration. Chemosphere 78: 1136–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutts S, Lefèvre I. 2015. How can we take advantage of halophyte properties to cope with heavy metal toxicity in salt-affected areas?Annals of Botany 115: 509–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahar A, Wang P, Ali A, et al. 2016. Challenges and opportunities in the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soils: a review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 126: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariem W, Kilani B, Benet G, et al. 2014. How does NaCl improve tolerance to cadmium in the halophyte Sesuvium portulacastrum?Chemosphere 117: 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell AE, Smith RM. 1974. Critical stability constants. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meychik NR, Nikolaeva JI, Yermakov IP. 2005. Ion exchange properties of the root cell walls isolated from the halophyte plants (Suaeda altissima L.) grown under conditions of different salinity. Plant and Soil 277: 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Munns R, Tester M. 2008. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59: 651–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson FA, Jones KC, Johnston AE. 1994. Effect of phosphate fertilizers and atmospheric deposition on long-term changes in the cadmium content of soils and crops. Environmental Science and Technology 28: 2170–2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkutlu F, Ozturk L, Erdem H, McLaughlin M, Cakmak I. 2007. Leaf-applied sodium chloride promotes cadmium accumulation in durum wheat grain. Plant and Soil 290: 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Panta S, Flowers T, Lane P, Doyle R, Haros G. Shabala S. 2014. Halophyte agriculture: success stories. Environmental and Experimental Botany 107: 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pitman MG, Läuchli A. 2002. Global impact of salinity and agricultural ecosystems. In: L.uchli A, Lüttge U, eds. Salinity: environment-plants-molecules. Springer, Dordrecht, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rauser WE. 1999. Structure and function of metal chelators produced by plants: the case for organic acids, amino acids, phytin, and metallothioneins. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics 31: 19–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel B, Newville M. 2005. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 12: 537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt DE, Prince RC, Pickering IJ, Raskin I. 1995. Mechanisms of cadmium mobility and accumulation in indian mustard. Plant Physiology 109: 1427–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt DE, Pickering IJ, Prince RC, et al. 1997. Metal accumulation by aquacultured seedlings of Indian mustard. Environmental Science and Technology 31: 1636–1644. [Google Scholar]

- Shaff JE, Schultz BA, Craft EJ, Clark RT, Kochian LV. 2010. GEOCHEM-EZ: a chemical speciation program with greater power and flexibility. Plant and Soil 330: 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Smolders E, McLaughlin MJ. 1996. Effect of Cl on Cd uptake by Swiss chard in nutrient solutions. Plant and Soil 179: 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency (EAT) 2000. Introduction of toxic metals. EPA/600/R-99/107 Cincinnati, OH: National Risk Management Research Laboratory, Office of Research and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez S, Goldsbrough P, Carpena RO. 2006. Assessing the relative contributions of phytochelatins and the cell wall to cadmium resistance in white lupin. Physiologia Plantarum 128: 487–495. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ. 1993. Accumulation of cadmium in crop plants and its consequences to human health. Advances in Agronomy 51: 173–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wali M, Fourati E, Hmaeid N, et al. 2015. NaCl alleviates Cd toxicity by changing its chemical forms of accumulation in the halophyte Sesuvium portulacastrum. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22: 10769–10777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Yin HX, Liu X, Li X. 2010. Salt affects plant Cd-stress responses by modulating growth and Cd accumulation. Planta 231: 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang BL, Shang SH, Zhang HT, Jabeen Z, Zhang GP. 2013. Sodium chloride enhances cadmium tolerance through reducing cadmium accumulation and increasing anti-oxidative enzyme activity in tobacco. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 32: 1420–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CJ, Sale PWG, Tang CX. 2016. Cadmium uptake by Carpobrotus rossii (Haw.) Schwantes under different saline conditions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23: 13480–13488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.