Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that in 2016 there were 39,782 people who were newly diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the United States (US). Of these new diagnoses, 70% were attributable to male-to-male sexual contact, and 64% occurred in the 20-to 29-year-old age group [1]. Despite accounting for only 12% of the US population, Blacks accounted for 45% of these cases [1]. Washington, District of Columbia (DC) has one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in the US, with a reported prevalence of 1.9% in 2016 [2]. Similar to the distribution of new HIV diagnoses nationally, the HIV epidemic in DC disproportionately affects men, accounting for 73% o f new HIV cases but only 47% of DC residents, and Blacks, accounting for 74% of new HIV cases but only 47% of DC residents. Notably, 18% of new HIV diagnoses in 2016 occurred in residents less than 25-years old [2].

Despite an 18% decline in the number of estimated annual HIV infections in the US from 2008 to 2014, the annual number of new HIV infections has remained unchanged from 2012 to 2016 [1]. Mathematical models of HIV transmission suggest that greater utilization of HIV pre exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) by men who have sex with men (MSM) at risk of HIV would result in large reductions in new HIV infections. Jenness et al. estimated that a 33% reduction in new HIV infections would be expected with a PrEP coverage of 40% among MSM over the next decade [3]. Kasaie et al. projected a 43% reduction in HIV incidence within 5 years if 80% of MSM reporting more than one sexual partner in the last 12 months took PrEP sufficiently to provide protection on 80% of days [4].

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved daily emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) for HIV PrEP in 2012. In 2014 the CDC defined indications for PrEP for HIV-uninfected adult MSM to include those in ongoing sexual relationships with HIV-infected male partners, those with multiple sexual partners, those performing commercial sex work, those with any condomless anal sex in the last six months, and those diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the last six months [5].

While the iPREX and iPERGAY trials demonstrated the efficacy of daily FTC/TDF for preventing the acquisition of HIV in MSM [6, 7], Black MSM (BMSM) were underrepresented in each of these studies, accounting for only 9% and 16% of study subjects, respectively. As a result, the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 073 study evaluated the feasibility, safety, and acceptability of PrEP among 225 BMSM and found a high rate of acceptance (79%) and high self-reported adherence to daily PrEP [8]. However, despite large increases in FTC/TDF prescriptions for PrEP in the US from 2012 through 2016, with an estimated 100,000 unique new PrEP prescriptions during this period [9, 10], Blacks have accounted for a disproportionately small number of these prescriptions. For PrEP prescriptions written from 2012 to 2015 where data on race was available, only 10% of PrEP prescriptions were written for Blacks [11].

PrEP uptake has also remained disappointingly low among young MSM. A 2011–2014 longitudinal survey of MSM living in Washington, DC showed that, despite the 18- to 24-year old participants self-reporting a 3-fold greater likelihood of being willing to take PrEP if it were free compared with those over 35-years old, only 7.7% of respondents at the end of the study reported use of PrEP in the previous 12 months [12]. A 2016 online survey of 239 MSM aged 16- to 24-years old living in the DC metropolitan area revealed that, while 80% of respondents were aware of PrEP, only 6% were taking PrEP > 4 days/week [13].

Studies evaluating the willingness of Black persons at risk of HIV to use PrEP have uncovered several potential barriers. The HPTN 061 study, a study of over 1,000 BMSM living in Atlanta, Boston, Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco and DC, found that 19% had reported healthcare-specific racial discrimination in the previous 6 months [14]. Eaton et al. surveyed 544 BMSM and found that 29% had reported experiencing racial and sexual orientation stigma from heath care providers and 48% had reported mistrust of medical establishments [15]. Finally, a study of 400 BMSM in Atlanta found that alcohol and substance use was associated with a lower likelihood of using PrEP [16].

Given the low uptake of PrEP among BMSM, despite experiencing a disproportionately high risk of HIV infection, we sought to design an intervention to increase PrEP uptake among young BMSM and pilot test the intervention using a randomized controlled trial design. Our objective was to establish a PrEP counseling center tailored to the gender-, race-, and sexual orientation-specific needs of young BMSM living in the DC metropolitan area. Given the known barriers to PrEP uptake described in the literature, our aim was to identify specific barriers to PrEP initiation for study participants, and then guide them to appropriate community resources in an effort to improve their understanding of, access to, and uptake of PrEP.

Methods

We recruited 50 HIV-uninfected, high-risk, young BMSM aged 16- to 25-years old living in the Washington, DC metropolitan area into this pilot study between August 2016 and February 2017. Using Jack’d, Grindr, Tinder and Adam4Adam social networking smartphone applications and using filters, we were able to target our study recruitment language to the desired age, race and gender of the study participants. Recruitment language consisted of “George Washington University in Washington, DC will be starting a small study of a counseling center for young gay or bisexual men interested in PrEP (Truvada). We are currently recruiting Black or African American men ages 16–25 who are HIV-negative to come to our clinic two different times (3 months apart). Eligible participants may receive up to $125 for participating, including $50 at the first visit.”

At the time this study started enrolling participants, FTC/TDF was only approved for those 18 years and older, although the FDA subsequently approved PrEP for adolescents in May 2018. We decided to include 16- and 17-year olds in our study based on 2013 CDC data which revealed that adolescents aged 15–24 in DC had among the highest incidence of STIs nationally [17]. Furthermore, DC public health law allows minors aged 12- to 17-years old to access sexual health services without parental approval and the DC Department of Health was already providing PrEP to adolescents at the time this study was performed.

Inclusion criteria included having been born male, self-identifying as male, self-identifying as Black or African American, reporting ≥1 instance of anal intercourse in his lifetime, testing HIV-negative at screening, and self-reporting no prior PrEP use. Although a lifetime history of anal intercourse is not a CDC criterion for initiating PrEP, our goal was to introduce PrEP to young BMSM living in a high HIV prevalence geographic area before they necessarily met current eligibility criteria. While recruitment materials identified the study as a PrEP study, expressing interest in PrEP was not an inclusion criterion. We sought to recruit individuals who might benefit from PrEP regardless of their baseline knowledge of or interest in PrEP.

Participants were provided written informed consent and subsequently underwent rapid HIV testing using Clearview COMPLETE HIV 1/2 assay (Alere, Waltham, MA). Participants with a non-reactive rapid HIV test completed a baseline survey about demographic characteristics, sexual risk behaviors and substance use in the last three months, perceived structural barriers to PrEP use, previous engagement with health care systems, and willingness to use PrEP. To assess willingness to use PrEP, we first provided participants with a description of PrEP: “PrEP is a way to lower the chance of getting infected with HIV by taking a pill once a day. PrEP (or its brand name, ‘Truvada’) has been approved by the FDA and has been shown to be safe and highly effective against HIV infection when it is taken every day. When taken every day, PrEP has been shown to reduce the risk of HIV infection in people who are at high risk by up to 92%. PrEP is much less effective if it is not taken every day.” Then, participants were asked, “If given the option for free, how likely are you to take a pill for PrEP each day to prevent HIV infection?,” with response options ranging on a 5-point Likert scale from “very unlikely to take PrEP” to “very likely to take PrEP.” Participants were also asked to rate their knowledge of PrEP (no, little, moderate, or high knowledge) and whether they plan to take PrEP in the next three months (yes, no, or maybe).

Data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at Children’s National Medical Center [18]. Participants also underwent STI testing including for gonorrhea and chlamydia and syphilis. Any participant diagnosed with a STI was provided or referred for treatment.

Following the baseline survey and HIV/STI testing, participants were randomized on a 1:1 basis to either the PrEP control group or the PrEP counseling center/intervention group. Participants randomized to the PrEP control group were seen by a health care provider who provided the participants PrEP education that included information on how PrEP works, indications for starting PrEP, use of FTC/TDF as PrEP including dosing, efficacy, side effects and importance of compliance, HIV risk reduction counseling, signs and symptoms of acute seroconversion, printed educational PrEP materials from the CDC, a list of local PrEP providers, Truvada copay assistance cards, pill case keychains, and condoms with lubricant. Participants were then asked to make an appointment with a provider to access PrEP. This information was provided via a standardized script by one of two physician assistants, and the visits lasted approximately 10 to 15 minutes.

In addition to all of the services provided to the PrEP control group, participants randomized to the PrEP counseling center group received personalized comprehensive counseling from a staff member who self-identified as a BMSM and had extensive outreach and counseling experience related to HIV prevention and PrEP needs. In addition to the PrEP education and sexual risk reduction counseling outlined above, this session involved assessing and addressing perceived barriers to initiating PrEP. Potential barriers that were explored included medical concerns, difficulty accessing and navigating health insurance, mental health needs, relationship problems, family problems, bullying, violence prevention, alcohol and substance abuse, legal issues, housing and clothing needs, and transportation challenges (see Appendix 1 for the case report form utilized by the counselor). Participants were asked to identify topics that they wanted to discuss based on their own preferences and needs, regardless of whether those needs were directly related to PrEP. They were then referred to the appropriate community resources based on their needs assessment.

This approach was modeled on the client-centered care coordination (C4) approach that was used successfully in the HPTN 073 study [5]. The C4 method is based on the SelfDetermination Theory of human motivation whereby conditions supporting an individual’s psychological needs foster motivation to engage in a targeted behavior such as access to and uptake of PrEP. In the HPTN 073 study this involved a registered nurse, social worker, or other trained personnel in collaboration with a clinical provider who performed ongoing assessments of client-identified health and psychosocial needs over several visits to promote and support PrEP use. It combined service referral, linkage and follow-up strategies to assist participants in addressing unmet psychosocial needs and barriers to health care. The strength of this model is the ability to address each patient’s unique needs, whether medical, social or behavioral. Our study adopted a similar approach but with more limited resources in terms of time and personnel.

Participants in the intervention group received assistance identifying and making an appointment with a PrEP provider or accessing other community resources as per their needs, and were given appointment reminders. They were provided with contact information for the PrEP counselor and were encouraged to call or text for follow-up questions, support, or new referral needs over the course of the study. The counseling session generally lasted between 20 and 45 minutes.

The participants were asked to return to the clinic after three months for a follow-up visit at which point they underwent repeat HIV and STI testing and completed a final REDCap survey assessing their experience accessing and using PrEP. Participants were asked whether they had seen a health care provider in the prior three months and whether they had talked to a provider about PrEP (outside of our study team). They were also asked whether they had taken PrEP in the last three months, whether they were currently taking PrEP, and if so, the average number of days a week they were taking PrEP. Those in the intervention arm also met with the PrEP counselor for one final session to discuss progress toward achieving any PrEP-related or other goals set at their initial counseling appointment. All participants received $10 travel vouchers at each visit, a $50 gift check at baseline and another $50 gift check at the follow up visit. Fifteen participants in the intervention group were invited to complete a qualitative exit interview and received another $25 gift check for this.

For the analysis, distributions of PrEP outcomes and other measured variables were compared between the two study arms. Chi square tests, or Fisher’s exact tests when cross tabulation cell frequencies were <5, were used to assess differences in proportions for categorical variables. All statistical tests were two-sided and p-values <0.05 were deemed statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (Cary, NC). The study procedures and all materials were approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health for studies with participants under 18 years of age.

Results

51 young BMSM provided informed consent, of whom 50 were eligible and enrolled. One person had a reactive screening HIV test at baseline and was excluded. The average age of participants was 21.7 years (range: 16 to 25). Distributions of socio-demographic characteristics, baseline PrEP awareness, and intention to use PrEP by study group are listed in Table I. Age, education, and employment status were distributed approximately equally in the intervention and control groups and the groups were well-balanced in regards to PrEP knowledge and likelihood of taking free PrEP. However, there were several statistically significant imbalances between the two study arms, that is, significantly more participants in the intervention group expressed a desire to take PrEP in the next 3 months than in the control group (52% vs. 24%, p=0.05), and more participants had health insurance in the control group than in the intervention group (96% vs. 72%, p=0.05). 86% o f participants had seen a medical provider in the preceding 12 months but only 26% had ever discussed PrEP with a provider.

Table I.

Baseline socio-demographic and PrEP specific characteristics of participants by study group (n=50).

| Variable | Intervention Group (n=25) |

Control Group (n=25) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n(%) | n(%) | χ2, p | |

| Age in years | 1.6, 0.21 | ||

| 16–20 | 5 (25) | 9 (36) | |

| 21–25 | 20 (75) | 16 (64) | |

| Education | 0.73* | ||

| High school or less | 11 (44) | 8 (32) | |

| Some college, 2-year degree, or technical/vocational school |

11 (44) | 13 (52) | |

| Finished college | 3 (12) | 4 (16) | |

| Current employment | 0.13* | ||

| Full-iirne | 6 (24) | 8 (32) | |

| Parl-iirne | 15 (60) | 8 (32) | |

| None | 4 (16) | 9 (36) | |

| Likelihood of taking free PrEPa | 0.34* | ||

| Very likely | 18 (75) | 14 (56) | |

| Likely | 3 (13) | 7 (28) | |

| Unsure | 3 (13) | 4 (16) | |

| Knowledge of PrEP | 0.8, 0.38 | ||

| Moderate to High | 17 (68) | 14 (56) | |

| Little or none | 8 (32) | 11 (44) | |

| Has health insurance | 18 (72) | 23 (96) | 0.049* |

| Has seen a medical provider in the last year | 18 (72) | 25 (100) | 0.010* |

| Has ever talked to a medical provider about PrEP | 7 (28) | 6 (24) | 0.1, 0.75 |

| Plans to take PrEP in the next 3 months | 0.050* | ||

| Yes | 13 (52) | 6 (24) | |

| Maybe/I don’t know | 12 (48) | 17 (68) | |

| No | 0 (0) | 2 (8) |

These p-values were obtained using Fisher’s exact tests

Regarding sexual behaviors, 88% of participants reported having had anal sex with a male partner in the 3 months prior to enrollment, of whom 80% had reported condomless anal sex, and of whom 31% had reported condomless anal sex with a male partner of HIV-positive or unknown status during that time period (Table II). There was no significant difference in baseline reported sexual behaviors between the two randomization groups.

Table II.

Sexual risk behaviors over the previous 3 months for study participants assessed at baseline visit and at the 3 month follow up visit

| Intervention Group, n (%) |

Control Group, n (%) |

χ2, p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Visit, n | 25 | 25 | |

| Had anal sex with a male partner in the last 3 months | 22 (88) | 22 (88) | 1.0* |

| Had condomless anal sex with a male partner in the last 3 months a | 16 (73) | 19 (87) | 0.46* |

| Had condomless anal sex with a male partner of HIV-positive or unknown status in the last 3 months b | 6 (38) | 5 (26) | 0.5,0.48 |

| 3 Month Visit, n | 25 | 23 | |

| Had anal sex with a male partner in the last 3 months | 21 (84) | 18 (78) | 0.72* |

| Had condomless anal sex with a male partner in the last 3 months a | 14 (67) | 13 (72) | 0.1,0.71 |

| Had condomless anal sex with a male partner of HIV-positive or unknown status in the last 3 months b | 3 (21) | 3 (23) | 1.0* |

These p-values were obtained using Fisher’s exact tests.

Among participants who had anal sex with a male partner in the last 3 months.

Among participants who had condomless anal sex with a male partner in the last 3 months.

Among the 25 participants randomized to the intervention group, four participants stated that they had no specific barriers that needed to be addressed. Of the remaining 21 participants, 14 participants had one need addressed, 5 participants had two needs, 1 participant had five needs and 1 participant had nine needs addressed. The most common need addressed was how to access PrEP, which was discussed with 21 participants, of whom 19 participants had a goal set to access and initiate PrEP, and 17 participants had a referral to a PrEP provider made. Other needs addressed included sexual risk behaviors (4 participants), accessing health insurance (3 participants), PrEP education (3 participants), and readiness to initiate PrEP (2 participants).

24 to the 25 participants in the intervention group indicated a preference for text-based versus phone-based support during the 3-month follow-up period, w hile one participant indicated a preference for phone-based support but was also not opposed to text-based conversations. Although not all participants expressed a desire to initiate PrEP, all reported being willing at baseline to com municate throughout the study period. Within one week of the baseline study visit, the PrEP counselor initiated communication with participants using their desired mode o f contact and continued to communicate with them throughout their study participation to confirm com pletion of previously identified action items. Although two participants were non-responsive to texts and phone calls throughout the study, 23 participants engaged in communication with the counselor about topics including how to schedule PrEP appointm ents with outside providers, general PrEP questions, concerns regarding possible side effects from taking PrEP, locations of free local STI testing services, and confirmation of upcoming follow-up study appointments.

48 participants completed the 3-month follow up visit; 25 participants in the intervention group and 23 participants in the control group. 25 participants (52%) saw a medical professional over the 3-month study period, and this was evenly balanced between the two groups (Table III). However, 85% of those in the intervention group had discussed PrEP with their medical provider compared with only 42% in the control group (p=0.04). Furthermore, six participants, all in the intervention group, had started PrEP (p=0.02) and four participants were still taking PrEP at the end of the study (p=0.11). Four of the six participant who initiated PrEP had been referred to a local community health center that specializes in LGBTQ healthcare. Both of the participants who stopped taking PrEP stated that not being currently sexually active was their reason for stopping. Of the participants who did not initiate PrEP, the most commonly cited reasons were not considering themselves at high risk for HIV acquisition, not having health insurance, and not being able to get in to see a medical practitioner.

Table III.

PrEP access and use by participants in the counseling intervention group compared to the control group assessed at the 3-month follow up visit (n=48).

| Variable | Intervention Group (n=25) | Control Group (n=23) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | χ2, p | |

| Has seen a medical provider in the last 3 months | 13 (52) | 12 (52) | <0.1,0.99 |

| Has talked to a medical provider about PrEP in the last 3 months a | 11 (85) | 5 (42) | 0.041* |

| Has taken PrEP in the last 3 months | 6 (24) | 0 (0) | 0.023* |

| Currently taking PrEP | 4 (16) | 0 (0) | 0.11* |

| Plans to continue taking PrEP b | 5 (83) | NA | NA |

| Plans to begin taking PrEP within the next 3 months c | 17 (81) | 13 (57) | 0.11* |

These p-values were obtained using Fisher’s exact tests.

Among participants who saw a medical provider in the last 3 months.

Among participants who have taken PrEP in the last 3 months. The denominator for the control group is 0, so calculation of a frequency and proportion is not applicable for the control group.

Among participants who are not currently taking PrEP.

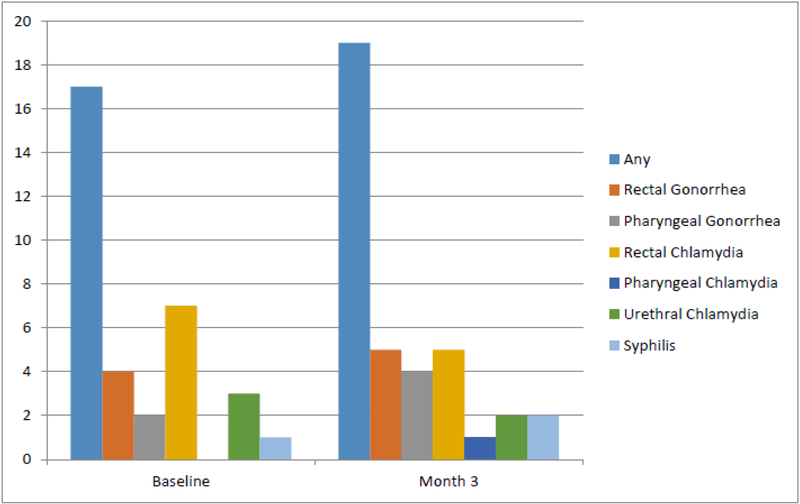

Two participants, one from each of the study groups, had reactive HIV tests at the 3-month visit. Neither participant was taking PrEP nor recalled any symptoms indicative of an acute retroviral syndrome. Both were referred for care but, to the best of our knowledge, did not seek medical care despite repeated efforts to assist with linkage to care. 22 participants (44%) were diagnosed with at least one STI over the course of the study; 13 participants were diagnosed with 17 STIs at their baseline visit and 13 participants were diagnosed with 19 incident STIs at their 3-month visit (Figure I). There was no difference in the incidence of new STIs between the two study groups. Four participants with a STI at baseline were also diagnosed with an incident STI at the 3-month visit. 58% of STIs were rectal infections and chlamydia was the most prevalent STI, accounting for 50% of cases detected. Of the participants, 15 (30%) were diagnosed with chlamydia, 11 (22%) with gonorrhea, and 3 (6%) with syphilis.

Figure I.

Number of sexually transmitted infections by specific etiology and site diagnosed at baseline visit and at the 3-month follow up visit

Discussion

In this randomized controlled pilot study of a PrEP counseling center tailored to the needs of young BMSM and implemented by culturally-competent staff self-identifying as BMSM, we demonstrated that it is possible to identify and address barriers to PrEP uptake in BMSM with limited personnel time and few extra resources. Addressing any identified barriers to PrEP resulted in more participants initiating PrEP in the counseling center arm compared to those who were not offered these counseling services. Building on other interventions developed to increase PrEP uptake in similar populations [19], this is the first study to demonstrate that access to a PrEP counseling center is associated with PrEP initiation, even despite the study not providing FTC/TDF. Our counseling intervention was operationalized as one PrEP counseling session lasting 20 to 45 minutes performed at the baseline visit followed by optional text- or phone-based support with the PrEP counselor, individualized to the needs of each participant. Thus, our findings demonstrate that a low-resource intensive counseling center can have a significant impact on PrEP utilization.

The CDC has estimated that approximately half a million MSM have an indication for PrEP [20]. Despite a significant increase in US PrEP prescriptions from 2012 through 2017, Blacks accounted for only 10% of prescriptions where information on race was available [11]. In order for the incidence of new HIV infections to substantially decline, PrEP uptake needs to increase, especially in the BMSM population which accounted for 45% of new HIV infections in 2015 [1]. Our high number of participants with incident HIV infections (4%), prevalent (26%) and incident (27%) STIs highlights the critical need to focus efforts for young BMSM by developing innovative targeted strategies to engage this population in HIV prevention services.

There are several explanations for the lag in PrEP uptake. A major barrier for MSM interested in starting PrEP is finding PrEP literate providers. HIV practitioners have the knowledge and willingness to prescribe PrEP, but have a low exposure to HIV-negative MSM, limiting their impact on PrEP uptake [21]. In contrast, primary care providers (PCPs) are the first point of contact for the majority of patients in healthcare, and represent the ideal venue to initiate PrEP in those at risk. There is evidence that this is starting to occur. A survey of over 1,500 PCPs found an increase in PrEP awareness from 24% to 66% between 2009 and 2015 [22]. Unfortunately, a similar increase in PrEP prescribing has not followed. A survey of PCPs revealed that only 17% o f PCPs had ever prescribed PrEP compared to 64% of HIV providers [23]. Reasons given included limited PrEP knowledge, the time needed for risk-reduction counseling, lack of clinical capacity, and the perceived burden of PrEP monitoring. This is mirrored by our study in that 86% of our participants at enrollment had reported having seen a medical provider in the past 3 months, yet only 26% had ever talked to the provider about PrEP and none had received a prescription. PrEP education for medical providers that focuses on assessment of sexual orientation, risk of HIV acquisition and barriers to PrEP uptake is integral to improving the level of PrEP coverage. Ideally this education should be directed at staff working in primary care settings including, but not limited to, physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants, and medical assistants, even if the outcome is a referral to a PrEP-literate provider.

However, referral from a primary care setting to a PrEP-literate provider presents another potential barrier to PrEP uptake, especially in younger and less medically literate populations. Our counseling center has demonstrated that this barrier can be largely overcome by a brief individualized counseling session by a PrEP-literate staff member. Despite 52% of participants in each group having seen a medical provider over the 3-month study, 85% of participants in the intervention arm had talked with their provider about PrEP compared with only 42% of participants in the control arm (p=0.04). Furthermore, a statistically significant difference in PrEP initiation was observed between the two study arms, in that six participants (24%) in the intervention arm had initiated PrEP during the 3-month study period while no participants initiated PrEP in the control arm.

Other studies have examined behavioral strategies to increase PrEP uptake in high-risk youth. Hosek et al. evaluated a 2-day group-based behavioral intervention and individual risk reduction counseling in 58 MSM aged 18 to 22 years old, 93% of whom were of color, and found a high level of acceptance [24]. An ongoing study by Young et al. aims to evaluate social network interventions on PrEP uptake in young BM SM by using trained BM SM as peer change agents [25]. Our model is similar to this study in that the counseling in the intervention group was performed by someone of the same race, gender and sexual orientation as our participants.

There are several limitations to our study. This randomized controlled trial was not blinded, as it was not feasible to blind participants or staff as to which group they were in. To minimize potential bias resulting from differential treatment of patients randomized to the intervention and control groups (outside of the actual intervention itself), the same two staff members saw all participants at enrollment and month 3 visits for visit procedures, regardless of group assignment, and followed a consistent script with regard to PrEP education and counseling. A separate staff member conducted all of the counseling session for participants randomized to the counseling center group.

Given that this was a pilot study, our study sample was small with some inevitable imbalances between the two groups after randomization - in particular, a statistically significant greater baseline desire among participants in the intervention group to take PrEP in the next 3 months. On the other hand, the significantly greater proportion of health insurance coverage in the control group might have been expected to favor PrEP uptake in these participants, which did not occur.

While we found a statistically significant association between our intervention and PrEP uptake, we were unable to utilize multivariable regression methods to adjust for these differences since no participants in the control group took PrEP. As a next step, this counseling center should be tested in a larger study population.

The short duration of this study makes it difficult to know the extent to which participants will remain adherent to PrEP, although it is possible that multiple rounds of the counseling overa longer period of time would have led to higher levels of uptake and adherence. Social desirability bias might have influenced the self-reported survey data. To minimize this, we used a computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) survey self-administered on a laptop computer. Our counselor spent between 20 to 45 minutes with each participant in the resource center which might strain the human resources of smaller primary care practices. Yet, as a one-time (vs. longer-term) intervention, this is still likely to be a low-resource intervention that is readily scalable. Lastly, this study was conducted in Washington, DC, a city with a relatively large number of PrEP resources, many of which were free, to which we could refer participants. This may not be reflective of other geographic regions or populations.

In conclusion, this study offers novel evidence of the potential utility of a brief, low-cost counseling-based approach for facilitating PrEP uptake among young BMSM with the aim of improving HIV prevention in this high-risk population. When PrEP counseling is performed in a culturally competent setting by a culturally sensitive counselor, this can further improve PrEP uptake in young BMSM. The results of this study should be further validated by implementing this model in a larger community-based setting.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge that all authors have contributed to this work and have seen and approved the manuscript. The contents of this manuscript have not been published and the manuscript is not being considered for publication elsewhere.

Appendix

| Counseling Intervention Case Report Form | |

|---|---|

| Please indicate which of the following counseling needs were discussed and/or addressed during this session. |

Please indicate whether each goal and referral were achieved or completed. |

| ☐ PrEP Education → Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Readiness to initiate PrEP

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Accessing PrEP

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Adhering to PrEP

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Sexual risk behaviors

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ HIV/STI education

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Medical concerns or problems

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Accessing health insurance

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Understanding/navigating health insurance

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Mental Health

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Relationship problems

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Family problems

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Bullying

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Alcohol or substance abuse

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Legal issues

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Finding stable housing

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Clothing or food bank assistance

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Transportation assistance

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Violence prevention

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

| ☐ Other:

→ Goal set? ☐ ____________________________________________ → Referral made? ☐ _______________________________________ |

→ Goal achieved? ☐ → Referral completed? ☐ |

|

Does the participant plan to call/text the study cell phone for

questions, support, or referrals related to his needs? ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Maybe |

Did the participant ever call/text

the study cell phone? ☐ Yes ☐ No |

| Intials: ______ Date: __________ | Intials: ______ Date: __________ |

Footnotes

Compliance in Ethical Standards:

Funding: The study was funded by a grant from the District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research (Grant:1P30AI117970–01).

Conflicts of Interest: Author Marc Siegel has received research funding from Gilead Sciences for an unrelated research study. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants: The study procedures and all materials were approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health for studies with participants under 18 years of age. All study procedures have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.CDC. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2015. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hivsurveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf..

- 2.District of Columbia Department of Health HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD, and TB Administration. The Annual Epidemiology & Surveillance Report. 2017. Available from: https://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/publication/attachments/HAHSTA%20Annual%20Report%202017%20-%20Final%20%282%29%20%282%29.pdf.

- 3.Jenness S, Goodreau S, Rosenberg E, et al. Impact of the Centers for Disease Control’s HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Guidelines for Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States. J Infect Dis, 2016. 214(12): 1800–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasaie P, Pennington J, Shah M, et al. The Impact of Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: An Individual-Based Model. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2017. 75(2):175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States - 2014 Clinical Practice Guideline. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf.

- 6.Grant R, Lama J, Anderson P, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med, 2010. 363(27): 2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molina J, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On-Demand Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men at High Risk for HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med, 2015. 373(23): 2237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheeler D, Fields S, Nelson L, et al. HPTN 073: PrEP Uptake and Use by Black Men Who Have Sex With Men in 3 US Cities (abstract: 883LB). Presented at: The Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2016; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mera R, McCallister S, Palmer R, et al. Truvada (TVD) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States (2013–2015). Presented at: 21st International AIDS Conference; 2016; Durban, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mera R, Magnuson D., Trevor H, Bush S, Rawlings K, McCallister S. Changes in Truvada (TVD) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States: (2012–2016). Presented at: 9th IAS Conference on HIV Science 2017: Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bush S, Magnuson D, Rawlings K, et al. Racial Characteristics of FTC/TDF for Pre exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Users in the US. Presented at: American Society for Microbiology Microbe 2016: Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrick R, Forrest D, Cardenas G, et al. , Awareness, Willingness, and Use of Pre exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in Washington, DC and Miami-Dade County, FL: National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 2011 and 2014. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2017. 75 Suppl 3: S375–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy M, Magnus M, Kuo I, et al. An evaluation of the PrEP care continuum among men who have sex with men aged 16–25 in Washington, DC. Presented at: HIV Research for Prevention; 2016; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irvin RW ilton L, Scott H, et al. A study of perceived racial discrimination in Black men who have sex with men (MSM) and its association with healthcare utilization and HIV testing. AIDS Behav, 2014. 18(7): 1272–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eaton L, Driffin D, Kegler C, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D and Cherry C, The role o f stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement o f black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health, 2015. 105(2): p. e75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaton L, Driffin D, Kegler C, et al. The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health, 2015. 105(2): e75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reportable STDs in Young People 15–24 Years of Age, by State. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/by-age/15-24-all-stds/default.htm.

- 18.Harris P, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform, 2009. 42(2): 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor S, Psaros C, Pantalone D, et al. “Life-Steps” for PrEP Adherence: Demonstration of a CBT-Based Intervention to Increase Adherence to Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Medication Among Sexual-Minority Men at High Risk for HIV Acquisition. Cogn Behav Pract, 2017. 24(1): 38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith D, Van Handel M, Wolitski R, et al. Vital Signs: Estimated Percentages and Numbers of Adults with Indications for Preexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Acquisition--United States, 2015. J Miss State Med Assoc, 2015. 56(12): 364–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty J, et al. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav, 2014. 18(9): 1712–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith D, Van Handel M, Huggins R. PrEP Awareness and Attitudes in a National Survey of Primary Care Clinicians in the United States, 2009–2015. PLoS One, 2016. 11(6): p. e0156592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petroll A, Walsh J, Owczarzak J, et al. PrEP Awareness, Familiarity, Comfort, and Prescribing Experience among US Primary Care Providers and HIV Specialists. AIDS Behav, 2017. 21(5): 1256–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosek S, Siberry G, Bell M, et al. The acceptability and feasibility of an HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trial with young men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2013. 62(4): 447–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young L, Schumm P, Alon L, et al. , PrEP Chicago: A randomized controlled peer change agent intervention to promote the adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among young Black men who have sex with men. Clin Trials, 2018. February;15(1):44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]