Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the hepatotoxicity of statins, as determined by serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), in children and adolescents with dyslipidemia in real world clinical practice.

Study design:

Clinical and laboratory data were prospectively collected between September 2010 and March 2014. We compared ALT levels between patients prescribed versus not prescribed 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), and then compared ALT before and after initiation of statins.

Results:

Over the 3.5-year observation period, there were 2704 ALT measurements among 943 patients. The mean age was 14 years; 54% were male, 47% obese, and 208 patients were treated with statins. Median follow-up after first ALT was 18 months. The mean (SD) ALT in statin and non-statin users was 23 (20) U/L and 28 (28) U/L, respectively. In models adjusted for age, sex and race, ALT was 2.1 U/L (95% CI 0.1, 4.4; p=0.04) lower among statin users, which was attenuated after adjustment for weight category. Patients started on statins during the observation period did not demonstrate an increase in ALT over time (ALT 0.9 U/L [95% CI −5.2, 3.4] increase per year; p=0.7).

Conclusion:

In our study population, we did not observe a higher burden of ALT elevations among pediatric patients on statins as compared to those with dyslipidemia who are not on statins, supporting the hepatic safety of statin use in childhood.

Keywords: Pediatrics, Dyslipidemia, Hepatology, Statins

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the most common cause of death in the United States and a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality (1). Elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is a well-established causal risk factor for ASCVD, and statins (3-hydroxyl-3methylglutaryl coenzyme A [HMG-CoA] reductase inhibitors) have been demonstrated to markedly reduce the risk of ASCVD (2). Because atherosclerosis begins in childhood (3), statins are recommended for children and adolescents with marked elevations in LDL insufficiently responsive to diet and lifestyle modification (4). Statins have been reported to have a low but measurable rate of hepatotoxic effects in adult and pediatric statin trials (5–13). Despite the widespread use of statins in childhood, the hepatotoxic effects of statins in real-world clinical pediatric practice are largely unknown.

The spectrum of hepatic adverse effects reported with statin use range from asymptomatic liver enzyme elevation to liver failure (14). In a meta-analysis of eight randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials in children and adolescents, lasting two months to two years in duration, liver enzymes were elevated in 1–5% of participants treated with statins (9). However, these studies generally took place prior to the recognition of the obesity pandemic and increase in prevalence of pediatric-onset non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (15). The effect of statins in a contemporary pediatric population with concomitant obesity-related comorbidities is unknown. Therefore, we evaluated the hepatotoxicity of statins in children and adolescents by examining differences in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations obtained as part of clinical care in a single large pediatric preventive cardiology practice within a quality improvement (QI) initiative.

METHODS

Study design

The Subspecialty Lipid Standardized Clinical Assessment and Management Plan (SCAMP®) is a QI initiative that was implemented on September 1, 2010 in the Preventive Cardiology Program of Boston Children’s Hospital to guide the assessment and management of children and adolescents seen in an outpatient referral clinic for lipid disorders. The Subspecialty Lipid SCAMP prospectively collects clinical data for each patient encounter, including interval blood draws, from providers (physicians, fellows, nurse practitioners and nurses) using standardized forms. In addition to collecting pertinent health information, the SCAMP suggests management using treatment algorithms informed by the 2011 US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Expert Panel Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Childhood and Adolescence (6). Each patient is seen for three initial visits, separated by three months, and further follow-up is tailored to the type and severity of their lipid disorder. Statins are recommended to be initiated in patients with elevated LDL cholesterol in accordance with the national guidelines. The SCAMP recommends obtaining ALT measurements on all patients prior to starting statin therapy; providers are also advised to measure ALT in all patients with dyslipidemia with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 95th percentile to screen for NAFLD. The specific statin prescribed is left to the discretion of the practitioner, and all statin medications were included in this analysis.

Examining ALT outcomes among pediatric patients using statins was one of the pre-specified QI goals of the SCAMP; the specific analysis plan was determined post-hoc. This project was approved by the research ethics board at the Boston Children’s Hospital with a waiver of individual participant consent.

Study population

The eligible sample included all patients ≤21 years of age evaluated in the Preventive Cardiology Program during the QI observation period from September 1, 2010 to March 1, 2014 with at least one serum ALT measurement. Eligible patients were divided into two groups: 1) patients with ALT measured while on statins (started on statins before or during the observation window), and 2) patients with ALT measured without statin use (either a never statin user or a pre-statin user).

Clinical assessments

Weight was measured with an electric scale to the nearest 0.1 kg while patients were wearing light clothing and no shoes. Height was measured with a vertical stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (cm)2. Since some patients were over 18 years of age and outside of percentile norms, a three-level weight category variable was defined as: obese (BMI ≥95%ile for patients under 18 years or ≥30 kg/m2 for patients ≥18 years), overweight (BMI 85–94th%ile for patients under 18 years or 25 – 29.9 kg/m2 for patients ≥18 years) and normal weight (BMI 5–84th%ile for patients under 18 years or 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2 for patients ≥18 years). Race was self-reported to administrative staff as part of usual clinic procedures; we further categorized race as white, black, other, and unknown.

Laboratory assessments

ALT and cholesterol measurements were obtained from fasting peripheral blood samples, generally after at least an 8-hour fast, on the morning of the clinic visit or at an outside laboratory around the time of the clinic visit. ALT and cholesterol measurements obtained between clinic visits were also included in the analyses. Total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides (TG) levels were measured and LDL-C was calculated according to the Friedewald equation. Direct LDL was generally obtained if TG levels were ≥ 400 mg/dL. Normative values for ALT were based on the North American Society for Pediatric Gastoenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition 2016 clinical practice guidelines for NAFLD; upper limits of normal (ULN) were: ≥ 26 U/L for boys, and ≥ 22 U/L for girls (16). Elevated ALT was analyzed as a continuous variable and, secondarily categorized as minor (>1 to <3x ULN), medium (≥3 to <5x ULN) and high (≥5x ULN) elevations. Major hepatic effects due to statin therapy were defined as clinically detected cases of hepatic injury (elevated serum ALT > 3x ULN without preceding hepatic disease that developed while on statin therapy). Meeting criteria for statin initiation was defined as an LDL ≥ 190 mg/dL and ≥ 10 year of age or an LDL ≥ 160 mg/dL and a family history of premature cardiovascular disease events and ≥ 8 year of age.

Quality control of database

The QI dataset was interrogated for entry errors. All anthropometric and laboratory values outside three standard deviations (SD) of the cohort mean were manually confirmed in the hospital electronic health record. Data points missing from the SCAMP dataset and available in the medical record were extracted and added to the dataset.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated as appropriate for distribution. Baseline characteristics between statin use groups were compared using chi-squared and ANOVA tests. We tested if there was a difference in ALT levels at the first visit among patients never treated during the observation window among those meeting criteria to start statins as compared to not meeting criteria in linear regression models adjusted for age, sex, and race. We then constructed multivariable adjusted mixed effect models to account for repeated measures with ALT as the outcome, statin use as the independent variable of interest, and adjusted for age, sex and race. An additional model also adjusted for a three-level weight category variable (obese, overweight, and normal weight). Covariates were chosen based on known relationships with serum ALT levels. Participant ID was specified as a random effect and all other covariates as fixed effects. For the longitudinal analyses of patients initiating statins during the observation period, statin use (post as compared to pre) was examined as the independent variable of interest. In addition, a continuous time post-statin start variable was examined to evaluate if ALT rises over time after the initiation of statins. A Gaussian distribution and an ‘identity’ link function was utilized for continuous ALT measure outcomes (linear mixed effect model using restricted maximum likelihood estimation), allowing random intercepts and slopes for the longitudinal models. Analyses were conducted in R version 3.2.1 (Vienna, Austria) using the lme4 package (17). Degrees of freedom were obtained using the Satterthwaite approximation from the lmerTest package (18). The statistical significance threshold was defined as a two-sided p-value < 0.05.

RESULTS

Description of overall study sample

Among 1521 unique patients seen in the Preventive Cardiology Program during the 3.5-year observation window, 943 patients had at least one ALT measurement, for a total of 2704 ALT measurements (median [Q1, Q3] number of ALT per patient of 2 [1, 4]; distribution of number of ALT measures per patient presented in Supplemental Figure 1). Median (Q1, Q3) follow-up after the first ALT was 18 (9, 30) months, comprising a total of 11,565 patient-months of follow up. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of the overall study sample was 14 (4) years, of which 46% were female. Twenty percent of the patients were overweight and 47% were obese. The sample was predominantly white (62%), 7% were black, 17% were of other races, and 14% were of unknown race (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of study sample

| Statin status of study sample during observation period | p-value from χ2 or ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always on statin | Started during study | Never on statin | |||||

| n with variable | n (%) or mean (SD) | n with variable | n (%) or mean (SD) | n with variable | n (%) or mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 111 | 14 (4) | 97 | 13 (4) | 735 | 16 (4) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 111 | 45 (41%) | 97 | 52 (54%) | 735 | 340 (46%) | 0.2 |

| Race | 99 | 87 | 628 | 0.03 | |||

| -White | 79 (80%) | 71 (82%) | 433 (69%) | ||||

| -Black | 4 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 59 (9%) | ||||

| -Other | 16 (16%) | 12 (14%) | 126 (22%) | ||||

| Weight | 111 | 97 | 735 | < 0.001 | |||

| -Obese | 35 (32%) | 25 (26%) | 386 (53%) | ||||

| -Overweight | 9 (8%) | 19 (20%) | 157 (21%) | ||||

| BMI Z-score(<18 years) | 102 | 0.7 (1.2) | 93 | 0.7 (1.3) | 680 | 1.5 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| CVD risk factor | |||||||

| Suspected insulin resistance | 105 | 19 (18%) | 92 | 19 (21%) | 690 | 265 (38%) | < 0.001 |

| T1DM | 106 | 2 (2%) | 94 | 5 (5%) | 713 | 18 (3%) | 0.3 |

| T2DM | 105 | 2 (2%) | 94 | 1 (1%) | 713 | 14 (2%) | 0.8 |

| Elevated blood pressure | 106 | 15 (14%) | 92 | 7 (8%) | 694 | 103 (15%) | 0.2 |

| Smoking or smoke exposure | 105 | 11 (10%) | 93 | 6 (6%) | 691 | 94 (14%) | 0.1 |

| Family history | |||||||

| Obesity | 35 | 13 (37%) | 56 | 27 (48%) | 432 | 292 (68%) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 94 | 76 (81%) | 90 | 68 (76%) | 647 | 332 (51%) | < 0.001 |

Legend: Data are presented as mean and (standard deviation). Significance considered p<0.05. Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; T2DM, Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Description of pediatric patients on statins and non-statin users

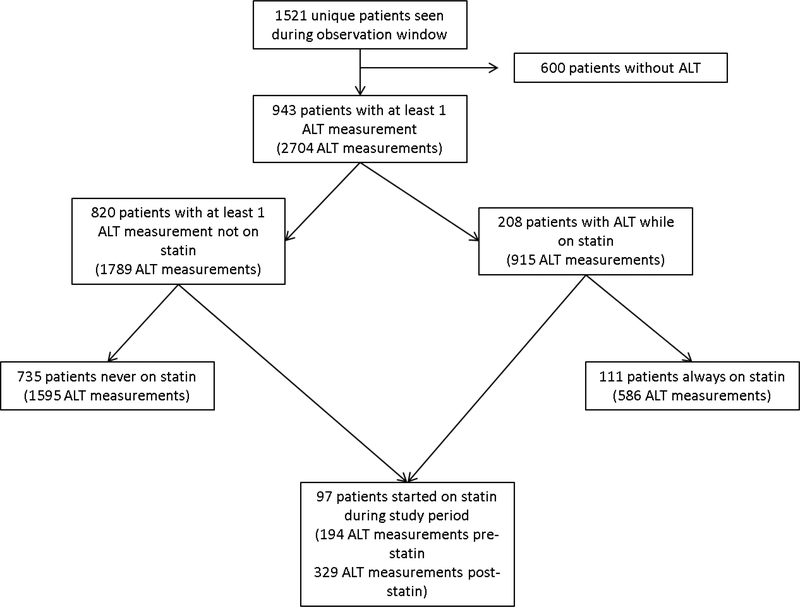

Of the 943 included patients (2704 ALT measures), there were 208 patients with at least one ALT measured on statins (total of 915 ALT measures) and 820 patients with at least one ALT obtained when not on statins (total of 1789 ALT measures). Patients contributed to both groups if they were prescribed statins during the observation period and ALT was measured both prior and after the start of treatment. Further breakdown of the study sample is shown in Figure 1. Characteristics at the initial visit during the observation period are presented in Table 1. The mean (standard deviation) LDL at the first visit in the observation window of the 734 patients never on statins during the observation window was 141 (53) mg/dL. A total of 72 patients (9.8%) met criteria for statin initiation but were not started on statins during the observation window. Among those never treated during the observation window but meeting criteria for statin initiation, the mean (SD) ALT was 23 (24) U/L as compared to a mean 27 (26) U/L in the never treated and not meeting criteria for statin therapy. This was not statistically different (ALT 3.4 [3.2] U/L lower among those meeting statin initiation criteria in an age, sex, and race adjusted model, p=0.3). Three patients (4%) of the never treated, meeting statin initiation criteria group had an ALT ≥3 times ULN, which is of similar proportion (3.5%, 23 patients) in the never treated, not meeting statin initiation criteria (p=1).

FIGURE 1:

Breakdown of study sample of patients with dyslipidemia assessed in a pediatric preventive cardiology program. ALT = alanine aminotransferase.

Comparing ALT between statin and non-statin users

Distributions of ALT measurements between statin and non-statin users are presented in Figure 2. Unadjusted mean (SD) ALT of all measures among statin users and non-statin users was 23 (20) U/L and 28 (28) U/L, respectively. In mixed models adjusting for age, sex, race and accounting for repeated measures, ALT was 2.2 U/L (95% CI 0.1, 4.4; p=0.04) lower in statin users as compared to those not prescribed statins. The difference in ALT between statin and non-statin users was largely attenuated after additionally adjusting for the higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in the non-statin user group (ALT −1.3 U/L [95% CI −3.5, 0.9]; p=0.2).

FIGURE 2:

Distribution of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations among pediatric patients with dyslipidemia that are on statins and not on statins.

We conducted a sensitivity model further subdividing into four groups (always on statin during observation period, never on statin during observation period, pre-statin initiation, and post-statin initiation) and found consistent results: children and adolescents who were always on statins during the observation period had ALT levels that were on average 4.6 U/L (95% CI 1.0, 8.3; p=0.01) lower compared to the never on statin group (full results in Supplement Table 1). Similar to the two-group analysis, the lower ALT levels seen among statin user subgroups in the sensitivity analyses were also attenuated after additional adjustment for weight category.

Clinical ALT threshold cutoff differences between statin and not prescribed statin users

ALT was secondarily examined based on gender-specific threshold cutoffs (males ≥26 U/L and females ≥22 U/L) and presented in Table 2. Among the 2704 ALT measures, there were 26 ALT (0.01%) that were ≥5x ULN. Elevated ALT ≥5x ULN was observed in 5 of the 915 ALT measures on statins (0.5%) and 21 of the 1789 ALT measures among non-statin users (1.2%). There were too few high ALT values for hypothesis testing in regression models (models failed to converge). No clinically relevant statin-related hepatotoxic events were detected.

Table 2:

Number of liver enzyme concentrations above thresholds for pediatric patients with dyslipidemia stratified by statin use.

| Patients not on statins | Patients on statins | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ALT measures | % of ALT measures | Number of unique patients | Number of ALT measures | % of ALT measures | Number of unique patients | |

| Normal ALT | 1130 | 63 | 618 | 664 | 73 | 179 |

| ALT 1 - <3x ULN | 581 | 32 | 323 | 237 | 26 | 87 |

| ALT 3 - <5x ULN | 57 | 3 | 41 | 9 | 1 | 7 |

| ALT ≥ 5x ULN | 21 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 0.5 | 3 |

Note: The same patient can be counted more than once if they contribute ALT values to more than one group. Abbreviation: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ULN, upper limit of normal

Comparing ALT in the same individuals prior to and during statin therapy

ALT measures obtained both before and after initiation were available in 80 of the 97 patients started on statin therapy during the observation period. Five patients had ALT available only prior to starting statins, predominately due to insufficient follow-up time after starting statins in the observation period. Twelve patients had ALT available only on statin therapy as pre-statin values were likely obtained prior to the observation period. We did not observe a difference in mean ALT levels obtained on statins as compared to ALT levels drawn prior to starting statins (0.9 U/L [95% CI −5.2, 3.4], p=0.7). Elevated ALT (either ≥3 to <5xULN, or ≥5xULN) occurred infrequently in this group. Out of 523 ALT measures, there were a total of 8 elevated ALT measures (1.5%). Additionally, examining the slope of ALT change after starting statins, we did not detect an increase in ALT over time (ALT −0.7 U/L [SE 0.1.2] per year lower post statin initiation, p=0.6; Supplemental Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

We studied adverse hepatic effects, as measured by serum ALT, among pediatric patients prescribed HMG CoA reductase inhibitors compared to untreated patients in a large pediatric subspecialty lipid clinic population. Comparing those on statins to those not on statins, and evaluating children who began treatment during the observation period, we found no evidence of major hepatic events due to statin therapy. In fact, in models adjusted for age, sex, and race, mean ALT was greater in non-statin users by approximately 2 U/L, a difference that dissipated after adjustment for the greater frequency of overweight and obesity in non-statin users. Thus, suggesting that the elevation in ALT in pediatric dyslipidemia patients not prescribed statins was likely related to excess weight and possible NAFLD.

Hepatotoxicity is an often-cited adverse effect of statins, yet in recent years the association between statin therapy and liver injury has been questioned. Clinical trials in adults have only weakly linked statins to elevated liver enzymes with reports that 0.1–2.7% of adults experience statin hepatotoxicity, defined as ALT greater than 3x ULN (14) (19). Liver enzyme levels do not correlate with histopathologic changes (5) and statins are rarely associated with clinically significant liver injury. There is even suggestion that statins may improve liver enzymes in certain patients. The Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary Heart Disease Evaluation study reported improvement in liver enzymes in patients with mild to moderate liver enzyme elevation treated with statins (8). In pediatric randomized controlled trials, hepatotoxicity rarely, if ever, is reported (20)(21). In our real-world clinical practice review, we similarly found very few treated patients had greater than a 3-fold elevation in ALT, a frequency not in excess of the number of children and adolescents with elevated ALT not on statins. Despite the established efficacy of statins in reducing ASCVD, hepatic side effects are common concerns cited by patients and providers that limit their administration. In a 2010 survey of 937 adult primary care physicians, 37% expressed concern about statin hepatotoxicity risks (22). Our study does not support hepatotoxicity as a major consequence of statin use in children.

The 2011 NHLBI Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents recommends obtaining a baseline ALT and then rechecking at 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 3 months, then every 3–4 months in the first year, and every 6 months thereafter (4). A recent update by the Statin Liver Safety Task Force recommends obtaining baseline liver enzymes before statin administration in adult patients, however serial monitoring of liver enzymes receiving long term statin therapy was not recommended (23). Our findings support adapting the recommendation of the Statin Liver Safety Task Force for children and adolescents. Over time, we found no significant group trends in elevation of liver enzymes amongst statin users and we found no clinically relevant hepatotoxic events attributable to statins.

The strengths of the study include the number of patients included in the analysis (n=934) as well as the long duration of follow-up (11,564 patient months); this is one of the largest studies to evaluate statin hepatotoxicity in a pediatric cohort.

This observational study also has limitations. We were underpowered to detect rare events of hepatotoxicity. We were not able to examine specific statins or perform a dose-based analysis due to the initial design of the data capture forms. Frequency of follow up was driven by clinical care and therefore varied among patients and between those prescribed versus not prescribed statin therapy. This analysis was collected as part of a QI effort, not as a clinical trial, and symptoms were not systematically collected in patients not prescribed statins. We also did not have systematic collection at regular time intervals of ALT measures among patients not prescribed statins; however, our practice was to collect ALT measures at all routine visits among pediatric patients on statins. We do not have liver biopsy data in patients with elevated liver enzymes to confirm NAFLD, nor did we collect information about what liver specific work-up was done in patients with elevated liver enzymes. The comparison group was enriched for obese patients with lipid disorders, with a presumed higher burden of NAFLD. Our study sample is not representative of children with liver disease and whether they tolerate statins or if their condition improves with statins. Our study sample is representative of a referral population of children and adolescents with dyslipidemia. We did not find evidence that there is a large group of pediatric patients meeting criteria for starting statins but were not initiated due to elevated ALT in our study population. The primary reason for not initiating statin therapy among pediatric patients meeting criteria is family preference to wait or to provide a longer period to work on lifestyle modifications. Larger studies using a blinded randomized controlled design could systematically assess long term side effects of statins started in childhood incorporating children of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds.

In conclusion, in this large single-center review of children and adolescents with lipid disorders cared for in a subspecialty pediatric Preventive Cardiology Program, there was no evidence for statin associated liver toxicity assessed by ALT, and no reported clinical symptomatology consistent with hepatic injury. These findings require further external validation but support the adult Statin Liver Safety Task Force recommendations to avoid frequent serial monitoring of LFTs in asymptomatic children and adolescents on statins. We did not find evidence that liver toxicity should prevent providers or families from appropriately utilizing statins in the pediatric age range.

Supplementary Material

What is known?

Statins (3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and recommended for use in children and adolescents for the treatment of markedly elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol unresponsive to diet and lifestyle change.

Statins have a low but measurable rate of hepatotoxic events as reported in studies in adults.

What is new?

This study assesses the hepatotoxicity of statins in children and adolescents in contemporary clinical practice.

In this large single center review, there was no evidence of statin-related hepatotoxicity in the pediatric age range.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

MMM was supported by the NHLBI K99 HL136875 and The Tommy Kaplan Fund, Department of Cardiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA. JPZ was funded by NHLBI K23 HL111335

The funding sources had no role in the design of this study and did not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

No author has any relevant disclosures. NKD is currently an employee of Shire Plc; however, the study, analysis, and preparation of the final manuscript occurred prior to beginning this employment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of abnormal lipid levels among youths --- United States, 1999–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010. January 22;59(2):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, Merz CNB, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults. Circulation. 2013; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braamskamp MJAM Wijburg FA, Wiegman A Drug Therapy of Hypercholesterolaemia in Children and Adolescents. Drugs. 2012. April;72(6):759–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011. December;128 Suppl :S213–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bader T The Myth of Statin-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrick C, Bahrainy S, Gill EA. Statins and the liver. Cardiol Clin. 2015. May;33(2):257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macedo AF, Taylor FC, Casas JP, Adler A, Prieto-Merino D, Ebrahim S. Unintended effects of statins from observational studies in the general population: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014. December 22;12(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Gossios TD, Griva T, Anagnostis P, Kargiotis K, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term statin treatment for cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease and abnormal liver tests in the Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary Heart Disease Evaluation (GREACE) Study: a post-hoc analysis. Lancet. 2010. December 4;376(9756):1916–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belay B, Belamarich PF, Tom-Revzon C. The use of statins in pediatrics: knowledge base, limitations, and future directions. Pediatrics. 2007. February;119(2):370–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrick C, Bahrainy S, Gill EA. Statins and the Liver. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016. March;45(1):117–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avis HJ, Hutten BA, Gagné C, Langslet G, McCrindle BW, Wiegman A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin therapy for children with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010. March 16;55(11):1121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCrindle BW, Ose L, Marais AD. Efficacy and safety of atorvastatin in children and adolescents with familial hypercholesterolemia or severe hyperlipidemia: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2003. July;143(1):74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein E a. Efficacy and Safety of Lovastatin in Adolescent Males With Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1999. January 13;281(2):137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statins Chalasani N. and hepatotoxicity: Focus on patients with fatty liver. Hepatology. 2005. April;41(4):690–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vuorio A, Kuoppala J. Statins for children with familial hypercholesterolemia. … Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vos MB, Abrams SH, Barlow SE, Caprio S, Daniels SR, Kohli R, et al. NASPGHAN Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016. November 30;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. F itting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB & Christensen RHB Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models [R package lmerTest version 2.0–33] [Internet]. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN); [cited 2017 Mar 3]. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore THM, Burke M, Davey Smith G, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease Huffman MD, editor. Cochrane database Syst Rev. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013. January 31;(1):CD004816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Jongh S, Ose L, Szamosi T, Gagné C, Lambert M, Scott R, et al. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in children with familial hypercholesterolemia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with simvastatin. Circulation. 2002. October 22;106(17):2231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braamskamp MJAM, Langslet G, McCrindle BW, Cassiman D, Francis GA, Gagné C, et al. Efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin therapy in children and adolescents with familial hypercholesterolemia: Results from the CHARON study. J Clin Lipidol. 2015. November;9(6):741–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rzouq FS, Volk ML, Hatoum HH, Talluri SK, Mummadi RR, Sood GK. Hepatotoxicity Fears Contribute to Underutilization of Statin Medications by Primary Care Physicians. Am J Med Sci. 2010. August;340(2):89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bays H, Cohen DE, Chalasani N, Harrison SA, The National Lipid Association’s Statin Safety Task Force. An assessment by the Statin Liver Safety Task Force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 8(3 Suppl):S47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.