Abstract

Purpose:

Low-grade gliomas (LGG) are a heterogeneous group of brain tumors, which are often assumed to have a benign course. Yet, children diagnosed and treated for LGG in infancy are at increased risk for neurodevelopmental disruption. We sought to investigate neuropsychological outcomes of infants diagnosed with LGG.

Methods:

Between 1986 and 2013, 51 patients were diagnosed with LGG before 12 months of age and managed at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Twenty-five of the 51 patients received a cognitive assessment (68% male; 6.8 ± 3.3 months at diagnosis; 10.5 ± 4.8 years at latest assessment). Approximately half the patients received radiation therapy (n = 12; aged 4.0 ± 3.0 years at radiation therapy), with a median of 2 chemotherapy regimens (range = 0 – 5) and 1 tumor directed surgery (range = 0 – 5).

Results:

The analyses revealed performance below age expectations on measures of IQ, memory, reading, mathematics, and fine motor functioning as well as parent-report of attention, executive, and adaptive functioning. Following correction for multiple comparisons, a greater number of chemotherapy regimens was associated with lower scores on measures of IQ and mathematics. More tumor directed surgeries and presence of visual field loss were associated with poorer dominant hand fine motor control. Radiation therapy exposure was not associated with decline in neuropsychological performance.

Conclusions:

Children diagnosed with LGG in infancy experience substantial neuropsychological deficits. Treatment factors, including number of chemotherapy regimens and tumor directed surgeries, may increase risk for neurodevelopmental disruption and need to be considered in treatment planning.

Keywords: low-grade glioma, brain tumor, infancy, cancer, neuropsychological

Introduction

Low-grade gliomas (LGG) are a heterogeneous group of tumors comprising approximately 40% of central nervous system tumors in children [1]. These tumors are often assumed to have a benign course, and long term survival rates approach 80–90% [1, 2]. LGGs are most commonly found in the cerebellum, followed by cerebral and midline structures [3]. Treatment typically involves surgery [4]. However, recurrence or progression of disease is common, and certain tumor locations (e.g., hypothalamic tumors) preclude surgical cure [5]. Thus, treatment frequently requires chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy [6]. These disease and treatment related risk factors put children diagnosed with LGG at risk for neurocognitive deficits [7, 8].

Children with LGG treated with surgery alone demonstrate deficits in multiple neuropsychological domains including intellectual, academic, motor, and adaptive performance [9–11]. In a large prospective study of LGG survivors at our institution, medical factors including neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), shunt placement, epilepsy, and chemotherapy exposure were associated with lower IQ scores [12]. Additionally, children diagnosed and treated at a younger age had poorer neurocognitive outcomes [12].

Consistent within the pediatric brain tumor literature, diagnosis and treatment at a younger age places children at increased risk for neurobehavioral deficits [7, 13, 14]. This is in part due to the increased vulnerability to treatment effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in early childhood [15, 16]. These early insults do not result in a loss of skill, but slow skill acquisition that becomes increasingly discrepant as children develop [7, 13, 17]. In infancy, radiation therapy is often delayed or avoided to limit these late effects [18–20].

Thus, infants diagnosed with LGG are a unique group with increased risk for neurodevelopmental disruption and distinct treatment considerations. Previous researchers investigating neurocognitive outcomes of LGG have included infants in their samples, but no studies have thoroughly examined outcomes of this specific group. Considering the high survival rates and limited research regarding functional outcomes for this population, we sought to investigate neuropsychological outcomes of infants who were diagnosed with LGG. We predicted children diagnosed with LGG in infancy would be disproportionately impaired on measures of intellectual, academic, motor, executive, and adaptive domains. Further, we hypothesized that established risk factors for cognitive late effects, including radiation exposure, number of chemotherapy regimens, and number of surgical procedures would predict performance.

Methods

Participants

Between 1986 and 2013, 51 children diagnosed with LGG before 12 months of age were treated at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. LGG diagnoses included pilocytic astrocytoma, pilomyxoid astrocytoma, desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma, extraventricular neurocytoma, fibrillary astrocytoma, low grade glioma not otherwise specified, and low grade neuroepithelial tumor not otherwise specified. Tumor location, extent of resection, and treatment for this retrospective cohort were abstracted from the medical record. This analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Among the 51 children diagnosed with LGG before 12 months of age, 25 (49%) received a cognitive assessment as part of protocol-based monitoring (n = 5) or clinical care (n = 20). Assessments that were part of a treatment protocol were administered at specific time intervals during and following the course of treatment. Clinically referred assessments were based on the concerns of the medical team at any given time during and following treatment. For individuals with multiple assessments, the most recent assessment with measurement of intellectual functioning (IQ) was utilized to best characterize long-term cognitive outcomes. Due to the wide range of assessment measures and the time span of our review, we combined measures assessing the same cognitive construct to form the following domains: intellectual functioning, academic achievement, verbal memory, fine motor control, social-emotional functioning, attention, and executive functioning. All reported measures have large, representative normative standardization samples with demonstrated reliability and validity.

Intellectual functioning was obtained primarily from age-appropriate Wechsler measures as well as the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test and Differential Ability Scales – Second Edition [21–28]. Assessment of academic achievement included word reading and math reasoning subtests from Wechsler, Woodcock Johnson, and Wide Range Achievement measures [29–32]. Verbal memory was measured using age-appropriate versions of the California Verbal Learning Test [33, 34]. To measure fine motor control and speed, the Purdue Pegboard or Grooved Pegboard was used [35, 36]. Parent report of executive functioning was captured with the age appropriate Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) in the areas of working memory, behavioral regulation, metacognition, and global executive function [37]. Adaptive functioning was assessed by parent ratings on either the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) or the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS) [38–40].

Social-emotional functioning was assessed by parent report of internalizing (e.g., anxiety or depression) and externalizing behaviors (e.g., conduct problems or oppositional behaviors) on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) or Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) [41, 42]. Attentional problems were measured by parent report on the CBCL, BASC, or Conners Rating Scales [41–44].

Sensorineural hearing loss was assessed using the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) grading scale [45]. This scale is based on sensorineural hearing thresholds in dB hearing level (HL). The following grades were utilized: Grade 0 = ≤ 20 dB HL at all frequencies, Grade 1 = > 20 dB HL above 4,000 Hz, Grade 2 = > 20 dB HL at 4,000 Hz and above, Grade 3 = > 20 dB HL at 2,000 or 3,000 Hz and above, Grade 4 = > 40 dB HL at 2,000 Hz and above.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics of demographic and clinical variables were calculated to characterize the sample. Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare demographic and clinical variables for those with and without cognitive data, and to compare data for those that received a clinical referral for cognitive assessment and those that completed a standard assessment according to a treatment protocol. Binomial tests were used to compare performance of our sample to what is expected in the normative population, where 16% would be expected to fall one standard deviation below the average range. Potential demographic and clinical contributors were individually added to linear mixed effects models to investigate their effect on neuropsychological performance. To account for multiple comparisons among demographic and clinical factors (11 predictors) within each neuropsychological measure, a Dunn–Šidák correction was used.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1. Among the 25 patients with cognitive assessments, 68% were male. The median age at diagnosis was 6.2 months (range = 0.2 – 11.8). Of the 25 children, 12 received radiation therapy prior to assessment (48.0%), which predominately involved focal radiation (n=11) rather than craniospinal irradiation (n=1). The median age at the time of radiation therapy was 3.1 years (range = 1.2 – 12.7). The median number of chemotherapy regimens and tumor directed surgeries was 2 and 1, respectively (range = 0 – 5). Based on the SIOP grading scale [45], 16.0% of children had sensorineural hearing loss (≥ SIOP Grade 1), these included single cases with grade 1, grade 2, grade 3, and grade 4 hearing loss, respectively. At the time of their most recent cognitive assessment, a median of 9.7 years (range = 1.0 – 17.6) had passed since diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 17 | 68.0 |

| Female | 8 | 32.0 |

| Neurofibromatosis Type 1 | ||

| No | 20 | 80.0 |

| Yes | 5 | 20.0 |

| Tumor location | ||

| Supratentorial | 21 | 84.0 |

| Infratentorial | 4 | 16.0 |

| First mode of treatmenta | ||

| Observation | 8 | 32.0 |

| Treatment | 17 | 68.0 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid diversion | ||

| No | 11 | 44.0 |

| Yes | 14 | 56.0 |

| Radiation therapyb | ||

| No | 13 | 52.0 |

| Yes | 12 | 48.0 |

| Recent SIOP for best earc | ||

| 0 | 19 | 76.0 |

| ≥ 1 | 4 | 16.0 |

| Not specified | 2 | 8.0 |

| Reduced visual acuity | ||

| No | 9 | 36.0 |

| Yes | 16 | 64.0 |

| Constricted visual fields | ||

| No | 12 | 48.0 |

| Yes | 9 | 36.0 |

| Not specified | 4 | 16.0 |

| Median | Range | |

| Age at diagnosis (months) | 6.2 | 0.2 – 11.8 |

| Age at first treatment (months) | 11.4 | 3.5 – 51.4 |

| Age at radiation therapy (years) | 3.1 | 1.2 – 12.7 |

| Number of chemotherapy regimens | 2.0 | 0 – 5 |

| Number of tumor directed surgeries | 1.0 | 0 – 5 |

| Age at cognitive assessment (years) | 9.9 | 1.9 – 17.9 |

| Years from diagnosis to assessment | 9.7 | 1.0 – 17.6 |

First mode of treatment included chemotherapy (n=8), radiation therapy (n=1), surgery (n=6), and surgery with additional chemotherapy (n=2)

11 patients with focal radiation and 1 with craniospinal radiation prior to cognitive assessment

Society of Pediatric Oncology ototoxicity grading scale; grade 1 (n=1), grade 2 (n=1), grade 3 (n=1), grade 4 (n=1)

There was no difference in gender, age at diagnosis, NF1 status, tumor location, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion, radiation therapy exposure, radiation therapy approach (focal vs. craniospinal), number of chemotherapy regimens, number of tumor directed surgeries, sensorineural hearing loss, visual acuity, or constricted visual fields between participants with and without cognitive assessments (p > 0.05). However, the group with cognitive assessments was more likely to initially be observed rather than treated (p = 0.039) and was older at first treatment (p = .003) compared to the group without cognitive assessments.

Examination of group differences between participants receiving protocol based-cognitive monitoring and those clinically referred for cognitive assessment revealed no differences in gender, NF1 status, age at diagnosis, tumor location, age at first treatment, first mode of treatment, CSF diversion, radiation therapy approach (focal vs. craniospinal), number of chemotherapy regimens, number of tumor directed surgeries, sensorineural hearing loss, or visual acuity (p > 0.05). Participants who were clinically referred were less likely to receive radiation therapy (p = 0.039) and had lower incidence of visual field loss (p = 0.021). Furthermore, children who were clinically referred had a shorter duration between diagnosis and most recent assessment (p = 0.021) and were younger at the time of assessment (p = 0.021).

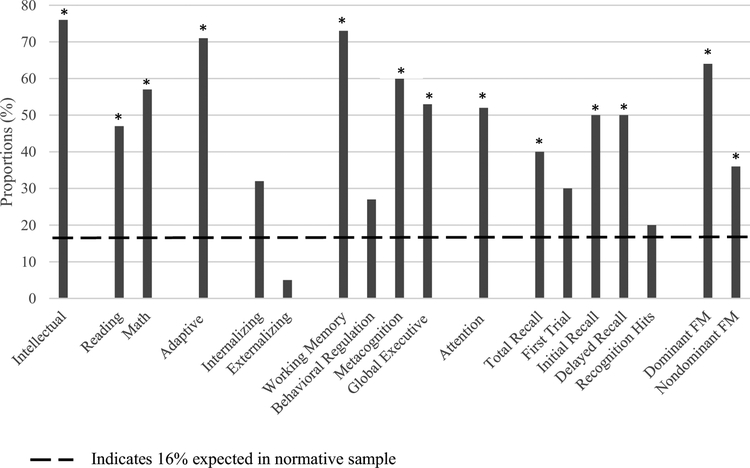

Neuropsychological performance compared to normative expectations

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for all neuropsychological measures at the most recent assessment. Figure 1 displays the proportion of scores that differed (p<0.05) from age expectations (≥ 1 SD from normative mean) across neuropsychological domains. A significantly larger proportion of participants fell below the average range on measures of intellectual (76.0%, p < 0.001) and adaptive functioning (71.0%, p < 0.001) than would be expected in the population. Consistently, 47.0% of children fell below the average range on measures of reading (p < 0.001) and 57.0% were below expectations in mathematics (p < 0.001). Children also performed disproportionately worse than expected (40.0%) on a verbal learning task assessing their total recall across trials (p = 0.038). Performance on the initial recall and delayed recall components of this task were also disproportionately below average (p = 0.003 and 0.003, respectively). However, performance on the first trial and recognition hits were within expectations (p = 0.227 and 0.730, respectively). The proportion of scores below average on measures of fine motor control were greater than expected for both dominant (p < 0.001) and nondominant (p < 0.001) hands.

Table 2.

Neuropsychological outcomes at most recent assessment

| Neuropsychological Measure | n | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual Functioning (IQ)a | 21 | 75.5 ± 20.6 |

| Academic Achievementa | ||

| Reading | 17 | 79.8 ± 26.5 |

| Math | 14 | 72.9 ± 26.3 |

| Overall Adaptive Functioninga | 17 | 71.3 ± 23.6 |

| Executive Functioningb | ||

| Working Memory | 15 | 68.1 ± 14.2 |

| Behavioral Regulation | 15 | 55.9 ± 9.0 |

| Metacognition | 15 | 64.4 ± 11.5 |

| Global Executive Function | 15 | 61.9 ± 10.2 |

| Attention Problemsb | 21 | 61.6 ± 11.4 |

| Memoryc | ||

| Total Recall | 10 | 44.0 ± 15.2 |

| First Trial | 10 | −0.5 ± 1.4 |

| Initial Recall | 10 | −1.1 ± 1.7 |

| Delayed Recall | 10 | −1.1 ± 1.8 |

| Recognition Hits | 10 | −0.5 ± 1.5 |

| Fine Motord | ||

| Dominant Hand | 11 | −3.9 ± 5.1 |

| Non-dominant Hand | 8 | −2.5 ± 2.5 |

| Social-Emotional Functioningb | ||

| Internalizing Behaviors | 19 | 54.3 ± 10.3 |

| Externalizing Behaviors | 19 | 49.1 ± 7.1 |

Standard scores with a mean of 100 and SD of 15

T-scores with a mean of 50 and SD of 10

Total Recall is a T-score with a mean of 50 and SD of 10. First Trial, Initial Recall, Delayed Recall, and Recognition Hits are Z-scores with a mean of 0 and SD of 1

Z-scores with a mean of 0 and SD of 1

A higher score indicates better performance on measures of intellectual functioning, academic achievement, adaptive functioning, memory, and fine motor control but greater parental concerns for measures of executive and social-emotional functioning

Fig. 1.

Proportions of scores outside average range. *Proportion of scores significantly different (1SD) than expected 16% in normative population based on chi square test (p < 0.05). FM Fine Motor

Parent report of executive difficulties revealed significant problems (≥1SD above the normative mean) involving working memory (73.0%), metacognition (60.0%), and global executive functioning (53.0%) domains (all p < 0.001). Clinically significant attention problems were also disproportionately reported (52.0%) in the sample (p < 0.001).

Risk Factors

We explored associations between clinical risk factors and performance on measures that were disproportionately discrepant from age expectations. Female gender was associated with greater parent-reported difficulties in global executive functioning (p = 0.050). Children who were older at diagnosis displayed improved performance on a measure of initial recall of verbal information (p = 0.015). Children with supratentorial tumors had lower IQ scores (p = 0.032) and were rated by their parents as having greater adaptive skill deficits (p = 0.048) compared to children with infratentorial tumors. Greater number of chemotherapy regimens was associated with lower scores on measures of IQ (p = 0.004), reading (p = 0.005), mathematics (p < 0.001), and adaptive functioning (p = 0.014). Additionally, more tumor directed surgeries was associated with poorer performance on measures of mathematics (p = 0.022) and dominant hand fine motor control (p = 0.001). Exposure to radiation therapy was associated with greater attention problems based on parent report (p = 0.030). Visual field constriction was related to poorer performanceon dominant hand fine motor control (p = 0.001) but reduced attentional difficulties (p = 0.024). Increased duration from diagnosis to assessment was associated with fewer parent-reported attention problems (p = 0.024). Effects for NF1 status, CSF diversion, and sensorineural hearing loss were explored with no significant findings (p > 0.05).

To account for multiple comparisons (11 predictors) within each neuropsychological measure, a more conservative significance cutoff was used (Dunn–Šidák correction; p < 0.0047). Using this more stringent cutoff, only the effects of number of chemotherapy regimens, number of tumor directed surgeries, and visual field constriction remained.

Discussion

Overall, results were consistent with a priori hypotheses. The proportion of children falling one standard deviation outside the average range (indicative of worse performance) was significantly higher across most neuropsychological domains than the percentage expected in a sample of healthy peers. Further, neuropsychological performance was influenced by treatment and clinical risk factors extant in the brain tumor literature.

Although previous studies have demonstrated neurocognitive deficits associated with LGG diagnosed in childhood, their samples were still broadly within the average range intellectually [10–12, 14]. In contrast, our sample of infants diagnosed and treated for LGG approached criteria for an intellectual disability (Mean IQ = 75.5, Mean Adaptive Functioning = 71.3), with over 70% of survivors falling outside the average range. Additional deficits in academic achievement, verbal memory, executive functioning, and fine motor control were apparent. Notably, fine motor control was an area of significant difficulty for this group, with children performing over 2 standard deviations below normative expectations. This study adds to the existing literature by revealing children diagnosed in infancy have neurocognitive morbidities that are as prominent as those typically seen in higher grade tumors, a novel finding compared to children diagnosed with LGG at older ages.

Predictors of neuropsychological performance were broadly within expectations. Survivors with a greater number of chemotherapy regimens displayed greater deficits in intellectual and academic functioning. This finding is consistent with a large retrospective study from our institution, which found that chemotherapy exposure significantly predicted intellectual outcomes of pediatric LGG survivors [12]. Additionally, infants with a greater number of tumor directed surgeries displayed poorer dominant hand fine motor functioning. Children with LGGs undergoing surgery alone display visual-motor deficits [9, 46], and previous studies have demonstrated that the number and extent of surgical resections are associated with neurocognitive performance [47, 48]. Subsequent surgeries likely infer increased risk of complications and brain injury. As might be expected, visual field loss was related to poorer fine motor control, likely due to the visual demands of the pegboard task.

Radiation therapy impacted parent-reported attention problems, but this association did not persist after correction for multiple comparisons. The deleterious effects of radiation exposure on neurobehavioral functioning in children have been well documented [7, 13]. However, these findings are largely based on studies of children treated with craniospinal or whole brain irradiation [14]. Cognitive late effects following focal radiation are less conclusive, and several studies of children treated for LGGs have found limited impact of radiation therapy on neurocognitive outcomes [12, 46]. It is likely that extent of cognitive late effects resulting from radiation therapy is limited in many of these cases due to the neurocognitive hits these children have previously received resulting from multiple surgeries and chemotherapy regimens. Such interventions preceding radiation therapy may leave less room for decline. The younger age at diagnosis and treatment potentially served as a protective factor against the effects of radiation therapy. Although younger age is predominately associated with poorer neuropsychological outcomes in the pediatric oncology literature, young age, and the associated brain plasticity may benefit children with more focal injuries [49]. A prospective longitudinal study of pediatric LGG survivors found that the volume of irradiated brain accounted for a significant amount of variance in neurocognitive functioning, with greater irradiated brain volume associated with poorer outcomes [48]. Notably, all but one patient in our series received focal rather than craniospinal irradiation.

The group of children that received cognitive assessments appeared representative of the larger sample across most clinical features. However, the group that was assessed was more likely to initially be observed and was older at first treatment. Based on our analyses, these factors appeared to have minimal influence on cognitive outcomes. Among the group that was assessed, our sample consisted of substantially more children that were clinically referred (n=20) rather than receiving protocol testing (n=5). This referral bias may have skewed our sample to have greater deficits than might be typically seen in this group. However, those with protocol testing were similar across most clinical features to those with clinical testing, with a few exceptions. Children who were clinically referred were less likely to receive radiation therapy. This might be because those with radiation therapy are more likely to have neuropsychological monitoring built into their treatment/research protocol. Furthermore, children who were clinically referred were younger at their most recent assessment, due to the fact that children on protocol had a greater number of assessments and were more closely followed. Children with visual field loss were surprisingly under-represented in the clinical referral group, potentially due to concerns from referral sources that they would be too difficult to assess cognitively.

Many study limitations exist. The analyses were conducted with a small sample, and some neuropsychological domains were represented with partial data. Inherent retrospective limitations include the length of the time covered to capture patients and evaluate change over time as well as the variety of measures utilized across evaluations. Notably, the broad age range at time of radiation therapy limits the conclusions that can be drawn regarding differential susceptibility or protective factors related to age. There was also a wide age range at time of assessment, spanning over 16 years, which leads to great amount of variability in specific cognitive constructs. Future studies would benefit from having a more homogeneous group. Furthermore, we could not assess the effect of the tumor in comparison to treatment. Future studies should utilize longitudinal designs to identify risk factors and specific areas of cognitive decline. Our measures may have lacked the sensitivity to detect late effects from radiation therapy, which are shown to differentially impact attention, processing speed, and executive skills [7]. In particular, we relied on parent report of executive functions and attention, which are known to poorly correlate with performance measures of similar constructs [50]. Although parent report has subjective biases, performance measures of executive functions tend to lack ecological validity given the controlled one-on-one testing setting. To thoroughly evaluate these deficits, future studies would benefit from sensitive measures of speeded processing, attention, and working memory. Additionally, assessment of more distal functional outcomes such as quality of life and achievement of milestones including college graduation, employment, and independent living would help to further understand the functional outcomes for this group [46].

Infants diagnosed with LGG are a vulnerable yet understudied group. Our findings indicate that this group is at substantial risk for neurocognitive deficits, comparable to those seen in higher grade tumors such as medulloblastoma. The need for neurocognitive monitoring and identification of ways to increase quality of life is particularly important for these children.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported, in part, by the National Cancer Institute (St. Jude Cancer Center Support [CORE] Grant [P30-CA21765] and Pediatric Oncology Education Program Grant [R25CA23944]) and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Portions of this paper have been submitted for potential presentation at the 2019 annual meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society in New York, NY.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Due to the retrospective nature of this study, a waiver of consent was approved by the institutional IRB.

References

- 1.Pollack IF (1999) The Role of Surgery in Pediatric Gliomas. J Neurooncol 42:271–288. 10.1023/A:1006107227856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandopadhayay P, Bergthold G, London WB, et al. (2014) Long-term outcome of 4,040 children diagnosed with pediatric low-grade gliomas: An analysis of the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. Pediatr Blood Cancer 61:1173–1179. 10.1002/pbc.24958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman CR, Farmer J-P, Montes J (1998) Low-grade astrocytomas in children: evolving management strategies. Int J Radiat Oncol 41:979–987. 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00163-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher PG, Tihan T, Goldthwaite PT, et al. (2008) Outcome analysis of childhood low-grade astrocytomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51:245–250. 10.1002/pbc.21563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sievert AJ, Fisher MJ (2009) Pediatric Low-Grade Gliomas. J Child Neurol 24:1397–1408. 10.1177/0883073809342005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmandt SM, Packer RJ (2000) Treatment of low-grade pediatric gliomas. Curr Opin Oncol 12:194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulhern RK, Merchant TE, Gajjar A, et al. (2004) Late neurocognitive sequelae in survivors of brain tumours in childhood. Lancet Oncol 5:399–408. 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01507-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffner PK (2010) Risk factors for cognitive decline in children treated for brain tumors. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 14:106–115. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ris MD, Beebe DW, Armstrong FD, et al. (2008) Cognitive and Adaptive Outcome in Extracerebellar Low-Grade Brain Tumors in Children: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 26:4765–4770. 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner CD, Chordas CA, Liptak CC, et al. (2009) Medical, psychological, cognitive and educational late-effects in pediatric low-grade glioma survivors treated with surgery only. Pediatr Blood Cancer 53:417–423. 10.1002/pbc.22081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beebe DW, Ris MD, Armstrong FD, et al. (2005) Cognitive and Adaptive Outcome in Low-Grade Pediatric Cerebellar Astrocytomas: Evidence of Diminished Cognitive and Adaptive Functioning in National Collaborative Research Studies (CCG 9891/POG 9130). J Clin Oncol 23:5198–5204. 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong GT, Conklin HM, Huang S, et al. (2011) Survival and long-term health and cognitive outcomes after low-grade glioma. Neuro-Oncol 13:223–234. 10.1093/neuonc/noq178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ris MD, Noll RB (1994) Long-term neurobehavioral outcome in pediatric brain-tumor patients: Review and methodological critique. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 16:21–42. 10.1080/01688639408402615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ris MD, Beebe DW (2008) Neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with low-gradegliomas. Dev Disabil Res Rev 14:196–202. 10.1002/ddrr.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore BD (2005) Neurocognitive Outcomes in Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J Pediatr Psychol 30:51–63. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddick WE, Glass JO, Palmer SL, et al. (2005) Atypical white matter volume development in children following craniospinal irradiation. Neuro-Oncol 7:12–19. 10.1215/S1152851704000079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer SL (2008) Neurodevelopmental impact on children treated for medulloblastoma: a review and proposed conceptual model. Dev Disabil Res Rev 14:203–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffner PK, Krischer JP, Sanford RA, et al. (1998) Prognostic Factors in Infants and Very Young Children with Intracranial Ependymomas. Pediatr Neurosurg 28:215–222. 10.1159/000028654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffner PK, Horowitz ME, Krischer JP, et al. (1993) Postoperative Chemotherapy and Delayed Radiation in Children Less Than Three Years of Age with Malignant Brain Tumors. N Engl J Med 328:1725–1731. 10.1056/NEJM199306173282401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geyer JR, Sposto R, Jennings M, et al. (2005) Multiagent Chemotherapy and Deferred Radiotherapy in Infants With Malignant Brain Tumors: A Report From the Children’s Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol 23:7621–7631. 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wechsler D, Coalson D, Raiford S (2012) Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence - Fourth Edition (WPPSI-IV). The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wechsler D (2002) Wechsler Primary and Preschool Scale of Intelligence –Third edition (WPPSI-III). Harcourt Assessment, San Antonio, Texas [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wechsler D (1991) Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler D (2003) Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler D (2014) Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Fifth Edition (WISC-V). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler D (2014) Wechsler adult intelligence scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS–IV). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliott CD (2007) Differential Ability Scales, 2nd edition. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman A, Kaufman N (1990) K-BIT: Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test. American Guidance Service, Circle Pines, MN [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wechsler D (1992) Wechsler Individual Achievement Test (WIAT). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler D (2001) Wechsler Individual Achievement Test - 2nd Edition (WIAT-II). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodcock R, McGrew K, Mather N (2001) Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement. Riverside Publishing, Itasca, IL [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jastak JF, Jastak SR (1978) WRAT: Wide Range Achievement Test. Jastak Associates [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA (2000) California Verbal Learning Test, second edition (CVLT-II). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA (1994) California Verbal Learning Test, Children’s Version. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiffin J (1968) Purdue Pegboard Examiner Manual. Science Research Associates, Chicago, IL [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kløve H (1963) Grooved Pegboard Test. Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L (2000) Behavior rating inventory of executive function: BRIEF. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sparrow S, Balla D, Cicchetti D (1984) Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. American Guidance Service, Circle Pines, MN [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sparrow S, Cicchetti D, Balla D (2005) Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales - 2nd Edition. American Guidance Service, Circle Pines, MN [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrison P, Oakland T (2003) Adaptive Behavior Assessment System second edition: Manual. Harcourt Assessment, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 41.Achenbach T (1991) The Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist 4–18, 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, Burlington, VT [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamphaus RW, Reynolds CR (2007) BASC-2 Behavioral and Emotional Screening System Manual. Pearson, Circle Pines, MN [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conners C (2001) Conners’ Rating Scales–Revised. Multi-Health Systemics Inc., North Tonawanda, NY [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conners CK (2008) Conners 3rd edition: Manual. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, Ontario, Canada [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brock PR, Knight KR, Freyer DR, et al. (2012) Platinum-Induced Ototoxicity in Children: A Consensus Review on Mechanisms, Predisposition, and Protection, Including a New International Society of Pediatric Oncology Boston Ototoxicity Scale. J Clin Oncol 30:2408–2417. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark KN, Ashford JM, Pai Panandiker AS, et al. (2016) Cognitive Outcomes among Survivors of Focal Low-Grade Brainstem Tumors Diagnosed in Childhood. J Neurooncol 129:311–317. 10.1007/s11060-016-2176-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Netson KL, Conklin HM, Wu S, et al. (2012) A 5-Year Investigation of Children’s Adaptive Functioning Following Conformal Radiation Therapy for Localized Ependymoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 84:217–223.e1. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.10.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merchant TE, Conklin HM, Wu S, et al. (2009) Late Effects of Conformal Radiation Therapy for Pediatric Patients With Low-Grade Glioma: Prospective Evaluation of Cognitive, Endocrine, and Hearing Deficits. J Clin Oncol 27:3691–3697. 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.2738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bates E, Reilly J, Wulfeck B, et al. (2001) Differential effects of unilateral lesions on language production in children and adults. Brain Lang 79:223–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toplak ME, West RF, Stanovich KE (2013) Practitioner Review: Do performance-based measures and ratings of executive function assess the same construct? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 54:131–143. 10.1111/jcpp.12001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]