Abstract

Although the study of reactive attachment disorder (RAD) in early childhood has received considerable attention, there is emerging interest in RAD that presents in school age children and adolescents. We examined the course of RAD signs from early childhood to early adolescence using both variable-centered (linear mixed modeling) and person-centered (growth mixture modeling) approaches. One-hundred twenty-four children with a history of institutional care from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, a randomized controlled trial of foster care as an alternative to institutional care, as well as 69 community comparison children were included in the study. While foster care was associated with steep reductions in RAD signs across development, person-centered approaches indicated that later age of placement into families and greater percent time in institutional care were each associated with prolonged elevated RAD signs. Findings suggest the course of RAD is variable but substantially influenced by early experiences.

Keywords: Reactive attachment disorder, institutional care, deprivation, variable-centered analyses, person-centered analyses

Descriptive accounts of socially aberrant behaviors in young children raised in institutions appeared in the mid-20th century (Goldfarb, 1945; Levy, 1947; Provence & Lipton, 1962). One pattern involved children who were withdrawn, with limited social reciprocity, poor emotional regulation, and a paucity of positive affect (Tizard & Rees, 1974). These patterns came to comprise a disorder known as reactive attachment disorder (RAD). Although RAD originally appeared in DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980), the definition of the disorder has been refined over time, more recently focusing on the absence of attachment behaviors in children who have had limited opportunities to form them (DSM-5 [American Psychiatric Association, 2013]; DC:0–5 [ZERO TO THREE, 2016]). Also, accumulating evidence has clarified that socioemotional neglect seems to be a necessary but not sufficient predisposing factor for RAD to develop (Zeanah & Gleason, 2015).

Absent and aberrant attachment behaviors in children characterize the disorder, and the majority of theoretical and empirical work has focused on the disorder in early childhood (see Zeanah & Gleason, 2015). How, and even if, the disorder manifests in middle childhood and adolescence is less well established. Attachment becomes increasingly internalized with fewer behavioral referents after early childhood, and there is no gold standard assessment method for patterns of attachment after the preschool years. For example, Kerns et al. (2005) reported on 9 different methods of assessing attachment in middle childhood, and several more exist. Still, there have been few attempts to assess convergent validity of these approaches and in middle childhood and early adolescence, there is no gold standard approach.

In early childhood, it is clear that patterns of attachment do not map directly onto attachment disorders, although RAD appears to correspond most closely to a pattern termed, “unclassifiable” (Zeanah, Smyke, Koga, & Carlson, 2005). Developmental patterns of attachment in early and middle childhood and in adolescence define qualitative differences in how a child regulates and expresses needs for comfort and closeness and emotions associated with these needs (Kerns & Richardson, 2005). In contrast, RAD describes a condition characterized by absent or extremely limited attachment behaviors. Therefore, it is not surprising that it is challenging to identify an attachment disorder when we lack a consensus about even how best to assess patterns of attachment in middle childhood and early adolescence.

Nevertheless, an increasing number of publications about RAD in middle childhood and adolescence have appeared recently (Humphreys, Nelson, Fox, & Zeanah, 2017; Pritchett, Rochat, Tomlinson, & Minnis, 2013; Raaska et al., 2012; Split, Vervoort, Koenen, Bosmans, & Verschueren, 2016; Vervoort, De Schipper, Bosmans, & Verschueren, 2013). Though there is concern about overdiagnosis of the disorder in clinical settings, especially in older children (Chaffin et al., 2006; Woolgar & Scott, 2013; Zeanah et al., 2016), these more recent empirical studies of RAD have used multiple standardized methods, including parent report questionnaires, structured psychiatric interviews, and behavioral observations to identify RAD. Still, much less is known about the behavioral phenotype in middle childhood and adolescence, and in particular, how it relates to the early childhood phenotype. Longitudinal perspectives from early childhood to adolescence can be especially valuable to address these questions.

Longitudinal approaches allow for the examination of both stability and change in RAD. Characterizing change using formal modeling techniques is available using different statistical approaches, each with advantages and disadvantages. Variable-centered approaches (e.g., linear mixed modeling [LMM]) identify across-sample, fixed group trends examining mean change and relationships between variables for an entire sample or pre-identified groups within a sample (Bergman & Magnusson, 1997). In other words, variable-centered approaches assume that all participants in a given sample or group are drawn from a single population, and therefore, change in similar and predictable ways over time. In contrast, person-centered analyses allow for nuanced and sophisticated examination of individual differences outside of predetermined groups of interest. Latent profile analysis and other growth mixture modeling (GMM) procedures, examine the presence of meaningful subgroups defined by unique profiles or trajectories within a sample (Muthén & Muthén, 2000).

Despite the advantages of person-centered techniques in examining individual differences, a combination of both variable-centered and person-centered techniques offers the most comprehensive analysis of the longitudinal course of signs of RAD. First, we examine the course of RAD signs using a variable-centered approach, which allows demonstration of causal effects of the intervention on randomized groups. The variable-centered analyses provide a context within which to review and critique findings from person-centered analyses. Second, we use a person-centered approach to provide information about variability in RAD signs over time unconstrained by pre-identified groups of interest. A person-centered analysis such as growth mixture modeling is inherently exploratory, and therefore, susceptible to misinterpretation and over-extension (Grimm, Ram, & Estabrook, 2016). Therefore, we examine the course of signs of RAD using both variable- and person-centered techniques to provide a more complete understanding of the course of RAD.

We examined data from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), the only randomized controlled trial (RCT) of foster care as an alternative to institutional care. This study allows us to examine signs of RAD from early childhood to early adolescence in a sample of children exposed to severe, early deprivation, along with comparison children who were never institutionalized (Zeanah et al., 2003). The study is uniquely positioned to contribute to our understanding of RAD because it involves a high-risk group, drawn from an RCT, who were followed longitudinally for more than a decade.

Previously, we have shown that signs of RAD are more prevalent among young children raised in institutions than in never institutionalized children (Zeanah et al., 2005). Further, we have shown that removal from institutions and placement in foster care leads to reductions in signs of RAD at various points in early and middle childhood (Smyke et al., 2012) and in early adolescence (Humphreys et al., 2017). What is not clear from previous analyses, however, is group-level as well as individual-level patterns of change, or the variables associated with different patterns of RAD signs across time. This is our aim in the present study.

Based on previous findings about RAD in the BEIP (Humphreys et al., 2017; Smyke et al., 2012), we predict a convergence in the variable-centered and person-centered analyses, indicating no signs of RAD over time in children who did not experience early deprivation, rapid decline in signs of RAD among children removed from institutions and placed in foster care, and a slow, but more modest, decline in signs of RAD in children with exposure to more sustained institutionalization. Given that person-centered analyses are exploratory in nature and assume latent heterogeneity in patterns over time, it is possible that additional profiles will emerge that could not be predicted a priori. We predict that the person-centered analyses will demonstrate that persistent signs of RAD will be associated with longer time spent in institutional care and a later age of placement into families.

Method

Participants

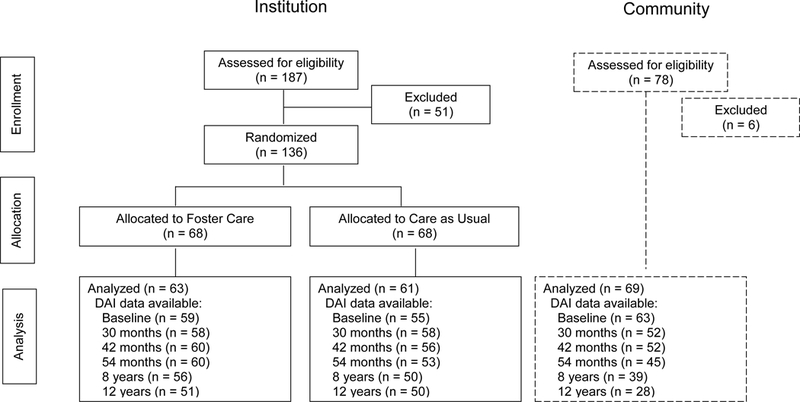

The participants in this investigation were 193 children with usable data who were participants in the BEIP and community comparison children. The original sample consisted of 136 infants and toddlers, all of whom were recruited from institutions in Bucharest and were randomized after a baseline assessment (M age = 22.49 months, SD = 5.63) into either a care as usual group (CAUG; n = 68) or a foster care group (FCG; n = 68) (Zeanah et al., 2003). In addition to a baseline assessment, participants were assessed at age 30, 42, and 54 months, at which time the formal intervention ended, and oversight of the foster care network was transferred to local governmental control. Follow-up assessments were conducted at age 8 and 12 years. At baseline, an additional group of community comparison children who had never been institutionalized were also recruited and these comprise the never institutionalized group (NIG; n = 72). Across the six waves of data collection, participation varied (see Figure 1). Details about the original sample are available elsewhere (Nelson, Fox, & Zeanah, 2014).

Figure 1:

CONSORT figure

Protocols were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the three principal investigators (CHZ, NAF, CAN), and by the local Commissions on Child Protection in Bucharest. The study was launched in April 2001 in collaboration with the Institute of Maternal and Child Health of the Romanian Ministry of Health. All assessments at the 8- and 12-year follow-ups were reviewed by a standing data safety monitoring board in Bucharest and the 12- year follow-up by an Ethics Committee at Bucharest University. Consent to participate was obtained from each child’s legal guardian as required by Romanian law. Assent for each procedure was obtained from the children at age 8 and 12 years. Ethical considerations of the study have been discussed previously in some detail by us and by others (Miller, 2009; Millum & Emanuel, 2007; Nelson, Fox & Zeanah, 2014; Rid, 2012; Zeanah, Fox, & Nelson, 2012).

Procedure

Following baseline assessment, children were randomly assigned to the CAUG or FCG. The children in the two groups were indistinguishable on demographic and caregiving features (Smyke et al., 2007). All decisions about placements following randomization were made by child protection authorities in Romania, and analyses were based on original RCT placement (i.e., using an intent-to-treat [ITT] design).

Measures

Disturbances of Attachment Interview.

This measure is a semi-structured interview of caregivers about signs of disordered attachment that has been extensively used and validated at younger ages with construct validity (Gleason et al., 2011; Smyke, Dumitrescu, & Zeanah, 2002; Zeanah et al., 2004, 2005), criterion validity (Gleason et al., 2011), convergent validity (Zeanah et al., 2005), discriminant validity (Gleason et al., 2011), and predictive validity (Gleason et al., 2011; Smyke et al., 2012). The Disturbances of Attachment Interview was translated into Romanian, back-translated into English, and assessed for meaning at each step by bilingual research staff. For children living with biological parents or foster parents, the mother reported on the child’s behavior. For children living in institutions, an institutional caregiver who worked with the child regularly and knew the child well reported on the child’s behavior. Caregivers were asked a series of questions about their child’s attachment behavior, and coders rated the level of behavioral disturbance. Although additional items were added for older children, the inhibited social behavior scale that was comparable across all ages comprised 5 items (see the appendix; Supplemental Table 1 for the items and descriptive across each wave of assessment). The range for possible scores on the inhibited social behavior scale was 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more signs of reactive attachment disorder. Table 1 provides a correlation matrix for RAD signs, descriptive statistics, and internal consistency across all waves.

Table 1:

Correlation Matrix and Descriptive Statistics for Reactive Attachment Disorder Signs in by Assessment Wave

| Baseline (n=177) | 30 months (n=168) | 42 months (n=168) | 54 months (n=158) | 8 years (n=145) | 12 years (n=129) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 | |||||

| 30 months | .29*** | 1 | ||||

| 42 months | .22** | .47*** | 1 | |||

| 54 months | .26** | .27*** | .57*** | 1 | ||

| 8 years | .27** | .36*** | .48*** | .47*** | 1 | |

| 12 years | .17 | .23* | .59*** | .53*** | .52*** | 1 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.59 (2.11) | 0.94 (1.70) | 0.72 (1.46) | 0.65 (1.55) | 0.60 (1.59) | 0.90 (2.02) |

| Range | 0–10 | 0–8 | 0–9 | 0–10 | 0–9 | 0–10 |

| Cronbach’s α | .74 | .73 | .67 | .80 | .85 | .88 |

Note. Ns vary based on assessment wave.

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children.

We administered the computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, 4th edition (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000) to each caregiver to ascertain DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association & Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria for other domains of psychopathology (see Humphreys, Gleason, et al., 2015) within the past year at the 12 year assessment. The DISC was translated into Romanian, back-translated into English, and assessed for meaning at each step by bilingual research staff, and administered to the child’s caregiver. For this investigation, we examined total internalizing, externalizing, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms.

Intervention

The BEIP team recruited and trained 56 foster parents to care for 68 children (Smyke, Zeanah, Fox, & Nelson, 2009; Zeanah et al., 2003). The foster parents were supported by social workers in Bucharest who received regular consultation from clinicians in the U.S. Parents were explicitly encouraged to care for their foster children as if they were their own children and to make full and lasting commitments to them.

Data Analysis

Two approaches were used to examine signs of RAD longitudinally. The first approach used a variable-centered method to examine the effect of group assignment and institutional care history on trajectories of RAD signs. We used LMM, which accounts for the non-independence of repeated measures within individuals, and handles data from participants with differing numbers of observations and intervals between assessment waves. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation in Mixed Models in SPSS (version 23) was used. Degrees of freedom were calculated using the Satterthwaite method, which produces fractional estimates. In order to examine developmental changes in RAD signs, we tested linear, quadratic, and cubic terms for child age in months (i.e., age, age-squared, and age-cubed) as well as age by group interactions. Fixed slope and random intercept terms were included. Given that greater changes were observed earlier in development, a square root transformation was applied to the age values after subtracting a constant from each value so that the earliest age was represented by a value of 1. Figures are presented using the actual age represented by the transformed age variables.

The second approach was a person-centered approach, using GMM, which allows for the identification of latent (i.e., previously unidentified) subgroups within the larger sample that have similar growth trajectories across assessment waves (Grimm et al., 2016). Cases are classified into trajectories, sometimes referred to as classes or profiles, based on probabilities of membership to each identified class. Data were analyzed using Mplus version 7. Missing data were considered to be missing at random and analyzed within Mplus using Maximum Likelihood Ratio (MLR), a type of full-information maximum-likelihood (FIML) estimation. The optimal model was chosen based on an evaluation of fit statistics and considerations of theory. The most commonly used fit index is the Bayesian information criteria (BIC; D’Unger, Land, McCall, & Nagin, 1998) statistic. The model with the lowest BIC value is considered to be the best-fitting model. The Lo, Mendell, and Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001) was also considered, which compares the k-class model to the k–1 to determine whether the addition of each class improves upon the previous model.

In addition, we used the general linear model to examine placement information by profile group. In order to examine the association between RAD signs at age 12 years and other domains of psychopathology cross-sectionally, we conducted Pearson correlations with total symptom counts according to caregiver report on the DISC interview.

Results

Linear Mixed Modeling Analysis of RAD Signs

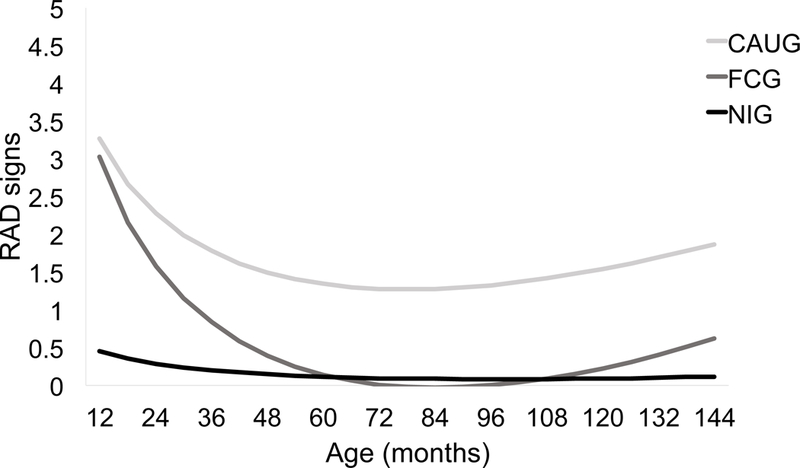

RAD scores were examined as a function of age using LMM, which allows for within individual change in RAD signs across development. Group status (i.e., CAUG, FCG, and NIG) was examined in relation to the intercept and slope across development. Three age models were examined (linear, quadratic, and cubic age), and given that the quadratic term, but not the cubic age term, was a significant predictor of RAD and significantly interacted with group status, this model was retained (see Table 2). As can be observed in Figure 2, both the FCG and CAUG groups, on average, had more RAD signs in early life compared to the NIG (intercepts centered at age 12 months demonstrated statistically significant differences from the NIG; p’s < .001), and did not differ from one another. Further, as predicted and consistent with Smyke et al. (2012), although RAD signs declined in early childhood for both the CAUG and FCG, the FCG exhibited a steeper decline than the CAUG from baseline until the end of the formal intervention (age 54 months; F(1, 273.38) = 6.72, p = .10), suggesting a more dramatic decrease in RAD signs. The FCG, on average, had low levels of signs of RAD from age 54 months until early adolescence, whereas the CAUG remained relatively elevated, on average, throughout childhood and into early adolescence. These findings extend upon prior work from this sample that ended at the age 8 assessment, indicating that rather than finding a consistent drop in signs of RAD across development among the CAUG, as suggested in Smyke et al. (2012), we find that signs of RAD in later childhood appear to plateau and even slightly increase among the CAUG in early adolescence.

Table 2:

Mixed Modeling Fixed Effect Estimates of Group by Age on Reactive Attachment Disorder Signs

| Variable | F | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 62.14 | 3, 866.18 | <.001 |

| Age (months) | 81.54 | 1, 798.28 | <.001 |

| Quadratic Age | 66.44 | 1, 794.95 | <.001 |

| Group by Age | 15.61 | 2, 798.06 | <.001 |

| Group by Quadratic Age | 12.42 | 2, 794.16 | <.001 |

Figure 2:

Estimated levels of caregiver-reported RAD signs as a function of group across development. Notes. CAUG = care as usual group. FCG = foster care group. NIG = never institutionalized group.

Growth Mixture Modeling of RAD Signs

Latent profiles of RAD signs from baseline to 12 years of age were examined using GMM. Given model fit parameters, models were specified using a Poisson error distribution. Models for 2 through 5 profile solutions were tested to arrive at the optimal number of profiles. Fit indices are presented in Table 3. The BIC suggests that the 3-profile model is the best fitting because it has the lowest value, however, the value for the 4-profile model is similar. The LMR-LRT statistic suggests that a 4-profile model improves upon the 3-profile model. Therefore, the 4-profile model was chosen as the best fitting model based on fit indices as well as considerations of theory.

Table 3:

Fit Indices for Growth Mixture Models

| LMR-LRT |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | BIC | Loglikelihood value | p-value |

| 2-profile | 2320.562 | −1155.62 | .022 |

| 3-profile | 2330.696 | −1149.74 | .004 |

| 4-profile | 2332.800 | −1139.15 | .002 |

| 5-profile | 2348.588 | −1132.19 | .768 |

Note. BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria. LMR-LRT = Lo-Mendel-Rubin likelihood ratio test.

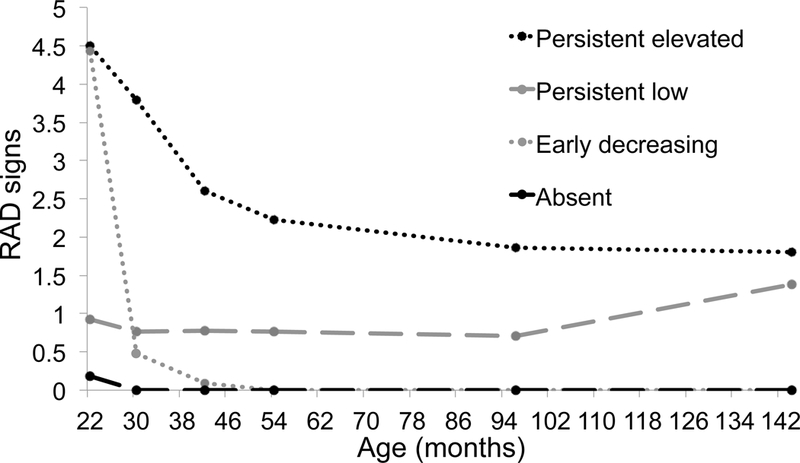

Figure 3 presents the trajectories for the 4-profile solution. One profile, labeled “persistent elevated” contains children who in early life had high levels of RAD signs and continued to be elevated across assessment waves. Another, labeled “early decreasing” contains children who initially had high scores in early life followed by a dramatic decrease in RAD signs across assessment waves. The remaining two profiles depict relatively stable courses of signs over time. One profile, labeled “persistent low” contains children who consistently were rated in the low to moderate range across assessment waves. The third profile, labeled “absent” contains children who consistently demonstrated few to no signs of RAD across waves.

Figure 3:

Mean levels of caregiver-reported RAD signs across development for each profile

Associations with Group and Sex.

The Pearson χ2 test of independence revealed a significant relation between group and profile indicating that the profiles contain different distributions of children across groups (χ2(6) = 92.49, p < .001). Table 4 presents the distribution of the number of children in each RAD symptom profile by group membership. The “persistent elevated” profile, the profile characterized by the highest RAD levels, mostly comprised children from the CAUG and included no children from the NIG. The “persistent low” profile contained approximately half of children from the CAUG and the FCG and about a third of the NIG. The “early decreasing” profile contained nearly one-third of the children from the FCG, but a small number of CAUG and NIG children. Finally, the absent profile contains the largest proportion of the NIG children, with some FCG and a few CAUG children. There was no relationship between sex and RAD symptom profile (χ2 = 3.83[3], p = .280).

Table 4:

Group Membership and Sex by RAD Symptom Profile

| Persistent elevated (n = 24) | Persistent low (n = 91) | Early decreasing (n = 23) | Absent (n = 55) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | ||||

| AUG (n = 61) | 21 (88%) | 32 (35%) | 4 (17%) | 4 (7%) |

| FCG (n = 63) | 3 (12%) | 33 (36%) | 17 (74%) | 10 (18%) |

| NIG (n = 69) | 0 (0%) | 26 (29%) | 2 (9%) | 41 (75%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (n = 92) | 13 (54%) | 47 (52%) | 7 (30%) | 25 (45%) |

| Female (n = 101) | 11 (46%) | 44 (48%) | 16 (70%) | 30 (55%) |

Note. CAUG = care as usual. FCG = foster care group. NIG = never institutionalized group.

Associations with Age of Placement and Institutional Care History.

RAD profiles were compared in terms of two placement variables: age of placement into foster care (among the FCG only), and age of first placement into a family (for the FCG and CAUG children ever placed in family care). Profiles also were compared in terms of percent time spent in the institution through age 54 months, percent time institutionalized through age 12 years controlling for time spent through age 54 months, and number of placement disruptions from birth to age 12 years. Differences in placement and institutional care variables were analyzed using analysis of variance (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean Differences in Age (in Months) Entered Foster Care (FCG only) and Age First Placed into a Family (FCG and CAUG only)

| Persistent elevated | Persistent low | Early decreasing | Absent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F (df) | Partial η2 | Pairwise comparisons | |

| Age in months entered foster care | 28.20 | 3.74 | 25.49 | 1.15 | 20.00 | 1.67 | 18.96 | 18.96 | 4.57 (3, 56) ** | .197 | PL > ED, A |

| Age in months first placed in a family | 39.33 | 3.25 | 33.17 | 1.95 | 20.39 | 3.33 | 2.05 | 2.05 | 6.12 (3, 114) ** | .139 | PE, PL > ED |

| Percent time in institution through age 54 months | 75% | 20% | 55% | 24% | 34% | 14% | 28% | 28% | 14.01 (3,111) *** | .275 | PE > PL, ED, A PL > ED |

| Percent time in institution through age 12 yearsa | 53% | 31% | 29% | 23% | 13% | 5% | 4% | 4% | 2.85 (3, 99)* | .079 | PE > PL |

| Number of placement disruptions through age 12 years | 4.00 | 2.11 | 3.48 | 1.40 | 2.81 | 1.25 | 3.07 | 1.39 | 2.51 (3, 120) | .059 | PE>ED |

Note. FCG = foster care group. CAUG = care as usual group. PE = persistent elevated. PL = Persistent low. A = Absent. ED = early decreasing.

Controlling for percent time through 54 months.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .01.

There was a significant association between age placed in foster care and RAD profile. Tukey post-hoc tests revealed that FCG children in the “persistent low” profile were placed into foster care at a significantly older age than children in the “absent” and “early decreasing” profiles.

Age placed into a family for children in the FCG and CAUG was also found to be associated with RAD profile. Tukey post-hoc tests revealed that children in the “persistent elevated” and “persistent low” profiles were first placed into families at a significantly older age than children in the “early decreasing” profile.

Percent time in the institution through age 54 months also differed significantly by RAD profile. Children in the “persistent elevated” profile had a higher percent time in institutional care compared to children in all other profiles. Additionally, children in the “persistent low” profile spent a significantly higher percentage of time in institutional care compared to children in the “early decreasing” profile.

Percent time in institutional care at 12 years was also examined while controlling for percent time through 54 months to assess the impact of later experiences. Significant differences between RAD profiles were revealed. The only significant difference was that children in the “persistent elevated” profile had a higher percent time in institutional care through age 12 compared to children in the “persistent low” profile.

Lastly, we examined the number of placement disruptions that occurred from birth through age 12 year for children as a function of profile. The omnibus test revealed no significant differences overall; however, Tukey’s post hoc tests indicated that the “persistent elevated” profile had a greater number of total disruptions than those in the “early decreasing” profile.

Age 12 Year Reactive Attachment Disorder Signs and Psychopathology.

RAD signs were modesty and significantly associated with internalizing (i.e., anxiety and depression symptoms; r(127)=.23, p=.009), externalizing (i.e., oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder symptoms; r(126)=.31, p<.001), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms (r(126)=.29, p=.001).

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to characterize the course of RAD from early childhood to early adolescence by examining group- and individual-level longitudinal patterns and to determine which variables differentiate those patterns over time. This is the first known report of findings on the longitudinal course of RAD from early childhood into early adolescence. Different patterns of RAD signs across development were identified and found to differ based on history of institutional care and ITT group. Within the ever-institutionalized children, details about their institutional care history, as well as age when children were placed in families, were associated with the course of RAD signs across development. At age 12, RAD signs demonstrated a small positive association with other domains of psychopathology.

Two sets of analyses provided different perspectives on the longitudinal course of RAD from early childhood to early adolescence. Variable-centered analyses examined patterns of change within each ITT group and demonstrated that signs of RAD for children with a history of institutional placement decreased from baseline to 54 months, with the sharpest decrease observed in the FCG, reflecting a robust effect of the RCT intervention and consistency with prior work from this sample (Humphreys et al., 2017; Smyke et al., 2012). Therefore, placing children in families early in life led to a sustained reduction in signs of RAD through early adolescence. Following the initial steep decline, rather than following a linear trend in decreased symptoms, a quadratic change in signs was observed. This change in slope, from steep decline to relative flattening in RAD signs across development from age 54 months to 12 years, indicated that at least on the group level, there is stability of RAD levels across childhood and into adolescence.

As opposed to group level a priori approaches to examining RAD signs across development that maintained the integrity of randomization, our GMM analyses identified common patterns of change in the data, regardless of ITT group membership. Profiles of both stable and decreasing patterns of RAD over time were observed. One profile, “persistent elevated,” contained children, mostly from the CAUG, who initially decrease from baseline to 54 months but continued to exhibit stable, elevated levels of RAD signs across ages 8 and 12 years. The “persistent low” profile comprised children who exhibited persistently mild elevations of RAD signs over time. Children in the “persistent low” profile were observed to have a slight increase in signs from age 8 to age 12 years. The “persistent low” profile is a previously unidentified pattern that was not hypothesized a priori, highlighting the latent heterogeneity in RAD signs as well as the advantage of using multiple statistical approaches. The “early decreasing” profile contained children whose RAD signs decreased sharply from baseline to 54 months and continued to exhibit little to no signs across development, and was primarily comprised FCG children. Finally, in the “absent” profile, children were reported to have little to no signs of RAD from baseline through age 12. Despite a history of institutional care, there were children from both FCG and CAUG in this group, highlighting that some severely deprived children develop no signs of RAD.

Our findings demonstrate both consistency and change in signs of RAD from early childhood to adolescence. Taken together, the two sets of analyses suggest that signs of RAD vary significantly over time, and that both decreasing and stable patterns occur when examining the course from early childhood to early adolescence. No previous studies have examined signs of RAD into early adolescence and the effects early caregiving environments can have on attachment disordered behaviors later in development.

Examining profiles identified from GMM contributed insight about specific factors related to the intervention that predicted individual variability in RAD signs over time. Unlike previous findings about other forms of psychopathology in this sample (Humphreys, Gleason, et al., 2015; Humphreys, McGoron, et al., 2015; Zeanah et al., 2009), we did not find sex differences in relation to RAD. This is consistent with previous work examining RAD signs at single time points (Smyke et al., 2012; Zeanah et al., 2005), highlighting that RAD may be one of the rare psychiatric disorders without obvious sex differences.

The most important predictors of variability in signs of RAD over time involved family and institutional exposure. These included age of placement into foster care (among FCG children only), age first placed into a family (among FCG and CAUG children), and percent time spent in the institution prior to 54 months. As with many other outcomes from this study, age of placement into foster care emerged as a potential predictor of outcomes (see Nelson et al., 2014). Those children in the “persistent low” profile who were from the FCG were placed into foster care at significantly older ages than children in the “absent” and “early decreasing” profiles. No differences were found between children in the “persistent elevated” and other profiles, but this is likely due to the small number (n = 3) of FCG children in the profile.

Given that throughout the course of the study most children in the CAUG were placed into families (either government foster care, adopted within Romania, or returned to biological parents/extended families), we also examined age at first placement into a family for all ever-institutionalized children. We found that age at which a child was first placed into a family – foster, adoptive, or biological – proved predictive of profiles. Children in the “early decreasing” profile were placed at younger ages compared to children in the “persistent elevated” and “persistent low” profiles. Therefore, stable, even mildly elevated RAD signs over time are associated with longer periods in institutional care before being placed into families.

Related to this metric, differences between profiles were also found for percent time in institutional care through age 54 months. Spending a greater percentage of time in institutional care early in life was associated with stable moderate to high courses of RAD signs across development whereas spending less time in care was associated with either no symptoms of RAD over time or a dramatic drop in symptoms followed by sustained absent symptoms. Even after controlling for percent time in institutional care through 54 months, percent time in institutional care through age 12 years independently contributed to a different course of RAD signs. Children in the “persistent elevated” profile were found to spend a greater percent time in institutional care through 12 years compared to children in the “persistent low” profile. Further, those in the “persistent elevated” profile had more placement disruptions than those in the “early decreasing” profile. Taken together, results indicate that early deprivation has a more robust association with the course of RAD signs across development than later deprivation in institutional care, yet later childhood deprivation remained important in determining if the persistence of RAD signs were at lower or higher levels. Clearly, reducing the amount of time children spend in institutional care, ideally through earlier age of placement into families, has a significant impact on the developmental course of RAD.

Limitations

There are limitations in the present study. The signs used to assess RAD were consistent across all waves of assessment, which allows consistency in the scale of measurement and items used to assess RAD longitudinally, but this necessarily reduces developmental sensitivity. On the other hand, the purpose of the investigation was to assess continuity over time rather than how best to define RAD at various ages. As with almost all studies of RAD, caregiver report was used to assess RAD signs, which is subject to reporter bias. Observational methods to assess RAD would be useful in future investigations. Because of placement changes, caregivers who reported on children with a history of institutional rearing changed over time, introducing variability. Finally, studying children from an RCT who were followed from early childhood to early adolescence is a uniquely valuable sample, a larger sample size would increase confidence in the findings reported.

Conclusion

The course of RAD from early childhood to early adolescence varies significantly across children with a history of institutional rearing. Variation in course is affected by a high-quality foster care intervention, as well as the length of time children spend in institutionalized care. Both decreasing and stable patterns of RAD signs across development were identified, with a decreasing course associated with early family placement and a stable elevated course associated with increased exposure to institutional care. This is the first known study to examine the longitudinal course of RAD signs from early childhood through early adolescence. Further research on RAD beyond early adolescence is needed to better understand the presentation and impact of RAD across development. In particular, it will be important to determine the risks posed by early decreasing and by persistent high and low levels of RAD for social and psychological adaptation in adolescence. Continued research on the course of RAD across development and the variables associated with different trajectories will be beneficial in identifying ways to alter the course of RAD signs among young children exposed to deprivation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on “Early Experience and Brain Development” (Charles A. Nelson, Ph.D., Chair), NIMH (1R01MH091363; Nelson) (F32MH107129; Humphreys), Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (formerly NARSAD) Young Investigator Award 23819 (Humphreys), and Kingenstein Third Generation Foundation Fellowship (Humphreys).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition TR. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, & Association, A. A. P. (1994). DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC, Virginia: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, & Magnusson D (1997). A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Developmetal Psychopathology, 9(2), 291–319. 10.1017/S095457949700206X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Hanson R, Saunders BE, Nichols T, Barnett D, Zeanah C, … Letourneau E (2006). Report of the APSAC Task Force on attachment therapy, reactive attachment disorder, and attachment problems. Child Maltreatment, 11(1), 76–89. 10.1177/1077559505283699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Unger A, Land K, McCall P, & Nagin D (1998). How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed poisson regression analyses. American Journal of Sociology, 103, 1593–1630. 10.1086/231402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MM, Fox NA, Drury S, Smyke AT, Egger HL, Nelson CA, … Zeanah CH (2011). Validity of evidence-derived criteria for reactive attachment disorder: Indiscriminately social/disinhibited and emotionally withdrawn/inhibited types. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 216–231. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb W (1945). Effects of psychological deprivation in infancy and subsequent stimulation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 102(1), 18–33. 10.1176/ajp.102.1.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ, Ram N, & Estabrook R (2016). Growth modeling : structural equation and multilevel modeling approaches. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Miron D, Zeanah CH, Zeanah CH, … Zeanah CH (2015). Effects of institutional rearing and foster care on psychopathology at age 12 years in Romania: follow-up of an open, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(7), 625–634. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00095-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, McGoron L, Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA, Fox NA, Nelson CA, & Zeanah CH (2015). High-quality foster care mitigates callous-unemotional traits following early deprivation in boys: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(12), 977–983. 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2017). Signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years: Effects of institutional care history and high-quality foster care. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 675–684. 10.1017/S0954579417000256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Schlegelmilch A, Morgan TA & Abraham MM (2005). Assessing attchment in middle childhood In: Kerns K & Richardson R, R. (Eds.), Attachment in Middle Childhood , pp. 46–70. Guilford Press: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levy RJ (1947). Effects of institutional vs. boarding home care on a group of infants. Journal of Personality, 15(3), 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, & Rubin DB (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FG (2009). The randomized controlled trial as a demonstration project: An ethical perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(7), 743–745. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millum J, & Emanuel EJ (2007). The ethics of international research with abandoned children. Science, 318(5858), 1874–1875. 10.1126/science.1153822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, & Muthén LK (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(6), 882–91. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Fox NA, & Zeanah CH (2014). Romania’s Abandoned Children: Deprivation, Brain Development, and the Struggle for Recovery. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett R, Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, & Minnis H (2013). Risk factors for vulnerable youth in urban townships in South Africa: The potential contribution of reactive attachment disorder. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 8(May), 310–320. 10.1080/17450128.2012.756569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provence S, & Lipton RC (1962). Infants in Institutions. New York: International Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raaska H, Elovainio M, Sinkkonen J, Matomäki J, Mäkipää S, & Lapinleimu H (2012). Internationally adopted children in Finland: Parental evaluations of symptoms of reactive attachment disorder and learning difficulties - FINADO study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(5), 697–705. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, & Schwab-Stone ME (2000). NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 28–38. 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Dumitrescu A, & Zeanah CH (2002). Attachment disturbances in young children. I: The continuum of caretaking casualty. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(8), 972–82. 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Nelson CA, & Zeanah CH (2007). The caregiving context in institution-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 210–218. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, & Nelson CA (2009). A new model of foster care for young children: the Bucharest early intervention project. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18, 721–34. 10.1016/j.chc.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Fox NA, Nelson CA, & Guthrie D (2012). A randomized controlled trial comparing foster care and institutional care for children with signs of reactive attachment disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(5), 508–514. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11050748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Split J, Vervoort E, Koenen A-K, Bosmans G, & Verschueren K (2016). The socio-behavioral development of children with symptoms of attachment disorder: An observational study of teacher sensitivity in special education. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 56, 71–82. 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizard B, & Rees J (1974). A comparison of the effects of adoption, restoration to the natural mother, and continued institutionalization on the cognitive development of four-year-old children. Child Development, 45(1), 92–99. 10.1111/1467-8624.ep12265481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort E, De Schipper JC, Bosmans G, & Verschueren K (2013). Screening symptoms of reactive attachment disorder: Evidence for measurement invariance and convergent validity. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 22(3), 256–265. 10.1002/mpr.1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolgar M, & Scott S (2013). The negative consequences of over-diagnosing attachment disorders in adopted children: The importance of comprehensive formulations. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(3), 355–366. 10.1177/1359104513478545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Chesher T, Boris NW, Walter HJ, Bukstein OG, Bellonci C, … Stock S (2016). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(11), 990–1003. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Egger HL, Smyke AT, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, & Guthrie D (2009). Institutional rearing and psychiatric disorders in Romanian preschool children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(7), 777–85. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08091438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Fox NA, & Nelson CA (2012). The Bucharest Early Intervention Project: case study in the ethics of mental health research. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200, 243–7. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318247d275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, & Gleason MM (2015). Annual Research Review: Attachment disorders in early childhood–clinical presentation, causes, correlates, and treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 207–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Koga SF, Simion B, Stanescu A, Tabacaru CL, Fox NA, … Woodward HR (2006). Response to commentary: Ethical dimensions of the BEIP. Infant Mental Health Journal. 10.1002/imhj.20117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Smyke AT, Marshall P, Parker SW, & Koga S (2003). Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 885–907. 10.1017/S0954579403000452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Scheeringa M, Boris NW, Heller SS, Smyke AT, & Trapani J (2004). Reactive attachment disorder in maltreated toddlers. Child Abuse and Neglect, 28(8), 877–888. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Koga SF, & Carlson E (2005). Attachment in institutionalized and community children in Romania. Child Development, 76(5), 1015–28. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00894.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zero to Three. (2016). DC:0–5: Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.