To the Editor:

The term “overlap syndrome” was introduced to describe the coexistence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in a single individual (1), and it is associated with a severe clinical course. An OSA-related nocturnal desaturation is more profound in the presence of COPD, and daytime hypoxemia due to COPD is worse in the presence of OSA (2). Patients with overlap syndrome are far more likely to develop pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure than patients with either condition alone (3, 4). As a result, patients with overlap syndrome have significantly worse quality of life, greater risk of morbidity and mortality, and a substantially higher medical care use and cost than those with either diagnosis independently (5–7). We conducted a claims-based study of Medicare beneficiaries to examine the diagnosed prevalence and trend of overlap syndrome, as well as its patient characteristics.

Methods

Data Source

This study used enrollment and claims data over 2004-2013 from a 5% national sample of Medicare beneficiaries. Data used in this study were gathered from multiple files: 1) Medicare Denominator File, 2) Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File, 3) Outpatient Standard Analytic File, 4) 100% Physician/Supplier Data File, and 5) Durable Medical Equipment File (8).

Study Cohort

All patients with COPD were identified as previously reported (9). Exclusion criteria were age 65 years or younger, residence in a nursing facility or enrollment in a health maintenance organization plan, or lack of completed enrollment in Medicare parts A and B for 12 months or longer or until death in study year and the 12 months before the study year. Among patients with COPD, we first categorized those with overlap syndrome who had at least one visit with an encounter diagnosis of OSA (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9], codes: 780.51, 780.53, 780.57, 786.03, 327.20, 327.23). We repeated this process for each year. Second, we defined OSA more specifically, including those with OSA diagnosis and polysomnography (PSG) at each year. Third, besides PSG, we further required patients with OSA to have positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy. The study cohort included all patients with COPD who met the criteria listed above any time during the study period. Patients identified with either COPD or OSA were labeled with the diagnosis in subsequent years unless they died or lost Medicare coverage.

Patient Characteristics

Medicare enrollment files were used to categorize subjects by age, sex, and race. Socioeconomic status was based on whether the patient was eligible for state buy-in coverage provided by the Medicaid program for at least one month during the calendar year. Comorbidity number was generated by using the Elixhauser comorbidity index excluding COPD (10). Specific conditions that are common in patients with COPD and OSA were generated by using ICD-9 diagnosis codes. COPD complexity was determined by using the algorithm described by Mapel and colleagues (11). Geographic regions were designated by the eight Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services regions. PSG and PAP therapy were identified as previously described (9).

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. The Cochran-Armitage test was used to examine the trends. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute). All reported P values were two sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

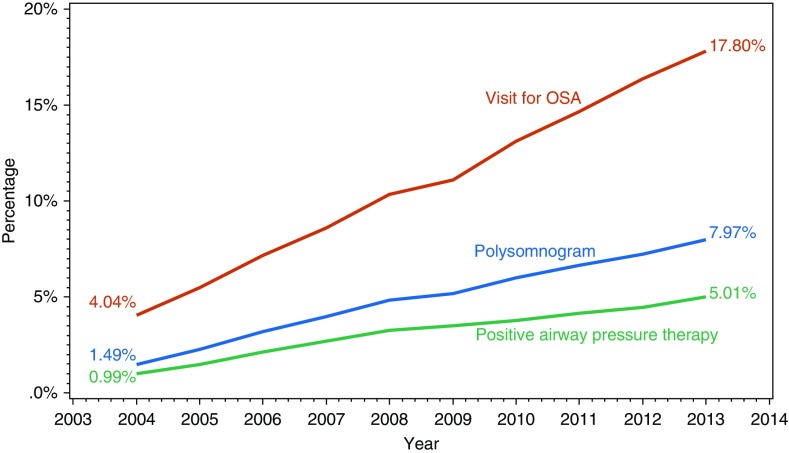

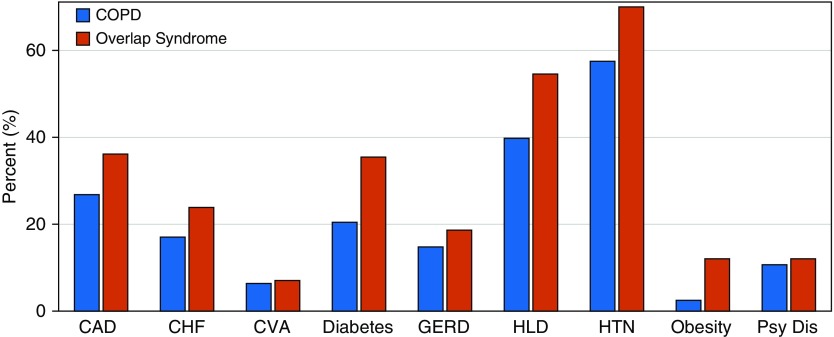

A total of 159,084 unique patients with COPD were included in the study. The characteristics of patients with COPD versus overlap syndrome are compared in Table 1. Overall, 11.0% of the COPD cohort had coexisting OSA. Compared with patients with COPD alone, patients with overlap syndrome were likely to be younger and male, to have a higher number of comorbid conditions, and to have more complex COPD. Over the 10-year study period, diagnosed overlap syndrome increased from 4.04% in 2004 to 17.80% in 2013 based on visit for OSA; 1.49% in 2004 to 7.97% in 2013 based on having PSG and 0.99% in 2004 to 5.01% in 2013 based on having PSG and receipt of PAP therapy (Figure 1). The distribution of specific conditions in patients with isolated COPD versus overlap syndrome is presented in Figure 2. As expected, patients with overlap syndrome had significantly higher rates of those conditions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coexisting obstructive sleep apnea (overlap syndrome)

| Characteristics | COPD (n [%]) | Overlap Syndrome (n [%]) | Prevalence of Overlap Syndrome within Each Subgroup (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total subjects, n | 141,568 (89.0) | 17,516 (11.0) | |

| Age, yr | |||

| 66–74 | 68,053 (48.1) | 11,294 (64.5) | 14.2 |

| 75–84 | 56,060 (39.6) | 5,449 (31.1) | 8.9 |

| ≥85 | 17,455 (12.3) | 773 (4.4) | 4.2 |

| Mean (SD) | 75.70 (7.0) | 73.00 (5.8) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 63,406 (44.8) | 10,202 (58.2) | 13.9 |

| Female | 78,162 (55.2) | 7,314 (41.8) | 8.6 |

| Race | |||

| White | 127,629 (90.2) | 15,894 (90.7) | 11.1 |

| Black | 8,256 (5.8) | 1,085 (6.2) | 11.6 |

| Other | 5,683 (4.0) | 537 (3.1) | 8.6 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| High | 115,772 (81.8) | 14,877 (84.9) | 11.4 |

| Low | 25,796 (18.2) | 2,639 (15.1) | 9.3 |

| Comorbidities (10) | |||

| 0 | 30,891 (21.8) | 2,230 (12.7) | 6.7 |

| 1 | 34,984 (24.7) | 3,511 (20.0) | 9.1 |

| 2 | 28,611 (20.2) | 3,659 (20.9) | 11.3 |

| ≥3 | 47,082 (33.3) | 8,116 (46.3) | 14.7 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.09 (1.9) | 2.72 (2.1) | |

| COPD complexity (11) | |||

| Low | 31,387 (22.2) | 2,755 (15.7) | 8.1 |

| Moderate | 84,607 (59.8) | 10,513 (60.0) | 11.1 |

| High | 25,574 (18.1) | 4,248 (24.3) | 14.3 |

| Region | |||

| New England | 7,420 (5.2) | 756 (4.3) | 9.3 |

| Middle Atlantic | 19,540 (13.8) | 1,871 (10.7) | 8.7 |

| South Atlantic | 32,803 (23.2) | 4,554 (26.0) | 12.2 |

| East North Central | 24,394 (17.2) | 2,983 (17.0) | 10.9 |

| East South Central | 11,900 (8.4) | 1,468 (8.4) | 11.0 |

| West North Central | 9,019 (6.4) | 1,148 (6.6) | 11.3 |

| West South Central | 15,744 (11.1) | 2,042 (11.7) | 11.5 |

| Pacific | 13,677 (9.7) | 1,579 (9.0) | 10.4 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SD = standard deviation.

P < 0.0001 by chi-square test for all data in the table.

Figure 1.

Trend in prevalence of diagnosed overlap syndrome, by a visit for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), having a polysomogram, and receipt of positive airway pressure therapy from 2004 to 2013. Visit for OSA identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes: 780.51, 780.53, 780.57, 786.03, 327.20, and 327.23. Polysomnogram identified by Current Procedural Terminology codes: 95806, 95807, 95808, 95810, 95811, G0400, G0398, and G0399. Positive airway pressure therapy identified by Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes: E0470, E0471, E0601, E0561, and E0562. Cochran-Armitage trend test has P value less than 0.0001.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of select conditions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and overlap syndrome. P < 0.001 for all conditions. Abbreviations: CAD = coronary artery disease (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9], codes: 410, 411, 412, 413, 414, 429.2); diabetes (ICD-9 code: 250), obesity (ICD-9 codes: 278.0, 278.00, 278.01, V854, V8530, V8531, V8532, V8533, V8534, V8535, V8536, V8537, V8538, V8539); CHF = congestive heart failure (ICD-9 codes: 425, 428, 429.3, 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13,404.91, 404.93); CVA = cerebrovascular accident (ICD-9 codes: 433, 434, 435,436, 438, 437.1, 437.8, 437.9); GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease (ICD-9 codes: 531–535, 536.8, 530.1, 530.2, 530.3, 530.4, 530.7, 530.9, 530.81, 530.82, 530.85, 530.88, 530.89); HLD = hyperlipidemia (ICD-9 codes: 272.0–272.4); HTN = hypertension (ICD-9 codes: 401, 402, 403, 404, 405, 437.2); Psy Dis = psychiatric disorder (ICD-9 codes: 311, 295, 296, 297, 298, 300.0, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1).

Discussion

In our study, the prevalence of diagnosed overlap syndrome varied among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with COPD. It ranges from 1 in 6 based on claims for an OSA visit to 1 in 20 based on claims for PSG and PAP therapy in 2013. Consistent with other studies, our findings show that comorbidities and COPD complexity, a marker for health care use, are higher in patients with overlap syndrome than in those with COPD only (11–13).

To our knowledge, this is the first epidemiologic study to analyze the prevalence and trend of diagnosed overlap syndrome in subjects with COPD using administrative claims data. One of the most notable findings of this study is the rapid increase in diagnosed overlap syndrome prevalence over the 10-year study period, regardless of criteria. This sharp rise is multifactorial and attributable to increased awareness, higher prevalence of risk factors for OSA, and increased availability of sleep studies.

Our study has several limitations. The prevalence was assessed by diagnostic coding by clinicians rather than clinical laboratory testing, such as spirometry for COPD or PSG for OSA, and can lead to inaccuracies (14–16). Our study includes fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries and may not be generalizable to non-Medicare populations. These results may reflect secular trends rather than specific increases in the COPD population. However, when we examined the prevalence of OSA in a 5% fee-for-service non-COPD Medicare population over the same 10-year period, we found that the overall prevalence of OSA in patients with COPD is much higher than that seen in the general population. Also, even though providers are more likely to order sleep studies for patients with COPD owing to increased awareness, the prevalence of sleep study testing grew at a similar rate for both populations.

Conclusions

In summary, the prevalence of diagnosed overlap syndrome increased fourfold over the 10-year study period.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grants R01-HS020642 and R24-HS022134.

Author Contributions: P.S.: served as principal author, had full access to the data in the study, and takes full responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the accuracy of the data analysis; and A.A., G.S., W.Z., Y.-F.K., C.B., and G.S.: contributed to the conception, study design, analysis, interpretation of results, and drafting and final approval of the manuscript.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Flenley DC. Sleep in chronic obstructive lung disease. Clin Chest Med. 1985;6:651–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaouat A, Weitzenblum E, Krieger J, Ifoundza T, Oswald M, Kessler R. Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:82–86. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weitzenblum E, Chaouat A, Kessler R, Canuet M. Overlap syndrome: obstructive sleep apnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:237–241. doi: 10.1513/pats.200706-077MG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley TD, Rutherford R, Grossman RF, Lue F, Zamel N, Moldofsky H, et al. Role of daytime hypoxemia in the pathogenesis of right heart failure in the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131:835–839. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mermigkis C, Kopanakis A, Foldvary-Schaefer N, Golish J, Polychronopoulos V, Schiza S, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (overlap syndrome) Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:207–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaouat A, Weitzenblum E, Krieger J, Sforza E, Hammad H, Oswald M, et al. Prognostic value of lung function and pulmonary haemodynamics in OSA patients treated with CPAP. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:1091–1096. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13e25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marin JM, Soriano JB, Carrizo SJ, Boldova A, Celli BR. Outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: the overlap syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:325–331. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1869OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Basic Stand Alone (BSA) Medicare Claims Public Use Files (PUFs) Baltimore, MD: U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2017 [last updated 2017 Feb 10; accessed ▪▪▪]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/BSAPUFS/index.html.

- 9.Singh G, Agarwal A, Zhang W, Kuo Y-F, Sultana R, Sharma G. Impact of PAP therapy on hospitalization rates in Medicare beneficiaries with COPD and coexisting OSA. Sleep Breath. doi: 10.1007/s11325-018-1680-0. [online ahead of print] 22 Jun 2018; DOI: 10.1007/s11325-018-1680-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mapel DW, Dutro MP, Marton JP, Woodruff K, Make B. Identifying and characterizing COPD patients in US managed care: a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of administrative claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Make B, Dutro MP, Paulose-Ram R, Marton JP, Mapel DW. Undertreatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and Medicare patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:1–9. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S27032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mapel DW, Hurley JS, Frost FJ, Petersen HV, Picchi MA, Coultas DB. Health care utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case-control study in a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2653–2658. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han MK, Kim MG, Mardon R, Renner P, Sullivan S, Diette GB, et al. Spirometry utilization for COPD: how do we measure up? Chest. 2007;132:403–409. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Javaheri S, Caref EB, Chen E, Tong KB, Abraham WT. Sleep apnea testing and outcomes in a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:539–546. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0406OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuohy CV, Montez-Rath ME, Turakhia M, Chang TI, Winkelman JW, Winkelmayer WC. Sleep disordered breathing and cardiovascular risk in older patients initiating dialysis in the United States: a retrospective observational study using Medicare data. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:16. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0229-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.