Abstract

Uracil arises in DNA by hydrolytic deamination of cytosine (C) and by erroneous incorporation of deoxyuridine monophosphate opposite adenine, where the former event is devastating by generation of C → thymine transitions. The base excision repair (BER) pathway replaces uracil by the correct base. In human cells two uracil-DNA glycosylases (UDGs) initiate BER by excising uracil from DNA; one is hSMUG1 (human single-strand-selective mono-functional UDG). We report that repair initiation by hSMUG1 involves strand incision at the uracil site resulting in a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde designated uracil-DNA incision product (UIP), and a 5′-phosphate. UIP is removed from the 3′-end by human apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease 1 preparing for single-nucleotide insertion. hSMUG1 also incises DNA or processes UIP to a 3′-phosphate designated uracil-DNA processing product (UPP). UIP and UPP were indirectly identified and quantified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and chemically characterised by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass-spectrometric analysis of DNA from enzyme reactions using 18O- or 16O-water. The formation of UIP accords with an elimination (E2) reaction where deprotonation of C2′ occurs via the formation of a C1′ enolate intermediate. A three-phase kinetic model explains rapid uracil excision in phase 1, slow unspecific enzyme adsorption/desorption to DNA in phase 2 and enzyme-dependent AP site incision in phase 3.

INTRODUCTION

Although uracil (U) formed by deamination of cytosine (C) is most harmful to cell function due to formation of C → thymine (T) transition mutations (1,2), which are the most common spontaneous mutation in cells frequently found in human tumours (3), uracil is also incorporated into DNA opposite adenine (A) through deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) which has escaped dUTPase digestion (4). Uracil in DNA is repaired by the base excision repair (BER) pathway (5,6) initiated by a uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG; EC 3.2.2.27), constituting the UDG superfamily (7) sharing gross architecture and organisation of the active site. The major and most effective UDG for removal of uracil from nuclear DNA in human cells is hUNG2, while hUNG1 is the mitochondrial splice variant (family 1 UDG). hUNG2 is believed to be responsible for both pre-replicative removal of deaminated cytosine [U opposite guanine (G)], post-replicative removal of mis-incorporated uracil (U opposite A) at the replication fork, as well as removal of deaminated cytosine outside of replication foci. In contrast, hSMUG1 (human single-strand-selective mono-functional UDG; family 3 UDG) (8) has been proposed the role as a backup UDG in the absence of hUNG (9). Additionally, hSMUG1 also has a broader substrate specificity removing pyrimidines damaged by oxidation like 5-hydroxyuracil, 5-hydroxymethyluracil, 5-formyluracil and 5-carboxyuracil in addition to 5-fluorouracil (10–13). Thus, hUNG exhibits a strict active site which is nearly specific for uracil while that of hSMUG1 is relaxed (14,15). While hUNG is upregulated during S-phase and binds to the replication clamp [PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen)] to efficiently remove U opposite G (and A) before mutation fixation by the replicative polymerase, hSMUG1 is a constitutive enzyme to initiate BER in non-replicating cells (9,16). While hUNG rapidly leaves the apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site for human AP endonuclease 1 (hAPE1), hSMUG1 competes with hAPE1 for AP site-binding to slowly be replaced by hAPE1 (17). Indeed, as opposed to hUNG and contradicting its name, hSMUG1 interacts with both DNA strands where a specific interaction with G opposite an AP site strengthen the binding (17,18). Especially important for higher vertebrates is the involvement of hUNG in immunoglobulin diversification (19), where many molecular details including the participation of hSMUG1 still need to be more thoroughly defined (20,21).

Hitherto, all UDGs including the human family 2 UDG designated thymine-DNA glycosylase (22), because of its involvements in other cellular functions than uracil repair (23,24), have been described as mono-functional enzymes depending on downstream BER proteins for AP site-incising and excising functions (25). In contrast, bi-functional DNA glycosylases have additional lyase activity carrying out a β- or β/δ-elimination reaction to incise the AP site, although the latter reaction is believed to predominantly being accomplished by hAPE1 (26,27). The 3′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) and 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde remnants after the β-elimination reaction are also removed by the 3′-phosphodiesterase function of hAPE1 (28), whereas the 3′-phosphate left after the β/δ-elimination reaction is removed by the human polynucleotide kinase phosphatase (hPNKP) (2). The BER pathway is completed by the sequential action of DNA polymerase β (29), which also removes the 5′-dRP by its lyase function if hAPE1 incised the AP site, and DNA ligase (1,2,6).

Following damaged base removal, DNA glycosylases bind the resulting AP site with different strengths to protect it from premature hydrolytic cleavage that may cause DNA strand breakage and collapse. This also contributes to recruit downstream BER proteins to the lesion site. Since hSMUG1, as mentioned above, binds the AP site much stronger than hUNG 17, we asked the question whether its active site residues causing glycosidic bond cleavage may come in position to react with AP site atoms. Indeed, here we show that exposure of DNA oligomers with deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) incorporated at a specific site (U-DNA) to hSMUG1 causes strand cleavage at the lesion site, indicating that the enzyme incises DNA after uracil removal. However, since the AP site is labile in water solutions, we determined its rate of cleavage in different buffers at different temperatures, and eventually quantified the non-enzymatic incision of hSMUG1-generated AP sites during the high-temperature sample preparation for denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Moreover, we measured hSMUG1-mediated incision of U-DNA in the absence of high temperature. The incision products were indirectly identified and quantitated by PAGE, and chemically identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation (MALDI) time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometric (MS) analysis of DNA from enzyme reactions in the presence of 18O- or 16O-water. We developed a model describing the kinetics of the U-DNA incision activity, which accords with known characteristics for hSMUG1 regarding uracil excision and DNA binding, and suggest a novel catalytic mechanism for DNA strand incision by glycosylases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide substrates

Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) with uracil at a specific site protected by phosphorothioate (four bonds) at each end was supplied with synthetically incorporated Cy3 fluorophore (or without it when labelled with [γ-32P]ATP) by Sigma or Eurofins MWG: 5′-TAGACATTGCCCTCGAGGTAUCATGGATCCGATTTCGACCTCAAACCTAGACGAATTCC G-3′ [60 nucleotides (nt); to prepare substrate 1]; 5′-[Cy3]-CCCTCGAGGTAUCATGGATCCGATCG-3′ (26 nt; to prepare substrate 2). Equimolar amounts of the labelled and complementary strands were annealed, with U opposite G, respectively, by heating at 95°C for 4 min followed by cooling to room temperature for 2 h. For MS analyses, substrate 2 (unlabelled) from Sigma and Eurofins MWG was not protected with phosphorothioate.

Enzymes

hSMUG1 (full length) was obtained from NEB (New England BioLabs) and investigated for contaminants by MS analysis (see Supplementary Table S1) as well as purified by us [see Supplementary Data, Production of purified hSMUG1(25–270) and Supplementary Figure S2]. EcUng was obtained from NEB, Fermentas and Trevigen; EcNfo was obtained from Fermentas; EcFpg, EcNth, hOGG1 and hAPE1 were obtained from NEB; hUNG (hUNGΔ84 with/without His-tag) (9,30) was a gift from B. Kavli and G. Slupphaug.

Assays for incision of U-DNA

Purified protein was incubated with U-DNA (substrate 1 or 2) in 45 mM HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulphonic acid]–KOH, pH 7.8, 0.4 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 70 mM KCl, 2% (v/v) glycerol (reaction buffer) at 37°C (final volume, 20 μl), unless otherwise stated. To convert U-DNA into AP-DNA, either substrate 1 (0.5 pmol) or substrate 2 (1 pmol) was incubated with EcUng (1 pmol) for 20 min using the same conditions. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 20 mM EDTA, 0.5% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and proteinase K (190 μg/ml) followed by precipitation of DNA with 96% ethanol containing 0.1 M sodium acetate supplemented with 16 μg tRNA followed by solubilisation in water (10 μl) (31). Enzymatic excision of uracil, which results in an alkali-labile AP site, was monitored in parallel by the extent NaOH (0.1 M final concentration; 10 min at 90°C) cleaved the DNA (32). Samples (10 μl) were added 10 μl of a loading solution containing 80% (v/v) formamide, 1 mM EDTA and 0.05% (w/v) xylene cyanol, and in the initial experiments following the conventional procedure, incubated at 95°C for 5 min to denature DNA (see Figure 1A). After cooling on ice, a portion of each sample (5 μl) was analysed by denaturing PAGE [20% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels with 7 M urea; see Figure 1B]. To measure non-enzymatic incision of AP-DNA in different solutions at different times and temperatures, we used the same conditions and/or procedure (see Figure 2A). To eliminate non-enzymatic cleavage of AP sites, the samples (10 μl; DNA dissolved in water) were treated at room temperature instead of 95°C, and following addition of the loading solution referred to above (10 μl) subjected to PAGE without delay, where the gel [20% (w/v)] contained 3% (v/v) formamide instead of urea (see Figure 4A). However, in the experiments determining the relative migration of the different 3′-end products, the PAGE gel [20% (w/v)] contained 7 M urea (see Figure 7). Visualisation and quantification were performed by fluorescence or phosphor imaging analysis using ImageQuant Software (Molecular Dynamics Inc.). The graphs were drawn using KaleidaGraph version 4.1.0 (Synergy Software).

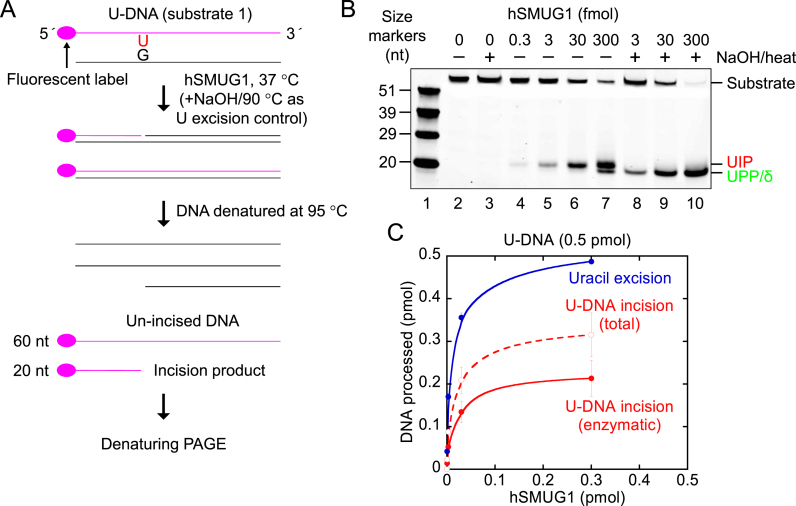

Figure 1.

Indication of hSMUG1 incision at uracil in DNA. (A) DNA substrate and conventional base excision assay. (B, C) Protein dependence of U-DNA incision (red) and uracil excision (blue). hSMUG1 was incubated with U-DNA (substrate 1, 0.5 pmol) in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 70 mM KCl at 37°C for 10 min. Each value in C represents the average (±SD) of three independent measurements. ‘U-DNA incision (total)’ corresponds to the values obtained from measuring the strength of the bands on the gel in B (lanes 4–7); the ‘U-DNA incision (enzymatic)’ values are calculated by subtracting the amount of AP site incision caused by the 5-min heat treatment at 95°C (as presented in Figure 2D) from the ‘U-DNA incision (total)’ values, where the number of AP sites formed by hSMUG1 equals the number of uracils excised as measured in parallel in B (lanes 8–10). Abbreviation: nt, nucleotides; UIP, U-DNA incision product; UPP, U-DNA processing product.

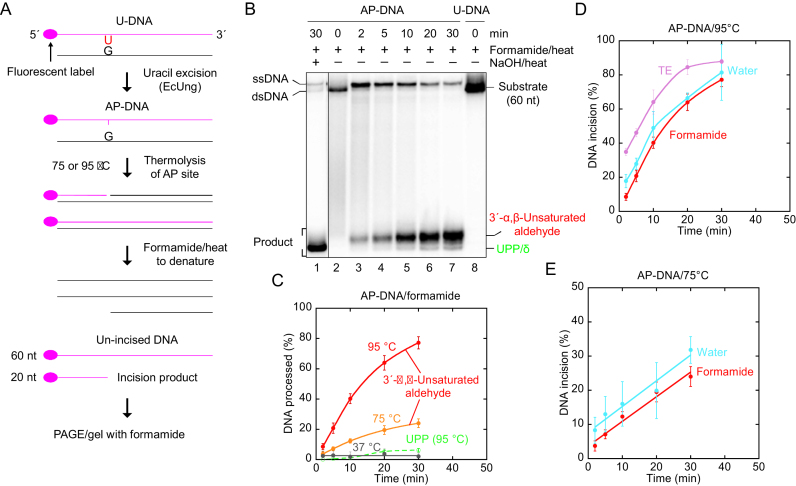

Figure 2.

Thermolysis of AP-DNA at high temperature efficiently forms UIP as opposed to UPP. (A) DNA substrate (see below) and assay. (B) Time dependence for cleavage of AP-DNA at 95°C. AP-DNA derived from substrate 1 (0.5 pmol) was treated with loading solution used in conventional denaturing PAGE [containing 80% (v/v) formamide]. UIP forms efficiently, while a smaller amount of UPP/δ-product appears at the longest incubation times. (C) Time dependence for cleavage of AP-DNA at different temperatures. AP-DNA derived from substrate 1 was used at 37°C (1 pmol) and 95°C (see B), while that used at 75°C (1 pmol) was derived from substrate 2 (see Materials and Methods). Each value represents the average (± SD) of 6–15 (95°C; red), 2–6 (75°C; orange) or 5–6 (37°C; dark grey) independent measurements. At 37°C, PAGE was performed on a 15% (w/v) gel containing 3% (v/v) formamide, and identical experiments with AP-DNA dissolved in pure water also showed no significant DNA cleavage (data not shown). UPP (green) was only formed at 95°C. (D) Time dependence for AP-DNA cleavage in different solutions at 95°C. Treatment in loading solution (red; described in B), water (blue) or TE buffer (violet) showed that the initial cleavage of AP-DNA is virtually identical in the different aqueous solutions. To separate incised DNA from un-incised DNA the reaction products were subjected to denaturing (red) or non-denaturing (blue; violet) PAGE. Each value represents the average (± SD) of 4–17 independent measurements, where the slopes of the graphs for the initial DNA incision, i.e. the first three data points (6–17 independent measurements; red, y = 3.95x + 0.769, R = 0.999; blue, y = 3.92x + 9.29, R = 0.998; violet, y = 3.65x + 27.673, R = 0.999) yield the non-enzymatic incision per min. This amounted to 3.95% of the AP sites incised per min, resulting in a background of 19.8% non-enzymatic hydrolysis (as calculated from the red graph; for the 5 min formamide/heat treatment) for the experiment described in Figure 1B and C. The amount of background incision was subtracted giving the value for enzymatic U-DNA incision for all experiments using 5 min heat treatment at 95°C (Figure 1C). (E) Time dependence for AP-DNA cleavage in different solutions at 75°C. AP-DNA (substrate 2, 1 pmol) was exposed to loading solution (red) or water (blue). Each value represents the average (±SD) of 6 (at 2–20 min) or 2–3 (at 30 min) independent measurements. To separate incised DNA from un-incised DNA the reaction products were subjected to denaturing (red) or non-denaturing (blue) PAGE. The initial slopes of the graphs (red, y = 0.722x + 3.65, R = 0.986; blue, y = 0.755x + 7.68, R = 0.977) yield the non-enzymatic incision per min. This amounted to 0.722% of the AP sites incised per min in the formamide solution. Abbreviation: δ, β/δ-elimination product.

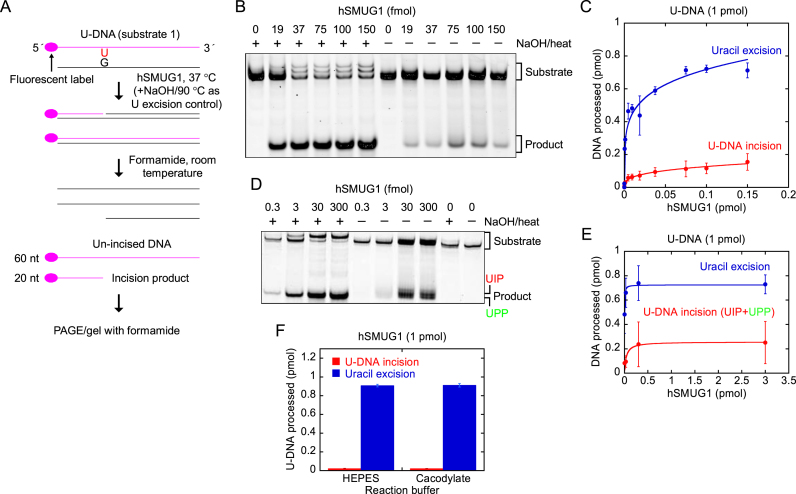

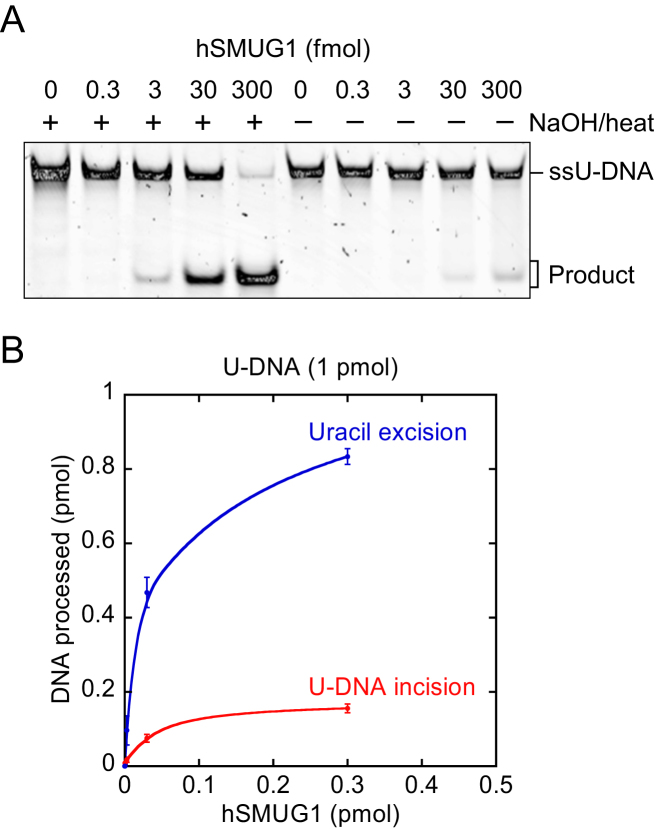

Figure 4.

hSMUG1 incises at uracil in DNA. (A) DNA substrate and assay. (B, C) Protein dependence of U-DNA incision (red) and uracil excision (blue). hSMUG1 was incubated with U-DNA (substrate 1, 1 pmol) at 37°C for 10 min. Each value in C represents the average (±SD) of 3–6 independent measurements. Incision product was separated from un-incised DNA by PAGE at 115 V for 1.5 h using a 20% (w/v) gel with 3% (v/v) formamide. (D) hSMUG1(25–270) was incubated with U-DNA (1 pmol of substrate 1; see A) at 37°C for 20 min. Incision product was separated from un-incised DNA by PAGE at 120 V for 2 h using a 20% (w/v) gel with 3% (v/v) formamide. (E) Protein dependence of U-DNA incision/processing (red) and uracil excision (blue). Each value represents the average (± SD) of 4–5 independent measurements as described in D. (F) U-DNA incision by hSMUG1 in different buffers. U-DNA (1 pmol of substrate 1) was incubated with 1 pmol of hSMUG1(25–270) or without enzyme as control in reaction buffer (HEPES), or in 45 mM sodium cacodylate with the same pH and additions as for reaction buffer (see Materials and Methods), at 37°C for 10 min (final volume, 20 μl). Incision product was separated from un-incised DNA by PAGE as described in E. Each value represents the average (±SD) of three independent measurements.

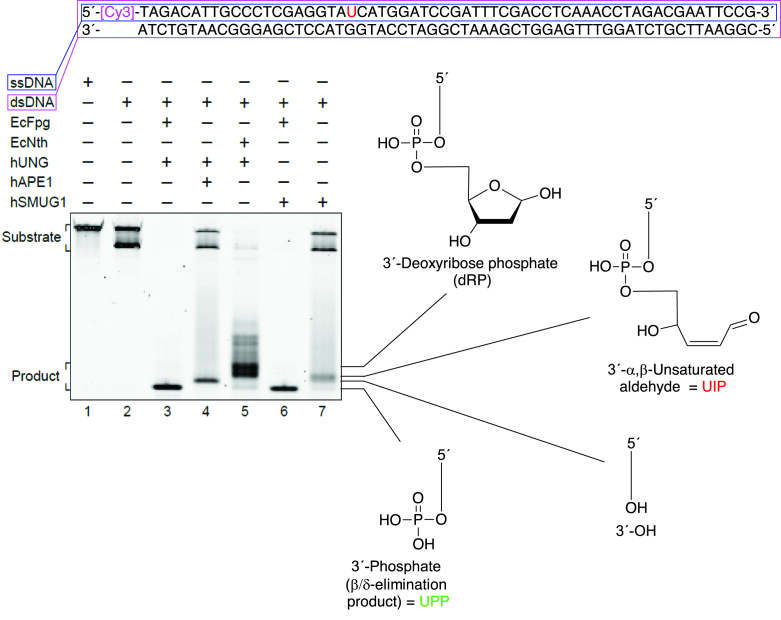

Figure 7.

Indirect identification of UIP by electrophoretic mobility without exposure of DNA to high temperature. U-DNA (substrate 1, 1 pmol) was incubated with hSMUG1 (0.3 pmol) at 37°C for 30 min; either alone or together with EcFpg (4 pmol) as indicated. To define the different 3′-end products, substrate was incubated with hUNG (1 pmol) together with either EcFpg (4 pmol), hAPE1 (0.45 pmol) or EcNth (1 pmol), as indicated, under the same conditions. Incubations were also performed with either substrate 1 (dsDNA; lane 2) or the labelled strand of substrate 1 (ssDNA; lane 1) alone, showing that the upper substrate band is ssDNA and the lower band dsDNA. Incision product was separated from un-incised DNA by PAGE at 300 V for 5 h using a 20% (w/v) gel with 7 M urea.

Trapping experiment for Schiff base intermediate

The assay was performed according to Zharkov et al. (33). Polydeoxynucleotide duplex containing a single U residue opposite G (substrate 2, 1 pmol) was incubated with enzyme (see Figure 6) and freshly dissolved 50 mM NaBH4 in reaction buffer at 37°C for 1 h (final volume, 10 μl). Reaction was terminated by the addition of 10 μl of DNA denaturing loading buffer (80% formamide, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% (w/v) bromophenol blue) and heated at 95°C for 5 min before loading into a 10% (w/v) denaturing PAGE gel. The gels were scanned using Typhoon Trio Imager (GE Healthcare). Visualisation and quantification were performed by phosphor imaging analysis using ImageQuant Software (Molecular Dynamics Inc.).

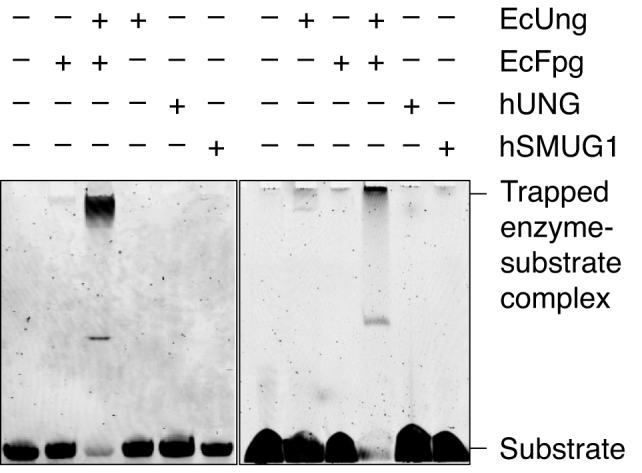

Figure 6.

Trapping experiments for Schiff base intermediate. Left panel, EcFpg (17 pmol) alone as a negative control, and together with EcUng (3 pmol) as a positive control, EcUng as well as hUNG (5 pmol) alone as negative controls, and hSMUG1 (0.3 pmol) alone, were incubated with substrate 2 (1 pmol) and 50 mM NaBH4 in reaction buffer at 37°C for 1 h (final volume, 10 μl). Right panel, EcFpg (10 pmol) alone as a negative control, and together with EcUng (10 pmol) as a positive control, EcUng as well as hUNG (10 pmol) alone as negative controls, and hSMUG1 (10 pmol) alone, were incubated with substrate 2 (1 pmol) and 50 mM NaBH4 in reaction buffer at 37°C for 1 h (final volume, 10 μl). In each case (A and B), trapped was separated from un-trapped substrate by denaturing PAGE [10% (w/v)] at 200 V for 1 h. The experiments were performed in triplicate showing the same result.

MALDI-TOF–MS analysis of U-DNA digested by hSMUG1 in normal water or H218O

Reaction mixtures containing hSMUG1 (0.3 pmol) together with (re-suspended) unlabelled substrate 2 (normal H216O experiments, 10 pmol; H218O experiments, 20 pmol) were incubated in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 70 mM KCl at 37°C for 30 min (normal H216O experiments; final volume, 20 μl), or 1 h (H218O experiments; final volume, 10 μl), if not otherwise stated. Control incubations were performed with EcUng (0.78 pmol) plus either hOGG1 (13 pmol), EcNth (8.7 pmol) or EcFpg (17 pmol) to compare the hSMUG1-generated 3′-end product with those of characterised enzymes. MALDI-TOF–MS analyses on reaction products were carried out as described (34). Substrate DNA was evaporated using vacuum centrifugation followed by re-suspension in H218O (Aldrich, Product No. 329878; 20 μl). The 18O-labelling of the enzymatic products was performed by dissolving them in H218O followed by incubation at 4°C overnight. The MS was performed as above, but with H218O replacing H216O in every step. DNA was precipitated with 96% ethanol, 1 M ammonium acetate and 0.1 μg/μl glycogen followed by incubation at −20°C overnight (for some experiments precipitation was performed as in the experiments using PAGE as described above). DNA pellet was collected by centrifugation at 13 000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C.

Kinetic model calculations

From the calculated concentration [P1] (see Figure 9A) the reaction velocity for the 20 min assay was calculated as

|

where [P1]20 denotes the concentration of P1 after 20 min. The rate equations of the model were solved numerically by using the Fortran subroutine LSODE (35) in conjunction with Absoft's Pro Fortran compiler (www.absoft.com) with a (model) simulation time of 20 min. From the numerical output, graphs were constructed showing Vin in nM/min as a function of the enzyme concentration [E]0 (in nM). For the time-dependent graphs, the concentration-time data for the formation of the incision product P1, the excision product U and substrate DNA (S), were extracted from our previous calculation at the initial [E]0 concentrations of 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2 and 0.25 nM. Plots were generated using gnuplot (www.gnuplot.info) and Adobe Illustrator (www.adobe.com). A detailed description of the model is presented in the Supplementary Data (see A three-phase kinetic model).

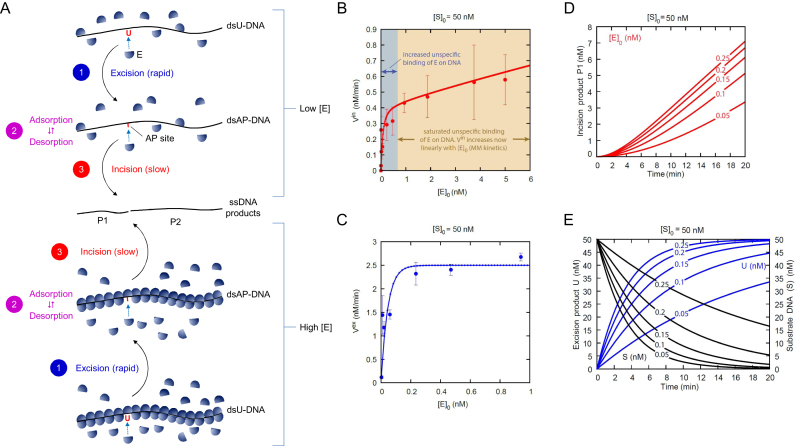

Figure 9.

hSMUG1 kinetics. (A) Three-phase kinetic model. Phase 1 is shown in blue, phase 2 in violet and phase 3 in red. The uracil excision step is rapid compared to the slow DNA incision step. (B) U-DNA incision rate Vin and (C) uracil excision rate Vex (see A) as a function of enzyme concentration [E]0 at an initial U-DNA concentration [S]0 of 50 nM, where the corresponding time-dependent data in the range [E]0 = 0.05–0.25 nM (red line) is presented in (D) showing that at higher initial enzyme (E) concentration the model predicts that the formation of the incision product P1 has linear time-dependent kinetics, and in (E), showing that the excision kinetics for U (blue line) are fast and correlate with the removal of substrate DNA (S; black line), respectively. Incubation was performed for 20 min as described in Figure 4B. The Vin in the blue area changes as a result of increased unspecific binding of enzyme to DNA. In the yellow area, the unspecific binding is saturated and the Vin follows Michaelis–Menten (MM) kinetics. Each value represents the average (±SD) of 3–6 independent measurements.

RESULTS

The presence of hSMUG1 causes cleavage of U-DNA into two different 3′-end products

A common method to determine DNA glycosylase activity employs an oligodeoxyribonucleotide with the damaged base residue (in casu, a uracil) inserted at a specific position. Enzymatic excision of uracil results in an alkali-labile AP site, which can be monitored by the extent that e.g. NaOH cleaves such sites by a β/δ-elimination reaction (36), where cleaved DNA is separated from un-cleaved DNA by PAGE under denaturing conditions (Figure 1A). We incubated such substrate, fluorescently labelled at the 5′ end of the damaged strand (substrate 1), with increasing amounts of hSMUG1. Apparently, protein-dependent cleavage of the DNA at the lesion site took place without alkali (Figure 1B, lanes 4–7), although less than in the samples treated with NaOH (Figure 1B, lanes 8–10). Repeated experiments using different enzyme preparations demonstrated that hSMUG1 removed virtually all uracil residues present in the DNA at the highest protein concentration examined, whereas total strand incision ceased when about ⅔ of the uracils had been removed (Figure 1C). Neither U-DNA incision nor uracil excision occurred without enzyme (Figure 1B, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). It is also important to note, that we always employed reaction conditions without Mg2+ and with EDTA added, to minimise possible contaminating AP endonuclease activity (2), in spite of the fact that UDGs are stimulated by Mg2+ ions (9). In conclusion, hSMUG1 seemed to incise U-DNA at the lesion site.

The major 3′-product generated in the presence of hSMUG1 without alkali treatment, hereafter designated U-DNA incision product (UIP), migrated more slowly than the 3′-phosphate/δ-elimination product formed by NaOH/heat treatment of AP-DNA (Figure 1B). In addition, a product migrating like the 3′-phosphate appeared at higher hSMUG1 concentrations and was designated U-DNA processing product (UPP) (Figure 1B).

AP-DNA converts efficiently to UIP at increased temperatures, which can explain one third of the UIP formed from U-DNA in the presence of hSMUG1

The method employed to determine UDG activity (Figure 1A) is indirect but quantitative since uracil is a stable base in DNA and virtually all AP sites generated is a result of uracil excision. The AP site generated by UDG and other DNA glycosylases is chemically indistinguishable from the AP site formed in cellular DNA by hydrolytic depurination/depyridination (37–39), where the latter is the most abundant DNA lesion in all cells (6). However, this common or normal AP site (as opposed to e.g. oxidised or reduced AP sites) is chemically relatively unstable, also at physiological pH, leading to DNA chain breakage (40). Since this instability increases greatly with temperature, and we denatured the hSMUG1-exposed DNA oligomer for 5 min at 95°C in the presence of formamide to prepare for PAGE (Figure 1A), another possible explanation for the U-DNA incision observed (Figure 1B) is non-enzymatic AP site cleavage caused by this heat treatment (38). Importantly, while NaOH/heat cleaves the AP site into a 3′-phosphate by β/δ-elimination (39), it has previously been shown that the 3′-product formed by thermolysis of AP sites at neutral pH is an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (38). This could imply that the increase in DNA cleavage as a function of increasing protein concentration only reflected the appearance of an increasing number of AP sites made by the increasing amount of hSMUG1 added. Since such non-enzymatic hydrolysis would be a time-dependent process, U-DNA (substrate 1) was pre-treated with Escherichia coli family 1 UDG (EcUng), commonly used for this purpose, to convert the uracil residues into AP sites (Figure 2A). Then, the resulting AP-DNA was exposed to 95°C for different time-periods in the formamide-containing solution employed to denature DNA for PAGE. Parallel samples were also NaOH/heat-treated to determine the amount of AP sites in the substrate (Figure 2B, lane 1). The results show that such non-enzymatic AP site cleavage was significant at 95°C during the 30 min period investigated (Figure 2B, lanes 2–7), where about 80% of the AP-DNA was converted to 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde while <10% to 3′-phosphate/UPP (Figure 2C). Comparing the hSMUG1-incised U-DNA with the 5 min-treated AP-DNA indicates a more efficient generation of UIP from U-DNA by the highest amount of hSMUG1 (Figure 1B, lane 7) than of the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde from AP-DNA by heat (Figure 2B, lane 4). Indeed, both incision of U-DNA with hSMUG1 (Figure 1B) and cleavage of AP-DNA by heat (Figure 2B) show just one clear band at the position of UIP or the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde in PAGE, suggesting that they are chemically identical. Repeated experiments showed an initial rate of incision of ∼4% of the total amount of AP sites in the DNA per min at 95°C (Figure 2C). AP-DNA was also exposed to 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA (TE) and pure water, to investigate whether buffer/solution composition is important for cleavage. The results show that AP-DNA was cleaved similarly in all these three solutions, which amounted to an initial rate of 3.8 ± 0.2% of the total AP sites in the substrate per min (Figure 2D). At 75°C the initial cleavage rate was 0.74 ± 0.02% of the total AP sites in the substrate per min (Figure 2E), also with no difference between the formamide and water solutions. Moreover, at 75°C only UIP (and no UPP) appeared as cleavage product (Figure 2C and data not shown). Importantly, experiments performed at 37°C using the same conditions as above showed no significant cleavage of AP-DNA (Figure 2C). In conclusion, our experiments show that non-enzymatic hydrolysis of AP-DNA at neutral pH increases significantly with temperature and generates the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde as cleavage product, which accords with previous results (38). The effect of the buffer composition seemed to be minimal. We only observed UPP as a minor product arising at 95°C (Figure 2C).

The significant hydrolysis of AP sites to the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde at 95°C, which migrated in PAGE as UIP (Figure 2B), seemed to challenge the interpretation of the original experiments which indicated hSMUG1-catalysed incision of U-DNA at the lesion site (Figure 1B). However, this chemical decay of (hSMUG1-generated) AP sites during the 5 min heat treatment for sample preparation was easily measured and quantified to 19.2 ± 0.8% of the total number of AP sites in the sample DNA (Figure 2D); the latter measured by NaOH/heat-mediated cleavage of product DNA exposed to each hSMUG1 concentration. Since we routinely analysed samples treated with and without NaOH in parallel (Figure 1A), the number quoted was calculated from the former to be subtracted from the latter. As stated in the previous section, no separation of the chemically formed 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde and the ‘enzymatically’ formed UIP was ever observed (Figure 1B and data not shown) indicating molecular identity. Thus, the apparent incision measured as increasing as a function of hSMUG1 concentration [Figure 1C; U-DNA incision (total)] had to be adjusted for this non-enzymatic background incision to show the true estimate of the hSMUG1-catalysed protein-dependent incision of U-DNA [Figure 1C; U-DNA incision (enzymatic)]. This was only about two or three times lower than the uracil excision at comparable enzyme concentrations.

Indirect identification and the time-dependent formation of UIP and UPP from U-DNA in the presence of hSMUG1

At the beginning of our study we observed (Figure 1B) that UIP migrated more slowly during PAGE than the 3′-phosphate formed by NaOH-mediated incision of AP sites (36). UIP also seemed to migrate like the 3′-product formed by non-enzymatic hydrolysis of AP sites in the presence of formamide at high temperature (Figure 2B), previously identified as 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (38). In contrast, UPP migrated like 3′-phosphate (Figure 1B). To try identifying both species, U-DNA exposed to hSMUG1 for different time periods was analysed together with 3′-incision products made by other known AP site-incising enzymes under PAGE conditions favouring separation of different end products, which has been a common method to identify the nature of such DNA ends resulting from incision of AP sites by BER enzymes. To increase the visibility and amount of UPP, which in our first experiments appeared as a minor product (Figure 1B), the U-DNA was radioactively labelled. To make chemically characterised 3′-end products, U-DNA (substrate 1) was pre-treated with EcUng to convert uracil into an AP site followed by treatment with either (a) E. coli endonuclease III (EcNth) to define a 3′-dRP formed by β-elimination (41), (b) E. coli endonuclease IV (EcNfo) to define a 3′-OH (42), (c) E. coli formamidopyrimidine–DNA glycosylase (EcFpg) (43) to define a 3′-phosphate formed by β/δ-elimination (δ-product; also formed by NaOH/heat as mentioned above) or (d) human 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (hOGG1) to define the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (41,43). As expected, the result showed that UIP migrated differently from the products defined by the enzymes EcNth, EcNfo and EcFpg, but identical to the product formed by hOGG1 (Figure 3A), i.e. like the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde. Since, as indicated before, this product also is formed by thermolysis of AP sites at neutral pH (38), the result can explain our observations. As expected, also UPP migrated differently from the products defined by the enzymes EcNth, EcNfo and hOGG1, but identical to the product formed by EcFpg, i.e. like a 3′-phosphate (Figure 3A).

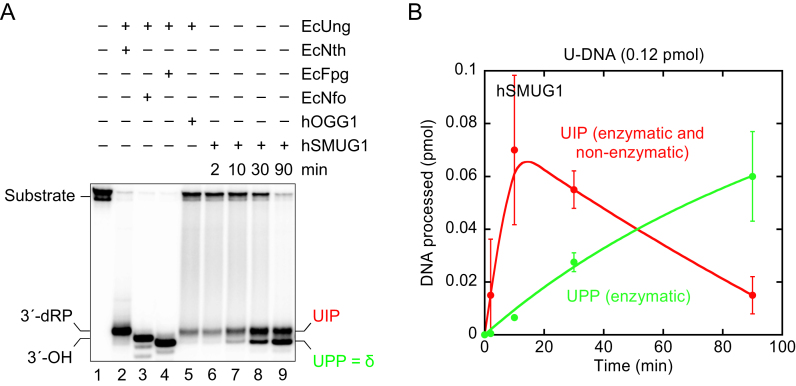

Figure 3.

Indirect identification of UIP and UPP by electrophoretic mobility using conventional denaturing conditions. (A, B) Time dependence of UIP (red) and UPP (green) formation by hSMUG1. hSMUG1 (0.3 pmol) was incubated with substrate 1[32P] (0.12 pmol) in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 70 mM KCl at 37°C. To define the different 3′-end products, substrate was incubated with either EcNth (8.7 pmol), EcNfo (0.16 pmol), EcFpg (17 pmol) or hOGG1 (13 pmol) together with EcUng (0.78 pmol) for 10 min. Incised was separated from un-incised DNA by denaturing PAGE. Each value in B represents the average (±SD) of three independent measurements.

Besides indicating the chemical nature of UIP and UPP, the experiment presented in Figure 3A also shows significant formation of UPP by prolonged incubation with hSMUG1, becoming similarly abundant as UIP after incubation for 30 min or more (lanes 8 and 9). Indeed, after 90 min UPP was at least three times as abundant as UIP (Figure 3B). This contrasts with the negligible amount of UPP formed by thermal degradation of AP-DNA even at the highest temperature examined, with ∼1% after 10 min and ∼6% after 30 min at 95°C (Figure 2C). Thus, sample preparation for 5 min at 95°C should hardly form detectable amounts of UPP (Figure 2B and C). This accords with the above cited results which identified UIP/3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde as the major product generated by thermolysis at neutral pH, and also showed that UIP needs prolonged incubation at high temperature to be converted significantly to UPP (38). Since the efficient formation of UPP in the presence of hSMUG1 (Figure 3) cannot be explained by thermolysis of AP sites or UIP, the only interpretation left is that it is generated by hSMUG1; either as a second ‘U-DNA incision product’ or by processing of UIP. When U-DNA pre-incised by hSMUG1 was incubated with hAPE1, all UIP converted into 3′-OH product (Supplementary Figure S1), showing that UIP is processed by the BER pathway.

U-DNA incision by hSMUG1 confirmed under conditions of no significant spontaneous AP-DNA incision

To minimise spontaneous incision of AP sites in DNA during sample preparation for denaturing PAGE, we decided to try avoiding exposure to high temperature and instead treat the enzymatically exposed DNA (substrate 1) with PAGE loading solution/formamide at room temperature, in addition to adding formamide to the gel (Figure 4A). Using no temperature above 37°C, hydrolytic incision of AP sites should be minimal (Figure 2C). Somewhat surprising, the result showed that this treatment was sufficient to release the 20 nt 5′-incision product from the un-incised DNA (Figure 4B), confirming the ability of hSMUG1 to cleave DNA at the uracil site in a protein-dependent manner (Figure 4C).

hSMUG1 was also incubated with single-stranded U-DNA (ssU-DNA; the labelled strand of substrate 1; Figure 1A) under similar conditions as described above for double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). The result showed that the enzyme incised ssU-DNA (Figure 5A) in a protein-dependent manner within the same order of magnitude (Figure 5B) as dsDNA (Figure 4C). This differs from AP lyases which exhibit low activity for ssDNA (2), thus minimising suspicion of contamination of the hSMUG1 preparation by such activity.

Figure 5.

hSMUG1 incises at uracil in ssDNA. (A, B) Protein dependence of U-DNA incision (red) and uracil excision (blue). hSMUG1 was incubated with ssU-DNA (1 pmol; the labelled strand of substrate 1) at 37°C for 10 min. Each value in B represents the average of 2 independent measurements. Incision product was separated from un-incised DNA by PAGE at 100 V for 50 min using a 12% (w/v) gel with 3% (v/v) formamide.

Confirmation of hSMUG1 incision activity by freshly prepared enzyme preparation using different buffers

To improve the experimental evidence for the novel hSMUG1 enzyme functions, we overexpressed a truncated version of the human SMUG1 gene and purified the corresponding catalytically active hSMUG(25–270) protein [Supplementary Data, Production of purified hSMUG1(25–270) and Supplementary Figure S2]. The results confirmed the previous findings by demonstrating a U-DNA incision and processing activity and uracil excision activity of hSMUG(25–270) (Figure 4D and E) similar to the commercial hSMUG1 preparation (Figure 4B and C). Considering the higher amounts of enzyme used and the double incubation time the UPP clearly appears in addition to UIP (Figure 4D) as opposed to the other case only showing one product band corresponding to UIP (Figure 4B). The U-DNA incision (comprising both UIP and UPP) as compared to the uracil excision is also higher with hSMUG(25–270) (Figure 4E) than with commercial hSMUG1 (Figure 4C). Besides, the presence of amines in the (HEPES) reaction buffer may lead to cleavage of AP sites in DNA via a β-elimination reaction (44), contributing to a false U-DNA incision activity. To investigate this possibility we compared hSMUG1 activity in HEPES and sodium cacodylate buffer in parallel experiments using otherwise identical conditions. The results showed no significant difference in incision activity between these two reaction buffers, which largely excludes possible artefacts related to reaction buffer composition (Figure 4F).

Sodium borohydride trapping experiments indicate no AP lyase function of hSMUG1

Because our results showed that hSMUG1 formed the same 3′-end products (3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde/UIP and 3′-phosphate/UPP) as certain bi-functional DNA glycosylases like hOGG1 and EcFpg, it was reasonable to investigate whether the enzyme execute catalysis by a similar lyase mechanism or function. Since the imine enzyme–DNA-deoxyribose (Schiff base) intermediate (33) of these glycosylases can be cross-linked to the DNA substrate (substrate 2) following treatment with sodium borohydride, which reduces the double bond of the complex, hSMUG1 reaction mixture was subjected to such treatment where EcFpg was assayed in parallel as a positive control. We performed such experiments with an enzyme concentration lower (Figure 6, left panel) as well as higher (Figure 6, right panel) than the substrate concentration using a 1 h incubation time. The results showed that like hUNG, which we used as a negative control, hSMUG1 did not form such a complex with U-DNA, arguing against the presence of a lyase active site amino residue in hSMUG1. This contrasted with the efficient trapping of AP-DNA as opposed to U-DNA by EcFpg, confirming the potency of the assay.

Indirect identification of UIP and UPP formed by hSMUG1 confirmed under conditions of no significant spontaneous AP-DNA incision

In addition to the indirect identification of UIP and UPP as incision products of hSMUG1 using sample-treatment with formamide at 95°C (Figure 3A), the same result was obtained at conditions using no incubation nor exposure to higher temperature than 37°C (Figure 7). In this case, hUNG rather than EcUng was employed converting U-DNA into AP-DNA while the same enzymes defined the different 3′-incision products, except that hAPE1 defined the 3′-OH and EcNth defined both the 3′-dRP as well as the corresponding 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (see Comment on β-elimination products produced by EcNth and hOGG1 in Supplementary Data). The results (Figure 7) showed that UIP (lane 7) migrates faster than the slowest migrating product defined by EcNth (i.e., 3′-dRP; lane 5), slower than the 3′-OH product produced by hAPE1 (lane 4), and exactly like the fastest migrating 3′-incision product defined by EcNth (lane 5) and by hOGG1 (see Figure 3A, lane 5), which is the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde. The conversion of all substrate into product by incubation of hSMUG1 and EcFpg together (lane 6) verified that the hSMUG concentration employed was sufficient to remove all uracils from the DNA, as hUNG together with EcFpg, used as a control, also did (lane 3). A faint band corresponding to UPP, which migrated as the 3′-phosphate formed by EcFpg, was also observed (lane 7). Consequently, the indirect identification of UIP and UPP without using heat treatment to denature DNA prior to analysis confirmed the previous identification (Figure 3A).

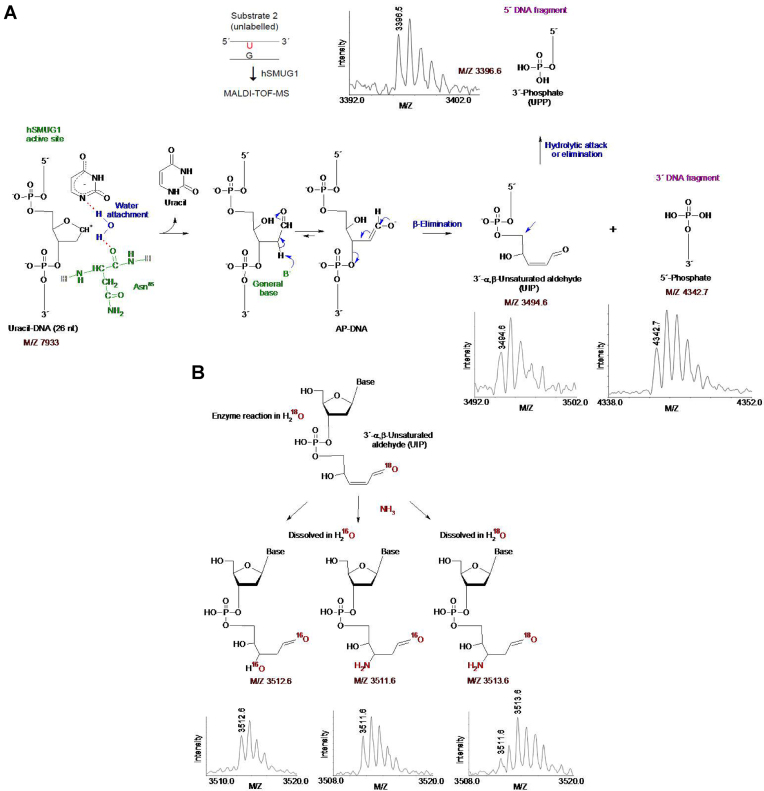

Chemical identification of UIP and UPP formed by hSMUG1 by MALDI-TOF-MS under conditions of no significant spontaneous AP-DNA incision

Although gel electrophoresis is a standard quantitative method for identification of BER cleavage-products, the identification is indirect and does not provide chemical parameters. For this reason, cleavage products of an un-labelled version of substrate 2 formed by hSMUG1 as well as enzymes used to define the different 3′-end products were further investigated using MALDI-TOF-MS analysis. We also performed incubations in solutions made in H218O, to indicate reaction mechanism. Like hOGG1 but different from EcFpg and EcNfo (data not shown), hSMUG1 produced a 5′-DNA fragment of M/Z 3494.6, exactly corresponding to the mass of a fragment containing a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (Figure 8A). Likewise, a signal of M/Z 3512.6 also appeared following enzyme digestion, even though enzyme reactions were carried out in H218O (Figure 8B, left). This indicates post-enzymatic addition of water (which mostly contains 16O) to the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde, since such addition during enzyme reaction (mostly with 18O) should result in a product of M/Z 3514.6 due to a 3′-18OH group. When we precipitated the enzymatically exposed substrate with ethanol in the presence of ammonium acetate, the ‘M/Z 3512.6’ product was absent. Instead, a signal corresponding to M/Z 3511.6 appeared, which can be explained by quantitative addition of ammonia to the double bond of the 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (Figure 8B, middle). When the reaction products were dissolved in H218O instead of normal water, the M/Z 3511.6 signal decreased in favour of a signal corresponding to M/Z 3513.6, which accord with the presence of an aldehyde group at C1′ (Figure 8B, right). Aldehydes are subject to exchange of oxygen isotopes by addition-elimination of water. Thus, in addition to directly identifying a fragment with the same molecular weight as if it contains a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (Figure 8A), the results also demonstrated two possible post-enzymatic derivatives of such a product (Figure 8B). This confirms the presence of a double bond and provides compelling evidence that the 5′ incision fragment formed by hSMUG1 is indeed a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde. MALDI-TOF-MS also showed that all incubations with hSMUG1, like all those with EcFpg (data not shown), produced a signal corresponding to M/Z 3396.6 (Figure 8A), exactly corresponding to the mass of a 5′-DNA fragment containing a 3′-phosphate. This provides compelling evidence that UPP formed by hSMUG1 (Figures 1B, 3A and 7), first identified by migrating as the β/δ-elimination product defined by EcFpg in PAGE (Figure 3A), is indeed a 3′-phosphate. We observed a signal with M/Z 4342.7 in all experiments, regardless whether or when we used 18O- or 16O-water or ammonium-based precipitation. This M/Z value corresponds to a 3′-fragment containing a 5′-phosphate end (Figure 8A). We did not observe any signal corresponding to a 5′-fragment containing a 3′-dUMP, which indicates that the formation of UIP follows uracil excision (Figure 8A). We also did not observe any signal corresponding to the masses of UIP or other possible U-DNA incision or processing products in control incubation without repair enzyme (Supplementary Figure S3). Finally, we observed a signal of M/Z 3316.5 corresponding to a 3′-OH when substrate subjected to hSMUG1 was further incubated with hAPE1 (Supplementary Figure S4), as previously demonstrated by PAGE (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 8.

Chemical identification of UIP and UPP and working model for reaction mechanism causing DNA incision. (A) Proposed E2 elimination reaction for the formation of UIP and chemical identification of UIP and UPP by MALDI-TOF-MS (see Supplementary Data, Figure S3 for MALDI-TOF-MS controls). hSMUG1 amino acid residue(s) suggested being involved in catalysis are coloured green; their hydrogen bonds with catalytic water and substrate are shown by red dotted lines. Proposed electronic and proton transfers involved in the formation of UIP are indicated by blue arrows. In the case of UPP, no reaction mechanism is proposed, and it is still unclear whether it is formed directly as a result of incision or by processing of UIP as depicted here. (B) Confirmation of the chemical nature of UIP. The observed post-enzymatic addition of water (left) or ammonia (middle and right) can be explained by the presence of a conjugated double bond, while the efficient exchange of an oxygen atom when the sample was transferred between 18O- and 16O-water can be explained by the presence of an aldehyde group. The MALDI-TOF-MS signals of the different chemical structures are shown in the upper and lower panels in A, and in the lower panel in B.

Kinetic model

To describe hSMUG1 excision and incision activity we compared and adapted the experimental data to a three-phase kinetic model (Figure 9A; see Materials and Methods and Supplementary Data), which agrees well with the measured U-DNA incision and uracil excision rate (Figure 9B and C, respectively). Phase 1 involves an initial rapid recognition and excision of uracil to form AP-DNA (Figure 9A, upper and lower panels). Phase 2 is a slower adsorption/desorption phase where hSMUG1 (E) binds non-specifically at different sites on DNA establishing a dynamic equilibrium (steady state) including the AP site to be cleaved. Phase 3 includes the incision of the AP site and depends on the enzyme concentration. While the rapid increase in incision velocity occurring at low initial concentrations (Figure 9B) can be explained by rapid re-binding to AP site after uracil excision (Figure 9A and B, low [E]0), the much slower increase in incision rate at high initial concentrations (Figure 9A and B, high [E]0) now depends on the bulk (free in solution) enzyme concentration and follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics (Vin becomes now linearly dependent with respect to [E]0, Figure 9B), because only binding to the AP site causes incision. In agreement with the assumption that excision is a rapid process the excision rate Vex follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics as seen experimentally (Figure 9C). Figure 9D and E show concentration time plots for incision product P1 and excision product U when initial substrate concentration is 50 nM and the initial enzyme concentration varies in the range 0.05 nM to 0.25 nM. It is seen that during the 20 min incubation time most of the substrate S is transformed into excision products, while only a fraction of S forms incision products. The model resulted in a KD of 0.0001 nM, a  of 200 min-1 for uracil excision and a

of 200 min-1 for uracil excision and a  of 0.2 min-1 for U-DNA incision (Table 1; see A three-phase kinetic model in Supplementary Data). Also, for higher initial DNA concentration (125 and 375 nM) a good agreement between experimental and model data was found (Supplementary Figure S5A and B, respectively).

of 0.2 min-1 for U-DNA incision (Table 1; see A three-phase kinetic model in Supplementary Data). Also, for higher initial DNA concentration (125 and 375 nM) a good agreement between experimental and model data was found (Supplementary Figure S5A and B, respectively).

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of the U-DNA incision as compared to the uracil excision activity of hSMUG1

| [E]0 (nM) | [S]0 (nM) | KD (nM) |

(min−1) (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0035–7.5 | 50, 125, 375 | 0.0001 | 0.2 |

| 0.0035–7.5 | 50 | 0.0001 | 200 |

U-DNA incision activity is in red; uracil excision activity is in blue. Kinetic constants were determined by ‘eye-balled’ fit simulation of the adsorption isotherms of the saturation curves in [E]0 (see Supplementary Data, A three-phase kinetic model, Equations (9) and (13); k1 = 1.5 nM−1 min−1, k2 = 0.002 nM−1 min−1) (35).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we demonstrate, that the family 3 UDG hSMUG1–hitherto regarded as a mono-functional DNA glycosylase–incises the phosphodiester backbone of U-DNA at the lesion site after uracil has been excised (Figures 1B and 4B). The activity is dependent on that the uracil base itself is recognised by the enzyme, since no significant activity was detected on AP site-containing DNA (data not shown), which encouraged us to call the 3′-incision product UIP. Judged from migration behaviour in gel electrophoresis hSMUG1 seemed to form the same 5′-fragment as the major fragment formed by hOGG1 (Figure 3A) as well as one of the fragments produced by EcNth (Figure 7; see Comment on β-elimination products produced by EcNth and hOGG1 in Supplementary Data). This ends with a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (Figure 7), and is exactly the same product as formed by thermolysis of AP-DNA at neutral pH (Figure 2B) (38). In addition to UIP, which is the major product formed by hSMUG1, the enzyme also forms a minor product (Figure 1B), which becomes a major product, following extended incubation times (Figure 3A), which we decided to call UPP. UPP migrated in PAGE as the β/δ-elimination product formed by EcFpg (Figures 1B and 3A).

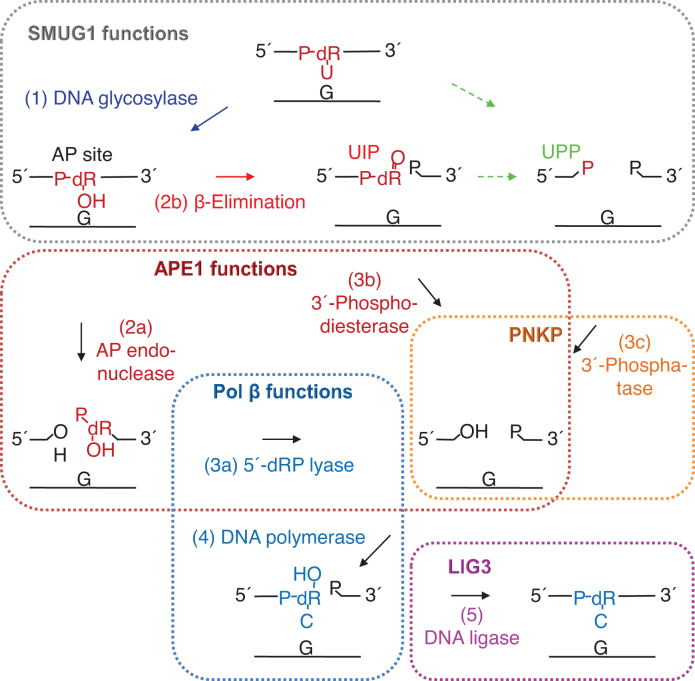

Subsequent MALDI-TOF-MS analyses of hSMUG1-exposed U-DNA using the same 3′-end-defining enzymes as positive controls confirmed the indirect identification by PAGE of both UIP and UPP. Thus, the molecular mass of UIP corresponded exactly to the presence of a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde, while the molecular mass of UPP was identical to the mass of a 3′-phosphate (Figure 8A). Both UIP and UPP are known products of bi-functional DNA glycosylases shown to be processed in vitro to 3′-OH by hAPE1 (Supplementary Figures S1 and S4) and hPNKP, respectively (28), which suggest efficient downstream processing in vivo by priming the nick for deoxycytidine monophosphate (dCMP) insertion and ligation (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Proposed steps in the human BER pathway after SMUG1 has targeted uracil in DNA. After uracil has been removed by the DNA glycosylase activity of SMUG1 (step 1; blue), the latter is either replaced by APE1 (dark red) which incises the AP site (step 2a), or SMUG1 itself incises the AP site (step 2b; red) leaving behind a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (UIP) which can be removed by APE1 (step 3b). Further processing of UIP (or maybe an alternative type of incision of the AP site; green broken arrows) results in a 3′-phosphate (UPP) which is a substrate for PNKP (orange). The cleaned one nucleotide gap in DNA is now ready for insertion of the correct dCMP (step 4) by the repair DNA polymerase β (Pol β; dark blue), which also exhibits the dRP lyase activity which removes the 5′-dRP remnant (step 3a) after APE1 incision. BER is concluded by nick-sealing (step 5) by DNA ligase III (LIG3; purple). The residues removed are indicated in dark red; those resulting from replacement in dark blue; dR, deoxyribose.

Opposed to the ability of the gel analysis, the MALDI-TOF-MS results also showed the presence of a 5′-phosphate on the 3′-fragment completing the analysis of the hSMUG1-processed U-DNA (Figure 8A). Enzyme reactions performed in the presence of H216O and H218O (Figure 8B) were consistent with a β-elimination reaction mechanism. However, the failure to trap a UDG–DNA reaction intermediate as a stable covalent complex (Figure 6) and the fact that hSMUG1 lacks an active site lysine (15,17,18) to carry out a β- or a β/δ-elimination reaction indicates that the excision and incision activities are not concerted. We propose that incision occurs in two steps. In the first step, the cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond may be similar to the SN1-like mechanism of hUNG (45,46), where stereo-electronic effects lead to the formation of a uracil anion and an AP site with a positively charged C1′. In the second step, a β-elimination reaction can occur by deprotonation of the deoxyribose C2′ and the formation of an enolate intermediate at the formyl group (Figure 8A). However, the general base necessary for the C2′ deprotonation as well as a way to stabilise the enolate intermediate need to be specified.

The crystal structure of Xenopus laevis SMUG1 (xSMUG1) has been determined and together with its amino acid sequence compared to other members of the UDG superfamily (15,17,18). Human and amphibian SMUGs share high level of sequence similarity in the catalytic active site. Since hSMUG1 has not been crystallised together with substrate, its similar organisation of the active site as other members of the UDG superfamily like the much studied hUNG suggests comparisons with the latter, especially hUNG crystals with substrate (14,47). One of the original models for catalysis by family 1 UDGs suggested an associative SN2 mechanism, which shortly says that following flipping into the active site uracil is released from deoxyribose by attack on the C1′ of a water molecule activated by an Asp residue acting as a general base (Asp145 in hUNG, with possible assistance from His148) (14,30,48). In contrast, later results supported by biophysical investigations have favoured a dissociative SN1-like mechanism, which means that following base flipping into the active site the glycosidic bond splits into a uracil anion stabilised by a histidine residue and a deoxyribose oxocarbenium ion (45). Then, a water molecule, coordinated by certain active site amino acid residues, somewhat passively becomes the 1′-α-OH C1′ after dissociation of the uracil anion (45). While the SN2 approach focuses on the activation of a H2O nucleophile by certain amino acid residues (14), the SN1 model emphasises the reaction energy contributed by molecular strain or other unfavourable atomic clashes in U-DNA before and following base flipping (47). Because hSMUG1 contains the nonpolar Asn85 unable to activate H2O (for nucleophilic attack or elimination) in place of the activating Asp145 of hUNG (46), the SN1-like mechanism might appear applicable for hSMUG1 as well (18). That may explain the observation that the U-DNA excision activity of hUNG is more effected by replacement of Asp145 than the activity of hSMUG1 is effected by replacement of Asn85 (17,18). If we, being conscious about our limitations at the present stage of knowledge, assume a similar SN1-like reaction intermediate for hSMUG1 as shown for hUNG, Asn85 of hSMUG1 can be assigned to coordinate the reactive water molecule to attach the deoxyribose oxocarbenium ion, and that the events occur in a non-concerted manner via the activation of the uracil anion. In the crystal structure of xSMUG bound to free uracil, the backbone carbonyl group of Asn96 (corresponds to Asn85 of hSMUG1) coordinates water by a hydrogen bond (Figure 8A).

A β-elimination reaction at the C2′–C3′ bond accords with the direct formation of UIP from the abasic sugar. Since the trapping experiment indicated no formation of an imine intermediate (Figure 6), theoretically, the elimination reaction may occur via deprotonation of C2′ leading to formation of the enolate intermediate (Figure 8A), although the O1′ negative charge may require stabilisation. However, in the case of hUNG which also was crystallised together with AP-DNA (49), attachment to the AP site compresses, like ordinary unspecific DNA binding, the DNA backbone to promote nucleotide flipping. Since hSMUG1 binds AP sites much stronger than hUNG (17), such induced strain may contribute to reaction energy. A major limitation of the model is our inability to specifically suggest certain active site residues as e.g. the deprotonating general base and/or the enolate stabiliser, which will require a much more detailed molecular understanding of the interactions of hSMUG1 with AP-DNA than presently available. In the case of UPP, it should be realised that the present data does not clarify whether it is formed directly through strand incision or by processing of UIP (Figure 8A), pointing to an uncertainty of the reaction mechanism not yet settled.

We developed a three-phase kinetic model which predicts rapid uracil excision in phase 1, slow unspecific enzyme adsorption/desorption to DNA in phase 2 and enzyme-dependent AP site incision in phase 3 (Figure 9A). This working model is the result of (failed) attempts to view/model the experimental data by simpler models. Although, in principle, other mechanisms cannot be ruled out, we arrived at the three stage model because non-specific binding of the enzyme on the substrate DNA appears necessary to describe the observed transition of the U-DNA incision rate (Vin) from rapid kinetics (low [E]0) to a less rapid increase at higher [E]0 values (Figure 9B).

Recently it was discovered that hSMUG1 probably is involved in RNA quality control in vivo. Cellular depletion of the enzyme caused accumulation of 5-hydroxymethyluridine in rRNA, and hSMUG1 exhibited activity for 5-hydroxymethyldeoxyuridine, but not uracil, in a single-stranded RNA context in vitro (50). This revelation of the absence of a direct overlap between the DNA and RNA substrates adds to the complexity of substrate recognition and binding by hSMUG1, which together with the different catalytic potentials described here suggest studies on how hSMUG1 interacts and reacts with altered bases in DNA and RNA in parallel.

We conclude that the BER pathway is more dynamic than previously anticipated after showing that hSMUG1 may execute a second incision step following base excision resulting in very toxic strand breaks and blocked 3′-ends, with delayed AP endonuclease-mediated processing in vivo as a consequence (Figure 10). The finding that human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 efficiently binds AP sites and also exhibits AP lyase activity may serve a similar function (51). It is tempting to speculate whether this might be an advantageous alternative under certain cellular stress conditions, to delay the initiation of repair replication. During circumstances of large base damage load, it might be crucial to decrease the number of replication forks to minimise the possibility for genomic collapse. Our findings contribute to the emerging knowledge on how BER is intricately carried out at many levels (52,53). It has also been reported that hAPE1 has a high affinity for and is able to incise—although at an extremely low rate–U-DNA, leaving behind a 5′-terminal dUMP (54). This adds to the dynamic and complexity of U-DNA repair. Since the relative importance of the AP lyase, AP endonuclease and PNKP functions in BER has been much discussed, and may vary in different species, more studies are needed to establish their roles in vivo and from now also their roles compared to the novel U-DNA incision activity presented here. Lastly we suggest that this activity also may represent a hAPE1-independent nicking of the DNA as a part of the mechanism involved in class-switch recombination and somatic hyper-mutation (20).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank E.C. Ludvigsen and M. Høie for technical assistance, and K.H. Hopmann and K.B. Jørgensen for discussions on enzyme and organic reaction mechanism.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

University of Stavanger; Oslo University Hospital/University of Oslo. Funding for open access charge: University of Stavanger.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993; 362:709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedberg E.C., Walker G.C., Siede W., Wood R.D., Schultz R.A., Ellenberger T.. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2006; 2nd ednWashington, DC: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alexandrov L.B., Nik-Zainal S., Wedge D.C., Aparicio S.A., Behjati S., Biankin A.V., Bignell G.R., Bolli N., Borg A., Børresen-Dale A.L. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013; 500:415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kornberg A., Baker T.A.. DNA Replication. 1992; 2nd ednNY: W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bauer N.C., Corbett A.H., Doetsch P.W.. The current state of eukaryotic DNA base damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:10083–10101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim Y.-J., Wilson D.M. 3rd. Overview of base excision repair biochemistry. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012; 5:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pearl L.H. Structure and function in the uracil-DNA glycosylase superfamily. Mutat. Res. 2000; 460:165–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haushalter K.A., Todd Stukenberg M.W., Kirschner M.W., Verdine G.L.. Identification of a new uracil-DNA glycosylase family by expression cloning using synthetic inhibitors. Curr. Biol. 1999; 9:174–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kavli B., Sundheim O., Akbari M., Otterlei M., Nilsen H., Skorpen F., Aas P.A., Hagen L., Krokan H.E., Slupphaug G.. hUNG2 is the major repair enzyme for removal of uracil from U:A matches, U:G mismatches, and U in single-stranded DNA, with hSMUG1 as a broad specificity backup. J. Biol. Chem. 2002; 277:39926–39936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bjelland S., Seeberg E.. Mutagenicity, toxicity and repair of DNA base damage induced by oxidation. Mutat. Res. 2003; 531:37–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boorstein R.J., Cummings A. Jr, Marenstein D.R., Chan M.K., Ma Y., Neubert T.A., Brown S.M., Teebor G.W.. Definitive identification of mammalian 5-hydroxymethyluracil DNA N-glycosylase activity as SMUG1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276:41991–41997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Masaoka A., Matsubara M., Hasegawa R., Tanaka T., Kurisu S., Terato H., Ohyama Y., Karino N., Matsuda A., Ide H.. Mammalian 5-formyluracil-DNA glycosylase. 2. Role of SMUG1 uracil-DNA glycosylase in repair of 5-formyluracil and other oxidized and deaminated base lesions. Biochemistry. 2003; 42:5003–5012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Darwanto A., Theruvathu J.A., Sowers J.L., Rogstad D.K., Pascal T., Goddard W. 3rd, Sowers L.C.. Mechanisms of base selection by human single-stranded selective monofunctional uracil-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009; 284:15835–15846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Slupphaug G., Mol C.D., Kavli B., Arvai A.S., Krokan H.E., Tainer J.A.. A nucleotide-flipping mechanism from the structure of human uracil-DNA glycosylase bound to DNA. Nature. 1996; 384:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wibley J.E.A., Waters T.R., Haushalter K., Verdine G.L., Pearl L.H.. Structure and specificity of the vertebrate anti-mutator uracil-DNA glycosylase SMUG1. Mol. Cell. 2003; 11:1647–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nilsen H., Haushalter K.A., Robins P., Barnes D.E., Verdine G.L., Lindahl T.. Excision of deaminated cytosine from the vertebrate genome: role of the SMUG1 uracil-DNA glycosylase. EMBO J. 2001; 20:4278–4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pettersen H.S., Sundheim O., Gilljam K.M., Slupphaug G., Krokan H.E., Kavli B.. Uracil-DNA glycosylases SMUG1 and UNG2 coordinate the initial steps of base excision repair by distinct mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35:3879–3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matsubara M., Tanaka T., Terato H., Ohmae E., Izumi S., Katayanagi K., Ide H.. Mutational analysis of the damage-recognition and catalytic mechanism of human SMUG1 DNA glycosylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32:5291–5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krokan H.E., Sætrom P., Aas P.A., Pettersen H.S., Kavli B., Slupphaug G.. Error-free versus mutagenic processing of genomic uracil–relevance to cancer. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2014; 19:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dingler F.A., Kemmerich K., Neuberger M.S., Rada C.. Uracil excision by endogenous SMUG1 glycosylase promotes efficient Ig class switching and impacts on A:T substitutions during somatic mutation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014; 44:1925–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Di Noia J.M., Rada C., Neuberger M.S.. SMUG1 is able to excise uracil from immunoglobulin genes: insight into mutation versus repair. EMBO J. 2006; 25:585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maiti A., Noon M.S., MacKerell A.D. Jr, Pozharski E., Drohat A.C.. Lesion processing by a repair enzyme is severely curtailed by residues needed to prevent aberrant activity on undamaged DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012; 109:8091–8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kohli R.M., Zhang Y.. TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature. 2013; 502:472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weber A.R., Krawczyk C., Robertson A.B., Kuśnierczyk A., Vågbø C.B., Schuermann D., Klungland A., Schär P.. Biochemical reconstitution of TET1-TDG-BER-dependent active DNA demethylation reveals a highly coordinated mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2016; 7:10806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Doetsch P.W., Cunningham R.P.. The enzymology of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases. Mutat. Res. 1990; 236:173–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mol C.D., Izumi T., Mitra S., Tainer J.A.. DNA-bound structures and mutants reveal abasic DNA binding by APE1 and DNA repair coordination [corrected]. Nature. 2000; 403:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li M., Wilson D.M. 3rd. Human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014; 20:678–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wiederhold L., Leppard J.B., Kedar P., Karimi-Busheri F., Rasouli-Nia A., Weinfeld M., Tomkinson A.E., Izumi T., Prasad R., Wilson S.H. et al. AP endonuclease-independent DNA base excision repair in human cells. Mol. Cell. 2004; 15:209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beard W.A., Wilson S.H.. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase β. Biochemistry. 2014; 53:2768–2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mol C.D., Arvai A.S., Slupphaug G., Kavli B., Alseth I., Krokan H.E., Tainer J.A.. Crystal structure and mutational analysis of human uracil-DNA glycosylase: structural basis for specificity and catalysis. Cell. 1995; 80:869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leiros I., Nabong M.P., Grøsvik K., Ringvoll J., Haugland G.T., Uldal L., Reite K., Olsbu I.K., Knævelsrud I., Moe E. et al. Structural basis for enzymatic excision of N1-methyladenine and N3-methylcytosine from DNA. EMBO J. 2007; 26:2206–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bailly V., Verly W.G., O’Connor T., Laval J.. Mechanism of DNA strand nicking at apurinic/apyrimidinic sites by Escherichia coli [formamidopyrimidine]DNA glycosylase. Biochem. J. 1989; 262:581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zharkov D.O., Rieger R.A., Iden C.R., Grollman A.P.. NH2-terminal proline acts as a nucleophile in the glycosylase/AP-lyase reaction catalyzed by Escherichia coli formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase (Fpg) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1997; 272:5335–5341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Douthwaite S., Kirpekar F.. Identifying modifications in RNA by MALDI mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2007; 425:3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Radhakrishnan K., Hindmarsh A.C.. Description and Use of LSODE. 1993; Cleveland, OH: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Report UCRL-ID-113855 Lewis Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bailly V., Verly W.G.. Escherichia coli endonuclease III is not an endonuclease but a β-elimination catalyst. Biochem. J. 1987; 242:565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Manoharan M., Ransom S.C., Mazumder A., Gerlt J.A., Wilde J.A., Withka J.A., Bolton P.H.. The characterization of abasic sites in DNA heteroduplexes by site specific labeling with C-13. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988; 110:1620–1622. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sugiyama H., Fujiwara T., Ura A., Tashiro T., Yamamoto K., Kawanishi S., Saito I.. Chemistry of thermal degradation of abasic sites in DNA. Mechanistic investigation on thermal DNA strand cleavage of alkylated DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994; 7:673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mazumder A., Gerlt J.A., Absalon M.J., Stubbe J., Cunningham R.P., Withka J., Bolton P.H.. Stereochemical studies of the β-elimination reactions at aldehydic abasic sites in DNA: endonuclease III from Escherichia coli, sodium hydroxide, and Lys-Trp-Lys. Biochemistry. 1991; 30:1119–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lindahl T., Andersson A.. Rate of chain breakage at apurinic sites in double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972; 11:3618–3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Darwanto A., Farrel A., Rogstad D.K., Sowers L.C.. Characterization of DNA glycosylase activity by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2009; 394:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Warner H.R., Demple B.F., Deutsch W.A., Kane C.M., Linn S.. Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases in repair of pyrimidine dimers and other lesions in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1980; 77:4602–4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boiteux S., Coste F., Castaing B.. Repair of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells: Properties and biological roles of the Fpg and OGG1 DNA N-glycosylases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017; 107:179–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Steullet V., Edwards-Bennett S., Dixon D.W.. Cleavage of abasic sites in DNA by intercalator-amines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999; 7:2531–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dinner A.R., Blackburn G.M., Karplus M.. Uracil-DNA glycosylase acts by substrate autocatalysis. Nature. 2001; 413:752–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Przybylski J.L., Wetmore S.D.. A QM/QM investigation of the hUNG2 reaction surface: the untold tale of a catalytic residue. Biochemistry. 2011; 50:4218–4227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Parikh S.S., Walcher G., Jones G.D., Slupphaug G., Krokan H.E., Blackburn G.M., Tainer J.A.. Uracil-DNA glycosylase–DNA substrate and product structures: Conformational strain promotes catalytic efficiency by coupled stereoelectronic effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000; 97:5083–5088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Savva R., McAuley-Hecht K., Brown T., Pearl L.. The structural basis of specific base-excision repair by uracil-DNA glycosylase. Nature. 1995; 373:487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Parikh S.S., Mol C.D., Slupphaug G., Bharati S., Krokan H.E., Tainer J.A.. Base excision repair initiation revealed by crystal structures and binding kinetics of human uracil-DNA glycosylase with DNA. EMBO J. 1998; 17:5214–5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jobert L., Skjeldam H.K., Dalhus B., Galashevskaya A., Vågbø C.B., Bjørås M., Nilsen H.. The human base excision repair enzyme SMUG1 directly interacts with DKC1 and contributes to RNA quality control. Mol. Cell. 2013; 49:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Khodyreva S.N., Prasad R., Ilina E.S., Sukhanova M.V., Kutuzov M.M., Liu Y., Hou E.W., Wilson S.H., Lavrik O.I.. Apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site recognition by the 5′-dRP/AP lyase in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010; 107:22090–22095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Parsons J.L., Dianov G.L.. Co-ordination of base excision repair and genome stability. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2013; 12:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Prasad R., Shock D.D., Beard W.A., Wilson S.H.. Substrate channeling in mammalian base excision repair pathways: passing the baton. J. Biol. Chem. 2010; 285:40479–40488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Prorok P., Alili D., Saint-Pierre C., Gasparutto D., Zharkov D.O., Ishchenko A.A., Tudek B., Saparbaev M.K.. Uracil in duplex DNA is a substrate for the nucleotide incision repair pathway in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013; 110:E3695–E3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.