Abstract

Nucleosome disruption plays a key role in many nuclear processes including transcription, DNA repair and recombination. Here we combine atomic force microscopy (AFM) and optical tweezers (OT) experiments to show that high mobility group B (HMGB) proteins strongly disrupt nucleosomes, revealing a new mechanism for regulation of chromatin accessibility. We find that both the double box yeast Hmo1 and the single box yeast Nhp6A display strong binding preferences for nucleosomes over linker DNA, and both HMGB proteins destabilize and unwind DNA from the H2A–H2B dimers. However, unlike Nhp6A, Hmo1 also releases half of the DNA held by the (H3–H4)2 tetramer. This difference in nucleosome destabilization may explain why Nhp6A and Hmo1 function at different genomic sites. Hmo1 is enriched at highly transcribed ribosomal genes, known to be depleted of histones. In contrast, Nhp6A is found across euchromatin, pointing to a significant difference in cellular function.

INTRODUCTION

The nucleosome forms the basic unit of chromatin and is the key element of nuclear DNA organization in eukaryotes (1). The DNA duplex wraps around four histone pairs (H2A–H2B, H3–H4) to form a single nucleosome core particle, as shown in Figure 1A and B (2). Individual histones each comprise three α-helices as well as structured loops and tails. Once assembled, 100 protein–DNA contacts and hundreds of water-mediated contacts stabilize the wrapping of ∼150 bp into ∼1.7 left-handed turns around the octamer core. While compacted core particles are believed to inhibit access to genomic DNA, a ‘beads on a string’ arrangement of core particles separated by linker DNA allows various nuclear proteins, including transcription factors, to bind. Although this wrapped structure may be highly dynamic (3), initial transcription factor binding may also require weakening of histone–DNA contacts.

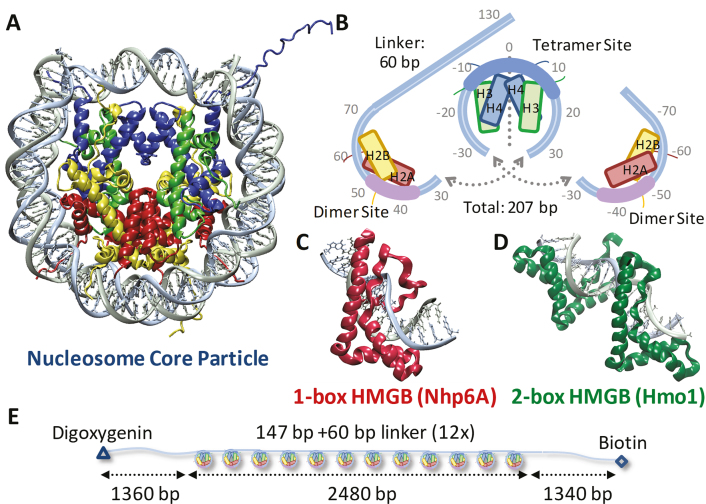

Figure 1.

Experiments probe histone–DNA interactions. (A) DNA wraps ∼1.7 left-handed turns around the histone octamer. (PDB code: 1aoi) (B) Nucleosome arrays consist of twelve repeats of this 11-nm diameter core particle (147 bp) and adjacent 20 nm long (60 bp) linkers. The bases are numbered from the dyad axis (dotted line) in this split image, which stacks vertically from left (top) to right (bottom). Helix-strand-helix structures of individual histones are represented by boxes aligned with each strand. At the dyad axis, the (H3–H4)2 tetramer binds up to 80 base pairs as the central region of DNA bound most strongly is shown in cyan. Off-dyad bases of the outer turns are bound to the H2A–H2B dimers across interactions distributed over the whole length of the outer turn DNA where the bases bound most strongly are highlighted in pink (26,47). (C) S. cerevisiae protein Nhp6A consists of a single L-shaped HMGB domain with an unstructured cationic N-terminus. (PDB code: 1j5n) (8) (D) NMR structure of recombinant HMGB protein thought to resemble S. cerevisiae Hmo1 bound to DNA, drawn to scale with (A) and (C). (PDB code: 2gzk) (7) Two HMGB domains (the second is in the foreground) are connected by a linker and flanked by a C-terminal domain believed to facilitate protein dimerization (not shown). Both Hmo1 and Nhp6A engage the DNA minor groove inserting the aromatic residues between its base pairs, thereby inducing strong bending in the helical axis of ∼90° toward the major groove (9,10). Unstructured tails are thought to play a role in charge stabilization inside that bend. (E) Arrays for AFM and OT experiments consist of twelve repeats of the 147-bp Widom 601 sequence with 60-bp linker, flanked by two ∼1350-bp non-nucleosomal sequences derived from plasmid pUC19 to serve as handles, labeled for attachment.

HMGB proteins are known to expedite transcription by reorganizing chromatin and facilitating the binding of various transcription factors, although the mechanism by which they do so is unclear (4–6). HMGB proteins consist of one or two L-shaped DNA-binding structural motifs encoded by ‘HMG boxes.’ HMGB proteins bind into the DNA minor groove, often without sequence specificity, strongly bending the DNA double helix primarily through weakly intercalating aromatic residues. Both the single box Nhp6A and the double box Hmo1 from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Figure 1C and D), are known to bind to B-form DNA with high affinity, and their binding and unbinding increases the apparent local flexibility of DNA, suggesting possible mechanisms for nucleosome destabilization (7–12). For example, HMGB proteins might bind directly to DNA in the nucleosome core particle, disrupting histone contacts leading to DNA unwrapping and perhaps histone sliding.

Here we study an array of twelve nucleosomes reconstituted using human histone octamers onto Widom 601 sequences separated by segments of linker DNA, as shown in Figure 1E. Although histone sequences are highly conserved, human nucleosomes are somewhat more stable than yeast nucleosomes, facilitating analysis (13). We probe the effects of S. cerevisiae Nhp6A protein on the structure and stability of reconstituted human nucleosomes to uncover general principles that transcend species-specific effects. We analyze the reconstituted array in the presence of wild type yeast HMGB proteins, either the single box Nhp6A or the double box Hmo1. In previous work, we established that both proteins bind to and induce changes in the apparent flexibility of double-stranded DNA, while facilitating DNA compaction (9,10). Here, we see that even below the concentrations required for DNA binding, these HMGB proteins bind directly to the nucleosomes, leading to the disruption of histone–DNA contacts. AFM images of these assemblies in the presence of HMGB proteins reveal dispersion of the core particles due to DNA unwinding. Optical tweezers (OT) experiments directly measure nucleosome destabilization by HMGB proteins and confirm that HMGB proteins disrupt stabilizing histone–DNA contacts within the nucleosome array. Both the double box Hmo1 and the single box Nhp6A destabilize nucleosomes, disrupting DNA-histone contacts in a manner expected to facilitate transcription factor binding. Both HMGB proteins partially disrupt DNA interactions with the H2A–H2B dimers that stabilize the outer turn of DNA. Furthermore, Hmo1 completely breaks the DNA-histone contacts with one of the H2A–H2B dimers, releasing half of the inner turn of DNA from the H3–H4 tetramer. These results point to distinct cellular functions for these two nucleosome-destabilizing HMGB proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nucleosome arrays

The basic unit of the DNA array of Figure 1E consists of a 147-bp nucleosome positioning ‘601’ sequence first identified by Widom (14). Each ‘601’ sequence is followed by a 60-base pair linking sequence to form a 207-base pair repeat unit. Twelve such repeat units, inserted in tandem into plasmid pUC19, create a construct termed ‘601–207 symmetric-12’. Cleaved plasmids (BsaI) linearize the construct and leave the 12× array flanked by ∼1350 non-nucleosomal DNA as long flanking handles for optical tweezer (OT) experiments. Restriction endonuclease digestion leaves a four-base overhang repaired by the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I in the presence of dNTPs including digoxygenin-tagged dUTP and biotinylated dATP to add these labels to opposite DNA termini (Figure 1E). Nucleosome arrays are reconstituted onto these DNA templates as previously described (15,16). Briefly, octamers are deposited onto the DNA at high concentrations in a small volume dialysis button (Hampton Research), and arrays are assembled during salt titration (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH7.5, 1 mM EDTA, with Na+ decreasing from 2 M to 2.5 mM over a period of several hours). Reconstituted arrays, stored in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, and 2.5 mM Na+, are stable for several weeks at 4°C. Array stability for each batch of reconstitutions is scrutinized with AFM and used across these AFM and OT experiments to verify reproducibility at varying concentrations.

HMGB protein preparation

Recombinant HMGB proteins are expressed and purified as described previously (17). Untagged recombinant yeast Nhp6A protein is expressed in bacteria and purified by HPLC. In the case of Hmo1, an N-terminal hexahistidine affinity tag is removed using an immobilized thrombin reagent as described by the manufacturer (Thrombin CleanCleave, Sigma). Briefly, 200 μl immobilized thrombin is used per mg fusion protein in 1 mL cleavage reactions incubated at 24°C for 16 h. Protein is then further purified by size exclusion chromatography in phosphate buffered saline on a Superdex 200 10/30 column eluted at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. Desired fractions are pooled, dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and concentrated. Proteins are stored at −20°C in this dialysis buffer and supplemented with 50% (v/v) glycerol.

AFM measurements

AFM surfaces are prepared as described previously (18). Freshly cleaved mica (Ted Pella) surfaces mounted on 12 mm metal disks are placed facing downwards in a desiccator filled with argon gas. These surfaces are exposed to vapors of 3-Aminopropyltriethoxy silane (APTES, Sigma) and N, N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, Sigma) for several hours. Nucleosomes are diluted into an experimental buffer of 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.25 mM EDTA, 7.5 mM NaCl. A solution of ∼0.1 nM nucleosome arrays with varying protein concentration is incubated on the AP-mica surface for 10 minutes. Nucleosomes are imaged in this fluid with a Scanasyst mode AFM (Bruker Multimode) using a Scanasyst-fluid+ 150 kHz silicon nitride probe (Bruker). The Scanasyst mode is a peak-force tapping technique, that uses feedback to minimize lateral and normal forces on the sample. The tip is oscillated well below resonance, and the peak-force is fixed by an algorithm to minimize tip damage as well. Experiments are performed at room temperature. Each reconstitution is characterized using height threshold of 4–5 nm to allow each nucleosome core particle to be identified while minimizing background signal. This process is repeated in varying concentrations of Hmo1 and Nhp6A, while maintaining the same threshold, to determine protein-induced changes in the conformations of the nucleosome arrays, as previously demonstrated for other protein–DNA complexes (19,20).

Optical tweezers (OT) experiments

The layout of the counter-propagating beam OT experiments has been described elsewhere (21). Briefly, as shown in Figure 1E, a 2.1-μm diameter anti-digoxygenin coated bead (Spherotech) is immobilized on a micropipette tip (WPI), while a 5.4-micron diameter streptavidin-coated bead (Bangs Labs) is held within the dual laser trap (Lumics). Arrays are directionally fixed between the two beads in a solution of 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl and 0.03 nM arrays. Experiments are also conducted in the AFM buffer of 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.25 mM EDTA, 7.5 mM NaCl for direct comparison. Nucleosomes should be stable over the timescales of these experiments in either solution, though there is some finite rate of outer turn breathing (22). The pipette tip is moved to create cycles of increasing extension and then release of nucleosome arrays. The pulling speed corresponds to a loading rate of 10 pN/s, though this value varies slightly with increasing force. Experiments are performed on nucleosome arrays and repeated for assembled arrays exposed to solutions containing yeast Hmo1 or Nhp6A proteins, as discussed in the text. The experimental concentrations of 1 nM Hmo1 and 5 nM Nhp6A approximately match the concentrations where unwrapping was observed to be maximized in the AFM experiments (chosen to favor a strong likelihood of observing saturated protein binding).

RESULTS

AFM images quantify nucleosome dispersion and compaction

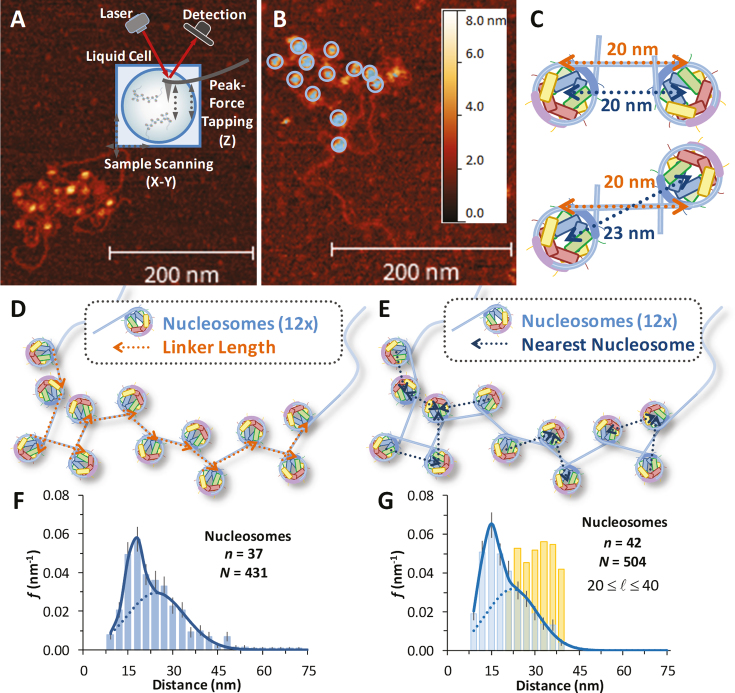

Typical AFM images of reconstituted nucleosome arrays obtained in liquid are shown in Figure 2A and B. Core particles are readily identified in the images, characterized by a height of ∼6 nm and a diameter of ∼11 nm (Supplementary Figure S1 for a detailed height profile). Long, nucleosome-free flanking handles of 1400 base pairs (∼500 nm, see Figure 1E) are also evident, though the DNA linking each nucleosome is not clearly resolved. To characterize nucleosome arrays in these images, twelve core particles are identified using a height threshold of ∼5 nm (Figure 2B), and for each particle the center-to-center distance to each nearest neighbor is determined. These center-to-center distances are meant to recover the linker lengths, assuming a geometrical correction for flipped nucleosomes (Figure 2C). However, a schematic of a 2D array quickly shows that only a fraction of the center-to-center lengths correspond to the length of the linker DNA (Figure 2D and E). We compile histograms of the measured distances across several arrays (n) and fit the total number of distances (N) to a dual Gaussian function (Supplementary Methods 1). A set of arrays are shown and fit in Figure 2F. This analysis is coupled with a simple model that randomly places nucleosomes on a 2D surface with some variation allowed in the linker length (Supplementary Methods 2 and Supplementary Figure S2). This model matches the data well and shows that the two distributions arise from two distinct inter-nucleosome arrangements on the mica surface. Longer distances correspond to sequential nucleosomes along the array. These nearest neighbors are separated by 60 base pair segments of linker DNA, which are stiff due to the ∼150 bp persistence length of duplex DNA (Supplementary Methods 3). Non-sequential core particles account for the shorter inter-nucleosome distance distributions in the folded arrays due to some DNA-nucleosome unwinding and to the random flexibility at the exit-entry points, leading to its two-dimensional folding on the AFM surface. Furthermore, though some DNA is unwound and there is some heterogeneity in the linker length likely due to thermal fluctuations and natural unwinding (22), we find an average linker length of 24 ± 5 nm.

Figure 2.

AFM images of nucleosome arrays and measurements of core particle spacing. (A) AFM image of reconstituted nucleosome array in liquid. Scale bars on all images indicate 200 nm length and colors give height scale up to 8 nm. High resolution images show nucleosomes to be ∼11 nm in diameter and 5 nm in height, consistent with the known structure. (B) Height profiling (∼5 nm) identifies each core particle, highlighted here by 12× rings. As the connecting DNA is not clearly observable, arrays are analyzed by identifying each nucleosome and measuring the distance to its nearest neighbor. (C) Linker lengths of 20 nm (gold) lead to two measured center-to-center lengths (blue) depending upon nucleosome orientation. (D) Schematic of numerically modeled 12× array where the linker DNA (gold arrows point along the array) is described in the text and Supplementary Figure S2. (E) Identifying the center-to-center distance for each nearest neighbor recovers a set of lengths shown (blue arrows point to the nearest neighbor). Some blue arrows point parallel to the linking DNA, while others point to non-sequential neighbors. (F) Histogram of measured nearest neighbor distances (x) for several arrays (n = 37 arrays, for N = 431 total nucleosomes). The fit to Supplementary Equation S1, including the correction indicated by (C) gives a linker length of 68 ± 14 base pairs, leaving 139 ± 14 base pairs bound to the nucleosome. (G) Histogram of a set of modeled arrays (n = 42 arrays, for N = 504 total nucleosomes). A spread of linker lengths (gold distribution) leads to a dual Gaussian distribution of sequential and non-sequential distances (blue distribution) that matches (F) well and the fit recovers a linker length of 66 ± 9 bp. The model is described in Supplementary Methods 2.

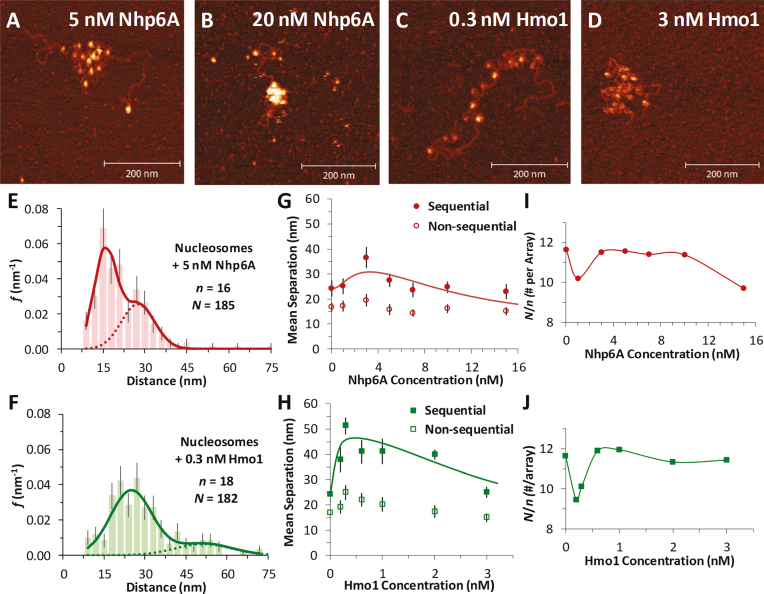

Having established metrics for nucleosome packing in the test arrays, dispersion and compaction of core particles are measured directly as a function of the identity and concentration of HMGB protein added to the nucleosome arrays before deposition on mica. In the presence of either the single box Nhp6A or the double box Hmo1 protein, core particle dispersion is observed as nearest neighbor distances increase. Interestingly, still higher concentrations of HMGB reverse this trend, as nearest neighbor distances decrease and the nucleosome array compacts (see Figure 3A–D for sample images in either protein). Collected histograms of measured nearest nucleosome distances (N nucleosomes over n arrays) across a range of Nhp6A/Hmo1 concentrations are again fit to Supplementary Equation S1. Sample fits appear in Figure 3E and F, while the full set can be found in Supplementary Figure S3 and S4. At the highest tested protein concentrations, the single box Nhp6A condenses core particles so effectively that nearest neighbor distances become equal to the diameter of the core particles themselves (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Nucleosome dispersion and compaction by HMGB proteins. (A, B) Images of reconstituted nucleosome arrays (∼0.1 nM) in solutions containing Nhp6A, with dispersion evident at 5 nM Nhp6A (A) and compaction at 20 nM Nhp6A (B). (C, D) Nucleosomes in solutions containing the 2- box HMGB protein Hmo1, showing nucleosome dispersion at 0.3 nM Hmo1 (C) and compaction at 3 nM Hmo1 (D). (E, F) Histogram of core particle separations in 5 nM Nhp6A (E) and in 0.3 nM Hmo1 (F) showing an increase in the measured distances, fit to the dual Gaussian model of Supplementary Equation S1. Complete sets across all protein concentrations are in Supplementary Figure S3 and S4. (G, H) Summary of measured lengths obtained from fits to the distance histograms, with uncertainties determined as described in Supplementary Methods 1. The longer distance regime is associated with sequential nucleosomes separated by linker DNA (solid symbols). Shorter distances correspond to non-sequential nucleosomes whose approach is not limited by the stiffness of short DNA segments (open symbols). As protein concentration increases, nucleosomes are observed to disperse, then compact at the highest concentrations. This is true for both Nhp6A (G) and Hmo1 (H), though the amount of protein required varies. The sequential data are fit to a dispersion/compaction model (solid line) described in Supplementary Methods 4. (I, J) The measured number of nucleosomes identified in each array (N/n), for a given concentration of Nhp6A (I) and Hmo1 (J). Protein concentrations associated with nucleosome disruption also see some nucleosome loss. Results from fits are found in Supplementary Table S1 and key parameters are shown in Table 1.

Sequential and non-sequential distances (fitted averages of the nearest neighbor distributions), plotted as a function of the added protein concentration in Figure 3G and H, confirm an increase in nucleosome separation at low HMGB concentrations followed by a decrease at high HMGB concentrations. At even higher HMGB concentrations, nucleosomes appear stacked upon each other (Supplementary Figure S5). Here distances between nucleosomes cannot be distinguished and these data are not included in Figure 3. As we discus below, dispersion and compaction are driven by two distinct binding events, and a simple non-interacting model fits well to the data (Supplementary Equation S5 in Supplementary Methods 4). This model uses the known binding affinity of Nhp6A/Hmo1 for DNA ( , which drives compaction) (9,10), and the fits determine the binding affinity of these proteins for the nucleosome (

, which drives compaction) (9,10), and the fits determine the binding affinity of these proteins for the nucleosome ( , which drives dispersion). These numbers are summarized in Table 1 and are discussed below. Finally, the ratio of the total number of nucleosomes to the number of arrays (N/n, Figure 3I and J) shows that some nucleosomes are effectively lost during dispersion (beyond a distance cutoff of 75 nm, or 220 bp, the length of a full 601-sequence).

, which drives dispersion). These numbers are summarized in Table 1 and are discussed below. Finally, the ratio of the total number of nucleosomes to the number of arrays (N/n, Figure 3I and J) shows that some nucleosomes are effectively lost during dispersion (beyond a distance cutoff of 75 nm, or 220 bp, the length of a full 601-sequence).

Table 1.

Results from AFM and OT experiments on nucleosome arrays

| Technique | DNA per Nucleosomea (bp) | Nucleosomes per Arrayb (N/n) |

c (nM)

c (nM) |

d (nM)

d (nM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrays | AFM | 139 ± 14 | 11.6 ± 0.3 | – | – |

| OT | 74 ± 7 | 12.0 ± 0.2 | – | – | |

| Average | 139 ± 14 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | – | – | |

| Arrays +Nhp6A | AFM | 102 ± 6 | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | – |

| OT | 69 ± 9 | 11.0 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | – | |

| Average | 102 ± 6 | 10.6 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 70 ± 10 | |

| Arrays +Hmo1 | AFM | 58 ± 20 | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | – |

| OT | 55 ± 7 | 8.0 ± 0.5 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | – | |

| Average | 56 ± 11 | 8.9 ± 0.6 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 3 ± 1 |

AFM center-to-center length measurements and inner turn (tetrameric) lengths from OT experiments agree very well. For Hmo1 and Nhp6A, the AFM data were taken for concentrations where dispersion was maximized, while the protein concentrations in OT experiments were selected to assure binding saturation. See Methods for more information.

aDNA per nucleosome may be calculated in AFM and OT experiments. In AFM experiments, this is deduced from the linker DNA lengths determined from center-to-center distances as shown in Figure 3G and H. Uncertainties represent the standard deviation as discussed in Supplementary Methods 1. In OT experiments, only the DNA length bound to the tetrasome may be measured, as shown in Figures 4B and 5F (and only the value in Hmo1 contributes toward the average). Uncertainties are standard deviation for at least 10 arrays.

bThe number of nucleosomes per array is found in AFM experiments by identifying nucleosomes as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Nucleosomes are only counted below a center-to-center distance of 75 nm (to exclude surface artifacts). In OT experiments, ripping events below ∼3 pN (Figures 4D and 5A) cannot be reliably counted so tetramers are assumed to be effectively dissociated from the DNA.

cThe HMGB binding affinity for the nucleosome is found from fits to AFM data and OT data. AFM data was fit to Supplementary Equation S5 as found in Supplementary Methods 4 and shown in Figure 3G and H. OT data was fit to Supplementary Equation S6 as found in Supplementary Methods 5 and shown in Figure 5B and C.

OT experiments reveal nucleosome destabilization by HMGB proteins

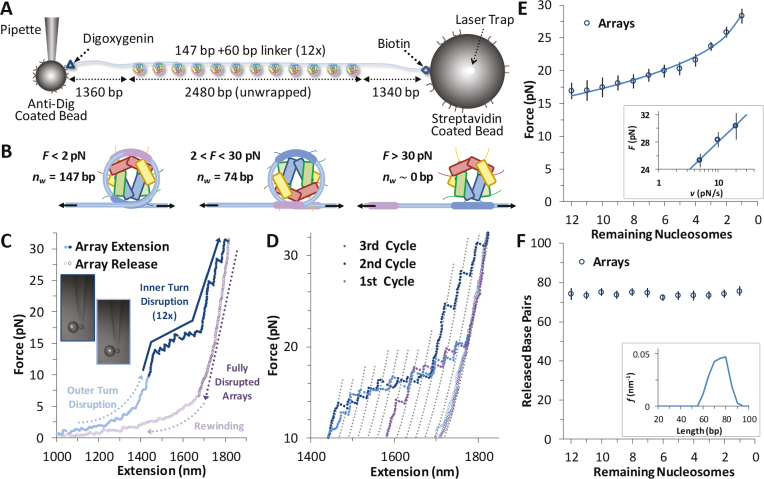

Arrays of nucleosomes are unwound in OT experiments as applied force breaks DNA-histone contacts during cycles of extension and release (Figure 4A) (12,23–26). Previous studies have shown length increases with force that correspond to disruption of the innermost DNA loop, as shown in Figure 4B (26). The outer turn of DNA-histone contacts (more precisely, the two outer halves) are significantly weaker, with contacts distributed along the outer loops with the H2A–H2B dimers. In contrast, DNA-histone contacts with the (H3–H4)2 tetramer fixes the inner turn DNA onto the histone octamer centered on the strong dyad site (Figure 2B). Thus, the observed release of inner turn DNA occurs as single ripping events at rate-dependent forces of >15 pN, while the outer turn DNA is released by gradual unwinding of DNA at forces much lower than 5 pN (26). The H2A–H2B dimers are easily disrupted under these experimental conditions (this is also seen in the AFM results) (27), and dimer release is not consistently observed in these experiments. The exact release force is determined by the sequence-dependent flexibility of the attached DNA, as well as by the pulling rate and the number of nucleosomes on the DNA (12,28).

Figure 4.

Force disruption of nucleosomes. (A) Schematic for arrays in OT experiments. (B) In OT experiments at low forces (<10 pN) the outer turn is gradually unwrapped, as the interactions of the H2A–H2B dimers with the DNA are disrupted (this event is not visible in these experimental conditions). The inner turn is anchored by DNA-histone binding of the (H3–H4)2 tetramer. These DNA–protein interactions are disrupted at ∼20 pN and the entire length of released DNA is measured directly. (C) Data for cycles of increasing extension (solid symbols) and release (open symbols) for reconstituted 12-nucleosome array. Outer turns smoothly unwind below 10 pN (cyan), while 12 discrete inner turn disruption events are clear between 15 and 30 pN (blue). The remaining B-form DNA is slowly released (purple), and below 10 pN, some nucleosomes are observed to partially reform (violet). (D) Sequence of three extension/release cycles (cyan, blue, violet) show nucleosome rebinding does occur, though with decreasing frequency. Dotted grey lines represent disrupted intermediates, each separated by equal contour length changes as guides to the eye and corresponding to the release of the innermost loop (Δx ∼70 base pairs) from an individual nucleosome. (E) Average disruption force as a function of remaining nucleosome number in an array (A) is fit to Equation (1) (solid line). Inset plots release force of the final nucleosome in each array (A = 1) versus the loading rate, fit according to a dynamic force spectroscopy model (26,30). Parameters from both fits are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. (F) Direct measurement of each unwrapping length Δx as a function of the remaining number of nucleosomes in the array (A), corrected for DNA elasticity. Averaged across all nucleosomes, Δx = 74 ± 7 bp (Table 1). Inset shows the distributions of the released DNA for all N.

Data for a full cycle of array extension and release are shown in Figure 4C. Twelve discrete events are typically observed, each roughly equally spaced and corresponding to the successive release of wrapped DNA from each core particle. Most of the unwrapped nucleosomes do not readily dissociate from the DNA, held on it with the strong interaction between the dyad nucleosome site and the DNA. This conclusion follows from the observation that most of the nucleosomes rewind during release. These reformed nucleosomes are disrupted again during a subsequent cycle of extension/release (Figure 4D), indicating that intact histone octamers or possibly just the tetramers stay in the vicinity of the DNA under these experimental conditions (29). As a guide to eye, the polymer model of Supplementary Equation S4 is overlaid to the data using parameters shown in Supplementary Methods 3 and separated by a release length per core particle of ∼70 bp. These lines aid the identification of each release event, where both each release force (F) and the length change to the successive contour length (Δx) are measured individually. The force required increases with each nucleosome unwound in the array (A, see Figure 4E). This force dependence is fit to a kinetic model of the nucleosome unwinding transition state (26):

|

(1) |

Here, dF/dt is the loading rate (∼10 pN/s), while the DNA extension to the transition state (x†) during the inner turn ripping transition and the natural (zero force) rate of unwinding (ko) are fitting parameters. The F(A) dependence is analogous to the ripping force dependence on the force ramp rate, or the DNA pulling rate, as the smaller number of nucleosomes is equivalent to the apparent faster extension per nucleosome, leading to the same net extension rate. These fits are compared to the results from a dynamic force spectroscopy model (26,30) in Supplementary Table S2 and are discussed below. Finally, the length released, once corrected for the force-dependent elasticity (Supplementary Methods S3) does not change with each nucleosome unwound in the array (Figure 4F). The average length of 74 ± 7 bp appears in Table 1.

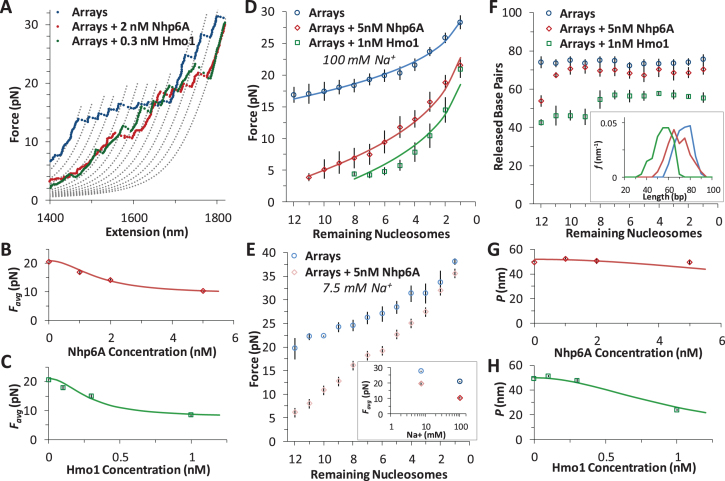

Addition of either HMGB protein (Nhp6A or Hmo1) results in significant lowering of the forces required to disrupt all twelve nucleosomes (Figure 5A). Below ∼3 pN, ripping events cannot be reliably identified and nucleosomes not counted due to this threshold are assumed to be completely dissociated (Table 1). The average ripping force for the full array in the presence of varying HMGB concentrations is fit (Supplementary Methods S5) to give HMGB-nucleosome binding affinities ( ) of 1.6 ± 0.2 nM for Nhp6A and 0.29 ± 0.05 nM for Hmo1 (Figure 5B and C, results are summarized in Supplementary Table S1). Fits of the force for each nucleosome in the array to Equation (1) for saturating concentrations of Nhp6A/Hmo1 reveals that the natural rate of nucleosome unwinding (ko) increases ten-fold in the presence of these proteins (Figure 5D and Supplementary Table S2). Repeating these experiments in the buffer used in the AFM experiments above reveals that nucleosomes are more stable in low salt (7.5 mM Na+ versus 100 mM Na+) while destabilization induced by Nhp6A binding is nearly independent of salt concentration (Figure 5E). Both effects are explained by DNA–histone charge interactions (Supplementary Methods 6). While the DNA-unbinding pathway remains the same in low and high salt, HMGB proteins neutralize most of the charges along the backbone of the DNA at the unbinding site. In addition to destabilization, HMGB binding decreases the DNA length released during OT unwrapping to 69 ± 9 bp for Nhp6A and for Hmo1 it decreases further to 55 ± 7 bp (Figure 5F). These decreasing lengths report the protein-induced DNA-nucleosome unwinding prior to ripping of the DNA-tetramer, discussed below. Finally, the nucleosome-free construct (no octamers) is fit to the worm-like chain of Supplementary Equation S4 over the same range of HMGB concentrations, and compares well to previous estimates of the DNA-HMGB binding affinity (

) of 1.6 ± 0.2 nM for Nhp6A and 0.29 ± 0.05 nM for Hmo1 (Figure 5B and C, results are summarized in Supplementary Table S1). Fits of the force for each nucleosome in the array to Equation (1) for saturating concentrations of Nhp6A/Hmo1 reveals that the natural rate of nucleosome unwinding (ko) increases ten-fold in the presence of these proteins (Figure 5D and Supplementary Table S2). Repeating these experiments in the buffer used in the AFM experiments above reveals that nucleosomes are more stable in low salt (7.5 mM Na+ versus 100 mM Na+) while destabilization induced by Nhp6A binding is nearly independent of salt concentration (Figure 5E). Both effects are explained by DNA–histone charge interactions (Supplementary Methods 6). While the DNA-unbinding pathway remains the same in low and high salt, HMGB proteins neutralize most of the charges along the backbone of the DNA at the unbinding site. In addition to destabilization, HMGB binding decreases the DNA length released during OT unwrapping to 69 ± 9 bp for Nhp6A and for Hmo1 it decreases further to 55 ± 7 bp (Figure 5F). These decreasing lengths report the protein-induced DNA-nucleosome unwinding prior to ripping of the DNA-tetramer, discussed below. Finally, the nucleosome-free construct (no octamers) is fit to the worm-like chain of Supplementary Equation S4 over the same range of HMGB concentrations, and compares well to previous estimates of the DNA-HMGB binding affinity ( , Figure 5G and H) (9,10,31). These results confirm that while HMGB-nucleosome is saturated, HMGB-DNA is not (Supplementary Methods S7).

, Figure 5G and H) (9,10,31). These results confirm that while HMGB-nucleosome is saturated, HMGB-DNA is not (Supplementary Methods S7).

Figure 5.

HMGB proteins disrupt DNA-histone interactions. (A) Force extension of nucleosome arrays in the presence of 1 nM Hmo1 (green) and 5 nM Nhp6A (red), compared to arrays alone (blue). Polymer models are separated by a contour length change of 70 base pairs. (B, C) Average disruption force for each array in the presence of increasing concentrations of Nhp6A (B) and Hmo1 (C). Fits determine HMGB binding affinity to the nucleosome and are discussed in Supplementary Methods 5 while the results are shown in Supplementary Table S1 (key numbers also appear in Table 1). (D) Average disruption force as a function of remaining nucleosome number (A) is fit to Equation (1) (solid line) for arrays (blue circles) and arrays in 5 nM Nhp6A (red diamonds) and in 1 nM Hmo1 (green squares). Adding HMGB proteins reveals a definite decrease in the distance to the transition state (x†) and an increase in the natural (zero force) rate of unwinding (ko). Full results from fits to arrays (blue, χ2 ∼ 2), to arrays in 5 nM Nhp6A (red, χ2 ∼ 5), and arrays in 1 nM Hmo1 (green, χ2 ∼ 5) are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. (E) Average disruption force as a function of remaining nucleosome number (A) for arrays in low salt ([Na+] = 7.5 mM, in cyan) and for arrays in low salt and 5 nM Nhp6A (pink). Inset compares average disruption force with the values at high (100 mM) Na+. Arrays are more stable in low salt and are similarly destabilized by Nhp6A as discussed in Supplementary Methods 6. (F) Direct measurement of each unwrapping length Δx as a function of the remaining number of nucleosomes in the array (A) corrected for DNA elasticity, for nucleosomes (blue circles) and for nucleosomes in the presence of 1 nM Hmo1 (green squares) and 5 nM Nhp6A (red diamonds). Average values of Δx are shown in Table 1 (n > 9 arrays) though disruptions could not always be observed at low forces for each array. Inset shows distributions of the released DNA for all N. (G, H) Measured persistence length (P) of bare DNA in increasing concentrations of Nhp6A (G) and Hmo1 (H). Fits are described in Supplementary Methods 7, and show minimal binding to bare DNA, though nucleosome binding is saturated at these concentrations.

DISCUSSION

Nhp6A partially unwinds the nucleosome outer turn DNA from H2A–H2B dimers while Hmo1 also partially unwinds the nucleosome inner turn from the (H3–H4)2 tetramer

AFM data find sequential core particles separated by an average distance of 24 ± 5 nm in the absence of HMGB protein. This center-to-center spacing represents the average linker length (Figure 2). This length is dependent on whether adjacent particles are flipped relative to the central axis of symmetry of the nucleosome. Since we cannot discern flipping in these images we average to obtain a linker length of 68 ± 14 bp and a wound DNA length of 139 ± 14 bp. The wound length is in good agreement with the known value for this sequence of 147 bp (2,14). The fact that this length is somewhat reduced indicates some dissociation from the H2A–H2B dimer and that this dissociation varies across nucleosomes and even for a single nucleosome over time depending upon solution conditions (22,25,27). These results are confirmed in both the low salt OT experiments of Supplementary Methods 6 and the descriptive model of Supplementary Methods S2 (Figure 6). As the linker length (∼24 nm) is shorter than the persistence length of B-form DNA (∼50 nm), linker DNA should be effectively rod-like on the AFM surface (Supplementary Methods 3).

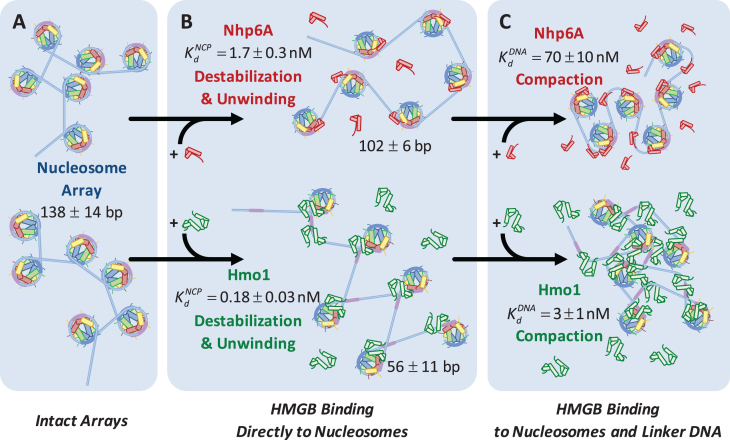

Figure 6.

HMGB induces nucleosome disruption and compaction. (A) For a small 6x ‘array’ in the absence of HMGB proteins (from Figure 1), sequential core particles are shown separated by linker DNA. The variability of linker length due to unwrapping and the possibility of nucleosome flipping leads to an irregularly dispersed 2D array shown. This follows the predictions of the model of Supplementary Methods 2. (B, upper path) Single box Nhp6A binds to the core particle (c ∼  ), disrupting most of the DNA-(H2A–H2B) binding while DNA-(H3–H4)2 interactions remain intact. This leads to nucleosome dispersion, as the core particles appear further apart due to the released lengths of DNA (drawn roughly to scale using the numbers of Table 1). Though HMGB-nucleosome binding may be nearly saturated, there is little binding to double stranded DNA. (C, upper path) At protein concentrations approaching

), disrupting most of the DNA-(H2A–H2B) binding while DNA-(H3–H4)2 interactions remain intact. This leads to nucleosome dispersion, as the core particles appear further apart due to the released lengths of DNA (drawn roughly to scale using the numbers of Table 1). Though HMGB-nucleosome binding may be nearly saturated, there is little binding to double stranded DNA. (C, upper path) At protein concentrations approaching  , protein binding induces DNA bending and random nucleosome compaction. (B, lower path) Double box Hmo1 binds to core particles (c ∼

, protein binding induces DNA bending and random nucleosome compaction. (B, lower path) Double box Hmo1 binds to core particles (c ∼  ), causing complete disruption of DNA-(H2A–H2B) binding and now some disruption of DNA-(H3–H4)2 interactions. This leads to the release of nearly half of the inner turn DNA, further dispersing the core particles of the array. Though it is not shown here, complete dissociation of the octamer is seen for 2–3 of the twelve nucleosomes at the peak of array dispersion. (C, lower path) Higher protein concentrations yield increased binding to linker DNA (c ∼

), causing complete disruption of DNA-(H2A–H2B) binding and now some disruption of DNA-(H3–H4)2 interactions. This leads to the release of nearly half of the inner turn DNA, further dispersing the core particles of the array. Though it is not shown here, complete dissociation of the octamer is seen for 2–3 of the twelve nucleosomes at the peak of array dispersion. (C, lower path) Higher protein concentrations yield increased binding to linker DNA (c ∼  >>

>>  ), inducing nucleosome compaction. Numbers are averages of AFM and OT experiments, where appropriate. See Table 1 for full results and uncertainties.

), inducing nucleosome compaction. Numbers are averages of AFM and OT experiments, where appropriate. See Table 1 for full results and uncertainties.

HMGB binding leads to an increase in separation between both sequential and non-sequential core particles. The increased separation for sequential core particles suggests partial DNA unwinding from the histone octamer, and that octamers neither slide on DNA nor dissociate from it. This is suggested by the constant average distance between the sequential nucleosomes in the AFM images, and the consistent number of 12 nucleosomes per array, as counted in the presence of either HMGB protein and presented in Table 1 (some octamer dissociation is seen in Figures 3I, J and 5D). At the HMGB concentrations corresponding to the maximum nucleosome dispersion, the single box Nhp6A protein increases maximum mean particle separation, indicating that only 102 ± 6 (of 139 ± 14) base pairs remain wound on the histone octamer. The double box Hmo1 protein disperses core particles further, corresponding to conservation of only 58 ± 20 wound base pairs. This implies that Hmo1 binding disrupts DNA-histone binding, such that the DNA remains attached between the strong central dyad site and one of the two strong sites, while the other site is destabilized by the protein binding. Maximum nucleosome dispersion corresponds to HMG concentrations saturating nucleosome binding, but with practically no protein binding to the linker DNA. The lack of associated DNA bending allows for the estimate of both the unwound DNA length and the protein-nucleosome dissociation constant ( ). The latter appears to be 20-fold lower than the protein–DNA dissociation constant (

). The latter appears to be 20-fold lower than the protein–DNA dissociation constant ( , Figure 3). Further increase in HMGB concentration results in protein-linker binding and bending that allows the nucleosomes to closely approach each other and eventually to stack on the AFM surface, leading to nucleosome condensation (summarized in Figure 6 and Table 1).

, Figure 3). Further increase in HMGB concentration results in protein-linker binding and bending that allows the nucleosomes to closely approach each other and eventually to stack on the AFM surface, leading to nucleosome condensation (summarized in Figure 6 and Table 1).

These findings are reinforced by the results of single molecule stretching of the 12-nucleosome array using OT. In the absence of HMGB proteins, each rip releases a DNA length of 74 ± 7 bp (the errors are standard deviations, as opposed to errors in the mean, see Table 1). Previous structures and force spectroscopy experiments have confirmed that the outer DNA turn is stabilized by relatively weaker interactions distributed over the H2A–H2B dimer (2,24,26,29,32,33). The inner turn is held by stronger histone–DNA contacts primarily with the (H3–H4)2 tetramer. In the presence of single box Nhp6A protein at a 5 nM concentration (corresponding to maximum nucleosome dispersion in AFM experiments), the DNA length released during each rip is slightly reduced to 69 ± 9 bp. In contrast, in the presence of 1 nM Hmo1, the AFM length of the nucleosome-wound DNA is only 58 ± 20 bp, closely matching the OT-measured length of inner-turn DNA ripping (55 ± 7 bp; Figure 6C). These results strongly suggest that Nhp6A slightly destabilizes the strong DNA-tetramer sites. We cannot follow the weaker DNA-dimer interactions in our OT experiments, but the increase in the linker length upon Nhp6A binding is consistent with this protein completely unwinding the outer DNA turn wound on the H2A–H2B dimers. Hmo1 further disrupts the DNA interaction with the (H3–H4)2 tetramer, leading to release of part of the 80 base pair inner turn of DNA. Furthermore, HMGB binding disrupts the nucleosome, binding to it with an affinity  that matches the affinity measured for AFM unwinding (Table 1), and relative nucleosome destabilization is not dependent upon solution conditions (Supplemental Methods 6).

that matches the affinity measured for AFM unwinding (Table 1), and relative nucleosome destabilization is not dependent upon solution conditions (Supplemental Methods 6).

Is the inner turn of DNA disrupted symmetrically about the dyad axis or is one side preferentially released by a single HMGB protein? A recent study found a natural asymmetry in stability of the two halves of the 601 nucleosome (12). This asymmetry arises from sequence-dependent differences in DNA flexibility on the two sides of the nucleosomes. The more flexible DNA sequence requires less DNA bending energy to be wrapped around the nucleosome and is therefore more stable. In the model proposed by Travers, HMGB proteins destabilize nucleosomes by binding to the DNA exit or entry point and strongly bending the DNA at that location. Induced bending is toward the nucleosome but with a radius of curvature much smaller that of nucleosomal DNA (34). The resulting bent DNA ‘bubble’ created by the HMG protein is stabilized by the unstructured cationic tail of the HMGB protein, which neutralizes the DNA charge at the binding site. In the case of Nhp6A, this domain is likely its cationic N-terminal tail, while for Hmo1 it is likely its unstructured cationic C-terminal tail. It is not obvious which half of nucleosomal DNA will be preferentially destabilized by HMGB protein binding, as the creation of the bending ‘bubble’ by HMGB might be facilitated on the more stable side of the nucleosome due to the higher local DNA flexibility on that side. It appears highly plausible that both nucleosome stability and destabilization by HMG proteins show asymmetry that leads to one half of the inner turn unbinding prior to the other. Our results indicate half of the inner turn DNA is destabilized by one HMG molecule with only moderate length reduction to 56 bp (from 74 bp without HMG) of the inner turn DNA by the double box Hmo1 protein.

Single HMGB proteins preferentially bind directly to the nucleosome

Both AFM and OT experiments quantified HMGB binding to the nucleosome. We have previously reported DNA binding affinities for Hmo1,  ∼3 nM (10) and for Nhp6A and ∼70 nM (9) under similar solution conditions (Figure 6 and Table 1). Based on these affinities, the amounts of proteins that maximize nucleosome destabilization in the current experiments were well below saturating levels for DNA binding (∼13% and ∼5% for Hmo1 and Nhp6A, respectively). The lower level of DNA saturation observed for the single box Nhp6A at the maximum dispersion observed in AFM experiments is most likely due to much stronger DNA bending by the single box Nhp6A compared to the double box Hmo1. At the same time, the

∼3 nM (10) and for Nhp6A and ∼70 nM (9) under similar solution conditions (Figure 6 and Table 1). Based on these affinities, the amounts of proteins that maximize nucleosome destabilization in the current experiments were well below saturating levels for DNA binding (∼13% and ∼5% for Hmo1 and Nhp6A, respectively). The lower level of DNA saturation observed for the single box Nhp6A at the maximum dispersion observed in AFM experiments is most likely due to much stronger DNA bending by the single box Nhp6A compared to the double box Hmo1. At the same time, the  for Hmo1 binding to DNA reflects higher affinity than Nhp6A, as expected for a protein with an additional binding site (35). Furthermore, these results support the assumption that HMGB proteins prefer to bind bent DNA (36–38), binding to the outside of nucleosome-wrapped DNA more strongly than to bare DNA. Thus, the principal mechanism of nucleosome destabilization involves HMGB protein binding directly to bent nucleosomal DNA, not linear linker DNA. As HMGB binding bends DNA beyond even that seen for nucleosomal DNA, this binding must be happening at the nucleosomal DNA entry or exit points. This is expected to lead to the partial unwinding, but not complete displacement of DNA from the cores, as suggested by Travers et al. (34). Our result agrees with the notion that a single HMGB protein targets DNA bound to one of the H2A–H2B dimers and disrupts the nucleosome by creating a bent DNA ‘bubble’ near this site, as suggested previously (34,39). However, this result is inconsistent with a previous study (40) suggesting that multiple HMGB molecules are required for the nucleosome destabilization and FACT complex loading, and that HMGB proteins bind stronger to the linker than to nucleosomal DNA.

for Hmo1 binding to DNA reflects higher affinity than Nhp6A, as expected for a protein with an additional binding site (35). Furthermore, these results support the assumption that HMGB proteins prefer to bind bent DNA (36–38), binding to the outside of nucleosome-wrapped DNA more strongly than to bare DNA. Thus, the principal mechanism of nucleosome destabilization involves HMGB protein binding directly to bent nucleosomal DNA, not linear linker DNA. As HMGB binding bends DNA beyond even that seen for nucleosomal DNA, this binding must be happening at the nucleosomal DNA entry or exit points. This is expected to lead to the partial unwinding, but not complete displacement of DNA from the cores, as suggested by Travers et al. (34). Our result agrees with the notion that a single HMGB protein targets DNA bound to one of the H2A–H2B dimers and disrupts the nucleosome by creating a bent DNA ‘bubble’ near this site, as suggested previously (34,39). However, this result is inconsistent with a previous study (40) suggesting that multiple HMGB molecules are required for the nucleosome destabilization and FACT complex loading, and that HMGB proteins bind stronger to the linker than to nucleosomal DNA.

If HMGB binding on/off times are fast relative to the time for OT ‘ripping’ of individual nucleosomes, a single HMGB molecule may unbind and re-bind a given nucleosome during a single ripping event. In this fast-binding case, a single HMGB molecule can destabilize both dimer sites. If slow on/off kinetics apply, then each HMGB molecule will be permanently bound to only one side of the nucleosome during the DNA stretching and nucleosome ripping process. In this slow-binding case, the reduction in the apparent length of inner turn DNA most likely arises from disruption of one of the two strong sites, with half of the inner turn DNA length released during each ripping event. In our previous work, we have measured the microscopic rates for Nhp6A and several other single box HMGB proteins dissociating from DNA (9). These off rates were rather fast, on the order of 0.1 to 10 s−1. The slowest rate (0.15 s−1) was measured for Nhp6A. Thus, Nhp6A dwells on naked DNA for ∼7 s. This time is expected to be much longer for the double-box Hmo1 protein. The ripping time for each nucleosome for the nearly constant pulling rate of the array (∼10 pN/s) decreases as 1/A – reciprocally to the number of the nucleosomes left on DNA (as discussed above and described by Equation 1). It thus changes through the complete ripping of all 12 nucleosomes from the total time of stretching (i.e. ∼5 s) to ∼0.4 s (the total array stretching time divided by 12). These time scales are shorter than the typical residency time of Nhp6A on the nucleosome (∼7 s), corresponding to the slow-binding case. At HMGB concentrations studied in our OT stretching experiments, not more than one HMG protein is bound per nucleosome. Therefore, even for Nhp6A, nucleosome stability is altered by a single HMGB molecule binding to a single site in the nucleosome, likely an H2A–H2B dimer. As double box Hmo1 protein kinetics are expected to be even slower than those of Nhp6A, Hmo1 must also destabilize the nucleosome through individual binding events.

As HMGB proteins in vivo are present at the ratio of 1 protein per 10–100 nucleosomes (41), the mechanism of one HMGB protein destabilizing just one site of a nucleosome characterized in this work should be applicable in vivo. However, as the time scales of each NHp6A binding to the nucleosome is only ∼7 s, the overall effect of this HMGB protein on chromatin structure on the biologically important time scales averages over many nucleosomes and their exit/entry points. Higher eukaryotes deploy HMGB domains within the SSRP1 protein as part of the FACT complex (42). These domains presumably affect nucleosome binding and destabilization as FACT recognizes, binds, and reorganizes chromatin (42). As a domain of the much larger SSRP1, the HMGB module binding likely displays kinetics much slower than the smaller Hmo1. Therefore, the in vivo nucleosome-destabilizing activity of HMGB proteins and FACT complexes occur at just one location in each nucleosome.

Histone-DNA contacts throughout the nucleosome are destabilized by HMGB binding

Analysis of nucleosome array force-extension curves shows that the inner turn DNA contacts are weakened by both HMGB proteins (Figure 5D). Our data reveal a drop in the measured forces required for inner turn release in the presence of Nhp6A and Hmo1. Additionally, fits to the unwrapping forces using Equation (1) show a modestly shorter transition state distance in the presence of either HMGB protein, where x† = 0.9 ± 0.1 nm is reduced to x†Nhp6A = 0.6 ± 0.1 nm and x†Hmo1 = 0.6 ± 0.1 nm (Supplementary Table S2). This length change cannot be directly related to the number of unwound base pairs, due to the complicated three-dimensional geometry of nucleosome unwinding in the direction of the force (26,43). Yet this decrease in the distance to the unwrapping transition state due to protein binding demonstrates that a smaller number of base pairs must be disrupted by force from the nucleosome in the presence of HMGB proteins. We also observe that the natural (zero force) inner turn DNA unwinding rate increases 20-fold in the presence of HMGB proteins (Supplementary Table S2). We can estimate the reaction barrier assuming an attempt rate of ka ∼ 109 s−1, according to G† ∼ kBT*ln(ko/ka) (26). Arrays alone show G† = 26 ± 1 kBT, while G†Nhp6A = 24 ± 1 kBT and G†Hmo1 = 23 ± 1 kBT. Therefore, the transition state barrier energy is slightly lowered and the position for inner turn unwinding moves much closer to the wound state. This reconfigures the pattern of core–DNA interactions at the two strong sites holding the inner turn DNA on the core and results in overall nucleosome disruption. Both the single and double box proteins shift the transition state closer to the wound state and reduce the barrier to disruption of the nucleosome outer turn held by the H2A–H2B dimers, while only Hmo1 further disrupts the inner DNA turn held by the (H3–H4)2 tetramer (see Figure 6 for the full summary).

Preferential nucleosome affinity determines HMGB-induced nucleosome dispersion and condensation

From these AFM and OT data we conclude that the inter-nucleosome spacing first increases with HMGB concentration due to protein-induced unwinding of DNA from histone cores, while the unwound regions of DNA remain rigid and rod-like. HMGB-induced nucleosome unwinding without significant linker bending is possible at HMGB concentrations comparable to  (and

(and  is ∼20x lower than

is ∼20x lower than  ). At still higher HMGB concentrations, binding to the linker DNA is also observed, increasing the apparent flexibility of linker DNA, leading to an apparent decrease in the nearest neighbor nucleosome spacing on the AFM surface (Figure 3G and H). As more HMGB protein is added, linker DNA becomes sufficiently flexible to allow close approach between nucleosome cores, leading to their condensation. AFM data in Figure 3 show that sequential core particles are compacted at HMGB protein concentrations >3 nM for Hmo1 and >15 nM for Nhp6A. As the HMGB concentration leading to the maximum nucleosome dispersion is determined by the difference between

). At still higher HMGB concentrations, binding to the linker DNA is also observed, increasing the apparent flexibility of linker DNA, leading to an apparent decrease in the nearest neighbor nucleosome spacing on the AFM surface (Figure 3G and H). As more HMGB protein is added, linker DNA becomes sufficiently flexible to allow close approach between nucleosome cores, leading to their condensation. AFM data in Figure 3 show that sequential core particles are compacted at HMGB protein concentrations >3 nM for Hmo1 and >15 nM for Nhp6A. As the HMGB concentration leading to the maximum nucleosome dispersion is determined by the difference between  and

and  , stronger bare DNA bending by Nhp6A protein causes the crossover between nucleosome unwinding and linker bending to occur at a lower level of linker DNA saturation for Nhp6A compared to Hmo1. At the highest tested HMGB protein concentrations, the remodeled nucleosomes are close enough that both the sequential and non-sequential distances converge to the center-to-center diameter of the core particle (11 nm). Thus, core particles become difficult to distinguish on AFM images at 20 nM Nhp6A (Supplementary Figure S5), and the distinction between sequential and non-sequential core particles is lost in these data. As discussed above, this result is, in turn, consistent with a model in which Nhp6A binds the outer surface of the nucleosome-wound DNA, most likely at the entry or exit points, while the long basic N-terminal tail of Nhp6A binds to the inner surface of DNA, competitively displacing nucleosomal histones (34). This effect is also consistent with the known capability of both HMGB proteins to condense DNA and to facilitate DNA looping (9,10).

, stronger bare DNA bending by Nhp6A protein causes the crossover between nucleosome unwinding and linker bending to occur at a lower level of linker DNA saturation for Nhp6A compared to Hmo1. At the highest tested HMGB protein concentrations, the remodeled nucleosomes are close enough that both the sequential and non-sequential distances converge to the center-to-center diameter of the core particle (11 nm). Thus, core particles become difficult to distinguish on AFM images at 20 nM Nhp6A (Supplementary Figure S5), and the distinction between sequential and non-sequential core particles is lost in these data. As discussed above, this result is, in turn, consistent with a model in which Nhp6A binds the outer surface of the nucleosome-wound DNA, most likely at the entry or exit points, while the long basic N-terminal tail of Nhp6A binds to the inner surface of DNA, competitively displacing nucleosomal histones (34). This effect is also consistent with the known capability of both HMGB proteins to condense DNA and to facilitate DNA looping (9,10).

In this work, HMGB-induced nucleosome destabilization is driven by disruption of DNA-histone contacts throughout the nucleosome through binding interactions alone. An analogous effect of histone tail deletion (in the absence of H1) was studied by Wang et al. with a very similar experimental approach (24). HMGB-induced nucleosome destabilization appears to be much stronger and shows invasion of HMGB protein into (H3–H4)2 binding sites while completely restructuring the pattern of DNA/histone interactions. Thus, Hmo1 more efficiently destabilizes nucleosomes, while Nhp6A enhances apparent DNA flexibility more efficiently. Both HMGB functions may be essential in vivo. Given its high binding affinity for naked DNA, Hmo1 may also maintain DNA in compact form through DNA bridging and looping in the absence of nucleosomes (10). Similarly, at sufficiently high concentrations in the presence of Hho1p, Hmo1 also likely has linker binding functions that are reminiscent of histone H1 in mammals (44). This suggests that the proteins perform distinct cellular functions. Hmo1, which is found in highly transcribed nucleosome-free regions, actively drives creation and/or maintenance of these regions, resulting in replacement of nucleosomes by Hmo1 binding at highly-transcribed ribosomal genes in yeast (45,46). In contrast, Nhp6A is associated with moderately-transcribed genes that likely do not require extensive nucleosome destabilization.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

M.C.W. and L.J.M. formulated the experimental concept. K.L. and U.M. provided octamers and the reconstitution protocol, while N.B. prepared and purified experimental DNA. M.J.M. reconstituted the nucleosomes, performed OT experiments and analyzed data. R.H. performed AFM experiments and analyzed the data with the assistance of N.E.I. HMGB proteins were expressed and purified by N.B. and M.N.-H. while I.R. interpreted results. M.J.M., R.H., M.C.W., I.R. and L.J.M. wrote the manuscript. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.C.W. Sincere thanks to Nabuan Naufer, a graduate student in the lab of M.C.W. who provided guidance with analysis of the AFM data.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health (NIH) [GM072462 to MCW]; NSF [MCB-1817712 to M.C.W.]; NIH [GM75965 to L.J.M.]; Mayo Foundation (to L.J.M.); NIH [GM067777 to K.L.]; Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to K.L.). Funding for open access charge: NIH [GM75965].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Luger K., Dechassa M.L., Tremethick D.J.. New insights into nucleosome and chromatin structure: an ordered state or a disordered affair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012; 13:436–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Luger K., Mader A.W., Richmond R.K., Sargent D.F., Richmond T.J.. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997; 389:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deal R.B., Henikoff J.G., Henikoff S.. Genome-wide kinetics of nucleosome turnover determined by metabolic labeling of histones. Science. 2010; 328:1161–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bianchi M.E. HMGB1 loves company. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2009; 86:573–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gerlitz G., Hock R., Ueda T., Bustin M.. The dynamics of HMG protein-chromatin interactions in living cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009; 87:127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stros M. HMGB proteins: Interactions with DNA and chromatin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Reg. Mech. 2010; 1799:101–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stott K., Tang G.S.F., Lee K.-B., Thomas J.O.. Structure of a complex of tandem HMG boxes and DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006; 360:90–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Allain F.H.T., Yen Y.-M., Masse J.E., Schultze P., Dieckmann T., Johnson R.C., Feigon J.. Solution structure of the HMG protein NHP6A and its interaction with DNA reveals the structural determinants for non-sequence-specific binding. EMBO J. 1999; 18:2563–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCauley M.J., Rueter E.M., Rouzina I., Maher L.J. 3rd, Williams M.C.. Single-molecule kinetics reveal microscopic mechanism by which High-Mobility Group B proteins alter DNA flexibility. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:167–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murugesapillai D., McCauley M.J., Huo R., Nelson Holte M.H., Stepanyants A., Maher L.J. 3rd, Israeloff N.E., Williams M.C.. DNA bridging and looping by HMO1 provides a mechanism for stabilizing nucleosome-free chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:8996–9004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Albert B., Colleran C., Leger-Silvestre I., Berger A.B., Dez C., Normand C., Perez-Fernandez J., McStay B., Gadal O.. Structure-function analysis of Hmo1 unveils an ancestral organization of HMG-Box factors involved in ribosomal DNA transcription from yeast to human. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:10135–10149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ngo T.T.M., Zhang Q., Zhou R., Yodh J.G., Ha T.. Asymmetric unwrapping of nucleosomes under tension directed by DNA local flexibility. Cell. 2015; 160:1135–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leung A., Cheema M., González-Romero R., Eirin-Lopez J.M., Ausió J., Nelson C.J.. Unique yeast histone sequences influence octamer and nucleosome stability. FEBS Lett. 2016; 590:2629–2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lowary P.T., Widom J.. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol. 1998; 276:19–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muthurajan U.M., McBryant S.J., Lu X., Hansen J.C., Luger K.. The linker region of macroH2A promotes self-association of nucleosomal arrays. J. Biol. Chem. 2011; 286:23852–23864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rogge R.A., Kalashnikova A.A., Muthurajan U.M., Porter-Goff M.E., Luger K., Hansen J.C.. Assembly of nucleosomal arrays from recombinant core histones and nucleosome positioning DNA. J. Vis. Exp. 2013; 79:e50354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peters J.P., Becker N.A., Rueter E.M., Bajzer Z., Kahn J.D., Maher L.J. 3rd, Michael L., Johnson J.M.H., Gary K.A.. Quantitative methods for measuring DNA flexibility in vitro and in vivo. Methods Enzymol. 2011; 488:287–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shlyakhtenko L.S., Gall A.A., Lyubchenko Y.L.. Mica functionalization for imaging of DNA and protein–DNA complexes with atomic force microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013; 931:295–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uchida A., Murugesapillai D., Kastner M., Wang Y., Lodeiro M.F., Prabhakar S., Oliver G.V., Arnold J.J., Maher L.J., Williams M.C., Cameron C.E.. Unexpected sequences and structures of mtDNA required for efficient transcription from the first heavy-strand promoter. eLife. 2017; 6:e27283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murugesapillai D., Bouaziz S., Maher L.J. 3rd, Israeloff N.E., Cameron C.E., Williams M.C.. Accurate nanoscale flexibility measurement of DNA and DNA–protein complexes by atomic force microscopy in liquid. Nanoscale. 2017; 9:11327–11337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chaurasiya K.R., Paramanathan T., McCauley M.J., Williams M.C.. Biophysical characterization of DNA binding from single molecule force measurements. Phys. Life Rev. 2010; 7:299–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hazan N.P., Tomov T.E., Tsukanov R., Liber M., Berger Y., Masoud R., Toth K., Langowski J., Nir E.. Nucleosome core particle disassembly and assembly kinetics studied using single-molecule fluorescence. Biophys. J. 2015; 109:1676–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bennink M.L., Leuba S.H., Leno G.H., Zlatanova J., de Grooth B.G., Greve J.. Unfolding individual nucleosomes by stretching single chromatin fibers with optical tweezers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2001; 8:606–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brower-Toland B., Wacker D.A., Fulbright R.M., Lis J.T., Kraus W.L., Wang M.D.. Specific contributions of histone tails and their acetylation to the mechanical stability of nucleosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2005; 346:135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li G., Levitus M., Bustamante C., Widom J.. Rapid spontaneous accessibility of nucleosomal DNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005; 12:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brower-Toland B.D., Smith C.L., Yeh R.C., Lis J.T., Peterson C.L., Wang M.D.. Mechanical disruption of individual nucleosomes reveals a reversible multistage release of DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002; 99:1960–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buning R., van Noort J.. Single-pair FRET experiments on nucleosome conformational dynamics. Biochimie. 2010; 92:1729–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ngo T.T., Yoo J., Dai Q., Zhang Q., He C., Aksimentiev A., Ha T.. Effects of cytosine modifications on DNA flexibility and nucleosome mechanical stability. Nat. Commun. 2016; 7:10813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bohm V., Hieb A.R., Andrews A.J., Gansen A., Rocker A., Toth K., Luger K., Langowski J.. Nucleosome accessibility governed by the dimer/tetramer interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:3093–3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Evans E. Probing the relation between force–lifetime–and chemistry in single molecular bonds. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2001; 30:105–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seol Y., Li J., Nelson P.C., Perkins T.T., Betterton M.D.. Elasticity of short DNA Molecules: theory and experiment for contour lengths of 0.6–7 μm. Biophys. J. 2007; 93:4360–4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sheinin M.Y., Li M., Soltani M., Luger K., Wang M.D.. Torque modulates nucleosome stability and facilitates H2A/H2B dimer loss. Nature Commun. 2013; 4:2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hall M.A., Shundrovsky A., Bai L., Fulbright R.M., Lis J.T., Wang M.D.. High-resolution dynamic mapping of histone–DNA interactions in a nucleosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009; 16:124–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Travers A.A. Priming the nucleosome: a role for HMGB proteins. EMBO Rep. 2003; 4:131–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCauley M.J., Zimmerman J., Maher L.J. 3rd, Williams M.C.. HMGB binding to DNA: single and double box motifs. J. Mol. Biol. 2007; 374:993–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jung Y., Lippard S.J.. Nature of full-length HMGB1 binding to cisplatin-modified DNA. Biochemistry. 2003; 42:2664–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohndorf U.-M., Rould M.A., He Q., Pabo C.O., Lippard S.J.. Basis for recognition of cisplatin-modified DNA by high-mobility-group proteins. Nature. 1999; 399:708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bianchi M., Beltrame M., Paonessa G.. Specific recognition of cruciform DNA by nuclear protein HMG1. Science. 1989; 243:1056–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Panday A., Grove A.. Yeast HMO1: linker histone reinvented. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017; 81:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ruone S., Rhoades A.R., Formosa T.. Multiple Nhp6 molecules are required to recruit Spt16-Pob3 to form yFACT complexes and to reorganize nucleosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003; 278:45288–45295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sebastian N.T., Bystry E.M., Becker N.A., Maher L.J. 3rd. Enhancement of DNA flexibility in vitro and in vivo by HMGB box A proteins carrying box B residues. Biochemistry. 2009; 48:2125–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Winkler D.D., Luger K.. The histone chaperone FACT: structural insights and mechanisms for nucleosome reorganization. J. Biol. Chem. 2011; 286:18369–18374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mack A.H., Schlingman D.J., Ilagan R.P., Regan L., Mochrie S.G.. Kinetics and thermodynamics of phenotype: unwinding and rewinding the nucleosome. J. Mol. Biol. 2012; 423:687–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Panday A., Xiao L., Grove A.. Yeast high mobility group protein HMO1 stabilizes chromatin and is evicted during repair of DNA double strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:5759–5770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Merz K., Hondele M., Goetze H., Gmelch K., Stoeckl U., Griesenbeck J.. Actively transcribed rRNA genes in S. cerevisiae are organized in a specialized chromatin associated with the high-mobility group protein Hmo1 and are largely devoid of histone molecules. Genes Dev. 2008; 22:1190–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hall D.B., Wade J.T., Struhl K.. An HMG protein, Hmo1, associates with promoters of many ribosomal protein genes and throughout the rRNA gene locus in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006; 26:3672–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Luger K., Richmond T.J.. DNA binding within the nucleosome core. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1998; 8:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.