Abstract

E2 enzymes in ubiquitin–like conjugation pathways are important, highly challenging pharmacological targets, and despite significant efforts, few noncovalent modulators have been discovered. Small–molecule microarray (SMM)–based screening was employed to identify an inhibitor of the “undruggable” small ubiquitin–like modifier (SUMO) E2 enzyme Ubc9. The inhibitor, a degradation product from a commercial screening collection, was chemically synthesized and evaluated in biochemical, mechanistic, and structure–activity relationship studies. Binding to Ubc9 was confirmed through the use of ligand–detected nuclear magnetic resonance, and inhibition of sumoylation in a reconstituted enzymatic cascade was found to occur with an IC50 of 75 μM. This work establishes the utility of the SMM approach for identifying inhibitors of E2 enzymes, targets with few known small–molecule modulators.

Keywords: small–molecule microarray, sumoylation, E2 enzymes, Ubc9

Introduction

The posttranslational attachment of the small ubiquitin–like modifier (SUMO) protein plays a critical role in cellular homeostasis. Although ubiquitin conjugation traditionally targets proteins for degradation, modification of a protein substrate with SUMO modulates a variety of factors such as protein stability, localization, or function.1 SUMO conjugation occurs through an enzymatic cascade similar to ubiquitination, involving E1-activating, E2-conjugating, and E3-ligating enzymes. But unlike ubiquitination, which employs more than 30 E2s, the SUMO pathway uses a single E2 enzyme, Ubc9. Abnormal sumoylation is associated with several diseases, including cancers such as ovarian carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, and melanoma, as well as ischemia. Ubc9 is therefore a desirable target for the development of anticancer therapeutics.2

Ubiquitin–like E2s are difficult drug targets due to their overall rigid conformations, lack of “druggable” pockets, and numerous protein-protein interaction sites. Consequently, identifying inhibitors of Ubc9 has been challenging, with few small-molecule ligands reported to date. Existing Ubc9 inhibitors include the natural product spectomycin B1 (IC50 = 4.4 μM)3 as well as a series of small molecules computationally predicted to bind to Ubc9, although limited structural evidence for their binding modes exists.4 Our group previously reported the inhibitor 2-D08 (IC50 = 6.0 μM), which prevents the transfer of SUMO from the Ubc9~SUMO thioester complex to its substrate.5 A more recent fragment–based approach revealed an allosteric small-molecule binding site on Ubc9 that inhibits thioester formation, with fragments having IC50 values in the low millimolar range.6 Inhibitors that target the SUMO E1 enzyme, including ginkgolic acid and tannic acid, have also been reported. To date, these existing inhibitors of sumoylation suffer from weak potency in biochemical or cell–based assays, polyphenolic structures, redox activity, pleiotropic mechanisms of action, or a combination of these issues. The difficulty with identifying selective, reversible inhibitors of sumoylation is highlighted by a study from GlaxoSmithKline that did not find any valid noncovalent inhibitors from a screen of over two million compounds.7 New approaches are thus needed to uncover novel Ubc9-binding ligands and develop chemical probes for the important sumoylation pathway. Small-molecule microarray (SMM) high–throughput screening provides a unique strategy for the discovery of small molecules that bind directly to Ubc9 and inhibit sumoylation.

SMMs allow for profiling small–molecule/protein interactions and have been used to identify compounds that inhibit various “undruggable” targets.8–12 To generate the microarrays, a robotic microarrayer prints glass microscope slides with an arrangement of duplicate spots, with each pair containing a unique small molecule covalently linked to the glass surface. Arrays can be incubated with a fluorescently tagged protein of interest or a fluorescent antibody that recognizes the protein. The slides are then analyzed for fluorescence at each of the printed spots, where an increase in fluorescence reports on protein binding. Although SMM technology has been employed for a variety of macromolecular targets, it has never been applied to the recalcitrant class of E2 enzymes. SMMs, with the ability to screen thousands of structures simultaneously and success in identifying ligands for challenging targets, present a unique, high-throughput platform well suited for the discovery of novel Ubc9-binding compounds. We present herein the first example of applying SMM technology to any E2 enzyme with screening and validation methods that could be broadly applicable to other members of this enzymatic class.

Materials and Methods

General Remarks

Adenosine 5ʹ-triphosphate (ATP) magnesium salt, dithiothreitol (DTT), and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). AlexaFluor 647 C2-Maleimide (AF-647) was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Compounds identified from the small-molecule microarray screen were purchased from ChemBridge (San Diego, CA) or ChemDiv San Diego, CA). The following recombinant proteins were purchased and used without further purification in biochemical assays: SUMO E1 (E-315; Boston Biochem, Cambridge, MA), Ubc9 (BML-UW9320; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), RanGAPl fragment (GST-tag, BML-UW9755; Enzo Life Sciences), SUMO-1 (His-tag, UL-715; Boston Biochem), SUMO-1 Fluorescein (UL-735; Boston Biochem), UBE1 (UB101; Life Sensors, Malvern, PA), UBE2B (His-tag, E2–613, Boston Biochem), UbcH5b (BML-UW0565; Enzo Life Sciences), and Ubiquitin N-terminal Fluorescein (U-580; Boston Biochem). See supplementary material for additional experimental procedures.

Protein Labeling

Ubc9 was buffer exchanged into 100 mM Tris (pH 8) via centrifugal filtration (3000 Da MWCO; EMD Millipore, Billerca, MA) and concentrated to ~1.5 mg/mL. To 50 μL of the protein solution was added TCEP (0.5 μL of 100 mM) and AF-647 (1.5 μL of 10-mM DMSO stock) followed by incubation in the dark at 4 °C overnight. Unreacted dye was quenched by the addition of DTT (5 μL of 100 mM), and the labeled protein was purified by gel filtration through a Sephadex PD-10 (GE Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA) column preequilibrated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and then concentrated by centrifugal filtration. Labeling and purity were assessed using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as well as absorbance measurements collected on a NanoDrop 2.0 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE ).

SMMs

SMMs were printed, and screening and analysis were performed as previously described.8,10,11 Briefly, microarray slides were incubated with 5 mL blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin [BSA] in PBS with Tween 20 [PBST]) in Nunc 4-well plates (ThermoFisher Scientific) wrapped in aluminum foil with gentle shaking for 30 min. Slides were washed three times with 0.1% BSA in PBST and then incubated with labeled Ubc9 (500 nM in 0.1% BSA/PBST) for 2 h at room temperature using the parafilm technique. In this technique, a 4 × 4–in. square of parafilm was taped to a smooth, flat surface. Labeled protein (500 ×L) was pooled on the parafilm, and the slide was slowly inverted into the buffer, printed side down, beginning with the end opposite the barcode and allowing the protein solution to spread over the slide as it was lowered. Aluminum foil or a small cardboard box was placed over the slide to protect it from light during the incubation. After 2 h, the slide was gently lifted, taking care not to scratch the surface, and washed in a Nunc plate three times with PBST and once briefly with deionized water followed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 2 min to dry. Fluorescence of the small–molecule screening slide was immediately measured using a GenePix (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) 4000a Microarray Scanner and analyzed for hits by comparison to a slide incubated with buffer alone.

Sumoylation Assays

The in vitro sumoylation assay was performed in 20 μL reaction buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 9], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) containing SUMO E1 (0.1 μM), Ubc9 (0.15 μM), SUMO-1 (His-tag, 1.4 μM), and a fluorescent peptide (FL-AR) substrate5 (1 μM) incubated with various concentrations of small molecule in DMSO or DMSO alone (4% final concentration). Experiments with mutant Ubc9, obtained as previously described,6 were conducted according to the same procedure using K59A or E42A Ubc9 in place of the wild-type E2. The reaction was then initiated by the addition of ATP (2 mM final concentration) and incubated at room temperature for 90 min. Following incubation, samples were quenched by the addition of NuPAGE 4X LDS sample buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific), heated at 95 °C for 5 min, loaded onto NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis–Tris Protein Gels (ThermoFisher Scientific), resolved by electrophoresis, and visualized by an in-gel fluorescence method using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Life Sciences) imaging system at an appropriate wavelength (488 nm excitation with blue Epi-RGB light, Y515 Di emission filter, and F0.85 iris).

Alternatively, the sumoylation assay was performed using a recombinant RanGAP1 fragment as the substrate with SUMO E1 (0.05 μM), Ubc9 (0.08 μM), SUMO-1 Fluorescein (0.1 μM), and the RanGAP1 fragment (0.25 μM) incubated with small molecules or DMSO in a 20-μL reaction buffer. Following ATP addition and incubation at room temperature for 1 min, reactions were quenched by the addition of LDS sample buffer and analyzed as described above.

Thioester Bond Formation Assay

The E1~SUMO-1 thioester bond formation assay was performed in a 20-μL reaction buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8], 5 mM MgCl2) containing SUMO E1 (0.35 μM) and SUMO-1 Fluorescein (0.5 μM) incubated with various concentrations of small molecule in DMSO or DMSO alone (4% final concentration). The reaction was initiated by the addition of ATP (2 mM final concentration). Following incubation at 37 °C for 20 min, samples were quenched by the addition of NuPAGE 4X LDS sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by in-gel fluorescence imaging.

Sumoylation Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

The in vitro sumoylation assay was executed as previously described.5,6 The assay was performed in a 384-well plate format in 20 μL Tris buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 9], 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT) with SUMO E1 (0.1 μM), SUMO-1 (His-tag, 1.4 μM), Ubc9 (0.15 μM), fluorescent peptide FL-AR (1 μM), and small molecule (4% DMSO final). For experiments with detergent, either Triton X-100 or Tween 20 (0.01%, v/v) was incorporated into the assay buffer as well. The reactions were initiated by the addition of ATP (2 mM final concentration). After 90 min, EDTA (0.25 M, 8 μL) was added to each well to quench the reactions. Samples were analyzed using a LabChip EZ Reader II (Caliper Life Sciences, Waltham, MA) with the following run conditions: downstream voltage of −500 V, upstream voltage of −2500 V, and pressure of −1.0 psi. The sumoylation reactions were analyzed by quantifying percent conversion, defined as 100 × P/(P + S), where P is peak height of sumoylated product SUMO-1-FL-AR and S is peak height of peptide substrate FL-AR. Data were normalized to positive and negative controls (ginkgolic acid and DMSO, respectively).

Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Ubc9 was buffer exchanged into 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6) by centrifugal filtration (3000 Da MWCO; EMD Millipore) and concentrated. Samples of 2 (125 μM) with or without Ubc9 (6.25 μM) were prepared in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6) containing N-methyl-L-valine (125 μM), TSP-d4 (125 μM), 10% D2O, and 4% DMSO-d6. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were acquired at 298 K on a Bruker (Billerica, MA) AVANCE III 500-MHz spectrometer fitted with a TCI Cryoprobe with Z-gradient. Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) data sets with Presaturation Water Suppression (cpmgpr1d) were acquired using a 200-ms T2 relaxation filter (d20 = 0.001 s, L4 = 200) with an 8-s relaxation delay. O1 was set to 2355.14 Hz and RG to 18, and data sets were acquired with 256 scans. Data were processed with the MestReNova (Santiago de Compostela, Spain) software package. The spectra of the sample with and without protein were arrayed and scaled so that the peak heights of the internal standard N-methyl-L-valine were aligned. Significantly attenuated ligand peaks (≥20%) in the presence of protein were indicative of small-molecule binding.

Results and Discussion

SMMs were used to screen a collection of 19,200 commercially available compounds for binding to fluorescently tagged Ubc9 (Fig. 1). This library of compounds, described previously, was assembled to represent a chemically diverse collection that broadly fits within modern definitions of “druglike” chemical space.10,11 SMMs were prepared using isocyanate surface chemistry to immobilize the small molecules to the glass surface via an amine or alcohol handle.8 Ubc9 was labeled with a thiol-reactive, maleimide-containing AlexaFluor 647 dye to achieve a 1:1 dye/protein stoichiometry. Ubc9 contains two free cysteine residues, the catalytic cysteine (C93) and a remote cysteine (C138), of comparable reactivity. We anticipated that the entire surface of the protein would be available for potential ligand binding by screening Ubc9 with a distribution of labeled cysteines, enabling the discovery of molecules that bind to allosteric sites or the active site. We prepared a similarly labeled UbcH5b, a ubiquitin E2 enzyme that contains only one reactive cysteine in the active site, to screen in parallel. SMM slides were then incubated with each fluorescently labeled protein. Protein-incubated slides were compared to buffer-incubated slides, and composite z scores were generated for each printed compound on the array. This approach yielded 133 hits for Ubc9 with a z score greater than 4, for an overall hit rate of 0.69%. Among these, 34 of the most promising hits were selected based on high z scores, lack of binding to UbcH5b, and visual inspection of array data and chemical structures then purchased for evaluation of biochemical activity (Suppl. Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Small-molecule microarray screening approach for identifying compounds that bind to fluorescently tagged Ubc9. Structural points of attachment to the glass slide are indicated in red.

The ability of each compound to inhibit sumoylation in a reconstituted enzymatic cascade was measured at a single concentration through monitoring the conjugation of SUMO-1 to a fluorescently labeled peptide substrate by microfluidic electrophoretic mobility shift using an assay previously developed in our laboratory (Fig. 2A and Suppl. Fig. S2).5 Compounds that caused at least a 25% decrease in sumoylation activity compared to controls at this single concentration were investigated in dose-response format to obtain full inhibitory curves (Suppl. Fig. S3). Several possible leads exhibited either poor curves or poor solubility and were not pursued further. However, one compound with the reported structure 1 generated a complete sigmoidal inhibition curve and was therefore selected for additional study.

Figure 2.

(A) Inhibition of sumoylation at 50 μM by selected hits from the microarray screen (obtained from commercial sources). GA, ginkgolic acid, 30 μM. See Supplemental Figure S2 for full graph. (B) Oxidation of compound 1 to 2. (C) Synthesis of inhibitors 1 and 2.

The purity of the commercial sample of 1 was determined by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/ MS) analysis. MS analysis revealed that the sample contained a significant quantity of an unknown molecule with m/z of 350 mass units, 4 Daltons less than expected for 1, with very little of this expected compound observed. Given the susceptibility of tetrahydropyridines toward aromatization, we hypothesized that amine 1 could have spontaneously oxidized to the corresponding pyridine 2 upon storage, resulting in a molecule with the observed mass (Fig. 2B). We set out to confirm this hypothesis via chemical synthesis of both structures.

The syntheses of 1 and 2 began with known aryl chloride 3 (Fig. 2C). The amine-bearing sidechain was introduced by SNAr substitution, followed by acid-mediated deprotection to generate 1. After an assessment of several oxidation conditions, IBX was found suitable to furnish 2 in reasonable yield. Alternatively, 2 could be produced from the known aryl chloride 4 directly by SNAr substitution. The identity of 2 as the major component of the commercial sample was confirmed by LC/MS coinjection (Suppl. Fig. S4). It is significant to note that solid 1 was also observed to oxidize partially to 2 upon standing at room temperature over the course of 10 weeks (Suppl. Fig. S5), confirming that spontaneous oxidation of the tetrahydropyridine core is feasible. Compound 2 was then generated in its hydrochloride salt form for increased solubility under the assay conditions in further studies.

Evaluation of synthetic samples of both 1 and 2 in the microfluidic biochemical assay demonstrated that both compounds were able to inhibit sumoylation. However, the oxidized product 2 was ~40 times more potent with a halfmaximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 74 ± 5 μM compared to 3.0 ± 0.6 mM for 1. In addition to blocking sumoylation of the fluorescent peptide substrate, 2 inhibited SUMO-1 conjugation to a recombinant fragment of the protein RanGAPl at micromolar concentrations (Fig. 3A,B). These results validated 2 as the active component of the sample identified from the microarray screen.

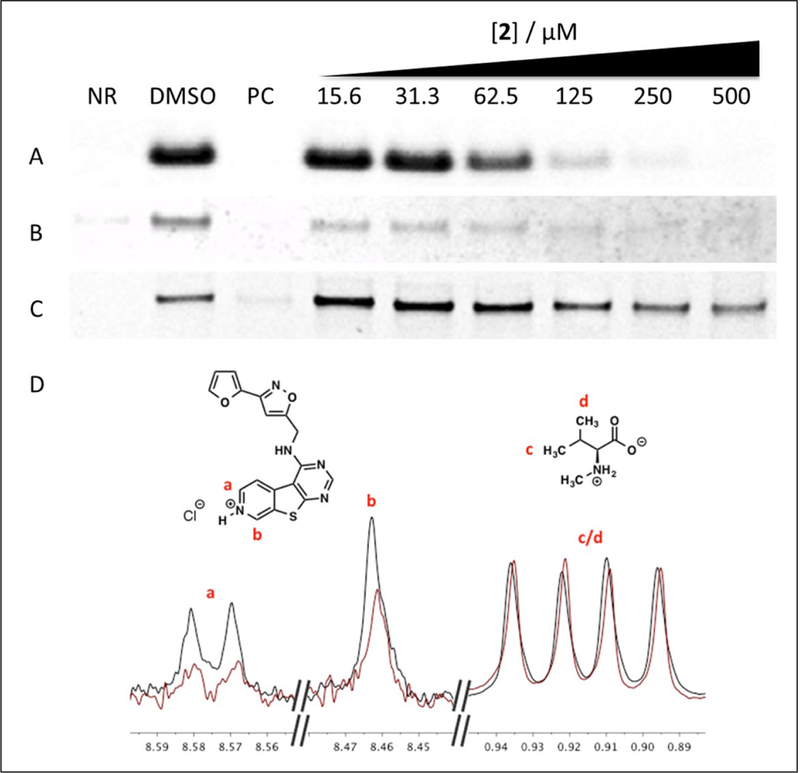

Figure 3.

Inhibition of small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO-1) conjugation to (A) a fluorescent peptide substrate or (B) RanGAPI by 2. (C) EI~SUMO thioester formation is unaffected by 2. No reaction (NR) = -ATP (A and B) or -EI (C); positive control (PC) = 30 M ginkgolic acid. (D) Overlaid Carr-Purcell-Meiboom- Gill spectra of 2 in the absence (black) and presence (red) of Ubc9, normalized to N-methyl-L- valine. See Supplemental Figure S10 for full spectra.

The structure-activity relationship (SAR) of the molecule was then studied. A series of truncated analogues were investigated in the microfluidic sumoylation assay (Table 1). Chloropyrimidine 4 showed no inhibitory activity up to the limits of solubility. However, the isoxazole furan 5 weakly inhibited sumoylation with an IC50 of 4.9 ± 1.5 mM. A structurally similar compound containing an isoxazole furan sidechain was identified as a Ubc9-binding hit from the SMM screen, although it did not show substantial activity in the subsequent biochemical assay (Suppl. Figs. S1 and S2). These results spawned investigations into altering the fused ring substructure. We synthesized analogues with abbreviated structures and found that 6, lacking the pyridine ring, retained activity but was less potent than the parent compound, with an IC50 of 377 ± 48 μM. Compound 7, further truncated to a simple pyrimidine, showed no activity below 5 mM. Several analogues of tetrahydropyridine 1, varying the nature of the isoxazole furan substituent, were also purchased and assayed for SUMO inhibition (Suppl. Fig. S6). At 50 μM, none of the analogues showed inhibitory activity, further confirming that the tetrahydropyridine core is not relevant for inhibition. Next, these analogues were each oxidized to their pyridine counterparts. Upon oxidation, the analogues remained inactive toward inhibiting sumoylation up to 500 μM. This SAR indicates that the isoxazole furan sidechain is necessary for inhibition, while the extended aromatic core improves potency.

Table 1.

Inhibition of Sumoylation by the Small-Molecule Microarray Hit 1 and Derivatives.

| Compound | Structure | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

3000 ± 650 |

| 2 |  |

74 ± 5 |

| 4 |  |

>500a |

| 5 |  |

4900 ± 1500 |

| 6 |  |

377 ± 48 |

| 7 |  |

5800 ± 300 |

IC50 values represent the averages of at least three trials, each conducted in triplicate, with standard deviations.

Solubility limited.

A major concern with small molecules identified in high- throughput screening is the prevalence of false positives that nonspecifically inhibit enzymes due to aggregation in aqueous solution. One method of detecting artifactual inhibition is to incorporate nonionic detergent into the assay buffer. Compound 2 maintained its inhibitory activity in the presence of each of two detergents, with only modest changes in IC50 values (Suppl. Fig. S7). In a separate experiment, centrifugation of the diluted sample before addition to the assay medium did not affect the compound’s activity, further suggesting that it remains in solution. Furthermore, in the Aggregator Advisor,13 compound 2 had a clogP of 2.7, below the threshold of 3.0 considered to be an aggregation risk, and was not similar to any other known aggregators in the database. Finally, dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments on 2 indicated particle sizes mostly below 0.1 nm, consistent with a soluble, well-dispersed compound (Suppl. Fig. S8). Taken together, these data indicate that it is unlikely that 2 forms aggregates under these assay conditions.

We performed ligand–observed CPMG (LO-CPMG) T2 relaxation NMR experiments to confirm that 2 binds directly to Ubc9.14,15 Spectra were normalized to an internal negative control (N-methyl-L-valine), which does not bind to Ubc9. In this experiment, substantial (>20%) decreases in peak intensities for protons of 2 were observed in the presence of Ubc9, indicating direct binding to the protein (Fig. 3D).

To further study the biochemical behavior of 2, we conducted a series of mechanistic experiments. E1~SUMO thioester formation was unaffected by 2 at any concentration, confirming that the small molecule does not act at this step of the enzymatic cascade (Fig. 3C). In addition to wildtype enzyme, two Ubc9 mutants (K59A and E42A) that disrupt a recently identified allosteric site were evaluated.6 Compound 2 was able to inhibit SUMO conjugation to the fluorescent peptide substrate for all three enzymes without any apparent change in potency (Suppl. Fig. S9). Since inhibitory activity is maintained when the allosteric binding site is disrupted, we conclude that 2 does not interact with Ubc9 at this allosteric pocket. The specificity of 2 for inhibiting the SUMO E2 over other ubiquitin E2s was also investigated. Compound 2 inhibited the autoubiquitination of both UBE2B and UbcH5b with potencies of 120 μM and 118 μM, respectively, as measured by gel densitometry (Suppl. Fig. S9). Thus, this scaffold has some selectivity for Ubc9 over other E2 enzymes.

In summary, we have reported the first example of an SMM screening approach used to identify small molecules that bind to the SUMO E2 enzyme Ubc9. The applicability of this approach is evidenced through the discovery of 2, which was identified as a degradation product from a commercial screening collection, confirmed to bind to Ubc9 by NMR, and validated as an active sumoylation inhibitor in biochemical assays. Activity against the E1 enzyme was ruled out, as was artifactual inhibition by aggregation. In addition, this compound displayed a clear SAR that revealed the importance of the isoxazole furan sidechain as well as the oxidized, extended heterocyclic core for increased potency. Currently, the potency of 2 is comparable with the few other known inhibitors of Ubc9 and could likely be improved through additional medicinal chemistry efforts. Compound 2 does not bind to a previously identified allosteric site on Ubc9, and it inhibits Ubc9 as well as two other ubiquitin E2 enzymes, UBE2B and UbcH5b, albeit with lower potency. Binding of UbcH5b to 2 was not observed in the parallel SMM screen, but the active site of this enzyme was labeled with a fluorescent dye. Given the inhibitory activity in a reconstituted biochemical assay, the lack of binding when the active site is blocked, and the high homology of E2 active sites and 3D structures, we conclude that 2 likely binds at or near the active site of these enzymes. The SMM screening approach, which successfully unveiled a small-molecule modulator of Ubc9 where many other strategies have failed, hence provides a viable method to screen for inhibitors of the understudied, challenging class of E2 enzymes with significant pharmacological importance. Future efforts will focus on developing more potent analogues of 2 suitable as molecular probes or for cellular studies as well as application of SMM screens to other E2 enzymes in ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like conjugation pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Tarasov and M. Dyba (Biophysics Resource, SBL, NCI at Frederick) for assistance with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and DLS measurements as well as Dr. M. Hoffmann (Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The College at Brockport, SUNY) for providing the 1D CPMG with soft excitation sculpting pulse sequence.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN26120080001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This Research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Geiss-Friedlander R; Melchior F Concepts in Sumoylation: A Decade On. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mo YY; Yu YN; Theodosiou E; et al. A Role for Ubc9 in Tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2005, 24, 2677–2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirohama M; Kumar A; Fukuda I; et al. Spectomycin B1 as a Novel SUMOylation Inhibitor That Directly Binds to SUMO E2. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2635–2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar A; Ito A; Hirohama M; et al. Identification of Sumoylation Activating Enzyme 1 Inhibitors by Structure-Based Virtual Screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2013, 53, 809–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YS; Nagy K; Keyser S; Schneekloth JS An Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay Identifies a Mechanistically Unique Inhibitor of Protein Sumoylation. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 604–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitt WM; Lountos GT; Zlotkowski K; et al. Insights Into the Allosteric Inhibition of the SUMO E2 Enzyme Ubc9. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 5703–5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandt M; Szewczuk LM; Zhang H; et al. Development of a High-Throughput Screen to Detect Inhibitors of TRPS1 Sumoylation. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2013, 11, 308–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradner JE; McPherson OM; Koehler AN A Method for the Covalent Capture and Screening of Diverse Small Molecules in a Microarray Format. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2344–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duffner JL; Clemons PA; Koehler AN A Pipeline for Ligand Discovery Using Small-Molecule Microarrays. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007, 11, 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felsenstein KM; Saunders LB; Simmons JK; et al. Small Molecule Microarrays Enable the Identification of a Selective, Quadruplex–Binding Inhibitor of MYC Expression. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sztuba–Solinska J; Shenoy SR; Gareiss P; et al. Identification of Biologically Active, HIV TAR RNA–Binding Small Molecules Using Small Molecule Microarrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8402–8410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanton BZ; Peng LF; Maloof N; et al. A Small Molecule That Binds Hedgehog and Blocks Its Signaling in Human Cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 154–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irwin JJ; Duan D; Torosyan H; et al. An Aggregation Advisor for Ligand Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 7076–7087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann MM; Sobstyl HS; Badali VA T2 Relaxation Measurement with Solvent Suppression and Implications to Solvent Suppression in General. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2009, 47, 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Headey SJ; Pearce MC; Scanlon MJ; Bottomley SP Blind Man’s Bluff—Elaboration of Fragment Hits in the Absence of Structure for the Development of Antitrypsin Deficiency Inhibitors. Aust. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.