Abstract

A considerable number of patients with a cancer diagnosis are of childbearing age and have not satisfied their desire for a family. Despite ovarian cancer (OC) usually occurring in older patients, 3%–14% are diagnosed at a fertile age with the overall 5-year survival rate being 91.2% in women ≤44 years of age when it is found at 1A–B stage. In this scenario, testing the safety and the efficacy of fertility sparing strategies in OC patients is very important overall in terms of quality of life.

Unfortunately, the lack of randomised trials to validate conservative approaches does not guarantee the safety of fertility preservation strategies. However, evidence-based data from descriptive series suggest that in selected cases, the preservation of the uterus and at least one part of the ovary does not lead to a high risk of relapse. This conservative surgery helps to maintain organ function, giving patients of childbearing age the possibility to preserve their fertility.

We hereby analysed the main evidence from the international literature on this topic in order to highlight the selected criteria for conservative management of OC patients, including healthy BRCA mutations carriers.

Keywords: ovarian cancer survivors, fertility preservation, ovarian cancer, fertility in cancer patients

Introduction

Gynaecological cancers are relatively frequent in the female population, with a global estimated incidence of 222,700 new cases in Europe [1]. Thus, a considerable number of patients affected by gynaecological tumours are of childbearing age at diagnosis and have not completed their desire for a family. Among all ovarian cancers (OCs), 12% are diagnosed in fertile women. The overall 5-year survival rate for all OCs in women ≤44 years of age is 91.2% when it is found at stages 1A and 1B [2]. Owing to increased survival, there is a new focus on the quality of life (QoL) for cancer patients. As evidenced by a Wenzel study in which women survived lymphoma, gestational trophoblastic tumour and cervical cancer, and who were unable to procreate after cancer treatment, but who still desired fertility, experienced significant regret, so proving that the desire for reproduction is an important factor contributing to improved QoL [3]. However, compared to other tumours, the gonadotoxicity derived from medical and/or radiation treatment did not represent the main cause of infertility. In particular, for women with OC, it can be especially difficult to maintain reproductive function because the ovary is the site of primary cancer. Thus, ovaries containing ovarian follicles become a target to be treated to remove cancer cells although they should be protected for fertility.

Psychological impact

As already demonstrated, cancer is a disease that not only causes damage and physical limitations but also causes psychological changes with negative impacts. Patients with cancer have a high rate of comorbid psychiatric disorders, as well as nonspecific psychological distress [4, 5]. Most patients with epithelial OC (EOC) experience some level of ongoing psychological distress throughout the course of their disease with particular evidence of depression and anxiety [6–8]. In a study conducted in 2006, Mc Corkle et al demonstrated that women with gynaecological cancer have a greater tendency towards depression, thanks to many changes in their marriages, work or financial statuses [9]. Besides, a radical reduction in QoL helps to increase an anxious and depressed state [10]. In fact, women suffering from OC experience as their first discomfort changes in their body due to radical surgery or the administration of cytotoxic therapies. Poor body image has been significantly associated with fatigue and poor sexual functioning, particularly among women who were premenopausal at diagnosis. Sexual problems may be secondary to the effects of surgery, chemotherapy or menopause, or may be due to a partner’s sexual issues or relationship problems. Women may complain of dyspareunia, loss of desire or other sexual dysfunction [11]. It’s important to identify patients with particular risk of developing sexual and psychological problems using the available questionnaire about sexual function before cancer, current sexual activity and how cancer is modifying sexual health and relationship with the partner: Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women or the Female Sexual Function Index [12, 13].

Fertility-sparing methods

There are several techniques for the preservation of fertility in case of the necessity of radical surgery:

Embryo cryopreservation

Since 1983 with the first case, embryo cryopreservation is a proven method of fertility preservation. In women with OC, this procedure can be performed only if there is no therapeutic urgency as at least 2–3 weeks is usually necessary to carry out the procedures. it is not recommended to stimulate the ovaries, after the beginning of chemotherapy, because of the proven poor ovarian response. Actually, the ovulation induction protocols from the third day of the cycle, or the one with the administration of subcutaneously injected gonadotropins for 8–14 days are effective. For this procedure, a male partner or a male gamete donor is required [14].

Oocyte cryopreservation

Oocyte cryopreservation could be a valid option for patients with unilateral OC. Oocytes could be acquired during unilateral ovariectomy. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) is not indicated in case of early intervention nor in prepubescent patients, and it is also not indicated in patients with granulosa cancer due to rapid hormone-dependent proliferation. The oocytes can be acquired immature or mature.

Immature oocytes are acquired without the need of stimulation and subsequently are matured in vitro either before freezing or after thawing [15]. In addition, immature oocytes are more resistant to cryoinjury than mature oocytes since they do not contain a metaphase spindle. Rienzi et al showed that to achieve successful live birth through cryopreserving oocytes, at least eight oocytes are required for patients aged <38 and more than eight oocytes in patients aged >38 [16]. Compared to embryo cryopreservation, oocyte freezing is still associated with lower pregnancy rates (4.6%–12% versus 30%–40%). In this case, no partner is needed [17].

Ovarian cryopreservation

Ovarian cryopreservation followed by heterotopic implantation or orthotopic implantation is a technique that can be offered to patients who require early treatment and those who have hormone-sensitive tumours, in fact, no ovarian stimulation is required. It is also the only solution to offer to prepubertal patients. Ovarian tissue preservation is not an option for women with OC or at high risk of developing OC (BRCA1-2 carriers patients). However, it has been hypothesised that if the ovarian tissue is frozen when the woman is very young and at very low risk of OC, cryopreservation of ovarian tissue may still be considered [18].

However, it must be considered that surgery is not the only procedure that damages fertility in women with OC. There is also a harmful effect of chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

The most effective chemotherapeutic regimen for epithelial OC is a combination of a platinum compound and a taxane. Alkylating agents are gonadotoxic chemotherapeutic agents and have most consistently been associated with ovarian failure in a dose-dependent manner. The American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Committee stated that women treated with high doses (≥ 5 g/m2) of alkylating agents have a high risk (more than 70%) to develop permanent amenorrhoea [19]. Alkylating agents determine oocytes damage via single-stranded DNA breaks and targets cells at every stage of cell cycle, preferentially on primordial follicles [20]. The impact on fertility of taxanes and platinums is an intermediate risk level (30%–70%) of amenorrhoea, whereas protocols containing antimetabolites and anthracyclines are related to a lower risk (less than 30%) [20]. Radiation is reserved for chemotherapy-resistant OCs. Lower doses of radiation therapy are used for OCs, resulting in germ cell death in the contralateral ovary in the case of unilateral oophorectomy. Germ cells are the most sensitive cells in the body to radiation and chemotherapy [21]. The reason for this high sensitivity is assumed to be related to the presence of a TAp63 molecule, a main molecule of the apoptotic pathway. TAp63, as a guardian of germ cells, decides the fate of cells depending on the intensity of DNA damage [22]. It is thought that this is a unique phenomenon in female germ cells that protect the genetic material transmission from generation to generation. c-Abl, an upstream molecule, has been shown to regulate TAp63 [23]. Through understanding the precise pathway of germ cell death and targeting the pathway, germ cells can be protected from the off-target effects of radiation and chemotherapy. Developing fertiprotective agents has long been studied to protect oocytes against radiation and chemotherapy. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists and agonists are used for this function. The role of temporary ovarian suppression with GnRHa during chemotherapy has been accurately studied for the past years with contrasting results [24–27]. However, recent data show the impact of this strategy in breast cancer patients [28, 29] with a significant reduction in the risk of treatment-induced premature ovarian failure and higher pregnancy rates in patients receiving GnRHa during chemotherapy [30–32].

It is clear that the choice to perform fertility sparing surgery must take into account the type of tumour and the stage.

For this reason, we reported the current available data about fertility preservation strategies in ovarian tumours, according to histotype as follows:

Borderline tumours

Borderline ovarian tumours (BOTs) comprise 10%–20% of ovarian epithelial tumours and are typically diagnosed during reproductive years. Survival rates are about 99%, with a 70-month disease-free survival in cases of stage I tumours, and the survival rate in cases of stage III tumours is about 89% [33, 34]. While some authors recommend bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as the initial treatment for early-stage BOT, others have also reported excellent results with more conservative treatments, including cystectomy or unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy [35]. Fertility sparing surgery was associated with a higher risk of relapse but not with increased mortality [20]. Factors associated with a higher risk of relapse after conservative surgery for early-stage BOT include age <30, bilaterality and type of surgery (cystectomy versus adnexectomy). Micropapillary histologic pattern, stage and presence of invasive implants are other well-recognised risk factors [36, 37]. Women desirous of offspring should be made to have regular intercourse after 3 months from surgery, in those women who have no partner or because they want to postpone pregnancy oocyte cryopreservation after ovarian stimulation is advised. The data in the literature suggest that it is unclear whether assisted reproductive techniques are associated with an increased risk of recurrence, but it is underlined that most recurrences (11/12) were BOT and were successfully managed by surgery [38].

Some other methods could be used in the future. Currently, we are waiting for the publication of data about two patients that underwent ovarian corticectomy as a novel technique in fertility sparing [39].

Studies concerning BOT and fertility preservation are summarised in Table 1 with the respective conception rates.

Table 1. BOTs and fertility.

| Study | Patients | Stage | Pregnancies | Patients who conceived | Patients who attempted to conceive |

Conception rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morris et al 2000 | 43 | IA–II | 25 | 12 | 24 | 27.91 |

| Zanetta et al 2001 | 189 | IA–III | 41 | 44 | NR | 23.28 |

| Morice et al 2001 | 44 | IA–III | 17 | 14 | NR | 31.82 |

| Cameatte et al 2002 | 17 | II–III | 8 | 7 | 9 | 41.18 |

| Fauvet et al 2005 | 162 | IA–III | 30 | 21 | 65 | 12.96 |

| Park et al 2009 | 184 | IA–III | 33 | 27 | 31 | 14.67 |

| Uzan et al 2009 | 41 | II–III | 18 | 14 | NR | 34.15 |

NR = not reported

Germ cell tumours

Malignant ovarian germ cell tumours (MOGCTs) are rare cancers (3%–5% of ovarian tumours) but they are the ones that most affect younger women—83% of cases occur in women under the age of 40 years, often in women in their teens and twenties. For this reason, the preservation of fertility is an important aspect in the management of these neoplasms [40]. Thanks to the rapid growth and early symptoms secondary to capsular distension, necrosis and haemorrhage, the tumour is frequently diagnosed in stage I unlike to epithelial OC [40]. Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with peritoneal staging and retroperitoneal staging if indicated, is the treatment of choice in early stage MOGCT with vertical midline incision, careful abdominal exploration with inspection and palpation of all peritoneal surfaces, multiple biopsies of peritoneum, omentectomy, with no survival difference after unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy when MOGCT are confined to one ovary [41]. Bilateral disease is uncommon and no biopsy is advised owing to the risk of extra adhesions and impairment of ovarian reserve unless there are macroscopically suspicious areas in the contralateral ovary [42].

Pure dysgerminoma: several authors suggest fertility-sparing treatment for all stages with a disease-free survival in 10 years of >90% and overall survival 100% [43].

Yolk sac tumours (non-dysgerminomatous tumours): for early stage, fertility-sparing surgery is feasible, in case of a higher stage, standard-dose bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy following fertility-sparing surgery has been associated with favourable overall survival rates and no apparent compromise of fertility rates [44]. Serum alpha-feto-protein (AFP) is a reliable marker for diagnosis and may be used in clinical decision-making after surgery or for advanced disease management [45]. Even though three courses of BEP are the standard adjuvant therapy after conservative surgery for early-stage YST, some patients can also be carefully followed up without treatment if AFP after surgery declines consistently.

Immature ovarian teratoma (non-dysgerminomatous tumours) stage 1 grade 2–3 adjuvant chemotherapy following fertility-sparing surgery has been recommended by some authors, but several studies suggest an expectant approach with BEP only in case of relapse [46]. Reproductive function, on the other hand, has been reported to be relatively good, with more than 80% of patients retaining reproductive function after chemotherapy and surgery [42]. Oocyte cryopreservation could be proposed to all adolescent patients and to all those who have not yet planned a pregnancy and a COH could also be considered after 12 months from CT.

Malignant sex cord-stromal tumours

Malignant sex cord-stromal tumours are rare and include granulosa cell tumours (most common) and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumours; they are typically associated with a good prognosis. Most of the patients with granulosa tumours present with early-stage disease. The disease is typically indolent. Patients with stage IA or IC sex cord-stromal tumours desiring to preserve their fertility should be treated with fertility-sparing surgery. Although complete staging is recommended for all patients, lymphadenectomy may be omitted for stage IA or IC. For patients who choose fertility-sparing surgery, completion surgery should be considered after childbearing is finished. For patients with high-risk stage I tumours (tumour rupture, stage 1C, poorly differentiated tumour and tumour size >10–15 cm), observation or consideration of platinum-based chemotherapy should be indicated. Patients with surgical findings of low-risk stage I tumour (i.e. without high-risk features) should be observed. Inhibin levels can be followed if they were initially elevated [47].

Table 2 summarises studies about granulosa cell tumours and fertility preservation.

Table 2. Granulosa cell tumours and fertility.

| Study | Patients | Stage | Pregnancies | Patients who conceived | Patients who attempted to conceive |

Conception rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low et al 2000 | 74 | IA–IV | 16 | 19 | 20 | 25.68 |

| Zanetta et al 2001 | 138 | IA–IC | 55 | 28 | 32 | 20.29 |

| Tangir et al 2003 | 64 | IA–IV | 47 | 29 | 38 | 45.31 |

| Zanagnolo et al 2004 | 39 | IA–IC | 11 | 36 | NR | 92.31 |

| Nishio et al 2006 | 30 | IA–IV | 4 | 8 | 12 | 26.67 |

| Chan et al 2008 | 313 | IA–IV | NR | 29 | 38 | 9.27 |

NR = not reported

Epithelial tumours

The standard treatment for patients in International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I–II EOC is based on total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, peritoneal sampling, omentectomy, both pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy [48]. According to the available guidelines, in women wishing to maintain fertility, conservative surgery can be performed, for all grades at stage IA or IC [49, 50]. While this approach is still debated for high-risk patients (clear cell, stage> or equal IAG3) [50, 51]. In the recent ESMO and ESGO guidelines, a conservative approach is limited to G1-2 IA and IC EOC with unilateral involvement, in the case of mucinous, serous, endometrioid or mixed histotype [50, 52]. In the largest retrospective series available including 1,189 patients with early EOC, 432 of whom treated conservatively, stage IC and grade 3 were the only independent predictors of survival [53]. Fruscio et al, in a retrospective study, unlike Wright JD, in a 240 patients with malignant early stage/EOC treated with fertility-sparing surgery, confirmed that grade of nuclear differentiation G3 was the only predictor for survival, associated with a significant higher rate of distant recurrence (RFS: Hazard ratio [HR]: 4.2, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5–11.7, P = 0.0067; OS: HR: 7.6, 95% CI: 2.0–29.3, P = 0.0032) [51]. However, patients with G3 tumours, analysed in this study, have a comparable prognosis in terms of disease-free and overall survival compared to patients with G3 neoplasia included in the ICON1/ACTION trial where all women underwent radical surgery [54, 55]. Some studies have indeed shown that in the case of macroscopically undamaged contralateral ovaries, the risk of microscopic involvement was 0%–2.5% [48, 56]. In the case of endometrial histotype, an endometrial biopsy is suggested, while in the case of mucinous histotype, appendectomy is recommended to exclude intestinal origin of tumour. Regarding the surgical procedure, the laparoscopic approach has been described as a feasible technique by several authors [48, 57]. However, tumours greater than 10 cm are probably correlated with a higher risk of rupture and spillage that may occur in 88% versus 9% through laparoscopy compared to laparotomy [58]. In a Bentivegna analysis, it has been observed that most relapses occurring after a conservative surgical approach are extra ovarian, suggesting that the preservation of one ovary is not necessarily the cause of the recurrence [59]. Moreover, the adjuvant therapy in early-stage EOC improves survival and delays recurrence in patients with IC stage, as demonstrated by a multicentre open randomised trial, with 477 patients, in fact, the group who receive adjuvant chemotherapy immediately following surgery had better overall survival (HR of 0.66, 95% CI = 0.45–0.97; P = 0.03) and a recurrence-free survival (HR = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.46–0.91; P = 0.01) [60].

Studies concerning EOCs and fertility are collected in Table 3.

Table 3. Epithelial OCs and fertility.

| Study | Patients | Stage | Pregnancies | Patients who conceived | Patients who attempted to conceive |

Conception rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zanetta et al 1997 | 56 | IA–II | 17 | 20 | NR | 35.71 |

| Morice et al 2001 | 25 | IA–II | 3 | 4 | 4 | 16.00 |

| Schilder et al 2002 | 52 | IA–IC | 26 | 17 | 24 | 32.69 |

| Morice et al 2005 | 34 | IA–IC | 10 | 9 | NR | 26.47 |

| Anchezar et al 2009 | 18 | IA–IIIB | 7 | 6 | 7 | 33.33 |

| Schlaerth et al 2009 | 20 | IA, IC | 9 | 6 | NR | 30.00 |

| Park et al 2008 | 62 | IA–IIIC | 22 | 15 | 19 | 24.19 |

| Raspagliesi et al 1997 | 10 | IA–IC | 2 | 3 | 5 | 30.00 |

| Borgfeldt et al 2007 | 23 | IA, IC | 30 | 15 | NR | 65.22 |

NR = not reported

Otherwise, for healthy BRCA mutated patients with elevated risk for OC, other therapeutic options are adopted.

Currently, mutation carriers should complete childbearing and then undergo a salpingo-oophorectomy around 35–40 years if BRCA1-mutated and 45–50 years if BRCA2 mutated, while concurrent hysterectomy is not recommended [61–64]. Thus, for this group of patients, fertility could be impacted by two different agents: treatments of eventual cancer and prevention strategies. It has been hypothesised that carrying BRCA mutations, especially BRCA1, can be associated with decreased ovarian reserve, increased fertility-related problems and primary ovarian insufficiency that can lead to infertility and early menopause [65]. Despite the strong rationale and preclinical results suggesting this hypothesis, conflicting clinical data are available and they do not show a significant difference among BRCA carriers and non-carriers. Hence, a negative impact of carrying a BRCA mutation, mainly BRCA1 but also BRCA2 [66, 67], on women’s reproductive performance must be kept in consideration. For the lack of reproduction studies about BRCA-mutated breast cancer patients, the safety and efficacy of the different strategies for fertility preservation and the feasibility of having a pregnancy after diagnosis should be considered a research priority [68]. Approaching this group of patients, some authors suggest performing anti-Müllerian hormone measurement and antral follicle count in order to evaluate the ovarian reserve. Therefore, young adults with BRCA mutation should be counselled regarding this potential decrease of ovarian reserve [69].

In cases needing fertility preservation, oocyte cryopreservation could be an option for BRCA-mutated women who undergo surgery not at 40 years old but earlier, when the ovarian reserve and its quality are better [70]. In contrast, ovarian tissue cryopreservation is not recommended, for the increased risk of malignant transformation [71, 72]. However, two live births have been reported in the literature, with uneventful pregnancies, in BRCA-mutated breast cancer patients that underwent ovarian tissue cryopreservation. The former was 16 months after transplantation, with a previous miscarriage—the latter happened with the recovery of ovarian function 5 months after transplantation, followed by a spontaneous pregnancy 3 months later [73, 74].

Salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy, preserving natural follicular cycle, is another option for prophylactic treatment. However, this surgery strategy is still not recommended as the primary approach [62, 63].

Carcinosarcomas

Carcinosarcomas Malignant Mixed Müllerian Tumours (MMMTs) are rare tumours with a poor prognosis. Patients with MMMTs are not candidates for fertility-sparing surgery regardless of age.

Future perspectives

In vitro ovarian follicle growth

The greater risk associated with cryopreserved ovarian tissue autotransplantation is the possibility of a tumour re-implantation and dissemination, also in the contralateral ovary transplantation that could also contain tumour cells [71]. The possibility of using in vitro follicles could represent a chance to preserve fertility in young patients with OC; in fact, recently, mature human follicles have been successfully cultured in vitro to produce metaphase II stage oocytes which could be used for IVF [75, 85]. This technique does not require hormonal stimulation and can also be offered in prepubertal patients.

In vitro ovarian follicle maturation

A future possibility to offer to young cancer patients could be follicular maturation in vitro. In fact, a portion of cortical ovarian cysts from patients with cancer could be treated with phosphatase and tensin homolog inhibitor or AKT activator, determining in vitro ovarian follicle maturation.

These follicles can be kept for future use [76].

Protection against germ cell damage using fertoprotective agents

Fertility sparing surgical approaches in patients with early-stage OC, described above, have some limitations, including cost, time, accessibility to dedicated centres and gonadotoxicity related to procedures. Therefore, the need arises to obtain adjuvants that can inhibit or reduce the side effects of various anticancer drugs with the aim of protecting the pool of dormant follicles.

Some molecules have already been extensively studied for this role, for example, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), imatinib mesylate, amifostin, tamoxifen and GnRH antagonists and agonists. There are emerging studies on the fertoprotective role of melatonin. In fact, melatonin reduces the adverse effects of chemotherapy by removing superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide and peroxyl radical.

However, it is necessary to test agents and to develop new and efficient fetoprotective agents in the preservation of the ovarian reserve for OC patients [77].

Actual and future perspectives for hysterectomised women (beyond uterus transplantation)

Women who must undergo hysterectomy will need to consider other options, such as surrogacy, even if they have cryopreserved oocytes. Recently, successful uterine transplantation was reported but the application of this technique in clinical practice is still limited [78]. Despite the interesting results reported by Brännström M et al about the use of uterus transplantation in either benign and malignant conditions, the use of high doses of immunosuppressive agents, the risk of cancer recurrence in immunocompromised patients and the possible vascular abnormalities after pelvic radiation must be considered before taking this approach in consideration to cancer patients. However, it could represent a revolutionary approach for the management of gynaecologic cancer patients with fertility preservation purposes [78].

Studies about uterus transplantation and its outcomes are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4. Uterus transplantation and outcomes.

| Pts | Age | Cause of uterus absence | Type of transplantation | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fageeh W et al 2002 | 1 | 26 | Post-partum haemorrhage | Allotransplantation from alive donor | Histerectomy for acute vascular thrombosis |

| Ozkan et al 2013 | 1 | 21 | Complete müllerian agenesis | Allotransplantation from a deceased donor | Pregnancy with early miscarriage |

| Brännström et al 2014 Johannesson et al 2015 |

9 | 31.5 | – Eight MRKH – One cervical cancer |

Allotransplantation from alive donor | – Seven uteri remain viable (with mild rejection in four patients reversed with corticosteroids)

– Two severe rejections caused by bilateral thrombotic arterial occlusions |

| Brännström et al 2014 | 1 | 35 | MRKH | Allotransplantation from alive donor | One live birth |

MRKH = Mayer Rokitanscky Küster Hauser syndrome

Conclusions

The mean 5-year survival rate for OC is 47.4% but the cancer stage at diagnosis has a strong influence on the length of survival [79]. Most women with Stage I OC have an excellent prognosis. Stage I patients with grade I tumours have a 5-year survival of over 90%, as do patients in stages IA and IB. These percentages significantly decrease for the other stages: Stage II OC has a 5-year survival rate of approximately 70%, Stage III about 39% and Stage IV only 17% [79]. Other factors impact a woman’s prognosis, including her general health, the grade of cancer and the histotype. Among women with distant disease, a higher risk of mortality was observed within the first 2 years after diagnosis for mucinous, clear cell and carcinosarcoma compared with high-grade serous, with the most striking hazard ratio observed in the first year after diagnosis for mucinous (HR 1⁄4 3.87, 95% CI 1⁄4 3.45–4.34) [80]. Cumulatively, both localised/regional and distant-stage low-grade serous and endometrioid carcinomas had the most favourable outcomes [81]. So, it is clear that different cancers need different approaches. Moreover, it is important to distinguish non-epithelial ovarian neoplasms because guidelines allow gynaecologists to perform more conservative surgery [82–84]. Therefore, since there is no scientific evidence to support a better prognosis with demolitive surgery, conservative surgery can be proposed in the initial stages with adequate counselling. Obviously, the choice must be strictly based on an accurate staging of the disease, surgically reached, and on the evaluation of prognostic factors as grading and histotype.

In the case of negative prognostic factors, chemotherapy can have a fundamental role in allowing a fertility sparing approach.

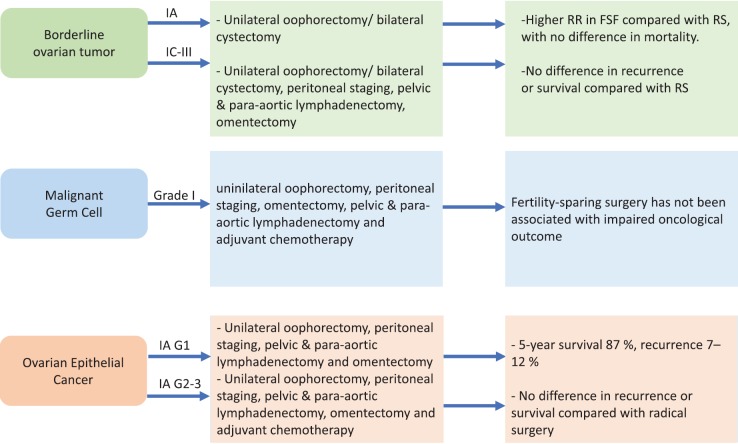

To sum up, it is essential to identify tumours at an initial diagnosis that allows the ovarian and uterus tissue to be maintained because only initial stages can be treated with conservative procedures reducing danger for the patients. Different approaches for each type of tumour are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Fertility sparing strategies in OC patients. RR = recurrence rate, FSF = fertility sparing surgery, RS = radical surgery.

Unfortunately, we know that there is no OC screening test but an annual pelvic ultrasound should be proposed to all women. For their predisposition to develop OC, BRCA-mutated patients are encouraged to perform closer checks and monitoring of the marker, before the oophorectomy, the most effective measure for reducing this risk.

It is true that there will be the possibility of new techniques for patients radically treated (such as uterus transplantation), but this is still very far from common clinical practice.

As long as these methods do not become habitual, early diagnosis, and thus fertility sparing surgery, is the only chance for these women to become pregnant.

Conflicts of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, associated with this article.

Funding

The authors received no funding for the completion of this article.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(6):1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. 2016. [02/04/18]. [ www.cancer.org/cancer/ovariancancer/index]

- 3.Wenzel L, Dogan-Ates A, Habbal R, et al. Defining and measuring reproductive concerns of female cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;(34):94–98. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(2):190. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brearley SG, Stamataki Z, Addington-Hall J, et al. The physical and practical problems experienced by cancer survivors: a rapid review and synthesis of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(3):204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitale SG, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AM, et al. Psychology of infertility and assisted reproductive treatment: the Italian situation. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2017;38(1):1–3. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2016.1244184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laganà AS, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AM, et al. Needs and priorities of women with endometrial and cervical cancer. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2017;38(1):85–86. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2016.1244186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenzel LB, Donnelly JP, Fowler JM, et al. Resilience, reflection, and residual stress in ovarian cancer survivorship: a gynecologic oncology group study. Psychooncology. 2002;11(2):142–153. doi: 10.1002/pon.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCorkle R, Tang ST, Greenwald H, et al. Factors related to depressive symptoms among long-term survivors of cervical cancer. Health Care Women Int. 2006;27(1):45–58. doi: 10.1080/07399330500377507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitale SG, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AM, et al. The consequences of gynaecological cancer in patients and their partners from the sexual and psychological perspective. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017;13(3):598–599. doi: 10.5114/pm.2016.63501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liavaag AH, Dørum A, Fosså SD, et al. Controlled study of fatigue, quality of life, and somatic and mental morbidity in epithelial ovarian cancer survivors: how lucky are the lucky ones? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor JF, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: psychometric evaluation of the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women. Arch Sex Behav. 1994;23(6):627–643. doi: 10.1007/BF01541816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine JM, Kelvin JF, Quinn GP, et al. Infertility in reproductive-age female cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1532–1539. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Telfer EE, McLaughlin M. In vitro development of ovarian follicles. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:15. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1268700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rienzi L, Cobo A, Paffoni A, et al. Consistent and predictable delivery rates after oocyte vitrification: an observational longitudinal cohort multicentric study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(6):1606–1612. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whyte JS, Hawkins E, Rausch M, et al. In vivo oocyte retrieval in a young woman with ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:484–486. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfeifer S, Goldberg J, Lobo R, et al. Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Ovarian tissue cryopreservations: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1237. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2500–2510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oktem O, Urman B. Options of fertility preservation in female cancer patients. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010;65(8):531–542. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181f8c0aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace WH, Thomson AB, Saran F, et al. Predicting age of ovarian failure after radiation to a field that includes the ovaries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62(3):738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suh EK, Yang A, Kettenbach A, et al. p63 protects the female germ line during meiotic arrest. Nature. 2006;444(7119):624–628. doi: 10.1038/nature05337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonfloni S, Di Tella L, Caldarola S, et al. Inhibition of the c-Abl-TAp63 pathway protects mouse oocytes from chemotherapy-induced death. Nat Med. 2009;15(10):1179–1185. doi: 10.1038/nm.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner NH, Partridge A, Sanna G, et al. Utility of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for fertility preservation in young breast cancer patients: the benefit remains uncertain. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(9):2224–2235. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumenfeld Z, Katz G, Evron A. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”: the case for and against GnRH-agonist for fertility preservation. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(9):1719–1728. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Wallberg K, Turan V, Munster P, et al. Can ovarian suppression with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRHa) preserve fertility in cancer patients? Ann Oncol. 2016;27(2):257. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambertini M, Falcone T, Unger JM, et al. Debated role of ovarian protection with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists during chemotherapy for preservation of ovarian function and fertility in women with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(7):804–805. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambertini M, Dellepiane C, Viglietti G, et al. Pharmacotherapy to protect ovarian function and fertility during cancer treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(8):739–742. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1316373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambertini M, Del Mastro L, Viglietti G, et al. Ovarian function suppression in premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18(1):4. doi: 10.1007/s11864-017-0442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambertini M, Boni L, Michelotti A, et al. Ovarian suppression with triptorelin during adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy and long-term ovarian function, pregnancies, and disease-free survival: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(24):2632–2640. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore HCF, Unger JM, Albain KS. Goserelin for ovarian protection during breast-cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2015;72(10):923–932. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonard R, Adamson DJA, Bertelli G, et al. GnRH agonist for protection against ovarian toxicity during chemotherapy for early breast cancer: the Anglo Celtic Group OPTION trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1811–1816. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skirnisdottir I, Garmo H, Wilander E, et al. Borderline ovarian tumors in Sweden 1960–2005: trends in incidence and age at diagnosis compared to ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1897–1901. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanetta G, Rota S, Chiari S, et al. Behavior of borderline tumors with particular interest to persistence, recurrence, and progression to invasive carcinoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2658–2664. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patrono MG, Minig L, Diaz-Padilla I, et al. Borderline tumours of the ovary, current controversies regarding their diagnosis and treatment. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013;7:379. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2013.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uzan C, Muller E, Kane A, et al. Prognostic factors for recurrence after conservative treatment in a series of 119 patients with stage I serous borderline tumors of the ovary. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:166–171. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darai E, Fauvet R, Uzan C, et al. Fertility and borderline ovarian tumor: a systematic review of conservative management, risk of recurrence and alternative options. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:151–166. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denschlag D, von Wolff M, Amant F, et al. Clinical recommendation on fertility preservation in borderline ovarian neoplasm: ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrieval after conservative surgery. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2010;70:160–165. doi: 10.1159/000316264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ovarian corticectomy: novel surgical technique in fertility sparing surgery for borderline tumor of the ovary. 17th Biennial Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society IGCS; September 14–16, 2018; Kyoto. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith HO, Berwick M, Verschraegen CF, et al. Incidence and survival rates for female malignant germ cell tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1075–1085. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000216004.22588.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Kassanos D. Germ cell tumors of the ovary. Cancer Treat. 2008;34:427–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gershenson DM. Management of ovarian germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2938–2943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mangili G, Sigismondi C, Lorusso D, et al. Is surgical restaging indicated in apparent stage IA pure ovarian dysgerminoma? The MITO group retrospective experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de La Motte RT, Pautier P, Duvillard P, et al. Survival and reproductive function of 52 women treated with surgery and bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy for ovarian yolk sac tumor. AnnOncol. 2008;19:1435–1441. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dallenbach P, Bonnefoi H, Pelte MF, et al. Yolk sac tumours of the ovary: an update. EJSO. 2006;32:106–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vicus D, Beiner ME, Clarke B, et al. Ovarian immature teratoma: treatment and outcome in a single institutional cohort. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hölscher G, Anthuber C, Bastert G, et al. Improvement of survival in sex cord stromal tumors - an observational study with more than 25 years follow-up. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:440. doi: 10.1080/00016340902741208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomao F, Peccatori F, Del Pup L, et al. Special issues in fertility preservation for gynecologic malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;97:206–219. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National comprehensive cancer network. Ovarian cancer (Version1.2017) [ https://www.nccn.org/professionals/phys-ician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf]

- 50.Morice P, Denschlag D, Rodolakis A, et al. Recommendations of the Fertility Task Force of the European Society of Gynecologic Oncology about the conservative management of ovarian malignant tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(5):951–963. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821bec6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fruscio R, Corso S, Ceppi L, et al. Conservative management of early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: results of a large retrospective series. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:138–144. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ditto A, Martinelli F, Bogani G, et al. Long-term safety of fertility sparing surgery in early stage ovarian cancer: comparison to standard radical surgical procedures. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Fanfani F, et al. Laparoscopic fertility-sparing surgery for early ovarian epithelial cancer: a multi-institutional experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trimbos JB, Vergote I, Bolis G, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy and surgical staging in early-stage ovarian carcinoma: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:113–125. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trimbos B, Timmers P, Pecorelli S, et al. Surgical staging and treatment of early ovarian cancer: long-term analysis from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(13):982–987. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benjamin I, Morgan MA, Rubin SC. Occult bilateral involvement in stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72(3):288–291. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martinez A, Poilblanc M, Ferron G, et al. Fertility-preserving surgical procedures, techniques. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26(3):407–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peccatori FA, Mangili G, Bergamini A, et al. Fertility preservation in women harboring deleterious BRCA mutations: ready for prime time? Hum Reprod. 2018;33(2):181–187. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bentivegna S, Gouy S, Maulard A, et al. Fertility-sparing surgery in epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review of oncological issues. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(11):1994–2004. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Colombo N, Guthrie D, Chiari S, et al. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial 1: a randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with early-stage ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(2):125–132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Daly MB, Pilarski R, Berry M, et al. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. Version 2.2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Paluch-Shimon S, Cardoso F, Sessa C, et al. Prevention and screening in BRCA mutation carriers and other breast/ovarian hereditary cancer syndromes: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for cancer prevention and screening. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(Suppl 5):v103–v110. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Felice F, Marchetti C, Boccia SM, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutated patients: an evidence-based approach on what women should know. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;61:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de la Noval BD. Potential implications on female fertility and reproductive lifespan in BRCA germline mutation women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294(5):1099–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharan SK, Pyle A, Coppola V, et al. BRCA2 deficiency in mice leads to meiotic impairment and infertility. Development. 2004;131(1):131–142. doi: 10.1242/dev.00888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Connor F, Bertwistle D, Mee PJ, et al. Tumorigenesis and a DNA repair defect in mice with a truncating Brca2 mutation. Nat Genet. 1997;17(4):423–430. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lambertini M, Goldrat O, Toss A, et al. Fertility and pregnancy issues in Brca-mutated breast cancer patients. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;59:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daum H, Peretz T, Laufer N. BRCA mutations and reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peccatori FA, Mangili G, Bergamini A, et al. Fertility preservation in women harboring deleterious BRCA mutations: ready for prime time? Hum Reprod. 2018;33(2):181–187. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tanbo T, Greggains G, Storeng R, et al. Autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue after treatment for malignant disease - the first Norwegian results. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(9):937–941. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mueller A, Maltaris T, Dimmler A, et al. Development of sex cord stromal tumors after heterotopic transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in rats. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:4107–4111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jensen AK, Macklon KT, Fedder J, et al. 86 successful births and 9 ongoing pregnancies worldwide in women transplanted with frozen-thawed ovarian tissue: focus on birth and perinatal outcome in 40 of these children. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:325–336. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0843-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lambertini M, Goldrat O, Ferreira AR, et al. Reproductive potential and performance of fertility preservation strategies in BRCA-mutated breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:237–243. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim SY, Kim SK, Lee JR, et al. Toward precision medicine for preserving fertility in cancer patients: existing and emerging fertility preservation options for women. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27(2):e22. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xiao S, Zhang J, Romero MM, et al. In vitro follicle growth supports human oocyte meiotic maturation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17323. doi: 10.1038/srep17323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li J, Kawamura K, Cheng Y, et al. Activation of dormant ovarian follicles to generate mature eggs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(22):10280–10284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001198107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jang H, Hong K, Choi Y. Melatonin and fertoprotective adjuvants: prevention against premature ovarian failure during chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1221. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brännström M, Diaz-Garcia C, Johannesson L, et al. Livebirth after uterus transplantation. Lancet. 2015;385(9968):607–616. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61728-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. [ https://www.cancer.gov/types/ovarian]

- 80.Peres LC, Cushing-Haugen KL, Köbel M, et al. Invasive epithelial ovarian cancer survival by histotype and disease stage. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81. [ https://www.practiceupdate.com/content/survival-in-ovarian-cancer-varies-by-histotype/67656]

- 82.Ray-Coquard I, Morice P, Lorusso D, et al. Non-epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Supplement_4):iv1–iv18. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:24–32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Felice F, Marchetti C, Di Pinto A, et al. Fertility preservation in gynaecologic cancers. ecancer. 2018;12(798) doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2018.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim SY, Lee JR. Fertility preservation option in young women with ovarian cancer. Future Oncol. 2016;12(14) doi: 10.2217/fon-2016-0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]