Abstract

Background

Reproductive function in women with end stage renal disease generally improves after kidney transplant. However, pregnancy remains challenging due to the risk of adverse clinical outcomes.

Methods

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Elsevier EMBASE, Scopus, BIOSIS Previews, ISI Science Citation Index Expanded, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from date of inception through August 2017 for studies reporting pregnancy with kidney transplant.

Results

Of 1343 unique studies, 87 met inclusion criteria, representing 6712 pregnancies in 4174 kidney transplant recipients. Mean maternal age was 29.6 ± 2.4 years. The live-birth rate was 72.9% (95% CI, 70.0–75.6). The rate of other pregnancy outcomes was as follows: induced abortions (12.4%; 95% CI, 10.4–14.7), miscarriages (15.4%; 95% CI, 13.8–17.2), stillbirths (5.1%; 95% CI, 4.0–6.5), ectopic pregnancies (2.4%; 95% CI, 1.5–3.7), preeclampsia (21.5%; 95% CI, 18.5–24.9), gestational diabetes (5.7%; 95% CI, 3.7–8.9), pregnancy induced hypertension (24.1%; 95% CI, 18.1–31.5), cesarean section (62.6, 95% CI 57.6–67.3), and preterm delivery was 43.1% (95% CI, 38.7–47.6). Mean gestational age was 34.9 weeks, and mean birth weight was 2470 g. The 2–3-year interval following kidney transplant had higher neonatal mortality, and lower rates of live births as compared to > 3 year, and < 2-year interval. The rate of spontaneous abortion was higher in women with mean maternal age < 25 years and > 35 years as compared to women aged 25–34 years.

Conclusion

Although the outcome of live births is favorable, the risks of maternal and fetal complications are high in kidney transplant recipients and should be considered in patient counseling and clinical decision making.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12882-019-1213-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Kidney transplant, Maternal, Fetal, Outcomes

Background

Women with end stage renal disease have impaired fertility due to disruption of hypothalamic gonadal axis. Pregnancy is therefore rare in women on dialysis with very low incidence of conception ranging from 0.9 to 7% [1]. Since there is rapid restoration of fertility, in some cases, within 6 months following transplantation, kidney transplantation offers the best hope to women with end-stage renal disease who wish to become pregnant [2].

Pregnancy in a kidney transplant recipient continues to remain challenging due to risk of adverse maternal complications of preeclampsia and hypertension, and risk of adverse fetal outcomes of premature birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age infants [3]. Additionally, there is risk of side effects from immunosuppressive medication, and risk of deterioration of allograft function [4]. Therefore, preconception counseling, family planning and contraception are pertinent parts of the transplant counseling process.

Data on clinical outcomes of pregnancy in kidney transplant recipients is limited from case reports, single-center studies, and voluntary registries. The usefulness of the voluntary registries is further limited due to underreporting and incomplete data capture [5–8]. To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive metanalysis on post-kidney transplant pregnancy outcomes has been performed in the recent years [9]. Since kidney transplant is common in women of child bearing age and most of the data on outcomes of pregnancy comes from these retrospective studies, our metaanalysis is both timely and important. The comprehensive analysis of various worldwide registries, single-center studies, and case series will provide generalizable inferences about post-kidney transplant pregnancy outcomes, and help guide the pregnancy in kidney transplant recipients. The primary goal of this study was to perform a meta-analysis to systematically identify all studies of pregnancy-related outcomes in kidney transplant recipients from all around the world, and estimate pooled incidences of pregnancy outcomes, maternal complications, and fetal complications. The secondary goals were to examine the impact of pregnancy on the kidney allograft loss, allograft rejection, identify ideal maternal age of conception, and determine ideal time of conception between kidney transplant and pregnancy.

Methods

Data sources and searches

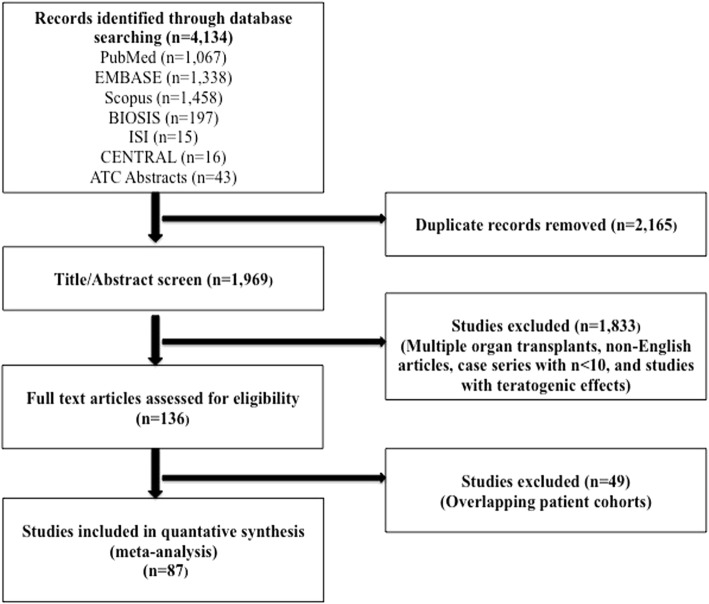

We performed a systematic review and meta-analyses reported according to PRISMA guidelines for studies exploring incidence and outcomes of pregnancy in women with kidney transplant (Fig. 1). We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Elsevier EMBASE, Scopus, BIOSIS Previews, ISI Science Citation Index Expanded, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from their earliest date of inception through 8/31/2017, and abstracts from the annual American Transplant Congresses from 1/1/2013 through 8/31/2017. A health sciences librarian (E.K.) developed database-specific search strategies including a combination of subject headings (MeSH or Emtree) and keywords. The following key search terms were used in strategies specific to each database and organization: pregnancy complications, pregnancy outcome, maternal outcome, fetal outcome, birth outcome, kidney transplant, or renal transplant. A reproducible PubMed search strategy is provided in Additional file 1.

Fig. 1.

Study cohort showing the selection of studies reporting outcomes of pregnancies in women with kidney transplant

Study selection

We considered observational studies (prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, and cross-sectional), case series, and case reports (with n > 10 pregnancies) that explored the pregnancy, maternal, and fetal outcomes among women ≥18 years, and who received a kidney transplant. Studies of patients with multiple organ transplants, studies that analyzed the teratogenic effects of mycophenolate or sirolimus, and non–English language studies were excluded. Titles and abstracts of all identified citations were screened independently by two reviewers (S.S. and T.G.), who discarded studies that did not meet all inclusion criteria. The same reviewers independently screened the abstracts of all eligible studies. If eligibility was indeterminable from the abstract, the study was included in the full-text screen. All disagreements were adjudicated by the principal investigator (S.S).

Data extraction, quality assessment, and outcomes

Data extraction was carried out independently by three data extraction team members (A.G, L.R. and M.S.) using standard data extraction forms. Data elements were then rechecked for accuracy by all the three data extraction team members. When more than one publication of a similar patient population existed with more than 25% overlap, publication with higher number of pregnancy events and the most complete details was included. Disagreements in data extraction and quality assessment were resolved in consultation with an arbitrator (T.G.) and primary investigator (S.S.). For each included study, the following data was extracted: country of location, years of data collection, number of kidney transplant recipients, number of pregnancies, mean maternal age, mean interval between kidney transplant and pregnancy, pregnancy outcomes (number of live births, miscarriage, induced abortion, still birth and ectopic pregnancies), maternal outcomes (number of women with preeclampsia, pregnancy induced hypertension, and gestational diabetes mellitus, and number of cesarean sections), fetal outcomes (number of pre-term births, mean gestational age, mean gestational weight, and number of neonatal deaths); and graft outcomes (number of acute rejection during pregnancy, graft failure post pregnancy, mean serum creatinine pre and post pregnancy). To maintain consistency across extracted data, the number of pregnancies was used as a denominator for the outcomes of live births, miscarriages, induced abortions, stillbirths, neonatal deaths, preeclampsia, pregnancy induced hypertension, and gestational diabetes mellitus. The number of live births was used as the denominator for the outcome of preterm deliveries, and cesarean section. Preterm was defined as babies born alive before 37 weeks gestation.

Data synthesis and analysis

Patients characteristics were reported as frequencies. The pregnancy incidence was reported for women per 1000 live births. For each study, estimates were expressed as prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Prevalence estimates from individual studies were pooled using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity across included studies was analyzed formally using Cochran Q (heterogeneity 2) and I2 statistics. For binary outcomes, the DerSimonian-Laird method was used, and for continuous outcomes, a weighted average methodology was used to calculate the pooled estimates and 95% CI. Two-sample test of proportions was used to compare the pooled incidence for each analysis to the most recent United States (US) general population incidence. [10–14] We determined the associations of maternal age, the interval between kidney transplant, and the pregnancy outcomes. Additonally, we performed a subgroup analysis for the pregnancy, maternal and fetal outcomes for studies published from 2000 to 2017. Analyses were performed using MS Excel and Comprehensive Meta-analysis packages in R software.

Results

Among the 4134 citations that were retrieved, 136 full-text articles were reviewed and 87 were selected to be included in the final study cohort (Fig. 1). Three studies were from Africa, 31 from Asia, 31 from Europe, 10 from North America, 4 from Oceania, and 8 from South America (Table 1). Overall, there were 6712 pregnancies in 4174 kidney transplant recipients. Mean maternal age was 29.6 ± 2.4 years and mean interval between kidney transplant and pregnancy was 3.7 years.

Table 1.

Studies included in the metaanalysis

| Reference, Year Published | Study Years | Country | Recipients | Pregnancies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Devresse et al., 2017 [32] | 1994–2010 | Belgium | 32 | 57 |

| 2 | Yuksel et al., 2017 [33] | 2009–2016 | Turkey | 25 | na |

| 3 | Ajaimy et al., 2016 [34] | 2009–2014 | USA | 11 | 11 |

| 4 | Candido et al., 2016 [35] | 2004–2014 | Portugal | 36 | 53 |

| 5 | Cristelli et al., 2016 [36] | 2004–2014 | Brazil | 36 | 53 |

| 6 | El Houssni et al., 2016 [37] | na | Saudi Arabia | 12 | 21 |

| 7 | Lima et al., 2016 [38] | 2004–2014 | Brazil | 36 | 53 |

| 8 | Majak et al., 2016 [39] | 1969–2013 | Norway | na | 119 |

| 9 | Mishra et al., 2016 [40] | 2004–2014 | India | 16 | na |

| 10 | Orihuela et al., 2016 [41] | 1986–2014 | Uruguay | 32 | 40 |

| 11 | Piccoli et al., 2016 [42] | 1978–2013 | Italy | na | 189 |

| 12 | Saliem et al., 2016 [43] | 2006–2011 | Canada | na | 264 |

| 13 | Santos et al., 2016 [44] | 2010–2014 | Portugal | 8 | 8 |

| 14 | Sarween et al., 2016 [45] | 2001–2015 | UK | 387 | 569 |

| 15 | Stoumpos et al., 2016 [46] | 1973–2013 | UK | 89 | 138 |

| 16 | Yoshikawa et al., 2016 [47] | na | Japan | 49 | 65 |

| 17 | Aktrurk et al., 2015 [48] | 2004–2014 | Turkey | 12 | 16 |

| 18 | Arab et al., 2015 [49] | 2003–2010 | Canada | na | 375 |

| 19 | Erman et al., 2015 [50] | 1987–2011 | Turkey | 43 | 43 |

| 20 | Yeon et al., 2015 [51] | 1995–2015 | Korea | 84 | 119 |

| 21 | Debska – Slizien et al., 2014 [52] | 1980–2012 | Poland | 17 | 22 |

| 22 | Farr et al., 2014 [53] | 1999–2013 | Austria | 12 | 12 |

| 23 | Hebral et al., 2014 [54] | 1969–2011 | France | 46 | 61 |

| 24 | You et al., 2014 [55] | 1995–2013 | Korea | 29 | 41 |

| 25 | Blume et al., 2013 [56] | 1988–2010 | Germany | 34 | 53 |

| 26 | Guella et al., 2013 [57] | 1992–2008 | Saudi Arabia | 15 | 33 |

| 27 | Pietrzak et al., 2013 [58] | 2001–2012 | Poland | 34 | 40 |

| 28 | Rachdi et al., 2013 [59] | 2003–2013 | Tunisia | 12 | 17 |

| 29 | Ribeiro et al., 2013 [60] | 1995–2007 | Brazil | 22 | 31 |

| 30 | Rocha et al., 2013 [61] | 1983–2009 | Portugal | 24 | 25 |

| 31 | Wyld et al., 2013 [62] | 1971–2010 | Australia | 447 | 692 |

| 32 | Kennedy et al., 2012 [63] | na | Ireland | 18 | 29 |

| 33 | Neyatani et al., 2012 [64] | 1975–2011 | Japan | 22 | 34 |

| 34 | Van Buren et al., 2012 [65] | 1971–2010 | Netherlands | 30 | 42 |

| 35 | Celik et al., 2011 [66] | 1998–2008 | Turkey | 24 | 31 |

| 36 | Gerlei et al., 2011 [67] | 1974–2010 | Hungary | 23 | 27 |

| 37 | Lopez et al., 2011 [68] | 1986–2010 | Spain | 20 | 24 |

| 38 | Xu et al., 2011 [69] | 1989–2008 | China | 25 | 38 |

| 39 | Gorgulu et al., 2010 [70] | 1983–2008 | Turkey | 19 | 22 |

| 40 | Areia et al., 2009 [71] | 1989–2007 | Portugal | 28 | 34 |

| 41 | Gill et al., 2009 [20] | 1990–2003 | USA | 483 | 530 |

| 42 | Levidiotis et al., 2009 [8] | 1966–2005 | Australia | 381 | 577 |

| 43 | Rizvi et al., 2009 [72] | 1985–2008 | Pakistan | 45 | 72 |

| 44 | Sharma et al., 2009 [73] | 1988–2006 | Oman | 42 | 82 |

| 45 | Al Duraihimh et al., 2008 [74] | 1996–2006 | Middle East | 140 | 234 |

| 46 | Alfi A Yet al, 2008 [75] | 1989–2005 | Saudi Arabia | 12 | 20 |

| 47 | Cruz Lemini et al., 2007 [28] | 1990–2005 | Mexico | 60 | 75 |

| 48 | Oliveira et al., 2007 [76] | 2001–2005 | Brazil | 52 | 52 |

| 49 | Sibanda et al., 2007 [77] | 1994–2001 | UK | 176 | 193 |

| 50 | Yassaee et al., 2007 [78] | 1996–2001 | Iran | 74 | 95 |

| 51 | Kurata et al., 2006 [79] | 1984–2003 | Japan | 42 | 53 |

| 52 | Rahamimov et al., 2006 [80] | 1983–1998 | Israel | 39 | 69 |

| 53 | Galdo et al., 2005 [81] | 1982–2002 | Chile | 30 | 37 |

| 54 | Garcia - Donaire et al., 2005 [82] | 1997–2004 | Spain | 16 | 19 |

| 55 | Ghanem et al., 2005 [83] | 1989–2004 | Egypt | 41 | 67 |

| 56 | Pour-Reza-Gholi et al., 2005 [84] | 1984–2004 | Iran | 60 | 74 |

| 57 | Yildirim et al., 2005 [85] | 1998–2005 | Turkey | 17 | 20 |

| 58 | Keitel et al., 2004 [86] | 1977–2001 | Brazil | 41 | 44 |

| 59 | Pezeshki et al., 2004 [87] | 1991–1998 | Iran | 18 | 20 |

| 60 | Hooi et al., 2003 [88] | 1984–2001 | Malaysia | 46 | 72 |

| 61 | Queipo et al., 2003 [89] | 1980–2000 | Spain | 29 | 40 |

| 62 | Thompson et al., 2003 [90] | 1976–2001 | UK | 24 | 48 |

| 63 | Sgro et a,l 2002 [91] | 1988–1998 | Canada | 26 | 44 |

| 64 | Tan et al., 2002 [92] | 1986–2000 | Singapore | 25 | 42 |

| 65 | Park et al., 2001 [93] | na - 2000 | South Korea | 36 | 47 |

| 66 | Kuvacic et al., 2000 [94] | 1986–1996 | Croatia | 15 | 23 |

| 67 | Little et al., 2000 [27] | 1985–1998 | Ireland | 19 | 29 |

| 68 | Moon et al., 2000 [95] | na - 1998 | Korea | 36 | 48 |

| 69 | Ventura et al., 2000 [96] | 1983–1999 | Portugal | 15 | 15 |

| 70 | Arsan et al., 1997 [97] | na | France | 20 | 33 |

| 71 | Rahbar et al., 1997 [98] | 1985–1993 | Iran | 13 | 14 |

| 72 | Rieu et al., 1997 [99] | 1970–1995 | France | 22 | 33 |

| 73 | Al Hassani et al., 1995 [100] | 1985–1993 | Oman | 25 | 44 |

| 74 | Sabagh et al., 1995 [101] | 1984–1994 | Saudi Arabia | 33 | 52 |

| 75 | Saber et al., 1995 [102] | 1968–1992 | Brazil | 19 | 25 |

| 76 | Wong et al., 1995 [103] | 1972–1992 | New Zealand | 9 | 16 |

| 77 | Hadi et al., 1986 [104] | 1969–1992 | South Korea | 11 | 13 |

| 78 | Talaat et al., 1994 [105] | 1977–1992 | Sweden | 19 | 25 |

| 79 | Pahl et al., 1993 [106] | 1969–1990 | USA | 21 | 32 |

| 80 | Muirhead et al., 1992 [107] | 1977–1988 | UK | 22 | 22 |

| 81 | Brown et al., 1991 [108] | 1965–1989 | Ireland | 14 | 27 |

| 82 | Sturgiss et al., 1991 [109] | 1967–1987 | UK | 17 | 22 |

| 83 | O’ Connell et al., 1989 [110] | 1974–1986 | Australia | 11 | 18 |

| 84 | Ha et al., 1994 [111] | 1970–1982 | USA | 13 | 17 |

| 85 | Marushak et al., 1986 [112] | 1972–1983 | Denmark | 20 | 24 |

| 86 | O’ Donnell et al., 1985 [113] | 1971–1984 | South Africa | 21 | 38 |

| 87 | Waltzer et al., 1980 [114] | na | USA | 12 | 15 |

na not available

Pregnancy outcomes

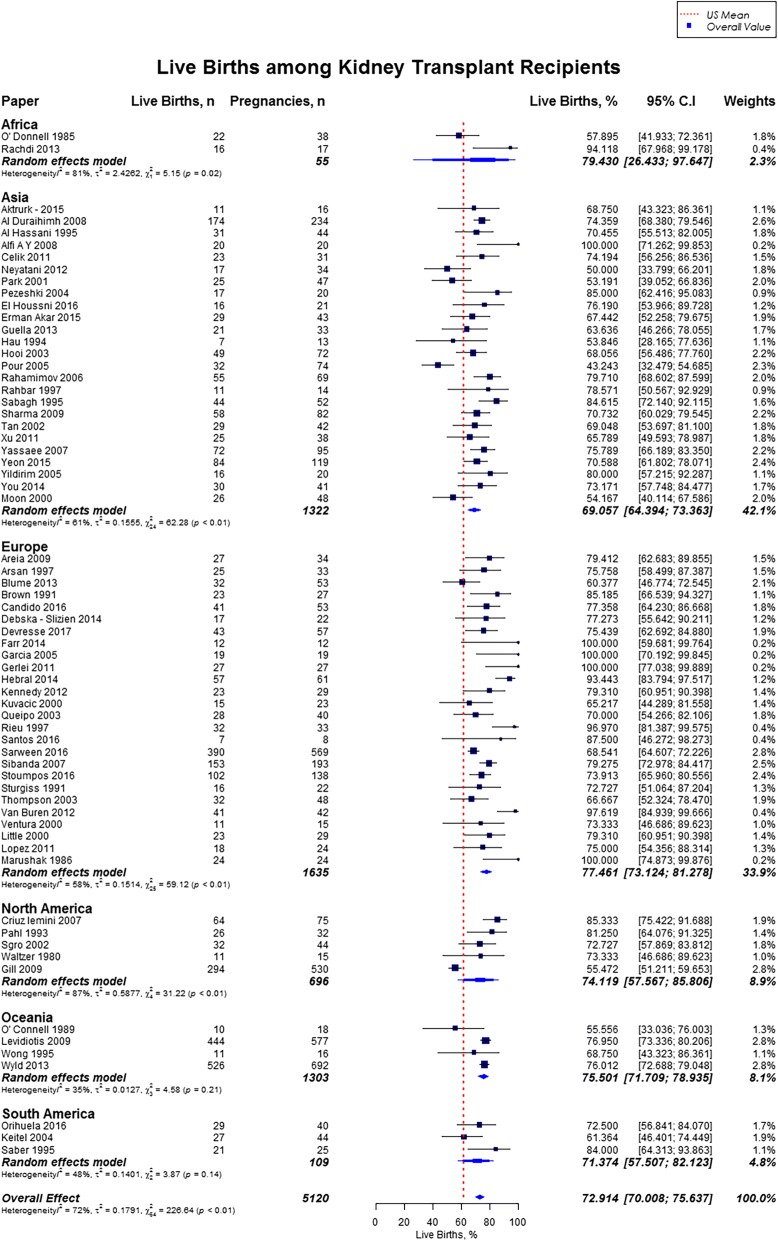

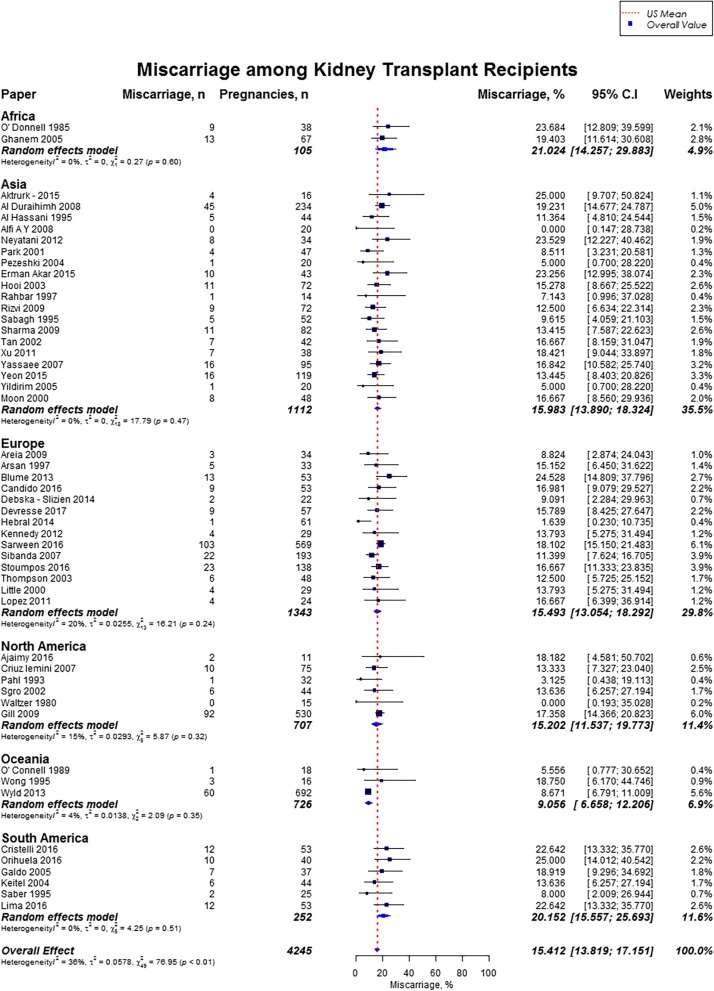

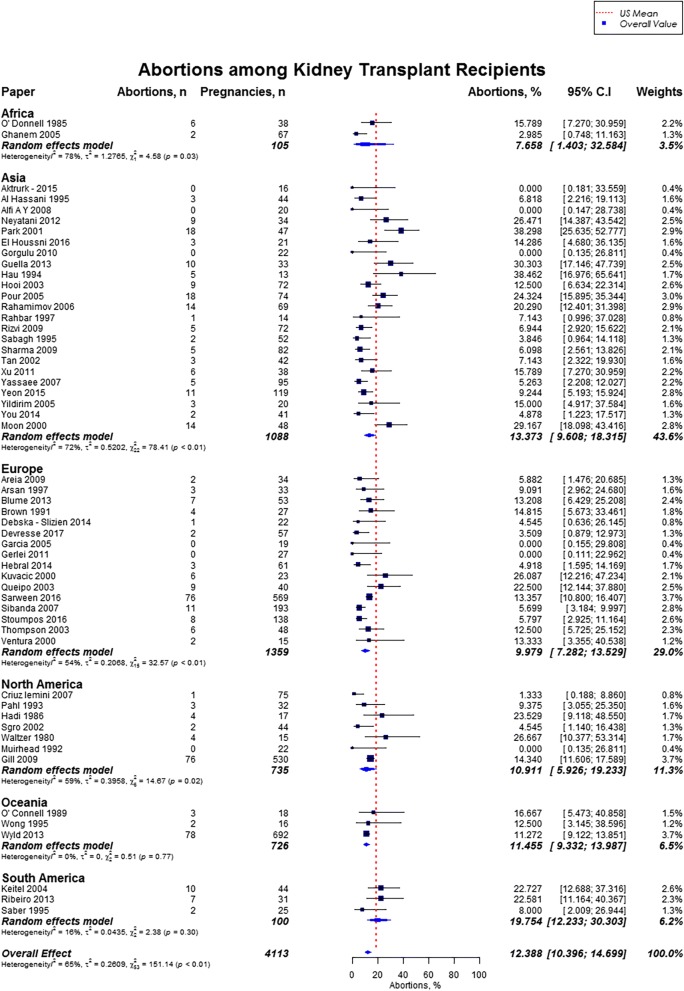

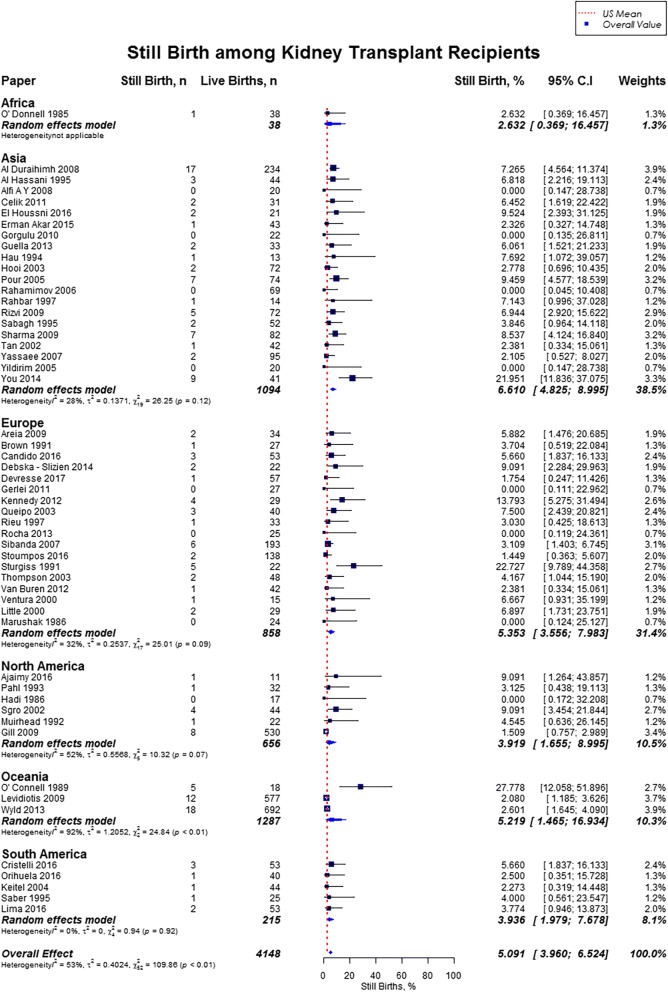

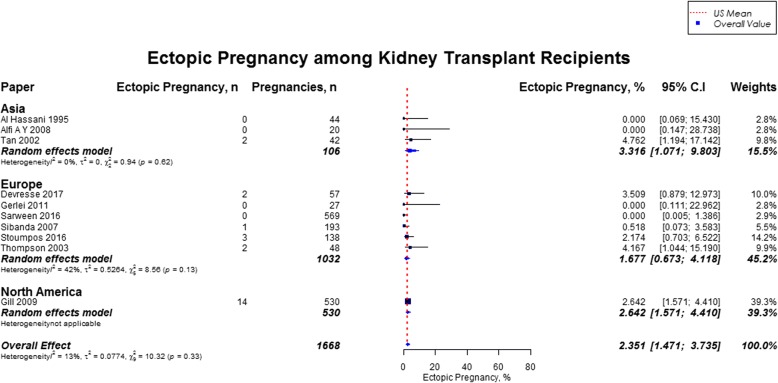

Live birth rate was 72.9% (95% CI, 70.0–75.6), miscarriages rate was 15.4% (95% CI, 13.8–17.2), induced abortions rate was 12.4% (95% CI, 10.4–14.7), stillbirths rate was 5.1% (95% CI, 4.0–6.5) and rate of ectopic pregnancies was 2.4% (95% CI, 1.5–3.7). In our study cohort of kidney transplant recipients, live birth rates were higher as compared to the US general population (72.9% vs. 62%) and favorable across all geographic regions (Fig. 2) [10, 11]. Overall, miscarriage rate was slightly lower than that of the US general population (15.4% vs. 17.1%), but higher across Africa (21.0%; 95% CI, 14.3–29.9), and South America (20.2%; 95% CI, 15.6–25.7) (Fig. 3) [13]. Induced abortion rate was also lower than the US general population (12.4% vs. 18.6%) [13]. The rate of induced abortion was highest in South America (19.8%; 95% CI, 12.2–30.3), followed by Asia (13.3%; 95% CI, 9.6–18.3), Oceania (11.5%; 95% CI, 9.3–14.0), North America (10.9%; 95% CI, 5.9–19.2), Europe (10.0%; 95% CI, 7.3–13.5), and Africa (7.7, 95% CI, 1.4–32.6) (Fig. 4). Overall, stillbirth rate was higher than the US general population (5.1% vs. 0.6%) [14]. Worldwide, stillbirth rate was highest in Asia (6.6, 95% CI, 4.8–9.0%), and lowest in Africa (2.6, 95% CI; 0.4–16.5) (Fig. 5). The rate of ectopic pregnancy was slightly higher than the US general population (2.4% vs. 1.4%), with highest rate in Asia (3.3, 95% CI; 1.1–9.8) (Fig. 6) [15]. The results from the subgroup analyses (2000–2017) for pregnancy outcomes were consistent with the current findings (Additional file 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest Plot showing outcome of live births among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Fig. 3.

Forest Plot showing outcome of miscarriages among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Fig. 4.

Forest Plot showing outcome of induced abortions among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Fig. 5.

Forest Plot showing outcome of still births among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Fig. 6.

Forest Plot showing outcome of ectopic pregnancies among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

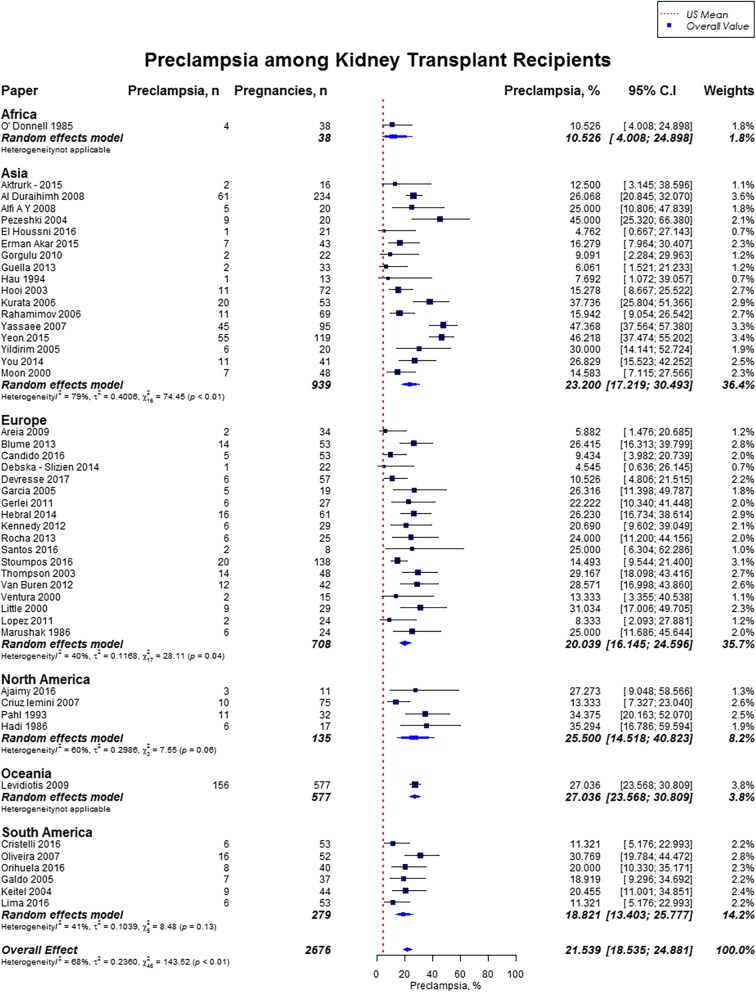

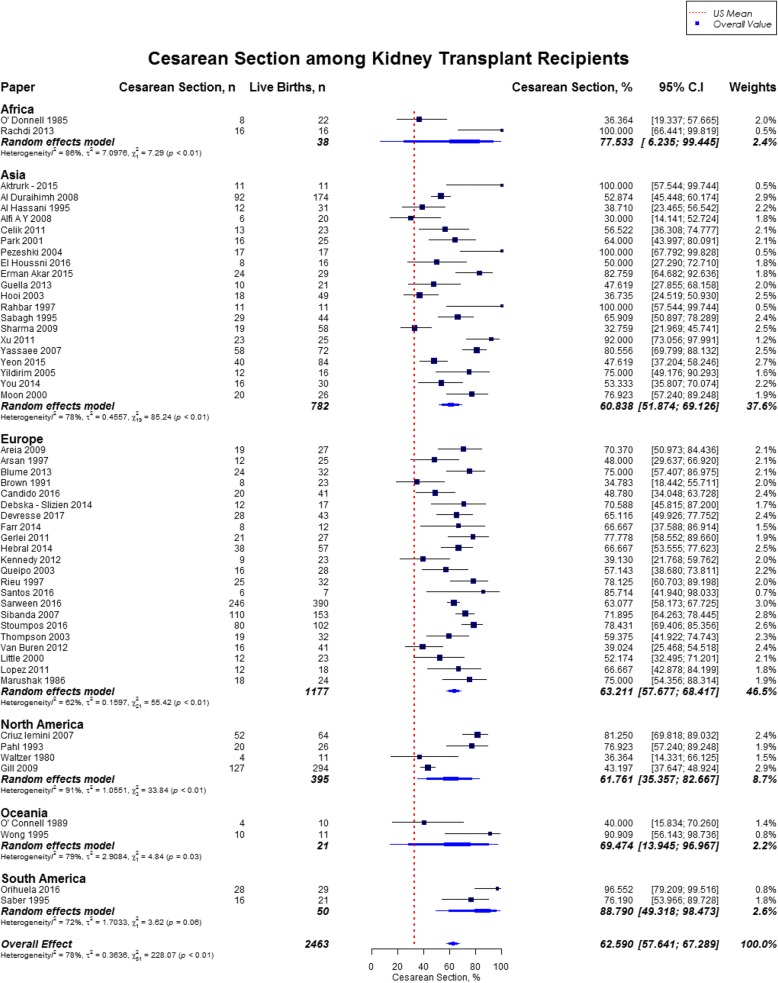

Maternal outcomes

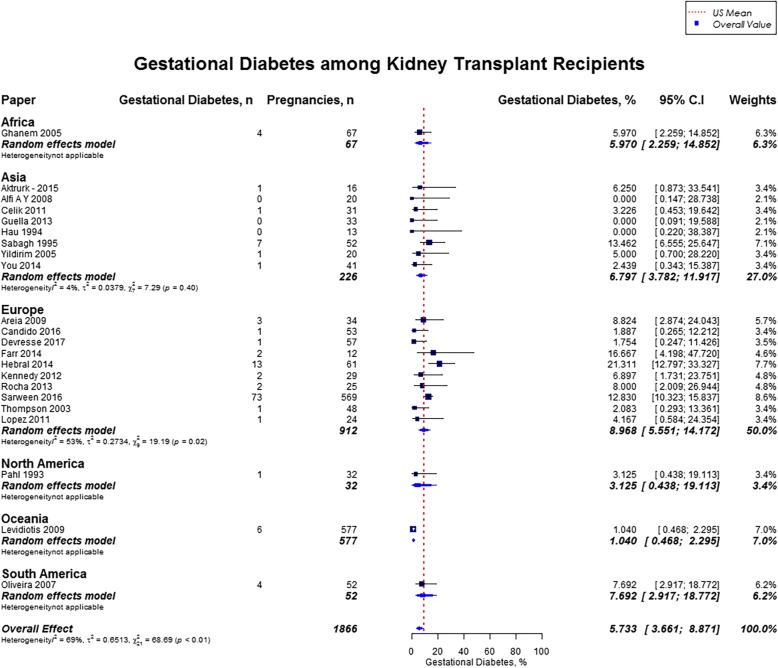

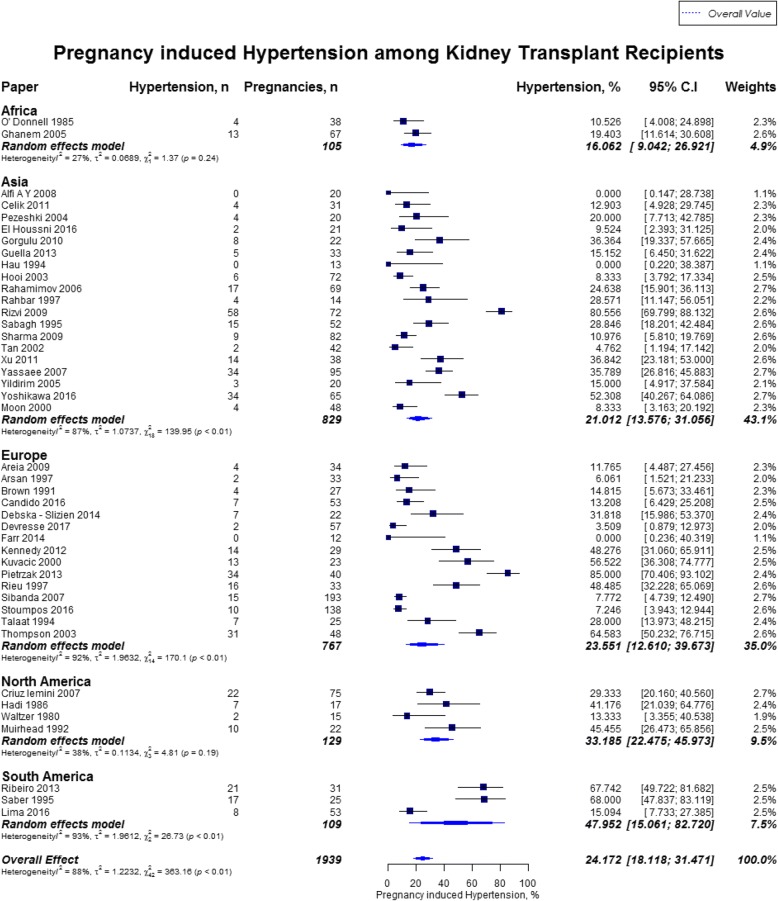

Overall, rates of preeclampsia was 21.5% (95% CI, 18.5–24.9; US mean, 3.8%), cesarean section was 62.6% (95% CI, 57.6–67.3; US mean, 31.9%), gestational diabetes was 5.7% (95% CI, 3.7–8.9; US mean, 9.2%), and pregnancy induced hypertension was 24.1% (95% CI, 18.1–31.5). [12, 16] Preeclampsia rate was highest in Oceania (27.0%; 95% CI, 23.6–30.8), followed by North America (25.5%; 95% CI, 14.5–40.8), and lowest in Africa (10.5%; 95% CI, 4.0–24.9%) (Fig. 7). Cesarean section rate was highest in South America (88.8%; 95% CI, 49.3–98.5), followed by Africa (77.5%; 95% CI, 6.3–99.4) (Fig. 8). Worldwide, Oceania had the lowest rates of gestational diabetes (1.0%; 95% CI, 0.5–2.3%) (Fig. 9). With regards to pregnancy induced hypertension, highest rate was reported in South America (48.0, 95% CI, 15.1–82.7), while lowest rate was in Africa (16.1, 95% CI, 9–26.9) (Fig. 10). The results from the subgroup analyses (2000–2017) for maternal outcomes were consistent with the current findings (Additional file 2).

Fig. 7.

Forest Plot showing outcome of preeclampsia among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Fig. 8.

Forest Plot showing outcome of cesarean section among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Fig. 9.

Forest Plot showing outcome of gestational diabetes among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Fig. 10.

Forest Plot showing outcome of pregnancy induced hypertension among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

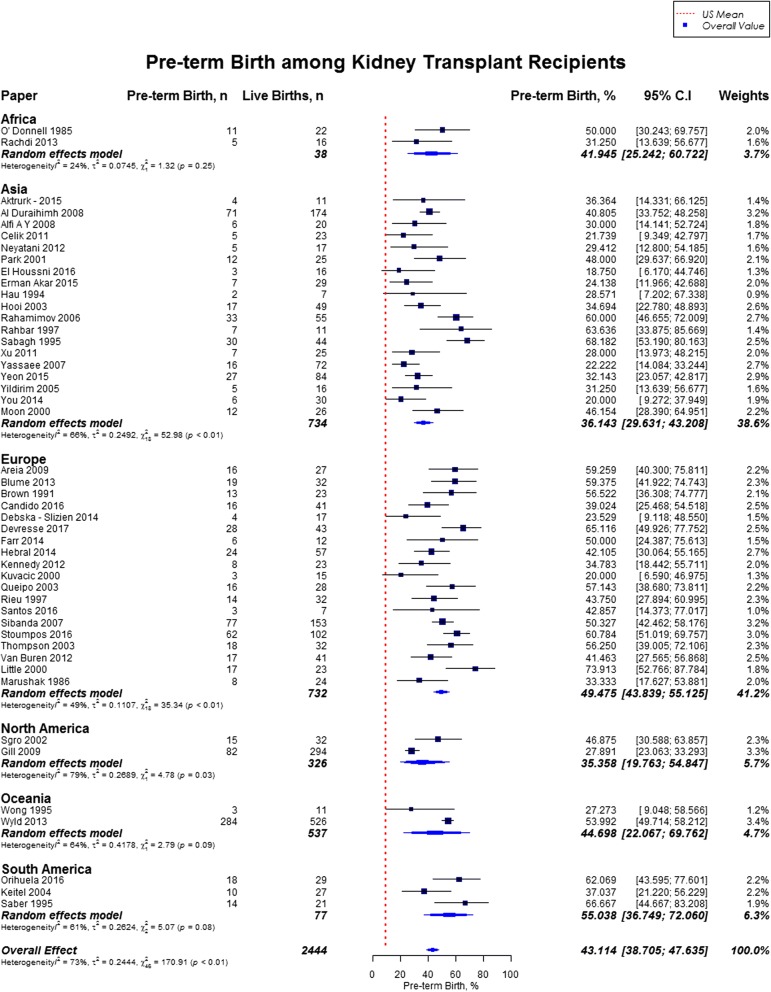

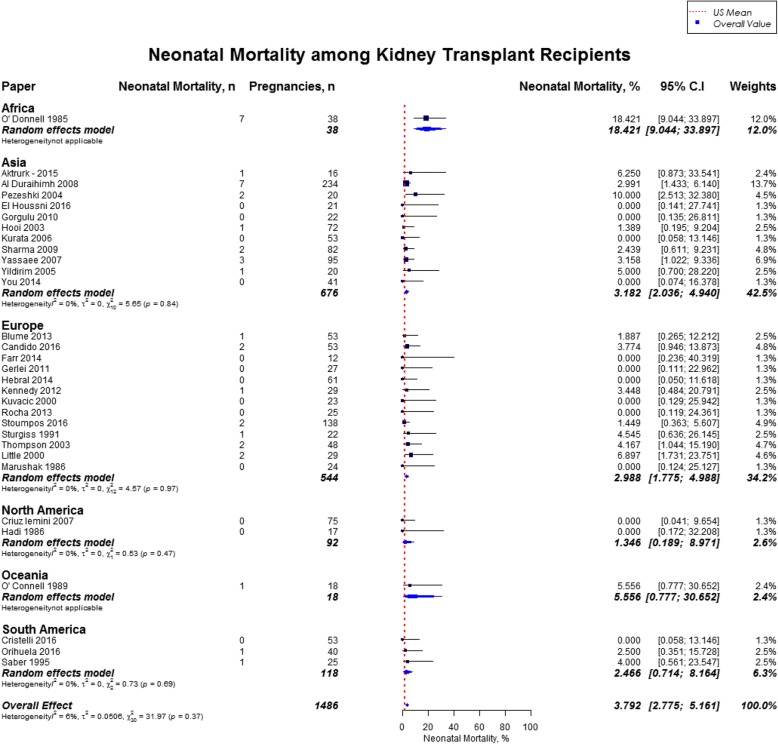

Fetal outcomes

Overall, rate of preterm birth was 43.1% (95% CI, 38.7–47.6) defined by babies born alive before 37 weeks of gestation, and neonatal mortality was 3.8% (95% CI, 2.8–5.2). Rates of preterm birth was highest in South America (55.0%), and lowest in North America (35.4%) (Fig. 11). The mean gestational age for newborns was 34.9 weeks (US mean, 38.7 weeks) and the mean birth weight was 2470 g (US mean, 3389 g). [12, 17] Neonatal mortality was high across all geographical regions as compared to the US mean (3.8% vs. 0.4%), with highest rate in Africa (18.4%; 95% CI, 9.1–33.9) and lowest rate in North America (1.3, 95% CI, 0.2–8.9) (Fig. 12) [18]. The results from the subgroup analyses (2000–2017) for fetal outcomes were consistent with the present findings except for neonatal mortality which was slighly lower in the subgroup analysis (2.9% vs. 3.8%) (Additional file 2).

Fig. 11.

Forest Plot showing outcome of preterm births among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Fig. 12.

Forest Plot showing outcome of neonatal mortality among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

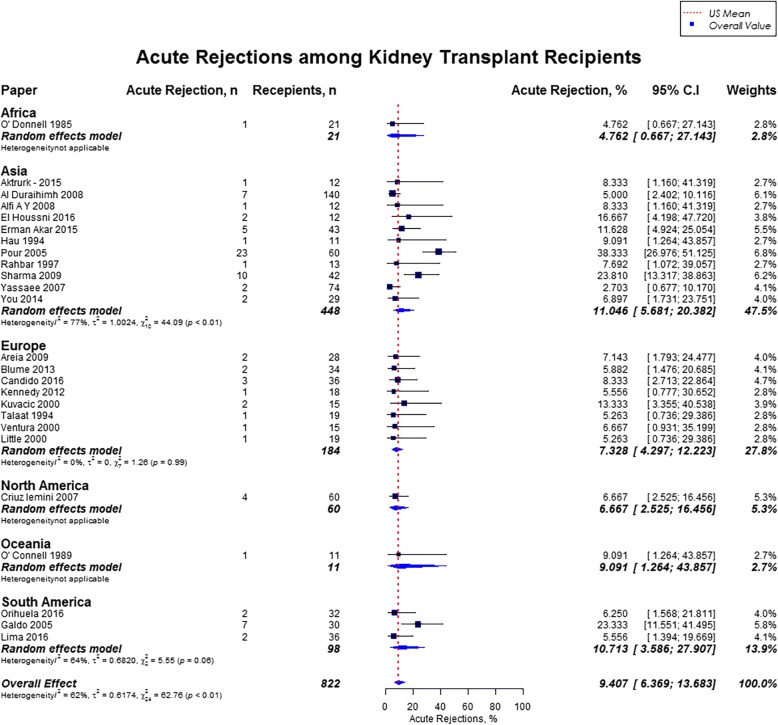

Graft outcomes

The overall acute rejection rate during pregnancy among 822 kidney transplant recipients was 9.4% (95% CI, 6.4–13.7), which was comparable to the US mean of 9.1%. [19] Rates of acute renal allograft rejection were highest in Asia (11.0%), followed by South America (10.7%), Oceania (9.1%), Europe (7.3%), North America (6.7%), and Africa (4.8%) (Fig. 13). With regards to graft failure, there was large variability in the follow up period ranging from 1 year to 14 years. However among 489 recipients in 12 studies where two-year post pregnancy graft loss was reported, there were 32 cases of graft loss (9.2%). The change in preconception creatinine and post-pregnancy creatinine, was statistically significant (1.23 ± 0.16 mg/dl vs. 1.37 ± 0.27 mg/dl, p = 0.007).

Fig. 13.

Forest Plot showing rates of acute rejection among kidney transplant recipients overall, and across different geographical regions

Time of conception

Outcomes were also stratified by interval of < 2 years, 2–3 years, and > 3 years between pregnancy and kidney transplant (Table 2). Adverse pregnancy outcomes of induced abortion rates and neonatal deaths were highest in the 2–3 year interval following kidney transplant as compared to < 2 year interval and > 3 year interval (16% vs. 11% vs. 10, and 9% vs. 3% vs. 4% respectively). Cesarean section rate and live birth rate were also less favorable in this interval of 2–3 years than > 3 year, and < 2 year interval (68% vs. 75% vs. 74, and 73% vs. 65% vs. 42% respectively). Maternal complication of preeclampsia was higher in the 2–3 interval, and > 3 year interval than < 2 year interval (24% vs. 23% vs. 13%). Spontaneous abortion rates were highest in > 3 year interval followed by 2–3 interval, and < 2 interval (16% vs. 14% vs. 10%).

Table 2.

Pregnancy-related outcomes stratified by study mean interval between transplant and pregnancy

| < 2 years | > 2–3 years | > 3 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of papers | 4 | 15 | 44 |

| Number of pregnancies | 149 | 835 | 3182 |

| Mean maternal age (year) | 28.3 | 29.4 | 29.1 |

| Pregnancy Outcomes | |||

| Live birth | 73.8% | 68.3% | 75.4% |

| Induced abortion | 10.7% | 16.1% | 10.2% |

| Spontaneous abortion | 10.3% | 14.0% | 16.3% |

| Still birth | 6.7% | 5.1% | 3.7% |

| Neonatal deaths | 3.4% | 9.3% | 3.7% |

| Cesarean section | 41.8% | 72.7% | 64.5% |

| Maternal Outcomes | |||

| Preeclampsia | 13.2% | 24.3% | 22.8% |

| Pregnancy induced hypertension | 12.1% | 30.8% | 23.0% |

| Gestational diabetes | 0.0% | 8.8% | 7.2% |

| Fetal Outcomes | |||

| Pre-term delivery | 41.9% | 41.6% | 45.4% |

| Mean gestation time (weeks) | 36.1 | 34.5 | 34.9 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 2349.00 | 2533.21 | 2460.79 |

| Graft Outcomes | |||

| Acute rejection | 8.1% | 5.1% | 3.0% |

| Graft loss | 16.7% | 14.6% | 6.3% |

Maternal age for conception

We further stratified the pregnancy, maternal, fetal, and graft outcomes by maternal age categories (Table 3). Lower live birth rate was observed in women with maternal age 29–34 years than those < 29 years (74% vs. 76%). Rates of spontaneous abortion were highest in women < 25 years and > 35 years followed by women with maternal age 25–34 years (20% vs. 18% vs. 11%). Preeclampsia rates were higher in women with maternal age > 35 years (27%) and 29–34 years (26%) followed by < 25 years (17%) and 25–29 years (14%).

Table 3.

Pregnancy-related outcomes stratified by study mean maternal age

| Study mean maternal age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 25 | 25–29 | 30–34 | ≥35 | |

| Number of papers | 3 | 22 | 35 | 1 |

| Number of pregnancies | 103 | 723 | 3474 | 11 |

| Mean maternal age (year) | 23.3 | 27.4 | 30.2 | 36.0 |

| Pregnancy Outcomes | ||||

| Live birth | 75.8% | 75.8% | 73.9% | na |

| Induced abortion | 14.0% | 11.3% | 11.0% | na |

| Spontaneous abortion | 19.8% | 16.0% | 13.3% | 18.2% |

| Still birth | 2.9% | 5.3% | 3.6% | 9.1% |

| Neonatal deaths | na | 5.4% | 3.0% | na |

| Cesarean section | 48.0% | 68.3% | 63.6% | na |

| Maternal Outcomes | ||||

| Preeclampsia | 17.1% | 13.7% | 26.5% | 27.3% |

| Pregnancy induced hypertension | 16.5% | 25.2% | 23.4% | na |

| Gestational diabetes | na | 5.8% | 7.0% | na |

| Fetal Outcomes | ||||

| Pre-term delivery | na | 46.4% | 47.4% | na |

| Mean gestation time (weeks) | 35.5 | 35.5 | 34.6 | na |

| Birth weight (grams) | 2460.0 | 2607.7 | 2456.9 | na |

| Graft Outcomes | ||||

| Acute rejection | 3.8% | 3.3% | 5.8% | na |

| Graft loss | na | 12.1% | 10.4% | 27.3% |

*na not available

Discussion

The results of our meta-analysis show that although majority of pregnancies in women after kidney transplant result in live birth, both maternal and fetal adverse events are common. Rates of preeclampsia, still birth, and cesarean section were significantly higher than in the general population. In the cohort considered for the analysis, a quarter of women had serious pregnancy complications, defined as at least one of preterm delivery, first or second trimester loss, stillbirth, or neonatal death. Additionally, rates of preterm delivery, still births, and neonatal mortality were higher as compared with the US recent national data.

The live birth rates in women after kidney transplant were higher than in the general population (73% vs. 62%) and this trend was consistent throughout the globe [10]. Our study confirms the findings from The National Transplant Pregnancy Registry from the United States that reported a live birth rate of 71–76% [7]. Similarly, meta-analysis done by Deshpande et al. examined pregnancy outcomes of 4706 pregnancies in women with kidney transplant and reported a live birth rate of 73.5% [9]. The higher live birth rate, although appears encouraging, may reflect a reporting bias or a selection bias in which relatively healthy women decided to pursue pregnancy, and subsequently received better medical support by multiple specialties. It is also important to consider that there are inconsistencies in definition of live birth rate used in various studies, for example live birth rate was defined as per 1000 female transplant recipients in some studies, whereas per 1000 pregnancies in transplant recipients in others [7, 20]. Live birth rate in general population (comparison group) is defined by Centers for Disease Control as live births per 1000 population [10]. Additionally, it remains unclear how the multiple gestation pregnancy outcomes were evaluated in these studies. Contrary to the above findings of successful pregnancies, a US health utilization study found a much lower live birth rate of 55% in kidney transplant recipients. They attributed this finding of low live birth rate to underestimation of fetal loss [20]. Davison et al. estimated that just under 40% of conceptions do not go beyond the first trimester, but of those that do, greater than 90% end successfully [21]. Another explanation of high live birth rate in our study could be the exclusion of studies that reported pregnancy outcomes with teratogenic immunosuppressive medications of mycophenolate and sirolimus.

Our study highlights the significantly higher risk of maternal and fetal complications in women with kidney transplants. About a quarter of women developed preeclampsia, and the rates of preeclampsia were almost six fold higher as compared to the general US population (21.5% vs. 3.8%) [16]. Vannevel et al. in an international multicenter retrospective cohort of 52 women who underwent kidney transplantation reported preeclampsia rate of as high as 38%, and chronic hypertension rate of 27% [22]. Hypertension is common in kidney transplant recipients prior to conception with a reported incidence of 52 to 69% [1]. Several factors can contribute to the onset of hypertension after renal transplantation, including but not limited to the type of immunosuppressive therapy (calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids), allograft function, donor type, obesity, alcohol, smoking, and presence of a native kidney (increased production of renin) [23]. Diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia can be difficult in kidney transplant patients due to higher frequency of preexisting hypertension and proteinuria [1, 24].

We found significant differences in rates of gestational diabetes mellitus between various geographical location, for example rates were as high as 8.9% in Europe and as low as 1% in Oceania. Although, the increased rate of gestational diabetes in kidney transplant patients can be well explained by the use of immunosuppressive medications like steroids and calcineurin inhibitors, the striking differences between rates of gestational diabetes according to geographic location also highlights the importance of predisposition to diabetes due to ethnicity. Unfortunately, it was not possible to evaluate the differences in immunosuppressive medications as usually they are individualized to the needs of the patients and transplant center protocol [1, 25].

Rates of stillbirth and neonatal mortality were significantly higher in our study as compared to the general population. While prior studies have not reported higher rates of neonatal mortality and stillbirths in kidney transplant recipients, the current study finding is highly significant. Possible reasons could be prematurity, preeclampsia or presence of other risk factors like hypertension, proteinuria, and serum creatinine of 1.5 mg/dl or higher [26–28]. While it was not possible to determine the exact cause for stillbirth or neonatal mortality, this study finding is critical for counselling of women of child bearing age contemplating pregnancy. In our study, the rate of cesarean section was higher than two folds as compared to general population in United States, and varied from 60 to 77% across different geographical locations. Bramham et al. reported that more than three quarters of the deliveries in kidney transplant recipients were by cesarean section, but only 3% were performed for the indication of renal transplant [3]. Vaginal delivery should not be impaired in kidney transplant patients, as the pelvic allograft does not obstruct the birth canal in most patients [1]. This exceptionally higher rates of cesarean sections in kidney transplant recipients can be attributed to fetal and maternal complications, but warrants further study. There was a high rate of premature births in the transplant population in the present study and close to half of the live births were premature deliveries. Prior studies have showed a preterm birth rate of 40–60% in kidney transplant recipients [9, 29]. Fetal complications, suspected renal compromise or preeclampsia are some of the common indications of early iatrogenic delivery. Interestingly, only quarter of preterm deliveries in renal transplant recipients are induced [3, 7].

The optimal time to conception after renal transplant continues to remain an area of contention. The ideal time of conception in women with renal transplant is between 1 and 2 years after transplantation according to guidelines by American Society of Transplantation, whereas European best practice guidelines recommend delaying pregnancy for a period of 2 years after transplantation [30, 31]. In our study, live birth rate was lowest and neonatal deaths were highest in the 2–3 year interval following kidney transplant. Maternal complication of cesarean section and preeclampsia were higher in the 2–3 and > 3 year interval. In contrast, Deshpande et al. reported both the highest maternal complications of preeclampsia, cesarean section, and gestational diabetes, and least favorable delivery outcome of preterm births in the < 2 year interval as compared to > 2 year interval between kidney transplant and pregnancy [9]. However their analysis was limited by inclusion of only 3 studies in the < 2 interval following kidney transplant. Overall, fetal outcomes in < 2 year interval seem most favorable in our study but merits further investigation due to limitation of the retrospective study design, small numbers, and possible reporting bias associated with data from voluntary registries.

A significant strength of our study is that it involves a large number of pregnant renal transplant recepients from all around the globe, thus providing us with information about pregnancy outcomes for a heterogenous population. Additionally, we have analyzed region specific outcomes and identified outcomes which may require intensive management pertaining to that region. This will help in making future region specific guidelines for follow up and management of pregnancy in kidney transplant recpients. The following limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of our study. We examined pregnancy outcomes over several decades in the present study. While it is expected for the outcomes to change due to improvement in obstetric care in kidney transplant recipients over the course of time, subgroup analysis for studies from 2000 to 2017 showed consistent results. There were inconsistencies in the definition of live birth rate amongst different studies that may have affected the results. Reporting bias may have affected the miscarriage rate. We were unable to account for differences in socioeconomics, and healthcare conditions among the different geographic regions. Due to lack of individual patient data, we were not able to assess pregnancy outcomes in relation to immunosuppression regimens.

Conclusions

This meta analysis of pregnancy outcomes in 6712 pregnancies in 4174 kidney transplant recipients with data spread over different decades from all over the world shows favorable outcomes with live birth rates exceeding that in the recent national population. Majority of patients preserve their graft. However, pregnancy after renal transplant confers significant risk in terms of maternal and fetal adverse events, including increased rates of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, cesarean section rates, and pregnancy induced hypertension. The risk of prematurity and low birth rate are also high. Areas which need to be studied in the future include type of immunosuppression and its correlation with specific pregnancy outcomes; and evaluation of risk factors associated with specific maternal and fetal adverse events. The definitions used in evaluating these outcomes also need to be standardized. The results of this study can help the health care providers with appropriate counseling and individualized management of this high risk population.

Additional files

Reproducible search strategy. (DOCX 149 kb)

Subgroup analysis of various pregnancy outcomes in kidney transplant recipients for studies published from 2000 to 2017. (DOCX 16 kb)

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

SS initiated the study, designed the study and wrote the initial manuscript. RV, Ayank Gupta, RJ and MS contributed to the study design, and study figures, analyzed and interpreted the data, and did the manuscript review. JW contributed to the sudy design, data analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript review. EK contibuted to literature search, and manuscript review. TK contributed in study design and manuscript review. Anu Gupta contributed in manuscript writing and manuscript review. TG contributed to the study design, implementation of the study, study figures, and manuscript review. PV assisted SS with study design and implementation, revision of the manuscript and did the final approval of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grant awarded to SS from University of Cincinnati’s College of Medicine-Health Sciences Library.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- US

United States

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All the authors have no disclosures and competing interests. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Silvi Shah, Phone: 513-558-0688, Email: silvishah2108@gmail.com.

Renganathan Lalgudi Venkatesan, Email: lalgudrn@mail.uc.edu.

Ayank Gupta, Email: gupta2a4@mail.uc.edu.

Maitrik K. Sanghavi, Email: sanghamk@mail.uc.edu

Jeffrey Welge, Email: welgeja@ucmail.uc.edu.

Richard Johansen, Email: johansra@ucmail.uc.edu.

Emily B. Kean, Email: keaney@ucmail.uc.edu

Taranpreet Kaur, Email: kaurtt@ucmail.uc.edu.

Anu Gupta, Email: anuguptadr@gmail.com.

Tiffany J. Grant, Email: joffritm@ucmail.uc.edu

Prasoon Verma, Email: Prasoon.Verma@cchmc.org.

References

- 1.Shah S, Verma P. Overview of pregnancy in renal transplant patients. International journal of nephrology. 2016;2016:4539342. doi: 10.1155/2016/4539342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saha MT, Saha HH, Niskanen LK, Salmela KT, Pasternack AI. Time course of serum prolactin and sex hormones following successful renal transplantation. Nephron. 2002;92(3):735–737. doi: 10.1159/000064079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bramham K, Nelson-Piercy C, Gao H, Pierce M, Bush N, Spark P, Brocklehurst P, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients: a UK national cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2013;8(2):290–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Sifontis NM, Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Lavelanet AF, Moritz MJ, Armenti VT. Pregnancy outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients with exposure to mycophenolate mofetil or sirolimus. Transplantation. 2006;82(12):1698–1702. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000252683.74584.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davison JM, Redman CW. Pregnancy post-transplant: the establishment of a UK registry. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104(10):1106–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb10930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizzoni G, Ehrich JH, Broyer M, Brunner FP, Brynger H, Fassbinder W, Geerlings W, Selwood NH, Tufveson G, Wing AJ. Successful pregnancies in women on renal replacement therapy: report from the EDTA registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1992;7(4):279–287. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a092129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Moritz MJ, Frank AM, Ramirez CB, Maley WR, Doria C, McGrory CH, Armenti VT. Report from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry (NTPR): outcomes of pregnancy after transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2010:65–85. [PubMed]

- 8.Levidiotis V, Chang S, McDonald S. Pregnancy and maternal outcomes among kidney transplant recipients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20(11):2433–2440. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande NA, James NT, Kucirka LM, Boyarsky BJ, Garonzik-Wang JM, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Pregnancy outcomes in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(11):2388–2404. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin J. In: Births in the United States, 2016. NCHS data brief, no 287. Hamilton B, editor. Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin J. Births: Final Data for 2016. National vital statistics reports; vol 67 no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin J: Measuring Gestational Age in Vital Statistics Data: Transitioning to the Obstetric Estimate. National vital statistics reports; vol 64 no 5. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. In. [PubMed]

- 13.Jatlaoui T: Abortion surveillance — United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2017. In., vol. 66; 2017: 1–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.MacDorman M. Fetal and Perinatal Mortality: United States, 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 64 no 8. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics 2015; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stulberg DB, Cain LR, Dahlquist I, Lauderdale DS. Ectopic pregnancy rates and racial disparities in the Medicaid population, 2004-2008. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(6):1671–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2013;f6564:347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donahue SM, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW, Oken E. Trends in birth weight and gestational length among singleton term births in the United States: 1990-2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 1):357–364. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd5f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broder A. Pregnancy outcomes in renal transplants with and without lupus. Clinical and Translational Science. 2013;6(2):128. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanriover B, Jaikaransingh V, MacConmara MP, Parekh JR, Levea SL, Ariyamuthu VK, Zhang S, Gao A, Ayvaci MU, Sandikci B, et al. Acute rejection rates and graft outcomes according to induction regimen among recipients of kidneys from deceased donors treated with tacrolimus and mycophenolate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(9):1650–1661. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13171215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill JS, Zalunardo N, Rose C, Tonelli M. The pregnancy rate and live birth rate in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(7):1541–1549. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davison JM. Renal transplantation and pregnancy. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1987;9(4):374–380. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(87)80140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vannevel V, Claes K, Baud D, Vial Y, Golshayan D, Yoon EW, Hodges R, Le Nepveu A, Kerr PG, Kennedy C, et al. Preeclampsia and long-term renal function in women who underwent kidney transplantation. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(1):57–62. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haas M, Mayer G. Cyclosporin A-associated hypertension--pathomechanisms and clinical consequences. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12(3):395–398. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aivazoglou L, Sass N, Silva HT, Jr, Sato JL, Medina-Pestana JO, De Oliveira LG. Pregnancy after renal transplantation: an evaluation of the graft function. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155(2):129–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKay DB, Josephson MA. Pregnancy after kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2008;3(Suppl 2):S117–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Majak GB, Reisaeter AV, Zucknick M, Lorentzen B, Vangen S, Henriksen T, Michelsen TM. Preeclampsia in kidney transplanted women; outcomes and a simple prognostic risk score system. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little MA, Abraham KA, Kavanagh J, Connolly G, Byrne P, Walshe JJ. Pregnancy in Irish renal transplant recipients in the cyclosporine era. Ir J Med Sci. 2000;169(1):19–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03170477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruz Lemini MC, Ibarguengoitia Ochoa F, Villanueva Gonzalez MA. Perinatal outcome following renal transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;96(2):76–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadi FA, Borg M, Gulyani A, McDonald SP, Jesudason S. Pregnancy outcomes and impact of pregnancy on graft function in women after kidney transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2017;31(10). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.European best practice guidelines for renal transplantation Section IV: Long-term management of the transplant recipient. IV.10. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(Suppl 4):50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKay DB, Josephson MA, Armenti VT, August P, Coscia LA, Davis CL, Davison JM, Easterling T, Friedman JE, Hou S, et al. Reproduction and transplantation: report on the AST consensus conference on reproductive issues and transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(7):1592–1599. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devresse A, Jassogne C, Hubinont C, De Meyer M, Mourad M, Goffin E, Kanaan N. Maternal risks and pregnancy outcomes after kidney transplantation: a single center experience. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:253. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2022.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuksel Y, Tekin S, Yuksel D, Duman I, Sarier M, Yucetin L, Turan E, Celep H, Ugurlu T, Inal MM, et al. Pregnancy and delivery in the sequel of kidney transplantation: single-center study of 8 Years' experience. Transplant Proc. 2017;49(3):546–550. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ajaimy M, Lubetzky M, Jones T, Kamal L, Colovai A, de Boccardo G, Akalin E. Pregnancy in sensitized kidney transplant recipients: a single-center experience. Clin Transpl. 2016;30(7):791–795. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Candido C, Cristelli MP, Fernandes AR, Lima AC, Viana LA, Sato JL, Sass N, Tedesco-Silva H, Medina-Pestana JO. Pregnancy after kidney transplantation: high rates of maternal complications. J Bras Nefrol. 2016;38(4):421–426. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20160067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cristelli M, Candido CD, Fernandes AR, Viana LA, Sato JL, Sass N, De Lima ACA, Tedesco-Silva H, Medina-Pestana JO. Pregnancy among kidney transplanted women: feasibility of pregnancy and effects on the mother and renal graft. Pregnancy Hypertension. 2016;6(3):232. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.08.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Houssni S, Sabri S, Benamar L, Ouzeddoun N, Bayahia R, Rhou H. Pregnancy after renal transplantation: effects on mother, child, and renal graft function. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27(2):227–232. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.178204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima A, Cristelli M, Teixeira C, Pietrobom I, Basso G, Viana L, De Paula M, Cândido C, Tedesco-Silva H, Pestana J. Pregnancy in the renal transplant recipient: pregnancy viability and effects on graft function. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:783–784. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majak GB, Sandven I, Lorentzen B, Vangen S, Reisaeter AV, Henriksen T, Michelsen TM. Pregnancy outcomes following maternal kidney transplantation: a national cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(10):1153–1161. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishra VV, Nanda S, Mistry K, Aggarwal R, Choudhary S, Gandhi K. Pregnancy outcome in renal transplant recipients: Indian scenario. Indian Journal of Transplantation. 2016;10(3):57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijt.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orihuela S, Nin M, San Roman S, Noboa O, Curi L, Silvarino R, Gonzalez-Martinez F. Successful pregnancies in kidney transplant recipients: experience of the National Kidney Transplant Program from Uruguay. Transplant Proc. 2016;48(2):643–645. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piccoli GB, Cabiddu G, Attini R, Gerbino M, Todeschini P, Perrino ML, Manzione AM, Piredda GB, Gnappi E, Caputo F, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after kidney graft in Italy: are the changes over time the result of different therapies or of different policies? A nationwide survey (1978-2013) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(11):1957–1965. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saliem S, Patenaude V, Abenhaim HA. Pregnancy outcomes among renal transplant recipients and patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. J Perinat Med. 2016;44(3):321–327. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos S, Malheiro J, Campos A, Pedroso S, Almeida M, Martins LS, Dias L, Henriques C, Cabrita A. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients: obstetric outcomes and risk of allosensitization. Medicine. 2016;95(10).

- 45.Sarween N, Hughes S, Evison F, Day C, Knox E, Lipkin G. Pregnancy outcomes in renal transplant recipients in England over 15 years. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2016;31:i6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw119.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoumpos S, McNeill SH, Gorrie M, Mark PB, Brennand JE, Geddes CC, Deighan CJ. Obstetric and long-term kidney outcomes in renal transplant recipients: a 40-yr single-center study. Clin Transpl. 2016;30(6):673–681. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshikawa Y, Uchida J, Akazawa C, Suganuma N. Analyses of relationship between obstetric complications and preterm delivery in Japanese recipients received kidney transplant. Transplantation. 2016;100(7):S884–S885. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akturk S, Celebi ZK, Erdogmus S, Kanmaz AG, Yuce T, Sengul S, Keven K. Pregnancy after kidney transplantation: outcomes, tacrolimus doses, and trough levels. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(5):1442–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arab K, Oddy L, Patenaude V, Abenhaim HA. Obstetrical and neonatal outcomes in renal transplant recipients. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(2):162–167. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.909804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erman Akar M, Ozekinci M, Sanhal C, Kececioglu N, Mendilcioglu I, Senol Y, Dirican K, Kocak H, Dinckan A, Suleymanlar G. A retrospective analysis of pregnancy outcomes after kidney transplantation in a single center. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2015;79(1):13–18. doi: 10.1159/000365815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yeon HK, Shim JY, Won HS, Lee PR, Kim A. Risk factors for developing preeclamptic disorder in the pregnancy after kidney transplantation. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:1293.

- 52.Debska-Slizien A, Galgowska J, Chamienia A, Bullo-Piontecka B, Krol E, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Lizakowski S, Renke M, Rutkowski P, Zdrojewski Z, et al. Pregnancy after kidney transplantation: a single-center experience and review of the literature. Transplant Proc. 2014;46(8):2668–2672. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farr A, Bader Y, Husslein PW, Gyori G, Muhlbacher F, Margreiter M. Ultra-high-risk pregnancies in women after renal transplantation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;180:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hebral AL, Cointault O, Connan L, Congy-Jolivet N, Esposito L, Cardeau-Desangles I, Del Bello A, Lavayssiere L, Nogier MB, Ribes D, et al. Pregnancy after kidney transplantation: outcome and anti-human leucocyte antigen alloimmunization risk. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(9):1786–1793. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.You JY, Kim MK, Choi SJ, Oh SY, Kim SJ, Kim JH, Oh HY, Roh CR. Predictive factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes after renal transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2014;28(6):699–706. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blume C, Sensoy A, Gross MM, Guenter HH, Haller H, Manns MP, Schwarz A, Lehner F, Klempnauer J, Pischke S, et al. A comparison of the outcome of pregnancies after liver and kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95(1):222–227. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318277e318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guella A, Mohamed E. Pregnancy in Saudi kidney transplant recipients: a local experience. Transpl Int. 2013;26:287. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pietrzak B, Songin T, Szymusik I, Najman BK, Jabiry-Zieniewicz Z, Cyganek A, Wielgos A, Wielgos M. Pregnancy in female liver or kidney transplant recipients. J Perinat Med. 2013;41.

- 59.Rachdi M, Amine BH, Mohamed B, Mounir C, Radhouane R. Pregnancy after renal transplantation and neonatal outcome. J Perinat Med. 2013;41.

- 60.Ribeiro R, Grecco R, Ribeiro T, Pulcineli R, Francisco V, Pacheco V, Soubhi Z, Zugaib KM. Analysis of obstetrical and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women post renal transplantation. J Perinat Med. 2013;41.

- 61.Rocha A, Cardoso A, Malheiro J, Martins LS, Fonseca I, Braga J, Henriques AC. Pregnancy after kidney transplantation: graft, mother, and newborn complications. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(3):1088–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wyld ML, Clayton PA, Jesudason S, Chadban SJ, Alexander SI. Pregnancy outcomes for kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(12):3173–3182. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kennedy C, Hussein W, Spencer S, Walshe J, Denton M, Conlon PJ, Magee C. Reproductive health in Irish female renal transplant recipients. Ir J Med Sci. 2012;181(1):59–63. doi: 10.1007/s11845-011-0767-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neyatani N, Yamaguchi N, Takagi H, Fujii R, Makinoda S. Clinical study on fertility in women received renal transplantation. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;119:S435–S436. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60923-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Buren MC, Van De Wetering J, Roodnat JI, Berger SP, Tielen M, Weimar W. Pregnancy after kidney transplantation: 'Will mothers see their children grow up?'. Transplantation. 2012;94:141. doi: 10.1097/00007890-201211271-00261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Celik G, Toz H, Ertilav M, Asgar N, Ozkahya M, Basci A, Hoscoskun C. Biochemical parameters, renal function, and outcome of pregnancy in kidney transplant recipient. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(7):2579–2583. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gerlei Z, Wettstein D, Rigo J, Asztalos L, Langer RM. Childbirth after organ transplantation in Hungary. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(4):1223–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lopez V, Martinez D, Vinolo C, Cabello M, Sola E, Gutierrez C, Burgos D, Gonzalez-Molina M, Hernandez D. Pregnancy in kidney transplant recipients: effects on mother and newborn. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(6):2177–2178. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu LG, Han S, Liu Y, Wang HW, Yang YR, Qiu F, Peng WL, Tang LG. Timing, conditions, and complications of post-operative conception and pregnancy in female renal transplant recipients. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61(2):421–426. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gorgulu N, Yelken B, Caliskan Y, Turkmen A, Sever MS. Does pregnancy increase graft loss in female renal allograft recipients? Clin Exp Nephrol. 2010;14(3):244–247. doi: 10.1007/s10157-009-0263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Areia A, Galvao A, Pais MS, Freitas L, Moura P. Outcome of pregnancy in renal allograft recipients. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(3):273–277. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0711-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rizvi SAH, Kumari K, Naqvi R, Aziz T, Ahmed E, Naqvi SAA. An update on pregnancy outcome in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:518–519. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sharma U, Minocha S. Pregnancy after renal transplant - Oman perspective. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107:S269. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(09)60990-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Al Duraihimh H, Ghamdi G, Moussa D, Shaheen F, Mohsen N, Sharma U, Stephan A, Alfie A, Alamin M, Haberal M, et al. Outcome of 234 pregnancies in 140 renal transplant recipients from five middle eastern countries. Transplantation. 2008;85(6):840–843. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318166ac45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alfi AY, Al-essawy MA, Al-lakany M, Somro A, Khan F, Ahmed S. Successful pregnancies post renal transplantation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2008;19(5):746–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oliveira LG, Sass N, Sato JL, Ozaki KS, Medina Pestana JO. Pregnancy after renal transplantation--a five-yr single-center experience. Clin Transpl. 2007;21(3):301–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sibanda N, Briggs JD, Davison JM, Johnson RJ, Rudge CJ. Pregnancy after organ transplantation: a report from the UK transplant pregnancy registry. Transplantation. 2007;83(10):1301–1307. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000263357.44975.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yassaee F, Moshiri F. Pregnancy outcome in kidney transplant patients. Urol J. 2007;4(1):14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kurata A, Matsuda Y, Tanabe K, Toma H, Ohta H. Risk factors of preterm delivery at less than 35 weeks in patients with renal transplant. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;128(1):64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rahamimov R, Ben-Haroush A, Wittenberg C, Mor E, Lustig S, Gafter U, Hod M, Bar J. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients: long-term effect on patient and graft survival. A single-center experience. Transplantation. 2006;81(5):660–664. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000166912.60006.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Galdo T, Gonzalez F, Espinoza M, Quintero N, Espinoza O, Herrera S, Reynolds E, Roessler E. Impact of pregnancy on the function of transplanted kidneys. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(3):1577–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garcia-Donaire JA, Acevedo M, Gutierrez MJ, Manzanera MJ, Oliva E, Gutierrez E, Andres A, Morales JM. Tacrolimus as basic immunosuppression in pregnancy after renal transplantation. A single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(9):3754–3755. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.09.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ghanem ME, El-Baghdadi LA, Badawy AM, Bakr MA, Sobhe MA, Ghoneim MA. Pregnancy outcome after renal allograft transplantation: 15 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121(2):178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pour-Reza-Gholi F, Nafar M, Farrokhi F, Entezari A, Taha N, Firouzan A, Einollahi B. Pregnancy in kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(7):3090–3092. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yildirim Y, Uslu A. Pregnancy in patients with previous successful renal transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;90(3):198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Keitel E, Bruno RM, Duarte M, Santos AF, Bittar AE, Bianco PD, Goldani JC, Garcia VD. Pregnancy outcome after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(4):870–871. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pezeshki M, Taherian AA, Gharavy M, Ledger WL. Menstrual characteristics and pregnancy in women after renal transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;85(2):119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hooi LS, Rozina G, Shaariah MY, Teo SM, Tan CH, Bavanandan S, Rosnawati Y. Pregnancy in patients with renal transplants in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2003;58(1):27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Queipo-Zaragoza JA, Vera-Donoso CD, Soldevila A, Sanchez-Plumed J, Broseta-Rico E, Jimenez-Cruz JF. Impact of pregnancy on kidney transplant. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(2):866–867. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(02)04033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thompson BC, Kingdon EJ, Tuck SM, Fernando ON, Sweny P. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients: the Royal Free Hospital experience. Qjm. 2003;96(11):837–844. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sgro MD, Barozzino T, Mirghani HM, Sermer M, Moscato L, Akoury H, Koren G, Chitayat DA. Pregnancy outcome post renal transplantation. Teratology. 2002;65(1):5–9. doi: 10.1002/tera.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tan PK, Tan AS, Tan HK, Vathsala A, Tay SK. Pregnancy after renal transplantation: experience in Singapore General Hospital. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2002;31(3):285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Park Y, Cho J, Kim Y, Lee C, Choi H, Kim T, Kim H, Han S, Kwon H. Pregnancy outcome in renal transplant recipients: the experience of a single center in Korea. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(6):S180. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(01)80391-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kuvacic I, Sprem M, Skrablin S, Kalafatic D, Bubic-Filipi L, Milici D. Pregnancy outcome in renal transplant recipients. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000;70(3):313–317. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(00)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moon JI, Park SG, Cheon KO, Kim SI, Kim YS, Park YW, Park K. Pregnancy in renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2000;32(7):1869–1870. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(00)01469-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ventura A, Martins L, Dias L, Henriques AC, Sarmento AM, Braga J, Pereira MC, Guimaraes S. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2000;32(8):2611–2612. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(00)01806-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Arsan A, Guest G, Gagnadoux MF, Broyer M. Pregnancy in renal transplantation: a pediatric unit report. Transplant Proc. 1997;29(5):2479. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(97)00457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rahbar K, Forghani F. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients: an Iranian experience with a report of triplet pregnancy. Transplant Proc. 1997;29(7):2775. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(97)00673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rieu P, Neyrat N, Hiesse C, Charpentier B. Thirty-three pregnancies in a population of 1725 renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 1997;29(5):2459–2460. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(97)00449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.al Hassani MK, Sharma U, Mohsin N, Aghanashinikar P, al Maiman Y, Kumar MN, Daar AS. Pregnancy in renal transplantation recipients: outcome and complications in 44 pregnancies. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(5):2585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sabagh TO, Eltorkey MM, El Awad MA, Abed S. Outcome of pregnancy in venal transplant recipients taking cyclosporin a. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;15(4):226–229. doi: 10.3109/01443619509020685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Saber LT, Duarte G, Costa JA, Cologna AJ, Garcia TM, Ferraz AS. Pregnancy and kidney transplantation: experience in a developing country. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25(3):465–470. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wong KM, Bailey RR, Lynn KL, Robson RA, Abbott GD. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients: the Christchurch experience. N Z Med J. 1995;108(1000):190–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hadi HA, Stafford CR, Williamson JR, Fadel HE, Devoe LD. Pregnancy outcome in renal transplant recipients: experience at the medical College of Georgia and review of the literature. South Med J. 1986;79(8):959–964. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198608000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Talaat KM, Tyden G, Bjorkman U, Groth CG. Thirty successful pregnancies in organ transplant recipients: a single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 1994;26(3):1773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pahl MV, Vaziri ND, Kaufman DJ, Martin DC. Childbirth after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1993;25(4):2727–2731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Muirhead N, Sabharwal AR, Rieder MJ, Lazarovits AI, Hollomby DJ. The outcome of pregnancy following renal transplantation--the experience of a single center. Transplantation. 1992;54(3):429–432. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brown JH, Maxwell AP, McGeown MG. Outcome of pregnancy following renal transplantation. Ir J Med Sci. 1991;160(8):255–256. doi: 10.1007/BF02973400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sturgiss SN, Davison JM. Perinatal outcome in renal allograft recipients: prognostic significance of hypertension and renal function before and during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(4):573–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.O'Connell PJ, Caterson RJ, Stewart JH, Mahony JF. Problems associated with pregnancy in renal allograft recipients. Int J Artif Organs. 1989;12(3):147–152. doi: 10.1177/039139888901200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ha J, Kim SJ, Kim ST. Pregnancy following renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1994;26(4):2117–2118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Marushak A, Weber T, Bock J, Birkeland SA, Hansen HE, Klebe J, Kristoffersen K, Rasmussen K, Olgaard K. Pregnancy following kidney transplantation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1986;65(6):557–559. doi: 10.3109/00016348609158386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.O'Donnell D, Sevitz H, Seggie JL. Pregnancy after renal transplantation. Aust NZ J Med. 1985;15(3):320–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1985.tb04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Waltzer WC, Coulam CB, Zincke H, Sterioff S, Frohnert PP. Pregnancy in renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1980;12(1):221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Reproducible search strategy. (DOCX 149 kb)

Subgroup analysis of various pregnancy outcomes in kidney transplant recipients for studies published from 2000 to 2017. (DOCX 16 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.