Abstract

Repurposing is a drug development strategy that seeks to use existing medications for new indications. In oncology, there is an increased level of activity looking at the use of non-cancer drugs as possible cancer treatments. The Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) project has used a literature-based approach to identify licensed non-cancer drugs with published evidence of anticancer activity. Data from 268 drugs have been included in a database (ReDO_DB) developed by the ReDO project. Summary results are outlined and an assessment of clinical trial activity also described. The database has been made available as an online open-access resource (http://www.redo-project.org/db/).

Keywords: drug repurposing, repositioning, ReDO project, cancer drugs, online database

Introduction

Drug repurposing, also known as repositioning, is a strategy that seeks new medical treatments from among existing licensed medications rather than from the development of new molecules (de novo drug development) [1]. Repurposing is by no means a new idea in medicine, indeed, many venerable and well-established drugs, for example, the beta-blocker propranolol, have been extensively repurposed many times in the past. However, as an explicit development strategy, repurposing is being increasingly pursued in a number of different disease areas [2–4]. Indeed, data from PubMed show that the number of publications related to drug repurposing or repositioning has increased exponentially since 2004 [5].

The Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) project is an on-going collaborative project that has focused exclusively on the potential use of licensed non-cancer medications as sources of new cancer therapeutics [6]. While it is a common practice for new cancer medicines to be licensed for additional cancer indications after an initial license has been granted, a process that has been termed ‘soft repurposing’, the licensing of non-cancer medications as new treatments is relatively uncommon, hence this process has been termed ‘hard repurposing’ [7]. Indeed, there are very few examples in standard clinical practice of non-cancer drugs being moved into oncology, with thalidomide (multiple myeloma) and all-trans retinoic acid (acute promyelocytic leukaemia) being the best-known examples. In this sense, the ReDO project has focused exclusively on hard drug repurposing in oncology.

In contrast to de novo drugs, licensed medications may offer a number of advantages in terms of development [8]:

Availability of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and posology data

Knowledge of safety and toxicity, including rare adverse events

Clinical experience derived from the original indications

Widespread availability—particularly for drugs included in the WHO Essentials Medicines list (EML)

Low cost—particularly for generic medications with multiple manufacturers

Understanding of mechanisms of action and/or molecular targets

However, while these advantages may shorten the development period in comparison to unlicensed medications, particularly with respect to early phase toxicity trials, proving efficacy in any new indications remains a challenge. Despite the advantages that repurposed drugs may offer in terms of toxicity and cost, the single most important criterion by which treatments should be judged is efficacy. Of course, this also means that the medical community should judge the relative merits of repurposed versus new drugs without bias [9].

While much of the burgeoning interest in oncological repurposing is related to a few very high profile candidates, such as aspirin or metformin, there is indeed a wide range of non-cancer drugs which have some level of evidence in support of relevant anticancer activity [10, 11]. This paper introduces ReDO_DB—a database of non-cancer drugs with evidence of anticancer activity that has been developed as part of the ReDO project. In addition to outlining the methodology and a selection of results from the database, it also gives details of the online open access publication of the database so that the data can be freely used by clinicians and researchers interested in developing specific repurposing projects.

Methodology

The ReDO project has adopted a literature-based methodology to identify non-cancer drugs with anticancer potential. The academic literature was actively scanned and potential repurposing candidates identified.

Selection criteria

Potential candidates must match the following criteria:

-

The drug is currently licensed for non-cancer indications in at least one country in the world. Not included are:

Existing cancer drugs, including cytotoxics, targeted agents or immunotherapeutics, (e.g. docetaxel, cyclophosphamide etc)

Drugs withdrawn globally (e.g. phenformin)

Experimental medicines or previously shelved compounds (e.g. semagacestat, licofelone etc)

Nutraceuticals (e.g. curcumin, resveratrol etc)

The drug is the subject of one or more peer-reviewed publications showing a specific anticancer effect in one or more malignancies.

The evidence for anticancer effects could come from in vitro, in vivo or human research (as assessed by performing a PubMed search). In silico studies supported with in vitro or in vivo data were also included.

Drugs are included in the database if they fulfil the criteria above. In some cases, there may be indirect evidence to suggest that a drug may have anticancer activity because it has effects on an oncologically relevant pathway. However, if there is no explicit evidence of an effect—in other words, the evidence is purely mechanistic, then the drug is not included in the database.

Data collected

For each drug added to the database, we recorded its name (international non-proprietary name), synonyms (if relevant) and main approved indications. Each drug was also checked to see if it is available as a generic and whether it is included in the WHO List of Essential Medicines [12]. Multiple data sources were checked to assess whether a drug is available as a generic or is off-patent, although in some cases it was not possible to ascertain the current position with respect to patent protection. We also collected information on the type of research showing the anticancer activity of the drug: in vitro, in vivo and in humans.

Human data could include individual case reports, case series, epidemiological studies and clinical trials. Case reports were assessed using the following PubMed search terms: (‘Case Reports’ [Publication Type]) AND cancer AND <drug name>. Observational studies were assessed using the following PubMed search terms: (‘Observational Study’ [Publication Type]) AND Cancer AND <drug name>. Clinical data included published trial reports, of any phase, and existing clinical trial activity (as assessed by checking ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP and OpenTrials registries). ReDO_DB was cross-referenced with DrugBank [13, 14] for additional analysis. Data were extracted on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System codes for each drug [15]. Additionally, DrugBank was used to extract data on the validated molecular targets for each drug. Note that these targets are not cancer-specific and as with the ReDO_DB data presented here, the data on molecular targets is a snapshot based on release 5.1.1 of DrugBank (release date 03 July 2018).

Finally, a search was performed to assess clinical trial activity by the drug. Three international clinical trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP and OpenTrials) were searched for each of the drugs on 16 August 2018. Only active late-stage oncology trials were included—that is trials flagged as Phase 2/3, Phase 3 or Phase 3/4. Each trial was manually assessed to remove trials in which the drugs were being used for their original indication, for example, trials in which licensed antiemetics were being assessed in new cancer or in combination treatments with other antiemetics. For each trial, the following information were collected: drug tested, countries (and continent), sponsor and cancer type.

Results

Drugs in the ReDO database

We found a total of 268 drugs that met our selection criteria. In order to maximise the utility of the database, an open access version is made available online via the website of the ReDO project (www.redo-project.org/db). The online version will be periodically updated so that as new drugs are added to the database, or new data become available for existing drugs on the database, the information can be made available to the oncology community. Additions or amendments may also be proposed via an online contact form, enabling other members of the oncology community to contribute to the development of the database. The online database has also been structured in a format to facilitate easy data-mining, spidering or simple cut and paste to maximise accessibility.

The following results summarise the data in the ReDO_DB as of 16 August 2018 when 268 drugs were included. Summary statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary statistics from ReDO_DB as of 15 August 18.

| Drugs … | Yes | % | No | % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are included in WHO List of Essential Medicines? | 87 | 32 | 181 | 68 | 268 |

| Are off-patent? § | 226 | 84 | 35 | 13 | 268 |

| Are supported by in vitro evidence? | 264 | 99 | 4 | 1 | 268 |

| Are supported by in vivo evidence? | 247 | 92 | 21 | 8 | 268 |

| Are supported by case reports? | 86 | 32 | 182 | 68 | 268 |

| Are supported by observational studies? | 36 | 13 | 232 | 87 | 268 |

| Have been/Are being tested in clinical trials? | 178 | 66 | 90 | 34 | 268 |

| Have trial report(s) published? | 113 | 63 | 65 | 37 | 178 |

| Are supported by human data? * | 194 | 72 | 74 | 28 | 268 |

| Are WHO + Off-patent + Human data?* | 67 | 25 | 201 | 75 | 268 |

At least one case report, observational study or clinical trial.

It was not possible to ascertain the patent position for 3% of drugs.

It should be noted that 25% of drugs meet multiple favourable criteria in that they are on the WHO List of Essential Medicines, are off-patent and have some form of human evidence of anticancer effects.

The complete list of drugs is included in the supplementary data.

Repurposing candidates come from a wide range of areas of medicine. Using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, we can assess the sources of ReDO_DB drugs, as shown in Table 2. Note that some drugs are included in multiple ATC categories, and therefore the total is greater than the number of drugs in the ReDO dataset.

Table 2. Number of drugs by top-level ATC category.

| ATC Level 1 | Drugs |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular System | 56 |

| Nervous System | 49 |

| Alimentary Tract and Metabolism | 39 |

| Musculo-Skeletal System | 31 |

| Antiinfectives for Systemic Use | 26 |

| Dermatologicals | 23 |

| Genito Urinary System and Sex Hormones | 23 |

| Sensory Organs | 22 |

| Antiparasitic Products, Insecticides and Repellents | 20 |

| Blood and Blood-Forming Organs | 16 |

| Antineoplastic and Immunomodulating Agents | 12 |

| Respiratory System | 11 |

| Systemic Hormonal Preparations, Excl. Sex Hormones and Insulins | 4 |

| Various | 4 |

Data on molecular targets are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Molecular targets included in ReDO drugs.

| Item | |

|---|---|

| ReDO drugs included in DrugBank* | 263 |

| ReDO drugs with targets in DrugBank | 252 |

| Total targets identified in all ReDO drugs | 1201 |

| Number of unique targets in ReDO drugs | 660 |

| Average targets per drug | 4.77 |

Five drugs approved for use outside of the USA and the EU are not currently included in DrugBank.

Late stage oncology trials

In all 190 relevant late-stage trials were identified. Data from this analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. ReDO drugs included in late-phase clinical trials.

| Item | |

|---|---|

| Number of relevant late-stage trials | 190 |

| Number of unique drugs | 72 |

| Number of drugs with 5 or more trials | 11 |

| Number of drugs with 10 or more trials | 6 |

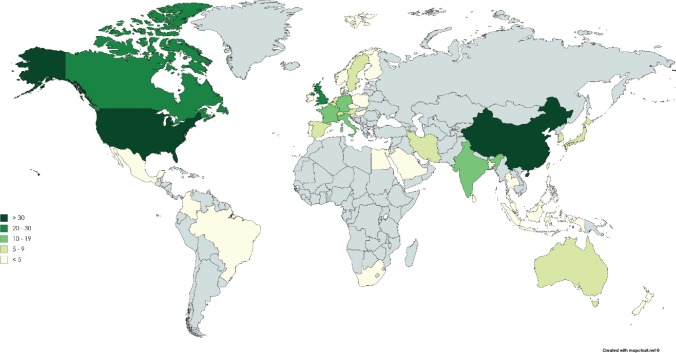

The characteristics of the 190 trials are summarised in Table 5. Figure 1 shows a map of the countries where the trials have been or are being conducted. A small number of drugs are currently the subject of intense clinical trial activity (i.e. 10 or more active late-stage trials) and should be considered to be well advanced in terms of a ‘repurposing drugs pipeline’ in oncology. In terms of clinical trial sponsorship, the data show that the very few trials have a commercial sponsor—less than 4% of trials in this dataset.

Table 5. Characteristics of the 190 trials registered with one of the 72 drugs of the ReDO_DB tested in clinical trials.

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug with more than 10 trials | |||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 27 | 14 | |

| Celecoxib | 12 | 6 | |

| Cholecalciferol | 12 | 6 | |

| Metformin | 17 | 9 | |

| Olanzapine | 10 | 5 | |

| Zoledronic Acid | 20 | 11 | |

| Cancer Type | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 53 | 28 | |

| Breast | 38 | 20 | |

| Hematologic | 23 | 12 | |

| Lung | 14 | 7 | |

| Gynaecologic | 11 | 6 | |

| Brain and CNS | 10 | 5 | |

| Other | 24 | 13 | |

| Paediatric | 12 | 6 | |

| Not specified | 23 | 12 | |

| Trial Location | |||

| Europe | 68 | 36 | |

| Asia | 61 | 32 | |

| North America | 48 | 25 | |

| Middle East | 11 | 6 | |

| Oceania | 7 | 4 | |

| South & Central America | 6 | 3 | |

| Africa | 5 | 3 | |

| Sponsor | |||

| University and/or hospital | 127 | 67 | |

| Research Institute, organisation, foundation or network | 53 | 28 | |

| Small- and medium-sized pharmaceutical companies | 6 | 3 | |

| Government | 3 | 2 | |

| Large pharmaceutical companies | 1 | 1 | |

Figure 1. World map showing the number of late-stage trials of the drugs in the ReDO_DB per country.

Discussion

Data from ReDO_DB show that there are in fact a large number of non-cancer drugs with published evidence of anticancer effects. The majority (73%) have some evidence of anticancer effects from case reports, observational studies or clinical trials. Furthermore, the majority (84%) are off-patent, and 32% are included in the WHO EML. The number of drugs which have human data, are off-patent and included in the WHO EML is 67, representing 25% of the total database. This represents a promising pipeline of potential new treatments in oncology. It is indeed encouraging that there are currently just under 200 late-stage clinical trials investigating the use of these drugs in oncology. However, given the high unmet needs in paediatric oncology, it is not so encouraging to note that only 6% of these trials are in childhood cancers.

In terms of molecular drug targets, it is likely that the number of targets reported in Table 3 is an underestimate based on analysis by Mestres et al which showed that for a large panel of drugs, the average number of target proteins per drug is 6.3 if additional data sources to DrugBank are accessed [16].

The ReDO_DB has both strengths and limitations. One strength is that the database has been built prospectively over the last 5 years, allowing us to manually curate and validate each drug. We have also benefited from the help of a large network of individuals interested in drug repurposing in oncology. However, we acknowledge that at any given time, the database is incomplete in that new data are published and new candidates emerge. Currently, new entries to the database are added regularly and it is hoped that with the database becoming publicly available, a crowdsourcing effect may help to increase the level of completeness of the database.

ReDO_DB does not include drugs that have solely in silico evidence of a possible role in oncology. While our criteria depend on biological data (in vitro or in vivo) for the inclusion of a candidate drug in the database, we acknowledge the value of in silico work as it is often the first method to suggest a brand new use for an existing drug [17]. One limitation of the database is that it does not include existing cancer drugs which represent a large source of repurposing opportunities. However, virtually all cancer drugs are possible candidates for repurposing in other cancer types and listing them in the ReDO_DB would not be of any added value. We also have not included approved vaccines in the database but we are considering doing so, building on the case of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin [18] and looking at recent evidence in support of the repurposing of influenza [19] or cholera vaccine [20].

The inclusion of a number of drugs was problematic in that they are already licensed for use in oncology for symptomatic relief (e.g. aprepitant to control chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting) or cancer-related events (e.g. zoledronate or ibandronate for reduction of bone-related events in advanced malignancies). In the former case, drugs are included if there is data to suggest that there is specific anticancer activity independent of the existing licensed indication. With the cases of zoledronate and ibandronate, the issue is complicated in that there is some existing ‘off-label’ use of the drugs for specific anticancer effects. However, as this use is currently off-label, the drugs have been included in the database.

While the inclusion of new drugs in the database is fairly straightforward and is based on the criteria outlined previously, the removal of repurposing candidates is more complex. Failure of a repurposing candidate in a clinical trial is insufficient grounds for removal as the drug may still be active in a different cancer, treatment setting, drug combination or dose. Where a drug has been included based solely on published preclinical work that is later shown to be fraudulent, then removal would be warranted if there is no other supporting evidence. However, the clearest case for removal is when a repurposed drug becomes licensed as a new cancer treatment—in that case, the drug moves into the ‘soft repurposing’ category for further development in other cancer indications and will be removed from the ReDO_DB.

With such a broad range of drugs and so many validated molecular targets, discussion of general mechanisms of action and research priorities is not possible. The vast majority of these drugs do not induce cancer cell cytotoxicity but instead act systemically on the host, alter the immune response or else affect aspects of the tumour microenvironment. These effects may provide therapeutic benefit to cancer patients when used in combination with existing treatments.

The main challenge will be to test these hypotheses to ultimately find cancer indications, if any, for each candidate. For drugs that are already well-studied (e.g. disulfiram or nelfinavir), a meticulous analysis of the data available is needed to identify the most relevant clinical trials to be conducted. For less well-studied drugs (e.g. fasudil or trimetazidine), more research may first be needed to explore and guide the possible future of those drugs. Another possible source of indications for some candidates may be in precision oncology efforts [7].

A number of online cancer-related drug repurposing databases already exist, including DRUGSURV [21], DeSigN [22] and IMPACT [23]. However, these databases are primarily designed to facilitate the discovery of new repurposing candidates using different data sources and algorithmic techniques. In contrast, ReDO_DB presents a curated list of repurposing candidates and a summary of the types of data sources supporting the inclusion of the drug in the database. Outside of oncology, the PDE3 (Prescribable Drugs with Efficacy in Experimental Epilepsies) [2] is an example of a database similar in scope and intention to ReDO_DB.

There is clearly a scope to increase the value of the database in the future by the inclusion of additional data fields. One possibility is to include an indication of the strength of evidence for each of the drugs in addition to showing the range (in vitro, in vivo etc) of evidentiary sources. Other enhancements may also be proposed by users of the database in the future.

Conclusion

The results outlined in this paper are generally positive in showing both a growth of interest in drug repurposing, a wide range of candidates for repurposing in oncology and 190 late-stage clinical trials. However, it is also true that there are numerous obstacles in the path to successful repurposing. Because many of the repurposing candidates are generic drugs, (84% in the ReDO dataset), commercial funding of clinical trials is normally not an option. Indeed, the data in Table 5 show that only 7 of 190 trials were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.

There are significant costs associated with carrying out large Phase III efficacy trials—repurposing trials are therefore at a disadvantage in that they must rely on state or philanthropic sources of funding. Indeed, there is even some evidence to suggest that for an institution there is a financial benefit from running a commercial trial (i.e. per patient net income) compared to a non-commercial trial (i.e. per patient net cost) [24, 25]. In some cases, there may be commercial support for repurposing trials if a commercial sponsor is looking to increase efficacy or expand an indication for an on-patent drug by combining with a repurposing candidate. There may also be cases where insurers or other payers may wish to fund studies that have the potential to reduce cancer recurrence rates or other interventions designed to reduce their costs. Finally, the costs of studies using repurposed drugs may fall if suitable biomarkers are used to stratify patients for enrolment who are most likely to benefit, thereby reducing patient numbers required to show an effect.

Here again repurposing faces a financial obstacle in that there are costs associated with licensing a drug for a new indication (technically, a label extension). It is also the case that there are regulatory restrictions on who can apply for a label extension—therefore, it is important to make the case for a ‘public benefit label extension’ process so that we can move clinically-proven repurposing from ‘off-label’ to ‘on-label’ treatments [26]. In time, we hope that we will see the ReDO_DB shrink as repurposed drugs are licensed for new cancers indications, at which point they will be removed from the database.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. All the authors are associated with not for profit organisations that aim to repurpose drugs for oncology treatments. VPS is also a scientific advisory board member of Berg Health and Mitra Biotech.

Acknowledgments

This work would not be as extensive without the contribution of multiple collaborators, researchers and clinicians who share our interest in drug repurposing. We are grateful to Richard Kast, Andrew Wilcock, Michael Jameson, Lars Søraas, Nicolas André, Albrecht Reichle, Richard Sullivan, Bjørn Tore Gjertsen, Peter Nygren, our colleagues at the Anticancer Fund and the team at ecancermedicalscience … and many others who have shared their findings with us to make this list as complete as possible.

Supplementary: ReDO drugs list— 16 August 2018

| Drug | Synonym | Main Indications | WHO | Off-Patent | Vitro | Vivo | Cases | Obs. Studies | Trials | Trial Report | Human data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | Paracetamol | Analgesia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Acetazolamide | Glaucoma, diuretic, epilepsy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | Aspirin | Analgesia, swelling, prophylaxis of venous embolism and further heart attacks or strokes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Agomelatine | Insomnia | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Albendazole | Parasitic infection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Alendronic Acid | Alendronate | Osteoporosis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Aliskiren | Essential hypertension | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Allopurinol | Gout | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Alpha-Lipoic Acid | Thioctic Acid, Lipoic Acid | Diabetic neuropathy (Germany) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Amantadine | Parkinson’s Disease, Influenza A | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Amiloride | In congestive heart failure or hypertension treated with thiazides, to conserve potassium | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Amiodarone | Ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | no | |

| Amitriptyline | Depression | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Amlodipine | Hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Amodiaquine | Malaria | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Anagrelide | Essential thrombocythemia | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Anakinra | RA, NOMID, CAPS | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Aprepitant | Nausea, vomiting | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Aprotinin | Perioperative blood loss | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Aripiprazole | Bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, authistic disorder | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Artesunate | Malaria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ascorbic acid | Ascorbate, Vitamin C | Scurvy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Atenolol | Hypertension, angina pectoris | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Atorvastatin | Coronary heart disease, acute coronary syndrome | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Atovaquone | Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, toxoplasmose | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Atrial Natriuretic Peptide | Carperitide | Heart failure | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Auranofin | RA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Azithromycin | Bacterial infection, CAP, PID | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Bazedoxifene | Osteoporosis | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Bedaquiline | Tuberculosis | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Bemiparin | Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Benserazide | Parkinson’s Disease | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Benztropine | Benzatropine | Parkinson’s Disease | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Bepridil | Hypertension and chronic stable angina | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Bezafibrate | Hyperlipidaemia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Biperiden | Parkinson’s Disease | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Bosentan | PAH | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Bromocriptine | Parkinson’s Disease, prevention of lactation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Cabergoline | Hyperprolactinaemia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Caffeine | Newborn apnoea | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Calcitriol | Vitamin D3 | Vitamin D deficiency | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Canagliflozin | Diabetes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Candesartan | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Captopril | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Carbimazole | Hyperthyroidism | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Carglumic Acid | Hyperammonaemia in N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Carvedilol | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Celecoxib | OA, RA, JRA, AS, acute pain, primary dysmenorrhoea | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Cephalexin | Bacterial infections | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Chloramphenicol | Superficial eye infections, typhoid fever | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Chloroquine | Malaria, Extraintestinal Amoebiasis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Chlorpromazine | Psychotic disorders, nausea and vomiting, anxiety, hiccups | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Cholecalciferol | Colecalciferol, Vitamin D3 | Vitamin D deficiency | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Ciclopirox | Athlete’s foot, ringworm | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Cidofovir | CMV-retinitis in AIDS | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Cilnidipine | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Cimetidine | Duodenal/gastric ulcers, GERD, pathological hypersecretory conditions | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Antibiotic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Citalopram | Depression | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Clarithromycin | Bacterial infections | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Clodronic acid | Clodronate | Osteolytic lesions, hypercalcaemia and bone pain associated with skeletal metastases in patients with breast cancer or multiple myeloma | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Clofoctol | Bacterial infections | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Clomifene | Ovulatory dysfunction | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Clomipramine | Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Clopidogrel | Stroke, post-myocardial infarction | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Clotrimazole | Fungal infections | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Colchicine | Gout | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Dalteparin | DVT (prophylaxis), unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Danazol | Endometriosis, fibrocystic breast disease, hereditary angioedema | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Dapsone | Dermatitis herpetiformis, leprosy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Deferasirox | Acute iron intoxication, chronic iron overload | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Deferiprone | Iron overload in thalassaemia major | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Deferoxamine | Desferrioxamine | Acute iron intoxication, chronic iron overload | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Desmopressin | Diabetes Insipidus, bedwetting, haemophilia A, von Willebrand’s disease | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Diclofenac | OA, RA, AS | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Diflunisal | OA, RA, mild to moderate pain | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Digitoxin | Congestive HF, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, PAT, cardiogenic shock | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Digoxin | Heart failure, atrial fibrillation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Dimethyl Fumarate | Psoriasis, Multiple Sclerosis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Dipyridamole | Thromboembolism Prophylaxis Post-Cardiac Valve Replacement | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Disulfiram | Chronic alcoholism | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Donepezil | Alzheimer’s Disease | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Doxazosin | Hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Doxycycline | Respiratory/urinary tract/ophthalmic infection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Dutasteride | Benign prostatic hyperplasia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ebastine | Allergies | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Efavirenz | Anti-retroviral | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Eflornithine | DFMO | Adjunct to laser therapy for facial hirsutism in women, African trypanosomiasis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enalapril | Hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Enoxaparin | Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Epalrestat | Diabetes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Esomeprazole | Antacid | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ethacrynic Acid | Etacrynic acid | Diuretic | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Etodolac | Analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Famotidine | Antacid | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fasudil | Vasodilator | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Felodipine | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Fenofibrate | Hyperlipidaemia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Finasteride | Benign prostatic hyperplasia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fingolimod | Multiple Sclerosis | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Flubendazole | Parasitic infection | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Flucytosine | 5-Fluorocytosine | Candida and/or Cryptococcus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fluoxetine | Prozac | Depression | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Fluspirilene | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Flurbiprofen | Analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fluvastatin | Hyperlipidaemia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fluvoxamine | Depression | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Ganciclovir | Anti-viral | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Glipizide | Diabetes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Glibenclamide | Glyburide | Diabetes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Griseofulvin | Fungal infections | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Haloperidol | Psychotic disorders | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Hydralazine | Hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Malaria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Hymecromone | Antispasmodic | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Ibandronic acid | Ibandronate | Osteoporosis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Ibuprofen | Analgesia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Imipramine | Depression | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Indomethacin | Indometacin | Analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Irbesartan | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Itraconazole | Fungal infections | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ivermectin | Parasitic infection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Ketamine | Anaesthetic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Ketoconazole | Fungal infections | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ketorolac | Post-operative analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Lamotrigine | Epilepsy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Lansoprazole | Antacid | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| L-Arginine | Nutraceutical | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Leflunomide | Arthritis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Levetiracetam | Epilepsy | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Levofloxacin | Antibiotic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Levonorgestrel | Contraceptive | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| L-Glutamine | Nutraceutical | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Lidocaine | Anaesthetic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Lithium | Bipolar disorders | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Loperamide | Diabetes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Lopinavir | Anti-retroviral | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Loratadine | Allergies | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Losartan | Hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Lovastatin | Hyperlipidaemia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Loxoprofen | Analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Macitentan | Pulmonary arterial hypertension | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Manidipine | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Maraviroc | Anti-retroviral | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Mebendazole | Parasitic infection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Meclofenamate | Meclofenamic acid | Analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Mefloquine | Malaria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Megestrol Acetate | Hormone | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Melatonin | Insomnia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Meloxicam | Analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Memantine | Alzheimer’s Disease | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Mepacrine | Quinacrine | Parasitic infection | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mesalazine | Mesalamine, 5-aminosalicylic acid | Inflammatory bowel disease | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Metformin | Diabetes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Methazolamide | Antiglaucoma, diuretic | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Methimazole | Thiamazole | Hyperthyroidism | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Methylnaltrexone | Opioid-induced constipation | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Metoclopramide | Anti-emesis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Midazolam | Sedation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Mifepristone | Abortifacient | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Minocycline | Antibiotic | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Mirtazapine | Depression | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Mometasone | Mometasone furoate | Asthma prophylaxis | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Montelukast | Allergies | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Mycophenolate | Mycophenolic acid | Immunosuppressant | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Nadroparin | Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Naftopidil | Benign prostatic hyperplasia | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Naltrexone | Opioid receptor antagonist | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Naproxen | Analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Nelfinavir | Anti-retroviral | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Niclosamide | Parasitic infection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Nicotinamide | Niacinamide | Niacin Deficiency, Skin cancer chemoprevention | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nifedipine | Hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Nifurtimox | Chagas disease, African sleeping sickness | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Nimodipine | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Nisoldipine | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Nitazoxanide | Anti-protozoal | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Nitisinone | Hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Nitroglycerin | Glyceryl trinitrate | Nitro-vasodilator | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nitroxoline | Antibiotic | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Norethandrolone | Aplastic anaemia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Noscapine | Anti-tussive | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Olanzapine | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Olmesartan | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Olsalazine | Rheumatoid arthritis; ulcerative colitis; active Crohn’s Disease. | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Omega 3 | Lovaza, Fish Oil, Omacor, eicosapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid | Hyperlipidaemia | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Omeprazole | Antacid | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Orlistat | Obesity | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Ormeloxifene | Contraceptive | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Oseltamivir | Anti-viral | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Ouabain | Cardiac arrhythmia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Oxcarbazepine | Epilepsy | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Pamidronic acid | Pamidronate | Osteoporosis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pantoprazole | Antacid | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Paricalcitol | Vitamin D2 | Hyperparathyroidism | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Penfluridol | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Pentamidine | Parasitic infection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Pentoxifylline | Peripheral artery disease | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Perphenazine | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Phenoxybenzamine | Pheochromocytoma | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Phentolamine | Vasodilator | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Phenylbutyrate | Glycerol Phenylbutyrate | Urea cycle disorders | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Phenytoin | Epilepsy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Pimozide | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Pioglitazone | Diabetes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Pirfenidone | Anti-fibrotic | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Piroxicam | Analgesia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Plerixafor | AMD3100 | Autologous HSCT | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pravastatin | Hyperlipidaemia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Prazosin | Hypertension | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Prochlorperazine | Prochlorperazine dimaleate | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Promethazine | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Propafenone | Anti-arrhythmic | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Propranolol | Hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Pyridoxine | Vitamin B6 | Vitamin B6 deficiency | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pyrimethamine | Parasitic infection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Pyrvinium Pamoate | Pyrvinium | Parasitic infection | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Quetiapine | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Rabeprazole | Antacid | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Ranitidine | Antacid | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ranolazine | Anti-angina | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Repaglinide | Diabetes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Ribavirin | Anti-viral | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Rifabutin | Antibiotic | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Riluzole | ALS | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Risperidone | Psychotic disorders | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Ritonavir | Anti-retroviral | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Roflumilast | COPD | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Rosuvastatin | Hyperlipidaemia | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Roxithromycin | Bacterial infections | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Sertraline | Depression | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Sildenafil | Erectile dysfunction | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Simvastatin | Hyperlipidaemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Sirolimus | Rapamycin | Inhibit organ transplant rejection | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sodium Aurothiomalate | Active progressive rheumatoid arthritis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Sodium Bicarbonate | Relief of wind and griping pains | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Spironolactone | Congestive cardiac failure, Hepatic cirrhosis with ascites and oedema, Malignant ascites, Nephrotic syndrome, Diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Sulfasalazine | Rheumatoid arthritis; ulcerative colitis; active Crohn’s Disease. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Sulindac | Relief of signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, acute painful shoulder (acute subacromial bursitis/supraspinatus tendinitis), and acute gouty arthritis. | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Tadalafil | Erectile dysfunction | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Telmisartan | Hypertension, cardiovascular prevention | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Terbinafine | Treatment of tinea pedis (athlete’s foot), tinea cruris (dhobie (jock) itch) and tinea corporis (ringworm) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Thiabendazole | Parasitic infection | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Thioridazine | Psychotic disorders | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Ticagrelor | Prevention of atherothrombotic events in combo with ASA | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Ticlopidine | Prevent strokes, blood loss | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Tigecycline | Infections | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Timolol | Hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, migraine | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Tinzaparin | Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Tioconazole | Parasitic infection | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Tocilizumab | Rheumatoid arthritis | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Tofacitinib | Rheumatoid arthritis | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Tolfenamic Acid | Tolfenamate | Migraine | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Topiramate | Epilepsy (tonic clonic seizure) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Tranexamic Acid | Blood loss - fibrinolysis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Trazodone | Depression, anxiety | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Triamterene | Diuretic, oedema in cardiac failure, cirrhosis of the liver or the nephrotic syndrome, and in that associated with corticosteroid treatment | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Trifluoperazine | Psychotic disorders | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Trimetazidine | Angina pectoris | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Ulinastatin | Severe sepsis & pancreatitis | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Valproic Acid | Valproate | Epilepsy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Valsartan | Hypertension, myocardial infarction, heart failure | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Vardenafil | Erectile dysfunction | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Verapamil | Hypertension, angina pectoris | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Verteporfin | Exudative age-related macular degeneration | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Warfarin | Prophylaxis of systemic embolism, of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Zidovudine | Azidothymidine | Anti-retroviral | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zoledronic Acid | Zoledronate | Osteoporosis, prophylaxis of skeletal fractures and treat hypercalcaemia of malignancy, treat pain from bone metastases | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

References

- 1.Langedijk J, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Slijkerman DS, et al. Drug repositioning and repurposing: terminology and definitions in literature. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20(8):1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sivapalarajah S, Krishnakumar M, Bickerstaffe H, et al. The prescribable drugs with efficacy in experimental epilepsies (PDE3) database for drug repurposing research in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2018;59(2):492–501. doi: 10.1111/epi.13994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercorelli B, Palù G, Loregian A. Drug repurposing for viral infectious diseases: how far are we? Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(10):865–876. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakkar AK, Singh H, Medhi B. Old wines in new bottles: repurposing opportunities for Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;830:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah RR, Stonier PD. Repurposing old drugs in oncology: opportunities with clinical and regulatory challenges ahead. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. The repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO) project. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:442. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2014.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pantziarka P, Bouche G, André N. ‘Hard’ Drug Repurposing For Precision Oncology: The Missing Link? Front Pharmacol. 2018;9(June):637. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in your medicine cabinet: untapped opportunities for cancer therapy? Future Oncol. 2015;11(2):181–184. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gyawali B, Pantziarka P, Crispino S, et al. Does the oncology community have a rejection bias when it comes to repurposed drugs? Ecancermedicalscience. 2018;12:10–14. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2018.ed76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouche G, Pantziarka P, Meheus L. Beyond aspirin and metformin: the untapped potential of drug repurposing in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72(72):S121–S122. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(17)30479-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pantziarka P, Sukhtame V, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing non-cancer drugs in oncology — how many drugs are out there? bioRxiv. 2017;1 [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO model lists of essential medicines. [20/08/18]. (n.d.) [ http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/]

- 13.Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database Issue):D901–D906. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Oslo, Norway: WHO; 2003. The anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mestres J, Gregori-Puigjané E, Valverde S, et al. Data completeness--the Achilles heel of drug-target networks. Nature Biotechnol. 2008;26(9):983–984. doi: 10.1038/nbt0908-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Fang H, Reagan K, et al. In silico drug repositioning: what we need to know. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18(3–4):110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herr HW, Morales A. History of bacillus Calmette-Guerin and bladder cancer: an immunotherapy success story. J Urol. 2008;179(1):53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tai L-H, Zhang J, Scott KJ, et al. Perioperative influenza vaccination reduces postoperative metastatic disease by reversing surgery-induced dysfunction in natural killer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(18):5104–5115. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Association between post-diagnostic use of cholera vaccine and risk of death in prostate cancer patients. Nature Commun. 2018;9(1):2367. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04814-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amelio I, Gostev M, Knight RA, et al. DRUGSURV: a resource for repositioning of approved and experimental drugs in oncology based on patient survival information. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(2):e1051. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee BKB, Tiong KH, Chang JK, et al. DeSigN: connecting gene expression with therapeutics for drug repurposing and development. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(Suppl 1):934. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3260-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hintzsche JD, Yoo M, Kim J, et al. IMPACT web portal: oncology database integrating molecular profiles with actionable therapeutics. BMC Med Genomics. 2018;11(Suppl 2):4–9. doi: 10.1186/s12920-018-0350-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liniker E, Harrison M, Weaver JMJ, et al. Treatment costs associated with interventional cancer clinical trials conducted at a single UK institution over 2 years (2009–2010) Br J Cancer. 2013;109(8):2051–2057. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mañes-Sevilla M, Romero-Jiménez R, Herranz-Alonso A, et al. Drug cost avoidance in clinical trials of breast cancer. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018. 1078155218775193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Verbaanderd C, Meheus L, Huys I, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology: next steps. Trends Cancer. 2017;3(8):543–546. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]