INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is understood as a chronic disabling condition, which has a significant negative impact on the life of a patient and their family. When the onset of illness for schizophrenia is before 18 years of age, it is known as early-onset schizophrenia (EOS). Further, based on the age of onset, schizophrenia is categorized as very early onset schizophrenia (VEOS) when the age of onset is <13 years and EOS when the age of onset is between 13 and 18 years. When the onset of illness is before 13 years of age, it is known as childhood-onset schizophrenia (COS). Epidemiological data suggest that onset of schizophrenia in childhood is rare, especially before the age of 6 years. The peak age for onset of schizophrenia is considered to be 15–30 years. The prevalence of various psychotic disorders has been reported to be 0.4% among children and adolescents aged 5–18 years. In terms of relationship between age of onset and gender, it is suggested that EOS is more often seen in males; however, there is equal distribution between both the genders, as the age of onset increases.

SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT

These guidelines are based on the recent developments in the area of management of EOS. These guidelines are not designed specifically for any treatment setting, and minor modifications may be required based on the needs of the patients in a specific setting. These guidelines are not a substitute of professional knowledge of a treating psychiatrist; instead, these guidelines provide a broad framework for the assessment and management of patients with EOS, and these may have to be tailored to the needs of the individual patient.

ASSESSMENT

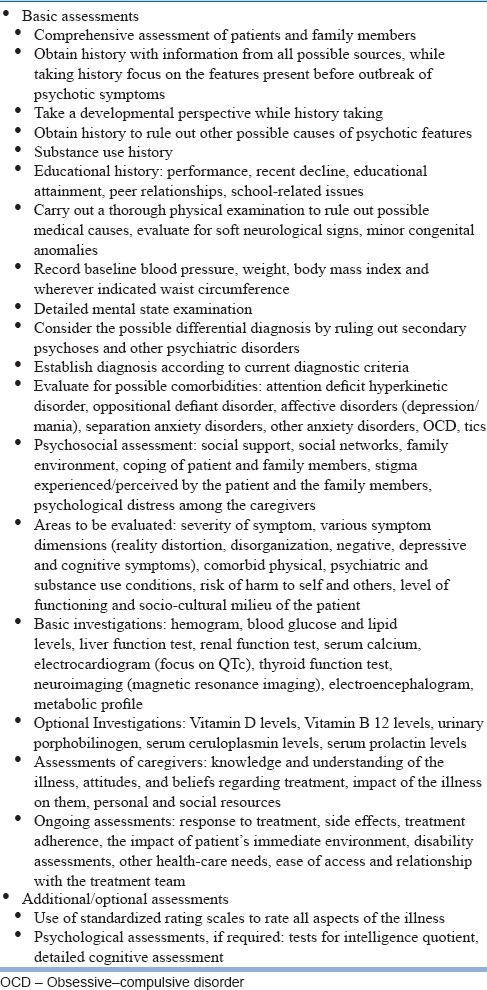

A thorough assessment of a patient and their family members/caregivers need to be done. The most important aspect of assessment is obtaining a detailed history from all possible sources and carrying out a thorough physical examination and mental state examination [Table 1]. Diagnosis of schizophrenia in children and adolescent is also established using the same criteria of International Classification of Diseases and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual as used for adults. In general, it is said that validity of diagnosis of schizophrenia in children <6 years has not been established. Patients with COS are often misdiagnosed, especially during the time of onset of illness. The common misdiagnosis includes developmental disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, affective disorders, and other psychotic disorders. Proper diagnosis requires detailed history-taking with focus on the evolution of the illness and proper mental status examination. Many a times, diagnosis is not clear at the first instance and proper establishment of diagnosis may require multiple assessments including repeated mental status examination.

Table 1.

Assessment of patient presenting with early-onset schizophrenia

The assessment should cover evaluation of various symptom dimensions, severity of symptoms, comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions, particularly comorbid substance abuse, risk of harm to self or others, level of functioning, and socio-cultural milieu of the patient. Onset of EOS is usually insidious. Patients with EOS may have a history of social withdrawal and isolation, academic difficulties, behavioral problems, speech and language difficulties, and cognitive problems. In general, patients with EOS exhibit features of hallucinations, thought disturbance, and flat affect. Delusions and catatonic symptoms are less frequently encountered compared to hallucinations. However, while evaluating children and adolescents, it is important to distinguish psychopathology from normal childhood experiences such as imagination and fantasy. Similarly, before labeling something as formal thought disorder, it is important to consider the speech and language difficulties associated with developmental disorders. It is important to remember that all children who report hallucinations do not necessarily have schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders. Children with autism spectrum disorders can have fantasies and odd beliefs (able to talk to inanimate toys), social awkwardness, and concrete thinking. If the clinicians are not very well versed with the presence of these features in children with autism spectrum disorder and fail to take a developmental perspective, many a times these children are diagnosed with EOS. In general, when the child presents with odd behavior from very early age along with deficits in social and communication domains, in the absence of clear-cut psychotic symptoms, it is important to first consider the possibility of autism spectrum disorder, rather than EOS. However, it is important to remember that many children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder go on to develop schizophrenia later on.

Sometimes, children and adolescents with schizophrenia may present with symptoms of odd behavior and social withdrawal symptoms. Such children should be evaluated for personality disorders such as schizoid and schizotypal disorder before considering the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Usually, compared to adolescents with schizophrenia, adolescents with schizoid and schizotypal disorders may have persistent pattern of thinking, emotional coldness, and odd behaviors. Usually, evaluation of history of the patients with personality disorders will reveal the presence of stable and pervasive patterns of thinking, which is significantly in odds with the sociocultural norms; in contrast, in patients with schizophrenia, there may be evidence of otherwise normal personality, before the emergence of symptoms of schizophrenia. When the diagnosis is not clear, it is advisable to keep the diagnosis open and follow-up of the patient over time, which helps in clarification of the diagnosis. Many patients with schizoid and schizotypal disorder also go on to develop schizophrenia later on.

Whenever feasible and when diagnosis is in doubt, it is suggested that clinician can utilize semi-structured interviews such as schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children aged 12 years or the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Further, wherever feasible, unstructured assessments can be supplemented using appropriate standardized rating scales.

Many patients with EOS will also have cognitive disturbances in the domains of memory, attention, and executive function and in the form of overall global impairment. Looking at the old records or proper history-taking often reveals preexisting cognitive disturbance in the in the domains of attention, processing speed, verbal reasoning, and working memory. Some of these problems may manifest as academic decline or problems in academics. While evaluating the functional decline, it is important to evaluate at the decline in or failure to achieve age-appropriate interpersonal skills and academic achievements. Besides mental status examination, it is important to carry out a thorough physical examination to rule out medical causes of psychotic symptoms and to evaluate for comorbid physical illnesses.

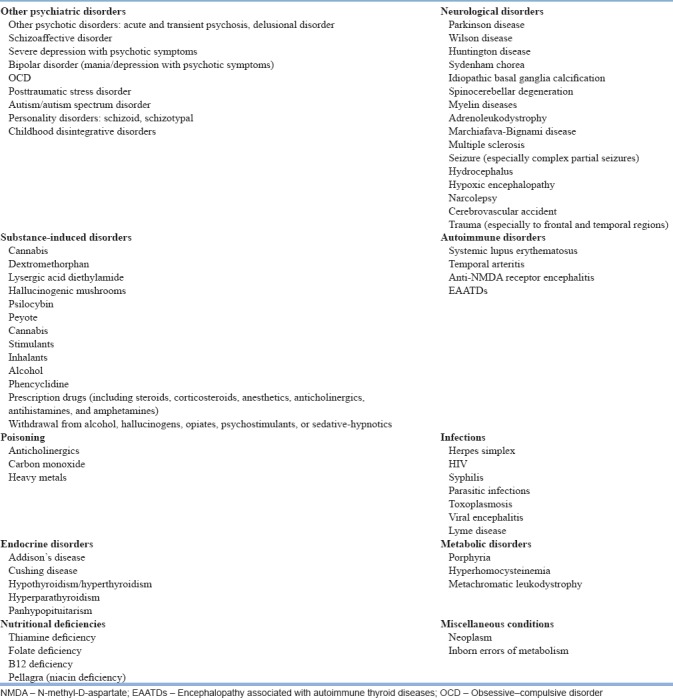

Rule out possible medical disorders and other psychiatric disorders: Before considering the diagnosis of schizophrenia, it is important to rule out other psychiatric disorders and underlying medical illnesses, which can have similar manifestations [Table 2]. Ruling out underlying medical illnesses is of paramount importance in children and adolescents because psychosis in children has been reported to be associated with inborn errors of metabolism, various genetic syndromes (such as Juvenile Huntington's disease, Klinefelter syndrome, Turner syndrome, and Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome), autoimmune disorders, endocrine diseases, nutritional deficiencies, and central nervous system infections. Features which should alert a clinician for possible organic cause include acute/abrupt onset of illness, onset of illness in the background of recent surgery, viral infection or medications, cognitive or developmental regression, and presence of atypical features such as visual hallucinations and lack of negative symptoms. Other clinical features which prompt for evaluation of organic causes include presence of confusion, catatonia, development of rare or serious neurological side effects, presence of seizures, presence of ataxia, neuropathy, stroke, skin lesions, cataract, malar rash, hepatosplenomegaly, gastrointestinal signs, and dysmorphic facial appearance. Inborn errors of metabolism should be suspected, while the early development history suggests the presence of severe hypotonia during the initial part of life, developmental delay, presence of dysmorphic features, history of nausea, diarrhea and other gastrointestinal features, presence of catatonia, and cognitive decline.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of schizophrenia in children and adolescents

Certain clinical conditions such as mood disorders, substance-induced psychoses, and psychoses secondary to physical illnesses may present with similar picture as EOS. These conditions must be ruled out on the basis of detailed history, examination, and additional investigations. Detection of comorbid substance abuse/dependence requires high index of suspicion, and wherever facilities are available, urine or blood screens (with prior consent) can be used to confirm the presence of comorbid substance abuse/dependence. Detailed physical examination needs to be done to rule out the presence of any physical illness and also to rule out psychoses secondary to physical illnesses. A study reported that possibility of an underlying organic cause need to be suspected if the history is characterized by atypical description (such as very early onset of symptoms, acute onset, onset of illness apparently triggered by surgery, viral infections or use of medications, cognitive regression, and behavioural regression), atypical clinical features (such as confusion, catatonia, evidence of rare or serious neurological adverse reaction to treatment), and presence/possibility of physical symptoms (such as seizures, presence of malar rash, gastrointestinal signs, and dysmorphic features).

Investigations: Investigations must be carried out judiciously. However, if physical illnesses are suspected, then the clinicians should not hesitate to carry out specific investigations to rule out the same. Basic laboratory investigations include hemogram, liver function tests, renal function test, and electrocardiogram. If the substance use is suspected, then urine tests for substances of abuse may be done. Other investigations may also be done based on the history and finding of the physical examination. Wherever feasible, cognitive assessment needs to be done. Neuroimaging can be done when neurological illnesses are suspected. It is important to take sexual history in young patients and document the last menstrual period in those adolescents who are sexually active and urine pregnancy test may be considered in these patients before starting antipsychotic medications. Assessment of family/caregivers: Assessment of parents/family members must involve assessment of their knowledge and understanding about the disorder, their attitudes and beliefs with respect to the treatment, impact of the illness on them, and their personal and social resources.

Making the diagnosis: At times, a definitive diagnosis of EOS requires time and repeated assessments. In fact, it is suggested that diagnosis of schizophrenia must be made with great caution and sensitivity as it is associated with significant negative psychosocial consequences, both for the patient and also for their caregivers. Whenever the diagnosis is in doubt, it is better to observe the patient without prescribing any antipsychotic medications. However, decision to keep the patient off medication must be evaluated against the risks of delaying treatment or the potential for harm to self and others in acutely ill patients. As in other age groups, the diagnosis of schizophrenia is not a one-time affair, but a continuous process and based on the subsequent information from patients and caregivers, and on repeated clinical evaluations, the diagnosis may need re-evaluation.

At-risk mental state (ARMS): At times, patients are brought to the clinic in whom the diagnosis of schizophrenia cannot be made with certainty; however, in view of symptom profile, these patients are considered as having prodrome of schizophrenia or “at-risk mental state (ARMS)” subject. The symptoms in these subjects may be in the form of disturbances in emotion, cognition, perception, communication, motivation, and sleep. These features are labeled differently by various diagnostic symptoms such as basic symptoms, attenuated positive symptoms, brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms, features of schizotypal personality disorder, and genetic risk paired with functional deterioration. Other commonly used term for this group of patients is “ARMS.” People with ARMS may manifest with symptoms of low mood, anxiety, social isolation, educational/occupational failure, and brief/intermittent psychotic symptoms, which are also known as attenuated psychotic symptoms. The duration of prodrome can vary from patient to patient, from few weeks, months, to years. In patients who present with vague symptoms and in whom prodrome is suspected, it is important to use specific assessment instruments to evaluate the prodrome or the ARMS. Some of the instruments which can be used for assessment of these patients include instrument for the retrospective assessment of onset of schizophrenia, scale for prodromal symptoms, structured interview of prodromal symptoms, and comprehensive assessment of ARMS. However, it is important to remember that all patients with prodrome do not go on to develop psychotic disorders. However, it is important to closely follow-up these patients for emergence of psychosis. Psychological intervention can be provided to these patients.

Over the period of treatment, the focus of assessment should shift to assessment of response to treatment, side effects experienced by the patient, monitoring of metabolic side effects, medication adherence, treatment adherence, educational difficulties, evaluation of disability, other health care needs, and impact of the illness on the patient and caregivers.

FORMULATING A TREATMENT PLAN

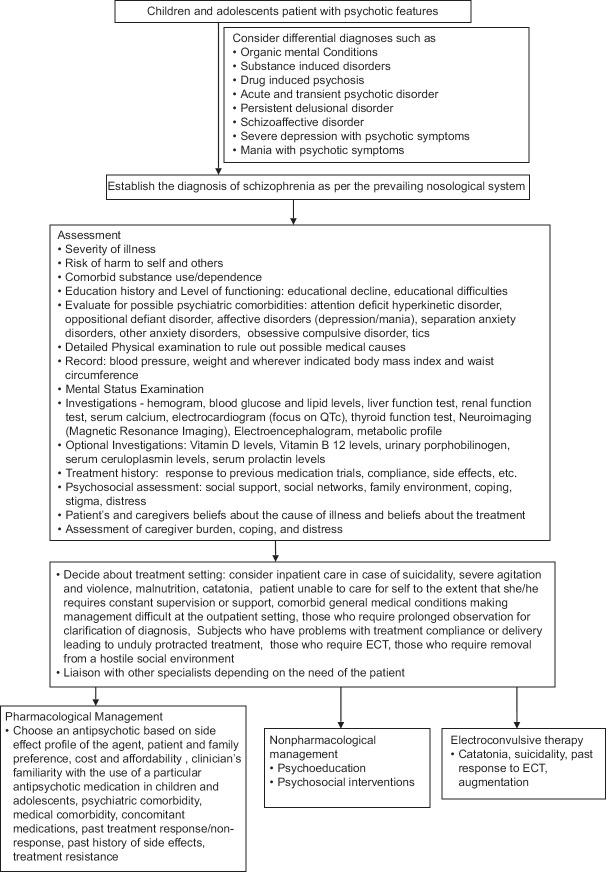

As with adult patients with schizophrenia, formulation of treatment plan involves deciding about treatment setting, treatments to be used, and areas to be addressed [Figure 1]. Treatment plan should be drawn by consulting all the persons involved in the care of the patient. The treatment plan formulated should be feasible, flexible, and practical to address the needs of the patients and the family members. The treatment plan should be continuously modified based on the regular assessment of the patient and the family members.

Figure 1.

Initial evaluation and management plan for schizophrenia in children and adolescents

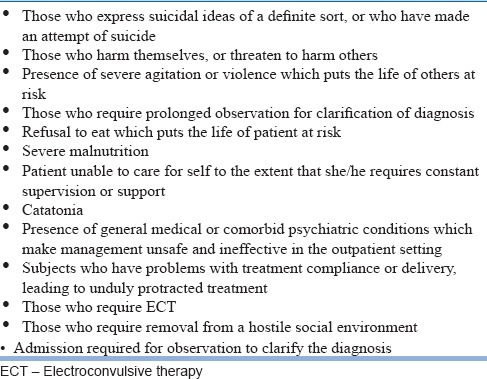

CHOICE OF TREATMENT SETTING

Patients with EOS must be managed in the least restrictive environment. Most of the patients can be managed on outpatient basis. However, some of the patients may require inpatient care. The indications for inpatient care are given in Table 3. All the patients admitted to the inpatient setting should have accompanying family caregivers. Whenever inpatient care facilities are not available, then the family needs to be informed about the need for inpatient care and admission in the nearest available inpatient facility may be facilitated. However, it is to be remembered that rules as laid by the Mental Health Care Act, 2017, need to be abided in providing inpatient care to children and adolescents.

Table 3.

Indications for admission in patients with early-onset schizophrenia

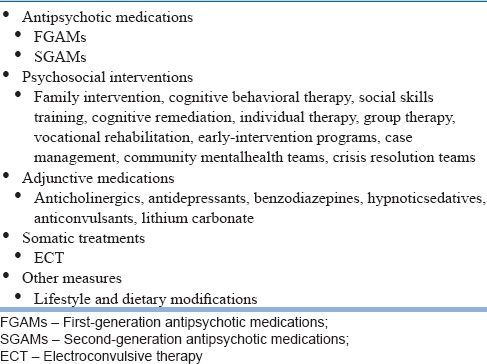

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF EARLY-ONSET SCHIZOPHRENIA

Treatment options for the management of schizophrenia include antipsychotic medications, psychoeducation, psychosocial interventions, adjunctive medications, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Options for management for schizophrenia

Antipsychotics

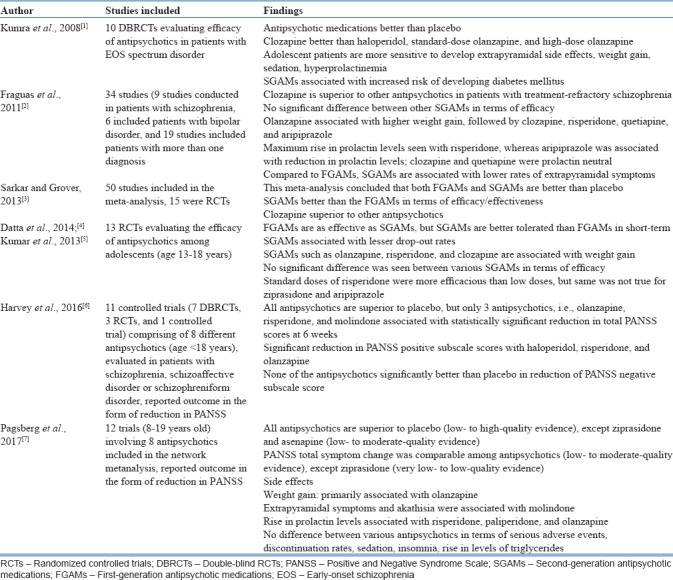

Antipsychotic medications are considered as the first-line treatment for patients with EOS. However, these are recommended to be used along with psychosocial interventions. Compared to data in adults, the efficacy data on use of antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents are limited. Further, all the antipsychotics have not been evaluated in patients with EOS aged <18 years. Most of the antipsychotics have been evaluated in patients aged 13–18 years. The antipsychotics which have been evaluated in one or more randomized controlled trial (RCT) include haloperidol, aripiprazole, asenapine, paliperidone, risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine, molindone, ziprasidone, and clozapine. Majority of the studies which have evaluated different antipsychotics in adolescent patients have been industry sponsored. One of the non-industry sponsored studies which have evaluated the efficacy of different antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia/schizophrenia spectrum disorder includes Treatment of Early-Onset Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders (TEOSS) study. Many meta-analyses have evaluated the existing short-term (6–12-week trials) efficacy/effectiveness data with respect to use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia [Table 5]. Some of the common conclusions of these meta-analyses include superior efficacy of antipsychotic medications when compared to placebo (except possibly for ziprasidone), lack of significant difference in efficacy between First generation Antipsychotic Medications (FGAMs) and Second Generation Antipsychotic Medications, and tolerability of SGAMs being better than FGAMs. Overall, antipsychotics have superior efficacy in terms of reduction in positive symptoms, and there is lack of significant beneficial effect on negative symptoms when compared to placebo. Data also suggest that there is no difference in efficacy between different SGAMs, except for the fact that clozapine is superior to other antipsychotics. SGAMs are associated with lower dropout rates compared to FGAMs. In terms of adverse effects, there is differential adverse effect profile of various antipsychotics, with extrapyramidal symptoms being more common in patients receiving FGAMs, hyperprolactinemia being more common with risperidone and FGAMs, and weight gain and metabolic side effects being more common with SGAMs, especially olanzapine. It is in general also suggested that side effect of antipsychotics in adolescents is similar to that seen in adult patient, except for the fact that adolescents experience more side effects.

Table 5.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating various antipsychotic medications among patients with early-onset schizophrenia

Little is known about the predictors of response to treatment in patients with EOS. In TEOSS study, which was a National Institute of Health sponsored study, which compared response to olanzapine, risperidone, and molindone. This study evaluated the predictors of response and reported that higher severity of symptoms at the baseline, history of being in an early education program and previous prescription of a mood stabilizer were associated with better treatment response. Higher dropout rates were associated with aggressive behaviors as per the report of the parents and being of African-American origin (Gabriel et al., 2017).

There are limited data in terms of long-term efficacy/effectiveness of various antipsychotics in patients with EOS. Patients, who participated in the 8-week DBRCTs as part of TEOSS study, were continued on the same medication in the double-blind fashion for another 44 weeks. This study showed lack of difference in the discontinuation rates between the three antipsychotics used. Only 12% of the patients continued on the originally randomized antipsychotic medication. There was no difference in the efficacy of three antipsychotics used. Molindone was more commonly associated with akathisia, whereas risperidone was more often associated with rise in serum prolactin levels. Although olanzapine and risperidone were associated with weight gain and metabolic side effects in the acute phase, at the end of maintenance phase, there was no difference between the three antipsychotics.[8] A survey of Medicaid claims data which evaluated the data related to use of olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone suggests that three-fourth of the adolescents with schizophrenia and related disorders discontinue their medications within 180 days of starting of these antipsychotics, with no significant difference between the various antipsychotic medications.[9] A naturalistic study evaluated the 6-month outcome of children and adolescent (9–17 years), diagnosed with schizophrenia and other related psychotic disorders treated with olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine. In general, there was no significant difference in the effectiveness of these antipsychotic medications. Olanzapine was associated with significantly higher weight gain when compared with risperidone and quetiapine. However, compared to olanzapine, use of risperidone was associated with more extrapyramidal side effects (EPS).[10] Long-term data of patient receiving clozapine suggest that among patients with EOS, a very high proportion of patients (72.5%), who are started on clozapine, are maintained on the same for long run (>2 years), rates even exceeding than those reported in patients with adult-onset schizophrenia.

It is to be remembered that depot antipsychotic medications have not been evaluated in children and adolescents.

Choice of antipsychotic medication in children and adolescents

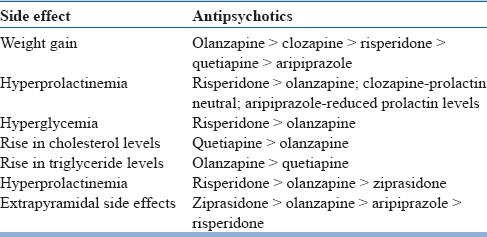

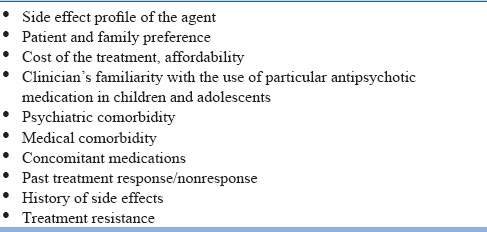

Based on the available evidence, antipsychotic medications are considered as the first-line treatment for schizophrenia in adolescents, which must be used along with the psychosocial management. Among the various antipsychotics, it is generally suggested that SGAMs, other than clozapine, may be used as the first-line agents. The United States Food and Drug Administration have approved haloperidol, molindone, risperidone, aripiprazole, quetiapine, paliperidone, and olanzapine for the management of schizophrenia among adolescents aged 13 years or more. It is suggested that selection of specific agent should be based on the side effect profile [Table 6] and various other factors [Table 7]. Clozapine should be reserved for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Table 6.

Risk of side effects with various antipsychotics based on the data in adolescents

Table 7.

Factors that influence the selection of antipsychotics

When prescribing antipsychotics, the clinicians need to explain the patient and the family members about the available options, possible side effects, need for monitoring, what to do in case the side effects are encountered, and behavioral measures required to minimize the side effects.

Doses of antipsychotic medication

In general, it is suggested that whenever an antipsychotic is to be given, it should be started in the lower doses and the patients should be closely monitored for emergent side effects. The doses should be gradually increased to the minimal effective therapeutic doses. It is noted that patients of Indian origin generally require lower doses compared to their counterparts from the West.

Route of administration

Only oral formulations of antipsychotics have been evaluated in children and adolescents. In general, use of depot antipsychotic medications is not recommended in children and adolescents. The Guidelines of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) suggests that depot antipsychotics may only be considered in adolescents who have evidence of chronic psychotic symptoms in the form of documented history and a history of poor medication adherence.

Adequate antipsychotic trial

An adequate trial of antipsychotic is considered as use of maximum tolerable therapeutic doses for at least 6–8 weeks, except for clozapine, where the minimum duration of trial should be at least 3–6 months. If the patient does not show adequate therapeutic response, then a change in antipsychotic medication needs to be considered.

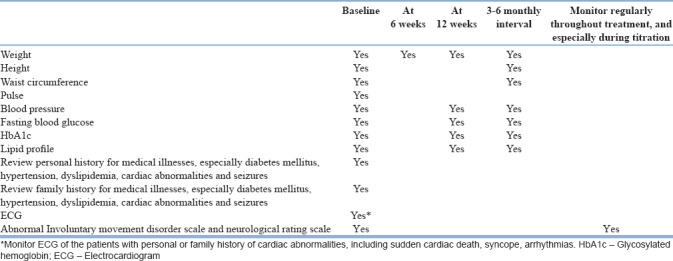

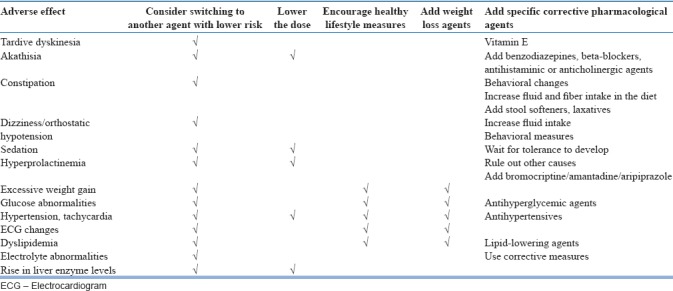

Monitoring of patients while receiving antipsychotics for side effects

All the patients receiving antipsychotics should be monitored throughout the treatment for EPS, i.e., drug-induced parkinsonism, dystonia, akathisia, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Patients should also be monitored for other side effects [Tables 8 and 9] and managed accordingly. EPS is more often seen in patients receiving FGAMs, especially high-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol. EPS is also known to occur with SGAMs. Acute EPS is usually seen during the first few days or weeks of starting treatment and can manifest in the form of acute dystonia, pseudo-parkinsonism, and akathisia. Acute EPS is usually dose dependent and subsides with discontinuation of the offending agent. Unlike acute EPS, chronic EPS is not dose dependent and usually encountered with prolonged use (months to years) of antipsychotics and manifests in the form of tardive dyskinesia, tardive dystonia, and tardive akathisia. Chronic EPS often persists even after discontinuation of the offending medication. Initial step in the management of parkinsonism involves reduction in the dose of the offending agent. If reduction in dose does not lead to resolution of symptoms or leads to inadequate control of symptoms or worsening of symptoms, then change to an antipsychotic medication with lower EPS potential needs to be considered. If a patient has responded to or are responding to particular antipsychotic medication and is experiencing parkinsonism symptoms, then a short course of anticholinergic medications may be considered. Acute dystonia is usually encountered after administration of first few doses of antipsychotics and respond to administration of parenteral anticholinergic or antihistaminergic medications. A short course of anticholinergic medications may also be useful in the prevention of acute dystonia. Management of acute akathisia involves reduction in dose and change of antipsychotic medication to an agent with lower EPS potential in a sequential manner. Severe akathisia in few patients may warrant the use of beta-blockers and benzodiazepines such as clonazepam or lorazepam. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is an acute medical and psychiatric emergency, management of which involves stopping the offending agent, supportive measures and use of bromocriptine, amantadine, or dantrolene. Patients with NMS, who do not respond to these treatments, may benefit with ECT.

Table 8.

Monitoring of patients receiving antipsychotics

Table 9.

Management of other side effects

In patients who report sedation, wait-and-watch policy must be followed in the beginning; however, if this is not beneficial, then reduction in dosage must be considered. Patients receiving clozapine and chlorpromazine often experience dose-dependent anticholinergic side effects which improve with reduction in the dose of antipsychotic or addition of anticholinergic agent.

All antipsychotics lead to varying rates of sexual dysfunction, with higher rates noted for FGAMs than SGAMs. Sexual dysfunction with FGAMs and risperidone is related to increase in serum prolactin levels, which disrupts the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Females are considered to be more sensitive to hyperprolactinemia-related sexual dysfunction. First step in the management of sexual dysfunction involves reduction in the dose of antipsychotic medication, and if this fails, then a change in antipsychotic is needed. However, if a change of antipsychotic is not possible, then management of hyperprolactinemia with bromocriptine or amantadine may be considered.

As antipsychotics are considered to increase the prevalence of metabolic abnormalities, it is recommended that all the patients receiving antipsychotics must be closely monitored for side effects. AACAP and NICE guidelines have given specific recommendations for monitoring of patients on various antipsychotic medications. It is important to monitor the patient for metabolic abnormalities including the weight gain. SGAMs are known to cause significant weight gain, and significant rise in serum triglyceride levels is also seen in patients receiving various SGAMs [Table 6]. All patients must be evaluated for metabolic disturbance before starting of antipsychotics and then monitored [Table 8]. Frequency of monitoring can be increased in those with personal and family history of obesity, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and/or cardiovascular disease.

However, in Indian setting, due to poor follow-up rates and inadequate resources at remote places, it may not be possible to monitor all the parameters regularly. In such situation, at least weight and fasting blood glucose levels should be monitored. Centers with resources may consider complete monitoring of metabolic parameters.

Besides the monitoring, all the patients and their family members must be informed about the need and importance of healthy lifestyle measures such as taking a healthy diet, regular exercise, and abstinence from smoking and alcohol. A close liaison must be maintained with endocrinologist and cardiologist to address the emergent issues. If a patient has significant weight gain or other metabolic disturbances with one antipsychotic medication, then he should be shifted to another agent with lower risk of gaining weight or causing metabolic disturbances. If a patient has significant metabolic disturbances, then these must be managed in liaison with the specialists. Gain in weight by more than 7% or emergence of hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, or any other significant cardiovascular or metabolic side effect is considered an indicator for change in antipsychotic medication. However, before switching a review of entire course of the illness, other comorbid physical illnesses, side effect profile of medication which caused metabolic side effects and the potential side effects with medication to which patient is to be switch must be taken into account, before implementing a switch. If switching of antipsychotic is not feasible, then use of metformin or topiramate may be considered, along with more intensive dietary and lifestyle modifications.

Use of antipsychotic medications is also associated with cardiac side effects such as orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, and QTc prolongation. QTc prolongation is one of the dreaded side effects associated with use of antipsychotics and a QTc interval of more than 500 millisecs is associated with increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias, known as “torsades de pointes,” which may lead to ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death. Among the various SGAMs, ziprasidone is known to higher risk of QTc prolongation, and in terms of FGAMs, haloperidol in high doses, thioridazine and pimozide are associated with higher risk of QTc prolongation.

Hypotension is commonly seen with clozapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and chlorpromazine and is attributed to antiadrenergic properties of these drugs. The risk of hypotension can be minimized by initiating treatment with lower doses and very slow titration of medication. If a patient develops hypotension, then at the first step, a reduction in the dose of the offending agent is considered. If this does not lead to resolution of symptoms, then a change to antipsychotics with lower antiadrenergic properties must be considered. Other strategies such as use of stockings, increasing the salt intake, and use of fluid-retaining corticosteroid, i.e., fludrocortisone, are also useful in some of the patients.

Some patients receiving clozapine experience tachycardia due to anticholinergic activity and this can be managed with low-dose peripherally acting beta-blockers.

While using clozapine, hemogram must be monitored as per the established guidelines.

Response to treatment

Available evidence suggests that the use of antipsychotics in adolescents is associated with significant improvement in positive symptoms, with nonsignificant improvement in negative symptoms. Effect on antipsychotics on cognitive symptoms among adolescents has not been evaluated among the adolescents.

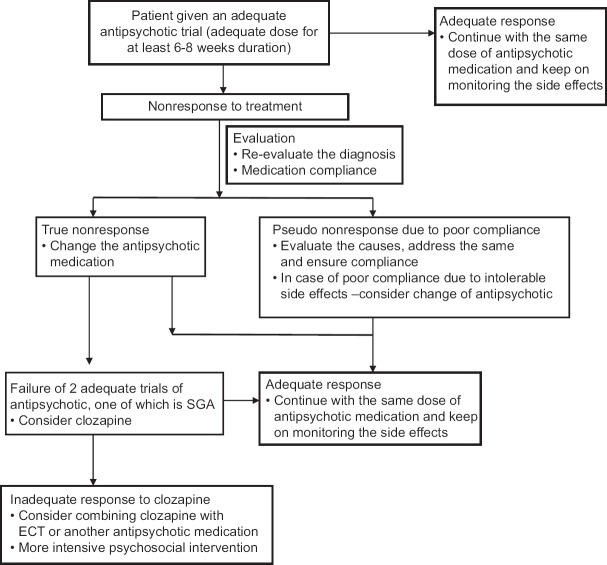

Nonresponse to treatment

As in adult patients, if a patient fails to respond to particular antipsychotic medication, compliance with medication needs to be evaluated, before considering a change in the medication [Figure 2]. If noncompliance or poor compliance is cause of nonresponse, then appropriate measures must be taken to ensure compliance with medication. If a patient does not respond to the medication even after ensuring proper medication compliance and giving medications in adequate therapeutic doses for 6–8 weeks, then change in medication be considered. If the patient fails to respond to two consecutive adequate trials (at least one of which is an SGAM), then clozapine needs to be considered. At present, there is lack of evidence in terms of making recommendation for patients who fail to respond to clozapine. Based on the data from adults, ECT or combination of clozapine with another antipsychotic medication may be considered. However, the use of combination of two antipsychotic medications must be done, after explaining the patient and family members about lack of evidence for the same and possibility of risk of higher side effects.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of patient with non-response to antipsychotic medications

Relapse prevention

Majority of the patients with schizophrenia require long-term treatment as there is high risk of relapse of symptoms with discontinuation of antipsychotics. In fact, compared to adults, higher proportion of children and adolescents with schizophrenia have chronic impairment, even while receiving continuous treatment. Patients who respond to treatment must be monitored from time to time to evaluate the course of the symptoms, side effect profile, psychosocial functioning, and medication adherence. During the stabilization phase, ideally, the same dose used during the acute phase must be continued. However, during the stable phase, minimum effective dose be used to minimize the risk of side effects. However, it is to be remembered that any change in the doses must be done slowly with close monitoring of symptoms.

Adjunctive medications

Although as a class of medications, antipsychotic agents remain the primary agents for management of schizophrenia in children and adolescents, management may involve use of adjunctive treatments such as with benzodiazepines (for anxiety, insomnia, akathisia, agitation, and catatonia), antiparkinsonian medications (for management of EPSs), antidepressants (for depression), and mood stabilizers (instability of mood and aggression). However, there is lack of data on use of these agents as adjuvant medications in children and adolescent with schizophrenia. Hence, if these have to be used, these may be used with proper rationale and for shortest possible duration after explaining the patient and/or the family members about the side effect profile and lack of supportive evidence. Prophylactic use of anticholinergics is not recommended; however, these can be given if patient develops EPSs in the lowest possible doses and for the shortest possible time. Prophylactic use of anticholinergic agents may be considered in patient with a past history of acute dystonias and those who are at risk of developing acute dystonia.

Electroconvulsive therapy

There is limited evidence for the use of ECT in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. Data from India suggest that among adolescents, ECT is most commonly used in patients with schizophrenia, mainly for catatonic symptoms, and found to be effective.[11,12] Various treatment guidelines including Indian Psychiatric Society Guidelines for the management of schizophrenia recommend use of ECT among adult patients with schizophrenia for catatonia, affective symptoms, need for rapid control of symptoms, presence of suicidal behavior endangering life of the patient, presence of severe agitation or violence which puts the life of others at risk, refusal to eat which puts the life of patient at risk, history of good response in the past, patients not responding to adequate trial of an antipsychotic medication, and augmentation of partial response to antipsychotic medication. Practice parameters of AACAP recommend that clinician must evaluate the risk and benefit of use of ECT against the risk of morbidity associated with the disorder and must consider the attitudes of the patient and the family and availability of the alternative treatment options before considering ECT in adolescents. In the Indian context, too, ECT may be considered with similar evaluation of risk and benefits for the patient. If ECT is considered, then proper informed consent must be obtained from the parents, after proper explanation of the possible cognitive side effects. ECT can be used in children and adolescents with catatonic symptoms, depression, and treatment-resistant schizophrenia. ECT if used in adolescents must also confer to the recommendations of the Mental Health Care Act, 2017.

Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial interventions are integral part of management of schizophrenia. Various psychosocial interventions which have been found to be useful in the management of schizophrenia in adult patients include family interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive remediation therapy (CRT), social skills training, individual supportive therapy, group therapy, vocational rehabilitation, case management, and use of community mental health teams and of crisis resolution teams. Occasional studies have also evaluated CRT, CBT, and family intervention/psychoeducation in patients with EOS, and the available data suggest that CRT is useful in the management of EOS. Studies which have integrated the components of problem-solving, psychoeducation, and family intervention have also shown the beneficial effect of the same in improving the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.

There is ample evidence from India too, which suggests that family intervention, rehabilitation, and other modalities such as community programs, yoga, and cognitive remediation are also useful in adult patients with schizophrenia. Based on these data, it can be said that same psychosocial interventions, which have been effective in adults, may also be effective in children and adolescents with schizophrenia and their parents/family members. The basic steps in providing psychosocial intervention involve assessment of psychosocial factors involving the patient and the family. Based on the assessment and available resources, interventions need to be tailored to address the needs of patients and their parents/family members. Basic components of any kind of psychosocial intervention should include enhancing therapeutic alliance with the patient and the family, encouraging engagement of the patient and family members in the treatment, sharing information about various aspects of the illness, focusing on treatment adherence and healthy lifestyles, and offering emotional and practical support.

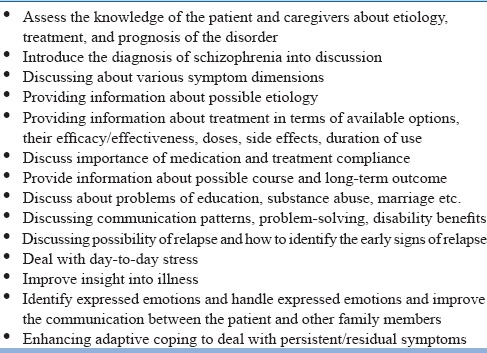

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation of both patient and family members is an integral part of management of schizophrenia. The basic component of psychoeducation includes providing information about the disorder and the available treatment options to the patient and the family [Table 10]. Effort must be made to provide simple and brief explanation about the nature of the illness, available treatments, possible side effects which may be encountered, and duration of treatment. Use of technical jargon should be kept to minimum and clinical information need to be provided in the language in which patient and the parents/caregivers are most comfortable. Further, there should be no information overload for the participants, rather information needs to be passed on in piece-meal fashion, tailored according to the acceptability of the patient and the family members. During psychoeducation, patient and family must be given enough opportunity to ask questions and clarify their doubts and misconceptions about the illness. Diagnosis of schizophrenia in children is often traumatic for the parents and to the sufferer too; hence, enough time must be given to the parents and the patient to accept this painful fact. Many a times, parents blame themselves or their partner for the illness in the child. Efforts must be made that no blame is attached to any one member of the family. An important aspect of psychoeducation is also to emphasize the need for regular intake of medication. Before starting every session, feedback of the earlier sessions must be taken, and future sessions must be tailored according to the need of the patients and their parents.

Table 10.

Basic components of psychoeducation

Family interventions

Family interventions, mainly in the psychoeducational format, can be useful in patients with schizophrenia. These interventions can be provided in the informal or unstructured form, structured format, individual or group format, and as specific strategy or as integrated psychosocial treatments combined with components of other psychosocial treatments. The basic emphasis of the family intervention programs should be on regular treatment contact with emphasis on the need for regular medication adherence and providing emotional and practical support. Family-based interventions also focus on communication patterns to address the issue of expressed emotions. The family intervention programs should be designed in such a way these meet the need of the patients and the family.

Advise for lifestyle and dietary modifications

All the patients must be informed about the side effect of weight gain with SGAMs, and they must be advised to change their lifestyle (regular physical exercise, abstinence from smoking, alcohol, and use of other illicit drugs) including diet to minimize the risk of metabolic side effects and ensuing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Supportive therapy

Supporting therapy in the form of empathetic listening of patient promotes therapeutic alliance. Other components of supportive therapy include support and advice, encouraging continued engagement, enhancing adaptive coping, treatment adherence, and healthy lifestyles. All the efforts focused on stress reduction are considered to be beneficial.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

CBT in psychosis aims to enhance the understanding about illness and improve insight into psychotic experiences, as well as to improve coping with residual psychotic symptoms. CBT also helps to reduce the distress associated with hallucinations and also reduces the degree of conviction and preoccupation with delusional belief. In general, confrontation and collusion are avoided and questions are framed in such a way that these help in gathering evidence in a non-judgmental manner. CBT also attempts to address the hopelessness and low mood, using similar principles as used for the management of depression.

Cognitive remediation therapy

CRT aims to improve the cognitive processes (i.e., attention, memory, executive function, and social cognition) by repeated practice of various cognitive tasks. Use of CRT among adolescents with schizophrenia has been shown to improve planning ability and cognitive flexibility.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation programs in children and adolescents should be guided by the needs of the patients and families. This should also take cultural issues into account. The rehabilitation strategies are also guided by the resources available at particular center and the resources of the family. Many patients return to their school after resolution of symptoms of acute phase. They must be emotionally supported and based on cognitive deficits; cognitive remedial measures may be provided.

Other psychosocial interventions

Other psychosocial interventions which have been shown to be of some benefit for adult patients with schizophrenia include home-based care, support groups for caregivers, community-based interventions, and yoga. However, there is a need for further systematic research to evaluate the efficacy of these modalities for children and adolescents.

PHASES OF ILLNESS/TREATMENT

As for other age groups, management of schizophrenia in children and adolescents is divided into three phases, i.e., acute phase, stabilization phase, and stable or maintenance phase. However, it is important to remember that compared to adults, relatively higher proportion of patients belonging to children and adolescents age group will present in the prodromal phase. These patients also require proper assessment and management.

PRODROMAL PHASE

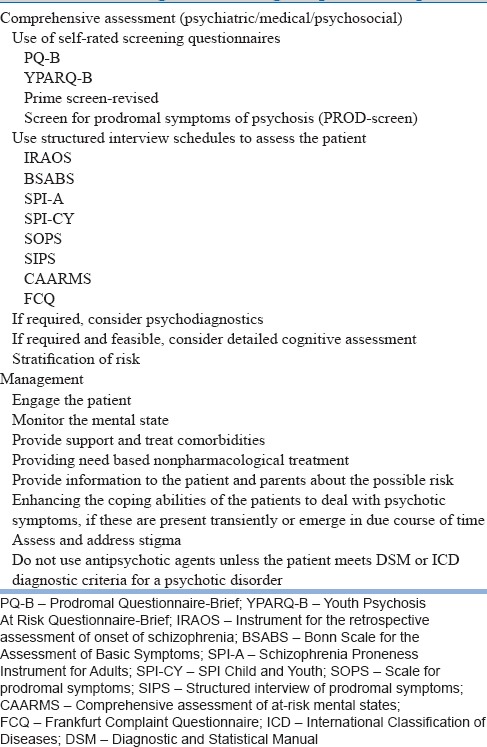

Patients in the prodromal phase may present with abnormalities in the domains of cognition, emotion, perception, communication, motivation, and sleep, rather than having clear psychotic symptoms. The important aspect of assessment of these patients is that, although all of them do not go on to develop psychotic disorders, compared to general population, these subjects have higher risk of conversion to florid schizophrenia and the nonspecific symptoms seen at this stage may have negative consequences on the cognitive, emotional, and social development of the person. Different studies suggest that the conversion rates range from 25% to 40%. Conversion to frank psychosis is predicted by family history of psychotic illness (especially in the first-degree relatives), longer duration of symptoms, higher severity of symptoms, reduced attention, higher degree of unusual thought content, suspiciousness/paranoia, high levels of depression, history of substance abuse (cannabis or amphetamines), recent deterioration in functioning, and presence of social impairment. The general recommendations for the management of this phase of illness include carrying out detailed assessment [Table 11] to document the symptoms in various domain and if possible stratification of the possible risk. In terms of management, based on the available evidence, it is not possible to make any specific recommendations at this stage. In terms of management, in general, use of antipsychotics is not recommended. There is some evidence to suggest possible beneficial effect of omega-3 fatty acid and antidepressants, depending on the symptom profile. It is suggested that in the prodromal phase, patient must be provided need-based nonpharmacological management. There is some evidence to suggest that psychosocial interventions such as CBT, cognitive therapy, and stress management can improve functioning and symptomatology during the prodromal phase, although the active components of these treatments are not well understood. Additional components of management include psychoeducation of patient and family, enhancing the coping abilities of the patients to deal with psychotic symptoms and addressing the issues of stigma.

Table 11.

Management during the prodromal phase

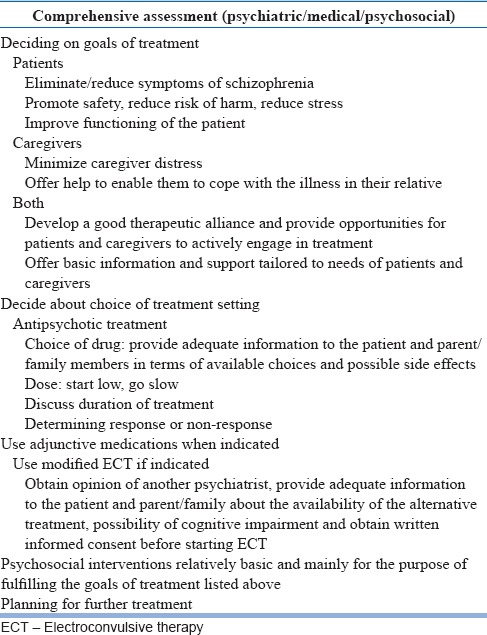

MANAGEMENT IN THE ACUTE PHASE OF TREATMENT

Patients in the acute phase of treatment usually present with florid psychotic symptoms in the form of hallucinations, language disturbances, disturbed thinking, delusions, and behavioral disturbances. They also have severe impairment in functioning in the form of difficulties in education or work. Children and adolescents experiencing acute phase can also be at risk of harming themselves or others. In view of florid symptoms, both patients and the family members are often under distress and struggle to accept the fact. The various aspects of management in the acute phase are included in Table 12.

Table 12.

Management in the acute phase

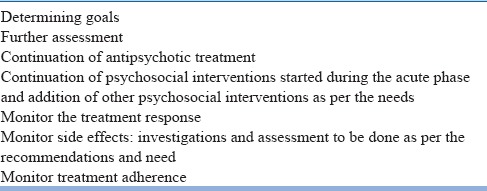

MANAGEMENT IN THE STABILIZATION PHASE

Stabilization phase of treatment commences with reduction or remission of symptoms seen in the acute phase, and this phase of treatment usually lasts for about 6–12 months. The components of management during the stabilization phase are shown in Table 13. The main objectives of this phase are further reduction in the symptoms and consolidation of remission and prevention of early relapses. The main goals of the treatment are continuous engagement of patient and family, providing emotional support, stress reduction, and enhancing adaptation to life. The objectives and goals of management can be achieved by continuing antipsychotic medications which led to remission or reduction in symptoms, monitoring treatment response and side effects, and continuing with the psychosocial interventions. Antipsychotic medications should preferably be continued at the same dose for the next 6–12 months. Psychosocial interventions are focused on maintaining treatment engagement and adherence, providing support to the patients and their families to come to terms with the illness and returning to normal walks of their life, addressing the new issues while going back to the usual life, and addressing issues related to stigma. Specific and elaborate psychosocial interventions can also be tried at this stage. Throughout the stabilization phase, patient treatment response, side effects, and medication adherence must be monitored.

Table 13.

Management in the stabilization phase

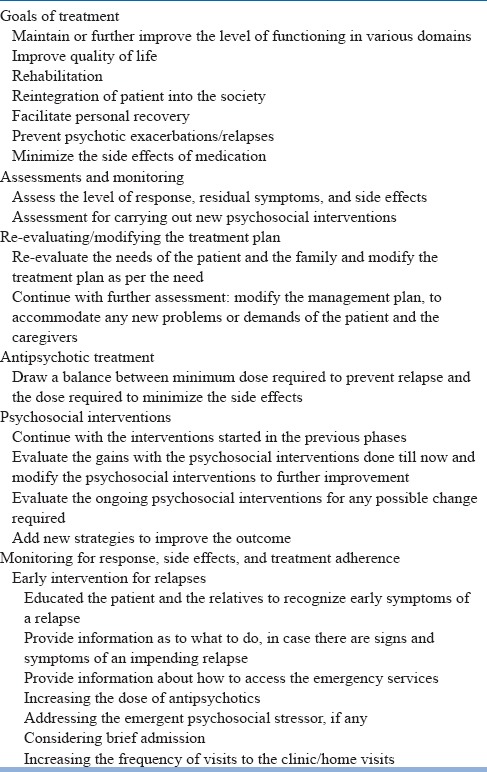

MANAGEMENT IN THE STABLE PHASE

During this phase of illness, symptoms are usually less severe and stable. The clinical picture may be predominated by negative symptoms along with problems in cognitive, social, and occupational functioning. This phase basically involves carrying forward the gains achieved in the acute and stabilization phase of management. The main aims of this phase of management are maintaining or improving level of functioning, preventing recurrences of symptoms, promoting psychological/personal recovery, and rehabilitation of the patient. The management plan should be reviewed from time to time and necessary changes are made to improve the overall outcome of the patient. This phase involves determining the goals, continuing with further assessments, continuing with antipsychotic medications, monitoring and minimizing the side effects, carrying forward the ongoing psychosocial interventions, and adding further psychosocial interventions for new emergent issues. Different components of this phase are shown in Table 14.

Table 14.

Management in the stable phase

At every follow-up, progress of the patient needs to be reviewed, and feedback must be taken from the family and other available sources. Progress in the education and occupation needs to be reviewed and rehabilitation need to be planned to reintegrate the patient into the society. Frequency of contact can be determined based on the clinical state, the distance of the hospital from the patient's home, available social support, and the type of treatment being administered. In general, the frequency of follow-up can be reduced in this phase of treatment to once in 2–3 months. However, more frequent follow-ups need to be considered if the patient is going through any crisis or there are psychosocial issues which require attention. More frequent follow-ups also need to be considered if the patient or family desires so. If there is emergence of new psychosocial issues, then these must be addressed.

The goals of management during the stable phase of treatment are to maintain or further improve the level of functioning in various domains, improve quality of life, and facilitate personal recovery. Psychotic exacerbations need to be effectively treated. Side effects of the medications should be monitored and managed effectively.

As time relapses, the nature of the illness, problems faced by the relatives, needs of the patient and the family, and previously determined targets are all expected to change. Regular contact, awareness, and monitoring are needed to detect these changes. Ongoing assessment is thus essential. It allows those modifications to be made in the treatment plan, which are required to accommodate any new problems or demands that may have arisen.

The dose of the antipsychotic to be used during this phase needs to be individualized. While determining the dose, balance has to be drawn in terms of minimum dose required to prevent relapse and the need to minimize the side effects. Reduction in the dose of antipsychotics may be considered in patients who are clinically stable and do not have any positive symptoms. If dose reduction is considered, then the doses need to be reduced gradually at the rate of about 20% every 6 months still a minimum effective dose is reached.

Reduction of dose/withdrawal of antipsychotic medication may be undertaken gradually while regularly monitoring signs and symptoms for evidence of potential relapse. Following withdrawal from antipsychotic medication, monitoring for signs and symptoms of potential relapse needs to continue for at least 2 years after the last acute episode. Any re-emergence of symptoms is to be immediately treated.

Duration of treatment will depend on multiple factors and this need to be individualized. In general, it is suggested that patients experiencing first-episode of schizophrenia need to receive maintenance treatment of 1–2 years duration. Patients who have history of multiple episodes or exacerbations need to receive maintenance treatment for 5 years or longer after the last episode. Patients with evidence of aggression or suicide attempts should receive treatment for longer period or lifelong. The usual indications for use of lifelong antipsychotic medications include history of multiple relapses while on treatment, evidence of relapses when the medications are tapered off, history of two episodes in the last 5 years, evidence of suicidal attempts, presence of residual psychotic symptom, family history of psychosis with poor outcome, and presence of comorbid substance dependence.

The psychosocial interventions started in the previous phases of treatment must be carried forward and modified as per the needs.

In a country like India, facilities for vocational rehabilitation are very limited. If the patient is willing to continue with his education or is continuing with his education, then efforts must be made to improve his outcome. If patient is not on any job, then further evaluation needs to be done to identify their suitability for particular job and they should be encouraged to search for a job for themselves. If the patient is already working and facing any problems at the workplace, then efforts must be made to address the same. If there is a need for rehabilitation, then culture-specific rehabilitation program need to be considered.

The management plan should be organized in such a way that any relapse of symptoms can be addressed at the earliest. Patients and relatives should be enabled to recognize early symptoms of a relapse and should be informed about the need for early intervention when there is evidence of an impending relapse. They need to be informed about how to access to treatment facilities such as emergency services or inpatient settings, in case patient is on the verge of a relapse. Crisis interventions in the form of brief admissions or frequent home visits need to be adopted, whenever feasible.

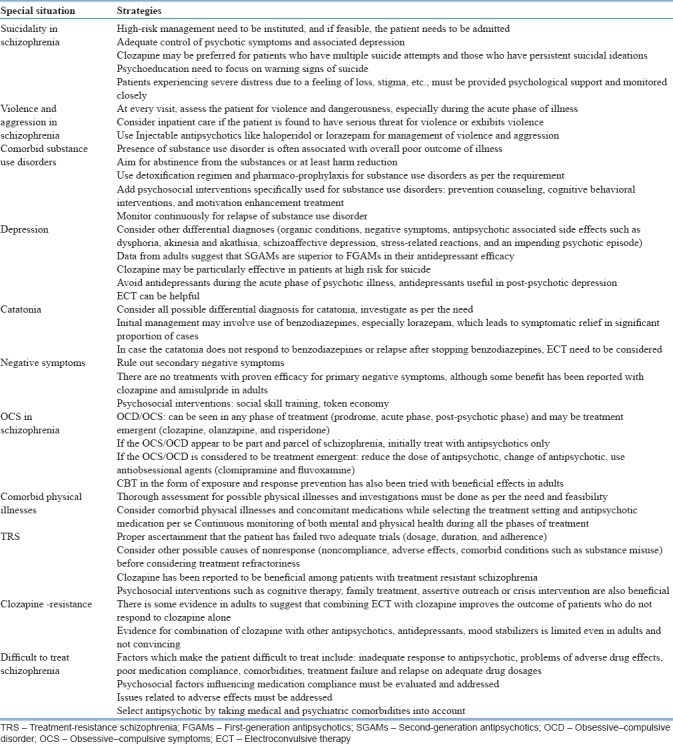

MANAGEMENT IN SPECIAL SITUATIONS

Management of schizophrenia often leads to certain clinical situations which often influence treatment decisions. Management of these situations is summarized in Table 15.

Table 15.

Issues related to special situations

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumra S, Oberstar JV, Sikich L, Findling RL, McClellan JM, Vinogradov S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:60–71. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraguas D, Correll CU, Merchán-Naranjo J, Rapado-Castro M, Parellada M, Moreno C, et al. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents with psychotic and bipolar spectrum disorders: Comprehensive review of prospective head-to-head and placebo-controlled comparisons. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:621–45. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarkar S, Grover S. Antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Pharmacol. 2013;45:439–46. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.117720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Datta SS, Kumar A, Wright SD, Furtado VA, Russell PS. Evidence base for using atypical antipsychotics for psychosis in adolescents. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:252–4. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A, Datta SS, Wright SD, Furtado VA, Russell PS. Atypical antipsychotics for psychosis in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD009582. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009582.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey RC, James AC, Shields GE. A systematic review and network meta-analysis to assess the relative efficacy of antipsychotics for the treatment of positive and negative symptoms in early-onset schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:27–39. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagsberg AK, Tarp S, Glintborg D, Stenstrøm AD, Fink-Jensen A, Correll CU, et al. Acute antipsychotic treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Findling RL, Johnson JL, McClellan J, Frazier JA, Vitiello B, Hamer RM, et al. Double-blind maintenance safety and effectiveness findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum (TEOSS) study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:583–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Lieberman JA, Bobo WV, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotic medications in early-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:845–53. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro-Fornieles J, Parellada M, Soutullo CA, Baeza I, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Graell M, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in child and adolescent first-episode psychosis: A longitudinal naturalistic approach. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:327–36. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grover S, Malhotra S, Varma S, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A, Mattoo SK, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in adolescents: A retrospective study from North India. J ECT. 2013;29:122–6. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31827e0d22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacob P, Gogi PK, Srinath S, Thirthalli J, Girimaji S, Seshadri S, et al. Review of electroconvulsive therapy practice from a tertiary child and adolescent psychiatry centre. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;12:95–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Addington J, Amminger GP, Barbato A. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:120–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ardizzone I, Nardecchia F, Marconi A, Carratelli TI, Ferrara M. Antipsychotic medication in adolescents suffering from schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2010;43:45–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischhacker WW, Simma AM. Managing the prodrome of schizophrenia. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012;212:125–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-25761-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasoff LI, Ahn K, Gochman P, Broadnax DD, Rapoport JL. Strong treatment response and high maintenance rates of clozapine in childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:428–35. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schimmelmann BG, Schmidt SJ, Carbon M, Correll CU. Treatment of adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders: In search of a rational, evidence-informed approach. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:219–30. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835dcc2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt SJ, Schultze-Lutter F, Schimmelmann BG, Maric NP, Salokangas RK, Riecher-Rössler A, et al. EPA guidance on the early intervention in clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:388–404. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ, Schimmelmann BG, Maric NP, Salokangas RK, et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:405–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sikich L, Frazier JA, McClellan J, Findling RL, Vitiello B, Ritz L, et al. Double-blind comparison of first- and second-generation antipsychotics in early-onset schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: Findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1420–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]