INTRODUCTION

Specific learning disorder (SLD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders affecting 3%–10% of children. Although many definitions have been proposed, there is no common consensus on the diagnostic criteria and definition of SLD.

NOSOLOGY

In the 1960s, LD emerged as a category as mentioned by Samuel Kirk. He defined dyslexia as a kind of “learning disability” and defined LD as “an unexpected difficulty in learning one or more of one instrumental school abilities.” As per Kirk, LD is a process issue which can affect language and academic performance of people of all ages which is caused by emotional disturbance, behavioral disturbance or cerebral dysfunction.[1] Bateman through his landmark observation, mentioned those with learning disorders have a significant discrepancy between their estimated intellectual potential and actual level of performance with or without neurological dysfunction which is not secondary to mental retardation, educational or cultural deprivation, severe emotional disturbance, or sensory loss.[2]

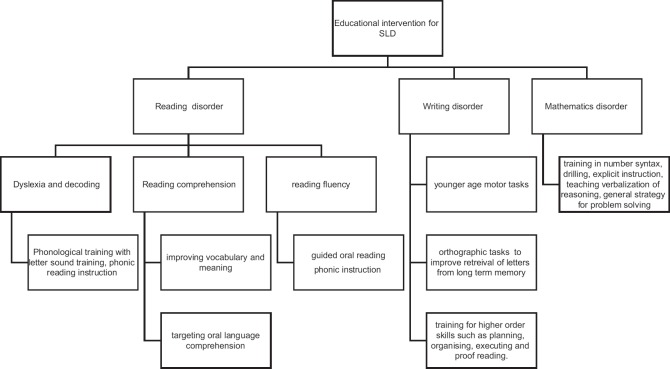

As curiosity and awareness progressed, various definitions have been proposed across the world. The two worldwide international diagnostic classifications-International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (5th Edition).[3,4] The difference between the two is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

The differences in criteria of diagnosis of specific learning disorder between Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorder 5 and International Classification of Diseases 10

The ICD 10 refers to Specific developmental disorders of scholastic skills:

Conceptually they are disorders of disturbance in the normal pattern of skill acquisition

Not simply a consequence of lack of neither opportunity to learn nor any acquired brain trauma or disease

Abnormalities in cognitive processing that derive from biological dysfunction

Clinically significant degree of impairment in specified scholastic skill. Severity can be judged by scholastic terms or developmental precursors (scholastic difficulties were preceded by developmental delays or deviance, most often in speech or language in preschool years) or qualitative abnormalities

Response– scholastic difficulties do not rapidly and readily remit with increased help at home/school

Impairment must be specific– not solely explained by mental retardation/lesser impairments general intelligence

Impairment must be developmental– early years of schooling and not acquired later in the educational process.

The impairments are characterized by

-

Specific reading disorder: Characterized by specific and significant impairment in the developmental of reading skills which are not accounted for mental age, visual acuity problems or inadequate schooling

- Child's reading performance should be significantly below the level expected based on age, general intelligence and school placement. Performance is best assessed by means of an individually administered standardized test of reading accuracy and reading comprehension

- Early stages:Difficulty in reciting the alphabets, in giving the correct names of letters, in giving the simple rhymes for words and in analyzing or categorizing (despite normal auditory acuity)

- Later stages: Errors in oral reading skills

- Omissions, substitutions, distortions, or additions or words or parts of words

- Slow reading rate

- False starts, long hesitations or “loss of place” in text and inaccurate phrasing

- Reversals of words in sentences or of letters within words.

-

Deficits in reading comprehension:

- Inability to recall facts read

- Inability to draw conclusions or inferences from material read

- Use of general knowledge as background information rather than of information from a story to answer questions about a story read.

-

Specific spelling disorder: Characterized by specific and significant impairment in the developmental of spelling skills in the absence of a history of specific reading disorder which is not solely accounted for by low mental age, visual acuity problems or inadequate schooling

- Child's spelling performance should be significantly below the level expected based on age, general intelligence and school placement

- Performance is best assessed by means of an individually administered standardized test of spelling.

-

Specific disorder of arithmetic skills: Characterized by specific impairment in arithmetic skills which is not solely explicable because of general retardation or of grossly inadequate schooling

- Child's arithmetical performance should be significantly below the level expected on the basis of age, general intelligence and school placement. Performance is best assessed by means of an individually administered standardized test of arithmetic

- Failure to understand the concepts underlying arithmetical operations

- Lack of understanding of mathematical terms or signs

- Failure to recognize numerical symbols

- Difficulty in understanding which numbers are relevant to the arithmetical manipulations

- Difficulty in properly aligning numbers or in understanding which numbers are relevant arithmetic/inserting decimal points/symbols during calculations; poor spatial organization of arithmetical calculations; and inability to learn multiplication tables satisfactorily.

Mixed disorder of scholastic skills: Characterized ill-defined/inadequately conceptualised but necessary residual category of disorders in which both arithmetical and reading or spelling skills are significantly impaired but in which the disorder is not solely explicable in terms of general mental retardation or inadequate schooling

Other developmental disorders of scholastic skills: Developmental expressive writing disorder

Developmental disorder of scholastic skills: Unspecified disorders in which significant disability of learning that cannot be solely accounted for by mental retardation, visual acuity, or inadequate schooling

Includes: Knowledge acquisition disability NOS; LD NOS; learning disorder NOS.

DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL OF MENTAL DISORDERS 5TH EDITION

Term used “SLD”

-

Difficulties learning and using academic skills indicated by presence of one of the following that have persisted for at least 6 months, despite the provision of interventions that target those difficulties:

- Slow/inaccurate/effortful reading

- Difficulty understanding what has been read

- Difficulty in spelling

- Difficulty in written expression

- Difficulty in mastering number sense, number facts, calculations

- Difficulty with Math reasoning.

The affected academic skills are substantially and quantifiably below those expected for the individual's chronological age (at least 1.5 standard deviation below the population mean for age). Significant interference with academic or occupational performance or with activities of daily living is overserved. LD is confirmed by means of standardized achievement measures and comprehensive clinical assessment. Learning difficulties start at school years. However, they may not manifest till demands in academics exceed individual capacities.

Note: Diagnostic criteria to be met using

History

School reports

Psycho educational reports.

Mention the academic domains and sub skills impairment:

With impairment in reading:

Word reading accuracy

Reading rate accuracy/fluency

Reading accuracy.

With impairment in written expression:

Spelling accuracy

Grammar and punctuation accuracy

Clarity or organization of written expression.

With impairment in mathematics:

Number sense

Memorization of arithmetic facts

Accurate or fluent calculation

Accurate Math reasoning.

Specify current severity:

Mild: some difficulties in one or two academic domains; mild enough and can be compensated or functions well with accommodations/support service especially during school years

Moderate: Marked difficulties one or more academic skills; unlikely to become proficient without intensive teaching during school years, accommodations/supportive services at school/home to complete activities accurately

Severe: Severe difficulties, several academic skills; unlikely to become proficient without ongoing intensive teaching for most of the school years, despite accommodations/supportive services at school/home may not complete activities accurately.

THE DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL OF MENTAL DISORDERS 5TH EDITION CHANGES

DSM 5 criteria for learning disorderare an overarching category and follow a spectral approach. Twin and family studies revealed significant genetic and environmental overlap amongst – reading, math and written expression disorders. Hence, the “Lumping approach” is followed than the “Splitting approach”. It reduces the challenges associated with defining the subtype of LD. For e.g., Test scores differ across academic domains/tests; with some falling just below clinical threshold.

Intelligence quotient (IQ) achievement gap is no longer mentioned

Intellectual assessment will be required only in cases where intellectual disability is suspected

The focus is on early access to intervention and less on assessment for diagnosis and for this psychoeducation of parents and consultation with parents and teachers required

Inclusion of effect of Intervention and symptom persistence is yet another change with have practical challenges.

INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES 11

The potential changes in ICD 11 include a change in the terminology to “Developmental learning disorder”. This includes– with impairment in reading, written expression, mathematics and with other impairment of learning. Conceptually, the criterion continues to follow the discrepancy in achievement according to the chronological age and level of intellectual functioning.

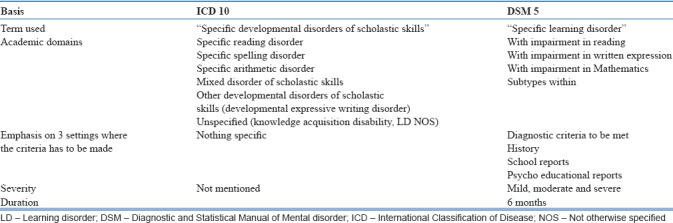

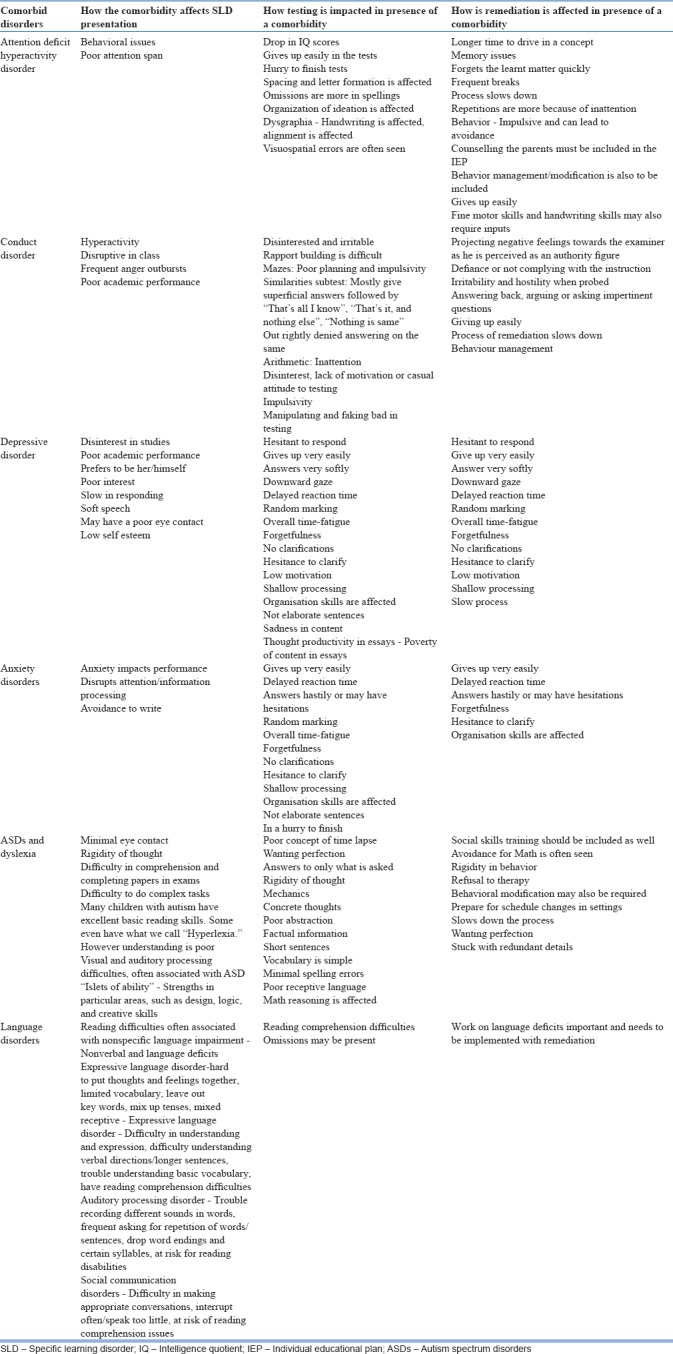

Prevalence and comorbidity

As per the Sahoo et al., 2015, prevalence of learning disorder ranges from 2% to 10%.[5] The prevalence of learning disorders in India is 5%–17% of the children.[6] Male to female ratio for learning disorder is 2.3:1. There is high comorbidity as depicted in Table 2 and has impact on the presentation and intervention of the disorder [Table 3].

Table 2.

Comorbidity with specific learning disorder

Table 3.

Comorbidity with specific learning disorder and the impact

ASSESSMENT

Assessment of children includes a detailed clinical evaluation followed by standard psychometric assessments of child's cognitive abilities and academic skills.

Clinical evaluation

Children with SLD are either brought by their parents as self-referred or by referral from the school. Children with learning difficulties are often labelled as “lazy” or “stupid” or as being “trouble makers “if they have comorbid behavioral symptoms. They are often compared with others who perform well in academics and face punitive experiences in the home as well as school contexts. The clinical presentation is quite variable with some children presenting primarily with complaints of poor academic performance whereas others can present with symptoms secondary to the poor academic performance which may include school refusal, oppositional behavior, aggression, poor motivation for studies, low self-esteem, sadness of mood, crying spells, changes in sleep and appetite, excessive engagement in extracurricular activities, somatic complaints (pain symptoms, fatigue), dissociative symptoms (pseudo seizures, dissociative sensory loss, dissociative amnesia etc.).

Academic difficulties include writing slowly, not completing classwork and homework, poor handwriting, omission of long answer questions, inability to completewriting in time, spelling mistakes, reading slowly, reading word by word, replacing difficult words with words of similar pronunciation, reading without punctuation, mistakes while doing arithmetic etc.

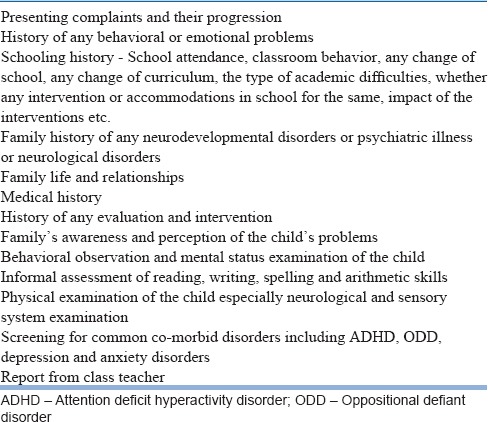

Prior to psychological testing, the psychiatrist should obtain a detailed history from parents and child followed by examination of the child. The clinical evaluation should be structured to include the components listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Outline for clinical evaluation

Psychometric testing

Psychometric testing helps in confirmation of diagnosis and in planning the intervention. The psychometric testing usually includes testing for cognitive abilities and testing for academic abilities. Assessment of the child's level of Intelligence by measuring IQ can be done using Standardized IQ tests. The tests that can be used include Binet–Kamat Test, Malin's Intelligence Scale for Indian Children (MISIC), Wechsler's Intelligence Scale for Children-4th Edition etc. These have differing advantages (refer to table in article on Intellectual Disabilities) MISIC will provide Performance IQ, Verbal subscale IQ and Full-scale IQ. In children with SLD, there is a discrepancy between verbal and performance IQs with the performance IQ usually being higher. Another pattern named “ACID-profile” has been described where children may score low on subtests of Arithmetic, Coding, Information and Digit-span. WISC IV often reveals weaknesses in verbal comprehension, working memory, and processing speed.[14]

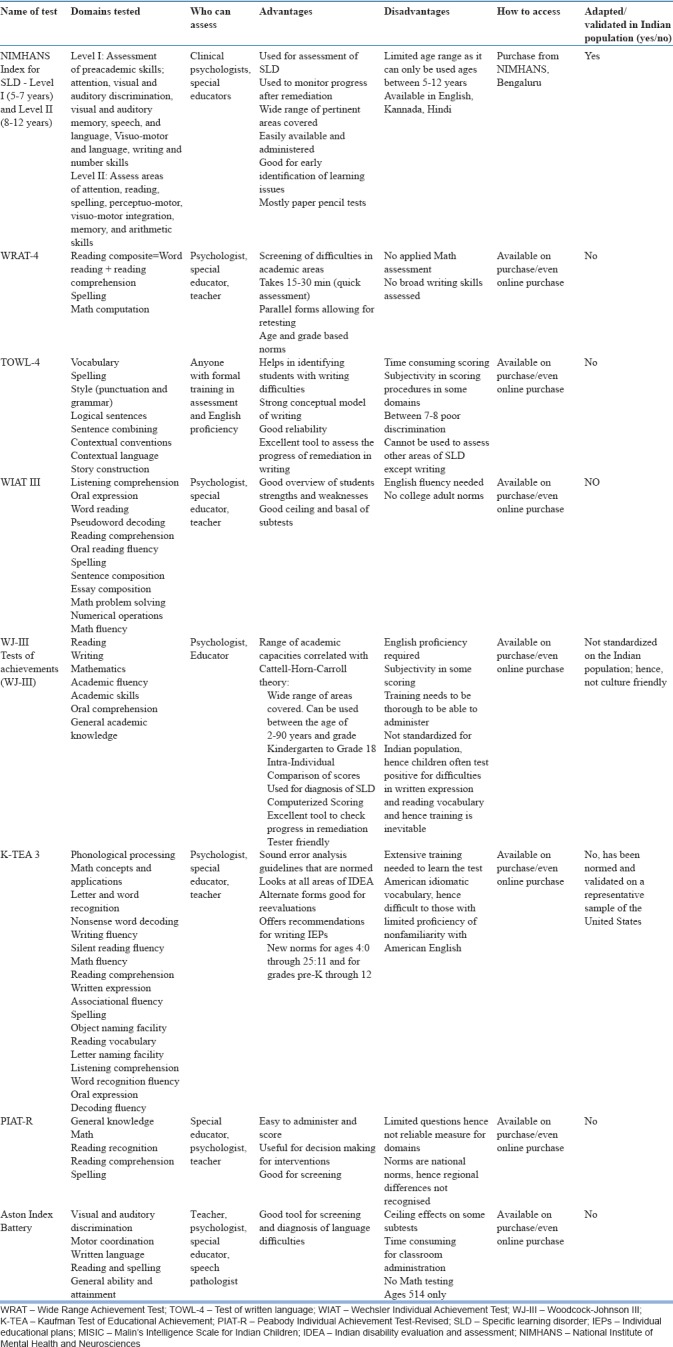

After assessment of IQ, tests to evaluate academic abilities need to be administered. There are several tests as depicted in Table 5, whichare useful in the evaluation of academic abilities. These include NIMHANS Index for SLD, Wide Range Achievement Test, Test of written language-4, Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Woodcock-Johnson III/IV Tests of achievements (WJ-III), Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement, Peabody Individual Achievement Test-Revised, Aston Index Battery.

Table 5.

Various tests of achievement

INDIAN TESTS

NIMHANS Index for SLD is the most commonly used battery in the Indian context. Reliability and validity of this tool has been established.[15] It includes the tests in two levels. Level I is for 5–7 years age group and Level II for 8–12 years. The tests in

Tests in Level I are:

Visuo-motor skills (copying of three geometrical figures)

Writing of capital letters

Writing of small letters

Writing of an alphabet preceding a specified alphabet

Writing of an alphabet succeeding the specified alphabet

Writing of numbers serially

Writing of numbers preceding a specified number

Writing of numbers succeeding a specified number

Color cancellation test

Visual discrimination

Visual memory

Auditory discrimination

Auditory memory

Speech/language (both receptive and expressive).

The tests in Level II are:

Number cancellation

Reading of English passages

Spelling of English words (including Schonell's 15 words list)

Reading comprehension of English passages

Arithmetic subtest

Bender Gestalt test for visuo-spatial abilities.

Most of the definitions of SLD whether exclusionary or inclusionary refer to terms such as adequate intelligence, appropriate instruction and socio-cultural factors which are difficult to standardize in a pluralistic society as that of India. Formulating indigenous assessment tools for processing deficits, intelligence testing and proficiency in reading, writing and mathematics; in the several hundred languages spoken in India will be a gigantic task. And perhaps we will never be able to achieve the same. These complex issues are further compounded by a near total lack of awareness of teachers, differences in age of school enrolment, pre-literacy, quality of teaching in schools, and learning environment and support at home.[16,17]

iBall is a test under construction at National Brain Research Centre (NBRC) with support from Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. It is to be available early 2019 and is in multiple languages of India

Curriculum–based assessments can also be used to assess the academic skills in children. These tests as the name suggests are based on the child's curriculum and therefore not as wide and comprehensive as other tests of achievement. Grade Level Assessment Device (GLAD) for children with learning problems in schools has been developed by the National Institute for Empowerment of persons with Intellectual Disability.[18] GLAD can be used from the age of 6 years for grades I to IV. It is available in English, Hindi and includes mathematics. Another “Curriculum Based Test for Educational Evaluation of Learning Disability” is authored by Ms. Rukhshana Sholapurwala.[19]

DIAGNOSIS

A child with LD is one who does poorly in academics because of impaired ability in learning the academic skills of reading, writing, arithmetic, and spelling. To diagnose SLD, such impairment should not be because of Intellectual Disability, subnormal intelligence, neurological disorders, visual/hearing acuity problems or inadequate schooling, but represent a specific and circumscribed type of dysfunction in cognitive processing.

In contrast to general learning difficulties that cut across different domains (academic and nonacademic), children with specific learning difficulties possess average to above-average levels of intelligence across many domains of functioning, but have specific deficits within a narrow range of academic skills. In other words, this label is considered only for children whose performance is significantly below that expected (usually 2 classes below) based on their general capacity to learn. Thus, the concept of unexpected academic difficulty is central to the definition of SLD. The extent and severity of difficulties may vary from child to child. In fact, most children with SLD have only milder forms of disability.

Using the Rutter's multi-axial diagnosis will provide a better understanding about the child's problems and in setting up an effective treatment plan.

For example:

Axis 1: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Axis 2: Specific Developmental Disorder of Scholastic Skills

Axis 3: Average intellectual functioning

Axis 4: Nil

Axis 5: Punitive parenting.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Prior to diagnosis of SLD, the evaluation should rule out the following conditions as primary causes of poor academic performance:

Borderline intelligence

Intellectual disability

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Autism spectrum disorder

School absenteeism due to general medical conditions

Psychiatric disorders including mood disorders, anxietydisorders, and psychosis

Discrepancy between mother tongue and medium of schooling

Inadequate facilities for schooling

First-generation learners with poor social support

Hearing impairment

Visual impairment

Neurological disorders, for example, myopathy and writer's cramp.

Early identification of children at-risk

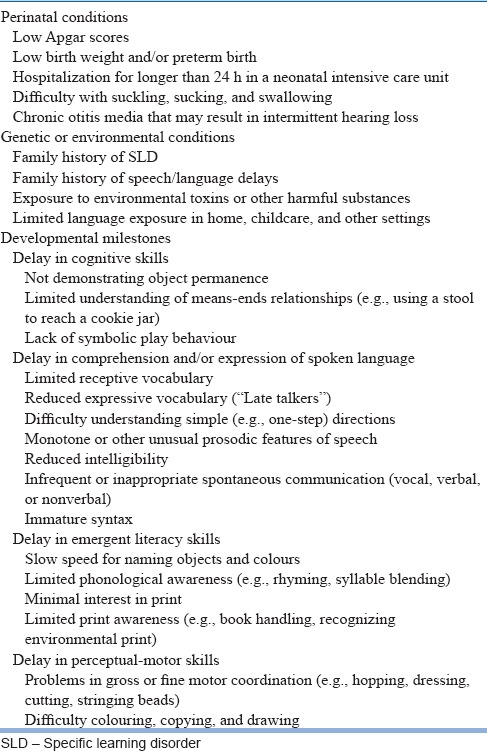

It is important to identify children at-risk for SLD. The National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities, USA suggests that risk indicators must be checked in any screening evaluation. Table 6 lists the Risk indicators that must be included in screening for at-risk children.

Table 6.

Risk indicators for specific learning disorder

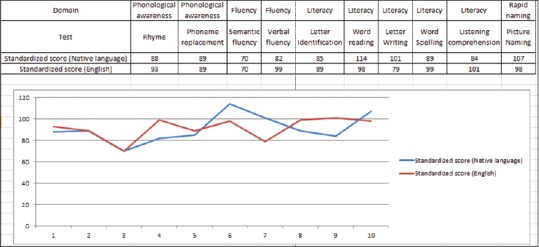

There are screening tools available to assist in early identification. One of the recent tools that has been used in India is Specific Learning Disability–Screening Questionnaire. This can be used in the school setting by teachers.[20] Recently a Dyslexia Assessment for Languages of India (DALI)[21] a comprehensive screening and assessment battery for children with or at risk for dyslexia, between the classes of 1–5 has been developed by Dr. Nandini Singh and team at NBRC with support from Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. DALI has two screening tools: Junior Screening Tool for classes (1–2) (5–7 years). And middle screening tool for classes (3–5) (8–10 years). In addition, there are 8 Assessment Batteries and includes testing in English and the mother tongue. This helps in separating between dyslexia and language difficulties. A sample of report is below [Figure 1]. DALI has been standardized and validated across four languages (Hindi, Marathi, Kannada and English) across schools at five centres (4840 children from classes 1–5). Work is ongoing to extend till grade X and include mathematics. The number of languages will now cover Bengalee, Urdu and Tamil.

Figure 1.

An example of a report of DALI

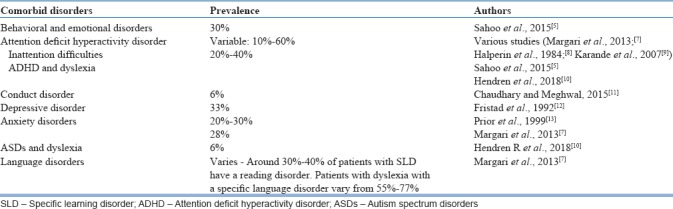

MANAGEMENT

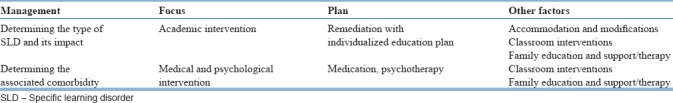

The psychiatrist is oftenthe primary contact person who suspects, assesses, screens for SLD and evaluates for co-morbidities and treats them. The psychiatrist can also suggest simple handy remediation techniques outlined below. Additionally, in ideal circumstances a multi-disciplinary team (psychologist, special educator occupational therapist, language speech therapist and pediatrician) would be useful in the holistic evaluation and management of these disorders. Management implies helping with the core deficits of the disorder, its negative impact on child and family and treating the associated comorbidities. An overview of management of Learning disorders has been discussed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Overview of management

Management of core deficits of disorder:

Interventions can be classified as

Accommodations which facilitate the student to access the educational material. This decreases the burden and stress on the child. They include larger size pen/pencils, use of grippers, special papers which provide tactile feedback, use of spell checkers, audio books, and technological devices. The later may include voice recognition devices, touchpad devices, and calculators. Individualizing assessments in terms of time, length and allowance for breaks can be planned. The child may be provided with special services in resource room while being mainstreamed

Modification is where the task and academic expectations from child are changed. Change in the delivery, content, or instructional level of subject matter or tests are implemented. This could include oral assignments, writing in short, may focus either on content or spelling, not having to read aloud and extra time, learning lower level of mathematics or dropping a language

Remedial Education is being a process to help the child acquire age appropriate skillsin all his foundation areas which are required forattaining knowledge at his pace and potential. Interventions need to be systematic, well-structured and multi-sensory. They should include direct teaching, learning and time for consolidation. Repeated revision is to be factored in as attention is variable. It should be child centric, strategy taught for learning the content, focus on strengthening the basics Research hasshown to be effective, the intervention should be intensive 2–3 times a week and either at individual level or in a small group (1–2), using an explicit and systematic instruction in phonological awareness and decoding skills. Following improvement, 50% children maintain gains for 1–2 years. This is more so when intervention is early (6–8 years). Usually fluency improves rather than comprehension. Children who improve continue to show further improvement over next few years. Changes in brain occur with remediation[22] and which reflect plasticity of the brain.

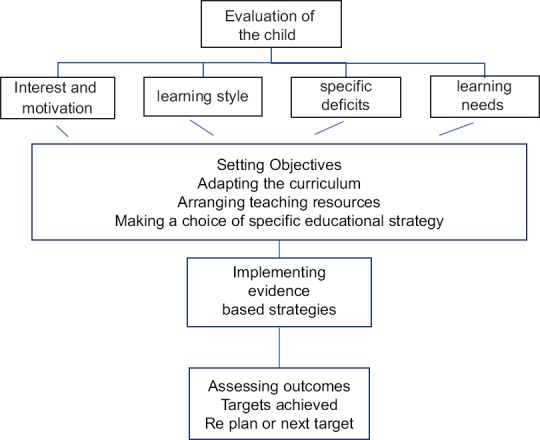

Depending on the type and severity of the problem, an individual educational plan is made for the child. Flowchart for the process of individual educational plan is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for the process of individual educational plan

The intervention planned is determined by the age/grade of child and the severity and type of deficits sand strengths. Usually it is 2–3 times a week for 3–4 years. In early years, developing language skills and basic skills of reading, writing and mathematics are the area of focus. In middle school besides basic skills, children need to learn concepts, critical thinking and problem solving. In secondary school accommodations and modifications to help the child to cope become more prominent. Whilst educational interventions are on the plan must also include components for the socio emotional development of child. Choice of techniques depends on the areas affected [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Flowchart for interventions for specific learning disorders

SPECIFIC EDUCATIONAL STRATEGIES

Reading

In problems of decoding (usually referred to as dyslexia), phonological awareness needs to be increased. That is the ability and understanding to manipulate the sound structure of words. Emphasis is paid on phonemes, which is the smallest unit of speech, e.g., k in kit, b in bat. Phonemic awareness includes ability to hear and manipulate individual phonemes.

Phonemic awareness includes activities such as

Isolation, the training is in recognizing the individual sounds in words.(tell me the first sound in the letter hat)

Phoneme identity: The ability to distinguish the common sound in differing words (tell me the soundthat is same in pod and pan)

Phonemic substitution: Replacing one phoneme for another to create a new word (cat-mat, bad-bat)

Oral segmenting is being able to break the word into different sounds (ban b/a/n)

Oral blending is joining the sounds to form words (c/a/n is can).

Besides phonemic awareness, letter sound knowledge is remediated. Phonics instruction works on letter sound correspondence and spelling patterns which helps in reading. To be effective it should be in conjunction with word recognition and reading books. Repeated oral reading practice may help in improving fluency. Reading comprehension skills are linked to larger language comprehension skills and needs to be developed.[23]

Writing

Writing is more complex skill than reading and it may co-occur with reading disorder or independently. Eye hand coordination and ability to segment phonemes is essential.[24] The basic motor functioning is enhanced using hand exercises such as working with clay, beading and finger tapping. To improve spelling, phonics instruction and teaching of letter writing is used (following numbered arrow cues, hiding letter and visualizing writing letter, utilizing the numbered cues to write letter and finally checking the letter as compared to sample). To master automaticity the ability to retrieve letters, educational games and activities are useful. To target higher order skills of writing an essay, which involve planning, organizing, reviewing and editing skills, practice using concept maps and different aids and strategies are employed. Writing clubs and self-regulated strategy development have shown to be useful.[25]

Mathematics

Number sense is deficient in children with dyscalculia. Educational strategies include practicing number syntax (linking numbers to related digits; e.g., 1234, one corresponds to thousand, two to hundreds, three to tens and 4 to units). Repeated additions help in internalizing the number line. Drill and practice also help to remember number facts. Verbalization of arithmetic concepts, procedures and operation is helpful as is explicit instruction.[26]

Many remedial programs are developed, they usually work with children with reading and writing difficulties (Sonday system) or with children with mathematic difficulties (Number race, Graphogame).[27]

SPECIAL AREAS

Children with poor language skills

Many children who are first generation learners or have poor exposure to English language would have added difficulties in all aspects of academic achievement. These children are often overidentified as suffering from SLDs. Sometimes both may occur. However, for these children, besides the specific intervention, English enrichment program would be very useful.

Use of technology

Assistive devices help children overcome obstacles and save time. Technological tools can vary from voice recognition programs (users dictate ideas and watch them appear on their computer screens) recording devices, word processors, concept mapping tools, smart pens and educational apps. There issoftware specially designed for children with SLD.(Grahphogame). Use of universal design allows easy access for children with SLD, whilst a child who has severe difficulties may use a computer to write, it would be helpful to encourage the child to try and write as brain activity is better with this. Similarly, learning basic concepts of maths are useful for daily life.

Choice of curriculum

In India, there are various boards running different curriculum, such as State Boards, Indian Councilof secondary education, Central Board of secondary education, National Open school and international ones such as International baccalaureate. Each of these boards have varying educational standards, teaching learning methods, choice of subjects and help children with disability. Based on these factors, parents and teachers may consider shifting of curriculum.

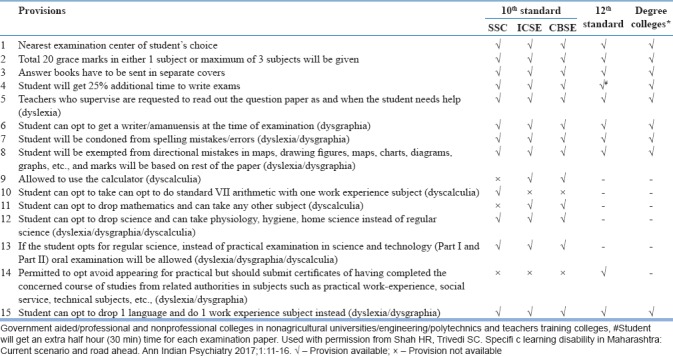

In first generation learners, low socio-economic status may add to the disorder especially when the child is not being educated in the mother tongue. SLD has shown to have similar universal neuropsychological features across alphabetic (English, Hindi) and logographic (Chinese) orthographies. Depending on the regularity of the language the difficulty would vary. Hindi is more consistent than English, that is alphabets and sound match more consistently in Hindi than English. However, changing the medium of instruction should only be attempted in the early years. Academic provisions are given to children ith Learning disorder as described in Table 8.[6]

Table 8.

Various provisions for specific learning disorder an example from Maharashtra

Mitigating the impact of specific learning disorder

Psychoeducation of the family and explaining the disorder to the child would be necessary. Family counselling may also be required to combat the negative attitudes and behavior.[28] Low self-esteemwhich is a common finding will require specific intervention.[29] Protective factors that foster resilience are useful and include self-advocacy tools, identifying strengths, and improving social connections.[10]

Managing comorbidity

Comorbidity is a rule rather than an exception. Some may be the presenting illness (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]/autism spectrum disorder), some may be a consequence (depression) and some may be blended with the disorder (anxiety and behavioral symptoms) However, research on treating comorbidities is limited as most studies use this as exclusion criteria.

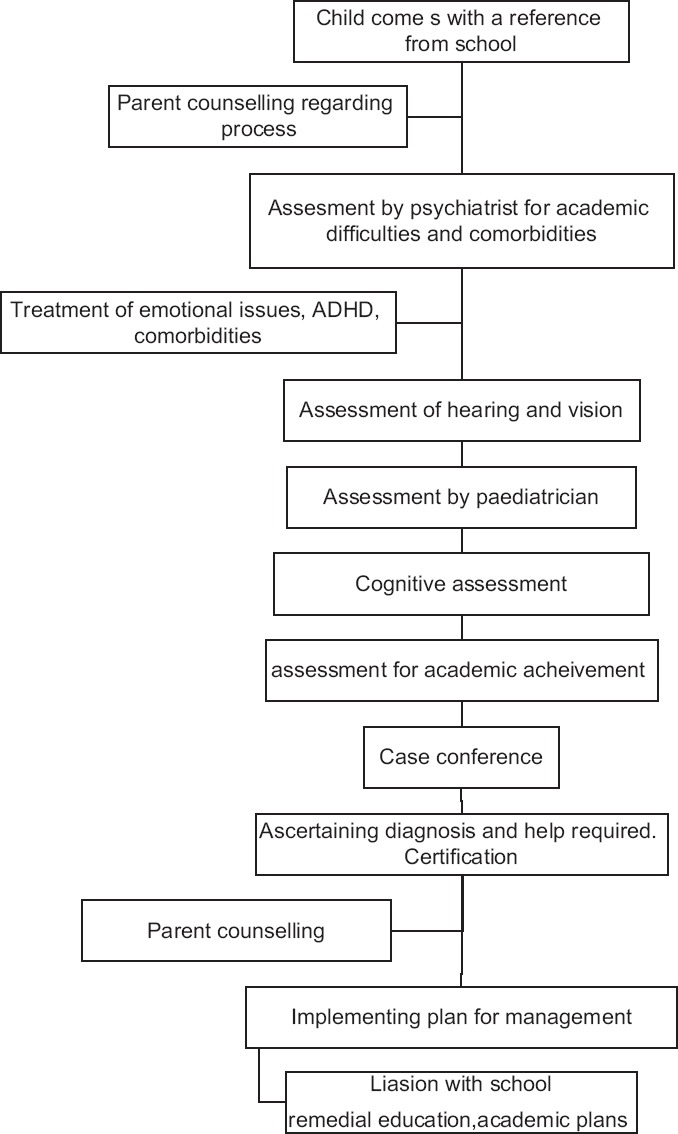

ADHD is a frequently occurring disorder and requires treatment even before assessing as it interferes with the results. Treatment of both disorders is required simultaneously though it may not lead to additive effect. Pharmacotherapy for ADHD has had a varying effect on the reading disability.[10] Cognitive behavior therapy and mindfulness meditation is shown to improve the emotional health with the latter also improving attention.[10] Anxiety, depression, disruptivebehaviordisorder, impulsivebehavior, autism, conductdisorders and other SLD also require the appropriate intervention. Flowchart of an overview of assessment and management is shown in the Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart for overall process in assessment and management

PREVENTION AND PREDICTION

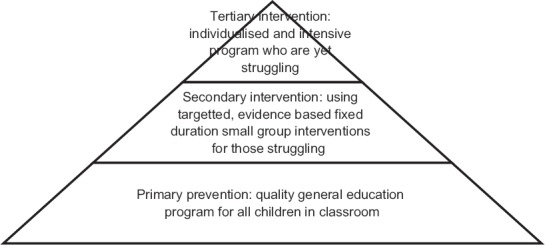

Cognitive skills that predict literacy are letter sound knowledge and phoneme awareness. Whilst as a group these may be differentiating factors, translating this at the individual level to predict is not easy.[30] A well-trained teacher would be able to identify children who are struggling. This could be supported with checklists. In the USA, response to intervention is used both for prevention, treatment and detection. This model which is depicted in Figure 5, would start treatment before identification or failure sets in. This could be encouraged in schools and may integrate help from Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. The early intervention for at risk children for dyslexia could be phonological skill training.

Figure 5.

The response to intervention model

Besides phonological processes, communication impairment and deficits in naming speed (measured by RAN) are predictive of future SLD. Language impairments are a risk for reading comprehension difficulties in the future. Poor readers often come from large families and poor reading skills in parents. Better outcomes for decoding are seen when parents teach print concepts and for comprehension when parents share reading with offspring. With intervention, over half to three quarters children improve. This early intervention also prevents complication of developing poor reading fluency and comprehension.[22]

LAW AND SPECIFIC LEARNING DISORDER

SLD is one of the bench mark disabilities encompassed in the Rights of Persons With Disability Act, 2016 and which ensures the following:[31]

Government and local authorities are required to ensure that children with benchmark disabilities will have access to free education in an appropriate environment (till 18 years of age). In SLD, it has been difficult to quantify the disability

Government institutions of higher education and other higher education institutions receiving aid from the Government shall reserve not <5% seats for persons with benchmark disabilities (which includes specific LD) and upper age relaxation of 5 years for admission in institutions of higher education

In Government establishment, not <4% of the total number of vacancies in the cadre strength in each group of posts is meant to be filled with persons with benchmark disabilities of which, 1 percent each shall be reserved for persons with particular benchmark disabilities and one of which is specific LD.

ROLE OF PSYCHIATRIST IN SCHOOLS REGARDING SPECIFIC LEARNING DISORDER

The role of the psychiatrist includes the following:

Enlist the engagement of school by making them empathetic to needs of child, advocate for child in school

Psychoeducation the teachers

Facilitate screening in school

Create agreement with goals acceptable to all stakeholders

Mobilizing the school system to help the child and empowering them to do so

Raising awareness about social, emotional, behavioral symptoms associated with SLD. Training teachers to identify, refer and use classroom management strategies

Refer, introduce for further resources

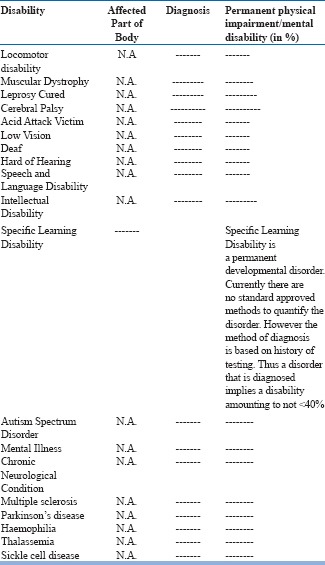

Certification of the disability. A format is supplied by RWPD rules[32] and depicted below (the RPWD identifies the paediatrician as a certifying physician. The Indian Psychiatry has made a representation to the concerned ministry for the inclusion of a psychiatrist).

FORM-VII

Disability Certificate

Certificate No. Date:-

This is to certify that I have carefully examined

Shri/Smt./Kum.

Date of Birth ( ) Age Years. Male/female:-

Registration No. Permanent resident of

House No. __________Ward/Village/_________/street__________ Post Office__________ District __________ State____________________. Whose photograph is affixed above and am satisfies that he/she is a case of Specific Learning Disability. His/her extent of percentage physical impairment/disability in has been evaluated as per guidelines and is shown against the relevant disability in the table below:-

(Please strike out the disabilities which are not applicable)

2. The above condition is progressive/non- progressive/likely to improve/not likely to improve.

3. Reassessment of disability is:

-

(i)

not necessary.

Or

-

(ii)

is recommended/after____ years _______months. And therefore this certificate shall be valid till (DD/MM/YY) ________________.

@- e.g. Left/Right/both arms/legs

#- e.g. Single eye/both eyes

€- e.g. Left/Right/both ears

4. The applicant has submitted the following documents as proof of residence:-

(Authorised Signatory of notified Medical Authority)

(Name and Seal)

Countersigned

(Countersignature and seal of the CMO/Medical Superintendent/Head of Government Hospital, in case the certificate is issued by a medical authority who is not a government servant (with Seal)

Note: In case this certificate is issued by a medical authority who is not a government servant, it shall be valid only if countersigned by the chief Medical Officer of the District.”

Note: The principal rules were published in the Gazette of the India vide notification number S.O. 908 (E), dated the 31st December, 1996.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Manisha Gaur for her input on remedial techniques. Masarrat Khan, Simran Sachdev Arora, Ruchi Brahmachari for their input for Table 5.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kirk SA. Oxford, England: Houghton Mifflin; 1962. Educating Exceptional Children. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bateman B. An educational view of a diagnostic approach to learning disorders. In: Hellmuth J, editor. Learning Disorders. Vol. 1. Seattle, WA: Special Children Publication; 1965. pp. 219–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahoo MK, Biswas H, Padhy SK. Psychological co-morbidity in children with specific learning disorders. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:21–5. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.152243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah HR, Trivedi SC. Specific learning disability in Maharashtra: Current scenario and road ahead. Ann Indian Psychiatry. 2017;1:11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margari L, Buttiglione M, Craig F, Cristella A, de Giambattista C, Matera E, et al. Neuropsychopathological comorbidities in learning disorders. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halperin JM, Gittelman R, Klein DF, Rudel RG. Reading-disabled hyperactive children: A distinct subgroup of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1984;12:1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00913458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karande S, Satam N, Kulkarni M, Sholapurwala R, Chitre A, Shah N, et al. Clinical and psychoeducational profile of children with specific learning disability and co-occurring attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61:639–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendren RL, Haft SL, Black JM, White NC, Hoeft F. Recognizing psychiatric comorbidity with reading disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:101. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhary AK, Meghwal J. A study of anxiety and depression among learning disabled children. Psychology. 2015;5:484–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fristad MA, Topolosky S, Weller EB, Weller RA. Depression and learning disabilities in children. J Affect Disord. 1992;26:53–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Relationships between learning difficulties and psychological problems in preadolescent children from a longitudinal sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:429–36. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199904000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poletti M. WISC-IV intellectual profiles in Italian children with specific learning disorder and related impairments in reading, written expression, and mathematics. J Learn Disabil. 2016;49:320–35. doi: 10.1177/0022219414555416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panicker AS, Bhattacharya S, Hirisave U, Nalini NR. Reliability and validity of the NIMHANS index of specific learning disabilities. Indian J Ment Health. 2015;2:175–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmad FK. Exploring the invisible: Issues in identification and assessment of students with learning disabilities in India. Transcience. 2015;61:91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unni JC. Specific learning disability and the amended “Persons with disability act”. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:445–7. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayan J. Grade Level Assessment Device for Children with Learning Problems in Schools (GLAD). Secunderabad: National Institute for the Mentally Handicapped. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sholapurwala RF. 1st ed. Mumbai, India: Jenaz Printers; 2010. Curriculum Based Test for Educational Evaluation of Learning Disability. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha UK. New Delhi: Psychomatrix Corporation; 2012. Specific Learning Disability-Screening Questionnaire (SLD-SQ) pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DALI. [Last accessed on 2018 Jun 22]. Available from: http://www. 14.139.62.22/DALI/index.php .

- 22.Gabrieli JD. Dyslexia: A new synergy between education and cognitive neuroscience. Science. 2009;325:280–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1171999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulme C, Melby-Lervåg M. Educational interventions for children's learning difficulties. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor E, editors. Rutter's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 6th ed. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2015. pp. 533–44. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Döhla D, Heim S. Developmental dyslexia and dysgraphia: What can we learn from the one about the other? Front Psychol. 2015;6:2045. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung P, Patel DR. Dysgraphia. Int J Child Adolesc Health. 2015;8:27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalev RS. Developmental dyscalculia. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:765–71. doi: 10.1177/08830738040190100601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price GR, Ansari D. Dyscalculia: Characteristics, causes, and treatments. Numeracy. 2013;6:2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah H, Rupani K, Mukherjee S, Kamath R. A comparative study of family impact in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and learning disability. Indian J Ment Health. 2016;3:70–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lahane S, Shah H, Nagarale V, Kamath R. Comparison of self-esteem and maternal attitude between children with learning disability and unaffected siblings. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:745–9. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0915-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snowling MJ. Early identification and interventions for dyslexia: A contemporary view. J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2013;13:7–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2012.01262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.RPWD Act. 2016. [Last accessed on 2017 May 02]. Available from: http://www.tezu.ernet.in/notice/2017/April/RPWD-ACT-2016 .

- 32.RWPD Act 2016 Rules. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 25]. Available from:http://www.ccdisabilities.nic.in/content/en/docs/RPwDRule2017.pdf .