INTRODUCTION

Over the last half century, it is now well established that depression can occur at any age, and it has been documented as early as infancy. In terms of epidemiology, different studies which have evaluated the prevalence of depression in children and adolescents suggest that the prevalence varies according to the different age groups. Prevalence figures reported for infants vary from 0.5% to 3% in clinic population, whereas in preschool children, the prevalence rate for major depression (1.4%) has been reported to be higher than depression not otherwise specified (0.7%) and dysthymia (0.6%). Studies done in community settings suggest the prevalence of depression in children to range from 0.4% to 2.5% and among adolescents to be from 0.4% to 8.3%. Lifetime prevalence through adolescence is considered to be as high as 20%. Prior to puberty, depression is known to have equal gender representation; however, among adolescents, the male: female ratio is 1:2. Over the years, it has also been understood that depression in children and adolescents is a chronic and relapsing condition, which does not remits spontaneously and hence, there is a need to identify and treat the same at the earliest to reduce its long-term negative consequences. Childhood depression has been shown to lead to an increased risk of poor academic performance, impaired social functioning, suicidal behavior, homicidal ideation, and alcohol/substance abuse. It is also associated with an increased risk of recurrent depressive episodes. Unfortunately, a major proportion of depression in children and adolescents is underdiagnosed and undertreated.

SCOPE OF THE GUIDELINES

The Indian Psychiatric Society published clinical practice guidelines for the management of depression in children and adolescents for the first time in the year 2007. Over the years, more research has accumulated in this area, and hence an effort is made to update the previous version of the clinical practice guidelines. These guidelines intend to provide a broad framework for the proper assessment and management of depression in children and adolescents. It is recommended that these guidelines must be read with the previous version. These guidelines must not be considered as a substitute for the professional knowledge and clinical judgment of the treating psychiatrist. It is important to remember that these guidelines are not applicable to any specific treatment setting and will require minor modification to suit to the needs of the children and adolescents in various treatment settings. Accordingly, the recommendations made as part of this guideline may have to be tailored to the needs of the individual patient.

ASSESSMENT OF DEPRESSION IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

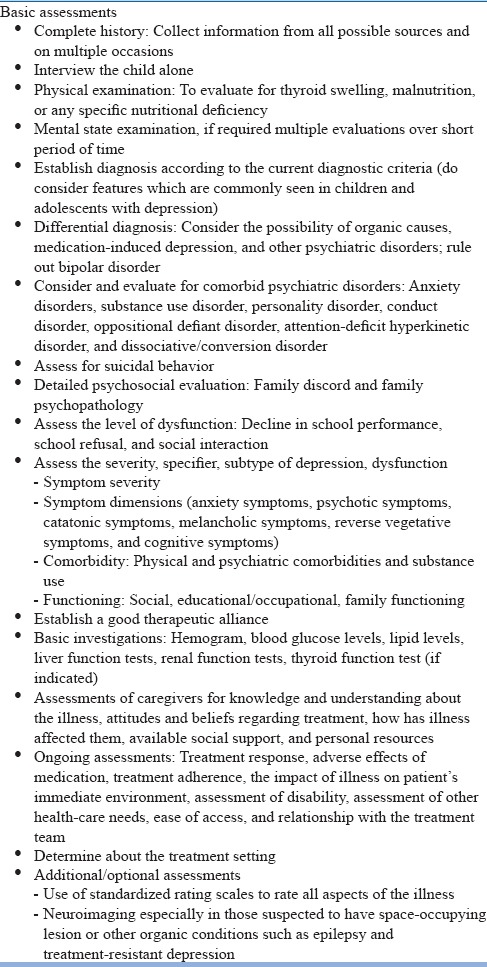

Assessment of depression in children and adolescents involves establishing the diagnosis; evaluating comorbid conditions; considering all the possible differential diagnoses; and evaluating psychosocial issues contributing to the development and continuation of depression such as family discord, family psychopathology, suicidal risk, and the ensuing dysfunction. It also involves developing a good therapeutic alliance with the children and adolescents and their family members and making decision about treatment setting and patient's safety. Assessment needs to be understood as an ongoing process and patients may have to be assessed regularly, as per the need and phase of the treatment [Table 1].

Table 1.

Assessment of children and adolescents presenting with depression

History Taking: The complete psychiatric evaluation should include a history of the present illness and current symptoms; evaluation for symptoms of mania or hypomania, taking history, and evaluation for general medical conditions; evaluation for a history of substance use disorders; evaluation for a personal history (e.g., psychological development, response to life transitions, and major life events); evaluation for a social, educational, and family history; and a review of the patient's medications, past treatment history, physical examination, detailed mental status examination, and diagnostic tests as indicated. In general, for identification of depression in children and adolescents, it is better to collect information from all the possible sources, i.e., report and observation of patients, parents, peers, siblings, and teachers during the clinical interview. It is important to remember that the child and parents or other caregivers need to be interviewed separately and also together. Usually, more than one interview may be required to get the complete picture of depression. It is suggested that evaluation of children with depression should involve interview of both the parents and the child. Differences are noted in the parent reports and self-reports of depressive symptoms. Parents more often report externalizing symptoms such as irritability, whereas children themselves more often report internalizing symptoms such as low mood.

During assessment, developmental perspective needs to be taken into consideration and besides the routine mental status examination, play techniques can be used as part of the assessment. It is reported that, compared to healthy and nondepressed children, preschool children with depression depict significantly lower symbolic play and more often indulge in nonplay behavior such as exploration of toys and interaction with the examiner. Children with depression also demonstrate less coherence in their play.

Diagnostics and Clinical Features: As per the prevailing nosological systems, i.e., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fifth revision (DSM-5) and International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, depression must be diagnosed in children and adolescents by using the same diagnostic criteria, as used for other age groups. The DSM-5 suggests that the criteria of “presence of depressed mood” can be replaced by “irritable mood” in children and adolescents. The diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder (equivalent of dysthymia) requires duration of 1 year in contrast to the 2-year duration required for adults. However, it is considered that the criteria given in the DSM do not address the developmental variations in symptom manifestations, and hence it is required to modify the criteria to pick up depression in children. It is suggested that depression in infants may manifest as failure to thrive, severe psychomotor delay, apathy, sad facial expression, and lack of responsiveness to alternative caregivers. It is also important to note that, in view of the level of cognitive development, younger children may appear sad but may not be able to verbalize the same. Instead, these children may have irritability, which may manifest as frustration and temper tantrums and behavioral problems. Other symptoms indicative of depression in children include increased rejection sensitivity.

Certain cognitive symptoms such as low self-esteem, hopelessness, and depressive guilt, which are seen in patients with depression in other age groups, may not be apparent in children with depression because of lack of cognitive development (i.e., lack of development of abstract thinking). The concern about the future (hopelessness) is more strongly associated with depression in adolescents than in children, whereas guilt is more often seen in children than for adolescents. According to the current DSM criteria, patients with depression may have either an increase or a decrease in appetite/weight from usual. However, it is important to remember that children will have normative increase in appetite and weight and due to this, the utility of increases in appetite or weight as a clear feature of depression in youth is questionable. It is suggested that, although decreases in appetite and weight are associated with depression in children and adolescents, increases are not. It is also suggested that strict application of 2-week duration criteria may also not be appropriate to very young children. Evidence suggests that preschool children meeting all criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) independent of the duration criteria exhibit higher levels of MDD symptoms and functional impairment than controls. Hence, some of the researchers suggest that, rather than focusing on the presence of persistent mood symptoms for 2 weeks, in children and adolescents, the clinicians should focus on the presence of symptoms for “most days than not.” Besides the DSM criteria, evidence suggests that younger children with depression more often manifest with somatic symptoms (headache, abdominal pain, and general aches and pains), anxiety features (separation anxiety and phobias), restlessness, and psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations. Adolescents with depression often report symptoms of anhedonia, boredom, hopelessness, increased sleep, weight change (including failure to reach appropriate weight milestones), substance use including alcohol, and suicide attempts.

In children, when psychotic symptoms are present as part of depression, these commonly manifest as auditory hallucinations. Adolescents with depression usually report psychotic symptoms in the form of delusions. It is important to note that, compared to adults with similar manifestations, the risk of bipolar disorder is higher among children and adolescents who manifest psychotic symptoms. Adolescents may also manifest with seasonal affective disorder.

Considering the difference in manifestation and developmental or age-specific symptoms, it is suggested that assessment of depression in children and adolescents should cover the acronym “DUMPS.” “D” stands for the evaluation of duration of symptoms, depressed mood, defiance and disagreeability, and distant or withdrawal behavior. “U” stands for the presence of undeniable drop in educational performance/grades or interest in school, which is seen quite frequently in young children. Drop in educational attainments arises due to poor concentration, lack of ability to make decisions, loss/lack of interest, and poor motivation for doing activities that were pleasurable earlier. Accordingly, it is suggested that report cards of previous years should be reviewed as this can help in recognizing the beginning of decline of grades, or fluctuations with certain seasons (e.g., a drop every winter). Poor concentration and an inability to complete the work may be particularly a major issue in high school going attending adolescents, whose school work mainly involves writing, doing laboratory assignments, reading and answering questions, etc. Children who fall behind in their class often start missing classes or avoid going to school. Accordingly, school avoidance should be an alarm for the evaluation of depression. “M” stands for morbid and strange behavior which may be actually an indirect manifestation of suicidality. “P” represents pessimistic attitude, which is commonly seen in children and adolescents with depression. “S” represents somatic symptoms, particularly abdominal pain and headaches, which are common in young people.

Evaluate for comorbidity

In general, it is said that comorbidity is a rule rather than the exception in children and adolescents with depression. The commonly seen comorbid conditions include anxiety disorders, substance use disorder, personality disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit hyperkinetic disorder (ADHD), and dissociative/conversion disorder. The high comorbidity is attributed to the common environmental etiological factors and shared genetic influences between depression and most of the common comorbid disorders.

Consider the possibility of the underlying medical cause

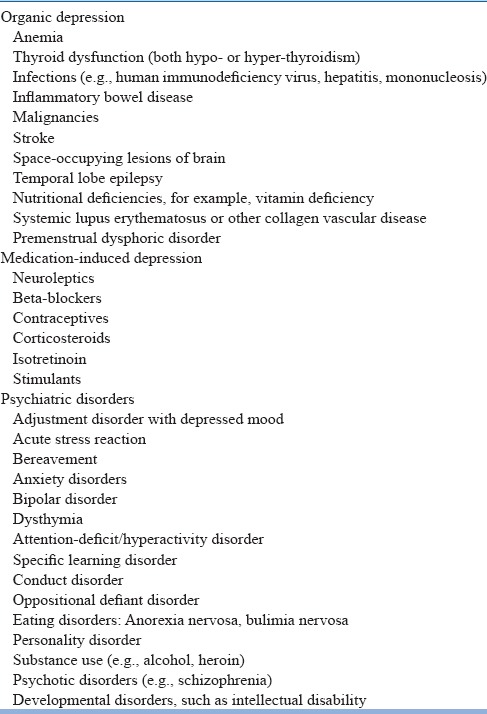

As in other age groups, it is important to evaluate whether the depressive symptoms can be attributed to medical illnesses or other psychiatric disorders. The common medical illnesses and psychiatric disorders which need be considered for differential diagnosis are summarized in Table 2. In addition, due importance must be given to the intake of medications as many medications are known to cause depression [Table 2]. In case the symptoms can be better understood and attributed to a medical illness, then the diagnosis of MDD is not appropriate. Organic diseases, such as hypothyroidism, metabolic abnormalities, and space-occupying lesions, need to be ruled out in every infant who has depressive symptoms. Considering the fact that depression may be attributed to various physical illnesses, a through physical examination must be carried out in all children and adolescents presenting with depressive features. In case any physical illness is suspected, help of pediatrician and other specialist as per the requirement may be taken. At times, it is difficult to identify depression in the presence of a medical disorder, especially when the medical disorder is associated with sleep disturbance, change in appetite, somatic symptoms, and lethargy/loss of energy. In such a scenario, clinicians should look for ideas of guilt, hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness, and self-harm including suicide, which are unlikely to be due to a medical disorder. When present, these features are suggestive of diagnosis of MDD. Depending on the need, various investigations must be carried out.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis for depression in children and adolescents

Consider the possibility of Bipolar Disorder

It is important to consider bipolar disorder in the differential diagnosis as use of antidepressants in a child or adolescent with undiagnosed bipolar disorder can lead to switch/behavioral activation. A possibility of bipolar disorder needs to be considered, when the children and adolescent with depression have psychotic symptoms, marked psychomotor retardation, reverse neurovegetative symptoms (increased sleep and appetite), irritability, and a history of bipolar disorder in the family.

Consider other psychiatric disorders in the differential diagnosis

Efforts must be made to rule out various psychiatric disorders by focusing on the longitudinal course of the symptoms, presence of other core symptoms of various disorders, and severity of symptoms. Further, it is important to remember that many of the psychiatric disorders, considered as differential diagnosis, also co-exist with depression.

Assessment for suicidal behavior

One of the most important aspects of assessment of children and adolescents with depression includes the assessment of suicidal risk. Clinicians should not underestimate the risk of suicidal behavior in children and adolescents. Clinicians should ask about the presence of suicidal ideation, specific plans for self-injury, and any history of actual self-harm or overt threats or gestures. Empirical data suggest that careful inquiry often helps to identify unsuspected suicidal ideation or acts. Developmental perspective needs to be taken while evaluating suicidal behaviors in prepubertal children, and attention must be paid to the child's own concept of death, as, at times, children do not view death as irreversible. This lack of understanding of irreversibility, in some cases, may actually increase the risk of a suicidal attempt. Inquiry can be started with questions like “Do you ever feel things are so bad that you wish you were dead?” and “Do you ever feel like wanting to hurt yourself or do anything to kill yourself?” If the patient responds as yes to any of these queries, further assessment can include questions like “Have you ever done anything to hurt yourself or to try to kill yourself?” If response to these questions is in affirmation, then further assessment should focus on the actual committed act, i.e., what was done, what precipitated such act, and what was the outcome of such an act.

Motivation and intent of any previous attempt need to be assessed, and the important fact to remember is that it is not the method per se, but the understanding of lethality is more important. Risk factors for repetition of the act and completed suicide include a history of multiple attempts in the past, persistent suicidal ideation, and high intent. Other factors which need to be assessed include psychological and interpersonal factors, family and interpersonal issues, physical and psychiatric comorbidities, chronicity of depression, evidence of risk-taking behaviors in the past, impulsivity, aggression and hostility, presence of commanding auditory hallucinations asking the child to hurt or kill him or her, and history of physical and sexual abuses and failure (in examinations and love). Assessment of suicidal risk is not complete without the inquiry about the available lethal means (potentially lethal drugs, access to guns) because such means magnifies the risk of completed suicide.

Evaluate the level of dysfunction

Dysfunction assessment needs to cover the academic performance, family functioning, and peer relationship.

Evaluate the support system

Child's support system forms the backbone of the treatment plan. While assessing the support system, the fact to be kept in mind is that it is not the number which matters, but it is the comfort level of the child with that adult which matters. At times, although both the parents may be around, one may be overcritical and the other may be sulking his/her guilt. Accordingly, depending on the need, the parents or significant others may require evaluation for psychiatric morbidity.

Use of rating scales

Routine clinical assessments may be supplemented by standardized rating scales, depending on the feasibility.

Investigations

The list of investigations is usually guided by the assessment. In general, neuroimaging is not indicated in children and adolescents with depression. However, neuroimaging may be considered in patients suspected to have intracranial space-occupying lesions or other intracranial pathology.

Assessment of knowledge and understanding of the disorders

Assessment should also include evaluation of knowledge and understanding about the disorder among the patients and their parents/caregivers/family members. Additionally, it is important to evaluate the attitudes and beliefs regarding treatment of both patient and caregivers. It is also important to understand the personal and social resources of the caregivers and the impact of the illness on the caregivers.

Develop therapeutic alliance

While carrying out the assessment, clinicians should focus on developing a good therapeutic alliance with the child and family, as early as possible, to ensure involvement of the patient and family in the treatment over the period of time. The most important component for development of a good therapeutic alliance involves addressing the concerns of patients and their families and respecting their wishes for treatment. There is also a need on the part of the clinician to be aware of issues such as transference and counter-transference issues, even though these may not be directly addressed in treatment.

Ongoing assessment

Assessment needs to be considered as an ongoing process and after starting treatment, it is important to continuously assess the response to treatment, adverse effects of medications, medication and treatment adherence, the role of patient's immediate environment on patient's illness, disability assessments, other health-care needs, and ease of access and relationship with the treatment team. Other issues which must be considered include caregiver burden, stigma experienced/perceived by the patient/caregiver, and coping abilities of both patient and the caregivers. Appropriate interventions must be carried out to address the emerging issues during the course of the treatment.

FORMULATING A TREATMENT PLAN

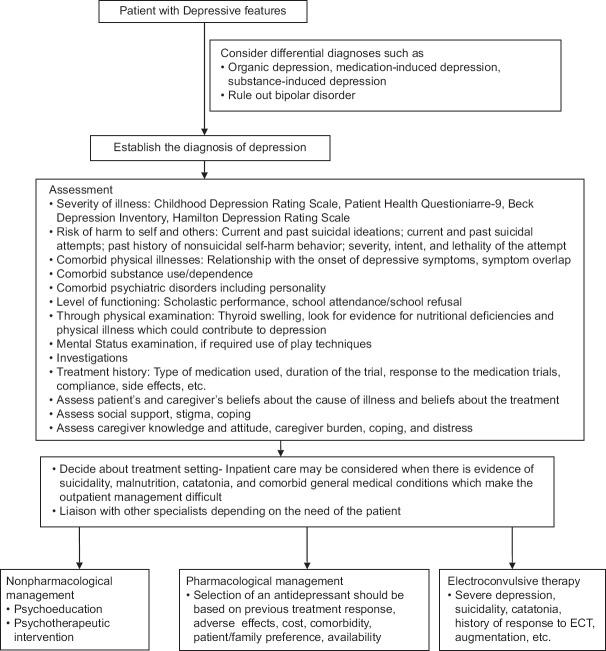

Formulation of a treatment plan involves deciding about the treatment setting and determining the type of psychological treatment and type of medications to be used [Figure 1]. Both patients and caregivers should be actively consulted while preparing the treatment plan. The treatment plan formulated should be feasible, flexible, and practical to address the needs of the patients and caregivers. Clinicians should continuously work with the patient and the caregivers and keep on re-evaluating the treatment plan and make necessary modifications.

Figure 1.

Initial evaluation and management plan for depression in children and adolescents

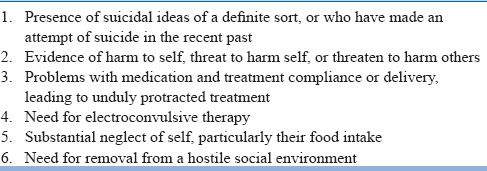

DETERMINE A TREATMENT SETTING

Children and adolescents with depression need to be managed in the individualized least restrictive treatment environment, which is safe and effective too. While deciding about the treatment setting following factors should be taken into consideration: clinical severity of symptoms, available support from parents and significant others, motivation for treatment, and ability of family members and significant others to ensure the safety of the patient. Children and adolescents with active suicidal or homicidal ideation, intention, or a plan require close monitoring. Hospitalization is usually indicated when a child or adolescent poses a serious threat of harm to self or others. Other indications for inpatient care are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Indications for admission in children and adolescents with depression

However, it is important to remember that, for providing inpatient care, provisions of Mental Health Care Act, 2017 (MHCA, 2017), need to be followed.

MONITOR THE STATUS AND SAFETY OF PATIENT

Over the course of treatment, the clinical picture of patient may change, with emergence of certain new symptoms and subsidence of the existing symptoms. Accordingly, children and adolescents with depression need to be monitored for the emergence of or change in destructive impulses toward self or others. If anytime during the course of treatment, the risk of harm to self or others is eminent, hospitalization and/or more intensive treatment should be considered. It is also important to reconsider the diagnosis if there are significant changes in a patient's psychiatric status or if there is emergence of new symptoms.

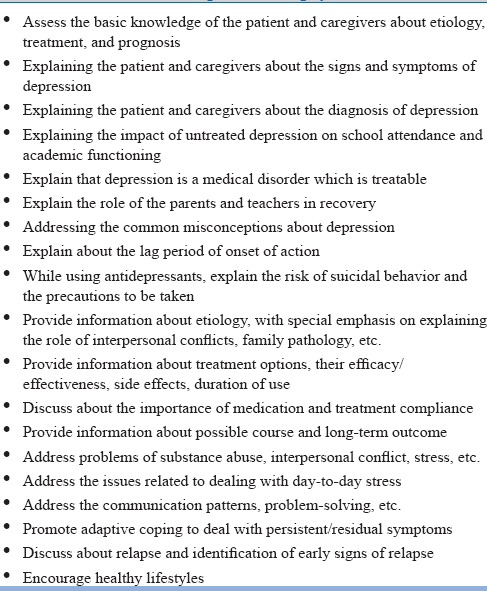

PROVIDE PSYCHOEDUCATION TO THE PATIENT AND FAMILY

Psychoeducation is an important component of management of depression in children and adolescents. It not only helps the patients and their families, but also helps the clinician. Psychoeducation makes the patient and family members informed partners in the decision-making and also enhances the treatment adherence. Psychoeducation can also help in formulating a treatment plan, decreasing parental self-blame (I’m not a good parent) and blame of the child (He's manipulative, or He's lazy). Psychoeducation can be offered to all family members and/or significant others because the depression (e.g., lack of interest, fatigue, irritability, and isolation) in children and adolescents can affect each of them. Psychoeducation of family members and/or significant others can also help them in identifying their own depressive symptoms and potential need for treatment. Occasionally, family members, peers, and friends take the patient's behaviors personally or otherwise become emotionally overinvolved. This leads to more stress, guilt, or anger for the patient to cope with. Supportive and understanding relationships improve the patient's and family's global functioning and treatment outcome.

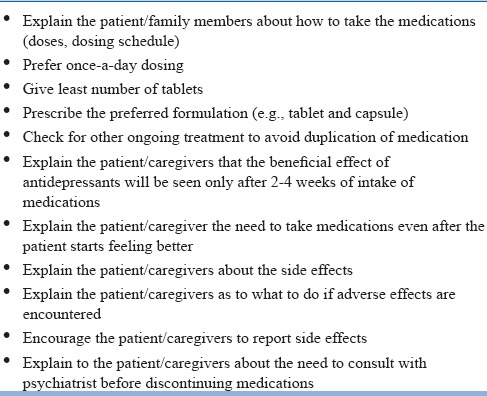

ENHANCE TREATMENT ADHERENCE

The key to the successful treatment of depression is adherence to treatment plans. Hence, the need of regular follow-up and drug compliance needs to be emphasized. Measures which can improve the medication adherence are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Measures which can improve medication compliance

WORK WITH THE PATIENT AND CAREGIVERS TO ADDRESS THE ISSUES OF RELAPSE

In view of the fluctuation of symptoms in depression over time, patients and their families need to be informed about the significant risk of relapse. They should be made competent to recognize the early signs and symptoms of a new episode. Families need to be informed that starting treatment during the early phase of the relapse can decrease the likelihood of a full-blown relapse or complication.

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR MANAGEMENT FOR DEPRESSION

Treatment options for the management of depression in children and adolescents include psychotherapies, antidepressants, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and other somatic treatments such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

Psychotherapeutic interventions

Various psychotherapeutic interventions such as cognitive therapy, psychotherapy, art therapy, drama therapy, and family therapy have been used in the management of depression in children and adolescents. These interventions have been evaluated in the form of individual and group interventions. Cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs) attempt to address the cognitive distortions in depressed children and adolescents. In CBT, child is the focus of treatment and therapists play an active role in treatment to form a collaborative relationship to solve problems. The therapist guides the child as to how to monitor and keep a record of thoughts and behavior, need for diary-keeping, and importance of homework assignments and treatment consisting of behavioral techniques (activity scheduling) and cognitive strategies (cognitive restructuring). Studies which have evaluated CBT for the management of depression in children suggest that, in short term, CBT is better than no treatment. With respect to the efficacy of CBT among adolescents with depression, there is conflicting evidence to draw any definite conclusion. Some studies suggest that CBT is an efficacious treatment for depressed adolescents and it is better than interventions such as family therapy and supportive counseling. However, some of the studies refute this evidence and suggest that the efficacy of CBT is similar to placebo. Studies which have compared the combination of CBT and medication with medication alone suggest that combination is more effective than the medication alone. A recent meta-analysis which included nine studies evaluating the efficacy of CBT in children and adolescents with depression showed that CBT was better than no treatment, but it was not found to be better than waitlist or placebo. This study further showed that the efficacy of CBT was better in those without comorbidity and without parental involvement. The number of CBT sessions in a treatment course in these studies has varied from 5 to 16 sessions; however, the meta-analysis suggests that the number of sessions does not have a significant influence on the efficacy. Another review of efficacy trials suggests that CBT is more efficacious in adolescents (aged 13–24 years) than in children (aged ≤13 years).

In view of the association of depression in children and adolescents with problems in relationship, interpersonal therapies (IPTs) have also been evaluated for the management of depression in children and adolescents. Addressing the interpersonal issues can lead to alleviation of depressive symptoms, irrespective of the personality organization or biological vulnerability of the individual. The main goals of IPT are to identify and treat the depressive symptoms and address the interpersonal issues associated with the onset of depression. A meta-analysis which included data of 538 participants from seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that, when compared with controlled conditions (placebo, waitlisted, or treatment as usual), IPT had significantly superior efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms and leading to response/remission, for all-cause discontinuation rates and improvement in the quality of life/functional improvement. Another meta-analysis which included ten studies comprising 766 participants which evaluated the efficacy of IPT among adolescents (IPT-A) with depression reported that IPT-A was significantly superior to control or treatment as usual in reducing depressive symptoms among adolescents. In view of the association of depression in children with family pathology, including mental illness and dysfunctional family relationships, many authors suggest the role of family therapy in the management of childhood depression.

Use of antidepressants

Efficacy of many antidepressants has been evaluated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in children and adolescents. Antidepressants which have been evaluated in children and adolescents include imipramine, des-imipramine, clomipramine, nortriptyline, amitriptyline, fluoxetine, paroxetine, escitalopram, sertraline, duloxetine, venlafaxine, nefazodone, and mirtazapine. Results of RCTs of most of these antidepressants came out to be negative. A recent network meta-analysis, which included data on 14 antidepressants from 34 trials involving 5260 participants, concluded that only fluoxetine was significantly better than placebo. This meta-analysis also concluded that fluoxetine was better tolerated than duloxetine and imipramine. Similarly, tolerability of citalopram and paroxetine was significantly better than that of imipramine. A Cochrane review, which included 19 RCTs, which evaluated the efficacy of newer antidepressants in the management of depression in 3335 children and adolescents, concluded that, in general, there is no difference between antidepressants and placebo in terms of efficacy. However, in view of the risk associated with untreated depression, the authors concluded that fluoxetine might be the medication of first choice. Further, the authors concluded that use of antidepressants was associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior, compared to placebo.

The multicentric National Institute of Mental Health-funded study, i.e., Treating Adolescent Depression Study (TADS), which compared the use of fluoxetine alone, CBT alone, or combination of both, concluded that combination of CBT and fluoxetine offered the highest treatment response rates followed by response rate to fluoxetine alone. CBT alone was not found to be efficacious. Response rate to fluoxetine alone was 61% as measured by the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI)-I scores compared to only 35% with placebo (P = 0.001). The combination of fluoxetine and CBT has been reported to have a response rate of 71%. The predictor of good response to treatment in the TADS study included being younger, less chronically depressed, having higher functioning, less hopelessness with less suicidal ideation, fewer melancholic features, fewer comorbid diagnoses, and greater expectations of improvement with treatment. In this study, combined treatment, under no condition, was less effective than monotherapy. In terms of remission rates, data from TADS study suggest that remission rates are significantly higher with combination treatment (37%) when compared to the other treatment groups (fluoxetine – 23%; CBT – 16%; and placebo – 17%), with odds ratios of 2.1 for combination group versus fluoxetine, 3.3 for combination group versus CBT, and 3.0 for combination group versus placebo. Escitalopram has been evaluated in two recent multicentric trials. These two double-blinded RCTs included adolescents aged 12–17 years who were treated with escitalopram 10–20 mg/day. These trials showed that escitalopram was superior to placebo and was well tolerated. One of these trials also showed that the response and remission rates were significantly higher with escitalopram. There was no significant difference between the escitalopram and placebo groups in terms of treatment-emergent suicidal behavior.

Among the various antidepressants, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of United States has approved the use of fluoxetine in children aged 8 years or above and use of escitalopram in children aged 12 years or above.

Many studies have also compared the efficacy of antidepressants versus psychological treatment versus combined treatment. A Cochrane review which evaluated these studies showed that there is limited evidence to suggest that antidepressant medication is more effective than psychotherapy in terms of immediate postintervention remission rates. Further, the authors concluded that the evidence is limited to say that combination treatment was more effective than antidepressant alone in achieving higher remission rates, and there is no evidence to suggest that combination treatment was better than psychological therapy alone. Further, the existing data suggest that use of antidepressants is associated with higher suicidal behavior. The authors concluded that, overall, the evidence is limited to draw any conclusions.

One of the major controversies with respect to the use of antidepressants among children and adolescents is the risk of suicidal behavior. Based on the available data of possible increase in the risk of suicidal behavior with antidepressants, the FDA has issued a black box warning against the use of antidepressants among children and adolescents. Accordingly, cautious approach need to be considered while using antidepressants among children and adolescents, and they must be closely monitored for any treatment-emergent suicidal behavior.

Another important issue while using antidepressants among children and adolescents is medication-induced behavioral activation which is characterized by the symptoms of irritability, agitated and aggressive behavior, anxiety symptoms (i.e., features of panic attacks), restlessness, hostility, akathisia, hypomania/mania, and emergence of psychotic symptoms. There is some evidence to suggest that antidepressant-associated behavioral activation is associated with the use of higher doses of medications. Hence, it is suggested that children and adolescents receiving antidepressants must be closely monitored while starting antidepressant medication and during the period of change of doses of antidepressant medications.

Electroconvulsive therapy

ECT is not the first-line treatment in the management of depression in children and adolescents. In general, most of the available data are in the form of retrospective studies, and these studies suggest that ECT is effective in children and adolescents with depression, with response rates reported in the range of 64%–100%. In a review, Rey and Walter reviewed sixty studies covering 396 patients ≤18 years of age (only five of these were younger than 12 years) and reported a remission rate of 63% for the children and adolescents with depression. Three-fourth of the children and adolescents with catatonia, irrespective of the underlying psychiatric disorder, showed a significant improvement with ECT. The authors also found that ECT was administered almost always after other treatments have failed and when a patient's symptoms are incapacitating or life threatening and a considerable improvement with ECT was seen in approximately 90% of adolescents with depression who were resistant to pharmacotherapy. Two other reviews, which included other available studies and case reports of the use of ECT in children and adolescents reported the efficacy of ECT in depression in the range of 60%–100%. Side effects such as fatality, premature termination of treatment, and prolonged seizures are rarely reported with the use of ECT in children and adolescents. Studies which have evaluated the long-term cognitive side effects of ECT also report no significant difference between children and adolescents who are treated with ECT and controls.

Treatment-resistant depression

There is limited data on the management of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) among adolescents. A multicentric randomized study, named “Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA),” has evaluated 334 patients aged 12–18 years, diagnosed with major depression of moderate severity, who did not respond to an adequate trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (i.e., a trial of at least 8 weeks, of which in the last 4 weeks, patients received a dose of at least 40 mg/day of fluoxetine or its equivalent). These patients were randomized to receive a different SSRI or venlafaxine, with or without CBT for 24 weeks. The outcome of the study was determined by using CGI-Improvement Scale and Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) scale. A CGI-Improvement score of 2 or less and a reduction in CDRS-R score by 50% were considered as indicators of efficacy. At 12 weeks, CBT plus switch to venlafaxine or second SSRI was found to have higher response rate than switch to medication alone. Overall, there was no difference in the efficacy of venlafaxine and second SSRI. There was no difference between the two antidepressant groups in terms of suicidal behavior as an adverse effect, but compared to SSRIs, venlafaxine was associated with higher rise in diastolic blood pressure and pulse rate and dermatological problems. Further analysis of data showed that higher plasma level of antidepressants was associated with better response. The second phase of TORDIA trial was an open trial in which those who did not respond to the first treatment were changed to the second treatment at 12 weeks and then evaluated at the end of 24 weeks. Those who responded to treatment at the first phase were continued on the same treatment during the second phase too. It was observed that, at 24 weeks, patients who demonstrated clinical response at 12 weeks had higher remission rate and shorter time to remission. Remission rate was higher for patients with lower baseline depression, hopelessness, and self-reported anxiety. Remission was also predicted by lower depression; hopelessness; anxiety; suicidal ideation; family conflict; absence of comorbid dysthymia, anxiety; and drug/alcohol use and impairment at 12 weeks. Of those who responded by week 12, one-fifth (19.6%) experienced relapse by week 24. Long-term follow-up at 72 weeks of patients recruited to the TORDIA study showed that 61.1% of the patients achieved remission. The remission rates and time to remission were not affected by the treatment received during the first 12 weeks. However, compared to patients who received venlafaxine, those who received SSRI had more rapid decline in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideations as per the self-report. Factors which were associated with lack of remission included higher severity of depression at the baseline, higher level of dysfunction at the baseline, and use of alcohol/drug at the baseline. Among patients who had achieved remission at week 24, one-fourth (25.4%) relapsed in the subsequent 1 year.

PHASES OF ILLNESS/TREATMENT

As in other age groups, management of depression in children and adolescents is broadly divided into three phases, i.e., acute, continuation, and maintenance phases. Maintenance treatment is considered when there is evidence for recurrent depressive disorder.

Acute-phase treatment

The goals of acute-phase management are to effectively treat depression to achieve remission, address the comorbid disorders, promote social and emotional adjustment, improve self-esteem, relieve family distress, and prevent the relapse and recurrence of symptoms. Treatment should also lead to elimination of dysfunction and improvement in the quality of life of the child along with improvement of family functioning.

Irrespective of the specific treatment modality used, all the patients and their parents must be provided adequate psychoeducation [Table 5].

Table 5.

Basic components of psychoeducation

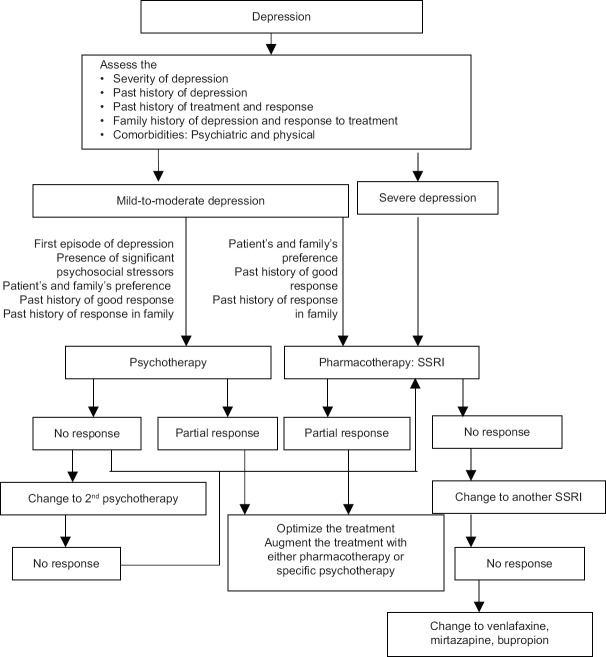

Selection of initial treatment

Selection of initial treatment modality is often guided by the severity of depressive symptoms, number of previous episodes, chronicity of depression, age of the patient, contextual factors such as familial conflict, academic difficulties, exposure to negative life events, adherence with treatment in the past, response to treatment in the past, motivation of patient and family for treatment, and response to a particular treatment in family members [Figure 2]. The most important factor in selecting a particular treatment modality is family's and patient's preference. It is observed that, at times, a child or adolescent with social phobia may refuse group therapy. Similarly, an anxious parent or patient may not like the idea of use of medications as the first-line treatment modality. In such cases, alternate treatments may be required. Besides the patient, family, and clinical variables, it is also important to take into consideration the clinician's factors such as clinician availability, motivation, and expertise with a specific therapy, before finalizing the initial treatment modality. Accordingly, the decision to start an antidepressant or specific psychotherapy should be made jointly by the clinician and adequately informed parents (guardians) with assent from the child.

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm of depression in children and adolescents

For mild-to-moderate depression, psychotherapy is considered to be the preferred initial modality of treatment. Selection of specific type of psychotherapy needs to take into consideration the clinician variables such as clinician's experience and comfort in carrying out such a therapy. CBT should be preferred in children and adolescents with cognitive distortions and comorbid anxiety disorders. In the presence of stressors, such as separation from parents, issues with authority, and loss or death of relatives or friends, IPT may be beneficial. Supportive psychotherapy may also be useful in the face of acute stressors. In a country like India, where a limited number of clinicians have expertise and time to carry out CBT or IPT, supportive psychotherapy may be a good alternative in such a scenario.

Antidepressants are usually considered in the presence of moderate depression for which psychotherapy is not feasible, severe depression with or without psychotic symptoms, and depression that fails to respond to an adequate trial of psychotherapy. When antidepressants are to be used, i.e., SSRIs, especially fluoxetine should be considered as the first choice in children aged ≥8 years. It has maximum support in treating depression in children and adolescents. Hence, fluoxetine should be the first-line treatment unless its use is precluded by reasons such as potential drug interactions, family resistance, and prior lack of response with an adequate dose and trial. In such cases, escitalopram or sertraline can be considered. Escitalopram has been evaluated in children aged 12 or more and has been reported to be efficacious and safe. Other alternative first-line antidepressants include sertraline. However, before prescribing antidepressants, adequate information should be provided to parents and significant others involved in the care of the children and adolescents about the potential risks and benefits of antidepressants. Informed consent to start the medication must be obtained from the parents or other legal guardians. Parents, significant others involved in the care of the child, and the patient can be explained about side effects, dose, the timing of therapeutic effect, and the danger of overdose. In patients with a high risk of committing suicide, it is recommended that their parents and significant others should be entrusted with the responsibility of storing and giving medications, especially during the acute phase and during the initial 2–4 months after complete remission. Awareness of parents and significant others involved in the care of patients should also be enhanced about the possible role of SSRIs with regard to suicidality. Accordingly, they can be asked to be vigilant and should monitor the patent's behavior. At present, there is no indication for baseline laboratory tests before starting SSRIs and during the administration of SSRIs.

When used, antidepressants should be started in low doses (usually, half the starting dose of adults) and gradually titrated up to a level where a balance between symptom control and avoidance of side effects is established. When used, fluoxetine can be started in the dose of 10 mg/day, and this can be escalated to 20 mg/day after 1 week if there are no side effects. Evidence for the effectiveness of fluoxetine in doses 20 mg/day is meager.

As depression in children and adolescents often occurs in psychosocial context, besides the use of antidepressants, there is a need to address the associated environmental and social problems with supportive measures. Combined treatment increases the chances of remission and also improves coping skills, self-esteem, adaptive strategies, and family and peer relationships of the patients.

Specific interventions should also be provided to parents and other caregivers to help them effectively deal with the child's behavioral problems such as irritability, defiance, and isolation. If any of the parent or significant family member is suspected to have any mental disorder, they should also be evaluated thoroughly and undergo the required treatment.

When a patient is treated with antidepressants, it is advisable to keep the frequency of patient's visit to once in 1–2 weeks because this helps the clinician to monitor the status of the depression (improvement or worsening) and emergence of suicidality, if any; monitor bothersome adverse effects and to adjust dose accordingly; and increase patient adherence to treatment. During follow-up, the severity of depression may be monitored objectively by using various clinician and self-rated scales.

Adequate trial

There is a lack of consensus on adequate trial of antidepressants in children and adolescents, and it is extrapolated from the adult data. Accordingly, once an antidepressant is initiated, patients should be treated with adequate and tolerable doses for at least 4–6 weeks. If no response is seen by 4 weeks, the dose can be increased to maximum tolerable dose, with monitoring of side effects. If partial response is seen with minimal or no side effects by 4–6 weeks, the clinician can increase the dose to maximum tolerable dose and wait till 8 weeks before considering the failure of response. However, these recommendations should be followed cautiously, as SSRIs possess a relatively flat dose–response curve, indicating that the maximal clinical response may be achieved at minimum effective doses. Accordingly, adequate time should be allowed for clinical response, and rapid, early dose adjustment should be avoided.

Nonresponse or partial response to initial trial

There is some data for adolescents to suggest that adolescent who do not respond to an adequate trial of the first SSRI may benefit from a second SSRI. Hence, if a patient is initially managed with a failed adequate trial of fluoxetine, then it can be stopped immediately and the dose of the second antidepressant can be increased slowly. However, if initially the patient was managed with some other SSRI, then cross tapering has to be done. If a patient experiences intolerable side effects with the use of the first SSRI (e.g., nausea, excessive restlessness, and agitation), then the second SSRI should be started at lower doses. If patient was initially treated with psychotherapy, and did not show any response, then an SSRI or alternate form of psychotherapy can be considered.

If the patient demonstrates partial response to the initial SSRI trial, then augmentation strategy can be used. The potential advantages of augmentation versus switching to another antidepressant monotherapy include no need for discontinuation of initial antidepressant, less lag time for response, un-interrupted treatment for partial responders, and treatment of breakthrough symptoms is possible. At present, information is lacking with respect to the best augmenting agent for children and adolescents who fail to respond to SSRIs or who show partial response. There is some evidence for the superiority of combination of antidepressants and CBT to antidepressants only. Based on adult data and expert opinion, augmentation may be a useful strategy for children and adolescents who show initial response with optimal doses, but fail to achieve remission. In such a situation, augmentation recommendations from adult data can be extrapolated.

Failure to respond to two antidepressant trials

If a patient fails to respond to two consecutive antidepressant trials, then it is important to re-evaluate the diagnosis. Re-evaluation should also include evaluation for comorbidity and noncompliance with medications and evaluation of other psychosocial factors which may be responsible for nonresponse. The adequacy of psychotherapy should also be evaluated, and all the possible modifications which can improve the condition should be made. With all these measures, if it is evident that the diagnosis is not in doubt and other contributing factors have been addressed and patient still fails to respond to the second antidepressant, then based on adult data, it is recommended to consider the use of venlafaxine, bupropion, or mirtazapine.

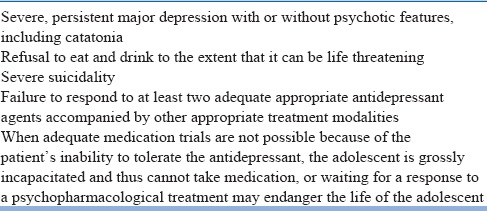

ECT should be usually considered in patients who fail to respond to two adequate antidepressants trials or in other clinical situations where ECT is consider to be lifesaving (refusal to eat or drink, severe suicidality, and catatonia) or where other treatment modalities cannot be used. According to the MHCA, unmodified ECT cannot be administered and, use of ECT in minors should be done with the informed consent of the guardian and with the prior permission of the Mental Health Review Board. Indications for ECT are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Indications for electroconvulsive therapy in children and adolescents

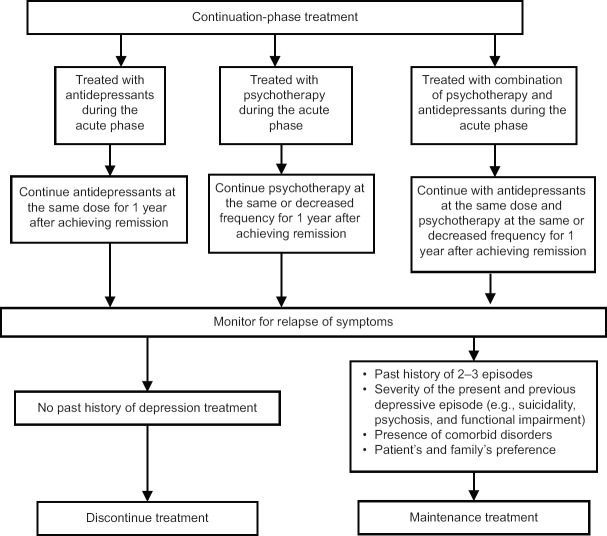

Treatment in continuation phase

There is lack of data on the treatment of depression during the continuation phase in children and adolescents; however, in view of high relapse and recurrence rates of depression, continuation-phase treatment is recommended for all children and adolescents for a minimum of 6–12 months after the resolution of acute symptoms. The frequency of visits during the continuation phase can be reduced to once a month; however, the exact frequency is usually guided by the clinical status of the patient, level of functioning, available support systems, presence or absence of stressors and ability of the patient to cope with them, motivation for treatment, and presence or absence of comorbid psychiatric or medical disorders. If psychotherapy was used during the acute phase, then the same must be continued; however, the frequency of sessions can be reduced depending on the need of the patient. If the patient was initially managed with antidepressants, then it is generally recommended to continue with the same dose of the antidepressant as used during the acute phase [Figure 3]. If the patient was treated with a combination of antidepressants and nonspecific psychotherapy during the acute phase of treatment, then they can be considered for specific psychotherapy depending on the patient's suitability [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Treatment algorithm for continuation phase of depression in children and adolescents

Treatment in maintenance phase

Usually, maintenance therapy is not indicated after the first episode. The decision for maintenance treatment should be a joint decision between the patient, family, and clinician. This should be based on patient's and family's preference and the risk for recurrence. Decision to give maintenance treatment is usually guided by the number of previous episodes, severity of the episodes (e.g., suicidality, psychosis, and functional impairment), comorbidities (physical and psychiatric), side effects of medications to be used, and patient's and family's preference. Other environmental factors, such as family stability (e.g., divorce, illness, job loss, or homelessness), psychopathology in the family, educational goals, and contraindications for treatment, also must be taken into consideration before deciding about the maintenance treatment. As there is lack of sufficient data about the maintenance treatment in children and adolescents, by extrapolating the data from adult literature, it is recommended that children and adolescents with two (if episodes are characterized by psychotic symptoms) or three episodes of depression, especially when associated with severe suicidality, severe dysfunction during the episodes, family history of affective disorders, and history of treatment resistance, should receive maintenance treatment.

The optimal duration of maintenance medication is not well established, and it can vary between 3 years and lifetime depending on risk factors.

Unless contraindicated, the psychotherapeutic or pharmacological treatments which were effective during the acute and continuation phase of treatment should be used for maintenance therapy. It is important to remember that there is lack of data on the long-term effects of antidepressants on the maturation and development of children. The risks and benefits of the use of antidepressants during the maintenance phase should be weighed against the possible consequences of relapses.

If maintenance-phase treatment is considered, then the children and adolescents may be monitored at least once a month to once in 3 months, depending on the clinical status, environmental stressors, level of functioning, and available social support.

DISCONTINUATION OF TREATMENT

In children and adolescents with first episode of depression, antidepressants can be tapered off at the end of continuation phase. Medications need to be discontinued slowly over a period of few weeks to avoid withdrawal symptoms. Fluoxetine has long elimination half-life, which is not true for most of the other antidepressants. Before considering tapering off medications, risk of relapse and recurrence, tapering schedule, and possible withdrawal symptoms which can arise during the procedure need to be discussed with the patient and the family. As the risk of relapse is very high during the first 8 months after stopping treatment, patients and family must be advised to follow-up every 2–4 months during this period. If there is re-emergence of symptoms, then previously effective treatment may be reinstituted.

MANAGEMENT OF CLINICAL FEATURES THAT REQUIRE SPECIAL ATTENTION

Suicidal ideation and/or suicidal attempts

Management of suicidality in children and adolescents requires proper assessment, monitoring, and resolution of the same. Patients, who are at a high risk of suicide, need to be managed as inpatients. If admission is refused or is not possible due to some reasons, then the family members and significant others should be advised to implement the high-risk management in the home environment. All potentially lethal agents, especially firearms and toxic medications, should be kept out of reach of the patient's access. If family conflicts are present, then family therapy can be considered. Proper psychoeducation and use of principles of CBT may be considered in patients who exhibit hopelessness and cognitive distortions. Antidepressants need to be considered if the depression is severe enough to cause significant impairment in patient's ability to participate in psychotherapy, or if the patient worsens or fails to improve with psychotherapy alone. ECT may be considered in patients with severe suicidality and those who have not responded to other modality of treatments.

Psychotic depression

Antipsychotics may be added to antidepressants in patients with psychotic depression. There is lack of data among adolescents which can specifically guide the selection of a particular antipsychotic. In general, atypical antipsychotics are preferred. However, it is to be kept in mind that use of antipsychotics is associated with an increased risk of tardive dyskinesia, weight gain, and hormonal changes. It is generally recommended that antipsychotics should be tapered off when the psychotic symptoms resolve. Presence of psychotic symptoms in depression is considered as an indicator of possible bipolarity; accordingly, clinicians should be alert to this possibility, particularly if antidepressants are prescribed.

Atypical depression

Data specific to the management of atypical depression in children and adolescents are not available. However, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are frequently used.

Treatment-resistant depression

If an adolescent presents with TRD, evaluation should include re-evaluation of the diagnosis; assessment of dose of antidepressants used in the past; length of drug trials with specific focus on the duration of use of the highest prescribed dose; length of psychotherapy; medication adherence; psychiatric comorbidity (anxiety, dysthymia, substance use, and personality disorders); comorbid medical illnesses; possible bipolar depression; and exposure to chronic or severe life events, such as sexual abuse, that may require different modalities of therapy. There is meager evidence to suggest that adolescents with TRD may respond to ECT.

Because of lack of data, several psychopharmacological strategies that have been recommended for adults with TRD may be extrapolated to children and adolescents too. Optimization (extending the initial medication trial and/or adjusting the dose) and switching to another agent in the same or a different class of medications, augmentation, or combination (e.g., lithium, T3) can be considered. Each strategy should be implemented in a systematic manner with proper psychoeducation of the patient and family members, and support to reduce the potential for the patient to become hopeless needs to be addressed.

Comorbid anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders or anxiety symptoms are frequent comorbid conditions among children and adolescents with depressive disorders, and treatment with SSRIs tends to address both sets of symptoms. It has been also reported that patients with comorbid anxiety disorders respond better to CBT.

Comorbid ADHD

Management of comorbid depression and ADHD can be very challenging, and selection of treatment modality is often guided by the relative severity of both the conditions. Psychostimulants may be used as the first-line agents if the ADHD is more severe than depression. If both set of symptoms improve with psychostimulants, then the same can be continued. However, antidepressants have to be considered in cases where depression does not respond to psychostimulants. Once depression improves with a SSRI, then it is advisable to re-evaluate the patient for ADHD symptoms and, if these are present, the patient should be managed according to the guidelines for ADHD. However, if depression is more severe than ADHD, then it should be addressed prior to ADHD. If both depressive and ADHD symptoms improve adequately, then the same treatment should be continued. If only depressive symptoms improve and ADHD symptoms continue, then the patient should be treated according to the guidelines for ADHD. Irrespective of the severity of depressive symptoms, psychosocial interventions must be carried out for both the disorders.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, et al. Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1427–39. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J. Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1575–83. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Keller M, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: The TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox GR, Callahan P, Churchill R, Hunot V, Merry SN, Parker AG, et al. Psychological therapies versus antidepressant medication, alone and in combination for depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD008324. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008324.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curry J, Rohde P, Simons A, Silva S, Vitiello B, Kratochvil C, et al. Predictors and moderators of acute outcome in the treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1427–39. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000240838.78984.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emslie GJ, Mayes T, Porta G, Vitiello B, Clarke G, Wagner KD, et al. Treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA): Week 24 outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:782–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09040552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emslie GJ, Ventura D, Korotzer A, Tourkodimitris S. Escitalopram in the treatment of adolescent depression: A randomized placebo-controlled multisite trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:721–9. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a2b304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Findling RL, Robb A, Bose A. Escitalopram in the treatment of adolescent depression: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013;23:468–80. doi: 10.1089/cap.2012.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming JE, Offord DR. Epidemiology of childhood depressive disorders: A critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:571–80. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghaziuddin N, Kutcher SP, Knapp P, Bernet W, Arnold V, Beitchman J, et al. Practice parameter for use of electroconvulsive therapy with adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1521–39. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000142280.87429.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Cox GR, Simmons MB, Merry SN. Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD004851. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004851.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hetrick SE, Merry SN, McKenzie J, Sindahl P, Proctor M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for depressive disorders in children and adolescents (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004851.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes CW, Emslie GJ, Crismon ML, Posner K, Birmaher B, Ryan N, et al. Texas children's medication algorithm project: Update from Texas Consensus Conference Panel on medication treatment of childhood major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:667–86. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a859b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennard B, Silva S, Vitiello B, Curry J, Kratochvil C, Simons A, et al. Remission and residual symptoms after short-term treatment in the treatment of adolescents with depression study (TADS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1404–11. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242228.75516.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luby JL, Heffelfinger AK, Mrakotsky C, Brown KM, Hessler MJ, Wallis JM, et al. The clinical picture of depression in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:340–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Guidelines for Depression in Children and Young People. 2005. [Last assessed on 2018 Jun 16]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/cG028 .

- 17.Reinecke MA, Ryan NE, DuBois DL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of depression and depressive symptoms during adolescence: A review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:26–34. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199801000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stark K, Rouse L, Livingston R. Treatment of depression during childhood and adolescence: Cognitive behavioural procedure for the individual and family. In: Kendall P, editor. Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive Behavioural Procedures. New York: Guilford; 1991. pp. 165–206. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do MT, Schwartz KT, Bolano C. Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46:11–43. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1220310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]