Abstract

The study of brown adipose tissue (BAT) has gained significant scientific interest since the discovery of functional BAT in adult humans. The thermogenic properties of BAT are well recognized; however, data generated in the last decade in both rodents and humans reveal therapeutic potential for BAT against metabolic disorders and obesity. Here we review the current literature in light of a potential role for BAT in beneficially mediating cardiovascular health. We focus mainly on BAT's actions in obesity, vascular tone, and glucose and lipid metabolism. Furthermore, we discuss the recently discovered endocrine factors that have a potential beneficial role in cardiovascular health. These BAT-secreted factors may have a favorable effect against cardiovascular risk either through their metabolic role or by directly affecting the heart.

Keywords: cardiovascular, diabetes, endocrine function, obesity

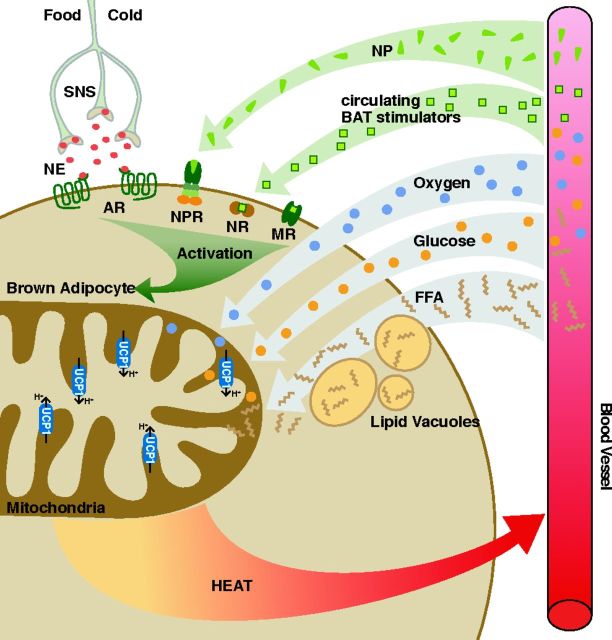

“nec pinguitudo nec caro” (neither fat nor flesh) is how Konrad Gesner described the appearance of a tissue type in marmots in 1551 A.D., known today as brown adipose tissue (BAT) (58). BAT oxidizes glucose and fatty acids (FA) to produce heat for thermoregulation (16), thereby increasing the body's energy expenditure, especially when it is stimulated in conditions of cold and possibly overfeeding (16, 152) (Fig. 1). Sympathetic nervous system activation with its associated norepinephrine release is a major contributor to the growth and stimulation of BAT (16), and BAT stimulation by natriuretic peptides has also recently been reported (12). In addition, other BAT stimulators such as thyroid hormone [triiodothyronine (T3)], retinoids, and BMPs have been described (182) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Activation of brown adipose tissue (BAT). Heat production via BAT occurs primarily through proton (H+) leak at uncoupling protein (UCP)-1 in the presence of oxygen. Glucose and free fatty acids (FFA) are consumed to provide reducing equivalents. Activation can occur via several pathways (presented in green). SNS, sympathetic nervous system; NE, norepinephrine; AR, adrenergic receptors; NP, natriuretic peptides; NPR, natriuretic peptide receptors; NR: nuclear receptors; MR, membrane receptors. *At this time, known activators include thyroid hormones, BMP7, BMP8b, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-21, orexin, irisin, and vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf).

Rodents possess a large well-delineated interscapular BAT depot, and its thermogenic ability has been documented for decades. Historically it was believed that in humans functional BAT only existed in infants, rapidly decreasing through childhood and disappearing in adulthood (31). Recently, the presence of functional BAT was demonstrated in adult humans, mainly in the supraclavicular and paravertebral spaces and adjacent to the neck vessels (32, 154, 177, 184, 204). As a result, the scientific interest in investigating the properties of BAT has markedly increased.

While the thermogenic properties of BAT are well known, recent evidence in mice and humans demonstrates that BAT has a role in regulating several components of cardiovascular health, such as vascular tone and systemic and cardiac metabolism (8, 25, 49, 167, 186). In particular, BAT activation increases lipid clearance and improves glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in mice (7, 167). In addition, BAT transplantation limits cardiomyocyte injury in mice (170), implicating that this tissue is cardioprotective. The present review will briefly summarize the histological and anatomical characteristics and thermogenic properties of BAT, then will discuss the current literature exploring novel functions of BAT (beyond thermogenesis) and supporting promising implications in the battle against cardiovascular disease.

BROWN ADIPOSE TISSUE: HISTOLOGICAL AND ANATOMICAL CHARACTERISTICS IN RODENTS AND HUMANS

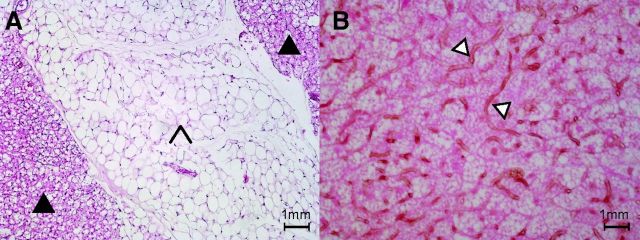

Brown adipocytes arise from specific adipogenic progenitors that are closer to skeletal muscle progenitors than to white adipocyte progenitors (158) [for a review, see Schulz and Tseng 2013 (157)]. Histologically, brown adipocytes characteristically contain multilocular fat droplets as opposed to the large unilocular fat vacuole present in white adipocytes (Fig. 2A). In addition, BAT is densely vascularized (98, 146) (Fig. 2B) and contains a large amount of mitochondria, resulting in a high iron and cytochrome content and a brownish color (16). The dense vasculature in BAT is thought to serve two purposes: increase the delivery of FA and glucose once BAT is activated and warm the blood passing through the BAT (98). The high mitochondrial content serves to drive the intrinsic oxidative capacity of BAT, associated with its thermogenic capacity. The numerous mitochondria in brown adipocytes are large and display laminar cristae, whereas they are small and elongated with randomly oriented cristae in white adipocytes (55). These differences reflect the different known primary functional roles of BAT and white adipose tissue (WAT), which are, respectively, heat production with energy dissipation and energy storage and distribution.

Fig. 2.

Histology of brown and white adipose tissue. A: filled arrow, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of brown adipose tissue; arrowhead, H&E stain of white adipose tissue. B: open arrow, lectin stain of capillary blood vessels in BAT (H&E counterstain).

In addition to “classical” brown adipose tissue, recent studies provide a strong indication for a recruitable BAT-like cell type expressing uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) in rodents and humans, referred to as beige or brite adipose tissue. Beige adipocytes are thought to be originating from multipotent preadipocytes located in various WAT depots (83) or from transdifferentiation of a white adipocyte into a beige adipocyte (27). These different ontologies are currently a topic of intense debate (161). In mice, beige adipocytes are interspersed with white adipocytes but can also be found in muscle (158, 193). Whether BAT in humans resembles classical brown fat or beige fat is a subject of extensive research; as the literature stands at present, some human depots have brown characteristics, whereas others are closer to beige adipose tissue (34, 38, 100, 160, 193, 197). Regardless of its location and developmental origin, the concept of inducible “browning” in human adipose depots has received considerable attention as a potential future therapy (8, 172, 173).

Brown adipose tissue has been most extensively localized in small laboratory rodents (rats, mice, hamsters), in which it abounds in distinct thoracic depots. In rodents, the interscapular and dorsocervical BAT depots are the largest, accounting for 50–60% of the total BAT mass and representing roughly 0.5–1% of body weight (29). The remainder is more dispersed throughout the body, localized in the abdomen and in the area around the kidneys (25% of total BAT in rats) (121, 165). Interscapular BAT is readily characterized by a consistent brown cellular appearance and can be precisely located and easily dissected for experiments; therefore, this tissue depot has been used in most rodent studies. The interscapular BAT depot in rodents is richly innervated, mainly by noradrenergic fibers, and is highly vascularized; blood leaves the interscapular BAT body through a large solitary vein (the Sulzer's vein) that takes it back to the right atrium via the azygos vein and the superior vena cava (37, 69, 146).

In newborn human infants BAT is relatively well defined and is found in the interscapular, axillary, posterior cervical, suprailiac, anterior mediastinal, and perirenal regions, taking on the form of a vest-like arrangement (1, 118). The BAT of human newborns is interspersed with WAT, and the amount of BAT gradually declines into adulthood (73, 93, 190). In adult humans, the anatomy of BAT is structurally less defined. Early anatomical studies identified the histological presence of BAT in humans (72, 76). However, it was only in 2007 that Nedergaard et al. were able to successfully show BAT activity in adult humans through retrospective analysis of nuclear medicine images of radiolabeled fluorodexyglucose ([18F]FDG) uptake in cancer patients (123). The main human depots are located in the supraclavicular and the neck regions, with some additional paravertebral, mediastinal, para-aortic, and suprarenal localizations, with an absence of interscapular BAT (reviewed in Ref. 123). Since then, the activity of human BAT has been well documented by using cold acclimation together with [18F]FDG positron emission tomography imaging (32, 154, 177, 184, 204). Other techniques are being developed to noninvasively detect human BAT, including ultrasound (6, 29, 51), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (14, 23, 24), and thermal imaging (169).

THERMOGENIC FUNCTION

BAT is an energetically active tissue, where nonshivering thermogenesis (NST) occurs. Thermogenesis without the locomotory impairments associated with shivering serves a critical function in the wild, and BAT has been classically identified in small mammals and newborns, and it is highly developed in hibernators.

Thermogenesis in BAT is accomplished via the 33-kDa UCP1 protein (62, 126). UCP1 activation increases inner mitochondrial membrane leak, uncouples electron transfer from ATP synthesis, and dissipates the proton motive force as heat. Although the UCP1 gene arose in an ancestral vertebrate, and is found in the genomes of fishes and marsupial mammals (e.g., Refs. 81 and 82), the adaptation of UCP1 for NST in a specialized tissue (BAT) is considered a key feature in eutherian evolution (e.g., Refs. 132 and 155).

The identification of functional BAT in adult humans, where homeothermy does not rely on BAT thermogenesis (19), shines a light on additional metabolic and biochemical roles for UCP1. Because it has a recruitable contribution to whole body metabolic rate and energy expenditure, BAT has received considerable attention as a potential therapeutic target for obesity via weight loss (26, 101), which is discussed later in this review.

Understanding the activation mechanisms for BAT thermogenesis is critical if we are to pursue its therapeutic uses. The ability of UCP1-ablated mice to survive cold challenge has raised the possibility that thermogenic mechanisms beyond UCP1 exist in BAT. Experimentation over the last two decades, including studies conducted on UCP1-ablated mice, strongly indicate that UCP1 uncoupling is the only mechanism of adaptive NST in BAT (e.g., Refs. 62 and 63). It is well established that proton leak via UCP1 is enhanced by long-chain FA and inhibited at rest by cytosolic purine nucleotides, mainly ATP (16). The central nervous system controls BAT activation via norepinephrine, which binds to adrenergic cell surface receptors. All three subtypes of β-adrenergic receptors (β1–3) are expressed in brown adipocytes (e.g., Ref. 150); however, their relative abundance varies by location and species (91). While rodents are known to signal NST via all three β-adrenergic receptors (see Ref. 4), the β3-receptor is most prominent in rodents (148), and it has therefore been the focus of the bulk of mechanistic investigations. Although the β1-receptor is generally more prevalent in humans, a marked induction of BAT by a β3-agonist has recently been shown (33). Ultimately, adrenergic stimulation of brown adipocytes enhances lipolysis in lipid droplets and releases FA, which overcome UCP1 inhibition in turn generating heat (16). The signaling pathway invoked by β-stimulation is mediated by cAMP, whose protein kinase targets include hormone-sensitive lipase. A variety of other BAT-specific activators that increase fatty acid availability to mitochondria have also been identified (see Ref. 182 for review), including thyroid hormones (112), retinoids (171), leptin (162), and natriuretic peptides that signal via cGMP (92).

Despite our increasingly clear appreciation of systemic physiological stimuli on BAT activation and NST, a consensus regarding the precise thermogenic mechanism of BAT, specifically the activation of UCP1 proton transport by long-chain FA, has remained elusive. Several mechanisms have been proposed (reviewed in Ref. 16), but, recently, Fedorenko et al., using patch clamping to study intact UCP1 in the inner mitochondrial membrane of BAT cells, demonstrated that UCP1 cotransports a FA anion for each proton released across the inner mitochondrial membrane (44). Long-chain FA are unable to dissociate from UCP1 until they are oxidized; therefore, they maintain H+ transport by shuttling within UCP1 (44). In the simplest model, one cytosolic fatty acid anion binds to UCP1, which can subsequently bind one proton. After cotransport across the inner mitochondrial membrane, the proton is released while the fatty acid anion remains bound by hydrophobic interactions in its tail. This anion returns to its original configuration and is able to initiate another proton transport. Our understanding of the UCP1 structure within the mitochondrial membrane also continues to expand. UCP1 was classically thought to exist as a dimer, but this idea has recently been challenged, when Lee et al. reported in 2015 that UCP1 is compositionally similar to the mitochondrial ATP/ADP transporter, existing as a monomer that binds a nucleotide with 1:1 stoichiometry. Like other mitochondrial transporters, UCP1 is stabilized by tightly bound cardiolipin (96).

BROWN ADIPOSE TISSUE AND CARDIOVASCULAR RISK FACTORS

Since the recent discovery of functional BAT in adult humans, augmenting BAT-induced thermogenesis by increasing the amount of BAT and/or by stimulating BAT has been considered as a potential therapy for obesity (173), thereby potentially decreasing cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Additional evidence supports beneficial properties of BAT on vascular tone, and lipid and glucose metabolism. Finally, novel studies suggest that the properties of BAT may rise above a reduction of risk factors and include the release of systemic cardioprotective factors.

BAT and Obesity: Rodents and Humans

Rodents.

MORPHOLOGY, HISTOLOGY, AND FUNCTION OF BAT IN OBESE RODENTS.

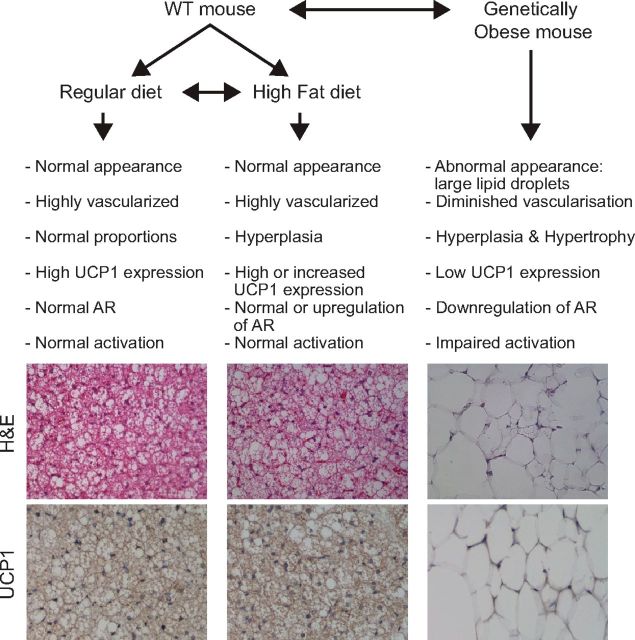

BAT morphology and function has been investigated in several animal models at baseline or under conditions of obesity. Obesity is typically achieved by providing high-caloric diets in the presence and absence of genetic models of obesity (Ob/Ob mice and Db/Db mice) (see Ref. 88 and references herein). BAT histology and vascularization were found to be similar in wild-type (WT) mice housed at room temperature or thermoneutrality and fed either a normal chow or a high-fat diet (HFD) from 2 to 19 wk (longer periods not studied) (29, 67, 117). However, high-caloric diet typically led to an increase in total (interscapular) BAT mass as a result of hyperplasia (29, 67, 117, 195).

In genetic models of obesity a different BAT phenotype is present: although the overall BAT mass is increased, BAT has a significantly different appearance in DB/DB or Ob/Ob mice compared with their WT littermates. Indeed, Db/Db and Ob/Ob brown adipocytes are larger than those of WT mice, unilocular, and UCP1 negative for most cells. In addition, Db/Db BAT is less vascularized compared with WT BAT (29).

BAT functionally also dramatically differs in models of diet-induced obesity vs. genetic obesity (Fig. 3). Typically, thermogenic capacity and energy expenditure are preserved in models of increased caloric intake (89, 125), arguably accompanied by an increase in UCP1 expression in BAT (54). In contrast, in genetically obese animals, BAT activation is impaired not by intrinsic deficiencies of the BAT itself, since BAT is present and functional in these animals (15), but because of secondary problems that may include a lack of leptin secretion and a downregulation of β1- and β3-adrenergic receptors in the BAT of these mice. Indeed both leptin and β-adrenergic stimulation are direct activators of BAT thermogenesis (17, 148, 174). As a consequence, induction of UCP1 is impaired in genetically obese mice.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of the influence of diet-induced or genetic obesity on BAT in mice.

In models of diet-induced obesity two questions arise: 1) does eating a high-caloric diet lead to an intrinsic increase in BAT activity to maintain a net neutral energy balance, i.e., the concept of diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT); and 2) can obesity as such be reversed by increasing BAT-induced thermogenesis.

The answer to the first question is a matter of debate [see the perspectives by Kozak et al. (89) and Nedergaard and Cannon (125)] and is less salient to the topic of this review.

The second question, however, directly relates the function of BAT thermogenesis to the regulation of body weight. Several independent studies have shown that activation of BAT (by cold sympathetic agonists or a direct action on brown adipocytes), concomitant with an increase of beige fat cell in WAT depots, can successfully increase energy expenditure and/or diminish adiposity in diet-induced obese animals (reviewed in Refs. 11, 125, and 194). However, these experiments are complex to interpret, since the stimulation of BAT may elicit multiple side effects. Furthermore, the processes underlying the role of BAT and UCP1 in weight homeostasis are complex and may involve not only signaling in brown and beige adipocytes but also an interplay between BAT and other organs, including, but not limited to, the sympathetic nervous system, liver, muscle, and WAT. These topics have been extensively reviewed by others (17, 41, 88, 89, 108, 125, 200). Of note, three recent reports elegantly demonstrated the capacity of transplanted functional BAT to limit obesity in both high-fat diet-induced obesity (107, 203) and in genetic models (Ob/Ob) of obesity (106). Again, the mechanism by which the limitation of weight gain or reversal of obesity was achieved was not straightforward, since beneficial effects were observed systemically and in other tissues. Decreased liver steatosis, increased circulating adiponectin, increased β3-adrenergic receptor and fatty acid oxidation gene expression in WAT, and enhanced sympathetic activity were detected after BAT transplantation and could contribute to the weight loss or lack of weight gain (106, 107, 203).

ALTERATIONS IN BAT'S THERMOGENIC CAPACITY HAVE A DIRECT INFLUENCE ON OBESITY.

Strikingly, many of the alterations in thermogenic capacity have a direct influence on body weight in mice. These alterations can be induced either by genetic deletion, by overexpression of genes involved in thermogenesis [see references in the discussion of Anunciado-Koza et al. (3)], or by direct transplantation of functional BAT (106, 107, 203). The first model of dysfunctional BAT was the UCP1-diphteria toxin A chain (DTA) transgenic mouse. UCP1-DTA mice have ∼60% of their brown adipocytes ablated by expression of diphtheria toxin under the UCP1 promoter. UCP1-DTA transgenic mice fed a regular chow diet became obese and insulin resistant (110). However, at older age, UCP1-DTA mice were also hyperphagic (enough to explain the obesity) at ambient temperature and were still able to maintain a normal body temperature when exposed to 4°C for 50 h (68). Surprisingly, raising the UCP1-DTA mice at thermoneutrality prevented the hyperphagia and obesity (116). It was concluded that both the obesity and the hyperphagia of the UCP-DTA mouse are temperature dependent, apparent only when the mouse lives at a temperature below thermoneutrality, when BAT thermogenesis is switched on. Thus, although the observations in UCP1-DTA mice pointed to a role of BAT in obesity, the data were not conclusive.

The adipocyte protein 2 (aP2)-UCP1 mouse was generated to study the role of an increase in UCP1 expression. In the aP2-UCP1 mouse, the UCP1 expression is driven in BAT and WAT by the fat-specific constitutively regulated aP2 promoter. In agreement with the expected results, mice that were partially deficient in UCP1 (heterozygous aP2-UCP1 mice) were found to be resistant to obesity. The constitutive expression of UCP1 under the aP2 promoter maintained the mitochondria in an uncoupled state and led to resistance to both diet-induced and genetic obesity (87). The resistance to obesity in these mice was consistent with the hypothesis that thermogenesis from elevated expression of UCP1 reduces adiposity. Interestingly, mice homozygous for the aP2-UCP1 transgene were found to have a 90% reduction in BAT mass. This decrease was attributed to UCP1 toxicity mediated by excessive uncoupling. These mice were also obesity resistant but, in contrast to the heterozygous mice, were cold sensitive (168). These findings suggest that even 10% of BAT remaining with an increase in UCP1 expression is sufficient to protect from obesity. While later studies on UCP1-deficient (UCP1−/−) mice provided a more definite picture, a clear correlation between energy efficiency and the presence of BAT and UCP1 was now established.

More recently UCP1−/− mice (42) have allowed investigators to better define the functions of UCP1. In isolated mouse BAT cells, thermogenesis is fully dependent on UCP1 (114). Thermogenesis measured in UCP1−/− mice by exposing them to cold is, surprisingly, only mildly impaired (119), suggesting that compensatory thermogenic mechanisms play an important role in vivo. Investigators have speculated that multiple tissues participate in the thermogenesis induced by cold exposure in UCP1−/− mice (119). These compensatory thermogenic mechanisms may be responsible for the lack of obesity (and even a resistance to obesity) observed in several studies of UCP1−/− mice (3, 42, 86, 105). While these studies were performed at room temperature, a cold environment for mice, Feldmann et al. recently demonstrated that UCP1−/− mice have impaired thermogenesis and develop obesity even on a normal diet when placed in a thermoneutral environment (around 30°C in mice) (45). These latter results emphasize the inverse correlation of functional BAT and obesity.

In summary, there is a consensus that increasing and activating BAT or UCP1 is likely to be an efficient way to prevent or ameliorate obesity at least in mice. The mechanisms by which BAT activation limits obesity are complex; the ability of BAT to beneficially influence adiposity is not only dependent on the intrinsic expression and activity of thermogenic genes in the brown adipocytes, but also on a fine and reciprocal cross talk between BAT and many other tissues.

Humans.

HOW MUCH ENERGY DOES BAT CONSUME?

In humans, the amount of BAT is estimated to be around 50–100 g (176, 184). This approximates 0.1% of body weight, a percentage five to ten times lower than that of the mouse. In rodents, calculations estimate that BAT contributes up to 60% of the resting metabolic rate (RMR) upon cold exposure, and it is likely that BAT is the only tissue responsible for classical NST (16, 45, 176). In humans a significant correlation between cold-induced BAT activity and NST has been shown (5, 175), however, a deduction of the contribution of BAT to the RMR is not straightforward due to: 1) the respective over- and underestimation of the BAT volume by positron emission tomography (PET) or computerized tomography (CT) scans measuring glucose uptake; 2) the fact that glucose uptake might underestimate BAT activity, since intracellular triglycerides have been demonstrated to be the main source of energy for acute BAT-induced thermogenesis (138); 3) the nonhomogeneity of human BAT tissue (a mix of white and brown/beige fat cells); and 4) the assumption that the maximal heat-producing capacity of human BAT is 300 W/kg (152) is based on measurements in small mammals while large mammals typically have lower metabolic rates. Estimations that take into account these limitations estimate a contribution of 2.5–7% of RMR in humans (95, 184). The recent study by Ouellet et al. illustrates the potential important effect of BAT in humans by showing that stimulation of BAT in healthy volunteers for 3 h augmented oxygen consumption by 80% (138), of which 40% was attributed to NST by BAT. Thus, the actual cold-stimulated contribution of BAT to RMR may be higher. Concretely this would mean that, if BAT were to be chronically stimulated, it would consume several kilograms of fat per year (184).

Recently, different experiments in humans were undertaken in which attempts were made to activate BAT by cold or pharmacologically induced enhanced sympathetic outflow and look at effects on body weight/fat mass. Yoneshiro et al. reported that, when healthy young adults were acclimated to 17°C for 2 h/day during 6 wk, fat mass was reduced by 5%, whereas no change was observed in the control group (198). In contrast, Van der Lans et al. reported no changes in RMR, body weight, and plasma glucose and lipid levels in healthy young adults acclimated to 15–16°C for 6 h/day during 10 days (175). Interestingly, increased sympathetic output by stimulation of the transient receptor potential channels (TRP) with capsaicin also increased energy expenditure more and reduced fat mass in subjects with detectable BAT compared with subjects without detectable BAT (198). Thus, whether cold acclimation is a novel tool to improve obesity remains an active subject of investigation (28).

RELATIONSHIP OF BAT AND OBESITY IN HUMANS.

Functional BAT can be detected upon stimulation in >50% of adults, depending on the age, gender, adiposity, and thermal environment (30, 32, 139). Young lean women were shown to possess BAT most frequently (30). In contrast, several groups reported a blunted [18F]FDG uptake increase in the BAT in response to cold and insulin in obese patients, suggesting that BAT function is impaired in these individuals (136, 154, 177). Similarly, [18F]FDG uptake was found to be inversely correlated to parameters of central obesity (187, 188), to body mass index (BMI), and to the total percentage of body fat (177, 181). Another study showed that single nucleotide polymorphisms of the genes for UCP1 and β3-adrenergic receptor, key mediators of BAT thermogenesis, were associated with an age-related decline of BAT activity and accumulation of body fat in humans (199). These inverse correlations have been interpreted as suggesting BAT dysfunction in obese subjects. A different interpretation, however, is that the increased subcutaneous WAT layer in obese subjects functions as a thermal insulator, thus making NST redundant and resulting in a lower BAT activity (181). In conclusion, the recent studies in human subjects suggest a negative correlation between obesity and levels of BAT activity. These findings open the discussion for the future investigation of two different hypotheses: 1) will activating BAT be an actual cure for obesity, and 2) does reduced BAT activity predispose to obesity in certain individuals.

Effects of BAT on Metabolism (Glucose, Insulin, Triglycerides)

Fatty acids derived from triglycerides (TG) are the main energy source for BAT thermogenesis (16). The activation of brown adipocytes leads to lipolysis of the intracellular TG-filled lipid droplets by adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and the subsequent release of FA. These FAs serve two purposes: 1) they are metabolized by β-oxidation enzymes in the mitochondrial matrix; and 2) they activate UCP1, which then generates heat by initiating a futile electron transport cycle using the electrons derived from β-oxidation (16, 96). Subsequently, replenishing of the intracellular TG stores happens in three ways: 1) uptake of albumin-bound free fatty acid (FFA), 2) uptake of FA from plasma very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and chylomicrons, and 3) glucose uptake followed by de novo lipogenesis (7, 16, 47, 85). Glucose uptake by BAT is mediated by both insulin-dependent and insulin-independent mechanisms. Glucose is also used by BAT for ATP generation (e.g., via glycolysis) (16, 90).

The high metabolic capacity of BAT for TG clearance in mice was shown in a recent study by Bartelt et al. Cold-activated BAT reduced TG-rich lipoprotein plasma concentrations in lean mice and was able to correct hyperlipidemia in hyperlipidemic apolipoprotein A5 knockout (KO) mice (7). In contrast, surgical denervation of BAT led to hypertriglyceridemia in mice (40).

Brown adipose tissue also plays a role in glucose metabolism. Cold activation normalized glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in obese mice fed high-fat diets (7). Similarly, transplantation of BAT increased glucose tolerance and decreased insulin resistance in aging and obese mice (106, 167), and increased glucose tolerance in UCP1 KO mice (170). Furthermore, long-term treatment with β3-adrenergic agonist or thyroid hormone, both recognized BAT activators, lowers plasma lipid and glucose levels (141, 189); UCP1 overexpression improves insulin sensitivity in rodents (145); induction of white adipose tissue browning by different recently identified “BATokines” improves glucose tolerance (13, 120, 156); and genetic models with increased BAT volume or activity have favorable metabolic parameters (61, 111, 137, 159). These findings underscore the involvement of BAT in total energy expenditure, TG clearance, and glucose/insulin handling, at least in mice.

Recent data seem to indicate that some of the effects of BAT on metabolism in mice may also be extrapolated to humans. In healthy volunteers, [18F]FDG-positive BAT volume and the cold-induced increase in BAT radiodensity were associated with an increase in systemic FA turnover (9). Ouellet et al. reported that exposing human volunteers to 2 h of mild cold (reduction of skin temperature by 2.5°C) resulted in enhanced FA uptake by BAT compared with muscle and WAT. The FA consumed by BAT was thought to originate mostly from the intracellular TG stores in BAT (138). This hypothesis is in analogy to necropsy reports from newborn infants and adults who died from hypothermia, in which a depletion of intracellular lipid in BAT was found (1). Whether BAT also uses FA from circulating lipids is not known. Bakker et al. did not find an acute lowering of plasma TG in human subjects after short-term cold exposure but did report increased fat oxidation in the absence of glucose oxidation in BAT (5). These results suggest that acute BAT activation may initially rely on catabolism of intracellular TG stores (5). Likely, prolonged BAT activation will result in increased TG clearance from the plasma, but this has not yet been studied.

The capacity of human BAT to take up large amounts of glucose at thermoneutrality and the rapid adaptation of this uptake after BAT stimulation have been well documented by [18F]FDG uptake measurements. Brown adipose tissue can contribute to glucose homeostasis even without BAT stimulation by its involvement in the clearance of plasma glucose (i.e., for de novo lipogenesis) (25, 167). Orava et al. provided the first indications that BAT [18F]FDG uptake represents the oxidative capacity of unstimulated BAT and showed that cold activation of BAT led to a 12-fold increase in glucose uptake by BAT accompanied by a doubling of blood flow in BAT (135). In addition, insulin induced a fivefold increase in BAT glucose uptake (135). The expression of insulin-sensitive glucose transporter GLUT4 was higher in BAT vs. WAT, underlining the insulin sensitivity of human BAT (135). Whether uptake of glucose is mainly mediated via the GLUT1 or GLUT4 transporter remains to be determined. The oxidative capacity of cold-activated human BAT was confirmed later by several groups showing increased oxidative metabolism by triple-oxygen scans (H215O, C15O, and 15O2) as well as measurements of daily energy expenditure in healthy individuals with high BAT vs. low BAT volumes (10, 122, 138).

The potential impact of BAT on glucose metabolism was underlined by a study showing that the presence or absence of BAT in healthy humans was a determinant of glucose and HbA1c levels independent of body weight (113). Also, the clearance of circulating glucose by BAT after cold exposure in insulin-resistant individuals was shown to be lower compared with insulin-sensitive individuals (136, 177, 181). Finally, the presence of type 2 diabetes was independently associated with a lower prevalence of detectable BAT (32, 139, 154). Another interesting observation was that increased risk of South Asian populations to develop type 2 diabetes at a lower age and at a lower BMI compared with Caucasians was correlated with a lower BAT activity in these populations (5). Thus, based on these correlations one might speculate that, in humans, a reduced activity of BAT may predispose to type 2 diabetes not only by increasing obesity but also through a direct prodiabetic mechanism, for example, a reduced glucose uptake in BAT (124). However, diabetes or obesity by themselves might also decrease BAT activity (124). Further studies will be necessary to solve the temporal relationship of these events.

Several recent studies have attempted to prove that BAT activation increases insulin sensitivity in humans. In an important report, Chondronikola et al. showed that BAT activation by cold exposure (5–8 h) in healthy lean volunteers with high amounts of activated BAT directly increased RMR, increased whole body glucose disposal, increased plasma glucose oxidation, and increased insulin sensitivity (25), whereas it had no effect in subjects with low amounts of activated BAT. Prolonged cold exposure (10 days) also markedly increased peripheral insulin sensitivity (43%) in subjects with diabetes (70). In these latter individuals, however, cold acclimation induced only a minor increase in BAT glucose uptake. These findings may suggest that other tissues (in particular muscles) are responsible for the increased insulin sensitivity after cold exposure in subjects with diabetes. A second intriguing possibility is the idea that BAT releases endocrine factors or BATokines. Some of these BATokines, produced either constitutively by BAT or only by activated BAT, might have the capacity to engage other tissues in, for instance, insulin sensitization (186). For now, the question remains whether long-term BAT activation can indeed improve glucose metabolism in obese subjects with impaired glucose tolerance or insulin resistance and continues to be an interesting and relevant topic for future studies.

PERIVASCULAR ADIPOSE TISSUE: EFFECT ON VASCULAR TONE AND ON THE HEART

Perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) surrounds most vessels in the body, except the cerebral circulation (57), and has been described in both mice and humans. These depots have varied morphological and functional characteristics depending on their location (20, 27). Importantly, perivascular depots share many characteristics of BAT, including multilocular lipid droplets, high mitochondrial density, and high levels of UCP1 expression (reviewed in Ref. 20). Perivascular depots are also thermogenic, maintaining intravascular temperature in mice (21) and most likely in humans [as suggested by the data of Robinson (149)]. Yet, PVAT has also been described as a mix of WAT and BAT depending on location within the body (153). Despite near complete overlap of gene expression patterns between PVAT and BAT in mice (50), a mouse model that does not develop PVAT still retains WAT and BAT, indicating that these tissue types arise distinctly (reviewed in Ref. 20). Nevertheless, adipose tissue in general is recognized as an active endocrine tissue; the proximity of PVAT to underlying vascular tissues enables our observation of local paracrine and endocrine effects (43). There is increasing interest in understanding the interrelationship between this UCP1-expressing tissue and cardiovascular (patho)physiology.

Perivascular adipose surrounding the coronary arteries is termed epicardial adipose tissue (EAT). Unfortunately, the nomenclature applied to adipose depots co-occurring with the heart and coronary vasculature is not always clear, making it difficult to properly compare differences and similarities (49). Coupled with the fact that mice do not have epicardial fat, it has been difficult to ascertain unique mechanistic details among adipose depots and to separate the specific role of EAT. EAT is clearly an active tissue that displays high rates of lipid deposition and lipolysis. It also exhibits high UCP1 expression, and a protein profile generally similar to beige adipocytes, but has larger unilocular lipid deposits (153).

Until recently, mechanistic experimental work studying the properties of PVAT has been performed primarily ex vivo, and we have lacked the correct animal models to study regulation in complex whole organism systems. However, multiple results do identify a secretory vasoactive role for PVAT that has been the subject of several recent reviews (2, 20, 49). As early as 1991, PVAT was shown to promote vasorelaxation of aortic rings in vitro (166). In lean rodents and humans, healthy PVAT secretes a number of vasorelaxing factors that appear able to modulate local blood pressure, particularly in the microvasculature (see also Ref. 75 for review). Examples of identified PVAT vasodilators include adiponection (48, 196), prostacyclin (21), palmitic methyl ester (97), and the gasotransmitters hydrogen sulfide (192) and nitric oxide (56).

The similarities of PVAT to BAT appear to play a role in PVAT's beneficial effects on vascular tone. Indeed, the UCP1 content of peripheral adipose tissues is directly correlated with blood pressure in humans (99). A correlation between reduced UCP1 expression in perirenal adipose tissue and hypertension has been demonstrated in patients of both genders, persisting even after age and BMI matching (99). Furthermore, a minor allelic difference in UCP1 is associated with obesity and blood pressure outcomes in women (39).

The nuances of PVAT's contribution to vascular tone over a range of pathophysiological conditions, and even in healthy volunteers, remain unclear. Overall, it is suggested that healthy PVAT enhances endothelial-dependent and -independent vasorelaxation and is modestly anti-inflammatory (49, 75). Importantly, however, PVAT also produces vasoconstrictive factors, such as reactive oxygen species and angiotensin (reviewed in Ref. 75), suggesting a more complex regulatory role. Indeed, a recently developed mouse model without perivascular adipose tissue is actually hypotensive (21).

The influence of PVAT and EAT on the development of atherosclerosis is likewise controversial. Recent work in mice lacking PVAT demonstrated worsening of atherosclerosis following a high-fat diet (21). Additional evidence suggests that PVAT at thermoneutrality is proatherosclerotic in these mice, but, when PVAT is activated by cold, serum triglycerides are reduced, and atherosclerosis development is slowed, despite high-fat feeding (21). On the other hand, the amount of EAT around the coronary vessels correlates positively with plaque size in coronary atherosclerosis patients (179).

Like other fat depots, PVAT expands with obesity and diabetes (64). Under these conditions, PVAT and EAT appear to alter their regulatory role toward the underlying vasculature, transitioning from protective under lean healthy conditions to damaging in obesity, diabetes, and weight gain (64). In obesity, PVAT contains more inflammatory cells (e.g., macrophages) and secretes less anti-inflammatory substances such as adiponectin and more proinflammatory adipokines such as leptin, resistin, angiotensinogen, cytokines including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and reactive oxygen species [reviewed by Fitzgibbons and Czech for humans and mice (49)]. A shift to a proinflammatory phenotype, underlain by reduced adiponectin and increased cytokines in adipose tissue, is also the most obvious result of a high-fat diet [e.g., Chatterjee et al. (22)]. This altered profile of adipokine/cytokine production in PVAT may contribute to increased hypertension and atherosclerosis. As an example, inflammatory signaling induces nitric oxide synthase-2, resulting in unregulated nitric oxide production and peroxynitrite formation, which directly induces vasoconstriction (49). The link between PVAT and atherosclerosis outcomes is likely also related to the degree of inflammatory signaling produced in adipose tissue (reviewed in Ref. 180). Mechanistically, it has been hypothesized that adipose inflammation is relevant to plaque formation via recruitment and proliferation of myofibroblasts and a contribution to vascular remodeling (134). Adipose tissue can also release hepatocyte growth factor, which increases with increasing PVAT mass (147).

EAT also becomes dysfunctional as a result of obesity, displaying reduced adiponectin secretion and fatty acid uptake (49). Adiponectin produced by EAT is able to regulate local blood flow (35), and it is reduced in the EAT of patients with coronary artery disease (77). There is also evidence that EAT has a stronger proinflammatory phenotype in patients with coronary artery disease compared with other peripheral adipose depots (115). As with other PVATs, EAT presents a less inflammatory phenotype in lean vs. diabetic patients (reviewed in Ref. 78). It has been difficult to define a causative role for EAT in inflammation based on observed biochemical differences under obesity because the amount of EAT correlates with the volume of visceral adipose tissue, which is an important confounder of cardiovascular disease (reviewed in Ref. 49). It generally appears that EAT presents no additive cardiovascular disease risk beyond that associated with increased visceral fat in the same patients and that volume-independent beneficial paracrine effects can be exerted by healthy EAT on coronary calcification and cardiac dynamics (49).

BROWN ADIPOSE TISSUE AS AN ENDOCRINE ORGAN: NOVEL PERSPECTIVES (IN PARTICULAR POTENTIAL EFFECTS ON THE HEART)

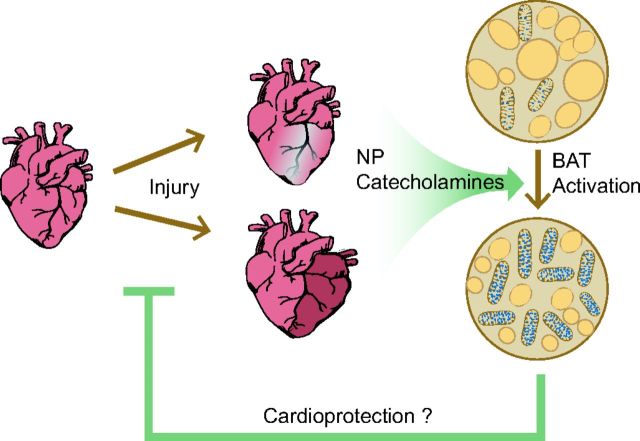

In addition to the direct role that BAT plays in influencing metabolism, as described earlier, recent research has uncovered a potential role for BAT as an endocrine mediator. Brown adipose tissue secretes multiple molecules (for a review see Ref. 183), the so-called BATokines. These molecules may then alter physiology by autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine mechanisms, thus modifying BAT itself or acting remotely on other systems. The endocrine profile of BAT appears to be distinct from that of WAT. The currently known autocrine and paracrine factors that are secreted by BAT and that have a direct effect on the BAT or its surrounding tissue have been reviewed extensively (60, 95, 144, 185). We will focus mainly on the endocrine factors that may have a beneficial role in cardiovascular health by improving systemic metabolism or by directly affecting the heart (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Hypothesized effect of BAT on the heart after injury. Cardiac injury leads to the systemic production of natriuretic peptides (NP) and catecholamines, which induce the activation of BAT. Activated BAT may have an indirect cardioprotective effect through metabolic improvements and/or a direct cardioprotective action through the systemic release of cardioprotective BAT-secreted adipokines.

Several reports using transplantation of BAT in rodents have shown beneficial effects on metabolism and cardiovascular outcomes and can be explained by the release of endocrine factors. For instance, BAT transplantation reversed the glycemic symptoms of two different models of type 1 diabetes without a change in insulin levels (65, 66). IGF-I, a molecule secreted by BAT into the circulation, was put forward as the potential mediator of these effects (65, 66). In addition, in 2013 both Stanford et al. and Liu et al. reported that adult BAT transplantation could reverse metabolic abnormalities in high-fat diet-induced or Ob/Ob insulin-resistant obese mice (107, 167) (and the weight gain as previously discussed). In the study of Stanford et al., IL-6 and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-21 were identified as the potential BATokines mediating the beneficial metabolic effects; these secreted factors will be discussed in more detail below. Finally, our team demonstrated that transplantation of wild-type BAT could prevent the increase in cardiomyocyte injury observed in catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy in UCP1 KO mice (170). This finding suggests the important hypothesis that the presence of functional BAT mediates cardioprotection. In summary, BAT transplantation studies confirm the ability of BAT to produce systemic signals that can decrease cardiovascular risk by either positively influencing metabolism or by directly acting on and protecting cardiomyocytes. In addition, these studies show that relatively small amounts of BAT may have significant systemic effects.

Recent secretome analysis of BAT confirmed the existence of a distinct set of BAT-enriched secreted factors (109, 186). Further studies are needed to demonstrate that these factors are solely secreted by BAT. Below we give an overview of potential BATokines that might have a cardioprotective role via either direct cardiac action or via improving metabolism (Table 1).

Table 1.

BAT secreted factors with potential direct cardiac actions and/or acting on metabolism

| BAT Secreted Factor | Actions | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|

| Thriiodothyronine | Improved metabolic parameters | 79, 102 |

| Cardioprotective | 53, 128 | |

| Chronotropic | ||

| Fibroblast growth factor-21 | Improved metabolic parameters | 59 |

| Antihypertrophic | 143 | |

| Cardioprotective | 103 | |

| Neuregulin 4 | Decreased insulin resistance | 186 |

| Cardioprotective | 104 | |

| Interleukin-6 | Improved metabolic parameters | 167 |

| Acute cardioprotection | 52 | |

| Long-term maladaptive remodeling | 52 | |

| Nerve growth factor | Prosurvival in ischemia | 18, 191 |

| Improves cardiac function | 202 | |

| Free fatty acids | Improved metabolic parameters | 201 |

BAT, brown adipose tissue.

The first known endocrine factor secreted by BAT was the active thyroid hormone T3 (163). T3 is produced by the type II thyroxine 5′-deiodinase (DIO2)-mediated conversion of the prohormone thyroxine (T4). Although the DIO2 is not solely expressed in BAT, a significant upregulation of the enzyme was observed after BAT activation concomitant with a detectable increase of T3 levels in plasma (46, 163, 164). Thyroid hormones have gained interest in the field of cardioprotection since they were shown to exert strong cardioprotective effects in both humans and animals (for a review, see Refs. 53 and 128) despite their deleterious chronotropic effect (178). The active cardioprotective role of BAT-mediated T3 production is uncertain since T3 is produced by several other tissues (36).

FGF21 is secreted by cold-activated BAT (74, 94). FGF21 exerts pleiotropic beneficial effects on lipid and glucose metabolism in mice and humans (59) and was identified by Stanford et al. as a candidate endocrine factor released by transplanted BAT (167). FGF21 is considered a promising new therapy to lower obesity and associated disorders, both by activating BAT and by acting on WAT and the liver (for a review, see Ref. 59). Importantly, FGF21 was recently reported to have both antihypertrophic and cardioprotective actions on the heart in animal models of hyperthophy (143) and ischemia (103), respectively. It must be noted, however, that the secretion of FGF21 is not specific to BAT; other tissues, including liver (129) and skeletal muscle (80), also release FGF21 in the circulation. Additionally, it is unlikely that FGF21 is the factor responsible for cardioprotection in the transplantation model since, in analogy with a recent report by Keipert et al. (84), we observed an increase of FGF21 in UCP1−/− mice (unpublished data) while these mice displayed increased levels of cardiomyocyte injury (170). Nevertheless, FGF21 remains an emerging target for the treatment of hypertrophy and ischemic injury of the heart.

Neuregulin 4 (Nrg4) was recently identified as a BATokine that is strongly induced during brown adipogenesis (186), but also by adrenergic receptor (cold)-induced BAT activation (151, 186). Studies in mice demonstrated that Nrg4 protects against diet-induced insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis through attenuating hepatic lipogenic signaling (186). Nrg4 was also shown to stimulate neurite outgrowth of PC-12 cells, suggesting that it might induce increased neuronal growth in BAT (151). Finally, a single report identified Nrg4 as a molecule secreted by the liver in a myocardial ischemia model. In this study, Nrg4 had cardioprotective effects against myocardial ischemic injury when administered to mice (104). However, the possibility of BAT secretion was not verified in this study and whether Nrg4 might be sufficiently released by BAT under conditions of cardiomyocyte injury to provide cardioprotection is unknown.

IL-6 is a well-characterized proinflammatory cytokine that is produced by many tissues upon inflammatory triggers. In addition, IL-6 signaling mediates glucose metabolism and energy balance: IL-6 KO mice develop diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance, whereas chronic activation of IL-6 signaling increases energy expenditure and promotes browning of WAT in cancer-induced cachexia (140, 142). The improvements of glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity attributed to BAT transplantation were abolished when BAT from IL-6 KO mice was transplanted (167), suggesting that IL-6 mediated the beneficial effects of BAT transplantation. It would be interesting to elucidate the endocrine significance for metabolic homeostasis of IL-6 secreted by BAT. However, because of its complex signaling and nonspecific production by many tissues, the therapeutic relevance of IL-6 seems unlikely (140). In addition, IL-6 was shown to have a dual role in cardioprotection, having an acute cardioprotective effect in heart failure but contributing to maladaptive remodeling and contractility in the heart after long-term exposure (52).

Nerve growth factor (NGF), a growth factor known to promote survival and proliferation of neurons, is produced by BAT (127). NGF typically signals through its receptors to promote sympathetic axon growth and the innervation of target tissues. One could therefore hypothesize that NGF signaling may establish and/or remodel sympathetic innervation of BAT, and thus affect metabolic homeostasis. However, this hypothesis has not been investigated to date. In a diabetic setting, hyperglycemia attenuates NGF production by endothelial and neural cells, leading to the degeneration of cardiac nerves and worsening of cardiac function (131). NGF exerts prosurvival activity in ischemic cardiomyocytes and isolated perfused hearts (18, 191) and improves cardiac function in diabetic isolated perfused hearts (202). However, the expression of NGF in BAT appears to be reduced after BAT activation (130), and thus a cardioprotective role in response to activation is unlikely.

Upon BAT activation by cold or adrenergic signaling, FFA are released by lipolysis of stored TG. These FFA not only provide an important source of energy but can also activate tissue-specific FFA receptors, which are a class of G protein-coupled receptors that can elicit metabolic responses in a variety of tissues (71, 133). It was recently shown that certain adipocyte-specific branched FA represent a new class of biologically active lipids that improve glucose tolerance and reduce adipose tissue inflammation in obesity (201). However, to date information regarding the secreted FFA profile of BAT is absent. The further study of BAT-specific metabolomics is an interesting research topic and may yield potential new mediators between BAT and other tissues.

In summary, accumulating evidence suggests that BAT has an endocrine role. Recently, an increasing number of endocrine factors released by (activated) BAT are being identified. The function of BAT might thus be strikingly more complex than merely a biological tool for energy expenditure and thermogenesis. It is currently projected that the majority of potential BATokines have not yet been discovered, nor are their target organs, tissues or cells, mechanism of action, or signaling cascades known. Given the renewed interest in BAT since its rediscovery in adult humans, BAT activation and BATokines are potentially promising tools for clinical treatment of cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, decreased glucose tolerance, and increased insulin resistance.

In a recent study in our laboratory we have provided indication that BAT is activated in a model of catecholamine-induced injury (170). Recent data (unpublished) from our group suggest similar activation in models of cardiac ischemia in mice. Importantly, we also discovered that BAT exerts a systemic cardioprotective action in models of catecholamine-induced injury in mice leading to decreased myocardial injury, fibrosis, and left ventricle adverse remodeling (170). This cardioprotective effect could be due to systemic actions of BATokines or occur through systemic improvements in metabolism. If such a cardioprotective effect can be extended to other models of heart failure, BAT activation or transplantation may show promise as novel therapeutic avenues.

While this review brings forward the concept that BAT contributes to reduction of cardiovascular risk and myocardial protection, there are many aspects that remain to be addressed. To date, no BAT-related therapies have been reported in humans, likely because most of the ongoing research is still in the discovery and preclinical phase. The recent recognition of functional brown/beige fat in adult humans raises the prospect that brown fat abundance and/or function may be augmented to restore energy balance in obesity and treat obesity-associated metabolic disorders. As described in detail in the review, BAT activity appears to inversely correlate with body mass index and body fat content, and BAT activation ameliorates weight gain and improves plasma glucose and lipid profiles. However, whether BAT activation holds therapeutic value for cardiovascular disease in humans is an unanswered question for now. Nonetheless, a general beneficial effect of BAT activation toward the reduction of cardiovascular risk factors is not unimaginable. The mechanisms of BAT secretory protein upregulation and action are another potentially fruitful avenue toward developing therapies based on brown fat. These secreted factors may potentially exert metabolic benefits on adipose tissues, the heart, or other peripheral tissues; participate in coordinating various aspects of metabolic adaptation during cardiovascular insults; and contribute to direct cardioprotection. Defining the brown fat secretome and elucidating its function are a critical first step toward understanding the metabolic cross talk between BAT and other tissues. Future research warrants answering the question if BAT and its BATokines will yield new therapies for metabolic disorders and cardiovascular disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R21-DK-092909 (to M. Scherrer-Crosbie) and the Tosteson Fund for Medical Discovery (to R. Thoonen).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.T. and A.G.H. drafted manuscript; R.T., A.G.H., and M.S.-C. edited and revised manuscript; R.T. and M.S.-C. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aherne W, Hull D. Brown adipose tissue and heat production in the newborn infant. J Pathol Bacteriol : 223–234, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almabrouk TAM, Ewart MA, Salt IP, Kennedy S. Perivascular fat, AMP-activated protein kinase and vascular diseases. Br J Pharmacol : 595–617, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anunciado-Koza R, Ukropec J, Koza RA, Kozak LP. Inactivation of UCP1 and the glycerol phosphate cycle synergistically increases energy expenditure to resist diet-induced obesity. J Biol Chem : 27688–27697, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachman ES, Dhillon H, Zhang CY, Cinti S, Bianco AC, Kobilka BK, Lowell BB. betaAR signaling required for diet-induced thermogenesis and obesity resistance. Science : 843–845, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakker LEH, Boon MR, van der Linden RAD, Arias-Bouda LP, van Klinken JB, Smit F, Verberne HJ, Jukema JW, Tamsma JT, Havekes LM, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Jazet IM, Rensen PCN. Brown adipose tissue volume in healthy lean south Asian adults compared with white Caucasians: a prospective, case-controlled observational study. Lancet : 210–217, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron DM, Clerté M, Brouckaert P, Raher MJ, Flynn AW, Zhang H, Carter EA, Picard MH, Bloch KD, Buys ES, Scherrer-Crosbie M. In vivo noninvasive characterization of brown adipose tissue blood flow by contrast ultrasound in mice. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging : 652–659, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartelt A, Bruns OT, Reimer R, Hohenberg H, Ittrich H, Peldschus K, Kaul MG, Tromsdorf UI, Weller H, Waurisch C, Eychmüller A, Gordts PLSM, Rinninger F, Bruegelmann K, Freund B, Nielsen P, Merkel M, Heeren J. Brown adipose tissue activity controls triglyceride clearance. Nat Med : 200–205, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartelt A, Heeren J. Adipose tissue browning and metabolic health. Nat Rev Endocrinol : 24–36, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blondin DP, Labbé SM, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Turcotte EE, Richard D, Carpentier AC, Haman F. Contributions of white and brown adipose tissues and skeletal muscles to acute cold-induced metabolic responses in healthy men. J Physiol (Lond) : 701–714, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blondin DP, Labbé SM, Tingelstad HC, Noll C, Kunach M, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Turcotte EE, Carpentier AC, Richard D, Haman F. Increased brown adipose tissue oxidative capacity in cold-acclimated humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab : E438–E446, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonet ML, Oliver P, Palou A. Pharmacological and nutritional agents promoting browning of white adipose tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta : 969–985, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bordicchia M, Liu D, Amri EZ, Ailhaud G, Dessì-Fulgheri P, Zhang C, Takahashi N, Sarzani R, Collins S. Cardiac natriuretic peptides act via p38 MAPK to induce the brown fat thermogenic program in mouse and human adipocytes. J Clin Invest : 1022–1036, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boström P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Boström EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, Kajimura S, Zingaretti MC, Vind BF, Tu H, Cinti S, Højlund K, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature : 463–468, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branca RT, He T, Zhang L, Floyd CS, Freeman M, White C, Burant A. Detection of brown adipose tissue and thermogenic activity in mice by hyperpolarized xenon MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA : 18001–18006, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler AA, Kozak LP. A recurring problem with the analysis of energy expenditure in genetic models expressing lean and obese phenotypes. Diabetes : 323–329, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev : 277–359, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Metabolic consequences of the presence or absence of the thermogenic capacity of brown adipose tissue in mice (and probably in humans). Int J Obes (Lond) , Suppl 1: S7–S16, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caporali A, Sala-Newby GB, Meloni M, Graiani G, Pani E, Cristofaro B, Newby AC, Madeddu P, Emanueli C. Identification of the prosurvival activity of nerve growth factor on cardiac myocytes. Cell Death Differ : 299–311, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celi FS, Le TN, Ni B. Physiology and relevance of human adaptive thermogenesis response. Trends Endocrinol Metab : 238–247, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang L, Milton H, Eitzman DT, Chen YE. Paradoxical roles of perivascular adipose tissue in atherosclerosis and hypertension. Circ J : 11–18, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang L, Villacorta L, Li R, Hamblin M, Xu W, Dou C, Zhang J, Wu J, Zeng R, Chen YE. Loss of perivascular adipose tissue on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ deletion in smooth muscle cells impairs intravascular thermoregulation and enhances atherosclerosis. Circulation : 1067–1078, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chatterjee TK, Stoll LL, Denning GM, Harrelson A, Blomkalns AL, Idelman G, Rothenberg FG, Neltner B, Romig-Martin SA, Dickson EW, Rudich S, Weintraub NL. Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular adipocytes: influence of high-fat feeding. Circ Res : 541–549, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YCI, Cypess AM, Chen YC, Palmer M, Kolodny G, Kahn CR, Kwong KK. Measurement of human brown adipose tissue volume and activity using anatomic MR imaging and functional MR imaging. J Nucl Med : 1584–1587, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YI, Cypess AM, Sass CA, Brownell AL, Jokivarsi KT, Kahn CR, Kwong KK. Anatomical and functional assessment of brown adipose tissue by magnetic resonance imaging. Obesity (Silver Spring) : 1519–1526, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chondronikola M, Volpi E, Børsheim E, Porter C, Annamalai P, Enerbäck S, Lidell ME, Saraf MK, Labbé SM, Hurren NM, Yfanti C, Chao T, Andersen CR, Cesani F, Hawkins H, Sidossis LS. Brown adipose tissue improves whole-body glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes : 4089–4099, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cinti S. The role of brown adipose tissue in human obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis : 569–574, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cinti S. Between brown and white: novel aspects of adipocyte differentiation. Ann Med : 104–115, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claussnitzer M, Dankel SN, Kim KH, Quon G, Meuleman W, Haugen C, Glunk V, Sousa IS, Beaudry JL, Puviindran V, Abdennur NA, Liu J, Svensson PA, Hsu YH, Drucker DJ, Mellgren G, Hui CC, Hauner H, Kellis M. FTO obesity variant circuitry and adipocyte browning in humans. N Engl J Med : 895–907, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clerté M, Baron DM, Brouckaert P, Ernande L, Raher MJ, Flynn AW, Picard MH, Bloch KD, Buys ES, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Brown adipose tissue blood flow and mass in obesity: a contrast ultrasound study in mice. J Am Soc Echocardiogr : 1465–1473, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cronin CG, Prakash P, Daniels GH, Boland GW, Kalra MK, Halpern EF, Palmer EL, Blake MA. Brown fat at PET/CT: correlation with patient characteristics. Radiology : 836–842, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham S, Leslie P, Hopwood D, Illingworth P, Jung RT, Nicholls DG, Peden N, Rafael J, Rial E. The characterization and energetic potential of brown adipose tissue in man. Clin Sci : 343–348, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, Kolodny GM, Kahn CR. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med : 1509–1517, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cypess AM, Weiner LS, Roberts-Toler C, Franquet Elía E, Kessler SH, Kahn PA, English J, Chatman K, Trauger SA, Doria A, Kolodny GM. Activation of human brown adipose tissue by a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Cell Metab : 33–38, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cypess AM, White AP, Vernochet C, Schulz TJ, Xue R, Sass CA, Huang TL, Roberts-Toler C, Weiner LS, Sze C, Chacko AT, Deschamps LN, Herder LM, Truchan N, Glasgow AL, Holman AR, Gavrila A, Hasselgren PO, Mori MA, Molla M, Tseng YH. Anatomical localization, gene expression profiling and functional characterization of adult human neck brown fat. Nat Med : 635–639, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Date H, Imamura T, Ideguchi T, Kawagoe J, Sumi T, Masuyama H, Onitsuka H, Ishikawa T, Nagoshi T, Eto T. Adiponectin produced in coronary circulation regulates coronary flow reserve in nondiabetic patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries. Clin Cardiol : 211–214, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Jesus LA, Carvalho SD, Ribeiro MO, Schneider M, Kim SW, Harney JW, Larsen PR, Bianco AC. The type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase is essential for adaptive thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. J Clin Invest : 1379–1385, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Matteis R, Ricquier D, Cinti S. TH-, NPY-, SP-, and CGRP-immunoreactive nerves in interscapular brown adipose tissue of adult rats acclimated at different temperatures: an immunohistochemical study. J Neurocytol : 877–886, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dempersmier J, Sul HS. Shades of brown: a model for thermogenic fat. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) : 71, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dhall M, Chaturvedi MM, Rai U, Kapoor S. Sex-dependent effects of the UCP1 -3826 A/G polymorphism on obesity and blood pressure. Ethn Dis : 181–184, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dulloo AG, Miller DS. Energy balance following sympathetic denervation of brown adipose tissue. Can J Physiol Pharmacol : 235–240, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dulloo AG. Translational issues in targeting brown adipose tissue thermogenesis for human obesity management. Ann NY Acad Sci : 1–10, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Enerbäck S, Jacobsson A, Simpson EM, Guerra C, Yamashita H, Harper ME, Kozak LP. Mice lacking mitochondrial uncoupling protein are cold-sensitive but not obese. Nature : 90–94, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eringa EC, Bakker W, van Hinsbergh VWM. Paracrine regulation of vascular tone, inflammation and insulin sensitivity by perivascular adipose tissue. Vascul Pharmacol : 204–209, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fedorenko A, Lishko PV, Kirichok Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell : 400–413, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feldmann HM, Golozoubova V, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab : 203–209, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandez JA, Mampel T, Villarroya F, Iglesias R. Direct assessment of brown adipose tissue as a site of systemic tri-iodothyronine production in the rat. Biochem J : 281–284, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Festuccia WT, Blanchard PG, Deshaies Y. Control of brown adipose tissue glucose and lipid metabolism by PPARγ. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) : 84, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fesus G, Dubrovska G, Gorzelniak K, Kluge R, Huang Y, Luft FC, Gollasch M. Adiponectin is a novel humoral vasodilator. Cardiovasc Res : 719–727, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fitzgibbons TP, Czech MP. Epicardial and perivascular adipose tissues and their influence on cardiovascular disease: basic mechanisms and clinical associations. J Am Heart Assoc : e000582–e000582, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fitzgibbons TP, Kogan S, Aouadi M, Hendricks GM, Straubhaar J, Czech MP. Similarity of mouse perivascular and brown adipose tissues and their resistance to diet-induced inflammation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol : H1425–H1437, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flynn A, Li Q, Panagia M, Abdelbaky A, MacNabb M, Samir A, Cypess AM, Weyman AE, Tawakol A, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound: a novel noninvasive, nonionizing method for the detection of brown adipose tissue in humans. J Am Soc Echocardiogr : 1247–1254, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fontes JA, Rose NR, Čiháková D. The varying faces of IL-6: From cardiac protection to cardiac failure. Cytokine : 62–68, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forini F, Nicolini G, Iervasi G. Mitochondria as key targets of cardioprotection in cardiac ischemic disease: role of thyroid hormone triiodothyronine. Int J Mol Sci : 6312–6336, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fromme T, Klingenspor M. Uncoupling protein 1 expression and high-fat diets. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol : R1–R8, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frontini A, Cinti S. Distribution and development of brown adipocytes in the murine and human adipose organ. Cell Metab : 253–256, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao YJ, Lu C, Su LY, Sharma AM, Lee RMKW. Modulation of vascular function by perivascular adipose tissue: the role of endothelium and hydrogen peroxide. Br J Pharmacol : 323–331, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao YJ. Dual modulation of vascular function by perivascular adipose tissue and its potential correlation with adiposity/lipoatrophy-related vascular dysfunction. Curr Pharm Design : 2185–2192, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gesner C. medici Tigurini Historiae animalium Lib. I. de quadrupedibus viuiparis. Zurich, Switzerland: Tiguri:Apud Christ Froschouerum, 1551. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gimeno RE, Moller DE. FGF21-based pharmacotherapy–potential utility for metabolic disorders. Trends Endocrinol Metab : 303–311, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giralt M, Cereijo R, Villarroya F. Adipokines and the endocrine role of adipose tissues. Handb Exp Pharmacol : 265–282, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gnad T, Scheibler S, Kügelgen von I, Scheele C, Kilić A, Glöde A, Hoffmann LS, Reverte-Salisa L, Horn P, Mutlu S, El-Tayeb A, Kranz M, Deuther-Conrad W, Brust P, Lidell ME, Betz MJ, Enerbäck S, Schrader J, Yegutkin GG, Müller CE, Pfeifer A. Adenosine activates brown adipose tissue and recruits beige adipocytes via A2A receptors. Nature : 395–399, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Golozoubova V, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 is essential for adaptive adrenergic nonshivering thermogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab : E350–E357, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Golozoubova V, Hohtola E, Matthias A, Jacobsson A, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Only UCP1 can mediate adaptive nonshivering thermogenesis in the cold. FASEB J : 2048–2050, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guido L, Camila M. Perivascular adipose tissue, inflammation and insulin resistance: link to vascular dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig : 19, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gunawardana SC, Piston DW. Reversal of type 1 diabetes in mice by brown adipose tissue transplant. Diabetes : 674–682, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gunawardana SC, Piston DW. Insulin-independent reversal of type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice with brown adipose tissue transplant. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab : E1043–E1055, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo J, Jou W, Gavrilova O, Hall KD. Persistent diet-induced obesity in male C57BL/6 mice resulting from temporary obesigenic diets. PLoS ONE : e5370, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamann A, Flier JS, Lowell BB. Decreased brown fat markedly enhances susceptibility to diet-induced obesity, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. Endocrinology : 21–29, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hammar JA. Zur Kenntniss des Fettgewebes. Archiv f mikrosk Anat : 512–574, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hanssen MJW, Hoeks J, Brans B, van der Lans AAJJ, Schaart G, van den Driessche JJ, Jörgensen JA, Boekschoten MV, Hesselink MKC, Havekes B, Kersten S, Mottaghy FM, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Schrauwen P. Short-term cold acclimation improves insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Med : 863–865, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hara T, Kashihara D, Ichimura A, Kimura I, Tsujimoto G, Hirasawa A. Role of free fatty acid receptors in the regulation of energy metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta : 1292–1300, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heaton GM, Wagenvoord RJ, Kemp A, Nicholls DG. Brown-adipose-tissue mitochondria: photoaffinity labelling of the regulatory site of energy dissipation. Eur J Biochem : 515–521, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heaton JM. The distribution of brown adipose tissue in the human. J Anat : 35–39, 1972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hondares E, Iglesias R, Giralt A, Gonzalez FJ, Giralt M, Mampel T, Villarroya F. Thermogenic activation induces FGF21 expression and release in brown adipose tissue. J Biol Chem : 12983–12990, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Houben AJ, Eringa EC, Jonk AM, Serne EH, Smulders YM, Stehouwer CD. Perivascular fat and the microcirculation: relevance to insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep : 80–90, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huttunen P, Hirvonen J, Kinnula V. The occurrence of brown adipose tissue in outdoor workers. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol : 339–345, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iacobellis G, Pistilli D, Gucciardo M, Leonetti F, Miraldi F, Brancaccio G, Gallo P, di Gioia CRT. Adiponectin expression in human epicardial adipose tissue in vivo is lower in patients with coronary artery disease. Cytokine : 251–255, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Iacobellis G. Local and systemic effects of the multifaceted epicardial adipose tissue depot. Nat Rev Endocrinol : 363–371, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iwen KA, Schröder E, Brabant G. Thyroid hormones and the metabolic syndrome. Eur Thyroid J : 83–92, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Izumiya Y, Bina HA, Ouchi N, Akasaki Y, Kharitonenkov A, Walsh K. FGF21 is an Akt-regulated myokine. FEBS Lett : 3805–3810, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jastroch M, Withers KW, Taudien S, Frappell PB, Helwig M, Fromme T, Hirschberg V, Heldmaier G, McAllan BM, Firth BT, Burmester T, Platzer M, Klingenspor M. Marsupial uncoupling protein 1 sheds light on the evolution of mammalian nonshivering thermogenesis. Physiol Genomics : 161–169, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jastroch M, Wuertz S, Kloas W, Klingenspor M. Uncoupling protein 1 in fish uncovers an ancient evolutionary history of mammalian nonshivering thermogenesis. Physiol Genomics : 150–156, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kajimura S, Saito M. A new era in brown adipose tissue biology: molecular control of brown fat development and energy homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol : 225–249, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Keipert S, Kutschke M, Lamp D, Brachthäuser L, Neff F, Meyer CW, Oelkrug R, Kharitonenkov A, Jastroch M. Genetic disruption of uncoupling protein 1 in mice renders brown adipose tissue a significant source of FGF21 secretion. Mol Metab : 537–542, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Khedoe PPSJ, Hoeke G, Kooijman S, Dijk W, Buijs JT, Kersten S, Havekes LM, Hiemstra PS, Berbée JFP, Boon MR, Rensen PCN. Brown adipose tissue takes up plasma triglycerides mostly after lipolysis. J Lipid Res : 51–59, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kontani Y, Wang Y, Kimura K, Inokuma KI, Saito M, Suzuki-Miura T, Wang Z, Sato Y, Mori N, Yamashita H. UCP1 deficiency increases susceptibility to diet-induced obesity with age. Aging Cell : 147–155, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kopecky J, Clarke G, Enerbäck S, Spiegelman B, Kozak LP. Expression of the mitochondrial uncoupling protein gene from the aP2 gene promoter prevents genetic obesity. J Clin Invest : 2914–2923, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kozak LP, Koza RA, Anunciado-Koza R. Brown fat thermogenesis and body weight regulation in mice: relevance to humans. Int J Obes (Lond) , Suppl 1: S23–S27, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kozak LP. Brown fat and the myth of diet-induced thermogenesis. Cell Metab : 263–267, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Labbé SM, Caron A, Bakan I, Laplante M, Carpentier AC, Lecomte R, Richard D. In vivo measurement of energy substrate contribution to cold-induced brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. FASEB J : 2046–2058, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lafontan M, Berlan M. Fat cell adrenergic receptors and the control of white and brown fat cell function. J Lipid Res : 1057–1091, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lafontan M, Moro C, Berlan M, Crampes F, Sengenes C, Galitzky J. Control of lipolysis by natriuretic peptides and cyclic GMP. Trends Endocrinol Metab : 130–137, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lean ME, James WP, Jennings G, Trayhurn P. Brown adipose tissue uncoupling protein content in human infants, children and adults. Clin Sci : 291–297, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee P, Linderman JD, Smith S, Brychta RJ, Wang J, Idelson C, Perron RM, Werner CD, Phan GQ, Kammula US, Kebebew E, Pacak K, Chen KY, Celi FS. Irisin and FGF21 are cold-induced endocrine activators of brown fat function in humans. Cell Metab : 302–309, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee P, Swarbrick MM, Ho KKY. Brown adipose tissue in adult humans: a metabolic renaissance. Endocr Rev : 413–438, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee Y, Willers C, Kunji ERS, Crichton PG. Uncoupling protein 1 binds one nucleotide per monomer and is stabilized by tightly bound cardiolipin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA : 6973–6978, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee YC, Chang HH, Chiang CL, Liu CH, Yeh JI, Chen MF, Chen PY, Kuo JS, Lee TJF. Role of perivascular adipose tissue-derived methyl palmitate in vascular tone regulation and pathogenesis of hypertension. Circulation : 1160–1171, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]