Abstract

Purple corn is a maize variety (Zea mays L.) with high anthocyanin content. When purple corn is used as forage, its anthocyanins may mitigate oxidative stresses causing lower milk production in dairy cows. In this study, we analyzed quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for anthocyanin pigmentation of maize organs in an F2 population derived from a cross between the Peruvian cultivar ‘JC072A’ (purple) and the inbred line ‘Ki68’ (yellowish) belonged to Japanese flint. We detected 17 significant QTLs on chromosomes 1–3, 6, and 10. Because the cob accounts for most of the fresh weight of the plant ear, we focused on a significant QTL for purple cob on chromosome 6. This QTL also conferred pigmentation of anther, spikelet, leaf sheath, culm, and bract leaf, and was confirmed by using two F3 populations. The gene Pl1 (purple plant 1) is the most likely candidate gene in this QTL region because the amino acid sequence encoded by Pl1-JC072A is similar to that of an Andean allele, Pl-bol3, which is responsible for anthocyanin production. The markers designed for the Pl1 alleles will be useful for the breeding of F1 lines with anthocyanin pigmentation in cobs.

Keywords: maize, Peruvian cultivar, Japanese flint cultivar, anthocyanin pigmentation, QTL analysis, purple plant 1 (Pl1)

Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) is grown worldwide as a cereal and fodder crop, and grain color variants (white, yellow, and purple) are also used to extract colorants in food and beverages. Purple corn is originated from the species “Kculli”, still cultivated in Peru (Grobman 1961). Its color is determined by anthocyanins, which are used to color jellies and syrups and as a health supplement in Japan (Aoki et al. 2002). Anthocyanins from purple corn have high antioxidant activity (Cevallos-Casals and Cisneros-Zevallos 2003), inhibit colorectal carcinogenesis in male rats (Hagiwara et al. 2001), reduce blood pressure in male spontaneously hypertensive rats (Shindo et al. 2007) and reduce AST (aspartate aminotransferase) activity and an increase SOD (superoxide dismutase) activity in lactating dairy cows (Hosoda et al. 2012). Then, anthocyanins from purple corn may mitigate oxidative stresses in dairy cows.

In purple cobs, the anthocyanin content ranges from 30% to 47% of total phenolic components (Jing et al. 2007), and the accumulation of anthocyanins are increased by drought, low temperature, visible light, and UV radiation (Chalker-Scott 1999). The regulatory genes R, B, C1, and Pl are responsible for anthocyanin synthesis; by sequence similarity, they are grouped into two families, R/B and C1/Pl (Chandler et al. 1989, Cone et al. 1986). The interaction of each gene of these families changes the temporal and spatial pattern of anthocyanin pigmentation.

The R and B genes encode proteins homologous to the basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) DNA-binding–protein dimerization domain of Myc oncoproteins (Chandler et al. 1989, Consonni et al. 1993, Ludwig et al. 1989). The C1 and Pl genes encode R2R3 MYB transcription factors (Cone et al. 1986, 1993a, 1993b, Paz-Ares et al. 1986). Anthocyanin pigmentation of maize organs is controlled by at least 20 loci, comprising genes encoding DNA-bindingprotein and transcriptional factors (Mol et al. 1998). It is necessary to understand the genetic architecture responsible for anthocyanin synthesis in breeding materials.

A program to breed Japanese elite flint cultivars with anthocyanin pigmentation has been designed to mitigate the oxidative stress causing the lower milk production in dairy cows. We used an unpigmented inbred line, ‘Ki68’ belongs to Japanese flint (Tamaki et al. 2014), and an anthocyanincontaining cultivar, ‘JC072A’, in the breeding program. ‘Ki68’ has green bract leaf, culm, and leaf sheath and white cobs, whereas ‘JC072A’ shows them with dark purple. Using F2 progeny of a cross between ‘Ki68’ and ‘JC072A’, we identified QTLs for anthocyanin synthesis and elucidated the genetic mechanisms that contribute to anthocyanin pigmentation.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and pigmentation grading

The F2 and F3 populations were established from a cross between the inbred line ‘Ki68’ belonged to Japanese flint and the Peruvian cultivar ‘JC072A’. Anthocyanin pigmentation was assessed at the time of self-pollination (anther, spikelet, and silk), at the kernel dent stage (leaf sheath, culm, midrib of leaf blade, prop root, and bract leaf), and at the physiological matured stage (top and dorsal sides of grain, and glumes of cob). Anthocyanin pigmentation was graded from 1 (absent or very weak) to 9 (very strong).

Genotyping of F2 and F3 populations

Genomic DNA of 116 F2 individuals was extracted by CTAB method and PCR was carried out for indel amplification at 148 loci with (1) SSR markers available at MaizeGDB (http://www.maizegdb.org/), (2) markers designed on the basis of BAC sequences with linkage mapping information (Supplemental Table 1), and (3) a Pl1 marker designed as described below. PCR was performed in a 384-well thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with KAPA2G Fast Ready Mix (Kapabiosystems, Boston, MA, USA) as follows: 95°C for 1 min; 35 cycles at 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 1 s; and a final 72°C for 30 s. PCR products were electrophoresed in 3% agarose gels in TBE (Tris–borate–EDTA) buffer. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and the banding patterns were photographed under ultraviolet light for genotyping. Linkage mapping and QTL analysis were performed as described by Takai et al. (2012).

To validate the QTL for cob anthocyanin pigmentation on chromosome 6, we selected two F3 populations: F3-46 (67 plants) and F3-82 (70 plants). These populations were derived from F2 individuals with heterozygous alleles at the significant QTL region on chromosome 6 and homozygous ‘JC072A’ alleles at the QTL region with a high LOD peak on chromosome 10 (Supplemental Fig. 1). Genotypes and anthocyanin pigmentation of F3-46 and F3-82 were compared.

Isolation of Pl1 and marker development

Genomic DNA was extracted from ‘Ki68’ and ‘JC072A’ seedlings. Pl1 was isolated using the primers pl1myb_s_86 and pl1myb_as_87 (Supplemental Table 2). The Pl1 fragments amplified from ‘Ki68’ and ‘JC072A’ were purified with ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified PCR products were directly sequenced on an ABI PRIME 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) with primers newly designed on the basis of the determined nucleotide sequences: pl1_389-s, pl1_34-s, pl1myb_696-s, pl1_355-s, pl1myb_361-as, pl1_720-as, pl1_407-as, and pl1_495-as (Supplemental Table 2). The nucleotide sequences of the Pl1 alleles of ‘JC072A’ and ‘Ki68’ were assembled from the sequenced fragments and were registered in DDBJ (LC384358 and LC384359, respectively). To distinguish between the Pl1 alleles from ‘Ki68’ and ‘JC072A’, we performed fragment analysis with pl1_389-s and pl1_720-as primers as described by Yonemaru et al. (2009).

Phylogenetic analysis of Pl1

Known Pl1 (Pl) sequences (Cocciolone and Cone 1993, Cone et al. 1993b, Pilu et al. 2003) were obtained from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ/NCBI: L19496 (Pl-Tx303), L19494 (Pl-Rh), Q41842 (Pl-Bh), AY135018 (Pl-bol3), AY135019 (Pl-W22), and L19495 (Pl-McC). Amino acid sequences were aligned with CLUSTALW 2.1 software (Larkin et al. 2007). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted by the Neighbor Joining method in MEGA 7.0 software (Kumar et al. 2016).

Results

Detection of QTLs for anthocyanin pigmentation in maize organs

Significant QTLs were detected in 5 regions of chromosomes 1–3, 6, and 10; they affected anthocyanin pigmentation in 10 of the organs assayed (Table 1). No significant QTLs were found for pigmentation of the dorsal side of the grain. The effect of the QTL on chromosome 1 (qACprr1) was detected only in prop roots [LOD score (LOD) 4.2; additive effect (AE) 0.6]. The effects of significant QTLs on chromosome 2 (48.9–61.6 cM) were detected in spikelets (qACspk2), leaf sheaths (qAClsh2), culms (qACcul2), and bract leaves (qACbrl2). The values of LOD (10.5–13.6) and AE (2.0–2.3) were similar in these 4 organs. We only found the QTL on chromosome 3 for spikelets (qACspk3); it had the lowest values of phenotypic variance explained among all detected QTLs (Table 1).

Table 1.

QTLs for anthocyanin pigmentation of maize organs

| Organ | QTL Name | Chr. | Marker interval | LOD score | Additive effecta | Dominant effecta | % PVEb | Bin | No. of listed genes per Bin | Candidate genes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anther | qACant6 | 6 | 92.7 | 107.8 | 4.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 6.04 | 40 | pl1, sm1 |

| Anther | qACant10 | 10 | 73.7 | 76.1 | 19.8 | −1.9 | 0.1 | 52.0 | 10.06 | 51 | lc1, lcm1, Nc1, Nc2, Nc3, p, r1, S, Sc, sn1 |

| Spikelet | qACspk2 | 2 | 49.9 | 59.7 | 13.6 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 16.8 | 2.02–2.04 | 42, 35, 53 | b1 |

| Spikelet | qACspk3 | 3 | 19.5 | 30.7 | 4.9 | −0.5 | −1.0 | 0.0 | 3.01–3.04 | 25, 21, 16, 62 | no candidates |

| Spikelet | qACspk6 | 6 | 93.7 | 101.8 | 12.4 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 14.6 | 6.04 | 40 | pl1, sm1 |

| Silk | qACsil10 | 10 | 73.4 | 80.0 | 18.4 | −0.6 | 0.0 | 40.6 | 10.06 | 51 | lc1, lcm1, Nc1, Nc2, Nc3, p, r1, S, Sc, sn1 |

| Leaf sheath | qAClsh2 | 2 | 49.4 | 60.2 | 10.5 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 23.8 | 2.02–2.04 | 42, 35, 53 | b1 |

| Leaf sheath | qAClsh6 | 6 | 96.0 | 102.5 | 7.3 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 10.1 | 6.04 | 40 | pl1, sm1 |

| Culm | qACcul2 | 2 | 48.9 | 59.5 | 11.0 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 9.6 | 2.02–2.04 | 42, 35, 53 | b1 |

| Culm | qACcul6 | 6 | 93.2 | 103.8 | 8.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 12.5 | 6.04 | 40 | pl1, sm1 |

| Midrib of leaf blade | qACmlb10 | 10 | 73.5 | 81.5 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 15.0 | 10.06 | 51 | lc1, lcm1, Nc1, Nc2, Nc3, p, r1, S, Sc, sn1 |

| Prop root | qACprr1 | 1 | 181.3 | 193.2 | 4.2 | 0.6 | −0.2 | 12.7 | 1.07–1.09 | 79, 69, 69 | bz2 |

| Prop root | qACprr6 | 6 | 92.9 | 101.4 | 7.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 9.9 | 6.04 | 40 | pl1, sm1 |

| Bract leaf | qACbrl2 | 2 | 49.9 | 61.6 | 12.1 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 12.3 | 2.02–2.04 | 42, 35, 53 | b1 |

| Bract leaf | qACbrl6 | 6 | 94.1 | 102.7 | 10.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 7.9 | 6.04 | 40 | pl1, sm1 |

| Glumes of cob | qACglc6 | 6 | 94.3 | 100.2 | 22.2 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 7.1 | 6.04 | 40 | pl1, sm1 |

| Top side of grain | qACtsg6 | 6 | 95.7 | 100.2 | 30.8 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 11.7 | 6.04 | 40 | pl1, sm1 |

Positive values show that the JC072A allele increases values.

Percentage of phenotypic variance explained.

The QTL region on chromosome 6 (92.7–107.8 cM) significantly affected most organs: anther (qACant6), spikelet (qACspk6), leaf sheath (qAClsh6), culm (qACcul6), prop root (qACprr6), bract leaf (qACbrl6), glumes of cob (qACglc6), and the top side of grain (qACtsg6). Among all QTLs, qACtsg6 had the highest LOD (30.8) and qACglc6 had the highest AE (2.7).

The QTL region on chromosome 10 (73.4–81.5 cM) significantly affected pigmentation of anthers (qACant10), silks (qACsil10), and midrib of leaf blade (qACmlb10). The AE values of qACant10 (–1.9) and qACsil10 (–0.6) and that of qACmlb10 had opposite signs (0.4). In this region, no significant LOD peaks were observed for glumes of cob or grains (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Development of the Pl1 marker and association between Pl1 alleles and cob anthocyanin pigmentation

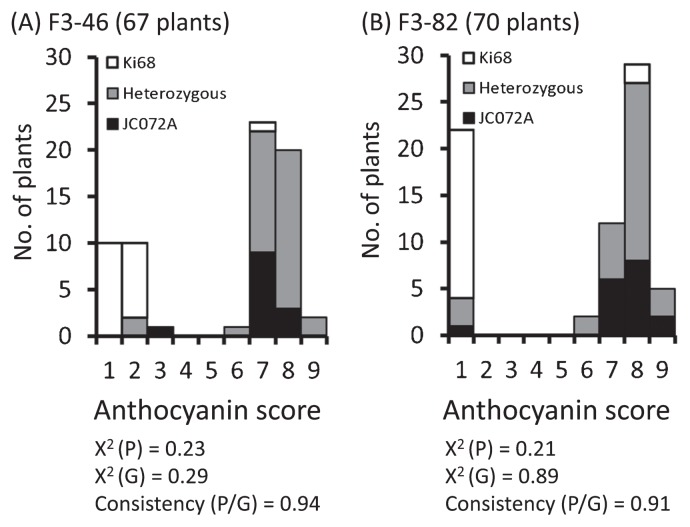

Because the cob accounts for most of the fresh weight of the plant ear, we focused on cob pigmentation. To avoid the interaction of the QTL on chromosome 10 with qACglc6, we selected two F3 populations (F3-46 and F3-82) for the validation of qACglc6 with the same alleles in the QTL region on chromosome 10 as in ‘JC072A’. In maize, Pl1 on chromosome 6 is required for anthocyanin synthesis in dark purple cobs (Hollick et al. 1995), implying that the functional Pl1 allele is responsible for anthocyanin pigmentation in ‘JC072A’. To detect the association between qACglc6 and Pl1, we developed a PCR marker (primers pl1_389-s and pl1_720-as). The segregation of the Pl1 genotype coincided with that of cob anthocyanin pigmentation at a 3:1 ratio in both F3 populations (consistency of 0.94 and 0.91, respectively; Fig. 1). These results confirm that the Pl1 gene on chromosome 6 is responsible for anthocyanin synthesis in cobs.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between cob anthocyanin score and Pl1 genotype in two F3 populations. The degree of anthocyanin pigmentation of cobs in F3-46 (67 plants) and F3-82 (70 plants) ranged from 1 (absent or weak) to 9 (very strong). Chi-squared tests assuming a 3:1 ratio were conducted on segregation of the phenotype (x ≤ 3, non-colored; X ≥ 6, colored) and Pl1 genotype (Ki68-type allele, non-colored; JC072A-type and heterozygous, colored). χ2 (P), chi-squared P value of the phenotype; χ2 (G), chi-squared P value of the genotype; consistency (P/G), consistency ratio between phenotype and genotype.

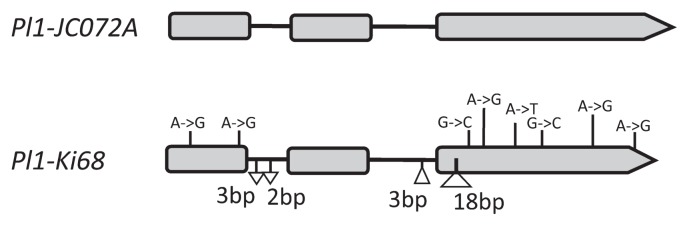

Comparison of Pl1 sequences between ‘JC072A’ and ‘Ki68’

We used the reported nucleotide sequences of Pl1 (Cone et al. 1993b) to obtain the sequences of Pl1 of ‘Ki68’ and ‘JC072A’ and designated the alleles Pl1-Ki68 and Pl1-JC072A, respectively. The comparison between the amplified fragments of Pl1-Ki68 (1014 bp) and Pl1-JC072A (1030 bp) showed that Pl1-Ki68 contained 2 SNPs in exon 1, 6 SNPs, and a 18-bp deletion in exon 3, 3-bp and 2-bp insertions in intron 1, and a 3-bp deletion in intron 2 (Fig. 2, Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of Pl1 gene structures between ‘JC072A’ and ‘Ki68’. Boxes, exons; horizontal bars, introns. The positions of insertions (▽), deletions (△), and single nucleotide polymorphisms in ‘Ki68’ are shown. The sequence alignment is shown in Supplemental Fig. 2.

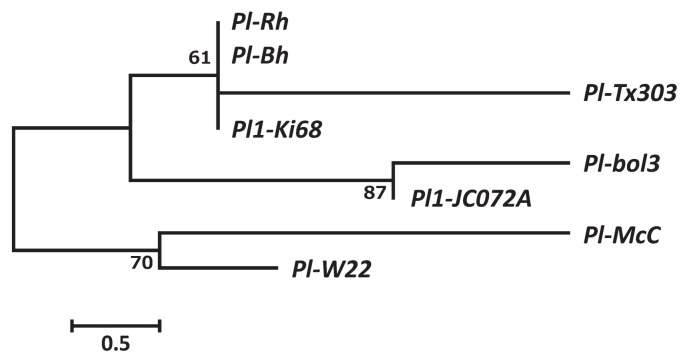

We aligned the deduced Pl1 amino sequences from ‘Ki68’ and ‘JC072A’ with those encoded by Pl-Rh, Pl-McC, Pl-Tx303, Pl-Bh, Pl-bol3, and Pl-W22 (Fig. 3). Pl1-Ki68 and Pl-Tx303 differed by substitutions of 2 amino acid residues and deletion of 1 residue in Pl-Tx303 (Supplemental Fig. 3). Pl1-JC072A and Pl-bol3 were of the same length with an amino acid substitution (Supplemental Fig. 3). In Pl-McC and Pl-W22, 3 residues around amino acid 190 were deleted and a residue was inserted relative to those of Pl-TX303 and Pl1-Ki68; the cobs of these cultivars are white. To check whether the identified Pl1 alleles mapped to chromosome 6, we designed a pair of primers for the Pl1 marker based on the identified nucleotide sequences of ‘Ki68’ and ‘JC072A’. Mapping and QTL analysis showed that Pl1 is located on chromosome 6, as previously reported, and detected a large-effect QTL at the Pl1 locus (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of Pl1 (Pl) based on amino acid sequences. Numbers indicate the bootstrap confidence values from 1000 replicates.

Discussion

In the F2 population, we detected 17 QTLs for anthocyanin pigmentation on chromosomes 1–3, 6, and 10 (Table 1). For 6 out of 10 organs, at least 2 QTLs were found, one on chromosome 6 (92.7–107.8 cM) and the other(s) on other chromosomes. These 6 combinations confirmed that anthocyanin pigmentation is controlled by the interaction of two different members, R/B and C1/Pl (Table 1).

Four QTLs (qACspk2, qAClsh2, qACcul2, and qACbl2) detected on chromosome 2 (48.9–61.6 cM) were located in bins 2.02–2.04. Out of 130 genes listed in these bins, only b1 is associated with anthocyanin synthesis (Table 1); dominant B1 alleles determine anthocyanin synthesis in most aboveground plant parts (Chandler et al. 1989). Two major dominant B1 alleles, B-I and B-Peru, have been reported; B-I determines pigmentation of spikelet, leaf sheath, culm, and bract leaf (Chandler et al. 1989, Radicella et al. 1992), whereas B-Peru determines pale color in these organs but strong purple aleurone as well as a transcriptional regulator of R1 gene encoding bHLH protein. Although not significant, a QTL for anthocyanin pigmentation in both cob and grain was detected at a region that included R1 on chromosome 10 (Supplemental Fig. 1). The significant QTLs (qACant10, qACsil10, qACmlb10) on chromosome 10 (73.4–81.5 cM) were located in bin 10.06. Among 51 genes listed in this bin, 10 are associated with anthocyanin synthesis (Table 1) and are related to the R1 gene members of which occur as at least two tightly linked genes (Eggleston et al. 1995, Ludwig and Wessler 1990). Four R1 gene family haplotypes—R-g, R-st, R-sc and lc—result in colored seed, but our QTLs coincided with colorless anthers (Petroni et al. 2000, Tonelli et al. 1994). The R1 allele in the ‘JC072A’ haplotype may be any one of these four alleles.

Purple corn has a high content of anthocyanins, which are important natural colorants. Whole cobs contain about 55% of the anthocyanins and whole kernels contain about 45% (Cevallos-Casals and Cisneros-Zevallos 2003). Purple cobs have the highest contents of monomeric and acylated anthocyanins, which are considered natural food colorants. Only the QTL region on chromosome 6 (92.7–102.7 cM) located in bin 6.04 could result in cob and grain pigmentation. Among 40 genes listed in bin 6.04, pl1 and sm1 are functional genes for anthocyanin pigmentation (Table 1), but sm1 does not confer cob and grain pigmentation (McMullen et al. 2004). Several alleles of pl (pl1) genes have been reported. The light-independent dominant allele Pl-Rhoades (Pl-Rh) contains a transposable CACTA element in the promoter and results in anthocyanin-rich seedlings with dark purple husks, culms, sheaths, tassels, and cobs (Cone et al. 1993b). A cultivar with unpigmented seedlings derived from McClintock’s stock (McC) and inbred line Tx303 respectively carry the light-dependent recessive alleles Pl-McC and Pl-Tx303. The expression of the Pl-bol3 allele is partially light independent, and Pl-bol3 is active mainly at the juvenile phase (Pilu et al. 2003). The results of Pl marker mapping and analysis using two F3 populations confirmed that the Pl allele of ‘JC072A’ (Pl1-JC072A) confers the anthocyanin pigmentation of cobs (Fig. 1, Supplemental Fig. 4). Sequence analysis of Pl genes showed that Pl1-JC072A is similar to the functional allele Pl-bol3 (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 3). Therefore, Pl1 is the most likely candidate gene responsible for anthocyanin production in cobs.

Although cobs with high anthocyanin content are useful for anthocyanin production, they tend to be injured by mold, which hampers harvesting F1 hybrid seeds. Each of the parents of an F1 hybrid with a different gene of two genes could sustain seed production of F1 hybrids. Our markers designed for the Pl1 genes will be useful for the breeding of F1 parents with anthocyanin coloration in cobs.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Yukari Shimazu and Emi Abe for help with genotyping in QTL mapping.

Literature Cited

- Aoki, H., Kuze, N. and Kato, Y. (2002) Anthocyanins isolated from purple corn (Zea mays L.). Foods Food Ingredients J. Japan 199: 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cevallos-Casals, B.A. and Cisneros-Zevallos, L. (2003) Stoichiometric and kinetic studies of phenolic antioxidants from Andean purple corn and red-fleshed sweetpotato. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51: 3313–3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalker-Scott, L. (1999) Environmental significance of anthocyanins in plant stress responses. Photochem. Photobiol. 70: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, V.L., Radicella, J.P., Robbins, T.P., Chen, J. and Turks, D. (1989) Two regulatory genes of the maize anthocyanin pathway are homologous: isolation of B utilizing R genomic sequences. Plant Cell 1: 1175–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocciolone, S.M. and Cone, K.C. (1993) Pl-Bh, an anthocyanin regulatory gene of maize that leads to variegated pigmentation. Genetics 135: 575–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone, K.C., Burr, F.A. and Burr, B. (1986) Molecular analysis of the maize anthocyanin regulatory locus C1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83: 9631–9635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone, K.C., Cocciolone, S.M., Burr, F.A. and Burr, B. (1993a) Maize anthocyanin regulatory gene pl is a duplicate of c1 that functions in the plant. Plant Cell 5: 1795–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone, K.C., Cocciolone, S.M., Moehlenkamp, C.A., Weber, T., Drummond, B.J., Tagliani, L.A., Bowen, B.A. and Perrot, G.H. (1993b) Role of the regulatory gene pl in the photocontrol of maize anthocyanin pigmentation. Plant Cell 5: 1807–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consonni, G., Geuna, F., Gavazzi, G. and Tonelli, C. (1993) Molecular homology among members of the R gene family in maize. Plant J. 3: 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston, W.B., Alleman, M. and Kermicle, J.L. (1995) Molecular organization and germinal instability of R-stippled maize. Genetics 141: 347–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobman, T.A. (1961) Races of maize in Peru: Their origins, evolution and classification. National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, A., Miyashita, K., Nakanishi, T., Sano, M., Tamano, S., Kadota, T., Koda, T., Nakamura, M., Imaida, K., Ito, N.et al. (2001) Pronounced inhibition by a natural anthocyanin, purple corn color, of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP)-associated colorectal carcinogenesis in male F344 rats pretreated with 1,2-dimethylhydrazine. Cancer Lett. 171: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollick, J.B., Patterson, G.I., Coe, E.H., JrCone, K.C. and Chandler, V.L. (1995) Allelic interactions heritably alter the activity of a metastable maize pl allele. Genetics 141: 709–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda, K., Eruden, B., Matsuyama, M. and Shioya, S. (2012) Effect of anthocyanin-rich corn silage on digestibility, milk production and plasma enzyme activities in lactating dairy cows. Anim. Sci. J. 83: 453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing, P., Noriega, V., Schwartz, S.J. and Giusti, M.M. (2007) Effects of growing conditions on purple corncob (Zea mays L.) anthocyanins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55: 8625–8629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G. and Tamura, K. (2016) MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33: 1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, M.A., Blackshields, G., Brown, N.P., Chenna, R., McGettigan, P.A., McWilliam, H., Valentin, F., Wallace, I.M., Wilm, A., Lopez, R.et al. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23: 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, S.R., Habera, L.F., Dellaporta, S.L. and Wessler, S.R. (1989) Lc, a member of the maize R gene family responsible for tissue-specific anthocyanin production, encodes a protein similar to transcriptional activators and contains the myc-homology region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86: 7092–7096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, S.R. and Wessler, S.R. (1990) Maize R gene family: tissue-specific helix-loop-helix proteins. Cell 62: 849–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen, M.D., Kross, H., Snook, M.E., Cortés-Cruz, M., Houchins, K., Musket, T.A. and Coe, E.H. (2004) Salmon silk genes contribute to the elucidation of the flavone pathway in maize (Zea mays L.). J. Hered. 95 3: 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol, J., Grotewold, E. and Koes, R. (1998) How genes paint flowers and seeds. Trends Plant Sci. 3: 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Ares, J., Wienand, U., Peterson, P.A. and Saedler, H. (1986) Molecular cloning of the c locus of Zea mays: a locus regulating the anthocyanin pathway. EMBO J. 5: 829–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroni, K., Cominelli, E., Consonni, G., Gusmaroli, G., Gavazzi, G. and Tonelli, C. (2000) The developmental expression of the maize regulatory gene Hopi determines germination-dependent anthocyanin accumulation. Genetics 155: 323–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilu, R., Piazza, P., Petroni, K., Ronchi, A., Martin, C. and Tonelli, C. (2003) pl-bol3, a complex allele of the anthocyanin regulatory pl1 locus that arose in a naturally occurring maize population. Plant J. 36: 510–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radicella, J.P., Brown, D., Tolar, L.A. and Chandler, V.L. (1992) Allelic diversity of the maize B regulatory gene: different leader and promoter sequences of two B alleles determine distinct tissue specificities of anthocyanin production. Genes Dev. 6: 2152–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo, M., Kasai, T., Abe, A. and Kondo, Y. (2007) Effects of dietary administration of plant-derived anthocyanin-rich colors to spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 53: 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai, T., Yonemaru, J.-i., Kaidai, H. and Kasuga, S. (2012) Quantitative trait locus analysis for days-to-heading and morphological traits in an RIL population derived from an extremely late flowering F1 hybrid of sorghum. Euphytica 187: 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki, H., Matsumoto, T., Mitsuhashi, S., Okumura, N., Kikawada, T. and Sato, H. (2014) A study on ‘Genomewide Selection’ for maize (Zea mays L.) Breeding in Japanese public sectors: Single nucleotide polymorphisms observed among parental inbred lines. Bull. NARO Inst. Livest. Grassl. Sci. 14: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli, C., Dolfini, S., Ronchi, A., Consonni, G. and Gavazzi, G. (1994) Light inducibility and tissue specificity of the R gene family in maize. Genetica 94: 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Yonemaru, J.-i. and Ando, T. and Mizubayashi, T. and Kasuga, S. and Matsumoto, T. and Yano, M. (2009) Development of genome-wide simple sequence repeat markers using whole-genome shotgun sequences of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). DNA Res. 16: 187–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.