Abstract

Of all patients diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, only 15–20% present with resectable disease. Despite curative-intent resection, the prognosis remains poor with the majority of patients recurring, prompting the need for adjuvant therapy. Historical data support the use of adjuvant 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or gemcitabine, but recent data suggest either gemcitabine plus capecitabine or modified FOLFIRINOX can improve overall survival when compared to gemcitabine alone. The use of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy remains controversial, primarily due to limitations in study design and mixed results of historical trials. The ongoing Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG)-0848 trial hopes to further define the role of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy. Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) and adjuvant immunotherapy represent additional possibilities to improve outcomes, but evidence supporting their use is limited. This article reviews adjuvant therapeutic strategies for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma, including chemotherapy, chemoradiation therapy, IORT and immunotherapy.

Keywords: Resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma, adjuvant, chemotherapy, chemoradiation, outcomes

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, with annual death rates remaining relatively stable from 2005–2015 (1). At the time of diagnosis, only 15–20% of patients with PDAC are candidates for surgical resection (2). Even after a curative-intent resection, without adjuvant therapy 70–92% of patients recur and just 10–18% survive more than 5 years (3–7). Adjuvant therapy is therefore needed, as resection alone is necessary but insufficient for cure.

In the adjuvant setting, various chemotherapy regimens have prolonged survival, including 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), gemcitabine, S-1, gemcitabine plus capecitabine, and modified FOLFIRINOX (Table 1). However, the addition of radiation therapy remains controversial because historical trials were limited in design, used suboptimal radiation delivery schedules and techniques, and showed mixed results. This article reviews adjuvant therapeutic strategies for resectable PDAC, including chemotherapy, chemoradiation therapy, intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT), and immunotherapy.

Table 1.

Major phase III trials of adjuvant therapy for resectable PDAC

| Trial | Year(s) published | N | Positive margins | LN involvement | Treatment arms | Recurrence | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GITSG (5) | 1985 | 43 | 0% | 28% | CRT (split-course 40 Gy/5-FU ×2 years) vs. observation | AR: 71% vs. 86%; LR: 47%; DM: 40% vs. 52% |

Median OS, 20 vs. 11 months (P=0.03) |

| EORTC 4089 (4) | 1999, 2007 | 218 | 21% | 38% (PDAC only) | CRT (split-course 40 Gy/5-FU) vs. observation | AR: 68% vs.

70%; LR*: 34% vs. 36%; DM*: 53% vs. 54% |

2-year OS (PDAC only), 34% vs. 26% (P=0.099) |

| ESPAC-1 (8) | 2001, 2004 | 289 | 18% | 54% | CRT (split-course 40 Gy/5-FU) vs. chemo (5-FU) vs. CRT + chemo vs. observation | LR: 62%; DM: 61% |

Chemo vs. no chemo: median OS, 20.1 vs. 15.5 months (P=0.009); CRT vs. no CRT: median OS, 15.9 vs. 17.9 months (P=0.05) |

| CONKO-001 (9) | 2007, 2013 | 368 | 17% | 72% | Gemcitabine vs. observation | AR: 74% vs. 92%; LR: 34% vs. 41% |

Median DFS, 13.4 vs. 6.7 months (P<0.001); median OS, 22.8 vs. 20.2 months (P=0.01) |

| RTOG-9704 (10) | 2008, 2011 | 451 | 34% | 66% | Gemcitabine vs. 5-FU, both before and after CRT (50.4 Gy/5-FU) | LR*: 25% vs.

30%; DM*: 76% vs. 70% |

Median OS (all patients), NA (P=0.51); median OS (pancreatic head tumors), 20.5 vs. 17.1 months (P=0.12) |

| ESPAC-3 (11) | 2010 | 1,088 | 35% | 72% | Gemcitabine vs. 5-FU | AR: 63% | Median OS, 23.6 vs. 23 months (P=0.39) |

| CapRI (12) | 2012 | 132 | 39% | 79% | CRIT (50.4 Gy/5-FU/ cis/IFN-α) + 5-FU (×2 cycles) vs. chemo (5-FU ×6 cycles) | AR: 80% | Median OS, 26.5 vs. 28.5 months (P=0.99) |

| JASPAC-01 (13) | 2016 | 385 | 13% | 63% | Gemcitabine vs. S-1 | AR: 78% vs. 66%; LR: 26% vs. 19% |

Median OS, 25.5 vs. 46.5 months (P<0.0001); median RFS, 11.3 vs. 22.9 months (P<0.0001) |

| IMPRESS (14) | 2016 | 722 | NA | NA | Gemcitabine ± CRT (50.4 Gy/5-FU) vs. gemcitabine ± CRT + algenpantucel-L |

NA | Median OS, 30.4 vs. 27.3 months (P>0.05) |

| ESPAC-4 (15) | 2017 | 732 | 60% | 80% | Gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine + capecitabine | AR: 66% vs. 65%; LR: 35% vs. 30% |

Median OS, 25.5 vs. 28 months (P=0.032) |

| CONKO-005 (16) | 2017 | 436 | 0% | 65% | Gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine + erlotinib | AR: 85% vs.

81%; isolated LR: 18% vs. 24%; DM: 82% vs. 76% |

Median DFS, 11.4 vs. 11.4 months (P=0.26); median OS, 26.5 vs. 24.5 months (P=0.61) |

| PRODIGE 24 (17) | 2018** | 493 | NA | NA | Gemcitabine vs. modified FOLFIRINOX | NA | Median DFS, 12.8 vs. 21.6 months (P<0.05); median OS, 34.8 vs. 54.4 months (P<0.05); median MFS, 17.7 vs. 30.4 months (P<0.05) |

, Recurrence reported as first site of failure;

, presented in abstract form, not yet published. PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; LN, lymph node; CRT, chemoradiation therapy; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; AR, any recurrence; OS, overall survival; NA, not available; chemo, chemotherapy; LR, local recurrence; DM, distant metastasis; DFS, disease-free survival; CRIT, chemoradioimmunotherapy; cis, cisplatin; IFN-α, interferon-alpha; RFS, relapse-free survival; FOLFIRINOX, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin; MFS, metastasis-free survival.

Defining resectability

Several definitions for resectability have been offered, with an evaluation of tumor anatomy serving as the basis for determining the feasibility of achieving an R0 resection(18–21). Resectability has traditionally been assessed with subjective terms describing the relationship of the primary tumor to surrounding blood vessels [celiac artery, common hepatic artery, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), portal vein (PV), and superior mesenteric vein (SMV)]. More recent definitions use objective geometric descriptions of the tumor-vessel interface to more accurately stratify patients and allow for optimal treatment paradigms. A 2014 consensus statement from the Society of Abdominal Radiology and American Pancreatic Association, endorsed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, classifies a PDAC tumor as resectable only if there is no arterial tumor contact, ≤180° tumor contact with the SMV or PV without vein contour irregularity, and no lymph node involvement beyond the field of resection (21,22).

As a result of evolving definitions of resectability, early adjuvant therapy studies for resectable PDAC typically included some patients who would be considered borderline resectable or locally advanced unresectable by current standards.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Traditionally, 5-FU has been used in adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation therapy trials for resectable PDAC, including the Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group (GITSG), European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)-40891 and European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC)-1 trials (see adjuvant chemoradiation therapy section below) (4,5,8). In 1997, Burris et al. published a landmark study showing that gemcitabine improved survival and alleviated disease-related symptoms compared to 5-FU for advanced PDAC (23), resulting in widespread acceptance of the use of gemcitabine for advanced disease.

Consequently, the Charité Onkologie (CONKO)-001 trial was launched to compare six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine to observation in patients with resectable PDAC. After enrolling 368 patients, including 17% with positive margins and 72% with nodal involvement, CONKO-001 demonstrated that gemcitabine improved both disease-free survival (DFS) (median, 13.4 vs. 6.7 months; P<0.001) and overall survival (OS) (median, 22.8 vs. 20.2 months; P=0.01) (6,9). Local recurrence occurred in 34% of the gemcitabine arm and 41% of the observation arm. Grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities occurred in only 3.8% of gemcitabine cycles. This trial established adjuvant gemcitabine as the standard of care for resectable PDAC.

To compare the efficacy of gemcitabine to 5-FU, the ESPAC-3 trial assigned 1,088 PDAC patients, 35% with positive margins and 72% with nodal involvement, to six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine or 5-FU (11). OS was similar between groups (median OS, 23.6 months with gemcitabine vs. 23 months with 5-FU; P=0.39). However, gemcitabine was better tolerated: 7.5% of the gemcitabine arm experienced grade 3/4 adverse events, compared to 14% of the 5-FU arm (P<0.001). The 5-FU arm faced higher rates of stomatitis (10% vs. 0%; P<0.001) and diarrhea (13% vs. 2%; P<0.001), whereas the gemcitabine arm faced slightly higher rates of leukopenia (10% vs. 6%; P=0.01). Because there was no difference in OS between groups, the ESPAC-3 trial established both gemcitabine and 5-FU as reasonable adjuvant options, with the caveat that gemcitabine may decrease toxicity. This finding was supported by a 2013 network meta-analysis of nine adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation trials, which showed an improvement in OS with use of either gemcitabine [hazard ratio (HR) 0.59; 95% CI, 0.41–0.83; P<0.05] or 5-FU (HR 0.65; 95% CI, 0.49–0.84; P<0.05) (24).

While a gemcitabine or 5-FU-based adjuvant regimen remains the standard of care in the United States, the Japan Adjuvant Study Group of Pancreatic Cancer (JASPAC)-01 study strongly suggests S-1, an oral drug containing tegafur (a prodrug of 5-FU), oteracil potassium, and gimeracil, should be the new standard of care in Japan (13). The trial randomized 385 patients, 13% with positive margins and 63% with nodal involvement, to four cycles of adjuvant S-1 or six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine, and demonstrated a significant benefit in OS (median, 46.5 vs. 25.5 months; P<0.0001) and relapse-free survival (median, 22.9 vs. months; P<0.0001) with S-1. Local recurrence occurred in only 19% of the S-1 arm. Grade 3/4 leukopenia and neutropenia were significantly less frequent with S-1. However, initial studies of S-1 in Caucasians suggest a higher rate of grade ≥3 gastrointestinal toxicity than that seen in East Asians, perhaps because the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of S-1 differ between the two populations (25–27).

Based on encouraging results in advanced PDAC (28), the combination of gemcitabine and capecitabine was recently studied in the ESPAC-4 trial for resectable PDAC (15). The study enrolled 732 patients, and demonstrated a significant improvement with six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine compared to six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine alone (median OS, 28 vs. 25.5 months; P=0.032). Notably, 60% had positive margins and 80% nodal involvement, higher than in any other chemotherapy trial to date. The improvement in OS with combination therapy was more pronounced in the margin-negative population (median OS, 39.5 vs. 27.9 months; P<0.001). Local recurrence was noted in 30% of the combination arm and 35% of the gemcitabine arm. There was no difference in the incidence of treatment-related serious adverse events between the arms (24% with combination vs. 26% with gemcitabine; P>0.05). Consequently, the ESPAC-4 study established gemcitabine plus capecitabine as the favored regimen for non-Asian patients with resectable PDAC.

Furthermore, the CONKO-005 trial randomized 436 patients with PDAC to adjuvant gemcitabine plus erlotinib or only gemcitabine (16). This was the first modern adjuvant therapy trial to explore the combination of chemotherapy and targeted therapy and only include patients after an R0 resection. There was no difference in DFS (median, 11.4 vs.11.4. months; P=0.26) or OS (median, 24.5 vs. 26.5 months; P=0.61) between the combination and gemcitabine only arms. However, there was a nonsignificant trend toward an increase in 5-year OS in the combination arm (25% vs. 20%). Phase II results from Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG)-0848 also suggest no benefit with erlotinib added to gemcitabine (29). Thus, while the addition of erlotinib to gemcitabine has been shown to improve OS and progression-free survival (PFS) in unresectable PDAC (30), there is no clear benefit for resectable PDAC.

At the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting, Conroy et al. presented results from PRODIGE 24, which randomized 493 patients with resected PDAC to either 12 cycles of modified FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin at 85 mg/m2, leucovorin at 400 mg/m2, irinotecan at 150 mg/m2 on day 1, plus 5-FU at 2.4 g/m2 over 46 hours), tested based on its success in the metastatic setting (31), or six cycles of gemcitabine (17). Modified FOLIRINOX resulted in significantly improved OS (median, 54.4 vs. 34.8 months; P<0.05) and DFS (median, 21.6 vs. 12.8 months; P<0.05). Perhaps expectedly, modified FOLFIRINOX led to more grade 3/4 toxicities (75.5% vs. 51.1%), including diarrhea (18.6% vs. 3.7%; P<0.001), fatigue (11.0% vs. 4.6%; P=0.014), sensory peripheral neuropathy (9.3% vs. 0%; P<0.001), vomiting (5.0% vs. 1.2%; P=0.039), and mucositis (2.5% vs. 0%; P=0.014). However, toxicities were reportedly manageable, with no treatment-related deaths in the modified FOLFIRINOX arm and one in the gemcitabine arm.

The ideal adjuvant regimen for resectable PDAC in the United States is therefore either modified FOLFIRINOX (in fit patients) or gemcitabine plus capecitabine, as established by the PRODIGE 24 and ESPAC-4 trials, respectively. However, even in recent chemotherapy trials, many patients had positive margins (0–60%), nodal involvement (63–80%), and local recurrence (18–41%) (Table 1), suggesting the presence of residual disease that may benefit from local therapy in addition to systemic therapy.

Adjuvant chemoradiation therapy

Early trials

Whereas adjuvant chemotherapy remains the standard of care for resectable PDAC, the addition of chemoradiation therapy remains controversial. The GITSG trial, published in 1985, randomized 42 patients with resected PDAC to adjuvant chemoradiation therapy (40 Gy split into two courses with concurrent bolus 5-FU, followed by maintenance 5-FU for 2 years or until disease progression) or observation (5). All patients had negative margins, and 28% had nodal involvement. Median OS improved from 11 months in the observation arm to 20 months in the chemoradiation therapy arm (P=0.03). Only 14% of the patients receiving chemoradiation therapy experienced a severe hematologic reaction, and overall 47% experienced local recurrence. In a validation cohort, 30 additional patients were treated with the same chemoradiation therapy regimen, resulting in a similar median OS of 18 months (32).

While the GITSG trial suggested a role for adjuvant chemoradiation therapy, results thereafter have not been as promising. The EORTC-40891 trial randomized 218 patients (55% with PDAC in the head of the pancreas, the rest with periampullary adenocarcinoma) to chemoradiation therapy (40 Gy split into two courses and concurrent infusional 5-FU, without maintenance chemotherapy) or observation. Positive margins were present in 21% of patients and nodal involvement in 38%. In an initial report, there was a trend toward but no significant improvement in 2-year OS among PDAC patients who underwent chemoradiation therapy vs. observation (34% vs. 26%, P=0.099) (4). On long-term follow-up, chemoradiation therapy provided no benefit in OS (HR 0.74; P=0.137) or PFS (HR 0.81; P=0.26) (3). Among all patients, 69% progressed, with no significant difference in the sites of first progression between the chemoradiation and observation arms (local, 34% vs. 36%; distant, 53% vs. 54%; P>0.05).

Although EORTC-40891 is typically viewed as a negative trial, there were several shortcomings in design and execution. If a one-sided instead of two-sided log-rank test had been used for comparison, the difference in OS would have reached statistical significance (33). Moreover, the study was statistically underpowered, radiation therapy quality assurance was not required, 20% of the treatment arm did not receive treatment because of postoperative complications or patient refusal, and almost half of the patients did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy per protocol. Primary tumors were heterogeneous in location and originated from the distal common bile duct and ampulla of Vater in addition to pancreatic origin cancers.

The next major trial was ESPAC-1, which sought to determine the role of adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation therapy in 541 eligible patients with resected PDAC. Patients could be placed into one of three randomizations: a two-by-two factorial design (± chemotherapy and ± chemoradiation therapy), a chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy randomization, and a chemoradiotherapy vs. no chemoradiotherapy randomization (34). Chemoradiation therapy was delivered according to GITSG but up to 60 Gy could be given, suggesting gross residual disease. Chemotherapy consisted of six cycles of 5-FU and was given following chemoradiation therapy. In 2001, Neoptolemos et al. released the interim results, which combined patients from all three randomizations and demonstrated a significant benefit for the adjuvant chemotherapy arm (median OS, 19.7 vs. 14 months; P=0.0005), but no benefit for the adjuvant chemoradiation therapy arm (median OS, 15.5 vs. 16.1 months; P=0.24) (34). In a 2004 final report including only the 289 patients randomized into the factorial design, of which 18% had positive margins and 54% nodal involvement, chemotherapy still provided a benefit in OS (median, 20.1 vs. 15.5 months; P=0.009), and chemoradiation therapy surprisingly resulted in a trend toward inferior OS (median, 15.9 vs. 17.9; P=0.05) (8). In this factorial design, the chemotherapy only arm had the best median OS (21.6 months), followed by the combination arm (19.9 months), observation arm (16.9 months), and chemoradiation therapy arm (13.9 months). Local recurrence occurred in 62%, higher than in any other phase III trial. ESPAC-1 concluded that adjuvant therapy for resectable PDAC should include chemotherapy, but not chemoradiation therapy.

The ESPAC-1 trial has been widely criticized (35,36), casting doubt on the finding that chemoradiation therapy may be detrimental to OS or RFS. First, because chemotherapy was administered after chemoradiation therapy, patients who received both treatments may have experienced inferior OS as a result of a delay in or nonadherence to chemotherapy treatment. The delay in or lack of compliance with chemotherapy treatment would necessitate analysis of each of the four groups separately, but the trial was inadequately powered to do so. Second, physicians could choose the randomization and were allowed to give additional “background” therapy, such that patients entered into the chemoradiation therapy randomization could receive background chemotherapy. Third, there was a lack of standardization and quality control in radiation therapy delivery.

In spite of the shortcomings of the EORTC-40891 and ESPAC-1 trials, their results led clinicians to move away from using adjuvant chemoradiation therapy for PDAC, especially in European countries.

Recent evidence

In the GITSG, EORTC-40891 and ESPAC-1 trials, radiation therapy was delivered in a split-course fashion to an inadequate total dose (40 Gy) without a requirement for centralized review of radiation fields. The use of split-course radiation therapy in GITSG was necessitated by the lack of 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3DCRT) that could minimize toxicity.

RTOG-9704, which randomized 451 patients to gemcitabine or 5-FU for three weeks before and three months after chemoradiation therapy (50.4 Gy/28 fractions continuous course with 5-FU), was the first trial to require prospective quality assurance of radiation therapy and a modern dose and fractionation scheme enabled by 3DCRT (10,37). Because both arms received radiation therapy, the study was not equipped to ascertain the benefit of radiation. In a 5-year analysis of the study, there was no significant difference in OS between the two arms among patients with pancreatic head tumors (median OS, 20.5 with gemcitabine vs. 17.1 months with 5-FU; P=0.12; adjusted HR 0.82; P=0.08) (10). Only 28% experienced local recurrence as the first site of recurrence, a marked improvement from prior trials, despite the high proportion of patients with T3/T4 disease (75%), positive margins (34%), and involved lymph nodes (66%). Importantly, failure to adhere to radiation therapy protocol guidelines was associated with inferior OS and local control in all patients, and a trend toward increased non-hematologic toxicity in patients receiving gemcitabine (38). This finding questioned the validity of previous trials that had not required central review of radiation therapy.

Incorporating results from RTOG-9704, the aforementioned 2013 network meta-analysis concluded that while adjuvant chemotherapy provides a survival benefit over observation, the addition of chemoradiation therapy is unlikely to further prolong survival (24). Moreover, the combination of chemoradiation therapy and gemcitabine may result in significantly greater hematological toxicity than either 5-FU or gemcitabine alone. Thus, although RTOG-9704 suggested that either gemcitabine or 5-FU could be combined with chemoradiation therapy, the utility of adjuvant chemoradiation still remained in question.

Despite mixed results from phase III trials, retrospective studies utilizing modern radiation doses and fractionation schemes suggest a survival benefit with adjuvant chemoradiation therapy. Combining data from 1,092 PDAC patients treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Mayo Clinic, Hsu et al. found that adjuvant chemoradiation therapy (50.4 Gy/28 fractions with 5-FU) improved survival compared to observation, even on matched-pair analysis (N=496; median OS, 21.9 vs. 14.3 months; P<0.001) (39). The study population consisted of 33% with positive margins and 68% with nodal involvement, similar to that of RTOG-9704. In a study using the National Cancer Database, Rutter et al. found a benefit in OS among 6,165 pT1–3N0–1M0 PDAC patients treated with adjuvant chemoradiation therapy (median dose, 50.4 Gy) vs. chemotherapy alone after propensity score matching (HR 0.85; P<0.001) (40). The benefit of chemoradiation therapy was more apparent among patients with R1 resection and pN1 disease, a finding consistent with several other studies (41–43).

Further advances in radiation techniques, including intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), proton therapy and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), may permit more conformal treatment planning and dose delivery. Outcomes with these techniques for resectable PDAC are limited to a few retrospective series. In a study of 71 patients who underwent adjuvant chemoradiation therapy with IMRT for resected PDAC, only 19% of patients experienced locoregional failure, 8% experienced grade 3/4 nausea and vomiting, and 6% experienced late complications of small bowel obstruction (44). This study suggests that IMRT reduces toxicity without compromising local control. While IMRT enables the delivery of highly conformal treatment plans, proton therapy confers additional dosimetric benefits as a result of the characteristic Bragg peak that minimizes exit dose. Nichols et al. found that proton therapy reduced small bowel and stomach exposure compared to IMRT for 8 patients with resected PDAC (45), and led to no grade 3 gastrointestinal toxicities among 22 patients with PDAC who received concomitant capecitabine (46). Lastly, SBRT targeted to a focal region may allow for the delivery of higher biological doses without increasing toxicity, as evidenced by a study that found no grade 3/4 toxicities in 24 patients with close or positive margins who received adjuvant SBRT (24 Gy in a single fraction) (47).

Radiation target volumes

The use of highly conformal radiation techniques may allow for a reevaluation of target volumes to improve tumor coverage and patient outcomes.

Traditionally, the required extent of nodal coverage and optimal target volumes with adjuvant radiation therapy have been poorly defined. In 2005, Brunner et al. published the first evidence-based guidelines to standardize target volume delineation with adjuvant radiation therapy, which was based on pathologic patterns of nodal spread in 175 patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (48). Important factors to consider included respiratory organ movement, frequency of lymph node involvement (particularly the peripancreatic, pancreaticoduodenal, hepatoduodenal ligament, para-aortic, SMA, and celiac trunk nodes), and expected toxicity. However, elective treatment of the hepatoduodenal ligament and para-aortic nodes significantly increased the radiation treatment volume, limiting the dose that could be delivered (48). RTOG offered its own consensus panel guidelines for standardizing target volume delineation (49), consistent with the work of Brunner et al. and others (48,50,51). According to the RTOG guidelines, the postoperative clinical target volume should include the most proximal 1–1.5 cm of the celiac artery, most proximal 2.5–3 cm of the SMA, portions of the PV, preoperative tumor volume, pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ), and portions of the aorta (most cephalad contour of the celiac artery, PV, or PJ to the bottom of typically the L2 vertebral body).

To better understand the most important anatomic locations for inclusion in radiation field design, Dholakia et al. mapped local recurrences of 90 patients with resected PDAC, and demonstrated that 90% of local recurrences occurred within a 1–3 cm volumetric expansion from the combined celiac axis and SMA contours (52). They proposed a modified planning target volume (PTV) that contained a majority of recurrences and was substantially smaller than the PTV recommended by RTOG. Yu et al. performed a similar mapping of local recurrences, except only included PDAC patients who did not receive adjuvant radiation therapy; the average modified PTV encompassing 90% of local recurrences was >50% smaller than the PTV generated using RTOG guidelines (53). These studies propose that smaller target volumes, combined with advanced radiation techniques, may decrease toxicity and permit dose escalation to improve local control.

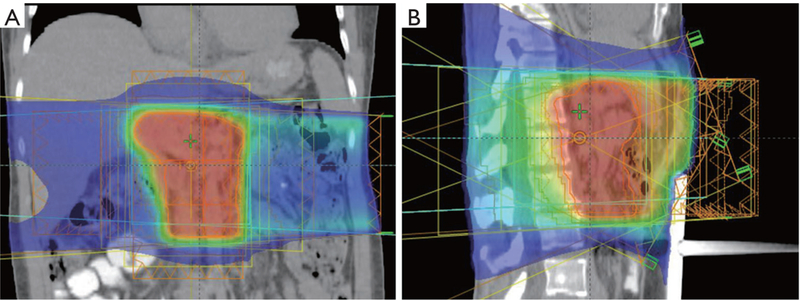

Overall, additional studies with modern radiation delivery schedules, techniques and target volumes are needed to clarify the role of adjuvant chemoradiation and chemoradiation plus chemotherapy. An example of a modern IMRT plan is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(A) Coronal and (B) sagittal views of an IMRT plan for a pT3N0 pancreatic adenocarcinoma, resected to negative margins and with 0/15 lymph nodes. The patient received 5,040 cGy in 180 cGy per fraction with concurrent twice daily capecitabine. This field encompassed the preoperative tumor volume, surgical margin, PJ, choledocojejunostomy, celiac axis, SMA and vein, porta hepatis, and paraaortic lymph nodes. This plan incorporated 6 MV photons and non-coplanar fields to better spare the liver and kidneys. Also, 4-dimensional computed tomography simulation with abdominal compression was employed to allow for reproducibility of respiratory motion. IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; PJ, pancreaticojejunostomy; SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

IORT

Since 36–62% of PDAC patients may experience local failure after a curative intent resection and without additional treatment (3,5,6,8), there is great interest in adjuvant targeted therapy to improve local control. IORT entails the delivery of a single fraction of high dose radiation therapy, traditionally 10–20 Gy, to the tumor bed after gross total resection or at the time of surgical exploration. IORT techniques include electron beam therapy and high-dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy. It is usually delivered as a boost after neoadjuvant or before adjuvant radiation therapy. Because organs at risk can be surgically moved away from the radiation field, IORT theoretically allows for safer delivery of higher radiation doses (54,55).

In the early 1980’s, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) performed the only prospective, randomized controlled trial of IORT for resected PDAC, including 24 patients (56,57). Following resection, patients received either IORT (20 Gy) or standard therapy (adjuvant radiation therapy to 45–55 Gy only for patients with extrapancreatic extension or nodal disease). Local recurrence occurred in only 33% of the IORT patients, and in 100% of the control patients. In this trial, many patients had disease that would be considered locally advanced by current criteria; as a result, study patients typically had extensive resections that sometimes included portions of the portal vascular system, and perioperative mortality was 27%.

Other studies examining IORT for resected PDAC have been retrospective in nature. Several early single-institution series comparing adjuvant IORT to surgery alone found improved local control with IORT (58–60); most notably, Zerbi et al. found that the use of IORT was associated with a decrease in local recurrences from 56% to 27% (P<0.01) (60). A multi-institutional series further suggested that preoperative radiation therapy could increase the effects of IORT and confer benefits in OS and local control (61). However, adjuvant treatments in these studies were highly variable, with less than 50% of patients receiving chemotherapy as the studies took place before the major chemotherapy trials. More recently, in a cohort of 83 patients, most of whom received adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy, Showalter et al. found no significant decrease in locoregional recurrence with the addition of IORT (23% with IORT vs. 39% without IORT; P=0.19) (62). Though the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy to IORT was found to improve OS over IORT alone (63), it remains unclear what additional benefit IORT may provide when added to modern chemotherapy and chemoradiation regimens.

Adjuvant immunotherapy

PDAC harbors a particularly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, mediated primarily by tumor-associated macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells and regulatory T cells (64,65). Immunotherapy strategies for PDAC include cytokines, vaccines, checkpoint modulators, and adoptive T-cell therapy. Only a few phase III studies have evaluated the synergistic effect of immunotherapy agents with adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy.

In 1995, in an attempt to improve upon the GITSG regimen and before the emergence of gemcitabine, investigators at Virginia Mason Medical Center devised an adjuvant regimen which added interferon-alpha (IFN-α) and cisplatin to chemoradiation therapy (45 to 60 Gy/25 fractions, concurrent with 5-FU, followed by two additional cycles of 5-FU). In 2003, Picozzi et al. reported a 5-year OS of 55% among 43 patients treated with this regimen (66). Forty-two percent of patients were hospitalized during adjuvant treatment due to toxicity, almost all gastrointestinal. Based on the impressive long-term survival seen at Virginia Mason, the CapRI trial was launched, enrolling 132 patients to compare IFN-α-based chemoradioimmunotherapy (similar to Virginia Mason protocol except radiation was delivered to 50.4 Gy/28 fractions) to six cycles of 5-FU monotherapy (12). There was no difference in OS between the respective groups (median OS, 26.5 vs. 28.5 months; P=0.99). The chemoradioimmunotherapy arm experienced greater grade 3/4 toxicity (85% vs. 16%, P not reported), primarily neutropenia and dehydration, and scored lower in numerous quality of life measures. Because of the significant toxicity with no improvement in outcomes, further trials with IFN-α are unlikely.

Another promising strategy is vaccine therapy, particularly whole cell vaccines which utilize irradiated tumor cells that express a panel of tumor associated antigens. Two allogenic whole cell vaccines have been investigated for use against resectable PDAC: GVAX and algenpantucel-L.

At Johns Hopkins University (JHU), Jaffee et al. developed GVAX, comprised of two allogeneic human pancreatic cancer cell lines engineered to express granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (67). GVAX primes the immune system, enhancing the ability of dendritic cells to present tumor associated antigens. A phase I study found that three out of eight patients who received the highest doses of GVAX experienced delayed-type hypersensitivity responses to autologous tumor cells and remained disease free for more than 15 years (68,69). In a subsequent phase II trial at JHU, 60 patients with resectable PDAC received uniform GVAX doses of 5×108 GM-CSF-secreting cells (70). Intradermal GVAX was first administered 8–10 weeks after resection, followed by 5-FU-based chemoradiation delivered according to RTOG-9704. Patients who remained disease-free after chemoradiation received up to three additional vaccinations given one month apart, followed by a final boost six months after the fourth treatment. The median OS of 24.8 months and median DFS of 17.3 months appear particularly promising. Based on the encouraging results, JHU has launched additional phase I/II trials investigating the use of GVAX in combination with SBRT and FOLFIRINOX (NCT01595321), and nivolumab (NCT02451982).

The second allogeneic vaccine is algenpantucel-L, which induces a hyperacute reaction using two irradiated pancreatic cancer cell lines expressing alpha-1,3-galactosyl transferase (αGT), an enzyme humans lack. αGT is responsible for the synthesis of alpha-galactosyl (αGal) epitopes and subsequent production of anti-αGal antibodies which mediate immune responses against αGal labelled tumor cells (71,72). The Immunotherapy for Pancreatic Resectable Cancer Study (IMPRESS) trial randomized 722 patients with resectable PDAC to gemcitabine with or without chemoradiation therapy (50.4 Gy/28 fractions with 5-FU) or the same with systemic algenpantucel-L (300 million cells every 2 weeks for 6 months, followed by every month for an additional 6 months). A press release in 2016 reported no difference in OS between the respective groups (median OS, 30.4 vs. 27.3 months; P>0.05) (14).

To date, no phase III trials have demonstrated a benefit in OS with the addition of adjuvant immunotherapy for resectable PDAC.

Biomarkers

Given similar outcomes between adjuvant gemcitabine and 5-FU, biomarkers could guide selection of optimal chemotherapy regimens for individual patients. Secondary analyses of RTOG-9704 and ESPAC-3 found that high levels of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT-1) correlated with OS in patients treated with adjuvant gemcitabine, but not in patients receiving adjuvant 5-FU or no adjuvant therapy (73,74). Other retrospective studies suggest the prognostic value of hENT1 and ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M1 (RRM1) expression levels (75), as well as Hu protein antigen R (HuR) expression levels (76), for patients treated with adjuvant gemcitabine. Finally, although Maréchal et al. demonstrated the prognostic value of deoxycytidine kinase (dCK) expression levels in patients treated with adjuvant gemcitabine (77), a secondary analysis of RTOG-9704 found that higher dCK levels predicted sensitivity to 5-FU, but not to gemcitabine (78). Overall, hENT-1, RRM1, HuR, and dCK are promising biomarkers that need to be evaluated prospectively to ascertain their roles in guiding adjuvant chemotherapy selection.

Biomarkers to guide the use of chemoradiation therapy are also desirable. Perhaps the most widely studied prognostic biomarker is CA19–9; reduction of CA19–9 levels after resection correlate with improved survival (79,80), and postoperative levels ≤90 U/mL may predict response to chemotherapy (81). Secondary analyses of RTOG-9704 found that low postoperative CA19–9 levels predicted survival, locoregional recurrence, and distant failure, suggesting CA19–9 can predict response to chemoradiation therapy as well (82,83). These studies propose that patients with postoperative levels ≥180 U/mL be considered candidates for more intensive systemic therapy or chemoradiation protocols. Other secondary analyses of RTOG-9704 suggest increased expression of MutL protein homolog 1 (MLH1) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) predict long-term survival and DFS after chemoradiation therapy (84,85). Finally, loss of the tumor suppressor gene DPC4 (SMAD4), one of the four most frequently mutated genes in PDAC, was found to correlate with distant failure in some studies (86,87), and with both distant and local failure in other studies (88,89). Thus, DPC4 status may define a population more likely to benefit from aggressive adjuvant chemoradiation strategies.

Ongoing trials

Ongoing phase III trials testing adjuvant regimens for resectable PDAC include the RTOG-0848 (NCT01013649) and APACT (NCT01964430) trials. RTOG-0848 aims to ascertain the benefit of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy when added to gemcitabine. In this trial, patients with no disease progression after five months of adjuvant gemcitabine are assigned to either one final month of gemcitabine or one month of gemcitabine plus chemoradiation therapy (50.4 Gy delivered via 3DCRT or IMRT, concurrent with 5-FU or capecitabine). Similar to the ESPAC-4 and PRODIGE 24 trials which showed benefits with more intense chemotherapy regimens, the APACT trial is comparing adjuvant gemcitabine to gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel, a regimen which improved OS in the metastatic setting (90). The results of these trials will hopefully broaden the landscape of adjuvant therapeutic options. Additionally, though not the focus of this review, multiple studies are exploring whether patients with potentially resectable PDAC can also benefit from neoadjuvant therapy.

Conclusions

Adjuvant therapy for resectable PDAC has improved tremendously over the years, with recent results from PRODIGE 24 suggesting a median OS of up to 54.4 months is possible. In the United States, accepted adjuvant treatment options include gemcitabine, 5-FU, gemcitabine plus capecitabine, or modified FOLFIRINOX, with the latter two demonstrating survival benefits compared to gemcitabine alone. In the Japanese population, S-1 is another viable option. The use of chemoradiation therapy remains controversial, although it may be more beneficial for patients with larger tumors, positive margins or lymph node involvement. RTOG-9704 suggests chemoradiation may be safely added to 5-FU or gemcitabine. We eagerly await the results of RTOG-0848 and incorporation of more advanced radiation techniques in the resectable setting. To further refine optimal treatment paradigms, all patients should be offered the opportunity for enrollment in a clinical trial.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work is supported by the following grants to DR Carpizo: R01CA200800 and K08CA172676.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: SK Jabbour has research funding from Merck and Nestle. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015 National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Released April 16, 2018. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1039–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Hop WC, et al. Long-term survival and metastatic pattern of pancreatic and periampullary cancer after adjuvant chemoradiation or observation: long-term results of EORTC trial 40891. Ann Surg 2007;246:734–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg 1999;230:776–82; discussion 82–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS. Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg 1985;120:899–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs. observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297:267–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, et al. Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma. Cancer 2002;95:1685–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1200–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310:1473–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams R, et al. Fluorouracil-based chemoradiation with either gemcitabine or fluorouracil chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: 5-year analysis of the U.S. Intergroup/RTOG 9704 phase III trial. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:1319–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs. gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304:1073–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt J, Abel U, Debus J, et al. Open-label, multicenter, randomized phase III trial of adjuvant chemoradiation plus interferon Alfa-2b versus fluorouracil and folinic acid for patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4077–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uesaka K, Boku N, Fukutomi A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy of S-1 versus gemcitabine for resected pancreatic cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial (JASPAC 01). The Lancet 2016;388:248–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NewLink Genetics Announces Results from Phase 3 IMPRESS Trial of Algenpantucel-L for Patients with Resected Pancreatic Cancer. Available online: https://globenewswire.com/news-release/2016/05/09/837878/0/en/NewLink-Genetics-Announces-Results-from-Phase-3-IMPRESS-Trial-of-Algenpantucel-L-for-Patients-with-Resected-Pancreatic-Cancer.html.

- 15.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2017;389:1011–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinn M, Bahra M, Liersch T, et al. CONKO-005: Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Gemcitabine Plus Erlotinib Versus Gemcitabine Alone in Patients After R0 Resection of Pancreatic Cancer: A Multicenter Randomized Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3330–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al. Unicancer GI PRODIGE 24/CCTG PA.6 trial: A multicenter international randomized phase III trial of adjuvant mFOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine (gem) in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. 2018. ASCO Annual Meeting Chicago, IL: June 4, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varadhachary GR, Tamm EP, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: definitions, management, and role of preoperative therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:1035–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vauthey JN, Dixon E. AHPBA/SSO/SSAT Consensus Conference on Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: rationale and overview of the conference. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:1725–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callery MP, Chang KJ, Fishman EK, et al. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:1727–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Hawary MM, Francis IR, Chari ST, et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma radiology reporting template: consensus statement of the Society of Abdominal Radiology and the American Pancreatic Association. Radiology 2014;270:248–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. In: Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (version 3.2017) Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/pancreatic.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2017.

- 23.Burris HA 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao WC, Chien KL, Lin YL, et al. Adjuvant treatments for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1095–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuah B, Goh BC, Lee SC, et al. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of S-1 between Caucasian and East Asian patients. Cancer Sci 2011;102:478–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ajani JA, Faust J, Ikeda K, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic study of S-1 plus cisplatin in patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6957–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoff PM, Saad ED, Ajani JA, et al. Phase I study with pharmacokinetics of S-1 on an oral daily schedule for 28 days in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:134–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, et al. Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safran H, Winter KA, Abrams RA, et al. Results of the randomized phase II portion of NRG Oncology/RTOG 0848 evaluating the addition of erlotinib to adjuvant gemcitabine for patients with resected pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:4007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1960–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1817–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Further evidence of effective adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection of pancreatic cancer. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Cancer 1987;59:2006–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garofalo MC, Regine WF, Tan MT. On statistical reanalysis, the EORTC trial is a positive trial for adjuvant chemoradiation in pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg 2006;244:332–3; author reply 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neoptolemos JP, Dunn JA, Stocken DD, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001;358:1576–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choti MA. Adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer--the debate continues. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abrams RA, Lillemoe KD, Piantadosi S. Continuing controversy over adjuvant therapy of pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2001;358:1565–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, et al. Fluorouracil vs. gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:1019–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrams RA, Winter KA, Regine WF, et al. Failure to adhere to protocol specified radiation therapy guidelines was associated with decreased survival in RTOG 9704--a phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy for patients with resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:809–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu CC, Herman JM, Corsini MM, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: the Johns Hopkins Hospital-Mayo Clinic collaborative study. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:981–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rutter CE, Park HS, Corso CD, et al. Addition of radiotherapy to adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with improved overall survival in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer 2015;121:4141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mellon EA, Springett GM, Hoffe SE, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and lymph node dissection in pancreatic cancer treated with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer 2014;120:1171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.You DD, Lee HG, Heo JS, et al. Prognostic factors and adjuvant chemoradiation therapy after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:1699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stocken DD, Buchler MW, Dervenis C, et al. Meta-analysis of randomised adjuvant therapy trials for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2005;92:1372–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yovino S, Maidment BW 3rd, Herman JM, et al. Analysis of local control in patients receiving IMRT for resected pancreatic cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;83:916–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nichols RC Jr., Huh SN, Prado KL, et al. Protons offer reduced normal-tissue exposure for patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy for resected pancreatic head cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;83:158–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nichols RC Jr., George TJ, Zaiden RA Jr., et al. Proton therapy with concomitant capecitabine for pancreatic and ampullary cancers is associated with a low incidence of gastrointestinal toxicity. Acta Oncol 2013;52:498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rwigema JC, Heron DE, Parikh SD, et al. Adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma with close or positive margins. J Gastrointest Cancer 2012;43:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunner TB, Merkel S, Grabenbauer GG, et al. Definition of elective lymphatic target volume in ductal carcinoma of the pancreatic head based on histopathologic analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;62:1021–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodman KA, Regine WF, Dawson LA, et al. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group consensus panel guidelines for the delineation of the clinical target volume in the postoperative treatment of pancreatic head cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;83:901–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caravatta L, Sallustio G, Pacelli F, et al. Clinical target volume delineation including elective nodal irradiation in preoperative and definitive radiotherapy of pancreatic cancer. Radiat Oncol 2012;7:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun W, Leong CN, Zhang Z, et al. Proposing the lymphatic target volume for elective radiation therapy for pancreatic cancer: a pooled analysis of clinical evidence. Radiat Oncol 2010;5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dholakia AS, Kumar R, Raman SP, et al. Mapping patterns of local recurrence after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a new approach to adjuvant radiation field design. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013;87:1007–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu W, Hu W, Shui Y, et al. Pancreatic cancer adjuvant radiotherapy target volume design: based on the postoperative local recurrence spatial location. Radiat Oncol 2016;11:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palta M, Willett C, Czito B. The Role of Intraoperative Radiation Therapy in Patients With Pancreatic Cancer. Seminars in Radiation Oncology 2014;24:126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willett CG, Czito BG, Tyler DS. Intraoperative radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:971–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sindelar WF, Kinsella TJ. Studies of intraoperative radiotherapy in carcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Oncol 1999;10 Suppl 4:226–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnstone PA, Sindelar WF. Patterns of disease recurrence following definitive therapy of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas using surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy:correlations of a clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1993;27:831–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reni M, Panucci MG, Ferreri AJ, et al. Effect on local control and survival of electron beam intraoperative irradiation for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001;50:651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alfieri S, Morganti AG, Di Giorgio A, et al. Improved survival and local control after intraoperative radiation therapy and postoperative radiotherapy: a multivariate analysis of 46 patients undergoing surgery for pancreatic head cancer. Arch Surg 2001;136:343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zerbi A, Fossati V, Parolini D, et al. Intraoperative radiation therapy adjuvant to resection in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Cancer 1994;73:2930–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Valentini V, Calvo F, Reni M, et al. Intra-operative radiotherapy (IORT) in pancreatic cancer: joint analysis of the ISIORT-Europe experience. Radiother Oncol 2009;91:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Showalter TN, Rao AS, Rani Anne P, et al. Does intraoperative radiation therapy improve local tumor control in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma? A propensity score analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:2116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ogawa K, Karasawa K, Ito Y, et al. Intraoperative radiotherapy for resected pancreatic cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective analysis of 210 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;77:734–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clark CE, Hingorani SR, Mick R, et al. Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res 2007;67:9518–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thind K, Padrnos LJ, Ramanathan RK, et al. Immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer treatment: a new frontier. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2017;10:168–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Picozzi VJ, Kozarek RA, Traverso LW. Interferon-based adjuvant chemoradiation therapy after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg 2003;185:476–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jaffee EM, Schutte M, Gossett J, et al. Development and characterization of a cytokine-secreting pancreatic adenocarcinoma vaccine from primary tumors for use in clinical trials. Cancer J Sci Am 1998;4:194–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jaffee EM, Hruban RH, Biedrzycki B, et al. Novel allogeneic granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-secreting tumor vaccine for pancreatic cancer: a phase I trial of safety and immune activation. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:145–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salman B, Zhou D, Jaffee EM, et al. Vaccine therapy for pancreatic cancer. Oncoimmunology 2013;2:e26662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lutz E, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, et al. A lethally irradiated allogeneic granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor-secreting tumor vaccine for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A Phase II trial of safety, efficacy, and immune activation. Ann Surg 2011;253:328–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Joziasse DH, Oriol R. Xenotransplantation: the importance of the Galalpha1,3Gal epitope in hyperacute vascular rejection. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999;1455:403–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hardacre JM, Mulcahy M, Small W, et al. Addition of algenpantucel-L immunotherapy to standard adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer: a phase 2 study. J Gastrointest Surg 2013;17:94–100; discussion p −1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Greenhalf W, Ghaneh P, Neoptolemos JP, et al. Pancreatic cancer hENT1 expression and survival from gemcitabine in patients from the ESPAC-3 trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:djt347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Farrell JJ, Elsaleh H, Garcia M, et al. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 levels predict response to gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 2009;136:187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakagawa N, Murakami Y, Uemura K, et al. Combined analysis of intratumoral human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) and ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M1 (RRM1) expression is a powerful predictor of survival in patients with pancreatic carcinoma treated with adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy after operative resection. Surgery 2013;153:565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richards NG, Rittenhouse DW, Freydin B, et al. HuR status is a powerful marker for prognosis and response to gemcitabine-based chemotherapy for resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients. Ann Surg 2010;252:499–505; discussion −6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maréchal R, Bachet JB, Mackey JR, et al. Levels of gemcitabine transport and metabolism proteins predict survival times of patients treated with gemcitabine for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012;143:664–74 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McAllister F, Pineda DM, Jimbo M, et al. dCK expression correlates with 5-fluorouracil efficacy and HuR cytoplasmic expression in pancreatic cancer: a dual-institutional follow-up with the RTOG 9704 trial. Cancer Biol Ther 2014;15:688–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hartwig W, Strobel O, Hinz U, et al. CA19–9 in potentially resectable pancreatic cancer: perspective to adjust surgical and perioperative therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:2188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ballehaninna UK, Chamberlain RS. The clinical utility of serum CA 19–9 in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An evidence based appraisal. J Gastrointest Oncol 2012;3:105–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Humphris JL, Chang DK, Johns AL, et al. The prognostic and predictive value of serum CA19.9 in pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1713–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Berger AC, Garcia M Jr., Hoffman JP, et al. Postresection CA 19–9 predicts overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer treated with adjuvant chemoradiation: a prospective validation by RTOG 9704. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5918–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Regine WF, Winter K, Kessel IL, et al. Prospective and Concurrent Analysis of Postresection CA19–9 Level and Surgical Margin Status (SMS) as Predictors of Pattern of Disease Recurrence Following Adjuvant Treatment for Pancreatic Carcinoma: NRG Oncology/RTOG 9704 Secondary Analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;93:S153. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lawrence YR, Moughan J, Magliocco AM, et al. Expression of the DNA repair gene MLH1 correlates with survival in patients who have resected pancreatic cancer and have received adjuvant chemoradiation: NRG Oncology RTOG Study 9704. Cancer 2018;124:491–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ben-Josef E, George A, Regine WF, et al. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta Predicts Survival in Resected Adenocarcinoma of the Pancreas. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:5612–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crane CH, Varadhachary GR, Yordy JS, et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin followed by chemoradiation with cetuximab for locally advanced (T4) pancreatic adenocarcinoma: correlation of Smad4(Dpc4) immunostaining with pattern of disease progression. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3037–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, et al. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1806–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Herman JM, Jabbour SK, Lin SH, et al. Smad4 Loss Correlates With Higher Rates of Local and Distant Failure in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Patients Receiving Adjuvant Chemoradiation. Pancreas 2018;47:208–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oshima M, Okano K, Muraki S, et al. Immunohistochemically Detected Expression of 3 Major Genes (CDKN2A/p16, TP53, and SMAD4/DPC4) Strongly Predicts Survival in Patients With Resectable Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg 2013;258:336–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1691–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]