Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To assess whether reductions in physical restraint use associated with quality reporting may have had the unintended consequence of increasing antipsychotic use in nursing home (NH) residents with severe cognitive impairment.

DESIGN:

Retrospective analysis of NH clinical assessment data from 1999 to 2008 comparing NHs subject to public reporting of physical restraints with nonreporting NHs.

SETTING:

Medicare-and Medicaid-certified NHs in the United States.

PARTICIPANTS:

Observations (N = 3.9 million) on 809,645 residents with severe cognitive impairment in 4,258 NHs in six states.

INTERVENTION:

Public reporting of physical restraint use rates.

MEASUREMENTS:

Use of physical restraints and antipsychotic medications.

RESULTS:

Physical restraint use declined significantly from 1999 to 2008 in NH residents with severe cognitive impairment. The decline was larger in NHs that were subject to reporting of restraints than in those that were not (–8.3 vs –3.3 percentage points, P < .001). Correspondingly, antipsychotic use in the same residents increased more in NHs that were subject to public reporting (4.5 vs 2.9 percentage points, P < .001). Approximately 36% of the increase in antipsychotic use may be attributable to public reporting of physical restraints.

CONCLUSION:

This analysis suggests that public reporting of physical restraint use had the unintended consequence of increasing use of antipsychotics in NH residents with severe cognitive impairment.

Keywords: nursing homes, restraints, antipsychotics, public reporting, quality

Caring for individuals with severe cognitive impairment in nursing homes (NHs) presents many challenges. Some of the most difficult challenges relate to behaviors often described as “agitation” or “aggression,” which may be a form of behavioral communication of distress resulting from declining verbal abilities associated with dementia, a primary cause of severe cognitive impairment. These behaviors can be dangerous to the residents themselves and to others and can be associated with more-rapid cognitive decline, greater impairment in activities of daily living, and poorer quality of life. Also, persons with cognitive impairment often experience difficulty accommodating to the structure and environment of the NH, further escalating the behavior expressions of distress. In response, physical restraints or antipsychotic medications may be used in NH residents with cognitive impairment.

The use of physical restraints for NH residents is now widely accepted as a sign of poor quality of care. As a result, reducing physical restraints has been a seemingly uncontroversial goal of NH quality improvement efforts1 in the United States since the Institute of Medicine documented abuses of NH care in the 1980s2 and the subsequent Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1987 that saw freedom from unnecessary physical and chemical restraints (such as inappropriate use of antipsychotic medications) as a right of all NH residents.

Report cards have become a prominent part of the quality improvement landscape over the last quarter-century across the healthcare spectrum in the United States and Europe. As part of broad efforts to improve the quality of NH care in the United States, in 2002, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) initiated a program for publicly reporting information about NHs. The CMS NH report card is a Web-based guide called Nursing Home Compare (NHC), which publicly rates NHs at Medicare-and Medicaid-certified NHs3 and includes a measure of physical restraint use.

Under public reporting, the issue is often raised that healthcare providers may focus on aspects of quality that are reported to the possible detriment of aspects that are unreported. Physical restraints and antipsychotic medications may be seen as alternative ways for NH staff to address behavioral expressions associated with severe cognitive impairment. Thus, efforts to reduce restraint use raise new concerns that antipsychotic medications will be used instead. This is particularly troubling because rates of antipsychotic use were often not included in quality improvement programs targeting physical restraints. In particular, rates of antipsychotic use were not publicly monitored as part of NHC until July 2012, perhaps inadvertently leading NHs subject to public reporting to increase use of antipsychotic medications while reducing physical restraints.

Overuse of antipsychotics in NH residents with dementia, especially off-label use of atypical antipsychotics, has been identified as a substantial problem.2,4 There have been numerous calls to limit and reduce use of antipsychotics for dementia-related behavior problems.5–11 With mounting evidence that off-label use of atypical antipsychotics in individuals with dementia have limited efficacy and are associated with risk of hospitalization and death,12–17 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning in April 2005 reiterating that they are “not approved for dementia-related psychosis” and describing the risks of atypical antipsychotic use in elderly adults with dementia.18–20 This led to some decline in their use.21 In March 2012, CMS launched a multifaceted initiative aimed at reducing the unnecessary use of antipsychotic medications in NHs, including the inclusion of an antipsychotics measure in NHC, raising public awareness, regulatory oversight, technical assistance, training, and research.22 Nonetheless, rates of antipsychotic use remain unacceptably high in NHs.23–25

The main objective of this study was to examine whether reductions in physical restraint use under NHC may have had the unintended consequence of increasing antipsychotic use in NH residents with severe cognitive impairment. One study from the 1990s examined this trade-off in response to regulatory incentives and did not find that NHs increased antipsychotic use when decreasing restraint use.26 Subsequent, larger studies of the NH sector have found evidence that providers generally shift focus to targeted quality under regulatory enforcement and public reporting27–30 and respond to market pressures such as higher nurse wages by increasing the use of antipsychotic medications in place of increasing nurse staff hours,31 but to the knowledge of the authors of the current article, no prior work has rigorously analyzed changes in restraint and antipsychotic use as a consequence of public reporting incentives. This study takes advantage of a major public policy initiative, the initiation of public reporting for physical restraints under NHC, to quantify this unintended adverse consequence of well-intentioned efforts to reduce physical restraint use.

METHODS

Data

The analysis used the NH Minimum Data Set (MDS) 2.0 clinical assessment data, which are collected at regular intervals for every resident in a Medicare- or Medicaid-certified NH regardless of individual payer source. The MDS data were merged with facility-level staffing data taken from the CMS Online Survey Certification and Reporting database.

Study Population

The sample comprised MDS assessments from six states (California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, and Texas), chosen because they are geographically diverse and large, totaling approximately 20% of all NH residents in the United States. All chronic-care residents of NHs that appeared in MDS in those states from 1999 to 2008 were included, spanning 2002 when NHC was released and 2005 when the black box warning was issued. Consistent with the use of these data by CMS for quality reporting, the sample was limited to the last annual, admission, quarterly, or significant change assessment per resident per quarter to avoid overweighting residents with more available assessments. The 17.1% of residents with severe cognitive impairment were then predominantly focused on, because they are more likely to exhibit the behavioral expressions that may prompt restraint use and, if ignored, may lead to falls, interference with treatments, wandering, and aggressive behavior.32 Severe cognitive impairment was defined based on the Cognitive Performance Score (CPS), a well-validated tool for categorizing cognitive impairment using MDS data.33 A CPS of 0 to 1 indicates the absence of cognitive impairment, a score of 2 to 4 indicates mild to moderately severe cognitive impairment, and a score of 5 or 6 indicates severe or very severe impairment, characterized by severely impaired decision-making and total dependence in eating; this last group was the group that was focused on. The modal diagnosis associated with a CPS of 5 or 6 is Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, although residents in a coma or with other neurological diagnoses are also included.33 It was decided to use the CPS rather than relying on diagnoses because of known uneven and underdiagnosis of dementia in NHs and because similar challenges of treatment for persons with cognitive impairment may exist even in the absence of dementia. The sample of NH residents with severe cognitive impairment was 68% female and had an average age of 81.5 ±13.6.

Two groups of NHs were included: those that were subject to public reporting of the physical restraints measure after NHC was implemented and those that were not. NHC is mandatory for all Medicare- and Medicaid-participating NHs but is subject to minimum denominator requirements for each measure. If a facility has fewer than 30 chronic-care residents during a quarter, the restraints measure is not publicly reported because the estimates may not be reliable enough for reporting at the individual facility level and may jeopardize resident anonymity. Generally, NHs subject to reporting of restraints in the sample were larger, more likely to be for-profit, and less likely to be hospital-based than the smaller facilities that were exempted from reporting of restraints because they did not meet minimum denominator requirements. Facilities that reported rates of physical restraint use in some but not all quarters (28% of NHs, 17% of observations) were excluded because it is unclear how these NHs should respond to public reporting incentives.

Measures

Two primary outcome measures (physical restraint use and antipsychotic use) calculated directly from the MDS were examined. The quality measures are reported in NHC as percentages, with the numerator the number of residents who triggered the numerator and the denominator the total number residents. Because the analyses were run at the individual level, the measure was defined as a dichotomous yes-or-no outcome for each eligible observation. The technical definition of the physical restraint quality measure provided by CMS (whether there was daily use of physical restraints in the previous 7 days)34 was used to calculate each resident’s outcome each quarter.

For antipsychotic use, the numerator was defined as 1 if any antipsychotic was used in the previous 7 days and 0 otherwise, consistent with the numerator of the CMS definition.34 Specific drug names were not available in the data. Antipsychotic use was examined in the same population used for the physical restraints measure, maintaining an identical sample for the two outcomes over time. This allowed the trade-off between physical restraint and antipsychotic medication use for the same residents to be assessed directly.

Analysis

First, trends in restraint use were examined according to cognitive impairment. It was expected that individuals with severe cognitive impairment would have higher initial rates of restraint use and larger declines in restraint use after public reporting was initiated. Subsequently, the population of NH residents classified as having severe cognitive impairment (CPS 5 or 6) was focused on, and trends in the use of physical restraints and antipsychotics were examined. All analyses were performed using Stata MP 12 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

The remainder of the empirical approach rested on comparing changes in physical restraint use in NHs from 1999 to 2008 with changes in antipsychotic use for the same population during the same period. The specific hypotheses were threefold. First, NH residents with severe cognitive impairment would experience significant declines in physical restraint use with the institution of NHC. Second, during this same time period, antipsychotic use in NH residents with severe cognitive impairment would increase. Third, the degree of reduction in restraint use and the increase in antipsychotic use would be larger in NHs subject to public reporting of the physical restraints measure.

These hypotheses were examined in two ways. First, trends in restraint and antipsychotic use in NHs subject to public reporting and in those exempt from public reporting were examined descriptively. Second, a difference-in-differences model was used to test whether any observed differences in physical restraints and antipsychotics could plausibly be attributed to public reporting of restraint use. Difference-in-differences models use a naturally occurring nontreatment group in observational data to control for secular trends, measuring the treatment effect as the treatment group change in addition to the change in the control group. For the current difference-in-differences model, changes were examined in the two outcomes of interest, physical restraint and antipsychotic use, before and after public reporting was started. This change in facilities subject to public reporting was then compared with the change in facilities exempt from public reporting. NHs that were not subject to reporting of the restraints measure were thus used as a control group with which to measure and control for secular trends in both outcomes. It is not necessary in a difference-in-differences model that the control group and the treatment group be similar; the main assumption underlying the validity of the model is that trends in the outcome in the two groups is arguably similar over time in the absence of treatment, even if an absolute difference between them remains. The estimate is thus based solely on differences in the trends between the two groups, and absolute differences are controlled. The estimates from the difference-in-differences model reflect the extent to which the changes can be plausibly attributed to NHC. Significance of the difference-in-differences estimates was tested using linear regression.

Although the assumptions of the difference-in-differences estimator are not violated if the treatment and control groups are not similar, the plausibility that the two groups would experience similar trends in the absence of treatment (e.g., due to changes in the availability of antipsychotic medications) may be enhanced if the two groups are not markedly different. Thus, a robustness check was conducted using only NHs in the bottom tertile of NHs subject to NHC in terms of the number of assessments qualifying for the restraint measure as the treatment group.

The difference-in-differences model measured changes in outcomes before and after the launch of public reporting in 2002. For most of the sample (California, Illinois, New York, Texas), this launch was in November 2002; for the two states in the sample that participated in a NHC pilot program (Florida and Ohio), the release date for the initial set of reported measures was April 2002, 7 months before the national launch.

To adjust for potential changes in case-mix, resident age, age squared, sex, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, aphasia, cerebral palsy, stroke, muscular sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, seizure disorder, transient ischemic attack, anxiety disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, cancer, and renal failure were controlled for. The difference-in-differences estimates were regression-adjusted for these variables. The effect of the release of the black box warning in these difference-in-differences models was also controlled for by calculating separate rates of physical restraint and antipsychotic medication use for each group after April 2005; thus, the NHC effect was calculated net of this subsequent change.

Finally, the role of staffing in NHs subject to public reporting was explored, because NHs with higher levels of staffing may have been better able to reduce physical restraint use without increasing use of antipsychotic medications. Total hours of direct-care staffing (including licensed nurse and nurse aide hours) per resident day was calculated using a standard algorithm,35 and the average for each NH over the entire study period was calculated such that a NH’s classification did not change over time. Low-staffed NHs were defined as those at or below the median and high-staffed NHs as those above the median of 3.19 hours. Trends in physical restraint use and antipsychotic use were examined and stratified according to staffing.

The institutional review board of the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division approved this research.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes and stratifies according to reporting status the full sample and the subsample with severe cognitive impairment. The main analysis subsample of NH residents with severe cognitive impairment included 3.9 million observations in 809,645 chronic-care residents in 4,258 NHs.

Table 1.

Description of Nursing Homes (NHs) in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, and Texas: 1999–2008

| Sample | NHs Not Subject to Reporting of Restraints | NHs Subject to Reporting of Restraints | NHs in Smallest One-Third of Number of Assessments of Those Subject to Reporting of Restraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | 637 | 3,634 | 1,231 |

| NHs, n | |||

| Residents, n | 419,859 | 4,488,332 | 692,127 |

| Resident-level observations, n | 717,642 | 22,660,039 | 4,274,016 |

| Residents with no cognitive impairment,% | 62.5 | 29.7 | 26.9% |

| Residents with mild to moderately severe cognitive impairment, % | 27.1 | 53.4 | 55.3% |

| Residents with severe or very severe cognitive impairment,% | 10.2 | 16.8 | 17.8% |

| Analysis sample of residents with severe cognitive impairment, n | |||

| NHs | 626 | 3,632 | 1,229 |

| Residents | 35,172 | 774,473 | 146,292 |

| Resident-level observations | 73,547 | 3,816,234 | 760,591 |

The sample omits NHs that are sometimes, but not always, subject to public reporting of the restraints measure on Nursing Home Compare.

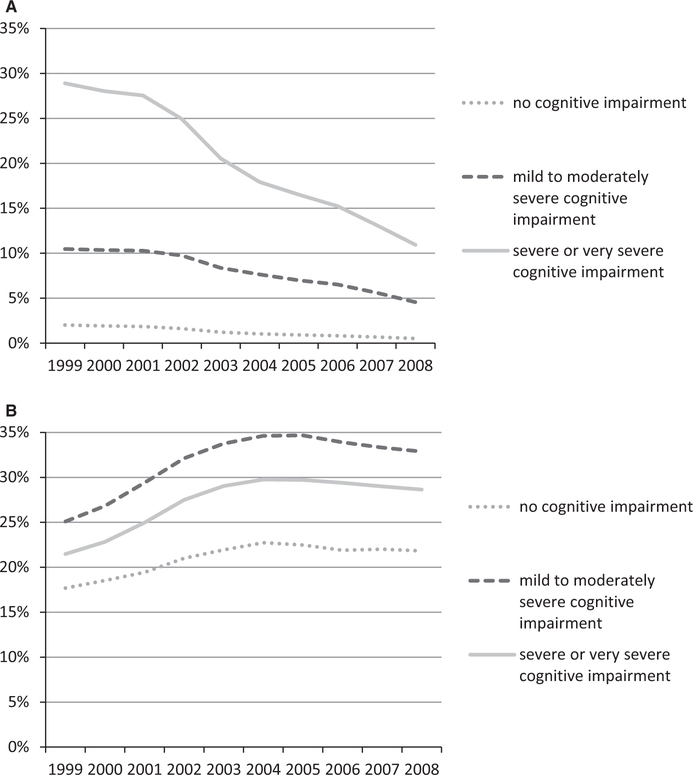

Figure 1 displays the decline in restraint use stratified according to cognitive impairment in the full sample. NH residents with severe cognitive impairment had higher rates of physical restraint use at baseline and experienced a steeper decline in their use throughout the study period than residents with moderate or no cognitive impairment. This determined the focus for the remainder of the analysis on the group of residents with severe cognitive impairment.

Figure 1.

(A) Physical restraint and (B) Antipsychotic use in nursing homes according to cognitive impairment, 1999–2008. Sample comprises 23,377,681 resident-level observations from 4,272 nursing homes in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, and Texas that were subject to public reporting of physical restraints.

In residents with severe cognitive impairment, a marked increase in antipsychotic use accompanied the decline in physical restraint use. Figure 2 displays trends in physical restraint use over the study period for NHs subject to public reporting of restraints (but not antipsychotics) and NHs not subject to reporting. Both groups of NHs reduced restraints, but after 2002, when NHC was initiated, the decline was steeper in reporting homes. Figure 2 also displays rates of antipsychotic medication use in the same groups of facilities in the same residents. NHs subject to public reporting of physical restraints exhibited an increase in antipsychotic medication use between 2002, when NHC was initiated, and 2005, when the black box warning was issued, but there was no substantial upward trend in antipsychotic use in nonreporting facilities during this time.

Figure 2.

Physical restraints and antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment, 1999–2008. Sample comprises 3,889 ,781 resident-level observations from 4,258 nursing homes in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, and Texas that were subject to public reporting of physical restraints.

Antipsychotic use flattened out similarly for both groups of NHs after the black box warning was issued in 2005, although by the end of the study period, absolute rates of use remained higher at NHs subject to reporting of restraints.

The difference-in-differences results in Table 2 quantify and statistically test whether the trends noted in the figure were plausibly related to the initiation of public reporting. The decline in physical restraints between the baseline period (1999–2001) and the NHC period (2002-early 2005) was 5.0 percentage points greater for reporting facilities than nonreporting facilities (P < .001), suggesting that approximately 60% of the total 8.3-percentage-point decline in restraint use in residents with severe cognitive impairment during that time was plausibly attributable to public reporting of rates of restraint use. Similarly, the increase in antipsychotic use was 1.6 percentage points higher for reporting facilities than nonreporting facilities (P < .001), suggesting that approximately 36% of the 5.7-percentage-point increase in antipsychotic use was plausibly attributable to public reporting of restraints.

Table 2.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Effects of Publicly Reporting Physical Restraints in Nursing Home Residents with Severe Cognitive Impairment

| Estimate | Before NHC | After NHC | Before and After NHC, Percentage Point Difference | After Black Box Warning Rate of Use, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of Use, % | ||||

| Physical restraints | ||||

| Reporting facilities | 28.9 | 20.5 | −8.3a | 13.9 |

| Nonreporting facilities | 17.7 | 14.4 | −3.3a | 7.8 |

| Difference between reporting and nonreporting facilities | −5.0a | |||

| Antipsychotics | ||||

| Reporting facilities | 22.4 | 26.8 | 4.5a | 25.3 |

| Nonreporting facilities | 20.8 | 23.7 | 2.9a | 22.2 |

| Difference between reporting and nonreporting facilities | 1.6a | |||

Numbers are regression-adjusted for resident age, age squared, sex, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, aphasia, cerebral palsy, stroke, muscular sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, seizure disorder, transient ischemic attack, anxiety disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, cancer, and renal failure.

P < .001.

NHC = Nursing Home Compare.

The results of the robustness check using only the one-third of the NHs subject to NHC with the smallest number of assessments as the treatment group revealed slightly larger magnitudes of effect: an estimated reduction in restraint use of 6.9 percentage points and an increase in antipsychotic use of 2.4 percentage points associated with public reporting on NHC. Thus, potential differences in trends in the large facilities were not biasing the analysis substantially.

Finally, Figure 3 depicts the results of exploratory examination of the role of staffing, showing trends in both outcomes stratified according to level of direct-care staffing. Low-staffed NHs began with rates of restraint use that were 2 percentage points higher, but by 2004 the downward trends in low-staffed and high-staffed NHs converged. Antipsychotic use was 6 percentage points higher in low-staffed facilities than in high-staffed facilities at baseline and remained so throughout the study period; the groups experienced a parallel increase under NHC. Thus, higher staffing levels may have enabled NHs to maintain lower rates of antipsychotic use, consistent with prior literature,31 but did not prevent an increase in antipsychotic use when faced with pressure to lower physical restraint use.

Figure 3.

Trends in physical restraint and antipsychotic use in nursing home (NH) residents with severe cognitive impairment according to NH staffing level: 1999–2008. Sample comprises 3,889,781 resident-level observations from 4,258 NHs in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, and Texas subject to public reporting of physical restraints. Staffing is classified as low if total nurse hours per resident-day is at or equal to the median of 3.19 and as high if greater than the median.

DISCUSSION

Antipsychotic use increased under NHC in NH residents with severe cognitive impairment. Efforts to reduce the use of physical restraints seem to have driven this increase.

These results provide compelling evidence that aspects of quality that are targeted in quality improvement efforts and incentives will receive attention, whereas other, non-targeted areas may be neglected and even worsen. The focus of public reporting on reducing rates of physical restraint use seems to drive in part the increase in antipsychotic use. This example is a particularly compelling one because the area of quality that was neglected—antipsychotic use—is arguably as important and consequential for quality of care and life as the physical restraints that were targeted.

The behavior of reporting and nonreporting NHs provides interesting nuances. The fact that both decreased physical restraint use is consistent with widespread emphasis on reduction of physical restraints that extends beyond public reporting. Dramatic reductions in physical restraint use over the past few decades should be viewed as a practice and policy success. The inclusion of the physical restraints measure in NHC appears to have enhanced these other efforts, resulting in even greater declines in physical restraint use, which may be viewed as a success of public reporting, but facilities subject to public reporting of physical restraints also increased use of antipsychotics to a greater extent. It is not clear that the reporting of restraints was a resounding success when viewed in this broader context.

These results should be viewed in light of several limitations. First, the specific antipsychotics prescribed cannot be determined in the data used, nor can their potential clinical appropriateness be determined. Second, the sample of six large states may not generalize to the entire United States. Third, the staffing results are descriptive and exploratory and may not reflect a causal relationship. Fourth, the results may be biased if reporting and nonreporting NHs changed their decisions about which residents to accept in ways that were not measured. Finally, the validity of the difference-in-differences estimate rests on the assumption that trends in nonreporting facilities reflect secular trends that reporting facilities would have experienced in the absence of NHC. If this assumption does not hold, the estimates of attribution to NHC may be biased. Tests of trends before the intervention show that trends in antipsychotic use were not significantly different between the treatment and control facilities, bolstering confidence in the equal trends assumption. Trends in restraint use were slightly but statistically significantly different; nonreporting facilities showed a steeper decline. The estimates of attribution are therefore an approximation in the case of restraints. Although the two groups were different from each other at baseline (e.g., nonreporting facilities were smaller), this does not affect validity as long as the similar trends assumption is not violated.

These results underscore the fact that the effort to reduce physical restraints involves trade-offs. The withdrawal of physical restraints appears to leave a void that the evidence suggests the increased use of antipsychotics is filling. One alternative to either is to substantially increase direct-care staffing to provide extensive monitoring and treatment of NH residents with severe cognitive impairment who may present risks to themselves or others.36–38 Increases in activities staff or improved education of all staff may also help. Additionally, dementia-specific programming and environmental changes have been advocated to address challenges resulting from nonverbal expression of distress of residents with dementia.39 Although increased staffing has long been advocated as important to improving the quality of NH care,40 current budgetary constraints make this solution highly unlikely, and the current results suggest that higher staffing may ameliorate but not eliminate this problem. Thus, although the use and overuse of antipsychotics is a high-profile quality concern and may present serious risks to NH residents with dementia or other conditions associated with cognitive impairment, given the taboos against physical restraints and the lack of more-appealing approaches, it may remain the primary choice. Continued efforts to improve the culture of NHs to one that builds on relationships between staff and residents and attempts to maximize quality of life may help.

The recent addition of an antipsychotics measure to NHC is a move in the right direction. With both measures in use, the unintended provisions of incentives for antipsychotic use may be diminished, although this cannot solve the underlying problem that individuals with severe cognitive impairment present behavior that is challenging to interpret, prevent, or manage, contributing to continuing use of physical restraints or antipsychotic medications. In the worst case, the reporting of both measures could lead (on the margin) to excluding these residents from some facilities, through admissions policies or greater tendency to hospitalize. This highlights the challenges associated with targeting difficult-to-improve quality problems.

This analysis provides evidence that NH providers, in the presence of public report cards, may focus on targeted aspects of quality to the detriment of nontargeted aspects. This parallels the phenomenon of “teaching to the test” in education, in which emphasis is placed on improving student performance on items expected to appear on standardized tests to the potential detriment of the broader educational experience. 41

These findings are important in that they expose an important and unintended consequence of public reporting that may actually result in overall worse care, even as public reporting policies become more and more popular worldwide as a quality improvement tool. Use and potential overuse of physical restraints and antipsychotics in NH residents with severe cognitive impairment are well-known problems, yet policies designed to decrease use of one have had the unintended consequence of increasing use of the other. The recent addition of antipsychotic use rates to NH report cards in the United States may address this issue in the sense of equalizing transparency. It will be interesting to see what happens with this equalization. Ultimately, more research is needed on approaches and interventions that help prevent and modify behavioral expressions that can result in harm to residents and staff or are indicative of distress in persons with severe cognitive impairment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

This research was funded through Grant R01HS018718 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Freedom from Unnecessary Physical Restraints: Two Decades of National Progress in Nursing Home Care Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine Committee on Nursing Home Regulation. Improving the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nursing Home Compare. 2002. [on-line]. Available at http://www.medicare.gov/Nhcompare/Home.asp Accessed April 21, 2005.

- 4.Feng ZL, Hirdes JP, Smith TF et al. Use of physical restraints and antipsychotic medications in nursing homes: A cross-national study. Int J Geriatr Psych 2009;24:1110–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spore DL, Horgas AL, Smyer MA et al. The relationship of antipsychotic drug use, behavior, and diagnoses among nursing home residents. J Aging Health 1992;4:514–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray WA, Taylor JA, Meador KG et al. Reducing antipsychotic drug use in nursing homes. A controlled trial of provider education. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamble P, Chen H, Sherer J et al. Antipsychotic drug use among elderly nursing home residents in the United States. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2008;6:187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison A Antipsychotic prescribing in nursing homes: An audit report. Qual Prim Care 2009;17:359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCleery J, Fox R. Antipsychotic prescribing in nursing homes. BMJ 2012;344:e1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitka M CMS seeks to reduce antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with dementia. JAMA 2012;308:119, 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitby P Improve environment to reduce pressure to prescribe antipsychotic drugs in nursing homes. BMJ 2012;344:e2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee PE, Gill SS, Freedman M et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: Systematic review. BMJ 2004;329:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: Meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005;294:1934–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sikand H, Jaojoco J, Linares L et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs, dementia, and risk of death. JAMA 2006;295:495; author reply 496–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atypical antipsychotic agents ineffective for AD. Duke Med Health News 2007;13:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rochon PA, Normand SL, Gomes T et al. Antipsychotic therapy and short-term serious events in older adults with dementia. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1090–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch C Continued use of antipsychotic drugs increased long-term mortality in patients with Alzheimer disease. Evid Based Med 2009;14:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.New warning on antipsychotic drugs used to treat older people. FDA Consum 2005;39:2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuehn BM. FDA warns antipsychotic drugs may be risky for elderly. JAMA 2005;293:2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenzer J FDA warns about using antipsychotic drugs for dementia. BMJ 2005;330:922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai VC, Heaton PC, Kelton CM. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration’s antipsychotic black box warning on psychotropic drug prescribing in elderly patients with dementia in outpatient and office-based settings. Alzheimers Dement 2012;8:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Initiative to Improve Behavioral Health and Reduce the Use of Antipsychotic Medications in Nursing Homes Residents Video Streaming Event, 2012. Available at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Spotlight.html Accessed July 9, 2013.

- 23.Briesacher BA, Tjia J, Field T et al. Antipsychotic use among nursing home residents. JAMA 2013;309:440–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustafsson M, Karlsson S, Lovheim H. Inappropriate long-term use of antipsychotic drugs is common among people with dementia living in specialized care units. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2013;14:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamble P, Sherer J, Chen H et al. Off-label use of second-generation antipsychotic agents among elderly nursing home residents. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegler EL, Capezuti E, Maislin G et al. Effects of a restraint reduction intervention and OBRA ‘87 regulations on psychoactive drug use in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng L Multitasking, information disclosure, and product quality: Evidence from nursing homes. J Econ Manag Strategy 2012;21:673–705. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Kruse GB. Impact of public reporting on unreported quality of care. Health Serv Res 2009;44:379–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowblis JR, Crystal S, Intrator O et al. Response to regulatory stringency: The case of antipsychotic medication use in nursing homes. Health Econ 2012;21:977–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukamel DB, Spector WD, Zinn J et al. Changes in clinical and hotel expenditures following publication of the nursing home compare report card. Med Care 2010;48:869–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grabowski DC, Bowblis JR, Lucas JA et al. Labor prices and the treatment of nursing home residents with dementia. Int J Econ Business 2011;18:273–292. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamers JP, Huizing AR. Why do we use physical restraints in the elderly? Z Gerontol Geriatr 2005;38:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol 1994;49:M174–M182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris J, Moore T, Jones R et al. Validation of Long-Term and Post-Acute Care Quality Indicators. Final Report Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abt Associates. Phase II of Final Report to Congress: Appropriateness of Minimum Nurse Staffing Ratios in Nursing Homes Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castle NG. Nursing homes with persistent deficiency citations for physical restraint use. Med Care 2002;40:868–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park J, Stearns SC. Effects of state minimum staffing standards on nursing home staffing and quality of care. Health Serv Res 2009;44:56–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowblis JR. Staffing ratios and quality: An analysis of minimum direct care staffing requirements for nursing homes. Health Serv Res 2011;46: 1495–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kopke S, Muhlhauser I, Gerlach A et al. Effect of a guideline-based multi-component intervention on use of physical restraints in nursing homes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012;307:2177–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wunderlich G, Kohler P, eds. Improving the Quality of Long-Term Care Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popham WJ. Teaching to the test? Educ Leadersh 2001;58:16–20. [Google Scholar]