Abstract

Background

The direct lateral approach to THA provides good exposure and is associated with a low risk of dislocations, but can result in damage to the abductor muscles. The direct anterior approach does not incise muscle, and so recovery after surgery may be faster, but it has been associated with complications (including fractures and nerve injuries), and it involves a learning curve for surgeons who are unfamiliar with it. Few randomized trials have compared these approaches with respect to objective endpoints as well as validated outcome scores.

Questions/purposes

The purpose of this study was to compare the direct anterior approach with the direct lateral approach to THA with respect to (1) patient-reported and validated outcomes scores; (2) frequency and persistence of abductor weakness, as demonstrated by the Trendelenburg test; and (3) major complications such as infection, dislocation, reoperation, or neurovascular injury.

Methods

We performed a randomized controlled trial recruiting patients from January 2012 to June 2013. One hundred sixty-four patients with end-stage osteoarthritis were included and randomized to either the direct anterior or direct lateral approach. Before surgery and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, a physiotherapist recorded the Harris hip score (HHS), 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), and performed the Trendelenburg test directly after the 6MWD. The patients completed the Oxford Hip Score (OHS) and the EQ-5D. The groups were not different at baseline with respect to demographic data and preoperative scores. Both groups received the same pre- and postoperative regimes. Assessors were blinded to the approach used. One hundred fifty-four patients (94%) completed the 2-year followup; five patients from each group were lost to followup.

Results

There were few statistical differences and no clinically important differences in terms of validated or patient-reported outcomes scores (including the HHS, 6MWD, OHS, or EQ-5D) between the direct anterior and the lateral approach at any time point. A higher proportion of patients had a persistently positive Trendelenburg test 24 months after surgery in the lateral approach than the direct anterior approach (16% [12 of 75] versus 1% [one of 79]; odds ratio, 15; p = 0.001). Irrespective of approach, those with a positive Trendelenburg test had statistically and clinically important worse HHS, OHS, and EQ-5D scores than those with a negative Trendelenburg test. There were four major nerve injuries in the direct anterior group (three transient femoral nerve injuries, resolved by 3 months after surgery, and one tibial nerve injury with symptoms that persist 24 months after surgery) and none in the lateral approach.

Conclusions

Based on our findings, no case for superiority of one approach over the other can be made, except for the reduction in postoperative Trendelenburg test-positive patients using the direct anterior approach compared with when using the direct lateral approach. Irrespective of approach, patients with a positive Trendelenburg test had clinically worse scores than those with a negative test, indicating the importance of ensuring good abductor function when performing THA. The direct anterior approach was associated with nerve injuries that were not seen in the group treated with the lateral approach.

Level of Evidence

Level I, therapeutic study.

Introduction

THA is one of the most effective interventions in modern medicine [24], providing long-term pain relief and restoration of function in patients with end-stage osteoarthritis [7], but there is no consensus as to which surgical approach is best. The direct lateral approach described by Hardinge [18] has been used with good results for many years [5]. The release of the gluteus minimus and the anterior third of the gluteus medius provides good access but can lead to trochanteric pain [20] and gluteal insufficiency [3]. In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in the Smith-Petersen approach [45]. The modified form, often referred to as the direct anterior approach, utilizes the intermuscular and internervous interval between the tensor fascia latae and the sartorius muscles superficially and, more deeply, between the gluteus medius and the rectus femoris. Some studies suggest this approach is associated with a shorter recovery period [11, 32, 56], less postoperative pain [15, 33], and decreased risk of revision [34, 44]. On the other hand, others suggest that the direct anterior approach is associated with a higher risk of complications including fractures [22], nerve injuries [54], and premature revisions [13, 31, 57], and serious concerns have been raised about the increase in complications during the learning curve for surgeons who are not familiar with it [22, 46, 54].

Given that the two approaches both are in common use and given that both seem to have advantages and disadvantages, well-controlled and ideally randomized studies comparing them are especially important. Unfortunately, only a few such studies have been done [11], and many of these studies leave important questions unanswered or have methodologic shortcomings. A meta-analysis by Yue et al. [56] comparing the direct anterior and the direct lateral approach found only 12 studies to include of which only two were randomized controlled trials [33, 42]. Several retrospective studies compare patients before and after introducing the direct anterior approach [1, 15, 40, 41, 51], leaving questions about the influence of the learning curve and patient matching. Other studies focus solely on the in-hospital period with no further followup [1, 15, 33] and others only on revisions as an endpoint [13, 31, 34, 44, 57] with no information on outcome scores or patient-reported data.

In the context of a randomized controlled trial, we compared the direct anterior approach with the direct lateral approach to THA with respect to (1) patient-reported and validated outcomes scores; (2) frequency and persistence of abductor weakness, as demonstrated by the Trendelenburg test; and (3) major complications such as infection, dislocation, reoperation, or neurovascular injury.

Materials and Methods

This randomized controlled trial performed at a nonteaching hospital in the south of Norway was approved by the regional ethics committee and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01578746). Approval to conduct the study according to the protocol and to collect data was given by the hospital’s research department.

In our institution, we used the direct lateral approach for several years before making the transition to the direct anterior approach in November 2009. Five surgeons (KEM, KK, SS, PA, TF) with previous experience with the direct lateral approach started using the direct anterior approach as a result of ongoing concerns with persistent abductor weakness after surgery. After having collectively performed several hundred THAs using the approach [6, 10], we wanted to perform a prospective, randomized trial to see if the approach led to better clinical results than the direct lateral approach.

Candidates for inclusion were patients with clinical end-stage osteoarthritis confirmed by plain radiographs and aged between 20 and 80 years. Written informed consent had to be signed to participate. Exclusion criteria were previous surgery of the included hip, body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m2, an explicit request regarding approach as well as dementia/psychiatric illness, or inadequate language skills preventing followup.

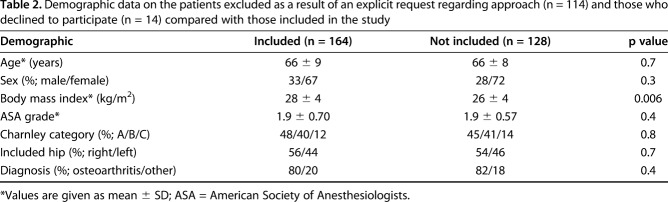

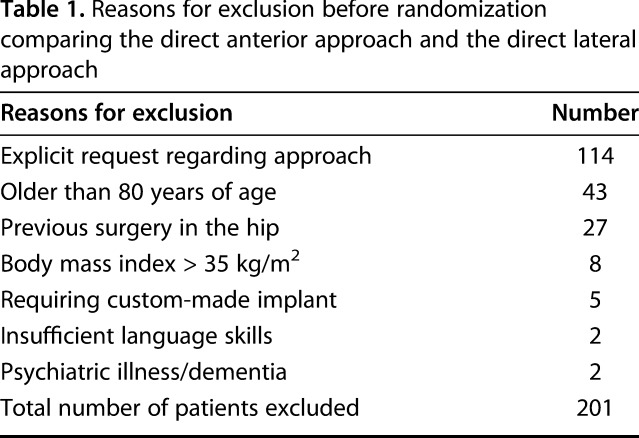

During the inclusion period of January 2012 to June 2013, all 379 primary THAs performed in our hospital were considered for inclusion. Of these, 201 patients were excluded based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 1). Patients who sought out our hospital because they explicitly wanted the direct anterior approach were not asked to participate as a result of the likely bias of them believing the direct anterior approach was better. Demographic data on these patients and those who declined to participate are compared with those included (Table 2). Fourteen declined to participate, yielding 164 patients to be randomized.

Table 1.

Reasons for exclusion before randomization comparing the direct anterior approach and the direct lateral approach

Table 2.

Demographic data on the patients excluded as a result of an explicit request regarding approach (n = 114) and those who declined to participate (n = 14) compared with those included in the study

The allocation sequence was generated by two of the authors (KEM, KK) by drawing from box notes with the word “anterior” or “lateral” hidden on them and placing them in opaque, sealed envelopes [43]. The envelopes were then drawn from a box again and sequentially numbered. The sequence was concealed until assignment, which was done the day before surgery. Eighty-four patients were allocated to the direct anterior approach and 80 patients to the direct lateral approach. There was no crossover between the study groups, and so all analyses were based on intention-to-treat principles.

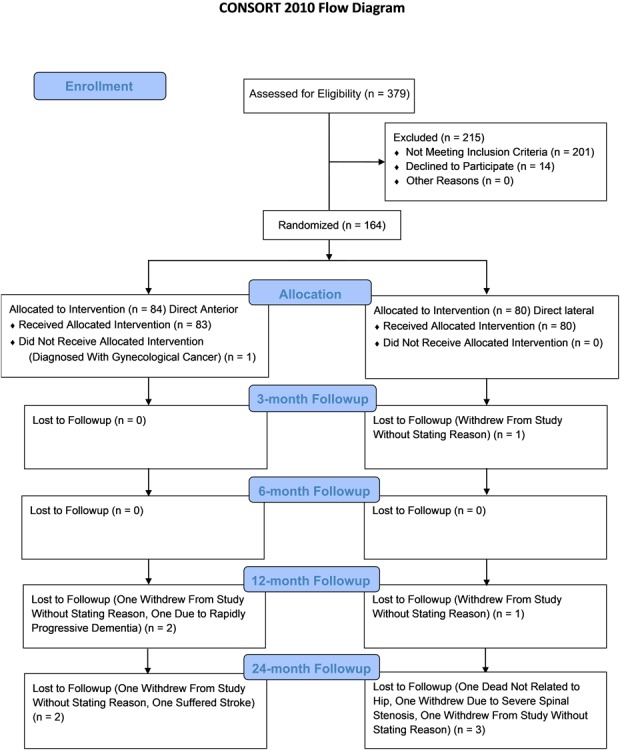

One patient from the direct anterior group withdrew before surgery as a result of being diagnosed with cancer, resulting in 83 patients receiving THA in the direct anterior group and 80 in the direct lateral group. Of the 164 randomized patients, 154 patients (94%) completed the 24-month followup with five patients lost in each group. One patient in the direct anterior group sustained an atraumatic brain hemorrhage 20 months after the THA resulting in total aphasia preventing followup and one withdrew as a result of rapidly progressing dementia. In the direct lateral group, one American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Grade 3 patient with morbus Parkinson disease died of an unknown cause 22 months after the THA and one patient withdrew stating that unsuccessful surgery of her spinal stenosis prevented further participation in the study. The other patients lost to followup did not state any reason (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram showing the recruitment and flow of patients.

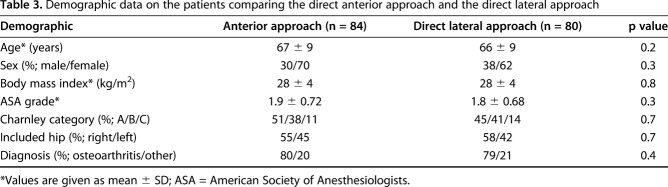

Baseline demographic data recorded before surgery were age and sex, BMI, ASA grade, and Charnley category [8]. Only one hip per patient was included and diagnosis leading to THA was recorded. The groups were not different at baseline with respect to demographic data (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic data on the patients comparing the direct anterior approach and the direct lateral approach

Preoperatively, and at all followup visits, all patients completed the Oxford Hip Score (OHS) [9, 35] and the EQ-5D HRQoL [14]. The OHS is a hip-specific patient-reported outcome measure in which the patient reports on 12 different aspects of hip function with scores ranging from 0 to 48 with 48 being the best. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) is 5 [4]. The EQ-5D-3L was used. This consists of five dimensions with three levels from which an EQ-5D index is calculated, the best possible score being 1 and lower, sometimes negative, scores indicating worse health-related quality of life. The EQ-5D index was calculated using the European visual analog scale (VAS)-based value set [16]. The MCID for the EQ-5D index is 0.074 [52]. Included in the EQ-5D is also a VAS score in which patients rate their overall health status on a scale of 0 to 100, 100 representing perfect health.

A physiotherapist (ELM, ABS, HEA) blinded to the planned and used approach assessed all patients preoperatively and at subsequent followup, recording the Harris hip score (HHS) [19], measuring the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) [28, 38], and performing the Trendelenburg test [17] directly after the 6MWD. The HHS is an objective measure of hip function in relation to pain, function, and activity as well as ROM. It ranges from 0 to 100 with a higher score indicating better hip function. The MCID is 10 [50]. 6MWD is a reliable measure of walking endurance and is validated for patients undergoing THA [49]. The MCID is 79 m [36]. Trendelenburg testing was performed immediately after the 6MWD. The patients were instructed to stand unsupported on the operated leg and flex the contralateral hip to approximately 45°. The test was deemed negative if the patient, after having found their balance, held their pelvis level, maintained their balance, and kept the lifted leg still and away from the other for at least 5 seconds. If this was not accomplished, the test was deemed positive.

The THAs were performed by five surgeons with experience using both approaches, having used the direct lateral approach for several years and after introducing the direct anterior approach collectively having performed several hundred THAs using that approach [6, 10]. All five surgeons performed a similar number of the two approaches in the study.

All procedures were performed using the same form of anesthesia, local infiltration analgesia, antibiotic prophylaxis, and the same implants, a cemented cup (Marathon®; DePuy, Warsaw, IN, USA), uncemented stem (Corail®; DePuy), and a ceramic head with a diameter of 32 mm (Biolox®forte; Ceramtec, Plochingen, Germany) [27]. Postoperative management was identical for all patients.

The direct anterior approach was performed with the patient in the supine position on a standard operating table. A slightly oblique skin incision measuring approximately 8 cm was used, staring 3 cm distally and laterally to the superoanterior iliac spine. The subcutaneous tissue and the fascia centrally over the tensor fascia lata muscle were divided followed by blunt dissection to open the interval between the tensor facia lata and the sartorius muscle. The lateral circumflex arteries were identified and cauterized. The joint capsule was exposed and the anterior portion removed. A double osteotomy of the femoral neck facilitated removal of the head followed by traditional preparation of the acetabulum using an offset reamer and the cup was cemented in place. Next, the capsule was released distally to reach the lesser trochanter to evaluate the level of the osteotomy compared with the preoperative template followed by release of the superior capsule to elevate the femur to allow access to the femoral canal. The leg was then placed in external rotation, adducted under the contralateral leg, and the hip was extended by lowering the foot end of the table approximately 30°. No traction was used. The femoral canal was opened followed by standard preparation by use of an offset reamer and the stem implanted.

The direct lateral approach was performed with the patient in a lateral decubitus position. A straight skin incision, measuring approximately 14 cm, centered over the greater trochanter was used. The subcutaneous tissue and the fascia lata were divided in line with the skin incision. The anterior third of the gluteus medius along with the gluteus minimus was released from the greater trochanter followed by exposure and removal of the anterior part of the joint capsule. The hip was dislocated, and an osteotomy was performed after releasing the capsule down to the lesser trochanter to decide the level of the osteotomy compared with the preoperative template. The head was removed before traditional preparation of the acetabulum using a straight reamer and cementation of the cup. The leg was then placed in external rotation and adduction before opening of the femoral canal, standard preparation of the femoral canal by a straight reamer, and stem implantation.

Patients were seen at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Complications were recorded, both general medical complications as well as those directly related to the included hip, including prosthetic joint infection, venous thromboembolism, dislocations, and neurovascular injury. Patients who demonstrated persistent severe abductor weakness and severe pain in the trochanteric region underwent MRI. If the MRI showed detachment of the gluteus medius and minimus, the patient was offered surgery with direct suture of the muscle/tendon to the trochanter.

Statistical Analysis

Our primary study outcome was the HHS at 2 years. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. For group comparison for continuous variables, the mean difference with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated and tested using an independent sample t-test and for categorical variables by the chi-square test. The ceiling effect for the HHS and OHS was calculated. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, Version 25 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Power calculation was based on the HHS [19] with a MCID of 10 and SD of 15 yielding a standardized difference of 0.66. To provide 80% power, 70 patients were needed in each group [55]. To account for loss of followup, the decision was made to include at least 80 patients in each group.

Results

Outcome Scores

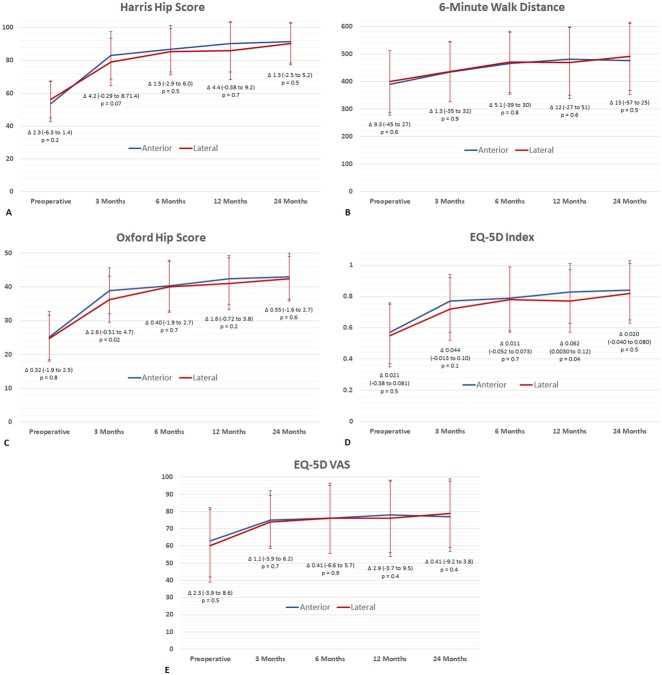

There were few statistical differences and no clinically important differences in terms of validated or patient-reported outcomes scores, including the HHS (Fig. 2A), 6MWD (Fig. 2B), OHS (Fig. 2C), or EQ-5D (Fig. 2 D-E) between the direct anterior and the direct lateral approach at any time point. The statistical differences were the OHS after 3 months with the direct anterior group (mean 39; SD 7) and the direct lateral group (mean 36; SD 7; mean difference 3; 95% CI, 0.5-5) and the EQ-5D index after 12 months. The mean for the direct anterior group was 0.83 (SD 0.18) and for the direct lateral 0.77 (SD 0.20; mean difference 0.062; 95% CI, 0.0030-0.12). Both of these values and results of the other scores fall short of the MCID and are not considered clinically relevant.

Fig. 2 A-E.

(A) HHS comparing the direct anterior and direct lateral approaches. Curves indicate mean ± SD. Δ indicates difference in mean with 95% CI. Score range from 0 to 100 with 100 being the best. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. (B) The 6MWD comparing the direct anterior and direct lateral approaches. Curves indicate mean ± SD. Δ indicates difference in mean with 95% CI. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. (C) OHS comparing the direct anterior and direct lateral approaches. Curves indicate mean ± SD. Δ indicates difference in mean with 95% CI. Score range from 0 to 48 with 48 being the best. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. (D) EQ-5D index comparing the direct anterior and direct lateral approaches. Curves indicate mean ± SD. Δ indicates difference in mean with 95% CI. Index was calculated using the European VAS-based value set with value ranging from -0.074 to 1 with 1 being the best. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. (E) EQ-5D index comparing the direct anterior and direct lateral approaches. Curves indicate mean ± SD. Δ indicates difference in mean with 95% CI. Index range from 0 to 100 with 100 being the best. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

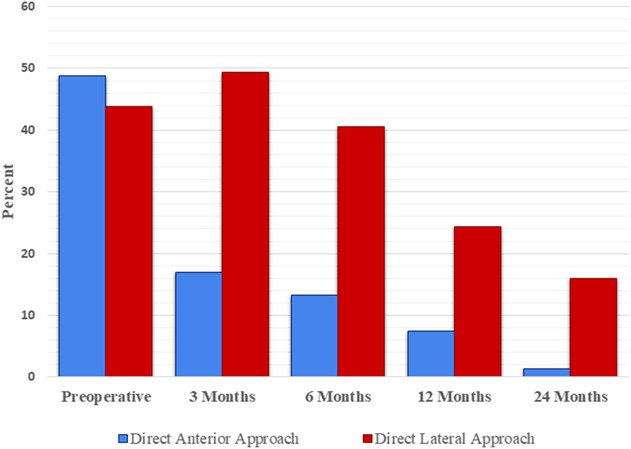

Trendelenburg Test

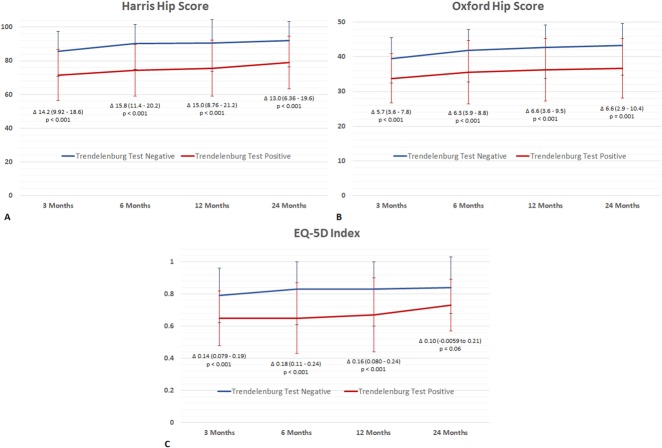

A higher proportion of patients had a positive Trendelenburg test 3 months after surgery in the direct lateral approach group than the direct anterior approach group (49% [39 of 79] versus 17% [14 of 83]; odds ratio, 5 [95% CI, 2-10]; p < 0.001). A higher proportion of the patients in the direct lateral group were Trendelenburg-positive after 6 and 12 months (Fig. 3) and a higher proportion of patients had a persistently positive Trendelenburg test 24 months after surgery in the lateral approach group than the direct anterior approach group (16% [12 of 75] versus 1% [one of 79]; odds ratio, 15; p = 0.001). Irrespective of approach, those with a postitive Trendelenburg test had worse HHS, OHS, and EQ-5D scores than those with a negative Trendelenburg test (Fig. 4 A-C). These differences were both statistical and clinical with the differences above the MCID.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of Trendelenburg-positive patients comparing the direct anterior and direct lateral approaches. Preoperative values were 49% (41 of 84) in the direct anterior group and 44% (35 of 80) in the direct lateral group (odds ratio, 1; 95% CI, 2-10; p = 0.5). Values at 3 months were 17% (14 of 83) in the direct anterior and 49% (39 of 79) in the direct lateral group (odds ratio, 5; 95% CI, 2-10; p < 0.001). At 6 months the values were 13% (11 of 83) in the direct anterior and 41% (32 of 79) in the direct lateral group (odds ratio, 2; 95% CI, 2-10; p < 0.001). At 12 months the values were 7% (six of 81) in the direct anterior and 24% (19 of 79) in the direct lateral group (odds ratio, 4; 95% CI, 2-11; p = 0.003). At 24 months the values were 1% (one of 79) in the direct anterior and 16% (12 of 75) in the direct lateral group (odds ratio, 15; 95% CI, 2-117; p = 0.001). Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Fig. 4 A-C.

(A) HHS comparing Trendelenburg test-negative and -positive patients irrespective of approach. Curves indicate mean ± SD. Δ indicates difference in mean with 95% CI. Score range from 0 to 100 with 100 being the best. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. (B) OHS comparing Trendelenburg test-negative and -positive patients irrespective of approach. Curves indicate mean ± SD. Δ indicates difference in mean with 95% CI. Score range from 0 to 48 with 48 being the best. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. (C) EQ-5D Index comparing Trendelenburg test-negative and -positive patients irrespective of approach. Curves indicate mean ± SD. Δ indicates difference in mean with 95% CI. Index was calculated using the European VAS-based value set with value ranging from -0.074 to 1 with 1 being the best. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Complications

There were five nerve injuries in the direct anterior group (three transient femoral nerve injuries, resolved by 3 months after surgery, one tibial nerve injury with symptoms that persist 24 months after surgery, and one patient with permanent damage to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve) and none in the lateral approach group. All femoral nerve palsies resolved completely before 3 months with all patients reaching HHS > 90. The damage to the posterior tibial nerve resulted in no loss of motor function, but hyperesthesia and pain in the innervated skin area. This lasted throughout the 2-year followup and was considered permanent. Permanent sensory loss in the distribution of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve occurred in one patient.

There was one perioperative complication in the direct anterior group with avulsion of the greater trochanter, which was fixed with a cable wire during primary surgery with no sequelae.

In the direct lateral group, one patient had a superficial infection diagnosed at the time of suture removal. It was treated by antibiotics only and the patient completed followup with the implant intact and no sign of infection. One further patient sustained a deep infection after removal of a painful exostosis of the greater trochanter 9 months after surgery. After unsuccessful eradication of the infection, one-stage revision through the same approach was performed 13 months after the primary surgery. Antibiotics were given for 3 months and the patient completed followup with no further need for surgery and with no signs of infection. Four patients in the direct lateral group had detachment of the released part of the gluteus medius and minimus diagnosed by MRI and clinical examination; they were reoperated on with reinsertion 2, 9, 10, and 11 months after primary THA. Two patients improved after the revision reaching a HHS of 92 at 12 months after surgery and the other 84 after 24 months; the other two unfortunately remained unsuccessful with HHS of 52 and 41 after 24 months.

One patient in the direct anterior group was put on warfarin (Marevan™; Takeda, Tokyo, Japan) for 3 months because of clinically suspected deep venous thrombosis 13 days after the THA, the thrombosis not confirmed by ultrasound or venography. In the direct lateral group, one patient was diagnosed with a pulmonary embolus on pulmonary CT angiography 30 days after the THA and was also treated with warfarin for 3 months.

Discussion

No consensus exists as to which surgical approach is the best for performing THA. The direct lateral approach has been used for many years with good results. The direct anterior approach is gaining popularity with some studies showing less pain postoperatively and quicker rehabilitation, but at the cost of an increased rate of complications. Few prospective, randomized controlled studies comparing the two approaches exist. In this prospective, randomized controlled trial we found no clinical difference in HHS, 6MWD, OHS, or EQ-5D between the direct anterior and the lateral approach at any time point. The level of Trendelenburg test-positive patients differed in favor of the direct anterior approach, and irrespective of approach, those who were Trendelenburg test-positive had clinically worse scores than those with a negative Trendelenburg test.

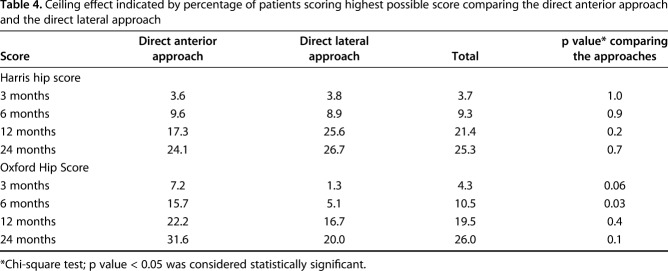

Our study has some potential weaknesses. Blinding the patients to the approach was attempted. The likelihood, however, is that several, if not all, patients figured out which approach their THA was performed through from the scar, which could influence results at followup. The power calculation for our study was based on the HHS and concerns have been raised about the ceiling effect (Table 4) when using the score in clinical trials [53]. The HHS had over the recommended 15% of patients with a top score at 12 and 24 months, but the difference between the approaches was not statistically different and hence should not be biased toward one approach. Lim et al. [26] reported no ceiling effect when using the OHS, but in our study, it was over the recommended 15% for both approaches at 12 and 24 months and for the direct anterior approach at 6 months.

Table 4.

Ceiling effect indicated by percentage of patients scoring highest possible score comparing the direct anterior approach and the direct lateral approach

Our study is not powered to deal [11] with safety endpoints. The incidence of perioperative fractures, nerve injuries, or infections is too low to be able to say anything definite about them with 164 patients in the study. For this, larger cohorts or register studies are needed. Keeping this in mind, however, studies have raised concerns about the level of complications using the direct anterior approach [22, 46]. The surgeons in this study were beyond the learning curve and the number of nerve injuries indicates that caution must be shown not only during the learning curve, but at all times when operating through the direct anterior approach.

We found no clinically important differences at any point between the two approaches on any patient-reported outcome measure. Few comparable studies exist, but some studies indicate early benefits with the direct anterior approach over the direct lateral approach [11, 21, 42, 56], whereas others show no difference [12, 48]. Having compared the two approaches in a randomized trial, measuring several different scores, but having found no clinical difference on group level, we believe that any potential difference is leveled out by 3 months, which was our first postoperative measurement. The choice of approach to use in THA should be based not on functional scores, because the benefit of the direct anterior approach seems short term, but perhaps on the level patients with a limp and/or the level of complication associated with the different approaches.

Although not a specific test for direct damage to the abductor muscles, the use of the Trendelenburg test in postoperative assessment of THA has been recommended [17]. We found clinically meaningful differences at all postoperative time points in favor of the direct anterior approach. All patients in our study performed the 6MWD immediately before the Trendelenburg test to preexhaust the abductors to reveal those with borderline function. Previous studies have reported between 18% and 50% of patients demonstrate a positive Trendelenburg test before THA [23, 39] and up to 28% postoperatively using the direct lateral approach [3, 37], comparable to our results. Regardless of approach, patients with a positive Trendelenburg test had clinically lower scores than those with a negative Trendelenburg test. Amlie et al. [2] compared different approaches in THA, reporting limping as a factor associated with lower patient-reported scores after THA. In concordance with our study, this indicates that care must be taken to avoid abductor weakness, either through choice of approach or careful management of the abductors if using the direct lateral approach.

We found a high incidence of nerve injuries in our direct anterior group. Damage to the peroneal nerve in THA is stated to be 0.07%, but the cause of damage is not established [29]. Other studies have indicated a risk of damage to the femoral nerve between 0.1% and 0.26% [25, 29]. The reasons for this are unclear. One reason could be that these injuries might not be reported given that patients regained full function before 3 months. Our patients were followed closely by physiotherapists during admission and were admitted for 4 days as a result of registration of serum enzymes and pain. This could perhaps reveal cases with borderline femoral nerve function that otherwise would go unnoticed, given that if not recorded during admission, it would go unnoticed. The local infiltration anesthesia could potentially be a factor, although we have no data to substantiate this speculation.

In the direct lateral group, four patients underwent surgery as a result of detachment of the gluteus medius and minimus. Abductor deficiency after THA is reported to be up to 22% [30], an indication that detachment of the anterior portion of the medius and minimus might often be overlooked. Svensson et al. [47] have reported that there is a separation of the reinserted portion of the muscle in 50% of THAs using the direct lateral approach, but that separation to a certain degree can be compensated for. As reported by Odak and Ivory [37], there is no consensus regarding the indication for reoperation as a result of gluteal insufficiency, making it difficult to know when to offer patients a reoperation. Before reoperation, all four of our patients had both poor clinical abductor function as well as an MRI indicating detachment of the muscle, which should provide a good indication for surgical repair, but in light of the fact that only two of the four improved, reoperation might not have been warranted. The result after reattachment surgery was comparable to results reported by other authors [37] and illustrates the difficulty in dealing with abductor deficiency after use of the direct lateral approach.

In conclusion, based on our findings, no case for superiority of one approach over the other can be made, except for the reduction in postoperative Trendelenburg test-positive patients using the direct anterior approach compared with when using the direct lateral approach. Irrespective of approach, patients with a positive Trendelenburg test had clinically worse scores than those with a negative test, indicating the importance of ensuring good abductor function when performing THA. The direct anterior approach was associated with nerve injuries that were not seen in the group treated with the lateral approach.

Acknowledgments

We thank physiotherapists Ann Brit Sangvik, Elisabeth Lilleholt Müller, and Hanne Elisabeth Austnes for their great contribution in assessing all patients and Dr Paal Arnesen and Dr Terje Fallaas for performing THAs in the study.

Footnotes

One of the authors (KEM) reports personal fees from Ortomedic (Lysaker, Norway) outside the submitted work. One of the authors (LN) reports personal fees from Ortomedic and personal fees from Eli Lilly (Lysaker, Norway) outside the submitted work.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Sorlandet Hospital, Arendal, Norway.

References

- 1.Alecci V, Valente M, Crucil M, Minerva M, Pellegrino CM, Sabbadini DD. Comparison of primary total hip replacements performed with a direct anterior approach versus the standard lateral approach: perioperative findings. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12:123–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amlie E, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Baste V, Nordsletten L, Hovik O, Dimmen S. Worse patient-reported outcome after lateral approach than after anterior and posterolateral approach in primary hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2014;85:463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker AS, Bitounis VC. Abductor function after total hip replacement. An electromyographic and clinical review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beard DJ, Harris K, Dawson J, Doll H, Murray DW, Carr AJ, Price AJ. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berstock JR, Blom AW, Whitehouse MR. A comparison of the omega and posterior approaches on patient reported function and radiological outcomes following total hip replacement. J Orthop. 2017;14:390–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brun OL, Mansson L, Nordsletten L. The direct anterior minimal invasive approach in total hip replacement: a prospective departmental study on the learning curve. Hip Int. 2018;28:156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caton J, Prudhon JL. Over 25 years survival after Charnley's total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2011;35:185–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charnley J, Halley DK. Rate of wear in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;112:170–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A, Murray D. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Steiger RN, Lorimer M, Solomon M. What is the learning curve for the anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3860–3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Hartog YM, Mathijssen NM, Vehmeijer SB. The less invasive anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: a comparison to other approaches and an evaluation of the learning curve–a systematic review. Hip Int. 2016;26:105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engdal M, Foss OA, Taraldsen K, Husby VS, Winther SB. Daily physical activity in total hip arthroplasty patients undergoing different surgical approaches: a cohort study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;96:473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eto S, Hwang K, Huddleston JI, Amanatullah DF, Maloney WJ, Goodman SB. The direct anterior approach is associated with early revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;32:1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.EuroQol G. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goebel S, Steinert AF, Schillinger J, Eulert J, Broscheit J, Rudert M, Noth U. Reduced postoperative pain in total hip arthroplasty after minimal-invasive anterior approach. Int Orthop. 2012;36:491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greiner W, Weijnen T, Nieuwenhuizen M, Oppe S, Badia X, Busschbach J, Buxton M, Dolan P, Kind P, Krabbe P, Ohinmaa A, Parkin D, Roset M, Sintonen H, Tsuchiya A, de Charro F. A single European currency for EQ-5D health states. Results from a six-country study. Eur J Health Econ. 2003;4:222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardcastle P, Nade S. The significance of the Trendelenburg test. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64:17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iorio R, Healy WL, Warren PD, Appleby D. Lateral trochanteric pain following primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jelsma J, Pijnenburg R, Boons HW, Eggen PJ, Kleijn LL, Lacroix H, Noten HJ. Limited benefits of the direct anterior approach in primary hip arthroplasty: a prospective single centre cohort study. J Orthop. 2017;14:53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jewett BA, Collis DK. High complication rate with anterior total hip arthroplasties on a fracture table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:503–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landgraeber S, Quitmann H, Guth S, Haversath M, Kowalczyk W, Kecskemethy A, Heep H, Jager M. A prospective randomized peri- and post-operative comparison of the minimally invasive anterolateral approach versus the lateral approach. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2013;5:e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet. 2007;370:1508–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee GC, Marconi D. Complications following direct anterior hip procedures: costs to both patients and surgeons. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim CR, Harris K, Dawson J, Beard DJ, Fitzpatrick R, Price AJ. Floor and ceiling effects in the OHS: an analysis of the NHS PROMs data set. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindalen E, Havelin LI, Nordsletten L, Dybvik E, Fenstad AM, Hallan G, Furnes O, Hovik O, Rohrl SM. Is reverse hybrid hip replacement the solution? Acta Orthop. 2011;82:639–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lord SR, Menz HB. Physiologic, psychologic, and health predictors of 6-minute walk performance in older people. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:907–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macheras GA, Christofilopoulos P, Lepetsos P, Leonidou AO, Anastasopoulos PP, Galanakos SP. Nerve injuries in total hip arthroplasty with a mini invasive anterior approach. Hip Int. 2016;26:338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masonis JL, Bourne RB. Surgical approach, abductor function, and total hip arthroplasty dislocation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;405:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meneghini RM, Elston AS, Chen AF, Kheir MM, Fehring TK, Springer BD. Direct anterior approach: risk factor for early femoral failure of cementless total hip arthroplasty: a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirza AJ, Lombardi AV, Jr, Morris MJ, Berend KR. A mini-anterior approach to the hip for total joint replacement: optimising results: improving hip joint replacement outcomes. Bone Joint J. 2014;96:32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mjaaland KE, Kivle K, Svenningsen S, Pripp AH, Nordsletten L. Comparison of markers for muscle damage, inflammation, and pain using minimally invasive direct anterior versus direct lateral approach in total hip arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Orthop Res. 2015;33:1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mjaaland KE, Svenningsen S, Fenstad AM, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Nordsletten L. Implant survival after minimally invasive anterior or anterolateral vs conventional posterior or direct lateral approach: an analysis of 21,860 total hip arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (2008 to 2013). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:840–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, Pandit H, Beard DJ, Carr AJ, Dawson J. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naylor JM, Hayen A, Davidson E, Hackett D, Harris IA, Kamalasena G, Mittal R. Minimal detectable change for mobility and patient-reported tools in people with osteoarthritis awaiting arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odak S, Ivory J. Management of abductor mechanism deficiency following total hip replacement. Bone Joint J. 2013;95:343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Overgaard JA, Larsen CM, Holtze S, Ockholm K, Kristensen MT. Interrater reliability of the 6-minute walk test in women with hip fracture. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2016;40:158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Picado CH, Garcia FL, Marques W., Jr Damage to the superior gluteal nerve after direct lateral approach to the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pogliacomi F, De Filippo M, Paraskevopoulos A, Alesci M, Marenghi P, Ceccarelli F. Mini-incision direct lateral approach versus anterior mini-invasive approach in total hip replacement: results 1 year after surgery. Acta Biomed. 2012;83:114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reichert JC, Volkmann MR, Koppmair M, Rackwitz L, Ludemann M, Rudert M, Noth U. Comparative retrospective study of the direct anterior and transgluteal approaches for primary total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2309–2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Restrepo C, Parvizi J, Pour AE, Hozack WJ. Prospective randomized study of two surgical approaches for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:671–679 e671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet. 2002;359:614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheth D, Cafri G, Inacio MC, Paxton EW, Namba RS. Anterior and anterolateral approaches for THA are associated with lower dislocation risk without higher revision risk. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3401–3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith-Petersen MN. Approach to and exposure of the hip joint for mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1949;31:40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spaans AJ, van den Hout JA, Bolder SB. High complication rate in the early experience of minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty by the direct anterior approach. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:342–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Svensson O, Skold S, Blomgren G. Integrity of the gluteus medius after the transgluteal approach in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5:57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trevisan C, Compagnoni R, Klumpp R. Comparison of clinical results and patient's satisfaction between direct anterior approach and Hardinge approach in primary total hip arthroplasty in a community hospital. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101:261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unver B, Kahraman T, Kalkan S, Yuksel E, Karatosun V. Reliability of the six-minute walk test after total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int. 2013;23:541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Wees PJ, Wammes JJ, Akkermans RP, Koetsenruijter J, Westert GP, van Kampen A, Hannink G, de Waal-Malefijt M, Schreurs BW. Patient-reported health outcomes after total hip and knee surgery in a Dutch University Hospital Setting: results of twenty years clinical registry. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varin D, Lamontagne M, Beaule PE. Does the anterior approach for THA provide closer-to-normal lower-limb motion? J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1401–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1523–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wamper KE, Sierevelt IN, Poolman RW, Bhandari M, Haverkamp D. The Harris hip score: do ceiling effects limit its usefulness in orthopedics? Acta Orthop. 2010;81:703–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wayne N, Stoewe R. Primary total hip arthroplasty: a comparison of the lateral Hardinge approach to an anterior mini-invasive approach. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2009;1:e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitley E, Ball J. Statistics review 4: sample size calculations. Crit Care. 2002;6:335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yue C, Kang P, Pei F. Comparison of direct anterior and lateral approaches in total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA). Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zijlstra WP, De Hartog B, Van Steenbergen LN, Scheurs BW, Nelissen R. Effect of femoral head size and surgical approach on risk of revision for dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2017:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]