Abstract

Background

Implant selection in the operating room is a manual process. This manual process combined with complex compatibility rules and inconsistent implant labeling may lead to implant-selection errors. These might be reduced using an automated process; however, little is known about the efficacy of available automated error-reduction systems in the operating room.

Questions/purposes

(1) How often do implant-selection errors occur at a high-volume institution? (2) What types of implant-selection errors are most common?

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated our implant log database of 22,847 primary THAs and TKAs to identify selection errors. There were 10,689 THAs and 12,167 TKAs included during the study period from 2012 to 2017; there were no exclusions and we had no missing data in this study. The system provided an output of errors identified, and these errors were then manually confirmed by reviewing implant logs for each case found in the medical records. Only those errors that were identified by the system were manually confirmed. During this time period all errors for all procedures were captured and presented as a proportion. Errors identified by the software were manually confirmed. We then categorized each mismatch to further delineate the nature of these events.

Results

One hundred sixty-nine errors were identified by the software system just before implantation, representing 0.74 of the 22,847 procedures performed. In 15 procedures, the wrong side was selected. Twenty-five procedures had a femoral head selected that did not match the acetabular liner. In one procedure, the femoral head taper differed from the femoral stem taper. There were 46 procedures in which there was a size mismatch between the acetabular shell and the liner. The most common error in TKA that occurred in 46 procedures was a mismatch between the tibia polyethylene insert and the tibial tray. There were 13 procedures in which the tibial insert was not matched to the femoral component according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Selection errors were identified before implantation in all procedures.

Conclusions

Despite an automated verification process, 0.74% of the arthroplasties performed had an implant-selection error that was identified by the software verification. The prevalence of incorrect/mismatched hip and knee prostheses is unknown but almost certainly underreported. Future studies should investigate the prevalence of these errors in a multicenter evaluation with varying volumes across the involved sites. Based on our results, institutions and management should consider an automated verification process rather than a manual process to help decrease implant-selection errors in the operating room.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study.

Introduction

As the number of total joint arthroplasties continues to increase worldwide, implant-related patient safety protocols are a major concern. Implants used in arthroplasty are regulated by institutions or governmental agencies; however, the final selection in the operating room is a manual process. When this manual process is combined with complex compatibility rules and inconsistent labeling, implantation errors are inevitable. An American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons survey in 2009 found that 2.6% of surgeons observed an implant-related error in the past 6 months at the time of the survey [16]. Whittaker et al. [15] found that 0.9% of failed metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties in their retrieval center had component mismatch and they felt that component mismatch is underrepresented in national joint registries [15]. In New Zealand, 23% of surgeons said that they had implanted a mismatched component in the past 5 years [14]. Implanting mismatched implants can lead to poor clinical function and early failure of the arthroplasty. Several studies have reported the devastating effects of mismatch, which can put the patient at greater risk for ceramic head fracture that must be avoided [2, 3, 5-7, 10, 11, 15]. In addition, newer implant systems are often more complex than their predecessors. Understanding implant-selection errors should be studied to help implement a thoughtful methodology to prevent future selection errors. Currently, the selection and recording of medical devices is a costly, inefficient, and error-prone manual process. As surgical volumes and implant complexity increase, these manual processes become strained and are likely to break down, resulting in avoidable implant complications, unnecessary wastage, and documentation errors. We have previously demonstrated that this type of system is effective in decreasing implant-related medical errors and implant wastage in a small cohort of patients at our institution; however, our current study looks at a large number of patients over multiple years to further understand the incidence of selection errors [1].

Our study aims to answer the following questions: (1) How often do implant-selection errors occur at a high-volume institution? (2) What types of implant-selection errors are most common?

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed data collected at a single institution that uses a software verification system (OpLogix, Edison, NJ, USA) with a standardized, stepwise protocol in the operating room standard practice to identify selection errors that occurred in the operating room. We retrospectively studied our database of all THAs and TKAs performed since the introduction of this computer software verification from 2012 to 2017. There were 10,680 THAs and 12,167 TKAs performed since the implementation of the software verification system; there were no exclusions and we had no missing data in this study. This system was developed by Sandance Technology (Sandance Technology, LLC, Princeton, NJ, USA) and we have previously reported its use and validation [1]. The system was designed to use the barcodes on implant boxes to create a single, easy-to-read, digital label that can be displayed on a video monitor. The system includes implant compatibility rules for all major hip and knee replacement implants in the United States, and it considers these rules in determining whether an implant-selection error has been made. Preclinical and secondary clinical validation was performed before its clinical implementation in 2012.

The system extracts basic demographics and laterality from surgical consent forms, which at our hospital are barcoded and scanned into the system by the circulating nurse during the presurgical time-out. This provides basic patient demographics as well as laterality. The software verification system requires a barcode to be scanned before opening any sterile implant box. Before implantation, the circulating nurse scans the implants into the software system and asks the surgeon to confirm the implant on the screen after it is scanned. The software internal verification uses the implant box barcodes and records all implants scanned during surgery. The system records which implants are used and which implants are not used at the time of surgery. As each implant is scanned, the system checks component compatibility based on embedded manufacturer guidelines. After final implantation, any wasted parts are scanned and the reason for waste is recorded. These implant records are then saved into the computer system database, which can then be accessed to retrieve implant data for research purposes. There were no demographic or patient data reviewed because this was a study looking at implant data only.

We used the system to identify any implant boxes that were scanned and not opened because these represent instances in which the system identified an impending implant-related selection error. These selection-error events were then further categorized manually by an individual based on review of implant records to classify selection errors resulting from laterality mismatches, size mismatches, and component mismatches to further delineate the nature of these events. Descriptive statistics were used to report the occurrence of selection errors in all patients during the study period. All THAs and TKAs during this time period were included for analysis.

Results

In 0.74% of the total procedures performed, we identified 169 selection errors with the software system just before implantation (169 of 22,847). In 15 THAs (0.14% of the 10,680 THAs), the wrong side was selected despite multiple manual safeguards and verifications as we have described them. Twenty-five procedures (0.23% of 10,680 THAs) had a femoral head selected that did not match the acetabular liner (for example, a 32-mm head in a liner designed for 36-mm heads). In one procedure, the femoral head taper differed from the femoral stem taper. There were 46 procedures (0.43% of 10,680 THAs) in which there was a size mismatch between the acetabular shell and the liner.

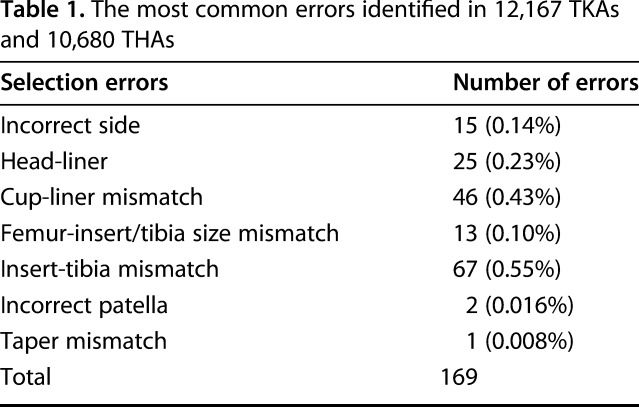

The most common error in TKA that occurred in 46 procedures (0.38% of 12,167 TKAs) was a mismatch between the tibia polyethylene insert and the tibial tray. In addition, there were 13 procedures (0.10% of the 12,167 TKAs) in which the tibial insert was not matched to the femoral component according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Table 1). Selection errors were identified before implantation in all procedures.

Table 1.

The most common errors identified in 12,167 TKAs and 10,680 THAs

Discussion

Recent emphasis on rising healthcare costs has led to a focus on reduction of waste and ways to implement cost-effective safeguards throughout hospitals nationwide. Implant waste has been noted to be a cost contributor for orthopaedic procedures [12]. Various protocols and guidelines have been reported to decrease the cost of orthopaedic procedures, but implant waste is still a large contributor to the overall cost of orthopaedic procedures. One study found implant waste occurred in 79 of 3443 procedures (2%), that operating room staff and surgeons were responsible for 73% of the occurrences, and that most of these costs were absorbed by the hospital [17]. Although highlighting the financial burden on implant waste has been shown to decrease it, there is need for a thoughtful and validated approach or an automated computer system to help decrease errors caused by manual procedures to prevent these errors worldwide [13]. We previously found that the implementation of error-detection software decreased the number and cost associated with wasted implants [1]. In this study, we found that the software verification system was also able to prevent numerous selection errors, which would prevent possible clinical adverse events. We found that despite a number of safety-related processes in place apart from the software, nearly 1% of arthroplasties might have had an implant-related error if not caught by the error-detection program. The most common of these was bearing-surface mismatch during TKA.

This study had several limitations. First, the computer software system only identifies selection errors. These obviously do not account for all errors that can occur during surgery and proper surgical technique and implant planning before and during surgery remain paramount to a successful arthroplasty. However, selection errors are another possible source of error and this study looked to evaluate that specifically. Second, our study examines selection errors, but other intraoperative errors may occur that may cause even greater harm; however, we did not review medical records to address these. Third, these data were retrospectively evaluated, so a weakness of our study is the lack of an error analysis that can identify how mistakes may have happened in the operating room. Future studies should record how each error happened and provide an error analysis.

Identifying potential systematic problems before they cause actual patient harm should be the goal of all physicians. The identification of selection errors is an important part of any quality improvement program. Selection errors represent a potential “near-miss” event. Although to our knowledge this has not previously been done in arthroplasty, other areas of medicine have shown the importance of identifying these potentially important events. Despite a multilayered verification process, 169 (0.74%) procedures we studied had an implant-selection error that was only identified by the software verification system. Callum et al. [4] examined near-miss events during blood transfusions. They noted the importance of near misses not only in the prevention of serious medical errors, but also for monitoring changes after corrective actions are put in place. The United Kingdom also has a system for the evaluation and prevention of near misses in obstetric cases known as the UK Obstetric Surveillance System [8]. There is also a European Commission-based set of guidelines to avoid medical errors and near misses in external beam radiation therapy [9]. Programs like these allow for blameless identification of near-miss events that can be used to improve safety systems and may lead to safer surgery for our patients.

We have identified that selection error is common enough to deserve attention, and use of a software program provides one way to avoid some of these selection errors. Further research is needed to determine the frequency of implantation errors in the context of a multicenter trial in which the participating centers vary by surgical volume and to assess whether larger implementation of this program could be used to decrease selection errors. In addition, future prospective studies should assess how the errors occurred so steps can be taken to prevent them.

Footnotes

One author (SBH) is an officer and software developer for OpLogix (Edison, NJ, USA) and has stock options with the company.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Ast MP, Mayman DJ, Su EP, Gonzalez Della Valle AM, Parks ML, Haas SB. The reduction of implant-related errors and waste in total knee arthroplasty using a novel, computer based, e.Label and compatibility system. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boese CK, Dargel J, Jostmeier J, Eysel P, Frink M, Lechler P. Agreement between proximal femoral geometry and component design in total hip arthroplasty: implications for implant choice. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1842–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calistri A, Campbell P, Van Der Straeten C, De Smet KA. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty complicated by mismatched implant components. World J Orthop . 2017;8:286–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callum JL, Kaplan HS, Merkley LL, Pinkerton PH, Rabin Fastman B, Romans RA, Coovadia AS, Reis MD. Reporting of near-miss events for transfusion medicine: improving transfusion safety. Transfusion (Paris). 2001;41:1204–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Haan R, Campbell PA, Su EP, De Smet KA. Revision of metal-on-metal resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: the influence of malpositioning of the components. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 2008;90:1158–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanks GA, Foster WC, Cardea JA. Total hip arthroplasty complicated by mismatched implant sizes. Report of two cases. J Arthroplasty. 1986;1:279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hohman DW, Affonso J, Anders M. Ceramic-on-ceramic failure secondary to head-neck taper mismatch. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2011;40:571–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight M, Lewis G, Acosta CD, Kurinczuk JJ. Maternal near-miss case reviews: the UK approach. BJOG . 2014;121(Suppl 4):112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malicki J, Bly R, Bulot M, Godet J-L, Jahnen A, Krengli M, Maingon P, Martin CP, Przybylska K, Skrobała A, Valero M, Jarvinen H. Patient safety in external beam radiotherapy--guidelines on risk assessment and analysis of adverse error-events and near misses: introducing the ACCIRAD project. Radiother Oncol . 2014;112:194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McWilliams AB, Douglas SL, Redmond AC, Grainger AJ, O’Connor PJ, Stewart TD, Stone MH. Litigation after hip and knee replacement in the National Health Service. Bone Joint J . 2013;95:122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morlock M, Nassutt R, Janssen R, Willmann G, Honl M. Mismatched wear couple zirconium oxide and aluminum oxide in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:1071–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne A, Slover J, Inneh I, Hutzler L, Iorio R, Bosco JA. Orthopedic implant waste: analysis and quantification. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44:554–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfefferle KJ, Shemory ST, Dilisio MF, Fening SD, Gradisar IM. Risk factors for manipulation after total knee arthroplasty: a pooled electronic health record database study. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:2036–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stokes A, Rutherford A. Mismatch of modular prosthetic components in total joint arthroplasty: the New Zealand experience. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 2005;87:32.15686234 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittaker RK, Hexter A, Hothi HS, Panagiotidou A, Bills PJ, Skinner JA, Hart AJ. Component size mismatch of metal on metal hip arthroplasty: an avoidable never event. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1629–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong DA, Herndon JH, Canale ST, Brooks RL, Hunt TR, Epps HR, Fountain SS, Albanese SA, Johanson NA. Medical errors in orthopaedics. Results of an AAOS member survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2009;91:547–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zywiel MG, Ulrich SD, Suda AJ, Duncan JL, McGrath MS, Mont MA. Incidence and cost of intraoperative waste of hip and knee arthroplasty implants. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:558–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]