Abstract

Susceptibility to social influence is associated with a host of negative outcomes during adolescence. However, emerging evidence implicates the role of peers and parents in adolescents’ positive and adaptive adjustment. Hence, in this chapter we highlight social influence as an opportunity for promoting social adjustment, which can redirect negative trajectories and help adolescents thrive. We discuss influential models about the processes underlying social influence, with a particular emphasis on internalizing social norms, embedded in social learning and social identity theory. We link this behavioral work to developmental social neuroscience research, rooted in neurobiological models of decision-making and social cognition. Work from this perspective suggests that the adolescent brain is highly malleable and particularly oriented towards the social world, which may account for heightened susceptibility to social influences during this developmental period. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been used to investigate the neural processes underlying social influence from peers and family as they relate to positive, adaptive outcomes in adolescence. Regions of the brain involved in social cognition, cognitive control, and reward processing are implicated in social influence. This chapter underscores the need to leverage social influences during adolescence, even beyond the family and peer context, to promote positive developmental outcomes. By further probing the underlying neural mechanisms as an additional layer to examining social influence on positive youth development, we will be able to gain traction on our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Keywords: adolescence, social influence, positive adjustment, brain development, fMRI, peers, family

I. A developmental social neuroscience perspective on social influence

If your friends jumped off a cliff, would you too? Everyone has heard this phrase at some point in their lives, either in the position of a worried parent or not-so-worried teenager. Indeed, a vast literature indicates that health-compromising risky behaviors increase when adolescents are with their peers (reviewed in Van Hoorn, Fuligni, Crone, & Galván, 2016). Emerging evidence from developmental neuroscience suggests that the adolescent brain is highly plastic and undergoes a major “social reorientation” (Nelson, Leibenluft, McClure, & Pine, 2005), which may render adolescents particularly susceptible to social influences. While the focus of most research, popular media, and parental worries has been directed towards seeing social influence susceptibility as negative, leading teens to engage in dangerous behaviors, recent attention has sought to understand how adolescents’ heightened social influence susceptibility may be redirected towards positive, adaptive behaviors.

In this chapter, we review emerging evidence highlighting how social influences from both peers and family can play a positive role in adolescents’ adjustment. We first define social influence, focusing on two influential theories, social learning theory and social identity theory, both of which discuss social influence in terms of internalizing group norms. We then review literature highlighting several sources of social influence, including dyadic friendships, cliques, social networks, parents, siblings, and the larger family unit. Given the important neural changes occurring in adolescence, we describe the important role of maturational changes in the developing brain that may underlie susceptibility to social influence. We discuss prominent models of adolescent brain development and then review emerging research highlighting how family and peer influence are represented at the neural level. Finally, we conclude with future directions underscoring the need to capitalize on social influences from peers and parents during adolescence, examine different sources of social influence in the context of the larger social network, and expand our knowledge on the neural mechanisms underlying social influence.

II. Defining Social Influence

What is social influence? At the most basic level, social influence “comprises the processes whereby people directly or indirectly influence the thoughts, feelings, and actions of others” (Turner, 1991, pg. 1). When most people think of social influence, images of peers cheering on their friends to drink, do drugs, or engage in risky and reckless behavior likely come to mind. Popular misconceptions about social influence that saturate the media and parents’ worries too often focus on these very explicit, overt, and negative examples. But what many do not realize is that social influence is much more subtle and complex, and cannot often be identified so easily. In fact, direct peer pressure is not associated with adolescents’ smoking intentions, whereas the perceived behaviors of peers are (Vitoria, et al., 2009). Moreover, social influence has many positive implications, for instance, exposing youth to positive social norms such as school engagement, cooperating with peers, donating money, and volunteering for a good cause. In this section, we will review prominent theories of social influence with a particular emphasis on the internalization of social norms, embedded in social learning and social identity theory.

A. Social Norms

A social norm is “a generally accepted way of thinking, feeling, or behaving that is endorsed and expected because it is perceived as the right and proper thing to do. It is a rule, value or standard shared by the members of a social group that prescribes appropriate, expected or desirable attitudes and conduct in matters relevant to the group” (Turner, 1991, pg. 3). Group norms are further defined as “regularities in attitudes and behavior that characterize a social group and differentiate it from other social groups” (Hogg & Reid, 2006, pg. 7). Norms are therefore shared thoughts, attitudes, and values, governing appropriate behavior by describing what one ought to do, and in essence prescribe moral obligations (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). Social norms are communicated by what people do and say in their everyday lives, which can be indirect (e.g., inferring norms from others’ behaviors) but also direct (e.g., intentionally talking about what is and is not normative of the group; Hogg & Reid, 2006). Deviation from the social norms of a group can result in loss of social status or exclusion, particularly if the social norm is important to the group (Festinger, 1950). Thus, norms serve to reinforce conformity by promoting the need for social acceptance and avoidance of social punishments (e.g., Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

Social norms have a profound impact on influencing attitudes and behaviors, even though people are typically unaware of how influential social norms are (Nolan et al., 2008). In fact, people are strongly influenced by social norms even when they explicitly reject such norms (McDonald, Fielding, & Louis, 2013). In a classic study, Prentice and Miller (1993) asked Princeton undergraduates how comfortable they versus the average Princeton undergraduates are with drinking. Results across several studies converged on the same conclusion – individuals believe others are more comfortable with drinking than themselves. This phenomenon is referred to as pluralistic ignorance (e.g., Prentice & Miller, 1996), which occurs when people personally reject a group norm, yet they incorrectly believe that everyone else in the group engages in the behavior. This introduces a “perceptual paradox” – in reality the behavior is not the norm since nobody engages in it, yet it is the group norm because everyone thinks everyone else does engage in the behavior (Hogg & Reid, 2006). Adolescents also misjudge the behaviors of their peers and close friends. Referred to as the false consensus effect, adolescents misperceive their peers’ attitudes and behaviors to be more similar to their own or even overestimate their peers’ engagement in health-risk behaviors (Prinstein & Wang, 2005). Thus, adolescents overestimate the prevalence of their peers’ behaviors and use their (mis)perceptions of social norms as a standard by which to compare their own behavior.

B. Social Learning Theory

Social learning theory provides the basis for how social norms are learned and internalized during adolescence. Although this theory was originally developed to describe criminality and deviant behavior, its propositions can also be applied to positive social learning. Akers (1979, 2001, 2011) identified four core constructs of social learning: differential association, differential reinforcement, imitation or modeling, and definitions. Differential association refers to the direct association with groups who express certain norms, values, and attitudes. The groups with whom one is associated provides the social context in which all social learning occurs. The most important groups include family and friends, but can also include more secondary sources such as the media (Akers & Jensen, 2006). According to Sutherland’s differential association theory (Sutherland, Cressey, & Luckenbill, 1992), learning takes place according to the frequency, duration, priority, and intensity of adolescents’ social interactions. Adolescents will learn from and internalize social norms if (1) associations occur earlier in development (priority), (2) they associate frequently with others who engage in the behavior (frequency), (3) interactions occur over a long period of time (duration), and (4) interactions involve individuals with whom one is close (e.g., friends and family) as opposed to more casual or superficial interactions (intensity). The more one’s patterns of differential association are balanced towards exposure to prosocial, positive behavior and attitudes, the greater the probability that one will also engage in positive behaviors. Association with groups provides the social context in which exposure to differential reinforcement, imitation of models, and definitions for behaviors take place (Akers, 1979).

Differential reinforcement refers to the balance of past, present, and anticipated future rewards and punishments for a given behavior (Akers & Jensen, 2006), and includes the reactions and sanctions of all important social groups, especially those of peers and family, but can also include other groups such as schools and churches (Akers, 1979; Krohn et al., 1985). In particular, behaviors are strengthened through rewards (i.e., positive reinforcement; e.g., peer acceptance of behaviors) and avoidance of punishments (i.e., negative reinforcement; e.g., peer rejection of behaviors) or weakened though receiving punishments (i.e., positive punishment; e.g., being grounded by parents) and loss of rewards (i.e., negative punishment; e.g., having the family car taken away; Akers, 1979). Behaviors that are reinforced, either through social rewards or the avoidance of social punishments, are more likely to be repeated, whereas behaviors that elicit social punishments are less likely to be repeated (Akers, 2001). Thus, through differential reinforcement, individuals are conditioned to internalize the social norms that are valued by the group.

Social behavior is also shaped by imitating or modeling others’ behavior. Individuals learn behaviors by observing those around them (Bandura, 1977, 1986), particularly close others such as parents, siblings, or friends. The magnitude of social learning, and imitation in particular, is strengthened the more similar the individuals are (Bandura, 1986, 2001). Social influence has an effect on youth when adolescents are exposed to the behaviors and norms of others (i.e., mere exposure) and observe the positive outcomes others receive from such behaviors (i.e., vicarious learning). Adolescents then internalize such social norms and model the behaviors in future instances.

Finally, definitions are the attitudes, rationalizations, or meanings that one attaches to a given behavior that define the behavior as good or bad, right or wrong, justified or unjustified, appropriate or inappropriate (Akers & Jensen, 2006). The more individuals have learned that specific attitudes or behaviors are good or desirable (positive definition) or as justified (neutralizing definition) rather than as undesirable (negative definition), the more likely they are to engage in the behavior (Akers, 1979). These definitions are learned through imitation and subsequent differential reinforcement by members of their peer and family groups. Although there may be norm conflict in terms of the definitions promoted by one’s peers (e.g., positive definition for alcohol) and parents (e.g., negative definition for alcohol), the relative weight of such definitions will determine whether an adolescent endorses the social norm and engages in the behavior. An individual will engage in the behavior when the positive and neutralizing definitions of the behavior offset the negative definitions (Akers, 1979).

C. Social Identity Theory

Group identification is essential for understanding the effects of social norms (Turner, 1991). According to social identity theory, social influence occurs when individuals internalize contextually salient group norms, which set the stage for their self-definition, attitudes, and behavioral regulation (Tajfel, 1981; Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Hogg & Reid, 2006). From a social identity perspective, norms reflect a shared group prototype, which are individuals’ cognitive representations of group norms (Hogg & Reid, 2006). Group prototypes describe normative behaviors and prescribe behavior, indicating how one ought to behave as a group member. Thus, strong group identification can lead to social influence and conformity because individuals endorse the behaviors they should engage in based on the social norms prescribed by group prototypes (Terry & Hogg, 1996).

The family is the first and primary social group to which most individuals belong (Bahr et al., 2005), whereas friends become an increasingly salient social identity during adolescence, a developmental period marked by a need to belong and affiliate with peers (Crockett et al., 1984; Newman & Newman, 2001; Kroger, 2000; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Hart & Fegley, 1995). Importantly, the social environment can activate certain identities and determine whether an individual will be influenced (Oakes, 1987). Across development (e.g., from childhood to adolescence) and across contexts (e.g., at school versus at home), different social identities (e.g., family versus peers) will be more or less salient, affecting whether group norms are strongly internalized and activated.

Adolescents are not only influenced by a single salient group but also by the norms of multiple groups (McDonald et al., 2013), including family, close friends, out-group peers, and the broader societal norms. When more than one social identity is activated, norm-conflict may occur, especially if there are inconsistencies across group norms (McDonald et al., 2013). A particularly prominent example of this likely occurs in adolescents’ daily lives when the norms and valued behaviors of the peer group (e.g., drinking alcohol is fun) conflict with the norms internalized at home (e.g., drinking alcohol is unacceptable behavior). Although seemingly bad, norm conflict can potentially increase motivation to engage in a behavior, because the norm conflict reinforces the need to personally act (McDonald et al., 2013). As an example, if a teen sees a peer being bullied at school, and her close friends are cheering on the bully to continue picking on the teen, but another group of her peers is expressing concern for the teen, an adolescent may be moved to act and stick up for the victim due to this conflict, because she sees the need to personally act. Thus, when multiple group identities are activated and norm-conflict occurs, teens may be motivated to engage in a positive behavior (McDonald et al., 2013).

III. Social influence on positive youth development

Social learning and social identity theories highlight that a myriad of social influences affect positive adjustment during adolescence. Sources of social influence include peers, family, teachers, other attachment figures (e.g., coach of sports team, youth group leader) and even (social) media (Akers 1979; Bandura, 2001; McDonald et al., 2013). In this chapter, we specifically focus on social influences from peers and family and their interactions, given the saliency of developmental changes in these social relationships during adolescence (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Although peers are often referred to as a unified construct (i.e., persons of the same age, status, or ability as another specified person) previous research has assessed a wide range of peers that fall under this umbrella. Hence, we make a distinction between best friend dyads, smaller peer groups such as cliques, and larger peer groups of unknown others. Family influences similarly encompass multiple layers, and here we review influences from parents, siblings and their interactions within the larger family unit. Finally, we will discuss literature that examines these social influences simultaneously.

A. Peer influence on positive adolescent development

Peer influence has predominantly negative connotations and received most attention in the context of problem behaviors during adolescence. Indeed, extant research has shown that hanging out with the wrong crowd may increase deviant behaviors through processes of social reinforcement or “peer contagion” (reviewed in Dishion & Tipsord, 2011). For example, in videotaped interactions between delinquent adolescent males, rule-breaking behaviors (e.g., mooning the camera, drug use, obscene gestures) were socially reinforced through laughter, and this was predictive of greater delinquent behavior two years later (Dishion, Spracklen, Andrews, & Patterson, 1996). Importantly however, the very same social learning process reinforced normative and prosocial talk (e.g., non-rule breaking topics such as school, money, family and peer-related issues) in non-delinquent adolescent dyads. This highlights the benefits of hanging out with the right crowd, and shows that imitation and social reinforcement in the peer context can also shape positive development. This section provides an overview of behavioral research that has examined peer socialization of prosocial behaviors during adolescence, as well as the application of peer processes in interventions to promote positive adjustment outcomes.

Peer influence in close friendships.

Prosocial behavior is a broad and multidimensional construct that includes cooperation, donation, and volunteering (Padilla-Walker & Carlo, 2014). Given the association between prosocial engagement during adolescence and a range of adult positive adjustment outcomes (e.g., mental health, self-esteem, and better peer relations; reviewed in Do, Guassi Moreira, & Telzer, 2017), it is crucial to understand how peers can promote these behaviors. There is consistent evidence that best friends influence prosocial behaviors. In adolescent best friend dyads, a friend’s prosocial behavior is related to an individual’s prosocial goal pursuit, which, in turn, is associated with an individual’s prosocial behavior (e.g., cooperating, sharing and helping) (Barry & Wentzel, 2006). These effects are moderated by friendship characteristics, including friendship quality (Barry & Wentzel, 2006) and closeness between friends (Padilla-Walker, Fraser, Black, & Bean, 2015; see Brown, Bakken, Ameringer, & Mahon, 2008 for a comprehensive chapter on pathways of peer influence). In particular, a friend’s prosocial behavior is most likely to influence adolescent’s own prosocial behavior when there is a strong positive relationship and greater closeness between friends, consistent with Sutherland’s differential association theory (Sutherland et al., 1992). Moreover, not only do actual behaviors, but also perceived peer expectations about positive behaviors in the classroom predict greater prosocial goal pursuit and subsequent sharing, cooperating, and helping (Wentzel, Filisetti, & Looney, 2007). These results underscore that getting along with peers is a powerful social motive to behave in positive, prosocial ways. Together, this work suggests that social influence on prosocial behavior is likely explained by processes of social learning (Bandura, 2001).

Peer influence in small groups.

Experimental techniques allow one to manipulate peer effects on prosocial behaviors to better understand the mechanisms of social influence. In one study, we employed a public goods game, in which participants allocated tokens between themselves and a group of peers (Van Hoorn, Van Dijk, Meuwese, Rieffe, & Crone, 2016a). After making decisions individually, participants were ostensibly observed by a group of ten online peer spectators, who provided either prosocial feedback (i.e., likes for donating to the group) or antisocial feedback (i.e., likes for selfish decisions) on their decisions. Adolescents changed their behavior in line with the norms of the spectator group and showed greater prosocial behavior after feedback from prosocial spectators, but became more selfish with antisocial spectators (Van Hoorn et al., 2016a). Results from this study were corroborated by other experimental work showing that peers also positively influence intentions to volunteer (Choukas-Bradley, Giletta, Cohen, & Prinstein, 2015). Moreover, adolescents conformed more to high-status peers’ intentions to volunteer than low-status peers’ intentions to volunteer, suggesting that adolescents are more susceptible to salient peers, consistent with social identity theory (Hogg & Reid, 2006). In sum, experimental studies show that social norms are influential in the domain of prosocial behaviors (cooperation and intentions to volunteer), and can serve both as a vulnerability and an opportunity in adolescent development.

Peer influence in social networks.

Finally, other research has utilized social network analysis to study peer effects in the context of the larger group and highlights that specific characteristics of the larger social group may mitigate or magnify peer effects. For example, findings from one study illustrate that highly central (i.e., high status in larger network, trend setters in school) social groups within the larger network endorsed prosocial as well as aggressive and deviant behaviors, whereas groups with lower centrality (i.e., groups with low acceptance in the larger network) showed magnified socialization of deviant behaviors only (Ellis & Zabartany, 2007). Moreover, adolescents tend to shift between different social groups, and there is evidence for socialization of prosocial behaviors from the attracting social group (i.e., the group to be joined), but not the departing social group (i.e., the group left behind) (Berger & Rodkin, 2012). These results suggest that although adolescent’s membership in different peer groups can influence their engagement in positive and negative behaviors, there is often flexibility in the peer groups adolescents choose to identify with. Thus, to fully grasp peer effects, it is important to study multiple levels of the peer context, taking into account the dynamics between dyads, groups, and the larger social network.

Practical implications of positive peer effects.

The studies reviewed above provide a promising foundation for interventions that employ peer processes in order to potentially increase positive behaviors, as well as redirect negative behaviors during adolescence. One intervention that has shown promising effects is the Good Behavior Game, which teamed up non-disruptive and disruptive children (Van Lier, Huizink, & Vuijk, 2011). When one child reinforced positive and prosocial classroom behaviors, their entire team was rewarded, resulting in more positive peer relations and reduced rates of tobacco experimentation three years later. Another study aimed to redirect collective school norms concerning harassment and utilized social networks to identify social referents (e.g., widely known adolescents or leaders of subgroups) within the school network (Paluck & Shepherd, 2012). They then successfully used these social referents within the school setting to change their peers’ perceptions of norms concerning harassment over the school year, which reduced peer victimization. Collectively, these interventions take advantage of peer processes to change social norms and subsequently promote positive psychosocial outcomes.

B. Family influence on positive adolescent development

A considerable portion of research on social influence during adolescence focuses on the growing effect of peer relations, while deemphasizing the role of the family during this developmental transition. However, characterizing social influence during adolescence is hardly this simple. The family context continues to impact the attitudes, decisions, and behaviors of adolescents, particularly in guiding them toward positive adjustment (e.g., Van Ryzin, Fosco, & Dishion, 2012). The family context is a dynamic system that constantly affects the way in which adolescents think, behave, and make decisions. The family systems model presents these processes as each family member having continuous and reciprocal influence on one another throughout development (Cox & Paley, 1997; Minuchin, 1985). For example, the family context influences each family member’s expectations, needs, desires, and goals. And together, each individual contributes to the family culture, including allocation of resources as well as family rituals, boundaries, and communication (Parke, 2004). To put it simply, the whole is greater than the sum of parts, and the family is no exception during adolescent development (Cox & Paley, 1997). In this section, we review research on families as a salient context for positive adolescent development and provide examples of parents, siblings, and multiple family members together in contributing toward adolescent adjustment.

Parental influence.

The importance of parental influence on positive adolescent development has been well established using longitudinal studies with multiple-informant questionnaires. Many studies converge on the finding that parental management predicts adolescent psychosocial adjustment. Authoritative parenting, which is characterized by frequent involvement and supervision, is associated with higher levels of adolescent academic competence and orientation and lower delinquency compared to other parenting styles (Steinberg et al., 1994). Specifically, parents who are involved in their child’s school life (e.g., attendance, open-house) and who engage in intellectual activities (e.g., reading, discussing current events) tend to have adolescents who display high academic competence and school achievement (Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994). In addition to managing and being involved in the lives of adolescents, parent-child relationship quality also affects adolescent development. Adolescent perceptions of closeness and trust with their parents predict better academic competence, engagement, and achievement (Murray, 2009), as well as decreases in depressive symptoms for girls (Guassi Moreira & Telzer, 2015).

Another approach to investigating parental influence on adolescent development includes examining parental beliefs and behaviors specific to the domain of interest, such as verbally promoting academics or athletics, or buffering against risky sexual behavior. When mothers take interest in, or value a specific behavior, such as doing well in school, their adolescents are also more likely to take interest (Dotterer, McHale, & Crouter, 2009), which is an example of attitude definitions in social learning theory (Akers & Jensen, 2006). One study examined maternal influences on adolescent beliefs and behaviors in the domains of reading, math, art, and athletics across childhood and adolescence. Mothers who displayed relevant beliefs, such as valuing the domain and their child’s competence in the domain, as well as demonstrated relevant behaviors themselves, such as modeling and encouragement, had adolescents who valued and engaged more in each domain (Simpkins, Fredricks, & Eccles, 2012). Collectively, these studies show the power of parental influence on adolescent development through involvement, closeness, and displaying positive beliefs and behaviors. Clearly, parents continue to impact their children’s decisions across adolescence through parental values and parent-child conversations about the adolescent’s friends, whereabouts, and daily lives.

Sibling influence.

Recently, there has been a surge in research examining sibling relationships due to their salient influence on adolescent health and well-being (Conger, 2013). Sibling influences can be especially impactful during developmental transitions (Cox, 2010), helping adolescents navigate new roles and adjust to social and physical changes (Eccles, 1999). Siblings primarily influence each other through two mechanisms: social learning, which is the process of observing and selectively integrating modeled behaviors, and through deidentification, which is the process of actively behaving differently from one another (Whiteman, Beccera, & Killoren, 2009). However, these mechanisms largely depend on one factor—perceptions of support (for a review see, Dirks, Persram, Recchia, & Howe, 2015).

Although research on sibling relationships has traditionally focused on conflict and rivalry as it contributes to negative child and adolescent outcomes, accumulating research suggests that siblings positively influence adolescent development through sibling relationships built upon support (Conger, 2013). Adolescents who perceive general closeness and academic support from siblings are more likely to report positive school attitudes and high academic motivation (Alfaro & Umaña-Taylor, 2010; Milevsky & Levitt, 2005). In addition, experiencing support from a sibling is associated with later feelings of competence, autonomy, and relatedness during adolescence, as well as life satisfaction during the transition into emerging adulthood (Hollifield & Conger, 2015). Further, in the face of stressful life events, perceived affection and closeness from a sibling can buffer against the progression of internalizing behaviors across adolescence (Buist et al., 2014; Gass, Jenkins, & Dunn, 2007). These are just a sample of studies that highlight how powerful sibling relationships can be in socializing adolescents toward prosocial behavior and maintaining well-being. Future work should tap into siblings as a natural resource to bolster positive adolescent development.

The influence of multiple family members.

Although we have reviewed literature examining one parent or one sibling, research has also investigated the combined influence of multiple family members, which reflects the essence of the family systems model (Cox, 2010). Parental and sibling influences are intertwined in adolescent’s daily lives, and thus, are important to investigate together to better inform our understanding of positive adolescent development (Tucker & Updegraff, 2009). Mothers, fathers, and siblings can all contribute to adolescent psychosocial adjustment by providing supervision, acceptance, and opportunities for autonomy (Kurdek & Fine, 1995). For example, high levels of parental involvement and high levels of sibling companionship are associated with lower substance use during adolescence (Samek, Rueter, Keyes, McGue, & Ianoco, 2015). In addition, both observed parental support, and sibling-reported sibling relationship quality, positively contribute to academic engagement during adolescence, and educational attainment in emerging adulthood (Melby, Conger, Fang, Wickrama, & Conger, 2008). Parents and siblings can also work together to buffer adolescents against negative life events. One study found that for adolescent victims of bullying who also experienced low parental conflict and low sibling victimization, boys reported lower levels of depression and girls reported lower levels of delinquency compared to adolescents who experienced high dissatisfaction at home (Sapouna & Wolke, 2013). Moreover, sometimes siblings can provide support when parents come up short. Older siblings can buffer the negative effect of hostile parental behaviors on adolescent externalizing behavior by providing younger siblings with a warm and supportive relationship (Conger, Conger, & Elder, 1994). Together, these studies suggest that adolescent development is heavily influenced by the family context, and by each family member. The social susceptibility and flexibility present during adolescence allows teens to benefit from the influence of multiple family members, even when one source of family influence is compromised. Thus, both parents and siblings need to be examined together to better inform our understanding of how the family can positively influence adolescent decision-making and well-being, including both the nature of influence (e.g., support, involvement) and the degree to which the influence is present (e.g., absent versus helicopter parenting).

C. Family and peer influence on positive adolescent development

Despite extensive research examining how family and peers uniquely influence a wide range of adolescent behaviors, less is known about how these sources of influence simultaneously guide adolescent decision making in positive ways. Indeed, adolescents often face the need to reconcile potential differences in the attitudes and behaviors endorsed by their family relative to peers. Extant research examining social conformity across development supports the reference group theory (Shibutani, 1955), which suggests that individuals adopt the perspectives of different social reference groups (e.g., family or peers) based on their perceived relevance in guiding that decision. Using this theoretical framework, we review literature examining the social contexts in which adolescents rely more on their family or peer influence when faced with conflicting information, which can, in turn, reinforce the development of positive social norms and relationships, as well as promote adaptive decision making.

Susceptibility to social conformity.

Susceptibility to parent versus peer pressures changes with age, resulting in different rates of social conformity across development. One of the earliest methods used to explore how family and peer influence interact and contribute to positive adolescent behaviors was cross-pressures tests, where adolescents respond to hypothetical situations in which their parent and/or peers suggest conflicting actions. From childhood to adolescence, there is a general increase in the tendency for youth to conform to the perspectives of their peers when parents and peers offer conflicting advice (Utech & Hoving, 1969). This supports other work showing the social value of peers is also increasing with age (Bandura & Kupers, 1964), suggesting that, relative to parents, peers may be more successful at reinforcing certain norms or behaviors across development. Consistent with social learning and social identity theories, these results suggest that over the course of adolescence, youth may be shifting their attitudes to align with whichever reference group (e.g., parents or peers) is more salient (i.e., social identity), whose norms may become differentially reinforced over time (i.e., social learning). However, distinct developmental trajectories emerge when adolescents are evaluating different types of behaviors. For example, one study examined parent and peer conformity to prosocial behaviors and found both parent and peer conformity to prosocial behaviors declined from childhood to adolescence (albeit results for peer conformity to prosocial behaviors are inconsistent) (Berndt, 1979). The fact that youth are conforming to their parent or peer influence less often in considering prosocial actions illustrates their increasing ability to make positive decisions independently with age, without the need for a reference group. Not only do these findings suggest that youth seek guidance from parents or peers differently based on the type of behavior under consideration, but they also highlight childhood and early adolescence as an important developmental transition for promoting positive social influence, either by parents or peers.

Flexibility of norms and behaviors.

Evidence from qualitative interview studies demonstrates the flexibility and potential mechanisms by which interacting sources of social influence shape youth’s norms and behaviors. The degree to which parent or peer pressures impact adolescent decision making varies systematically across domains, such that adolescents are more likely to seek guidance about future- or career-oriented topics (e.g., applying for college) from parents and about status- or identity-related topics (e.g., attending social events) from peers (Biddle, Bank, & Marlin, 1980; Brittain, 1963; Sebald & White, 1980). Interestingly, adolescents rely more heavily on parents’ advice when their choices are perceived to be more difficult, such as in situations involving ethical or legal concerns (e.g., reporting a peer’s crime; Brittain, 1963). Another study examined the relative impact of parent and peer norms (e.g., do your parents/peers think you should/shouldn’t do well in school?) versus behaviors (e.g., did your parents/peers do well in school?) on adolescents’ own norms and behaviors as it related to school achievement and alcohol use (Biddle et al., 1980). Adolescents’ alcohol use was more strongly influenced by peers’ behaviors, whereas school achievement was more strongly influenced by parental norms (Biddle et al., 1980). While adolescents can adapt to parent and peer pressures under the appropriate circumstances (e.g., different domains), the extent to which adolescents internalize those pressures—insofar that parent/peer pressures are adopted as adolescents’ own norms—may determine whether those pressures result in more positive or negative decisions.

Parents often influence their adolescents’ peer group affiliations, which also affects the strength and type of norms and behaviors that youth are exposed to. Positive parenting practices lead youth to engage in more adaptive behaviors (e.g., academic achievement), which, in turn, promote affiliation with better peer groups (e.g., “populars” over “druggies;” Brown, Mounts, Lamborn, & Steinberg, 1993). In fact, peer pressures are generally stronger within positive domains (e.g., school achievement) compared to negative domains (e.g., misconduct), especially among social groups that are well interconnected (i.e., less alienated) within the school structure (Clasen & Brown, 1987). These studies highlight the significant role that parents can play in promoting prosocial peer affiliations, which may subsequently facilitate opportunities for peers to positively influence youth’s decision making.

Protective role of positive relationships.

In addition to promoting prosocial peer affiliations, positive social figures can buffer adolescents against negative social pressures over time. Positive family influence can attenuate the potentially negative impact of peers on adolescents’ well-being. Indeed, warm family relationships and environments promote resilience to peer bullying (Bowes, Maughan, Caspi, Moffitt, & Arseneault, 2010) and mitigate the effect of peer pressure on alcohol use (Nash, Mcqueen, & Bray, 2005) among youth. As peers become increasingly important across adolescence, positive peer influence can similarly protect against aversive family experiences. For example, family adversity (e.g., harsh discipline) is not associated with child externalizing behaviors for youth with high levels of positive peer relationships (Criss, Pettit, Bates, Dodge, & Lapp, 2002). This highlights the potential of strong peer support in redirecting negative developmental trajectories, particularly among vulnerable youth.

In some cases, peers may serve as a stronger buffer against poor developmental outcomes than parents. One study examined how the perceived expectations of mothers and friends influenced adolescents’ engagement in antisocial and prosocial behaviors (Padilla-Walker & Carlo, 2007). Adolescents indicated how strongly they personally agreed with the importance of engaging in several prosocial behaviors (e.g., helping people), as well as rated how much they felt their mother versus friends expected them to engage in these same prosocial behaviors. Adolescent boys who perceived their peers to have stronger expectations of their prosocial engagement actually participated in fewer antisocial behaviors; there was no effect of maternal expectations or personal values on their antisocial behaviors. Thus, positive peer influence may be more protective against antisocial behaviors for adolescent boys relative to girls. In contrast, both the perceived expectations of mothers and friends were related to adolescents’ personal prosocial values, which subsequently influenced their prosocial behaviors. Although peers may be a stronger protective factor against negative behaviors compared to family, adolescents rely on the social norms of both their family and peers to inform their own values and choices about engaging in more adaptive, positive behaviors (a la social identity theory). In the following sections, we review prominent neurobiological theories, which describe how heightened social influence susceptibility during adolescence may reflect maturational changes in how the brain responds to social information.

IV. Neurobiological Models of Adolescents’ Social Influence Susceptibility

Often described as a car in full throttle with ineffective brakes, the adolescent brain was originally thought to be defective in some way (see Payne, 2012). However, based on functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) research, we now know that the teenage brain is rapidly changing and adapting to its environment in ways that promote skill acquisition, learning, and social growth (see Telzer, 2016). Indeed, the adolescent period is marked by dramatic changes in brain development, second only to that seen in infancy. Such changes in the brain uniquely sensitize adolescents to social stimuli in their environment, and may underlie social influence susceptibility – for better or for worse.

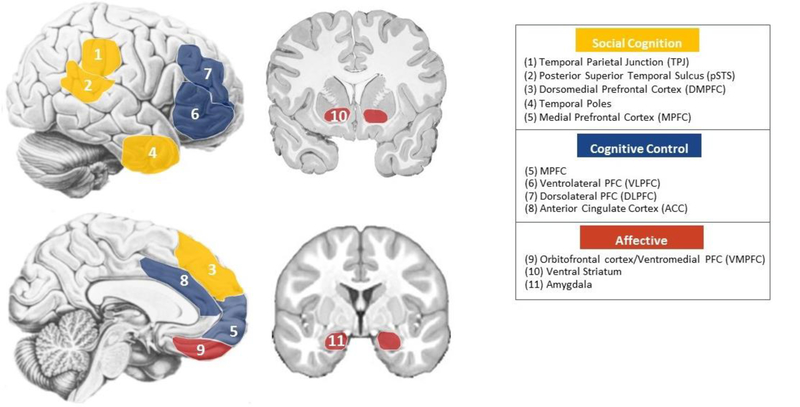

Social influence susceptibility may reflect a (1) heightened orientation to social cues, (2) greater sensitivity to social rewards and punishments, and (3) compromised cognitive control. Indeed, adolescence is characterized by changes in neural circuitry underlying each of these processes (see Figure 1). For instance, complex social behaviors, including the ability to think about others’ mental states such as their thoughts and feelings, to reason about others’ mental states to inform one’s own behaviors, and to predict what another person will do next during a social interaction (Frith & Frith, 2007; Blakemore, 2008) involve the recruitment of brain regions including the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC). Moreover, the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) is involved in thinking about the self and close others (Kelley et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2002). These brain regions tend to be more activated among adolescents relative to adults when processing social information (Blakemore, den Ouden, Choudhury, & Frith, 2007; Burnett, Bird, Moll, Frith, & Blakemore, 2009; Gunther Moor et al., 2012; Pfeifer et al., 2009; Van den Bos, Van Dijk, Westenberg, Rombouts, & Crone, 2011; Wang, Lee, Sigman, & Dapretto, 2006; Somerville et al., 2013), underscoring adolescence as a key period of social sensitivity (Blakemore, 2008; Blakemore & Mills, 2014).

Figure 1.

Neural regions involved in social cognition (yellow), cognitive control (blue), and affective processing (red).

Brain regions involved in affective processing include the ventral striatum (VS), which is implicated in reward processing, including the receipt and anticipation of primary and secondary rewards (Delgado, 2007), the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), which is involved in the valuation of rewards and hedonic experiences (Saez et al., 2017; Kringelbach, 2005), and the amygdala, which is involved in detecting salient cues in the environment, responding to punishments, and is activated to both negative and positive emotional stimuli (Hamann, Ely, Hoffman, & Kilts, 2002). Compared to children and adults, adolescents show heightened sensitivity to rewards in the VS (Galvan et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2006; Eshel et al., 2007), particularly in the presence of peers (Chein et al., 2010). Adolescents also show heightened VS and amygdala activation to socially appetitive stimuli (Perino et al., 2016; Somerville et al., 2011). Thus, adolescents may be uniquely attuned to salient social rewards in their environment.

Finally, brain regions involved in regulatory processes include lateral and medial areas of the prefrontal cortex (e.g., VLPFC, DLPFC, MPFC, ACC). These regions are broadly involved in cognitive control, emotion regulation, goal directed inhibitory control, and serve as a neural brake system (Wessel et al., 2013). Both age-related increases and decreases in PFC activity have been reported across development, such that some studies find that adolescents show heightened PFC activation compared to adults, whereas other studies report adolescent suppression of the PFC (Bunge et al., 2002; Booth et al., 2003; Durston et al., 2006; Marsh et al., 2006; Rubia et al., 2007; Velanova et al., 2009). Such discrepant developmental patterns of activation have been theorized to underlie flexibility and learning, promoting exploratory behavior in adolescence (see Crone and Dahl, 2012).

Based on emerging developmental cognitive neuroscience research, many theoretical models have been proposed to describe adolescents’ neurobiological sensitivity to social context (see Schriber & Guyer, 2016). While several of these models explain neural changes that underlie vulnerabilities during adolescence (e.g., heightened risk taking and psychopathology; Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008; Steinberg, 2008; Ernst, Pine, & Hardin, 2006), these models can be useful heuristics for broadly describing adolescent brain development and social sensitivity, as well as opportunities for positive adjustment (but see Pfeifer & Allen, 2012, 2016, for why these models are too simplified).

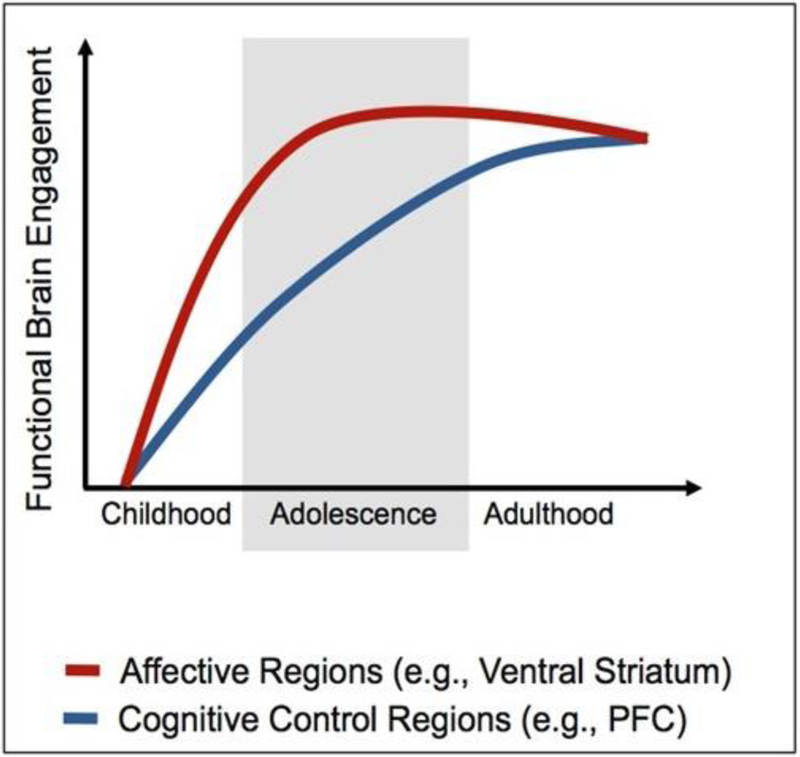

A. Imbalance Model

The Imbalance Model (Somerville, Jones, & Casey, 2010; Casey et al., 2008) proposes that the subcortical network, comprising neural regions associated with the valuation of rewards (e.g., ventral striatum (VS)), matures relatively early, leading to increased reward seeking during adolescence, whereas the cortical network, comprising neural regions involved in higher order cognition and impulse control (e.g., ventral and dorsal lateral prefrontal cortices (VLPFC, DLPFC)), gradually matures over adolescence and into adulthood. The differential rates of maturation in the cognitive control and affective systems creates a neurobiological imbalance during adolescence, which is thought to bias adolescents towards socioemotionally salient and rewarding contexts during a developmental period when they are unable to effectively regulate their behavior (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Imbalance Model of adolescent brain development. Earlier developmental of affective, reward-related activation (red line) and relatively later and more protracted development of cognitive control (blue line) result in a neurobiological imbalance during adolescence (depicted by the grey box).

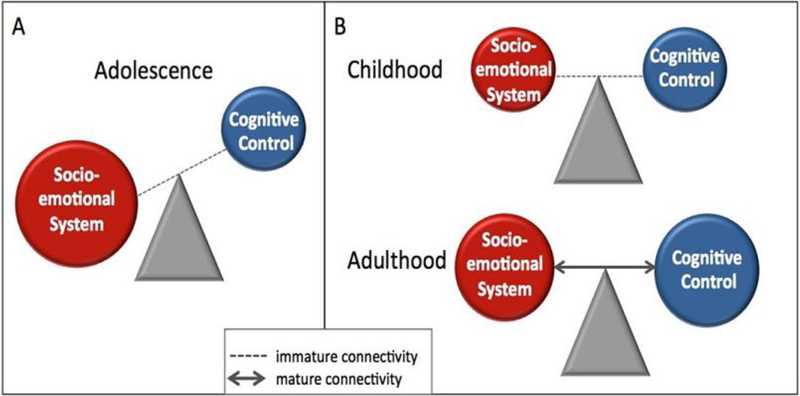

B. Dual Systems Model

The Dual Systems Model discusses a balance between “hot” and “cool” systems (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). The cool system focuses on the cognitive control system, which is emotionally neutral, rational, and strategic, allowing for flexible, goal-directed behaviors, whereas the hot system focuses on the emotional system, which is emotionally reactive and driven by desires (see Casey, 2015). During adolescence, the hot system is overactive, and the cool system is not yet fully mature. Similar to the Imbalance Model, the Dual Systems Model describes relatively early and rapid developmental increases in the brain’s socioemotional “hot” system (e.g., VS, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex) that leads to increased reward- and sensation-seeking in adolescence, coupled with more gradual and later development of the brain’s cognitive control “cool” system (e.g., lateral PFC) that does not reach maturity until the late 20s or even early 30s (Steinberg, 2008; Shulman et al., 2016). The temporal gap between these systems is thought to create a developmental window of vulnerability in adolescence during which youth may be highly susceptible to peer influence due to the socioemotional nature of peer contexts (Steinberg, 2008). Although children still have relatively immature cognitive control, they do not yet evidence this heightened orientation towards reward-driven behaviors, and adults have relative maturity of cognitive control and strengthened connectivity across brain networks that facilitate top-down regulation of reward-driven activation. Therefore, the temporal gap between affective and regulatory development is only present in adolescence (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dual Systems Model of adolescent brain development. (A) Adolescence is characterized by hyperactivation of the “hot” socioemotional system (red circle) coupled with later developing cognitive control (blue circle), and immature connectivity (dotted line) between systems, resulting in an ability to engage in effective regulation. (B) Childhood is characterized by not yet maturing “hot” or “cold” systems, whereas adulthood is characterized by mature “hot” and “cold” systems, coupled with effective connectivity (double arrow) between systems.

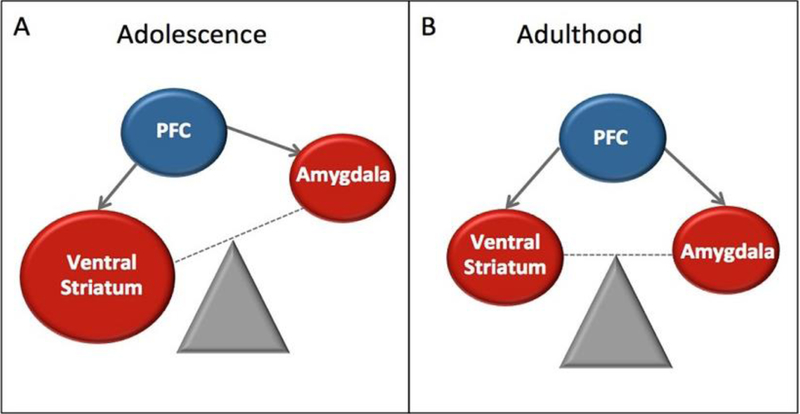

C. Triadic Neural Systems Model

The Triadic Neural Systems Model includes the cognitive control system as well as two affective systems, an approach, reward-driven system, which centers on the VS, and an avoidance/emotion system, which centers on the amygdala, a brain region involved in withdrawal from aversive cues and avoidance of punishments (Ernst, 2014). Whereas the VS supports reward processes and approach behavior, the amygdala serves as a “behavioral brake” to avoid potential harm (Amaral, 2002), and the PFC serves to orchestrate the relative contributions of the approach and avoidance systems (see Ernst et al., 2006). The balance between reward-driven behaviors and harm-avoidant behaviors is tilted, such that adolescents are more oriented to rewards and less sensitive to potential harms, and the immature regulatory system fails to adaptively balance the two affective systems (see Figure 4). Thus, adolescents will be more likely to approach, but not avoid, risky and potentially harmful situations, whereas adults’ more mature regulatory system effectively balances approach and avoidance behaviors, thereby decreasing the likelihood of risk behaviors.

Figure 4.

Triadic Systems Model of adolescent neurodevelopment. (A) Adolescents show heightened approach behaviors (ventral striatum), are less sensitivity to harm (amygdala), and have an immature regulatory system (PFC) that does not effectively balance the approach and avoidance systems. (B) Adults have mature regulatory capabilities that effectively balance the approach and avoidance systems.

D. Social Information Processing Network

The Social Information Processing Network model (SIPN; Nelson et al., 2005; Nelson, Jarcho, & Guyer, 2016) proposes that social stimuli are processed by three nodes in sequential order. The detection node first categorizes a stimulus as social and detects its basic social properties. This node includes regions such as the superior temporal sulcus (STS), intraparietal sulcus, fusiform face area, temporal pole, and occipital cortical regions. After a stimulus has been identified, it is processed by the affective node, which codes for rewards and punishments and determines whether stimuli should be approached or avoided. This node includes regions such as the amygdala, VS, and orbitofrontal cortex. Finally, social stimuli are processed in the cognitive-regulatory node, which performs complex cognitive processing, including theory of mind (i.e., mental state reasoning), cognitive inhibition, and goal-directed behaviors. This node includes regions such as the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and dorsal and ventral prefrontal cortices. These three nodes function as an interactive network, largely in a unidirectional way, from detection to affective to cognitive, but there are also bidirectional pathways. Similar to all of the models discussed above, the affective node is particularly reactive and sensitive during adolescence, whereas the cognitive-regulatory node shows more protracted development into adulthood. Each of the models discussed so far suggest that differential neural development and overreliance on subcortical, reward-related regions drives adolescents to seek out (social) rewards in their environment at a developmental period when self-control is still maturing. While social contexts may tip the balance in terms of affective and cognitive control-related activation, these models do not take into consideration neural regions that specifically code for higher-order social cognition.

E. Neurobiological Susceptibility to Social Context Framework

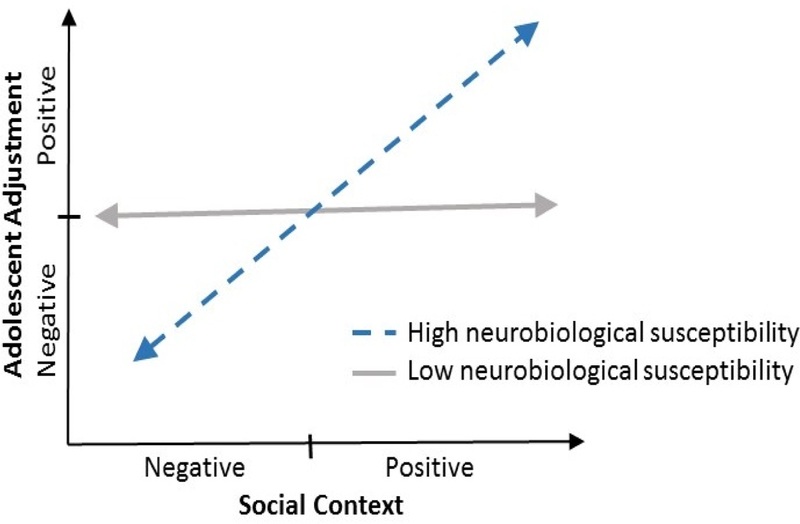

Perhaps the most promising model for understanding adolescents’ susceptibility to social influence, particularly in regards to positive social influence, stems from the Neurobiological Susceptibility to Social Context Framework (Schriber & Guyer, 2016), which is based on other theoretical frameworks including biological sensitivity to context (Boyce & Ellis, 2005) and differential susceptibility to environmental influences (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). This model proposes that individuals vary in their sensitivity to the social environment as a function of biological factors, particularly neural sensitivity to social contexts. While specific neural biomarkers are not specified, Schriber and Guyer (2016) build on the existing models of brain development discussed above to suggest that adolescents with high neurobiological susceptibility can be pushed in a for-better or for-worse fashion, depending on their social environment (Figure 5). In particular, individuals who are not highly sensitive will not be affected by either positive or aversive social environments, whereas highly sensitive individuals will be both more vulnerable to aversive contexts (e.g., negative peer influence effects), but also more responsive to salubrious contexts (e.g., positive peer influence effects). In other words, those who have supportive peers and family will thrive, whereas those who face family or peer rejection will be most vulnerable.

Figure 5.

Neurobiological susceptibility to social influence model. Adolescents with high neurobiological susceptibility (blue dashed line) thrive in positive contexts but are vulnerable in negative contexts.

V. Neural Correlates of Peer and Family Influence

While current neurobiological models or cognitive neuroscience research have yet to clearly connect how social influence processes (e.g., social learning theory, social identity theory) map onto neurobiological development, emerging research has begun to highlight how peer and family contexts influence adolescent neurodevelopment. These studies highlight a set of neural candidates to examine as promising indices of adolescents’ susceptibility to social influence. In particular, neural regions involved in (1) affective processing of social rewards and punishments (e.g.,VS, amygdala), (2) social-cognition and thinking about others’ mental states (e.g.,TPJ, MPFC), and (3) cognitive control that facilitates behavioral inhibition (e.g., VLPFC, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)) show sensitivity to peer and family contexts (see Figure 1). Below we review recent research unpacking the neurobiological correlates of peer and family influence, highlighting studies that focus on positive social influence.

A. Peer Relationships and Neurobiological Development in Adolescence

Prior research has largely focused on the supposed monolithic negative influence of peers (e.g., deviancy training) at both the behavioral (e.g., Dishion et al., 1996) and neural level (Chein, Albert, O’Brien, Uckert, & Steinberg, 2011). This research supports the widely held notion that adolescents are more likely to take risks in the presence of their peers, and this is modulated by heightened ventral striatum activation, suggesting that peers increase the salient and rewarding nature of taking risks (Chein et al., 2011). However, it is essential to also examine positive peer influences. If adolescents are highly sensitive to peer influence due to heightened neurobiological sensitivity to social context, then in addition to being pushed to engage in negative behaviors (e.g., risk taking), peers should be able to push teens to engage in more positive behaviors (e.g., prosocial behaviors).

Positive peer influence.

In a recent neuroimaging study, we examined whether peer presence and positive feedback affected adolescents’ prosocial behaviors (donation of tokens to their group in a public goods game) and associated neural processing (Van Hoorn, Van Dijk, Güroğlu, & Crone, 2016). Adolescents donated significantly more to a public goods group when they were being observed by their peers, and even more so when receiving positive feedback (i.e., thumbs up) from their peers. Prosocial decision-making in the presence of peers was associated with enhanced activity in several social brain regions, including the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), TPJ, precuneus and STS. Effects in the dmPFC were more pronounced in early adolescents (12–13 year olds) than mid-adolescents (15–16 year olds), suggesting that early adolescence may be a window of opportunity for prosocial peer influence. Interestingly, these findings revealed that social brain regions, rather than affective reward-related regions, underlie prosocial peer influence. These findings underscore early adolescents as particularly sensitive to social influence, but in a way that promotes positive, prosocial behavior.

Researchers have also examined how the context of risk-promoting or risk-averse social norms affects adolescents’ risk taking. In a recent study, researchers had adolescents complete a cognitive control task during an fMRI scan, and used a “brain as predictor of behavior” approach to test how the neural correlates of cognitive control affect adolescents’ conformity to peer influence (Cascio et al., 2015). One week following the scan, adolescents returned to the lab to undergo a simulated driving session in the presence of either a high- (e.g., indicating their driving behavior is more risky than the participant) or low- (e.g., indicating their behavior is less risky and more cautious than the participant) risk-promoting peer. Adolescents made fewer risky choices in the presence of low-risk peers compared to high-risk peers. At the neural level, adolescents who recruited regions involved in cognitive control(e.g., lateral PFC ) during the cognitive control task were more influenced by their cautious peers, such that cognitive control-related activation was associated with safer driving in the presence of cautious peers. Such activation was not associated with being influenced by risky peers or driving behavior when alone. Engagement of the PFC during the cognitive control task may represent a neurobiological marker for more thoughtful and deliberative thinking, allowing adolescents to override the tendency to be risky and instead conform to their more cautious peers’ behavior. This study highlights that social influence susceptibility may be a regulated process as opposed to a lack of inhibition, and also points to the positive side of peer conformity.

Supportive peer friendships.

In addition to examining how peers may influence adolescents to engage in more positive behaviors, researchers have examined the role of supportive peer friendships in buffering adolescents from negative outcomes. The need for social connection and peer acceptance is one of the most fundamental and universal human needs (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). As peer relationships increase in importance during adolescence, close friendships become their primary source of social support (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). When adolescents do not feel socially connected, it poses serious threats to their well-being. Fortunately, social connection and close friendships can buffer adolescents from the distress associated with negative peer relations. In a recent study, we tested the stress-buffering model of social relationships (Cohen, Gottlieb, & Underwood, 2001) to examine whether supportive peer relationships can attenuate the negative implications of chronic peer conflict (Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman, Miernicki, & Galvan, 2015). Adolescents reporting chronic peer conflict engaged in more risk-taking behavior, and at the neural level, showed increased activation in the ventral striatum when making risky choices. But those adolescents reporting high peer support were completely buffered from these effects – those experiencing high peer conflict did not engage in more risk taking or show heightened ventral striatum activation during risky decisions when they had a close friend. These findings highlight the vital role that supportive friends play. Even in the face of peer conflict, having a close friend can provide the means to feel connected to a social group and receive emotional support and guidance, which may provide them with a means of coping with stress.

B. Family Relationships and Neurobiological Development in Adolescence

In addition to investigating the role of peers on positive adolescent adjustment, developmental social neuroscientists have also examined the influence of the family. In the following section, we review neuroimaging work on how the family context contributes to adolescent adjustment through family norms and values, positive family relationships, and parental monitoring.

Familial norms and values.

One way researchers have examined familial influence on positive youth adjustment and brain development is to examine the internalization of family values. Often referred to as “familism” or “family obligation,” youth from Latin American families, for example, stress the importance of spending time with the family, high family unity, family social support, and interdependence for daily activities (Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995; Fuligni, 2001). The internalization of strong family obligation values is associated with lower rates of substance use (Telzer, Gonzales, & Fuligni, 2014) and depression (Telzer, Tsai, Gonzales, & Fuligni, 2015) in Mexican-American adolescents, underscoring family obligation as an important cultural resource. At the neural level, we found that higher family obligation values were associated with greater activation in the DLPFC during a cognitive control task, which was associated with better decision making skills (Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman, & Galvan, 2013a), suggesting that by putting their family’s needs first and delaying personal gratification for their family, youth may develop more effective cognitive control, helping them to avoid the impulse to engage in risky behaviors. In addition, higher family obligation values were associated with lower activation in the VS during a risk-taking task, which was associated with less self-reported risk-taking behavior (Telzer et al., 2013a). Youth with stronger family obligation values report more negative consequences for engaging in risk taking, as it may reflect poorly upon their family (German, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2009). Thus, risk taking itself may become less rewarding, as evidenced by dampened VS activation.

We also examined whether the rewarding and meaningful nature of family obligation itself offsets the rewards of risk taking. First, we found that engaging in family obligation (i.e., making decisions that benefit the family) recruits the VS, even more so than gaining a personal reward for the self, suggesting that decisions to make sacrifices for the family are personally meaningful and rewarding (Telzer, Fuligni, & Galvan, 2016). Secondly, we correlated VS activation during the family obligation task with VS activation during the risk-taking task described above. Adolescents who had heightened VS activation during the family obligation task showed less activation in the same brain region during the risk-taking task, suggesting that the rewarding nature of family obligation may make risk taking comparatively less rewarding (Telzer et al., 2016). Importantly, increased activation in the VS during the family obligation task predicted longitudinal declines in risky behaviors and depression, whereas increased VS activation during the risk taking task predicted increases in psychopathology (Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman, & Galvan, 2013b, Telzer et al., 2015). Thus, finding meaning in social, other-focused behaviors (i.e., family obligation) can promote positive youth adjustment, whereas being oriented towards more self-focused behaviors (i.e., risk taking) is a vulnerability. Together, these findings suggest that the internalization of important family values is rewarding and meaningful, buffering adolescents from both risk taking and depression.

Positive family relationships.

Besides family values, the quality of family relationships also influences adolescents’ positive adjustment – high family support and cohesion and low conflict are associated with a host of positive outcomes, including better school performance, lower substance use, and lower internalizing symptoms (Melby et al., 2008; Samek et al., 2015; Telzer & Fuligni, 2013). According to social control theories, adolescents who are close to their parents feel obligated to act in non-deviant ways, whereas adolescents in conflictual families do not feel obligated to conform to their parents’ expectations and will be more likely to engage in risky behaviors (Bahr et al., 2005). Thus, strong family relationship quality can buffer adolescents from risk taking, perhaps by making risk taking less rewarding. In one longitudinal fMRI study, we examined changes in the quality of family relationships, paying particular attention to three dimensions of positive family interactions: high parental support (e.g., their parents respected their feelings), adolescents’ spontaneous disclosure (e.g., telling their parents about their friends), and low family conflict (e.g., having a fight or argument with their parents). Adolescents who reported improvements in the quality of their family interactions showed longitudinal declines in risk taking, which was mediated by declines in VS activation during a risk-taking task (Qu, Fuligni, Galvan, Lieberman, & Telzer, 2015). This study suggests that increases in positive family relationships may provide adolescents with a supportive environment, increasing their desire to follow their parents’ expectations, which may dampen their subjective sensitivity to rewards during risk taking. In addition to examining cohesion and conflict, this study assessed adolescents’ disclosure to their parents. Given that adolescents spend increasingly less time with their parents than do children (Lam, McHale, & Crouter, 2012; 2014), voluntary disclosure of their activities may provide opportunities for parents to give their children advice and supervision, helping them develop the skills to avoid risks and devalue the rewarding nature of risk taking.

Parental monitoring.

In addition to adolescents’ spontaneous disclosure, parental monitoring plays a key influence on adolescents’ decisions to avoid deviant behaviors. Yet, during the adolescent years, parents tend to decrease their supervision of their children, and adolescents are more likely to make maladaptive decisions during unsupervised time or in the presence of their peers (Richardson, Radziszewska, Dent, & Flay, 1993; Beck, Shattuck, & Raleigh, 2001; Borawski, Ievers-Landis, Lovegreen, & Trapl, 2003). In a recent study, we tested how the presence of parents changes the way adolescents make decisions in a risky context. During an fMRI scan, adolescents played a risky driving game twice: once alone, and once with their mother present and watching. Whereas adolescents take greater risks when their friends are watching them during this same task (Chein et al., 2011), we found that adolescents made significantly fewer risks when their mother was present (Telzer, Ichien, & Qu, 2015).

At the neural level, the presence of friends is associated with more VS activation (Chein et al. 2010), whereas the presence of mothers is associated with less VS activation when making risky choices (Telzer, Ichien, & Qu, 2015). Importantly, this protective role is specific to mothers, as we did not find the same decrease in risk taking or ventral striatum activation when an unknown adult was present (Guassi Moreira & Telzer, in press). Together, these findings suggest that peers may increase the rewarding nature of risk taking, whereas mothers may take the fun away. In addition, neural regions involved in cognitive control (e.g., VLPFC, MPFC), were more activated when their mother was present than when alone or in the presence of an unknown adult, suggesting that maternal presence may facilitate more mature and effective neural regulation via top-down inhibitory control from prefrontal regions. Finally, after making a risky decision, adolescents recruited regions involved in mentalizing (e.g., TPJ) more when their mother was present than an unknown adult, suggesting that adolescents are more sensitive to their mother’s perspective following a brief instance of misbehavior (i.e., running the yellow light). Together, these findings suggest that the presence of mothers alters the way adolescents make risky decisions and may provide an important scaffolding role, helping adolescents avoid risks by decreasing the rewarding nature of risks and promoting more effective cognitive control.

C. Simultaneous Role of Family and Peer Relationships on Adolescent Brain Development

Although few neuroimaging studies have examined the simultaneous influence of family and peers on adolescent development, there is emerging evidence suggesting that adolescents’ choices are affected, in part, by differential neural sensitivity to family versus peers. In order to capture how behavior and brain function change in the context of family and peers, researchers have mainly examined within-person differences between decisions that affect a family member (primarily parents) compared to decisions that affect peers. In addition, novel research designs have recently stimulated investigations of the simultaneous influence of both parent and peer influence on adolescent decision making, which are also discussed in this section.

Emotional reactivity to peers and parents.

Prior research consistently characterizes adolescence as a time of social reorientation from parent to peer influences, a process thought to be supported by developmental changes within several affective and social cognitive brain regions (Nelson et al., 2005). However, only recently has research emerged showing that this social reorientation at the behavioral level is paralleled by functional changes at the neural level, such that simply processing peer versus parent faces elicits different neural responses in regions involved in socioemotional processing during adolescence. In a study examining adolescents’ emotion perception of their mother’s, father’s and an unknown peer’s faces, adolescents exhibited greater activation in regions implicated in social (PCC, pSTS, TPJ) and affective (VS, amygdala, hippocampus) processing when viewing their peer relative to parent faces (no difference between processing maternal or paternal stimuli; Saxbe, Del Piero, Immordino-Yang, Kaplan, & Margolin, 2015). This illustrates that the neural correlates underlying socioemotional processing change over the course of adolescence as the salience of peers increases relative to family. Moreover, although adolescents, on average, showed greater activation in the PCC and precuneus to peer versus parent faces, those who showed less of this effect (i.e., did not show greater activation in these regions to peer over parent faces) engaged in lower levels of risk-taking behaviors and affiliation with deviant peers. Thus, less recruitment of regions involved in social cognition (e.g., mentalizing) toward peers relative to parents may help to diminish the social value of peer influence on negative behaviors during adolescence.

Vicarious rewards for peers and parents.

Differential neural sensitivity to peers versus parents can be leveraged to promote adaptive decision making during adolescence, specifically by encouraging vicarious learning about other-oriented behaviors. Even in the absence of a personally experienced reward, the act of seeing or imagining others experience rewards (i.e., vicarious rewards) elicits activation in reward-related regions (VS) and promotes prosocial motivations (Mobbs et al., 2009). Given the heightened salience of peer and parent influence during adolescence, it is important to explore whether exposure to vicarious rewards that affect close others might reinforce positive choices. Vicarious learning, especially through observing the positive behaviors and outcomes of close others, can facilitate the internalization of positive social norms and increase motivation to model similar behaviors in the future, which is consistent with social learning theory. A recent study examined VS activation during a risk-taking task, where the potential gains and losses could affect adolescents’ mothers or best friends (Braams & Crone, 2016). Striatal activation peaked in adolescence compared to childhood and young adulthood when youth took risks to win money for their mothers, but not for their peers. Self-report data further demonstrated a positive association between relationship quality and the extent to which adolescents enjoyed taking risks to win money for both their mothers and best friends. Therefore, developmental changes in reward sensitivity and relationship quality can affect adolescents’ motivation to engage in risky behaviors that affect others over time. Indeed, a new perspective from developmental neuroscience proposes that, in some contexts, adolescents may be taking risks with the explicit intention of helping others (Do et al., 2017), a process that may be supported by neural reactivity in reward-related regions to the experience of vicarious rewards for close others.

Balancing conflicting social influence from peers and parents.

A common feature of adolescent decision making is the balance of conflicting social information from parents and peers. This is an important area of inquiry, as peer and family values and norms often differ, resulting in norm conflicts that inevitably affect adolescent decision making and beg for reconciliation. In one of the first developmental studies to examine the neural correlates of both parental and peer influence on attitude change, we first asked adolescents, their primary caregiver, and several peers from their schools to each independently evaluate artwork stimuli prior to their scan (Welborn et al., 2015). Artwork was selected, as it tends to be neutral stimuli where attitudes may be swayed by influence. Adolescents completed an fMRI session a few weeks later, where they were shown their parents’ or peers’ real evaluations of the same pieces of artwork before re-evaluating the stimuli. Adolescents were more likely to change their own attitudes to bring them in line with those of their parents compared to their peers. At the neural level, adolescents exhibited greater activation in regions involved in mentalizing (TPJ, precuneus), reward processing (ventral medial prefrontal cortex, VMPFC), and self-control (VLPFC) when they were influenced by both their peers and parent, with no difference between the source of social influence. Moreover, greater activation in these task-responsive regions predicted a greater likelihood for youth to shift their attitudes in favor of the corresponding source of influence. Thus, although family and peers influence adolescents through similar neural mechanisms (involved in mentalizing, reward processing, and regulation), individual differences in this neurobiological sensitivity might differentially predict adolescents’ tendency to adopt the attitudes and/or behaviors of their family or peers.

While prior research has examined neural differences between social influence from family and peers, no study to date has delineated how youth incorporate the simultaneous influence of their family and peers into their decisions and behaviors. When there is a discrepancy between peers’ and parents’ attitudes about a behavior, adolescents often need to simultaneously weigh the relative value of these conflicting attitudes when deciding whether to personally endorse that behavior, which may differ depending on if it is positive or negative. Over time, their decision to conform to the attitudes of one influence over the other can have important implications for reinforcing their participation in those behaviors. For example, an adolescent who endorses drug use as a means of conforming to the attitudes favored by their peers, but is discouraged by their parents, may be more likely to do drugs over time. We recently examined this process in an fMRI study, where we showed adolescents their parents’ and peers’ evaluations of positive and negative behaviors at the same time, each of which differed from each other and were manipulated to conflict with adolescents’ initial evaluations (Do, McCormick, & Telzer, unpublished data). To measure the extent to which adolescents were affected by conflicting social information, adolescents indicated whether they agreed with their parent or peers’ evaluations of each behavior. On average, adolescents showed differences in neural activation within affective and reward-related regions when agreeing more with their peers than parents (collapsed across both positive and negative behaviors), highlighting the important role of these regions in reconciling conflicting social information from parents and peers, and ultimately agreeing with the peer. Overall, this research highlights the need to further investigate how interactions between family and peer influence differentially affect adolescent decision making, with the goal of identifying opportunities to leverage adolescents’ increased social and neurobiological susceptibility in favor of positive developmental outcomes.

VI. Conclusions and future directions