Motivational Interviewing

Miller and Rollnick (2012, p. 29) define motivational interviewing (MI) as “a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication with particular attention to the language of change . . . designed to strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion.” MI is based on empirical evidence that documents the basic principle that the way people talk about change can be related to the way they act. Simply stated: The more someone talks about or argues for change, the more likely it is that he or she will change. Conversely, the more one verbalizes reasons against change, the less likely it is that he or she will change. MI helps accelerate the change process “by literally talking oneself into change” (Miller & Rollnick, 2012, p. 168).

Several studies have shown that when MI is used in substance abuse and health care settings, the clients are more likely to stay in treatment longer, put forth more effort during treatment, adhere more closely to the intervention protocol or recommendations, and experience significantly more improved outcomes than clients who receive identical treatment without the MI component (Aubrey, 1998; Bien et al., 1993; Brown & Miller, 1993; Saunders et al., 1993). Recently, adaptations of MI, created for use with parents of children in mental health settings, have demonstrated promise for removing motivational barriers and producing desirable changes in adult behavior. These positive effects have been associated with subsequent changes in child behavior (Connell, et al., 2008; Dishion et al., 2008, 2010; Gardner et al., 2009; Lunkenheimer et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2013).

Motivational Interviewing in Schools

MI has important potential applicability to address similar problems related to parent, teacher, and student engagement and poor implementation of evidence-based practices within schooling contexts. Several research groups have leveraged MI as a mechanism of change within educational settings to improve the social and academic functioning of students who are at risk of developing emotional and behavioral disorders that interfere with their academic performance and formation of social support networks (Frey et al., 2011; Herman et al., 2014; Reinke et al., 2013). In some situations, MI has also been influential as a guiding framework for developing the intervention protocol (Frey et al., 2014; Reinke et al., 2008, 2011; Strait et al., 2012; Terry et al., 2013). Additionally, coaching procedures based on the MI approach have been employed to improve implementation fidelity of well-established interventions such as First Step to Success (Lee, Frey, Walker, et al., 2014), Parent Coping Power (Herman et al., 2012), and Promoting Alternative Thinking Skills (Reinke et al., 2012). The promise of MI’s effective use within the context of school-based intervention research and practice is substantial and is likely to be the focus of considerable future research and practice.

Relatively little is currently known about the feasibility of establishing MI competency among school personnel or how to evaluate it. Yet, the successful transfer of MI’s full impact and advantages into educational settings will likely depend on the extent to which specialized instructional support providers (e.g., school social workers, school psychologists, school counselors, behavioral coaches) implement the approach competently. To date, few studies have examined training procedures and MI skill acquisition of school-based personnel. Burke, Da Silva, Vaughan, and Knight (2005) conducted a single MI training session on the principles of MI with high school counselors. From anecdotal counselor reports, they concluded that the participants had identified several benefits of learning the MI approach. As well, Caldwell and Kaye (2014) employed a single-group post-test-only design in which 84 student services staff were able to demonstrate limited MI skills when presented with a structured student role play following a one-day training. Caldwell and Kaye advocate continued learning opportunities as well as integration of skills development into everyday practice to sustain acquired skills. Finally, Frey, Lee et al. (2013) reported that interventionists demonstrated acceptable levels of MI proficiency via conversations with teachers and parents following participation in a developmental grant to infuse MI principles into the First Step to Success early intervention program (Frey et al., 2014).

There are several key questions that must be addressed before MI can be considered a viable approach to improve implementation fidelity within school settings (Herman et al., 2014). They are:

How much training, supervision, and practice are required to improve one’s MI proficiency?

What level of competency is sufficient to affect teacher, parent, or adolescent behavior change?

What standards should be used to evaluate MI competency?

The MITAS Training Component

This article describes the Motivational Interviewing Training and Assessment System (MITAS), and presents the results of a feasibility study conducted to evaluate some of the questions posed by Herman and colleagues.

Miller and Moyers’ (2006) eight-stage model of learning MI has been the primary theoretical framework guiding MI professional development efforts to date. Hartzler and colleagues (2010) suggest that the development of MI competency is a multi-stage process whereby relational and technical skill development occurs in contrived settings with practice and feedback. Proficiency, which is defined by the application of these skills within context-specific clinical encounters, is, however, developed in later stages.

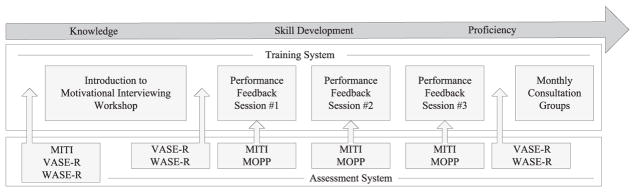

The MITAS contains a training component and an assessment component. Both are described below and depicted in Figure 1. The training component consists of a multi-session workshop, delivered flexibly, depending on the needs of the participants. The training component may also include up to three individualized coaching sessions in which participants receive performance feedback on their use of MI from a practitioner who is well versed in school-based MI. Finally, the training component may include monthly consultation groups, or professional learning communities, in which school personnel come together to code conversations they have had with teachers, parents, or adolescents and to discuss the successes and challenges of implementation. The workshop topics, which are derived from the four MI processes described by Miller and Rollnick (2012), cover the following topics:

Figure 1.

Motivational Interviewing Training and Assessment System for School-Based Applications

Introduction to MI;

OARS and Values;

Focusing and Evoking;

Exchanging Information, Sustain Talk, Discord and Evoking Confidence; and

Planning for Change.

During the workshops, several didactic and interactive teaching methods are used, including lectures, discussions of key concepts, modeling (through video and live demonstration), and role playing. Workshops are available in one-hour, six-hour, and 15-hour options. A summary of the guiding principles and objectives of MI workshops is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

MITAS Guiding Principles and Workshop Objectives

| I. Introduction to MI |

| Guiding Principles |

|

| Objectives |

|

| II. OARS and Values |

| Guiding Principle |

|

| Objectives |

|

| III. Evoking and Focusing |

| Guiding Principles |

|

| Objectives |

|

| IV. Exchanging Information, Sustain Talk & Discord, Evoking Confidence |

| Guiding Principle |

|

| Objectives |

|

| V. Planning for Change |

| Guiding Principle |

|

| Objectives |

|

Prior to the in vivo coaching feedback sessions, school personnel audio record a 20-minute conversation with teachers, parents, or adolescents during which they use MI in support of the participant’s consideration of behavior change. An MI expert evaluates the recording and then provides performance feedback via a 30-minute coaching session. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) Code 4.0 (Moyers et al., 2014), described in the next section, is used to code the session and provide data that can be used for individualized feedback to participants using the Elicit-Provide-Elicit framework (E-P-E; Miller & Rollnick, 2012). The E-P-E approach is a strategy to provide feedback, and also to promote reflection. Specifically, the facilitator begins the coaching session by eliciting the participant’s perception of the audio recording, providing a limited amount of data from the coding (e.g., ratio of open-ended questions to close-ended questions), and then elicits the participant’s reaction to the data. Thus, the MITI data provide a structure through which the MI expert can analyze the recording and provide performance feedback. During the professional learning communities, school personnel bring in audio recordings of their use of MI in conversations about behavior change with teachers, parents, and adolescents. During these meetings, they code audio recordings using the MITI and discuss the successes and challenges of implementation. The professional learning communities start with support from an MI expert, which is faded as learning communities gain confidence with their coding skills. As indicated in this description, tools that can be used to measure competency in MI are necessary to evaluate the efficacy of the training component of the MITAS.

The MITAS Assessment Component

The MITAS assessment component contains measures to determine engagement and satisfaction, MI competency, MI proficiency, self-efficacy, and perceived proficiency.

Engagement and Satisfaction

The facilitator’s checklist requires facilitators to indicate which training components the participant attended and to assess the participant’s engagement in the learning process. The six engagement items are rated on a five-point Likert scale. Facilitators report on each participant’s engagement in the training by responding to five items assessing:

Attentiveness during training sessions;

Responsiveness to comments during feedback sessions;

Overall motivation to participate;

Willingness to ask questions; and

Willingness to try new techniques.

The MITAS satisfaction survey consists of 17 items, scored on a five-point scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. Items examine participants’ perceptions of program usability, effectiveness, and value based on impact within the school setting for the five workshops (overall satisfaction; nine items) and the feedback sessions (eight items).

MI Competency

We used recommended steps for scale development from McCoach et al., (2013) and DeVellis (2011) to identify and adapt two assessment measures to evaluate MI competency. These steps include (1) conceptual definition and literature review, (2) pre-test, (3) expert panel review, and (4) pilot test (see Small et al., 2014). Following the conceptual definition and literature review, we identified the Helpful Response Questionnaire (HRQ; Miller et al., 1991) and the Video Assessment of Simulated Encounters-Revised (VASE-R; Rosengren et al., 2008) as promising measures for adaptation in the context of school-based intervention practice and research.

The Written Assessment of Simulated Encounters-School Based Applications (WASE-SBA; Lee, Small & Frey, 2013), formerly the HRQ, measures a person’s ability to generate reflective responses and is scored by rating each response on five-point scale, with a rating of 1 being indicative of weak reflective practice containing MI-non-adherence skills, 3 being indicative of simple reflective practice, and 5 being indicative of complex reflective practice that infers potential parent, teacher, or adolescent behavior change. The scores for each of the six responses can be combined to reflect the overall level or degree of reflective practice across the measure. The WASE-SBA contains directions, item stems and prompts, a scoring guide, and a scoring form.

The Video Assessment of Simulated Encounters-3-School Based Applications (VASE-3; Lee, Frey & Small, 2013) is a modified version of the VASE-R (Rosengren et al., 2008). The VASE-3 uses three video-recorded vignettes with eight opportunities to respond in each vignette (24 items total). Respondents are prompted to generate written responses consistent with the MI skills. The measure contains four subscales: open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries. All responses are rated on a three-point scale with 1 reflecting responses of Elicits/Reinforces Sustain Talk or Engenders Discord, 2 reflecting responses that were neutral, and 3 reflecting responses of Elicits/Reinforces Change Talk. Subscale scores are derived for each skill, as is a total score from the sum of the subscale scores. The VASE-3 also contains directions, item stems and prompts, a scoring guide, and a scoring form.

MI Proficiency

The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code (MITI 4.0) evaluates component processes within motivational MI, including engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning (Moyers et al., 2014). Sessions without a specific change target or goal may not be appropriate for evaluation with the MITI, although some of the elements may be useful for evaluating and giving feedback about engaging skills. The MITI has two components: the global scores and the behavior counts. According to Moyers and colleagues (2016), interrater reliability based on interclass correlations (ICC) ranged from 0.77 to 0.86 for global ratings, from 0.58 to 0.88 for behavior counts, and from 0.53 to 0.92 for MITI summary measures.

Motivational Interviewing Self-Efficacy

Young (2010) developed the MI Knowledge Questionnaire (MIQ) to assess counselor trainees’ understanding of the basic ideas and principles of MI and their feelings of proficiency in their ability to use MI in practice. The original MIQ consists of 12 questions that participants respond to using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Our adapted version of the questionnaire uses the seven items that assess respondent’s perceived ability to use MI.

Perceived Proficiency

The Measure of Perceived Proficiency (MOPP) consists of 10 items assessing a participant’s perceived proficiency at implementing MI-specific skills. The MOPP assesses 10 MI-specific skills explicitly taught during workshops and reinforced during individualized feedback sessions with participants. Items are scaled on a five-point rating scale ranging from 1 (I am not highly competent at doing this) to 5 (I am highly competent at doing this). The measure is collected from participants and the coach (who will report the participant’s level of proficiency) and triangulated with observation data (i.e., MITI) to facilitate identification of gaps between a participant’s perceived and actual proficiency, identify points of agreement between perceived proficiency and skill level, and encourage self-reflection.

The training and assessment components of the MITAS were based on the extensive available MI literature and a modification of currently available tools so that they are applicable in schools. In order to determine if the MITAS is useful for training school personnel to use MI to enhance intervention fidelity, we employed a single group, pre-/post-test design to assess the feasibility of and satisfaction with the MITAS. Research questions were:

To what extent will participants engage and participate in the MITAS training component?

To what extent is the training potentially efficacious for improving MI skill?

Do participants perceive the training to be socially valid?

Study Sample

Early childhood support staff, who regularly consult with parents and teachers within a large, urban early childhood program in the Midwest were recruited during a 30-minute overview presentation of the study. Of the 35 support staff who were invited to participate, 15 consented and 12 completed the training. The mean age of the 12 participants was 48 (SD = 9.0). Eleven participants were female, three were African-American, and nine were Caucasian. Six participants had earned master’s degrees in education, counseling, or social work. The participants represented the following job titles: curriculum resource teacher (N = 3), disability liaison (N = 3), special education resource teacher (N = 3), and social worker (N = 3). They had an average of 9.1 (SD = 10.6) years of experience in their current position, had been teaching on average 14.6 (SD = 9.4) years, and all were former classroom teachers. None of the participants reported having had any prior training or exposure to MI.

Study Procedures

The study participants attended five three-hour workshops and completed and received performance feedback on audio recordings of their practice of MI in consultation with teachers or parents, as described in the training component section. Facilitators led the workshops and provided individualized feedback to the participants through coaching sessions. The first two authors of this manuscript served as two of the facilitators.

Study Measures

We used adapted versions of the HRQ and VASE-R for this pilot study. The pilot study was completed before the description of the MITAS was finalized for this manuscript. These pilot data were used to make subsequent changes to the study measures, which included renaming the WASE and the VASE-3, as described above. The adapted version of the HRQ consisted of six written paragraphs that simulate conversations with teachers who have specific concerns. After each paragraph, the participant was asked to write a helpful response. Responses were scored on a five-point ordinal scale, rating the nature and quality of the coach’s use of client-centered counseling techniques (i.e., open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries). The original HRQ has high interrater agreement (Martino et al., 2006). Prior to the study, we modified this instrument by creating vignettes that were judged relevant to school-based support staff, and we also modified the scoring criteria (see Small et al., 2014). We collected a version of the VASE-R (as modified from Rosengren et al., 2008) adapted for use with school-based personnel that utilizes three video-recorded portrayals of two teachers and a parent commenting on specific concerns. Coaches were prompted to identify or generate written responses consistent with particular MI principles. The VASE-R includes 18 items (six per vignette) that produce a total score and five subscale scores (i.e., Reflective Listening, Responding to Resistance, Summarizing, Eliciting Change Talk, and Developing Discrepancy). Participant responses were coded using a three-point system, with response options including 0 (Confrontational or Likely to Engender Resistance), 1 (Neutral or Inaccurately Represents the Content of the Client’s Speech), and 2 (Accurately Reflects the Content of the Client’s Speech).

Data Collection and Statistical Analyses

At baseline, participants completed the adapted HRQ and VASE-R. Following the last workshop, the participants again completed the HRQ and VASE-R. Additionally, the facilitators completed the facilitator’s checklist, and participants completed the MITAS satisfaction survey. For interrater reliability, we calculated intra-class correlations (ICC) using two-way mixed effects models (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979). We used Cicchetti’s (1994) recommendations to assess ICC sufficiency. We examined within-subject effects for the HRQ and VASE-R in an analysis of variance (ANOVA) framework using the general linear model (GLM) procedure in SPSS 19. We report partial point-biserial r as a measure of effect size (Rosnow & Rosenthal, 2008). Effect sizes of 0.14, 0.36, and 0.51 are considered small, medium, and large, respectively, for the derived partial r (Cohen, 1988). Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate social validity.

Study Results

Our first research question addressed participants’ engagement in the training component of the MITAS. We answered this question using a facilitator checklist. On average, participants attended 4.8 (SD = 0.4) of the workshops. Ten of 12 participants attended all five workshops. The remaining two participants participated in four of five workshops. All participants attended workshop sessions two through four. Overall, participants attended an average of 2.7 (SD = 0.5) coaching sessions.

Workshop facilitators assessed each participant’s engagement in the MITAS using the facilitators’ checklist. We computed a mean rating across the six items with higher scores indicating higher levels of engagement. The mean engagement rating (five-point Likert scale) was 4.40 (SD = 0.4).

The second research question addressed the efficacy of the MITAS training procedures. The coefficient alpha for the HRQ across the two raters was 0.71 and 0.76; for the VASE-R scale, coefficient alpha was 0.81 and 0.77. HRQ item level, intra-class correlations were all in the acceptable range (i.e., ICC > 0.40). Interrater reliability was lowest for items one and two (ICCs = 0.58 and 0.54, respectively), with considerably higher ICCs for the remaining four items (mean ICC = 0.90; range = 0.82–0.95). For the HRQ total score, interrater reliability was excellent (ICC = 0.92). ICCs for the VASE-R subscales ranged from 0.79 for the Change Talk subscale to 0.99 for the Reflective Listening and Developing Discrepancy subscales. The intra-class correlation for the VASE-R total score was 0.99. VASE-R total scores and HRQ total scores were highly correlated (r = 0.89).

Participants’ scores from pre-test to post-test on both measures are shown in Table 2. Total HRQ scores increased from 9.0 (SD = 3.0) to 18.3 (SD = 3.2). The gains ranged from +2 to +15 on the HRQ and from +5 to +18 on the VASE-R. All participants improved from baseline to post-test. The within-subject partial r effect size was 0.92 (large). The average ICC at the item level was 0.79 (range = 0.54 to 0.95). All 10 participants who completed baseline and post-test VASE-R assessments improved on this measure; specifically, the total mean VASE-R scores increased from 14.60 (SD = 6.6) at baseline to 23.10 (SD = 5.0) at post-test, with a within-subject partial r effect size of 0.90 (large). In addition to examining the overall VASE-R scores, we also examined the subscale scores. As can be seen in Table 3, the largest effect sizes were obtained in the Reflective Listening (0.88), Responding to Resistance (0.80), and Summaries (0.80) subscales. Minimal changes were noted in the Developing Discrepancy (0.07) and Affirmations (0.07) subscales. The ICCs for the VASE-R ranged from 0.79 to 0.99 across the subscales.

Table 2.

Outcome Summary by Participant

| HRQ | VASE-R | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CID | Pre M(SD) | Post M(SD) | Pre-Post Change | Pre Raw Score | Post Raw Score | Pre/-Post Change |

| 101 | 14 | 21 | +7 | — | 33 | — |

| 102 | 6 | 16 | +10 | 10 | 24 | +14 |

| 103 | 13 | 22 | +3 | 24 | 29 | +5 |

| 201 | 9 | 16 | +7 | 12 | 17 | +5 |

| 202 | 6 | 19 | +13 | 7 | 14 | +7 |

| 203 | 6 | 21 | +15 | 11 | 19 | +8 |

| 301 | 10 | 12 | +2 | 11 | 22 | +11 |

| 302 | 6 | 16 | +10 | 10 | 24 | +14 |

| 303 | 9 | 21 | +12 | 17 | 27 | +10 |

| 401 | 7 | 18 | +11 | 7 | — | — |

| 402 | 9 | 22 | +13 | 17 | 28 | +11 |

| 403 | 13 | 16 | +3 | 27 | 27 | 0 |

| Total/Mean | 9.0 (3.0) | 18.3 (3.2) | 14.60 (6.6) | 23.10 (5.0) | ||

Table 3.

Mean Baseline and Post-VASE-R Subscale and Total Scores and Effect Sizes

| Baseline M (SD) | Post M (SD) | F | P-Value | rpart | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 14.6 (6.6) | 23.1 (5.0) | 37.26 | < 0.001 | 0.90 |

| Reflective listening | 2.0 (2.1) | 5.0 (1.4) | 31.15 | < 0.001 | 0.88 |

| Responding to resistance | 2.7 (2.5) | 5.4 (1.8) | 15.58 | 0.003 | 0.80 |

| Summaries | 1.5 (1.7) | 3.3 (1.2) | 16.57 | 0.003 | 0.80 |

| Eliciting change talk | 2.0 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.6) | 3.27 | 0.104 | 0.52 |

| Developing discrepancy | 3.4 (1.5) | 3.5 (1.2) | 0.04 | 0.847 | 0.07 |

| Affirmations | 3.0 (1.7) | 3.1 (1.4) | 0.04 | 0.840 | 0.07 |

The third research question addressed the workshops and the coaching sessions using participant ratings of satisfaction. The satisfaction mean rating for the workshops was 4.6 (SD = 0.4), with scores ranging from 3.9 to 5.0; the mean rating for the feedback sessions (also a five-point Likert scale) was 4.7 (SD = 0.5), ranging from 3.5 to 5.0.

Discussion

We have been encouraged with the successful infusion of MI into school-based practices. Few studies to date, however, have trained school-based personnel to use MI skillfully or have measured their MI proficiency as a component of implementation fidelity within the context of intervention research. The ability to evaluate MI quality, and to eventually scale up MI efforts, will depend on the emergence of training and assessment infrastructures supporting skill acquisition and maintenance. We have reported here a small but important step in developing MI staff training methods and measures that preliminary data suggest may be feasible, sustainable, effective, and perceived as needed by school professionals.

This feasibility study is the fourth attempt that we know of to train school personnel to use an MI approach (Burke et al., 2005; Caldwell & Kaye, 2014; Frey, Walker et al., 2013). Our results indicate that the participants attended a majority of the MITAS training sessions (e.g., workshops and feedback sessions) and that the facilitators rated these MI participants’ engagement as high. This is noteworthy, given the amount of time required to participate fully in the MI training coupled with the very busy schedules maintained by most school personnel. Because participation was voluntary, the high level of participation suggests that learning these skills was important to the participants. Also noteworthy are the encouraging skill gains they showed from pre- to post-test, a result suggesting that the training component of the MITAS is potentially efficacious. These results must be interpreted with caution, however, due to the small sample size and failure to control for threats to internal validity in this study.

The MITAS provides a framework for the promising transfer of MI from substance abuse and health settings to school-based applications. It is our hope that this framework will help facilitate the interpretation of school-based MI research and also help to answer the critical questions Herman and colleagues (2014) posed:

How much training, supervision, and practice are required to improve one’s MI proficiency?

What level of competency is sufficient to affect teacher, parent, or adolescent behavior change?

What standards should be used to evaluate MI competency?

We believe all researchers using MI as a component of their intervention framework should include MI fidelity assessment as a process measure. The MITAS provides a readily available and flexible framework for training and assessing MI competency and proficiency.

Future research should examine the efficacy of the MITAS by employing designs that control for threats to internal validity. Additionally, future research should use all the measures contained in the MITAS in the assessment component. Finally, it will eventually be important to demonstrate that changes in the behavior of school personnel are associated with positive changes in teacher, parent, or adolescent behavior.

Acknowledgments

An Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education grant (R324A090237) to the University of Louisville was utilized as partial support for the development of this article. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education. The authors would also like to thank their partners in the early childhood program in the Jefferson County Public School (Louisville, KY) system.

Contributor Information

Andy J. Frey, Professor in the University of Louisville’s Kent School of Social Work

Jon Lee, Assistant professor in the University of Cincinnati’s School of Education

Jason W. Small, Data analyst at the Oregon Research Institute, in Eugene.

Hill M. Walker, Professor of special education in the University of Oregon’s College of Education and director of the university’s Center on Human Development

John R. Seeley, Professor in the Special Education and Clinical Sciences Department at the University of Oregon’s College of Education

References

- Aubrey LL. Motivational Interviewing with Adolescents Presenting for Outpatient Substance Abuse Treatment. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Domitrovich CE. The conceptualization, integration, and support of evidence-based interventions in the schools. School Psychology Review. 2011;40:582–589. [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Miller WR, Boroughs JM. Motivational interviewing with alcohol outpatients. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1993;21:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Miller WR. Impact of motivational interviewing on participation and outcome in residential alcoholism treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1993;7:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Burke PJ, Da Silva JD, Vaughan BL, Knight JR. Training high school counselors on the use of motivational interviewing to screen for substance abuse. Substance Abuse. 2005;26:31–34. doi: 10.1300/j465v26n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell S, Kaye S. Training student services staff in motivational interviewing. In: McNamara E, editor. Motivational Interviewing: Children and Young People II: Issues and Further Applications. United Kingdom: Positive Behaviour Management; 2014. pp. 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Special section: Normative assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Bullock B, Dishion T, Shaw D, Wilson M, Gardner F. Family intervention effects on co-occurring early childhood behavioral and emotional problems: A latent transition analysis approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1211–1225. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis RF. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family checkup with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA. Intervening in Children’s Lives: An Ecological, Family-Centered Approach to Mental Health Care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Siler C. An ecological approach to interventions with high-risk students in schools: Using the Family Check-Up to motivate parents’ positive behavior support. In: Shinn MR, Walker HM, editors. Interventions for Achievement and Behavior Problems in a Three-Tier Model Including RTI. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists; 2010. pp. 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Frey AJ, Cloud RN, Lee J, Small JW, Seeley JR, Feil EG, Walker HM, Golly A. The promise of motivational interviewing in school mental health. School Mental Health. 2011;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Frey AJ, Lee J, Small JW, Seeley JR, Walker HM, Feil EG. Transporting motivational interviewing to school settings to improve engagement and fidelity of tier 2 interventions. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2013;29:183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Frey AJ, Small JW, Lee J, Walker HM, Seeley JR, Feil EG, Golly A. Expanding the range of the First Step to Success intervention: Tertiary-level support for teachers and families. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Frey AJ, Walker HM, Seeley J, Lee J, Small J, Golly A, Feil E. Tertiary First Step to Success Resource Manual. 2013 Available at http://first-steptosuccess.org/Tertiary%20First%20Step%20to%20Success%20Resource%20Manual.pdf.

- Gardner F, Connell A, Trentacosta C, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson M. Moderators of outcome in a brief family-centered intervention for preventing early problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:543–553. doi: 10.1037/a0015622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B, Beadnell B, Rosengreen DB, Dunn C, Baer JS. Deconstructing proficiency in motivational interviewing: Mechanics of skillful practitioner delivery during brief simulated encounters. Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38:611–628. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman K, Reinke W, Frey AJ, Shepard S. Motivational Interviewing in Schools: Strategies to Engage Parents, Teacher, and Students. New York: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Frey AJ, Reinke WM, Herman KC. Motivational interviewing as a framework to guide school-based coaching. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 2014;7:225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Frey AJ, Small JW. The Video Assessment of Simulated Encounters—School-Based Applications. Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Frey AJ, Walker HM, Golly A, Seeley J, Small J, et al. Adapting motivational interviewing to an early intervention addressing challenging behavior: Applications with teachers. In: McNamera E, editor. Motivational Interviewing with Children and Young People: Issues and Further Applications. United Kingdom: Positive Behaviour Management; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Small JW, Frey AJ. Written Assessment of Simulated Encounters—School-Based Application. Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer E, Shaw D, Gardner F, Dishion T, Connell A, Wilson M. Collateral benefits of the family check-up on early childhood school readiness: Indirect effects of parents’ positive behavior support. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1737–1752. doi: 10.1037/a0013858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Gallon SL, Hall D, Garcia M, Ceperich S, Farentinos C, Hamilton J, Hausotter W. Motivational Interviewing Assessment: Supervisory Tools for Enhancing Proficiency. Salem, OR: Northwest Addiction Technology Transfer Center, Oregon Health and Science University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McCoach BD, Gable RK, Madura JP. Instrument Development in the Affective Domain. 3. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Hedrick KE, Orlofsky DR. The Helpful Responses Questionnaire: A procedure for measuring therapeutic empathy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991;47:444–448. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199105)47:3<444::aid-jclp2270470320>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Moyers T. Eight stages in learning motivational interviewing. Journal of Teaching in the Addictions. 2006;5:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick SR. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (Applications of Motivational Interviewing) 3. New York: Guilford; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Manuel JK, Ernst D. Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Coding Manual 4.0. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.001. Unpublished manual. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Rowell LN, Manuel JK, Ernst D, Houck JM. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code (MITI 4): Rationale, preliminary reliability and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2016;65:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke WM, Frey AJ, Herman KC, Thompson C. Improving engagement and implementation of interventions for children with behavior problems in home and school settings. In: Walker H, Gresham F, editors. Handbook of Evidence-Based Practices for Students Having Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke WM, Herman KC, Darney D, Pitchford J, Becker K, Domitrovich C, Ialongo Using the Classroom Check-Up to support implementation of PATHS to PAX. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 2012;5:220–232. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke WM, Herman KC, Sprick R. Motivational Interviewing for Effective Classroom Management: The Classroom Check-Up. New York: Guilford; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke W, Lewis-Palmer T, Merrell K. The Classroom Check-Up: A classwide teacher consultation model for increasing praise and decreasing disruptive behavior. School Psychology Review. 2008;37:315–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren DB, Hartzler B, Baer JS, Wells EA, Dunn CW. The Video Assessment of Simulated Encounters-Revised (VASE-R): Reliability and validity of a revised measure of motivational interviewing skills. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow RL, Rosenthal R. Assessing the effect size of outcome research. In: Nezu AM, Nezu CM, editors. Evidence-Based Outcome Research: A Practical Guide to Conducting Randomized Controlled Trials for Psychosocial Interventions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 379–404. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J, Aashland O, Babor T, De La Fuente J, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Identification Disorders Test (AUDIT): World Health Organization: Collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Ands K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the Family-Check-Up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intra-class correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small JW, Lee J, Frey AJ, Seeley JR, Walker HM. The development of instruments to measure motivational interviewing skill acquisition for school-based personnel. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 2014;7:240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN. Indirect effects of fidelity to the Family Check-Up on changes in parenting and early childhood problem behaviors. Journal of Consultation and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:962–974. doi: 10.1037/a0033950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strait GG, Smith BH, McQuillin S, Terry J, Swan S, Malone PS. A randomized trial of motivational interviewing to improve middle school students’ academic performance. Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;40:1032–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Terry J, Smith B, Strait G, McQuillin S. Motivational interviewing to improve middle school student’ academic performance: A replication study. Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;41:902–909. [Google Scholar]

- Young T. PhD diss. University of Central Florida; Orlando: 2010. The effect of a brief training in motivational interviewing on client outcomes and counselor skill development. Available at http://etd.fcla.edu/CF/CFE0003054/Young_Tabitha_L_201005_PhD.pdf. [Google Scholar]