Abstract

Two new ruthenium complexes, [Ru(η5-Cp)(PPh3)(2,2’-bipy-4,4’-R)]+ with R = CH2OH (Ru1) or dibiotin ester (Ru2) were synthesized and fully characterized. Both compounds were tested against two types of breast cancer cells (MCF7 and MDA-MB231), showing better cytotoxicity than cisplatin in the same experimental conditions. Since multidrug resistance (MDR) is one of the main problems in cancer chemotherapy, we have assessed the potential of these compounds to overcome resistance to treatments. Ru2 showed exceptional selectivity as P-gp inhibitor, while Ru1 is possibly a substrate. In vivo studies in zebrafish showed that Ru2 is well tolerated up to 1.17 mg/L, presenting a LC50 of 5.73 mg/L at 5 days post fertilization.

Keywords: Ruthenium organometallic compounds, anticancer agents, P-gp inhibitor, multidrug resistance

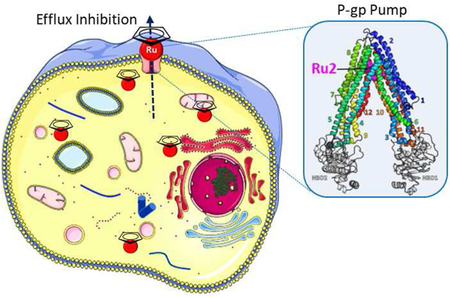

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

A major concern regarding chemotherapy, the first line treatment for many cancers, is the development of drug resistant phenotypes that considerably limit the efficiency of the drugs. Drug resistance might be either inherent (i.e. at the first treatment) or acquired (i.e. after subsequent treatments). In fact, multidrug resistance (MDR) is one of the major clinical obstacles in cancer chemotherapy, being responsible for more than 90 % of treatment failures of metastatic cancer using adjuvant chemotherapy.[1] One of the most common MDR mechanisms is the overexpression of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily transporters, which mediate the efflux of anticancer drugs thus lowering their intracellular concentrations under effective amounts. Among these ABC transporters the P-glycoprotein (P-gp, ABCB1), Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP, ABCG2), Multidrug Resistance Protein 1 (MRP1, ABCC1) and Multidrug Resistance Protein 2 (MRP1, ABCC2) have been reported to play important roles in inducing MDR in several cancers, such as lung, breast, colon, ovarian cancers and melanomas.

P-gp is one of the most studied pumps as a drug target for the treatment of multidrug resistant cancers. Some studies have shown that modifications on the structure of known anticancer compounds, such as anthracyclines and taxanes confer the ability to overcome P-gp transport.[2] Despite promising in vitro results claiming new strategies to overcome the MDR issue, clinical trials remain disappointing.[3,4] A recent approach is the development of anticancer agents that would also behave as MDR inhibitors. For example, a series of aminated thioxanthones were tested for in vitro activity as antitumor agents and P-gp inhibitors.[5] The overall results, highlighted two compounds (1-[2-(1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)ethanamine]-4-propoxy-9H-thioxanthen-9-one and 1-{[2(4-nitrophenyl)ethyl]amino}−4-propoxy-9H-thioxanthen-9-one) with a dual action as Pgp inhibitors and cytotoxic agents.[5]

During the last decade we have been developing new [RuCpR(PPh3)(bipyridine-R’)]+ (CpR = η5-C5H5 or η5-C5H4(CH3), R’ = -H, -CH3, -CH2OH, - OC3H6-C8F17) compounds as anticancer agents.[6–13] These compounds are highly cytotoxic against a wide panel of cancer cell lines with different degrees of aggressiveness, stable under physiologic conditions and their cell uptake and cellular distribution is dependent on the substituents of the bipyridine ligand. Recently we tested some of those compounds bearing 2,2’bipyridine-4,4’-subtituints as MDR inhibitors.[7] The overall results showed that the compounds bearing the bipyridines with -H and -CH2OH substituents were poor substrates to the main MDR human pumps, while the bipyridine with -CH3 as substituent displayed inhibitory properties for MRP1 and MRP2 pumps. All compounds showed very good cytotoxicity for ovarian cancer cells (sensitive and resistant) with IC50 values surpassing up to 120 times those of cisplatin in the same experimental conditions.

In this paper, the effect of the addition of biotin, vitamin B7, to the [Ru(η5C5H5)(PPh3)(bipyridine-R)]+ scaffold (R = -CH2OH, Ru1 or dibiotin ester, Ru2) is explored in terms of MDR potential. Indeed, several compounds with anticancer activity have been functionalized with biotin to improve their efficiency and efficacy.[14] The new biotinylated compound toxicity was also evaluated using a modified embryo larval zebra fish model (OECD. 2013).

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and characterization of Ruthenium compounds

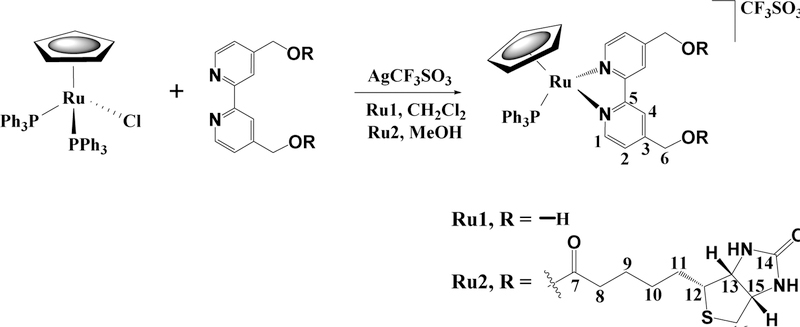

Mononuclear cationic complexes of the general formula [Ru(η5-Cp)(PPh3)(2,2’-bipy4,4’-R)]+ with R = -CH2OH (Ru1) or dibiotin ester (Ru2),were prepared, as shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route of the new Ru(II) complexes; all compounds are numbered for NMR assignments Ru1, Ru2.

Sigma coordination of bidentate N,N chelating 2,2’-bipy-4,4’-R ligand to ruthenium was achieved in good yields by halide abstraction from the starting material [Ru(η5Cp)(PPh3)2Cl] using silver triflate. Purification of the organometallic complexes was achieved by slow diffusion recrystallization from dichloromethane/n-hexane and THF/n-hexane. The formulation and purity of the new complexes and of the dibiotin ester are supported by FT-IR, UV-vis and 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectroscopic data and elemental analyses.

The dibiotin ester was synthesized following a slightly modified literature protocol.[15] Instead of using the N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) as a coupling agent for the esterification reaction, a different approach using N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) was tested. In fact, the main problem with DCC is the formation of a water insoluble urea byproduct very difficult to be eliminated. This alternative synthesis is done in a one-pot reaction, avoids the use of high temperatures and longtime reactions and allows a simpler purification of the final product.

The esterification reaction between 4,4´-dihydroxymethyl-2,2´-bipyridine and biotin was followed by 1H-NMR spectroscopy. An evident deshielding of H6 protons has occurred as expected due to the presence of oxygen atoms from the ester and the signal multiplicity also changed from duplet to singlet. Both signals from the -OH of the alcohol and carboxylic acid of the biotin have disappeared, confirming the successful esterification.

The FT-IR spectra of the dibiotin ester also confirms a successful esterification by the typical stretching frequency for the υ (C=O) of the ester at 1732 cm−1.

The analysis of the solid-state FT-IR spectra of the organometallic rutheniumcyclopentadienyl derivatives Ru1 and Ru2 shows the presence of the typical bands expected for υCH stretching of the bipyridine, phosphane and cyclopentadienyl ligands in the range 3080–3060 cm−1 as well as the bands for υC=C at 1600–1400 cm−1. The presence of the triflate counterion was revealed in the typical range for this group (~1240 cm−1), which agrees with the cationic character of the compounds. The hydroxyl groups of the bpy(CH2OH) were also found at 3410 cm−1 for Ru1.

Analysis of the overall 1H NMR spectra shows a general deshielding of the η5-C5H5 protons upon coordination of the bipyridine-based ligands, as expected for a cationic species. The bipyridine protons show a deshielding on the ortho protons (~0.6 ppm) and a shielding on the meta protons (−0.5 ppm and −0.3 ppm, for Ru1 and Ru2, respectively), giving evidence of successful coordination of the bipyridyl derivative to the metal center. The results are in accordance with the previous discussed effects in the 1H NMR analysis. All the detailed spectroscopic data concerning the 13C NMR experiments are in the experimental section. The 31P NMR spectra showed a single sharp singlet resonance corresponding to the coordinated phosphane co-ligand (~ 51 ppm). A deshielding behavior upon coordination was expected as it is in accordance with its σ donor character.

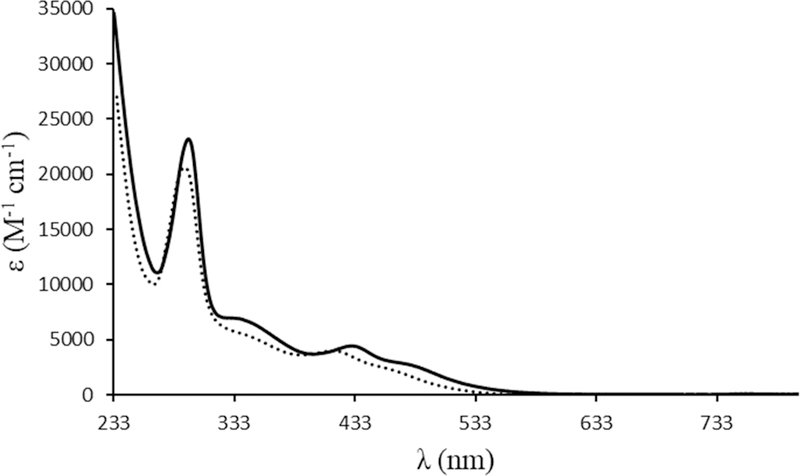

The electronic spectra of both complexes and the bipyridine ligands were recorded in 10−5-10−3 M dichloromethane solutions. Figure 1 presents the electronic spectra of both compounds. In addition to the strong absorption bands, characteristic of each bipyridyl derivative and the {[Ru(Cp)(PPh3)]+} organometallic fragment (appearing below 300 nm), the electronic spectra of these compounds were characterized essentially by one broad, medium-strength, absorption band with a shoulder in the visible region (400 – 600 nm) with εmax ~ 4 × 103 M−1 cm−1 that can be related to metal-to-ligand charge transfer bands (MLCT), from Ru 4d to π* N-heteroaromatic rings and to phosphane, as previously reported for related compounds.[7]

Figure 1.

Electronic spectra of complexes Ru1 (dashed line) and Ru2 (solid line) in dichloromethane.

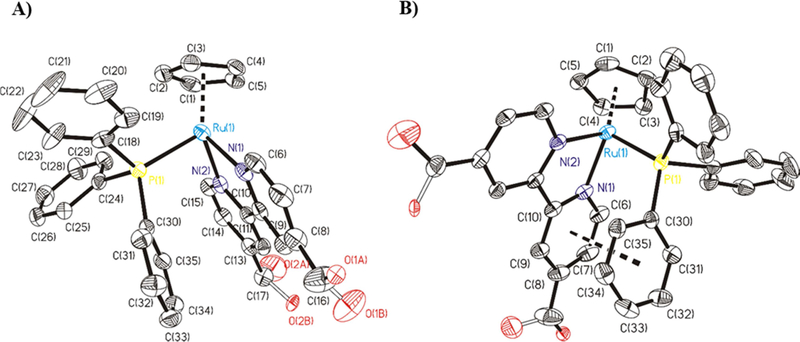

[Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’-diyldimethanol-2,2’-bipyridine)][CF3SO3] Ru1 crystallized from methanol/ether solution as orange prisms (crystal dimensions 0.37 × 0.25 × 0.10 mm). Figure 2A shows an ORTEP representation of [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’diyldimethanol-2,2’-bipyridine)]+ of Ru1. In Ru1, the asymmetric unit contains one cationic ruthenium complex and one CF3SO3- anion. In the molecular structure, the ruthenium center adopts a “piano stool” distribution formed by the ruthenium-Cp unit bound to phosphane and to nitrogen atoms of the 4,4’-diyldimethanol-2,2’-bipyridine ligand. One phosphane group occupies the other coordination position. The distance for Ru-P bond is Ru(1)-P(1) = 2.3098(8) Å. The distances for Ru-N bonds are Ru(1)-N(1) 2.087(3) Å and Ru(1)-N(2) 2.080(3) Å. The distance between Ru and the centroid of the π-bonded cyclopentadienyl moiety is 1.8301(1) Å to Ru center (ring slippage 0.033 Å). The mean value of the Ru-C bond distance is 2.1906(30) Å. Table 1 contains selected bond lengths and angles for Ru1. π-π stacking interactions are present in the structure. Comparing it with the already published [RuCp(2,2’-bipyridine)PPh3]+ cation,[10] the distance between the bipyridine ligand ring N(1)-C(6)-C(7)-C(8)-C(9)-C(10) and the phosphane phenyl ring C(30)-C(31)-C(32)-C(33)-C(34)-C(35) are similar (3.695(3) Å for Ru1, see Figure 2B, and 3.744(2) Å for [RuCp(2,2’-bipyridine)PPh3]+).

Figure 2.

A) ORTEP for the cation complex [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’-diyldimethanol2,2’-bipyridine)]+ of Ru1. All the non-hydrogen atoms are presented by their 50% probability ellipsoids. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity; B) ORTEP for the cation complex [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’-diyldimethanol-2,2’-bipyridine)]+ of Ru1 where we can see π-π stacking interaction between the bipyridine ring and phenyl ring of phosphane. All the non-hygrogen atoms are presented by their 50% probability ellipsoids. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Table 1.

Bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] for [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’-diyldimethanol2,2’-bipyridine)][CF3SO3] Ru1.

| Bond lengths | Ru1 |

|---|---|

| Ru(1)-N(1) | 2.087(3) |

| Ru(1)-N(2) | 2.080(3) |

| Ru(1)-C(1) | 2.175(3) |

| Ru(1)-C(2) | 2.176(3) |

| Ru(1)-C(3) | 2.192(3) |

| Ru(1)-C(4) | 2.202(3) |

| Ru(1)-C(5) | 2.208(3) |

| Ru(1)-P(1) | 2.3098(8) |

| Bond angles | Ru1 |

| N(2)-Ru(1)-N(1) | 76.16(9) |

| N(2)-Ru(1)-C(1) | 101.18(12) |

| N(1)-Ru(1)-C(1) | 153.35(12) |

| N(2)-Ru(1)-C(5) | 99.61(11) |

| N(1)-Ru(1)-C(5) | 115.59(11) |

| C(1)-Ru(1)-C(5) | 38.03(12) |

| N(2)-Ru(1)-C(2) | 133.09(12) |

| N(1)-Ru(1)-C(2) | 150.55(12) |

| C(1)-Ru(1)-C(2) | 37.75(14) |

| C(5)-Ru(1)-C(2) | 63.05(13) |

| N(2)-Ru(1)-C(4) | 129.04(11) |

| N(1)-Ru(1)-C(4) | 97.69(11) |

| C(1)-Ru(1)-C(4) | 62.94(12) |

| C(5)-Ru(1)-C(4) | 37.19(12) |

| C(2)-Ru(1)-C(4) | 62.83(12) |

| N(2)-Ru(1)-C(3) | 162.27(11) |

| N(1)-Ru(1)-C(3) | 113.23(11) |

| C(1)-Ru(1)-C(3) | 63.44(13) |

| C(5)-Ru(1)-C(3) | 62.97(12) |

| C(2)-Ru(1)-C(3) | 37.97(13) |

| C(4)-Ru(1)-C(3) | 37.60(12) |

| N(2)-Ru(1)-P(1) | 92.85(7) |

| N(1)-Ru(1)-P(1) | 90.68(7) |

| C(1)-Ru(1)-P(1) | 115.97(10) |

| C(5)-Ru(1)-P(1) | 152.89(9) |

| C(2)-Ru(1)-P(1) | 90.92(9) |

| C(4)-Ru(1)-P(1) | 138.09(9) |

| C(3)-Ru(1)-P(1) | 101.76(9) |

X-ray structure analysis of Ru1 shows two enantiomers of cation complex [Ru(η5C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’-diyldimethanol-2,2’-bipyridine)]+ of Ru1 in the racemic crystal (space group P 1), the chirality being due to a twist of the PPh3 and Cp units. The cation complex [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’-diyldimethanol-2,2’-bipyridine)]+ of Ru1 presents a mirror plane which contain P, Ru and the centroid of Cp ring (see Figure S1).[11,16] Hydrogen bonds between hydroxy groups and CF3SO3- anions are present in the crystal packing (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Hydrogen bonds in the compound [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’-diyldimethanol2,2’-bipyridine)][CF3SO3] Ru1.

| D-H...A | d(D-H) | d(H...A) | d(D...A) | <(DHA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O(1A)-H(1A)...O(3A)#1 | 0.82 Ǻ | 1.80 Ǻ | 2.350(10) Ǻ | 123.1 º |

| O(1A)-H(1A)...O(2A)#2 | 0.82 Ǻ | 2.30 Ǻ | 2.852(18) Ǻ | 125.3 º |

| O(2A)-H(2A)...O(2A)#3 | 0.82 Ǻ | 1.92 Ǻ | 2.52(2) Ǻ | 128.3 º |

| O(2B)-H(2B)...O(3B)#4 | 0.82 Ǻ | 1.84 Ǻ | 2.725(6) Ǻ | 159.3 º |

Symmetry transformations used to generate equivalent atoms:

#1 -x,-y,-z+1 #2 x,y-1,z #3 -x,-y+2,-z+1 #4 -x,-y+1,-z+1

Stability studies in aqueous media

Stability is a key issue when assessing the biological activity of any metallodrug. Thus, the stability of the compounds was evaluated as the absorbance variation percentage in the cell culture medium DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) containing up to 5% DMSO to allow for the solubilization of the compounds in an adequate concentration for optical electronic spectra. Both compounds are stable under these conditions allowing for their further study in human cancer cells (Figure S2).

Biological Evaluation of the compounds

Cytotoxicity in breast cancer cell lines

The cytotoxicity of the ruthenium complexes Ru1 and Ru2 was studied on two human cancer cell lines with different degrees of aggressiveness (breast MCF7 and MDA-MB-231) using the colorimetric MTT assay. Cells were incubated with each compound, in a concentration range of 1 µM to 100 µM, for a period of 24 hours. Table 3 summarizes the IC50 values obtained.

Table 3.

IC50 (µM) for both ruthenium complexes with a range between 0.1–100 µM, at 24 h incubation, in MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cells.

| MCF7 (µM) | MDA-MB-231 (µM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ru1 | 4.61 ± 0.96 | 13.9 ± 2.8 |

| Ru2 | 31.5 ± 4.7 | 11.6 ± 1.5 |

| Cisplatin | 38 ± 1.41 | 122 ± 25 |

Both compounds are cytotoxic against the two cell lines tested and 2–13 times more cytotoxic than cisplatin under the same experimental conditions. Ru1 is more cytotoxic than Ru2 by ~7-fold for the MCF7 cancer cell line. Both compounds are equally cytotoxic for the MDA-MB-231 cancer cell line.

Effect of Ruthenium compounds on cells overexpressing ABC transporters

One major limitation in chemotherapy is the acquired resistance that cancer cells might develop. Thus, within this work our goals were to examine if ABC pumps are able to pump the compounds out of cells leading to their inefficacy or if Ru1 and Ru2 can act as ABC transporters inhibitors. These proteins are overexpressed in cancer cell lines and allow the efflux of the drug out from the cell. To avoid this efflux, the identification of selective inhibitors that block the drugs efflux is being explored. Table 4 presents the cytotoxic activity of the ruthenium complexes Ru1 and Ru2 for the noncancerous (or “normal”) cell lines. The HEK293 cells were either wild-type (WT, transformed with an empty vector) or transfected with a plasmid containing a gene coding for the transporter proteins: BCRP, MRP1, MRP2. NIH3T3 cells were used in the same way to express the P-gp.

Table 4.

In vitro cytotoxic activity of ruthenium complexes in cell lines transfected with an empty plasmid (HEK293, NIH3T3) or overexpressing ABC transporters (P-gp, MRP1, MRP2, BCRP) after 48 h incubation at 37 °C. Compounds concentration required to inhibit 50% of the cell’s growth (half maximal inhibitory growth concentration or IG50) was measured by MTT assay.

| Half inhibitory growth concentration, IG50 (µM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH3T3╱P-gP | HEK293╱MP1 | HEK293╱MRP2 | HEK293╱BCRP | |

| Rul | 28.1±1.2╱67.8±3.5 | 4.8±0.1╱10±0.4 | 4.5±1.0╱4.9±0.9 | 6.7±0.2╱19.1±0.6 |

| Ru2 | 7.3±0.2╱7.3±0.3 | 1.6±0.9╱1.7±1.2 | 5.7±2.3╱3.0±l.2 | 5.6±2.9╱l.l±0.4 |

Ru1 differentially inhibited the growth of control cells, with IG50 below 7 µM for HEK293 cells and of 28 µM for NIH3T3 cells. The expression of MRP1 or BCRP in HEK293 cells increased the IG50 of Ru1 to 10 and 19 µM, respectively; it also increased to about 70 µM for NIH3T3 cells expressing P-gp, which represents concentrations 2, 2.8 and 2.4 times higher than for the respective non-transfected cells. These results suggest that Ru1 is transported by these pumps, leading to higher resistance profiles. As cancer cells are susceptible to overexpress these ABC transporters, Ru1 may not be considered as a good potential chemotherapeutic agent.

Ru2 showed IG50 between 1 and 6 µM for HEK293 cells without significant differences when MRP1, MRP2 or BCRP are expressed. Ru2 is also much more efficient than Ru1 on NIH3T3 cells with an IG50 of 7 µM, again without any difference when P-gp is expressed. These results make Ru2 a potential chemotherapeutic agent as none of these transporters confers resistance against its cytotoxic action.

Another aim of this study was to determine if Ru1 and Ru2 inhibit the MDR pumps, thus improving their chemotherapy efficiency. We measured by flow cytometry the intracellular accumulation of fluorescent substrates co-incubated with Ru1 or Ru2, in P-gp-, MRP1-, MRP2- or BCRP-transfected cells. Results are displayed in Figure 3. As shown and as expected, Ru1 did not display any inhibition property of the MDR pumps. On the contrary, Ru2 efficiently blocked the efflux of rhodamine 123 mediated by P-gp. This was specific of P-gp as the efflux of other substrates mediated by BCRP, MRP1 or MRP2 were not modified by Ru2.

Figure 3.

Inhibition by Ru1 and Ru2 of MDR pumps substrate efflux. ABCG2, MRP1 and MRP2, NIH 3T3 WT and overexpressing P-gp MDR pumps are expressed as detailed in Table 4. The concentrations used for the reference substrates were: 5 µM of mitoxantrone for ABCG2, 0.5 µM of rhodamine 123 for P-gp, 0.2 µM of calcein AM for MRP1 and MRP2. Ru1 and Ru2 were used at 20 µM. The reference inhibitors, Ko143, GF120918, verapamil and cyclosporine A, were used at 1, 5, 325 and 325 µM, respectively.

Molecular Docking

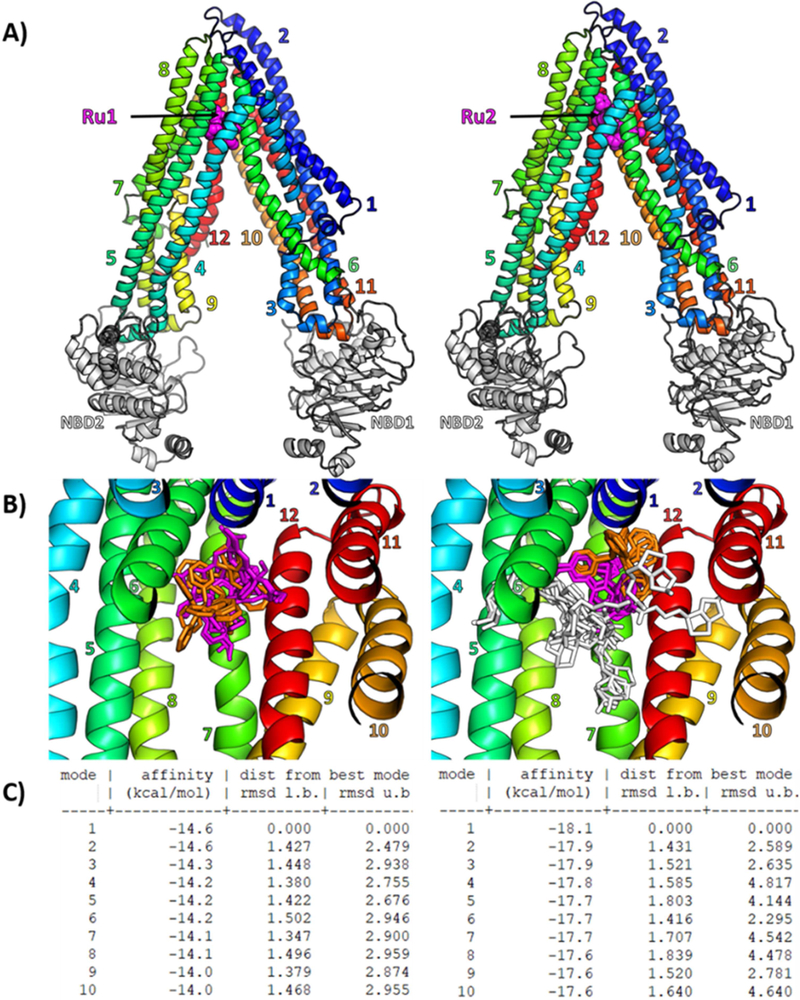

While Ru1 was found to be a substrate of P-gp, interestingly Ru2 was found to be an inhibitor of the same transporter despite similar structure. To better characterize this behavior at the molecular level, we performed flexible molecular docking for both compounds on a human P-gp 3D model generated by us. Fifty-five residues, which form the drug-binding pocket, were made flexible and 10 poses per molecule were generated. Both Ru1 and Ru2 best pose (Figure 4A) dock at the same upper part of the drugbinding pocket. Although it is also true for all other poses (Figure 4B), Ru2 seems much more stabilized as the structures colored in magenta and orange almost share the same position between them, while it is not the case for the common structure in Ru1. The R-group of Ru2 can, however, adopt many positions. As Ru1 has been shown to be a substrate and Ru2 an inhibitor, we hypothesized that Ru1 structure binds into the pocket, induces a conformational change and is transported by P-gp. The addition of long biotin-group allows Ru2 to interact with more residues and prevents any further conformational change of P-gp. This finding is supported by a gain of affinity of −3.5 kcal.mol−1 for Ru2 best pose compared to Ru1, leading to a significantly high theoretical affinity of −18.1 kcal.mol−1 with P-gp (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

(A) Cartoon representation of human P-gp 3D model, based on the mouse Pgp crystallographic structure (PDB 4Q9H), with the best docking pose of Ru1 and Ru2 computed with Autodock Vina in a gridbox containing 55 flexible residues forming the drug-binding pocket. Ru1 and Ru2 are shown as magenta spheres, transmembrane helices are numbered and colored from blue to red, Nucleotide Binding Domains (NBD) are colored in white. (B) Overview of the drug-binding pocket with all 10 flexible docking poses of Ru1 (left panel) and Ru2(right panel) shown as sticks with common core colored in magenta, common PPh3 in orange, and Ru2 additional R-group in white. (C) Docking affinities and RMSD are given for all 10 flexible docking poses (or “modes”) of Ru1 (left panel) and Ru2 (right panel).

In vivo toxicity assessment using zebrafish embryos

The zebrafish has been used as an experimental model to study chemical toxicity since the 1950s. Additionally, this model allows for examining adverse outcome pathways from biochemical to whole organism endpoints, unlike cell culture and more expensive rodent models.

The zebrafish has proven to be a valuable vertebrate model for assessing chemical toxicity and studying chemical mechanisms of toxicity. The zebrafish embryo larval assay (ELA) offers certain advantages over traditional vertebrate models, including rapid generation time, high fecundity, external embryonic development, capacity for high stocking density in relatively small areas, and lower maintenance costs.[18,19] A modified OECD.2013 protocol was used as previously described.[20] The ELA allows establishment of testable hypotheses for evaluating adverse outcome pathways from the subcellular to the organ system level. This makes the zebrafish model ideal for anticancer drug research where one of the objectives is to identify adverse effects of chemical exposure.

Zebrafish embryos were used as a model for the in vivo toxicity evaluation of the most promising compound, Ru2. At 3 hours post fertilization (hpf) eggs were exposed to increasing concentrations of Ru2. The concentrations collected and analytically evaluated at the end of the experiment were determined to be 0.00, 0.15, 0.47, 1.17, 2.18, 3.48, 4.24, 5.12 and 6.57 mg/L. Daily observations of the embryos were recorded and included lethality/survival as well as lesions (such as pericardial sac edema, yolk sac edema, and malformations) were evaluated. The fertilization rate was >80 % and the control survival rate was consistently >90 %.

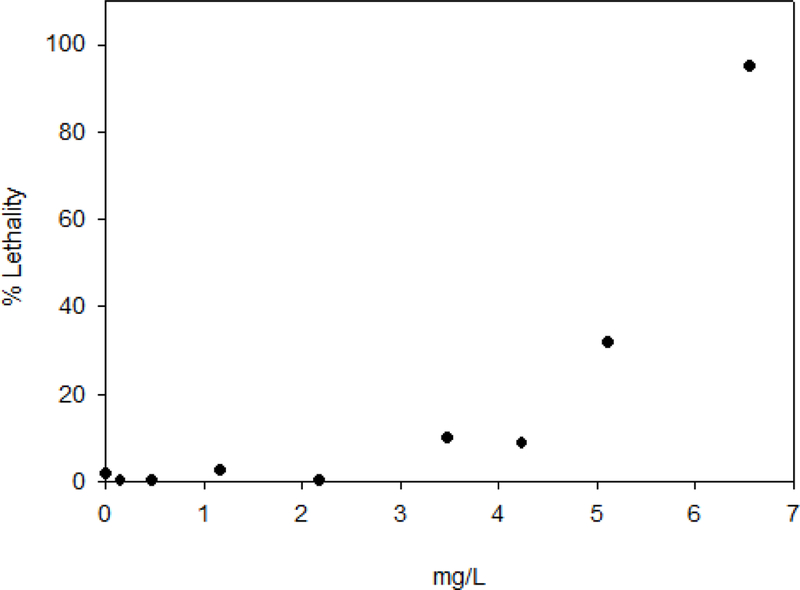

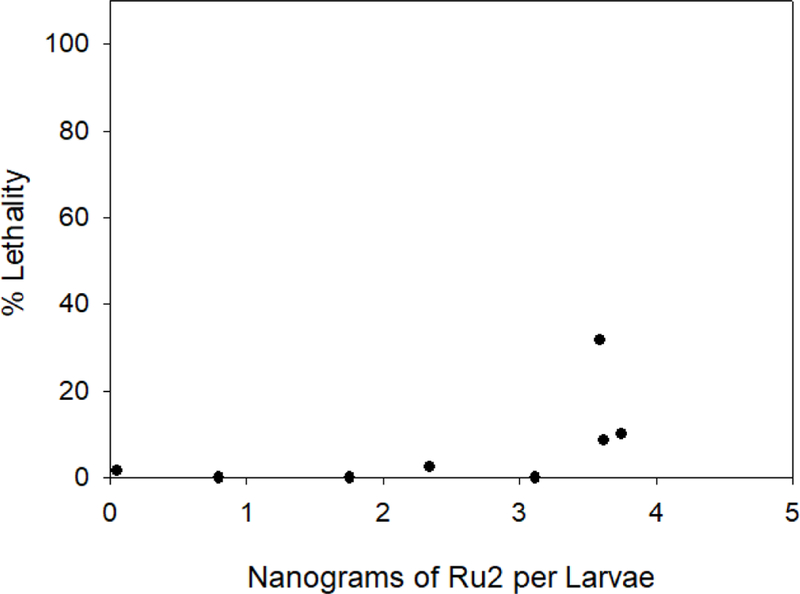

Four acute toxicity endpoints were obtained from the dose response curves: lethality for 50 % of the embryos or larvae - LC50, NOEC – no observed effect concentration, LOEC – lowest observed effect concentration and NOAEL – No observed adverse effect level. (Table 5). It should be noted that the NOAEL is based on the dose of the compound found within the whole tissue of the zebrafish, while the other values were determined from the exposure medium. Graphical representations of the lethality-response curve and the evolution of lethality through time can be seen in Figure 5 and Figure S3, respectively. The lethality-response curve distribution for Ru2 compound (Figure 5) allowed the accurate estimation of the LC50 value. At the end of the 120 hpf experiment, the living larvae were sacrificed, digested with a mixture of nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide and then analyzed by ICP-MS to quantify the ruthenium in ng per larvae, as shown in Table 5 and Figure 6.

Table 5.

Estimates obtained from in vivo toxicity analyses at the end of the 120 hpf experiment.

| LC50 (95% CLa) (mg/L) |

NOEC (mg/L) |

LOEC (mg/L) |

NOAEL (mg/L) |

NOAEL (ng/larvae) |

NOEL (mg/L) |

NOEL (ng/larvae) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru2 | 5.73 (4.74–6.26) | 2.18 | 3.48 | 2.18 | 3.11 | 1.17 | 2.34 |

CL = confidence limits; NOEC - no observed effect concentration; LOEC - lowest observed effect concentration; NOEL – no observed effect level; NOAEL – No observed adverse effect level.

Figure 5.

Lethality-response curve for tested Ru2 compound solutions (ND, 0.15, 0.47, 1.17, 2.18, 3.48, 4.24, 5.12 and 6.57 mg/L). ND: non-detected.

Figure 6.

Lethality-response curve for tested Ru2 compound inside larvae in ng of Ru2/larvae (ND, 0.80, 1.76, 2.34, 3.11, 3.74, 3.61 and 3.59). ND: non-detected.

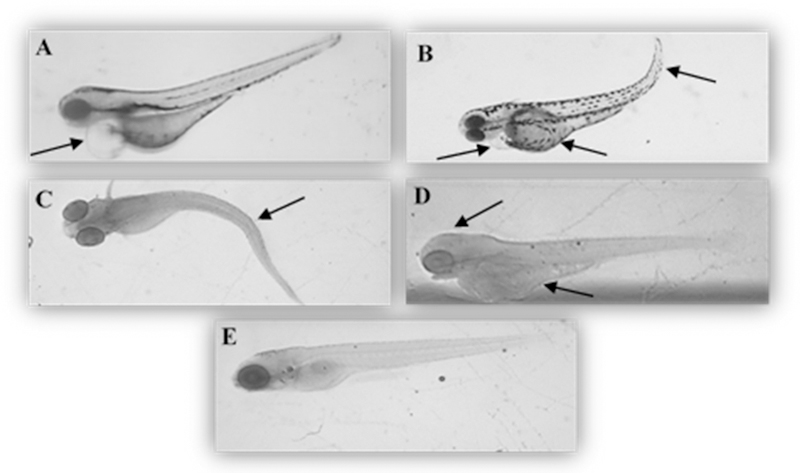

For the last three doses administered (3.48, 4.24, 5.12 mg/L) the Ru mass per larvae was approximately the same, ~3.7 ng indicating a threshold tolerance for Ru2. The exact delivered doses of Ru2 to the larvae for each concentration are shown in Figure S4. During the 5-day experiment, morphological lesions involving multiple tissues and organ systems were observed following Ru2 exposure. The morphological lesions included curved spine/tail malformation, yolk sac and pericardial sac edema, cranial malformation and underdeveloped eyes. These lesions were observed in zebrafish exposed to Ru2 starting from 2.18 to 5.12 mg/L. The most frequently observed grossly visible effects are summarized in Figure 7 and Table S2.

Figure 7.

Representative pictures of zebrafish lesions found at 72–120 hpf after treatment with Ru2 complex at different concentrations (A – 2.18 mg/L and B to D – 5.12) A: pericardial edema; B: yolk sac edema, pericardial edema and curved tail; C: curved spine; D: head malformation and yolk sac edema; E: control. The zebrafish embryos representative pictures were obtained with Olympus SZ-PT dissecting microscope equipped with Scion digital camera model CFW-1310C and analyzed with Photoshop software. Magnification 4X.

To better characterize adverse morphometric effects, endpoints such as intraocular distance, total body length, pericardial sac and yolk sac area were assessed. Intraocular distance was used to indicate changes in cranio-facial development following embryonic Ru2 exposure. The three highest concentrations of the compound tested (3.48, 4.24 and 5.12 mg/L) resulted in a significant decrease of intraocular distance which agrees with the underdeveloped eye and altered cranium structure.

The total body length measurement was used to determine if exposure to Ru2 during the embryonic life stages influenced larval growth. This compound caused significantly reduced body length following exposure to ≥ 1.17 mg/L with no significant differences observed at the first two lower doses (0.15 and 0.47 mg/L, respectively); an indication that this compound inhibits the overall growth of the organism. The observed curved tail and cranial abnormalities further support a skeletal impact. In higher vertebrates this might manifest itself in improper bone formation and skeletal abnormalities especially in utero and early juvenile development.

The pericardium is anterior to the yolk sac. The pericardial membrane surrounds the atrium and ventricle of the heart muscle and when fluid accumulates in this area, pericardial sac edema is observed (Figure 7A). Measuring the pericardial sac size is a common biomarker for a compromised cardiovascular system. The Ru2 compound caused a significantly increased pericardial sac size at both 2.18 mg/L and 5.12 (highest concentration), whereas no significant differences were observed for the lower concentrations.

The yolk sac is comprised of vitellogenin derived yolk-proteins, maternally supplied by the oocyte to fully support nutritional needs of the embryo/larvae prior to beginning feeding after 120 hpf. Measuring the yolk sac size is an important endpoint in determining whether the compound affected the volume of the available nutrients and their utilization in embryonic zebrafish. It was observed that the yolk sac size increased with increasing concentration of Ru2, which may indicate that the nutrients are not being taken up by the larvae. This data agrees with the yolk sac edema lesion observed for the highest concentration (Figure 7B). Yolk sac edema is not synonymous with yolk sac megaly. The edema is due to fluid accumulating outside the vasculature and the increased size is more indicative of an uptake of lipoproteins from the yolk sac.

Conclusions

Two structurally related compounds [Ru(η5-Cp)(PPh3)(2,2’-bipy-4,4’-R)]+ (with R = CH2OH, Ru1 or dibiotin ester, Ru2) were successfully synthesized. Ru1 crystallizes in a centrosymmetric triclinic P1̅ space group as enantiomer. Both compounds are cytotoxic against two different breast cancer cell lines, with IC50 better than cisplatin, and are among the best Ru organometallic compounds tested under the same experimental conditions[21–27]. While Ru1 was found to be a substrate for ABC transporters, Ru2 showed a remarkable selective inhibition for P-gp, showing promising results as a cytotoxic agent since none of the tested transporters confers resistance against its cytotoxic action. This is the first ruthenium organometallic compound showing P-gp inhibition, as far as we are aware, from the few results reported in the literature.[28,29] Ru2 is well tolerated in zebrafish up to 1.17 mg/L. The LC50 was found to be 5.73 mg/L at 5 days post fertilization.

Overall, comparing the structures of Ru1 and Ru2, it seems that the addition of a long leg-like chemical group to a substrate might be a powerful tool to create new inhibitors of ABC transporters. The potential of Ru2 as metallodrug will be further explored in order to unveil its mechanisms of action.

Experimental section

General procedures

All reactions and manipulations were performed under nitrogen atmosphere using Schlenk techniques. All solvents used were dried and freshly distilled under nitrogen prior to use, using standard methods. 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 spectrometer at probe temperature using commercially available deuterated solvents. 1H and 13C chemical shifts (s = singlet; d = duplet; t = triplet; m = multiplet) are reported in parts per million (ppm) downfield from internal standard Me4Si and the 31P NMR spectra are reported in ppm downfield from external standard, 85% H3PO4. Coupling constants are reported in Hz. All assignments were attributed using COSY, HMBC and HMQC NMR techniques. Infrared spectra were recorded on KBr pellets using a Mattson Satellite FT-IR spectrophotometer and only relevant bands were cited in the text. Electronic spectra were obtained at room temperature on a Jasco V-560 spectrometer from solutions of 10−3-10−5 M in quartz cuvettes (1 cm optical path). Elemental analyses were performed at Laboratório de Análises, at Instituto Superior Técnico, using a Fisons Instruments EA1 108 system. Data acquisition, integration and handling were performed using a PC with the software package EAGER-200 (Carlo Erba Instruments).

Synthesis

2,2’-bipyridine-4,4’-dibiotin ester (bipy-biotin)

The synthesis of the ligand bipy-biotin was done following a modified literature procedure.[15]

The synthesis was performed by addition of 4,4´-dihydroxymethyl-2,2´-bipyridine (0.150 g, 0.69 mmol), 5-[(3aS,4S,6aR)-2-oxohexahydro-1H-thieno[3,4-d] imidazol-4yl]pentanoic acid (biotin) (0.424 g, 1.74 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP; 0.085 g; 0.69 mmol) in dimethylformamide (DMF; 10 mL) to a stirred solution and with ice/water bath (0 °C). Then N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) was added (0.333 g; 1.735 mmol), to the colorless solution obtained and continue to stir for 30 minutes with the ice/water bath. After the 30 minutes, the bath was removed, and the solutions remained stirring all night at room temperature. On the next day the solvent was removed under vacuum and washed twice with water and diethyl ether and dried overnight.

Yield: 60 %; white powder. 1H NMR - [DMSO-d6, Me4Si, δ/ppm]: 8.68 [d, 2, 3JHH = 4.8, H1], 8.37 [s, 2, H4], 7.43 [d, 2, 3JHH = 4.8, H2], 6.45 [s, 2, NH], 6.37 [s, 2, NH], 5.25 [s, 4, H6], 4.28 [t, 4, 3JHH = 6,8, H15], 4.11 [t, 4, 3JHH = 4, H13), 3.08 (m, 2, H12), 2.80 (dd, 2, 3JHH = 4.0, 3JHH = 4.0, H16), 2.57 [d, 2, 3JHH = 12.4, H16], 2.44 [t, 4, 3JHH = 7.2, H8], 1.61 [m, 4, H9], 1.48 [m, 4, H11], 1.36 [m, 4, H10]. UV-Vis- [DMSO, λmax/nm (ε/M1cm−1)]: 286 (9495). FTIR [KBr, cm−1]: 3385, 3238 ( N-H amine), 3082 (υC-H aromatic), 2935, 2862 ( C-H alkanes), 1732 ( C=O ester), 1705 (υC=O ketone). Elemental analysis calc. for C32H40N6O6S2 (668.83 g/mol): C: 57.47, H: 6.03, N: 12.57, S: 9.59. Found: C: 57.01, H: 6.19, N: 12.47, S: 9.34.

[Ru(η5-Cp)(PPh3)(2,2’-bipyridine-4,4’-dimethanol)][CF3SO3] (Ru1)

To a stirred suspension of 0.36 g (0.5 mmol) of [Ru(η5-Cp)(PPh3)2Cl] in dichloromethane (30 mL), 0.13 (0.6 mmol) of 2,2’-bipyridine-4,4’-dimethanol were added followed by addition of 0.153 g (0.6 mmol) of AgCF3SO3. After refluxing for a period of 4 h the color changed slightly from orange to a darker orange. The reaction mixture was cooled down to room temperature and the solution was filtered to eliminate the AgCl and PPh3 precipitates. The solvent was then removed under vacuum. Ru1 was recrystallized once from dichloromethane/n-hexane and a second time from methanol/diethyl ether solution originating orange crystals.

Yield = 50 %. 1H NMR - [MeOD, Me4Si, δ/ppm]: 9.21 [d, 2, 3JHH = 4.0, H1], 7.92 [s, 2, H4], 7.36 [t, 3, 3JHH = 8.0, Hpara(PPh3)], 7.25 [m, 8, H2+Hmeta(PPh3)], 7.01 [t, 6, 3JHH = 8.0, Hortho(PPh3)], 4.74 [s, 5, η5-C5H5], 4.69 [s, 4, C6]. 13C NMR [MeOD, Me4Si, δ/ppm]: 156.9, 156.8 (C1+C3), 153.5 (C5); 134.1 (2JCP = 11, Cortho-PPh3); 133.1, 132.7 (Cq, PPh3); 131.2 (4JCP = 2, Cpara-PPh3); 129.5 (3JCP = 10, Cmeta-PPh3); 123.5 (C2); 121.3 (C4); 79.29 (2JCP = 2, η5-C5H5); 62.72 (C6). 31P NMR [MeOD, δ/ppm): 51.15 (s, PPh3). UV-Vis in CH2Cl2, λmax/nm (ε/M−1cm−1): 473 (Sh), 414 (4026), 352 (Sh), 292 (20719). FTIR [KBr, cm−1]: 3410 (υO-H), 3078–3057 (υC-H Cp and aromatic rings), 2850 (υC-H alkanes), 1616 and 1479 (υC=C), 1248 (υ(CF3SO3-)), 1223 (υC-O). Elemental analysis (%) Found: C, 53.7; H, 4.1; N, 3.4; S, 4.0. Calc. for C36H32N2PF3O5SRu: C, 54.5; H, 4.1; N, 3.5; S, 4.0. ESI-MS (+): calc. for [Ru1]+ m/z: 645.12, found m/z: 644.91.

[Ru(η5-Cp)(PPh3)(bipy-biotin)][CF3SO3] (Ru2)

To a stirred and degassed solution of [Ru(η5-Cp)(PPh3)2Cl] (0.353 g, 0.49 mmoles) in methanol (40 mL) was added AgCF3SO3 (0.125 g, 0.49 mmoles). The resulting mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature followed by the addition of bipy-biotin (0.250 g, 0.37 mmoles). After an 6 h reflux the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, filtered and the solvent was removed under vacuum. Orange crystalline powder was obtained after recrystallization from dichloromethane/n-hexane and THF/n-hexane.

Yield: 86 %. 1H NMR - [(CD3)2CO, Me4Si, δ/ppm]: 9.50 [d, 2, 3JHH = 4.0, H1], 8.11 [s, 2, H4], 7.43 [m, 4, Hpara(PPh3)], 7.33 [m, 9, Hmeta(PPh3) + H2], 7.12 [t, 6, 3JHH = 8.0, Hortho(PPh3)], 6.20 [d, 2, J = 16.0, NH], 6.16 [s, 2, NH], 5.25 [d, 4, 2JHH = 4.0, H6], 4.93 [s, 5, η5-C5H5], 4.50 [m, 2, H15], 4.33 [m, 2, H13], 3.22 [m, 2, H12], 2.94 [m, 2, H16], 2.69 [t, 2, 3JHH = 12, H16], 2.51 [m, 4, H8], 1.74 [m, 4, H9], 1.64 [m, 4, H11], 1.49 [m, 4, H10]. 13C NMR [(CD3)2CO, δ/ppm]: 173.6 (C7), 164.1 (C14), 157.1 (C1), 156.5 (C5), 147.6 (C3), 134.0 (2JCP = 11, Cortho-PPh3), 132.4 (1JCP = 41, Cq, PPh3), 131.2 (4JCP = 1, Cpara-PPh3), 129.5 (3JCP = 9, Cmeta-PPh3), 124.6 (4JCP = 8, C2), 122.6 (4JCP = 11, C4), 79.54 (2JCP = 2, η5-C5H5), 64.2 (C6), 62.6 (C13), 60.9 (C15), 56.7 (C12), 41.1 (C16), 34.3 (C8), 29.97 (under the signal of the solvent, C10, C11), 25.8 (C9). 31P NMR [(CD3)2CO, δ/ppm]: 51.2 (s, PPh3). UV-vis [DMSO, λmax/nm (ε x 103 / M−1cm−1)]: 296 (23.5), 353 (Sh), 430 (4.0), 486 (Sh). UV-vis [CH2Cl2, λmax/nm (ε x 103/ M−1cm−1)]: 249 (Sh), 293 (21.7), 347 (Sh), 428 (4.2), 488 (Sh). FTIR [KBr, cm−1]: 3074 (υC-H Cp and aromatic rings), 2929, 2860 (υC-H alkanes), 1736 (υC=O ester), 1701 (υC=O ketone), 1435 (υC=C Cp and aromatic rings), 1261 (υ(CF3SO3-)). Elemental analyses calc. for C56H60F3N6O9PRuS3 (1246.35 g/mol): C, 54.0; H, 4.9; N, 6.7; S, 7.7. Found: C, 53.9; H, 4.9; N, 6.2; S, 7.5. ESI-MS (+): calc. for [Ru2]+ m/z: 1096.95, found m/z: 1097.28.

X‐ray crystal structure determination

Three-dimensional X-ray data for [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’-diyldimethanol-2,2’bipyridine)][CF3SO3] Ru1 were collected on a Bruker SMART Apex CCD diffractometer at 100(2) K, using a graphite monochromator and Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) by the ϕ-ω scan method. Reflections were measured from a hemisphere of data collected of frames each covering 0.5 degrees in ω. Of the 265907 reflections measured in Ru1, all of which were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects, and for absorption by semi-empirical methods based on symmetry-equivalent and repeated reflections, 8335 independent reflections exceeded the significance level |F|/σ(|F|) > 4.0, respectively. Complex scattering factors were taken from the program package SHELXTL.[30] The structure was solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least-squares methods on F2. The non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic thermal parameters in all cases. Hydrogen atoms were located in difference Fourier map and left to refine freely, except for C(2S), C(3SA), C(3SB), C(3) and C(4), which were included in calculation positions and refined in the riding mode. A final difference Fourier map showed no residual density outside: 0.986 and −0.783 e.Å−3. A weighting scheme w = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (0.049500 P)2 + 7.468500 P] for Ru1, where P = (|Fo|2 + 2|Fc|2)/3, were used in the latter stages of refinement. The site occupancy factor was 0.45910 for C(3SA) and O(1SA). CCDC No. 1869965 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for Ru1. These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html, or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: (+44) 1223–336-033; or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk. Crystal data and details of the data collection and refinement for the new compounds are collected in Table 6.

Table 6.

Crystal data and structure refinement for [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(4,4’diyldimethanol-2,2’-bipyridine)][CF3SO3] Ru1.

| Ru1 | |

|---|---|

| Formula | C36 H32 F3 N2 O5 P Ru S |

| Formula weight | 793.74 |

| T, K | 100(2) |

| Wavelength, Å | 0.71073 |

| Crystal system | Triclinic |

| Space group | P 1 |

| a/Å | 11.4703(6) |

| b/Å | 11.6069(6) |

| c/Å | 13.4443(7) |

| α/º | 75.737(3) |

| β/º | 81.039(3) |

| γ/º | 69.653(3) |

| V/Å3 | 1621.64(15) |

| Z | 2 |

| F000 | 808 |

| Dcalc/g cm−3 | 1.626 |

| µ/mm−1 | 0.663 |

| θ/ (º) | 1.57 to 25.19 |

| Rint | 0.0431 |

| Crystal size/ mm3 | 0.37 × 0.25 × 0.10 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.132 |

| R1 a | 0.0315 |

| wR2 (all data) b | 0.0973 |

| Largest differences peak and hole (eÅ−3) | 0.854 and −0.748 |

R1 = Σ||Fo| - |Fc||/Σ|Fo|.

wR2 = {Σ[w(||Fo|2 -|Fc|2|)2]|/Σ[w(Fo2)2]}1/2

Stability studies in DMSO and DMSO/DMEM

For the stability studies, all complexes were dissolved in DMSO or 5% DMSO/95% DMEM at ca.1 × 10−4 M and their electronic spectra were recorded in the range allowed by the solvents at set time intervals.

Biological Evaluation

Cell lines and culture conditions

To evaluate the selectivity of the compounds on other ABC transporters, NIH3T3 parental cell line and NIH3T3/ABCB1 drug resistant cell line transfected with human MDR1/A-G185, purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were used, as previously described.[31] HEK293 (Human embryonic kidney cell) were used to express the pcDNA3.1-hABCG2 plasmid[32] and Flp-In™−293 cells to express ABCC1 and ABCC2 genes transfected by electroporation using Neon® Transfection System (ThermoFisher scientific) with pcDNA5-FRT-ABCC1 or pcDNA5-FRT-ABCC2 respectively as previously described[33]. MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer human tumor cell lines were obtained from ATCC.

Cells were grown at 37 ºC in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles’s medium (DMEM high glucose) (PAA, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Velizy-Villacoublay, France) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, PAA, GE Healthcare Life sciences, Velizy-Villacoublay, France), 1% penicillin / streptomycin (PAA, GE Healthcare Life sciences, Velizy-Villacoublay, France), with selection agent for the MRP1, MRP2, BCRP P-gp-transfected cell lines. The MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM medium with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

All cells were adherent in monolayers and, upon confluence, were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) 1x and harvested by digestion with trypsin 0.05% (v/v). Trypsin was inactivated by adding fresh complete culture media to the culture flask. Cells were then suspended and transferred into new, sterile, culture flasks, or seeded in sterile test plates for the different assays.

All cells were manipulated under aseptic conditions in a flow chamber.

Compounds dilution and storage

All compounds were dissolved in DMSO and divided in aliquots of 10 µL each. After, they were store at −20 ºC until use.

Compound cytotoxicity evaluated by MTT assay

The cells were adherent in monolayers and, upon confluency, were harvested by digestion with trypsin-EDTA. The cytotoxicity of the complexes against the tumor cells was assessed using the colorimetric assay MTT (3-(4,5–2-yl)-2,5-ditetrazolium bromide), which measures conversion of the yellow tetrazolium into purple formazan by mitochondrial redox activity in living cells. For this purpose, cells (10–20 × 103 in 200 µL of medium) were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 ºC. Cells were allowed to settle for 24 h followed by the addition of a dilution series of the complexes in medium (200 µL). The complexes (Ru1 and Ru2) were first solubilized in DMSO, then in medium within the concentration range 0.1–100 µM. Cisplatin (the reference compound), was first solubilized in H2O and then added at the same concentrations used for the ruthenium complexes. DMSO did not exceed 1% even for the higher concentration used and was without cytotoxic effect. After 24 h incubation (MDA-MB-231 and MCF7) or 48 h incubation (NIH3T3 and HEK293), the treatment solutions were removed by aspiration and MTT solution (200 µL, 0.5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well. After 3–4 h at 37 ºC/ 5% CO2, the solution was removed, and the purple formazan crystals formed inside the cells were dissolved in DMSO (200 µL) by thorough shaking. The cellular viability was evaluated by measuring the absorbance at 570 nm by using a plate spectrophotometer.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were seeded at a density of 105 cells/well into 24-well culture plates. After a 24-hour incubation period, they were exposed to different concentrations of compounds and substrates for 30 minutes at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After treatment, cells were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and detached from the plates with trypsin. Trypsin was neutralized with PBS-BSA 2% (Bovine Serum Albumin). Cells were then resuspended and transferred to cytometer tubes. The samples were kept on ice until analysis with a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) or BD LSR-II system.

3D Modeling and docking studies

The human P-gp 3D model was based on the mouse P-gp structure (PDB 4q9h)[34] which shares 87% of sequence identity. Sequence alignment of the mouse P-gp (UniProtKB P21447) and human P-gp (UniProtKB P08183) was performed with the AlignMe server.[35] One model was chosen and refined between twenty generated with Modeller 9.19.[36] For docking experiment, the protein, flexible residues within the drug-binding pocket and ligands were prepared with AutoDockTools 4.[37,38] Computations were performed by Autodock Vina 1.1.2[39] to generate 10 poses per molecule with an exhaustiveness parameter of 32. As Autodock Vina does not support Ru atom (Rii = 2.96 Å, epsii = 0.056 kcal.mol−1, vol =12.000 Å3), it was replaced with F (Rii = 3.09 Å, epsii = 0.080 kcal.mol−1, vol = 15.448 Å3) which has the closest energy parameters between all supported atoms, and then replaced back to Ru in resulting poses for visualization purpose.

In vivo toxicity assessment using zebrafish embryos.

The AB strain zebrafish (Zebrafish International Resource Center, Eugene, OR) was used for all experiments. Breeding stocks were bred and housed in Aquatic Habitats (Apopka, FL) recirculating systems under a 14/10 h light/dark cycle. System water was obtained by carbon/sand filtration of municipal tap water and water quality was maintained at <0.05 ppm nitrite, <0.2 ppm ammonia, pH between 7.2 and 7.7, and water temperature between 26 and 28 ºC. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the zebrafish husbandry protocol and embryonic exposure protocol (#08–025) approved by the Rutgers University Animal Care and Facilities Committee.

Males and females were maintained separately and co-mingled the night before to allow spawning the next morning. Spawning substrates were placed into the fish tanks on the day prior to spawning. In case eggs were obtained from more than one set of breeders all eggs that were fertilized and progressing normally through development were mixed. Zebrafish embryos were exposed to different concentrations of Ru2 solutions (0.15, 0.47, 1.17, 2.18, 3.48, 4.24, 5.12, 6.57 mg/L) at 0.05 % of DMSO in individual glass vials through a waterborne exposure from 3 h postfertilization (hpf) until 120 hpf (5 days) in a static non-renewal protocol. The solutions were prepared from a Ru2 stock solution of 12.33 mg/L.

The exposure followed a modified OECD 236 protocol (OECD. 2013), where the endpoints of lesion presence, length and mortality were recorded, during the major stages of organ development and the toxicological estimates (LC50, NOEC, LOEC and NOAEL) were determined. Those embryos surviving at the end of the toxicological experiment (120 hpf) were used for both morphological data and ICP-MS Ru quantification analysis.

For morphological data, approximately 12 individual larvae from each Ru2 concentration and control group were fixed in formalin and then stained for bone and cartilage following a two-color acid free Alcian Blue/Alizarin red stain.[40] Photographs were taken using a Scion digital camera model CFW-1310C mounted on an Olympus SZ-PT dissecting microscope and cartilage/bone were measured using Adobe Photoshop. Endpoints examined included total body length, intraocular distance, and yolk sac size to assess larval growth, cranial facial development, and nutrient storage and usage, respectively (Supp.Inf. – Fig.S5).

For the analytical data, the solutions in each vial were collected for ICP-MS analysis and the larvae were euthanized and fixed with 10 % buffered formalin phosphate.[41]

Three replicates containing larvae from each concentration were also collected for ICPMS analysis (see below).

Each concentration of Ru2 compound and corresponding control group was set up as individual experiments, and the sample size was between 30–40 embryos, and repeated two times. The controls had >90 % survival rate.

Quantification of ruthenium by Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Samples were quantified via high resolution ICP-MS (Nu Instruments Attom®, UK) at Rutgers EOHSI Analytical Facility. The instrument settings for the ICP-MS are provided in Table 7. Larval samples were microwave digested using a MARS X microwave digester (CEM Matthews NC) in OmniTrace® Nitric acid and diluted to 3.5% acid with 30 % hydrogen peroxide solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Ru2 spiked egg water treatments were acidified to 3.5%. The samples were introduced through a ASX-500 Model 510 Auto Sampler (Cetac®) and into a Gass Expansion Conikal Nebulizer within the Peltier cooling system. Data was sent into the Attom software (Attolab v.1) and analyzed with NuQuant by using a seven-point calibration curve. The limit of quantification for these samples was 0.005 ppb and ruthenium isotopes 99, 100, 101, and 102 were quantified. It is important to note that an oxide of strontium, an ingredient in salt water solutions, like egg water, has considerable isobaric interference for ruthenium 100. No isobaric interferences were noted for larval samples. The ruthenium concentrations given by ICP-MS in µg/L (ppb) were converted to Ru2 concentrations in mg/L.

Table 7.

ICP-MS Method

| Method Settings | Parameter |

|---|---|

| Analysis Mode | Deflector Jump, single mass jump |

| Dwell Time Per Peak | 4 ms |

| Switch Delay Per Peak (×10 us) | 2 |

| Number Sweeps | 450 |

| Number of Cycles | 1 |

| Instrument Resolutuion | 300 |

| Scan Window (%) | 0 |

| Peak Center Mass | None |

| Detection Mode | Attenuated |

| Park Mass | 98.90594 |

Supplementary Material

[Ru(η5-Cp)(PPh3)(2,2’-bipy-4,4’-dibiotin ester)]+ (Ru2) is more cytotoxic for MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines than cisplatin

Ru2 has exceptional selectivity as P-gp inhibitor

LC50 of Ru2 in zebrafish is 5.73 mg/L at 5 days post fertilization.

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, FCT) within the scope of projects UID/QUI/00100/2013 and PTDC/QUI-QIN/28662/2017. Andreia Valente acknowledges the Investigator FCT2013 Initiative for the project IF/01302/2013 (acknowledging FCT, as well as POPH and FSE - European Social Fund). Leonor Côrte-Real thanks FCT for her Ph.D. Grant (SFRH/BD/100515/2014) and Fulbright Research Grant 2017/2018 with the support of FCT. Brittany Karas thanks NJAESRutgersNJ01201, NIEHS Training Grant T32-ES 007148 and Brian Buckley, Cathleen Doherty NIEHS P30 ES005022. Keith R. Cooper thanks NJAES Project 01202 (W2045), NIH ES005022. Patrícia Gírio was funded by the Erasmus + Program and a fellowship received from the French National Research Agency, ANR-13-BSV5–000101 (to Dr. Pierre Falson).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Pluchino KM, Hall MD, Goldsborough AS, Callaghan R, Gottesman MM, Collateral sensitivity as a strategy against cancer multidrug resistance, Drug Resist. Updat 15 (2012) 98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lehne G, P-glycoprotein as a Drug Target in the Treatment of Multidrug Resistant Cancer, Curr. Drug Targets 1 (2000) 85–99. doi: 10.2174/1389450003349443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Takara K, Sakaeda T, Okumura K, An update on overcoming MDR1-mediated multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy., Curr. Pharm. Des 12 (2006) 273– 286. doi: 10.2174/138161206775201965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang J, Seebacher N, Shi H, Kan Q, Duan Z, Novel strategies to prevent the development of multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer, Oncotarget 8 (2015) 84559–84571. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Palmeira A, Vasconcelos MH, Paiva A, Fernandes MX, Pinto M, Sousa E, Dual inhibitors of P-glycoprotein and tumor cell growth: (Re)discovering thioxanthones, Biochem. Pharmacol 83 (2012) 57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Matos A, Mendes F, Valente A, Morais T, Tomaz AI, Zinck P, Garcia MH, Bicho MB, Marques F, Ruthenium-Based Anticancer Compounds: Insights into Their Cellular Targeting and Mechanism of Action, in: and J.L.B.J. Holder Alvin A., Lilge Lothar, Browne Wesley R., Lawrence Mark A.W.(Ed.), Ruthenium Complexes Photochem. Biomed. Appl, First Edit, 2018Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2018: pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Côrte-Real L, Teixeira RG, Gírio P, Comsa E, Moreno A, Nasr R, Baubichon-Cortay H, Avecilla F, Marques F, Robalo MP, Mendes P, Ramalho JPP, Garcia MH, Falson P, Valente A, Methyl-cyclopentadienyl Ruthenium Compounds with 2,2′-Bipyridine Derivatives Display Strong Anticancer Activity and Multidrug Resistance Potential, Inorg. Chem 57 (2018). doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Teixeira RG, Brás AR, Côrte-Real L, Tatikonda R, Sanches A, Robalo MP, Avecilla F, Moreira T, Garcia MH, Haukka M, Preto A, Valente A, Novel ruthenium methylcyclopentadienyl complex bearing a bipyridine perfluorinated ligand shows strong activity towards colorectal cancer cells, Eur. J. Med. Chem 143 (2018) 503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Côrte-Real L, Mendes F, Coimbra J, Morais TS, Tomaz AI, Valente A, Garcia MH, Santos I, Bicho M, Marques F, Anticancer activity of structurally related ruthenium(II) cyclopentadienyl complexes, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 19 (2014) 853–867. doi: 10.1007/s00775-014-1120-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Moreno V, Font-Bardia M, Calvet T, Lorenzo J, Avilés FX, Garcia MH, Morais TS, Valente A, Robalo MP, DNA interaction and cytotoxicity studies of new ruthenium(II) cyclopentadienyl derivative complexes containing heteroaromatic ligands, J. Inorg. Biochem 105 (2011) 241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Côrte-Real L, Paula Robalo M, Marques F, Nogueira G, Avecilla F, Silva TJL, Santos FC, Isabel Tomaz A, Helena Garcia M, Valente A, The key role of coligands in novel ruthenium(II)-cyclopentadienyl bipyridine derivatives: Ranging from non-cytotoxic to highly cytotoxic compounds, J. Inorg. Biochem 150 (2015) 148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Valente A, Garcia MH, Marques F, Miao Y, Rousseau C, Zinck P, First polymer “ruthenium-cyclopentadienyl” complex as potential anticancer agent, J. Inorg. Biochem 127 (2013) 79–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Morais TS, Valente A, Tomaz AI, Marques F, Garcia MH, Tracking antitumor metallodrugs: Promising agents with the Ru(II)- and Fe(II)cyclopentadienyl scaffolds, Future Med. Chem 8 (2016) 527–544. doi: 10.4155/fmc.16.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mitra K, Shettar A, Kondaiah P, Chakravarty AR, Biotinylated Platinum(II) Ferrocenylterpyridine Complexes for Targeted Photoinduced Cytotoxicity, Inorg. Chem 55 (2016) 5612–5622. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Haddour N, Gondran C, Cosnier S, A new biotinylated tris bipyridinyl iron ( II ) complex as redox biotin-bridge for the construction of supramolecular biosensing architectures, Time (2004) 324–325. doi: 10.1039/b311566f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Govindaswamy P, Linder D, Lacour J, Süss-Fink G, Therrien B, Chiral or not chiral? A case study of the hexanuclear metalloprisms [Cp(6)M(6)(micro(3)-tptkappaN)(2)(micro-C2O4-kappaO)(3)]6+ (M = Rh, Ir, tpt = 2,4,6-tri(pyridin-4yl)-1,3,5-triazine)., Dalton Trans 6 (2007) 4457–63. doi: 10.1039/b709247d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Côrte-Real L, Matos AP, Alho I, Morais TS, Tomaz AI, Garcia MH, Santos I, Bicho MP, Marques F, Cellular uptake mechanisms of an antitumor ruthenium compound: The endosomal/lysosomal system as a target for anticancer metal-based drugs, Microsc. Microanal 19 (2013) 1122–1130. doi: 10.1017/S143192761300175X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shive HR, Zebrafish Models for Human Cancer, Vet. Pathol 50 (2013) 468–482. doi: 10.1177/0300985812467471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sukardi H, Chng HT, Chan ECY, Gong Z, Lam SH, Zebrafish for drug toxicity screening: bridging the in vitro cell-based models and in vivo mammalian models, Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol 7 (2011) 579–589. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.562197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].O. Guidelines, F.O.R. The, T. Of, Test No. 236: Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test, (2013) 1–22. doi: 10.1787/9789264203709-en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Morais TS, Santos FC, Jorge TF, Côrte-Real L, Madeira PJA, Marques F, Robalo MP, Matos A, Santos I, Garcia MH, New water-soluble ruthenium(II) cytotoxic complex: Biological activity and cellular distribution, J. Inorg. Biochem 130 (2014) 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Caruso F, Pettinari R, Rossi M, Monti E, Gariboldi MB, Marchetti F, Pettinari C, Caruso A, Ramani MV, Subbaraju GV, The in vitro antitumor activity of arene-ruthenium(II) curcuminoid complexes improves when decreasing curcumin polarity, J. Inorg. Biochem 162 (2016) 44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ramadevi P, Singh R, Jana SS, Devkar R, Chakraborty D, Mixed ligand ruthenium arene complexes containing N-ferrocenyl amino acids: Biomolecular interactions and cytotoxicity against MCF7 cell line, J. Organomet. Chem 833 (2017) 80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2017.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].İnan A, Sünbül AB, İkiz M, Tayhan SE, Bilgin S, Elmastaş M, Sayın K, Ceyhan G, Köse M, İspir E, Half-sandwich Ruthenium(II) arene complexes bearing the azo-azomethine ligands: Electrochemical, computational, antiproliferative and antioxidant properties, J. Organomet. Chem 870 (2018) 76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Biancalana L, Zacchini S, Ferri N, Lupo MG, Pampaloni G, Marchetti F, Tuning the cytotoxicity of ruthenium(ii) para-cymene complexes by monosubstitution at a triphenylphosphine/phenoxydiphenylphosphine ligand, Dalt. Trans 46 (2017) 16589–16604. doi: 10.1039/c7dt03385k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tadić A, Poljarević J, Krstić M, Kajzerberger M, Aranelović S, Radulović S, Kakoulidou C, Papadopoulos AN, Psomas G, Grgurić-Šipka S, Rutheniumarene complexes with NSAIDs: Synthesis, characterization and bioactivity, New J. Chem 42 (2018) 3001–3019. doi: 10.1039/c7nj04416j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mohan N, Mohamed Subarkhan MK, Ramesh R, Synthesis, antiproliferative activity and apoptosis-promoting effects of arene ruthenium(II) complexes with N, O chelating ligands, J. Organomet. Chem 859 (2018) 124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Romero-Canelón I, Pizarro AM, Habtemariam A, Sadler PJ, Contrasting cellular uptake pathways for chlorido and iodido iminopyridine ruthenium arene anticancer complexes, Metallomics 4 (2012) 1271–1279. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20189e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pazinato J, Cruz OM, Naidek KP, Pires ARA, Westphal E, Gallardo H, Baubichon-Cortay H, Rocha MEM, Martinez GR, Winnischofer SMB, Di Pietro A, Winnischofer H, Cytotoxicity of η6-areneruthenium-based molecules to glioblastoma cells and their recognition by multidrug ABC transporters, Eur. J. Med. Chem 148 (2018) 165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sheldrick GM, SHELXL-97: An Integrated System for Solving and Refining Crystal Structures from Diffraction Data (Revision 5.1), Univ. Göttingen, Ger. (1997). [Google Scholar]

- [31].Arnaud O, Koubeissi A, Ettouati L, Terreux R, Alamé G, Grenot C, Dumontet C, Di Pietro A, Paris J, Falson P, Potent and fully noncompetitive peptidomimetic inhibitor of multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein, J. Med. Chem 53 (2010) 6720–6729. doi: 10.1021/jm100839w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gilson P, Josa-Prado F, Beauvineau C, Naud-Martin D, Vanwonterghem L, Mahuteau-Betzer F, Moreno A, Falson P, Lafanechère L, Frachet V, Coll JL, Fernando Díaz J, Hurbin A, Busser B, Identification of pyrrolopyrimidine derivative PP-13 as a novel microtubule-destabilizing agent with promising anticancer properties, Sci. Rep 7 (2017) 1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09491-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Baiceanu E, Nguyen KA, Gonzalez-Lobato L, Nasr R, Baubichon-Cortay H, Loghin F, Le Borgne M, Chow L, Boumendjel A, Peuchmaur M, Falson P, 2-Indolylmethylenebenzofuranones as first effective inhibitors of ABCC2, Eur. J. Med. Chem 122 (2016) 408–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Szewczyk P, Tao H, McGrath AP, Villaluz M, Rees SD, Lee SC, Doshi R, Urbatsch IL, Zhang Q, Chang G, Snapshots of ligand entry, malleable binding and induced helical movement in P-glycoprotein, Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr 71 (2015) 732–741. doi: 10.1107/S1399004715000978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Stamm M, Staritzbichler R, Khafizov K, Forrest LR, AlignMe--a membrane protein sequence alignment web server, Nucleic Acids Res 42 (2014) W246–W251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Šali A, Blundell TL, Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints, J. Mol. Biol 234 (1993) 779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Morris G, Huey R, AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility, J. Comput. Chem 30 (2009) 2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256.AutoDock4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sanner MF, Python: A Programming Language For Software Integration And Development, J. Mol. Graph. Model 17 (1999) 55–84. doi: 10.1016/S10933263(99)99999-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Brooks BR, III CLB, Mackerell JAD, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, Caves L, Cui Q, Dinner AR, Feig M, Fischer S, Gao J, Hodoscek MWI, Karplus M, CHARMM: The Biomolecular Simulation Program B., J. Comput. Chem 30 (2009) 1545– 1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Walker MB, Kimmel CB, A two-color acid-free cartilage and bone stain for zebrafish larvae, Biotech. Histochem 82 (2007) 23–28. doi: 10.1080/10520290701333558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].L. Karas B; Buckley B; Cooper KR; White, Novel High Throughput Screening of Transition Metal Based Anticancer Compounds Using Zebrafish Embryos and ICP-MS Analysis, in: Jt. Grad. Progr. Toxicol. Piscataway, NJ. Soc. Toxicol. 57th Natl. Annu. Meet, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.