Abstract

Male germ cells of all placental mammals express an ancient nuclear RNA binding protein of unknown function called RBMXL2. Here we find that deletion of the retrogene encoding RBMXL2 blocks spermatogenesis. Transcriptome analyses of age-matched deletion mice show that RBMXL2 controls splicing patterns during meiosis. In particular, RBMXL2 represses the selection of aberrant splice sites and the insertion of cryptic and premature terminal exons. Our data suggest a Rbmxl2 retrogene has been conserved across mammals as part of a splicing control mechanism that is fundamentally important to germ cell biology. We propose that this mechanism is essential to meiosis because it buffers the high ambient concentrations of splicing activators, thereby preventing poisoning of key transcripts and disruption to gene expression by aberrant splice site selection.

Research organism: Mouse

eLife digest

In humans and other mammals, a sperm from a male fuses with an egg cell from a female to produce an embryo that may ultimately grow into a new individual. Sperm and egg cells are made when certain cells in the body divide in a process called meiosis. Many proteins are required for meiosis to happen and these proteins are made using instructions provided by genes, which are made of a molecule called DNA.

The DNA within a gene is transcribed to make molecules of ribonucleic acid (or RNA for short). The cell then modifies many of these RNAs in a process called splicing before using them as templates to make proteins. During splicing, segments of RNA known as introns are discarded and other segments termed exons are joined together. Some exons may also be removed from RNAs in different combinations to create different proteins from the same gene.

A protein called RBMXL2 is able to bind to RNA molecules and is only made during and after meiosis in humans and most other mammals. RBMXL2 can also bind to other proteins that are known to be involved in controlling splicing of RNAs, but its role in splicing remains unclear.

To address this question, Ehrmann et al. studied the gene that encodes the RBMXL2 protein in mice. Removing this gene prevented male mice from being able to make sperm. Further experiments using a technique called RNA sequencing showed that the RBMXL2 protein helps to ensure that splicing happens correctly by preventing bits of exons and introns in mouse genes from being rearranged. These findings suggest that the gene encoding RBMXL2 is part of a splicing control mechanism that is important for making sperm and egg cells.

The work of Ehrmann et al. could eventually help some couples understand why they have problems conceiving children. Male infertility is poorly understood, and not knowing its causes can harm the mental health of affected men. Furthermore, these findings may help researchers to understand the role of a closely related protein called RBMY that has also been linked to infertility in men, but is much more difficult to study.

Introduction

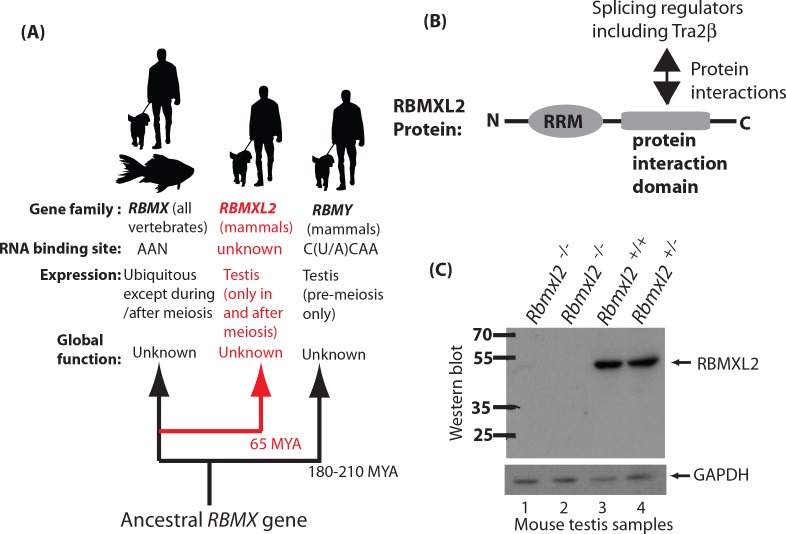

It has been a long recognised hallmark of mammalian gene expression patterns that there are extremely high levels of transcription and transcriptome complexity in testicular cells (de la Grange et al., 2010; Licatalosi, 2016; Soumillon et al., 2013; Pan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008; Clark et al., 2007; Grosso et al., 2008; Yeo et al., 2004). These high gene expression levels are thought to result from epigenetic changes that favour relaxed patterns of gene expression during meiosis – the unique form of division used to generate sperm and eggs (Soumillon et al., 2013). Many nuclear RNA-binding proteins are differentially expressed during and immediately after meiosis (Grellscheid et al., 2011; Schmid et al., 2013). These include the nuclear RNA binding protein RBMXL2 (also known as hnRNP GT) that is expressed only during and immediately after male meiosis, but not in the preceding spermatogonial cells (Ehrmann et al., 2008) (Figure 1A). Consistent with an important function in germ cell development, genetic studies have identified point mutations within infertile men in the human chromosome 11 RBMXL2 gene (Westerveld et al., 2004). A further connection to male infertility is that RBMXL2 belongs to the same gene family as RBMY, which was historically the first human Y chromosome infertility gene identified in the search for the AZF (AZOOSPERMIA FACTOR) gene (Ma et al., 1993).

Figure 1. Creation of a mouse model which does not express the testis-specific RNA binding protein RBMXL2.

(A) The RBMXL2 gene evolved via retrotransposition of RBMX early in mammalian evolution. The cladogram shows three members of the gene family that derived from an ancestral RBMX gene, summarising their global functions, expression, and RNA binding sites of their encoded proteins. (B) Modular structure of the RBMXL2 protein, showing the known protein interaction with Tra2β. (C) Western blot confirming no RBMXL2 protein is made within 2 replicate samples of Rbmxl2-/- adult testis, compared to wild type (Rbmxl2+/+) and heterozygous (Rbmxl2+/-) adult testes.

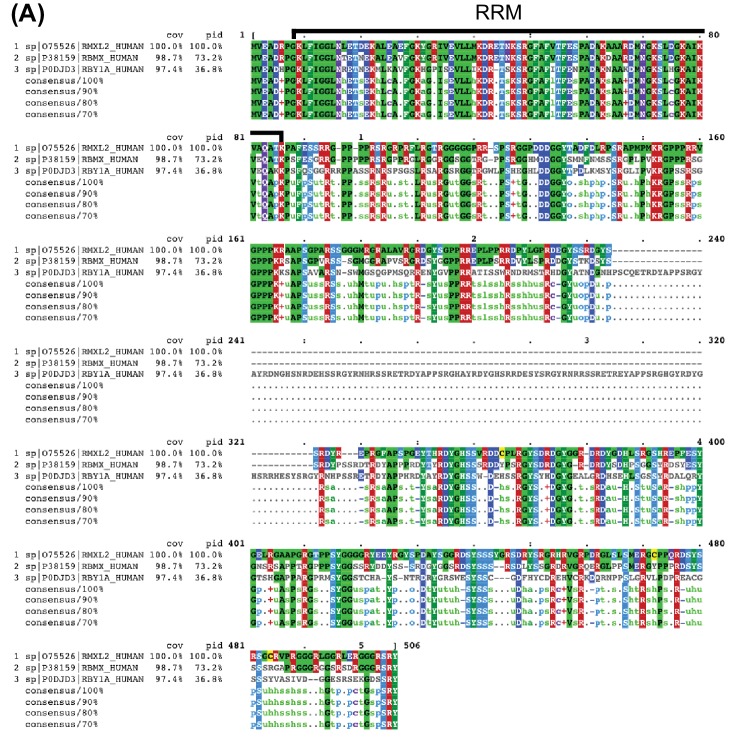

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Alignment of RBMXL2 with RBMX and RBMY.

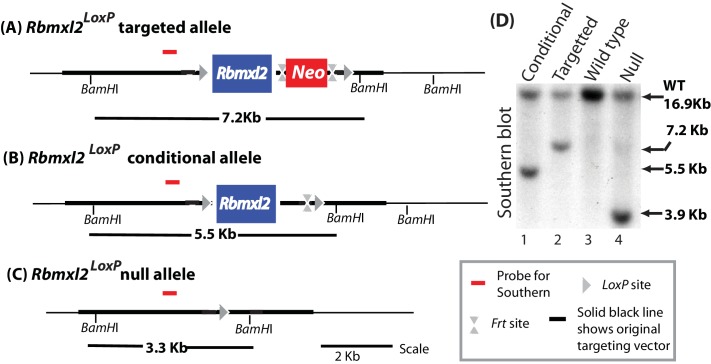

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Genomic organisation of different genotype mice.

RBMXL2 evolved ~65 million years ago via retrotransposition of an mRNA from the X chromosome located RBMX gene (Figure 1A). An RBMXL2 gene is found in all placental mammals, which is consistent with a fundamental role in germ cell biology. This role remains to be identified, but RBMXL2 protein has an N-terminal RNA Recognition Motif (abbreviated RRM, Figure 1B). RBMX and RBMY proteins are also nuclear RNA binding proteins that are very similar to RBMXL2 (73.2% and 36.8% overall identity to RBMX and RBMY, respectively; 93.7% and 77.2% identity within the RRMs, Figure 1—figure supplement 1). The RNA binding specificity of RBMXL2 protein is unknown, but both RBMX and RBMY proteins bind to AA dinucleotide-containing RNA sequences (Cléry et al., 2011; Moursy et al., 2014; Nasim et al., 2003). The RBMXL2, RBMX and RBMY proteins interact with and modulate the splicing activity of Tra2β and SR proteins in vitro (Figure 1B) (Cléry et al., 2011; Moursy et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2009; Nasim et al., 2003; Elliott et al., 2000a), suggesting a role in splicing control. Maintaining proper ratios of mRNA splice isoforms can be critical in normal development (Kalsotra and Cooper, 2011), where changes in isoforms can have effects on encoded proteins ranging from major to subtle. Alternative splicing is known to be critical for germ cell development. For example, deletion of the splicing regulator protein PTBP2 within germ cells affects mRNA isoforms important for cell-cell communication with Sertoli cells (Hannigan et al., 2017). Some alternative splicing events in the testis are conserved between humans and mice so may control fundamental aspects of germ cell biology (Schmid et al., 2013). However many alternative splicing patterns are not conserved between humans and mice (Kan et al., 2005). RBMX protein is also reported to control transcription (Takemoto et al., 2007), affect DNA double strand repair and mitotic sister chromatid cohesion (Adamson et al., 2012; Matsunaga et al., 2012), and to bind to m6A methylated RNA (Liu et al., 2017).

The function of RBMXL2 and why this RNA binding protein has been conserved across placental mammals are not known. A major factor limiting understanding of endogenous RBMXL2 functions has been the absence of a reliable mouse model. Development of a mouse model is also critical to test the importance of this wider family of RNA binding proteins in germ cell development. Men carrying the AZFb deletion on their Y chromosomes are missing RBMY genes and undergo meiotic arrest. However, it is unclear if RBMY loss is causing this phenotype, because the deletion interval encompasses several other genes which could contribute to male infertility (Elliott, 2000; Vogt et al., 1996). Within the meiotic and immediately post-meiotic germ cells which express RBMXL2, the RBMX and RBMY genes are transcriptionally inactivated within a heterochromatic structure called the XY body (Wang, 2004). Meiosis thus provides a genetically tractable window to probe RBMXL2 function where there should be no redundancy effects possible with either RBMX or RBMY. Hence to discover what RBMXL2 does in the germline we have made a conditional Rbmxl2 gene knockout mouse. Analysis of this knockout mouse reveals that RBMXL2 protein is essential for meiosis and has a major role in protecting the meiotic transcriptome from aberrant selection of cryptic splice sites that are normally ignored by the spliceosome. Our data suggest this fundamentally important process operates so efficiently in meiosis that it has been previously undetected, yet is critical to avoid male infertility caused by aberrant splicing of key meiotic transcripts.

Results

RBMXL2 protein is essential for male fertility

To test how important RBMXL2 protein is for male germline development we made a conditional mouse model in which we flanked the Rbmxl2 open reading frame with LoxP sites. Since Rbmxl2 is only expressed in the testis (Elliott et al., 2000b), we chose to delete the entire Rbmxl2 open reading frame to create a null allele. We achieved this by crossing our conditional model with a mouse strain expressing Cre recombinase under control of the ubiquitous Pgk promoter (experimental details are provided in the Materials and methods). We confirmed deletion of this genomic region in homozygous Rbmxl2 gene knockout (Rbmxl2-/-) mice by Southern blotting (Figure 1—figure supplement 2) and the specific absence of the 50 KDa RBMXL2 protein from knockout testes by Western blotting (Figure 1C).

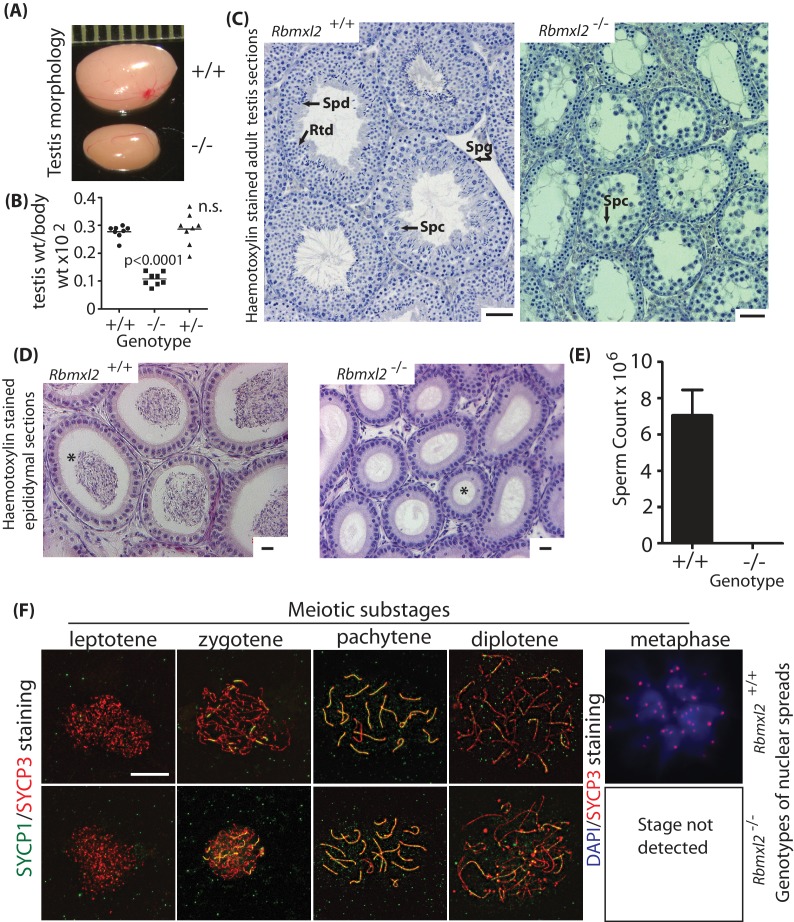

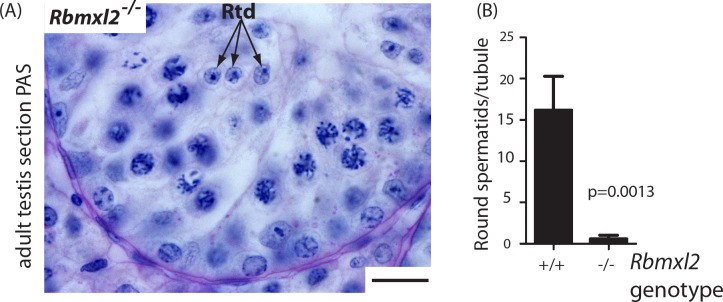

Rbmxl2-/- mice developed comparably to their wild type littermates but their testes were much smaller (Figure 2A and B). This small testis phenotype correlated with a severe disruption of testicular histology. Adult Rbmxl2-/- mice contained cells undergoing meiosis but almost no post-meiotic cells (Figure 2C, meiotic spermatocytes are abbreviated Spc, and post-meiotic round spermatids are abbreviated Rtd). The epididymis dissected from Rbmxl2-/- mice were completely devoid of sperm. Four wild type mice tested had an average of 7.07 ± 1.39×106 epididymal sperm ml−1, compared with zero in four Rbmxl2-/- mice (Figure 2D and E). No effect on female fertility was observed in Rbmxl2-/- mice (not shown).

Figure 2. RBMXL2 protein is important for mouse germ cells to progress past diplotene into metaphase I of meiosis.

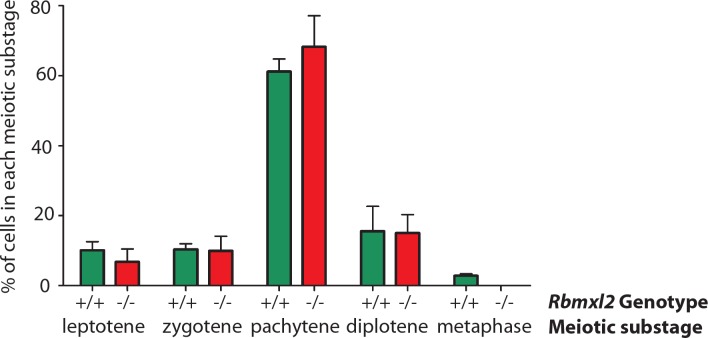

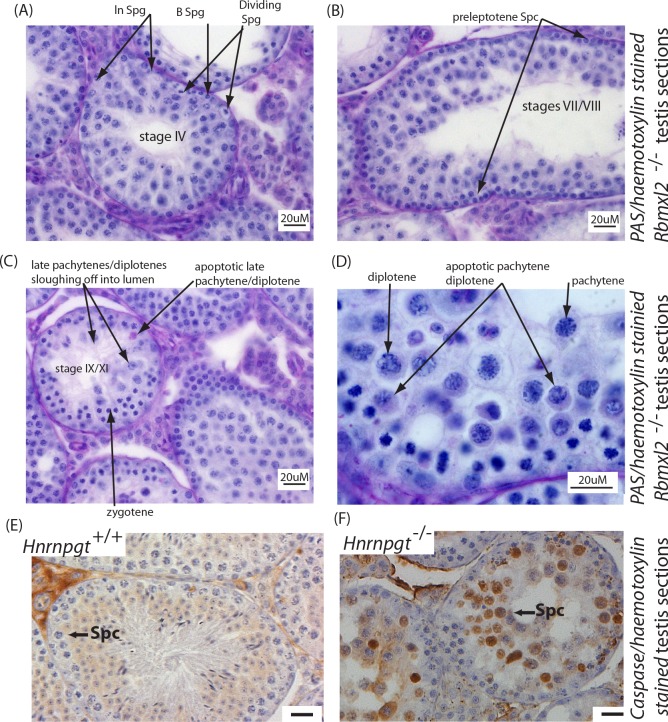

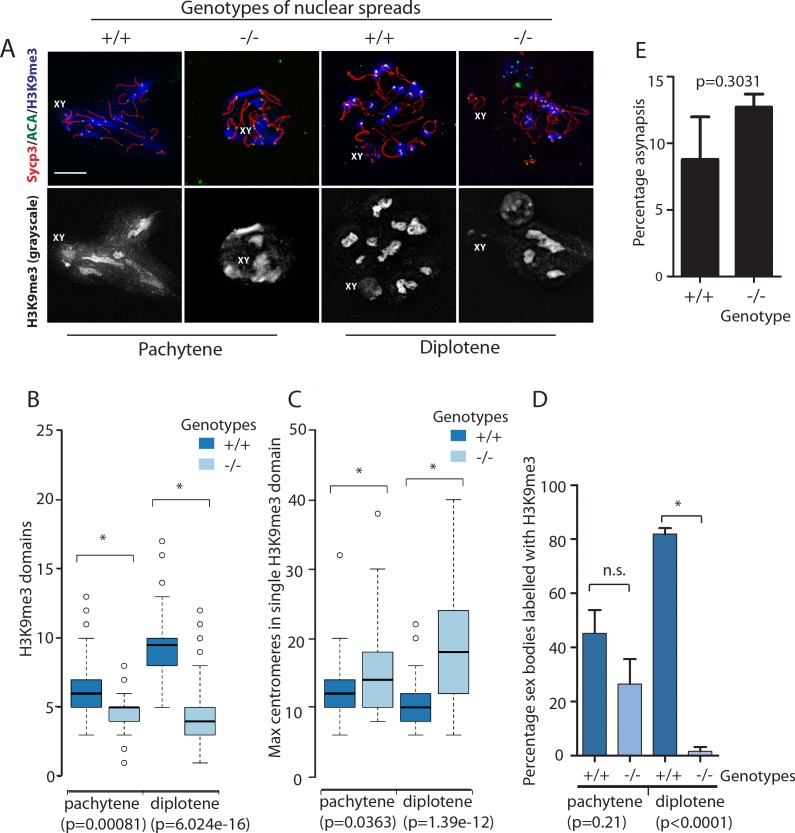

(A) Testis morphologies of adult wild type and homozygous knockout (Rbmxl2-/-) mice (scale above testes shown in millimeters). (B) Testis:body weight ratios of different genotype mice. P values were calculated using a t test. (C) Micrographs of haemotoxylin-stained testis sections from wild type and Rbmxl2-/- mice. Abbreviations: Spg, spermatogonia; Spc, spermatocyte; Rtd, round spermatid; Spd, elongating spermatid. Scale bar = 20 um. (D) Epididymis of wild type and Rbmxl2-/- mice stained with haemotoxylin and eosin. Asterisk indicates lumen (note lumen is empty in Rbmxl2-/- section indicative of azoospermia, but contains multiple cells in the wild type). Scale bar = 20 um. (E) Epididymal sperm counts of wild type and Rbmxl2-/- mice (n = 4 of each genotype). The error bar represents SEM. (F) Meiotic prophase I stages detected in wild type and Rbmxl2-/- testis chromosome spreads stained for SYCP3 (pseudocoloured red) and SYCP1 (pseudocoloured green); and DAPI and SYCP3 (pseudocoloured blue and red respectively). No metaphase I nuclei were identified in the Rbmxl2-/- testes. Quantitative data are provided in Figure 2—figure supplement 2.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Germ cells occasionally progress through meiosis into the round spermatid stage.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Graphical analysis of meiotic chromosome spreads.

Figure 2—figure supplement 3. Detailed histological analysis of Rbmxl2-/- testes.

Figure 2—figure supplement 4. Organisation of H3K9me3 staining and centromere clusters within wild type and Rbmxl2-/- mice show defects arise during pachytene but become progressively worse by diplotene.

Very rarely a few round spermatids were observed in adult Rbmxl2-/- testis sections (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A), although no elongated spermatids were detected. The presence of these round spermatids indicates that meiosis can occasionally complete in the absence of RBMXL2 protein. This is consistent with loss of RBMXL2 causing either (1) a developmental block in meiosis from which a few cells can escape; or alternatively (2) a slow attrition effect, in which the Rbmxl2-/- testis phenotype is caused by post-meiotic stages dying in the adult testis. To differentiate between these two possibilities we histologically analysed testes at 21 days postpartum (21dpp), at which point germ cells in the wild type (Rbmxl2 +/+) mice have just started to enter the post-meiotic round spermatid stage. At 21dpp there were still significantly fewer round spermatids in the Rbmxl2-/- sections compared to wild type (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B), even though there would have been less time for round spermatid cell death compared with the adult. This result thus supports a strong meiotic block in Rbmxl2-/- mice, with occasional completion of meiosis rather than a gradual attrition of round spermatids.

Most Rbmxl2-/- germ cells do not progress past meiotic diplotene

The above data demonstrate that an Rbmxl2 gene, which is conserved in all placental mammals and specifically expressed in male meiosis, is essential for mouse spermatogenesis somewhere within meiotic prophase. Staining of nuclear spreads with antibodies specific to the meiotic chromosome proteins SYCP1 and SYCP3 more precisely showed that Rbmxl2-/- mice arrest germ cell development during the diplotene substage of meiotic prophase (Figure 2F and Figure 2—figure supplement 2). Metaphase I nuclei were only detected in wild type mice and not in Rbmxl2-/- mice (N = 3 wild type and N = 3 Rbmxl2-/-testes, 180 and 138 spermatocyte nuclei scored for wild type and Rbmxl2-/- respectively). No significant differences in the frequency of earlier stages of meiotic prophase were detected between Rbmxl2-/- and wild type testes. The presence of germ cell populations up to diplotene in Rbmxl2-/- testes was further confirmed by analysis of histological sections stained with Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A–D). Staining of adult testis sections with PAS or antibodies specific to the apoptotic marker activated Caspase three further showed that adult Rbmxl2-/- germ cells die via apoptosis (Figure 2—figure supplement 3E–F).

Analysis of diplotene nuclear spreads revealed further abnormalities in the Rbmxl2-/- testis. There was a decreased number of H3K9me3-marked centromere clusters (Takada et al., 2011), with each individual cluster also containing more centromeres than in wild type testis (Figure 2—figure supplement 4A–C). H3K9me3 staining was also present at the sex body in a proportion (82%) of wild type diplotene spermatocytes, but essentially absent in mutant diplotene spermatocytes (1.5% of diplotene spermatocytes stained, 66 Rbmxl2-/- and 66 wild type nuclei scored, n = 3 for both) (Figure 2—figure supplement 4D). These defects in centromere clustering and H3K9me3 modification of the sex body were still detectable but less severe at pachytene (Figure 2—figure supplement 4D). Asynapsis was rarely observed in either control or mutant pachytene stage spermatocytes, indicating that the defect causing diplotene arrest does not significantly impact either synaptonemal complex formation or meiotic homology searching (Figure 2—figure supplement 4E) (N = 3, 109 and 94 nuclei scored for wild type and Rbmxl2-/- respectively).

In summary, the above mouse phenotype showed that deletion of the ancient RNA binding protein RBMXL2 induces progressive defects in male mouse meiotic prophase. These defects culminate with a major block during diplotene that prevents entry into metaphase I, but with defects becoming already apparent during pachytene.

Gene expression analysis of age matched wild type and Rbmxl2-/- testes

Since RBMXL2 is a nuclear RNA binding protein we predicted that the above phenotype could be associated with a primary molecular defect in generating or processing RNAs in the Rbmxl2-/- testis. To test this we analysed wild type and Rbmxl2-/- testes using RNAseq. Based on the knockout phenotype above, and because the adult wild type testis contains additional more advanced germ cells that are missing from the adult Rbmxl2-/- testis, we analysed testes at 18 days post partum (18dpp) during the first synchronised wave of mouse spermatogenesis. Such 18dpp wild type mouse testes contain germ cells between spermatogonia all the way through to diplotene, with 60% of cells engaged in meiotic prophase, but no post-meiotic cells (Bellvé et al., 1977).

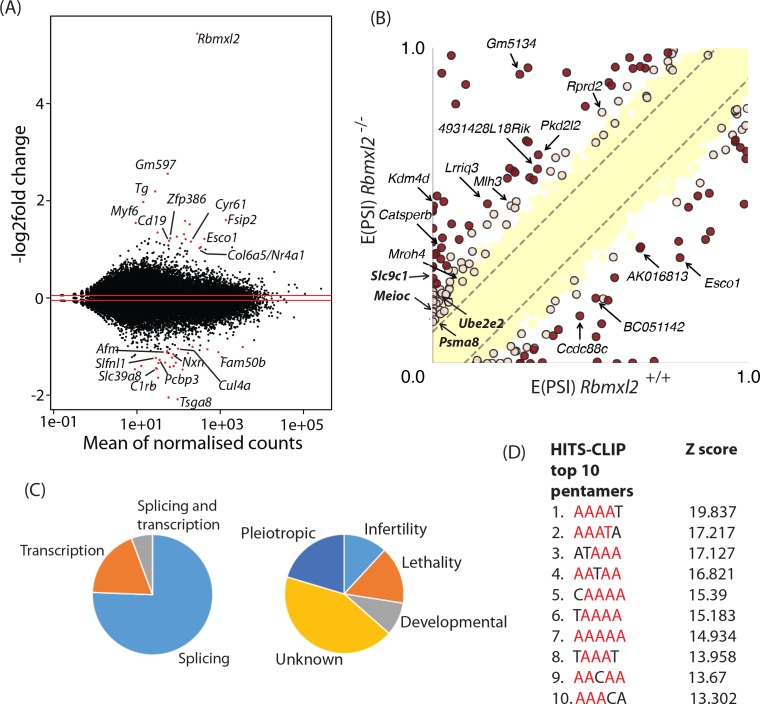

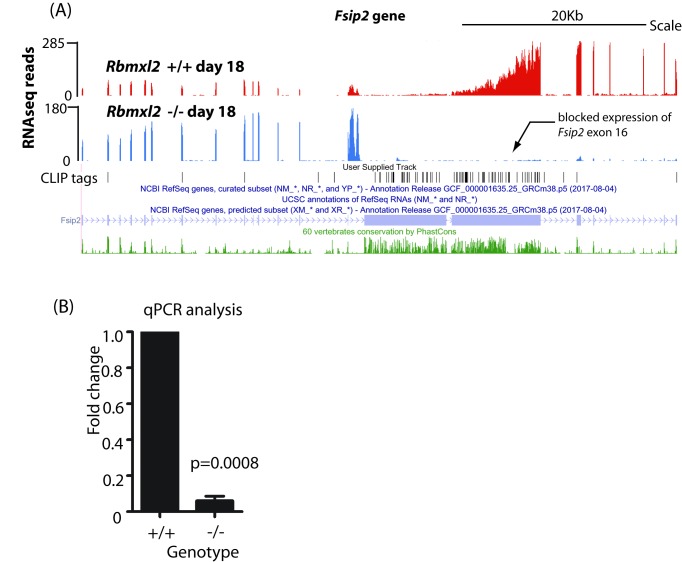

Gene expression analysis of this RNAseq data (Anders and Huber, 2010) showed overall patterns of transcription were similar between wild type and Rbmxl2-/- 18dpp testes (Figure 3A, and Figure 3—source data 1). Only 45 genes showed a fold change greater or equal to two between the wild type and Rbmxl2-/- testes, with an adjusted p value of less than 0.05, and only 23 of these changes were for known protein coding genes (Figure 3—source data 1). The strongest difference in overall gene expression between the wild type and Rbmxl2-/- backgrounds was for the Rbmxl2-/- gene itself, as expected since the Rbmxl2-/- gene is deleted from the knockout mouse. We also detected strong expression changes within the Fsip2 gene, particularly for Fsip2 exon 16 and downstream exons that were expressed only in the wild type background (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A and B). Mutations in Fsip2 correlate with defects in human sperm flagella – cellular structures which develop after meiosis (Martinez et al., 2018). RNAseq analysis detected more subtle expression changes in Cul4a, Slc9c1 and Tex15, each of which are required for mouse male fertility (Smith et al., 2018) (Figure 3—source data 1) (Kopanja et al., 2011). Genes encoding transcription factors (Myf6 and Nxn) and a signalling protein (Cyr61) that controls apoptosis (Jun and Lau, 2011) also changed expression. Mouse phenotype information at the Mouse Genome Database (MGD) (Smith et al., 2018) indicate that each of these latter three genes have important roles in normal development but not specifically of the testis (Figure 3—source data 2). Sixteen (36% of the total detected) gene expression changes in the Rbmxl2-/- testis were for predicted non coding RNAs of unknown function (Figure 3—source data 1).

Figure 3. RBMXL2 protein expression controls splicing patterns of important genes during meiosis.

(A) MAplot showing gene expression levels in 18dpp testis transcriptomes and how they change between wild type and Rbmxl2-/- mice. Genes with more than a 2-fold change in gene expression, and an adjusted p value of less than 0.05 are shown as red dots. All other genes are shown as black dots. This data given in full within Figure 3—source data 1. (B) Scatterplot showing splicing changes between the wild-type and Rbmxl2-/- testis detected by RNA-seq. The scatterplot shows expected percentage of exonic segment inclusion, or E(PSI) for wild-type and Rbmxl2-/- testis detected by RNA-seq using the bioinformatics programme MAJIQ (Vaquero-Garcia et al., 2016). Splicing changes in some genes are named and arrowed. High-confidence splicing changes (P(|ΔPSI| > V)>95%) are marked in dark red for a predicted change of V = 20%, and dark yellow for a predicted change of V = 10%, and are also listed in Figure 3—source data 2 All other quantified splice changes are in yellow (21,280 events examined). Dashed lines indicate ΔPSI of +/- 10%. (C) Left pie chart: Proportions of genes identified by RNAseq analysis to have defects at the splicing and transcriptional levels. Right pie chart: Proportions of phenotypes reported by whole gene knockout annotated for genes detected to have splicing defects in the absence of RBMXL2 protein (Smith et al., 2018) (see also Figure 3—source data 6). (D) The top 10 most frequently recovered pentamers after HITS-CLIP for RBMXL2 in the adult mouse testis (AA dinucleotides are shown in red).

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Differential expression of the Fsip2 gene in the Rbmxl2-/- testis.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. HITS-CLIP analysis of RBMXL2 in the adult mouse testis.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. RBMXL2 CLIP and motif enrichment around regulated splicing events.

RBMXL2 protein controls splicing patterns during meiosis

We carried out further bioinformatic analysis to specifically search for mis-regulated splicing events in the Rbmxl2-/- testes (Vaquero-Garcia et al., 2016). A total of 237 high-confidence, mis-regulated local splicing variations were identified in 186 genes (Figure 3B, and Figure 3—source data 3). Using RT-PCR to distinguish splice isoforms 27 of these splicing changes were experimentally tested, validating 23/27 splice isoform switches (Figure 3—source data 4). Some genes had more than one splicing event controlled by RBMXL2 (e.g. the Catsperb gene had three events). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis showed that a number of the genes regulated at the splicing level by RBMXL2 have established roles in spermatogenesis, meiosis and germ cell development (Figure 3—source data 5). However, amongst the complete set of regulated genes there was no significant enrichment of particular GO terms. This is consistent with RBMXL2 regulating splicing of a functionally diverse group of genes. Analysis of knockout phenotypes provided by the MGD (Smith et al., 2018) indicated that whole gene deletion of 25/186 RBMXL2-regulated genes cause male infertility. These latter target genes must thus have a key role in germ cell development (Figure 3C, Figure 3—source data 6, Figure 3—source data 7). Genetic deletion of some other RBMXL2 target genes cause either embryonic or neonatal lethality (33/186 genes), developmental (19/36 genes) or pleiotropic defects (43/186 genes). Cell type mis-splicing of these latter genes during meiosis could thus cause severe phenotypic effects on germ cell biology.

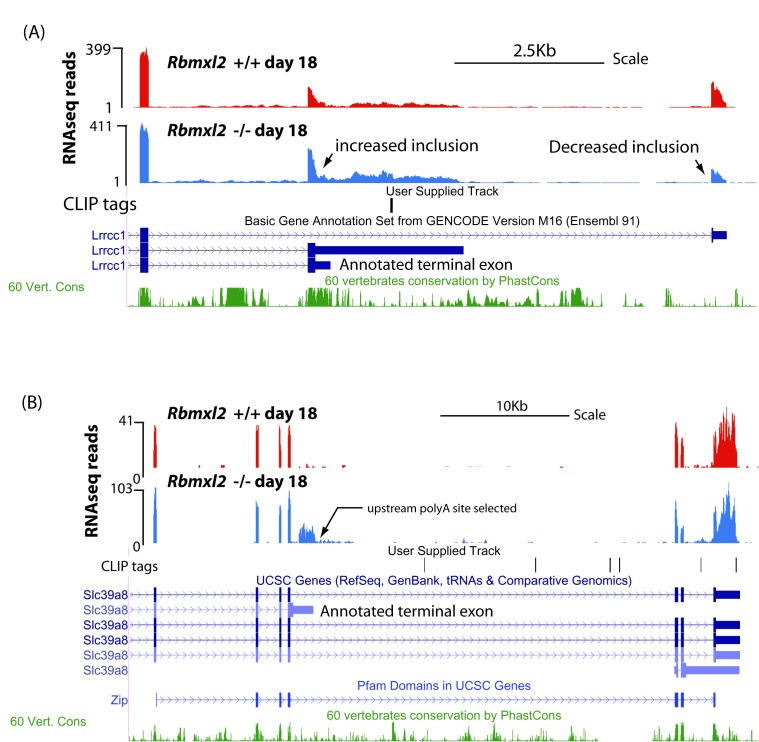

Fourteen (33%) of the genes originally identified to have changed overall expression levels between wild type and Rbmxl2-/- testes also changed splicing patterns (Figure 3C, and Figure 3—source datas 1 and 3). These included splice variants in Esco1 (encoding a protein involved in chromatid cohesion), Slc39a8 (that encodes the transporter protein responsible for cadmium toxicity in the testis) (Dalton et al., 2005); and the Slc9c1 gene (annotated on the MGD as essential for male fertility [Smith et al., 2018]).

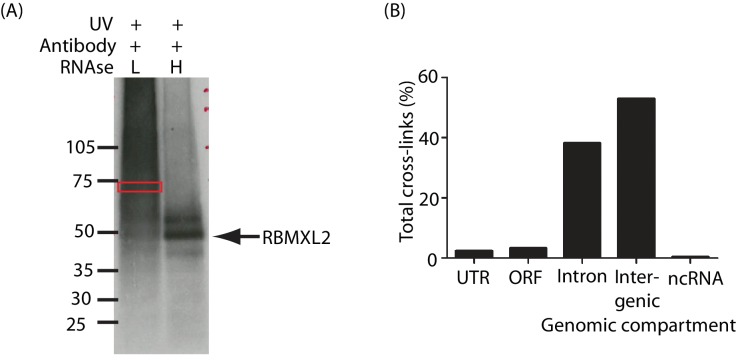

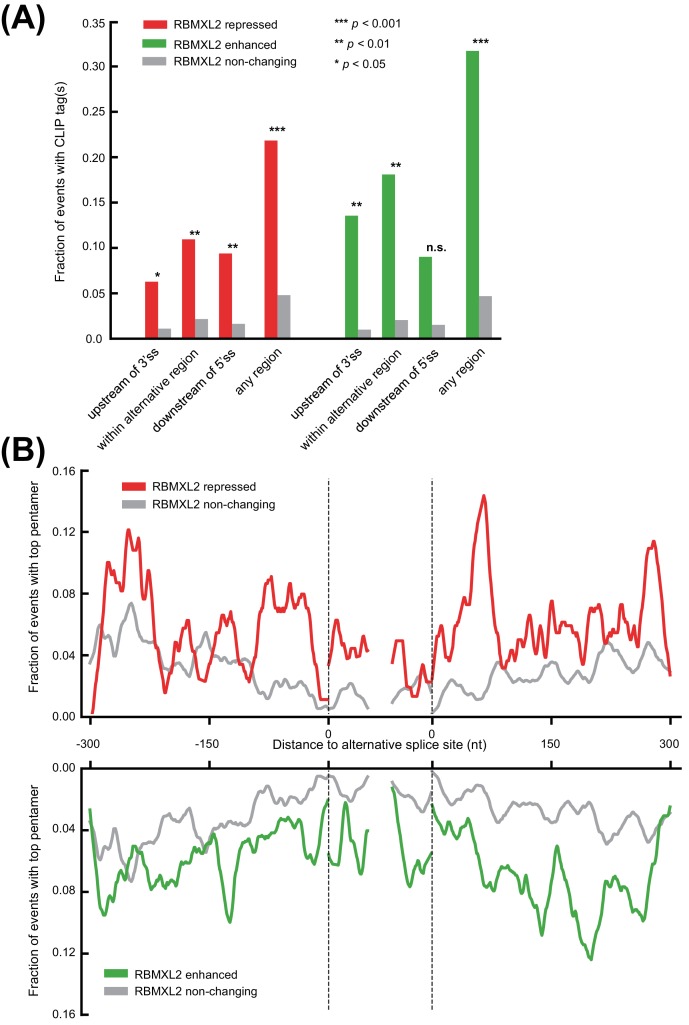

The RNA binding specificity of RBMXL2 protein was unknown. Thus we used high throughput sequencing cross linking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) to enable us to correlate splicing changes detected within the Rbmxl2-/- 18dpp mouse testis with global RBMXL2 protein-RNA interactions (Grellscheid et al., 2011). Antibodies specific to mouse RBMXL2 immuno-precipitated a radiolabelled RNA protein adduct of the known size of RBMXL2 protein (50 KDa) after treatment with high concentrations of RNase (Figure 3—figure supplement 2A) (Elliott et al., 2000b). Lower concentrations of RNase were used to retrieve an average tag length of 40 nucleotides. Enriched motif analysis of the sequenced RBMXL2 CLIP tags showed that each of the top 10 5-mers contained the dinucleotide AA (Figure 3D). Interestingly, AA is also the dinucleotide bound by RBMX (Moursy et al., 2014), which is consistent with over 90% shared sequence identity within the RRMs of these proteins (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). These intragenic cross-linked sites mapped to the mouse genome most frequently within introns, consistent with RBMXL2 being involved in nuclear RNA-processing events (Figure 3—figure supplement 2B). Next we searched for CLIP tags mapping to regions near the splicing events controlled by RBMXL2, which would suggest direct regulation. We observed enrichment of RBMXL2 binding both within alternative exon sequences and in regions proximal to regulated splice sites compared to non-regulated events (Figure 3—figure supplement 3A). Consistent with these enriched binding occurrences, motif maps of the top pentamers identified by CLIP (Figure 3D) showed regions of enrichment proximal to regulated versus non-regulated splice junctions (Figure 3—figure supplement 3B).

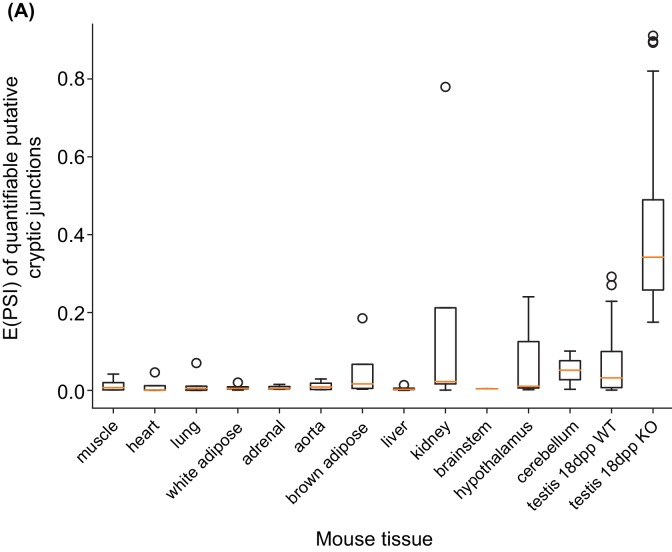

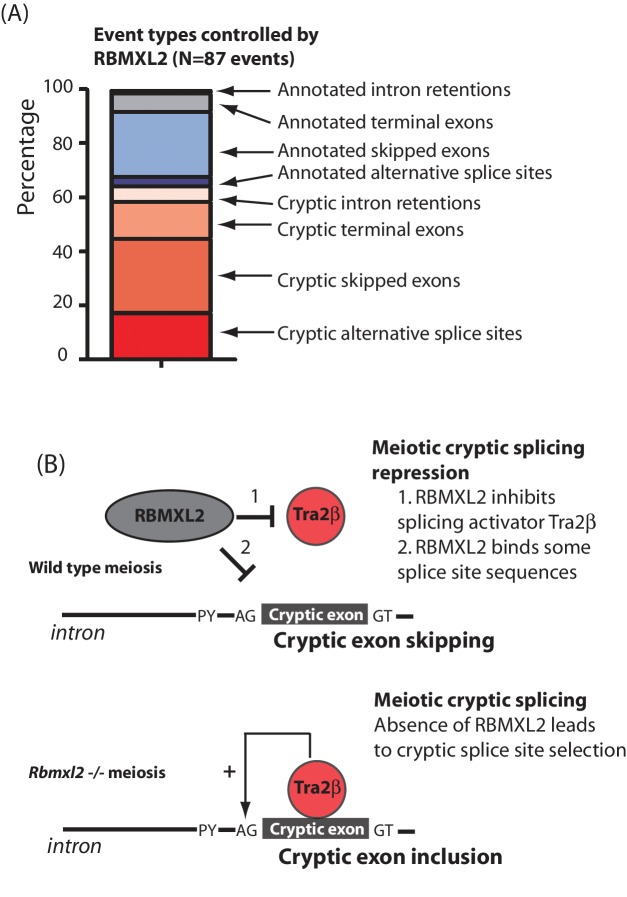

RBMXL2 protein represses splicing of exons that would compromise meiotic gene expression

Overall, the above bioinformatics analysis indicated an accumulation of defective splice isoform patterns in the Rbmxl2-/- testis. MAJIQ captures local splicing variations (LSVs) that involve both known and un-annotated (de-novo) splice sites, junctions and exons. These LSVs can correspond to both classical binary splicing events and more complex events involving three or more junctions. Since classical binary events (e.g. skipped exons) are easier to inspect and visualise with the RNAseq reads on the UCSC genome browser, we focused on the binary events for further investigation. This showed that 60% of the 87 most easily visualised classical splicing events controlled by RBMXL2 involve the altered selection of de-novo splice sites (defined as not currently annotated on the most recent build of the Mus musculus genome GRCm38/mm10, Figure 3—source data 3). These de-novo splicing variations controlled by RBMXL2 are putatively cryptic events as they insert novel internal exons that were flanked by consensus GT-AG 5' and 3' splice sites. Moreover, these de-novo splice sites showed low expected percent spliced in (E(PSI)) values in wild type 18 dpp testes and across a panel of twelve mouse tissues, further suggesting they are cryptic events only included in the absence of RBMXL2 and not in wild type mice (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). Detailed investigation indicated 84% of such cryptic exons were either not multiples of three or introduced stop codons into their mRNAs, meaning their insertion into mRNAs would disrupt protein reading frames and interfere with meiotic protein expression.

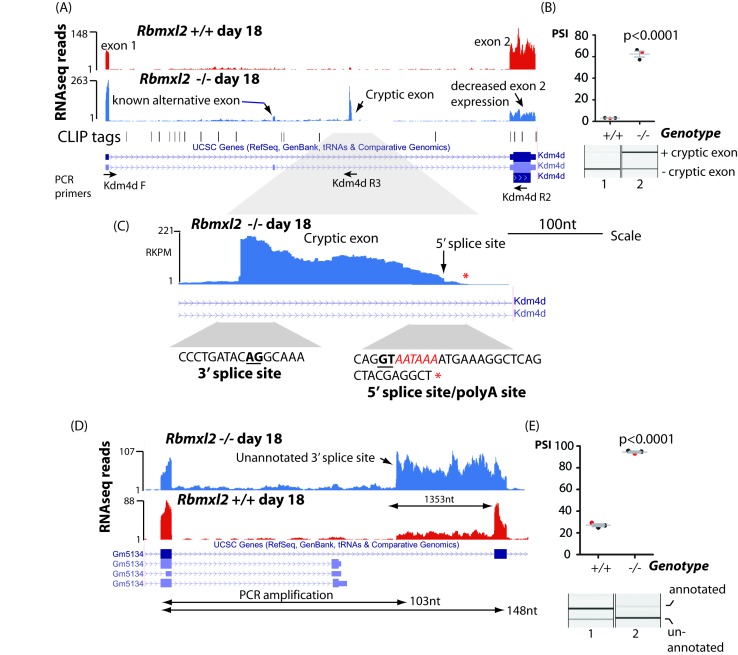

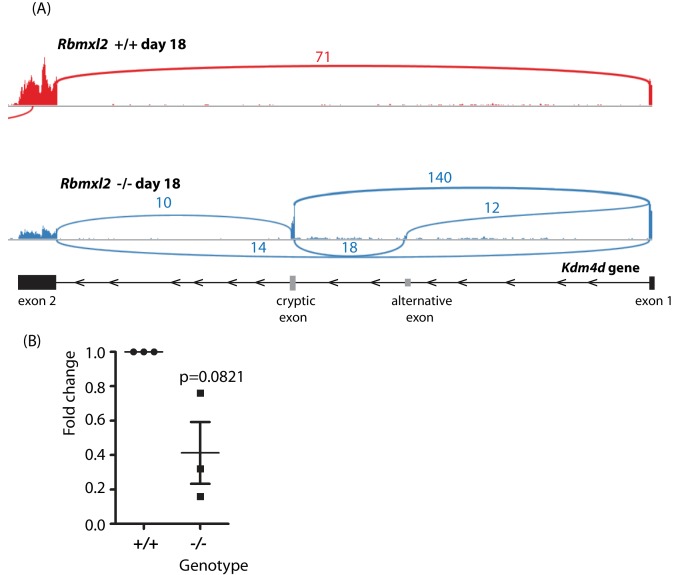

Splicing inclusion of cryptic terminal exons could also severely impact patterns of meiotic gene expression. We detected high inclusion of a cryptic terminal exon within the 5′ UTR of the Kdm4d gene (Figure 4A and B, note also increased splicing of an already annotated upstream Kdm4d alternative exon within the Rbmxl2-/- testis). We confirmed splicing inclusion of this Kdm4d cryptic exon in the Rbmxl2-/- testes using RT-PCR (primer positions are shown in Figure 4A). Kdm4d encodes a histone demethylase protein that is important for normal patterns of germ cell apoptosis in the testis (Iwamori et al., 2011). Exon two contains the entire CDS (Coding DNA Sequence, Figure 4A) of the Kdm4d gene. Analysis of exon junction read numbers using Sashimi plots confirmed different nuclear processing pathways are used for Kdm4d in wild type and knockout testes (Figure 4—figure supplement 2A). There were 14-fold more exon junction reads connecting Kdm4d exon one to the cryptic exon (140 reads), when compared to exon junction reads joining the cryptic exon to Kdm4d coding exon 2. This pattern is consistent with splicing inclusion of the cryptic exon being connected with use of an associated polyA site. Consistent with this, some individual RNAseq reads extended past the 5′ splice site of the Kdm4d cryptic exon and then terminated downstream following a consensus polyadenylation site (AATAAA) sequence (Figure 4C). Both bioinformatics analysis (Figure 3—source data 1) and qPCR (Figure 4—figure supplement 2B) detected reduced Kdm4d gene expression levels in each of 3 replicate Rbmxl2-/- testes compared to their wild type equivalents, but these trends were not statistically significant due to biological variability between individual mice. We also detected increased selection in the Rbmxl2-/- testes of another 17 splicing events that mapped to terminal exons (Figure 3—source data 3). These included an already annotated upstream terminal exon in the Lrrcc1 gene (annotated on the MGD as essential for mouse fertility) (Smith et al., 2018); and a terminal exon in the Slc39a8 gene (Figure 4—figure supplement 3A and B).

Figure 4. RBMXL2 protein represses splicing inclusion of exons that would compromise gene expression patterns.

(A) Screenshot from the UCSC genome browser (Karolchik et al., 2014) showing high inclusion levels for a novel cryptic exon in the Kdm4d gene in the Rbmxl2-/- testis transcriptome. (B) Experimental confirmation of Kdm4d splicing changes using RT-PCR and capillary gel electrophoresis (lower panel), and data from 3 Rbmxl2-/- and 3 wild type 18dpp mouse testes. Individual samples shown in the capillary gel electrophoretogram are indicated as red dots. The mean PSI is shown as a grey bar with SEM as error bar. The p value was calculated using a t test. (C) Higher resolution screenshot (Karolchik et al., 2014) of the Rbmxl2-/- testis transcriptome showing RNAseq read density in the genomic region of the Kdm4d cryptic exon. The position of the cryptic 5′ splice site is indicated by a red arrow. Splice junction sequences are shown underneath with the consensus polyadenylation site AATAAA in red. Some RNAseq reads terminate downstream of the Kdm4d cryptic exon 5′ splice site. The final RNAseq read coverage detected downstream of this exon is shown as a red asterix. (D) UCSC genome browser screenshot (Karolchik et al., 2014) showing increased splicing selection of an cryptic 3′ splice site within the Gm5134 mRNA in the Rbmxl2-/- testis transcriptome. (E) Chart showing experimental confirmation of the splicing switch in the Gm5134 gene in 3 Rbmxl2-/- and 3 wild type 18dpp mouse testes. The individual samples shown in the capillary gel electrophoretogram are shown in the chart as red dots.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Distribution of putative cryptic splice sites across a panel of mouse tissue samples.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. (A) Sashimi plots of Kdm4d gene in the Rbmxl2-/- and Rbmxl2 +/+ mice.

Figure 4—figure supplement 3. Examples of genes that select upstream terminal exons in the Rbmxl2 -/- testis.

In addition to splicing of entire cryptic exons, loss of RBMXL2 protein also activated splicing selection of individual cryptic 5′ and 3′ splice sites within introns that increased the length of already annotated exons (Figure 3—source data 3). This kind of changed splicing pattern was observed for the Gm5134 mRNA that encodes a solute transporter important for normal metabolism (Figure 4D and E). The aberrant splice isoform of the Gm5134 transcript made in the Rbmxl2-/- testis uses a cryptic 3′ splice site within intron 10, increasing the size of exon 11 by 1353nt.

RBMXL2 protein is important to prevent mis-splicing of long exons in key genes during meiosis

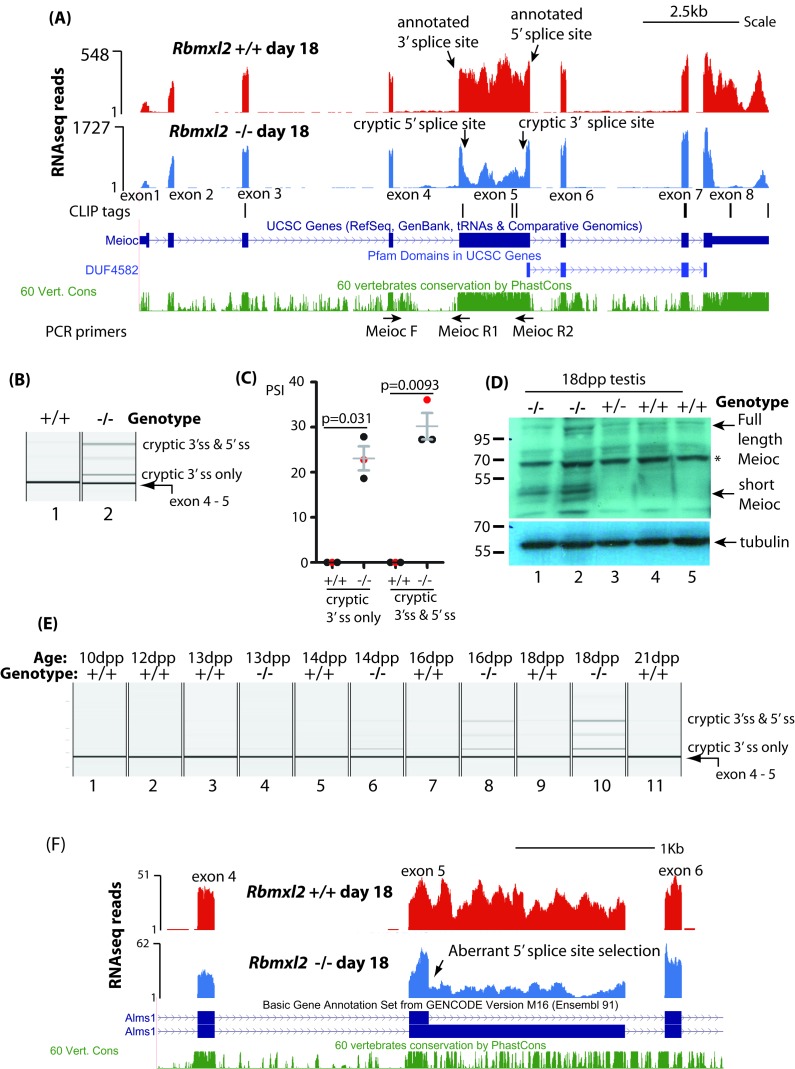

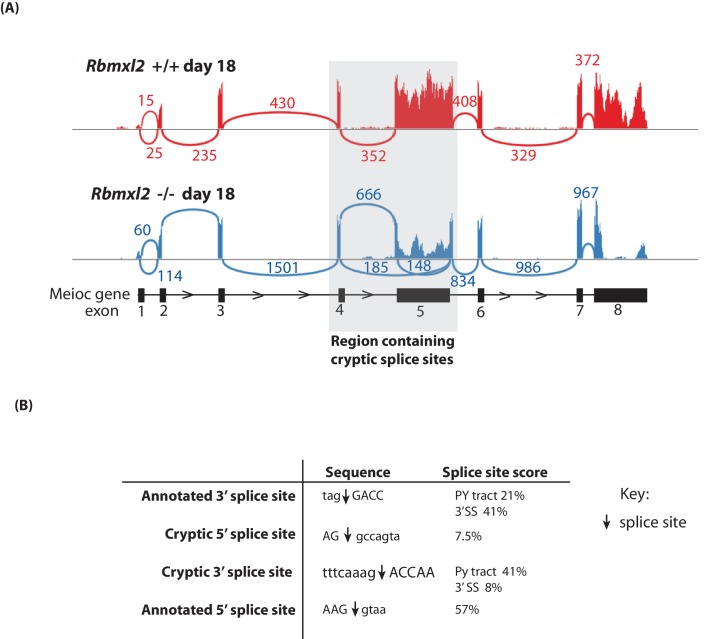

As well as cryptic splice sites within introns, some exon-located cryptic splice sites were activated within the Rbmxl2-/- testes, including within genes important for testis development (Figure 3—source data 6). Amongst the genes known to be important for meiosis, we observed a dip in RNAseq density for the interior of Meioc (meiosis specific gene with coiled coil domain) exon five in the Rbmxl2-/- testis transcriptome (Figure 5A) (Abby et al., 2016; Soh et al., 2017). This dip in RNAseq read density was caused by high levels of cryptic splice site activation within Meioc exon 5. Sashimi plots showed that in the Rbmxl2-/-testes ~ 28% of the splice junctions joined Meioc exon four to an exon-internal cryptic 3′ splice site within Meioc exon 5 (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A). A further cryptic 5′ splice site within Meioc exon five was also used in 22% of the Rbmxl2-/- testis transcripts. Use of both cryptic splice sites converted Meioc exon five into an exitron (an exon with internal splice sites) (Marquez et al., 2015; Sibley et al., 2016). RT-PCR analysis confirmed both these defective Meioc exon five splicing patterns within the Rbmxl2-/- testes (Figure 5B–C).

Figure 5. RBMXL2 protein is important to prevent splicing of long exons becoming disrupted during meiosis.

(A) Screenshot from the UCSC genome browser (Karolchik et al., 2014) showing splicing pattern of Meioc exon five in wild type and Rbmxl2-/- testis. RNAseq read density from Rbmxl2-/- testis are shown in blue; RNAseq read density from wild type testis in red; the genomic positions of HITS-CLIP tags are mapped underneath. Splice sites for exon five are arrowed, and the binding sites for RT-PCR primers are shown. (B) Representative capillary gel electrophoretogram showing RT-PCR validation of the changing Meioc splicing pattern. This RT-PCR analysis used three primers in multiplex (MeiocF- MeiocR1 detects splicing of exon 4 to exon 5, and MeiocF-MeiocR2 detects splicing from exon four to the cryptic 3′ splice site within exon 5, or splicing of exon 4 to exon five after complete exitron removal. Detection of full length Meioc exon five inclusion by this latter primer combination is precluded by the large size of the amplicon. (C) Chart showing percentage splicing inclusion (PSI) of different splice variants of Meioc exon 5. PSI data were generated by RT-PCR from three wild type (WT) and 3 Rbmxl2-/- mice, with the individual samples shown in the capillary gel electrophoretogram in part (B) indicated as red dots. Error bars represent the SEM, and p values were calculated using t tests. (D) Western blot of 18dpp mouse testes protein probed with an antibody specific to Meioc protein (Abby et al., 2016). A non-specific protein that was also detected in mouse spleen as well as 18dpp testis is indicated by an asterisk. (E) Capillary gel electrophoretogram showing patterns of Meioc exon 5 splicing between 10dpp and 21dpp in the first wave of mouse spermatogenesis. (F) UCSC screenshot (Karolchik et al., 2014) showing that splicing of Alms1 exon five is disrupted in Rbmxl2-/- testes via selection of an internal 5′ splice site.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Further splicing analysis of the Meioc gene.

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. Further splicing analysis of the Meioc gene.

The cryptic splice sites within Meioc exon five are hardly ever used in the wild type 18dpp testis transcriptome. In silico analysis showed that the internal cryptic 5′ splice site within Meioc exon five is weak compared to 5′ splice sites for other known alternative exons (7.5th percentile by SROOGLE, compared to 57th percentile for the downstream annotated 3′ splice site (Figure 5—figure supplement 1B) (Schwartz et al., 2009). The first two nucleotide positions downstream of the Meioc exon 5- cryptic internal 5′ splice site are GC, so diverge from the GT consensus which is found flanking almost all eukaryotic introns. Similarly, the cryptic internal 3′ splice site within Meioc exon five is relatively weak (8th percentile of the average 3′ splice site strength for an alternative exon, compared to 41st percentile for the upstream annotated 3′ splice site). Meioc exon five is also directly bound by RBMXL2 protein, evidenced by three internal HITS-CLIP tags (Figure 5A). These include a CLIP tag directly overlapping the Meioc exon 5 internal cryptic 5' splice site, as well as CLIP tags upstream of the internal 3′ splice site.

Meioc exon five is highly conserved across species suggesting it encodes a functionally important part of Meioc protein (Figure 5A). Exitrons frequently modify protein coding capacity of mRNAs by removing peptide coding segments from mRNAs (Marquez et al., 2015; Sibley et al., 2016). Both the cryptic splicing events in Meioc exon five remove RNA segments within the Meioc CDS that are multiples of 3. These events shorten the CDS just upstream of but largely not including the coding information for the MEIOC domain itself (http://pfam.xfam.org/family/PF15189). We thus predicted that a shorter Meioc protein isoform may be produced in the Rbmxl2-/- testis. Consistent with this, Western blotting with a Meioc specific antiserum (Abby et al., 2016) detected a 40–50 KDa Meioc protein within the Rbmxl2-/- testis, but not in wild type or heterozygote Rbmxl2 ±testes (Figure 5D). This 40–50 KDa molecular weight corresponds to an expected Meioc protein size following complete exitron removal. Although shorter Meioc protein isoforms were only detected in the Rbmxl2-/- testes, in each genotype we detected a protein doublet just above 100 KDa corresponding to the reported size of full length Meioc protein (Abby et al., 2016) (Figure 5D).

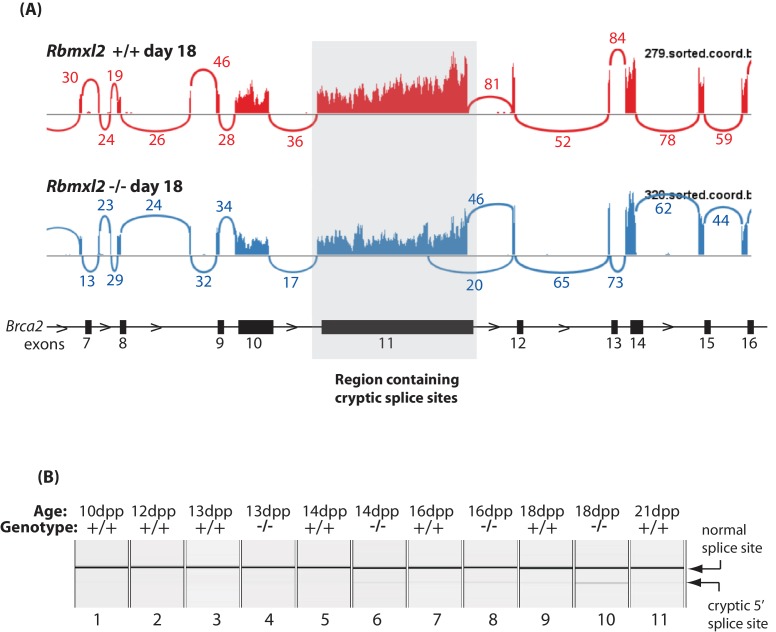

We further analysed splicing patterns during the first wave of mouse spermatogenesis to test whether appearance of the Meioc splicing defects corresponded with the known expression window of RBMXL2 protein in meiotic prophase (Ehrmann et al., 2008). Aberrant splice isoforms of Meioc exon five only appeared within Rbmxl2-/- testes from 14dpp, and were barely visible at any time point within similar age wild type testes. We performed similar experiments to analyse the dynamics of Brca2 splicing in the first wave of mouse spermatogenesis. The RNAseq data predicted utilisation of an upstream cryptic 5′splice site within the 4809 nucleotide Brca2 exon 11 (Figure 3—source data 3) that removes 1263 nucleotides from Brca2 exon 11 in the Rbmxl2-/- testes (Figure 5—figure supplement 2A). RT-PCR analysis during the first wave of spermatogenesis showed Brca2 exon 11 splicing was normal at 13dpp in the Rbmxl2-/- testes, with defects appearing only during and after 14dpp (Figure 5—figure supplement 2B). These time-course data indicate that splicing defects in both Meioc and Brca2 appear and become progressively worse during meiotic prophase in the Rbmxl2-/- testes within genes that are expressed and processed normally in earlier germ cell types. An implication of this is that the aberrant splice isoforms detected in 18dpp whole testis RNA must be significantly diluted by signals from germ cells from earlier developmental stages.

Other unusually long exons in genes important for germ cell development were also mis-spliced in the Rbmxl2-/- testes including exons in the Alms1 and Esco1 genes (Figure 3—source data 3). The Alms1 gene encodes a protein involved in microtubule organisation during cell division, and its knockout disrupts spermatogenesis resulting in a small testis phenotype (Smith et al., 2018). In the Rbmxl2-/- testis an upstream 5′splice site is selected within Alms1 exon 5, which is is unusually long at 1546nt (Figure 5F). This splice switch removes 1407 nucleotides from the Alms1 mRNA, and coding information for 469 amino acids from the predicted Alms1 reading frame.

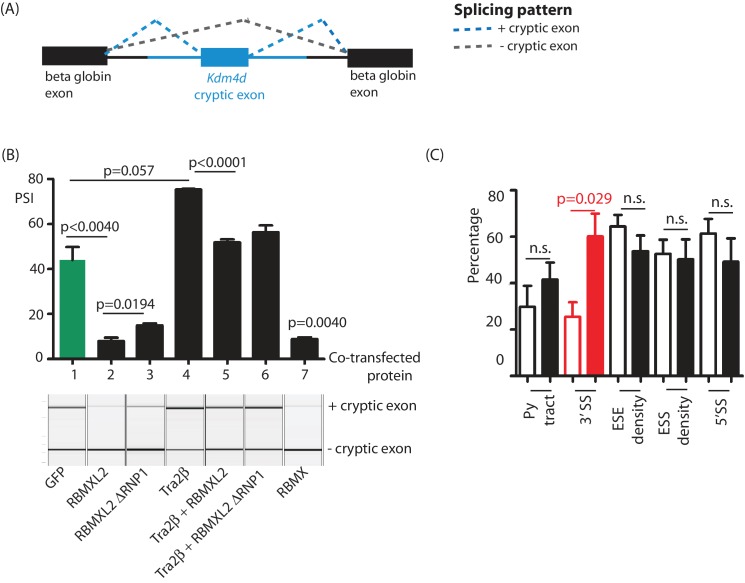

Ectopic expression of RBMXL2 protein represses cryptic exon splicing in vitro

The above data indicate that loss of RBMXL2 protein within spermatocytes activates utilisation of cryptic splice sites. We next tested if cryptic splice site selection would be reciprocally repressed by ectopic expression of RBMXL2 protein. The genomic region spanning the Kdm4d cryptic exon and its flanking intron sequences were cloned into a minigene (Figure 6A). We detected ~40% splicing inclusion of the cryptic Kdm4d exon after co-transfection of this minigene into HEK293 cells (that do not normally express RBMXL2) with an expression vector encoding GFP (Figure 6B lane 1). Levels of Kdm4d cryptic exon splicing inclusion were repressed 6-fold upon co-transfection of a construct encoding an RBMXL2-GFP fusion protein. We also tested the activity of an RBMXL2 fusion protein without the RNP1 motif of the RRM (RBMXL2 ΔRNP1). Consistent with RNA-protein contacts not being critical for splicing repression of this cryptic exon, RBMXL2 ΔRNP1 could still repress Kdm4d cryptic exon splicing, although slightly less efficiently than the full length RBMXL2 fusion protein. Interestingly, splicing of the Kdm4d cryptic exon was also efficiently silenced by ectopic co-expression of an RBMX-GFP fusion protein (Figure 6B lane 7).

Figure 6. Ectopic expression of RBMXL2 protein represses cryptic exon splicing in vitro.

(A) Schematic of the Kdm4d minigene, in which the Kdm4d cryptic exon and flanking introns (shown in blue) are inserted between two beta globin exons in the vector pXJ41 (Bourgeois et al., 1999). (B) Bar chart (upper panel) showing data from biological triplicate experiments after quantitation using capillary gel electrophoresis (n = 3 for each transfection). Capillary gel electrophoretogram (lower panel) showing splicing patterns in HEK293 cells. The minigene containing the Kdm4d cryptic exon and flanking intron sequences were transfected with expression plasmids encoding either GFP, RBMXL2, RBMXL2 ΔRNP1, Tra2β, RBMX or combinations of these. Splicing patterns were analysed using RT-PCR. (C) Bar chart showing average annotated and cryptic splice site strengths from a panel of internal cryptic exons that were activated in Rbmxl2-/- testes. Splice site strengths were quantitated as a percentile of the average value for an alternative exon using Sroogle (Schwartz et al., 2009). Open bars show percentile values for cryptic exons, shaded bars (black or red) show percentile values for downstream exons. Error bars represent the SEM, and p values were calculated using t tests.

The above results show that RBMXL2 represses Kdm4d cryptic exon splicing, and is consistent with RBMXL2 providing a direct functional replacement for RBMX during meiosis. iCLIP experiments in adult mouse testis further identified the Kdm4d cryptic exon as directly binding the splicing activator protein Tra2β (Dalgliesh and Elliott, unpublished data). Consistent with this, Tra2β over-expression in HEK293 cells strongly increased Kdm4d cryptic exon splicing inclusion (Figure 6B lane 4). Ectopic activation by Tra2β indicated that although this Kdm4d exon cryptic exon is effectively ignored by the spliceosome in wild type testis, cryptic exon splicing is activated in response to increased expression of a splicing activator protein. Importantly, splicing activation by Tra2β was efficiently supressed when the minigene was co-transfected at the same time with both RBMXL2 and Tra2β (Figure 6B, lanes 5 and 6).

We addressed if other cryptic exons repressed by RBMXL2 might also possess the capacity to be activated by splicing regulators that bind to their associated splicing enhancer sequences. In silico analysis (Schwartz et al., 2009) of a panel of cryptic exons that were activated in the Rbmxl2-/- testes showed that these exons had significantly weaker 3′ splice sites, but similar Exonic Splicing Enhancer (ESE) sequence content compared to their immediately adjacent downstream exons (Figure 6C). These other cryptic exons that are repressed by RBMXL2 may be likewise poised for splicing during meiosis, because they bind to splicing activator proteins such as Tra2β.

Discussion

This study finds that loss of the ancient RBMXL2 protein completely prevents sperm production in the mouse, largely because of a developmental block during meiosis. Rbmxl2-/- mouse germ cells develop as far as meiosis, thus escaping the major developmental checkpoints that operate during meiotic pachytene (de Rooij et al., 2003), but then undergo cell death by apoptosis after reaching diplotene. Our data further show that RBMXL2 protein is important to protect the meiotic transcriptome from a spectrum of splicing defects (Figure 7A). These include classic manifestations of cryptic splicing that would be strongly deleterious to gene expression (Marquez et al., 2015; Sibley et al., 2016), such as insertion of novel cryptic exons and premature polyadenylation sites that would disrupt protein coding sequences, and the selection of cryptic splice sites that would shorten or extend exon lengths. Previous work reporting poor conservation of splicing patterns between species suggested that alternative splicing might not control fundamental aspects of germ cell biology (Kan et al., 2005). In contrast, the work presented here suggest a generic requirement for cryptic splice site suppression during meiosis that could explain the conservation of an Rbmxl2 gene in all placental mammals, even if individual cryptic splice sites are not conserved between species’ genomes (Elliott et al., 2000b).

Figure 7. RBMXL2 protein is needed to enable production of proper splice isoform patterns during meiosis.

(A) Stacked bar chart summarising percentage types of splicing event mis-regulated in the Rbmxl2-/- testes. Details of the individual genes contributing to this list are given in Figure 3—source data 3. (B) Models for RBMXL2 function. In wild type mice, RBMXL2 protein may block cryptic exon splicing through: 1. Inhibition of splicing regulator proteins including Tra2β protein via protein-protein interactions (Venables et al., 2000); or 2. Direct RNA protein interactions of RBMXL2 with important splicing regulatory sequences in the pre-mRNA. In the Rbmxl2-/- background the absence of this buffering would result in an increase in splicing inclusion of some cryptic exons which contain Tra2β binding sites.

Cells in meiotic prophase might be particularly susceptible to cryptic splice site poisoning because of their high levels of transcription, altered splicing regulator expression and relaxed chromatin environments (de la Grange et al., 2010; Licatalosi, 2016; Soumillon et al., 2013; Pan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008; Clark et al., 2007; Grosso et al., 2008; Yeo et al., 2004). In silico data suggest that the cryptic exons repressed by RBMXL2 would be poised for splicing inclusion in conditions of high concentrations of splicing activators because of their strong ESE contents. We suggest a model where RBMXL2 protein may buffer the activity of splicing activator proteins to prevent such cryptic splice site selection from happening in meiosis (Figure 7B). This model is also consistent with previously reported data showing that RBMXL2, RBMX and RBMY proteins physically interact with and antagonise the splicing activity of Tra2β and SR proteins (Liu et al., 2009; Nasim et al., 2003; Venables et al., 2000; Elliott et al., 2000a) (Figure 7B). Data presented in this study also show that Kdm4d cryptic exon splicing activation by Tra2β is blocked in vitro by co-expression of RBMXL2. As an alternative and not mutually exclusive model, RBMXL2 protein-RNA binding may sterically block recognition of some cryptic splice sites during meiosis, including the cryptic 5′ splice site within Meioc exon five which was utilised in the Rbmxl2-/- testis (Figures 5A and 7B). However, no HITS-CLIP tags for RBMXL2 were detected near the Kdm4d cryptic exon. Furthermore, a version of RBMXL2 deleted for the key RNP1 motif involved in RNA-protein interactions could still repress Kdm4d cryptic exon splicing (albeit slightly less efficiently than the wild type RBMXL2 protein). Thus buffering protein interactions between RBMXL2 and proteins like Tra2β may be potentially more important in repressing cryptic splicing in meiosis than direct RBMXL2 RNA-protein interactions.

Loss of RBMXL2 disrupts expression of many downstream target genes in parallel, both at splicing and transcriptional levels. This makes it difficult to resolve whether the phenotype detected in the Rbmxl2-/- mouse testes is caused by aberrant expression of a single target RNA, or is a compound phenotype involving multiple genes. Some genes affected by RBMXL2 protein deletion are annotated as important for spermatogenesis on the MGD (Smith et al., 2018). These include Alms1 (Arsov et al., 2006; Collin et al., 2005); Brca2 which is required for meiotic prophase (Sharan et al., 2004); Kdm4d, which helps control apoptosis during male germ cell development (Iwamori et al., 2011); and Cul4a that encodes an important ubiquitin ligase needed for DNA damage response. Two factors complicate direct comparison of MGD phenotypes with those after RBMXL2 knockout. Firstly, conventional knockouts will report a phenotype the first time a gene is needed in a developmental pathway. In contrast RBMXL2 is only expressed from the onset of meiosis, so any defects in target gene expression that occur without RBMXL2 could result in a later phenotype. For example, Meioc knockout phenotype analysis has concentrated on entry into meiosis (Abby et al., 2016; Soh et al., 2017). Our data show that Meioc exon five is still spliced normally on meiotic entry in the Rbmxl2-/- mouse (at 12dpp), but becomes compromised later on during meiotic prophase (when RBMXL2 is expressed). It is possible that Rbmx and Rbmy will provide an equivalent function to Rbmxl2 in spermatogonia and early spermatocytes, and that it is only when meiotic sex chromosome inactivation initiates during pachytene that germ cells will depend on Rbmxl2. Consistent with this, in transfected cells RBMX was able to suppress a cryptic splice exon in the Kdm4d with similar efficiency to the RBMXL2 protein. Secondly, the MGD phenotype data (Smith et al., 2018) is after gene knockout, whereas Rbmxl2 deletion changes patterns of splice isoforms.

High levels of gene expression and alternative splicing have also been observed in the nervous system, and this is another anatomic site where pathological cryptic exon inclusion has been reported. Neuronal cryptic exon inclusion occurs following depletion of the splicing repressor protein TDP43, and might contribute to neuron death in neurological diseases like ALS and Alzheimer’s disease (Sun et al., 2017). Cryptic splicing has also been observed in cultured human cells after depletion of the splicing repressor proteins hnRNP C, hnRNPL and PTB (Ling et al., 2016; McClory et al., 2018; Zarnack et al., 2013), and in mouse oocytes depleted for the splicing factor SRSF3 (Do et al., 2018). Taking all these results into consideration we suggest that RBMXL2 has a key role controlling the meiotic transcriptome, and suggest that human male infertility caused by loss of RBMXL2 or its paralog RBMY may be associated with germ cell type-specific cryptic splicing.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource |

Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene (M. musculus) | Rbmxl2 | |||

| Strain, strain background (M. musculus) |

C57Bl/6 | |||

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) |

Rbmxl2 knockout | this publication | ||

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) |

FlpE | Rodríguez et al., 2000 | ||

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) |

PGKcre | Lallemand et al., 1998 | ||

| Cell line (H. sapiens) | HEK293 | |||

| Antibody | Sheep polyclonal anti-Rbmxl2 |

Ehrmann et al. (2008)

|

(1:700) | |

| Antibody | Guinea pig polyclonal anti-Meioc |

Abby et al. (2016)

|

(1:1000) | |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin |

Sigma | catalog number T6793 |

(1:1000) |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH |

Abgent, San Diego CA | catalog number AP7873b |

(1:1000) |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase 3 |

Proteintech | catalog number 25546–1-AP |

(1:100) |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-Sycp3 |

Life span | Cat# LS-B175, RRID:AB_2197351; lot#73619 |

(1:500) |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-Sycp3 [Cor 10G11/7] |

Abcam | Cat#ab97672 RRID:AB_10678841; lot#GR282926-1 |

(1:500) |

| Antibody | Guinea Pig polyclonal anti-Sycp1 |

Laboratory of Howard Cooke |

(1:200) | |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-phospho H2AX [JBW301] |

Millipore | Cat# 05–636, RRID:AB_309864; lot#1997719 |

(1:3000) |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-H3 trimethyl K9 |

Abcam | Cat# ab8898, RRID:AB_306848; lot# GR250850-2 |

(1:500) |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-H3 phospho (Ser10) |

Abcam | Cat# ab14955, RRID:AB_443110; lot# GR192274-8 |

(1:1000) |

| Antibody | Human polyclonal anti-Centromere Protein |

Antibodies Incorporated | Cat#15-235-0001 | (1:50) |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-AcSmc3 |

From Katsuhiko Shirahige, University of Tokyo. Nishiyama et al. (2010) |

(1:1000) | |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 488 |

Invitrogen | Cat# A11001 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 |

Invitrogen | Cat#A11008 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Human Alexa Fluor 488 |

Invitrogen | Cat# A11013 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Guinea Pig Alexa Fluor 488 |

Invitrogen | Cat# A11073 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 594 |

Invitrogen | Cat# A11005 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 |

Invitrogen | Cat# A11012 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 |

Invitrogen | Cat# A32733 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Guinea Pig Alexa Fluor 647 |

Invitrogen | Cat# A21450 | (1:500) |

| Dye | DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) |

Biotium | Cat# 40043; lot# 15D1117 |

|

| Recombinant DNA reagent |

PXJ41 Kdm4d | this paper | ||

| Sequence-based reagent |

primers | this paper | designed using Primer3 http://primer3.ut.ee/ |

|

| Sequence-based reagent |

qPCR primers | this paper | designed using Primer3 http://primer3.ut.ee/ |

|

| Commercial assay or kit |

Rnaeasy plus kit | Qiagen | catalog number 74134 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

DNA free | Ambion | catalog number AM1906 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

Superscript Vilo | Invitrogen | catalog number 11754 | |

| Chemical compound, drug |

Bouins | Sigma | catalog number HT10132 | |

| Software, algorithm | Graphpad prism | https://graphpad.com | ||

| Software, algorithm | Sroogle | http://sroogle.tau.ac.il/ |

Generation of KO mice

A targeting construct in which the Rbmxl2 open reading frame was flanked by LoxP sites was made using standard molecular biology techniques, and electroporated into ES129 cells. Positive clones were injected into blastocysts to create chimaeras, and bred to yield agouti pups heterozygous for the targeted locus (Ozgene, Perth, Australia). The original mice containing the Neomycin gene (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A) were crossed to FlpE mice to remove the Neo gene and to generate the Rbmxl2 LoxP conditional allele (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B). Mice containing the Rbmxl2 LoxP conditional allele were crossed with mice expressing PGKCre, resulting in deletion of the Rbmxl2 reading frame (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C). Genetic structures of the wild type and targeted alleles were confirmed by Southern blotting. Genomic DNA was prepared from mouse tails, cut with BamHI, run on an agarose gel and blotted onto a Hybond N nylon membrane (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Blots were probed using an internal probe Enp (generated using primers enpF 5′-ACTGTTGATTCCCCTTCCAAC-3′ and enp R 5′- ACTCCTGCCTGTGATTGGTC-3′, and α- 32 P labelled by random priming). The correct insertion of the targeting vector in the genome was confirmed by cutting genomic DNA with PshA1 and EcoRV and hybridizing with 5′ (generated from genomic DNA using 5′-agcattcagcaaaggctcac-3′ and 5′- ttaaaactgagggagactgc-3′) and 3′ (generated from genomic DNA using 5′-actgcatagttgtagccatc-3′ and 5′- tgcattctctttaggctcatttc-3′) probes respectively.

Animal work

Animal research was carried with the approval of the Newcastle University animal research ethics committee and the UK Government Home Office (Home Office project Licence Number PIL 60/4455).

Analysis of mouse germ cell development in vivo

Testis/body weight ratios, and sperm counts were measured on a C57Bl6 background. In order to determine sperm counts, the cauda epididymis was dissected in PBS and the sperm were counted in a haemocytometer.

Preparation of RNA for RNA-Seq

Mice were back crossed onto the C57Bl6 background for eight generations, and we used back crossed male mice for subsequent analysis. Testes were homogenized in RLTplus buffer from Qiagen before purification with the Rneasy plus kit (Qiagen, 74134). The RNA was then re-purified with the kit before Dnase digestion (Ambion).

RNA-Seq analysis

Paired-end sequencing was done for six samples in total (three biological replicates of 18dpp wild-type and Rbmxl2-/- testis) using 75 bp reads. Libraries were prepared using TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) and sequenced; 75 bp single reads were sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina, using the mid output v2 150 cycles kit). The base quality of the raw sequencing reads were checked using FastQC. Trimmomatic (v0.32) was used to remove adapters and to trim the first twelve bases and the last base at position 76 (Bolger et al., 2014). Reads were aligned to the UCSC D3c. 2011 (GRCm38/mm10) assembly of the mouse genome using STAR (v2.5.2b) (Dobin et al., 2013). Alternative splicing events were assessed using MAJIQ and VOILA software packages (Vaquero-Garcia et al., 2016). Briefly, uniquely mapped, junction-spanning reads were used by MAJIQ to construct splice graphs for transcripts from a custom Ensembl transcriptome annotation and to quantify PSI (within conditions) and ΔPSI (between conditions) for all local splicing variations (LSVs). The captured LSVs include classical alternative splicing events (e.g. cassette exons, alternative 5’ splice sites, etc.) as well as more complex variations (Vaquero-Garcia et al., 2016). LSVs with an expected change of greater than 10% were then visualized using VOILA to produce splice graphs, violin plots representing PSI and ΔPSI quantifications, and interactive HTML outputs for changes between wild type and Rbmxl2-/-.

In silico analysis of mouse cryptic exons

Splicing patterns of identified target genes were analysed using the UCSC and IGV mouse genome browsers (Karolchik et al., 2014; Thorvaldsdóttir et al., 2013). A panel of 10 cryptic exons from the Catsperb (two exons), Ccdc60, Kdm4d, Lrrcc63, 4933409G03Rik, Tcte2, Ube2e2, Fam178b genes) and their immediately downstream exons were monitored for strength of splicing sequences using Sroogle (Schwartz et al., 2009). A panel of 19 exons were analysed for length and translation termination codons content (1700074P13Rik, 4833439L19Rik, ccdc60, Dnah12, Hmga2, Map2k5, Rbks, Tcte2, Ube2e2, 4933409G03Rik, 4930500J02Rik, 4932414N04Rik, Fam178b, Ccdc144b, Ston1, Usp54, Lca5l, and Catsperb and Lca5l).

Detection of splice isoforms in mouse testis RNA

The levels of different mRNA splice forms were detected in DNAse treated total RNA isolated from 18dpp mouse testes. cDNA was synthesised using superscript Vilo (Invitrogen) and PCR amplified, followed by either capillary gel electrophoresis (Qiaxcel) or agarose gel electrophoresis (Grellscheid et al., 2011). Gene-specific primers specific for different splice isoforms are given in Figure 3—source data 4.

Hits-clip

HITS-CLIP was performed as previously described (Licatalosi et al., 2008) using an antibody specific to RBMXL2 (Ehrmann et al., 2008). In short, for the CLIP analysis a single mouse testis was sheared in PBS and UV crosslinked. After lysis, the whole lysate was treated with DNase and RNase, followed by radiolabelling and linker ligation. After immunoprecipitation with purified antisera specific to RBMXL2 (Ehrmann et al., 2008), RNA bound RBMXL2 was separated on SDS-PAGE. A thin band at the size of 65 kDa (RBMXL2 migrates at around 50 kDa and MW of 50 nt RNA is about 15 kDa) was cut out and subject to protein digestion. RNA was recovered and subject to Illumina sequencing, and the reads were aligned to the mouse genome. HITS-CLIP tags mapped to 22,438 protein coding genes. HITS-CLIP data were further analysed to extract most frequently occurring pentamer nucleotide sequences within genes (ncRNA, ORF, 3’UTR, 5’UTR and intron). A window between +50 and −50 of the cross link site was analysed (to avoid crosslinking bias), and after correction for average pentamer occurrence in control sequences (as described in Wang et al., 2010). Each pentamer was only counted once in the analysed window.

Kdm4d minigene analysis

The Kdm4d cryptic exon and flanking intron sequences were PCR-amplified from mouse genomic DNA using the cloning primers Kdm4dF (5′-AAAAAAAAGAATTCCCACACAGCAAAACCCTCTC-3′) and Kdm4dR (5′-AAAAAAAAGAATTCGCCACCTTTTGCTATTCCTTT-3′). The PCR products were digested with EcoR1 restriction enzyme and cloned into the pXJ41 vector using the Mfe1 site midway through the 757 nucleotide β-globin intron (Bourgeois et al., 1999). Analysis of splicing patterns transcribed from minigenes was carried out in HEK293 cells as previously described (Grellscheid et al., 2011; Venables et al., 2005) using primers within the β-globin exons of pXJ41, pXJ41F 5′-GCTCCGGATCGATCCTGAGAACT-3′) and pXJ41R (5′-GCTGCAATAAACAAGTTCTGCT-3′).

Detection of proteins in mouse testis

For protein detection by immunohistochemistry, testes were fixed in Bouins, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned and attached to glass slides. Sections were prepared and immunohistochemistry carried out as previously described (Grellscheid et al., 2011). Primary antibodies were specific to caspase 3, p17-specific (Proteintech Europe Ltd). Protein detection by Western was as previously described (Grellscheid et al., 2011) using primary antibodies specific to RBMXL2 (Ehrmann et al., 2008), Meioc (Abby et al., 2016), and control antibodies specific to tubulin (Sigma T6793) and GAPDH (Abgent,San Diego CA, AP7873b).

Spermatocyte spreading

The tunica was removed from testes, and seminiferous tubules macerated with razor blades in a small volume of DMEM media. DMEM was added to 4 ml, and debris allowed to settle for 10 min. Cells were then pelleted from the suspension at 233 g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1–2 ml DMEM per animal. 5 drops of 4.5% sucrose were added to the centre of each clean glass slide using a Pasteur pipette. A single drop of the cell suspension was added to each slide from a height of 15–20 cm, followed by one drop of 0.05% Triton-X-100. The slides were incubated in a humid chamber for 10 min, then eight drops of fixative (2% PFA, 0.02% SDS, pH 8) were added to each slide, and incubated in humid chamber for 20 min. Slides were dipped in water to wash and allowed to air dry before storing at −80°C (Crichton et al., 2017).

Antibody staining and image capture

Slides were blocked for one hour in 0.15% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20, 5% goat serum PBS, then incubated with primary antibodies for three hours at room temperature or 4°C overnight. Primary antibodies were used at the following concentrations, diluted in block solution: rabbit anti-Sycp3 (1:500, Lifespan Cat# LS-B175 RRID:AB_2197351), mouse anti-Sycp3 (1:500, Abcam Cat# ab97672 RRID:AB_10678841), guinea pig anti-Sycp1 (1:200, from Howard Cooke), mouse anti-γH2AX (1:3000; Millipore Cat# 05–636, RRID:AB_309864), rabbit anti-H3K9me3 (1:500; Abcam Cat# ab8898, RRID:AB_306848), mouse anti-phospho H3 (1:1000; Abcam Cat# ab14955, RRID:AB_443110), human anti-centromere (1:50; Antibodies Incorporated, Cat#15-235-0001), mouse anti-AcSmc3 (1:1000, a gift from Katsuhiko Shirage [Nishiyama et al., 2010]). Slides were washed three times for five minutes in PBS before incubating with 1:500 secondary antibodies and ng/ul DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) for one hour at room temperature in darkness. Slides washed again three times and mounted in 90% glycerol, 10% PBS, 0.1% p-phenylenediamine.

Images were captured with Micromanager imaging software using an Axioplan II fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with motorised colour filters. Centromere and H3K9me3 staining was imaged by capturing z-stacks using a piezoelectrically-driven objective mount (Physik Instrumente) controlled with Volocity software (PerkinElmer). These images were deconvolved using Volocity, and a 2D image generated in Fiji.

Nuclei were staged by immunostaining for the axial/lateral element marker SYCP3. Pachytene nuclei were identified in this analysis by complete co-localisation of SYCP3 and either the transverse filament marker SYCP1 on all nineteen autosomes, or by the presence of nineteen bold SYCP3 axes in addition to two paired or unpaired sex chromosome axes of unequal length. Asynapsed pachytene nuclei were judged to be nuclei containing at least one fully synapsed autosome, and at least one autosome unsynapsed along >50% of its length (Crichton et al., 2017).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Quantification and statistical analyses were done using Graphpad (http://www.graphpad.com/).

Spermatocyte staining analysis

All scoring of immunostained chromosome spreads was performed blind on images after randomisation of filenames by computer script. Three Rbmxl2-/- and three wild type control animals were analysed for each experiment. Meiotic substaging analysis involved 179 nuclei from control animals, and 138 from Rbmxl2-/- mice. Diplotene phospho-H3 analysis involved 128 control and 157 Rbmxl2-/- nuclei, and the proportion of nuclei with bold centromeric signal was analysed using a Fisher’s test. Pachytene asynapsis was measured in 108 control and 92 Rbmxl2-/- nuclei, and the data analysed using a Fisher’s test. Centromere positioning and H3K9me3 staining was assessed across 73 control and 65 Rbmxl2-/-pachytene nuclei, and 66 diplotene control and 66 Rbmxl2-/- diplotene nuclei. These data were analysed using Wilcoxon Rank Sum test.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the BBSRC (grant BB/P006612/1, awarded to DJE) and the Wellcome Trust (grant 089225/Z/09/Z, awarded to DJE). JC and IRA were funded by the Medical Research Council (http://www.mrc.ac.uk/) through an intramural programme grant award to IRA (MC_PC_U127580973). Work by MRG and YB was supported by R01 AG AG046544 to YB. We thank Laura Bellutti and Gabriel Livera for kindly supplying the Meioc antiserum. We are very grateful to Donal O’Carroll (Edinburgh University), Nick Europe Finner, Julian Venables and Louise Reynard for comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Yoseph Barash, Email: yosephb@seas.upenn.edu.

David J Elliott, Email: David.Elliott@ncl.ac.uk.

Benjamin J Blencowe, University of Toronto, Canada.

Marianne E Bronner, California Institute of Technology, United States.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council BB/P006612/1 to Ingrid Ehrmann, Yilei Liu, David J Elliott.

Medical Research Council MC_PC_U127580973 to James H Crichton, Ian R Adams.

National Institutes of Health R01 AG AG046544 to Matthew R Gazzara, Yoseph Barash.

Wellcome Trust 089225/Z/09/Z to David J Elliott.

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Funding acquisition, Supervision, Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Resources, Software, Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Data curation.

Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Visualization, Writing-review and editing.

Visualization, Writing-review and editing.

Funding acquisition, Supervision, Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Funding acquisition, Supervision, Investigation, Writing-review and editing.

Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Investigation, Writing-original draft.

Ethics

Animal experimentation: Animal research was carried with the approval of the Newcastle University animal welfare ethical review body and the UK Government Home Office (Home Office project Licence Numbers PIL 60/4455 and PE51EB2EB).

Additional files

Data availability

RNAseq data are available via the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) using GEO accession number GSE101511

The following dataset was generated:

Ehrmann I, Crichton J, Gazzara MR, de Rooij DG, Steyn J. 2018. HnRNPGT knockout disrupts pre-mRNA splicing and arrests sperm development prior to meiotic metaphase. NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE101511

References

- Abby E, Tourpin S, Ribeiro J, Daniel K, Messiaen S, Moison D, Guerquin J, Gaillard JC, Armengaud J, Langa F, Toth A, Martini E, Livera G. Implementation of meiosis prophase I programme requires a conserved retinoid-independent stabilizer of meiotic transcripts. Nature Communications. 2016;7:10324. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson B, Smogorzewska A, Sigoillot FD, King RW, Elledge SJ. A genome-wide homologous recombination screen identifies the RNA-binding protein RBMX as a component of the DNA-damage response. Nature Cell Biology. 2012;14:318–328. doi: 10.1038/ncb2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsov T, Silva DG, O'Bryan MK, Sainsbury A, Lee NJ, Kennedy C, Manji SS, Nelms K, Liu C, Vinuesa CG, de Kretser DM, Goodnow CC, Petrovsky N. Fat aussie--a new Alström syndrome mouse showing a critical role for ALMS1 in obesity, diabetes, and spermatogenesis. Molecular Endocrinology. 2006;20:1610–1622. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellvé AR, Cavicchia JC, Millette CF, O'Brien DA, Bhatnagar YM, Dym M. Spermatogenic cells of the prepuberal mouse. Isolation and morphological characterization. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1977;74:68–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.74.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois CF, Popielarz M, Hildwein G, Stevenin J. Identification of a bidirectional splicing enhancer: differential involvement of SR proteins in 5' or 3' splice site activation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19:7347–7356. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.11.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NP, Leroy C, Sander C. MView: a web-compatible database search or multiple alignment viewer. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:380–381. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TA, Schweitzer AC, Chen TX, Staples MK, Lu G, Wang H, Williams A, Blume JE. Discovery of tissue-specific exons using comprehensive human exon microarrays. Genome Biology. 2007;8:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cléry A, Jayne S, Benderska N, Dominguez C, Stamm S, Allain FH. Molecular basis of purine-rich RNA recognition by the human SR-like protein Tra2-β1. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2011;18:443–450. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin GB, Cyr E, Bronson R, Marshall JD, Gifford EJ, Hicks W, Murray SA, Zheng QY, Smith RS, Nishina PM, Naggert JK. Alms1-disrupted mice recapitulate human Alström syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14:2323–2333. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crichton JH, Playfoot CJ, MacLennan M, Read D, Cooke HJ, Adams IR. Tex19.1 promotes Spo11-dependent meiotic recombination in mouse spermatocytes. PLOS Genetics. 2017;13:e1006904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton TP, He L, Wang B, Miller ML, Jin L, Stringer KF, Chang X, Baxter CS, Nebert DW. Identification of mouse SLC39A8 as the transporter responsible for cadmium-induced toxicity in the testis. PNAS. 2005;102:3401–3406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406085102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Grange P, Gratadou L, Delord M, Dutertre M, Auboeuf D. Splicing factor and exon profiling across human tissues. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38:2825–2838. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij DG, de Boer P, Boer, p DE. Specific arrests of spermatogenesis in genetically modified and mutant mice. Cytogenetic and genome research. 2003;103:267–276. doi: 10.1159/000076812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do DV, Strauss B, Cukuroglu E, Macaulay I, Wee KB, Hu TX, Igor RLM, Lee C, Harrison A, Butler R, Dietmann S, Jernej U, Marioni J, Smith CWJ, Göke J, Surani MA. SRSF3 maintains transcriptome integrity in oocytes by regulation of alternative splicing and transposable elements. Cell Discovery. 2018;4:33. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmann I, Dalgliesh C, Tsaousi A, Paronetto MP, Heinrich B, Kist R, Cairns P, Li W, Mueller C, Jackson M, Peters H, Nayernia K, Saunders P, Mitchell M, Stamm S, Sette C, Elliott DJ. Haploinsufficiency of the germ cell-specific nuclear RNA binding protein hnRNP G-T prevents functional spermatogenesis in the mouse. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17:2803–2818. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DJ. RBMY genes and AZFb deletions. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2000;23:652–658. doi: 10.1007/BF03343789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DJ, Bourgeois CF, Klink A, Stévenin J, Cooke HJ. A mammalian germ cell-specific RNA-binding protein interacts with ubiquitously expressed proteins involved in splice site selection. PNAS. 2000a;97:5717–5722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DJ, Venables JP, Newton CS, Lawson D, Boyle S, Eperon IC, Cooke HJ. An evolutionarily conserved germ cell-specific hnRNP is encoded by a retrotransposed gene. Human Molecular Genetics. 2000b;9:2117–2124. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.14.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grellscheid S, Dalgliesh C, Storbeck M, Best A, Liu Y, Jakubik M, Mende Y, Ehrmann I, Curk T, Rossbach K, Bourgeois CF, Stévenin J, Grellscheid D, Jackson MS, Wirth B, Elliott DJ. Identification of evolutionarily conserved exons as regulated targets for the splicing activator tra2β in development. PLoS Genetics. 2011;7:e1002390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosso AR, Gomes AQ, Barbosa-Morais NL, Caldeira S, Thorne NP, Grech G, von Lindern M, Carmo-Fonseca M. Tissue-specific splicing factor gene expression signatures. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:4823–4832. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan MM, Zagore LL, Licatalosi DD. Ptbp2 Controls an Alternative Splicing Network Required for Cell Communication during Spermatogenesis. Cell Reports. 2017;19:2598–2612. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamori N, Zhao M, Meistrich ML, Matzuk MM. The testis-enriched histone demethylase, KDM4D, regulates methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 during spermatogenesis in the mouse but is dispensable for fertility. Biology of Reproduction. 2011;84:1225–1234. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JI, Lau LF. Taking aim at the extracellular matrix: CCN proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2011;10:945–963. doi: 10.1038/nrd3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsotra A, Cooper TA. Functional consequences of developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12:715–729. doi: 10.1038/nrg3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan Z, Garrett-Engele PW, Johnson JM, Castle JC. Evolutionarily conserved and diverged alternative splicing events show different expression and functional profiles. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33:5659–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolchik D, Barber GP, Casper J, Clawson H, Cline MS, Diekhans M, Dreszer TR, Fujita PA, Guruvadoo L, Haeussler M, Harte RA, Heitner S, Hinrichs AS, Learned K, Lee BT, Li CH, Raney BJ, Rhead B, Rosenbloom KR, Sloan CA, Speir ML, Zweig AS, Haussler D, Kuhn RM, Kent WJ. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2014 update. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42:D764–D770. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopanja D, Roy N, Stoyanova T, Hess RA, Bagchi S, Raychaudhuri P. Cul4A is essential for spermatogenesis and male fertility. Developmental Biology. 2011;352:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand Y, Luria V, Haffner-Krausz R, Lonai P. Maternally expressed PGK-Cre transgene as a tool for early and uniform activation of the cre site-specific recombinase. Transgenic Research. 1998;7:105–112. doi: 10.1023/a:1008868325009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licatalosi DD, Mele A, Fak JJ, Ule J, Kayikci M, Chi SW, Clark TA, Schweitzer AC, Blume JE, Wang X, Darnell JC, Darnell RB. HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature. 2008;456:464–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licatalosi DD. Roles of RNA-binding Proteins and Post-transcriptional Regulation in Driving Male Germ Cell Development in the Mouse. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2016;907:123–151. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-29073-7_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling JP, Chhabra R, Merran JD, Schaughency PM, Wheelan SJ, Corden JL, Wong PC. PTBP1 and PTBP2 Repress Nonconserved Cryptic Exons. Cell Reports. 2016;17:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Bourgeois CF, Pang S, Kudla M, Dreumont N, Kister L, Sun YH, Stevenin J, Elliott DJ. The germ cell nuclear proteins hnRNP G-T and RBMY activate a testis-specific exon. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5:e1000707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Diatchenko L, Pan T. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45:6051–6063. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]