Abstract

Zika virus (ZIKV) infection is associated with abnormal functions of neuronal cells causing neurological disorders such as microcephaly in the newborns and Guillain-Barré syndrome in the adults. Typically, healthy brain growth is associated with normal neural stem cells proliferation, differentiation and maturation. This process requires a controlled cellular metabolism that is essential for normal migration, axonal elongation and dendrite morphogenesis of newly generated neurons. Thus, the remarkable changes in the cellular metabolism during early stages of neuronal stem cells differentiation is crucial for brain development. Recent studies show that ZIKV directly infects neuronal stem cells in the fetus and impairs brain growth. In this review, we highlighted the fact that the activation of P53 and inhibition of the mTOR pathway by ZIKV infection to neuronal stem cells induces early shifting from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) may induce immature differentiation, apoptosis, and stem cell exhaustion. We hypothesize that ZIKV infection to mature myelin-producing cells and resulting metabolic shift may lead to the development of neurological diseases, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome. Thus, the effects of ZIKV on the cellular metabolism of neuronal cells may leads to the incidence of neurological disorders as observed recently during ZIKV infection.

Keywords: Zika virus, Cellular metabolism, Neuronal cells, Microcephaly, Brain development

Introduction to Zika virus infection

Zika virus (ZIKV) is an arbovirus transmitted by the Aedes Aegypti and Aedes Albopictus mosquitos like Dengue virus (DENV), Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) and other arboviruses [1]. In the early 1900s, the first ZIKV isolate was reported in East Africa that initiated the African ZIKV lineage. The Asian ZIKV lineage emerged to Southeast Asia after the African lineage dissemination then to the Pacific Islands and the Americans [2]. Importantly, the Asian lineage showed more incidences of neurological disorders compared to African lineage [3]. The recent outbreaks of ZIKV infection showed a significant association between ZIKV infection and the incidence of microcephaly in newborns from infected women [4]. While in adults, the occurrence of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) due to ZIKV infection was approximately 1 in 5,000 cases during the French Polynesia outbreak [5].

ZIKV crosses the placenta and infects amniotic fluid and fetal brain tissues causing significant impact on brain development [6]. Recent studies showed the pathogenesis of ZIKV infections depends on the stages of brain development [7, 8]. ZIKV infection at the early gestational period causes fetal death while ZIKV infection at the late gestational period is associated with significant reduction in the neural precursor cells [7]. The postnatal ZIKV infection causes persistent structural and functional alterations of the central nervous system including maturational changes in specific brain regions [8]. Importantly, ZIKV infection induces substantial injury to fetal brain associated with a considerable loss in fetal neuronal progenitor cells especially in the temporal cortex, dentate gyrus, and hippocampus [9].

ZIKV infection impairs fetal brain growth by targeting neuronal stem cells proliferation and inducing premature differentiation and such events lead to neuronal progenitor cells depletion [10]. Neuronal stem cell differentiation requires controlled cellular metabolism that could be affected by ZIKV infection. In this review, we highlight the impact of ZIKV infection on the cellular metabolism of neuronal cells that influence stem cell differentiation and mature cells function.

Viral infection and cellular metabolism

The balancing between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) determines the physiological conditions of the cells. Cancer cells commonly use glycolysis to produce energy and metabolic precursors for mass building; this process provides a significant amount of lactate from glycolytic pyruvate [11]. Similarly, stem cells usually require higher glycolysis rates than OXPHOS for maintaining an efficient replication [12]. This metabolic phenomenon is called a Warburg effect; a cellular metabolism phenomenon of growing cells improves cell proliferation and growth of replicating cells [13].

Viruses manipulate cellular metabolism to secure the required metabolites and energy for viral propagation. As a close relative to ZIKV, DENV induces remarkable alterations in the cellular metabolism by increasing glucose consumption [14, 15]. Thus DENV exploits glycolysis as a source of energy and metabolites during the time course of infection [14]. The expression of DENV non-structural protein 1 (NS1) induces glycolysis flux and energy production by interfering with the function of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) [15].

Neuronal differentiation and cellular metabolism

Glycolysis and mitochondrial OXPHOS represent the primary processes by which neuronal cells obtain the required metabolic precursors and energy via glucose oxidation [16]. Neural stem cells (NSCs) mostly rely on the glycolysis for energy production rather than OXPHOS, and neuronal differentiation is strongly associated with a controlled shifting from glycolysis to OXPHOS [17]. Previous studies showed that the pharmacological or genetic inhibition of mitochondrial functions impaired stem cell differentiation and embracing high levels of stemness makers [18]. Contrarily, the successful induction of mature fibroblasts to pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that have a similar metabolism to neuronal stem cells requires metabolic shifting from OXPOS to glycolysis [18]. Thus, neuronal stem cells are competent to hypoxic conditions (probably that could be seen at the early stages of tissue development), which are enhancing iPSCs induction and stem cell proliferation [19].

Previous studies suggested that downregulation of glycolytic pathways at the early stages of proliferation or upregulation of glycolysis or OXPHOS pathways during the differentiation impairs and induces NSCs apoptosis [20]. This fact emphasizes that neuron survival relies on slowing the glycolysis rate during the transition period from cellular proliferation to differentiation. However, mitochondrial dysfunction at the differentiation stages of NSCs produces a harmful effect on neuronal cells maturation but not NSCs proliferation [21]. Therefore, the upregulation of OXPHOS pathways and increasing mitochondrial metabolism are crucial for NSCs differentiation [22]. Thus, the number of mitochondria considerably increases in the mature neuronal cell mass [23] that requires high energy levels via the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and OXPHOS in the mitochondria [24]. In summary, the metabolic homeostasis at each stage of NSCs proliferation and differentiation may be crucial for prenatal and postnatal brain development.

Metabolic homeostasis of neuronal cells in ZIKV infection

ZIKV crosses the placenta and infects the fetal brain at different stages of pregnancy and during the early stage of neonatal brain maturation. Various neuronal lineages at different stages of proliferation and differentiation are susceptible to ZIKV infection during brain development [25]. Thus, NSCs undergo growth defects due to ZIKV infection that induces cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and inhibition of differentiation [26]. As such, the infected brains are small with enlarged ventricles and a thinner cortex, consistent with a microcephalic phenotype [10]. Therefore, ZIKV infection probably induces two distinct patterns of cellular metabolic changes based on the differentiation stage of the neuronal cells.

Neuronal stem cells metabolism in ZIKV infection

Neural stem cells (NSCs) represent a primary target for ZIKV infection. During the course of infection, ZIKV proteins interfere with NSCs function causing severe consequences such as metabolic fluxes, inhibition of cell proliferation, and cellular apoptosis. The events may be mediated by ZIKV non-structural proteins, NS4A and NS4B that synergistically suppress the Akt-mTOR pathway, induce a defective neurogenesis in human fetal NSCs [27]. Controlled regulation of mTOR activity is crucial for NSCs differentiation to mature neuronal cells [28]. Romine and colleagues demonstrated in vitro studies that inhibiting the mTOR pathway in NSCs lead to impairing NSCs proliferation [29]. Furthermore, In vivo studies also showed that induction of the mTOR pathway in aged mice stimulated neuronal progenitor cells proliferation [30], In general, downregulation of the Akt-mTOR pathway induces mitochondria elongation to extend ATP production via OXPHOS [31]. Recent reports have highlighted the fact that Flavivirus infection causes mitochondria elongation via dynamin 1-like protein (DRP1) impairment as similar to DENV infection [32]. Since elongated mitochondria produce high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by glial cells possibly lead to increase mitochondrial stress [33]. Virus-induced mitochondrial stress like ZIKV infection to neuronal stem cells also causes mitochondrial apoptosis via mitochondrial sequestration of phospho- TBK1 during mitosis that leads to cell death [26]. This phenomenon of mitochondrial dysfunction could be altered in the mature cells, like human lung epithelial cells, by a rapid release of IFN-β that delay mitochondrial apoptosis after ZIKV infection [34].

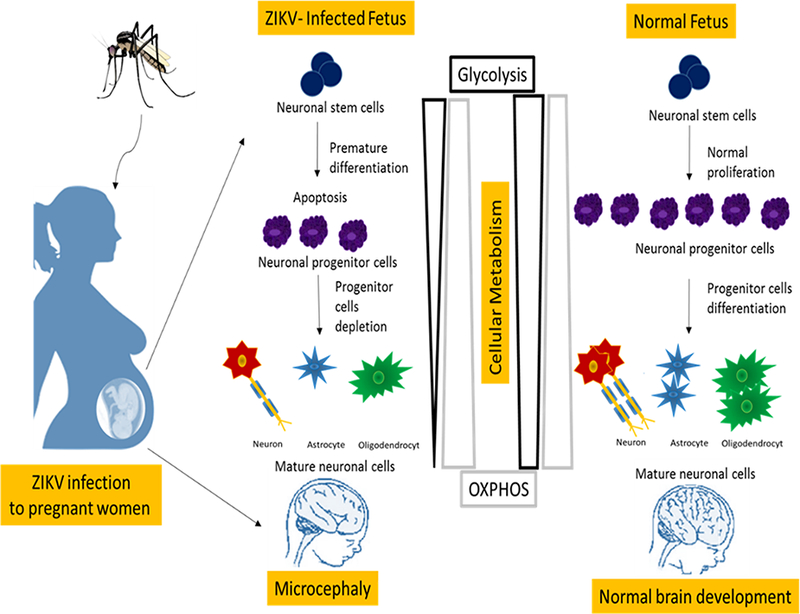

Recently, it has been shown that by treating P53 inhibitors to ZIKV-infected cells known to be attenuated cellular apoptosis [35] and provided basis that neuronal stem cells may have significant activation of tumor suppressor p53 (P53) during the early stages of ZIKV infection. Next, it has been shown that, P53 inhibits glycolysis by inducing TP53-inducible glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) a regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis [36]. Furthermore, P53 shuts down the mTOR pathway and transfers cells to use mitochondrial OXPHOS for efficient ATP production to reduce metabolic precursors for cellular division [37]. In general, stem cells require higher glycolysis rates than OXPHOS for maintaining an efficient replication [12]. Thus, the inhibition of glycolysis at the early stage of neuronal stem cells differentiation leads to terminating cell proliferation and induces premature differentiation and apoptosis. This concept is supported by observations that early stages of ZIKV infection to human iPSC-derived brain organoids that induced progenitor cells exhaustion and premature differentiation [38]. In addition to the higher rate of stem reduction in the brain of postnatal ZIKV-infected mice compared to mature mice [39], and described in Figure 1. In summary, ZIKV infection to pregnant women at the first trimester of pregnancy disrupts the cellular metabolism of NSCs that affects neuronal development that may cause microcephaly in newborns.

Figure 1:

ZIKV infection induces metabolic fluxes at the early stage of neuronal stem cells differentiation leads to terminating cell proliferation and induces premature differentiation and apoptosis. While, metabolic fluxes at mature stages of neuronal cells induces cellular dysfunction and neurological disorders.

Mature neuronal cells metabolism in ZIKV infection

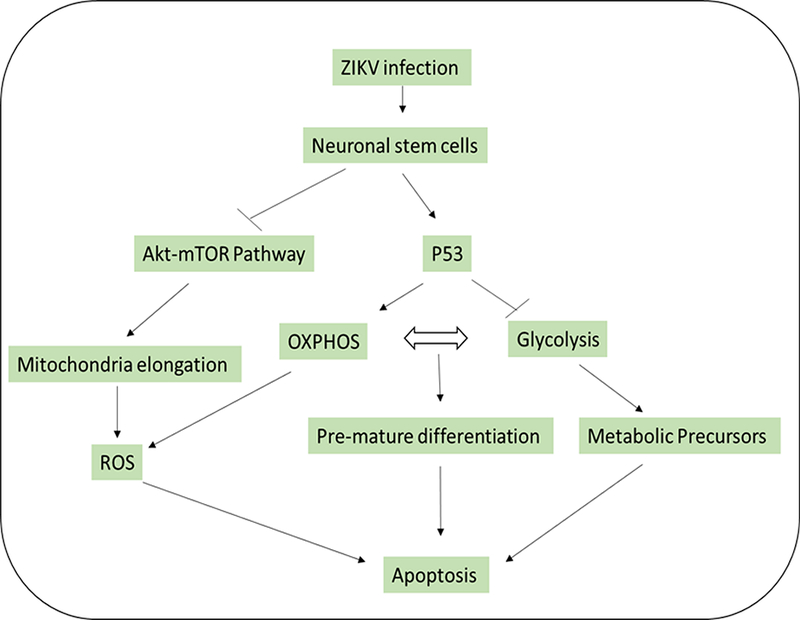

Like other viruses, ZIKV infection interrupts cellular metabolic homeostasis to support viral replication in the infected cells [14, 15, 40]. The global gene expression profile from different cell lines infected with ZIKV revealed significant differences in host metabolic processes [40]. Human microglia, fibroblast, embryonic kidney, and monocyte-derived macrophage cell lines undergo significant depletion in the cellular resources due to ZIKV infection. It seems that ZIKV infection induces cellular metabolism reprogramming towards glycolysis in order to support viral RNA and protein synthesis and a minimal requirement of ATP production [34]. Such patterns of metabolic fluxes have been observed in dengue virus (DENV)- infected cells through a remarkable upregulation of glycolytic pathway to efficiently support viral replication [14, 15] as denoted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2:

ZIKV infection induces cellular metabolism reprogramming in neuronal stem cells via inhibition of mTOR pathway and activation of P53.

Unlike DENV, Zika virus infects mature neuronal cells that express AXL receptors causing neurological disorders [41]. Importantly, neurons lack the glycolysis promoting enzyme 6- phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose 2,6-bisphosphatase, isoform 3 (PFKFB3) that can probably increase glycolysis [42]. The activation of PFKFB3 to upregulate glycolysis leads to neuronal apoptosis [20] suggesting that neurons are unable to sustain high glycolytic rates. Currently lacks information on the impact of ZIKV infection on glucose transporters expression GLUT1 and mature neurons metabolic energy. Thus, more studies are warranted to support mature neurons response to ZIKV infection.

Among glial cells, myelin-producing cells are susceptible to ZIKV infection and cellular metabolism changes towards glycolysis. There are two types of myelination in the human nervous system. The first occurs in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) by oligodendrocytes. A singular oligodendrocyte can provide myelin sheath for around 50 axons. The second myelination process occurs in the peripheral nervous system (cranial nerves and peripheral nerves) by Schwann cells providing myelin sheath for only one axon segment per Schwann cell [43]. Therefore, we postulate that ZIKV infection to myelin- producing cells may induce mitochondrial dysfunction via increasing glycolysis rate and decreasing OXPHOS rate. This possibility may lead to significant defects in myelin synthesis and development of neurological disease such as Guillain-Barr5 syndrome (Fig. 3). Thus, ZIKV-infected mice developed cute retinitis, panuveitis, focal retinal degeneration, and ganglion cell loss suggesting that ZIKV attacks the peripheral nervous system and induces neurodegenerative disease [44].

Figure 3:

ZIKA infection induces metabolic shifting towards glycolysis by activation of TLR3. Inhibition of mitochondria function produces high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that leads to neuronal cells dysfunction and development of neurodegenerative disease such as Guillain-Barre syndrome.

A possible link has been observed between neuronal cell fate and TLR3 activation during ZIKV infection and known to induces fast production of type I IFN by astrocytes [45]. Taking together, the activation of TLR3 and its ligand IFN by ZIKV infection may be upregulate glycolysis and downregulate TCA cycle activity and OXPHOS as similar to the phenomenon of the Warburg effect [46]. Thus, low OXPHOS activity may induce mitochondrial dysfunction [47]. There is a growing body of evidence providing evidences that the mitochondrial dysfunction is generally linked to oxidative stress which has a potential role in inducing neurodegeneration [48] as presented in Fig. 3. ZIKV infection to glial cells raised the expression levels of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), an anti-oxidant gene in response to elevated oxidative stress [33]. The low activity of mitochondria during the early differentiation stage is mostly associated with high ROS levels leading to cellular apoptosis [49]. Interestingly, treatment with anti-oxidative agents significantly attenuated cellular apoptosis in the reprogrammed neurons [50].

Understanding how ZIKV exploits the metabolism of neuronal cells is important for targeting certain metabolic pathways that are vital for virus replication. Such studies will be valuable in developing metabolic inhibitors for therapeutic purposes. Previous studies showed a remarkable shafting in the lipid metabolism profile in Wolbachia- infected mosquito cells that led to inhibit DENV replication [51–53]. Furthermore, inhibition of cholesterol [51], fatty acids synthesis [52], and phospholipid metabolism [53] showed anti-flavivirus activity. However, manipulation of cellular metabolism by ZIKV during neuronal stem cells differentiation is more complicated. Therefore, further studies are urgently needed to explore the nuclear receptors or transcription factors that could be considered as targets to block ZIKV exploiting to neuronal cells metabolism

Conclusions

ZIKV infection modulates the cellular metabolism in neuronal cells based on the differentiation stages. Activation of P53 and inhibition of the mTOR pathway by ZIKV infection to neuronal stem cells induce early shifting from glycolysis to OXPHOS that produce immature differentiation, apoptosis, and stem cell exhaustion. There is a remarkable absence of studies on ZIKV infection to mature neurons. We postulate that the ZIKV infection on mature myelin-producing cells and resulting metabolic shift may lead to the development of neurological diseases, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome. Detailed further studies are warranted to confirm the changes in neuronal cells metabolism caused by ZIKV infection.

Acknowledgements:

This work is supported in part 1U01GM117175 to SF and R01AI113883 and Nebraska Neuroscience Alliance Endowed Fund Awarded to SNB. We thank Robin Taylor for the editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest existed

References

- 1.Rothan HA, Bidokhti MRM, Byrareddy SN (2018) Current concerns and perspectives on Zika virus co-infection with arboviruses and HIV. J Autoimmun 89:11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gatherer D, Kohl A (2016) Zika virus: a previously slow pandemic spreads rapidly through the Americas. J Gen Virol 97: 269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weaver SC, Costa F, Garcia-Bianco MA, Ko Al, Ribeiro GS, et al. (2016) Zika virus: History, emergence, biology, and prospects for control. Antiviral Res 130: 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen LR, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA (2016) Zika Virus. N Engl J Med 375: 294–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvet G, Aguiar RS, Melo ASO, Sampaio SA, de Filippis I, et al. (2016) Detection and sequencing of Zika virus from amniotic fluid of fetuses with microcephaly in Brazil: a case study. Lancet Infect Dis 16: 653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magnani DM, Rogers TF, Maness NJ, Grubaugh ND, Beutler N, Bailey VK, et al. (2018) Fetal demise and failed antibody therapy during Zika virus infection of pregnant macaques. Nat Commun 9: (1)1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffey LL, Keesler Rl, Pesavento PA, Woolard K, Singapuri A, Watanabe J, et al. (2018) Intraamniotic Zika virus inoculation of pregnant rhesus macaques produces fetal neurologic disease. Nat Commun 9: (1) 2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavigner M, Raper J, Kovacs-Balint Z, Gumber S, O’Neal JT, Bhaumik SK, et al. (2018) Postnatal Zika virus infection is associated with persistent abnormalities in brain structure, function, and behavior in infant macaques. Sci Transl Med 10:(435). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams Waldorf KM, Nelson BR, Stencel-Baerenwald JE, Studholme C, Kapur RP, Armistead B, et al. (2018) Congenital Zika virus infection as a silent pathology with loss of neurogenic output in the fetal brain. Nat Med 24: (3) 368–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li C, Xu D, Ye Q, Hong S, Jiang Y, et al. (2016) Zika Virus Disrupts Neural Progenitor Development and Leads to Microcephaly in Mice. Cell Stem Cell 19: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB (2009) Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324: 1029–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shyh-Chang N, Daley GQ, Cantley LC (2013) Stem cell metabolism in tissue development and aging. Development 140:(12) 2535–2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB (2008) The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab 7: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontaine KA, Sanchez EL, Camarda R, Lagunoff M (2015) Dengue virus induces and requires glycolysis for optimal replication. J Virol 89: 2358–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allonso D, Andrade IS, Conde JN, Coelho DR, Rocha DC, et al. (2015) Dengue Virus NS1 Protein Modulates Cellular Energy Metabolism by Increasing Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Activity. J Virol 89: 11871–11883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belanger M, Allaman I, & Magistretti PJ (2011). Brain energy metabolism: focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab, 14(6), 724–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agathocleous M, Love NK, Randlett O, Harris JJ, Liu J, et al. (2012) Metabolic differentiation in the embryonic retina. Nat Cell Biol 14: 859–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folmes CD, Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Arrell DK, Lindor JZ, et al. (2011) Somatic oxidative bioenergetics transitions into pluripotency-dependent glycolysis to facilitate nuclear reprogramming. Cell Metab 14: 264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida Y, Takahashi K, Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S (2009) Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 5: 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrero-Mendez A, Almeida A, Fernandez E, Maestre C, Moncada S, et al. (2009) The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C-Cdh1. Nat Cell Biol 11: 747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz-Castro B, Pardal R, Garcia-Flores P, Sobrino V, Duran R, et al. (2015) Resistance of glia-like central and peripheral neural stem cells to genetically induced mitochondrial dysfunction-differential effects on neurogenesis. EMBO Rep 16: 1511–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wanet A, Arnould T, Najimi M, Renard P (2015) Connecting Mitochondria, Metabolism, and Stem Cell Fate. Stem Cells Dev 24: 1957–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steib K, Schaffner I, Jagasia R, Ebert B, Lie DC (2014) Mitochondria modify exercise-induced development of stem cell-derived neurons in the adult brain. J Neurosci 34: 6624–6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schon EA, Przedborski S (2011) Mitochondria: the next (neurode)generation. Neuron 70: 1033–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Pol AN, Mao G, Yang Y, Ornaghi S, Davis JN (2017) Zika Virus Targeting in the Developing Brain. J Neurosci 37: 2161–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onorati M, Li Z, Liu F, Sousa AMM, Nakagawa N, et al. (2016) Zika Virus Disrupts Phospho-TBK1 Localization and Mitosis in Human Neuroepithelial Stem Cells and Radial Glia. Cell Rep 16: 2576–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang Q, Luo Z, Zeng J, Chen W, Foo SS, et al. (2016) Zika Virus NS4A and NS4B Proteins Deregulate Akt-mTOR Signaling in Human Fetal Neural Stem Cells to Inhibit Neurogenesis and Induce Autophagy. Cell Stem Cell 19: 663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magri L, Cambiaghi M, Cominelli M, Alfaro-Cervelloa C, Cursi M, et al. (2011) Sustained activation of mTOR pathway in embryonic neural stem cells leads to development of tuberous sclerosis complex-associated lesions. Cell Stem Cell 9: 447–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paliouras GN, Hamilton LK, Aumont A, Joppe SE, Barnabe-Heider F, et al. (2012) Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling is a key regulator of the transit-amplifying progenitor pool in the adult and aging forebrain. J Neurosci 32: 15012–15026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romine J, Gao X, Xu XM, So KF, Chen J (2015) The proliferation of amplifying neural progenitor cells is impaired in the aging brain and restored by the mTOR pathway activation. Neurobiol Aging 36: 1716–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomes LC, Scorrano L (2011) Mitochondrial elongation during autophagy: a stereotypical response to survive in difficult times. Autophagy 7: 1251–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbier V, Lang D, Valois S, Rothman AL, Medin CL (2017) Dengue virus induces mitochondrial elongation through impairment of Drp1-triggered mitochondrial fission. Virology 500: 149–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tricarico PM, Caracciolo I, Crovella S, D’Agaro P (2017) Zika virus induces inflammasome activation in the glial cell line U87-MG. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 492: 597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frumence E, Roche M, Krejbich-Trotot P, El-Kalamouni C, Nativel B, et al. (2016) The South Pacific epidemic strain of Zika virus replicates efficiently in human epithelial A549 cells leading to IFN-beta production and apoptosis induction. Virology 493: 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghouzzi VE, Bianchi FT, Molineris I, Mounce BC, Berto GE, et al. (2016) ZIKA virus elicits P53 activation and genotoxic stress in human neural progenitors similar to mutations involved in severe forms of genetic microcephaly and p53. Cell Death Dis 7: e2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MN, Nakano K, et al. (2006) TIGAR, a p53- inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell 126: 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng Z, Levine AJ (2010) The regulation of energy metabolism and the IGF-1/mTOR pathways by the p53 protein. Trends Cell Biol 20: 427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabriel E, Ramani A, Karow U, Gottardo M, Natarajan K, et al. (2017) Recent Zika Virus Isolates Induce Premature Differentiation of Neural Progenitors in Human Brain Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 20: 397–406 e395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang WC, Abraham R, Shim BS, Choe H, Page DT (2016) Zika virus infection during the period of maximal brain growth causes microcephaly and corticospinal neuron apoptosis in wild type mice. Sci Rep 6: 34793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tiwari SK, Dang J, Qin Y, Lichinchi G, Bansal V, et al. (2017) Zika virus infection reprograms global transcription of host cells to allow sustained infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 6: e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nowakowski TJ, Pollen AA, Di Lullo E, Sandoval-Espinosa C, Bershteyn M, et al. (2016) Expression Analysis Highlights AXL as a Candidate Zika Virus Entry Receptor in Neural Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 18: 591–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolanos JP, Almeida A, Moncada S (2010) Glycolysis: a bioenergetic or a survival pathway? Trends Biochem Sci 35: 145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradl M, Lassmann H (2010) Oligodendrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol 119: 37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao Z, Yang M, Azar SR, Soong L, Weaver SC, et al. (2017) Viral Retinopathy in Experimental Models of Zika Infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58: 4355–4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krawczyk CM, Holowka T, Sun J, Blagih J, Amiel E, et al. (2010) Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood 115: 4742–4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell GR, Ziabreva I, Reeve AK, Krishnan KJ, Reynolds R, et al. (2011) Mitochondrial DNA deletions and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 69: 481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin MT, Beal MF (2006) Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443: 787–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walton NM, Shin R, Tajinda K, Heusner CL, Kogan JH, et al. (2012) Adult neurogenesis transiently generates oxidative stress. PLoS One 7: e35264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gascon S, Murenu E, Masserdotti G, Ortega F, Russo GL, et al. (2016) Identification and Successful Negotiation of a Metabolic Checkpoint in Direct Neuronal Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 18: 396–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molloy JC, Sommer U, Viant MR, Sinkins SP (2016) Wolbachia Modulates Lipid Metabolism in Aedes albopictus Mosquito Cells. Appl Environ Microbiol 82: 3109–3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee CJ, Lin HR, Liao CL, Lin YL (2008) Cholesterol effectively blocks entry of flavivirus. J Virol 82: 6470–6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heaton NS, Perera R, Berger KL, Khadka S, Lacount DJ, et al. (2010) Dengue virus nonstructural protein 3 redistributes fatty acid synthase to sites of viral replication and increases cellular fatty acid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 17345–17350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sessions OM, Barrows NJ, Souza-Neto JA, Robinson TJ, Hershey CL, et al. (2009) Discovery of insect and human dengue virus host factors. Nature 458: 1047–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]