Abstract

Impaired interactions between Calcineurin (Cn) and (Cu/Zn) superoxide dismutase (SOD1) are suspected to be responsible for the formation of hyperphosphorylated protein aggregation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Serine (Ser)- enriched phosphorylated TDP-43 protein aggregation appears in the spinal cord of ALS animal models, and may be linked to the reduced phosphatase activity of Cn. The mutant overexpressed SOD1G93A protein does not properly bind zinc (Zn) in animal models; hence, mutant SOD1G93A–Cn interaction weakens. Consequently, unstable Cn fails to dephosphorylate TDP-43 that yields hyperphosphorylated TDP-43 aggregates. Our previous studies had suggested that Cn and SOD1 interaction was necessary to keep Cn enzyme functional. We have observed low Cn level, increased Zn concentrations, and increased TDP-43 protein levels in cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions of the spinal cord tissue homogenates. This study further supports our previously published work indicating that Cn stability depends on functional Cn–SOD1 interaction because Zn is crucial for maintaining the Cn stability. Less active Cn did not efficiently dephosphorylate TDP-43; hence TDP-43 aggregations appeared in the spinal cord tissue.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11064-017-2461-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ALS, TDP-43, SOD1G93A, Calcineurin, Spinal cord

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (a.k.a. Lou Gehrig Disease) is a non-treatable progressive neurodegenerative disease that is 100% fatal and claims about 30,000 lives per year in the USA (http://www.als.org). Nearly 90% of these cases are sporadic. The disease is characterized by the selective loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord, brain stem, and cerebral (motor) cortex [1]. The causative factors of the disease remain contentious at a molecular level, although the hallmark of ALS is the formation of superoxide dismutase-enriched plaques in Lewy bodies in the spinal cord [2]. Involvement of a previously discovered protein TDP-43 in ALS pathogenesis [3, 4] has recently attracted attention, resulting in several important papers published during the last decade [5–10]. Trans activating response region DNA binding protein (TDP-43)-enriched plaques are observed in ALS, and TDP-43 mutation-induced aggregates are considered as a promoting factor in ALS pathology [11]. TDP-43 phosphorylation and subsequent aggregation have been found in motor neurons [12, 13], suggesting that TDP-43 aggregation due to abnormal phosphorylation may also be relevant to reduced activity of Cn in ALS, since phosphatase Cn regulates the TDP-43 phosphorylation in both lower and higher organisms [14].

Partial inactivation of Cn in both sporadic and familial ALS patients as well as in an asymptomatic carrier of a dominant SOD1 mutation may suggest the role of Cn in the pathogenesis of ALS [15].Both Cn and SOD1 are zinc (Zn)-containing metalloproteins [16–21]. The failure of this protein–protein interaction(s) may lead to increased labile Zn accumulation, thereby causing toxicity in motor neurons [22, 23]. Therefore, the involvement of Zn in the development of ALS is another critical concept to be considered since metal cations and oxidative injury have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ALS [24, 25].

Elucidating these multiple factors will contribute to a basic understanding of Cn/SOD1/TDP-43 protein interactions that may occur in the early stages of ALS development. This could lead to early treatment options focused on restoring normal protein–protein interactions [26].

The focus of our work is to provide some preliminary evidence that reduced Cn activity is due to weakened interactions between SOD1 and Cn in the transgenic (Tg) SOD1G93A rodent (i.e., rat and mouse) model. We hypothesize that poorly bound Zn in both metallo-enzymes (i.e. SOD1 and Cn) dissociate and accumulate in the cytosol, eventually inducing motor neuron death [27]. Subsequently, the less functional Cn enzyme would fail to dephosphorylate TDP-43, leading to the formation of hyperphosphorylated TDP-43 aggregates that are considered to be the hallmark of neuropathology in 90% of ALS cases [12].

Materials and Methods

Animals

Tg SOD1G93A rat (B6.Cg-Tg(SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J) breeders were obtained from Taconic and offspring were genotyped using the protocol described in the Jackson Laboratory website (https://www2.jax.org/protocolsdb/f?p=116:5:0::NO:5:P5_MASTER_PROTOCOL_ID,P5_JRS_CODE:9877,004435). Rats were fed normal chow (Harlan Teklad rodent diet 8604 from Teklad diets, Madison, WI) and were housed in University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC) animal facilities for 6 months. Animal use was approved by KUMC IACUC protocol (#2013-2142).

Tissues

After animals were deeply anesthetized and decapitated, their spinal cords were flushed out according to a previously published method [28]. Briefly, the spinal column was sectioned at about the 4th sacral vertebra. A 20″–22″ gauge needle attached to a 10 ml syringe was inserted into the caudal opening of the spinal column. Approximately 5 ml of PBS was gently injected to flush the spinal cord from the rostral end of the severed spinal column. The cord was then sectioned into cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions according to a template that served as a visual aid (Fig. S1). The template was constructed based on anatomic atlas of the rat spinal cord [29].

Homogenate

All glassware was washed with strong acids (i.e., nitric acid and perchloric acid) to remove possible contamination for trace elements [30] that may interfere fluorometric zinc analysis. The spinal cord sections were weighed and placed in a pre-chilled 1 ml glass homogenizer on ice. Ten volumes of tissue homogenization buffer (0.32 M sucrose; 10 mM HEPES; 0.5 mM MgSO4; 10 mM ε-amino caproic acid; pH 7.4) and the tissues (10 vol. buffer/g wet tissue) were gently homogenized on ice with 10–15 strokes (just enough to completely dissociate the tissue) using the cooled pestle. The protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) spectrophotometric method (Thermo Scientific, Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit; Cat#23227) and the homogenate aliquots were stored at − 80 °C until use.

Western Blot Analysis

Spinal cord section homogenates were resolved in pre-cast 4–20% SDS/PAGE (Bio-Rad, mini-PROTEAN TGX™ gels; Cat#456–1095) under the reducing conditions. The proteins were transferred onto a transfer membrane (Millipore, Immobilon® PVDF membrane, Cat#IPFL00010) and probed with anti-Calcineurinα, (Cat#C1956; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA; monoclonal antibody) anti-Calcineurinβ, (Cat#C0581; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA; monoclonal antibody), anti-SOD1 (Cat#100269-1-AP; Protein Tech, USA, Rabbit polyclonal antibody), and anti-TDP-43 (Cat#10782-2-AP; Protein Tech, USA) antibodies. Odyssey/LI-COR detection system (LI-COR Biosciences, Nebraska, USA) was used for analyzing the protein bands (Image Studio Ver.3.1).

Zinc Analysis

Spinal cord tissue homogenates were centrifuged (16 K×g; 30 min at 4 °C) in order to obtain a clear supernatant. Protein concentrations were measured by BCA assay. The supernatant samples were prepared for Zn assay analysis and the concentrations were measured by a fluorometric Zinc quantification kit (Abcam Inc., USA; Cat#ab176725) according to the manufacturer’s provided protocol. A Bio-Tek microplate reader (Model: Synergy HT, USA equipped with Gen 5 software version 2.05.5) was used for the fluorescence measurement.

Statistical Analysis

Mann–Whitney U rank sum tests followed by the calculation of two-tailed p values were used for determining the significance between groups. SigmaPlot (ver.12.5) was used for graphing and statistical analysis.

Results

Calcineurin Protein Levels Were Lower in Tg Cervical and Thoracic Regions of the Spinal Cord

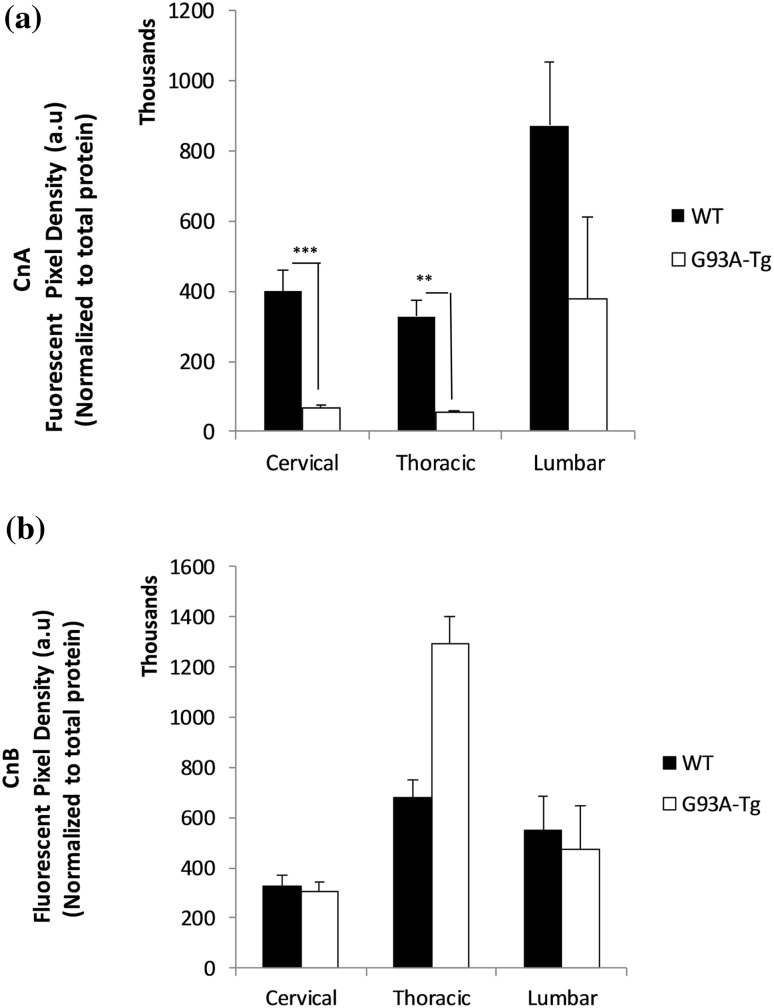

We analyzed protein levels of both the catalytic subunit of Calcineurin (CnA or PPP3CA) and the regulatory subunit (CnB or PPP3R1). We observed significantly lower catalytic subunit protein levels in the cervical (P ≤ 0.001) and thoracic (P ≤ 0.008) spinal cord of Tg animals, but not in the lumbar region (P ≤ 0.130) in (Fig. 1a). There were no differences in the CnB-regulatory subunit protein levels between the two groups (Fig. 1b). We were unable to harvest sufficient tissue from the sacral region to perform CnA and CnB western blot analysis.

Fig. 1.

a Catalytic subunit CnA protein levels. Significantly lower catalytic subunit protein levels were observed in the cervical (P ≤ 0.001) and thoracic (P ≤ 0.008) spinal cord of Tg animals, but not in the lumbar region (P ≤ 0.130). Each bar represents the average of five animals for each group (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM. b Regulatory subunit CnB protein levels. No differences were observed in the CnB-regulatory subunit protein levels between the two groups. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5)

TDP-43 Protein Levels in Spinal Cord Regions

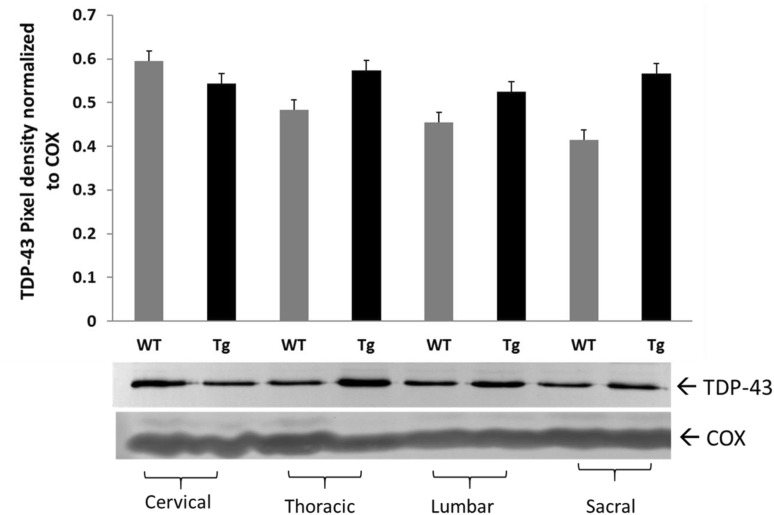

We measured spinal cord TDP-43 protein levels by Western blot analysis. We observed an increasing trends of TDP-43 in thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions; however, no statistically significant differences in TDP-43 between Tg and WT rats in any of the regions measured (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

TDP-43 protein levels in spinal cord regions of SOD1G93A Tg rat. TDP-43 protein levels in spinal cord regions of WT (n = 6) and Tg (n = 8) animals. Pan anti-TDP-43 Ab was used for Western blot analysis. No statistically significant difference was observed in cervical (P < 0.0663), in thoracic (P < 0.250), in lumbar (P < 0.393), and in sacral (P < 0.157) regions of WT and Tg animals. Data are mean ± SEM

Predicted Phosphorylation Site Analysis for TDP-43

We have employed a computer based Predictor of Natural Disordered Region (PONDR®) algorithm using TDP-43 sequence (NCBI accession code: Q5R5W2.1). Disordered Enhanced Phosphorylation Predictor (DEPP) analysis predicted 28 potential phosphorylation sites and a majority of them were Ser amino acid enriched on the C-terminus (aa 369–410) (Fig. S5).

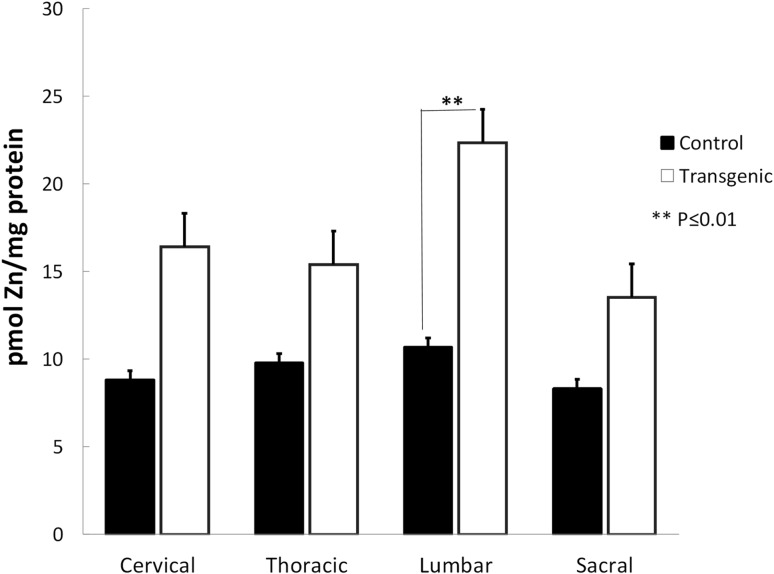

Higher Zn Concentrations Were Measured in Tg Lumbar Spinal Cord

We measured the total Zn concentrations in all regions of rat spinal cord (Fig. 3). We measured significantly greater Zn in the lumbar region of Tg animals (P ≤ 0.01). The greater Zn levels in the cervical, thoracic, and sacral regions did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 3.

Zinc concentrations in rat spinal cord regions. Significantly greater Zn concentrations were measured in the lumbar region of Tg animals (**P ≤ 0.01). The Zn levels in the cervical, thoracic, and sacral regions did not reach statistical significance. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5)

Discussion

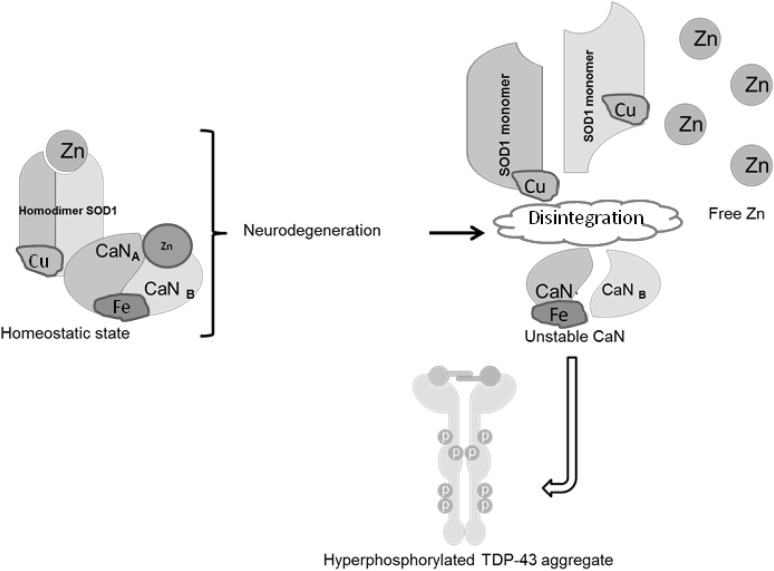

We previously showed that Cn activity depends on the presence of normal homodimer SOD1 in vitro and concluded that Cn–SOD1 interactions actually protect SOD1 dimers from oxidative modification [31]. Evidence provided in the literature suggests that depletion of Zn likely leads the SOD1 protein to undergo aggregation under oxidative conditions [32, 33] We have hypothesized that (1) the mutation in SOD1G93A weakens Zn binding in SOD1 [34]; leading the protein misfolding; (2) this abnormal SOD1 may not efficiently interact with Cn, promoting Zn loss and reduced activity in Cn [31]; (3) less active Cn fails to dephosphorylate TDP-43, leading TDP-43 hyperphosphorylation; (4) failed SOD1–Cn interactions contributes to Zn accumulation. Data provided in this study are in agreement with this hypothesis. We have observed reduced Cn protein amounts in rat spinal cord samples as determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1a, b). In unpublished data, we also observed reduced Cn phosphatase activity levels in Tg SOD1G93A mice (Fig. S2). We did not analyze Cn enzyme activity levels in spinal cord homogenates in rat due to insufficient amount of samples; however, we predict that low Cn levels reflect low Cn ativity. We have tested both CnA (~61 kDa calmodulin-binding catalytic subunit) and CnB (~19 kDa Ca2+/calmodulin-binding regulatory subunit) protein levels in spinal cord regions and found that CnA protein level was significantly lower in Tg SOD1G93A rat spinal cord regions as compare to WT (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, CnB subunit levels did not differ between the two groups (Fig. 1b). Although we observed a CnB upregulation pattern in thoracic region of Tg animals, this increase did not reach statistically significant level. CnB subunit is involved in the apoptotic reaction cascade in neurodegeneration [34]. We expected that CnB subunit upregulation would be observed in the spinal cord tissue homogenates. Based on these observations, we propose that Cn–SOD1 interaction fails due to alterations in the SOD1G93A mutation, then the less active Cn fails to dephosphorylate TDP-43; consequently, hyperphosphorylated TDP-43 begins to aggregate (Fig. 4). Because the impaired SOD1–Cn interaction is not stabilized, Zn ions would be dissociated from both Cn and SOD1 and form aggregates. The molar ratio between SOD1:Cn was determined to be 2:1 in in vitro conditions for proper Cn activity [31]. Even though TgSOD1G93A rat expresses more SOD1 (Fig. S3), Cn levels remained low in thoracic and lumbar spinal cord regions. Decreased Cn enzyme activity in lymphocytes from ALS patients was also reported in the literature [15].

Fig. 4.

Proposed model for Cn–SOD1 impaired interaction that leads for TDP-43 aggregation and Zn accumulation in ALS

Recent studies have suggested that Zn dyshomeostasis occurs in spinal cords of SOD1G93A transgenic mice and may contribute to motoneuron degeneration [35, 36]; however, these studies do not specify the region(s) of the spinal cord where Zn accumulation is prevalent. In this study, we found that greater Zn concentration is present in the lumbar spinal cord of SOD1G93A rats (Fig. 3) and mice (Fig. S4).

The labile Zn aggregation in neurons and astrocytes in the spinal cord of SOD1G93A transgenic mice supports the concept of the Zn dyshomeostasis in ALS [22]. Zinc is an essential cofactor for enzymatic activity and 10% of all mammalian proteins require Zn for proper folding [37]. Although Zn modulates the function of many other proteins, its homeostasis is poorly understood in health and in disease conditions. The elevated toxic levels of trace element Zn were reported in ALS patients reviewed by Smith and Lee [38], suggesting the link between environmental causes and an increased incidence of the disease. A possible approach would be to study the metal binding properties of SOD1, since SOD1 is a metalloprotein and binds to both Cu and Zn. The G93A SOD1 mutation selectively destabilizes the remote metal binding region (i.e., Zn and Cu binding region) [39]. We have proposed a model (Fig. 4) where unstable Zn-deficient SOD1 proteins may destabilize Cn that weakly binds Zn [31], causing impaired SOD1–Cn interaction. Subsequently, destabilized Cn fails to dephosphorylate TDP-43, leading to TDP-43 protein aggregation. However, this model needs to be tested in cell-based studies. Alterations in the metal-binding sites of another mutant SOD1G85R contributes to toxicity in SOD1-linked ALS [40]. This observation further supports the notion that Zn deficiency may contribute to the less stable SOD1 which enhances SOD1 aggregation in neuronal cells. This hypothesis was recently challenged by reports that SOD1 stabilization is not due to dimerization and proper metallation but disulfide formation between two SOD1 homodimer [40, 41]. In addition, liberated Zn may create local metal toxicity. There are extensive reports identifying the neurotoxic effects of Zn, however the mechanism remain unclear [42].

Calcineurin is a Ser/Thr specific phosphatase [16]. Ser amino acid enriched C-terminus region of TDP-43 (Fig. S5) is a potential substrate for Cn. Therefore, decreased activity of Cn may impair the dephosphorylation of TDP-43; hence, TDP-43 aggregations form in SOD1G93A Tg rat spinal cord tissue (Fig. 2, Fig. S6).

In conclusion, the complex biology of ALS necessitates the study of relevant biochemical events so that logical connections among the biomolecules and metal ions can be established. In this study, we have demonstrated that impaired SOD1G93A–Cn interaction gave rise to three important consequences in vivo; (1) reduced Cn enzyme levels, (2) labile Zn accumulation, and (3) TDP-43 aggregation. These events would potentially have contributed to ALS progression in the rat model. Further studies should design effective small molecules that maintain Cn activity so that hyperphosphorylated TDP-43 aggregation is controlled if not stopped. Stabilized Cn would not contribute labile Zn after dissociation from Cn molecule; therefore, Zn aggregation would be relatively less.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Justine Thomas, Megan Liberty, Tess Lamack, Mina Tawadrous, and Prabhal Sandhu for their contributions in experimental phase of this manuscript. Financial support is from KCU intramural grants awarded for AA and from GM103418 to JAS.

Authors’ Contributions

JMK, EB, AR, TN, JS, EA, MT, and IM performed the experiments, acquired data, and constructed the graphs. EA and JAS critically read the manuscript. JAS provided the rat spinal cord samples and critical reading the manuscript. AA planned and organized the experiments and results, sketched the illustration and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a intramural grant for AA from KCU and Summer Research Fellowship Awards for JMK and EB.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Jolene M. Kim, Elizabeth Billington have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Olanow CW. A radical hypothesis for neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16(11):439–444. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato S, et al. Histological evidence of redox system breakdown caused by superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) aggregation is common to SOD1-mutated motor neurons in humans and animal models. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;107(2):149–158. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0791-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann M, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arai T, et al. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351(3):602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen-Plotkin AS, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(4):211–220. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. TDP-43: a novel neurodegenerative proteinopathy. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17(5):548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiesel FC, Kahle PJ. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: cellular functions and implications for neurodegeneration. FEBS J. 2011;278(19):3550–3568. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilieva H, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Non-cell autonomous toxicity in neurodegenerative disorders: ALS and beyond. J Cell Biol. 2009;187(6):761–772. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wegorzewska I, Baloh RH. TDP-43-based animal models of neurodegeneration: new insights into ALS pathology and pathophysiology. Neurodegener Dis. 2011;8(4):262–274. doi: 10.1159/000321547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liachko NF, Guthrie CR, Kraemer BC. Phosphorylation promotes neurotoxicity in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. J Neurosci. 2010;30(48):16208–16219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2911-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong PA, Forman-Kay JD. A new phase in ALS research. Structure. 2016;24(9):1435–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumann M, et al. Phosphorylation of S409/410 of TDP-43 is a consistent feature in all sporadic and familial forms of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117(2):137–149. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0477-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann M, et al. TDP-43-positive white matter pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(3):177–183. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000248554.45456.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liachko NF, et al. The phosphatase calcineurin regulates pathological TDP-43 phosphorylation. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132(4):545–561. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1600-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferri A, et al. Activity of protein phosphatase calcineurin is decreased in sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosispatients. J Neurochem. 2004;90(5):1237–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klee CB, Draetta GF, Hubbard MJ. Calcineurin. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1988;61:149–200. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rusnak F, Mertz P. Calcineurin: form and function. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(4):1483–1521. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King MM, Huang CY. The calmodulin-dependent activation and deactivation of the phosphoprotein phosphatase, calcineurin, and the effect of nucleotides, pyrophosphate, and divalent metal ions. Identification of calcineurin as a Zn and Fe metalloenzyme. J Biol Chem. 1984;259(14):8847–8856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giri PR, et al. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis of calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase (calcineurin) catalytic subunit genes. DNA Cell Biol. 1992;11(5):415–424. doi: 10.1089/dna.1992.11.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sirangelo I, Iannuzzi C. The role of metal binding in the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-related aggregation of copperzinc superoxide dismutase. Molecules. 2017;22(9):1429. doi: 10.3390/molecules22091429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mera-Adasme R, et al. Destabilization of the metal site as a hub for the pathogenic mechanism of five ALS-linked mutants of copper, zinc superoxide dismutase. Metallomics. 2016;8(10):1141–1150. doi: 10.1039/C6MT00085A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, et al. Accumulation of labile zinc in neurons and astrocytes in the spinal cords of G93A SOD-1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34(2):221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiwari A, Hayward LJ. Mutant SOD1 instability: implications for toxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurodegener Dis. 2005;2(3–4):115–127. doi: 10.1159/000089616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuajungco MP, Lees GJ. Zinc metabolism in the brain: relevance to human neurodegenerative disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 1997;4(3–4):137–169. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1997.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, et al. Cupric ions induce the oxidation and trigger the aggregation of human superoxide dismutase 1. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e65287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Limpert AS, Mattmann ME, Cosford ND. Recent progress in the discovery of small molecules for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Beilstein J Org Chem. 2013;9:717–732. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao X. Effect of zinc exposure on HNE and GLT-1 in spinal cord culture. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30(1):121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parone PA, Cruz SD, Cleveland DW. Mitochondrial isolation and purification from mouse spinal cord. Bio Protoc. 2013;3(21):e961. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sengul G, et al. Atlas of the spinal cord. 1. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2013. p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alcock NW. A hydrogen-peroxide digestion system for tissue trace-metal analysis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1987;13(1):363–370. doi: 10.1007/BF02796647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agbas A, et al. Activation of brain calcineurin (Cn) by CuZn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) depends on direct SOD1-Cn protein interactions occurring in vitro and in vivo. Biochem J. 2007;405(1):51–59. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rakhit R, et al. An immunological epitope selective for pathological monomer-misfolded SOD1 in ALS. Nat Med. 2007;13(6):754–759. doi: 10.1038/nm1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakhit R, et al. Oxidation-induced misfolding and aggregation of superoxide dismutase and its implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(49):47551–47556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Y, Song W. Regulation of RCAN1 translation and its role in oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. FASEB J. 2013;27(1):208–221. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trumbull KA, Beckman JS. A role for copper in the toxicity of zinc-deficient superoxide dismutase to motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(7):1627–1639. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leal SS, et al. Aberrant zinc binding to immature conformers of metal-free copper-zinc superoxide dismutase triggers amorphous aggregation. Metallomics. 2015;7(2):333–346. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00278D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cox EH, McLendon GL. Zinc-dependent protein folding. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4(2):162–165. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(99)00070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith AL, Lee NM. Role of zinc in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007;8:131–143. doi: 10.1080/17482960701249241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Museth AK, et al. The ALS-associated mutation G93A in human copper-zinc superoxide dismutase selectively destabilizes the remote metal binding region. Biochemistry. 2009;48(37):8817–8829. doi: 10.1021/bi900703v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao X, et al. Structures of the G85R variant of SOD1 in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):16169–16177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801522200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chattopadhyay M, et al. The disulfide bond, but not zinc or dimerization, controls initiation and seeded growth in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) fibrillation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(51):30624–30636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.666503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malaiyandi LM, et al. Direct visualization of mitochondrial zinc accumulation reveals uniporter-dependent and -independent transport mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2005;93(5):1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.