Helicobacter pylori CagA is a secreted effector protein that contributes to gastric carcinogenesis. Previous studies showed that there is variation among H. pylori strains in the steady-state levels of CagA and that a strain-specific motif downstream of the cagA transcriptional start site (the +59 motif) is associated with both high levels of CagA and premalignant gastric histology.

KEYWORDS: CagA, Helicobacter pylori, gastric cancer, mRNA stability, peptic ulcer disease, transcription

ABSTRACT

Helicobacter pylori CagA is a secreted effector protein that contributes to gastric carcinogenesis. Previous studies showed that there is variation among H. pylori strains in the steady-state levels of CagA and that a strain-specific motif downstream of the cagA transcriptional start site (the +59 motif) is associated with both high levels of CagA and premalignant gastric histology. The cagA 5′ untranslated region contains a predicted stem-loop-forming structure adjacent to the +59 motif. In the current study, we investigated the effect of the +59 motif and the adjacent stem-loop on cagA transcript levels and cagA mRNA stability. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we found that mutations predicted to disrupt the stem-loop structure resulted in decreased steady-state levels of both the cagA transcript and the CagA protein. Additionally, these mutations resulted in a decreased cagA mRNA half-life. Mutagenesis of the +59 motif without altering the stem-loop structure resulted in reduced steady-state cagA transcript and CagA protein levels but did not affect cagA transcript stability. cagA transcript stability was not affected by increased sodium chloride concentrations, an environmental factor known to augment cagA transcript levels and CagA protein levels. These results indicate that both a predicted stem-loop structure and a strain-specific +59 motif in the cagA 5′ untranslated region influence the levels of cagA expression.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic, Gram-negative bacterium that persistently colonizes the stomach in more than 50% of the world’s population (1, 2). While most H. pylori-infected people remain asymptomatic, the presence of these bacteria is associated with an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and peptic ulcer disease (3–5). The risk of these diseases is influenced by H. pylori strain characteristics, host genetic characteristics, and environmental factors, such as diet (1–6).

H. pylori strains isolated from unrelated individuals display a high level of genetic diversity. One of the most prominent genetic differences among H. pylori strains is the presence or absence of a chromosomal region known as the cag pathogenicity island. This region encodes a secreted effector protein (CagA), as well as a type IV secretion system required for CagA entry into host cells (7, 8). Upon entry into host cells, CagA is tyrosine phosphorylated at conserved EPIYA motifs within the protein (9–12). Both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of CagA can interact with host cell components, causing alterations in cell signaling and morphology (9–14). Cellular alterations caused by CagA have been linked to malignant transformation, and hence, CagA has been designated a bacterial oncoprotein (9, 10, 15). Epidemiologic studies have shown an increased risk of both gastric cancer and peptic ulcer disease in people infected with cagA-positive H. pylori strains compared to people infected with cagA-negative strains (6, 16–22).

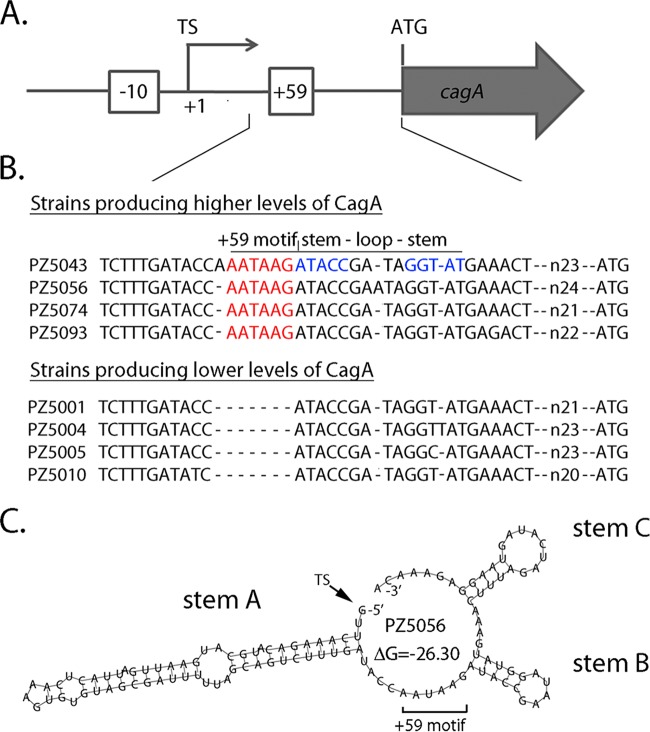

Previous studies showed that there is variation among H. pylori strains in the steady-state levels of the CagA protein (23, 24). A strain-specific motif downstream of the cagA transcriptional start site (the +59 motif), present in some strains but not others, was associated with high levels of CagA (Fig. 1A and B) (23, 24), and one study showed that strains containing the +59 motif stimulated higher levels of interleukin-8 production by cultured gastric cells than strains lacking the +59 motif (24). Importantly, this DNA motif was detected more commonly in strains isolated from persons with premalignant gastric histology than in strains from persons with uncomplicated gastritis (23, 24). These relationships were observed in studies of H. pylori strains from both Colombia and Portugal (23, 24).

FIG 1.

Schematic depicting a strain-specific +59 AATAAG motif in the cagA 5′ UTR. (A) Features upstream from cagA are illustrated. Numbering is based on designation of the cagA transcriptional start site (TS) as position +1. The +59 AATAAG sequence is located downstream of the cagA transcriptional start site and upstream from the cagA ATG start codon. The −10 sequence of the cagA promoter is also illustrated. (B) ClustalW analysis depicts naturally occurring diversity in the +59 region of 4 wild-type Colombian H. pylori strains that produce high levels of CagA and 4 wild-type Colombian strains that produce low levels of CagA (23). (C) RNAfold with default parameters (26) was used to analyze the secondary structure of the cagA 5′ UTR of strain PZ5056, which produces high levels of CagA (23). The region analyzed begins at the cagA transcriptional start site and ends at the nucleotide before the ATG translational start site. A minimum free energy (ΔG) value of −26.3 was predicted by RNAfold for the WT structure. Three predicted stem-loop structures (labeled stem A, stem B, and stem C) are similar to those predicted for the reference strains in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

The mechanism by which the +59 DNA motif influences CagA production is unknown. Since this motif is localized within the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the cagA transcript, we hypothesized that it might be a determinant of cagA transcript stability. By utilizing RNA secondary structure prediction programs (LocARNA [25] and RNAfold [26]), we detected a stem-loop structure immediately downstream of the +59 motif. Therefore, in the current study, we investigated the effect of the +59 motif and the adjacent stem-loop on steady-state cagA transcript levels and cagA mRNA stability.

RESULTS

Prediction of a stem-loop-forming structure adjacent to the strain-specific +59 motif in the cagA UTR.

Previous studies based on immunoblotting and real-time reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) experiments showed that the presence or absence of a strain-specific +59 motif downstream of the cagA transcriptional start site (Fig. 1A and B) influenced the levels of cagA expression (23, 24). As a first approach for analyzing this region, we examined the 5′ UTR of cagA from seven commonly used H. pylori laboratory strains that contain the +59 motif, using RNA structure prediction programs. Analysis using LocARNA (25), an mRNA secondary structure prediction algorithm that generates a consensus RNA structure based on multiple RNA input sequences, revealed three conserved, potential stem-loop-forming structures (stem A, stem B, and stem C) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). A clinical isolate (PZ5056) that contains the +59 motif and produces high levels of CagA (23) also contains 3 potential stem-loop structures in the cagA 5′ UTR (Fig. 1C) similar to those present in the seven laboratory strains (Fig. S1). The +59 motif is localized adjacent to stem-loop B (Fig. 1B and C and Fig. S1A and C).

We previously described a mutation in the cagA 5′ UTR, designated mut1 (GATA to ATAG), which resulted in decreased cagA transcript and protein levels (Fig. S2 and S3) (23). Of the 4 nucleotides altered in mut1, 3 form the forward stem of the stem-loop localized immediately downstream of the +59 motif (stem B) (Fig. S3A). The introduction of the mut1 mutation is predicted to result in an altered stem B structure (Fig. S3B), without any effects on stem A or stem C (compare Fig. S3B [mut1] with Fig. S3C [wild type {WT}]).

Figure S2 shows the results of experiments in which sequences upstream from cagA in strain 26695 (which expresses relatively low levels of CagA) were replaced by the corresponding sequences from strain PZ5056 (which expresses high levels of CagA) (23). The wild-type sequence from strain PZ5056 and a corresponding sequence harboring the mut1 mutation (Fig. S3) were individually introduced into strain 26695 (23). Increased cagA expression was observed at both the protein and transcriptional levels in the strain containing the wild-type PZ5056 sequence (i.e., 26695-cagA5056WT) compared to wild-type strain 26695 (23) (Fig. S2). In contrast, no increase in CagA protein levels or cagA transcript levels was observed in the strain harboring PZ5056 DNA containing the mut1 mutation (i.e., 26695-cagA5056mut1; Fig. S2).

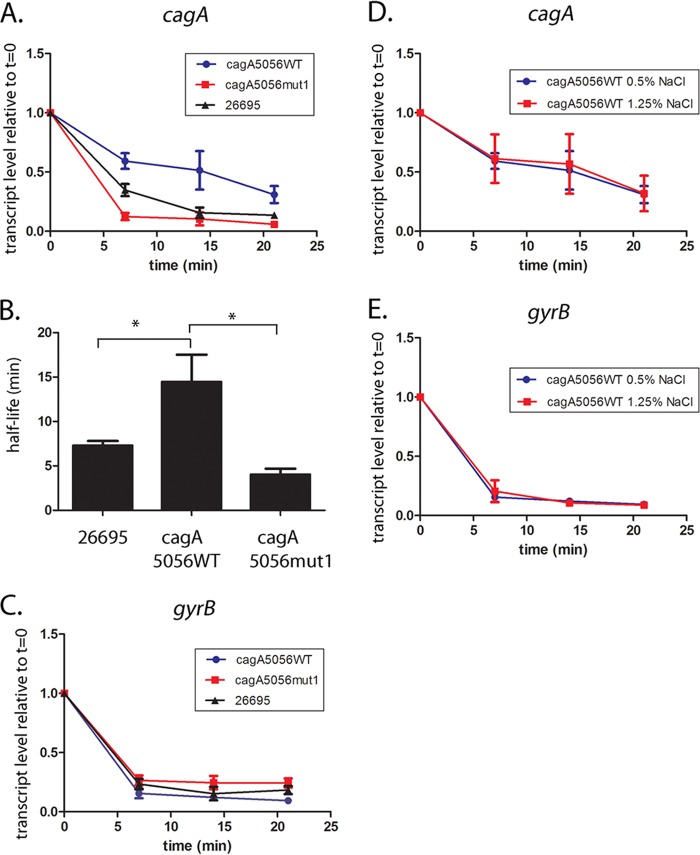

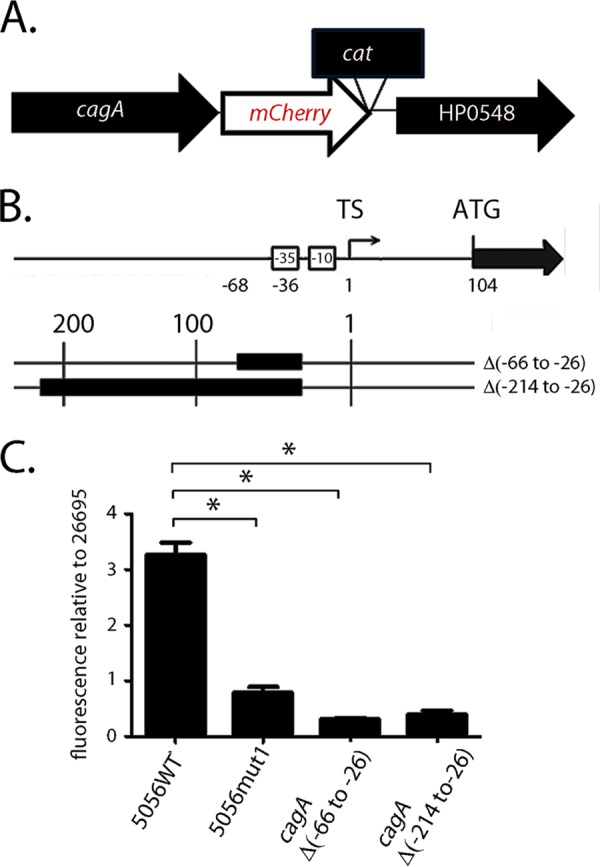

As another approach for analyzing cagA transcription, we generated an H. pylori cagA transcriptional reporter strain. To do this, we introduced a sequence coding for the mCherry fluorescent protein immediately downstream of the cagA translational stop codon (Fig. 2A). To test whether the levels of mCherry fluorescence reflected cagA transcriptional activity, we examined the effect of deletion mutations upstream of the cagA transcriptional start site {i.e., deletions of positions −66 to −26 [Δ(−66 to −26)] or positions −214 to −26 [Δ(−214 to −26)]}, which had previously been shown to reduce cagA expression (27). mCherry fluorescence was lower in strains harboring the Δ(−66 to −26) or Δ(−214 to −26) mutation than in the strain containing an unaltered sequence upstream from cagA (exhibiting a relative fluorescence level of 1) (Fig. 2B and C), demonstrating that expression of mCherry is dependent on sequences upstream of the transcriptional start site of cagA. We next analyzed fluorescent derivatives of strain 26695 harboring the cagA5056WT or cagA5056mut1 sequence. As shown in Fig. 2C, increased fluorescence was detected in the strain containing the cagA5056WT sequence compared to the control strain, in which the original sequence upstream from cagA remained intact. In contrast, an H. pylori strain containing a mut1 mutation (26695-cagA5056mut1) did not show a similar increase in fluorescence (Fig. 2C). These experiments demonstrate by multiple methods that the region targeted by the mut1 mutation regulates cagA expression.

FIG 2.

Effect of the mut1 mutation on cagA expression, analyzed in H. pylori strain 26695. (A) Sequences encoding an mCherry fluorescent reporter were introduced immediately downstream of the cagA translational stop codon in H. pylori 26695 or previously reported derivatives harboring mutations upstream of cagA (described below), resulting in cagA-mCherry transcriptional reporter fusions in these strains. (B) Two mutant strains contained nucleotide deletions (illustrated with black boxes) upstream of the cagA TS (27). Other mutants were generated by introducing sequences from strain PZ5056 into strain 26695 (23). Specifically, the nucleotides forming stem B in WT strain PZ5056 (5056WT, which produces high levels of the cagA transcript and the CagA protein) or the mut1 derivative (5056mut1) (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material) were introduced, together with flanking DNA sequences, upstream of cagA in strain 26695, replacing the endogenous 26695 sequences. In the 26695-cagA5056mut1 mutant, DNA sequences spanning 448 bp upstream and 685 bp downstream of the cagA transcriptional start site were introduced into strain 26695. In the 26695-cagA5056WT mutant, DNA sequences spanning 355 bp upstream and 639 bp downstream of the cagA transcriptional start site were introduced into strain 26695. (C) To monitor fluorescence, the H. pylori strains were grown overnight in brucella broth. Aliquots (1 ml) of the cultures (A600 = 0.5) were pelleted and resuspended in 200 µl of PBS. Fluorescence was detected using a microplate reader, and the fluorescence for each strain was then compared to the fluorescence obtained for WT H. pylori strain 26695 harboring the cagA-mCherry transcriptional fusion. All data points represent the results from analysis of 3 independent biological samples. The mean ± SEM is shown. Statistical significance was analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test (*, P < 0.05).

Analysis of cagA transcript stability.

Since the mut1 mutation is predicted to alter the cagA mRNA structure of stem-loop B, we hypothesized that this mutation might alter cagA transcript stability. To address this possibility, we first examined the stability of cagA mRNA at various time points following the addition of rifampin to broth cultures of strains 26695, 26695-cagA5056WT, and 26695-cagA5056mut1. As shown in Fig. 3A, the addition of rifampin resulted in a time-dependent decrease in cagA transcript levels in all three strains, but there were differences among the strains in the rates of cagA transcript decay. An H. pylori 26695 strain harboring the wild-type PZ5056 cagA upstream sequence (i.e., 26695-cagA5056WT) showed increased cagA transcript stability (calculated half-life, 14.4 min) compared to the cagA transcript stability in wild-type H. pylori strain 26695 (half-life, 7.1 min) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the strain harboring PZ5056 cagA DNA containing a mut1 mutation (i.e., 26695-cagA5056mut1) exhibited decreased cagA mRNA stability (half-life, 4.0 min) compared to a 26695 strain harboring cagA5056WT DNA (Fig. 3A and B). There was no difference in transcript stability of the control gene, gyrB, among the tested strains (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

The mut1 mutation affects cagA transcript stability. Overnight cultures were subcultured into fresh medium (starting OD600, 0.2) and cultured for 6 h. To inhibit transcription, rifampin (80 μg/ml; Sigma‐Aldrich) was added to each culture. Aliquots of the cultures were collected at the baseline (time zero [t = 0]) and 7, 14, or 21 min after addition of rifampin. Samples were transferred to the RNAlater Bacteria reagent (Qiagen) and stored at −80°C. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and real-time PCR were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The H. pylori strains used in the analysis included wild-type strain H. pylori 26695 and H. pylori 26695 strains in which the endogenous sequences upstream from cagA were replaced with the corresponding sequences from strain PZ5056 (26695-cagA5056WT or 26695-cagA5056mut1). (A to C) The H. pylori strains were cultured in medium containing 0.5% sodium chloride. (A) cagA transcript levels were normalized to those of 16S rRNA, and the respective normalized 16S rRNA values were compared to the normalized cagA values of the same cultures that did not receive rifampin treatment (i.e., the values at time zero). The y axis represents the relative cagA transcript level for each strain at the given time points after rifampin addition. (B) The data from panel A were used to plot a cagA transcript decay curve, and cagA transcript half-lives were calculated (see Materials and Methods). A one‐way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s multiple comparison was used to analyze statistical significance (*, P < 0.05). (C) Analysis of the same samples for gyrB expression. (D, E) Relative cagA and gyrB transcript levels at serial time points after addition of rifampin in H. pylori 26695 containing cagA5056WT sequences grown in medium containing 0.5% NaCl or 1.25% NaCl. All data points represent the results from analysis of at least 4 independent biological samples. For all experiments, the mean ± SEM is shown.

Previous studies showed that CagA production is increased when H. pylori strains are cultured in medium containing high sodium chloride concentrations (27–29). Therefore, we also compared the cagA transcript stability in H. pylori bacteria grown in medium with a high salt concentration (1.25% NaCl) to the cagA transcript stability in H. pylori bacteria grown in medium containing 0.5% NaCl. No difference in cagA or gyrB mRNA stability was observed when comparing cultures grown in these two media (Fig. 3D and E).

Analysis of cagA expression in strain PZ5056.

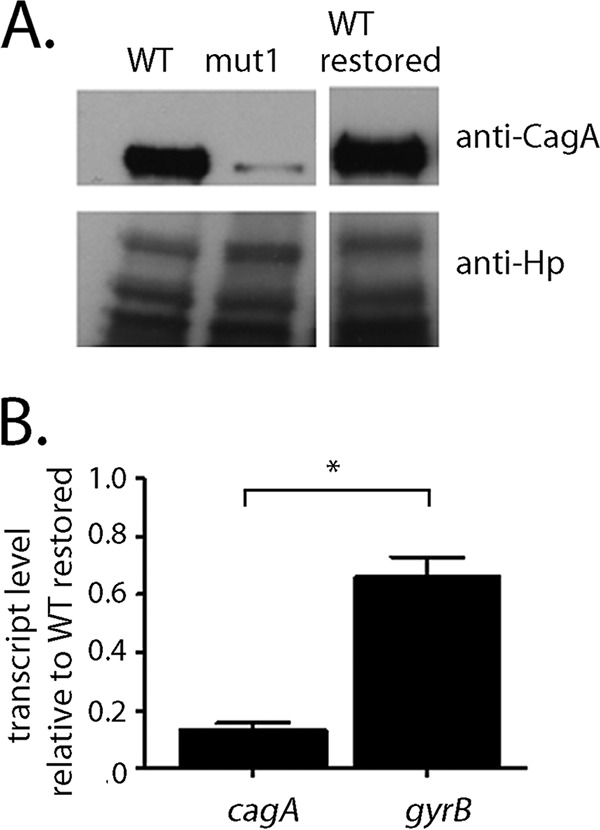

The experiments described thus far were conducted using H. pylori strain 26695, which produces relatively low levels of CagA (23). We next undertook a similar analysis of the mut1 mutation in strain PZ5056, which produces higher levels of CagA than strain 26695. The experimental design for these studies allowed us to directly analyze the effects of the mut1 mutation in strain PZ5056 without the presence of possible confounding factors associated with varying sites of recombination, which occurred when PZ5056 sequences were introduced into strain 26695 (described in the Fig. 2 legend). The introduction of the previously described mut1 mutation (Fig. S3) into strain PZ5056 yielded strain PZ5056-cagAmut1. As a control, we reintroduced the wild-type sequence from strain PZ5056 into strain PZ5056 (i.e., strain PZ5056-cagAR, or WT restored). As shown in Fig. 4A, H. pylori strain PZ5056-cagAmut1, containing the mut1 mutation, produced lower levels of CagA than strains containing the wild-type 5′ UTR (i.e., the WT or WT restored strain). Similarly, strain PZ5056-cagAR (containing a restored wild-type 5′ UTR motif) had a higher steady-state level of the cagA mRNA transcript than strain PZ5056-cagAmut1 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, gyrB transcript levels remained relatively similar when comparing PZ5056-cagAR and PZ5056-cagAmut1 (Fig. 4B). These results were consistent with what was observed in studies of the mut1 mutation in strain 26695.

FIG 4.

The mut1 mutation alters cagA expression in H. pylori strain PZ5056. The mut1 mutation (Fig. S3A) was introduced into the cagA 5′ UTR of strain PZ5056. As a control, the corresponding wild-type sequences were reintroduced into strain PZ5056 (i.e., WT restored). (A) Western blot analysis of CagA in wild-type H. pylori PZ5056, the PZ5056 mut1 mutant, and the WT restored strain was performed as described in Materials and Methods. anti-Hp, anti-H. pylori. (B) Real-time PCR was performed as described in the Materials and Methods to analyze the transcription of cagA and gyrB in the mut1 mutant. Quantification of the relative expression of cagA or gyrB in each strain was performed by first normalizing the cagA signal to the corresponding 16S rRNA signal. The normalized value for each sample was then divided by the normalized value for the restored PZ5056 strain (WT restored) to obtain a relative transcription level. All data points represent the results from analysis of at least 4 independent biological samples. The mean ± SEM is shown. Statistical significance was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test (*, P < 0.05).

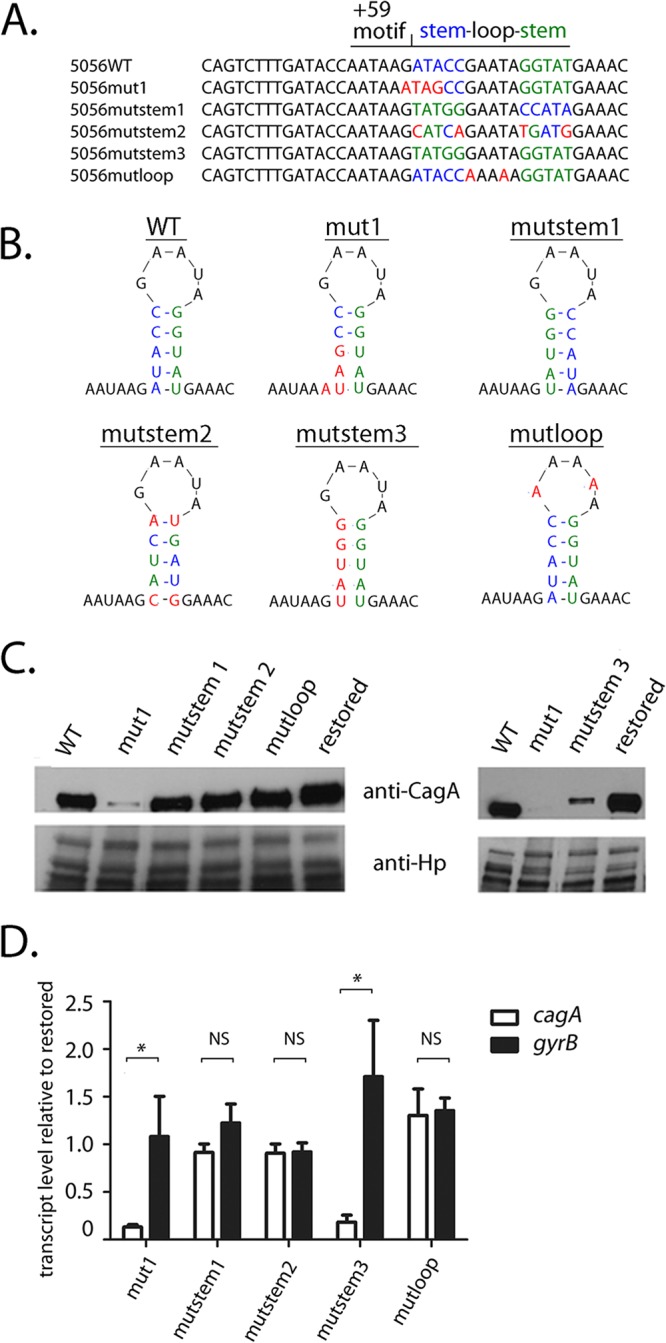

Role of the stem-loop in cagA transcript and protein levels.

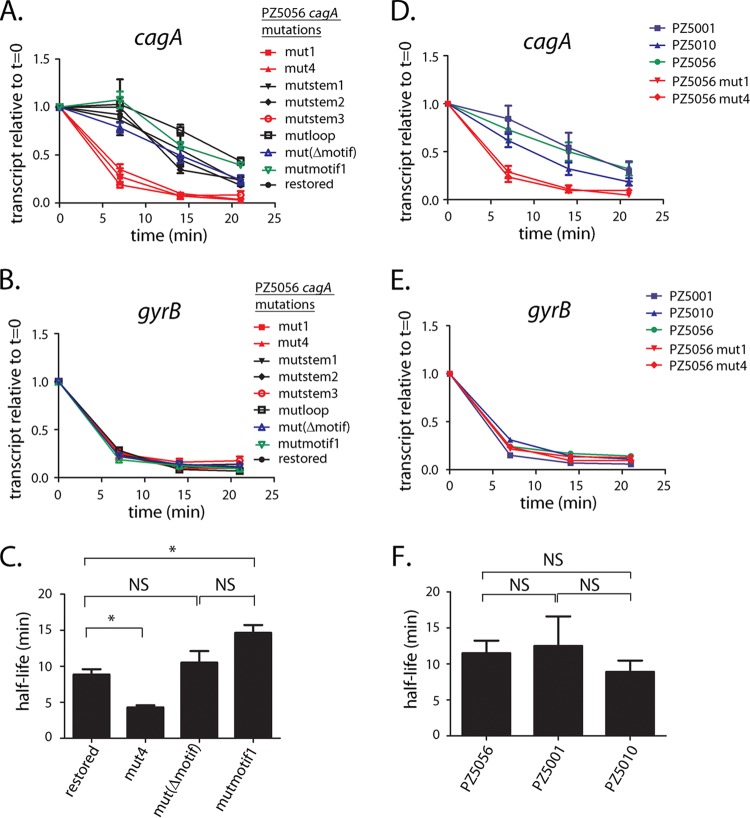

The mut1 mutation contains 3 nucleotide changes that alter stem B, as well as a single nucleotide change (G to A) immediately upstream of stem B, within the +59 AATAAG motif (Fig. 5A and Fig. S3A and B). To determine more specifically if the stem-loop structure influenced cagA mRNA levels, we generated mutant sequences that altered only nucleotide sequences that are predicted to form mRNA stem B, without altering the AATAAG motif. Three of these alter the primary sequence of stem B without altering the stem B structure (Fig. 5A and B and Fig. S4). In the first mutant (i.e., mutstem1), we interchanged the upstream stem-forming nucleotide sequences with those of the downstream stem-forming sequences. For the second mutant (mutstem2), changes were introduced into the upstream stem-forming sequences, together with compensatory nucleotide changes in the downstream bases that would allow base pairing with the altered upstream bases. For the third mutant (mutloop), we modified the nucleotides that form the loop (i.e., GAATA to AAAAA). The introduction of the mutstem1, mutstem2, and mutloop mutations into H. pylori resulted in cagA transcript and protein levels similar to those of the PZ5056 wild-type and PZ5056-cagAR strains (Fig. 5C and D). These results provide evidence that the primary sequences of the stem-loop-forming region are not critical for maintaining CagA protein and cagA transcript levels. We also examined CagA protein and transcript levels in an H. pylori strain in which the nucleotide sequences forming the upstream stem were altered to be identical to the nucleotide sequences of the downstream stem (mutstem3) (Fig. 5A and B and Fig. S4). The loss of base pairing between the upstream and downstream nucleotides in this mutant is predicted to result in the loss of the stem-loop structure (Fig. 5B and Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 5C and D, CagA protein and cagA transcript levels in H. pylori strains harboring the mutstem3 mutation were lower than those in strains harboring the wild-type stem-loop structure. The gyrB transcript levels were not altered in the mutstem3 strain (Fig. 5D). These data provide further evidence that the stem-loop structure is an important determinant of cagA transcript and CagA protein levels.

FIG 5.

Mutations in stem B affect cagA expression in H. pylori strain PZ5056. Mutations were introduced into the nucleotide sequences corresponding to stem B in strain PZ5056. In addition, sequences containing a wild-type stem-loop B were reintroduced into strain PZ5056 (i.e., restored), which served as a control. (A, B) The nucleotides forming the upstream portion of stem B in WT strain 5056 are shown in blue, while the nucleotides forming the downstream end of stem B are shown in green. Shown in red are nucleotide changes that alter the nucleotide composition of either the upstream stem, the downstream stem, or the loop portions of stem B. (A) In mutstem1, the upstream stem-forming nucleotide sequences were switched with those of the downstream stem-forming sequences. In mutstem 2, compensatory nucleotide changes were introduced into the downstream bases to allow for base pairing with nucleotide changes that had been introduced into the upstream stem-forming sequences. In mutstem3, the nucleotide sequences of the upstream stem were altered to be identical to the nucleotide sequences of the downstream stem, thus resulting in the loss of base pairing of stem B. In mutloop, the nucleotides forming the loop portion of stem B were altered from GAATA to AAAAA. (B) The sites of mutations relative to the predicted stem B structure. (C) Western blot analysis of CagA in the H. pylori PZ5056 strain and the mutant strains was performed as described in Materials and Methods. (D) The transcription of cagA and gyrB was analyzed by real-time PCR, which was performed as described in the Materials and Methods. For each sample, the cagA and gyrB signals were first normalized to the 16S rRNA signal. A relative transcription value was next calculated by dividing the normalized cagA or gyrB values for each sample by the corresponding normalized value for the restored PZ5056 strain. All data points represent the results from analyses of at least 4 independent biological samples. The mean ± SEM is shown. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Mann-Whitney test. Significant differences are shown (*, P < 0.05; NS, not statistically significant).

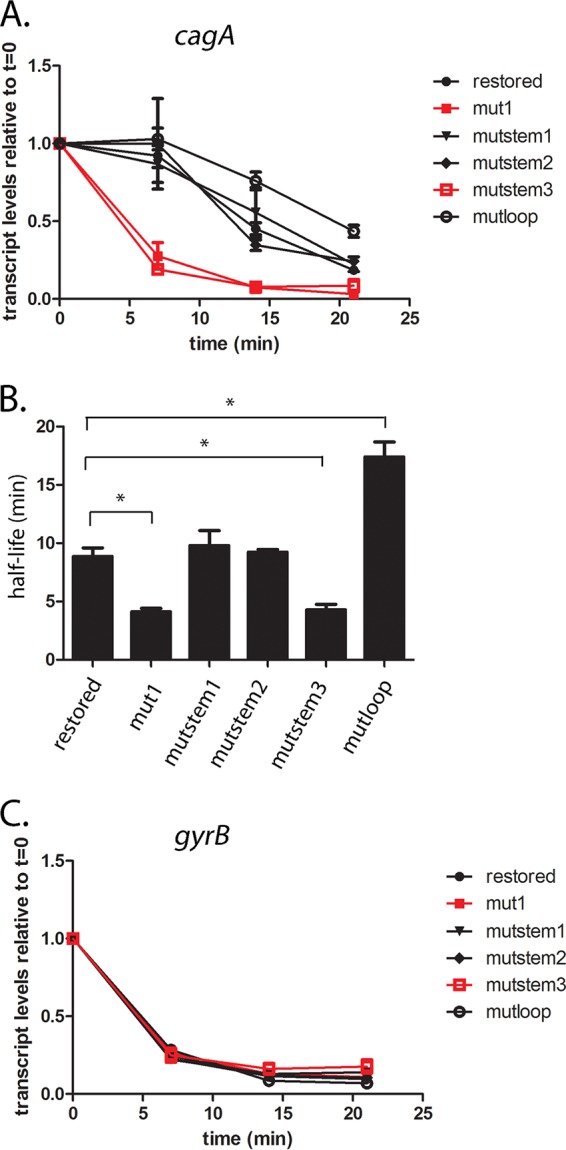

The stability of the H. pylori PZ5056 cagA transcript is affected by mutations to nucleotides forming stem-loop B.

We next examined the effect of the mutations described above on H. pylori PZ5056 cagA transcript stability. Consistent with the results for H. pylori strain 26695, we found that the mut1 mutation (Fig. 5A and Fig. S3 and S4) resulted in a substantial reduction in cagA transcript stability in strain PZ5056 (half-life, 4.1 min) compared to the cagA transcript stability in a strain harboring the wild-type 5′ UTR (i.e., PZ5056-cagAR [half-life, 8.9 min]) (Fig. 6A and B). A loss of transcript stability was also observed in strain PZ5056-cagAmutstem3 (Fig. S4), in which the stem-loop was disrupted (cagA transcript half-life, 4.1 min) (Fig. 6A and B). In contrast, the calculated cagA transcript half-lives in strains containing the mutstem1 and mutstem2 mutations (which maintain the stem B structure) were 9.8 min and 9.2 min, respectively, values similar to the half-life (8.9 min) observed for PZ5056-cagAR, which contains the wild-type 5′ UTR sequence (Fig. 6A and B). A mutation to the loop region of stem B (i.e., mutloop; Fig. S4) also did not decrease the cagA transcript half-life (17.3 min). Little or no difference in the decay of gyrB (Fig. 6C) was observed when comparing the wild-type and stem-loop B mutant strains. These results indicate that stem B influences the stability of the cagA transcript.

FIG 6.

Stem-loop B is important for cagA transcript stability in strain PZ5056. cagA transcript stability was analyzed in wild-type strain PZ5056 and PZ5056 derivatives in which the mut1, mutstem1, mutstem2, mutstem3, and mutloop mutations were introduced into the 5′ UTR of cagA. (A) The y axis represents relative cagA transcript levels for each strain at the given time points after addition of rifampin (80 µg/ml). The relative transcript levels of cagA are in comparison to the transcript levels found in H. pylori cultures before rifampin was added. All data points represent the results from analyses of at least 3 independent biological samples. The mean ± SEM is shown. (B) cagA transcript half-lives were calculated as described in the Materials and Methods using data from panel A. The mean ± SEM of the transcript half-lives is shown. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s multiple comparison (*, P < 0.05). (C) Analyses of gyrB transcript levels in the indicated strains.

Mutation of the +59 motif affects cagA transcript and CagA protein levels but not cagA transcript stability.

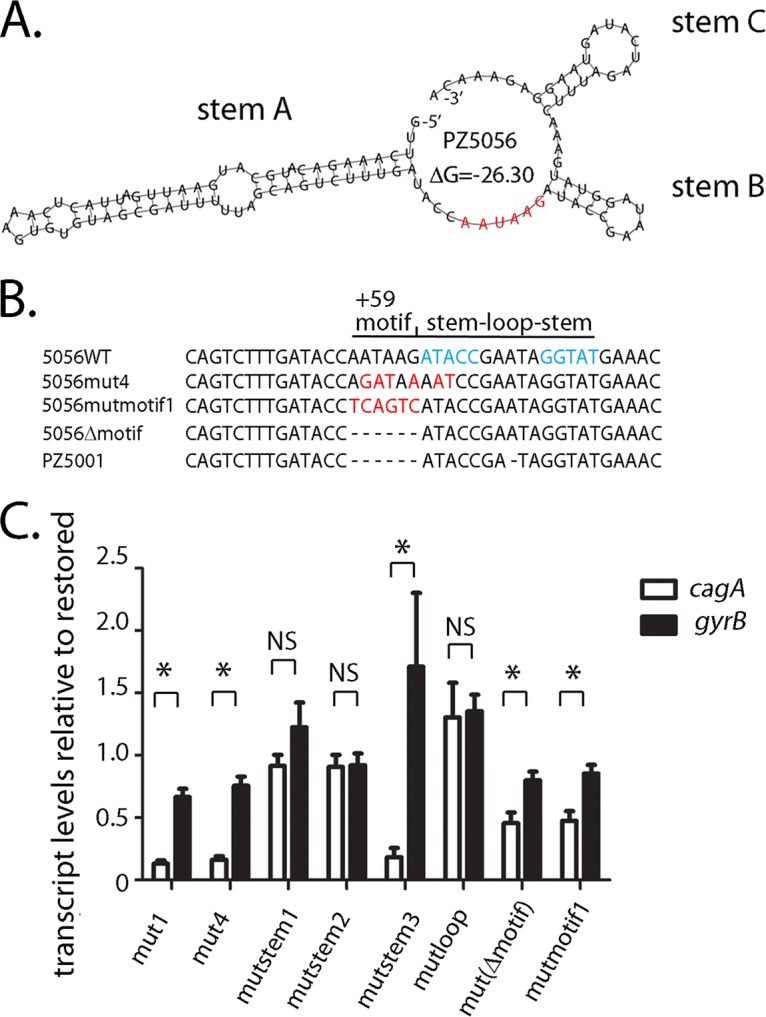

Since the strain-specific +59 AATAAG motif is located immediately upstream of stem B (Fig. 5A and 7A), we hypothesized that the presence or absence of an intact AATAAG motif might influence cagA transcript levels. To explore this possibility, we introduced two separate mutations (i.e., mutΔmotif and mutmotif1) into the AATAAG motif, without altering the nucleotides forming stem B (Fig. 7B; Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. S5, stem B is predicted to be intact in both of these mutants. In the strain with the mutmotif1 mutation, the nucleotides AATAAG were replaced with nucleotides TCAGTC (Fig. S4). In the strain with the mutΔmotif mutation (Fig. S4), the AATAAG nucleotides were deleted, resulting in a DNA sequence in this region similar to that which is found in Colombian H. pylori strains that produce low levels of CagA, such as strain PZ5001 (Fig. 1; Fig. 7B) (23). The resulting stem B structure of the mutΔmotif mutant is similar to that observed in strain PZ5001 (Fig. S5). We also analyzed a third mutation (i.e., mut4; Fig. S4) that contained multiple nucleotide changes to the +59 motif (i.e., AATAAG to AGATAA), as well as nucleotide changes that resulted in the absence of stem-loop B in the mut4 structure (Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 7C, cagA transcript levels were reduced in strains harboring either mutΔmotif or mutmotif1 mutations (which specifically target the +59 motif, without altering the stem-loop structure). The magnitude of the reduction in cagA transcript levels in these mutants was, however, less than that observed in strains containing the mut1, mut4, or mutstem3 mutation (affecting stem B). Thus, both the stem-loop structure and the +59 AATAAG motif influence the levels of cagA expression.

FIG 7.

Mutations to the AATAAG +59 motif alter cagA expression in strain PZ5056. (A) The AATAAG motif is shown in red (23) and is located immediately upstream of stem B. (B) The nucleotides forming the stem structure of stem B in wild-type PZ5056 are shown in blue. Three different mutations were introduced into the PZ5056 cagA 5′ UTR to alter the +59 motif. Nucleotide changes are shown in red. The mut4 mutation alters the AATAAG motif, as well as the second and third nucleotides of the upstream stem of stem B. The mutmotif1 mutation alters nucleotides in the AATAAG motif, while the Δmotif mutation deletes the AATAAG mutation. (C) The transcription of cagA and gyrB in strains containing the indicated mutations was analyzed by real-time PCR, as described in the Materials and Methods. For each sample, the cagA and gyrB signals were first normalized to the 16S rRNA signal. A relative transcription value was next calculated by dividing the normalized cagA or gyrB values for each sample by the corresponding normalized value for the restored PZ5056 strain. All data points represent the results from analyses of at least 4 independent biological samples. The mean ± SEM is shown. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Mann-Whitney test (*, P < 0.05; NS, not statistically significant).

We next investigated whether mutagenesis of the +59 motif affected cagA transcript stability. As shown in Fig. 8A, the addition of rifampin resulted in a rapid decay of the cagA transcript in strains harboring the mut1, mut4, or mutstem3 mutations, which alter the structure of stem B (half-lives for the three cagA transcripts, 4.1 min, 4.2 min, and 4.1 min, respectively) (Fig. 6B and 8C and Fig. S4). In contrast, the cagA transcript half-lives for strains harboring either a deletion of the +59 motif (i.e., mutΔmotif) or nucleotide alterations of the +59 motif (i.e., mutmotif1), which maintain an intact stem-loop structure, were 10.5 min and 14 min, respectively (Fig. 8C and Fig. S4). The cagA transcriptional half-lives in these strains were not reduced compared to those observed in H. pylori strains containing cagA UTRs harboring WT, mutstem1, or mutstem2 sequences, in which the stem-loop B structure is intact (half-lives, 8.9 min, 9.8 min, and 9.2 min, respectively) (Fig. 6B; Fig. S4). Thus, neither deletion of the +59 motif (i.e., mutΔmotif) nor mutation of the motif (AATAAG to TCAGTC in the mutmotif1 mutant) resulted in a loss of cagA transcript stability.

FIG 8.

The +59 motif does not affect cagA transcript stability. (A to C) cagA transcript stability was analyzed in WT strain PZ5056 and PZ5056 derivatives that contained mutations to the AATAAG +59 motif (see Fig. S3 to S5 in the supplemental material). For the RNA stability assays, rifampin (80 μg/ml; Sigma‐Aldrich) was added to each culture to inhibit transcription. Samples from each culture were collected at time zero (t = 0), 7, 14, or 21 min after addition of rifampin. Each sample was processed for RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and real-time PCR, as described in the Materials and Methods. cagA transcript levels at each time point after rifampin treatment were normalized to the corresponding 16S rRNA transcript levels. (A) Each normalized cagA value was compared to the value for the same culture that did not receive rifampin treatment (i.e., the value at time zero). The y axis represents the relative cagA transcript level for each strain at the given time points after rifampin addition. (B) Analysis of the same samples for gyrB expression. (C) cagA transcript half-lives, calculated as described in the Materials and Methods, using the data shown in panel A. The mean ± SEM is shown. (D, E) cagA transcript stability was compared in WT strain PZ5056, mutant strains that contained either the mut1 or mut4 mutation, and H. pylori wild-type strains PZ5001 and PZ5010, which do not contain the AATAAG motif (23). All data points represent the results from analyses of at least 3 independent biological samples. The mean ± SEM is shown. (F) cagA transcript half-lives for the data shown in panel D. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s multiple comparison (*, P < 0.05; NS, not significant).

cagA transcript stability in wild-type Colombian strains PZ5001 and PZ5010.

To further investigate the role of the AATAAG motif in transcript stability, we examined cagA transcript stability in wild-type H. pylori strains PZ5001 and PZ5010 (23, 30), in which stem B is present but the +59 AATAAG DNA motif is absent (shown for PZ5001 in Fig. S5). Consistent with the finding that mutations to the +59 motif did not affect transcript stability (Fig. 8A and C), cagA transcript half-lives for strains PZ5001 and PZ5010 were 12.4 min and 8.9 min, respectively (Fig. 8D and F). These half-lives were similar to the 11.4-min half-life observed for strain PZ5056 (which contains both an intact stem B and the AATAAG motif) (Fig. 8F) and longer than the cagA transcript half-lives observed in strains with defects in the stem-loop structure (PZ5056-cagA mut1 [half-life, 4.1 min; Fig. 6B] and PZ5056-cagA mut4 [half-life, 4.2 min; Fig. 8C]). In contrast, the rate of gyrB transcript decay was similar when comparing strains PZ5001, PZ5010, PZ5056-cagA mut1, PZ5056 mut4, and WT PZ5056 (Fig. 8E).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed the functional properties of a region in the cagA 5′ UTR that contains a predicted stem-loop structure and an adjacent +59 AATAAG motif. The stem-loop structure was present in all of the wild-type H. pylori strains analyzed in this study, whereas the +59 motif was present in some strains but not others (23, 24). Previous studies showed that strains containing the +59 motif produce higher levels of CagA than strains that lack the +59 motif, and strains containing the +59 motif were associated with premalignant gastric histology (23, 24). We report in the current study that both the +59 motif and the adjacent stem-loop structure (stem-loop B) influence the levels of cagA expression.

When stem-loop B was experimentally mutated, the stability of cagA transcripts was reduced compared to the stability of cagA transcripts in strains with an intact stem-loop B. In contrast, H. pylori strains harboring corresponding mutations that preserve the stem-loop structure did not exhibit a loss of cagA transcript stability. This finding suggests that the stem-loop, rather than the primary nucleotide sequence forming the stem or loop structure, is important for cagA transcript stability.

H. pylori strain 26695 contains the +59 AATAAG motif but produces relatively low levels of CagA compared to other strains, such as strain PZ5056 (23). An examination of the nucleotide sequences surrounding the AATAAG motif in strain 26695 revealed nucleotide deletions downstream of the AATAAG motif (23). For example, the nucleotide sequence CCGAATAGGTAT immediately follows the AATAAG motif in strain PZ5056 (23), whereas in H. pylori 26695, the AATAAG motif is followed by the nucleotide sequence CCGATAGTAT. The underlined guanine residue, present in the cagA 5′ UTR of PZ5056 but absent from the cagA 5′ UTR of H. pylori 26695, is one of the nucleotides that forms the stem structure downstream of the AATAAG motif. The absence of this nucleotide would therefore likely affect the stem-loop structure and would be predicted to have an effect on cagA mRNA stability and CagA protein levels. Consistent with this hypothesis, the introduction of the corresponding nucleotide deletion in the 5′ UTR of cagA of PZ5056 resulted in a reduction of both cagA transcript and CagA protein levels (23).

While the AATAAG +59 motif is not predicted to be part of the stem-loop structure, these nucleotides are important determinants of cagA transcript and protein levels. For example, mutations in the cagA 5′ UTR of PZ5056 (either a change of the nucleotide sequence [i.e., AATAAG to TCAGTC] or a deletion of the nucleotides AATAAG) resulted in a reduction in both cagA transcript and CagA protein levels. This result is consistent with the reduction in cagA expression observed in a previously described strain harboring a mut2 mutation, in which the AATAAG sequence was altered to AAATTG (23). The deletion of the AATAAG +59 motif from strain PZ5056 results in a cagA 5′ UTR that closely resembles the cagA 5′ UTR found in various wild-type H. pylori strains, such as strain PZ5001. Strain PZ5056 produces relatively high levels of CagA, whereas PZ5001 produces much lower levels of CagA (23). Thus, the difference in CagA levels produced by PZ5056 and PZ5001 is attributable at least in part to the presence or absence of the +59 AATAAG sequence.

In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that the +59 motif influences cagA transcript stability and found that the presence or absence of this motif does not affect cagA transcript stability. For instance, mutants harboring a deletion or changes to the AATAAG +59 motif had cagA transcript stabilities similar to those of the wild-type strain. In addition, the rates of decay of cagA mRNA in wild-type H. pylori Colombian strains PZ5001 and PZ5010, which lack the +59 motif, were similar to the rate of decay observed in H. pylori strain PZ5056, where the +59 motif is present.

A previous study identified a σ28 binding site (i.e., CCGAT) that drives the production of a second cagA transcript upon H. pylori attachment to gastric epithelial cells (31). The identified σ28 site is located immediately downstream of the AATAAG motif. An examination of the PZ5056 cagA sequence reveals a possible σ28 site (i.e., CCGAAT) associated with the predicted AATAAG-associated stem-loop structure. Our experiments, however, suggest no apparent effect of the σ28 binding site on cagA transcript stability under the culture conditions used in these experiments. For instance, when mutations to the putative σ28 binding site were introduced (mutstem1, mutstem2, or mutloop mutations), the cagA transcript stability was similar to the cagA transcript stability observed in strains containing the wild-type PZ5056 sequence. Similarly, cagA transcript stability was adversely affected in the mut1 and mut4 strains, even though the putative σ28 binding site remained present.

Further studies will be required to elucidate the mechanism(s) by which the AATAAG motif influences cagA expression. Several possibilities can be considered. For example, previous studies have shown that DNA sequences in the 5′ UTR of genes can form terminator or antiterminator structures that either prematurely arrest transcription or prevent the early termination of ongoing transcription (32–34). The formation and stabilization of these antiterminator structures may involve RNA-binding proteins (35–38). Competition in the formation of antiterminator/terminator structures in the leader regions of these transcripts is known to modulate gene transcription in response to environmental signals (32–34). The +59 motif could potentially be involved in the formation of an antiterminator complex, which could account for the higher level of cagA transcription in H. pylori strains containing the +59 motif than in strains where the +59 motif is absent. An alternate possibility is that the +59 motif is a binding site for small RNAs or proteins that modulate transcription.

Finally, in addition to examining the role of the AATAAGA motif in transcript stability, we investigated a potential effect of sodium chloride, a known inducer of cagA expression (27–29), on cagA transcript stability and found that high salt concentrations did not affect cagA transcript stability. Thus, in contrast to an effect of the salt concentration on the posttranscriptional stability of vacA (39), we did not observe an effect of high salt concentrations on cagA transcript stability.

In summary, the current study provides new insights into features of the cagA 5′ UTR that are determinants of cagA expression. These results provide a better understanding of the mechanisms by which strain-specific variation in this region influences the levels of cagA expression, as well as the development of premalignant and malignant changes in the stomach (23, 24).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All H. pylori cultures were grown at 37°C in ambient air supplemented with 5% CO2. The H. pylori strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. For routine growth, the H. pylori strains were maintained on Trypticase soy agar plates containing 5% sheep blood. For broth cultures, H. pylori strains were grown in sulfite-free brucella broth (BB) (40) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (BB-FBS). When necessary, the H. pylori cultures were grown on BB-FBS medium containing streptomycin (25 µg/ml) or chloramphenicol (5 µg/ml). Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium containing the following antibiotics at the indicated final concentrations: ampicillin at 50 µg/ml, chloramphenicol at 25 µg/ml, or streptomycin at 25 µg/ml.

TABLE 1.

H. pylori strains and plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pMCHBH | pUC57 containing mCherry | This study |

| pcagA-MCH | pGEM T Easy vector containing cagA 3′ end::mCherry transcriptional fusion | This study |

| pcagA-MCHCAT | pcagA-MCH containing cat | This study |

| p5056cagA-3 | pGEM T Easy vector containing cagA, contains sequences 500 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the cagA ATG initiation codon of PZ5056 | This study |

| pcagA::cat-rpsL | p5056cagA-3, contains cagA::cat rpsL | This study |

| p5056cagAmut1 | p5056cagA-3 with a mutation in the +59 motif and stem B, resulting in an altered stem B structure (Fig. S4) | This study |

| p5056cagAmut4 | p5056cagA-3 with a mutation in the +59 motif and stem B, resulting in an altered stem B structure (Fig. S4) | This study |

| p5056cagAmutstem1 | p5056cagA-3 with a mutation in stem B of the cagA 5′ UTR; the structure of stem B is retained (Fig. S4) | This study |

| p5056cagAmutstem2 | p5056cagA-3 with a mutation in stem-loop B of the cagA 5′ UTR; the structure of stem B is retained (Fig. S4) | This study |

| p5056cagAmutstem3 | p5056cagA-3 with a mutation in stem B of the cagA 5′ UTR, resulting in an altered stem B structure (Fig. S4) | This study |

| p5056cagAmutloop | p5056cagA-3 with a mutation in the loop of stem-loop B (Fig. S4) | This study |

| p5056cagAmutmotif1 | p5056cagA-3 with a mutation in the +59 motif (Fig. S4) | This study |

| p5056cagAmutΔmotif | p5056cagA-3 with a deletion of the +59 motif (Fig. S4) | This study |

| H. pylori strains | ||

| 26695 | Wild-type H. pylori | 48 |

| 26695-cagApromΔ(−66 to −26) | 26695 containing deletion of cagA promoter, ΔrdxA | 27 |

| 26695-cagApromΔ(−214 to −26) | 26695 containing deletion of cagA promoter, ΔrdxA | 27 |

| 26695-cagA5056WT | 26695 containing the 1-kb promoter fragment of cagA from H. pylori PZ5056, ΔrdxA | 23 |

| 26695-cagA5056mut1 | 26695 containing the 1-kb promoter fragment of cagA from H. pylori PZ5056, mut1 mutation, ΔrdxA | 23 |

| HpcagAMCH1 | 26695 containing cagA-mCherry-cat | This study |

| HpcagAMCH2 | 26695-cagA5056WT containing cagA-mCherry-cat | This study |

| HpcagAMCH3 | 26695-cagA5056mut1 containing cagA-mCherry-cat | This study |

| HpcagAMCH4 | 26695-cagApromΔ(−66 to −26) containing cagA-mCherry-cat | This study |

| HpcagAMCH5 | 26695-cagApromΔ(−214 to −26) containing cagA-mCherry-cat | This study |

| PZ5056 | Clinical isolate from a gastric cancer patient | 23, 30 |

| PZ5056 rpsL-K43R | PZ5056 rpsl-K43R | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAcat-rpsL | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R containing cagA::cat-rpsL | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAR | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R with a restored +59 motif | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAmut1 | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R with the cagAmut1 mutation | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAmut4 | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R with the cagAmut4 mutation | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAmutstem1 | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R with the cagAmutstem1 mutation | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAmutstem2 | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R with the cagAmutstem2 mutation | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAmutloop | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R with the cagAmutloop mutation | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAmutmotif1 | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R with the cagAmutmotif1 mutation | This study |

| PZ5056-cagAmutΔmotif | PZ5056 rpsL-K43R with deletion of the +59 motif | This study |

Mutagenesis of the +59 DNA motif in H. pylori strain PZ5056.

To evaluate the effect of the +59 DNA sequences on cagA expression, unmarked mutations were introduced upstream of the cagA open reading frame (ORF) using a previously described counterselection protocol involving a cat-rpsL cassette (41–44). Briefly, streptomycin-resistant mutants were generated by transforming H. pylori strain PZ5056 with a nonreplicating plasmid containing a cloned H. pylori rpsL gene harboring a lysine-to-arginine mutation at codon 43 of rpsL (42, 44). As a next step, the plasmid pcagA::cat-rpsL was generated by PCR amplification of a region extending from approximately 500 bp upstream of the cagA translational start site to 500 bp downstream of the cagA translational start site from H. pylori PZ5056 with primers 5′-GAAGCTGTCTTTGAAAATCTGTCC-3′ and 5′-AATATCCAACCAATCCCCACCAG-3′. The PCR product was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and the resulting plasmid, p5056cagA-3, was used as a template for inverse PCR with primers 5′-CATTGTTTCTCCTTACTAT-3′ and 5′-ACTAACGAAACTATTGATCAA-3′. A cat-rpsL cassette (41, 42), conferring resistance to chloramphenicol mediated by the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene from Campylobacter coli and susceptibility to streptomycin mediated by the intact rpsL gene from H. pylori 26695, was ligated to the inverse PCR product. The resultant recircularized plasmid (pcagA::cat-rpsL), which is unable to replicate in H. pylori, was transformed into the streptomycin-resistant H. pylori PZ5056 rpsL-K43R strain. This allowed the insertion of a cat-rpsL cassette immediately downstream of the ATG initiation site of cagA. Single colonies resistant to chloramphenicol (5 µg/ml) but sensitive to streptomycin (25 µg/ml) were selected. The loss of CagA production in the PZ5056 cagA::cat-rpsL mutant strain was confirmed by immunoblot analyses. In addition, insertion of the cat-rpsL cassette into the cagA gene was confirmed by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.

To generate mutations in the promoter region of the cagA gene, plasmid p5056cagA-3 (described above) was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange II XL site‐directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, UK) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The presence of the expected mutations was confirmed by DNA sequencing. H. pylori strain PZ5056 cagA::cat-rpsL was transformed with the plasmids, and streptomycin-resistant transformants were selected. These streptomycin-resistant colonies result from recombination events in which the cat-rpsL insertion in the cagA ORF was deleted. Deletion of the cat-rpsL insertion in the ORF of cagA is expected to result in the restoration of CagA production. Therefore, all H. pylori transformants were subsequently screened for CagA production by immunoblotting. DNA sequencing was also used to ensure the introduction of the desired mutations.

Western blot analysis.

To analyze the levels of CagA, H. pylori strains were inoculated into BB-FBS and grown overnight. The bacteria were then inoculated into fresh BB-FBS at an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1, and following 15 h of growth, the cultures (A600, 0.5 to 0.6) were harvested and frozen at −80°C. H. pylori cells were lysed using NP-40 lysis buffer as previously described (23, 27), and lysates (5 µg of protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. CagA production was detected using a 1:10,000 dilution of a CagA-specific polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Real-time RT-qPCR.

To analyze cagA transcript levels, overnight cultures of H. pylori were inoculated into fresh BB-FBS at an initial OD600 of 0.3. Following 6 h of growth, total RNA was isolated from H. pylori using the TRIzol reagent (Gibco) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA samples were digested with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega) to remove contaminating DNA and subjected to a cleanup step using RNAeasy columns (Qiagen). Purified RNA (100 ng) was then used for cDNA synthesis with random hexamer primers using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). The cDNA was diluted 1:20 prior to real-time reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Real-time RT-qPCR was carried out using an ABI real-time PCR machine, with SYBR green used as the fluorochrome (iTaq universal SYBR mix; Bio-Rad). The abundance of the transcript was calculated using the ΔΔCT threshold cycle (CT) method, with the abundance of each transcript signal being normalized to that of the 16S rRNA internal control. The normalized transcript signal for each biological sample was then compared to similarly normalized values obtained with control samples. The primers used for real-time RT-qPCR analysis were as follows: 5′-GGAGTACGGTCGCAAGATTAAA-3′ and 5′-CTAGCGGATTCTCTCAATGTCAA-3′ for 16S rRNA, 5′-GAGTCATAATGGCATAGAACCTGAA-3′ and 5′-TTGTGCAAGAAATTCCATGAAA-3′ for cagA, and 5′-CGTGGATAACGCTGTAGATGAGAGC-3′ and 5′-GGGATTTTTTCCGTGGGGTG-3′ for gyrB.

mRNA stability assays.

H. pylori strains were grown overnight in BB-FBS, subcultured into fresh BB-FBS (starting OD600, 0.2), and grown for 6 h. Rifampin (80 μg/ml; Sigma‐Aldrich) was next added to the culture in order to inhibit transcription (45, 46), and aliquots were collected at 7, 14, and 21 min after addition of rifampin. The bacteria were pelleted and resuspended in RNAlater (Ambion) for 40 min. The cell suspensions were centrifuged at 3,500 × g, the supernatants were decanted, and the bacterial pellets were stored at −80°C. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and real-time RT-qPCR were next performed as described above to determine the relative level of cagA expression for each strain at the given time points after rifampin addition. To determine the half-life of the cagA transcript, the natural logarithm of the level of relative cagA expression was calculated and plotted against time (39). The slope of each line (i.e., half-life coefficient K) was used in the formula t1/2 = ln(2)/K to calculate the half‐life (t1/2) of cagA mRNA for each strain.

Fluorescent reporter strain construction.

To generate H. pylori strains harboring an mCherry fluorescent reporter, a 734-bp DNA fragment containing the ribosome binding site of cagA followed by the ORF encoding mCherry, a variant of the Discosoma red (DsRed) protein (47), was synthesized (GenScript USA Inc., Piscataway, NJ). Flanking 5′ BamHI and 3′ HindIII restriction sites were included in the synthesized gene sequences, and the synthesized DNA was cloned into a pUC57 vector, yielding plasmid pMCHBH. To allow insertion of the mCherry reporter immediately downstream of the cagA gene, we PCR amplified a 0.7-kb product from the 3′ end of cagA with primers 5′-AATGAAAAAGCGACCGGTAT-3′ and 5′-TTCTGATCGCAAGCGTCTTTTTTGGG-3′, using genomic DNA from H. pylori strain 26695. This DNA fragment contained nucleotide sequences 362 bp upstream and 351 bp downstream of the cagA translational stop codon. The PCR product was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector, and the resulting plasmid was used as a template for inverse PCR with reverse primer 5′-CATGGATCCTTAAGATTTTTGGAAACCACCTTTTGTATTAAC-3′ and forward primer 5′-CCAAGCTTCAGATCTAGGATTAAGGAATACCAAAAACGCAAAAACCACCCCTTG-3′. The restriction sites introduced into the primer sequences are underlined. The reverse primer contains a BamHI (GGATCC) restriction site, while the forward primer contains HindIII (AAGCTT) and BglII (AGATCT) restriction sites. The inverse PCR product was digested with BamHI and HindIII and ligated with a BamHI-HindIII mCherry fragment from plasmid pMCHBH. A selectable marker was next added to the cagA-mCherry plasmid (pcagA-MCH) by insertion of a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) cassette into the BglII site of pcagA-MCH. Following transformation of the H. pylori strains with pcagA-MCHCAT, chloramphenicol-resistant transformants were selected. To monitor fluorescence, H. pylori strains were grown overnight in brucella broth. Aliquots (1 ml) of the cultures (A600 = 0.5) were pelleted and resuspended in 200 µl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fluorescence was quantified using a FLx800 microplate reader (BioTek).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work described in this paper was supported by NIH grants AI118932, AI039657, and CA116087 and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (Merit Review grant BX000627).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00692-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. 2009. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: ancient history, modern implications. J Clin Invest 119:2475–2487. doi: 10.1172/JCI38605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. 2009. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology 136:1863–1873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amieva MR, El-Omar EM. 2008. Host-bacterial interactions in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology 134:306–323. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox JG, Wang TC. 2007. Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest 117:60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. 2002. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med 347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cover TL. 2016. Helicobacter pylori diversity and gastric cancer risk. mBio 7:e01869-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01869-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer W. 2011. Assembly and molecular mode of action of the Helicobacter pylori Cag type IV secretion apparatus. FEBS J 278:1203–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frick-Cheng AE, Pyburn TM, Voss BJ, McDonald WH, Ohi MD, Cover TL. 2016. Molecular and structural analysis of the Helicobacter pylori cag type IV secretion system core complex. mBio 7:e02001-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02001-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatakeyama M. 2014. Helicobacter pylori CagA and gastric cancer: a paradigm for hit-and-run carcinogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 15:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatakeyama M. 2004. Oncogenic mechanisms of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Nat Rev Cancer 4:688–694. doi: 10.1038/nrc1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Backert S, Tegtmeyer N, Selbach M. 2010. The versatility of Helicobacter pylori CagA effector protein functions: the master key hypothesis. Helicobacter 15:163–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tegtmeyer N, Neddermann M, Asche CI, Backert S. 2017. Subversion of host kinases: a key network in cellular signaling hijacked by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Mol Microbiol 105:358–372. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nesic D, Buti L, Lu X, Stebbins CE. 2014. Structure of the Helicobacter pylori CagA oncoprotein bound to the human tumor suppressor ASPP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:1562–1567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320631111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan S, Tompkins LS, Amieva MR. 2009. Helicobacter pylori usurps cell polarity to turn the cell surface into a replicative niche. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000407. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohnishi N, Yuasa H, Tanaka S, Sawa H, Miura M, Matsui A, Higashi H, Musashi M, Iwabuchi K, Suzuki M, Yamada G, Azuma T, Hatakeyama M. 2008. Transgenic expression of Helicobacter pylori CagA induces gastrointestinal and hematopoietic neoplasms in mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:1003–1008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711183105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, Cover TL, Peek RM, Chyou PH, Stemmermann GN, Nomura A. 1995. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res 55:2111–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Orentreich N, Vogelman H. 1997. Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 40:297–301. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. 2003. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 125:1636–1644. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plummer M, van Doorn LJ, Franceschi S, Kleter B, Canzian F, Vivas J, Lopez G, Colin D, Munoz N, Kato I. 2007. Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated genotype and gastric precancerous lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:1328–1334. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blaser MJ. 2005. The biology of cag in the Helicobacter pylori-human interaction. Gastroenterology 128:1512–1515. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crabtree JE, Taylor JD, Wyatt JI, Heatley RV, Shallcross TM, Tompkins DS, Rathbone BJ. 1991. Mucosal IgA recognition of Helicobacter pylori 120 kDa protein, peptic ulceration, and gastric pathology. Lancet 338:332–335. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90477-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nomura AM, Perez-Perez GI, Lee J, Stemmermann G, Blaser MJ. 2002. Relation between Helicobacter pylori cagA status and risk of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Epidemiol 155:1054–1059. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loh JT, Shaffer CL, Piazuelo MB, Bravo LE, McClain MS, Correa P, Cover TL. 2011. Analysis of cagA in Helicobacter pylori strains from Colombian populations with contrasting gastric cancer risk reveals a biomarker for disease severity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20:2237–2249. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferreira RM, Pinto-Ribeiro I, Wen X, Marcos-Pinto R, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Carneiro F, Figueiredo C. 2016. Helicobacter pylori cagA promoter region sequences influence CagA expression and interleukin 8 secretion. J Infect Dis 213:669–673. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith C, Heyne S, Richter AS, Will S, Backofen R. 2010. Freiburg RNA tools: a web server integrating INTARNA, EXPARNA and LOCARNA. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W373–W377. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruber AR, Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Neubock R, Hofacker IL. 2008. The Vienna RNA websuite. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loh JT, Friedman DB, Piazuelo MB, Bravo LE, Wilson KT, Peek RM Jr, Correa P, Cover TL. 2012. Analysis of Helicobacter pylori cagA promoter elements required for salt-induced upregulation of CagA expression. Infect Immun 80:3094–3106. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00232-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loh JT, Torres VJ, Cover TL. 2007. Regulation of Helicobacter pylori cagA expression in response to salt. Cancer Res 67:4709–4715. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voss BJ, Loh JT, Hill S, Rose KL, McDonald WH, Cover TL. 2015. Alteration of the Helicobacter pylori membrane proteome in response to changes in environmental salt concentration. Proteomics Clin Appl 9:1021–1034. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Sablet T, Piazuelo MB, Shaffer CL, Schneider BG, Asim M, Chaturvedi R, Bravo LE, Sicinschi LA, Delgado AG, Mera RM, Israel DA, Romero-Gallo J, Peek RM Jr, Cover TL, Correa P, Wilson KT. 2011. Phylogeographic origin of Helicobacter pylori is a determinant of gastric cancer risk. Gut 60:1189–1195. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.234468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baidya AK, Bhattacharya S, Chowdhury R. 2015. Role of the flagellar hook-length control protein FliK and sigma28 in cagA expression in gastric cell-adhered Helicobacter pylori. J Infect Dis 211:1779–1789. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santangelo TJ, Artsimovitch I. 2011. Termination and antitermination: RNA polymerase runs a stop sign. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:319–329. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stulke J. 2002. Control of transcription termination in bacteria by RNA-binding proteins that modulate RNA structures. Arch Microbiol 177:433–440. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Assche E, Van Puyvelde S, Vanderleyden J, Steenackers HP. 2015. RNA-binding proteins involved in post-transcriptional regulation in bacteria. Front Microbiol 6:141. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Declerck N, Dutartre H, Receveur V, Dubois V, Royer C, Aymerich S, van Tilbeurgh H. 2001. Dimer stabilization upon activation of the transcriptional antiterminator LicT. J Mol Biol 314:671–681. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demene H, Ducat T, De Guillen K, Birck C, Aymerich S, Kochoyan M, Declerck N. 2008. Structural mechanism of signal transduction between the RNA-binding domain and the phosphotransferase system regulation domain of the LicT antiterminator. J Biol Chem 283:30838–30849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805955200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumarevel T, Mizuno H, Kumar PK. 2005. Structural basis of HutP-mediated anti-termination and roles of the Mg2+ ion and l-histidine ligand. Nature 434:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nature03355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmalisch MH, Bachem S, Stulke J. 2003. Control of the Bacillus subtilis antiterminator protein GlcT by phosphorylation. Elucidation of the phosphorylation chain leading to inactivation of GlcT. J Biol Chem 278:51108–51115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amilon KR, Letley DP, Winter JA, Robinson K, Atherton JC. 2015. Expression of the Helicobacter pylori virulence factor vacuolating cytotoxin A (vacA) is influenced by a potential stem-loop structure in the 5' untranslated region of the transcript. Mol Microbiol 98:831–846. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawrylik SJ, Wasilko DJ, Haskell SL, Gootz TD, Lee SE. 1994. Bisulfite or sulfite inhibits growth of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol 32:790–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrozo RM, Cooke CL, Hansen LM, Lam AM, Gaddy JA, Johnson EM, Cariaga TA, Suarez G, Peek RM Jr, Cover TL, Solnick JV. 2013. Functional plasticity in the type IV secretion system of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003189. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Styer CM, Hansen LM, Cooke CL, Gundersen AM, Choi SS, Berg DE, Benghezal M, Marshall BJ, Peek RM Jr, Boren T, Solnick JV. 2010. Expression of the BabA adhesin during experimental infection with Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun 78:1593–1600. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01297-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dailidiene D, Dailide G, Kersulyte D, Berg DE. 2006. Contraselectable streptomycin susceptibility determinant for genetic manipulation and analysis of Helicobacter pylori. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5908–5914. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01135-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loh JT, Gaddy JA, Algood HM, Gaudieri S, Mallal S, Cover TL. 2015. Helicobacter pylori adaptation in vivo in response to a high-salt diet. Infect Immun 83:4871–4883. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00918-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Douillard FP, Ryan KA, Caly DL, Hinds J, Witney AA, Husain SE, O'Toole PW. 2008. Posttranscriptional regulation of flagellin synthesis in Helicobacter pylori by the RpoN chaperone HP0958. J Bacteriol 190:7975–7984. doi: 10.1128/JB.00879-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spohn G, Delany I, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. 2002. Characterization of the HspR-mediated stress response in Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol 184:2925–2930. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2925-2930.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bevis BJ, Glick BS. 2002. Rapidly maturing variants of the Discosoma red fluorescent protein (DsRed). Nat Biotechnol 20:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness EF, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak HG, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald LM, Lee N, Adams MD, Hickey EK, Berg DE, Gocayne JD, Utterback TR, Peterson JD, Kelley JM, Cotton MD, Weidman JM, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes WS, Borodovsky M, Karp PD, Smith HO, Fraser CM, Venter JC. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.