Obesity and related metabolic disorders are prevalent and on the rise in western countries, with limited therapeutic options. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), is a widely used drug to treat liver diseases including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cholestasis, and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). Although UDCA treatment reduces hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in mice [1], clinical evidence supporting the mechanism of UDCA efficacy on metabolic profiles in humans is lacking. In the paper titled “Ursodeoxycholic acid exerts farnesoid X receptor-antagonistic effects on bile acid and lipid metabolism in morbid obesity” Mueller et al. [2], examined the effects of UDCA in a small cohort of morbidly obese patients. By analysis of serum fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), hepatic CYP7A1 expression and its product 7α-hydroxycholesterol in bile, they suggest that UDCA decreases signaling of the nuclear receptor and ligand-activated transcription factor farnesoid X receptor (FXR). Acute three-week treatment with UDCA administered at 20 mg/kg/day, lowered hepatic cholesterol and serum LDL-cholesterol, and induced steroyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) resulting in an increase in less toxic unsaturated fatty acids in the liver. This is the first study in humans reporting that inhibition of FXR signaling has beneficial effects for obesity.

Bile acids are synthesized in the liver from cholesterol by cytochromes P450 (CYP) with CYP7A1 being the major, rate-limiting enzyme. The oxidized bile acid metabolites are then conjugated with glycine (mainly in humans) or taurine (mainly in rats and mice) and then transported into the intestine. Bile acids produced in the liver can be further metabolized by gut bacteria through dehydroxylation and deconjugation reactions, and most bile acids are then re-absorbed through the intestinal epithelia to the blood stream, in the process of enterohepatic circulation [3,4]. Bile acid synthesis and transport in the liver, and transport in the intestine, is regulated by FXR. Some bile acid metabolites produced in the liver are agonists for FXR, and when they accumulate, can activate FXR resulting in down-regulation of CYP7A1 and bile acid synthesis, decreased bile acid uptake from the blood, and increased bile acid export to the canaliculus and intestine, resulting in lower cellular bile acid levels. In intestinal epithelial cells, activation of FXR increases bile acid transport into the cell and to the blood followed by uptake by the liver, thus completing the cycle of enterohepatic circulation. In addition, FXR induces expression of the peptide hormone FGF19 in the intestine that then activates the FGFR4/Klotho-β receptor on the hepatocyte plasma membrane, which through a signaling network, down-regulates CYP7A1 expression. Thus, in the presence of high bile acid levels in the hepatocyte and intestinal epithelial cells, FXR is activated, CYP7A1 is reduced, and bile acid synthesis is suppressed. Some bile acid metabolites, notably the conjugated derivatives, are FXR antagonists [5,6], and thus, there likely exists a competition between FXR agonist and antagonist for the modulation of this transcription factor and this balance could influence metabolism and metabolic disorders in mice and humans.

Due to the practical limitations in this human study of obesity by Mueller et al., the precise mechanism of the effects of UDCA could not be precisely determined, but the authors propose that the efficacy of this agent is due to suppression of FXR signaling. Indeed, correlative evidence suggests that UDCA inhibits FXR signaling and that this likely occurs in the intestine since levels of FGF19 encoded by a FXR target gene in the intestine are decreased about 20% and is correlated with an increase in CYP7A1 expression. Hepatic FXR signaling did not appear to be influenced by UDCA. Some of the beneficial effects observed in obesity are likely due to the increase in CYP7A1 as the authors’ suggest. Indeed, overexpression of human CYP7A1 in mice was shown to have beneficial metabolic effects, including decreased high-fat diet-induced obesity and related insulin resistance [7–10]. Three weeks of UDCA treatment in the study by Mueller et al. might not be sufficient to observe significant differences in insulin resistance. However, in another larger and longer (1 year) randomized controlled trial, UDCA treatment improved NASH and insulin resistance [11].

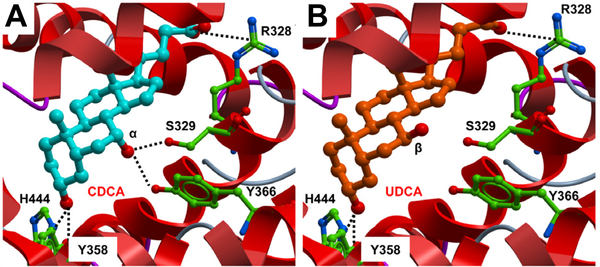

There are no published studies showing that UDCA is a direct antagonist of FXR. To investigate this possibility at the in silico level, molecular docking was used to investigate whether UDCA can bind to the human FXR ligand-binding domain (LBD). The FXR-LBD in complex with agonist 3d-chenodeoxycholic acid (3dCDCA) was retrieved from the public database (1OT7, R1). Initially, CDCA (7α-OH) was docked into the binding pocket with a score of −42.8 reproducing the same non-covalent interactions observed with 3dCDCA (R1) plus the hydrogen bonds between the 3α-OH of the ligand and the side chain of residues His444 and Tyr358 (Fig. 1A). UDCA (7β-OH) docked with a score of −38.96. Interestingly, the β-OH isomerism at position C-7 of the ligand does not favor formation of the hydrogen bond with both side chains of Ser329 and Tyr366 previously detected with an FXR agonist (Fig. 1A, B). The docking poses of CDCA and UDCA are similar and primarily differ by the presence or not of the interaction between the 7-OH of UDCA and Ser329 and/or Tyr366 of the protein. This could explain the weak antagonism or partial agonism activity observed with this ligand. In any case, whether UDCA is an FXR direct antagonist needs to be addressed experimentally.

Fig. 1. Docking of CDCA (A) and UCDA (B) into the human FXR-LBD in the agonist conformation (Molsoft ICM).

The ligands are displayed as sticks and colored by atom type, with carbon atoms in cyan (CDCA) and orange (UCDA); protein residues are displayed as stick with the carbon atoms colored in green. Secondary structure is displayed as ribbon. Protein–ligand hydrogen bond and salt bridge interactions are displayed as dashed black lines, respectively (Molsoft ICM).

After oral administration, UDCA is increased almost 50-fold and thus it is surprising that it had no apparent effects on FXR signaling in the liver, as monitored by the lack of a change in the FXR target gene small heterodimer protein (SHP) mRNA expression. This would also suggest that UDCA is not a direct FXR antagonist. About 60% of the UDCA dose is absorbed in the intestine, and over 60% of the absorbed dose enters the liver and is readily conjugated with glycine to form gly-UDCA, and to a lesser extent with taurine to form TUDCA [12]. The 20-fold increase in serum TUDCA, could also contribute to the improved metabolic effects, since TUDCA, is an inhibitor of ER stress [13] that increases human insulin sensitivity [14].

Another possible contributor to the metabolic effects of UDCA is changes in the composition of the gut microbiota. It is well established that gut microbiota influences metabolic diseases [15,16]. Perhaps an effect of UDCA on endogenous bile acid metabolism as a result of elevated bile synthesis by CYP7A1 alters the gut microbiota population and that this in turn influences metabolism. In view of numerous correlative studies in humans and mechanistic studies in mouse models, this possibility cannot be excluded [5,6,17,18]. The altered bile acid composition from the suppression of intestinal FXR by UDCA could generate agonist for TGR5 and this signaling pathway may produce some of the beneficial metabolic effects observed with UDCA. The TGR5 receptor (or GP-BAR1, M-BAR) is a G-coupled protein receptor specific for bile acids that when activated, improves metabolic disorders [19]. These possibilities require a more comprehensive analysis of bile acid metabolites in subjects treated with UDCA. It cannot be totally excluded that UDCA, or some UDCA metabolites produced in vivo, modulates TGR5. Indeed, UDCA has TGR5 signaling activity in reporter gene assays and was as a scaffold to develop TGR5 activators [20–22].

FXR has emerged as a target for drugs to treat metabolic disorders. The potent FXR agonist, obeticholic acid is in clinical trials and has shown efficacy for fatty liver disease and possibly for insulin resistance [23]. Obeticholic acid targets the liver and suppresses bile acid synthesis and alters bile acid transport as noted above resulting in lowering of cholestasis and hepatic lipids. A recent study found that a gut-selective FXR agonist fexaramine has beneficial effects in high-fat diet-treated mice including decreasing obesity and insulin resistance [24]. Other studies in mouse models of obesity indicate that antagonism of intestinal FXR signaling would be of potential clinical benefic in the treatment of obesity, insulin resistance and fatty liver disease [6,18]. These studies are in agreement with the human studies with UDCA [2,11], yet additional clinical trials must be conducted to determine if inhibition of intestinal FXR is a pathway for treatment of human metabolic disorders.

Acknowledgments

The underlying research reported in the study was funded by the National Cancer Institute Intramural Research Program.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

References

- [1].Tsuchida T, Shiraishi M, Ohta T, Sakai K, Ishii S. Ursodeoxycholic acid improves insulin sensitivity and hepatic steatosis by inducing the excretion of hepatic lipids in high-fat diet-fed KK-Ay mice. Metab Clin Exp 2012;61:944–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mueller M, Thorell A, Claudel T, Jha P, Koefeler H, Lackner C, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid exerts farnesoid X receptor-antagonistic effects on bile acid and lipid metabolism in morbid obesity. J Hepatol 2015;62:1398–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gonzalez FJ. Nuclear receptor control of enterohepatic circulation. Compr Physiol 2012;2:2811–2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Matsubara T, Li F, Gonzalez FJ. FXR signaling in the enterohepatic system. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013;368:17–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sayin SI, Wahlstrom A, Felin J, Jantti S, Marschall HU, Bamberg K, et al. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell Metab 2013;17:225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li F, Jiang C, Krausz KW, Li Y, Albert I, Hao H, et al. Microbiome remodelling leads to inhibition of intestinal farnesoid X receptor signalling and decreased obesity. Nat Commun 2013;4:2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Miyake JH, Duong-Polk XT, Taylor JM, Du EZ, Castellani LW, Lusis AJ, et al. Transgenic expression of cholesterol-7-alpha-hydroxylase prevents atherosclerosis in C57BL/6J mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li T, Owsley E, Matozel M, Hsu P, Novak CM, Chiang JY. Transgenic expression of cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase in the liver prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Hepatology 2010;52:678–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Li T, Matozel M, Boehme S, Kong B, Nilsson LM, Guo G, et al. Overexpression of cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase promotes hepatic bile acid synthesis and secretion and maintains cholesterol homeostasis. Hepatology 2011;53: 996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Qi Y, Jiang C, Cheng J, Krausz KW, Li T, Ferrell JM, et al. Bile acid signaling in lipid metabolism: metabolomic and lipidomic analysis of lipid and bile acid markers linked to anti-obesity and anti-diabetes in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015;1851:19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ratziu V, de Ledinghen V, Oberti F, Mathurin P, Wartelle-Bladou C, Renou C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of high-dose ursodesoxycholic acid for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 2011;54:1011–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Trauner M, Graziadei IW. Review article: mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of ursodeoxycholic acid in chronic liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:979–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gani AR, Uppala JK, Ramaiah KV. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid prevents stress induced aggregation of proteins in vitro and promotes PERK activation in HepG2 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 2015;568C:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kars M, Yang L, Gregor MF, Mohammed BS, Pietka TA, Finck BN, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid may improve liver and muscle but not adipose tissue insulin sensitivity in obese men and women. Diabetes 2010;59:1899–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Turnbaugh PJ, Gordon JI. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J Physiol 2009;587:4153–4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Joyce SA, Gahan CG. The gut microbiota and the metabolic health of the host. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2014;30:120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ryan KK, Tremaroli V, Clemmensen C, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Myronovych A, Karns R, et al. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature 2014;509:183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jiang C, Xie C, Li F, Zhang L, Nichols RG, Krausz KW, et al. Intestinal farnesoid X receptor signaling promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest 2015;125:386–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Duboc H, Tache Y, Hofmann AF. The bile acid TGR5 membrane receptor: from basic research to clinical application. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46:302–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Iguchi Y, Nishimaki-Mogami T, Yamaguchi M, Teraoka F, Kaneko T, Une M. Effects of chemical modification of ursodeoxycholic acid on TGR5 activation. Biol Pharm Bull 2011;34:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sepe V, Renga B, Festa C, D’Amore C, Masullo D, Cipriani S, et al. Modification on ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) scaffold. Discovery of bile acid derivatives as selective agonists of cell-surface G-protein coupled bile acid receptor 1 (GP-BAR1). J Med Chem 2014;57:7687–7701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Festa C, Renga B, D’Amore C, Sepe V, Finamore C, De Marino S, et al. Exploitation of cholane scaffold for the discovery of potent and selective farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and G-protein coupled bile acid receptor 1 (GPBAR1) ligands. J Med Chem 2014;57:8477–8495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, Abdelmalek MF, et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fang S, Suh JM, Reilly SM, Yu E, Osborn O, Lackey D, et al. Intestinal FXR agonism promotes adipose tissue browning and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Med 2015;21:159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]